Abstract

Objective: The patient-physician encounter provides an ideal opportunity to assess a patient’s dietary history and its impact on total health. However, nutrition assessments and counseling in physician-patient encounters is often lacking. Insufficient nutrition education during medical school may lead to insecurity in assessing and counseling patients.

Methods: Physicians and registered dietitians (RD) co-developed and co-facilitated a nutrition workshop for first-year medical students. Goals included increasing recognition of nutrition’s impact on health and promoting student confidence and skills when attaining a nutrition history, assessing risk factors, and advising.

Results: Seventy percent of students attested to having “sufficient” knowledge to counsel a patient on nutrition after the session compared to 38% before (Z= −4.46, p < 0.001). Sixty eight percent felt comfortable completing a nutritional assessment after the session compared to 35% before (Z= −4.30, p < 0.001). Sixty-three percent felt confident in advising patients about nutrition after the session compared to 32% before (Z= −4.20, p < 0.001). Students also significantly outperformed a control cohort on a nutrition-related component of an Objective Standardized Clinical Examination.

Conclusions: Clinical nutrition education can be successfully integrated into the medical school curriculum as early as the first year. Interprofessional collaboration with RDs provided evidence-based content and authentic clinical experience in both the development of the workshop and in facilitating student discussion.

Introduction

In 2018 Doctor Alan L. Buchman submitted that “knowledge of the relationship of nutrition and disease as well as therapeutic nutrition to prevent and to treat disease is perhaps some of the most important medical information that can be disseminated (Citation1)”. The concept that nutrition largely defines and predicts one’s general overall health is not novel. The patient-physician encounter provides an ideal opportunity to assess a patient’s dietary history and its impact on overall health. Physician nutritional counseling can provide edification, guidance, and motivation in order to prevent and treat chronic diseases. However, while most physicians believe there is a benefit to counseling patients on nutritional matters, few physicians actually provide this counseling (Citation2). Three-quarters of family physicians surveyed support counseling for dietary intake of fat and cholesterol (Citation3). Fifty percent encourage referral of patients to a dietitian (Citation3). However, a survey of primary care physicians revealed that two-thirds counsel less than half of their patients (Citation4). In addition, only 5 minutes is spent on the dietary advisement of those patients (Citation4). Reports from patients corroborate this paucity of nutrition advisement. Approximately one-third of adult patients surveyed reported any physician dialogue regarding fruit and vegetable consumption and dietary fat intake (Citation5).

Insufficient nutrition education during undergraduate and graduate medical education may lead to physician insecurity in assessing and counseling patients. In 1985, the Committee on Nutrition in Medical Education concluded that nutrition education in U.S. Medical Schools was “largely inadequate” (Citation6). It recommended a minimum of 25–30 classroom hours in preclinical years to include the topics of energy balance, specific nutrient and dietary components, nutritional assessment, protein-energy malabsorption, nutrition, and disease prevention and risks from poor dietary practices (Citation6). Curricular expansion has been inadequate despite these recommendations. While almost all medical colleges surveyed by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) reported including the topic of nutrition in required and elective courses (Citation7), a 2015 study by Adams et al. noted that 71% of surveyed U.S. medical schools still did not provide the minimum 25 hours of nutrition education across the four year curriculum (Citation8). Most schools provided the recommended basic-science related content (e.g., “energy balance”), however few provided the clinically correlated content within preclinical curriculums (Citation9) or clinical practice (Citation8). In addition, “lecture” was overwhelmingly the most common method of teaching nutrition in medical schools compared to more applied-learning approaches such as problem-based learning and small group discussions (Citation10).

A gap also exists if we consider “assessment drives learning” (Citation11). Preparation material for the U.S. Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) references nutrition in almost one-third of its question stems (Citation12). However, few of these questions are related to critical topics including prevention of disease, obesity, or nutrition’s impact on chronic diseases, and instead focus on vitamin and mineral deficiencies (Citation12).

