?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Background

Robust evidence has related yellow passion fruit albedo and long turmeric to the metabolic and glycemic control of diabetes.

Aim

To analyze the incremental cost-effectiveness of the flour made from yellow passion fruit albedo versus long turmeric merged with piperine in the glycemic and lipid control of individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Method

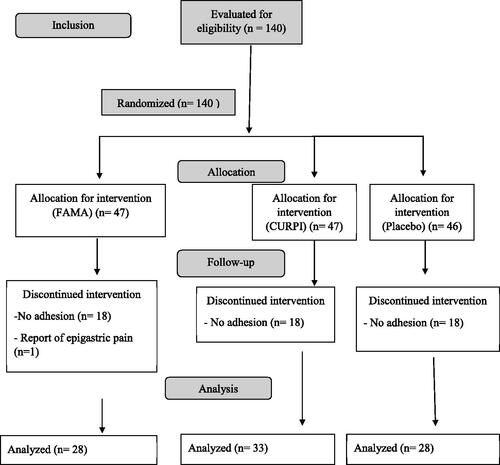

Eighty-nine patients were enrolled in this randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial for 120 days. The first group was prescribed 500 mg capsules, three times a day, of yellow passion fruit albedo flour (FAMA). The second group was prescribed long turmeric capsules (500 mg), merged with piperine (5 mg) (CURPI), at fasting. The third group followed the standard advice recommendations, and ingested a placebo of carboxymethyl cellulose (500 mg) at fasting.

Results

The group using FAMA showed a higher reduction (−5.9%) of glycemia after fasting, compared to placebo (+9%), and CURPI (−3.2%) (p < 0.05). Regarding HbA1c, the study observed a significant and similar statistical reduction (−0.8%) in the intervention groups, in contrast with the placebo group (p < 0.05). The reduction in HOMA-IR in the CURPI group (−9.4%) was higher than the other groups (p < 0.05). The CURPI group also showed a higher reduction of serum triglyceride levels (−20.8%) compared to the placebo (−0.09%) and FAMA (+1.8%) (p < 0.05) groups.

Conclusion

It was concluded that turmeric is the most cost-effective in comparison with yellow passion fruit albedo, because of its decrease in the levels of triglycerides and HOMA-IR, even when adjusted for confounding variables. On the other hand, HbA1c cost-effectiveness relation was similar.

Introduction

Recent socio-demographic data showed that the main nations affected by diabetes mellitus, in reverse order, are the United States, China, India, and Brazil. In these countries, the outcomes of this epidemic are the increase in cases of retinopathy, neuropathy, peripheral vasculopathy, and cardiovascular diseases in the population with diabetes (Citation1).

In the National Health Service in Brazil, the National Policy of Integrative and Complementary Practices has been promoting discussions about the effect of phytotherapy on the glycemic and lipid control of people with diabetes, with no concrete recommendation of the best integrative and complementary practice for these subjects (Citation1–3). To some extent, this occurs because these practices are being used as a therapeutic option of the patients themselves, without a strong recommendation or even solid knowledge from health professionals (Citation4).

On the other hand, the use of simple alternative interventions with low cost in clinical practice is essential for the effective development of prevention actions and health promotion (Citation5). In this context, two choices of interventions have been shown to be effective for metabolic control of diabetes mellitus, flours made from either yellow passion fruit albedo (Passiflora edulis) or turmeric (Curcuma longa), they have also proved to reduce cholesterol levels and insulin resistance (Citation1,Citation6,Citation7). In addition, the flour produced from Passiflora edulis has also demonstrated to be anti-inflammatory (Citation6) and, in animal studies, to increase the levels of High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (Citation8).

Regarding turmeric, it is possible to catalog as therapeutic benefits its antidiabetic and anti-inflammatory properties, resulting in significant decreases in glycemic and lipid values, according to animal studies. These aspects suggest turmeric as a candidate for a natural product for the glycemic control of people with diabetes mellitus (Citation7,Citation9).

In this scenario, it is worth highlighting the incremental cost-effectiveness analysis of these interventions, since this type of analysis is effective for the comparison of two or more therapeutics options and allows an analysis of the clinical benefits, taking into account the costs associated with the treatment. This process supports decision-making in health, consequently, the results are important for health professionals and for the population with the disease that will benefit from the new technologies (Citation5).

