Abstract

Parental involvement is a cornerstone of success in supporting children with behavioral differences. However, having professionals provide intensive training to all parents in need of assistance is unattainable in many areas. The pyramidal parent training approach, where parents train other parents after first being trained by experts, supports generalization, collaboration, and makes training accessible in places where professional services are not available. A literature review was conducted to determine the scope of research on pyramidal parent training for families with children with ASD or another developmental disability. Eight relevant articles and one thesis were found. This research synthesized their training components, settings, foci, participants, designs, outcomes, social validity, and cultural responsiveness. Despite the many differences between the studies, two distinct forms of pyramidal parent training were identified: (1) Parent Training within a Family and (2) Parent Training among Families. The results show that regardless of the model, parent participants increased their skill acquisition to a similar degree whether trained by a professional or another parent. However, limited data were presented on the changes in the children’s behaviors and shortcomings were found in the areas of outcomes, generalization, maintenance, and cultural responsiveness.

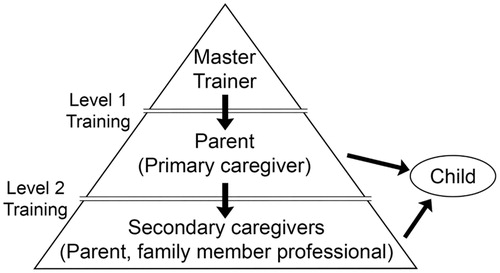

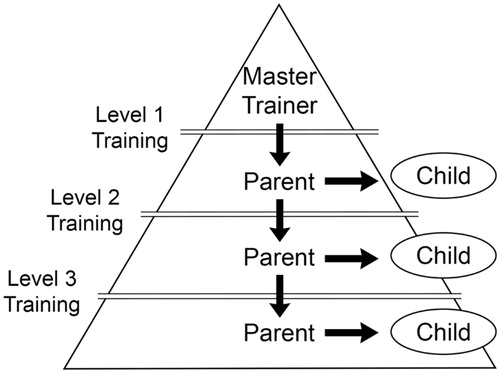

Adequate training for parents and other caregivers is an essential component in the delivery of evidence-based services for individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). As discussed by Loughrey et al. (Citation2014), evidence-based intervention delivered by parents significantly reduces the costs, without decreasing the intensity and quality of treatment. Making cultural adaptations when training parents increases the fit of the intervention (Castro et al., Citation2004). However, interventions that consider cultural responsiveness are not necessarily available to diverse groups of parents in locations with financial and resource constraints. Pyramidal parent training, which involves professionals first training a caregiver or group of caregivers (referred to as Level 1 training) who subsequently train other caregivers (referred to as Level 2 training), may be used to overcome some of the barriers. Pyramidal approaches decrease the amount of time and effort required for training and increase community capacity and sustainability (Reid & Fitch, Citation2011). Despite the apparent value of using pyramidal parent training to support families of children with ASD and other developmental disabilities, little research has been done to identify the specific methods, essential components, cultural competence, and limitations of the approach.

Parent training

Engaging parents and other caregivers as direct service providers for their children increases the quality and availability of services (Symon, Citation2005). As the demand for effective behavior services exceeds its availability in many communities, children often go without the needed professional support. Besides, school-based or therapist-based intensive services are costly, which further restricts access (Johnson et al., Citation2018). Parent training could overcome such a barrier, because it is a time-limited approach, usually including ten to twenty sessions, delivered in brief format (i.e., one to one and a half hour a week), requires less overall service hours with a professional, and is considerably less costly (Johnson et al., Citation2018). As parents and other family members take up part of the work, a generalization of treatment across people as well as settings is often acquired. Moreover, when parents become educated about ASD and trained in the skills needed to support their children, their confidence is enhanced, and stress levels reduced (Keen et al., Citation2010).

Parent training benefits could be crucial in areas where professionally led intervention is not available. Parents could effectively take over therapists’ roles and implement a variety of behavioral, social, and communication programs for their children (Symon, Citation2005). For the training to be effective and produce meaningful change in the behavior of parents as well as their children, it should use evidence-based techniques (Reid & Fitch, Citation2011). However, the use of evidence-based practices alone is not sufficient. As discussed by Lau (Citation2006), evidence-based treatments may need to include cultural adaptations (e.g., contextualizing content or enhancing engagement) that are prepared for use with diverse populations, result in practices suited for real-world settings, and support community engagement.

Evidence based practices in parent training

The most commonly used evidence-based parent training methods include demonstration and role-play, video modeling, and active coaching. Sometimes, didactic instructions are also added. These methods can stand alone, or be used in various combinations.

Demonstrations, also sometimes referred to as modeling, occur when the trainer demonstrates the targeted behavior to the parent. It is often used as the first step in multicomponent training packages. What usually follows are role-plays, where the parent performs the same target behavior with a confederate representing the child (Leaf et al., Citation2015). The combination of demonstration and role-play are components of Behavioral Skills Training (BST), which is one of the most commonly used approaches to training professionals and parents. It includes an oral presentation, modeling, role-play, and feedback (Parsons et al., Citation2012).

Next to role-play, some authors also describe skill rehearsals as an independent training technique (Andzik & Cannella-Malone, Citation2017). Even though sometimes used interchangeably, Burnard (Citation2013) calls attention to their differences. Skill rehearsal involves one or more people practicing a selected skill or set of skills during training. In a role-play scenario, the practice happens in a contrived context, where one person acts as a parent, while the other pretends to be the child.

An additional technique often used in parent training is active coaching (Leaf et al., Citation2015). It is composed of coaching and delivering feedback while the trainee demonstrates the targeted skill. Usually, it is provided by a professional therapist who observes a parent delivering an intervention to a child and immediately corrects any instances of deviation from the proper procedure (Adubato et al., Citation1981; Bruder & Bricker, Citation1985; Kuhn et al., Citation2003).

Evidence-based training methods used with parents are delivered in a one-to-one, group, or telehealth instructional format. While one-to-one and group formats are valuable, providing training to diverse and far-reaching areas can pose a challenge. Telehealth may be useful in bridging the systemic shortages of ASD treatment providers in some geographical regions and bringing together parents and training providers across distances (Leaf et al., Citation2015). However, it does come with its own set of technological and resource availability challenges.