The dearth of time devoted to nutrition education is perceived by both medical students and faculty. Eighty-five percent of incoming students in one medical college recognized a need for nutrition education in medical school training (Citation13), yet only one-third of graduating US medical students attested that “appropriate time” was devoted to nutritional instruction during their medical education (Citation14). Results from a 2020 benchmark study note only 10% of U.S. medical schools surveyed attest to their graduating students being “very prepared” to manage patients with obesity (Citation15).

The lack of nutrition training is evident in graduate medical education as well. Only 14% of internal medicine residents felt physicians were adequately taught to provide nutrition counseling (Citation16).

Preclinical students at The Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell (ZSOM) have echoed these concerns. Since the school’s inception in 2011, students were exposed to nutrition education as it pertained to their basic science material and as mentioned within their hybrid case-based/problem-based learning sessions throughout the first two years of medical school. We piloted a novel interprofessional nutrition workshop for first-year medical students during their basic science gastroenterology course to begin to fill this educational gap. Burch et. al advocated the use of dietitians as nutrition teachers in medical education, and it is the position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics that registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs) should play a significant role in educating medical students, residents, fellows, and physicians in practice (Citation17, Citation18). Recognizing the unique expertise of dietitians to provide knowledge, resources, and clinical pearls to our students, the workshop was jointly facilitated by clinical physician faculty and registered dietitians (RD). The purpose of the workshop was to increase student recognition of nutrition’s impact on growth and development, quality of life, health maintenance, and disease prevention and treatment. We aimed to teach the preliminary skills necessary to attain a detailed nutrition history, assess nutritional risk factors and advise. We predicted this curricular intervention would increase student confidence and skill in performing a basic nutritional assessment and initial nutritional counseling.

Materials and methods

Methods

Subjects

This nutrition workshop was a mandatory curricular session for the ninety-nine students enrolled in their first year of medical school (class of 2022) at the ZSOM. We compared these students to the cohort of students enrolled in the first year of medical school the previous academic year (class of 2021). The class of 2021 was used as a historical control to determine the impact of the nutrition curriculum on student’s ability to perform nutritional counseling during a standardized patient encounter.

Procedure

We convened an interprofessional nutrition workshop session planning team which included the “Fueling the Body” course director (Ph.D.), physician faculty (M.D.s), registered dietitians (R.D.s) as well as a small group of second year medical students to develop the nutrition workshop. The 9-week integrated “Fueling the Body” course, incorporates the biochemical pathways, histology, structure, physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology associated with the gastrointestinal system (Citation19). We anticipated embedding clinical nutrition into this course would likely provide relevance and applicability for students.

One week prior to the workshop students were given pre-session readings in accordance with the flipped-classroom model at our school and to provide foundational information for the workshop (Supplemental Material A). Students were also required to complete a personal three-day food diary using the MyFitnessPal® App or website prior to the workshop in order to familiarize themselves with use of a food diary. All faculty members participated in a one-hour faculty development session just prior to the workshop to review the goals, objectives, and logistics of the workshop. Each facilitator also received a faculty guide with prompted questions to standardize the discussion amongst the small student groups (Supplemental Material B).

On the day of the workshop all students participated in a 20-minute interdisciplinary nutrition framing discussion. The framing discussion was led by a gastroenterologist and Registered Dietitian. Topics included the purpose of a nutritional assessment, why nutrition is important to clinical practice, and how a medical provider can conduct a nutritional assessment. Students were then divided into preassigned groups consisting of 16 students following the framing discussion. Each small group was presented with 3 different clinical case vignettes for analysis and discussion. The first case described a patient with diabetes and morbid obesity. The second case depicted a breastfeeding, vegetarian mother with vitamin deficiencies. The third case highlighted irritable bowel syndrome in a patient with potential dietary triggers. Each of the cases were assigned to a faculty team consisting of a physician and registered dietitian. This joint facilitation approach provided a critical interprofessional approach to learning. Faculty teams rotated through the student groups rooms during the 75-minute workshop. Students were tasked with reviewing a relevant nutritional and dietary history, interpreting laboratory data and physical exam findings, reflecting on the value of the nutritional assessment for each case, and advising the patient. Each case discussion lasted 25 minutes.

