Abstract

In this article, the author describes the experiences that shaped his personal philosophy as an educator, and the importance of promoting and teaching a type of physical education that will lead to a society in which healthy, active lifestyles are the norm rather than the exception.

During my junior year of high school I took an elective physical education course. By comparison with other physical education courses that I had taken, the course was anything but traditional. Traditional physical education courses of the day — at least where I went to school — were authoritarian, competitive, hierarchical, often organized militaristically, team sports–oriented, and marginalizing for most by a pervasive “winner takes all” or “survival of the fittest” ideology.

This elective physical education course was different. It focused on promoting lifetime fitness, and it was autonomous, cooperative, humanistic and inclusive. During class we ventured off school grounds and into the local community. We ice skated at a local rink, bowled at a local bowling alley, and ran through the local neighborhoods instead of around the high school track. We learned about and interacted with the community around us. Our “gymnasium” was defined by a proximity boundary of about five miles in any one direction of the school and the community assets and resources available within that boundary. It was a fertile learning environment, as well as freeing, fun, highly engaging and meaningful.

Each week we had to obtain a certain number of activity and/or mileage credits. On some days we were scheduled to walk, jog or run — our choice. Various routes were available to us, each of different distances. The most challenging was the “Main Street Treat,” which was a steep, uphill route. The reward for that choice was double mileage credit, a feeling of camaraderie among those making the choice, and a true sense of accomplishment for the achievement. We also learned that increasing speed was not the only means of increasing intensity!

Our physical education instructor taught us how to behave and stay out of trouble during our outings, too — in other words, how to be good citizens. Through the course we learned a number of valuable life lessons related to taking care of one another, the community and ourselves.

Understanding the Experience as a University Student

As a physical education major in college, some of my professors referred to the elective physical education course that I experienced in high school as “new physical education,” whereas others called it “lifetime fitness” or an “adult fitness” model. Regardless of the label, the overarching approach — autonomous, inclusionary, highly participatory, focused on lifetime physical activities and skills rather than team sports — resonated with me, and I constructed my personal philosophy and subsequent curriculum and lessons with these values in mind. It was by no means mainstream thinking or common practice, a point brought to bear during my student-teaching experience.

At the school where I was placed for my final student teaching, I was encouraged to maintain the program's status quo, which included “Dodgeball Friday” and other exclusionary and inappropriate instructional practices. There were other challenges, too. For example, the school had one indoor racquetball court, and every student was supposed to have an opportunity to play racquetball over the course of two weeks. I calculated the available court time for each student to be five minutes. What can a student learn about racquetball with only five minutes of on-court time? Even more importantly, how could I keep all of the other students appropriately engaged during the two weeks allotted for racquetball? Fortunately, one of my primary supervising teachers was an open and willing collaborator in seeking solutions and offering suggestions for these and the many other questions that arose.

Regardless, it was still challenging to go against the established norm at the school. Snide comments were made, some students complained about the changes we implemented, some lessons we tried did not go as planned, and some of the other teachers questioned what we were doing and why. It was not easy, and more than one person suggested that it would be okay to at least occasionally take the “roll out the balls and make sure nobody gets hurt” approach. I reasoned — rightly so, I think — that that would be a dangerous path to trek down.

Two things helped to keep me grounded. First, I had experienced that elective physical education class in high school. Second, I had developed a written philosophy that articulated my vision for what physical education ought to be as part of my “History and Philosophy of Physical Education” course. The professor of that course required full justification and sound documentation to accompany our philosophy statement, and diverse and multiple references were to be appropriately cited. It took hours to construct, including many hours in the library locating and reading journal articles and book chapters, and many more hours drafting, redrafting and revising. It was no slouch assignment! But, like most things in life, the effort invested paid dividends later.

Self-understanding: The Importance of Having a Personal Philosophy

My personal philosophy was built on the back of a series of belief statements, some of which I have shared previously. For example:

First, I believe that physical activity is a basic need of the human organism, and participation in physical activity is a fundamental human right. Second, I believe that effective, positive and safe physical activity opportunities must be available for all people, regardless of life stage or social circumstance. Third, knowing that people live in dynamic environments and that the health benefits of physical activity cannot be stored, I believe that physical activity education and opportunities must occur across the lifespan. Finally, in considering a life-course perspective to the promotion of physical activity (CitationLi, Cardinal, & Settersten, 2009), physical activity educators need to understand that people change (e.g., affectively, cognitively, and physically) and people's contexts change and evolve (e.g., socioeconomically, sociopolitically). This will help them anticipate distinct challenges and opportunities associated with getting and keeping people physically active. (CitationCardinal, 2015, pp. 322–323)

Reflecting on my beliefs, I can see the powerful influence of my 11th-grade physical education instructor and the curricular approach that was implemented at that time. While recognizing the contributory value of accumulating all forms of physical activity throughout the day (e.g., through classroom physical activity breaks [or brain boosters], before/noon/after-school physical activity programs, and/or walking or biking to and from school), it is imperative that quality and substantive physical education classes not be neglected or otherwise waived (CitationLounsbery, Holt, Monnat, Funk, & McKenzie, 2014). In other words, excellent physical education classes and programs must remain at the heart of a comprehensive school physical activity program (CitationCenters for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). I have often thought that the elective physical education course that I took in high school, with its focus on total inclusion, high participation and strong community engagement, should have been the required course that all students took. That belief stems from my understanding of the “inverted triangle” concept.

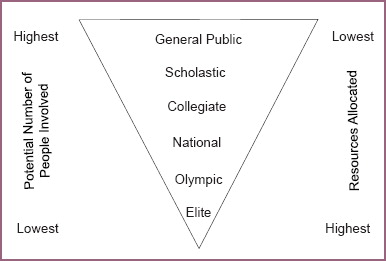

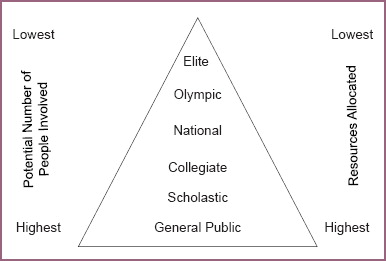

The Inverted Triangle Concept

As shown in and , the inverted triangle concept reveals that to have the largest and broadest impact on people and society, the needs of the masses — labeled “general public” in the diagrams — must be the focus. If the apex of the triangle is inverted and programs, products and services (i.e., resources) are devoted almost exclusively to helping the healthiest and fittest get even more healthy and fit, the triangle will be unstable and can easily be toppled over (see ). On the other hand, if the apex of the triangle is positioned at the top of the triangle, like the capstone of a pyramid, it will be a much stronger and stable structure, one that seeks to meet the needs of everyone (see ). This value proposition is in direct contrast to the exclusive type of physical education that I had otherwise experienced in my youth, with the exception of the one elective physical education class in 11th grade. With spectatoritis — the propensity of people to watch physical activity rather than do physical activity (CitationNash, 1932) — and hypokinetic diseases — the diseases associated with disuse and physical inactivity (CitationKraus & Raab, 1961) — continuing to threaten those living in the industrialized world (CitationDing et al., 2016; CitationReis et al., 2016; CitationSallis et al., 2016), quality physical education classes and programs that promote active, healthy living and that allow people to have profoundly meaningful physical activity experiences are something that we need more of, particularly if we are to achieve SHAPE America's goal of “50 Million Strong by 2029” (CitationSociety of Health and Physical Educators, 2015). For this to occur, the limited time and resources available in physical education must focus on reaching the largest number of people possible (i.e., engaging in inclusionary and high-participation policies and practices; CitationCardinal, 2016).

It is also important to remember that while 50 million is a big number, a number derived from an estimate as to how many children and youth will be in the K–12 school system in the United States in the year 2029, as a field we cannot ignore the masses. For example, an even larger demographic — 74 million people, approximately 40 percent more — will be ≥65 years of age at that time, and those who make it to 65 are projected to live an additional 19 years (CitationNational Prevention Council, 2016). It is crucial that we not forget that, “Fitness is a journey, not a destination; you must continue for the rest of your life” (CitationCooper, n.d.). This is a “womb to tomb” proposition, and it can be achieved only when physical activity education extends beyond the gym and beyond school-age populations (CitationCardinal, 2010; CitationLarouche, Laurencelle, Shepard, & Trudeau, 2015). Helping people navigate the various physical activity contexts and situations that will inevitably emerge during their lifespan is imperative (CitationLi, Cardinal, & Settersten, 2009). Collaborative, interdisciplinary and multi-sectoral efforts are required (CitationCardinal, 2014; CitationSchary & Cardinal, 2015) — something else that I began to learn about in my 11th-grade elective physical education class.

Conclusion

This editorial began with a story — the story of a quality physical education experience that I had some 37 years ago. The fact that I can recall and share the story now is indicative of just how profound the experience was. I cannot tell you how many push-ups or sit-ups I could do back then, or how fast I could run the mile. That, too, conveys an important message. Unbeknownst to me at the time, that course would later help me to formulate and justify my own philosophy of physical education, a philosophy that resulted from a great deal of effort and sacrifice. That philosophy helped me to stay true to myself, even when circumstances were not always favorable for doing so.

I was fortunate to enroll in that elective physical education course all those years ago. Had I not, my physical education story would have most assuredly been different, as would have been my career. Through this I have learned many important lessons, not the least of which is that there really is more to physical education than meets the eye.

What impression of physical education will be forever implanted in the minds of your students? What sorts of stories will they recall and tell in the future? The answers to those questions are paramount to achieving not only “50 Million Strong by 2029” (CitationSHAPE America, 2015), but a radical transformation of people and society in which healthy, active lifestyles are the norm rather than the exception.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Bradley J. Cardinal

Bradley J. Cardinal ([email protected]) is a professor in the College of Public Health and Human Sciences at Oregon State University in Corvallis, OR, and co-chair of the JOPERD Editorial Board.

References

- Cardinal, B. J. (2010). Social institutions in support of physical activity and health: Moving beyond school-based programs. International Journal of Human Movement Science, 4, 5–21.

- Cardinal B. J. (2014). Physical activity psychology research: Where have we been? Where are we going? Kinesiology Review, 3, 44–52. Retrieved from doi:10.1123/kr.2014-0036

- Cardinal, B. J. (2015). The 2015 C. H. McCloy Lecture: Road trip toward more inclusive physical activity: Maps, mechanics, detours, and traveling companions. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 86, 319–328. doi:10.1080/02701367.2015.1088766

- Cardinal, B. J. (2016). Toward a greater understanding of the syndemic nature of hypo-kinetic diseases. Journal of Exercise Science and Fitness, 14, 54–59. doi:10.1016/j.jesf.2016.07.001

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Comprehensive school physical activity programs: A guide for schools. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Cooper, K. H. (n.d.). Cooper Aerobics Health & Wellness: Kenneth H. Cooper, MD, MPH. Retrieved from http://www.cooperaerobics.com/Cooper-Clinic/Our-Physicians/Kenneth-H-Cooper,-M-D,-M-P-H.aspx

- Ding, D., Lawson, K. D., Kolbe-Alexander, T. L., Finkelstein, E. A., Katzmarzyk, P. T., van Mechelen, W., … Lancet Physical Activity Series 2 Executive Committee. (2016). The economic burden of physical inactivity: A global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet, 388, 1311–1324. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30383-X

- Kraus, H., & Raab, W. (1961). Hypokinetic disease: Diseases produced by lack of exercise. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

- Larouche, R., Laurencelle, L., Shepard, R. J., & Trudeau, F. (2015). Daily physical education in primary school and physical activity in midlife: The Trois-Rivières study. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 55, 527–534.

- Li, K.-K., Cardinal, B. J., & Settersten, R. A., Jr. (2009). A life-course perspective on physical activity promotion: Applications and implications. Quest, 61, 336–352.

- Lounsbery, M. A., Holt, K. A., Monnat, S. M., Funk, B., & McKenzie, T. L. (2014). JROTC as a substitute for PE: Really? Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 85, 414–419. doi:10.1080/02701367.2014.930408.

- National Prevention Council. (2016). Healthy aging in action. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. Retrieved from http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/priorities/prevention/about/healthy-aging-in-action-final.pdf

- Nash, J. B. (1932). Spectatoritis. New York, NY: Holston House-Sears.

- Reis, R. S., Salvo, D., Ogilvie, D., Lambert, E. V., Goenka, S., Brownson, R. C., & Lancet Physical Activity Series 2 Executive Committee. (2016). Scaling up physical activity interventions worldwide: Stepping up to larger and smarter approaches to get people moving. Lancet, 388, 1337–1348. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30728-0

- Sallis, J. F., Bull, F., Guthold, R., Heath, G. W., Inoue, S., Kelly, P., … Lancet Physical Activity Series 2 Executive Committee. (2016). Progress in physical activity over the Olympic quadrennium. Lancet, 388, 1325–1336. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30581-5

- Schary, D. P., & Cardinal, B. J. (2015). Interdisciplinary and intradisciplinary research and teaching in kinesiology: Continuing the conversation. Quest, 67, 173–184. doi:10.1080/00336297.2015.1017586

- Society of Health and Physical Educators. (2015). About 50 million strong. Retrieved from http://50million.shapeamerica.org/about-us/