ABSTRACT

Program-level assessment is a holistic approach for arranging assessments throughout a degree program that supports sequential development of discipline knowledge, transferable skills and career readiness. Currently, the modular arrangement of courses means that student learning is partial, limited to passing the assessment and compartmentalized into independent course learning outcomes. In effect, the current practices prevent students developing broader educational attributes that are essential for future employment opportunities. Interviews were conducted with 18 academics, Associate Deans and Program Directors, from seven Australian universities in the fields of dietetics, physiotherapy and science disciplines in order to develop a conceptual model to guide program-level assessment. The proposed conceptual model is designed to support academics’ assessment practices, enhance the quality of universities’ programs and provides students with a more coherent assessment experience.

Introduction

There is a need in Higher Education to ensure assessment has relevance to students’ learning and skill development. Teaching scholars around the world agree that assessment drives learning (Black & Wiliam, Citation2009; Boud, Citation1990; Carless, Citation2015; Masters, Citation2014), and assessment should be designed to support learning (Baird et al., Citation2017; Black & Wiliam, Citation1998; Carless, Citation2015; Masters, Citation2014; Weir, Citation2020). Globalization and neoliberalization have reshaped higher education, framing it as a financial investment and with students being seen as consumers not learners (Raaper, Citation2016; Stokes & Wright, Citation2012). When it comes to assessment, neoliberal influences tend to prioritize the alignment of graduate outcomes to market demands, economic growth and individual responsibility (Wald & Harland, Citation2019). This has resulted in employability becoming a key policy focus, serving the neoliberal agenda (Bridgstock, Citation2017; Kinash et al., Citation2018), guiding students to prioritize industry-relevant knowledge and skills (Al-Haija & Mahamid, Citation2021; Sá & Sabzalieva, Citation2017). This emphasis has detracted from the learners' deeper learning (Carless, Citation2015), as students concentrate more on meeting assessment requirements to enhancing their employability (Bridgstock, Citation2017; Kinash et al., Citation2018).

Assessments are expected to signify quality in learning and teaching as outlined in principles and propositions by the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (Citation2023, p. 2). Furthermore, the Australian Qualifications Framework (Citation2013, p. 76), ensures organizations can prove graduates can demonstrate knowledge, skills, and the application of these. The cumulative achievement of assessments is then used to ensure satisfactory completion of a course (subject or unit) and overall attainment of a qualification (program, degree or course). Consequently, assessment has become data driven for universities to determine if programs and activities have the intended impact on students and the institutions' reputation. In Australia, performance-based indicators are used to measure and allocate funds to higher education institutions that is dependent on the quality of learning and teaching. The process is meant to optimize students’ post-graduate employment status (Brown et al., Citation2021; Department of Education, Citation2019). The impetus is for universities to ensure that quality assessments support students’ learning so they can develop the knowledge and skills required to succeed in their future career.

Researchers agree quality assessment is essential to support students' learning, ideally throughout their program of study (Dijkstra et al., Citation2010; Ibarra-Sáiz et al., Citation2020; Killen, Citation2005; Medland, Citation2019; Palermo et al., Citation2017). A current challenge with assessment in higher education is the modular approach of courses and assessments, which leads to a disjointed assessment experience for students (Jessop & Tomas, Citation2017). Students often perceive assessment tasks as mere hurdles to overcome, rather than opportunities for learning and improvement (Eva et al., Citation2016), which may result in a surface-level approach to learning. This approach may constrain students’ ability to feed forward, make evaluative judgments on their performance, apply the learning to future assessments and their careers (Reimann et al., Citation2019; Tai et al., Citation2018). Lack of student engagement with assessment feedback (Winstone et al., Citation2017), passive practices in processing feedback (Carless et al., Citation2011) and lack of feedback literacy (Molloy et al., Citation2020) conspire to impede students’ own understanding of their strengths and weaknesses. There is a need to facilitate learning by staircasing assessment across a program that is not constrained by discipline knowledge but focuses on the broader employability skills ensuring they develop academic, citizenship and career competencies (Bennett, Citation2018; Brent, Citation2019; Hill et al., Citation2016). To address these challenges, it is suggested universities adopt a holistic approach to assessment that emphasizes higher-level skills, feedback engagement, and transferability of learning.

The holistic arrangement of assessment at the program level has been referred to in the literature as programmatic assessment (Dijkstra et al., Citation2010; van der Vleuten et al., Citation2012) and program focused assessment (Hartley & Whitfield, Citation2013; Whitfield & Hartley, Citation2019). Programmatic assessment describes the planned arrangement of assessments, vertically and horizontally, across a degree program to collect longitudinal data. The data regularly informs teachers and learners on progress and should enhance students’ learning (van der Vleuten et al., Citation2012). Whereas program-focused assessment seeks to concentrate on program learning outcomes (PLO) using an integrative assessment approach to support knowledge and skill acquisition (Hartley & Whitfield, Citation2013; Whitfield & Hartley, Citation2019). For this paper, ‘program-level assessment’ (PLA) describes a holistic approach, where the strategic placement of individual assessment items within a program sequentially develops knowledge and skills of learners (Charlton & Newsham-West, Citation2022).

