ABSTRACT

This paper explores the reflections of occupational therapy academics about the experience of kindness in academic and professional life. Data were derived from a reflective group conversation in the context of a larger overarching research project exploring occupational therapy academic development. The findings elaborate how kindness and care played out for us as participant-researcher academics, including how it was mediated by expression of values and behaviours in our roles, and how we experienced the values and behaviours of others in the academy. We found that degrees of kindness and care were distributed along a continuum from more kind to less kind. A notable aspect of our conceptualisation of kindness involves recognising others' potential and a willingness to work collectively. We argue that it is critical to create and maintain communities that value and are capable of acting with authentic care and kindness. Prioritising our time to engage in emotion-based, relational work beyond ‘duty of care’ is vital to support collective success and longevity in the academy. Recognition of, and action to challenge, the forces that erode kindness and care are vital next steps in creating academic and professional contexts that will support our flourishing.

Introduction

In this paper, we proceed with the understanding that whether we like it or not, we are managed performers in our higher education and/or professional practice contexts. Our productivity is measured. Time is precious. Juggling competing demands can bring tension into our working lives, including our relationships with students, educational colleagues, and professional colleagues working in ‘the field’. While most workplaces espouse values that include collegiality, growth, and development, we have experienced a dissonance among these values and our lived experience as we struggle with the performative, even hyper-performative (Macfarlane, Citation2019), demands of the academy. Taking time to provide considered feedback to a student who has struggled with an assignment or agreeing to review a manuscript of a more junior colleague who has come to us for our expertise can seem burdensome. Far from being a concern simply for occupational therapy academics, we feel that this situation is equally relevant across professional practice contexts, the clinic classrooms in which our students apply their academic learning. Students may experience frustrations in accessing us in the academy and witness their field-based educators, for example, cut one client session short as they rush to start another. Both in the academy and in their clinic placements, our students learn early on that the profession that they hope to enter is not all about caring. They will experience the tension of trying to finish a report or calculate their client statistics to meet the neoliberal fascination with how much and at what cost. We wondered about the presence or absence of care and kindness in these types of scenarios, and the extent to which they open the door for unkindness to creep in?

Inquiry context

Our exploration of kindness and care arose as a specific sub-inquiry in the context of an overarching academic development project, Growing Scholarship (GS). The project co-led by occupational therapy academics from a single university intentionally set out with the goals of critical reflection on identity. This reflection was seen as an essential step toward doing, being, becoming, and belonging as scholars, and, as our context demanded – productive scholars. Commencing in 2013, the project utilised a framework of bimonthly reflection and action planning meetings, that were recorded and analysed, with the findings published elsewhere (Carra et al., Citation2017; Ennals et al., Citation2016; Fortune et al., Citation2016). Those findings outline the extent to which the project enabled fringe-dwelling occupational therapy educators, primarily oriented to preparing graduates for the profession, to expand and embrace a more fulsome identity as a scholarly academic.

The participants in the current inquiry were a subgroup of eight occupational therapy academics from the broader thirteen person GS community of practice (CoP), who wanted to explore the phenomenon of kindness and care. This topic, while raised in the overarching study, it was agreed, demanded its own dedicated inquiry. In various ways, our original CoP members expressed feeling cared-about throughout the process of developing their academic potential.

Doing with supportive others, rather than alone, makes what felt previously hidden and tentative, seen and concrete. Perhaps this is the greatest gift of the [GS] group: together we became scholars, writers, and researchers, we discovered that indeed we belonged ‘on the other side’.

I see the essence of our [GS] group as a place to ‘be’, a ‘family’ to belong to … . It has been a place to ‘have a go’ together and an environment where I feel accepted, and a worthy contributor.

While these narratives convey that the overarching project enabled participants to shift their practice, and in turn, their identity, our investigations also pointed to a need to further elucidate and continue to advocate for kindness that we felt was somehow absent or obscured in the university beyond our project space. Our earlier inquiry revealed that sustaining and developing one’s academic identity depends critically on perceiving that one belongs to a particular sort of place in which people can be, do, become, and belong; a place that balances kindness and respect, while also providing support to ‘do’ what is required of a performative, managed academic (Fortune et al., Citation2016).

