ABSTRACT

Students as partners (SaP) is gaining attention in higher education (HE) as universities worldwide rethink pedagogical practices through a relationship-rich lens. Many studies have examined partnership practices, conceptions of learner-teacher partnerships and its application in various (mainly anglophone) contexts. However, relatively few studies have explored SaP issues in non-anglophone contexts (e.g., China). In this study, we interviewed 20 lecturers at a Chinese university to understand how they perceived the role of students in teaching and learning. Our reflexive thematic analysis found that many lecturers were open to, and some already practising forms of, partnership practices. But pragmatic, structural and cultural issues caused hesitation, particularly the cultural heritage of Confucian education and global HE competition drivers rewarding research outputs over teaching practices. This study is an initial step in exploring academics’ perceptions of SaP in a changing Chinese HE system with a strong policy focus on student-centred approaches.

Introduction

Students as partners (SaP) is gaining attention in higher education (HE) research and development as universities worldwide are rethinking pedagogical practices through a relationship-rich ethos of partnership. A growing number of scholars from different countries are practising and researching SaP in HE. A review of over 60 publications in five years of SaP studies found that both students and staff positively benefited from SaP practices in both affective and cognitive ways (Matthews, Mercer-Mapstone, et al., Citation2019). While research is largely conducted in anglophone, western-centric contexts (Mercer-Mapstone et al., Citation2017), there is an emergence of research into SaP practices in Asian universities (Carless & Yuen-Ying Kwan, Citation2019; Liang & Matthews, Citation2021a). How the Chinese sociocultural, educational and political heritage reshapes the dynamics of learner-teacher relationships is a consequential question in a rapidly changing Chinese higher education system. A dominant interpretation of Confucianism as a hierarchical relationship between teacher and learner necessary for the transmission of knowledge from knower to novice (Barratt-Pugh et al., Citation2019) is typically viewed as an obstacle to learner-teacher relationship framed as a partnership (Kaur et al., Citation2019). However, recent research has raised questions about the shifting and diverse identities of Chinese students (Liang et al., Citation2020) and the interest of students across Chinese universities to engage in partnership practices with their instructors (Dai et al., Citation2021; Liang & Matthews, Citation2021b).

Understanding how teaching staff (instructors, lecturers, academics or faculty members, depending on context) perceive and construct pedagogical relationships with students is a key factor in engaging students as partners in higher education. As scholars have noted, learner-teacher relationships are initially fostered by teachers, who set the tone for ongoing interactions with and between students (Cook-Sather et al., Citation2014; Godbold et al., Citation2021). Thus, for new or different formations of learner-teacher relationships and SaP to surface in Chinese HE, teachers play a crucial role. However, many academics are weary of investing in teaching because of the research-oriented assessment system, which is highly influenced by the global and domestic competition (e.g., publication and ranking) in higher education (Flowerdew & Li, Citation2009; Xu, Citation2019). As a result, many academics are highly focused on research activities to the detriment of teaching. Thus, while the research sector has gained substantive development in the past decades, enhancing teaching quality and student engagement has become a consistent issue (Wei, Citation2018). Chinese government and universities have advocated that academics should pay ‘equal’ attention to research and teaching. Practically, how Chinese academics perceive pedagogical relationships with students are still under-researched even though some studies have theoretically discussed the power shifts and identity changes in teaching and learning processes in China (Liang et al., Citation2020). More specifically, this study attempts to make sense of Chinese academics’ understanding of the concept of SaP, which is still not deeply understood by non-western contexts. To explore this issue, we conducted exploratory interviews with 20 lecturers to understand how they establish interactions with students and (if not in the current realm of practice) how they respond to the idea of pedagogical partnership with students. We begin with a brief overview of research into SaP, focusing on where that research is conducted.

