ABSTRACT

Large Language Models have already begun to affect the higher education landscape. However, there is currently a lack of work investigating how these models interface – and possibly interfere – with literacy development. Considering literacy is critical because student learning is only made possible through language. This paper considers implications for university students’ literacy development by drawing on Lea and Street’s academic literacies framework. I argue that LLMs pose different levels of risk for students’ development of each aspect of literacy contained within the framework: study skills are least at risk, academic socialisation is most at risk, and academic literacies represent an intermediate risk. Implications for instructors include dedicated instructional time and support for students to engage with reading and writing practices without LLM support before they begin to incorporate them into their literacies repertoire. If students rely too heavily on LLMs initially, there is a danger they will not undergo the enculturation and cognitive development necessary for success at university.

Large language models in the higher education context

Late in November 2022, an artificial intelligence research company, OpenAI, released ChatGPT (OpenAI, Citation2022). What followed has been described as a ‘Cambrian explosion’, a rapid flourishing of innovative uses (Teubner et al., Citation2023). But ChatGPT is not unique (cf. Anthropic’s Claude, Citation2023; Google’s Bard [Pichai, Citation2023]; and Microsoft’s Bing Chat, Citationn.d.); it is just one of many Large Language Models (LLMs). LLMs are deep learning algorithms that produce human-like text (Floridi & Chiriatti, Citation2020; Kasneci et al., Citation2023). Successive advances in their architecture and training (e.g., Devlin et al., Citation2018; Ouyang et al., Citation2022; Tay et al., Citation2023; Vaswani et al., Citation2017) and the introduction of easy-to-use chat interfaces (e.g., Meyer et al., Citation2023; Teubner et al., Citation2023) mean that LLMs excel at creating contextually appropriate (although not always accurate) responses to user prompts.

The higher education sector has not been immune to these developments. Writing about the impact of generative artificial intelligence on teaching and research is already burgeoning in journal articles (e.g., Kasneci et al., Citation2023; Lodge, Thompson, et al., Citation2023; Lodge, Yang, et al., Citation2023; Meyer et al., Citation2023), media articles (e.g., Carroll & Carey, Citation2023; Shearing & McCallum, Citation2023), university blog posts (Bridgeman et al., Citation2023; Kirk, Citation2023), and social media (Bloomberg News, Citation2023; OkSquash1234, Citation2023). There is a real sense of urgency present in this discourse, and rightfully so – academics owe it to themselves and their students to understand how new technologies impact on their disciplinary practices. The danger, however, is jumping to an extreme solution: completely banning LLMs and making all reading and writing pen-and-paper based or completely adopting LLMs and allowing any and every usage students can conceive. In this paper, I am attempting to plot a reasonable middle ground through the lens of academic literacies (Lea & Street, Citation1998, Citation2006), a theoretical framework for conceptualising how students engage with reading and writing at university. My focus on literacy is motivated by the centrality of language to learning and teaching:

Learning in higher education involves adapting to new ways of knowing: new ways of understanding, interpreting and organising knowledge. Academic literacy practices—reading and writing within disciplines—constitute central processes through which students learn new subjects and develop their knowledge about new areas of study. (Lea & Street, Citation1998, p. 158)

[The essay] may proceed by experimentation but it isn’t a scientific treatise and offers no proof; it deals with concepts and ideas … it may contain facts, but it’s certainly not always to be trusted. The essay invites readers down its many and winding paths but isn’t so interested in providing a map; it begins a dialogue but doesn’t manage the stage … The essay wonders and it doubts, it rejects conclusions, prefers the ‘not’ or the ‘not yet’. (p. 1)

Large language models are placed to interface, and possibly interfere, with the key practices of a university – reading and writing. There is a lot at stake when a student outsources some of the key cognitive processes involved in comprehending, summarising, and transforming course readings, as I shall argue below. The rapid development of LLMs means even linguists cannot reliably distinguish between human and AI-generated writing (Casal & Kessler, Citation2023), and detection software tends to be biased or incorrect (or both) (Liang et al., Citation2023; OpenAI, Citationn.d.). Put simply, as LLMs continue to improve, it will become increasingly difficult (and futile) to attempt to detect AI-generated writing.

This does not mean that reading and writing are dead. There is certainly potential for gain when a student complements their reading and writing practices with LLMs. If writing is indeed a social practice (Freebody & Luke, Citation1990; Lea & Street, Citation1998, Citation2006), then having an endlessly patient and continuously available partner to help brainstorm, draft, edit, and proofread work may be a boon – even if that ‘partner’ is an artificial one like ChatGPT. Lodge, Yang, et al. (Citation2023) have already developed a possible typology of human–generative AI interaction, but their work is focused more on categorising different uses, rather than exploring the impact of generative AI on literacy development.