Program-level assessment is underpinned by the principles of programmatic assessment and program-focused assessment, and aims to create a cohesive and purposeful assessment framework. The significance of PLA is it fosters self-directed learning, evaluative judgment (Hartley & Whitfield, Citation2013; Tai et al., Citation2018; van der Vleuten et al., Citation2012), and enables the student to see their achievement against the program learning outcomes (PLO). Despite a growing amount of evidence that supports the merit of programmatic assessment (Schut et al., Citation2021), it has not been widely adopted within higher education institutions. Whitfield and Hartley (Citation2019) suggested the lack of adoption of programmatic assessment was due to a poor understanding within higher education sectors. A recent assessment and associated learning and teaching policy analysis identified that ‘only a small number of universities across Australia have adopted programmatic assessment’ (Charlton et al., Citation2022, p. 1485). Consistent terminology, and clear delineation of roles and responsibilities is needed so academics and professional staff can interpret the policies to understand what PLA looks like, how to achieve it, and who is responsible (Charlton et al., Citation2022). A lack of clear policies defining and outlining programmatic assessment partly hinders the implementation of programmatic assessment in the Australian higher education sector.

It should also be noted that academics’ assessment literacy is often guided by their personal assessment experience, which they have developed through experience or tacit knowledge (Bearman et al., Citation2017; Goos & Hughes, Citation2010). Academics are familiar with and often defer to examinations as part of their practice, which has resulted in students still experiencing a ‘testing culture’, that focuses on teaching to the test. Consequently, learning ‘pattern and recall’ skills for exams has less intellectual rigor and relevance to their future careers. Increasing academics’ assessment literacy and understanding of PLA is crucial to overcome course-level planning and promote a more holistic approach to assessment design and delivery. Adoption of PLA requires a system that promotes a holistic approach to assessment, enhances assessment literacy, and fosters collaboration among academics to facilitate the implementation of programmatic assessment across the sector. To achieve this, we propose a model that supports academics and management to develop PLA and enhance students' holistic learning from their assessments.

Literature on programmatic assessment's implementation and success is limited. Hartley and Whitfield (Citation2013) introduced Programme Assessment Strategies, through presenting successful cases at the University of Bradford. For instance, in the School of Pharmacy, developmental portfolios enhanced student readiness for practice and improved performance in registration assessments (University of Bradford, Citation2012). Similarly, the University of Plymouth Peninsula Medical School's frequent low-stakes cumulative assessments resulted in highly career-ready graduates (University of Bradford, Citation2012). Teeside University School of Science and Engineering's focus on program learning outcomes enhanced student responsibility, integrated assessments, and fostered professional identity and employability skills (University of Bradford, Citation2012). These cases also boosted staff collaboration, reduced assessments, increased staff contact time, and boosted staff morale (University of Bradford, Citation2012). However, Australian examples are lacking.

Developing the conceptual model

The proposed model is underpinned by Constructivist Grounded Theory (CGT), coined by Charmaz (Citation2014), who chose the term constructivist to acknowledge the researcher’s perspective in constructing and interpreting data. CGT was developed from the origins of grounded theory developed by Glaser and Strauss (Citation1967). Grounded theory is a qualitative research method that uses sociological inquiry to identify patterns of experience to develop a general or abstract theory or model that is grounded in participants’ views (Bryant, Citation2014; Charmaz, Citation2014). The foundations of grounded theory require several criteria that include grab, fit, work, and modifiability (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). ‘Grab’ requires the model to be useful. ‘Fit’ requires the data to emerge from categories (or themes). The ‘work’ criteria infer the use of context-specific theory and, lastly, the ‘modifiability’ of the model requires evolution of the model as changes occur. The key criteria of grounded theory have relevance for the development of a model; however, CGT was preferred because the researcher’s position, privileges, perspective, and interactions (Charmaz, Citation2014) are taken into account in the research process, which includes data collection, analysis and any additional iterations (Bryant, Citation2014; Charmaz, Citation2014).

To facilitate program-level assessment, a conceptual model is proposed, informed from semi-structured interviews with 18 academics from 7 Australian universities in health and science disciplines. Purposive sampling was used to recruit Associate Deans or Program Directors as the nature of their work requires interpreting learning and teaching policy, industry standards and overseeing degree programs. Snowball sampling, through collegial recommendations, was used as there was difficulty accessing the required participants without some assistance (Naderifar et al., Citation2017). An approach was made via email to 65 in total: 60 academics (n=60) and professional staff (n=5). No response was received from 26 potential participants; 18 people agreed to participate and of those, 11 academics suggested other colleagues, but 9 declined as they were new to their role, and felt they were unable to contribute effectively, or their current workload hindered participation. Recruitment was conducted in accordance with the Australian code for ethical research conduct and approved by the university’s Human Subjects Research Ethics Committee (Ref No: 2020/635 HREC). Participants included academics from physiotherapy (n = 4), dietetics (n = 2), health (n = 2), science (n = 7) and biomedical science (n = 3) disciplines. The participants included 11 Program Directors and 7 Associate Deans.

Thematic analysis was conducted from the interview data using a three-stage process to identify codes, concepts, and categories (Hoda & Noble, Citation2017). The inductive codes were used to inform the themes (Hoda & Noble, Citation2017), instead of using deductive coding to avoid any bias (Sproule, Citation2010). Each code was represented by a key word that was assigned to a section of text (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2015; Hoda & Noble, Citation2017). The transcripts were coded manually to increase familiarity with the data and then coded using NVivo software (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2015). There were 162 codes assigned, which were then consolidated to eight manageable and meaningful concepts, grouped together in an Excel spreadsheet and then further reduced to four (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2015). Coding and categories were developed, and consensus gained within the research team. As coding occurred shortly after each interview, only 18 participants were included, as this number was deemed sufficient for the study being undertaken, as data saturation was reached with similar insights being reported by the participants.

The interviews identified key enablers as effective policies with clear administration processes, supportive management to guide the process and facilitate collaboration, and professional development (Charlton & Newsham-West, Citation2024).

Academic 10 stated ‘I think you've got to have really strong leadership from an education focused academic.’

Academic 11 said that ‘One of the enablers that we have people who had bought into the process by the fact that we made it transparent and who are willing to come along, and you know, be open minded about it.’

While, Academic 7 mentioned that: ‘The Graduate Certificate I think, has been another really good enabler for our staff to understand. Because as you know, academics come in with a PhD but not with teaching training, formal training.’

Academic 17 acknowledged that ‘if you've got a very prescriptive and restrictive assessment policy that doesn't see assessment, only sees assessment at a unit level and not as a course-based level that can be really restrictive.’

Academic 15 revealed ‘I think most of our assessment decisions are based around individual courses.’

Academic 18 shared ‘I think the challenges are time, adequate staffing so you can have all those processes in place if you’ve not got enough staff hours and everyone’s time poor and those things [program-planning] are less likely to happen.’

Key components of the model

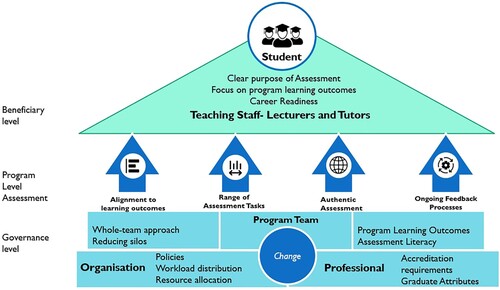

The primary purpose of the model is to enable PLA and enhance students’ learning experiences. Aligning assessments with the program's learning outcomes and employability skills makes them more meaningful and relevant to students, which is represented at the beneficiary level of the model. Additionally, the PLA components of the model provide teaching academics a holistic overview of the program's learning outcomes to enable clearer understanding of the progression and sequencing of assessments. Creating a well-defined assessment pathway that supports a range of authentic assessments, contributes to ongoing feedback practices and for students to develop evaluative judgements about their learning. Lastly, the governance level collates the organizational and professional factors that regulate the sector. This level aims to support the professional development of academic staff, develop assessment policy and support the operationalization of PLA ().

Beneficiary

The beneficiary level refers to students and teaching staff who are likely to benefit from the program-level assessment (PLA) planning approach (). The intent of the conceptual model is to drive learning through cohesive and clear pathways of purposeful assessment across a program, with the aim of enhancing students' experience of learning and developing key employability skills.

The purpose of assessment needs to be clear as students undertake their studies. The modular approach to their courses, often results in disconnection with assessments from one course to the next and the development of assessment skills such as writing and the ability to learn from their assessments (Hartley & Whitfield, Citation2013; Jessop & Tomas, Citation2017; Schuwirth & Van der Vleuten, Citation2011). The assessment journey needs to consist of purposefully arranged assessment that has horizontal and vertical alignment between the courses in the program of study. This approach supports self-directed learning, enables students to make evaluative judgements and apply feedforward strategies (Hartley & Whitfield, Citation2013; Tai et al., Citation2018; van der Vleuten et al., Citation2012).

Assessment that focuses on program learning outcomes instead of course learning outcomes would help students focus on sequentially developing their discipline knowledge and skills. Emphasis on PLO provides a holistic and integrative approach so that assessments support knowledge and skill acquisition (Hartley & Whitfield, Citation2013; Whitfield & Hartley, Citation2019). By focusing on the PLO, students could apply feedforward and make evaluative judgements (Tai et al., Citation2018) on their performance in their assessments.

Assessment focused on Career Readiness skills is another key component relevant to students learning from their assessments and developing a range of employable or transferrable ‘work ready’ skills (Medland, Citation2016; Panigrahi et al., Citation2015). The range of skills required includes written and oral communication, effective teamwork and conflict resolution, critical and innovative thinking and problem solving (Bridgstock, Citation2017). These only develop over time and from a wide range of experiences that develop knowledge (Bridgstock, Citation2016; Jorre de St Jorre & Oliver, Citation2018). Assessment also needs to include the moral and ethical employment of rapidly changing technologies, such as generative AI (Aoun, Citation2017; Bearman & Luckin, Citation2020).

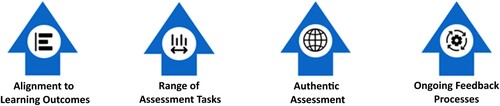

Program level assessment

This level refers to the four aspects that are integral for PLA (). Policies need to be developed to enable the program team to adopt the four assessment processes to facilitate program-level planning to suit each discipline context. Program-level assessment is assessment aimed at the sequential development of career skills (academic writing, critical and creative thinking, moral and ethical decision making etc) as opposed to the contextual job-specific gaining knowledge or skills. To achieve PLA the following are proposed.

Assessment alignment to learning program outcomes involves the constructive alignment of assessment tasks to program learning outcomes. This provides a holistic perspective (Hartley & Whitfield, Citation2013) and contextualizes the graduate attributes (Halibas et al., Citation2020). The aim is to help students develop discipline knowledge and skills to apply them in a range of context (Oliver & Jorre de St Jorre, Citation2018). The alignment supports students to transfer knowledge and humanistic skills to future professional and personal scenarios to enhance their career readiness.

A range of assessment types help assess the various course and program learning outcomes and provide a diverse cohort with an opportunity to succeed using their abilities to demonstrate knowledge and skill acquisition (Heeneman et al., Citation2021; Jessop & Tomas, Citation2017). The mapping of the assessment tasks would help to reduce duplication of assessment and support progressive learning during the program (Lawson, Citation2015) as well as master skills in increasing complexity and enhance their post-graduate career development.

Authentic assessments that mirror real-world scenarios can provide a clearer purpose between the assessment and students’ learning. Students are more likely to engage in their learning when assessment tasks have real-world relevance (Lizzio & Wilson, Citation2013; McArthur, Citation2022). A holistic approach to authentic assessments will also provide the professional context, facilitating the acquisition of humanistic skills required to succeed in the workplace, contribute to a better society and achieve career success.

Ongoing feedback processes are essential to inform students of their performance and to understand what they did well, what needs improving and how to improve for the next assessment item in the program of assessment (Ramaprasad, Citation1983; Sadler, Citation1989; Weir, Citation2020). Exposing students to a range of regular assessment methods helps facilitate the sequential application of knowledge and skills, facilitating the feedback spiral processes (Carless, Citation2019). Where feedback from one assessment task is transferable to future and similar task types help students make evaluative judgements to transfer skills (Carless, Citation2019; Tai et al., Citation2018) and learn from their assessment experiences.

Governance level

As posited in the introduction section of this paper the need for change, so that the organization and professional accreditation requirements enable the program team to operate using a whole of team approach ().

Program team

The whole team approach and reducing silos is necessary to enable a PLA approach. The team needs to include relevant stakeholders who are instrumental in program design, implementation, administration and technical support. The aim is to foster a shared responsibility and expertise across the program through the collegial networks to create a unified program that develops quality assessment practices (Bearman et al., Citation2016; Gordon & Smith, Citation2021; Goss, Citation2022; Newell & Bain, Citation2020; Simper et al., Citation2021). The aim of PLA is to acknowledge the top-down influences but provide the program team the bottom-up opportunity to enact a holistic vision for the assessments across their program.

Program learning outcomes and assessment literacy support the program team to ensure academics and professional staff have the skills required to successfully implement a holistic approach to assessments across their program. Backward mapping developed by Wiggins and McTighe (Citation2005) would encourage PLO to identify what students need to achieve at the end of the program and to ensure students learn these skills and knowledge from their assessments at the beginning of the program. This would help students identify a clear purpose to their assessments (Hartley & Whitfield, Citation2013; Whitfield & Hartley, Citation2019). Appropriate professional development is essential and would need to be conducted to support academics’ assessment literacy and the shift to PLA (van der Vleuten et al., Citation2012). Facilitating an understanding of PLO and improving their assessment literacy ensures the program teams have the skills required to successfully implement a holistic approach to program-level assessment.

Organizational and professional aspects

Policies underpin any academic's practice to guide what they can and cannot do. Policies need to be hortatory with the key terms clearly defined, explicate what PLA looks like and how to achieve it, while the roles and responsibilities are established (Charlton et al., Citation2022; Hammer et al., Citation2020; Mason & de la Harpe, Citation2020). To ensure clarity and a unified adoption of PLA it would be beneficial to have consistency in nomenclature within university policies across the sector (Charlton et al., Citation2022; Vahed et al., Citation2021). The development of clear and explicit policies to support PLA is needed to ensure the program-team can enact a program approach to assessments.

Workload distribution and allocation of resources are required to be managed effectively to implement PLA. Fundamentally the approach needs to be valued by upper management and in policies. By adopting the view that student learning occurs during their assessment experiences, a pivotal component of PLA is that assessment must be valued as a significant part of the teaching load. The financial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in significant restructuring (Hogan et al., Citation2021), where voluntary redundancies and job losses further impacted academic workloads which had already been identified by academics as a challenge when performing current tasks required in their role (Goos & Hughes, Citation2010; Gordon & Smith, Citation2021; Vahed et al., Citation2021). An investment in the teaching workforce, an emphasis on whole team program collaboration and the allocation of time for academics to devote to assessment mapping, moderation, evaluation, and improvement across the program PLA is needed.

Aligning to industry and accreditation requirements demonstrate expected core competencies or entrustable professional activities the students need to demonstrate to be qualified and registered as a professional in their chosen career (Perera et al., Citation2017). On top of this, alignment to graduate attributes provides a connection between universities and industry to demonstrate graduates' job readiness (Hill et al., Citation2016). Industry and accreditation requirements are an integral part of many professionally affiliated programs. In this situation, the program team can use the accreditation requirements in their assessments across the program to engage students in authentic learning toward their future careers.

Alignment to graduate attributes is included in each Australian university. These specify the desired skills, knowledge, and abilities their graduates would possess beyond the discipline context, across their career (Barrie, Citation2004; Hammer et al., Citation2020; Wald & Harland, Citation2019). The graduate attributes intend to develop students’ employability and transferrable skills (Bridgstock, Citation2016; Brown et al., Citation2021; Hammer et al., Citation2020; Kensington-Miller et al., Citation2018). Policies often require PLO to be aligned to the graduate attributes (Charlton et al., Citation2022), which helps contextualize the knowledge and skills required for each program. Planning assessment at the program-level acknowledges the top-down policy influence of graduate attributes and professional accreditation which seeks to support the program team to deliver a quality program of assessment, so students possess desired graduate attributes to enhance their career readiness and contribute meaningfully to society.

The purpose of this concept model is to visually represent and communicate the key concepts and components of a PLA ecosystem. It is an abstract and simplified representation designed to help stakeholders, such as educational designers, administrative staff, academics and management, to understand the overall structure, functionality, and relationships within the institution to enable the adoption of PLA. By establishing a well-designed assessment process, programs can gain valuable insights into their performance, effectiveness, and impact. It enables evidence-based decision-making, supported by policy and an educational assessment team that supports whole of program assessment and in turn improves the student learning and assessment experience. It also facilitates accountability with all stakeholders, academics, policy makers, practicing managers and administrators of universities and students.

This conceptual model is aimed at the practicing managers and administrators of universities, and decision makers in government level, giving them a framework and background to examine current and emerging policy directions to overcome the identified barriers and hurdles to the adoption of PLA (). It is also targeted at the education designers and key academics by giving them a conceptual model to develop teams to re-focus assessment and include assessment aligned to program learning outcomes. Thus, the model intends to prepare graduates with the ability to develop knowledge and humanistic skills from their assessments. The onus is on universities to help prepare graduates to develop the future career skills required and seeing the purpose of assessment as greater than a hurdle task on their way to graduation ( and ).

Table 1. Proposed barriers to be overcome to enable program-level assessment.

Limitations of the model

One of the limitations of the conceptual model is that it has not been tested. This research sought to identify what components would be included in a conceptual model to facilitate PLA planning. This model has been conducted as part of a doctoral research, which will require further testing for implementation. The mechanics of each component will need to be co-designed with the individual stakeholders to ensure the successful adoption and sustainability of the changes required for the program team suit the context.

Another consideration of the conceptual model is that the terminology may be unfamiliar due to different nomenclature at other higher education institutions. The model can be modified to suit the terminology relevant to the university, as expected in CGT, where the model can evolve through a process of continual change or suit a different context (Bryant, Citation2014; Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). Similarly, the research was conducted within Australia to suit their higher education context. However, globally higher education institutions are under pressure to ensure quality within the sector and government initiatives and expectations (Al-Haija & Mahamid, Citation2021; Sá & Sabzalieva, Citation2017; Whitfield & Hartley, Citation2019). The backward mapping design provides a practical strategy to identify the program learning outcomes so that the discipline specific knowledge and skills are developed sequentially throughout the program (Wiggins & McTighe, Citation2005). In the evolving AI technological landscape, the focus on PLO could determine how the humanistic skills are prioritized to help students develop the critical, creative and ethical thinking to adapt to the future world of work. More research is required in this changing technological landscape.

The conceptual model was informed from participants in health and science disciplines, specifically dietetics, physiotherapy, science, and biomedical science. Future research could focus on the practical implementation of the conceptual model to test its utility in the higher education sector across a range of disciplines. This would provide an opportunity to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the model and research the extent the model was able to facilitate and support PLA planning.

Conclusion

Current research identifies the benefits of programmatic assessment, program-focused and program-level assessment planning. The higher education sector is focused on ensuring quality standards are maintained in compliance with Australian federal government policy and performance-based funding requirements. The adoption of PLA is proposed to alleviate issues that students have with learning from their assessment and to encourage students to be self-directed learners and make evaluative judgments. The development of a conceptual model aims to guide faculties and academics to embrace the PLA approach. University leaders and policy makers need to ensure teaching and learning is valued at the institutional level and through policy. What is needed is a supportive environment and collaborative culture to facilitate PLA implementation and maintenance. The program-level planning approach encourages efficiencies in the long term for academics as students would be familiar with the discipline specific assessment methods and would not need explanations of how to undertake the task.

Currently, the modular approach pervades academics’ practice. Policy change is required to ensure the PLA encourages the transferability of knowledge and skills to future assessments, develop career readiness and attainment of post-graduate employment means a more holistic approach is necessary. University policies outline graduate attributes that indicate the desired qualities graduates will possess, and further clarity is required to provide context to program learning outcomes to better enable academics to support students’ holistic development of knowledge and humanistic skills required for their future career. Management and policies need to enable the whole-team approach to work collaboratively, reduce silos and have a collective assessment literacy to enact program-level assessment. The conceptual model aims to guide the implementation of the program-level assessment and could be used to evaluate the effectiveness of its application.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Al-Haija, Y. A., & Mahamid, H. (2021). Trends in higher education under neoliberalism: Between traditional education and the culture of globalization. Educational Research and Reviews, 16(2), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2020.4101

- Aoun, J. E. (2017). Robot-proof: Higher education in the age of artificial intelligence. MIT Press.

- Australian Qualifications Framework. (2013). Australian qualificiations framework. https://www.aqf.edu.au/framework/australian-qualifications-framework.

- Baird, J.-A., Andrich, D., Hopfenbeck, T. N., & Stobart, G. (2017). Assessment and learning: Fields apart? Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 24(3), 317–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594x.2017.1319337

- Barrie, S. C. (2004). A research-based approach to generic graduate attributes policy. Higher Education Research & Development, 23(3), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436042000235391

- Bearman, M., Dawson, P., Bennett, S., Hall, M., Molloy, E., Boud, D., & Joughin, G. (2017). How university teachers design assessments: A cross-disciplinary study. Higher Education, 74(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0027-7

- Bearman, M., Dawson, P., Boud, D., Bennett, S., Hall, M., & Molloy, E. (2016). Support for assessment practice: Developing the assessment design decisions framework. Teaching in Higher Education, 21(5), 545–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2016.1160217

- Bearman, M., & Luckin, R. (2020). Preparing university assessment for a world with AI: Tasks for human intelligence. In M. Bearman, P. Dawson, R. Ajjawi, J. Tai, & D. Boud (Eds.), Re-imagining university assessment in a digital world (pp. 49–63). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41956-1_5

- Bennett, D. (2018). Graduate employability and higher education: Past, present and future. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 5, 31–61. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/58871069/Bennett_D_2019_Graduate_employability_and_higher_education_Past_present_and_future_HERDSA_Review_of_Higher_Education20190411-64903-m85xb-libre.pdf?1555107568=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%.

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 7–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969595980050102

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5

- Boud, D. (1990). Assessment and the promotion of academic values. Studies in Higher Education, 15(1), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079012331377621

- Brent, G. (2019). Creating order from (potential) chaos: Embedding employability with the Griffith sciences plus program. In C. N. Allan, C. Campbell, & J. Crough (Eds.), Blended learning designs in STEM higher education: Putting learning first (pp. 99–119). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6982-7_6

- Bridgstock, R. S. (2016). Educating for digital futures: What the learning strategies of digital media professionals can teach higher education. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 53(3), 306–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2014.956779

- Bridgstock, R. S. (2017). Moving beyond ‘graduate employability’ to learning for life and work in a digital world. Future capable. http://www.futurecapable.com/.

- Brown, J. L., Hammer, S. J., Perera, H. N., & McIlveen, P. (2021). Relations between graduates’ learning experiences and employment outcomes: A cautionary note for institutional performance indicators. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 22(1), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-021-09477-0

- Bryant, A. (2014). The grounded theory method. In P. Leavy (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of qualitative research (pp. 116–136). Oxford University Press.

- Carless, D. (2015). Excellence in university assessment. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315740621

- Carless, D. (2019). Feedback loops and the longer-term: Towards feedback spirals. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(5), 705–714. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1531108

- Carless, D., Salter, D., Yang, M., & Lam, J. (2011). Developing sustainable feedback practices. Studies in Higher Education, 36(4), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075071003642449

- Charlton, N., & Newsham-West, R. (2022). Program-level assessment planning in Australia: The considerations and practices of university academics. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 48(5), 820–833. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2022.2134553

- Charlton, N., & Newsham-West, R. (2024). Enablers and barriers to program-level assessment planning. Higher Education Research & Development, 43(5), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2024.2307933

- Charlton, N., Weir, K., & Newsham-West, R. (2022). Assessment planning at the program-level: A higher education policy review in Australia. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47(8), 1475–1488. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2022.2061911

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. L. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). SAGE.

- Department of Education, Skills and Employment. (2019). Performance-based funding for the Commonwealth grant scheme. Australian Government. https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-reviews-and-consultations/resources/final-report-performance-based-funding-commonwealth-grant-scheme.

- Dijkstra, J., Van der Vleuten, C. P., & Schuwirth, L. W. (2010). A new framework for designing programmes of assessment. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 15(3), 379–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-009-9205-z

- Eva, K. W., Bordage, G., Campbell, C., Galbraith, R., Ginsburg, S., Holmboe, E., & Regehr, G. (2016). Towards a program of assessment for health professionals: From training into practice. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 21(4), 897–913. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-015-9653-6

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Sociology Press.

- Goos, M., & Hughes, C. (2010). An investigation of the confidence levels of course/subject coordinators in undertaking aspects of their assessment responsibilities. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(3), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930903221477

- Gordon, S., & Smith, E. (2021). Who are faculty assessment leaders? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.1983518

- Goss, H. (2022). Student learning outcomes assessment in higher education and in academic libraries: A review of the literature. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 48, 102485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102485

- Halibas, A. S., Mehtab, S., Al-Attili, A., Alo, B., Cordova, R., & Cruz, M. E. L. T. (2020). A thematic analysis of the quality audit reports in developing a framework for assessing the achievement of the graduate attributes. International Journal of Educational Management, 34(5), 917–935. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijem-07-2019-0251

- Hammer, S., Ayriss, P., & McCubbin, A. (2020). Style or substance: How Australian universities contextualise their graduate attributes for the curriculum quality space. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(3), 508–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1761304

- Hartley, P., & Whitfield, R. (2013). Programme assessment strategies (PASS) evaluation report. Oxford Brookes University. https://www.brad.ac.uk/pass/about/PASS_evaluation_final_report.pdf.

- Heeneman, S., de Jong, L. H., Dawson, L. J., Wilkinson, T. J., Ryan, A., Tait, G. R., Rice, N., Torre, D., Freeman, A., & van der Vleuten, C. P. (2021). Ottawa 2020 consensus statement for programmatic assessment 2: Implementation and practice. Medical Teacher, 43(10), 1139–1148. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2021.1957088

- Hill, J., Walkington, H., & France, D. (2016). Graduate attributes: Implications for higher education practice and policy. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 40(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2016.1154932

- Hoda, R., & Noble, J. (2017). Becoming agile a grounded theory of agile transitions in practice [Paper presentation]. IEEE/ACM 39th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE) Buenos Aires, Argentina, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSE.2017.21

- Hogan, O., Charles, M. B., & Kortt, M. A. (2021). Business education in Australia: COVID-19 and beyond. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 43(6), 559–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2021.1926616

- Ibarra-Sáiz, M. S., Rodríguez-Gómez, G., & Boud, D. (2020). The quality of assessment tasks as a determinant of learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(6), 943–955. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1828268

- Jessop, T., & Tomas, C. (2017). The implications of programme assessment patterns for student learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(6), 990–910. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2016.1217501

- Jorre de St Jorre, T., & Oliver, B. (2018). Want students to engage? Contextualise graduate learning outcomes and assess for employability. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1339183

- Kensington-Miller, B., Knewstubb, B., Longley, A., & Gilbert, A. (2018). From invisible to SEEN: A conceptual framework for identifying, developing and evidencing unassessed graduate attributes. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(7), 1439–1453. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1483903

- Killen, R. (2005). Programming and assessment for quality teaching and learning. Thomson Learning.

- Kinash, S., McGillivray, L., & Crane, L. (2018). Do university students, alumni, educators and employers link assessment and graduate employability? Higher Education Research & Development, 37(2), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1370439

- Lawson, R. (2015). Curriculum design for assuring learning - Leading the way -final report https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1541&context=asdpapers.

- Lizzio, A., & Wilson, K. (2013). First-year students’ appraisal of assessment tasks: Implications for efficacy, engagement and performance. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(4), 389–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2011.637156

- Mason, T., & de la Harpe, B. (2020). The state of play of associate deans, learning and teaching, in Australian universities, 30 years on. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(3), 532–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1685944

- Masters, G. N. (2014). Assessment: Getting to the essence. Australian Council for Educational Research. http://rd.acer.edu.au/article/getting-to-the-essence-of-assessment.

- McArthur, J. (2022). Rethinking authentic assessment: Work, well-being, and society. Higher Education, 85(1), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00822-y

- Medland, E. (2016). Assessment in higher education: Drivers, barriers and directions for change in the UK. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(1), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.982072

- Medland, E. (2019). I'm an assessment illiterate': Towards a shared discourse of assessment literacy for external examiners. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(4), 565–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1523363

- Molloy, E., Boud, D., & Henderson, M. (2020). Developing a learning-centred framework for feedback literacy. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(4), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1667955

- Naderifar, M., Goli, H., & Ghaljaie, F. (2017). Snowball sampling: A purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides in Development of Medical Education, 14(3), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.5812/sdme.67670

- Newell, C., & Bain, A. (2020). Academics’ perceptions of collaboration in higher education course design. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(4), 748–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1690431

- Oliver, B., & Jorre de St Jorre, T. (2018). Graduate attributes for 2020 and beyond: Recommendations for Australian higher education providers. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(4), 821–836. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1446415

- Palermo, C., Gibson, S. J., Dart, J., Whelan, K., & Hay, M. (2017). Programmatic assessment of competence in dietetics: A new frontier. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 117(2), 175–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2016.03.022

- Panigrahi, J., Das, B., & Tripathy, S. (2015). Paving the path from education to employment. Parikalpana: KIIT Journal of Management, 11(1), 113–119. https://doi.org/10.23862/kiit-parikalpana/2015/v11/i1/133121

- Perera, S., Babatunde, S. O., Pearson, J., & Ekundayo, D. (2017). Professional competency-based analysis of continuing tensions between education and training in higher education. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 7(1), 92–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-04-2016-0022

- Raaper, R. (2016). Academic perceptions of higher education assessment processes in neoliberal academia. Critical Studies in Education, 57(2), 175–190. http://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2015.1019901

- Ramaprasad, A. (1983). On the definition of feedback. Behavioral Science, 28(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830280103

- Reimann, N., Sadler, I., & Sambell, K. (2019). What’s in a word? Practices associated with ‘feedforward’ in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(8), 1279–1290. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1600655

- Sá, C. M., & Sabzalieva, E. (2017). The politics of the great brain race: Public policy and international student recruitment in Australia, Canada, England and the USA. Higher Education, 75(2), 231–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0133-1

- Sadler, D. R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science, 18(2), 119–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00117714

- Schut, S., Maggio, L. A., Heeneman, S., van Tartwijk, J., van der Vleuten, C., & Driessen, E. (2021). Where the rubber meets the road — An integrative review of programmatic assessment in health care professions education. Perspectives on Medical Education, 10(1), 6–13.

- Schuwirth, L. W., & Van der Vleuten, C. P. (2011). Programmatic assessment: From assessment of learning to assessment for learning. Medical Teacher, 33(6), 478–485. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.565828

- Simper, N., Maynard, N., & Mårtensson, K. (2021). Informal academic networks and the value of significant social interactions in supporting quality assessment practices. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(4), 1277–1293. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1896481

- Sproule, W. (2010). Content anaysis. In M. Walter (Ed.), Social research methods (2nd ed., pp. 323–350). Oxford University press.

- Stokes, A., & Wright, S.. (2012). The impact of a 'demand-driven' higher education policy in Australia. Journal of International Education Research, 8(4), 441–452. http://doi.org/10.19030/jier.v8i4

- Tai, J., Ajjawi, R., Boud, D., Dawson, P., & Panadero, E. (2018). Developing evaluative judgement: Enabling students to make decisions about the quality of work. Higher Education, 76(3), 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0220-3

- Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency. (2023). Assessment reform for the age of artificial intelligence. Retrieved October 3, 2023, from https://www.teqsa.gov.au/guides-resources/resources/corporate-publications/assessment-reform-age-artificial-intelligence

- University of Bradford. (2012). Programme Assessment Strategies (PASS). Retrieved September 17, 2022, from https://www.bradford.ac.uk/pass/

- Vahed, A., Walters, M. M., & Ross, A. H. A. (2021). Continuous assessment fit for purpose? Analysing the experiences of academics from a South African university of technology. Education Inquiry, 14(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2021.1994687

- van der Vleuten, C. P. M., Schuwirth, L. W. T., Driessen, E. W., Dijkstra, J., Tigelaar, D., Baartman, L. K., & van Tartwijk, J. (2012). A model for programmatic assessment fit for purpose. Medical Teacher, 34(3), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.652239

- Wald, N., & Harland, T. (2019). Graduate attributes frameworks or powerful knowledge? Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 41(4), 361–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2019.1613310

- Weir, K. (2020). Understanding rubrics. In P. Grainger & K. Weir (Eds.), Facilitating student learning and engagement in higher education through assessment rubrics (pp. 9–23). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Whitfield, R., & Hartley, P. (2019). Assessment strategy: Enhancement of student learning through a programme focus. In A. Diver (Ed.), Employability via higher education: Sustainability as scholarship (pp. 237–253). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26342-3_16

- Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. (2nd ed.). Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development.

- Winstone, N. E., Nash, R. A., Rowntree, J., & Parker, M. (2017). It'd be useful, but I wouldn't use it’: Barriers to university students’ feedback seeking and recipience. Studies in Higher Education, 42(11), 2026–2041. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1130032