ABSTRACT

Universities continue to evolve and adapt to changes brought about by external events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, shifts in government policy, technological advancements, and geopolitics. A significant body of research has focused on negative workplace conditions within universities that contribute to psychosocial hazards. In contrast, this paper reports on the experiences and perceptions of 36 fulltime, continuous, academic staff to explore how they and their colleagues found and/or experienced joy in work set against the backdrop of crisis and change as their universities responded to the impacts of COVID-19. Responses clustered around four key dynamics: joy/student, joy/teaching, joy/research, and joy/colleague. Despite being in work environments characterised largely in negative terms, where agency and voice are constrained, these joys sustained and evoked feelings of purpose, belonging, and connection. This research highlights the need to reconsider how to provide and support healthy work conditions to optimise opportunities for the academic workforce to experience greater joy in their work. The implications for future research are presented.

Introduction

The conditions that afford joy in work for many academic staff are diminishing. The integration of neoliberal policies and employment practices across the higher education sector have profoundly changed what it is like for academic staff to work in a university and experience joy in their work. For example, new public management practices directly and indirectly influence and shape the organisational culture of universities as workplaces and academic labour (Field, Citation2015). The rise of managerialism as Barclay (Citation2021) observes, for example, has also contributed to the reshaping of academic labour through processes such as specialisation and increased academic casualisation. Surveying the transformation of the higher education sector as it is, ‘restructured, commodified and marketized by neoliberal capitalism’ Sutton (Citation2017) writes, ‘the soul of academic labour is becoming lost in performativity’ (p. 625). The higher education sector is further characterised by job insecurity, intensification of ‘administrivia’ and ‘busy work’, hyper-bureaucracy, exploitative workloads, and accountability regimes (Churcher & Talbot, Citation2020) that also change the academic role.

Neoliberal ideologies and management practices, increased accountability and performance expectations, top-down management and intensification of work, in tandem with decreased power and autonomy of academic staff, have profoundly altered the academic work environment (Kenny & Fluck, Citation2022a). McGaughey et al. (Citation2021) observed the Australian university sector has not only endured the reforms of neoliberal practices, but also the ‘instrumentalist and fiscal rationalisation of universities as incubators of workforce talent and drivers of the knowledge economy’ (pp. 2–3). Kenny and Fluck (Citation2022a) observe that the resultant efficiency gains derived from these activities have ‘been achieved through a deterioration in [academics’] working conditions’ (p. 1385). A situation echoed in many countries.

As universities across Australia responded to COVID-19, which is viewed as both a crisis and driver of significant change (McGaughey et al., Citation2021), academic staff not only experienced intensified structural reform, academic job shedding, and reductions in remuneration (Markey, Citation2020), they were expected to pivot to online teaching, accommodate increased class sizes, and increased teaching hours. Moreover, for many academic staff, research workload allocations were heavily reduced or entirely cut. Concurrently, expectations related to their research productivity increased. Change, driven by organisational restructuring and the centralisation of support services subsequently increased administrative burdens placed on academic staff, often resulting in increased physical and psychological demands on the fulltime, continuous academic workforce (McGaughey et al., Citation2021).

Responding to the state of the workplace environment in the Australian university sector, the Australian Universities Accord Interim Report states that ‘higher education institutions need to be better and safer places to work’, and ‘enhancing wellbeing for staff, and appropriate workforce arrangements’ should now be considered a priority (O’Kane et al., Citation2023, p. 21). This paper aims to address this call to action by highlighting how joy in academic work manifests, and how the conditions that promote joy in work can be optimised.

The following first defines joy and then elaborates why a focus on joy in work is necessary in the higher education context. Joy is then operationalised by drawing on the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s (IHI) Framework for Improving Joy in Work (Manion Citation2002, Citation2003; Perlo et al., Citation2017). The paper then addresses the study’s research design and findings.

Why focus on joy in work?

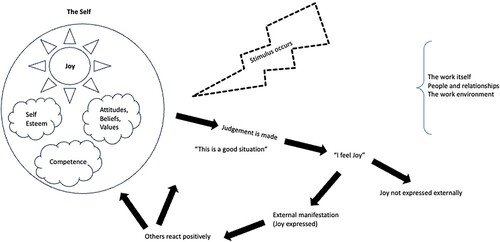

The Oxford English Dictionary defines joy as a ‘vivid emotion of pleasure arising from a sense of well-being or satisfaction; the feeling or state of being highly pleased or delighted; exultation of spirit; gladness, delight’ and/or a ‘pleasurable state or condition; a state of happiness or felicity’. Researching ‘joy at work’ among healthcare workers utilising narrative, qualitative methods, Manion (Citation2002, Citation2003) defines joy as,

an intensely positive, vivid, and expansive emotion that arises from an internal state or that results from an external event or situation. It may include a psychological reaction, an expressive component, as well as a conscious volition. It is a transcendent state of heightened energy and excitement. (Citation2002, p.ii)

Figure 1. A model of joy expressed in the workplace (Manion, Citation2003, p. 657).

Kelsey (Citation2021) observes the infusion of joy in workplaces can enhance performance and success, and contribute to the cultivation of thriving communities and individuals. Watkins et al. (Citation2018) argue that understanding joy is crucial to grasp human flourishing because of the links between positive emotions and subjective well-being. Rutledge et al. (Citation2018) observe that when employees experience meaning and joy in work, job satisfaction, and retention are enhanced. Joy in work is linked with employee well-being, positive mental health, increased motivation, and employee engagement. However, joy in work is also significantly impacted by the workplace environment and conditions, specifically the degree to which the work affords physical and psychological safety, meaning and purpose, choice, and autonomy (Perlo et al., Citation2017) for example.

Yet, as Watkins et al. (Citation2018, p. 522) observe, ‘despite the apparent importance of joy, it appears to be the least studied of the positive emotions’. This is alarming given the fiscal and reputational costs associated with increased absenteeism and stress leave, high employee turnover, intention to leave, and reduced engagement and productivity (Jalilianhasanpour et al., Citation2021). To mitigate against these conditions, Perlo et al. (Citation2017) call for a greater focus on joy in work. This is especially relevant in the higher education sector where universties are not regarded as such ‘good employers, nor seen to be providing for psychosocially safe workplaces’ (see O’Kane et al., Citation2023, pp. 130–131).

What is joy in work?

Joy in work is linked to positive psychology and understood to differ significantly between individuals depending on their wants and needs (Watkins et al., Citation2018). Joy in work can be nurtured (Kern et al., Citation2014) and/or stifled (as it is co-constructed) depending on the cultural, environmental, and structural dynamics within workplaces. Perlo et al. (Citation2017) argue that this is because joy in work is a ‘consequence of systems’ and influenced by ‘management behaviours, systems designs, communication patterns, operating values, and technical supports’ (p. 4). Because it is a system property, Perlo et al. (Citation2017) further contend that joy in work is ‘more than the absence of burnout or an issue of individual wellness, it is “an essential resource”’ (p. 4). This is the conceptualisation adopted in this research.

The IHI Framework for Improving Joy in Work (Perlo et al., Citation2017) is utilised across the healthcare sector. Its application in the higher education context is novel and Manion (Citation2002, Citation2003) provided the basis for our analysis and following critique. The IHI Framework maintains that critical components within a system for ensuring a joyful and engaged workforce include:

Physical and psychological safety – Equitable environment, free from harm; just culture that is respectful

Meaning and purpose – Daily work is connected to what called individuals to practice; line of sight to organisational mission and goals; constancy of purpose

Choice and autonomy – The environment supports choice and flexibility in work and hours

Recognition and rewards – Leaders understand daily work; recognise what team members do; celebrate outcomes

Participative management – Leaders create space to hear, listen, and involve before acting, clear communication and consensus building as a part of decision making

Camaraderie and teamwork – Commensality; social cohesion; productive teams; shared understanding; trusting relationships

Daily improvement – Employing knowledge of improvement science and critical eye to recognise opportunities to improve; regular, proactive learning from defects and successes (Perlo et al., Citation2017, p. 16).

Joy in work is either afforded or inhibited through a complex matrix of factors including the disposition, mindset, and personality of individuals, the characteristics of the way in which individual work is designed, and organisational culture and practices (). These in turn are also influenced by factors in the external environment.

Figure 2. IHI Framework for Improving Joy in Work (Perlo et al., Citation2017).

Research methods

This study was undertaken during 2021 in the context of the ongoing crisis in Australian universities associated with significant structural and operational reform due to COVID-19. Thirty-six fulltime, continuous academic staff from five Western Australia universities (Curtin University, Edith Cowen University, Murdoch University, the University of Notre Dame, and the University of Western Australia) were interviewed. The project utilised an instrumental case study design and approach (Yin, Citation1994) to create data using qualitative interviewing and analysis. The sampling strategy was purposeful, together with snowballing, typical of the case method (Patton, Citation2002).

The project was approved by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2021-0059) prior to the collection of interview data. The qualitative interviews were primarily conducted virtually, one-to-one, in-depth, and semi-structured, ranged between 40 and 90 minutes in duration, and were audio recorded with the consent of participants.

Participant demographics

Each participant was assigned a pseudonym (e.g., P2, P3). The sample (n = 36) comprised only fulltime, continuous academic staff. This is because they represented a more stable workforce. As permanent members of staff they experienced, and had to navigate, all the changes implemented by their universities as they responded to COVID-19 and the resultant fiscal and operational challenges.

Participants were almost evenly divided between Business and Law (n = 12), Health Sciences (n = 11), and Humanities (n = 10) disciplines; with fewer participants from Science and Engineering (n = 2) and a university central division (n = 1). Participants represented all levels of academic appointment: Lecturer Level B (n = 13), Senior Lecturer Level C (n = 4), Associate Professor Level D (n = 9), and Professor Level E (n = 7). Only one Associate Lecturer Level A participated in the study. The sample also included participants who were in academic leadership roles including Deputy Head of School, Dean/Director of Teaching and Learning, Dean/Director of Research and Discipline Leads.

Participants were almost equally divided according to gender with 48% nominating as female and 51% as male. Most participants were 40 years of age or older (72%), had more than 10 years of experience working in the university sector (85%), and had been employed in their current university for more than 5 years at the time of their interview (71%).

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim using the Otter.ai transcription platform (https://otter.ai/). Each transcript was read and verified against the audio recordings and lightly edited for accuracy by the members of the research team.

The transcripts were prepared for line-by-line coding. Employing Coe et al. (Citation2017), independent double coding strategy we commenced by winnowing and then interrogating the data using inductive open coding to identify patterns and generate categories and themes. Then we interrogated the data deductively informed by Manion (Citation2002, Citation2003) and the IHI Framework for Improving Joy in Work (Perlo et al., Citation2017). This process involved reviewing all responses to the question, ‘what brings you joy in work?’ and then coding informants’ responses with descriptive codes. The codes were cross-checked by a second member of the research team and organised into themes aligned with Manion (Citation2002, Citation2003) and the IHI Framework (2017). The data were not comparatively analysed given the uniformity of participants’ responses across the interviews.

Findings

The following first presents a descriptive rendering through the participant voice of how individuals perceived their universities as places of work during and following the COVID-19 crisis, and the changes they experienced. Set against this backdrop participants shared what brings them joy in work. Responses clustered around four key dynamics: joy/student, joy/teaching, joy/research, and joy/colleague, which are now elaborated.

The dominant features in the university work environment do not foster and/or sustain workplace joy

Participants characterised their work environments largely in negative terms except for the collegiality they shared with those in their teaching/research teams. Consistent with the submissions to the Australian University Accord reported by O’Kane et al. (Citation2023), concerns centred on workplace dynamics such as employment insecurity and increased administrative and teaching workloads as conditions that created hardship and stress in their workplace. Many participants attributed a diminishment in their capacity to experience joy in work due to an increase in their physical and psychological burdens, which they maintained contributed to poor health and well-being outcomes. Overwhelmingly, participants described their universities as ‘fraught’, ‘challenging’ workplaces (e.g., P2, P9, P19, P34). The following exemplifies participants’ responses to the first interview questions, ‘what is your university like these days?’; ‘what is it like working there?’; and, ‘what is the mood like?’

Well, it's fairly sad. It's changed a lot over the last, I suppose five or six years, in a sort of generally downward trajectory culminating in this year's huge changes to people's workloads and ways of teaching and freedom to organise their work in the ways that they think would be best. … It's depressing, because I think it largely comes down to a sense of powerlessness that people have. And when things are being done, that don't seem to make sense that and yet there is no right of reply, that then, it's a sense of banging your head against a brick wall. (P11)

Most participants described their institution’s organisational culture and employment practices as being largely ‘exploitative’, ‘oppressive’, ‘toxic’, and ‘fiscally driven’. Most participants reported experiencing feelings associated with burnout, including anxiety, cynicism, depression, exhaustion, overworked, demoralised, and therefore unhappy. Similar appraisals of universities as workplaces have been reported across a range of higher educational contexts including the United Kingdom (Wray & Kinman, Citation2022) and China (Han et al., Citation2020).

Reflecting on their situation and echoing the sentiment of many participants, P19 observed academic staff are feeling ‘disenchanted’, ‘disenfranchised’, ‘alienated’, and ‘disempowered’. This is attributed to a combination of a) not being able to have a voice in decision making (P18), not feeling valued or listened to, and ‘an increasing entrenchment of bureaucratic structures and bureaucratic practices and procedures (P9); and b) a lack of resources and increased demands on their professional and personal time and physical and psychological resources (P28). Most participants reported they have less time to connect with colleagues and family and that they felt increasingly disconnected from their university. presents illustrative exemplars extracted from the interviews of job characteristics perceived to impede joy in work.

Table 1. Institutional and job characteristics impeding workforce joy.

With the instructional and workplace culture and practices in mind, we asked participants what they would say to anyone looking to commence a career in higher education. Some participants positively reflected on previous years like P28 who averred, ‘I loved my career in higher education’. Most participants, however, expressed views like P5 who said ‘be careful what you wish for’ (P5). P36 was forthright in their response, ‘don't do it, it's terrible’. P29, reflecting on the changes in the sector commented, ‘it has changed dramatically in the last 20 years and the good old days have gone’.

The sentiments reported here have been observed elsewhere (Whitsed & Girardi , Citation2022) and reported in the Australian news media, research (c.f., McGaughey et al., Citation2021) and in the Australian University Accord Interim Report (O’Kane et al., Citation2023), which stresses the need for universities to be ‘good employers’ and for them to address issues leading to ‘psychological stress’, ‘employment insecurity’, ‘work(over)load’, inadequate renumeration, and that they provide support for psychological and physical safety.

Recognising the potential emotional impact these first questions might have on participants, and to shift attention from the workplace and how this influenced their experiences, we invited participants to share what brings them joy in work. highlight participant interview answer extracts to the question. Responses clustered around four main dynamics: joy/student, joy/teaching, joy/research, and joy/colleague. Throughout the interviews, participants elaborated further on these particularly in terms of the way these joys have been diminishing, highlighting a broad range of conditions consistent with descriptions of workplace psychosocial hazards (Wray & Kinman, Citation2022).

The joy/student dynamic centred on the sense of connection and the satisfaction associated with seeing students learn, grow, and succeed. Summarising responses, the joy/student dynamic is deeply personal and gratifying. It is future building, and this, as one participant explained, is their ‘soul’. For participants, great joy was derived from seeing their students succeed, and from watching them grow intellectually and professionally as this related to employment outcomes. Responses for this dynamic clustered around meaning and purpose (accomplishment, achievement), people and relationships (connection with others, recognition, and reward), and reward and recognition. highlights exemplars addressing the joy/student dynamic.

Table 2. The joy/student dimensions of workplace joy (Manion, Citation2003; Perlo et al., Citation2017).

However, participants reported that increased workloads and administrative burden caused by centralisation, increased responsibilities and expectations relating to the oversight of casual and/or sessional academic staff, the pivot to online teaching and curriculum redevelopment when travel and movement bans were introduced, further diminished opportunities for interaction with students. The joy associated with working with, and mentoring of, students is well documented (cf., Riddle et al., Citation2017). Barclay (Citation2021) saliently observes,

the dissatisfaction with teaching can be tolerated if they emerge from the unevenness of working with other humans in the classroom or the mundane nature of some of its associated activities, but less so if they are viewed as an external force corrupting the teaching-student relationship or the demands of administrative creep. (p. 39)

The joy/teaching dynamic is expressed through the emphatic words of love. ‘I love teaching!’ (P6, P.4, P31). For participants, the joy/teaching dynamic is knowing and being known by students. It is a connection. It is the feeling of knowing you are making a difference. It is nourishing, rewarding, and sustaining. Teaching is also likened to notions of academic freedom and autonomy. Themes related to this dynamic clustered around meaning and purpose, choice and autonomy, recognition and reward, and camaraderie and teamwork. highlights exemplars addressing the joy/teaching dynamic.

Table 3. The teaching/joy dimensions of workplace joy (Manion, Citation2003; Perlo et al., Citation2017).

While participants reported feeling high levels of joy associated with teaching, many reported they felt they had to divest the attention and time they would normally devote to teaching to survive in their current circumstances, manage time constraints, and personal resources. Many participants lamented they felt they had to compromise on teaching by trading-off on teaching quality and standards to meet what P5 described as ‘absolutely unrealistic … research expectations’ and other expectations related to their productivity and work. This challenged participants’ professional identities and resulted in many feeling conflicted. The following extract exemplifies the sentiment.

In terms of the teaching, the trade-off is, I have to accept that I’m not going to deliver what I might be able to deliver if I had more time. You know that the quality is going to be compromised. It is not going to be as good as I could deliver it. But that’s just the way it is. I can live with that … The fact that I am not delivering as high as I’d like it to be, that’s just the way it is. (P5)

The joy/research dynamic is expressed through the language of ‘passion’. It is the joy of exploration, discovery, and dissemination. It’s the ‘agency’ and satisfaction associated with developing new research and seeing this making a difference. It’s the relationships built with doctoral students and seeing them succeed. The joy/research dynamic is about discovery, personal growth, the desire to learn new things, and achievement. highlights exemplars addressing the joy/research dynamic.

Table 4. The research/joy dimensions of workplace joy (Manion, Citation2003; Perlo et al., Citation2017).

However, while research is associated with joy in their work, to meet the increased workload related to administrative and teaching demands and responsibilities, most participants reported that they had to make trade-offs related to their research activities, similar to Kenny and Fluck (Citation2022b) observations. For example, P10 highlighted a commonly observed issue,

from a research perspective, certainly a lot of our teaching and research staff, are not getting time to do their research. They might have a 30% research allocation, but because the time allocation to teaching is short of what they feel they need and do, it eats into their research time. So, their research outputs are being compromised. And that has an impact on their career progression.

P20 lamented ‘I compromised my research. So, I'm not writing papers. I am not submitting papers. That's clearly the compromise I must make.’ P11 observed,

with my research, I have very little time to do it. But I have commitments to a lot of people on different projects. And so, trying to do them at night on the weekends or clawback a few hours in the week to do it is hard. And telling people this is going to take longer, because I can only literally spend a couple hours a week on whatever it is we're doing. I find that hard.

The joy/colleague dynamic is expressed through words of collegiality, solidarity, and unity. ‘We cry together, we laugh together’ (P8), ‘we support and motive each other’ (P12), participants reported. Participants’ workplace joy is found in camaraderie and teamwork, a sense of common purpose and connection. The social environment was also identified as a contributor to the workplace joy experienced by participants. highlights exemplars addressing the joy/colleague dynamic.

Table 5. The colleagues/joy dimensions of workplace joy (Manion, Citation2003; Perlo et al., Citation2017).

However, despite the joy participants derive from interactions with colleagues, most report a sense of loss and frustration at the breakdown of social connections and networks attributable to organisational restructuring, centralisation, faculty, and/or school mergers. In addition to the loss of colleagues due to organisational change, participants reported experiencing loss as their ‘closest colleagues’ (P9) and ‘friends’ (P28) were relocated (P6) within the organisation or took voluntarily or forced redundancies. Centralisation, participants observed, contributed to a loss of organisational knowledge (P7) and resulted in frustration at not knowing who to go to for assistance with administrative matters. As P28 explained, there has been ‘a massive drop in numbers’ resulting in ‘a skeleton staff within the professional or administrative roles. We have portals now. There's no admin staff that you could just go and ask a question, who knew your discipline inside and out.’ P22 highlighted that disruptions to the social atmosphere and the low numbers of staff coming onto campus to work contributed to a sense of isolation, disconnectedness, and low morale.

Discussion and conclusion

What this research shows is although the conditions in which academics work are complex, challenging, and in flux, individuals still find joy in their academic work across four salient joy dynamics: joy/student, joy/teaching, joy/research, joy/colleague. Through the novel application of the IHI and Manion (Citation2002, Citation2003) frameworks, this research addresses limitations in the existing scholarship exploring the effect of change on universities and academic staff. It has also documented the working lives and careers of individual academics, and has gone some way to address Gannon et al.’s (Citation2019) call ‘ … to consider the ways in which academics engage in moments of resistance’ (p. 48) to the pressures of academic working conditions. While analysing the effects of the crisis and change-linked phenomena that negatively affect the university workforce is important, and research on this abundant, research that moves toward addressing what gives joy to academic staff in their work is essential. Therefore, understanding the role that joy plays in supporting an engaged academic workforce is increasingly relevant (O’Kane et al., Citation2023). This research confirms Barclay’s (Citation2021) observation that teaching, mentoring students and colleagues, and engaging in research are sites of passion and meaning for academics.

For participants in this research, the relational dimensions of their work, whether with students or colleagues, are significant as this relates to their sense of meaning and purpose, identity, affirmation, acknowledgement, and support, which are related to joy in work (Manion, Citation2002, Citation2003; Perlo et al., Citation2017). This is consistent with the antecedents of employee engagement (Meyer & Schneider, Citation2021; Sabagh et al., Citation2018) and the IHI Framework for Improving Joy in Work and Manion (Citation2002, Citation2003). Individuals, as this research shows, find joy in their academic work, irrespective of the prevailing circumstances, when they have meaning, purpose, autonomy, physical, and psychological safety. However, the conditions that contribute to joy, as widely reported across the interviews, are constrained due to the current configuration of academic workload and the structural and systemic issues (e.g., organisational change, fiscal, and human resourcing). In other words, the tension between workload demands and the affordance of time for relationship prioritisation, development, and management.

Performance management and productivity expectations, as Kenny and Fluck (Citation2022a) observe, manifest ‘a fundamental “clash of values” [that] is evident between bureaucratic and academic approaches in the reduced influence of academics over decision making’ (p. 1373), contributing to the loss of academic voice on important questions that undermines the autonomy and intrinsic motivation typically associated with academic work.

Time is at the heart of much of the discord within universities and how this is translated through academic workloads, measured, and valued. Kenny and Fluck (Citation2022b) found because of the way productivity is judged many of their participants, like those in this study, ‘felt disadvantaged because the workload process disregarded or undervalued much of what they did’ (p. 17). Choice and agency are related to time. Similarly, camaraderie and teamwork, in other words, connection, and meaningful interactions with students and colleagues are afforded less opportunities (time) to be realised because of the competing pressures and escalating demands placed on academics (Kenny & Fluck, Citation2014). As Kenny and Fluck (Citation2022b) show through their research, the allocation of workloads across teaching, research, and engagement/service is uneven, often not transparent nor reflective of actual work required and/or performed. As such, many academics, like the participants in this research, have lost faith in their university leaders, mistrust their managers, and disengage (Kenny & Fluck, Citation2022b). This means that the issue of academic workload allocation must be a key consideration for the higher education sector (O’Kane et al., Citation2023) and university leaders if they are to create conditions within the work environment that afford academics to experience joy in work.

In addition to meaning and purpose, agency, and the degree to which one experiences this is a determinate of joy in work and employee engagement (Meyer & Schneider, Citation2021). As Kenny and Fluck (Citation2022b) maintain, the allocation of workload is interpreted by academic staff, who have limited access to power to challenge how workloads – time – is allocated, is not transparent, nor a true reflection of the time required to complete tasks. Time is central to joy/dynamics in academic work. In each joy/dynamic it is time spent preparing quality learning experiences, time spent building quality relationships with students and colleagues, and time spent engaged in research, that has the potential to subvert the hegemon of neoliberal performativity and management practices, which is realised through the exercise of agency and self-determination.

O’Kane et al. (Citation2023) insists universities need to be ‘good employers’ and ‘workplace arrangements need to value staff’ (p. 131). Understanding factors that lead to individuals feeling joy in their work can provide insight into the creation of positive and supportive workplaces and environments that mitigate psychosocial health hazards in the university workplace and increase engagement. For example, Wray and Kinman (Citation2022) found psychosocial hazards in academic work are ‘reliably linked with key outcomes such as mental and physical health problems, impaired job performance, absenteeism, and attrition’ (p. 778). As a minimum response to the university sectors’ duty of care for academic staff, a greater focus on conditions that afford joy in work should be addressed strategically as a way to mitigate academic employee disengagement, psychosocial hazards, and aspects of work that can lead to psychological (e.g., stress, and burnout) or physical harm.

While participants reported a wide array of job conditions which are more typically associated with psychosocial work hazards, the interview data clearly demonstrate that for participants, factors contributing to physical and psychological safety – participative management, choice, autonomy, and daily improvement – are not widely perceived to be priorities in their universities. Rather by embracing the ideologies of neoliberalism and enacting the practices of new managerialism (Deem & Brehony, Citation2005) the conditions that contribute to joy in work for academic staff are being eroded. Writing on universities as ‘feeling institutions’ and academic emotions, Barclay (Citation2021) observed, ‘for most critics of the university, neoliberalism has been associated with an increase in suffering among university workers’ (p. 7). However, as Kern et al. (Citation2014) observed, consistent with our findings, there are moments of joy that keep academics ‘committed and engaged’. O’Kane et al. (Citation2023) write ‘the higher education sector of the future will require a “highly skilled workforce”' and be able to ‘attract the best local and global talent’ (p. 130). To do this, understanding what produces moments of joy in academic work is important, but not enough.

Crisis events like COVID-19 act as amplifiers and catalysts of change, as will climate, geopolitical, and other unseen disruptions. The authors of the Australian Universities Accord Interim report (O’Kane et al., Citation2023) argue the Australian university sector needs ‘bold, long-term change’. to readdress what participants in this research (e.g., P9 & P5) and others (e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2020) describe: university as a toxic and exploitative workplace. Given the systemic issues, positive change, as O’Kane et al. note (Citation2023, p. 88), will require the involvement and action of all stakeholders (academic staff, unions, institutions, and government). University leaders might actively draw upon and implement alternative models of academic work design and reconceptualise how they approach the allocation of academic work and productivity measurement to provide increased opportunities for the experience of joy in academic work. The university sector, like all others, is influenced by drivers in the external environment such as COVID-19 or changes in government policy which cascade into the local environment. Despite not actively engaging with the influence of the external environment the IHI and Manion’s (Citation2002, Citation2003) framework offers individuals, managers, leaders, and senior leaders a systems approach to improving conditions to increase the potential for actualising joy in the work of academics. Alternative models to the design of work derived from other organisational contexts might also be fruitfully applied in university contexts.

A reconceptualisation of academic work allocation and design has the potential to increase academic staff experience of agency, self-efficacy, self-determination, and connectedness, which are all antecedents of joy in work. This, however, will require all stakeholders to think differently. Future research that explores the effects of crisis, change, and psychosocial hazards in the academic work environment and how this influences joy in work for academic staff is needed as a matter of priority.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Anderson, L., Gatwiri, K., & Townsend-Cross, M. (2020). Battling the “headwinds”: The experiences of minoritised academics in the neoliberal Australian university. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 33(9), 939–953. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2019.1693068

- Barclay, K. (2021). Academic emotions: Feeling the institution. Cambridge University Press.

- Churcher, M., & Talbot, D. (2020). The corporatisation of education: Bureaucracy, boredom, and transformative possibilities. New Formations, 100(100), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.3898/NewF:100-101.03.2020

- Coe, R., Waring, M., Hedges, L. V., & Arthur, J. (2017). Research methods and methodologiesin education. Sage.

- Deem, R., & Brehony, K. J. (2005). Management as ideology: The case of ‘new managerialism’ in higher education. Oxford Review of Education, 31(2), 217–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980500117827

- Field, L. (2015). Appraising academic appraisal in the new public management university. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 37(2), 172–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2014.991534

- Gannon, S., Taylor, C., Adams, G., Donaghue, H., Hannam-Swain, S., Harris-Evans, J., Healey, J., & Moore, P. (2019). Working on a rocky shore’: Micro-moments of positive affect in academic work. Emotion, Space and Society, 31, 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2019.04.002

- Han, J., Yin, H., Wang, J., & Bai, Y. (2020). Challenge job demands and job resources to university teacher well-being: The mediation of teacher efficacy. Studies in Higher Education, 45(8), 1771–1785. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1594180

- Jalilianhasanpour, R., Asadollahi, S., & Yousem, D. M. (2021). Creating joy in the workplace. European Journal of Radiology, 145, 110019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2021.110019

- Kelsey, E. A. (2021). Joy in the workplace: The mayo clinic experience. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 17, 413–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/15598276211036886

- Kenny, J., & Fluck, A. E. (2022a). Emerging principles for the allocation of academic work in universities. Higher Education, 83(6), 1371–1388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00747-y

- Kenny, J., & Fluck, A. E. (2022b). Life at the academic coalface: Validation of a holistic academic workload estimation tool. Higher Education, 1–20.

- Kenny, J. D., & Fluck, A. E. (2014). The effectiveness of academic workload models in an institution: A staff perspective. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 36(6), 585–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2014.957889

- Kern, L., Hawkins, R., Falconer Al-Hindi, K., & Moss, P. (2014). A collective biography of joy in academic practice. Social & Cultural Geography, 15(7), 834–851. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2014.929729

- Manion, J. (2002). Joy at work: As experienced, as expressed (Order No. 3056885). https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/joy-at-work-as-experienced-expressed/docview/275923867/se-2

- Manion, J. (2003). Joy at work!: Creating a positive workplace. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 33(12), 652–659. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005110-200312000-00008

- Markey, R. (2020, May 18). Pay cuts to keep jobs: The tertiary education union’s deal with universities explained. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/pay-cuts-to-keep-jobs-the-tertiary-education-unions-deal-with-universities-explained-138623

- McGaughey, F., Watermeyer, R., Shankar, K., Suri, V.R., Knight, C., Crick, T., Hardman, J., Phelan, D., & Chung, R. (2021). ‘This can’t be the new norm’: Academics’ perspectives on the COVID-19 crisis for the Australian university sector. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(7), 2231–2466. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1973384

- Meyer, J. P., & Schneider, B. (2021). The promise of engagement. In J. P. Meyer & B. Schneider (Eds.), A research agenda for employee engagement in a changing world of work (pp. 3–14). Edward Elgar.

- O'Kane, M., Behrendt, L., Glover, B., Macklin, J., Nash, F., Rimmer, B., & Wikramanayake, S. (2023). Australian universities accord interim report. Australian Government Department of Education. https://www.education.gov.au/australian-universities-accord/resources/accord-interim-report

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work, 1(3), 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325002001003636

- Perlo, J., Balik, B., Swensen, S., Kabcenell, A., Landsman, J., & Feeley, D. (2017). IHI Framework for improving joy in work. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement from https://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/Framework-Improving-Joy-in-Work.aspx

- Riddle, S., Harmes, M. K., & Danaher, P. A. (Eds.).(2017). Producing pleasure in the contemporary university. Springer.

- Rutledge, D. N., Wickman, M., & Winokur, E. J. (2018). Instrument validation: Hospital nurse perceptions of meaning and joy in work. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 26(3), 579–588. https://doi.org/10.1891/1061-3749.26.3.579

- Sabagh, Z., Hall, N. C., & Saroyan, A. (2018). Antecedents, correlates and consequences of faculty burnout. Educational Research, 60(2), 131–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2018.1461573

- Sutton, P. (2017). Lost souls? The demoralization of academic labour in the measured university. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(3), 625–636. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1289365

- Watkins, P. C., Emmons, R. A., Greaves, M. R., & Bell, J. (2018). Joy is a distinct positive emotion: Assessment of joy and relationship to gratitude and well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(5), 522–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1414298

- Whitsed, C, & Girardi, A. (2022, 6 June).Where has the joy of working in Australian universities gone? The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/where-has-the-joy-of-working-in-australian-universities-gone-184251

- Wray, S., & Kinman, G. (2022). The psychosocial hazards of academic work: An analysis of trends. Studies in Higher Education, 47(4), 771–782. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1793934

- Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods (2nd ed.). Sage.