Pyramidal training

Pyramidal training involves training multiple tiers of people (e.g., Tier 1 participants train Tier 2 participants). The research on pyramidal training goes back to the 1970s (Whalen & Henker, Citation1971). One of the first studies, which used the pyramidal approach to train staff working in an institutional setting for individuals with disabilities, was conducted by Page and colleagues in 1982. Three supervisors were trained by experts to teach skills, which could improve the use of instructions, prompts, and consequences. These supervisors then trained 45 members of the direct care staff, who subsequently applied the skills in their work with individuals described as being multiply handicapped with limited language skills and mobility. The results showed that providing training and feedback to the supervisors had a positive effect on the direct care staff, as their correct teaching behaviors substantially increased. The study also showed some of the weak points of the pyramidal training model. First, the skills taught to direct care staff in one area of training (communication) did not generalize to other areas (gross motor skills). Second, the training had only a limited effect on the behaviors of the clients. Page et al. (Citation1982) argued that one of the reasons for the small gains in clients’ behaviors might have been the study’s timeframe, as it was too short to detect any changes.

Andzik and Cannella-Malone (Citation2017) conducted a systematic review of the literature on pyramidal staff training. Fourteen studies published between 1983 and 2014 met their inclusion criteria. The studies focused on training staff who worked with individuals with intellectual disabilities, developmental disabilities, and autism. They learned that the pyramidal training approach could be used in a variety of settings, including residential institutions, group homes, adult day facilities, and schools to teach a wide range of skills to diverse participants. The skills taught included a spectrum of evidence-based practices (e.g., preference assessment, functional analysis, positive feedback, and interaction skills). The participants, who were trained in the pyramidal fashion included supervisors, teachers, assistants, direct care staff, and in the case of two studies, parents. Their results show that pyramidal training is a promising practice, which leads to the development of practitioners’ skill sets needed for intervention. However, due to the lack of data on training and implementation of the new skills, as well as missing information about the performance of individuals with disabilities, it is not clear whether pyramidal staff training directly led to positive outcomes for the clients.

Even though two of the studies reviewed by Andzik and Cannella-Malone (Citation2017) included parents, they were not the focus of the review. As the authors pointed out, their review did not target any specific settings, practitioners, or clients. They suggested that future researchers should consider a more targeted search and review of literature focused on specific populations or elements of training.

Parents are a specific population participating in pyramidal trainings since the 1980s. Pyramidal parent training involves parents training other parents or caregivers. It is sometimes also described as parent-to-parent or peer-parent training. A literature review focused on parents training other parents or caregivers of children with ASD has not been previously conducted. While evaluating the components and rigor of research on pyramidal parent training supports the goal of future research in a needed area, it does not paint a complete picture of how parents are being treated when part of training and research. This is an especially important consideration given the intensely intimate nature of parent training and the need for validation of evidence-based practices in diverse settings.

Culturally responsive research

Working with families to provide training and support can be a challenge for professionals and researchers. To maximize the social validity of behavior change in parents and their children, the issue of cultural responsiveness should be considered. Cultural responsiveness is a broad construct focused on recognizing and incorporating the cultural experiences, perspectives, and characteristics of others (Gay, Citation2002). Cultural responsiveness in practice may include such strategies as: Enhancing practitioners’ knowledge of other cultures, enhancing practitioners’ cultural self-awareness, acknowledging families’ cultures, training skills that are culturally relevant to them, and using culturally valid testing tools (Vincent et al., Citation2011). As discussed in the works of Lau (Citation2006) and Baumann and colleagues (Citation2015), taking these steps to make evidence-based parent training practices culturally relevant is imperative to addressing the needs of diverse families. Within the area of parent training, in both research and practice, specific steps should be taken to ensure that professionals working with families do the following: Develop cultural awareness and knowledge of self, recognize the importance of diversity, employ constructs of multiculturalism, conduct culture-centered research with diverse populations, and apply culturally-appropriate skills (APA, Citation2003, Citation2010). Additionally, culturally relevant interventions clearly incorporate the cultural differences, historical struggles, and systemic problems faced by the families in the process of development and application. When research is shared on these trainings, the foundations of cultural responsiveness should be evident in the investigation, interaction, and reporting (Bal & Trainor, Citation2016). Research on pyramidal training, which deals with the behaviors of parents and children in their homes, should be grounded in cultural responsiveness, use evidence-based practices that have been adapted for the context, take a client-centered approach, and be driven by local norms and values.

Therefore, given the absence of an in-depth examination of pyramidal parent training, looking at rigor, expanse, and culturally competent practices, this review investigated:

How effective is the pyramidal training approach when used with parents of children identified with, or at-risk for, ASD or another developmental disability?

What methods and techniques can be successfully used in pyramidal parent training?

How is treatment integrity controlled within pyramidal parent training?

How have the research approaches evaluating pyramidal parent training incorporated culturally responsive practices?

Methods

Inclusions and exclusions criteria

A comprehensive search of scientific databases covering professional peer-reviewed publications in the area of psychology, education, medicine, and related fields was conducted. A gray literature search consisting of theses and dissertations was also added in an effort to include the maximum number of studies on pyramidal parent training. The review included only studies published in the English language between January 1980 and February 2020.

To be included, studies had to meet the following minimum criteria. First, an expert trainer had to train a parent in specific behavioral skills (Level 1 training). The parent, who was trained by the professional became a parent trainer (Tier 1 parent) and subsequently trained other parents or caregivers (Tier 2 parents) in the use of the same procedures (Level 2 training). Training further tiers of parents or caregivers was optional. Tier 1 and Tier 2 parents or caregivers had to use the newly acquired skills with children identified with, or at-risk for, ASD or another developmental disability. Direct observation of parents implementing the newly acquired skills at their homes or other settings was not a necessary prerequisite for study inclusion. As the second criterion, the studies had to include either single-subject, group experimental or pre-experimental design (e.g., RTC, one group pretest-posttest design, or multiple-baseline design). They also needed to present the results either in a visual form (bar charts, line graphs, cumulative records, or standard celeration charts) or as statistical analysis.

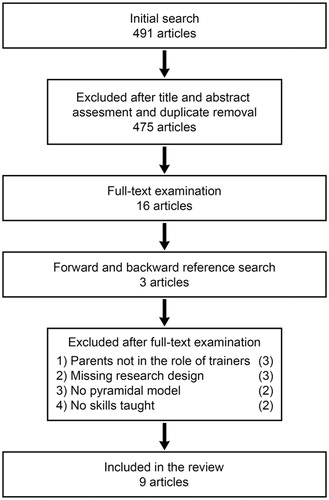

Criteria for exclusion from the review included the following: (a) the study did not involve parents in the role of trainers of others; (b) the study did not utilize experimental research design; (c) the study did not include a standard pyramidal model (e.g., parents participated only as assistants of professionals training other parents); (d) the study only evaluated a general parent education program. The search and selection procedures are illustrated in .

Search method

The databases Academic Search Complete, PsycINFO, ProQuest, and PubMed were searched. Google Scholar was referenced as a complementary source. The online Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations database was used for a comprehensive search of pyramidal parent training research published before March 2020. A forward and backward citation search was conducted using SCOPUS and the Web of Science. The terms used while searching the electronic databases included the following: (parent* OR spouse* OR caregiver*) AND (pyramid* OR train-the-trainer OR) AND (pervasive develop* OR autis* OR disab* OR handicap* OR retard* OR at-risk); given the comprehensive nature of the search, even previously relevant terms were included.

The initial systematic search returned 491 journal articles, dissertations, and theses. First, the title and abstract of each of the texts were reviewed. Sixteen studies were selected for a more refined full-text assessment. These articles were also used for the forward and backward search, which brought in another three articles with promising titles and abstracts. A total of 18 articles and one thesis were screened in and their full-texts downloaded. After reviewing the 19 full-texts, a further ten studies were excluded for the following reasons: (1) Three studies did not involve parents in the role of trainers of other parents. (2) Another three excluded studies utilized non-experimental research designs or did not include a research design at all. (3) A further two studies were excluded as they did not include a standard pyramidal model. (4) Finally, two studies evaluated only general parent to parent education programs.

Extraction of data

First, information was extracted from the selected studies related to participant characteristics and demographics, namely (a) professional (master) trainer characteristics, (b) information about parent trainers and parent trainees in all levels of training, (c) description of the children receiving intervention from their parents, and (d) information about the training and intervention settings. Second, information was extracted about (a) training components and practices, (b) methods and techniques used, (c) fidelity of training implementation, (d) materials used, and (e) training main focus. Third, information was extracted about the study research design. Data were specifically collected about (a) the experimental design, (b) skills to be taught to trainees, (c) outcomes for the children, (d) reports about maintenance and generalization, as well as (e) interobserver agreement (IOA), and (f) social validity measures. Fourth, training and intervention results were assessed by reviewing the reported outcomes.

Culturally responsive research evaluation

Following the extraction of the data the studies were systematically reviewed using the Culturally Responsive Research (CRR) Rubric. The CRR Rubric was developed by Trainor & Bal in 2014 based on their systematic review of the literature, consultation with experts, and work piloting the rubric (Trainor & Bal, Citation2014; Bal & Trainor, Citation2016). The rubric is built upon existing tools for assessing research quality (e.g., Gersten et al., Citation2005) but is not aimed at assessing commonly accepted indicators and standards of research (e.g., experimental design or internal validity). Rather, the focus is specifically on the culturally responsive component. The 15-item rubric, through the lens of cultural responsiveness, covers the areas of: (1) foundational constructs of the study, (2) relevancy of the research problem, (3) critical and comprehensive review of the relevant literature, (4) justification of the theoretical framework, (5) description of the participants, (6) description of the researchers and the interventionists, (7) description of the sampling procedures, (8) description of the research setting, (9) description of data collection activities, (10) ecology of the intervention, (11) intervention design, (12) assessment of intervention efficacy, (13) presentation of findings, (14) analysis and interpretation, and (15) discussion of dissemination. It uses a three-point Likert scale to rate each component as absent (0), somewhat present (1), or fully present (2). A score of zero (0) represents a culture-blind approach to the construct. A score of one (1) represents an approach to a construct where culture was viewed as a categorical or static variable. A score of two (2) means that documentation was provided to show that an applied focus on cultural and environmental variables was taken for that construct (Trainor & Bal, Citation2014). For complete details on the rubric, its development, and prior usage, please see Trainor and Bal (Citation2014) and Bal and Trainor (Citation2016). The authors elaborated on the original rubric by adding specific examples for each construct. The adapted rubric is available from the authors upon request.

Interrater reliability of rubric evaluation

There were eight articles reviewed using the rubric. The decision was made not to include the thesis (Knecht, Citation2018) in the review since the parameters of problem formation (e.g., literature review and theoretical framework) differ between theses and journal articles. The rubric evaluated 15 components for each article. Therefore, a total of 120 components were evaluated. Interrater reliability was calculated by having the two authors independently score 45 of the evaluated components (37.5%). The reliability was then calculated by dividing the total number of agreements by the total number of agreements and the disagreements and multiplying by 100. The percentage of interrater agreement was 93%.

Results

Overview of the studies and demographics

Two distinct groups of pyramidal parent training studies were identified. The first group focused on providing training to the primary caregiver, typically a mother, who then trained secondary caregivers in the same family. This type of approach was termed: Parent training within a family (see ). The second group of studies focused on parents training other parents. This type of approach was termed: Parent training among families (see ).

Parent training within a family was used in five studies: Adubato et al. (Citation1981), Kuhn et al. (Citation2003), Symon (Citation2005), Loughrey et al. (Citation2014), and Knecht (Citation2018). In this group of studies the majority of the training was conducted within the home, mothers were predominately trained, the trainer was an experimenter or student, the children presented with characteristics of a developmental delay, and a variety of applied teaching skills were targeted. Four of the earlier studies were conducted in the United States, while the most recent article, Knecht (2018), in Southeast Europe with Macedonian and Albanian caregivers.

Parent training among families was used in four studies: Bruder and Bricker (Citation1985), Neef (Citation1995), Hansen et al. (Citation2017), and Conklin and Wallace (Citation2019). Through this approach, the programs were able to reach more families and more children. In this group of studies, none of the training was conducted within the home, the number of parents trained greatly outnumbered the number trained in the first group of studies, the trainer was most often a professional interventionist, the children presented with characteristics of a developmental delay, and theoretical concepts were most often trained. Three of the studies were conducted within the United States, with the Hansen et al. (Citation2017) study being conducted in Southeast Europe with Macedonian caregivers. However, the Conklin and Wallace (Citation2019) study did involve minority caregivers (Hispanic and Chinese).

Further information about all of the reviewed studies including research participants, training type, focus, duration, and settings is provided in .

Table 1. Training participants, type, focus and duration.

Trainers and participants

All parent to parent training studies included an expert trainer providing training to the primary caregiver (Tier 1 parents) at the first level of training (n = 9, 100%). Information about the master trainer was scarce throughout the investigations. Most of them were either the researchers or authors of the studies (n = 4) or other professionals with degrees in behavior analysis or special education (n = 3). Two studies used students of behavioral science as the primary trainers.

In all instances, the master trainer trained parents at Level 1 training. Most of the studies included mothers at the first level of training (n = 5). One study included only fathers, one involved several mothers and one father, and two studies did not specify the gender of parents being trained. At Level 2 training, parent trainers provided training to other parents (n = 5) or secondary caregivers, including fathers, mothers, other family members, or home care providers (n = 4). Only some studies (n = 4) included Level 3 training for parents or other care providers. Between one and six Tier 1 parents participated (M = 3.5) and the same number of Tier 2 care providers joined across the studies. There were between three and six (M = 4) participants in the third level of training.

Only six studies included children as direct participants, although a direct intervention was not part of the study design. The majority of the children in the reviewed studies had the diagnosis of ASD (n = 35). In some cases, no exact diagnosis of the participating children was given, but their behaviors included those often associated with ASD (e.g., hand flapping, screaming, grabbing, hitting, and kicking). As the training of their parents was provided at an autism research and training center, we can assume they were also children with ASD (n = 4). One study included toddlers at-risk of developmental delay (n = 9) and children described as having a developmental disability, ADHD, or speech disorder (n = 7).

Settings

Training of parents as well as intervention delivered to children took place at a variety of locations. Except for the study of Kuhn et al. (Citation2003), who provided all trainings at participants’ homes, instructions of Tier 1 participants were delivered at other locations. These included research or intervention centers associated with universities, university conference rooms, schools, or hotel conference rooms (n = 8).

In the case of Parent training among families, Level 2 and Level 3 trainings were delivered at the same place as Level 1 training (n = 4). Home-based settings were used for the Level 2 and Level 3 trainings in the case of Parent Training Within a Family. The only exception was the study of Knecht (Citation2018), where their husbands trained Tier 2 participating wives at the same conference facility where Level 1 training took place.

After being trained, parents and caregivers delivered the intervention to the children. Their performance was measured only in a classroom in the case of one study. Five studies tested the effects of parent training on children in their homes as well as in clinical settings, and three studies did not include direct work with the children.

Pyramidal training forms and components

Level 1 training (professional to parent)

At Level 1, all studies included a detailed description of the main topics and content of the training. Feedback and coaching were provided to parents in all of the reviewed studies (see ). Modeling was the second most commonly used strategy (n = 7; 78%). In addition to verbal instruction, seven studies (78%) provided parents with written instructions and reading materials in the form of handouts, protocols, or booklets. Skill rehearsal and role-play were utilized in four studies (44%). Five studies (56%) included children as active participants in at least some parts of the training, and four studies assessed fidelity of training procedures implemented by the master trainer.

Table 2. Training components.

Level 2 and 3 training (parent to parent)

Information about the second and third levels of training was provided in much less detail. In two studies (22%) comprehensive training was provided to the parents who became trainers. In two studies (22%) a minimal training overview and written materials were provided to the parents who became trainers. In four studies, parents were asked to use the same approach in training as when they were trained by professionals (44%). In one study, the parent was asked to use any form of training as long as the same procedures were taught.

Parent trainers used feedback and coaching with other parents and caregivers in eight (89%) of the reviewed studies. Modeling was used in six studies (67%), written materials and modeling in six (67%), and skill rehearsal and role play in four studies (44%). Only two studies (22%) provided training on data collection for the further tiers of parents and caregivers. Four studies (44%) included children as active participants in parent to parent training. Five studies (56%) assessed the fidelity of training implementation of the parent trainer while delivering training to other parents.

Research design and measures

The most common type of experimental design used was multiple-baseline across participants and its variations, namely multiple-probe across participants design (n = 5). Two studies employed multiple-baseline across behaviors design, and two studies used the pre-test post-test design.

Measuring outcomes for parents and caregivers

Most of the trainings (n = 6) involved teaching all parents the same set of skills (e.g., teaching eye contact, delivery of reinforcement). Others (n = 3) included teaching parents specific skills needed for behavioral intervention based on a functional assessment and program development for their child (e.g., use of non-contingent attention and time-out) or specific skills for teaching novel behaviors to their child.

Six studies presented results for each parent participant as a percentage of occurrences of the correctly performed skills. One study displayed a mean percentage of correct responses for each trained participant, while another study showed the number of steps completed by each trained individual. One study used group averages to present the number of steps correctly completed by parents and the quality of implementation.

Most of the studies (n = 6) assessed the skills taught to parents in a clinical setting "in vivo" with their children or used video recordings of the parent-child interactions at home. On the other hand, three studies only measured the parental skill performance as observed by the experimenter during role-plays.

Measuring outcomes for children

Six studies (67%) provided information about the dependent variables associated with the outcomes for the children. These results included a wide variety of behaviors, which were either problem behaviors (e.g., spitting, grabbing, yelling, hitting, biting) and self-stimulatory behaviors (e.g., hand flapping, repetitive verbal noises, running in places), or appropriate behaviors (e.g., compliance with instructions, playing with toys, eating, dressing). Outcomes for children were measured by a percentage of correct responses (e.g., number of items of clothing folded correctly during the observation or number of instructions followed during a session) within a time-interval or a teaching session (n = 4). One study used a mean percentage of correct responses within each experimental phase, and one study reported changes in the frequency of stereotypy and problem behaviors within each session.

Generalization and maintenance

Generalization, across participants and settings, should be a common feature of any pyramidal parent training (see for details on generalization and maintenance measurement procedures). Two of the studies (22%) discussed the inherent generalization across participants features of the pyramidal training approach. However, only two studies (22%) included generalization probes, when parents applied their newly acquired skills in previously untrained situations (generalization across settings). Five of the reviewed studies did not include generalization probes or discuss generalization in any way.

Table 3. Study design and outcomes.

Six studies (67%) carried out maintenance probes at one day to two months after the termination of training sessions. One study used a questionnaire, which was administered to parents two years after the parent training and one study described maintenance as contact with parents one month after training, while no data were collected at the occasion. Finally, one study did not program for maintenance probes.

Measures of interobserver agreement and social validity

All of the studies reported an interobserver agreement (IOA). As there were several variables measured in each study, there were also several IOAs measured. The studies differed significantly in the complexity of IOA scoring and presentation. The number of IOAs reported in a study ranged from one IOA figure (e.g., mean average for all observed sessions and participants) to as many as 22 separate IOA results presented separately for each participant and each skill. In studies where the behavior of children was measured as the outcome of parent trainings, separate measures of IOA of parent performance and child behavior were provided (see for details). Across the studies, IOA ranged from 67% to 100% agreement for parent behaviors and between 82.3% and 99% agreement for children behaviors.

Social validity was explored in four out of the nine studies. Only studies using BST approach reported social validity. The measure was conducted post-intervention and used either a qualitative assessment of verbal comments (n = 1) or social validity questionnaire with a 5-point Likert scale (n = 3). The studies using questionnaires reported either mean average responses or total score from all questions. The study of Adubato et al. (Citation1981) used a follow-up questionnaire with open-ended questions. In one of the answers, parents judged it very important that they both learned the skills provided during training.

Pyramidal training and intervention results

Some studies measured only the skills parents acquired during training (n = 3; 34%). Others focused on training outcomes by assessing the parental performance with their child as well as results related to changes in the behaviors of the children (n = 6; 67%). One study included supplementary indirect measures of parental stress, self-efficacy, and child behavior pre and post-training. In studies where children were not involved, the primary dependent variable was the change in parent performance during role-plays following training. All studies measured the training outcomes for Tier 1 parents as well as Tier 2 and Tier 3 caregivers.

In total, 75 parents and caregivers participated in the parent training within the reviewed studies, and all made significant progress in the trained skill acquisition regardless of the level at which they were trained. Whether a professional or another parent trained them did not affect their performance. The only exception being the study of Bruder and Bricker (Citation1985), who registered slightly less dramatic acceleration in the skill acquisition in the Tier 3 parent group and ambiguous results for one parent in the Tier 2 group due to slightly elevated baseline data.

Results for children were less encouraging than those of their parents. There were 31 children who directly participated in the studies and had data included on their progress. After their parents or caregivers received training and were able to provide intervention, 22 children (67%) showed either the acquisition of new skills (e.g., mands/making requests for items, making eye contact, playing with toys) or a significant reduction in problem behavior.

Pyramidal parent training and cultural responsiveness

Although the review of the articles using the CRR rubric looked at the same components discussed above, it did so through a different lens. Each construct was critically evaluated to determine the degree to which that area was addressed with cultural competency. The full results of the CRR evaluation are provided in . For the overall construct of problem formation, the majority of the articles received a score of 2 for relevancy of the research problem (n = 5), a score of 1 for construct description (n = 6), and scores of 0 for theoretical framework (n = 5) and literature review (n = 5). For the overall construct of design and logic the area of participant description was the only area to receive scores of 2 (n = 3). A majority of the articles received scores of 1 for the areas of setting (n = 6) and sampling (n = 4). Almost all of the articles received a score of 0 for the researcher descriptions (n = 7). For the overall construct of sources of evidence, a score of 2 was only received in the area of intervention ecology, and only for one study; most articles received a score of 1 (n = 7). A majority of the articles received scores of 0 for the areas of data collection (n = 7) and intervention design (n = 7). For the overall construct of measurement process, which included only the area of intervention assessment, all of the articles received a score of 2 (n = 8). For the overall construct of analysis and interpretation the majority of the articles received a score of 1 for presentation of findings (n = 6); with almost all of the articles receiving a score of 0 for analysis and interpretation of the findings (n = 7). All of the articles received a score of 0 for the final construct of dissemination (n = 8).

Table 4. Culturally responsive rubric literature evaluation.

Discussion

The body of literature on pyramidal parent training is not extensive. After a comprehensive literature search, nine relevant studies were identified as being published within the last 40 years. A wide variety of skills were taught to parents and caregivers, ranging from a single procedure (e.g., differential reinforcement of alternative behavior) to complex skills (e.g., mand training or teaching motor imitation). Some parent trainings also involved knowledge components (e.g., learning the basic principles of behavior). The caregivers’ knowledge acquisition was measured by multiple-choice tests. Parents and caregivers at all levels of training and two-thirds of the children made significant progress in the measured target behaviors. After analyzing the literature on this model of training and intervention, several important topics for discussion and consideration by future researchers and practitioners surfaced.

Outcomes for children

The ultimate goal of parent skills training is the change of socially significant behaviors of their children with disabilities. This phenomenon has been demonstrated in much of the parent training literature. For example, a meta-analysis on parent training, conducted by Serketich and Dumas (Citation1996), found that training caregivers resulted in changes in their children’s antisocial behaviors across the home and school settings. In another example, the relationship between training parents and increasing their children’s academic successes in school was seen in the work of Araque and colleagues (Citation2017). Unfortunately, in the pyramidal parent training literature direct measurement of outcomes for the children of trained parents was not consistently included, and therefore does not provide enough evidence on the effectiveness of the trainings. Even the few studies that did present outcome measures for the children struggled to demonstrate change when the interventions were delivered by their parents.

Another problem found in the pyramidal training research was when parents were taught to use skills that were not specific to the needs of their children (i.e., the interventions were not systematically matched to the child’s function of behavior). The generic interventions did not align with the needs of the children and did not translate to successful behavior change. Kuhn et al. (Citation2003) did implement individually tailored behavior programs for each child in her study. A treatment plan for noncompliance of one of the children included a choice of preferred activities, positive reinforcement, physical guidance in case of noncompliance and break from tasks, and access to preferred items following compliance. Despite the high fidelity of intervention implementation by all caregivers during probes when the experimenter was present, no improvement in child’s compliance was observed with any of the caregivers. A failure of the procedure to have any effect on the target behavior despite high fidelity of intervention implementation should be considered when planning future studies. Seemingly, training in individualized programming is not enough to promote generative behavior change. In addition, steps need to be taken to ensure that parents continue to implement trained skills to the same degree even in the absence of the trainer.

Training fidelity

Professionals or students of behavioral sciences delivered trainings to the first Tier of parents. Description of the training content at this level was provided with detail in all of the nine studies. On the other hand, the information about the second and third level of trainings was presented with varying degrees of detail. In some cases, the authors only indicated that the parents used the same training approach as the master trainer (Loughrey et al., Citation2014; Hansen et al., Citation2017; Knecht, Citation2018; Conklin & Wallace, Citation2019). In other instances, it was up to the parent to decide on the training methods and timeframe (Adubato et al., Citation1981; Symon, Citation2005) when training the next level of parents or caregivers. Only in two studies (Neef, Citation1995; Kuhn et al., Citation2003) were specific trainings provided to the parents on how to become parent trainers.

As proposed by Smith et al. (Citation2007), the fidelity of intervention shall be checked and monitored by directly observing the implementation of the procedure. Within pyramidal parent training, interventions are often complicated, provided at several locations, and involving multiple participants. They usually require the training of the first tier of parents by professionals, parents training other parents, and intervention delivery to the children. Fidelity of implementation should be considered at all levels of training and intervention delivery. However, only four studies (44%) had the researchers checked for the fidelity of training implementation by the master trainer and six studies (67%) assessed fidelity of parent-delivered trainings. As pointed out by Andzik and Cannella-Malone (Citation2017), all training and implementation of newly acquired skills must be documented and measured for accuracy to ensure that each level of implementation of the pyramidal training model directly causes changes in the target behaviors on the next level. It is impossible to make conclusions about experimental control when we do not know whether the intervention was provided as intended and what caused the change in the target behavior.

Maintenance and generalization

Five studies (56%) measured maintenance for parents’ skills, and only four studies (44%) included a follow-up measure for outcomes of the children. The results of maintenance probes varied widely across studies. As defined by Alberto and Troutman (Citation2003), maintenance means that a response is performed over time, even after a systematic intervention has been withdrawn. The study of Kuhn et al. (Citation2003) measured maintenance on the last day of training, which does not fulfill the proposed definition. Other studies provided only one maintenance probe at a single occasion or as was the case in Adubato et al. (Citation1981), used indirect measurement (e.g., a questionnaire sent to parents to be filled out). As stated by Kuhn et al. (Citation2003), follow up data were not collected due to caregiver time constraints and because long-term follow up was beyond the scope of the study.

Generalization of behavior change happens when the target behavior occurs outside of the learning environment (Baer et al., Citation1968). For example, Loughrey et al. (Citation2014) described generalization in their research as a transfer of parent skill performance from working with a graduate student during the training session to working with their child at home. This notion is in line with Koegel et al. (Citation2002), who demonstrated that parents could learn intervention procedures in a clinical setting and generalize their use into their homes. Several of the reviewed studies trained parents in clinical settings using role-play (see ). Generalization was certainly involved when they later applied these skills at home with their children. However, only two studies investigated the phenomena in more detail. Adubato et al. (Citation1981) trained parents in the use of appropriate instructions and guidance to teach their child how to put on clothing. The study demonstrated the generalization of the parents’ skills when they successfully used them for teaching eating and dressing behaviors to their child without further parent training. A similar effect was demonstrated by Bruder and Bricker (Citation1985), who taught parents skills to teach a new behavior to their children. Parents participated in a training session with their children and were instructed to choose and train two new behaviors. In the following sessions and follow up, parents were able to use the techniques across a variety of new behaviors.

However, presently there are not enough data in the pyramidal parent training literature to determine the generalizability of the approach and its ability to maintain behavior change across time and settings. Targeting and assessing generalization and maintenance of intervention effects would add to the quality ratings of the pyramidal parent training studies.

Training in other countries and cultures

Three of the reviewed studies (33%) either took place outside of the United States or described the inclusion of participants who were outside of the dominant culture. Some of the participants needed a translator for the training. One of the two Chinese parents, who needed translation and was trained by a professional at Level 1 training, showed slightly below-average levels of correct responding after being trained (range 80–100%) as compared to other participants, who all scored at 100%. She also performed slightly below average when training another caregiver (90% fidelity as compared to 100% fidelity of other parent trainers). Also, both of the non-English speaking participants chose less favorable options on the 5-point Likert scale used for measuring social validity and effectiveness of the training. Conklin and Wallace (Citation2019) stated the possibility that some of the training methods and procedures could have been difficult to understand when interpreted from English to Mandarin. Despite the problems encountered with translation, all participants of the study made significant progress with their correct responding, ranging from 10% to 50% at baseline and 80% to 100% post-training.

Another two studies (Hansen et al., Citation2017; Knecht, Citation2018) were conducted in economically developing countries of Southeast Europe, namely Macedonia and Albania. Next to the difficult economic situation of Macedonia, Ajdinski and Florian (Citation1997) also reported under-resourced and under-equipped services for children with disabilities, including treatment staff not being up to date on the latest treatment options. Albania faces an even more difficult situation, being the poorest country in Europe, with around 35% of the population living below the poverty line (World Bank, Citation2019). As stated by Knecht (2018), Albanians who have children with disabilities may face additional stress as they work to provide enough resources for their families and children. In that study (Knecht, Citation2018), students of behavior science who spoke Albanian served as the master trainers. A breakdown in the training system happened when one of the parents was trained with below 90% fidelity, which subsequently caused lower skill acquisition in the following levels of training. Despite this issue, all participants made significant gains in skill acquisition. The results indicate that in a setting of a developing country, after being trained by a professional, a caregiver could train another caregiver to redirect repetitive behaviors appropriately, use praise, and request eye contact (Knecht, Citation2018).

The studies mentioned above show promising results of pyramidal parent training use in other than Anglo-American cultures and across countries with different social structures and economic realities. The results indicate that pyramidal parent training can be a cost-efficient way of training and intervention delivery worldwide. This finding may be especially crucial for families with children with neurodevelopmental disorders living in geographical areas and countries where professionals providing treatment based on applied behavior analysis are hard to reach. However, breakdowns that were observed in these studies may align with challenges in cultural responsiveness and should be carefully considered in future work.

Cultural responsiveness

A more critical look at the culturally responsive research practices of eight of the nine studies in this review revealed struggles in many of the component areas. In fact, some of the challenges discussed above align with holes in these practices. The research and training approaches fell short in giving consideration to the unique culturally and linguistically diverse experiences of participants. As a result, struggles with applied outcomes, fidelity, and generalization occurred. However, a few strong areas in culturally responsive practices did surface.

Developing an intervention focused on the family’s context and culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) characteristics would likely increase desired outcomes and generalization. While intervention targets appeared socially valid, and were selected with some input from the families, consideration of community-values, cultural norms, or the unique knowledge base brought to the table by the parents was not highlighted. Only the Symon’s (Citation2005) study scored 2 in one of these rubric areas. Increased outcomes for children (e.g., functional verbal utterances with appropriate body movements and decibel level) might have also been supported by conducting the training in the most relevant setting, as opposed to a contrived clinical environment. However, none of the studies provided sufficient descriptions of the training settings to allow for a clear understanding of the treatment environment in relation to the community or family. Incorporating an alignment between the data collection procedures, rationale, and the needs of the families may have also improved intervention success. One example of this incorporation might be interviewing parents about the behaviors of interest, selecting a plan for intervention with the parents, and developing data collection tools that the parents can easily access on their phones. Again, none of the studies scored a 2 in this area with Neef (Citation1995) scoring the only 1. Additionally, the cultural background of the participants did not appear to be pertinent to the development of the research, as collection of in-depth participant information was seemingly overlooked in a majority of the studies. Lastly, in order to create change that persists after training and leaves a valuable impact on the family and community, steps need to be taken to make the research and results accessible to the public. Unfortunately, none of the studies provided plans to make the intervention or results accessible to other parents or locals; or use the results to drive policy change for the marginalized groups involved. However, all of these evaluations are made based on the information provided in the journal articles. It could be the case that the researchers did use culturally-valid approaches throughout their work, but were unable to include this information in the articles.

The review using the rubric did reveal some positive characteristics, though. Although experimental design was not assessed with the rubric, it was part of the general research review. All of the studies used single-subject designs, which may support the premise of culturally responsive research. The use of single-subject designs resulted in the disaggregation of participant data in the majority of the studies. In addition, such designs commonly support the evaluation of intervention research. Intervention research, especially in the field of behavioral services, is typically driven by participants’ needs. Although more steps would be needed for complete individualization at the level of CLD characteristics, basic intervention individualization did result in good assessment practices. All of the studies used at least some skill-based or performance-based assessments which were created specifically for the study, targeted the individualized training plan, and translated into a local language when needed. Furthermore, a main tenet of research in the field of behavior analysis is the use of socially significant interventions. This emphasis on social significance supports the relevancy of the research problem construct, aligning with the need to use an intervention that is targeting a skill which is important to the participants, and not just the researchers (Bal & Trainor, Citation2016). Most of the studies did present the research problem in the context of family and community needs.

Strengths, limitations, and future research

This review presents information for researchers and practitioners working to meet the training needs of families in regions where access to services remains limited. Having a breakdown of the variants of pyramidal parent training can serve as a foundation for those looking to develop the field. However, the findings of the review should be used with care. Pyramidal parent training involves multiple opportunities for measuring training outcomes: The fidelity of training delivery, fidelity of the intervention, variations of child’s target behavior with each trained individual, assessment of generalization of the trainees’ and children’s behaviors, social validity measures, and multiple evaluations of IOA. In addition, the trainings usually involve complex behaviors of trainers as well as trainees and work with multiple participants, including professional trainers, parents, other caregivers, and children. Some participants even acquire more than one role during pyramidal training. It was outside of the scope of this literature review to analyze all the complexities of the selected studies.

Therefore, our study included a synthesis of the skills taught to parents, training forms and techniques, research design, essential components of sound experiments in behavior analysis (e.g., measures of procedural fidelity, IOA , generalization or maintenance), and basic success estimates based on the reported results. As a result, a full analysis of the studies did not occur and the review did not take steps to analyze the data in a quantitative manner. Future research might look at using meta-analysis procedures to create a more refined picture of success. Analysis of the results for each tier of participants could separately and subsequently compare the tiers or create a ratio of successful implementation of the independent variable to the total implementation attempts (Reichow & Volkmar, Citation2010). Calculating the magnitude of treatment effect using power analysis could also be an option for future work (Kyonka, Citation2019). In addition, the evaluation of the cultural responsiveness of the research was completed by only two researchers and used a tool that may have limited validity. More work should be done by future researchers to validate the CRR rubric and evaluate specific features of pyramidal parent training.

Conclusion

Overall, the results of this review are promising. While the studies indicated that parents could teach other parents or caregivers to implement a variety of behavioral techniques using pyramidal parent training, there is not yet enough research to fully support this approach. Teaching parents to utilize basic principles of behavior in their everyday interaction with their children could have life-changing effects on the quality of life of families with children with ASD and other developmental disabilities. However, future research on pyramidal parent training should look more closely at changes in children’s behavior. The results also show that pyramidal parent training has the potential to be used with participants from a variety of cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Again, future work should ensure that steps are taken to practice cultural responsiveness. Simply applying these practices across diverse populations does not result in the most meaningful outcomes if the unique needs of different groups are not only considered, but also systematically incorporated into planning, practice, evaluation, and dissemination.

References

- Adubato, S. A., Adams, M. K., & Budd, K. S. (1981). Teaching a parent to train a spouse in child management techniques. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 14(2), 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1981.14-193

- Ajdinski, L., & Florian, L. (1997). Special education in Macedonia. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 12(2), 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/0885625970120203

- Alberto, P. A., & Troutman, A. C. (2003). Applied behavior analysis for teachers (6th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- American Psychological Association. (2003). Guidelines on multi-cultural education, training, research, practice, and organizational change for psychologists. American Psychologist, 58, 377–402.

- American Psychological Association. (2010). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.aspx

- Andzik, N., & Cannella-Malone, H. I. (2017). A review of the pyramidal training approach for practitioners working with individuals with disabilities. Behavior Modification, 41(4), 558–580. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445517692952

- Araque, J. C., Wietstock, C., Cova, H. M., & Zepeda, S. (2017). Impact of Latino parent engagement on student academic achievement: A pilot study. School Community Journal, 27(2), 229–250.

- Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., & Risley, T. R. (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1(1), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91

- Bal, A., & Trainor, A. A. (2016). Culturally responsive experimental intervention studies: The development of a rubric for paradigm expansion. Review of Educational Research, 86(2), 319–359. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315585004

- Baumann, A. A., Powell, B. J., Kohl, P. L., Tabak, R. G., Penalba, V., Proctor, E. K., Domenech-Rodriguez, M. M., & Cabassa, L. J. (2015). Cultural adaptation and implementation of evidence-based parent-training: A systematic review and critique of guiding evidence. Children and Youth Services Review, 53, 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.03.025

- Bruder, M. B., & Bricker, D. (1985). Parents as teachers of their children and other parents. Journal of Early Intervention, 9(2), 136–150.

- Burnard, P. (2013). Acquiring interpersonal skills: A handbook of experimental learning for health professionals. Springer Science + Business Media.

- Castro, F. G., Barrera, M., & Martinez, C. R. (2004). The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: Resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prevention Science : The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 5(1), 41–45. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:prev.0000013980.12412.cd

- Conklin, S. M., & Wallace, M. D. (2019). Training caregivers in the use of a differential reinforcement procedure. Behavioral Interventions, 34(3), 377–387.

- Gay, G. (2002). Preparing for culturally responsive teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(2), 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487102053002003

- Gersten, R., Fuchs, L. S., Compton, D., Coyne, M., Greenwood, C., & Innocenti, M. S. (2005). Quality indicators for group experimental and quasi-experimental research in special education. Exceptional Children, 71(2), 149–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290507100202

- Hansen, B. D., Orton, E. L., Adams, C., Knecht, L., Rindlisbaker, S., Jurtoski, F., & Trajkovski, V. (2017). A pilot study of a behavioral parent training in the Republic of Macedonia. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(6), 1878–1889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3112-6

- Johnson, C. R., Butter, E. M., & Scahill, L. (2018). Parent training for autism spectrum disorder: Improving the quality of life for children and their families. American Psychological Association.

- Keen, D., Couzens, D., Muspratt, S., & Rodger, S. (2010). The effects of a parent-focused intervention for children with a recent diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder on parenting stress and competence. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(2), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2009.09.009

- Knecht, L. L. (2018). Pyramidal parent training for children with autism spectrum disorder in Southeast Europe [Provo: Brigham Young University. All Theses and Dissertations]. 6987. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6987

- Koegel, R. L., Symon, J. B., & Koegel, L. K. (2002). Parent education for families of children with autism living in geographically distant areas. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 4(2), 88–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/109830070200400204

- Kuhn, S. A. C., Lerman, D. C., & Vorndran, C. M. (2003). Pyramidal training for families of children with problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36(1), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2003.36-77

- Kyonka, E. G. E. (2019). Tutorial: Small-n power analysis. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 42(1), 133–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-018-0167-4

- Lau, A. S. (2006). Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence‐based treatments: examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(4), 295–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00042.x

- Leaf, J. B., Townley-Cochran, D., Taubman, M., Cihon, J. H., Oppenheim-Leaf, M. L., Kassardjian, A., Leaf, R., McEachin, J., & Pentz, T. G. (2015). The teaching interaction procedure and behavioral skills training for individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder: A review and commentary. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2(4), 402–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-015-0060-y

- Loughrey, T. O., Contreras, B. P., Majdalany, L. M., Rudy, N., Sinn, S., Teague, P., Marshall, G., McGreevy, P., & Harvey, A. C. (2014). Caregivers as interventionists and trainers: Teaching mands to children with developmental disabilities. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 30(2), 128–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-014-0005-z

- Neef, N. A. (1995). Pyramidal parent training by peers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 28(3), 333–337. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1995.28-333

- Page, T. J., Iwata, B. A., & Reid, D. H. (1982). Pyramidal training: A large-scale application with institutional staff. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 15(3), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1982.15-335

- Parsons, M. B., Rollyson, J. H., & Reid, D. H. (2012). Evidence-based staff training: A guide for practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 5(2), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03391819

- Reichow, B., & Volkmar, F. (2010). Social skills interventions for individuals with autism: Evaluation for evidence-based practices within a best evidence synthesis framework. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(2), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0842-0

- Reid, D. H., & Fitch, W. H. (2011). Training staff and parents: Evidence-based approaches. In International handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders (pp. 509–519). Springer.

- Serketich, W. J., & Dumas, J. E. (1996). The effectiveness of behavioral parent training to modify antisocial behavior in children: A meta-analysis. Behavior Therapy, 27(2), 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(96)80013-X

- Smith, T., Scahill, L., Dawson, G., Guthrie, D., Lord, C., Odom, S., Rogers, S., & Wagner, A. (2007). Designing research studies on psychosocial interventions in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(2), 354–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0173-3

- Symon, J. B. (2005). Expanding interventions for children with autism: Parents as trainers. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 7(3), 159–173.

- Trainor, A. A., & Bal, A. (2014). Development and preliminary analysis of a rubric for culturally responsive research. The Journal of Special Education, 47(4), 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466912436397

- Vincent, C. G., Randall, C., Cartledge, G., Tobin, T. J., & Swain-Bradway, J. (2011). Toward a conceptual integration of cultural responsiveness and schoolwide positive behavior support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 13(4), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300711399765

- Whalen, C. K., & Henker, B. A. (1971). Pyramid therapy in a hospital for the retarded: methods, program evaluation, and long-term effects. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 75(4), 414–434.

- World Bank (2019). Poverty & Equity Brief – Europe & Central Asia – Albania. World Bank. Available at: https://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/poverty/33EF03BB-9722-4AE2-ABC7-AA2972D68AFE/Global_POVEQ_ALB.pdf