Research and context: engaging students as partners in higher education

In the broadest sense, SaP involves students as ‘active participants in their own learning in the classroom and engaged in all aspects of university efforts to enhance education’ (Healey et al., Citation2014, p. 36). It draws attention to the quality of the relationship between learners and teachers in HE while signalling that the relationship should aspire to be a partnership. In practice, SaP is ‘a collaborative, reciprocal process through which all participants could contribute equally, although not necessarily in the same ways, to curricular or pedagogical conceptualisation, decision-making, implementation, investigation or analysis’ (Cook-Sather et al., Citation2014, pp. 6–7). In theory, partnership practice ‘challenges traditional assumptions about the identities of and relationships between, learners and teachers’ by calling into question taken-for-granted roles that define what it means to be the student and the teacher as students take on greater responsibility and autonomy (Matthews, Citation2017, p. 1).

Research into SaP is primarily published by scholars from Australia, Canada, the USA, the UK and Western European countries (Mercer-Mapstone et al., Citation2017). Cook-Sather (Citation2014) explored the USA academics’ perceptions towards pedagogical partnership practices with undergraduate students and found that many academics were willing to ‘embrace student as partners and change agents in explorations of pedagogical practice’ (p. 195). In Canada, Marquis et al. (Citation2016) investigated the experiences of both students and staff in a SaP-based program, involving semester-long, extra-curricular projects exploring learning and teaching as a scholarly practice. In line with Cook-Sather’s (Citation2014) findings, their study indicated that engaging students as partners in pedagogical practices could reshape traditional learner-teacher relationships and roles – potentially fostering agency and motivation as identities of and power dynamics between students and teachers shifted.

More recently, in Australia, Matthews et al. (Citation2018) examined the experiences of those involved (students, academics and professional staff) in year-long, extra-curricular partnership practices. They found that SaP resonated with participants as a value-based practice that offered a counter-narrative to the growing rhetoric of students as passive customers. In the UK, by exploring the perceptions of key stakeholders (students, academics, professional staff and university leaders) towards the concept and practice of SaP, Gravett et al. (Citation2019) found that when the university embraced the partnership ethos and created new opportunities for students to partner with staff, these participants gained ‘shared understanding’ and ‘ownership’ for learning and teaching.

Research into SaP is emerging in China. For example, Ho (Citation2017) reflected on a student consultant model of partnership in a Hong Kong university where faculty partners tended to be ‘westerners with a variety of Hong Kong experiences and students were local to Hong Kong’ that resulted a ‘powerful discussion about cultural differences’ (p. 2). This resonates with Liang and Matthews' (Citation2021a) scoping review of SaP in Asia that identified a strong influence of anglophone scholarship on Asian practices. Acknowledging cultural stances and power differences, Ho (Citation2017) suggested and Green (Citation2019a, Citation2019b) argued, it is necessary to enrich SaP practices as a form of global learning. Models to guide research and situated practices globally that recognise the role of culture, beyond the assumption of an anglophone, western context are emerging.

Understanding the conceptualisations of learner-teacher relationships in Chinese universities is important in understanding how partnership practices develop and unfold in Confucian cultural heritage contexts and politicised organisational structures, as Dai et al. (Citation2021, p. 12) recently argued:

Our stance is that SaP should manifest in Chinese higher education and in doing so will form and function – and be discussed and named – differently to that of western practices. Transplanting western-centric SaP practices underpinned by western values into Chinese universities is problematic.

In understanding how Chinese students make sense of their pedagogical relationship with lecturers, Liang and Matthews (Citation2021a) found among 402 surveyed students an interest in more partnership-like interactions. Using interviews with 30 Chinese postgraduate students, Dai et al. (Citation2021) found that the language of the followers (as undergraduate students) and family (as postgraduate students) was evoked to describe their pedagogical relationships with teachers. To further collective understanding of learner-teacher relationships in Chinese universities, our study interviews academic staff and is guided by the question: How do academics in Chinese universities make sense of their pedagogical relationships with students and the idea of engaging with students as partners?

Methodology

Teaching and learning and the relationships between learners and teachers are socially constructed from individual perspectives that vary depending on experiences and worldviews (Merriam, Citation2009). Our approach, as qualitative researchers, is to understand how participants and academics in a Chinese university make sense of their experiences of interacting with university students. A qualitative exploratory study, as Creswell (Citation2012) explained, enabled us to examine complex, yet not well understood or theorised issues to illuminate new insights into and different perspectives on, the relatively unknown topic of engaging students as partners in Chinese HE. This study was conducted in accordance with institutional ethical approval.

Participants

The present study was conducted in China. Twenty academics (including 12 males and eight females) voluntarily participated in our study from a comprehensive research-intensive, top-tier Chinese university in Beijing. In most courses, the dominant teaching mode in this university was lecture based. Seminar/lab-based teaching also existed in educational practices depending on academics’ preferences and course requirements. Participants taught at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels, in Business (five), Engineering (five), Education (six) and Media Communications (four). All participants hold doctoral degrees, including eight assistant professors, seven associate professors and five professors.

Interviews

To understand participants’ lived experiences and subjective realities as academics in China, we conducted (and audio-recorded) semi-structured interviews in the Chinese language. The participants shared information about their teaching experiences in both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. Then, they illustrated their pedagogical relationships with students focused on pedagogical interactions with students in and out of the classroom. Based on previous research showing the unfamiliarity of the English language term SaP in China (Dai et al., Citation2021), we did not use the explicit term SaP to recruit participants or to start the interviews. Instead, the interviews focused on learner-teacher interactions and pedagogical practices that illuminated assumptions about the role of students in learning and teaching. Thereafter, the term and the concept of SaP were introduced to further probe beliefs and assumptions that moved us towards each participant’s concept of engaging with students in pedagogical partnership practices.

Analysis

The interview recordings were transcribed in Chinese and translated into English. Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2019) reflexive thematic analysis approach was conducted to analyse data. The analysis involved an iterative process of inductive and deductive coding, reflection and interpretation to clarify the data and explore potential themes from academics’ understanding of their pedagogical relationships with students. Codes and themes were visually mapped and re-mapped leading to themes being described in a table format with selected salient quotes. Then themes and sub-themes were considered in regard to flow and presentation of results that illustrated academics’ lived experiences and attitudes toward SaP. To give a voice to academics, we presented selected quotes (pseudonyms used) within the description of our findings. The selected quotes reflect general views towards SaP without focusing on specific levels of study.

Findings and discussion

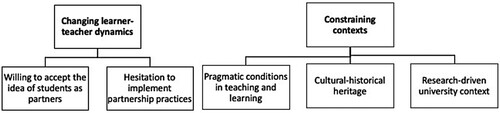

The analysis revealed a nuanced, multi-layered conception of engaging students as partners acknowledging the changing learner-teacher dynamics in Chinese universities. In doing so, they raised tensions about the feasibility of practising partnership in their specific context of teaching and learning in the university and the global HE context of the research pressures of being in a top-ranked Chinese university. Two themes and five sub-themes were identified from the analysis, which are presented in and elaborated below. We bring our findings into scholarly conversation on engaging students as partners in learning and teaching, drawing on Healey et al. (Citation2020), by combining our findings and discussion.

Changing learner-teacher dynamics

The analysis indicated that many academics were open to the idea of student partnership. Some academics described partnership-like practices and efforts they already instigated to better involve students as active contributors and co-teachers in their classes. And concerns about the implementation of SaP were common across the interviews. Yet, there was an acceptance that the dynamics – the educational roles and relationships – between learners and teachers were shifting in China. Chinese HE is a complex enterprise with national policies to increase the global reputation of certain universities (focus on research) and move towards student-centred pedagogies (focus on teaching) that foster autonomy and enhance student learning with diverse and changing student and academic identities (Dai & Tian, Citation2020). It is in this context that academics in our study reflect on pedagogical interactions with students and the concept of SaP. We report two sub-themes arising from our analysis of the interviews.