The academic literacies framework: overview and applications

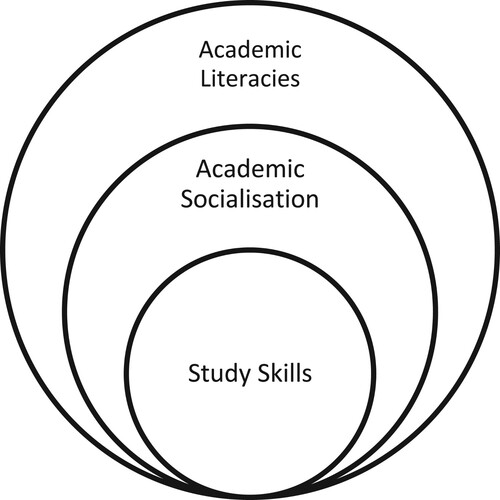

The academic literacies framework, proposed by Lea and Street (Citation1998, Citation2006), provides a powerful theoretical and practical basis for understanding how university students engage with disciplinary language. At the base of the framework is the study skills approach, which problematically reduces language to surface concerns like spelling and grammar. Things like spelling and grammar are important for effective writing, but they are not enough to become a skilled writer at university (Lea & Street, Citation1998, Citation2006; Wingate, Citation2006). Consequently, the authors add a level above, academic socialisation, which includes and expands the study skills approach. Academic socialisation involves inculcating students into the general practices of the university, especially those relating to valued ways of reading and writing (e.g., integrating evidence, paraphrasing, developing arguments, etc.). The final level of the framework, academic literacies, deals with the disciplinary nature of language use and power within the university; Lea and Street (Citation1998) provide the example of a student whose history essays are praised for their structure and argument while their anthropology essays, written in the same style, have no structure and no argument. The academic literacies approach explains this discrepancy by making the nature of ‘structure’ and ‘argument’ visible and explicit to disciplinary practitioners (as it is typically tacitly developed after years of writing). The relationship between these three aspects of literacy is visualised in .

Figure 1. The academic literacies framework (Lea & Street, Citation1998, Citation2006). Academic literacies subsumes and expands the aspects of literacy of academic socialisation and study skills.

Theoretically, then, the framework provides a nuanced way to engage with various views of literacy; however, its applications are not purely theoretical. The academic literacies approach has been successfully deployed in a variety of teaching contexts to help scaffold students’ literacy development (although cf. Goldingay et al., Citation2016; Wingate, Citation2012, for examples of staff and student resistance to the approach). I do not claim (nor would Lea & Street) that the academic literacies framework is the only, best, or perfect model for understanding literacy practices at university; instead, I claim that it is a well-established approach in many universities and, as a result a useful theoretical tool for considering the implications of LLMs on literacy development. I set about evidencing that claim below. It is beyond the scope of this paper to provide a detailed review of academic literacies work (see Chanock, Citation2011a, Citation2011b for an excellent review of the historical development of ALL work in Australia; see also Wingate & Tribble, Citation2012 for a discussion of similarities and differences between the academic literacies and English for Academic Purposes approaches).

Examples of embedding academic literacies instruction in disciplinary teaching are particularly common in Australia (Black & Rechter, Citation2013; Brooman-Jones et al., Citation2011; Dooey & Grellier, Citation2020; Einfalt & Turley, Citation2009; Fenton-Smith & Frohman, Citation2013; Frohman, Citation2012; Glew et al., Citation2019; Harris, Citation2016; Harris & Ashton, Citation2011; Lear et al., Citation2016; Powell & Singh, Citation2016), but also represented in the UK (Calvo et al., Citation2020; Donovan & Erskine-Shaw, Citation2020; Fernando, Citation2018; Hathaway, Citation2015), New Zealand (Gunn et al., Citation2011; Wette, Citation2019), and South Africa (Batyi, Citation2022; Jacobs, Citation2010) across the sciences, social sciences, and humanities. The outcomes of these embedded academic literacy approaches depend on the researchers’ evaluation measures (see Green & Agosti, Citation2011, for a discussion of evaluating the efficacy of ALL interventions), but (based on the previously cited studies), outcomes typically involve reported increases in student confidence, performance, and retention. Embedding literacy instruction in subject content can benefit all students, as university reading and writing practices can be opaque to anyone unfamiliar with tertiary education. Furthermore, the benefits of making hegemonic discourse practices more visible may particularly benefit culturally and linguistically diverse students, students from low-socioeconomic backgrounds, and first-in-family students. Interventions typically (though not always) take the form of ALL practitioners working with disciplinary experts to embed academic communication within teaching contexts. These broad applications demonstrate the widespread relevance and usefulness of the academic literacies framework. Below, I consider how the framework can be used to understand the interaction between LLMs and university students’ literacy development.