Kindness and caring in the academy and beyond

Commentary on the presence or absence of kindness and care in our educational and caring organisations appears to be increasingly prominent across peer reviewed and other forms of academic writing. Reference to kindness, or more specifically, a lack of kindness and care, is often associated with critique of the neoliberal influences on academic and professional life (Burton, Citation2021; Clegg & Rowland, Citation2010; Lynch, Citation2010; Rowland, Citation2009; Citation2008). Ambivalent, mercurial, and ill-defined (Burton, Citation2021), kindness is often referred to interchangeably with caring. While detailed analysis of the difference between these concepts is beyond the scope of this paper, we recognise that there is a difference, and similar to other authors, we dip in and out of our usage of these intertwined concepts. According to the Macquarie Online Dictionary, the adjective – kind – refers to ‘having, showing or proceeding from benevolence’; the verbs cared and caring are defined as ‘to be troubled; to be affected emotionally … to have thought or regard’ (Macquarie Online Dictionary, 2023). The terms in the context of this paper reflect both a value ‘benevolence’ and the capacity for related caring thoughts, behaviours or actions. Kindness as ‘voluntary, intentional behaviours that benefit another and are not motivated by external factors such as reward or punishment (Eisenberg, Citation1986, p. 63) most closely aligns with our working understanding of the term.

Our interest in kindness and caring stems both from our experiences as academics and our occupational therapy background, a profession with a strong tradition in emotional work in the service of psychosocial health and wellbeing. The centrality of emotions to all aspects of academic activity, in which caring-with others is associated with ‘generosity, collegiality and the communal’ has been studied by Askins and Blazek (Citation2017), while from an individualistic perspective, kindness as a pro-social act has been associated with wellbeing (e.g., Curry et al., Citation2018; Shillington et al., Citation2023). Picking up on a discourse of kindness ‘talk’ in the academy, Burton (Citation2021) offers critique of the potentially hollow, fleeting and feel-good aspect of kindness, a thing to be a performed, a measurable action, packaged as work such as academic citizenship (Burton, Citation2021).

Caring and learning to care

Educational philosopher, Nell Nodding’s, writings on moral education and the ethics of care are instructive in considering what care is and why it is important. The purpose of moral education in Noddings’ (Citation1992) view is to develop skills and attitudes that can sustain caring relationships throughout life. The caring relation is seen when

one person, A, cares for another, B, and B recognises that A cares for B. A’s consciousness during the interval of caring is marked by (1) engrossment or non-selective attention and (2) motivational displacement or the desire to help. A genuinely listens feels and responds with honest concern for Bs expressed interests or needs. A’s relation of caring is complete when B’s recognition becomes part of what A receives in his or her attentiveness. A relation may fall short of caring if either carer or cared-for fails in his or her contribution. (Noddings, Citation1992, p. 91)

Challenges to caring in the neoliberal academy

Recent changes occurring globally in higher education have impacted academics from most disciplines, including occupational therapy academics. In Australia and elsewhere, an increased number of universities offering occupational therapy programs and increasing student enrolments in existing programs has intensified workforce shortages. Practitioners with a desire and interest in teaching are transitioned into academic life, often without a higher research degree, or significant experience of managing subjects and large cohorts of students (Gustafsson et al., Citation2021). Practitioners often come to teaching sharing Noddings’ (Citation1992) belief that teaching for and through care is a moral imperative.

The need for care in our present culture is acute. Patients feel uncared for in our medical system, clients feel uncared for in our welfare system, students feel uncared for in our schools. Not only is the need for caregiving great and rapidly growing but the need for that special relation, caring, is felt most acutely. (Noddings, Citation1992, p, xi)

Transitioning these professionals to teach such courses is challenging for these new academics and the acculturation of this workforce into academia can place additional demands on tenured or contracted colleagues who may also be completing doctorates and struggling to establish their academic career. A growing casual academic workforce (Crawford & Germov, Citation2015) and increased academic workload (Chan, Citation2018) place pressure on meeting the expectations of life in what has been referred to as the ‘measured university’ (Peseta et al., Citation2017; Sutton, Citation2017). The experience of being measured, a hallmark of the neoliberal university, can be seen to throw us into doubt as to our purpose and worth.

Every day, our conduct is being shaped to procure a commitment to institutional indicators, targets, standards and benchmarks that help us to diagnose ourselves (and others) as worthy and successful academics. At the same time, universities repurpose our labour to shore up their market distinctiveness in ways that are likely to surprise, shock and repulse us. (Peseta et al., Citation2017, p. 454)

Neoliberalism has been described as a theory of political and economic practices based on the view that ‘human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterised by strong private property rights, free markets and free trade’ (Harvey, Citation2005, p. 2). Neoliberalism enacts forms of power and control that have been noted to ‘diminish scholarship, education, students, and academic staff’ (Morley, Citation2023, n.p.). Expressed organisationally in managerial practices related to monitoring and performance appraisal (Lynch & Grummell, Citation2018), academic departments become focused on budgets, while individual academics and professional staff alike are subjected to a range of performance audits and often rewarded, or sanctioned, on the basis of their productivity. Demonstrating measurable performance gains and the receipt of rewards has been noted to engender competition and constrain collegiality (Lynch et al., Citation2020). In the absence of a metric for good will and collegiality, Lynch et al. (Citation2020) observed ‘people are encouraged to be calculating and self-focused’ (p. 161).

O’Shea and McGrath (Citation2019, p. 5) reported a ‘sense of professional disempowerment’ among British occupational therapy academics subjected to performativity measures. Drawing on Kinsella and Whiteford’s (Citation2009) critique, these authors also suggest that the reductionist and standardised approach to health service provision, a hallmark of evidence-based practice, can diminish occupational therapists’ focus on subjective human experience. Occupational therapists’ habitus in which their propensity to act with care and kindness is likely diminished by their disempowering context. Looking beyond the academy and occupational therapy practice to our communities more broadly, a report from the United Kingdom’s Carnegie Foundation (Ferguson, Citation2017) examined the challenges of building strong communities and overcoming loneliness and reducing barriers that inhibit kindness. The Carnegie Report also highlighted that where risk management is the priority, kindness is often unintentionally sacrificed. When utilising risk management strategies, bureaucracies such as universities, health, and social care organisations must be mindful of the potential to isolate academics and reduce their perceptions of, and ability to act with, kindness and care. Biggar et al. (Citation2022) proposed that kindness and practitioner regulation are not incompatible. Rather than kindness being diminished when scrutiny is required, they suggest ‘assessing each complaint individually by risk, being quicker and more transparent and ensuring respect for both parties’ (p. 2).

In the context of tightly managed departments, focused on indicators, targets and benchmarks, we might be excused for questioning the place of kindness, care, or even love (Rowland, Citation2008; Sutton, Citation2017) for our vocation, our colleagues, our students and ourselves. Sutton (Citation2016; Citation2017) prompts us to consider the vital presence of love and ‘soul’ in the academy.

… performativity neither measures nor values what is central to academic labour: love (Sutton, Citation2016). Love … is a vital dimension of the deep, rich social relations that are necessary for the emergence of soul in academic labour. Furthermore, love is also a vital dimension of a humane moral economy. (Sutton, Citation2017, p. 626)

Research methodology and methods

Methodology

Our exploration of care and kindness adopted a constructivist-interpretative orientation to knowing, in which we utilised collaborative reflection and sensemaking to understand our subjective perceptions and experience of kindness and/or its absence in academic life.

Methodologically our approach is aligned with critical reflexivity, which aims to generate shared knowledge and understand through collaborative reflection. Taylor (Citation2010) described a three-tiered conceptualisation of reflection, incorporating technical reflection, practical reflection and emancipatory reflection. Our work moves beyond technical reflection, which is centred on rational, empirical evidence (Coburn & Gormally, Citation2017), but did not extend to emancipatory reflection, the ‘radical critique of the unexamined assumptions about social, economic, historical and cultural influences’ (p. 89) needed for transformative action. We have operated at the level of practical reflection to explore our subjective experience at a naming and framing, awareness raising level. The intent of our approach was interpersonal, focusing on a collective elucidation of our lived experience and cues for personal actions to strengthen kindness. While we may have also noted them, we have not, in this work, critiqued the power structures and systems influencing our subjectivities. The reflective groundwork we undertook does incorporate a line of sight toward the critical reflexivity needed for the (future) transformative action required to influence power structures producing the felt aspects of our experience.

Data collection

Data for this paper were generated through a 150-min reflective conversation between eight occupational therapy academics (including the authors), all white females, most in continuing full-time academic roles in a mid-tier, Australian university. Our conversation was digitally recorded and transcribed. As one of our regular bi-monthly meetings in our (Ennals et al., Citation2016; Fortune et al., Citation2016) community of practice, this particular meeting was set aside to collectively explore our personal experience of kindness and care. In preparation for the meeting, we read Rowland’s (Citation2009) viewpoint on kindness, to sensitise us in our exploration of this idea. As part of our reflection conversation, on the what, why, and how of kindness, the first and second authors invited our group of eight participants to talk about what kindness in the university is or is not. This prompted participants to consider and share what acts of kindness they had seen or experienced, and why they felt these experiences were ‘kind’ or not. The free-flowing discussion generated descriptive personal experiences, triggering intersubjective understandings.

Data analysis

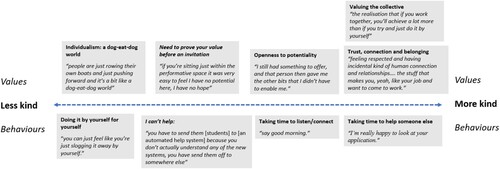

Following an inductive approach, the first and second authors undertook an initial analysis of the transcript, in which they assigned conceptual codes at a word or sentence level (Liamputtong, Citation2013). Over the course of several meetings, five of the eight focus group participants (the eventual authors) considered and collaboratively agreed or rejected the interim codes. Conceptually relevant codes were organised into one of two categories – within an organising theme of a continuum of kindness. provides an illustration of how text (italicised) was coded (un-italicised) and then categorised.

Findings and reflections

Analysis of our conversation transcript revealed a continuum of kindness. This continuum was evidenced through two categories – values and behaviours – we noted that each of these could be more or less kind, and even unkind or uncaring at the extreme. Values included (but were not limited to) the professional values of occupational therapy and mindsets such as care, generosity and connection; valuing others' potential, valuing the collective, and valuing process alongside outcome. These values were both expressed by us, and the values of others felt by us. They influenced the behaviours evident in the findings. Behaviours related to working at speed, working individually or collaboratively, and degrees of competitive striving.

Everyday experiences on the continuum of kindness and care

As a group we floundered to clearly articulate what kindness looked like. There were long pauses, mouths opened to speak and then shut again. Initially it was as if there was no language to describe this quality. We talked about ‘kind moments in teaching’ – between teachers and students. This sort of kindness, enacted with others, seemed more readily recognisable. Drawing from Rowland’s (Citation2009) work, we shared descriptions of kind interactive moments that we had had with students. A kind email for example, was one that was carefully worded, sometimes lengthy, conveying to the student that we had heard and understood their issue. These kindly emails were contrasted with rather curt 10-word emails re-directing the student to a centralised and faceless system.

Time featured as a resource that underpinned kindness; taking time, offering time, and acknowledging time pressures that were outside of one’s control. One person recounted an experience of being surprised when approached out of the blue about their failure to be granted study leave. Using the words of the panel member:

‘[name] I was part of the panel for your OSP (Outside Study Program) and I’m really sorry. I know that it got declined. I’d really like to sit down and talk to you more about how you could change this, and I’m really happy to look at your application.’ And I mean she didn’t know me from a bar of soap. I just saw it as real act of kindness.

One participant talked about how caring happens in the corridors, when we loitered long enough to hear about colleagues’ ‘dogs n kids’; taking time and interest to go beyond required academic topics.

I think you can be kind by spending a couple more minutes to say good morning, or to make a little comment, or to acknowledge something, but it does take that little bit of extra time that sometimes you lose sight of.

As the conversation of student-focused kindness slowed, again we struggled to describe what kindness looked like between colleagues. The conversation gained momentum when the question was rephrased to ask, ‘what is kindness not’? Significantly easier to describe, our experiences of unkindness revolved around ‘being excluded, not being heard and feeling unworthy’ (as an academic and a potential member of a research team). One participant started a conversational thread about ‘bars, barriers and boundaries’ with the notion that bars could represent unkindness, ‘when you say to me what’s not kind, my response is, well, when I have a bar that I expect people to jump before I will respond to them, or value or recognise them’.

We agreed that bars could be unkind but more specifically that what was unkind was a bar that had no accompanying instructions on how to traverse it. The provision of clear and explicit expectations in relation to how we might have our hard work recognised in the academy (e.g., through promotion or the receipt of a teaching award), was perceived as a form of kindness in which staff were ‘cared about’ enough to be given the sort of information that would help them get ahead.

Our discussions on the environmental barriers and enablers to kindness led us toward reflecting on how academic spaces could feel kind or unkind. Physical barriers to kindness and caring were reflected in a department where academics spent time in single-person offices with their doors mostly closed. To have an open door invites distraction, and the possibility of caring dialogues. One person shared the tension between kindness and expedience that was experienced when their door was open: ‘when someone fronts up at my door, a student. … I kind of go into horror. [I think] Don’t interrupt me. Or I haven’t scheduled this. Who are you? Openly displaying our availability came at a cost to getting things done. A closed door was akin to making ourselves care-free, all the better to get on with those things upon which we are measured. This participant recounted how shut doors were noticed.

someone in our school was told they had to keep their door open because the impression they were giving to other staff was that they were [not available] … . and they had a leadership role. … [this conveyed] I’m just going to get on with what I’m doing. … they actually had to be instructed to keep their door open.

We shut the door to save time taken up with kindly conversation. We abruptly finish sentences or send emails that convey unkindliness, most probably because of our temporal anxieties – of being engulfed, of never catching up or wanting to get home to care for others on time. One participant felt that occupational therapy academics from a ‘caring profession’ should have a disciplinary advantage to being kind when compared to other non-health academic colleagues in a care-less, ‘dog eat dog’ higher education climate.

I don’t know whether it’s something to do with our discipline background, but blimey there’s a lot of disciplines out there that are a one-man-band and people are just rowing their own boats and just pushing forward and it’s a bit like a dog-eat-dog world.

Participants talked about their perceptions that some apparent acts of kindness were actually agenda-driven un-kindness. A darker side of kindness was felt to be at play when others, often more senior people, gave us time, for which we were mostly thankful. We perhaps think ‘how kind’, but the possibility of a hidden agenda was real. One participant believed that ‘acts of kindness can be misconstrued, because people think “what are they after” or “what’s the hidden agenda here”’. Kindness could be performed, but its inauthentic nature was readily noted.

In contrast to the idea of agenda-driven un-kindness, participants talked about expressions or acts that were felt to be genuinely without agenda, characterised by mindsets of intentionality and generosity. Kindness was equated with recognition, or more accurately, in whether we felt recognised and validated in our roles. Kind people ‘recognise our potential, our strengths not only our weaknesses’. The idea of caring relationships was raised with the example given of a mother helping a child up the stairs. As one participant said, ‘It’s actually helping them get up the stairs and recognising each and every step they take’. Kindness as recognition conveyed a sense of concern for the individual over the institution. A kind colleague asks where and what you want to achieve or where you want to go and follows up with the offer to accompany and help you get there along the lines of ‘Hey, I will help you get to there. I will help you navigate what that is’.

We discussed and debated whether and how teamwork was implicated in or reflective of a caring environment. Several participants believed that an unkind working environment was one that is not team oriented and has no social safety net to help others who might be struggling. Our discussion relating to teamwork evoked the sense of a family pulling together, for each other. In this sense, certain experiences of teamwork could be seen as kindness, as one member of our group stated ‘Well, I suppose if you work in a team then if one person is struggling the other person picks up, but also it’s a sense of support … a bit like one-off acts of kindness’.

Another participant described the importance of trust and team support:

I think you also need to have an environment of trust. And so that comes back to that teamwork thing … having people peer review the draft of an article you’ve written and giving honest feedback, that can be an act of kindness if it’s done in a supportive way.

Discussion

Our reflective conversations and the analysis of them occurred at a time when none of us were as attuned to the potentially ‘wounding’ effects of the neoliberal academy (Fortune et al., Citation2023) amplified during and as a consequence of university responses associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. While a number of us were aware of the broader forces at play, our conversation did not critically explore the structures creating and perpetuating the less positive aspects of what we saw and felt. Neither did our explorations focus explicitly on how we might work toward addressing the situation. Un-accustomed to challenging broader forces bearing on progress, our findings perhaps convey, by omission, a sense of powerlessness.

During our conversation, we shared experiences of kindness and care as a quality or actions that reflected in some way recognition of, concern and respect for others in the academy – colleagues and students, all key aspects of our emerging conceptualisation of kindness. Collaborative discussion of our experiences enabled glimpses toward unkind and disempowering structures, described as bars and barriers – to advancement, to feeling worthy and validated by often faceless colleagues who had the power to notice us (or not) and make decisions about us (if they noticed us). We reflected upon kindness and care in seemingly ‘pedestrian’ ways, as have others who write of the ‘minor actions of a smile, a shared joke … office doors left open, signalling a willingness of interruption, conversation and invitation’ (Burton, Citation2021, p. 20).

Occupational therapists, in practice and in the academy, are primarily women. It is difficult to write about kindness and care without acknowledging the temporality of women’s working lives and the care burden imposed by gender (Lynch et al., Citation2020). Time spent in care activities which are embodied, relational and attributed to feminine characteristics, contrast with engagement in rational thought and productivity, the purview of masculine expression (Ivancheva et al., Citation2019; Lynch et al., Citation2020). Such values are preeminent in our institutions where the cultural requirements of female-as-carer is pitted against the institution’s performative demands (Gaudet et al., Citation2022). The competition between academic performance and care is magnified by scarceness of time contributing to what Ivancheva et al. (Citation2019) refer to as ‘care-led affective precarity’ (p. 452) in which our ‘capacity to develop relationships of love, care and solidarity’ (p. 452) are diminished.

Our findings indicate a strong temporal quality to kindness. Caring acts such as teaching, attending professional development activities, or collaborating with others for the collective good consume time. Time spent in these less scholarly, more feminine activities only serves to constrain the production of scholarly products upon which academic identity is measured and dependent. It can be difficult for care and its expression to coexist in an environment focused only on scholarly production, so rather than being experienced as relational acts of care for the student’s development or acts of self-care (Gaudet et al., Citation2022) and kindness toward our colleagues, these can be repackaged as a burden or unproductive use of time. Moreover, such tensions can negatively impact health, wellbeing, love for and longevity in our vocation (Barcan, Citation2018, Citation2019). Kind people, it was felt, took time and gave time, their most precious commodity, to care for others. Lynch (Citation2010) talked about a care-less academic culture – in which care-free academics eschew relationality for rationality. One must be care-free to go about the work of being a productive writer, researcher and self-promoting expert. To care is to relate and it is the very act of caring that gets in the way of the serious business of staying in the game as a productive academic.

Over the course of their studies, students develop a professional caring ethic through explicit teaching (Clouder, Citation2005) and reflection on clinical encounters during placements. For students to provide compassionate care they must experience this themselves (Adamson & Dewar, Citation2015), a key proposition put forward by Noddings (Citation1992). According to Battaglia (Citation2019), a professor who cares is critical, while a failure to show care can lead to questioning of the role of caring in the profession. If a collaborative, kind and respectful space supports identity development for academics (Fortune et al., Citation2016) a relational environment that supports student development through a kind and caring approach is most likely to promote caring and use-of-self when that student becomes a practitioner. As educators, it is incumbent upon us to prepare occupational therapy graduates who are ‘emotionally competent and able to engage in the use of self’ (Battaglia, Citation2019, p. 17). If kindness and caring are as intimately related to time as our findings suggest, efforts to create a more caring teaching/practice environment begin to appear futile unless broader systemic issues such as academic and professional workload are addressed.

Recognising the potential of (collective) others emerges as the key feature of our conceptualisation of kindness and care. The values consistent with this conceptualisation include: valuing and seeing the collective as contributing to productivity, an openness to potentiality for people with unproven track records, and privileging process alongside goal attainment. Values were enacted through behaviours relating to generosity, inclusion and willingness to transgress the status quo, for example, through gathering together to undertake altruistic, collaborative work. Resisting the individual competitive urge to perform, to fix silently in the background, will be challenging but necessary if we are to counter values more consistent with unkindness including productivity at speed, individualism, a requirement to constantly prove one’s worth and account for one’s time, and a valuing of completed product or outcomes. Recognising collective potential provides an alternative pathway to building academic identity, perhaps also to surviving in the academy, but requires resistance to individualism and competition, helping each other, creating time and space for incidental conversation alongside more deliberate action.

If a ‘caring’ culture is counter to the established academic culture, a clear challenge is presented to (re) emphasise relationship-focused approaches in academia. Recent studies in the practice context suggest renewed emphasis on engagement with clients. Such approaches seek to understand and value lived experience, often utilising intentional listening and what has been described as ‘emotional work’ (D’Cruz et al., Citation2020). A considered shift toward a relationship-focused approach in teaching and practice was recently reflected in developments by the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (Egan & Restall, Citation2022). Similarly, there is evidence that researchers in higher education are embracing relational approaches in teaching, where the centrality of relationship-rich experiences are increasingly recognised as being critical to student learning and success (Felten & Lambert, Citation2020). In returning to the idea of morals introduced earlier, we are also enlivened by Macfarlane’s idea of soulful academic labour, premised upon ‘a moral obligation to students and colleagues, regardless of the direct or indirect career benefits’ (Macfarlane, Citation2005, p. 172). To care beyond duty. While we relate to cautions from authors including Burton (Citation2021) about ‘kindness talk’ in the academy obscuring neoliberal power and shifting responsibility to individual academics we do not see it as a zero-sum game. As highlighted by Harré et al. (Citation2017), we need both kindness and more radical resistance to the neoliberal ethic to resist the finite games of the university where survival relies on being ‘selected to play and if you lose, you are knocked out or have to play the round again’ (p. 5). The infinite game proposed by Harré et al. (Citation2017) depends on us embracing a world ‘in which our heartfelt, personal response to life, our deep listening to others (especially those who don’t fit in), and our careful observations and thought about the social, natural and physical world come together to create and recreate our institutions' (p. 7). Infinite games embrace an ethic of care and relationality (Black & Dwyer, Citation2021) through which academics are seen to refuse to ‘surrender the notion that they can change their everyday words’ (Bottrell & Keating, Citation2019, p. 158).

Limitations

Data were sourced from a single, though lengthy conversation held between eight co-researcher-participants, all white females from a single Australian university. Derived from a study of modest scope, supported by findings generated from a sample of eight occupational therapy academics, data cannot be readily translated to the broader academic community. While part of an ongoing project, the broader data set was not included in analysis. Our participants were provided with a short viewpoint reading (Rowland, Citation2009) on the subject of kindness prior to the meeting. While data arising from our conversation were analysed inductively (without reference to this reading), there is the possibility that aspects of the discussion were influenced by this reading. The findings therefore represent a snapshot-in time-discussion (a time notably before the shifts that accompanied the COVID-19 pandemic) among a small number of participants that aimed to draw out individually relevant concepts, rather than a comprehensive analysis of kindness in the academy. We did not engage in a more critically reflexive discussion that may have allowed us to go beyond description of experiences of kindness at a values and behavioural level, towards identifying or addressing the structural forces at play. This positioning, while illuminating more agentic behaviours we could engage in with each other, is naive to many structural influences and therefore to the mechanisms required to make genuine change in the academy.

Conclusion

Academics within and beyond health science disciplines occupy places that are rational, instrumental, and relational. Recognition that the instrumentality of our working lives may be taking a toll on our relations of caring (with students and/or colleagues) is step one in reclaiming a kind and caring work life. While we are still learning, this inquiry has raised awareness in each of us regarding the conditions required for growth and longevity in our vocation. The findings of this small-scale study add to a growing body of international literature on the experiences of academics attempting to sustain themselves and others through kindness, caring and relationship-rich ways of being in an increasingly challenging higher education context. Some of the behaviours, underpinned by values we have identified include extending and receiving invitations, experiencing and conveying recognition and respect. finding, making, and taking time to help each other – up the ladder, over the bar, and playing the game as a team. Others are encouraged to embark on their own care and kindness journey, while acknowledging that more critically reflexive consideration of and resistance to neoliberalist forces is needed for genuine flourishing in the academy and beyond.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was obtained from La Trobe University Low Risk Ethics Committee (FHEC13/219) on 19/11/2014.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adamson, E., & Dewar, B. (2015). Compassionate care: Student nurses’ learning through reflection and the use of story. Nurse Education in Practice, 15(3), 155–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2014.08.002

- Askins, K, & Blazek, M. (2017). Feeling our way: Academia, emotions and a politics of care. Social and Cultural Geography, 18(8), 1086–1105.

- Barcan, R. (2018). Paying dearly for privilege: Conceptions, experiences and temporalities of vocation in academic life. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 26(1), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2017.1358207

- Barcan, R. (2019). Weighing up futures: Experiences of giving up an academic career. In C. Manathunga, & D. Bottrell (Eds.), Resisting neoliberalism in higher education Vol II: Prising open the cracks (pp. 43–64). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Battaglia, J. (2019). Concepts of caring: Uncovering early concepts of care in practice for first year occupational therapy students. Journal of Occupational Therapy Education, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.26681/jote.2019.030102

- Biggar, S., Fletcher, M., Van Der Gaag, A., & Austin, Z. (2022). Finding space for kindness: Public protection and health professional regulation. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 34(3), 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzac057

- Black, A., & Dwyer, R. (2021). Reimagining the academy: Shifting towards kindness, connection and an ethic of care. Palgrave Macmillan eBook. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75859-2

- Bottrell, D., & Keating, M. (2019). Academic wellbeing under rampant managerialism: From neoliberal to critical resilience. In D. Bottrell, & C. Manathunga (Eds.), Resisting neoliberalism in higher education Volume I (pp. 157–178). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95942-9_8

- Burton, S. (2021). Solidarity, now! care, collegiality, and comprehending the power relations of ‘academic kindness’ in the Neoliberal Academy. Performance Paradigm, 16, 20–39.

- Carra, K., Fortune, T., Ennals, P. J., D’Cruz, K., & Kohn, H. (2017). Supporting scholarly identity and practice: Narratives of occupational therapy academics. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 80(8), 502–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022617700653

- Chan, S. (2018). A review of twenty-first century higher education. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 42(3), 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2016.1261094

- Clegg, S., & Rowland, S. (2010). Kindness in pedagogical practice and academic life. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 31(6), 719–735. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2010.515102

- Clouder, L. (2005). Caring as a ‘threshold concept’: Transforming students in higher education into health(care) professionals. Teaching in Higher Education, 10(4), 505–517. DOI: 10.1080/13562510500239141

- Coburn, S., & Gormally, S. (2017). Communities for social change: Practicing equality and social justice in youth and community work. Counterpoints, 483, 111–112. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45177774

- Crawford, T., & Germov, J. (2015). Using workforce strategy to address academic casualisation: A University of Newcastle case study. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 37(5), 534–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2015.1079394

- Curry, O., Rowland, L., Van Lissa, C., Zlotowitzd, S., McAlaney, J., & Whitehouse, H. (2018). Happy to help? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of performing acts of kindness on the well-being of the actor. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 320–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2018.02.014

- D’Cruz, K., Douglas, J., & Serry, T. (2020). Sharing stories of lived experience: A qualitative analysis of the intersection of experiences between storytellers with acquired brain injury and storytelling facilitators. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 83(9), 576–584. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022619898085

- Egan, M., & Restall, G. (Eds.). (2022). Promoting occupational participation: Collaborative relationship-focused occupational therapy. Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists.

- Eisenberg, N. (1986). Altruistic emotion, cognition and behaviour. Erlbaum.

- Ennals, P., Fortune, T., Williams, A. E., & D'Cruz, K. (2016). Shifting occupational identity: Doing, being, becoming and belonging in the academy. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(3), 433–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1107884

- Felten, P., & Lambert, L. (2020). Relationship-rich education: How human connections drive college success. John Hopkins University Press.

- Ferguson, Z. (2017). The place of kindness: Combating loneliness and building stronger communities. UK Carnegie Foundation. https://apo.org.au/node/118476

- Fortune, T., Ennals, E., Bhopti, A., Neilson, C., Darzins, S., & Bruce, C. (2016). Bridging identity ‘chasms’: Occupational therapy academics’ reflections on the journey toward scholarship. Teaching in Higher Education, 21(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2016.1141289

- Fortune, T., Fyffe, J., & Barradell, S. (2023). Reimagining the university of our dreams: Heterotopic havens for wounded academics. Higher Education Research & Development. DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2023.2228213

- Gaudet, S., Marchand, I., Bujaki, M., & Bourgeault, I. L. (2022). Women and gender equity in academia through the conceptual lens of care. Journal of Gender Studies, 31(1), 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2021.1944848

- Gustafsson, L., Brown, T., Poulsen, A., & McKinstry, C. (2021). Australian occupational therapy academic workforce: An examination of retention, work engagement and role overload issues. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2021.1958002

- Harré, N., Grant, B., Locke, K., & Sturm, S. (2017). The university as an infinite game: Revitalising activism in the academy. Australian Universities Review, 59(2), 5–13.

- Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford University Press.

- Ivancheva, M., Lynch, K., & Keating, K. (2019). Precarity, gender and care in the neoliberal academy. Gender Work & Organisation, 26(4), 448–462. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12350

- Kinsella, E. A., & Whiteford, G. E. (2009). Knowledge generation and utilisation in occupational therapy: Towards epistemic reflexivity. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 56(4), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2007.00726.x

- Liamputtong, P. (2013). Qualitative research methods. Oxford University Press.

- Lynch, K. (2010). Carelessness: A hidden doxa of higher education. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 9(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022209350104

- Lynch, K., & Grummell, B. (2018). New managerialism as the organisational form of Neoliberalism. In F. Sowa, R. Staples, & S. Zapfel (Eds.), The transformation of work in welfare state organizations: New public management and the institutional diffusion of ideas (pp. 201–222). Routledge.

- Lynch, K., Ivancheva, M., O’Flynn, M., Keating, K., & O’Connor, K. (2020). The care ceiling in higher education. Irish Educational Studies, 39(2), 157–174. DOI: 10.1080/03323315.2020.1734044

- Macfarlane, B. (2005). Placing service in academic life. In R. Barnett (Ed.), Reshaping the university. New relationships between research, scholarship and teaching (pp. 165–177). Oxford University Press.

- Macfarlane, B. (2019). The neoliberal academic: Illustrating shifting academic norms in an age of hyper-performativity. Educational Philosophy and Theory. DOI: 10.1080/00131857.2019.1684262

- Morley, C. (2023). The systemic neoliberal colonisation of higher education: A critical analysis of the obliteration of academic practice. The Australian Educational Researcher. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-023-00613-z

- Noddings, N. (1992). The challenge to care in schools: An alternative approach to education. Teachers College Press.

- O’Shea, J., & McGrath, S. (2019). Contemporary factors shaping the professional identity of occupational therapy lecturers. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 82(3), 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022618796777

- Peseta, T., Barrie, S., & McLean, J. (2017). Academic life in the measured university: Pleasures, paradoxes and politics. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(3), 453–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1293909

- Rowland, S. (2008). Collegiality and intellectual love. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 29(3), 353–360. DOI: 10.1080/01425690801966493

- Rowland, S. (2009). Kindness. London Review of Education, 7(3), 207–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/14748460903290272

- Shillington, K., Morrow, D., Meadows, K., et al. (2023). Leveraging kindness in Canadian post-secondary education: A conceptual paper. College Teaching, 1–8. DOI: 10.1080/87567555.2023.2181307

- Sutton, P. (2016). A labour of love? Curiosity, alienation and the constitution of academic character. In J. Smith, J. Rattray, T. Peseta, & D. Loads (Eds.), Identity work in the contemporary university. Exploring an uneasy profession (pp. 33–44). Sense.

- Sutton, P. (2017). Lost souls? The demoralization of academic labour in the measured university. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(3), 625–636. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1289365

- Taylor, B. (2010). Reflective practice for healthcare professionals. Open University Press.