ABSTRACT

Studies about curriculum internationalisation in higher education frequently report poor academic staff engagement hindering implementation in practice. However, such research does not consider the organisational context in which academics operate. This research applies an organisational change perspective to explore how the context affects the process of engagement and implementation and what to change (content). In a comparative case study of four disciplinary contexts in a West-European university from 2012 to 2020, we disclose the perceptions and experiences of twenty-nine academic staff through in-depth interviews. The academics explain how multiple contextual tensions and inadequate resource management complicate their engagement with curriculum internationalisation. Still, they also reveal evidence of many achievements and strong individual drivers with curriculum internationalisation. Our findings show how disciplinary contextual influences and dynamics create specific perceptions and experiences of curriculum internationalisation in each study programme. This article presents a comprehensive framework of organisational change to explain and facilitate academic staff engagement with curriculum internationalisation in disciplinary communities.

Introduction

Academic staff engagement with curriculum internationalisation has been a frequently reported problem throughout the last decades (Whitsed et al., Citation2021). Recent surveys by the European Association for International Education (EAIE) in 2018 and the International Association of Universities (IAU) in 2019 confirm staff engagement as an enduring issue with curriculum internationalisation. Still, as Marantz-Gal and Leask (Citation2020) stress, curriculum internationalisation has become a core activity in universities in which academics must play a crucial role. Riezebos (Citation2017) adds that internationalising teaching and learning is an essential dimension to advance and innovate study programmes. Therefore, it is crucial for researchers and practitioners to investigate academic staff engagement with curriculum internationalisation from multiple perspectives.

Further examination starts with a shared understanding of curriculum internationalisation. Leask (Citation2015, p. 10) defines curriculum internationalisation as ‘engaging students with internationally informed research and cultural and linguistic diversity to develop their international and intercultural perspectives and become global professionals and citizens’. Leask approaches curriculum internationalisation as a broad, contextual process including the content and learning outcomes of the curriculum, teaching methods, assessment tasks, and support services of a study programme. Internationalising programmes requires changes in individual beliefs, disciplinary paradigms and institutional leadership, and demands the engagement of all stakeholders. As van den Hende et al. (Citation2022) demonstrate in a literature review, curriculum internationalisation can be understood as a process with many features of change.

In this change process, several scholars (Green & Whitsed, Citation2015; Leask et al., Citation2020) observe tensions between the expected role of academic staff in curriculum internationalisation and their actual engagement in the process. Many studies (e.g., Agnew, Citation2013; Crosling et al., Citation2008; Leask, Citation2015) denote personal, cultural, disciplinary and institutional blockers causing resistance and disengagement of academic staff with curriculum internationalisation. Their focus is on leadership following strategies, plans and rationales in linear, step-wise processes, directing staff and students to change and achieve particular goals. The terms in italics were identified using discourse analysis on the viewpoint that these authors take on the role of academic staff in the change process. Implicitly, these studies use a theoretical lens on organisational change designated as a rational approach, that is, controlled by strategy, leaders, and plans causing predictable outcomes (Burke & Litwin, Citation1992; Lewin, Citation1951). However, the rational approach to organisational change is one-dimensional and outdated as it does not provide us with insights into the complexity, dynamics and duality of the organisational context, and the emotions and competencies of the stakeholders involved, in this case, the academic staff (Pettigrew et al., Citation2001).

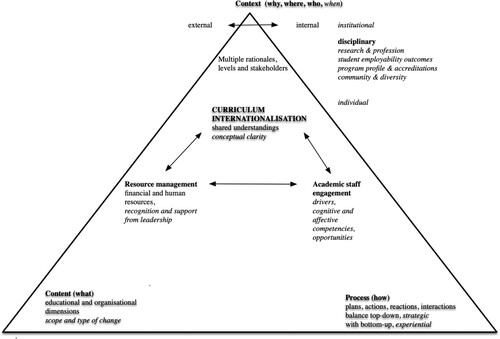

This research applies another organisational change perspective to learn more about the perceptions and experiences of academic staff regarding their engagement with curriculum internationalisation and the impact of their organisational context. We use a framework based on Pettigrew (Citation1987), one of the earliest critics of the rational change approach. The framework connects the process with the context and the content, to clarify how the organisational context and dynamics of change impact the content of what to change and the process of how to do this over a period of time. First, we explain how we operationalise this comprehensive framework of organisational change as developed by van den Hende et al. (Citation2022). See below.

Figure 1. A framework of organisational change for implementing curriculum internationalisation in higher education institutions (van den Hende et al., Citation2022).

An organisational change perspective

According to Pettigrew (Citation1987), an organisational change perspective implies that formulating the content of any strategy inevitably entails managing its context and process. As van den Hende et al. (Citation2022) reveal, the context (why, where, who) with curriculum internationalisation includes the external environment interconnected with the internal culture and structures. The internal context involves multiple rationales, levels, and stakeholders. The content (what) addresses the scope and type of change, with educational and organisational dimensions. Lastly, the process (how) refers to the plans, actions, reactions, and interactions of the multiple stakeholders seeking to implement change and requires a balance between top-down and bottom-up approaches.

In the heart of the framework, we encounter resources. In line with Pettigrew (Citation1987), other scholars have focused on an organisation’s resources as significantly influential in change processes (Eisenhardt & Martin, Citation2000). In the literature about curriculum internationalisation, van den Hende et al. (Citation2022) identify financial and human resources as critical, recurring issues interrelated with staff engagement. Therefore, we have added financial (budget, time, support) and human (knowledge, skills, and leadership) resources to Pettigrew’s framework.

This comprehensive framework of organisational change will allow us to investigate how resources relate to academic staff engagement. As we still do not know how academic staff perceive and experience resources, their role and contextual influences in the change process that curriculum internationalisation entails, we use this framework to research how the academics’ context and resources are relevant for their engagement with curriculum internationalisation over a period of time.

Next, we describe the academics’ institutional, disciplinary and individual contexts to examine how these contexts may influence their engagement with curriculum internationalisation.

Institutional, disciplinary and individual contexts

Public organisations

Many universities can be characterised as public organisations with distinctive institutional structures and cultures (Kuipers et al., Citation2014; Mir et al., Citation2020). Public organisations tend to hold strong public values and are increasingly pluralistic, working with multiple stakeholders from diverse backgrounds in political, juridical, academic, economic, and administrative discourses. With competing beliefs and assumptions, this complex organisational context poses multiple demands on academic staff. Riebe et al. (Citation2021) found that academic staff use more proactive or passive strategies to navigate these tensions (e.g., confronting or avoiding), depending on their competencies and resources. With curriculum internationalisation, van den Hende et al. (Citation2022, p. 7) identify academic autonomy, ownership and hidden powers as critical organisational features affecting staff engagement. Other public organisations face similar issues with staff engagement. For instance, in a study about implementing a new IT system in health care, Boonstra et al. (Citation2014) found that a shared vision, hierarchical and participative leadership, and adequate management of financial and human resources are essential. Therefore, this research incorporates the impact of institutional features and resource management on academic staff engagement with curriculum internationalisation.

Disciplinary communities

In the complex institutional context of higher education, academic staff work in disciplinary communities in which they share a specific way of thinking, working and communicating, and jointly provide and manage educational and research programmes (Becher, Citation1989, Citation1994; Trowler et al., Citation2012). Becher clarifies that disciplinary communities are ‘academic tribes and territories’ with specific cultural characteristics intertwined with cognitive knowledge paradigms, styles of intellectual inquiry and professional groupings. Becher (Citation1994, p. 152) distinguishes four broad disciplinary areas: ‘natural sciences, humanities and social sciences, science-based professions, and social professions’. Trowler et al. (Citation2012) add that interdisciplinary study programmes have increased significantly, yet disciplines remain the primary structures in universities for organising education and research. Pharo et al. (Citation2014) warn against disciplinary fragmentation in this ambiguous context since university teachers are likely to have little awareness of teaching practices and curriculum content beyond their discipline.

In this disciplinary context, curriculum internationalisation is a process in which academic staff have to interact and collaborate with other disciplinary areas and professions (Marantz-Gal & Leask, Citation2020). However, several studies (e.g., Agnew, Citation2013; Clifford in Trowler et al., Citation2012) found that disciplines and programmes have different views and practices regarding curriculum internationalisation. For example, Clifford suggests that, in social sciences, academics would be more engaged with curriculum internationalisation based on their students' and societal needs. In contrast, academics in natural sciences would be more resistant due to their universal principles. Hence, this research involves four study programmes in natural and social sciences, including interdisciplinary programmes as a mixture, to gain a broader understanding of the impact of the disciplinary context and interdisciplinary spaces on academic staff engagement with curriculum internationalisation.

Individual staff

Despite institutional and disciplinary influences, university teaching is also a highly individualised practice. Only recently has more attention been paid to interaction and collaboration within and across disciplines (Pharo et al., Citation2014). Kahn (Citation2010) explains that staff engagement depends not only on someone’s opportunities and commitment to their organisation, work and colleagues but also on an individual’s drivers and competencies. Therefore, this research incorporates the academics’ individual context.

Altogether, this study examines the perceptions and experiences of academic staff in various disciplinary communities regarding their engagement with curriculum internationalisation. We apply an organisational change perspective, aligning the context with the process, content and adequate resource management to develop our framework () and answer our research question.

Research question

How are academic staff perceptions and experiences of their engagement with curriculum internationalisation as an organisational change process influenced by their individual, disciplinary and institutional context and resource management?

Method and data

We are particularly interested in how the academics have perceived and experienced their engagement with curriculum internationalisation and how their disciplinary communities have influenced this change process. Accordingly, we adopted a case study approach (Yin, Citation2014) and conducted interviews with academic staff, which we analysed in a thematic, comparative analysis across time.

Case study

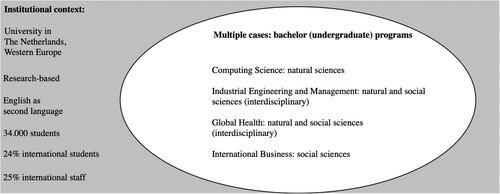

Given our focus on the impact of the disciplinary context on academic staff engagement, we selected four bachelor (undergraduate) programmes within the same university for a comparative case study. This public, research-based university is in the Netherlands, a country in Western Europe with English as a second language. It offers a wide range of programmes taught in English and Dutch, the national language. The university’s strategic aims towards curriculum internationalisation with a considerable number of international students and staff as well as an environment where all students acquire intercultural competency and global awareness as needed for their discipline. Today (2022), the university counts 24% international students, 25% international staff, and 34,000 students (see below).

We chose four bachelor programmes representing the continuum of natural and social science disciplines and mixtures, so-called interdisciplinary programmes (Becher, Citation1989, Citation1994; Trowler et al., Citation2012); Computing Science, Industrial Engineering and Management, Global Health, and International Business. Becher (Citation1989, p. 140) explains Computing Science as a ‘secession from mathematics in natural sciences’ and argues that the ‘theoretical aspects of engineering’ (p. 17) make Industrial Engineering and Management a natural science programme in a business context. Green and Whitsed (Citation2015, p. 26) illustrate that business studies are social science programmes focusing on students’ and societal needs, especially by developing intercultural competency. Lastly, Clifford assumes in Trowler et al. (Citation2012, p. 199) that medicine is a mix of natural and social sciences, while Stütz et al. (Citation2015) identify global health education as a relevant component of internationalisation in medicine. All programmes are at the bachelor level and similar in length (three years) and have been working on curriculum internationalisation for at least a decade, which provides a fair comparison and allows for some theoretical generalisation.

Interviews

To research the perceptions and experiences of the academic staff, we conducted semi-structured, in-depth interviews (Kvale, Citation2007) with seven or eight academics per programme, 29 in total. Our sample of interviewees consists of 20 male and nine female staff, 14 Dutch and 15 non-Dutch; 18 already worked in this university in 2012. All academics combine teaching with research and some administrative tasks. We purposefully selected academics such that all research communities related to the selected programmes are represented, with at least one academic per case who has been in charge of curriculum changes. Moreover, for each programme, we included the current academic programme director. All academics we selected have worked with curriculum internationalisation in their programme for some time. Our interview script follows our research question with curriculum internationalisation, resources and processes. The interviews lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. We recorded all interviews and the interviewees agreed to the verbatim transcripts. Then, we constructed the timelines per case, which the programme director validated. A single interviewer conducted the interviews between June 2020 and March 2021. The first ten interviews were on-site; the other 19 were online due to the COVID pandemic. The consistency in script and interviewer ensured a similar approach in all interviews (Gibbs, Citation2008).

Thematic, comparative analysis across time

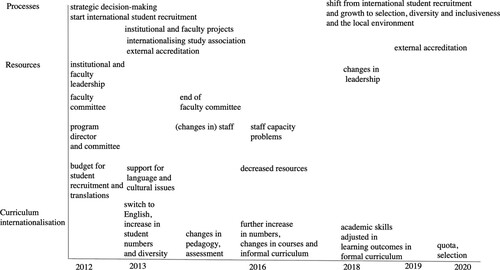

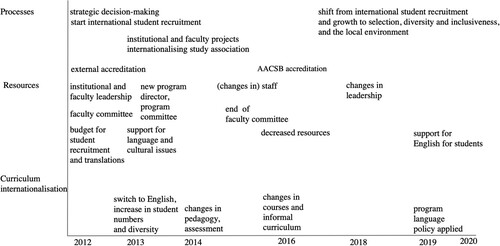

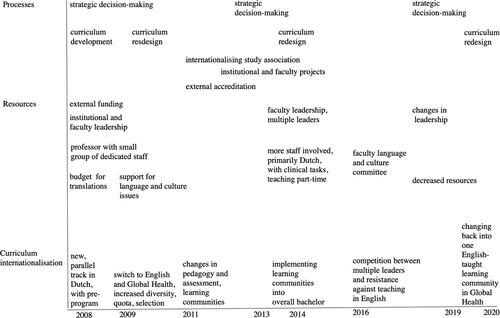

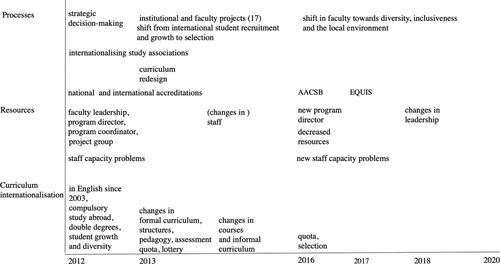

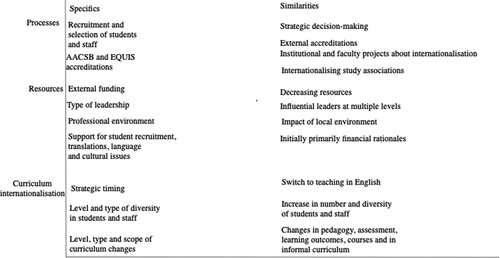

In our analysis, using NVivo, we started with a data-oriented, open approach to include emerging issues (Saldana, Citation2016). Next, we encoded the themes recurring across all four programmes with curriculum internationalisation as ‘language (English and Dutch), diversity (in students and staff), recruitment and selection’, resources as ‘financial and human resources’, and processes as ‘top-down, strategic’ versus ‘bottom-up, experiential’. The two authors regularly discussed decisions and interpretations. Following Saldana’s approach to reviewing data across time in a thematic, comparative analysis (p. 261), we use a visual timeline approach with historical narratives to display the specifics and the similarities across our four cases. The horizontal axis reveals the main developments with curriculum internationalisation as an organisational change process from 2012 to 2020, while the vertical axis shows the investigated codes. For more details of the timelines, see a–d.

Findings

Specifics and similarities

We visualise and describe the specifics and similarities per case across time, followed by a summary of all cases in .

Computing science

shows that, in 2013, following strategic decision-making, Computing Science switched to teaching in English as one of the first bachelor programmes in natural sciences in mainland Europe. The primary rationale was to increase the number of students and revenues. Process-wise, the language switch resulted in rapid student growth from 125 to 300 students in 2020 including 50% international, and 80% international staff. Initially, curriculum internationalisation was about international student recruitment, language and cultural issues. However, when leadership changed, attention shifted to diversity, inclusiveness and the local environment. In 2016, resources for curriculum internationalisation decreased after completing the switch to English and achieving the intended student numbers. The figure illustrates that the programme has made some changes in pedagogy, assessment, courses, learning outcomes and the informal curriculum (e.g., internationalising study association), but no significant curriculum changes took place. A major change, however, concerned the implementation of quota and selection mechanisms in 2020. In the internationalisation process throughout this period, leadership and projects at multiple levels have played an important role together with external accreditations and resource scarcity in recent years.

Industrial engineering and management

demonstrates many similarities with . Likewise, this interdisciplinary programme connecting natural and social sciences in a business context, situated in the same Faculty, switched to teaching in English in 2013 for the same reasons. This programme in Industrial Engineering and Management mainly experienced the same developments as Computing Science with curriculum internationalisation, resources and processes, and also has a high number of international staff (70%). Differently, the programme has grown less rapidly (from 113 to 158 students in 2020) and attracted fewer international students (15%). The programme has not faced similar capacity problems or worked with a quota or selection procedure. Further, accreditation from the business domain (AACSB) has influenced processes, and the programme pays more attention to students’ language development.

Global health

shows the developments of Global Health as a track in the bachelor of medicine. This track is an interdisciplinary programme connecting natural and social sciences, preparing for a Dutch-taught master and the medical profession in the Netherlands. Unlike the previous cases, this track was initially developed in Dutch with a pre-programme driven by substantial external funding to educate students from Saudi Arabia. Despite the primary financial rationales, a small group of dedicated staff chaired by a newly appointed professor managed to develop an English-taught track in Global Health. The track attracted a highly motivated, diverse group of students and became popular because of its innovative, highly interactive learning communities approach. However, when the faculty leadership implemented this approach into the overall bachelor programme, there was much resistance from the primarily Dutch staff against teaching in English. Competition arose among the leaders involved. Subsequently, the faculty leadership intervened and redesigned the curriculum towards convergence, changing Global Health back into a single English-taught track, with 25% international students and few international staff. The figure illustrates contextual influences from leadership, resources and accreditations, and changes in the study association similar to the other cases. Differences are the significant formal curriculum changes, the language approach and the professional environment of a primarily Dutch hospital and local culture, in which clinical revenues and a quota set by the national government play a critical role.

International business

Lastly, demonstrates the developments with International Business, a social science programme. In 2012, the programme was already taught in English (since 2003) with a compulsory study abroad module and double degree arrangements, and had experienced a rapid increase in student numbers and diversity. There was a significant curriculum redesign in 2013 to address capacity problems with a tighter organisational structure and establish more research-driven education. Since then, curriculum changes driven by internationalisation have been small-scale and informal, driven by (changes in) individual staff. Similar to Industrial Engineering and Management, international accreditations (AACSB, EQUIS) have played a relevant role. In 2020, International Business counted 40% international students and 50% international staff. The figure illustrates that the contextual influences of accreditations, leadership and resources are similar to the other cases.

Perceptions and experiences from interviewees

To better understand how these specifics and similarities influence academic staff engagement with curriculum internationalisation in disciplinary contexts, we analysed the perceptions and experiences of our interviewees.

Individual drivers

Regardless of their discipline or other contextual influences, all interviewees disclose that they have strong drivers for curriculum internationalisation, which stem from their interest and commitment to their students’ and societal needs, teaching and research. They experience their engagement with internationalisation as an essential part of their personal and professional identity. An academic who has worked on projects with Africa and Asia for many years shares how his personal identity engages him with curriculum internationalisation:

I believe in the value, I want to realise it and I want to continue it. So, therefore, I walk around and run for it, take a risk and take the blame if things go wrong. You need that with internationalisation (International Business).

Health care does not stop at national borders. Health is, by definition, an international subject, so a focus on global health is only logical (Global Health).

Resource management

In all four programmes, however, particularly in the last years, the participants perceive a general scarcity of financial resources (money, time, and support) and a lack of leadership and role models (human resources) for further internationalisation. Still, what bothers them most is not being recognised for their teaching as much as for their research, let alone for teaching in an international context. They also feel that shared responsibilities and ownership, and a lack of time for reflection impede their engagement with curriculum internationalisation. A senior academic, who chaired a faculty internationalisation committee for several years, experiences a difference in resource requirements between internationalisation and the international classroom:

An international classroom demands more organisation and resources. For us, internationalisation is logical and natural, but an international classroom is different and requires us to consider the consequences of internationalisation for our program and our students. (Computing Science)

I have no control over resources. I am in the middle of the matrix. I talk to everyone and try to put it all together in a strategic and smart way (International Business).

Strategic alignment

Furthermore, the participants disclose that a lack of strategic alignment also hinders their engagement with curriculum internationalisation. In their experience, internationalisation is not embedded in what they consider ‘top-down, strategic processes’, like curriculum and professional development. A senior academic reveals:

The general feeling in the faculty is that internationalisation has been established, but it is still an extra, undertaken by a few enthusiastic people. (International Business)

Disciplinary influences

The participants’ perceptions and experiences reveal four disciplinary influences.

First, working in a research-based university, all participants consider research an important influence in their programmes. The academics in Global Health add that research and teaching are secondary to the medical profession. A participant active in teaching, research, and clinical work explains:

The clinical staff have a powerful position because they ensure the main revenues. In clinical departments, teaching has the lowest priority. We have approximately 200 teachers involved in our program in minimal parts. I call it a fly-in, fly-out system. (Global Health)

A third disciplinary influence is the programme profile that impacts the recruitment and selection of students and staff. Apart from the Global Health track, all programmes were existing programmes that switched to English. Consequently, the academics experience limited space for curriculum changes. The programmes build on available expertise, networks and routines, and have to be distinctive from their main competitors. Still, the two natural science programmes managed to improve their profile globally. Both programmes now provide excellent employability prospects worldwide and attract considerably more female students as well as students with more diverse backgrounds. The recruitment and selection of staff is particularly difficult for Computing Science and International Business, who face severe global competition, especially from industry. For Global Health, national guidelines and quota determine the programme profile, selection and recruitment.

Together with the programme profile, the international reputation of the research group and university is a strong influence in attracting staff, while external accreditations are relevant for recruiting and selecting students, especially for the two business programmes. For example, several academic staff have prepared critical reflections for AACSB or EQUIS. They recall how these accreditations have pushed them to look more critically at the organisation’s local culture and structures, and how to advance their students’ global employability outcomes.

A fourth disciplinary influence is the community in which these academics work. We learned that teachers in a single programme belong to three to seven research communities. They feel that their different communities and physical locations for teaching and research complicate their engagement with curriculum internationalisation. In all programmes, some view themselves as ‘outsiders’ to the core group and sense they compete for space in the curriculum. According to all participants, student and staff diversity can add value to their programmes, but this requires investments in relations and an effective organisation. Some interviewees emphasise that diversity is much more than ‘counting passports’ and involves educational and research backgrounds, personal characteristics and experiences. The level and type of diversity of students and staff differs strongly between these four programmes.

Next, we describe how these disciplinary influences affect the academics’ engagement with curriculum internationalisation in each programme as perceived and experienced by the participants.

Disciplinary dynamics

The participants from all disciplines disclose a dual perspective of curriculum internationalisation. On the one hand, they consider their programmes already considerably international based on their global research and networks, the number of international students and staff, and the use of English as a medium of instruction. On the other hand, they focus on applied, contextual dimensions for further curriculum internationalisation. Disciplinary differences appear in their perceptions and experiences of how to do this and what can be changed.

In Computing Science, the natural science programme, the programme director expresses how he has experienced duality with internationalisation:

For us, internationalisation is inherent to our program. Programming is programming, so to say, a mathematical process based on universal knowledge and principles, independent of people, nationalities and language. But after graduation, our students work in teams in many different contexts. We need to prepare them for this. (Computing Science)

Our technical engineering content is, by definition, international but our next steps in internationalisation should be how to address diversity, ethics, sustainability and innovation more explicitly in our business context. (Industrial Engineering and Management)

We are an international program in a Dutch institutional and local culture. These two worlds in parallel create continuous tensions with, for example, language and diversity, which we need to be aware of and address appropriately. (International Business)

A heartbeat is the same everywhere, based on physiology. But how you deal with it is different depending on the specific context. It involves ethical issues and social interaction. (Global Health)

Institutional culture and structures

Finally, many participants, particularly the non-Dutch, signal dilemmas due to working in a globally oriented university with a strong local culture and structures, and a primarily national education, accreditation, and funding system. For example, they refer to national regulations that sometimes limit their opportunities to adjust pedagogy, assessment and grading systems. The non-Dutch participants struggle to learn the national language and do not always feel included and valued by the organisation. An international academic who has worked at the university for a few years reveals:

I often feel I am a minority, a forgotten group with different needs. This is apparently new to the university. There is no adequate information and support for us yet. (Industrial Engineering and Management)

An international participant on a 5-year tenure track shares his tensions:

Learning Dutch is an extra requirement for international staff and a formal criterion for me to get a permanent position. Yet, I do not have the time to learn nor the opportunities to practice with mostly international staff around me, and all meetings in English (Computing Science).

Discussion

Contexts

Firstly, contrary to the literature about the presumed disengagement of academic staff with curriculum internationalisation as observed by Leask et al. (Citation2020), these academics reveal strong individual drivers in line with their personal and professional identities. Moreover, they provide evidence of their many achievements with internationalising their programmes. As Kahn (Citation2010, p. 22) explains, ‘people engage when they feel that, on balance, it matters to do so’. This finding affirms that staff engagement takes many different forms, some of which may not be easily observable (Whitsed et al., Citation2021). However, the duality and lack of specific expertise and purposeful collaboration that these academics perceive and experience with curriculum internationalisation complicate their shared understandings and imply a risk that no further actions will be taken. As Kahn points out, apart from individual drivers, staff also need cognitive and affective competencies plus opportunities to be able to engage. In short, these academics have strong individual drivers, yet they lack specific competencies and opportunities to further internationalise their programmes.

Secondly, we discovered that the participants’ disciplinary contexts considerably impact their engagement with curriculum internationalisation. Unlike Clifford in Trowler et al. (Citation2012), we found no evidence of less staff engagement in the natural sciences. Instead, we identified influences and dynamics across all four cases that create specific perceptions and experiences with curriculum internationalisation in each programme. Our research also reveals that all four programmes involve academics working in different, highly diverse research communities. They explain how the cross- or interdisciplinary character of their programmes, involving academics from multiple research, educational and cultural backgrounds, interconnected with their international networks, makes it more difficult to collaborate and create shared understandings with curriculum internationalisation. As Trowler et al. (Citation2012) stress, the increase in interdisciplinary research and education, and more focus on students’ academic skills pose conflicting and changing demands on academic staff, who may need to develop new knowledge and competencies. Yet, our findings also disclose that academics still work in disciplinary communities that share particular values, knowledge paradigms and ways of thinking, working, and communicating (Becher, Citation1994). As Pharo et al. (Citation2014) warn, disciplinary fragmentation is a serious concern, and we need to pay more attention to interaction and collaboration within and across disciplines, for example, through communities of practice. With more interdisciplinary programmes, smaller communities and more diversity in staff, academics face many tensions in their disciplinary context that impact their engagement with curriculum internationalisation.

Thirdly, the participants in this study disclose how their institutional context also influences their engagement with curriculum internationalisation. The strategic timing (when) of the language switch played a significant role and confirms the relevance of a comprehensive approach to organisational change (Pettigrew, Citation1987; Pettigrew et al., Citation2001). The interviewees disclose how the diversity of beliefs, assumptions, language and structures affect their work. As Mir et al. (Citation2020) explain, organisations have become increasingly pluralistic, which demands the acknowledgement of the co-existence of normative assumptions and discourses, and the development of new organisational mechanisms for strategic alignment.

Resources

Fourthly, the competition for resources that these academics experience increases their feeling of working in ‘disciplinary silos’. The lack of recognition and support from their leadership for further curriculum internationalisation makes them feel less connected to their organisation and colleagues beyond their own research community, affirming Kahn (Citation2010). This inadequate management of resources hinders effective organisational changes with curriculum internationalisation, similar to the findings of Boonstra et al. (Citation2014), with complex changes in health care. As Eisenhardt and Martin (Citation2000) and Smith and Graetz (Citation2011, pp. 89–104) explain, organisations must leverage their resources carefully to initiate and sustain change.

Processes

Lastly, our comprehensive approach to organisational change unveils how the participants experience curriculum internationalisation as a stand-alone process, not linked to strategic processes like curriculum and professional development. Consequently, they feel they can only accomplish smaller changes in their experiential work with curriculum internationalisation. Our findings demonstrate that engaging these academic staff with longer-term changes regarding curriculum internationalisation requires an organisational change approach balancing top-down, strategic and bottom-up, experiential processes to leverage duality with curriculum internationalisation.

A comprehensive framework of organisational change

Our study has further developed our framework to guide policymaking, practice and research. below shows the additions to in italics.

With the context (external and internal) of curriculum internationalisation as an organisational change process, our research adds the relevance of strategic timing (when) to multiple rationales (why), levels (where) and stakeholders (who). The internal context includes individual, disciplinary and institutional influences

The contextual disciplinary influences we identified are research & profession, student employability outcomes, programme profile & accreditations, and community & diversity

For the content, our research confirms that what to change involves educational and organisational dimensions, and the process affects the scope and type of change

With the process, our study adds to the plans, actions, reactions and interactions, and complements balancing top-down and bottom-up with strategic and experiential

Our research shows that adequate management of financial and human resources, particularly recognition and support from leadership, is essential for the engagement of academic staff with curriculum internationalisation

Our study demonstrates that academic staff engagement with curriculum internationalisation requires drivers, cognitive and affective competencies, and opportunities

Finally, our study adds that curriculum internationalisation requires conceptual clarity to create shared understandings of curriculum internationalisation as a prerequisite for academic staff engagement.

Implications

Programmes provided and managed by academics working in various disciplinary communities put specific requirements on disciplinary approaches and resource management to engage academics in organisational change processes with curriculum internationalisation. Firstly, if programme leaders want to establish shared understandings of curriculum internationalisation in a programme, then they should stimulate discussions about collective drivers. Secondly, if programme leadership aims to engage academic staff in activities with curriculum internationalisation, then they must recognise disciplinary and individual achievements and competencies, and build on these assets to create opportunities. Thirdly, if programmes strive for longer-term changes with curriculum internationalisation, then this demands programme leaders to align curriculum internationalisation strategically with recommendations from accreditations, curriculum design and professional development, and facilitate interactions and collaborations within and across disciplines.

For future research, we recommend similar longitudinal, comparative case studies beyond Western Europe and with academic in various disciplinary communities and higher education institutions to develop our understanding of the impact of individual, disciplinary and institutional contexts on academic staff engagement with curriculum internationalisation. Such research investigating curriculum internationalisation as a continuous, comprehensive organisational change process over a period of time can further clarify the impact of contextual features and resource management on academic staff engagement with curriculum internationalisation (e.g., Eisenhardt & Martin, Citation2000; Pettigrew et al., Citation2001).

Conclusion

This research demonstrates that academic staff experience many tensions in their disciplinary contexts, which hinder their engagement with curriculum internationalisation. Still, all academics in this study acknowledge the relevance of curriculum internationalisation and show evidence of how international their programmes are already. Contrary to frequent assumptions about poor academic staff engagement, these academics have surprisingly strong drivers for curriculum internationalisation based on their personal and professional identity, confirming Kahn (Citation2010) that individual drivers are essential in staff engagement.

Further, our findings show disciplinary influences and dynamics that create specific perceptions and experiences of academic staff with curriculum internationalisation in each programme. Our research highlights the significance of the disciplinary context, an area largely overlooked in research and practice within higher education. Following Becher (Citation1989, Citation1994) and Trowler et al. (Citation2012), our study provides further details on the enduring impact of disciplines and the increased relevance of interdisciplinary spaces. We identified the need for an organisational change approach, based on Pettigrew (Citation1987), in line with the disciplinary context to engage academic staff and achieve longer-term changes with curriculum internationalisation to advance and innovate study programmes.

This article’s academic contribution is in providing a broader, contextualised understanding of academic staff engagement with curriculum internationalisation by applying a comprehensive approach to organisational change instead of a rational change perspective as used in the existing higher education literature. The contribution to policymaking and practice is a change approach that connects the specific context with the content of what to change in teaching, learning and organising with curriculum internationalisation, and with the process of how to do this, with adequate management of financial and human resources.

Acknowledgements

Dr Craig Whitsed from Curtin University in Perth, Western Australia, and Professor Robert Coelen and Professor Albert Boonstra from the University of Groningen in Groningen, the Netherlands, contributed to this article as supervisors of this PhD project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agnew, M. (2013). Strategic planning: An examination of the role of disciplines in sustaining internationalization of the university. Journal of Studies in International Education, 17(2), 183–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315312464655

- Becher, T. (1989). Academic tribes and territories. Intellectual enquiry and the culture of disciplines. The Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

- Becher, T. (1994). The significance of disciplinary differences. Studies in Higher Education, 19(2), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079412331382007

- Boonstra, A., Versluis, A., & Vos, J. F. J. (2014). Implementing electronic health records in hospitals: A systematic literature review. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-370

- Burke, W. W., & Litwin, G. H. (1992). A causal model of organisational performance and change. Journal of Management, 18(3), 523–545. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639201800306

- Crosling, G., Edwards, R., & Schroder, B. (2008). Internationalizing the curriculum: The implementation experience in a faculty of business and economics. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 30(2), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800801938721

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21(10/11), 1105–1121. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3094429. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0266(200010/11)21:10/11<1105::AID-SMJ133>3.0.CO;2-E

- Gibbs, G. R. (2008). Analysing qualitative data. Sage.

- Green, W., & Whitsed, C. (Eds.). (2015). Critical perspectives on internationalising the curriculum: Reflective narrative accounts from business, education and health. Sense.

- Kahn, W. A. (2010). The essence of engagement: Lessons from the field. In S. Albrecht (Ed.), Handbook of employee engagement. Perspectives, issues, research and practice (pp. 20–30). Edward Elgar.

- Kuipers, B. S., Higgs, M., Kickert, W., Tummers, L., Grandia, J., & Van Der Voet, J. (2014). The management of change in public organizations: A literature review. Public Administration, 92(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12040

- Kvale, S. (2007). Doing interviews. Sage.

- Leask, B. (2015). Internationalizing the curriculum. Routledge.

- Leask, B., Whitsed, C., de Wit, H., & Beelen, J. (2020). Faculty engagement: Moving beyond a discourse of disengagement. In A. Ogden, B. Streitwieser, & C. van Mol (Eds.), Education abroad: Bridging scholarship and practice (pp. 184–199). Routledge.

- Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science. Harper & Row.

- Marantz-Gal, A., & Leask, B. (2020). Internationalizing the curriculum: The power of agency and authenticity. New Directions for Higher Education, 2020(192), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.20390

- Mir, F. A., Rezania, D., & Baker, R. (2020). Managing change in pluralistic organizations: The role of normative accountability assumptions. Journal of Change Management, 20(2), 123–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2020.1720776

- Pettigrew, A. M. (1987). Context and action in the transformation of the firm. Journal of Management Studies, 24(6), 649–670. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1987.tb00467.x

- Pettigrew, A. M., Woodman, R. W., & Cameron, K. S. (2001). Studying organizational change and development: Challenges for future research. The Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 697–713. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3069411

- Pharo, E., Davison, A., McGregor, H., Warr, K., & Brown, P. (2014). Using communities of practice to enhance interdisciplinary teaching: Lessons from four Australian institutions. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(2), 341–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.832168

- Riebe, L., Whitsed, C., & Girardi, A. (2021). Exploring the paradoxes and tensions encountered by business faculty teaching teamwork in a changing academic environment. Higher Education Research & Development. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1979939

- Riezebos, J. (2017, March 21). Towards better education [inaugural lecture]. The University of Groningen. https://janriezebos.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/InaugurationRiezebos-1.pdf

- Saldana, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage.

- Smith, A. C. T., & Graetz, F. M. (2011). Philosophies of organizational change. Edward Elgar.

- Stütz, A., Green, W., McAllister, L., & Eley, D. (2015). Preparing medical graduates for an interconnected world: Current practices and future possibilities for internationalizing the medical curriculum in different contexts. Journal of Studies in International Education, 19(1), 28–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315314536991

- Trowler, P., Saunders, M., & Bamber, V. (2012). Tribes and territories in the 21st century. Rethinking the significance of disciplines in higher education. Routledge.

- van den Hende, F., Whitsed, C., & Coelen, R. J. (2022). An organizational change perspective for the curriculum internationalization process: Bridging the gap between strategy and implementation. Journal of Studies in International Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/10283153221105321

- Whitsed, C., Gregersen-Hermans, J., & Casala Sala, M. (2021). Engaging faculty and staff in internationalization. In D. Deardorff (Ed.), The handbook of international higher education (pp. 325–342). Stylus.

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research. Design and methods. Sage.