Large language models and literacies development

In this section, I engage with Lea and Street’s (Citation1998) paper, Student writing in higher education: An academic literacies approach, considering how the implications of their framework are affected by LLMs. The dialogue is organised via four block quotations, one for each of the strata shown in and an introductory quotation which overviews the rationale for seeing literacies as practice oriented.

A practices approach to literacy takes account of the cultural and contextual component of writing and reading practices, and this in turn has important implications for an understanding of student learning … Viewing literacy from a cultural and social practice approach (rather than in terms of educational judgements about good and bad writing) and approaching meanings as contested can give us insights into the nature of academic literacy in particular and academic learning in general. (Lea & Street, Citation1998, p. 158)

Large language models are capable of producing detailed and dense summaries of written texts (Ouyang et al., Citation2022), especially when directed through iterative prompts (Adams et al., Citation2023). As of September 2023, ChatGPT users can ‘help [their] child with a math problem by taking a photo, circling the problem set, and having it share hints with both of you’ (OpenAI, Citation2023, para. 2). These developments open new possibilities for students to engage with multimodal texts, such as a textbook chapter with images, diagrams, and practice questions.

For students, the threat or benefit will depend on their use of LLMs. What is ultimately at stake here is the potential for various readings as Hall (Citation1973) describes them – and by ‘at stake’, I mean both the potential for something to be lost or gained. Hall describes three possible readings: a dominant reading, where the audience accepts the author’s intended message; an oppositional reading, where the audience rejects the author’s intended message; and a negotiated reading, an intermediate, where the audience accepts some elements of the message while rejecting others.

If a student asks ChatGPT to summarise a journal article, accepts the summary as accurate, and cites the source in their assessment based solely on the summary, they relegate themselves to a dominant reading – one where the text’s intended message is accepted without critical engagement. Even if the summaries produced by LLMs were always accurate, which they aren’t (OpenAI, Citationn.d.), by not engaging with the original reading, a student forfeits their ability to engage in negotiated or oppositional readings.

Students’ critical and nuanced engagement with the texts they read is clearly desirable. But this sort of reading relies on students actually comprehending what they read, in other words, using textual information and background knowledge to actively create meaning and draw inferences. Freebody and Luke (Citation1990) describe this as acting as a ‘text participant’, and it is particularly relevant for university students who are likely to encounter new genres for the first time in their studies (e.g., journal articles, business reports, lab reports). For students, navigating these texts is undoubtedly confronting, but it is also undoubtedly useful. Consequently, students need time (and cognitive effort) to be directed to reading carefully; student use of LLMs stands to disrupt these processes. As a result, two orders of cognitive process are at risk: a so-called ‘lower-order’ process like understand (and its attendant processes, like interpret and summarise) and a so-called ‘higher-order’ process like evaluate.

What I am referring to here is Bloom’s Taxonomy, specifically Krathwohl’s (Citation2002) excellent revision of Bloom’s already powerful framework. Above, I have very deliberately framed the described cognitive processes as ‘so-called’ lower or higher order, because Rivers and Holland (Citation2023) note that tools like ChatGPT may actually invert the hierarchy; processes like create are now almost instant and require only a prompt, while processes like remember are now the domain of experts who take the time to read and learn information rather than relying on explanations from LLMs. Consequently, LLMs have the potential to disrupt what was once considered a relatively stable hierarchy of cognitive complexity.

There is, however, potential for gain here, too. If a student uses an LLM’s summary as a counterpoint to their own summary, the opportunities for Hall’s (Citation1973) negotiated and oppositional readings are reinstated (and perhaps increased). Just as a skilled instructor can trouble a student’s assumptions through dialogue, so too can tools like ChatGPT provide a mechanism for alternative readings. Lodge, Yang, et al. (Citation2023) draw a distinction between ‘cognitive offloading’, where mundane tasks like arithmetic are offloaded to a calculator (even though a human could perform the calculations manually), and ‘extended mind’, where generative AI opens up possibilities that would not be possible by a human alone. The distinction is a useful one, and it captures the difference between what stands to be lost or gained by using LLMs in reading and writing processes – if a student simply offloads their reading because they lack the time or motivation to read, then something is lost, but if a student extends their reading (e.g., asking an LLM to provide guiding questions for reading, asking an LLM to challenge a summary the student has provided), then something is gained. That something is the cognitive and social processes that are so closely tied to learning. With this context established, I now move through the different aspects of literacy involved in the academic literacies framework.