Evaluation

We administered an online survey through Qualtrics (https://www.qualtrics.com/) to all first-year medical students one week prior to and one week after the nutrition workshop, and afforded the students one week to complete the survey (Appendices A & B respectively). The surveys consisted of 6 items specifically assessing student perceptions of the value of physician nutrition knowledge and counseling skills as well as their own comfort with nutritional knowledge, assessment, and counseling. Surveys were piloted for face and content validity by student planning committee members Reponses were based on a 5-point Likert scale: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3= Neither Agree nor Disagree, 4 = Agree, and 5 = Strongly Agree.

We also measured nutritional assessment skill performance on a summative multi-stationed Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) administered at the end of the “Fueling the Body” course, approximately 7 weeks after the nutrition workshop. The OSCE provides students the opportunity to interview (and/or examine) standardized patients in a simulated clinical setting. Standardized patients are trained to observe the students and complete a competency checklist at the conclusion of the encounter. Our students participated in an OSCE during their final examination week, approximately 7 weeks after the nutrition workshop. During one OSCE station students encountered a standardized patient with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes (Supplemental Material C). She relayed a chief concern of struggling to lose weight over the past 2 months and reported “always having problems with [her] weight.” The patient attributed concurrent fatigue and joint pain to her weight and was concerned that her increased weight would “cause a heart-attack or stroke.”

For the purposes of this study, we focused on the four specific OSCE checklist items that were relevant to the nutritional/weight assessment. Checklists were completed by standardized patients who received specific training on this case. Checklist items included whether the student elicited the patient’s sleep, exercise, food and beverage intake, and life stress. Each item was scored on a scale from 0 (no credit) to 2 (full credit), and therefore students could achieve a total of 8 points. A percentage score was calculated for this analysis. The results of the OSCE checklist from the cohort of students participating in this nutrition workshop during the 2018–2019 academic year were compared to a cohort of students who had not received the nutrition workshop in the 2017–2018 academic year.

A communication skill score was used as a control measure in order to determine if student performance on the OSCE was better overall, or if differences in student performance were limited to a specific part of the OSCE (e.g., the nutrition assessment). There were 13 items in the communications OSCE score, also based on a 0–2 scale, such that students could achieve a total of 26 points and a percentage score was calculated. Some of the items in the communications OSCE score include whether students properly introduced themselves, refrained from distracting non-verbal behaviors, conveyed empathy, asked about the chief complaint, used clear language avoiding jargon, and reviewed the information gathered and clarified next steps. These are complementary to the nutrition checklist items used to assess students.

Statistical analysis

Data were statistically evaluated using IBM SPSS Statistics (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA, Version 24.0). Descriptive statistics are presented as the mean and standard deviation for the nutrition and communication OSCE percentage scores. Individual nutrition OSCE checklist items completed by the trained SPs are presented as the mean and standard deviation raw scores, and survey data is presented as the percentage of students who “Strongly Disagree/Disagree, Neither Agree nor Disagree, and Strongly Agree/Agree” to each of the 6 survey items. The Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test was used to determine differences in student responses before and after the nutrition session (within-subjects analysis). An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine group (control vs. nutrition workshop group) differences on OSCE performance. For all tests, p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Hofstra University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the research conducted in this study under Exempt Review procedures.

Results

Ninety-nine students participated in the pilot nutrition workshop. Survey data for both pre- and post-session were matched for 63 students (29 males, 34 females). The following data were not included in the current analysis: 28 students participated in the pre-session survey but not the post-session survey (14 males, and 14 females), 7 students participated in the post-session survey but not the pre-session survey (no demographic data available), and 1 student did not participate in either survey. For the OSCE sessions, data from all students in the nutrition session group (N = 99) and the historical control group (N = 98) were available for analysis. There were no exclusions of OSCE session data for either group.

