ABSTRACT

The coronavirus pandemic resulted in universities rapidly changing how courses are delivered. Many traditionally on-campus courses have been adapted to be taught online, or in a hybrid manner with a mix of online and on-campus classes. This rapid shift in pedagogy and delivery mode has disrupted long-standing patterns of teaching and learning in higher education and has also presented a unique challenge for university staff with leadership roles. This project uses a UK university as a case study to understand how staff with educational leadership roles have handled the challenge of supporting their staff to adapt their teaching, making key decisions about how to implement aspects of hybrid teaching, and how lessons from their experiences of the pandemic period can guide future decision-making and support from senior management.

Introduction

As a result of the coronavirus pandemic, higher education (HE) institutions have had to rapidly adapt from in-person teaching to blended or online-only modes of delivery, which many are now referring to as Emergency Remote Teaching (Hodges et al., Citation2020). This rapid shift in pedagogy and delivery mode has disrupted long-standing patterns of teaching and learning in all settings and levels, particularly in the UK, although it has now been widely adopted globally in response to the pandemic (Crick et al., Citation2021). Indeed, Covid-19 has accelerated or brought about what many in recent years have referred to as digital transformation in HE (Brooks & McCormack, Citation2020; Marshall, Citation2018; Selwyn, Citation2016). Given the vital role that education leaders have played in negotiating the changes in HE, there is little research that effectively captures those experiences and guides future planning and decision-making (Crick et al., Citation2021). This is one of the aims of our study.

The Covid-19 pandemic has caused a mass exodus from in-person teaching toward some degree of online teaching. Aspects of online teaching include instructional design, internet-based content delivery and interaction with students in synchronous and asynchronous environments; each demands a variety of new requirements related to technology operation, teaching skills, and management (Zhang, Citation2020).

There are many terms to define the amount of online interaction with students depending on the location and timing of interactions (Irvine, Citation2020) – the most common tend to be fully online, hybrid, and blended. According to Allen and Seaman (Citation2010), any course with more than 80% of its teaching/content online is classed as an online course, while in comparison, at least 30% of a class needs to be facilitated online for it to be considered blended. Online models of learning have existed in HE for quite some time but have been less common among undergraduate students where educators have traditionally used more blended models of learning that combine face-to-face teaching with technology-mediated instruction (Graham & Dziuban, Citation2008). The benefits of blended models of learning have been well documented (see Smith & Hill, Citation2019 for a review).

In contrast, hybrid models of learning are defined by the intentional use of technology to combine different cohorts of students together (i.e., those in-person, and those online, through a combination of asynchronous and synchronous teaching activities). The term ‘hybrid’ was often used interchangeably with ‘blended’ in the HE learning context and its use by researchers and practitioners was amplified during the pandemic (Irvine, Citation2020). Flexibility with the number of online activities in hybrid models can alleviate pressure on physical space and allow for more flexible class scheduling (Saichaie, Citation2020). Hybrid teaching is also able to offer more individualised learning content to a more diverse audience and has been associated with higher student engagement and retention (Moore & Fetzner, Citation2009). For these reasons HE institutions have adopted hybrid teaching approaches dominantly since the start of the pandemic. Hybrid models have also allowed most teaching content to be delivered online, while maintaining practical workshops on campus in line with social-distancing measures (Crick et al., Citation2020). Hybrid approaches therefore offer flexibility in accommodating students’ learning needs, different geographical locations of students, and rapidly changing social distancing laws (Skulmowski & Rey, Citation2020). Despite the various benefits and flexibility hybrid teaching can offer (see Raes et al., Citation2020 for a review), recent research by Watermeyer et al. (Citation2021) surveyed 1,148 academics across the UK on what they refer to as ‘afflictions’ and ‘affordances’ of the digital pivot in HE. The data collected during the first nationwide lockdown in the UK captured initial reactions from academics in a range of subject disciplines. The study generally found discontent among academics about poor student evaluation of their teaching, challenges relating to student recruitment, and highlighted some common misconceptions such as a perceived lack of freedom with pedagogical styles. Other concerns included the imbalance of workload affecting female staff disproportionately more, and the commercialisation of HE. These are relatively long-standing views that have been documented among academics around hesitancy and suspicion about digital transformation (Blackmore, Citation2020; Marshall, Citation2018; Selwyn, Citation2017). The pandemic, however, did not give staff any choice around implementing this change, and the speed at which institutions have had to do this over the course of the pandemic is unprecedented, resulting in staff burnout, particularly among those that have had to lead on teaching strategy. Hodges et al. (Citation2020) state that this is confounded by the fact that the level of support that would have been received by the faculty to implement pedagogical changes for online learning in normal times was not available at scale during the pandemic. In this situation, Hodges et al. (Citation2020) say the temptation is often to compare online to face-to-face education, as staff have done in the Watermeyer et al. (Citation2021) study, where a relatively negative picture is painted. It is worth noting, however, that the pandemic has quickened the inevitability of digital change and it therefore may not have received a fair trial. It has, nonetheless, offered an opportunity that has brought to surface some deeper issues that need to be reconsidered in any digital offering that affects leadership staff and their role to support digital transformation. These include (i) ensuring equitable education, (ii) the adapted role of the tutor, (iii) sustainability of workload, and (iv) communicating with university leaders on decision-making.

Digital transformation, such as implementation of hybrid models of teaching/learning at the institutional level, requires ‘a series of deep and coordinated culture, workforce, and technology shifts that enable new educational and operating models and transform an institution’s operations, strategic directions, and value proposition’ (Brooks & McCormack, Citation2020, p. 5). In a study about the learning experiences of academics who had adopted a blended teaching model before the pandemic, Huang et al. (Citation2021) found that implementing blended learning requires technical and pedagogical support for staff who otherwise felt that the lack of autonomy in making key decisions about blended learning was a demotivating factor and made them question whether it was worth the upheaval of current practice. The study also found that academics did not feel cared for by the university and that there was too often a mismatch between expectations and the reality of what their learning and teaching practices looked like. It is not yet known whether these sentiments will be shared by leadership staff who have not had a choice to participate in the digital transformation required because of the pandemic.

Cavanagh et al. (Citation2017) note four key factors to support HE institutions to administer hybrid/online teaching. These are: (i) academic support, (ii) technical support, (iii) faculty readiness, and finally (iv) student readiness. Similarly, others have suggested implementing blended or hybrid teaching models requires prior technical and pedagogical support from university leaders that should include elements of professional development, which is an important indicator to academics that their efforts are recognised and sustainable (Han et al., Citation2016).

This is an interesting finding and one that Smith and Hill (Citation2019) highlight as an area with very little research literature; staff are crucial to the design and facilitation of blended and hybrid models, yet very little existing research considers the role of academic staff and their professional development in facilitating implementation of novel pedagogical practices. The role of educational leaders to support and develop the skills of staff is crucial to successful pedagogical change in general. During the shift to hybrid teaching, educational leaders at a departmental level often had the responsibility of supporting staff in rapidly negotiating the transition and interpreting institutional policy. Educational leadership requires a particular skillset; Fink emphasises that

[p]eople who have the potential to learn how to analyse contexts, understand learning, think politically and critically, possess emotional understanding, think imaginatively about the future, and make connections can within a well-developed succession management program become leaders of learning who will make a difference to the learning of all students, in ways that top-down policy initiatives never have and never will. (Citation2010, p. 48)

The aim of this study was to understand the experiences of university staff in educational leadership positions in order to better support them to carry out their role to support and enhance teaching in an ever-changing landscape. These staff were responsible for influencing or interpreting the policy for online and hybrid teaching, or for supporting other staff to teach in new ways. Our research questions were as follows:

How did educational leaders across the university change their approaches to supporting the teaching done by instructors in response to the pandemic?

What barriers and opportunities have educational leaders encountered during the switch to hybrid teaching?

Case context

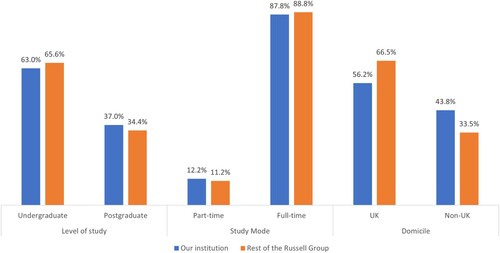

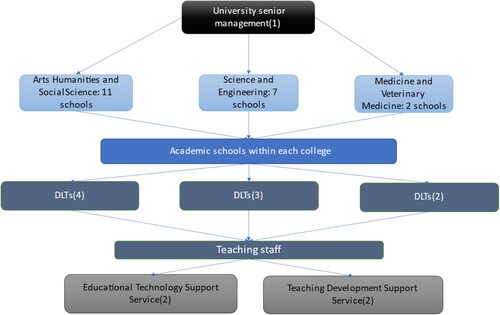

UoE, located in Scotland, is a member of the Russell Group of large research-intensive UK universities which together teach one-quarter and one-third of the UK’s undergraduate and postgraduate students respectively. As Russell Group universities worked together on a high-level response to the impact of the pandemic on teaching,Footnote1 aspects of the case study of UoE will likely be relevant to other Russell Group members and their research-intensive counterparts internationally. At UoE, 64% of its 34,000 students come from outside the UK. In terms of numbers regarding level of study, mode of study and domicile of students, it is quite comparable to the rest of the Russell Group universities (see ). It has three Colleges, each of which consists of multiple academic Schools offering a series of degree programmes in broadly related disciplines. Key respondents in this study are Directors of Learning and Teaching (DLTs) because these academic staff members are central to teaching support and development across clusters of related academic disciplines. They typically do not line-manage individual teaching staff but are educational leaders among their academic peers. The responsibilities of this role include overseeing teaching and learning activities, leading the strategic direction of teaching within the School, advising the Head of School on teaching matters, chairing teaching-related committees, and promoting quality assurance. DLTs report to the Head of School and meet with their counterparts within the College. There is also a department (teaching support service seen in ) that has the remit of supporting teaching, learning and researcher development across the University including events, courses and written resources for staff and students. UoE also has a support service providing technological infrastructure and technical training for staff.

Since March 2020, Scotland navigated a series of lockdowns and restrictions according to fluctuations in infection rates. UoE, in accordance with UK government restrictions, was placed under ‘lockdown’ on the 23 March 2020. This meant staff and students were no longer able to attend the university and on-campus teaching had to rapidly shift online for the remainder of the Spring 2020 term. Note, at this point the term ‘hybrid’ was not used. During the Autumn 2020 term, some staff and students were available to attend on-campus classes during periods of reduced restrictions, but many were unable to travel to Scotland and therefore attended classes online. Spring 2021 term occurred during another national lockdown, so most staff and students attended online classes. From the summer of 2020, the university adopted hybrid teaching and this approach was guided by an internal report, which stated that it ‘does not assume either a fundamentally on-campus or fundamentally online model but is designed for easy student transition between the two; it does not separate online and on-campus cohorts but focuses on bringing them together.’

In addition to this guiding document, online resources, seminars and courses that were already in place before the pandemic, the teaching staff were offered additional professional learning support on hybrid pedagogy, including a bespoke intensive course, drop-in sessions for just-in-time answers, school-level learning design workshops, and online workshops/seminars about hybrid teaching.

Methods

An exploratory qualitative approach was chosen as little was known about how educational leadership shaped the response to hybrid learning during a crisis/pandemic. Qualitative research enables the researchers to explore an issue and develop a detailed understanding through the perspectives of participants (Creswell & Guetterman, Citation2021). A total of 14 staff were recruited.

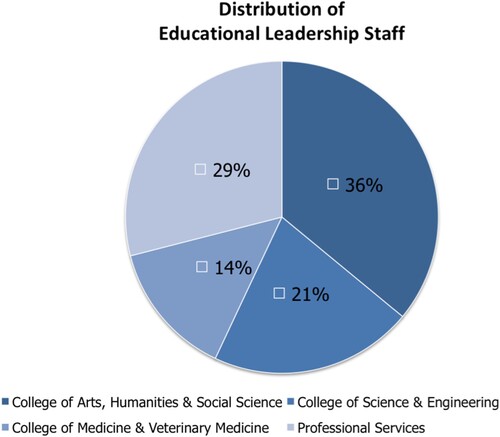

Participants were recruited through purposively sampling all DLTs across the university, alongside other specific individuals in a leadership role as described above who were recruited specifically to understand how they supported DLTs and for an holistic view of how teaching changes were implemented (). A detailed sampling strategy is included in Appendix 1 (See online supplemental materiel). The College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences Ethics Board, adhering to British Educational Research Association guidelines, granted ethical approval for this study.

Staff were interviewed individually for approximately 50 min via Microsoft Teams. All interviews were recorded and fully transcribed for data analysis purposes. A semi-structured interview format was used whereby all staff were asked the same core research questions, and these were followed up with additional questions based on staff responses. Depending on staff roles, additional questions specifically about their role in the context of the digital pivot to hybrid were also asked. A copy of the interview questions and how they correspond to our research questions is available in Appendix 2 (See online supplemental materiel).

Figure 3. Breakdown of staff academic area/college.

Note: Professional Services include those working in Technology and Teaching Support Services.

The interview transcriptions were uploaded onto NVivo (QSR, Citation2018) software to conduct a Reflexive Thematic Analysis (see Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2019 for methodological steps for analysis). This approach was chosen because it allowed inductive qualitative analysis of the data and captured the role of the researchers in their interpretations. This was necessary as all authors were in employment at the university at the time of data analysis. This method also allowed us to formulate a narrative of the experiences of staff who were themselves still in the process of reflecting on a challenging time in their careers. All transcripts were coded to minimise selection bias. After data were repeatedly read, initial codes were identified and coded inductively by one of the researchers. The codes were shared with the other two researchers, and they were discussed, re-applied to the data and refined. We then moved toward developing latent themes within the data where themes were developed into an initial thematic map, which was also then iteratively re-designed based on further analysis using the steps outlined in Braun and Clarke (Citation2006).

Findings

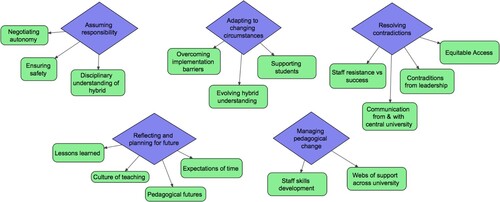

Our thematic analysis revealed five broad themes that emerged from the data (). Each theme revealed an aspect of leadership that staff at UoE had to navigate while undergoing a digital shift in teaching during a crisis. These themes were: (i) assuming responsibility, (ii) adapting to changing circumstances, (iii) managing pedagogical change, (iv) resolving contradictions, and finally (v) reflecting and planning for the future. While our research questions sought to highlight how leadership staff changed their approaches to supporting teaching done by instructors in response to the pandemic and the barriers and opportunities they encountered, participant conversation centred around the various responsibilities staff had assumed and their role in implementing online/hybrid teaching. These themes captured the unique experiences of leadership staff, specifically in how their roles changed during the crisis.

Figure 4. Thematic Map – five broad themes were identified that reflect the key responsibilities for educational leaders.

We now provide a summary of our themes. For more detailed explanation of how themes were generated and more exemplars, please refer to Appendix 3 (See online supplemental materiel).

Assuming responsibility

As educational leaders of learning, staff had to take on unique responsibilities outside of their usual role. This included adopting the university-wide hybrid teaching response, yet also having to understand what hybrid could look like for their individual disciplines to allow them to support their staff in adapting their teaching. Many appreciated the opportunity to assume a level of autonomy for their school/department in making these decisions that was more than the level of responsibility they had pre-pandemic. This indicated that the pandemic presented an opportunity for educational leadership to assume more responsibility in the strategic direction and management of their teams.

While staff appeared to appreciate the level of autonomy they were given, some staff noted that there was a lack of clarity as to whether this was part of their role, given the guidance from the university did not articulate the specific level of autonomy schools had to implement hybrid. These sentiments typically appeared very early on during the crisis when expectations of leadership staff were not made clear. Incidentally, this appeared at odds with the perspective of one participant with a senior leadership role who emphasised schools were always expected to take the broad institutional definition of hybrid and implement this as they saw fit for their individual disciplines. There was therefore a mismatch between senior leaders passively assuming DLTs would undertake this responsibility, and DLTs being unsure about how much autonomy they actually had, evidently because they had previously never had this much responsibility pre-pandemic:

… because of the highly devolved nature of the University … schools have … the autonomy and … power to decide how they deliver their teaching and that's as it should be. (P7)

Negotiating autonomy therefore required educational leadership staff to take on a scholarly role of interpreting what hybrid teaching would look like for their individual disciplines. This was a lengthy process and involved taking a pedagogical approach in thinking with colleagues about what the core learning objectives for each course were and how they could be met without the guarantee of face-to-face interaction or assessment. For example:

For us it's … cohort-building activities that we feel are important. We've got certain courses … that bring together the students of that year, and we would like to actually have the students together and meet each other. (P2)

Our data revealed variation in how educational leaders defined and interpreted hybrid teaching. Of our sample, only three individuals had previously taught using hybrid methods. For other participants, many early definitions of hybrid included comparisons to the more familiar concept of blended teaching. Over time, however, an increasing sense of clarity started to emerge, and staff held very similar definitions of hybrid, although there were differences in disciplinary practice. This ultimately resulted from educational leadership staff taking on the responsibility of negotiating what hybrid ought to look like in disciplinary practice.

The final responsibility of educational leadership was ensuring safety of their staff and students during the pandemic. DLTs specifically discussed their discomfort at asking their colleagues to work on campus when anxiety about contracting Covid-19 was rife. Educational leaders therefore had the added challenge of mitigating risk on campus while managing to adhere to social distancing laws and consider staff working preferences.

There was this feeling like: ‘am I going to expose myself to the sickness if I'm there?’ And yes, your risk factor is probably a little bit higher if you do go to teach … that was a big hurdle. I mean, how do we get around that? We can't force people to do it, nor would we want to. (P9)

Leadership staff had to bridge the expectations of the institution with the working practicalities of hybrid teaching for their discipline and consider the safety concerns of their staff. Participants discussed being unsure of what to do in this situation although the majority felt that ensuring safety was a priority and other activities were designed around that.

Adapting to changing circumstances

Assuming autonomy at the school/department level allowed the leadership and teaching staff to adopt different approaches and technologies based on curricular needs. Nevertheless, the diversity in technology use came with a need to overcome barriers to implementation regarding procurement, technology support, staff training and student engagement. For example, some participants regarded the University’s adopted Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) and its communication tool limited, especially when the majority of course delivery involved synchronous online sessions. As staff became more familiar with tools there was a quick shift to tools such as Microsoft Teams and Zoom. Typically, university-level adoption of such tools requires a lengthy procurement process, involving technical review, user feedback, and the preparation of training materials. However, the procurement process was not responsive to the urgency of the switch to other technologies in times of crisis, as signalled primarily by DLTs in response to managing the experiences and expectations of their staff, causing confusion and frustration among leadership staff in how to support students and colleagues.

While not having access to desired tools may have created hardship for staff, using different tools for similar purposes (e.g., Teams vs Zoom) between courses was also confusing, as raised by some DLTs who were concerned for their students.

The leadership staff agreed that their approach to the local implementation of hybrid was impacted heavily by changing infection rates and government guidelines, and how the University adjusted to these for each semester. Nevertheless, as one interviewee noted, this was a natural part of their role. Through this evolved understanding they were able to reflect and consider future teaching.

I think we got to a point, particularly in semester two planning this year, but we really had quite a good developing sense of what that was, and I think it's quite … evolved from what was in the hybrid teaching strategy document itself. (P2)

Managing pedagogical change

An aspect of the educational leaders’ roles was managing rapid pedagogical change within their organisational unit, ‘it was building a plane as we were flying it!’ (P8). This included providing opportunities for staff skill development. Some interviewees reflected on how the staff learned new technological skills and took part in professional learning about online or hybrid pedagogy to adapt their existing practices.

The interviewees spoke about how staff moved from the viewpoint that for successful online teaching they needed to simply up-skill in technology, to the viewpoint that they could take the opportunity to revaluate their teaching practices considering the affordances presented by technology:

Some … colleagues are positively impressed and want to keep a format here where they say ‘OK, this has worked a lot better because I've recorded [a] series of videos that I can actually speak with the students here on a weekly basis and directly interact with them and solve problems with them.’ (P5)

Educational leaders across the university created and disseminated a web of support for staff as they made the transition to hybrid teaching. The interviewees also spoke of how they personally made use of support networks to help them cope: ‘It's just been a huge shift in awareness and collegiality and support in terms of understanding what's going on in other schools’ (P6). In addition to support within the university, the interviewees took part in disciplinary peer networks nationally and/or internationally, which they also used to support their staff and decision-making.

Resolving contradictions

A common theme of the interviews with the educational leaders was their struggle to resolve contradictions across several issues. Communication from and with the central university was problematic for many of the interviewees. Part of the difficulty arose from uncertainty that was intrinsic to the situation: Schools had to plan arrangements for teaching before university policy documents were released because of rapidly changing circumstances. This meant DLTs had to navigate contradictions between messages from different layers of management, which many found frustrating.

I was struggling to make sense of the various agendas that seem to be pulling in different directions both within the school and college and within the senior management team as well … what was being said at college level seemed to be quite different to what was being said at university level. (P10)

There was some discontent about the messages that the central University communicated to the students and the media. According to Participant #3, the University’s description of their teaching approach as ‘hybrid’ rather than ‘online’ was a ‘marketing position’ which meant ‘all of our expertise in online learning and online courses that we have been doing for 20 years was ignored, seemingly because it had the word “online” in it … that really surprised me.’ In addition, some felt uncomfortable in that what students were told by the university did not match what was logistically possible to arrange at a local level. As expressed by Participant #5, ‘I felt as a university, we were not honest to say “Come to Edinburgh you're gonna have teaching on campus”.’

Participants struggled with contradictions from the university leadership in terms of policy and what was possible to achieve in practice. They mentioned the difficulty of implementing policies which were underspecified, such as the possibility for students to switch between online and on-campus versions of the same class and what that meant for professional services teams and teaching staff.

The interviewees were concerned with equitable access to learning for the students in their Schools. They discussed potential barriers to access for students who were unable to fully access learning online. In line with their values including ‘social justice, inclusivity, diversity, and accessibility’ (P4), they were committed to including students who were living abroad perhaps in different time zones, or who had poor internet connectivity or limited access to technology, or who had disabilities. However, there were many challenges to achieving this in practice. For example, technical issues with the VLE arose early in the Autumn 2020 term, which caused students in China difficulty when accessing learning materials, and there was an on-going issue with the policy and process for creating subtitles for videos to comply with changes to UK accessibility legislation.

Some of the interviewees made the point that the pre-pandemic model of learning on-campus was not inclusive for some student groups. They highlighted that the new ways of teaching (e.g., pre-recorded videos with captions, anonymous discussions) met the needs of these students better:

We've got one student who is deaf and is being very appreciative of the way that she's been engaged … and other neuro-divergent students who also said that that's really been beneficial. (P3)

The interviewees reflected on contradictions relating to the range of staff attitudes from resistance to success. Some noted that at various stages of the pandemic, some staff members did not appear to prioritise the upcoming need for the switch to hybrid teaching in a timely manner, while others were ‘terrified’ and required confidence building and support to design materials and student engagement activities. While many staff engaged with the professional development opportunities, some chose to experiment with different teaching approaches. Therefore, the educational leaders’ roles included ensuring that support was available for all teaching staff as appropriate to a range of different attitudes and motivations.

Reflecting and planning for the future

When reflecting on their experiences since the start of the pandemic, many leadership staff mentioned the sheer speed at which they had to react to the ever-changing circumstances and adapt their teaching. This left little time to evaluate some of the key decisions they made, particularly at the start of the pandemic when the focus of many staff was to try to transfer course material online and develop digital skills. They spoke of lessons which they had learned relating to the student experience and what could have been done differently to enhance teaching such as investment in technology infrastructure.

As part of their on-going reflection, leadership staff were also keen to reflect on pedagogical futures more broadly. The pandemic had led many to consider what the future of teaching might look like and to think about the opportunity to tackle pervasive issues in HE, such as inequality. Staff were beginning to see how elements of hybrid/online teaching had the potential to benefit HE, but also reflected on the fact that this would not happen immediately.

Staff also mentioned that the pandemic positively shifted many people’s opinions about online education, particularly among those with little to no experience of it, and many discussed the potential that hybrid/online teaching could offer to the education sector. However, leadership staff were keen to highlight that many of their colleagues and students were still grappling with pervasive cultural expectations of teaching, such as the physical institution being the only place for authentic teaching, particularly because online education in general was portrayed by the media in the UK as poor in comparison to on-campus teaching.

There's also a lot of negative press around online teaching and how it is ‘less’ than in-person teaching, which is absolutely not the case. So there's all this dialogue going on outside the University space, but also within the University space because there are colleagues who do believe that and who value the traditional model of teaching. Although I think that's slowly changing. (P13)

One final and important element of this theme was staff reflecting on how their past experiences could be used to guide the future of teaching. A key aspect that was referred to by every single participant was how the rapid digital pivot affected workloads. In general, staff knew that the crisis would inevitably result in a workload increase and demonstrated a collective effort to ensure students had a positive learning experience and weather the crisis, illustrating the duty of care leadership staff believe they hold. However, many noted that crises often highlight existing problematic issues and voiced concern over expectations of their time. ‘Most [staff] have expressed burnout stress that has come from the frequency of commitments, of meetings, and then they still have to prepare their materials.’ (P4)

Even though UoE was successful in adapting to teaching during the pandemic, the pandemic response practices are not sustainable in the view of interviewees. Leadership staff expressed the need to reconsider how elements of hybrid teaching, particularly asynchronous aspects and designing activities to promote student engagement, took up a lot of time which was often left unnoticed. Thus, the role of educational leadership changed dramatically over the course of the pandemic and staff wanted to see that reflected in future planning of their pedagogical activity in leading their teams.

Discussion

The rapid and necessary adaptation of online/hybrid pedagogies and delivery was challenging for the teaching staff who had varying levels of digital fluency and could not be offered personalised support from professional/technological services to the level they would have received in normal times. This presented a unique challenge for university leadership. Through interviews, this study aimed to understand the experiences of university staff in leadership positions as they facilitated the shift towards hybrid teaching.

The rapid digital transformation towards hybrid teaching at UoE presented many challenges for educational leaders. Our data reveal that the speed of the crisis meant the responsibilities of educational leaders changed profoundly over the pandemic and that quite often staff felt as though much of their responsibility went unrecognised. This may have contributed to and been a result of a lack of consistent and systematic communication with senior university management. Brooks and McCormack (Citation2020) note that successful digital transformation requires a coordinated workforce and operating models that transform strategic direction. Yet the juxtaposition is that digital transformation during a pandemic did not allow this to be the case. Prior research suggests academics require prior technical and pedagogical support from an institution, including elements of professional development; an indicator that staff efforts are being valued (Han et al., Citation2016). This presents a call for senior institutional staff in HE to consider the structure of leadership roles and create open lines of two-way communication enabling new operating models, strategic directions, and professional development.

Lacking the time for planning, development, and adapting to remote teaching resulted in an overwhelming increase in workload. Our interviewees spoke about staff burnout due to the strain of increased workloads during the transition to hybrid, exacerbated by the on-going stress of living through a pandemic. This echoes the findings of Huang et al.'s (Citation2021) study of academics’ experiences of switching to blended learning, which took place before the pandemic. As a result, they argue for universities to approach managing pedagogical change through an ethics of care: ‘a care-less [institutional] environment does not only impede academic capacity to innovate, but also their capacity for in-turn caring for students, as academics themselves are in need of care’ (p. 12). This caring responsibility is even more salient as universities continue to cope with the pandemic and its aftermath. Our participants demonstrated a duty of care and a willingness to rise to this challenge. The pandemic only emphasised the importance of their role during times of crisis in maintaining standards of teaching and support during the emergency response and periods of lockdown. Educational leaders also had the additional burden of supporting staff to tackle concerns outside of their control (e.g., safety) and the scholarly activity of adopting new pedagogical approaches to their teaching.

A duty of care was also reflected in the discussion about accessibility and social justice. Our data reveal that staff were equally aware of the lack of digital accessibility for some students, whilst also allowing more flexibility for international students or those with additional support needs. The vast majority considered the flexibility that hybrid teaching allowed to be a positive consequence of the digital pivot as it further cemented the values of inclusivity that participants believe HE institutions hold core to their values. For these reasons, many staff wanted to continue aspects of this flexibility even after the need for hybrid teaching might have disappeared.

Our interviewees also spoke of the need to take time to pause and reflect on their recent pedagogical changes before rushing to embrace further innovation. The changes HE institutions have implemented during the pandemic do not reflect the high-quality versions of online/hybrid teaching that research has shown to be successful (Hodges et al., Citation2020), even though our participants did engage in the scholarly process of pedagogical change as far as possible despite time constraints, and were able to reflect on the long-term benefits of this. We believe that this is an important consideration for university managers. Academic staff have adapted their pedagogical practices under the most difficult of circumstances, supported in our case study by the skills of local educational leaders. University managers should reward the educational resilience of their staff by respecting their judgement about the pace of future change, and in the development of training for future DLTs. DLTs are in a unique position in that they often hold an overarching view of university strategy and how this can/will play out among staff and students in their departments. This suggests that they can play a more active role (than previously assumed) in decision-making when liaising with Senior Management because they can represent the views of their staff and students. The findings of this study regarding those in educational leadership roles should be considered in conjunction with other studies of the experiences of teaching staff, students, and other stakeholders. For example, our study does not include Human Resource Management who often directly deal with individuals' workloads or managing staff illness or absence. This is clearly an important aspect of DLTs having to navigate the pandemic which could be considered in future. Also, it could be that some DLTs chose not to participate in our study because they were unwilling to speak negatively about their Schools in what would become a public document, however, negative views do occur within the dataset

Further systematic research is required to carefully evaluate the impact of hybrid teaching before universities invest in costly hardware to support it. In considering the characteristics to nurture the next generation of educational leaders, our findings indicate these are staff who are flexible and resilient with the capacity to deal with ambiguity and contradictions, a willingness to reflect on and balance innovation with good pedagogical practice, and to nurture these characteristics in their own staff. Finally, we suggest it is up to senior management to support the DLTs in assuming this responsibility. As Ehlers (Citation2020) notes, a transformational leadership approach that relies on communication, participation and trust is the most promising form of digital transformation in the post-Covid era, and our data appears to support this view. We therefore call on senior institutional management to nurture this change by engaging in discussion with DLTs, and those in similar leadership roles, who were at the forefront of navigating this change. DLTs hold an overarching perspective of university workings, from understanding student experience, practicalities around teaching staff and teaching strategies used, and understanding broader university aims and strategy. They should therefore be called upon for their expertise in any major transformation universities envisage in the future.

Conclusions

In order to be resilient to the challenges of the on-going pandemic, and future calamities, institutions must consider how to support the skills development of educational leadership staff and clarify their roles in crises. The themes from our data indicate that educational leaders successfully guided their staff and students by assuming responsibility, adapting to changing circumstances, managing pedagogical change, resolving contradictions, and reflecting and future planning. Institutions should invest in professional learning opportunities to grow such skills in the next generation of educational leaders, and ensure that they are explicitly made aware of the level of responsibility they have over pedagogical aspects of the emergency response within schools/disciplines and in supporting staff to tackle concerns outside their control. Regular two-way communication between senior institutional and educational leadership staff would assist local leaders to understand the boundaries of their role and to resolve apparent contradictions between high level policy and local logistics. Local educational leaders can assist senior management in universities to understand the high workload and time required to carefully design online courses, and the impact this has on staff morale and wellbeing. In sum, DLTs play an important role that can assist with supporting any major transformation in the teaching domain.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (63.7 KB)Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the Moray House School of Education and Sport. All of the authors were employed by UoE at the time of data gathering.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 A briefing from the Russell Group on Digitally Enhanced Learning can be viewed here: https://russellgroup.ac.uk/news/digitally-enhanced-learning-at-russell-group-universities/.

References

- Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2010). Class differences: Online education in the United States, 2010. Sloan Consortium (NJ1). https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ed529952

- Blackmore, J. (2020). The carelessness of entrepreneurial universities in a world risk society: A feminist reflection on the impact of Covid-19 in Australia. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(7), 1332–1336. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1825348

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Brooks, D. C., & McCormack, M. (2020). Driving digital transformation in Higher Education. ECAR Research Report. ECAR. https://library.educause.edu/-/media/files/library/2020/6/dx2020.pdf

- Cavanagh, T. B., Thompson, K., & Futch, L. (2017). Supporting institutional hybrid implementations. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2017(149), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20233

- Creswell, J. W., & Guetterman, T. C. (2021). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (6th global ed.). Pearson.

- Crick, T., Knight, C., Watermeyer, R., & Goodall, J. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 and “Emergency Remote Teaching” on the UK Computer Science Education Community. In The proceedings of UKICER 2020: United Kingdom & Ireland computing education research conference (pp. 31–37). https://doi.org/10.1145/3416465.3416472

- Crick, T., Knight, C., Watermeyer, R., & Goodall, J. (2021). An overview of the impact of COVID-19 and “Emergency Remote Teaching” on international CS Education practices. In Proceedings of the 52nd ACM Technocal Symposium on Computer Science Education (SIGCSE) (p. 1288). https://doi.org/10.1145/3408877.3439680

- Ehlers, U. D. (2020). Digital leadership in Higher Education. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Leadership Studies, 1(3), 6–14. https://doi.org/10.29252/johepal.1.3.6. http://johepal.com/article-1-66-en.html

- Fink, D. (2010). Developing and sustaining leaders of learning. In Developing successful leadership (pp. 41–59). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9106-2_4

- Graham, C., & Dziuban, C. (2008). Blended Learning Environments. In J. M. Spector, M. D. Merril, J. Merriënboer, & M. P. Driscoll (Eds.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technologies (3rd ed., pp. 269–276). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Han, X., Wang, Y., Li, B., & Cheng, J. (2016). Case study of institutional implementation of blended learning at five universities in China. In C. P. Lim & L. Wang (Eds.), Blended learning for quality higher education: Selected case studies on implementation from Asia-pacific (pp. 265–296). UNESCO Bangkok Office.

- Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review. Retrieved July 30, 2021, from: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

- Huang, J., Matthews, K. E., & Lodge, J. M. (2021). ‘The university doesn’t care about the impact it is having on us’: Academic experiences of the institutionalisation of blended learning. Higher Education Research & Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1915965

- Irvine, V. (2020). The landscape of merging modalities. Educause Review, 55. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/10/the-landscape-of-merging-modalities

- Marshall, S. J. (2018). Shaping the university for the future: Using technology to catalyse change in university learning and teaching. Springer Nature.

- Moore, J., & Fetzner, M. J. (2009). The road to retention: A closer look at institutions that achieve high course completion rates. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 3, 3–22. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v13i3.1650

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2018). NVivo (Version 12). https://www.qrsinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Raes, A., Detienne, L., Windey, I., & Dapaepe, F. (2020). A systematic literature review on synchronous hybrid learning: gaps identified. Learning Environments Research, 23(3), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-019-09303-z

- Rowley, J. (2002). Using case studies in research. Management Research News, 25(1), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409170210782990

- Saichaie, K. (2020). Blended, flipped, and hybrid learning: definitions, developments, and directions. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2020(164), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20428

- Selwyn, N. (2016). Is technology good for education? John Wiley & Sons.

- Selwyn, N. (2017). Education and technology: Key issues ad debates (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury Academics.

- Skulmowski, A., & Rey, G. U. (2020). COVID-19 as an accelerator for digitalization at a German university: Establishing hybrid campuses in times of crisis. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(3), 212–216. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.201

- Smith, K., & Hill, J. (2019). Defining the nature of blended learning through its depiction in current research. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(2), 383–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1517732

- Watermeyer, R., Crick, T., Knight, C., & Goodall, J. (2021). COVID-19 and digital disruption in UK universities: Afflictions and affordances of emergency online migration. Higher Education, 81(3), 623–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00561-y

- Zhang, X. (2020). Thoughts on large-scale long-distance web-based teaching in colleges and universities under novel coronavirus pneumonia epidemic: A case of Chengdu University. In I. Rumbal, T. Volodina, & Y. Zhang (Eds.), 4th International conference on culture, education and economic development of modern society (ICCESE 2020) (pp. 1222–1225). Atlantis Press.