The choice of certain interventions to be adopted in several health fields is based on cost analysis, always considering the possible clinical outcomes in a determined population. Accordingly, it is possible to ask the following questions: Which herbal (turmeric merged with piperine [CURPI] or flour made from the yellow passion fruit albedo [FAMA]) shows bioactive compounds with better incremental cost-effectiveness for glycemic and lipid control of people with type 2 diabetes? Are there associations between the use of these herbal medicines and clinical, biochemical, and anthropometric variables of people with type 2 diabetes?

In the current knowledge, based on meta-analysis built over the theme, the existence of a prior investigation that has analyzed the cost-effectiveness of the herbal medicines mentioned in this study is unknown. Bearing this in mind, an investigative possibility is indicated, in the scenario of primary health care, to catalog strong evidence on the glycemic and lipid control of diabetes. This study aimed to analyze the incremental cost-effectiveness during the 4-month period use of the flour made from yellow passion fruit albedo (FAMA) versus turmeric and piperine (CURPI), for glycemic and lipid control of patients with type 2 diabetes.

Methods

Study design

It was a controlled, randomized, and double-blind clinical trial, whose condition was approved by the Ethics Board or Institutional Review Board from the Universidade Vale do Acaraú, Brazil, with approval under n° 2.910.157. The study was also registered in the Brazilian Clinical Trials Registry under record RBR-6r7w8k. This research intervention endured for four months.

The recruitment of subjects for the research proposal occurred in the Units of Primary Health Care from the city of Tabuleiro do Norte, located in the northeast of Brazil, in the year 2019.

Population study

The study considered eligible for this experiment patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes for at least one (1) year, both genders were included, with age of ≥ 18 years, and with previously agreed availability to attend the study’s on-site stages. On the other hand, the patients with the following characteristics were excluded from the research: those under the use of insulin, glucocorticoids, psychotropic, and antineoplastic drugs; in addition to pregnant women and patients affected by any disease that causes immunosuppression; those who self-reported the presence of serious complications due to diabetes (renal failure, blindness or limb amputation); and those with a history of cardiovascular disease or uncontrolled arterial hypertension.

In the calculation of the sample size, the study adopted a model for comparison of the groups according to quantitative variables with the pairing of cases (Citation10).

nP – Number of Pairs.

Zα/2 – Value of the error α, usually: 1.96 (5%).

Z β – Value of the error β, usually: 0.84 (20%).

Sd – Standard Deviation of the difference between pairs.

D – Average of the difference between pairs.

The study adopted the results of glycated hemoglobin dosages (HbA1c) (%) reported in the study of Araújo et al. (Citation3) for this calculation, with approximately 27 participants. Based on this, the sampling of this trial was composed of 89 people with type 2 diabetes, namely, (33 people in the group of turmeric merged with piperine [CURPI] + 28 people in the group of flour made from the yellow passion fruit albedo [FAMA] + 28 people in the placebo group).

The pairing of the participants was made through a previous selection of people with the maximum similarity of characteristics (age, gender, use of antidiabetics, and values of glycated hemoglobin). The first step was to compose the trio of participants and, after this, the execution of a random allocation according to the trio. This stage was conducted after the accomplishment of the baseline stage, when the following information of the participants was gathered: anthropometric, biochemical, arterial blood pressure, and socio-demographic data (gender, age, marital status, religion, education level, family income, job occupation, time of diagnosis, treatment, and presence of comorbidities). This stage was conducted by two nurses qualified by prior training to complete the survey for data collection.

Clinical variables

The outcome variables were those related to glycemic control (venous glycemia after fasting; glycated hemoglobin; homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance [HOMA] IR and β), and lipid index. For this biomarker we have investigated the total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides of people with type 2 diabetes. In addition, distinct predictor variables were analyzed, such as weight, height, body mass index, central adiposity index, waist circumference, hip circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, neck circumference, thigh circumference, and arterial blood pressure.

Intervention

The control group remained under the health care of doctors and nurses, according to the protocols for medications and individualized health education of primary health care centers. On the other hand, the first experimental group received capsules of long turmeric (500 mg) and piperine (5 mg) (CURPI group), once a day, 60 minutes before lunch, in addition to the usual care. The addition of piperine occurred due to its capacity to elevate turmeric absorption patterns (Citation11).

The second experimental group received capsules containing 500 mg of flour obtained from the rind of the yellow passion fruit (FAMA group) to be ingested daily during the three main meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner). In this group, the patient was oriented to ingest 03 capsules of FAMA 60 minutes before the previously referred meals.

The interventions of both groups were conducted for 4 months. During which, the capsules were provided to the patients on adequate recipients, containing a silica sachet (to avoid the humidity from the environment being absorbed by the capsules, with a consequent bias to its therapeutic effects).