Willing to accept the idea of students as partners

Many lecturers were willing to accept the idea that students should be partners because doing so could engage students differently – more actively – in the teaching and learning processes. This would involve a shift in beliefs about who possesses knowledge and know-how in the class. For example, Ling, who teaches business, stated:

Positioning students as partners rather than followers in pedagogical practices could be a very effective way that makes them (students) participate in different stages of teaching and learning processes. Some students are very creative and know a lot of things that are valuable for other peers and lecturers to learn. So, as a lecturer, I think we should first believe that many students have abilities to make contributions to teaching, curriculum design, and/or assessment.

Teaching and learning practices now at universities are totally different from 20 or 30 years ago. Benefitting from the development of the economy and technology, many students have learned modern and advanced knowledge during their school stage, which potentially fostered students’ abilities to explore in-depth content. When they move to university, many of them (students) can actively engage in different teaching and research activities. Thus, I think lecturers now should rethink their and (their) students’ roles. Academics need to strategically design and teach courses by critically thinking about the position of students.

Many students might know more cutting-edged knowledge than me. So, I think it is essential to allow students to actively participate in teaching processes, which is another way of learning. In some classes, I invite students to teach me and other peers. In this case, the student gets the opportunity to show him/herself as a ‘lecturer’. Many students like this experience. Thus, I think lecturers should not hold the traditional view about students, who do not know much. Based on my teaching experience, I feel that many of my students are excellent, and they can contribute to teaching, rather than only just listening to me.

Hesitation to implement

The practicalities and pragmatics of SaP were consistently raised by the participants in our study, in many ways aligning with the existing literature on SaP. For example, the study by Bovill et al. (Citation2016) and a literature review on SaP benefits and obstacles (Matthews, Mercer-Mapstone, et al., Citation2019) raised the issues of class size, students’ and teachers’ resistance to the changing power dynamics, ways to communicate SaP to people unfamiliar with the concept, approaches to implement the concept for a large number of students and academics and concerns about inclusion and equity. Yu, who teaches business, suggested that:

It is necessary for lecturers to know what SaP is first, and then encourage them to implement based on their situations and also subject features. Some courses may not be good for involving students as partners. Some courses may be valuable for them to engage in. Therefore, I think the implementation of SaP is a complex process. How to adopt this theoretical initiative into practices could be challenging for both lecturers and students. If every student wants to be a ‘partner’, what should lecturers do? Thus, I think it is very challenging to reshape the existing lecturer-centred mode in a general sense.

Encouraging students to be partners in teaching and learning could motivate their learning enthusiasm. However, it is challenging for lecturers and students to work together in practice. Even though some students may have solid knowledge in a field, they may not know how to teach for other peers. Thus, I think lecturers are still important and should be still dominators in curriculum design and teaching practices.

It is impossible for students to become partners in every step of teaching. So, students could become partners in some cases. But more importantly, lecturers should know when, how, and why to position students as partners. If lecturers cannot carefully and strategically design the teaching strategies, I think it is better to adopt the traditional mode, which is much safer than using novel approaches.

What is evident from the nuanced responses of the academic participants in our study is the consideration of the complexity of changing the role of students, which changes the role of academics. The recognition that students are changing is apparent, while academics are grappling with what new student autonomy may mean in the existing context of Chinese universities. The hesitation raised in their practices (within their control) was matched by an analysis of the contexts of Chinese universities (out of their control) that constrained their time, energy and capacity for risk – alluded to above (safer to stay with what is known). The second theme refers to the constraining contexts.

Constraining contexts

Beyond the relational and pedagogical hesitations that largely resonated with existing scholars from anglophone, western contexts (but challenged a dominant discourse of Chinese academics as authorities who prefer passive students), three aspects of the educational contexts surfaced: pragmatics of the teaching and learning context; cultural and historical context; and the research-driven university context. These constraining contexts worked against SaP in the view of many in this study.

