ABSTRACT

Co-authorship between doctoral students and their supervisors is a mostly occluded practice, generalised according to the candidates’ disciplines. There is limited understanding of the practice, particularly in humanities, arts, and social sciences (HASS) disciplines. This study explores HASS doctoral students’ and supervisors’ perceptions towards co-authorship during candidature. Focus is given to participants’ motivations, perceived challenges, and reservations about engaging in supervisor-candidate co-authorship. Surveys of 121 doctoral students and 126 supervisors representing 12 HASS disciplines across 18 Australian universities revealed divergent interpretations of co-authorship: although many viewed it as a collaborative process, more than a third of supervisors approached it through the lens of ‘divide and conquer’. Such findings raise important ethical and pedagogical concerns, highlighting the need for clearer terminology and guidelines. We respond to this ambiguity by proposing a new term, ‘collaborative co-authorship’, reconceptualising supervisor-candidate co-authorship in a way that clarifies perceptions towards the practice and presents it as a pedagogical approach to apprentice doctoral students to become fully-fledged academics. It is our hope that this reconceptualisation will equip stakeholders at individual, institutional, and national levels to engage more confidently and intentionally with collaborative co-authorship through PhD candidature.

Introduction

Co-authorship, sometimes referred to as ‘multiple authorship’ or ‘shared authorship’, may be conceived as the process of jointly authoring a publication, resulting in an output by two or more named persons (Macfarlane, Citation2017). Although the practice has been common across science, technology, engineering and medicine (STEM) disciplines where inquiry is generally conducted in laboratory teams (Maher et al., Citation2014), over the past three decades, it has also gained popularity in the humanities, arts and social sciences (HASS) (Henriksen, Citation2016).

While many multi-authored studies are conducted by teams of established researchers, one common model of co-authorship involves collaboration between doctoral supervisors and their candidates.Footnote1 Rising expectations of public dissemination of knowledge and stiff competition for academic positions increasingly compel candidates to publish during candidature, with many universities showcasing high volumes of research output as emblematic of the quality of their education (Lee & Kamler, Citation2008). While many institutions acknowledge that doctoral students can learn how to write article-style manuscripts from their supervisors (Anderson & Okuda, Citation2019), few actually provide supervisors with guidance in the pedagogical processes of enculturating candidates into the publication process (Aitchison et al., Citation2010).

This ambiguity is illustrative of the strong emphasis on compliance found in policies and training for doctoral supervision. For example, the Supervision Guide within the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research (the 2018 Code) specifically details that one of the responsibilities of a doctoral supervisor is to ‘provide [candidates] assistance and, where appropriate, co-author for publications and other research outputs’ (National Health and Medical Research Council [NHMRC], Citation2018, p. 4). Although co-authorship is included as a responsibility, guidelines for this practice are left to institutions to develop, and surveys of such programmes (e.g., Kiley, Citation2011) have found that such instructions are rarely included in supervisory training programmes. Given the value of co-authoring as a pedagogical practice for apprenticing candidates into the complexities of scholarly writing and publishing (Florence & Yore, Citation2004), this lack of attention is somewhat surprising.

This is not to discount the value of other doctoral writing and publishing pedagogies: research has highlighted the many benefits of initiatives such as doctoral writing groups (Hodge & Murphy, Citation2023), structured writing retreats (Carter & Laurs, Citation2018), and seminars and workshops related to writing for publication (Wilkins et al., Citation2021). Supervisor-candidate co-authorship, however, has been promoted as a particularly effective practice, affording candidates with an increased sense of collegiality and improved competitiveness in the academic job market (Kamler & Thomson, Citation2014) and increased attentiveness from supervisor co-authors who are inherently more invested in both the article’s success (Maher et al., Citation2014) and the candidate’s development. For supervisors often overloaded with teaching responsibilities, co-authoring is generally seen as mutually beneficial (Lokhtina et al., Citation2022), as it enables them to reach their own publication targets while ensuring that their students’ research findings are widely disseminated.

Although the benefits of supervisor-candidate co-authorship are evident, it is not without its risks and burdens. For many, the process is fraught with ethical complexities. For example, Macfarlane’s (Citation2017) investigation of the ethics around multiple authorship raised significant concerns about the gift economy in which some candidates feel obliged or are even coerced to include their supervisor’s name as a co-author, even if there is no specific investment from that supervisor as a contributor to the publication. On the other hand, when a supervisor takes an active role in the collaboration, there are often concerns about the time and investment required, such as the lengthy revision and copy-editing process involved (Florence & Yore, Citation2004). Throughout this process, the supervisor is expected to provide expert advice while helping the candidate navigate these unfamiliar processes and the oft-occluded politics inherent to them (Mason, Citation2018).

Despite these noted challenges, the literature largely supports co-authorship between supervisors and candidates, highlighting how such collaborations better position graduates in the post-doctoral market (Liardét & Thompson, Citation2022). Yet, research continues to show that this practice remains unconventional in HASS (Henriksen, Citation2016; Kamler & Thomson, Citation2014; Leane et al., Citation2019), so it is worth asking why such collaborations are not widely practised. The question then remains: If co-authoring provides so many benefits to candidates’ development as a researcher and scholar, what might deter a candidate from co-authoring? Similarly, since supervisors already invest significant time advising a candidate’s project and helping to shape the writing (Carter & Laurs, Citation2018), why would they opt not to co-author? To explore these questions, this descriptive study seeks to examine candidates’ and supervisors’ perceptions towards co-authorship through an investigation of the following research questions:

What motivates doctoral students and supervisors in HASS to co-author with each other during candidature?

What deters HASS doctoral students and supervisors from co-authoring with each other?

What are the challenges that HASS doctoral students and supervisors face when co-authoring?

Methodology

To explore these questions, supervisors and candidates from 18 Australian universities were invited to respond to online surveys. The surveys, one for candidates and the other for supervisors, were administered to the two populations independently rather than to supervisor-student pairs. The questions in these surveys were based on both existing literature (Aitchison et al., Citation2010; Carter & Laurs, Citation2018; Kamler & Thomson, Citation2014) and the co-authoring experiences of the authors who work or study at an Australian university.

An operational definition of co-authorship was foregrounded in both surveys’ instructions: ‘Co-authorship in this survey means: two or more people jointly writing a journal article, academic report, book chapter, or other scholarly output.’ These instructions were then followed by screening questions which ensured that respondents (a) were enrolled/working at an Australian university; (b) considered themselves as working/studying in a HASS discipline; and (for supervisors) (c) had experience co-authoring with their doctoral student(s) during candidature. Each survey included questions about participants’ reasons for and against co-authoring with their supervisor/student.

The Candidate Survey (see Appendix A) consisted of three parts. Section 1 elicited demographic information, area of study, and publishing experience. Section 2 examined students’ expectations, motivations, and reservations regarding co-authoring with their doctoral supervisor(s) during candidature. Section 3 explored past experiences including challenges when co-authoring. Candidates with no experience co-authoring with a supervisor during candidature were not required to answer questions related to past experiences. The Supervisor Survey (see Appendix B) comprised two sections. Section 1 elicited demographic information and doctoral supervision experience. Section 2 explored different aspects of co-authoring with candidates, such as motivations, reservations, challenges, and disciplinary norms.

We used two-phased pilot tests to evaluate the surveys. In the first phase, the two questionnaires in MS Word document form were piloted with the relevant groups (Candidates or Supervisors). Pilot participants were asked to identify items that they felt were unclear, ambiguous, unnecessary, or could be perceived as uncomfortable or difficult to answer. In response to this feedback, the surveys were revised and then uploaded onto an online survey tool, LimeSurvey. The online revised versions were then piloted with different groups of pilot participants (i.e., Phase 2). Based on the Phase 2 participants’ feedback, question wordings were further refined, and the survey design was modified for an improved user experience.

Data collection and analysis

After gaining ethics approval for the project from the authors’ university (No. 52020788019075), participants were recruited in two stages. First, higher degree research (HDR) directors and managers in HASS faculties/departments/schools at 18 Australian universities were requested by email to forward invitations to participate to the relevant populations. Random stratified sampling attracted candidates mainly from seven disciplines (). The Candidate Survey was closed after reaching the required sample size of over 100 responses. Such a sample size allows for disciplinary differences and was achievable within the limited time frame for this study. After data from the students had been collected, doctoral supervisors, mainly in the seven disciplines represented by the students, were emailed individually and invited to complete the survey; email addresses were found on universities’ staff profile pages. Quota sampling was adopted to gain a disciplinary distribution similar to that of the candidates. Eventually, a 20% response rate was achieved, with 126 returns from supervisors. Among the 132 returns from candidates, 11 responses were discarded as they were incomplete or had unreasonable total response times, suggesting an inauthentic response.

Table 1. Disciplinary distribution of doctoral students and supervisors

shows the disciplinary spread of the two groups of respondents. PsychologyFootnote2 had the highest representation (candidates: 24%; supervisors: 22%), and Literature the lowest (candidates: 6%; supervisors: 7%) except for the five disciplines grouped as ‘Other’ (Law, Sociology, Geography, Sport, and Politics).

shows the descriptive statistics for both supervisor and student respondents. In terms of publication and co-authorship, 70% of candidates had publishing experience, but only one-third had co-authored with a supervisor. For the supervisor group, the extent of this experience varied widely: notably, fewer than half had co-authored more than five papers with a doctoral student, even though most (76% of the group) were senior academics (Professor and Associate Professor) and almost two-thirds had over ten years’ supervisory experience.

Table 2. Demographic information of doctoral students and supervisors

The quantitative data were analysed by adopting basic descriptive statistics. Inductive thematic analysis was used to examine the free-text comments from the survey. Themes were identified following steps recommended by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). Initial codes generated by one team member were checked and identified by another. After the codes were sorted into themes, the whole group discussed, refined, and named the final themes.

In total, 121 candidates’ responses were analysed. To answer RQ1 on motivations to co-author with a supervisor, we focused on the data drawn from CS_Q16Footnote3 which allowed participants to respond with more than one answer. This question also included an open-text response in which the candidates could offer further reasons for why they might co-author. To answer RQ2, exploring candidates’ reluctance to co-author, we drew on the responses from CS_Q17 asking why they might not co-author. This question similarly allowed participants to select multiple responses, including an open-text option. Finally, to answer RQ3, we drew on candidates’ responses to CS_Q28 asking for the challenges experienced when co-authoring with their supervisor(s). Notably, only those candidates who had actual co-authorship experience with their supervisors were asked to complete this section (; n = 40). As with the other multiple-choice questions, candidates were prompted to respond with more than one option and write a free-text response, as applicable.

126 supervisor responses were recorded. Given the Supervisor Survey only included supervisors who had co-authoring experience with their doctoral student(s), all respondents were able to speak to their motivations to co-author with a candidate (SS_Q13), the focus of RQ1, as well as the challenges encountered when engaging in such co-authorship (SS_Q23), the focus of RQ3. Supervisors were further asked whether they had ever declined to co-author with one of their candidates (SS_Q14); 51 of the supervisors indicated having such an experience. These supervisors were then asked to elaborate on the reasons that influenced that decision (SS_Q15), which are reported in the RQ2 findings below.

Findings

Reasons for co-authoring

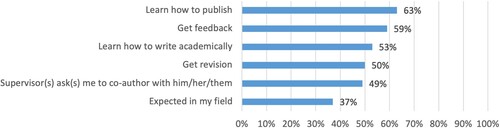

RQ1 explores the factors that impact candidates’ and supervisors’ decisions to collaborate on a publication during candidature. The primary reasons candidates gave for their positive inclinations towards co-authorship were ‘learning to publish’ (63%), ‘getting feedback’ (59%), and ‘learning to write academically’ (53%). As illustrated in , four of the six most cited motivations for co-authoring relate to the publication and writing process.

Optional free-text responses to this question (CS_Q16) help explain this emphasis on the process of writing, revealing how students can feel inexperienced and lack confidence to publish as sole authors. For example, one respondent reported that co-authoring helped themFootnote4 feel ‘more comfortable having someone guide me, [I’m] not ready to sole-author,’ while another noted, ‘I don’t have experience or confidence to know what is good enough to publish.’ Sometimes supervisors recognised their students’ timidity or lack of confidence to publish and would initiate the co-authoring process, as one student explained: ‘ … I wasn’t confident to publish in that journal. [My supervisor] offered to co-author, and it was a great experience.’

Apart from being apprenticed through the publication process, other free-text comments focused on pragmatic goals, such as students’ desire to enhance their resume and position themselves for future careers. For instance, one respondent explained: ‘I asked my supervisor to co-author with me for CV and post PhD opportunities.’ Similarly, other candidates appeared to recognise the value of being named alongside their supervisors. As one noted, their motivation was ‘to have the honour to publish with my name beside my prominent supervisor.’

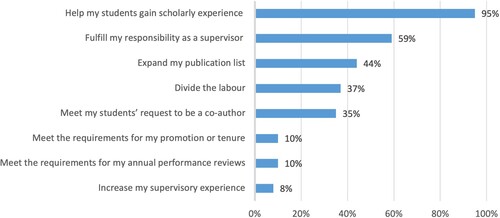

Although the process of co-authoring was often initiated by the supervisor (), in quite a few cases, as 35% of our supervisor respondents reported (), candidates asked their supervisors to co-author with them. Supervisors’ reasons for co-authoring with their candidates largely aligned with the rationale the students offered. For example, as shown in , almost all the supervisor respondents viewed co-authoring as contributing to the student’s academic and professional development, with 95% indicating that ‘helping my students gain scholarly experience’ was a motivating factor and 59% viewing co-authorship as a means to fulfilling their responsibility as a supervisor.

When asked to expand on these motivations (SS_Q13), many supervisors appeared to view co-authoring with their candidates as part of their role as supervisors and their responsibility to teach students how to write for publication. For example, one explained, ‘I see [co-authorship] as part of our mentoring role as senior researchers’ while another described how co-authoring helped build their students’ writing and thinking skills: ‘ … with the right checks and balances, it is an excellent way to help students improve their writing and thinking skills.’ One supervisor even equated co-authorship with supervision:

If I don’t collaborate with my student on a publication, there is very little to show for the time that I put into training the student how to do research … I wouldn’t be doing my job if I did not mentor the student on writing.

Other supervisors highlighted the value of co-authoring for building not only their students’ research track record but also their own. For example, one supervisor explained that they were motivated to co-author with students to ‘help the students get traction and track record’ and subsequently help ‘get my students a job’. Naturally, these papers also contribute to the supervisors’ research output. Almost half (44%) of the supervisors indicated that co-authoring with their doctoral students expanded their publication list. Despite this response rate, free-text responses appeared to indicate some discomfort with this motivation, with one explaining: ‘the phrase “expand my publication list” sounds mercenary, but I suppose that it is true.’

Reasons against co-authoring

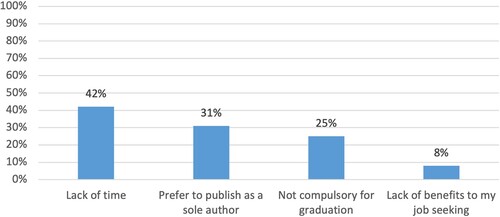

RQ2 investigates the reasons candidates and supervisors decide against co-authoring (CS_Q17 and SS_Q15). The primary reason cited was ‘lack of time’ (42%, see ). Notably, most of the candidates nominating ‘lack of time’ were enrolled full-time (70%), meaning their length of candidature was much shorter than that of part-time students; such candidates would be impacted more severely by long publishing timeframes.

Given the opportunity to elaborate on their reasons for not co-authoring, a few students pointed to the team coordination tasks required when co-authoring. For example, one recounted how they had struggled in the past with getting their supervisors to respond to emails ‘in a timely manner’ and how this impacted their ability ‘to establish a timeline for completion.’ Other candidates felt that the demands of co-authoring would be too onerous for their supervisors; their supervisors were ‘too busy working on [their] own projects, so [the candidates] wouldn’t ask’ and were ‘uncertain about taking [their supervisors’] time.’ 31% of the candidates indicated that their reason for not co-authoring was a preference ‘to publish as a sole author’. Apart from the listed options, 25% of the candidates stated in the open-text field that their supervisors had not raised co-authorship as a possibility.

Supervisors’ reasons for choosing not to co-author were also explored. Although the Supervisor Survey was limited to those who had experience co-authoring with their candidates, participants were asked if they had ever declined to co-author with a candidate (SS_Q14), and if so, what their reasons were (SS_Q15).

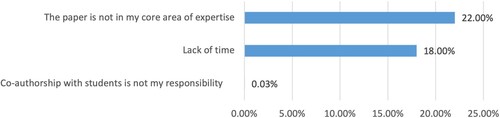

Only 51 of the 126 surveyed supervisors answered ‘Yes’ to SS_Q14. Notably, in addition to the responses outlined in , 29% of the supervisor participants indicated in the open-text field that they felt their contribution to the manuscript did not warrant publication. Elaborating on this response, several supervisors recounted experiences in which co-authorship seemed inappropriate, given the timing of the conversation or the level of contribution to the student’s work. For example, one suggested that they were asked to co-author after the doctoral student had done ‘the bulk of the work and [the supervisor] thought [the candidate] deserved sole authorship.’ Another recounted how a candidate offered to name them, but they declined, given that they ‘had not participated in any of the fieldwork that resulted in this paper.’ This supervisor explained that they ‘did not feel as if [they] had any ownership of any part of the work.’

In other responses, supervisors recalled situations in which they were involved in the study from an early stage but still found themselves not making a decision regarding co-authorship until the manuscript was complete. For instance, one supervisor interpreted their co-authorship collaboration as an ‘ex-post decision depending on the amount of my involvement.’ Another supervisor explained, ‘where my contribution is substantial, I raise the question of co-authorship.’ Explanations such as these suggest that the decision to co-author is somewhat reactive rather than carefully planned and proactively implemented.

The second most cited reason supervisors gave for not co-authoring was a view that the paper was not in the supervisor’s core area of expertise (22%). For example, one supervisor recalled a cross-disciplinary collaboration in which they declined to be named because of their ‘lack of experience in the field that paper was focused on.’ A further reason for supervisors’ disinclination was a lack of time (18%), aligning with the responses from the candidate participants. Clarifying what they meant by ‘lack of time’, one suggested that co-authoring with the candidate ‘is extremely time[-]consuming if done well’. Further, one recalled how their ‘student was extremely reluctant to write anything’ and noted a potential risk of misconduct: ‘I suspected that if I co-authored, he would simply expect me to write and would then use it in the thesis.’

Challenges in co-authoring

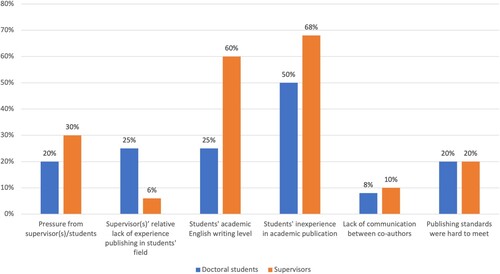

RQ3 explores the challenges that supervisors and candidates face in the actual practice of co-authorship. For the purpose of this question (CS_Q28 and SS_Q23), only those participants who had engaged in supervisor-candidate co-authorship were asked to respond (all 126 supervisors and 40 of the candidates). The most cited challenge, as noted by 50% of the candidates and 68% of the supervisors, was ‘students’ inexperience in academic publication' ().

Notably, amongst the supervisors, the second most commonly cited challenge (60%) was ‘students’ academic English writing level’. While the students did not commonly cite this challenge (only 25%), they did, however, frequently comment on their inexperience in publishing and the uncertainty around the process. For instance, one lamented how they were often unsure as to ‘what is good enough to publish’. Another explained that they would have liked their supervisor to mentor them through the publishing process:

I felt I could have received more guidance; it was a bit like ok off you go but I really didn’t know what I was doing.

Only a few supervisors offered further insight into the challenges they faced when co-authoring with their doctoral students. One noted that they ‘never placed [themselves] in a situation where these kinds of pressure would arise’; they would simply not co-author with a doctoral student who was either ‘not up to scratch’ or ‘would not take guidance as to required improvements’. implying that co-authoring with these sorts of students would be frustrating. Co-authoring only with suitable students may partly explain why 16% of the supervisors answered ‘none’ to the question about the challenges of co-authoring with doctoral students (SS_Q23).

Other factors influencing decision (not) to co-author: norms and ethics

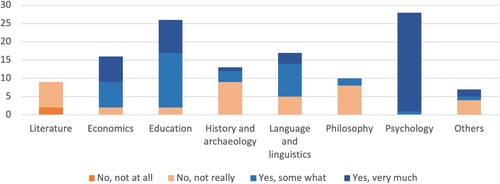

Apart from giving the above-mentioned reasons to co-author or not, in their open-field responses to these questions, several candidates and supervisors described how co-authorship simply came about or, in the case of some, why it did not come about. Of particular interest were references to disciplinary norms. For example, when answering SS_Q20 asking about supervisors’ experiences initiating co-authorship with the candidate, one supervisor working in History explained that co-authoring with candidates ‘is the expected norm in our discipline, so we don’t initiate. It just happens automatically.’ Such explanations reinforce the finding outlined in that 37% of students reported that co-authorship with a supervisor was expected in their field of study. Supervisors were questioned about disciplinary norms (SS_Q11), with 69% of them indicating that co-authorship was regarded as common in their disciplines. When these responses were linked to participants’ disciplines, some patterns emerged (): supervisors from Psychology stated that supervisor-candidate co-authorship was common in their field, while supervisors from Literature stated that co-authorship with a candidate was not common. At times, however, supervisors were in disagreement as to their disciplinary practices, as presents.

Figure 6. Supervisors’ views on whether co-authorship with a candidate is common in their disciplines

In addition to these conflicting perceptions of what was common, one of the most prevalent themes that emerged from the data was uncertainty around what constituted ‘co-authorship’. Specifically, participant responses to survey questions often indicated that they conflated ‘co-authorship’ with ‘gift co-authorship’. Candidates used words such as ‘assumed’, ‘assumption’, and ‘expected’ to express that adding the name of their supervisor(s) was taken for granted. For instance, one candidate explained, ‘if I publish at all as part of my PhD, my supervisors will be co-authors.’

Regarding other interpretations of co-authorship, many responses characterised their co-authoring practices as a division of labour, as one supervisor explained:

The major issue informing decisions about how and whether to share authorship with students in my field – as in all areas of experimental and theoretical linguistics – is division of labour and origin of ideas … It’s not a ‘cultural’ decision, rather a procedural issue informed by [the] university and broader guidelines about how to divide and allocate authorship on a project.

[I]f a publication does eventuate I ask the student to complete a form that states clearly the terms of engagement and the division of labour, and this is reviewed as required.

[W]e base authorship on a predetermined contribution points system. If my advisor meets the minimum points requirements, they are author[s] on the paper.

Discussion

What these findings reveal are the lenses through which doctoral students and supervisors in Australian HASS disciplines view co-authorship. In many cases, these perceptions are not explicit. In this section, we challenge some of the implicit perceptions and reconceptualise supervisor-candidate co-authorship.

Challenging implicit perceptions

Our findings revealed that candidates and supervisors hold implicit perceptions about co-authorship which lead to different approaches, including dividing labour, adhering to ethical requirements, conforming to disciplinary norms, and engaging in a pedagogical practice (answers to CS_Q16,17 and SS_Q11,13,15,20). Implicit perceptions can place unintended barriers to the practice of supervisor-candidate co-authorship, but in many cases, these barriers can be overcome by defining co-authorship as a collaboration.

In terms of the goals and benefits, we first suggest that by defining co-authorship as a collaborative practice, candidates’ apprenticeship in academia becomes foregrounded as a principal goal. While the research output remains the other principal goal, rather than viewing the process through a ‘divide and conquer’ lens, more attention is paid to scaffolding candidates to think, write, and publish as academics. Indeed, our findings indicate that while supervisors may recognise the pedagogical value of co-authorship, apprenticeship seems not to be perceived as a principal goal or driving motivation to co-author. In fact, many of the free-text comments speak more to the division of manuscript-writing labour or adherence to ethical protocols. However, if supervisors prioritised apprenticeship in co-authoring with candidates, their students could be more intentionally and effectively enculturated into academia (Lee & Kamler, Citation2008). Our findings support this view, as some of our supervisors, when asked about their motivation for co-authoring with a candidate (SS_Q13), suggested that such an arrangement improved candidates’ writing skills and enabled them to disseminate their findings to the wider discipline (Liardét & Thompson, Citation2022).

Responding to questions about the reasons for co-authoring (SS_Q13 and CS_Q16), several supervisors and candidates commented that they simply conformed to a disciplinary norm. We question the permanence and consensus of co-authoring disciplinary norms based on the responses reported in this study. Firstly, the claim that co-authoring is (not) and always/never will be practised in a particular discipline is debatable; as Leane et al. (Citation2019) found, practices in Literary Studies – a discipline traditionally dominated by sole-authored publications – have been steadily evolving over the last decade such that co-authorship is much more widely accepted (see also, Barney, Citation2023; Haddow et al., Citation2017 for discussion around increasing co-authorship in other HASS disciplines). Secondly, consensus over what is normative cannot be assumed; even in our modest sample, supervisors from the same discipline held divergent views on whether co-authorship between supervisors and students was normative. Our distrust of disciplinary norms aligns with House and Seeman’s (Citation2010) position that complete agreement on norms will never be achieved.

Regarding perceived risks and burdens of co-authoring, we contend that some can be avoided by up-front discussions between supervisors and candidates. First, we suggest that either the supervisor or the candidate initiate a discussion about co-authorship, which can prevent both parties from acting or refraining from acting on assumptions. Second, we contend that the deficiency of time obstacle is sometimes caused by ad hoc arrangements that could be averted by an up-front discussion, where the parties’ anticipated time commitment and expectations are declared and negotiated. Third, we contend that ethical issues can also be circumvented through up-front clarification of authorship allocation and duties.

A reconceptualisation of supervisor-candidate co-authorship

Reflecting on participants’ reported practices and the underlying assumptions they reveal, we surmise that the basis on which supervisors and candidates decline or engage in supervisor-candidate co-authorship lies in how they conceptualise the arrangement. This is not surprising, given that co-authorship can have numerous meanings (Ponomariov & Boardman, Citation2016). For example, as our survey responses, such as those to SS_Q13 and CS_Q16, revealed, when supervisors interpret co-authorship as an approach to doctoral pedagogy, they give priority to training candidates while co-authoring. In contrast, supervisors who perceive co-authorship merely as a normative or procedural step tend to pay more attention to getting the article published rather than focusing on the processes or means to this end. Such perceptions are not unreasonable because guidelines around authorship tend to be regulatory rather than presenting co-authorship as a site for mentorship and training.

To clear up this confusion, we propose a new way of conceiving co-authorship as that of ‘collaborative co-authorship’, or the joint preparation of a manuscript from concept development to publication. This reconceptualisation is intended to raise supervisors’ and candidates’ awareness of the pedagogical significance of supervisor-candidate co-authorship (Kamler & Thomson, Citation2014), over more procedural or compliance imperatives. Collaborative co-authorship involves modelling and jointly enacting the discourses for constructing knowledge valued in the disciplinary community. The reconceptualisation of supervisor-candidate co-authorship has implications at the individual level, in the interactions between supervisors and candidates; at the institutional level, where academics are inducted into supervisory practices; and at the national and more abstract macro levels, where policies are developed and mandated, and where cultural values and attitudes reside.

At the individual level, as mentioned above, collaborative co-authorship can be practised as a doctoral pedagogy that enculturates candidates into professional scholarly writing and the academic community (CS_Q16; SS_Q13), through engaging in recognised disciplinary discourses of knowledge construction (Leane et al., Citation2019). When considering whether to co-author, it is essential that supervisors and candidates discuss not only authorship allocation for the proposed paper, but exactly what they mean by co-authoring collaboratively, including their expectations of time, writing skill level, and effort that will be required from each party to succeed in publishing. Such discussions are intended to clarify expectations regarding roles, responsibilities, and workload of the co-authors, avoiding reliance on implicit assumptions of disciplinary or other ‘norms’ (Cardilini et al., Citation2021).

While we advocate collaborative co-authorship as a highly effective doctoral writing pedagogy, we do acknowledge that the practice may not be appropriate in every instance. Supervisors may choose not to co-author with certain students during candidature for a variety of reasons (SS_Q15). For instance, attempting to publish peer-reviewed journal articles during candidature may be counter-productive due to the nature or stage of a student’s research (e.g., no publishable results) and/or the developmental level of their thinking and writing; for these students, co-authoring too early runs the risk of a continued dependence on the supervisor to think and write for them. In such instances, aiming for publication after thesis submission may be more appropriate.

Furthermore, with increasing workloads and numbers of PhD candidates that academics are expected to supervise (Brownlow et al., Citation2023; Kumar & Wald, Citation2023), co-authoring several publications with each student may simply be unfeasible. To enable truly collaborative co-authorship, supervisors with several research students could limit the number of papers they collaboratively co-author with each student to one or two, which would still reap pedagogical benefits. Finally, doctoral students should be made aware of the risks in agreeing to co-author with supervisors and others in positions of power. Although our data did not reveal instances of misconduct such as coercion on the part of supervisors, this practice has been known to occur (NSW Ombudsman, Citation2017); we again emphasise the collaborative nature of the practice we are advocating, which minimises the risk of students being coerced to name supervisors or others as co-authors who have not contributed intellectually to the paper.

At the institutional level, we propose that collaborative co-authorship be presented as a framework for delivering effective doctoral support in every discipline, and that the practice be promoted, explicated, modelled, and discussed in supervisory training programmes. At the same time, as suggested above, creating conditions conducive to the practice of collaborative co-authorship may require a reconsideration of requirements placed on doctoral supervisors and students, for instance limiting the number of PhD students a supervisor assumes at one time and the number and journal ranking of published papers expected of candidates.

At the macro-level, as doctoral supervision is engrained in the political context of contemporary higher education policies, it is critical that national research policies, procedures, and guidelines acknowledge the pedagogical value of co-authorship, rather than simply managing its risks by imposing guidelines that ensure ethical practice. Ultimately, collaborative co-authorship embodies a vision of academia that resists the dominant metrics and performance culture; it is an opportunity for PhD supervisors to introduce their acolytes to the joys of academic publishing: engaging in scholarly practices, joining disciplinary communities and conversations, and disseminating new knowledge.

Conclusion

This study set out to investigate HASS supervisors’ and candidates’ perceptions towards supervisor-candidate co-authorship, outlining their rationale for co-authoring as well as their hesitations towards this practice. Overall, respondents recognised co-authorship for its contribution to candidates’ development as researchers. However, many showed reluctance towards the practice, raising concerns about ethical practice and the time involved. In addition, in some situations, the decision to co-author or not to co-author was simply based on normative perceptions. To respond to the misconceptions and lack of clarity around these practices, we argue that supervisor-candidate co-authorship needs more pedagogical awareness and propose a new term to this end. ‘Collaborative co-authorship’ highlights how the practice can be strategically employed as a pedagogical tool and not simply a means to a publication output.

We are aware that this study and its implications have limitations. We acknowledge our results are based on a relatively small sample size. Future investigations would benefit from a larger population that could account for demographic influences and their impact on participants’ decisions regarding co-authorship (e.g., country of enrolment, enrolment type, mode of thesis, etc.) as well as further investigation into these stakeholders’ actual practices. Second, students initiating and engaging in collaborative co-authorship may be very challenging in contexts where there are significant power differences in the doctoral supervision space and/or entrenched norms of gift, or even coerced, authorship. It is our hope that collaborative co-authorship can be considered, evaluated, employed, and adopted as a pedagogical approach in doctoral supervision to facilitate the enculturation of doctoral students into academia and further promote the dissemination of knowledge.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this article, ‘candidates’ is used interchangeably with ‘doctoral students’.

2 Given that some certain disciplines like Psychology can be regarded as a STEM discipline, one of the screening questions asked respondents whether they considered their discipline as HASS; only those who responded affirmatively would proceed with the survey.

3 Survey questions have been coded in this article for the reader’s reference. For example, the first question in the Candidate Survey is identified as CS_Q1, while the twentieth question in the Supervisor Survey is coded as SS_Q20.

4 Due to the anonymity of survey participants, quotes cannot be traced to any single individual and are simply reported with the pronoun ‘they’.

References

- Aitchison, C., Kamler, B., & Lee, A. (Eds.). (2010). Publishing pedagogies for the doctorate and beyond. Routledge.

- Anderson, T., & Okuda, T. (2019). Writing a manuscript-style dissertation in TESOL/applied linguistics. BC TEAL Journal, 4(1), 33–52.

- Barney, K. (2023). Co-authorship, collaboration and contestation in relation to Indigenous research. Australian Archaeology, 89(1), 73–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/03122417.2023.2190510

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brownlow, C., Eacersall, D. C., Martin, N., & Parsons-Smith, R. (2023). The higher degree research student experience in Australian universities: A systematic literature review. Higher Education Research & Development, 42(7), 1608–1623. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2023.2183939

- Cardilini, A. P., Risely, A., & Richardson, M. F. (2021). Supervising the PhD: Identifying common mismatches in expectations between candidate and supervisor to improve research training outcomes. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(3), 613–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1874887

- Carter, S., & Laurs, D. (Eds.). (2018). Developing research writing: A handbook for supervisors and advisors. Routledge.

- Florence, M. K., & Yore, L. D. (2004). Learning to write like a scientist: Coauthoring as an enculturation task. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41(6), 637–668. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20015

- Haddow, G., Xia, J., & Willson, M. (2017). Collaboration in the humanities, arts and social sciences in Australia. The Australian Universities’ Review, 59(1), 24–36.

- Henriksen, D. (2016). The rise in co-authorship in the social sciences (1980–2013). Scientometrics, 107(2), 455–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-1849-x

- Hodge, L., & Murphy, J. (2023). Write on! Cultivating social capital in a writing group for doctoral education and beyond. Educational Review, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2023.2184772

- House, M. C., & Seeman, J. I. (2010). Credit and authorship practices: Educational and environmental influences. Accountability in Research, 17(5), 223–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2010.512857

- Kamler, B., & Thomson, P. (2014). Helping doctoral students write: Pedagogies for supervision. Routledge.

- Kiley, M. (2011). Developments in research supervisor training: Causes and responses. Studies in Higher Education, 36(5), 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.594595

- Kumar, V., & Wald, N. (2023). Ambiguity and peripherality in doctoral co-supervision workload allocation. Higher Education Research & Development, 42(4), 860–873. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2022.2115984

- Leane, E., Fletcher, L., & Garg, S. (2019). Co-authorship trends in English literary studies, 1995–2015. Studies in Higher Education, 44(4), 786–798. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1405256

- Lee, A., & Kamler, B. (2008). Bringing pedagogy to doctoral publishing. Teaching in Higher Education, 13(5), 511–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510802334723

- Liardét, C. L., & Thompson, L. (2022). Monograph v. manuscript: Exploring the factors that influence English L1 and EAL candidates’ thesis-writing approach. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(2), 436–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1852394

- Lokhtina, I., Löfström, E., Cornér, S., & Castelló, M. (2022). In pursuit of sustainable co-authorship practices in doctoral supervision: Addressing the challenges of writing, authorial identity and integrity. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 59(1), 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2020.1799839

- Macfarlane, B. (2017). The ethics of multiple authorship: Power, performativity and the gift economy. Studies in Higher Education, 42(7), 1194–1210. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1085009

- Maher, M. A., Feldon, D. F., Timmerman, B. E., & Chao, J. (2014). Faculty perceptions of common challenges encountered by novice doctoral writers. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(4), 699–711. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.863850

- Mason, S. (2018). Publications in the doctoral thesis: Challenges for doctoral candidates, supervisors, examiners and administrators. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(6), 1231–1244. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1462307

- National Health and Medical Research Council. (2018). Australian code for the responsible conduct of research. NHMRC.

- NSW Ombudsman. (2017). Discussion Paper: Complaints about supervision of postgraduate students (Publication No. 978-1-925569-50-6).

- Ponomariov, B., & Boardman, C. (2016). What is co-authorship? Scientometrics, 109(3), 1939–1963. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-2127-7

- Wilkins, S., Hazzam, J., & Lean, J. (2021). Doctoral publishing as professional development for an academic career in higher education. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100459