During the 4 months of intervention, the researchers scheduled face-to-face meetings with the patients from the referred groups to replenish the capsules for adequate use, ascertain the correct intake of the capsules and resolve any questions about the intervention. The capsules that were distributed and ingested were counted. The patients with a percentage below 75% adherence to the herbal therapy were removed from the study ().

Three face-to-face meetings were performed with the study’s participants, namely, baseline (T0), 60 days of intervention (T60), and 120 days (T120) after the beginning of the intervention. On this occasion, the selected variables in the study were observed again, in order to measure the glycemic and lipid control of T2D.

Analysis of the incremental cost-effectiveness

It is known that cost-effectiveness analysis is developed by confronting certain clinical outcomes with economic costs. In this case, the costs are measured on currency units, and the outcomes on clinical units. The study calculated the ratio of the incremental effectivity cost from the subtraction of the interventions’ costs, divided by the subtraction of the interventions’ effectiveness.

ICER: Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed according to the protocol’s compliance. The difference between the study groups (FAMA, CURPI, and placebo) regarding the sociodemographic variables (sex, skin color, employment status, who lives with them, matrimonial status, and socioeconomic classification) was analyzed using the chi-squared test.

Differences between the study groups at baseline, 60 days, and 120 days were tested using one-way ANOVA for the variables of interest regarding glycemic control (fasting venous blood glucose, glycated hemoglobin, insulin, HOMA Beta, and HOMA-IR), lipid control (low density lipoprotein cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, very low density lipoprotein [VLDL], triglycerides, total cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol), and anthropometric measures (weight, waist, hip, waist-to-hip ratio, thigh, and neck). Differences intragroup at the same point between baseline, 60 days, and 120 days of each group were evaluated by two-tailed paired T-tests according to variables for studying control glycemic, according to the control glycemic, lipid, and anthropometric variables mentioned above. The ANCOVA test was also used for analysis of covariance.

A p value of <0,05 was considered statistically significant. The analyses were processed in the software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 26.0, and Tree Age software.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

In general, the sample was essentially composed of women (78.7% versus 31.3% men), skin color self-referred as brown (59.6%), retired (66.3%), and lived with relatives (83.1%). The mean age for the placebo group was 61.9 years (SD 11.0); for the FAMA group 57.9 (SD 13.2), and for the CURPI 63.2 (SD 11.1).

At baseline, the groups were homogeneous in relation to the socio-demographic and lifestyle variables ( and ).

Table 1. Participants’ characteristics, by intervention group, according to the sociodemographic variables. Tabuleiro do Norte, Brazil, 2019.

Table 2. Comparison of the participants’ anthropometrical variables, by intervention group, over the study. Tabuleiro do Norte, Brazil. 2019.

Effectiveness of the interventions

We observed a significant reduction (p < 0.05) of the neck circumference in all groups, especially in the CURPI group (). Regarding arterial blood pressure, no statistically significant differences were observed between the groups throughout the intervention (p > 0.05).

By ANOVA result, considering multiple comparisons, Bonferroni’s post-test, the comparison of the placebo with the interventions showed the group effect under the fasting venous blood glucose, glycated hemoglobin, and triglycerides with fasting venous blood glucose = [Z (2. 86) = 2.164; p < 0.05]; glycated hemoglobin = [Z (2. 86) = 2.572; p < 0.05], and triglycerides = [Z (2. 86) = 5.687; p < 0.05].

During the intervention, the participants from FAMA showed a higher reduction (5.9%) of fasting venous blood glucose (p < 0.05), while in the placebo group, an increase was observed (p < 0.05).

All groups showed a statistically significant reduction in glycated hemoglobin (p < 0.05) during the interventions. This decrease was similar in the FAMA and CURPI groups (p < 0.05). It is worth noting that participants from CURPI showed a reduction in HOMA-IR of approximately 9% at the end of the intervention, when compared to baseline (p < 0.05) ().

Table 3. Comparison of the Variables related to the participants’ glycemic control, by intervention group, over the study. Tabuleiro do Norte, Brazil. 2019.

The participants from CURPI, when compared to those from FAMA, showed a significant reduction in very low-density lipoprotein and triglycerides levels. The group taking turmeric had 4 times more very low-density lipoprotein and 10 times more triglycerides (p < 0.05). In addition, the CURPI group showed a significant reduction in non-HDL cholesterol in comparison to the other groups (p < 0.05) ().

Table 4. Comparison of the variables related to the participants’ lipid control, by intervention group, during the study. Tabuleiro do Norte, Brazil. 2019.

ANCOVA analysis revealed that there is an effect of the covariable age on fasting glucose and triglycerides [F (1, 76) = 6,960; p < 0.05]. When other covariates were analyzed (sex, physical exercise, smoking, alcoholism, comorbidities, dyslipidemia, BMI, hypertension, and time of diagnosis) the results of the outcomes were not influenced.

Incremental cost-effectiveness of the interventions

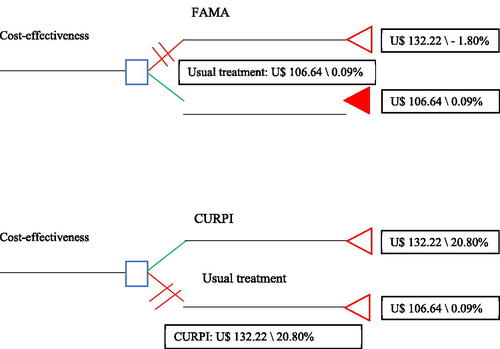

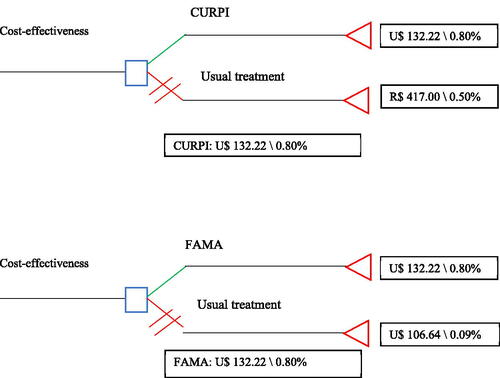

The FAMA and CURPI interventions cost U$133.25 dollars, meanwhile, the usual treatment in the public health care cost, at the time of the data collection, U$10,750 dollars. Based on this, the decision tree showed itself to have similar cost-effectiveness in the control of glycated hemoglobin between the FAMA and CURPI groups, but superior to the placebo group ( and ).

Discussion

Medical treatment of chronic diseases, especially type 2 diabetes, is key to nutrition. However, only a few studies have evaluated the clinical impact and cost-effectiveness of nutrition in the treatment of diabetes. Previous data show that this intensive nutritional therapy is more cost-effective for reducing weight, blood pressure, and glycated hemoglobin (0.7–2%) of hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes compared to basic clinical therapy. Therefore, drugs should be used when dealing with the failure of this initial therapy (Citation11,Citation12). Nevertheless, meta-analysis results suggest that medication adherence intervention is, regarding cost-effectiveness, superior to diet and exercise interventions, from the payer perspective (Citation13).

In the case of diabetes, nutritional interventions have satisfactory cost-effectiveness, but the Mediterranean diet and the change in lifestyle (diet and physical activity) perform better for each year of life they provide to the person with diabetes (Citation14). Computational modeling data show that by replacing only a specific nutritional meal for diabetes, without changing the price, it is already possible to spend less and be more effective than the usual care with this disease. Also, a diabetes-specific nutritional meal replacement has incremental cost-effectiveness of U$47,917 (Citation15).

In this research, the analysis of cost-effectiveness is an important strategy to be applied in the field of health sciences, however, this kind of approach involving interventions comparing FAMA (flour made from yellow passion fruit albedo) and CURPI (turmeric and piperine) has not yet been investigated. Therefore, this can be considered a significant shortcoming, once these interventions deal with common herbal medicines and with low cost in the family’s routine with possible impact on the economy at the governmental level (Citation16).

A prior meta-analysis had already found superiority in the effectiveness of turmeric in comparison to passiflora (yellow passion fruit albedo) in glycemic control (Citation17). However, in the current study, the cost-effectiveness was similar between the CURPI and FAMA groups. This may be because piperine was added to the turmeric, as discussed further below.

One of the main challenges in the use of turmeric in clinical practice is its low solubility in water and bioavailability after its oral administration. This is due to its instability in the intestinal pH and quick metabolism (Citation18). Already considering this fact, the addition of piperine to the turmeric was considered to make a better absorption pattern. In a study performed by Panahi et al., (Citation19) for the evaluation of the antioxidant effects on people with type 2 diabetes, curcuminoids (1000 mg) were used along with the association with 10 mg of piperine, thus verifying their properties of better absorption of turmeric and consequent increase in bioactive functions. In the current study, 5 mg of piperine was used, which represents 50% of the value used in another study with type 2 diabetes, but it showed significant results.

Piperine possesses the capacity to inhibit turmeric glucuronidation in the liver, increasing its bioavailability. Some data show an elevation of up to 2,000% (Citation18,Citation19). It is believed that this is directly related to the effects of the CURPI group on FAMA.

Regarding the usual treatment, 65.2% of the participants were in use of sulphonylurea and 84.3% of biguanide, which stimulates the production of insulin and the reduction of glycolysis production. The interventions made with FAMA, which possesses the action to reduce insulin resistance; and CURPI, which possesses the inhibition of a few enzymes related to type 2 diabetes such as α-glucosidase, added to their effects to generate the results found for the glycemic and lipid parameters (Citation20).

Moreover, among people with type 2 diabetes, it has been established that the use of curcuminoids decreases the free fatty acids, glycated hemoglobin, and triglycerides through the decrease of carrier proteins of adipocyte fatty acids. The authors hypothesize that the inhibition of this protein by turmeric reduces the liberation of fatty acids through adipocytes, and elevates peripheral glucose oxidation or modulates oxidative stress and inflammation (Citation21). Both characteristics directly benefit the metabolic control of people with type 2 diabetes.

Regarding the anthropometric variables, the findings of the neck circumference group showed an alteration of 0.4% in the CURPI group compared to the FAMA group. There is still no scientific evidence that underlies the effects of herbs on this variable, however, there are data showing their correlation with type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease risk, and markers of metabolic syndrome (Citation22–27). Moreover, neck circumference is related to other measures of obesity and fat distribution, both of which are associated with insulin resistance. Therefore, neck circumference may be useful in the clinical tracking of people with an increased risk of insulin resistance.

When the biochemical variables were analyzed, there were significant alterations related to venous glycemia after fasting, glycated hemoglobin, and HOMA beta IR between the studied groups. Regarding the fasting blood glucose, the FAMA group showed higher effectiveness, with a decrease of 5.9%. In turn, both groups, CURPI and FAMA, showed a decrease of 0.8 in the glycated hemoglobin variable. Regarding the HOMA beta IR index, the highest decrease occurred in the CURPI group, 9.4%.

In people with type 2 diabetes, the use of curcuminoids for three months leads to a significant decrease in glycemia after fasting and glycated hemoglobin, in addition to HOMA beta IR. This is due to the decrease in serum-free fatty acids that promote oxidation (Citation6,Citation21,Citation28).

Passiflora edulis is also capable of producing a reduction in the levels of glycemia after fasting, glycated hemoglobin, and HOMA beta IR. The explanation for this fact is the presence of pectin, which is capable of decreasing the time of gastric emptying, increasing satiety, and slowing the absorption of simple carbohydrates (Citation1).

From the albedo of Passiflora edulis, one produces an edible flour, which possesses some properties, namely the slowing of gastric emptying and intestinal traffic, the decrease in resistance to insulin, and the positive action in glycemic control, in addition to the reduction of body inflammation and higher triglyceride blood (Citation1,Citation6).

Regarding the lipid profile, the interventions were also effective. The FAMA group had an increase of 10.8% in the level of high-density lipoprotein. The CURPI group reduced low-density lipoprotein by 18.9%, very low-density lipoprotein by 29.7%, and triglycerides by 20.8%. In a study conducted by Adibian et al. (Citation29), the serum level of cholesterol decreased significantly (p < 0.01) in the group using curcumin, as well as the average concentration of reactive protein, which predicts a decrease in complications by the reduction of the triglycerides level. This fact is verified in both glycemic and lipid control with a positive bias to people with prediabetes (Citation30).

The literature indicates that Passiflora edulis has the capacity to decrease visceral and subcutaneous fat, and the adiposity index. Therefore, it is associated with the improvement of the antioxidant capacity and with the reduction in the levels of malondialdehyde, thus improving the lipid profile of obese people (Citation2,Citation31).

Supplementation with yellow passion fruit albedo significantly reduces the levels of glucose after fasting, and triglycerides (Citation31). A study performed in Wistar rats with the use of Passiflora edulis juice showed a decrease in the levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein, in addition to a significant increase in the levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (Citation8).

In other conditions, Passiflora can decrease the concentration of reactive substances to thiobarbituric acid, which indicates lipid peroxidation, showing benefits for the lipid profile (Citation8). The reduction of cholesterol and lipids may be associated with the excretion of lipids and bile acids in the feces, due to the rich fraction inside soluble fiber (Citation30).

Regarding turmeric, although its action in the decrease of lipids is common it requires further explanation. The most accepted hypothesis considers that the herb works in the reduction of phytosterol cholesterol (Citation4,Citation11,Citation32). Moreover, it is known that the ingestion of CURPI is considered an alternative for homeostasis of lipids and glucose in people who suffer with hypercholesterolemia (Citation33).

When analyzed under the optic of variations from glycated hemoglobin, FAMA and CURPI have comparable incremental cost-effectiveness, thus, the use of one or the other intervention is indifferent. This fact prompted the need to analyze triglycerides and glycated glycemia. For these variables, CURPI was more cost-effective, which demonstrates its plausibility for clinical application. It is important to highlight that the placebo group also showed a significant reduction in glycated hemoglobin over the study period. It is believed that this is due to the Hawthorne effect; in other words, as these patients were receiving care (placebo) and being accompanied (measurements), in addition to the ones made available by the primary care service, they felt motivated to engage in self-care against diabetes.

It was verified in a controlled clinical trial that turmeric, when ingested by people with type 2 diabetes, reduces glycated hemoglobin and improves the total score of neuropathy, reflex, and body temperature, which affect important cellular events in the inflammatory process (Citation29,Citation34–37). Moreover, in a scientific review that included 39 clinical trial studies, it was shown that there is effectiveness for the control of glycated hemoglobin, but, due to the scarcity of studies that approached the subject in a more specific way, its administration on people with type 2 diabetes should be further analyzed (Citation37).

The current study not only accomplished clinical intervention to verify the lipid and glycemic functions produced by FAMA and CURPI, but also analyzed which intervention was most cost-effective. When considering all factors, it was concluded that the intervention with CURPI was more cost-effective. Based on the results of this research, it is possible to discuss the financial economy in the treatment of type 2 diabetes of approximately 77.3 American dollars, per person, which may be applied in some countries that adopt a health system similar to the one in Brazil. To date, no studies have reached our results when it comes to dealing with the incremental cost-effectiveness of these interventions. Furthermore, participants did not report any adverse events during the interventions, thus presenting the study as effective for the determination of a better glycemic and lipid profile.

Regarding the study’s limitations, there were a few drop-outs in the follow-up related to noncompliance with the prescribed treatment. This interfered with the homogeneity of the groups in the baseline stage for some dependent variables. The baseline data refer to participants who completed all stages of the clinical trial. That is, in the beginning, these groups were homogeneous in all variables under study, but with the drop-outs throughout the experiment, the groups started to show differences concerning the variables fasting blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin. Despite this fact, the intervention lasted four months, which may have implied not observing possible changes or a cohort point of specific control for the studied population.

Conclusion

The turmeric merged with piperine showed a better incremental cost-effectiveness when compared to the yellow passion fruit albedo, for the decrease in the levels of serum triglycerides and insulin resistance, estimated by the HOMA-IR. On the other hand, for glucose control, the albedo flour made from the passion fruit was more effective. Both the analyzed alternative interventions are feasible for application in clinical practice, especially for people with type 2 diabetes who are being accompanied in clinical practice.

Acknowledgment

All patients and health professionals who took part in this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- de Queiroz M. d S R, Janebro DI, da Cunha MAL, Medeiros J. d S, Sabaa-Srur AUO, Diniz M. d F F M, Dos Santos SC. Effect of the yellow passion fruit peel flour (Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa deg.) in insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Nutr J. 2012;11(1):89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-11-89.

- Panelli M, Pierine D, de Souza S, Ferron A, Garcia J, Santos K, Belin M, Lima G, Borguini M, Minatel I, et al. Bark of passiflora edulis treatment stimulates antioxidant capacity, and reduces dyslipidemia and body fat in db/db mice. Antioxidants. 2018;7(9):120. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox7090120.

- de Araújo MFM, Veras VS, de Freitas RWJF, de Paula M. d L, de Araújo TM, Uchôa LRA, Gaspar MWG, Cunha M. d C d S O, Serra M. A A d O, Carvalho C. M d L, et al. The effect of flour from the rind of the yellow passion fruit on glycemic control of people with diabetes mellitus type 2: a randomized clinical trial. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2017;16(1):18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40200-017-0300-z.

- Thota RN, Acharya SH, Garg ML. Curcumin and/or omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation reduces insulin resistance and blood lipids in individuals with high risk of type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Lipids Health Dis. 2019;18(1):31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-019-0967-x.

- Moraz G, Garcez A, da S, Assis EM, de Santos JP, dos Barcellos NT, Kroeff LR. Estudos de custo-efetividade em saúde no Brasil: uma revisão sistemática. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2015;20(10):3211–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-812320152010.00962015.

- Silva DC, Freitas ALP, Pessoa CDS, Paula RCM, Mesquita JX, Leal LKAM, Brito GAC, Gonçalves DO, Viana GSB. Pectin from Passiflora edulis shows anti-inflammatory action as well as hypoglycemic and hypotriglyceridemic properties in diabetic rats. J Med Food. 2011;14(10):1118–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2010.0220.

- Hussain N, Hashmi A-S, Wasim M, Akhtar T, Saeed S, Ahmad T. Synergistic potential of Zingiber officinale and Curcuma longa to ameliorate diabetic-dyslipidemia. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2018;31(2):491–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29618440

- de Souza M. d S S, Barbalho SM, Damasceno DC, Rudge MVC, de Campos KE, Madi ACG, Coelho BR, Oliveira RC, de Melo RC, Donda VC, et al. Effects of Passiflora edulis (yellow passion) on serum lipids and oxidative stress status of wistar rats. J Med Food. 2012;15(1):78–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2011.0056.

- Shengule S, Kumbhare K, Patil D, Mishra S, Apte K, Patwardhan B. Herb-drug interaction of nisha amalaki and Curcuminoids with metformin in normal and diabetic condition: a disease system approach. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;101:591–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2018.02.032.

- Miot HA. Tamanho da amostra em estudos clínicos e experimentais. J Vasc Bras. 2011; 10(4):275–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/S1677-54492011000400001.

- Jantarat C, Sirathanarun P, Boonmee S, Meechoosin W, Wangpittaya H. Effect of piperine on skin permeation of curcumin from a bacterially derived cellulose-composite double-layer membrane for transdermal curcumin delivery. Sci Pharm. 2018;86(3):39. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm86030039.

- Youn-Yun C, Moon-Kyu L, Hak-Chul J, Mi-Young R, Ji-Young K, Young-Mi P, Cheong-Min P. The clinical and cost effectiveness of medical nutrition therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Koren J Nutr. 2020;41(2):147–55. Available from: https://www.koreascience.or.kr/article/JAKO200817848807391.pdf

- Nerat T, Locatelli I, Kos M. Type 2 diabetes: cost-effectiveness of medication adherence and lifestyle interventions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:2039–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S114602.

- Dalziel K, Segal L. Time to give nutrition interventions a higher profile: cost-effectiveness of 10 nutrition interventions. Health Prom Intern. 2007; 22(4):271–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dam027.

- Randolph S, Mustad VA, Lee J, Sun J. Economic analysis of a diabetes-specific nutritional meal replacement for patients with type 2 diabetes. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2010;19(1):1–7.

- Manukumar HM, Shiva Kumar J, Chandrasekhar B, Raghava S, Umesha S. Evidences for diabetes and insulin mimetic activity of medicinal plants: present status and future prospects. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57(12):2712–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2016.1143446.

- Sousa DF, Veras VS, Freire VECS, Paula ML, Serra MAAO, Costa ACPJ, da Conceição S.O. Cunha M, Queiroz MVO, Damasceno MMC, Paes FER, et al. Effectiveness of passion fruit peel flour (Passiflora edulis L.) versus turmeric flour (Curcuma longa L.) on glycemic control: systematic review and meta-analysis. CDR. 2020;16(5):450–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.2174/1573399815666191026125941.

- Scholze AFA. Biodisponibilidade da curcumina. Rev Bras Nutrição Clin Funcional. 2014; 14(60):20–4. Available from: https://www.vponline.com.br/portal/noticia/pdf/6b7cfcab701afeeb7e0f4701b5c5920b.pdf.

- Panahi Y, Khalili N, Hosseini MS, Abbasinazari M, Sahebkar A. Lipid-modifying effects of adjunctive therapy with curcuminoids-piperine combination in patients with metabolic syndrome: results of a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22(5):851–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2014.07.006.

- Golubic R, Wijndaele K, Sharp SJ, Simmons RK, Griffin SJ, Wareham NJ, Ekelund U, Brage S, ProActive Study Group. Physical activity, sedentary time and gain in overall and central body fat: 7-year follow-up of the ProActive trial cohort. Int J Obes (Lond). 2015;39(1):142–8. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/ijo201466 doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2014.66.

- Lekshmi PC, Arimboor R, Indulekha PS, Menon NA. Turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) volatile oil inhibits key enzymes linked to type 2 diabetes. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2012;63(7):832–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/09637486.2011.607156.

- Yang G-R, Yuan M-X, Wan G, Zhang X-L, Fu H-J, Yuan S-Y, Zhu L-X, Xie R-R, Zhang J-D, Li Y-L, et al. Association between neck circumference and the occurrence of cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes: Beijing Community Diabetes Study 20 (BCDS-20). Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:1–6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6925677/pdf/BMRI2019-4242304.pdf doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4242304.

- Na L-X, Li Y, Pan H-Z, Zhou X-L, Sun D-J, Meng M, Li X-X, Sun C-H. Curcuminoids exert glucose-lowering effect in type 2 diabetes by decreasing serum free fatty acids: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57(9):1569–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201200131.

- Almeida-Pititto B, Silva IT, Goulart AC, Fonseca MIH, Bittencourt MS, Santos RD, Blaha M, Jones S, Toth PP, Kulakarni K, ELSA Research Group, et al. Neck circumference is associated with non-traditional cardiovascular risk factors in individuals at low-to-moderate cardiovascular risk: cross-sectional analysis of the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2018;10(1):82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-018-0388-4.

- Bochaliya RK, Sharma A, Saxena P, Ramchandani GD, Mathur G. To evaluate the association of neck circumference with metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk factors. J Assoc Physicians India. [Internet]. 2019;67(3):60–2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31304708

- Alzeidan R, Fayed A, Hersi AS, Elmorshedy H. Performance of neck circumference to predict obesity and metabolic syndrome among adult Saudis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Obes. 2019;6(1):13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40608-019-0235-7.

- Ozkaya I, Yardimci B, Tunckale A. Appropriate neck circumference cut-off points for metabolic syndrome in Turkish patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocrinol Diabetes y Nutr. 2017;64(10):517–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.endinu.2017.07.006.

- Derosa G, Catena G, Raddino R, Gaudio G, Maggi A, D'Angelo A, Maffioli P. Effects on oral fat load of a nutraceutical combination of fermented red rice, sterol esters and stanols, curcumin, and olive polyphenols: a randomized, placebo controlled trial. Phytomedicine. 2018;42:75–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2018.01.014.

- Adibian M, Hodaei H, Nikpayam O, Sohrab G, Hekmatdoost A, Hedayati M. The effects of curcumin supplementation on high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein, serum adiponectin, and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Phyther Res. 2019;33(5):1374–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6328.

- Poolsup N, Suksomboon N, Kurnianta PDM, Deawjaroen K. Effects of curcumin on glycemic control and lipid profile in prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0215840. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215840.

- Corrêa EM, Medina L, Barros-Monteiro J, Valle NO, Sales R, Magalães A, Souza FCA, Carvalho TB, Lemos JR, Lira EF, et al. The intake of fiber mesocarp passion fruit (Passiflora edulis) lowers levels of triglyceride and cholesterol decreasing principally insulin and leptin. J Aging Res Clin Pract. 2014;3(1):31–5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25346913

- Chau C-F, Huang Y-L. Effects of the insoluble fiber derived from Passiflora edulis seed on plasma and hepatic lipids and fecal output. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2005;49(8):786–90. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15995986 doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.200500060.

- Ferguson JJA, Stojanovski E, MacDonald-Wicks L, Garg ML. Curcumin potentiates cholesterol-lowering effects of phytosterols in hypercholesterolaemic individuals: a randomised controlled trial. Metabolism. 2018;82:22–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2017.12.009.

- Sheng X, Che H, Ji Q, Yang F, Lv J, Wang Y, Xian H, Wang L. The relationship between liver enzymes and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Horm Metab Res. 2018;50(05):397–402. doi:https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0603-7899.

- Asadi S, Gholami MS, Siassi F, Qorbani M, Khamoshian K, Sotoudeh G. Nano curcumin supplementation reduced the severity of diabetic sensorimotor polyneuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized double-blind placebo- controlled clinical trial. Complement Ther Med. 2019;43:253–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2019.02.014.

- Rondanelli M, Klersy C, Terracol G, Talluri J, Maugeri R, Guido D, Faliva MA, Solerte BS, Fioravanti M, Lukaski H, et al. Whey protein, amino acids, and vitamin D supplementation with physical activity increases fat-free mass and strength, functionality, and quality of life and decreases inflammation in sarcopenic elderly. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(3):830–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.113357.

- Rezaeiamiri E, Bahramsoltani R, Rahimi R. Plant-derived natural agents as dietary supplements for the regulation of glycosylated hemoglobin: a review of clinical trials. Clin Nutr Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0261561419300585.