The study skills approach has assumed that literacy is a set of atomised skills which students have to learn and which are then transferable to other contexts. The focus is on attempts to ‘fix’ problems with student learning, which are treated as a kind of pathology. The theory of language on which it is based emphasises surface features, grammar and spelling. Its sources lie in behavioural psychology and training programmes and it conceptualises student writing as technical and instrumental. (Lea & Street, Citation1998, pp. 158–159)

Overall, LLMs are probably positioned to disrupt this aspect of literacy least. Technology has been correcting (or attempting to correct) spelling since the late 1950s, well before the advent of personal computers (Mitton, Citation2010). Grammarly, launched in 2009, now has 30 million daily users, and it has recently begun integrating generative AI (Lytvyn, Citation2022). The ubiquity of spelling and grammar services in word processing software means that it is small, logical step to use LLMs for proofreading support. Grammar, punctuation, and spelling are, of course, dynamic and context-sensitive (as with any aspect of language), but much academic and professional writing produced by students will tend to be directed by style guides anyway. If students use tools like ChatGPT to identify missing commas or incorrect semi-colons, their literacy development is unlikely to be negatively affected – many guides for career academics already recommend that drafts are read by others (e.g., Belcher, Citation2019; Silvia, Citation2018; Sword, Citation2017). In fact, LLMs may actually support student literacy development by providing opportunities to prompt generative AI applications to explain their corrections. There is, it seems, more at stake when we consider how LLMs interact with the more nuanced views of literacy, discussed below.

From the academic socialisation perspective, the task of the tutor/adviser is to induct students into a new ‘culture’, that of the academy. The focus is on student orientation to learning and interpretation of learning tasks, through conceptualisation, for instance, of a distinction between ‘deep’, ‘surface’ and ‘strategic’ approaches to learning … It appears to assume that the academy is a relatively homogeneous culture, whose norms and practices have simply to be learnt to provide access to the whole institution … this approach tends to treat writing as a transparent medium of representation and so fails to address the deep language, literacy and discourse issues involved in the institutional production and representation of meaning. (Lea & Street, Citation1998, p. 159)

That universities have particular ways of reading and writing is probably not news to anyone, even those who have never studied or worked in higher education. The challenge for students entering the academy is understanding what these specialised reading and writing practices actually are (Bartholomae, Citation1986). After completing compulsory schooling, most, if not all, students in English-speaking countries will have some experience with sustained academic writing in subjects like English, Science, and History. They will have spent years developing their linguistic repertoire for reading and writing (Christie, Citation2012; Christie & Derewianka, Citation2008; Derewianka, Citation2020). They will also be generally underprepared for academic writing’s focus on carefully hedged claims (Aull, Citation2015) and believe that good essay writing involves being as verbose as possible (Anson, Citation2017; Rosser, Citation2002). Learning to read and write at university, therefore, involves an understanding of the culture of communication, as it does with learning to communicate effectively in any context (Gee, Citation2008). It is precisely this learning that LLMs stand to disrupt.

Although each discipline has its own idiosyncrasies, practices like applying theory, developing arguments, marshalling evidence, integrating citations, and discussing implications are relatively common in all parts of the academy. Baker et al. (Citation2019) astutely note that much academic literacies-oriented research has traditionally focused on writing at the expense of reading, arguing that learning to read within the disciplines is as important as learning to write within them. In other words, being able to do the ‘work’ of the university means being able to traffic in the central practices of reading and writing that are common across disciplines. These practices form (at least in part) the habitus of the university: ‘systems of durable, transposable dispositions, structured structures predisposed to function as structuring structures, that is, as principles which generate and organize practices and representations that can be objectively adapted to their outcomes’ (Bourdieu, 1980/Citation1989, p. 53). In this way, becoming part of the academic community means internalising (or, at least, learning to imitate) the practices of the community – acquiring the cultural capital, or perhaps academic capital, that is valued within the institution; that is, the sets of ‘long-lasting dispositions of the mind and body’ (Bourdieu, 1983/Citation1986, p. 243). For students, it is precisely the cognitive effort of reading and writing that socialises them into these valued dispositions (e.g., the importance of evidence, academic integrity, the value of clear communication, etc.). As Bourdieu’s (1983/Citation1986) clever analogies illustrate, the accumulation of this kind of capital is ‘like the acquisition of a muscular physique or a suntan[;] it cannot be done second hand (so that all effects of delegation are ruled out)’ (p. 244). By delegation, Bourdieu was referring to the owner of capital transferring it immediately to another (as can be done with academic capital). But the term works usefully for the present discussion, too; the development of academic capital cannot be delegated; if a student does not engage in the deliberate process of academic socialisation and instead ‘delegates’ their cognitive effort to an LLM, they risk the opportunity to learn how to navigate the academy successfully. I discuss the implications for instructors in the following section and turn my attention now to the academic literacies approach.

[The academic literacies] approach sees literacies as social practices, in the way we have suggested. It views student writing and learning as issues at the level of epistemology and identities rather than skill or socialisation. An academic literacies approach views the institutions in which academic practices take place as constituted in, and as sites of, discourse and power. It sees the literacy demands of the curriculum as involving a variety of communicative practices, including genres, fields and disciplines. From the student point of view a dominant feature of academic literacy practices is the requirement to switch practices between one setting and another, to deploy a repertoire of linguistic practices appropriate to each setting, and to handle the social meanings and identities that each evokes. This emphasis on identities and social meanings draws attention to deep affective and ideological conflicts in such switching and use of the linguistic repertoire. (p. 159)

This is because in order for students to understand how texts structure and are structured by epistemology and power, they need to see texts ‘in action’. In other words, there needs to be an explicit discussion about how a text’s language choices are (or are not) suitable within disciplinary contexts. This discussion relies on having an actual instance of text to discuss. As a result, students are likely to be working with texts that already exist, either disciplinary texts or their own drafts. Working with these texts, instructors are able to explicitly discuss why they are (or are not) effective within their disciplinary contexts. They are also able to use LLMs’ creation or transformation of texts to lead discussions about epistemology and power, as well as how they are structured through language. I now turn to these considerations for practice.

Implications for higher education: developing students’ academic literacies

Above, I have explored how LLMs intersect with literacy development. Although Lea and Street (Citation1998) were writing well before the wide availability of Large Language Models, their framework provides a powerful tool for understanding how students engage with reading and writing, and ultimately learning, at universities. Some preliminary implications for university educators are as follows.

From the study skills view of literacy, editing and proofreading can be complemented by LLMs. This usage is a logical extension of what is now ubiquitous in word processing software (e.g., spelling and grammar checking). Students should be encouraged to prompt the LLM to explain and justify its revisions; this may allow students to further develop their understanding of editing and proofreading. As I have argued above, students’ literacy as solely grammatical correctness is least at risk from LLMs, and this is already a limited view of effective communication. Therefore, if there is any use of LLMs that instructors should feel comfortable with, it is likely this one.

From the academic socialisation view of literacy, LLMs are a significant risk to student literacy development. Consequently, LLMs should either be avoided or deployed with strict controls during students’ first round of reading, planning, or drafting. Many students will likely use these tools anyway, which is why it is critical that students are provided with time in class to actually practice reading and writing with instructor support and without LLM support, particularly in their first year of university study. Skipping the cognitive work of understanding how to read strategically, how to form an argument, how to synthesise the evidence, and so forth risks disrupting the acquisition of capital and the development of students’ habitus. Consequently, students risk moving through their studies as academic imposters, relying on LLMs as a substitute for (rather than complement to) their own cognitive processes. Kasneci et al. (Citation2023), for example, suggest that university students can use LLMs to ‘generate summaries and outlines of texts, which can help students to quickly understand the main points of a text and to organise their thoughts for writing’ (p. 2). In light of the discussion above, however, I believe that this use is dangerous (especially if left unchecked). It suggests that by the time students reach university, their reading abilities are thoroughly developed and that reading is simply a matter of accumulating enough information to begin writing, rather than a meaning-making and knowledge-construction process. To be clear, I am not arguing that students can never use LLMs to help them read and write – but I am suggesting that students, especially in the first year, must be given adequate time and support to learn to read and write without LLMs before they begin to integrate them into their own literacies repertoire.

From the academic literacies view of literacy, LLMs are less of a threat to students’ literacy development. LLMs can be used to help students understand the differences between disciplines, as long as these processes are explicitly supported by instructors. For example, a student might be tasked with using an LLM to transform a text written in one discipline to make it suitable for another. The output will likely be unsatisfactory without modification, which can prompt discussions about how and why a particular text is (or is not) suitable for Biology, Business, or History writing. Discussions of epistemology and power are also engendered by asking students to transform text in disciplinary settings; questions like Whose or what knowledge is being represented here? and Is this knowledge, or just the appearance of knowledge? are good starting places to discuss institutional power in both the discipline and LLMs. The key difference from the academic socialisation threat above is that students should be transforming existing text, rather than asking LLMs to create text for them. If instructors wish to actively encourage students to engage with LLMs, it is likely this sort of use (transforming, not creating) that will benefit literacy development.

In conversing with Lea and Street (Citation1998), I have presented my analysis in stages to reflect their three aspects of literacy. Literacy development, however, is a dynamic process, and in reality, these three aspects are happening simultaneously, regardless of the influence of LLMs. In terms of theory, LLMs highlight the importance of carefully considering how new technologies interface with pedagogy. While tools like ChatGPT might increase the efficiency of expert readers and writers who have already spent many years refining their practice, they do not necessarily increase the efficiency of learning to read and write in university contexts.

In practice, then, instructors should actively model their (non-) use of LLMs. Saying to students ‘here is what counts as acceptable and unacceptable use of AI; now go and complete your assessments’ is probably insufficient for literacy development at the university level (and likely even more so at primary and secondary levels), in the same way that saying ‘make your analysis more critical’ or ‘ensure your writing is appropriately academic’ is insufficient. In this case, LLMs are simply a reminder of what we have known long before they arrived – literacy development requires regular opportunities for expert modelling, practice, and feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adams, G., Fabbri, A., Ladhak, F., Lehman, E., & Elhadad, N. (2023). From Sparse to dense: GPT-4 summarization with chain of density prompting. arXiv.Org. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2309.04269

- Anson, D. W. J. (2017). Examining the examiners: The state of senior secondary English examinations in Australia. The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 40(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03651991

- Anthropic. (2023, March 14). Introducing claude. Anthropic Blog. https://www.anthropic.com/index/introducing-claude.

- Aull, L. (2015). First-year university writing: A corpus-based study with implications for pedagogy. Palgrave Macmillan

- Baker, S., Bangeni, B., Burke, R., & Hunma, A. (2019). The invisibility of academic reading as social practice and its implications for equity in higher education: A scoping study. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(1), 142–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1540554

- Bartholomae, D. (1986). Inventing the university. Journal of Basic Writing, 5(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.37514/JBW-J.1986.5.1.02

- Batyi, T. (2022). Enhancing the quality of students’ academic literacies through translanguaging. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 35(3), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2022.2076865

- Belcher, W. L. (2019). Writing your journal article in twelve weeks: A guide to academic publishing success (2nd ed.). The University of Chicago Press.

- Black, M., & Rechter, S. (2013). A critical reflection on the use of an embedded academic literacy program for teaching sociology. Journal of Sociology, 49(4), 456–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783313504056

- Bloomberg News. (2023, August 22). ChatGPT-Wary universities scramble to prepare for school year [Post]. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/chatgpt-wary-universities-scramble-prepare-school-year/?trk=pulse-article.

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood. (Original work published 1983).

- Bourdieu, P. (1989). The logic of practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Polity. (Original work published 1980).

- Bridgeman, A., Liu, D., & Miller, B. (2023, February 28). How ChatGPT can be used at unit to save time and improve learning. University of Sydney, News & Opinion. https://www.sydney.edu.au/news-opinion/news/2023/02/28/how-chatgpt-can-be-used-at-uni-to-save-time-and-improve-learning.html.

- Brooman-Jones, S., Cunningham, G., Hanna, L., & Wilson, D. N. (2011). Embedding academic literacy: A case study in business at UTS : Insearch. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 5(2), A1–A13.

- Calvo, S., Celini, L., Morales, A., Guaita Martinez, J. M., & Nunez-Cacho Utrilla, P. (2020). Academic literacy and student diversity: Evaluating a curriculum-integrated inclusive practice intervention in the United Kingdom. Sustainability, 12(3), 1155. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031155

- Carroll, L., & Carey, A. (2023, April 5). University cheats on notice after launch of ChatGPT detection software. The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/education/university-cheats-on-notice-after-launch-of-chatgpt-detection-software-20230403-p5cxpc.html.

- Casal, J. E., & Kessler, M. (2023). Can linguists distinguish between ChatGPT/AI and human writing? A study of research ethics and academic publishing. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics, 2(3), 100068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmal.2023.100068

- Chanock, K. (2011a). A historical literature review of Australian publications in the field of academic language and learning in the 1980s: Themes, schemes, and schisms: Part one. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 5(1), A36–A58.

- Chanock, K. (2011b). A historical literature review of Australian publications in the field of academic language and learning in the 1980s: Themes, schemes, and schisms: Part two. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 5(1), A59–A87.

- Christie, F. (2012). Language education throughout the school years: A functional perspective. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Christie, F., & Derewianka, B. (2008). School discourse learning to write across the years of schooling. Continuum.