Pragmatic conditions in teaching and learning

The size of the classes was again discussed as an obstacle when SaP was imagined as involving all students in the creation of specific or unique curricula, as Xiang who teaches business, articulated this issue:

Based on my approximately 10 years of teaching experience at three universities, I think most undergraduate classes have many students, for example, usually 40–50, even more than 100. In this case, lecturers cannot create something specific for every student to equally participate in curriculum design. What most lecturers usually did was ask some questions in class. Otherwise, it was impossible to create something new in teaching.

Before proceeding to the next sub-theme, what also emerged was a comparison of the structure of contact in Chinese universities versus Australia as Yang, who teaches education, commented as they drew on their overseas education:

I remembered that when I was studying at an Australian university, I needed to attend lectures and tutorials. Lectures were the same style as in China. But tutorials were different, which only had small numbers of students. In this case, lecturers and students could have more opportunities to interact with each other. In many courses, students could become leaders to teach. So, I felt that such mode could allow students to have more opportunities to engage in teaching practices and present their voice. However, such modes are rare at most Chinese universities, which are mainly based on traditional lectures.

The tensions between academics in the study already moving towards or further practising forms of partnership (e.g., Gang and Gu) with those (e.g., Yang, Xiang) raising legitimate concerns about the pragmatics of teaching and learning represent a shift between realist and idealist stances. What is possible through partnership and what is pragmatic, is a common tension in the existing SaP literature, yet the next sub-theme moves us into specifics of the teaching and learning context in a Chinese elite university, which may be highly influenced by the Confucian cultural heritage and politicised organisational structures. These issues are currently situated in the SaP literature as a crucial barrier and in need of critical consideration by scholars (Liang & Matthews, Citation2021a).

Cultural-historical heritage

Power dynamics are central to SaP and entangled with the identities of students and teachers, which are culturally situated. The relationship between academics and students has been consistently framed, either explicitly or implicitly, within the cultural context of China. For example, Qian, teaching education, discussed an attempt to move students from being followers to being active partners:

I attempted to create some opportunities to let students engage in teaching processes and to let them have their voice in many situations. However, I realised that most students were quiet, and they seemed to be afraid of actively showing themselves, especially, in front of lecturers or other peers. One-to-one communication may be much better for many students.

When students were studying in primary, secondary, and high schools, they were told that ‘listening to teachers or other elders’ defined being good children. Thus, most teaching and learning activities happened in a hierarchical context. Even though some lecturers may wish to let students engage in teaching design, for example, practically, students will still be naturally passive.

However, the role of broader national culture is rarely explicitly unpacked in the predominantly anglophone body of research on SaP. Ga articulates an explicit reflection on the Confucian educational culture that signals the depth of nuance as academics in the study consider power dynamics in learner-teacher relationships when framed as a partnership. Distinct from Qian and Yun’s comments, Ga, who teaches business, argued that:

Chinese culture is very complex. For instance, Confucius advocated that people ‘respect teachers and teaching’. And he also mentioned that ‘among the three people walking ahead of me, there must be one who could be a teacher of mine’. From these traditional sayings, we can see that educational philosophy in China is a hybrid. It asks people to follow the authority but also advocates equity and partnership.

Along with the constraining cultural context viewed as being specific to China, participants described the context of the research-intensive university – with exacting metrics of performance that privileged research over teaching – as another constraining factor impacting how they imagined SaP.

Research-driven university context

Many academics are highly focused on research to fulfil university assessment criteria. As Min mentioned, ‘publications and research grants are much more important than teaching because university wants these visible outcomes in ranking competitions’. While engaging students as partners in teaching and learning processes was recognised in the interviews as valuable for the longitudinal and sustainable development of the university, the tension between teaching and research was consistently articulated, as Hong, who teaches business, explained:

Although ministry of education and universities have published various policies to emphasise the importance of teaching at university, when academics apply for promotions, most evaluations are based on publications and grants. Thus, it is potentially challenging for lecturers to do teaching and research all to a good quality.

Compared to some new pedagogical initiatives (e.g., SaP), didactical approaches seem to be easier to practice. Some lecturers may not want to have too much working stress, so they let students ‘teach’ in class. In this case, lecturers do not need to spend more time preparing complex teaching strategies. Thus, they could pay more attention to publications and research grant applications, which seems to be much more important than teaching at most Chinese universities.

Universities are chasing the international rankings, so research and publications are very important and became key to increasing such rankings. Thus, universities usually give more awards to academics who can publish in top journals. Therefore, this research-driven focus context potentially causes many lecturers to ignore teaching. In short, many lecturers do not have time to carefully think about how they teach. They may work with students in research, but most of them (lecturers) are the ‘boss’ rather than the ‘partner’. This is the reality.

While there is an important scholarly debate unfolding on the impact of neoliberal trends on growing SaP practices in English-speaking countries, the debate and responses will seemingly differ in Chinese university contexts for both cultural and political reasons. Structural forces shaped by global and domestic academic competition in research have deep influences on pedagogical and research practices (Xu, Citation2019). The global trends and university policies (e.g., chasing publications and grants) have influenced academics’ teaching and research practices in a complex manner. In a practical sense, however, the findings of our study imply that efforts to reform teaching quality in Chinese universities towards student-centred approaches will come into conflict with academic practices on the ground that reward research activities.

Conclusion

Pedagogical partnerships are beginning to emerge in China as national policies shift towards student-centred approaches to enhance student engagement and teaching quality. We investigated Chinese academics’ conceptions of learner-teacher relationships as a pedagogical partnership. Our analysis found that learner-teacher dynamics are changing in China and there is an openness to position students as partners (in contrast to a view of students as followers). However, academics in the study consistently identified issues – some in their control (pedagogical practices and preferences) and some out of their control (pragmatics of teaching and learning, cultural heritage and history-shaping educational relationships and research-focused reward systems).

The research has several limitations. It only investigates a small group of Chinese academics’ views about SaP in one research-focused university. Bringing the views of academics and students into a conversation about SaP in China would advance collective understanding. Future research may investigate a larger number of Chinese academics and/or students working in different types of universities. Meanwhile, it is essential to further investigate the influence of politicised organisational structures on teaching and learning engagement and innovation. Moreover, cross-country comparison research could be conducted to critically understand academics’ views towards SaP.

Our exploratory study makes several important contributions to the ongoing scholarly conversations about SaP as a global practice. First, many of the issues identified by academics resonated with those already named in the existing SaP literature, signalling some scholarly common ground to advance theories of student partnerships in a more globally inclusive conversation. Second, the findings contribute to collective insights into Chinese-specific issues of learner-teacher interactions shaped by the contested influence of Confucianism and structure forces. The final contribution of this study is the extension of the notion of the context-dependent nature of SaP (Healey & Healey, Citation2018) to explicitly situated SaP research in a broader cultural sense. The cultural lens of Confucianism emerged in this study, as expected, yet in a contested manner that warrants further consideration and criticality in the national context of China. Notably, Confucianism and structural forces in Chinese HE system imbricate with each other in complex and interweaving manners, which potentially shapes academics’ hybridised views towards SaP in teaching and research practices.

There are several implications for research about SaP. As theorisations of Confucianism and the organisational culture (e.g., academic assessment policies) shape how students and lecturers relate to each other, research in surface assumptions and conflicting views would enrich practices. Research into existing SaP practices (most likely not named SaP) in China at different types of universities and from the standpoint of the different people involved (e.g., students) can further illuminate learner-teacher pedagogical relationships in China (and in Asian countries). In doing so, researchers should bring a critical cultural lens to name cultural assumptions that open new ways of understanding and practising SaP as a relational pedagogical praxis that unfolds through an array of practices and approaches both inside and outside the classroom.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Barratt-Pugh, L., Zhao, F., Zhang, Z., & Wang, S. (2019). Exploring current Chinese higher education pedagogic tensions through an activity theory lens. Higher Education, 77(5), 831–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0304-8

- Bovill, C. (2017). A framework to explore roles within student-staff partnerships in higher education: Which students are partners, when, and in what ways? International Journal for Students as Partners, 1(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v1i1.3062

- Bovill, C. (2020). Co-creation in learning and teaching: The case for a whole-class approach in higher education. Higher Education, 79(6), 1023–1037. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00453-w

- Bovill, C., Cook-Sather, A., Felten, P., Millard, L., & Moore-Cherry, N. (2016). Addressing potential challenges in co-creating learning and teaching: Overcoming resistance, navigating institutional norms and ensuring inclusivity in student–staff partnerships. Higher Education, 71(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9896-4

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Carless, D., & Yuen-Ying Kwan, C. (2019). Inclusivity, hierarchies, and culture: Two neophytes reflect on the fourth International Students as Partners Institute. International Journal for Students as Partners, 3(2), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v3i2.4126

- Cook-Sather, A. (2014). Student-faculty partnership in explorations of pedagogical practice: A threshold concept in academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 19(3), 186–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2013.805694

- Cook-Sather, A., Bovill, C., & Felten, P. (2014). Engaging students as partners in learning and teaching: A guide for faculty. Josey-Bass.

- Cook-Sather, A., & Felten, P. (2017). Ethics of academic leadership: Guiding learning and teaching. In F. Su, & M. Wood (Eds.), Cosmopolitan perspectives on academic leadership in higher education (pp. 175–191). Bloomsbury.

- Creswell, J. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Pearson.

- Dai, K., Matthews, K. E., & Shen, W. (2021). It is difficult for students to contribute’: Investigating possibilities for pedagogical partnerships in Chinese universities. Teaching in Higher Education, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.2015752

- Dai, K., & Tian, M. (2020). Emerging and (re) shaping ‘identities’ in Chinese higher education. International Journal of Chinese Education, 9(2), 127–130. https://doi.org/10.1163/22125868-12340123

- Flowerdew, J., & Li, Y. (2009). English or Chinese? The trade-off between local and international publication among Chinese academics in the humanities and social sciences. Journal of Second Language Writing, 18(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2008.09.005

- Godbold, N., Hung, T. Y., & Matthews, K. E. (2021). Exploring the role of conflict in co-creation of curriculum through engaging students as partners in the classroom. Higher Education Research & Development, 41, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1887095

- Gravett, K., Kinchin, I. M., & Winstone, N. E. (2019). More than customers’: Conceptions of students as partners held by students, staff, and institutional leaders. Studies in Higher Education, 45, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1623769

- Green, W. (2019a). Stretching the cultural-linguistic boundaries of ‘students as partners’. International Journal for Students as Partners, 3(1), 84–88. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v3i1.3791

- Green, W. (2019b). Engaging ‘students as partners’ in global learning: Some possibilities and provocations. Journal of Studies in International Education, 23(1), 10–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315318814266

- Han, J., & Han, Y. (2019). Cultural concepts as powerful theoretical tools: Chinese teachers’ perceptions of their relationship with students in a cross-cultural context. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning, 13(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2019.130108

- Healey, M., Flint, A., & Harrington, K. (2014). Engagement through partnership: Students as partners in learning and teaching in higher education. Higher Education Academy.

- Healey, M, & Healey, R. (2018). It depends': Exploring the context-dependent nature of students as partners practices and policies. International Journal for Students as Partners, 2(1), 1–10.

- Healey, M., Matthews, K. E., & Cook-Sather, A. (2020). Writing about learning and teaching in higher education. Elon University Press.

- Ho, E. (2017). Small steps toward an ethos of partnership in a Hong Kong university: Lessons from a focus group on ‘homework’. International Journal for Students as Partners, 1(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v1i2.3198

- Kaur, A., Awang-Hashim, R., & Kaur, M. (2019). Students’ experiences of co-creating classroom instruction with faculty – A case study in eastern context. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(4), 461–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1487930

- Lei, L., & Guo, S. (2020). Conceptualizing virtual transnational diaspora: Returning to the ‘return’ of Chinese transnational academics. Asian & Pacific Migration Journal, 29(2), 227–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0117196820935995

- Liang, Y., Dai, K., & Matthews, K. E. (2020). Students as partners: A new ethos for the transformation of teacher and student identities in Chinese higher education. International Journal of Chinese Education, 9(2), 131–150. https://doi.org/10.1163/22125868-12340124

- Liang, Y., & Matthews, K. E. (2021a). Students as partners practices and theorisations in Asia: A scoping review. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(3), 552–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1773771

- Liang, Y., & Matthews, K. E. (2021b). Students as partners in China: Investigating the potentials and possibilities for growing practices across universities. International Journal for Students as Partners, 5(2), 28–47. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v5i2.4767

- Marquis, E., Black, C., & Healey, M. (2017). Responding to the challenges of student-staff partnership: The reflections of participants at an international summer institute. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(6), 720–735. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1289510

- Marquis, E., Puri, V., Wan, S., Ahmad, A., Goff, L., Knorr, K., Vassileva, I., & Woo, J. (2016). Navigating the threshold of student–staff partnerships: A case study from an Ontario teaching and learning institute. International Journal for Academic Development, 21(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1113538

- Matthews, K. E. (2017). Five propositions for genuine students as partners practice. International Journal for Students as Partners, 1(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijasp.v1i2.3315

- Matthews, K. E., Cook-Sather, A., Acai, A., Dvorakova, S. L., Felten, P., Marquis, E., & Mercer-Mapstone, L. (2019). Toward theories of partnership praxis: An analysis of interpretive framing in literature on students as partners in university teaching and learning. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(2), 280–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1530199

- Matthews, K. E., Dwyer, A., Hine, L., & Turner, J. (2018). Conceptions of students as partners. Higher Education, 76(6), 957–971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0257-y

- Matthews, K. E., Mercer-Mapstone, L., Dvorakova, S. L., Acai, A., Cook-Sather, A., Felten, P., Healey, M., Healey, R. L., & Marquis, E. (2019). Enhancing outcomes and reducing inhibitors to the engagement of students and staff in learning and teaching partnerships: Implications for academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 24(3), 246–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2018.1545233

- Mercer-Mapstone, L., Dvorakova, S. L., Matthews, K. E., Abbot, S., Cheng, B., Felten, P., Knorr, K., Marquis, E., Shammas, R., & Swaim, K. (2017). A systematic literature review of students as partners in higher education. International Journal for Students as Partners, 1(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v1i1.3119

- Merriam, S. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. John Wiley & Sons.

- Samuelowicz, K. (1987). Learning problems of overseas students: Two sides of a story. Higher Education Research & Development, 6(2), 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436870060204

- Tweed, R. G., & Lehman, D. R. (2002). Learning considered within a cultural context: Confucian and Socratic approaches. American Psychologist, 57(2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.57.2.89

- Watkins, D., & Biggs, J. B. (1996). The Chinese learner: Cultural, psychological and contextual influences. Australian Council for Educational Research & Comparative Education Research Centre.

- Wei, J. (2018). Practical exploration of undergraduate classroom teaching reform: A case study of Shanxi Normal University. Chinese Education & Society, 51(4), 272–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/10611932.2018.1487194

- Xu, X. (2019). Performing under ‘the baton of administrative power’? Chinese academics’ responses to incentives for international publications. Research Evaluation, 29(1), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvz028