ABSTRACT

There is growing evidence about the importance of establishing clarity around the ‘work readiness’ concept. A conceptual understanding of its meaning, structure, and components, as well as the essential characteristics for developing and assessing work readiness (WR), is not well established. This conceptual paper examines how WR can be articulated with greater clarity for furthering research in the field. It critically reviews the literature to provide comprehensive insights on its meaning, structure, and components around three questions: How is WR defined? What constitutes WR? And how can it be conceptualised? Graduate WR is theorised as a set of multi-dimensional constructs of cognitive and non-cognitive skills evolving in an environment driven by three approaches: demand-, equilibrium-, and supply-oriented, each guided by three types of definitions: organisational-, process- or outcome-based. The structure consists of WR skills organised hierarchically into three-order skill levels. This paper integrates WR components into a comprehensive three-dimensional conceptual model which researchers can use to construct their conceptualisations.

Introduction

There is a growing debate about the changing nature of work. Jobs that existed thirty years ago have evolved or no longer exist. Job markets need people with new characteristics to fit the changing workplace and a high-performance working environment (O'Neil et al., Citation2014). For greater chances of finding employment quickly, new university graduates must be equipped with work readiness (WR) skills in addition to subject-specific knowledge. However, a long-standing debate exists about the gap between employers’ requirements and graduates’ skills. The skills graduates learn at the university are expected to eventually translate into the desired workplace behaviour (Orr et al., Citation2023). Higher education (HE) institutions find themselves responsible for producing work-ready human capital (HC) (Tomlinson, Citation2017) and are often blamed for the skill gap debate (Cavanagh et al., Citation2015).

The dynamic labour market has increased interest in WR among other stakeholders (Winterton, Citation2019). Policymakers in countries like the United States (US), United Kingdom and Australia, amongst others, have extensively examined WR to inform their policy decisions on high-skilled HC development (Winterton, Citation2019). Equally important is the role of universities in providing graduates with the right skills (Winterton, Citation2019). The concept has been examined in different contexts, countries, and disciplines, giving rise to conceptual models and assessment tools to evaluate the preparedness of students for the workforce (Symonds & O'Sullivan, Citation2017).

Despite the interest in and the ongoing research on graduate WR, the struggle to bridge the skill gap between graduate skills supply and employer requirements continues in all countries. The difficulties could result from a lack of a well-defined structure allowing constructive assessment of graduates’ WR. It is worthwhile for economies to invest in establishing a WR framework that enables HE institutions to devise strategies for embedding WR skills in their curriculum. This can be achieved by identifying the skills of relevance to employers and their operations.

The lack of conceptual clarity and interchangeable use of WR with overlapping concepts such as employability are some of the researchers’ concerns. A myriad of terminologies, overlapping terms, and interrelated constructs make it challenging to define the concept (Caballero & Walker, Citation2010; Orr et al., Citation2023). The systematic review by Orr et al. (Citation2023) confirms this ambiguity and indicates that researchers conceptualise WR differently. While the lack of clarity is widely accepted, no research addresses this enduring problem. In this article, we undertake a systematic approach to deconstructing the concept of graduate WR. We describe the conceptual environment within which it sits to explain its definitions and structure by organising the skills domains to reflect what they are intended to measure. This paper responds to the call by Orr et al. (Citation2023) for a congruent conceptualisation to evaluate skill development. It presents the conceptual foundation of WR based on a demand-, equilibrium-, or supply-orientation, each guided by three types of definitions: organisational-, process- or outcome-based. It identifies a three-order hierarchical skill structure encompassing the components of WR and proposes a comprehensive three-dimensional conceptual model which researchers can use to construct their own conceptualisations.

Background

The last three decades have seen a growing importance of WR with policy initiatives to improve individuals’ WR and employability (Symonds & O'Sullivan, Citation2017). Employability is broader than WR as it encompasses the ability of an individual to ‘find, create and sustain meaningful work’ across their career and in different contexts (Bennett, Citation2020, p. 6) while they maintain a competitive edge by continuous enhancement of their skills, attitudes and attributes (Oliver, Citation2015). WR is a subset of employability and refers to an individual's perceived level of skills and attitude that define them as being prepared for success at work (Caballero et al., Citation2011). The effort to develop those desired skills among individuals impelled countries to align their policies for high-skilled HC development and education systems to integrate WR and related concepts (Symonds & O'Sullivan, Citation2017). Around 1985, the positioning of education as the key to economic success increased the pressure exerted on universities to produce more employable graduates (Winterton, Citation2019).

Regular use of the term in writing started in the 1960s and 1970s in vocational education and occupational training in US when the country was struggling with the issue of overeducation (Symonds & O'Sullivan, Citation2017). Then, the technology boom increased the demand for graduates, significantly increasing the employability gap in the 1990s (Winterton, Citation2019). This led to the Secretary’s Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills (SCANS) initiative, which identified five competencies characterising a competitive workforce (O'Neil et al., Citation2014). Concurrently, in Europe, the Lisbon strategy extended the scope of employability, focusing on improving the transition from ‘school to work’ for work-ready individuals (Winterton, Citation2019).

As more questions were raised on the worth of competencies at work, several reports addressed this issue; examples are the Finn Report in 1991 and the Mayer Report in 1992 (Sinclair, Citation2014). The reports sparked debate about ‘effective workplace’ participation and the competencies that it implies (Sinclair, Citation2014). Since then, several studies and reports have focused on the transition of graduates into the world of work, with the emergence of many terminologies addressing graduates’ readiness to join the workplace. The authors highlight the need to examine the concept with a close-up lens to clearly articulate the fundamental characteristics of the conceptual structure.

Having an adequate workforce is vital for every economy worldwide, and employer skills requirements are the factors shaping the labour market. Winterton (Citation2019), in his research looking at WR in the European, American, and Japanese contexts, explains that despite differences in geographic and socio-economic characteristics, institutional training structures and labour market regulatory mechanisms, employers’ skills needs are the common factor influencing WR skills in all three contexts. The WR concept results from employers’ demand for work ‘prepared’ or ‘ready’ graduates (Caballero & Walker, Citation2010), increasing WR's significance and the focus on employability skills development and learning. WR is also crucial for national governments to develop high-skilled HC for economic growth in response to globalisation (O'Neil et al., Citation2014). Thus, a clearer conceptual definition of graduate WR will prompt its integration into the university curricula for skill development after consultation between universities, employers and students (Cavanagh et al., Citation2015).

Next, we draw from models and approaches in the literature to explore the breadth of the concept. The deconstruction process helps circumscribe it from other related concepts and clarify its purpose, definition and structure.

Work readiness and related terminologies

Using mutually inclusive terms to refer to WR adds to the confusion around this concept. Multiple terms are used in the literature to refer to work readiness, such as ‘graduate skills’, ‘graduate attributes’ (Caballero & Walker, Citation2010), ‘graduateness’ (Tomlinson, Citation2017), ‘key competencies’ (Caballero & Walker, Citation2010), ‘graduate identity’ (Holmes, Citation2013), ‘employability’, ‘job-readiness’, ‘work preparedness’, ‘transferable skills’, and ‘generic attributes’ (O'Neil et al., Citation2014), ‘graduate pre-professional identity’ (Jackson, Citation2016) and ‘graduate capital’ (Tomlinson, Citation2017). According to Winterton and Turner (Citation2019), the conceptual misunderstandings that arise between employers and other stakeholders often stem from using different or overlapping terms. These terms are used interchangeably and often appear to share the same meaning or have subtle differences (Cavanagh et al., Citation2015). The interchangeable use of terms indicates the lack of consensus about the term, its components and how it should be taught (Orr et al., Citation2023).

The use of several terms to describe the concept of WR cannot be prevented. However, a suitable definition will describe and delimit the concept, explaining its congruity and distinctness from others. The definition acts as a compass, critical for clarity in addressing existing employment issues. We describe WR as existing in a conceptual environment, sharing collective aspects with other related terminologies rather than existing in isolation with its individual characteristics. However, defining the fundamental characteristics of WR will bring conciseness to the term and limit the use of interchangeable terms. Identifying the similarities and differences of neighbouring terms allows researchers to distinguish the common features that make them members of the same ‘family’ and the peculiar features that make them different.

Deconstructing work readiness

From the lens WR and related topics were examined in the literature, there is a consensus that employment-related concepts evolve within a bigger picture (Healy, Citation2023; Jackson & Bridgstock, Citation2021). As it does not occur in a vacuum, we undertake this deconstruction process holistically by relating it to the strategic environment within which it evolves.

Drawing on similar approaches to deconstructing employability (see Jackson & Bridgstock, Citation2021), we propose to first examine the concept of WR from a macro view regarding its economic contribution with the expectation of graduates bringing economic value and contributing to the organisation’s growth. Thus, from the macro perspective, WR is about meeting the requirements of the labour market system through a demand and supply system, or should we say that it is reduced to meeting employers’ demand.

The micro perspective values the teaching and learning process that shapes those individuals as future workforce while being careful not to misunderstand the purpose of the educational process as being to meet the demands of employers (Holmes, Citation2001). The process transforms individuals to show WR behaviour and potentially bridges the gap between demand and supply. However, we acknowledge that HE teaching and learning practices and HE systems are influenced by factors beyond its control (Jackson & Bridgstock, Citation2021).

The HE system prepares graduates for the workplace as an output of the teaching and learning system. However, it cannot be held fully responsible for the actual workplace behaviour of graduates. Instead, the individual is accountable for it, and we cannot circumvent that personal motivation and intrinsic and extrinsic factors influence WR behaviour. Healy's (Citation2023) career development and employability learning principles explain that this complex behaviour is due to the individual’s inherent characteristics and a set of economic, political, social, and cultural factors (Healy, Citation2023).

Better employment and skills development strategies can be devised holistically, allowing considerations for social and cultural capital and identity (Tomlinson, Citation2017). Our examination of WR within its strategic environment is similar, where we appreciate each stakeholder’s role in the system and their differing objectives for impelling WR.

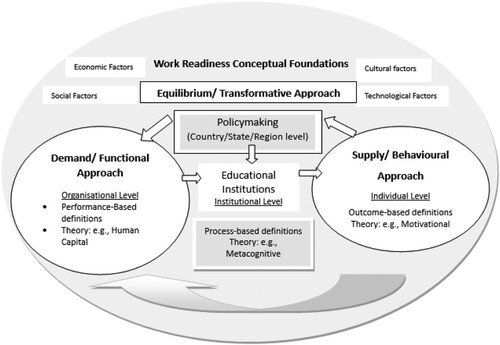

Contextualisation of the concept

A concept is defined by its context; the same principles apply to define WR. We propose relating the context to an underlying structure that connects researchers with relevant theories to organise and set their research framework. The underlying assumption of our model is that the relationship between graduate WR and its environment is dynamic and constantly subject to change and interactions with its components. We look at the concept from a demand-, equilibrium-, and supply- approach to explain how the context serves as a foundation for developing a conceptual model and to explain where the concept sits in a strategic environment (). WR is influenced by economic, social, cultural, and technological factors that guide policymaking in a country. This strategic environment has four actors taking an active role in skill demand, development and supply. The government has the role of developing policy measures for economic development and indirectly shaping the WR strategic environment. In implementing the policy measures, employers create the demand for WR skills. HE institutions find themselves responsible for aligning their programmes and curricula to support skill development. Individuals, as students or graduates, are the outcome of the skills development process, meant to satisfy HC needs. While we acknowledge that any individual in search of employment needs to demonstrate WR, for this paper, we define graduates as individuals who are exiting their undergraduate study programme and entering the workforce. We illustrate the role of the different actors in the strategic environment and their interaction with one another in .

The proposed three-pronged model looks at WR as being part of a larger system with three sub-systems (approach). The demand (from the labour market) and supply (work-ready graduates) approaches create change in one another to drive a larger system. In this model, we examine graduates exiting the university as the supply to the labour market. Given the system's complexity, we propose a third approach, the equilibrium approach, that brings substantial changes to the system through its ability to alter both the demand and supply side.

The development of high-skilled HC has an economic significance and demands investment. Rychen and Salganik's Holistic Model of Competency (Citation2003) looks at skills development from a demand-oriented perspective. We did not find literature proposing a similar approach to examine individuals as the product of this process or the characteristics of this supply to the labour market or any study investigating the process running in the background as an enabler to maintain the balance between demand and supply of skills. If there are, they have not clearly stated the grounding theory of their research from these perspectives. We are proposing a model to investigate WR from different lenses.

Demand/ functional approach

Drawing from Rychen and Salganik's Holistic Model of Competency (Citation2003), from a demand-oriented or functional approach, WR focuses on providing HC with the ability to work effectively using a set of cognitive and non-cognitive skills. A functional approach will extend further to characterise the level of skills, performance criteria and indicators of WR, defining the performance level expected by an employer. From a demand-driven approach, Verma et al. (Citation2019) used the ‘Resource Based View’ theory to conceptualise their ‘Work-readiness Integrated Competence’ model to explain the strategic importance of human resources as an internal source of competitive advantage for an organisation’s success. The workplace readiness skills set provides employers with well-prepared entry-level workers to contribute to organisational growth. Employers need the job to be done, and graduates need to be work-ready to perform their specific role pitched at a certain level and be consistent in their performance (Gardner & Liu, Citation1997). Graduates’ lack of understanding of employers’ complex requirements can lead to a consistent performance gap (Kapareliotis et al., Citation2019). Here, WR refers to the desired behaviour for effective performance at the workplace, which is derived from the employee’s cognitive/ intellectual abilities coupled with the right mix of behavioural and social skills.

Equilibrium/ transformative approach

The equilibrium/ transformative approach to WR considers the effect of factors that influence an individual’s ability to be work-ready. It is more sustainable and holistic in bringing the economic, societal and individual transformations to balance demand and supply. The primary concern here is graduates’ development of WR skills in a continuous and evolving process.

Okeke-Uzodike and Naude (Citation2018), in their study on the perceived WR of supply chain graduates, use the metacognitive theory to illustrate that learning involves the use of cognitive processes and the deliberate application of cognitive strategies to achieve goals and use the HC theory to explain the need for a competent workforce in a knowledge-based economy. From this perspective, WR is an overarching approach examining the process of producing high-skilled HC considering the economic, institutional, and socio-cultural factors that could be barriers to an individual’s ability to obtain a job (Jackson & Bridgstock, Citation2021).

Supply/ behavioural approach

The supply-side approach looks at graduates as an outcome of the process of delivering HC, an end product, to the labour market. The dynamic relationship between the graduate and the surrounding environment defines the latter's behaviour. From the behavioural approach, the individual’s ability and the factors that motivate the latter to satisfy the market demand or the employer’s needs translate into their WR behaviour. In other words, graduates put in the effort of displaying WR when motivated by some form of reward. They have their personal motivation besides the need to perform well for employers.

From what we conceive as a supply-driven approach, Kapareliotis et al. (Citation2019) look at how placements influence the WR of graduates. Here, WR is derived from the conceptual framework of consumer readiness in the marketing literature (Bowen, Citation1986). This is based on the organisational theory, which suggests that employees’ behaviour depends on how they understand what they are expected to perform and their ability to perform with the awareness of any reward or incentives to motivate the delivery of the expected performance (Vroom, Citation1982). Aligning with Vroom's (Citation1982) perspective, WR, in this approach, sees the employee as an asset shaped by role clarity, motivation and ability, with graduates needing to understand what their role constitutes in terms of knowledge and skills.

We have examined how the approach to WR can differ depending on the context. This knowledge and understanding help communicate WR in a more informed and effective way. In the following section, we examine definitions relative to the above approaches.

Definitions

Definitions are central to understanding a topic and communicating it effectively and efficiently. Theory is of value in explaining the meaning, nature and challenges in its context. Understanding how WR definitions are conceptualised and how they are used is important because of the lack of evidence of what defines WR (Caballero & Walker, Citation2010; Casner-Lotto & Barrington, Citation2006), the consequence of inconsistency in its articulation (Caballero & Walker, Citation2010) and the value perceived and attributed by stakeholders when referring to graduate capabilities and employability skills (Cavanagh et al., Citation2015). In this section, we unpack the generalised idea about WR and use an approach similar to Forrier and Sels (Citation2003) to examine the perspectives from which scholars define WR. Forrier and Sels (Citation2003) used Thijssen’s (Citation2000) classification of definitions as influencing factors to explain that context-related factors play an important role in determining graduate employability. In so doing, Forrier and Sels (Citation2003) demonstrated the differences in the scope of employability research studies. We are proposing a classification that allows researchers to define the scope and boundaries of their study using theories with three types of definitions: performance-, process- and outcome-based. This approach examines the concept in terms of its function and mechanism in bringing together a set of WR behaviours that add value to the context.

Performance-based definition

Performance-based definitions examine WR as the productivity and value brought to the work environment. This type of definition is usually related to HC theory.

WR appeared in the literature as ‘a selection criterion for predicting graduate potential’ (Casner-Lotto & Barrington, Citation2006; Gardner & Liu, Citation1997) from the employer’s or industry’s perspective. In order to achieve WR, graduate learners are expected to acquire task competence and demonstrate proficiency at the exit stage of university education and entry stage of graduate employment (O'Neil et al., Citation2014). Therefore, a work-ready employee possesses ‘a set of personal qualities, people skills and professional abilities’ identified as essential for employee success (Crespin et al., Citation2019, p. 1). It embodies a set of essential values, behaviours, and skills that facilitate an individual’s successful transition into the workplace (Tentama & Riskiyana, Citation2020), and it defines the condition or state in which the graduate is likely to find employment (Kapareliotis et al., Citation2019). All five definitions look at the concept from the demand side, that is, the expectations of employers about graduates’ performance in their organisation. The following two definitions are not specifically from the employers’ perspectives but from the stakeholder’s perspective in general. Jollands et al. (Citation2012) define WR as ‘a complex of generic attributes that allow graduates to apply their technical knowledge to problem identification and solving’ and that it is a valuable concept for assessing a graduate’s workforce transition. It is also defined as a criterion for measuring the suitability of an individual’s work quality in relation to workplace requirements and an indication of potential in terms of job performance and career progression (Tentama & Riskiyana, Citation2020).

The above definitions emphasise WR skills as the key determinant of good performance. According to the HC theory, highly skilled HC is considered a factor for good performance at work, which indicates to the employer the graduate’s ability to potentially bring growth to their organisation.

Process-based definition

The process-based approach takes into account the internal and external factors influencing WR, similar to the graduate identity in Holmes' (Citation2013) processual approach. It explains that an individual’s WR behaviour evolves within and through interaction with an ecosystem over a timescale. This approach incorporates context-related economic, social, cultural or technological factors that promote or inhibit an individual's WR over time. This aligns with the OECD’s definition of WR, ‘the right skills mix not only for the present but also for the future needs of dynamic labour markets’ (OECD, Citation2011, p. 11), where the labour market is the environment influencing WR behaviour over time. Also, Tentama and Riskiyana (Citation2020) refer to WR as the extent to which an individual possesses the knowledge and skills to work independently and the ability to adjust to cultural demands by bridging work-oriented learning and labour market workforce requirements. Definitions under this type suggest that WR behaviour does not occur independently but is instead influenced by a set of interrelated factors (see Healy, Citation2023).

From a broader lens, the macro-environment has a set of conditions or factors that either favour or interfere with WR behaviour at an individual level. Individuals are often unable to control these conditions, but their impact can be mitigated with appropriate measures at the institutional level.

Outcome-based definitions

The outcome-based definition revolves around an individual’s motivation to do well by preparing for the work environment. The definition relates to how the potential outcome of demonstrating a work-ready behaviour motivates an individual towards good performance or success at work. It is linked with the individual’s expectation of gaining some advantage, which can be related to the motivational theory. It also informs about an individual’s attitudes, skills, and knowledge for success in the workplace (Tentama & Riskiyana, Citation2020).

According to Caballero et al. (Citation2011, p. 42), work-readiness can be defined as ‘the extent to which graduates are perceived to possess the attitudes and attributes that make them prepared or ready for success in the work environment’, which is the most widely accepted definition. WR is also a set of competencies encompassing career motivation, basic skills, job-specific skills, higher-order thinking skills, social skills, and personal characteristics and attitudes (Symonds & O'Sullivan, Citation2017). The definitions are all-encompassing and refer to what is perceived as being the individual’s level of skills in a particular context, with the potential for this behaviour to change in a different context.

Mostly, researchers examine WR from the employers’ perspective and sparsely from the graduate students’ perceptions (Cavanagh et al., Citation2015). Despite being the supplier of a high-skilled workforce to the industry and the economy, a definition from HE institutions’ perspective acknowledging that graduate WR behaviour evolves in an environment guided by intrinsic (individual learners) and extrinsic (environmental) factors could not be found.

This section looks at definitions of WR and how it relates to contexts. We also unpack the different aspects or dimensions that make up the WR concept. The next section will look at the structure of WR and its components.

Structure of work readiness

The backbone of WR relies on the organisation of skills that promote WR behaviour. Orr et al. (Citation2023) found that WR is described as discipline-specific and generic skills from a multidimensional perspective. The studies generally comprised a combination of four factors: perception of personal characteristics, awareness of one’s workplace protocol, overall competence and ability to adapt and interact in work situations. These elements are the thematically derived four-factor model of Caballero et al. (Citation2011), developed in the early stages of the concept development (Orr et al., Citation2023). In this section, we explain how Caballero and colleagues’ existing model can be integrated into a broader theoretical model to present a more coherent structure of WR. Building on the existing model, we foresee the new structure to overcome the lack of consistency in WR conceptualisation (Orr et al., Citation2023). Combined with an underlying theory, the proposed structure will allow researchers to propose ‘more refined, accurate, and comprehensive definitions of their constructs’ (Shaw, Citation2017, p. 821).

A complex structure

The structure of the concept became more complex as it evolved with time, and as the structure grew, the abstractions also increased. With the structure responding dynamically to its environment, modelling it becomes challenging. Nevertheless, a set of core and context-specific skills is interrelated within an environment. By core skills, we refer to the skills that remain constant across different contexts and are, therefore, not completely dependent on environmental factors. Context-specific skills, on the other hand, are dependent on the characteristics of the context. The structural complexity is due to the multi-dimensional nature of the construct. Next, we explain how the components can be organised to show their interrelationships and boundaries.

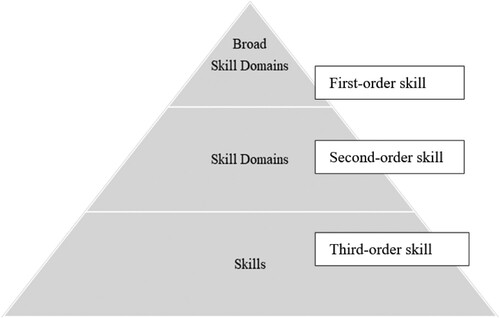

Our generalised idea about the structure of the WR concept is that the components consist of a set of skills at different order levels. We describe them as groups of skills arranged hierarchically to form clusters of related skills and groups of related clusters of skills. We use the skill map of Hilton and Pellegrino (Citation2013) as the backbone structure of the concept of WR to explain this hierarchy of skills. Their skill map organises a person’s thinking and behaviour into skills that are important for human development and learning into three broad domains: cognitive, intrapersonal, and interpersonal. We illustrate how each construct breaks down into a hierarchy of skills, as shown in .

Using the overarching hierarchical structure, we break down the three broad domains into skill domains, and skills, to give an indication of what each constitutes and which we refer to as first-, second- and third-order skills. The third-order skills are the low-order level skills, which are indicators of WR. A set of related third-order level skills interact to produce an additive effect that translates into a more complex behaviour, which we describe as the second-order level WR skill or the skill domain. The second-order levels are grouped logically according to range and types to constitute a higher-order class of behaviour or first-order level skills, which we mapped onto Hilton and Pellegrino’s three broad human thinking and behaviour domains. In the next section, we illustrate this hierarchical structure using the four-factor model of Caballero et al. (Citation2011).

Work readiness skills domains

Using our hierarchical structure, we illustrate how the four-factor model of Caballero et al. (Citation2011), which is most commonly cited as shown in , could possibly be grouped under the broad skill domains. By transposing them onto Hilton and Pellegrino’s Map, the corresponding domains of the four factors, which we refer to here as skill domains, are as follows: cognitive- work competence, interpersonal skills- personal characteristics, intrapersonal skills- social intelligence and organisational acumen. This mapping process and the definitions of the three broad domains provided by Hilton and Pellegrino (Citation2013) indicate their composition. However, the authors believe that defining the skills domains and skills under each would bring conciseness and make the conceptual definition more useful (see ).

Table 1. Mapping Caballero et al.’s four-factor model onto Pellegrino & Hilton skill map.

To summarise, researchers generally agree on the lack of theoretical clarity reflected by the abstract structure and its components. While we appreciate the comprehensive list of skills that measure WR and the various ways they are categorised, we believe in defining the building blocks of WR to make the structure clearer and more specific. The WR structure must set the foundation for how human thinking and related abilities (cognitive component), attitudes and human behaviour (behavioural component) translate into skills that provide the benchmark for good performance at work. The skill map of Pellegrino and Hilton is convenient for mapping skill domains onto a structure encompassing cognitive and non-cognitive skills. The three broad domains, cognitive, interpersonal, and intrapersonal skills are the three building blocks that constitute the structure.

The domains need definitive labels and definitions so that efforts to explain the importance of graduates developing those skills do not remain elusive. Drawing from existing theory and research, we endeavour to clearly and concretely define the concept, its structure, and domains to lay a sound conceptual foundation.

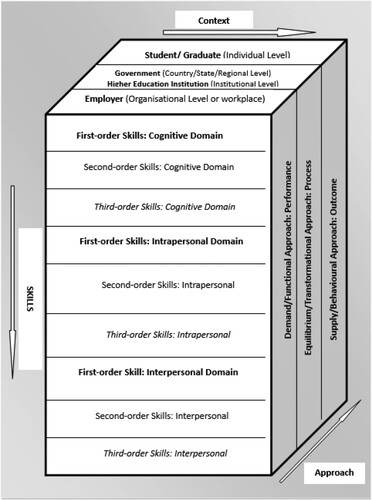

Work readiness: a three-dimensional model

To facilitate a more in-depth investigation of WR, we have discussed how WR skills development operates in a very dynamic strategic environment and the role of various key players. We are proposing a model () that integrates the three components: skills, context and approach. This more coherent conceptual model is grounded in a contextual base that guides the examination of WR through different lenses. It assists in identifying relevant theories to answer research questions, identify relevant data sources and design suitable instruments for a study. The model on its own is not intended for developing a curriculum; rather, it guides research on what could constitute the curriculum content for WR.

The conceptual model’s first dimension depicts the ‘what’ aspects of WR. Three distinct levels reflect three domains, each organised into three levels to facilitate categorisation, with the first order being the most complex and abstract and the third order being the simplest form. For example, if first order refers to cognitive skills, creative skills as an example of cognitive skills will fall under second-order (Hilton & Pellegrino, Citation2013), and inquisitiveness, as a personality trait of creativity (Martins & Terblanche, Citation2003), will be categorised as third-order skills.

The second dimension refers to ‘what’ context is involved, distinguishing between four macro-level contexts: employer, government, institutional, and student and graduate level. The employer level is the focus of organisational management and, therefore, is referred to as the organisational level. It includes different types of business activity depending on size, field, and sector of operation. HE is categorised as institutional and includes public and private entities, while the government level is divided into country, state and regional levels. By grouping HE institutions and government together, we imply that they have oversight of skill learning and development processes to meet and balance the demand and supply side. The third level refers to the student or graduate level for probing the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics at the individual level that prompt WR behaviours.

The focus of the third dimension is from ‘what’ perspective should the conceptual framework be defined for the findings to bring value to the stakeholder under study. First, from a demand or functional approach, WR indicates performance and refers to satisfying the labour market demand and, therefore, employers. Second, we propose an equilibrium or transformative approach, whereby WR is examined as a skill learning and development process, which is of interest to the government as policymakers and HE institutions. The third level is the supply/ behavioural approach, which looks at WR from a more individualist lens, probing more deeply into university student or graduate behaviours.

Future studies

The clarity of a concept depends on how well it is defined. While we have proposed a way to organise the concept for greater clarity, further examination of what constitutes WR will bring greater conceptual consistency. The domains that characterise WR must be made distinct with an exhaustive list of the related WR skills to provide a sound foundation and an inventory of skills that reflect what ought to be measured in each broad domain. The definitions of each domain and skill relative to performance at work will set boundaries and make it easier to understand how all the domains and skills are interrelated within and across. Studies are needed to highlight the relevance of the various assessment tools to the situation and context in which they are used and their ability to help the assessor make WR inferences. The assessment of WR skills needs to be explored to establish an inventory of items demonstrating the skills to be measured and the most appropriate assessment methods or combination of methods suitable for each domain to report an individual’s level of WR. While the most popular self-assessment tool in the Australian context is the WR scale, other tools, such as traditional written assessments and portfolio assessments, are used in the US. We recommend exploring other assessment tools, such as the diagnostic or integrative assessment, for their relevance in investigating WR from the different approaches mentioned in this paper. We also recommend probing skills development as a learning process from the equilibrium approach and looking at behavioural aspects that encourage WR behaviour among graduates within and outside educational settings. All stakeholders can benefit from a better understanding of an individual’s self-perceived employability to benefit all stakeholders with better-informed employment strategies (Donald et al., Citation2019); we, therefore, recommend research on graduates’ self-perception of WR for the benefit of all stakeholders.

Limitations

The conceptual design of WR is based on two skills frameworks; the possibility of accommodating other frameworks to complement the model was not explored. The conceptual model is under development and has not yet been validated by empirical data. This paper structures the model by presenting each domain as ‘mutually exclusive’ and does not take into account the likelihood of the interrelationships that could exist between them.

Conclusion

The complexity of the concept of WR makes it challenging to examine. This paper proposes a method to standardise the conceptualisation of WR, by considering the context, defining all the components and establishing an overarching structure that would make research findings more meaningful and communication about WR common to all.

The term WR itself must be defined so that it is clear what it encompasses and what the boundaries are, making it distinct from other overlapping terms. The authors explained how WR can be articulated from the demand, equilibrium or supply approach to guide the type of definition that will best fit a study and address any overlapping or synonymous terms. First, defining the concept must consider the context to outline the boundaries, which will otherwise not wholly capture the essence of WR to make it useful. Second, the authors have proposed a hierarchical structure to organise the level into domains and skills. However, unless they are clearly articulated, the concept will remain as a blurred picture superseded by other related concepts. This model will provide a robust theoretical foundation to construct measurement tools. It will help with a more concise definition of the components of this intangible concept to explore a wide variety of assessment tools as part of WR improvement strategies. Greater conceptual clarity will allow all stakeholders to make capital out of it for different purposes, such as skill development strategies, recruitment, and training.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bennett, D. (2020). Embedding employABILITY thinking across higher education. Final Report 2020. Australian Government.

- Bowen, D. E. (1986). Managing customers as human resources in service organizations. Human Resource Management, 25(3), 371–383. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.3930250304

- Caballero, C. L., & Walker, A. (2010). Work readiness in graduate recruitment and selection: A review of current assessment methods. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 1(1), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.21153/jtlge2010vol1no1art546

- Caballero, C. L., Walker, A., & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. (2011). The work readiness scale (WRS): Developing a measure to assess work readiness in college graduates. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 2(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.21153/jtlge2011vol2no1art552

- Casner-Lotto, J., & Barrington, L. (2006). Are they really ready to work? Employers’ perspectives on the basic knowledge and applied skills of new entrants to the 21st century US workforce (159465). ERIC. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED519465

- Cavanagh, J., Burston, M., Southcombe, A., & Bartram, T. (2015). Contributing to a graduate-centred understanding of work readiness: An exploratory study of Australian undergraduate students’ perceptions of their employability. The International Journal of Management Education, 13(3), 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2015.07.002

- Crespin, K. P., Holzman, S., Muldoon, A., & Sen, S. (2019). Framework for the future: Workplace readiness skills in Virginia. https://www.ctecs.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/WRS-Summary-Report-FINAL-2-15-19.pdf

- Donald, W. E., Baruch, Y., & Ashleigh, M. (2019). The undergraduate self-perception of employability: Human capital, careers advice, and career ownership. Studies in Higher Education, 44(4), 599–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1387107

- Forrier, A., & Sels, L. (2003). The concept employability: A complex mosaic. International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management, 3(2), 102–124. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHRDM.2003.002414

- Gardner, P. D., & Liu, W.-Y. (1997). Prepared to perform? Employers rate work force readiness of new grads. Journal of Career Planning & Employment, 57(3), 32–56.

- Healy, M. (2023). Careers and employability learning: Pedagogical principles for higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 48(8), 1303–1314. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2196997

- Hilton, M. L., & Pellegrino, J. W. (2013). A preliminary classification of skills and abilities. In M. L. Hilton & J. W. Pellegrino (Eds.), Education for Life and Work: Developing Transferable Knowledge and Skills in the 21st Century (pp. 21–36). National Academies Press.

- Holmes, L. (2001). Reconsidering Graduate Employability: The 'graduate identity' approach. Quality in Higher Education, 7(2), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538320120060006

- Holmes, L. (2013). Realist and relational perspectives on graduate identity and employability: A response to Hinchliffe and Jolly. British Educational Research Journal, 39(6), 1044–1059. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3022

- Jackson, D. (2016). Skill mastery and the formation of graduate identity in bachelor graduates: Evidence from Australia. Studies in Higher Education, 41(7), 1313–1332. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.981515

- Jackson, D., & Bridgstock, R. (2021). What actually works to enhance graduate employability? The relative value of curricular, co-curricular, and extra-curricular learning and paid work. Higher Education, 81(4), 723–739. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00570-x

- Jollands, M., Jolly, L., & Molyneaux, T. (2012). Project-based learning as a contributing factor to graduates’ work readiness. European Journal of Engineering Education, 37(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2012.665848

- Kapareliotis, I., Voutsina, K., & Patsiotis, A. (2019). Internship and employability prospects: Assessing student’s work readiness. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 9(4), 538–549. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-08-2018-0086

- Martins, E. C., & Terblanche, F. (2003). Building organisational culture that stimulates creativity and innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 6(1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/14601060310456337

- OECD. (2011). Towards an OECD skills strategy. https://www.oecd.org/education/47769000.pdf

- Okeke-Uzodike, O. E., & Naude, M. (2018). The perceived work-readiness of supply chain university graduates at a large FMCG company. Journal of Contemporary Management, 15(1), 424–446. https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC-152693ac05

- Oliver, B. (2015). Redefining graduate employability and work-integrated learning: Proposals for effective higher education in disrupted economies. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 6(1), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.21153/jtlge2015vol6no1art573

- O'Neil, F. H. J., Alrred, K., & Baker, E. L. (2014). Review of workforce readiness theoretical frameworks. In H. F. O'Neil, Jr. & H. F. O'Neil (Eds.), Workforce Readiness: Competencies and Assessment (pp. 3–25, 1st ed.). Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315805955

- Orr, P., Forsyth, L., Caballero, C., Rosenberg, C., & Walker, A. (2023). A systematic review of Australian higher education students’ and graduates’ work readiness. Higher Education Research & Development, 42(7), 1714–1731. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2023.2192465

- Rychen, D. S., & Salganik, L. H. (2003). Highlights from the OECD project definition and selection competencies: Theoretical and conceptual foundations (DeSeCo) (ED476359). ERIC. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED476359

- Shaw, J. D. (2017). Advantages of starting with theory. Academy of Management Journal, 60(3), 819–822. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2017.4003

- Sinclair, K. E. (2014). Workforce competencies of college graduates. In H. F. O'Neil, Jr. & H. F. O'Neil, (Eds.), Workforce Readiness (pp. 103–120). Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315805955

- Symonds, J. E., & O'Sullivan, C. (2017). Educating young adults to be work-ready in Ireland and the United Kingdom: A review of programmes and outcomes. Review of Education, 5(3), 229–263. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3099

- Tentama, F., & Riskiyana, E. R. (2020). The role of social support and self-regulation on work readiness among students in vocational high school. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 9(4), 826–832.

- Thijssen, J. (2000). Employability in het brandpunt. Aanzet tot verheldering van een diffuus fenomeen. Tijdschrift HRM, 1, 7–34.

- Tomlinson, M. (2017). Forms of graduate capital and their relationship to graduate employability. Education & Training, 59(4), 338–352. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-05-2016-0090

- Verma, P., Kumar, S., & Nankervis, A. (2019). Work-readiness integrated competence model: Conceptualisation and scale development. Education & Training, 61(5), 568–589. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-05-2018-0114

- Vroom, V. H. (1982). Work and motivation. R.E. Krieger.

- Winterton, J. (2019). European, American and Japanese perspectives on work-readiness: Implications for the Asia-pacific region. In S. Dhakal, V. Prikshat, A. Nankervis, & J. Burgess (Eds.), The Transition from Graduation to Work (pp. 43–62). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0974-8_4

- Winterton, J., & Turner, J. J. (2019). Preparing graduates for work readiness: An overview and agenda. Education & Training, 61(5), 536–551. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-03-2019-0044