- Derewianka, B. (2020). Growing into the complexity of mature academic writing. In H. Chen, D. Myhill, & H. Lewis (Eds.), Developing writers across the primary and secondary years: Growing into writing (pp. 194–211). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003018858-11

- Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2018). BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1810.04805

- Donovan, C., & Erskine-Shaw, M. (2020). 'Maybe I can do this. Maybe I should be here’: Evaluating an academic literacy, resilience and confidence programme. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(3), 326–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2018.1541972

- Dooey, P. M., & Grellier, J. (2020). Developing academic literacies: A faculty approach to teaching first-year students. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 14(2), 106–119.

- Einfalt, J. T., & Turley, J. (2009). Engaging first year students in skill development: A three-way collaborative model in action. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 3(2), A105–A116.

- Fenton-Smith, B., & Frohman, R. (2013). A scoping study of academic language and learning in the health sciences at Australian universities. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 7(1), A61–A79.

- Fernando, W. (2018). Show me your true colours: Scaffolding formative academic literacy assessment through an online learning platform. Assessing Writing, 36, 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2018.03.005

- Floridi, L., & Chiriatti, M. (2020). GPT-3: Its nature, scope, limits, and consequences. Minds and Machines, 30(4), 681–694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-020-09548-1

- Freebody, P., & Luke, A. (1990). Literacies programs: Debates and demands in cultural context. Prospect: Australian Journal of E.S.L, 5(3), 7–16.

- Frohman, R. (2012). Collaborative efforts work! Reflections on a two-year relationship between faculty of health and international student services—language and learning unit. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 6(3), A47–A58.

- Gee, J. P. (2008). Social linguistics and literacies: Ideology in discourses (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Glew, P. J., Ramjan, L. M., Salas, M., Raper, K., Creed, H., & Salamonson, Y. (2019). Relationships between academic literacy support, student retention and academic performance. Nurse Education in Practice, 39, 61–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2019.07.011

- Goldingay, S., Hitch, D., Carrington, A., Nipperess, S., & Rosario, V. (2016). Transforming roles to support student development of academic literacies: A reflection on one team’s experience. Reflective Practice, 17(3), 334–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2016.1164682

- Green, T., & Agosti, C. (2011). Apprenticing students to academic discourse: Using student and teacher feedback to analyse the extent to which a discipline-specific academic literacies program works. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 5(1), A18–A35.

- Gunn, C., Hearne, S., & Sibthorpe, J. (2011). Right from the start: A rationale for embedding academic literacy skills in university courses. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 8(1), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.8.1.6

- Hall, S. (1973). Encoding and decoding in the television discourse. University of Birmingham.

- Harris, A. (2016). Integrating written communication skills: Working towards a whole of course approach. Teaching in Higher Education, 21(3), 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2016.1138456

- Harris, A., & Ashton, J. (2011). Embedding and integrating language and academic skills: An innovative approach. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 5(2), A73–A87.

- Hathaway, J. (2015). Developing that voice: Locating academic writing tuition in the mainstream of higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 20(5), 506–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2015.1026891

- Jacobs, C. (2010). Collaboration as pedagogy: Consequences and implications for partnerships between communication and disciplinary specialists. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 28(3), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2010.545025

- Kasneci, E., Sessler, K., Küchemann, S., Bannert, M., Dementieva, D., Fischer, F., Gasser, U., Groh, G., Günnemann, S., Hüllermeier, E., Krusche, S., Kutyniok, G., Michaeli, T., Nerdel, C., Pfeffer, J., Poquet, O., Sailer, M., Schmidt, A., Seidel, T., … Kasneci, G. (2023). ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and Individual Differences, 103, 102274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2023.102274

- Kirk, T. (2023, April 5). ChatGPT (We need to talk). University of Cambridge, Stories. https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/ChatGPT-and-education.

- Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 212–218. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2

- Lea, M. R., & Street, B. V. (1998). Student writing in higher education: An academic literacies approach. Studies in Higher Education, 23(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079812331380364

- Lea, M. R., & Street, B. V. (2006). The ‘Academic Literacies’ model: Theory and applications. Theory Into Practice, 45(4), 368–377. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4504_11

- Lear, E., Li, L., & Prentice, S. (2016). Developing academic literacy through self-regulated online learning. Student Success, 7(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.v7i1.297

- Liang, W., Yuksekgonul, M., Mao, Y., Wu, E., & Zou, J. (2023). GPT detectors are biased against non-native English writers. Patterns (New York, N.Y.), 4(7), 100779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2023.100779

- Lodge, J. M., Thompson, K., & Corrin, L. (2023). Mapping out a research agenda for generative artificial intelligence in tertiary education. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 39(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.8695

- Lodge, J. M., Yang, S., Furze, L., & Dawson, P. (2023). It’s not like a calculator, so what is the relationship between learners and generative artificial intelligence? Learning, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/23735082.2023.2261106

- Lytvyn, M. (2022, November 9). A history of innovation at Grammarly. Grammarly Blog. https://www.grammarly.com/blog/grammarly-12-year-history/.

- Meyer, J. G., Urbanowicz, R. J., Martin, P. C. N., O’Connor, K., Li, R., Peng, P.-C., Bright, T. J., Tatonetti, N., Won, K. J., Gonzalez-Hernandez, G., & Moore, J. H. (2023). ChatGPT and large language models in academia: Opportunities and challenges. BioData Mining, 16(1), 20–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13040-023-00339-9

- Microsoft. (n.d.). Bing chat. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/edge/features/bing-chat?form=MT00D8.

- Mitton, R. (2010). Fifty years of spellchecking. Writing Systems Research, 2(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/wsr/wsq004

- OkSquash1234. (2023, July 31). Frustrated with student use of ChatGPT [Online forum post]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/academia/comments/15e2vtz/frustrated_with_student_use_of_chatgpt/.

- OpenAI. (2022, November 30). Introducing ChatGPT. OpenAI Blog. https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt.

- OpenAI. (2023, September 25). ChatGPT can now see, hear, and speak. OpenAI Blog. https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt-can-now-see-hear-and-speak.

- OpenAI. (n.d.). How can educators respond to students presenting AI-generated content as their own? Educator FAQ. https://help.openai.com/en/articles/8313351-how-can-educators-respond-to-students-presenting-ai-generated-content-as-their-own.

- Ouyang, L., Wu, J., Jiang, X., Almeida, D., Wainwright, C. L., Mishkin, P., Zhang, C., Agarwal, S., Slama, K., Ray, A., Schulman, J., Hilton, J., Kelton, F., Miller, L., Simens, M., Askell, A., Welinder, P., Christiano, P., Leike, J., & Lowe, R. (2022). Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2203.02155

- Pichai, S. (2023, February 6). An important next step on our AI journey. The Keyword. https://blog.google/technology/ai/bard-google-ai-search-updates/.

- Powell, L., & Singh, N. (2016). An integrated academic literacy approach to improving students’ understanding of plagiarism in an accounting course. Accounting Education, 25(1), 14–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2015.1133311

- Rivers, C., & Holland, A. (2023, August 30). How can generative AI intersect with Bloom’s taxonomy? Times Higher Education, Inside Higher Ed. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/how-can-generative-ai-intersect-blooms-taxonomy.

- Rosser, G. (2002). Examining HSC English: Questions and answers. Change, 5(2), 91–109.

- Shearing, H., & McCallum, S. (2023, May 9). ChatGPT: Can students pass using AI tools at university. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/education-65316283.

- Silvia, P. J. (2018). How to write a lot: A practical guide to productive academic writing (2nd ed.). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1chrsg5

- Sword, H. (2017). Air & light & time & space: How successful academics write. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674977617

- Tay, Y., Dehghani, M., Bahri, D., & Metzler, D. (2023). Efficient transformers: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys, 55(6), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1145/3530811

- Teubner, T., Flath, C. M., Weinhardt, C., van der Aalst, W., & Hinz, O. (2023). Welcome to the era of ChatGPT et al: The prospects of large language models. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 65(2), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-023-00795-x

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, Ł, & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. In I. Guyon, U. V. Luxburg, S. Bengio, H. Wallach, R. Fergus, S. Vishwanathan, & R. Garnett (Eds.), Advances in neural information processing systems (Vol. 30). Curran Associates, Inc. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2017/file/3f5ee243547dee91fbd053c1c4a845aa-Paper.pdf.

- Wette, R. (2019). Embedded provision to develop source-based writing skills in a year 1 health sciences course: How can the academic literacy developer contribute? English for Specific Purposes, 56, 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2019.07.002

- Wingate, U. (2006). Doing away with ‘study skills’. Teaching in Higher Education, 11(4), 457–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510600874268

- Wingate, U. (2012). Using academic literacies and genre-based models for academic writing instruction: A ‘literacy’ journey. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 11(1), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2011.11.006

- Wingate, U., & Tribble, C. (2012). The best of both worlds? Towards an English for academic purposes/academic literacies writing pedagogy. Studies in Higher Education, 37(4), 481–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.525630

- Wittman, K., & Kindley, E. (2022). Introduction. In E. Kindley & K. Wittman (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to the essay (pp. 1–14). Cambridge University Press; Cambridge Core. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009022255.001