Pre- and Post-Nutrition session survey data

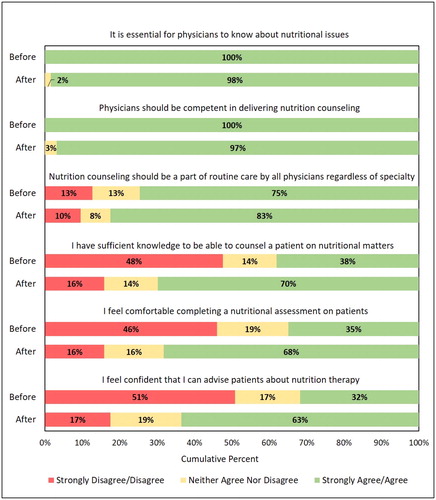

shows the cumulative percent of student responses for each of the 6 survey items before and after participating in the nutrition session. For the survey items, there was no significant difference in student responses pre-and post-session to statements regarding the knowledge and skills that physicians should have regarding nutrition counseling. One hundred percent of students (N = 63) strongly agreed/agreed that it is essential for physicians to know about nutritional issues and that physicians should be competent in delivering nutrition counseling with no significant change after the nutrition session (Z= −1.0, p = 0.32 and Z= −1.4, p = 0.16, respectively). Before the session, 75% (N = 47) of students strongly agreed/agreed that nutrition counseling should be part of routine care by all physicians and after the session 83% (N = 52) strongly agreed/agreed with this statement (Z= −1.49, p = 0.14).

Figure 1. The cumulative percent of student responses for each of the 6 survey items before and after the nutrition session. Responses were collapsed into 3 ordinal categories: Strongly Disagree/Disagree (red), Neither Agree nor Disagree (yellow), and Strongly Agree/Agree (green). There was a significant improvement in student’s self-perceived knowledge, comfort, and confidence completing a nutritional assessment with a patient (all p-values < 0.001), but no change in student’s beliefs about the importance of nutritional counseling and the role of the physician in the process.

There was a significant improvement in student’s self-perceived knowledge, comfort, and confidence after the nutritional session. Seventy percent of students (N = 44) strongly agree/agreed that they had sufficient knowledge to counsel a patient on nutrition matters after the session compared to 38% (N = 24) before (Z= −4.46, p < 0.001). Sixty eight percent of students (N = 43) strongly agree/agreed that they felt comfortable completing a nutritional assessment after the session compared to 35% (N = 22) before (Z= −4.30, p < 0.001). Finally, 63% (N = 40) of students strongly agree/agreed that they felt confident in advising patients about nutrition after the session compared to 32% (N = 20) before (Z= −4.20, p < 0.001).

OSCE data

presents mean (and standard deviation) performance scores on the OSCE for the historical control (2017–2018) and the nutrition session (2018–2019) groups. Students who attended the nutrition session outperformed students in the control group on the overall nutrition OSCE score (t(195)= −7.48, p < 0.001). Three of the four checklist items that make up the nutrition OSCE score were higher in the nutrition session group than the control group, including sleep (t(195)= −2.81, p = 0.005), exercise or activity (t(195)= −4.15, p < 0.001), and food/beverage intake (t(195)= −11.51, p < 0.001). Student performance on the question regarding stress or life changes was not significantly different between the groups (t(195)= −0.03, p = 0.97). We also analyzed student’s communication OSCE score to see if students in the nutrition session group simply outperformed the control group on the OSCE. In general the results show that communication OSCE scores were not significantly different between the two groups (t(195)= −0.91, p = 0.37).

Table 1. Mean (standard deviation) performance scores on the OSCE for the control group and the nutrition workshop group. Nutrition and Communication OSCE scores are depicted as a percentage score, whereas individual nutrition OSCE items are presented as a raw score (based on a scale from 0–2). * indicates p < 0.001.

Discussion

Overall, the nutrition workshop resulted in self-assessed improvement in knowledge, comfort, and confidence. Only one-third of our students felt knowledgeable, comfortable, and confident in providing nutritional care prior to attending the nutrition workshop despite their rigorous basic science education. However, the implementation of our interdisciplinary nutrition workshop significantly impacted these variables. After the workshop students reported sufficient knowledge to counsel a patient about nutrition (70%), felt comfortable completing a nutritional assessment (68%) and felt confident advising about nutritional therapy (63%).

The evaluation of objective data from the student performance on the OSCE nutrition station also supports the impact of this required curriculum nutrition workshop. Compared to the control class of students, which had not participated in the nutrition workshop, a significantly greater number of students in the current participating class questioned the standardized patients about food intake, as well as sleep and exercise.

The vast majority of medical students surveyed both pre- and post- nutritional workshop identified knowledge of nutrition and nutritional counseling competency as being an essential aspect of a physician’s skill set. Likewise, students agreed that nutrition counseling should be a part of routine patient care. These results were not unexpected and are corroborated by the literature. Previously published studies highlight students’ recognition of the value of nutrition care during patient encounters (Citation20–22).

The findings from this study emphasize the value of integrating clinical nutrition education into the medical school curriculum as early as the first year of undergraduate medical education. It has been suggested that medical educators not only teach students about nutrition, exercise, stress and sleep management but also assess student knowledge and skills through competency exams (Citation23). Introduction of nutritional content enhanced medical student knowledge, comfort, and confidence in providing nutritional care. Furthermore, this objectively translated into a significantly increased number of students assessing nutrition and associated behaviors during an OSCE encounter. OSCE is used as a tool for the assessment of performance within simulated environments (Citation24) and can be useful in predicting students’ knowledge and skills in future patient encounters (Citation25–27). Additionally, OSCE can drive learning, and therefore, can have a positive educational impact (Citation24, Citation28). We are thus optimistic that the improved OSCE nutrition component scores reflect enhanced student knowledge and skills and will ultimately result in their ability to perform nutrition assessments and manage of patients during their postgraduate training and beyond.

Collaboration between registered dietitians and physicians was a highly valuable model for this session. Dietitians provided experience and critical content in both the development of the workshop and in facilitating discussion among the students. Additionally, involvement of RDs during the workshop reinforced the strong advantages of an interprofessional approach to patient care and the benefits of collaborating when greater expertise is desired (Citation18, Citation29).

Finally, the design of our workshop aligns with the personalized nutrition (PN) model proposal by the American Nutrition Association (Citation30). Our created case studies reflect the three main areas of personalized nutrition (PN science and data, PN education and training and PN guidance and therapeutics) by highlighting the biopsychosocial influences on an individual patient’s health, by teaching students how to assess a patient’s nutritional status, and modeling personalized counseling strategies (Citation30).

Limitations of the study

One limitation of this study was the low response rate of students who completed both the pre-and post-workshop survey (64%). Thus, only data from 2/3 of the class was evaluated and reported. The reduction in useable data could have potentially affected the significant outcomes. A second limitation is that the OSCE checklist items were not developed to assess whether or not a student performed nutritional counseling. While we were able to use checklist items relevant to nutrition/weight assessment, SPs were not explicitly asked to rate the students’ quality of nutritional assessment and nutritional counseling. This will be addressed in future cohort classes of students. An additional limitation of the study is that we did not obtain qualitative comments about the students’ perception of the workshop and how it impacted their education. Qualitative data may have provided valuable insights into student rationale for their responses. Finally, the results are restricted to a single institutional study.

Future directions

Scheduling additional classroom time devoted specifically to clinical nutrition is challenging in an already crowded medical school curriculum. Given this, we were only able to provide 2 classroom hours dedicated to nutrition in our preclinical curriculum. We were time-limited in the ability to both teach basic nutritional concepts and practice the skill set of obtaining a nutrition history and counseling patients. As such, we provided students with a nutrition history during the sessions, rather than have students obtain the information themselves. We believe student confidence and aptitude will increase with additional classroom time and plan to provide at least one additional classroom hour of instruction this coming year. This additional time will afford students the opportunity to role-play and practice the skill of taking a nutritional history, rather than it being provided in the written case vignettes.

A long-term goal is to embed clinical nutritional correlates in each of the basic science courses in order to reinforce relevance and applicability to disease. In addition, we hope to assess the retention of skills and durability of our findings using an OSCE of a patient with knee osteoarthritis and obesity during a rheumatology course one year after the workshop, in year 2 of our ZSOM curriculum. We are also currently working to build in additional training and practice opportunities during the clinical years 3 and 4.

Conclusion

The results of this study advocate the introduction of nutritional training early in medical school education to promote students’ knowledge of nutrition, and their comfort and confidence in assessing and counseling patients. We are optimistic that implementation and expansion of such training will lead our future physicians to apply this acquired knowledge and skills in the provision of patient care. We are hopeful that our contribution to the literature will serve as an impetus for other schools to promote clinical nutrition education in their medical school curriculums.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jennifer Kelly for her assistance in preparing guides, distributing surveys, and compiling data for this study.

References

- Buchman AL. Nutrition and disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2018;47(1):xiii–xxiv. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2017.12.002.

- Wynn K, Trudeau JD, Taunton K, Gowans M, Scott I. Nutrition in primary care: current practices, attitudes, and barriers. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(3):e109–16.

- Soltesz KS, Price JH, Johnson LW, Tellijohann SK. Family physicians’ views of the preventive services task force recommendations regarding nutritional counseling. Arch Fam Med. 1995;4(7):589–593. doi:10.1001/archfami.4.7.589.

- Kushner RF. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Prev Med. 1995;24(6):546–552. doi:10.1006/pmed.1995.1087.

- Kreuter MW, Chheda SG, Bull FC. How does physician advice influence patient behavior? Evidence for a priming effect. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(5):426–433. doi:10.1001/archfami.9.5.426.

- Council NR. Nutrition education in U.S. In: Medical schools. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 1985.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Number of medical schools including topic in required courses and elective course: nutrition. AAMC Curriculum Inventory 2018–2019. 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/curriculum-reports/interactive-data/content-documentation-required-courses-and-elective-courses.

- Adams KM, WS, Butsch Kohlmeier M. The state of nutrition education at US medical schools. J Biomed Educ. 2015;2015:1–7. doi:10.1155/2015/357627.

- Adams KM, Kohlmeier M, Zeisel SH. Nutrition education in U.S. medical schools: latest update of a national survey. Acad Med. 2010;85(9):1537–1542. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181eab71b.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical schools reporting use of selected teaching formats in nutrition, 2018–2019. AAMC Curriculum Inventory 2018–2019. 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/curriculum-reports/interactive-data/instructional-methods-used-teach-basic-science-disciplines.

- Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9 Suppl):S63–S7. doi:10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045.

- Patel S, Taylor KH, Berlin KL, Geib RW, Danek R, Waite GN. Nutrition education in U.S. medical schools: an assessment of nutrition content in USMLE STEP preparation materials. JCT. 2015;4(1):108–113. doi:10.5430/jct.v4n1p108.

- Cresci G, Beidelschies M, Tebo J, Hull A. Educating future physicians in nutritional science and practice: the time is now. J Am Coll Nutr. 2019;38(5):387–394. doi:10.1080/07315724.2018.1551158.

- Lockwood JH, Sabharwal RK, Danoff D, Whitcomb ME. Quality improvement in medical students’ education: the AAMC medical school graduation questionnaire. Med Educ. 2004;38(3):234–236. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2004.01760.x.

- Butsch WS, Kushner RF, Alford S, Smolarz BG. Low priority of obesity education leads to lack of medical students’ preparedness to effectively treat patients with obesity: results from the U.S. medical school obesity education curriculum benchmark study. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):23. doi:10.1186/s12909-020-1925-z.

- Vetter ML, Herring SJ, Sood M, Shah NR, Kalet AL. What do resident physicians know about nutrition? An evaluation of attitudes, self-perceived proficiency and knowledge. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27(2):287–298. doi:10.1080/07315724.2008.10719702.

- Burch E, Crowley J, Laur C, Ray S, Ball L. Dietitians’ perspectives on teaching nutrition to medical students. J Am Coll Nutr. 2017;36(6):415–421. doi:10.1080/07315724.2017.1318316.

- Hark LA, Deen D. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: interprofessional education in nutrition as an essential component of medical education. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(7):1104–1113. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2017.04.019.

- Ginzburg S, Brenner J, Willey J. Integration: a strategy for turning knowledge into action. MedSciEduc. 2015;25(4):533–543. doi:10.1007/s40670-015-0174-y.

- Schoendorfer N, Gannaway D, Jukic K, Ulep R, Schafer J. Future doctors’ perceptions about incorporating nutrition into standard care practice. J Am Coll Nutr. 2017;36(7):565–571. doi:10.1080/07315724.2017.1333928.

- Schoendorfer N, Schafer J. Enabling valuation of nutrition integration into MBBS program. J Biomed Educ. 2015;2015:1–6. doi:10.1155/2015/760104.

- Crowley J, Ball L, Yeo Han D, McGill A-T, Arroll B, Leveritt M, Wall C. Doctors’ attitudes and confidence towards providing nutrition care in practice: comparison of New Zealand medical students, general practice registrars and general practitioners. J Prim Health Care. 2015;7(3):244–250. doi:10.1071/HC15244.

- Eisenberg DM, Burgess JD. Nutrition education in an era of global obesity and diabetes: thinking outside the box. Acad Med. 2015;90(7):854–860. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000682.

- Khan KZ, Ramachandran S, Gaunt K, Pushkar P. The Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE): AMEE guide no. 81. part I: an historical and theoretical perspective. Med Teach. 2013;35(9):e1437–46. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2013.818634.

- Rutala PJ, Fulginiti JV, McGeagh AM, Leko EO, Koff NA, Witzke DB. Predictive validity of a required multidisciplinary standardized-patient examination. Acad Med. 1992;67(10):S60–S2. Suppl):doi:10.1097/00001888-199210000-00040.

- Hodges B, Regehr G, Hanson M, McNaughton N. Validation of an objective structured clinical examination in psychiatry. Acad Med. 1998;73(8):910–912. doi:10.1097/00001888-199808000-00019.

- Jefferies A, Simmons B, Tabak D, Mcilroy JH, Lee K-S, Roukema H, Skidmore M. Using an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) to assess multiple physician competencies in postgraduate training. Med Teach. 2007;29(2–3):183–191. doi:10.1080/01421590701302290.

- Boursicot KA. Structured assessments of clinical competence. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2010;71(6):342–344. doi:10.12968/hmed.2010.71.6.48450.

- Caines L, Asiedu Y, Dugdale T, Wu H. An interprofessional approach to teaching nutrition counseling to medical students. MEP. 2018;14:10742. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10742.

- Bush CL, Blumberg JB, El-Sohemy A, Minich DM, Ordovás JM, Reed DG, Behm VAY. Toward the definition of personalized nutrition: a proposal by the American Nutrition Association. J Am Coll Nutr. 2020;39(1):5–15. doi:10.1080/07315724.2019.1685332.

Appendix A: Pre-session survey

Students eating habits, knowledge, and comfort giving nutritional information to patients

Your completion of this survey will serve as your consent to participate.

Anonymous ID number __________________________________

Please indicate the gender with which you identify.

• Female

• Male

3. Please indicate the age range you fall into.

• 20–25 years

• 25–30 years

• 0–35 years

• 5–40 years

• > 40 years

4. Please respond to the following items based on how strongly you agree or disagree with each statement:

Appendix B: Post- session survey

Your completion of this survey will serve as your consent to participate.

Anonymous ID number _________________________________

Please respond to the following items based on how strongly you agree or disagree with each statement: