Abstract

Prolonged tube feeding has a multitude of negative outcomes. The transition to oral feeding is essential for child and family quality of life. Behaviour-analytic interventions are effective for paediatric feeding disorders, but information is lacking regarding the treatment process and outcomes. This study evaluated a home-based behavioural intervention for a 19-month-old child dependent on tube feeding. An intensive period was followed by caregiver support to advance feeding skills. We applied differential reinforcement and volume fading within a multiple probe design. Results showed clinically significant behavioural and nutritional outcomes, the cessation of tube feeding, and a process valued by the family.

Paediatric feeding disorders may be diagnosed early in life, particularly for children born premature. Owing to decreased suckling strength and oral motor delays, tube feeding may be initiated and continued upon discharge home (Alshaikh et al., Citation2022). Inarguably, tube feeding is essential for survival, nutrition, and growth (Lagatta et al., Citation2021). Caregivers may report further benefits of tube feeding, such as reduced stress in managing their child’s nutrition, and ease of medication administration (Martinez-Costa et al., Citation2013).

Despite the shorter-term benefits, tube feeding has negative outcomes, particularly when prolonged. Tube feeding is associated with risk of infection, and continued aversive experiences to the oral-facial area (Mason et al., Citation2005). Tube feeding may disrupt the natural tendency for mothers to nurture their babies and is associated with a high level of caregiver stress, anxiety, or depression, owing to the burden of tube feeding care (Greer et al., Citation2008; Pedersen et al., Citation2004; Stevenson, Citation2018; Wilken, Citation2012). Moreover, for many communities, food is cultural, not solely nutritional. Thus, children with tube dependency may be excluded from being fully immersed in the cultural rituals and practices that are predominantly based around the eating and sharing of food (Reddy & Anitha, Citation2015).

Behavioural interventions for paediatric feeding disorders are an empirically supported intervention, based on over 50 years of research (Taylor, Virues-Ortega, et al., Citation2021; Williams & Seiverling, Citation2022). Reviews focusing specifically on tube dependency assert that treatment typically takes place in highly controlled settings, with high intensity and multidisciplinary involvement (Sharp et al., Citation2017; Taylor, Virues-Ortega, et al., Citation2021; Williams & Seiverling, Citation2022). For children with tube dependency, highly controlled hospital settings allow for ease of multidisciplinary team consultation, the management of complex medical conditions, and to monitor for complications (e.g., allergies or blood sugar concerns; (Marinschek et al., Citation2014; Sharp et al., Citation2017). Further, a controlled setting may mitigate extraneous variables such as disruptions within the family home environment.

There are few behavioural studies that outline treatment provided in outpatient or home settings, or with extended caregiver implementation. Some demonstrations have occurred after completion of prior intensive treatment, and focused on specific skills such as self-feeding (Rivas et al., Citation2014; Volkert et al., Citation2016), self-drinking (Peterson et al., Citation2015, Citation2017) or chewing (Volkert et al., Citation2014). Peterson et al. (Citation2015) used telehealth to train caregivers to implement a differential reinforcement intervention to teach self-drinking for two children who had achieved initial liquid acceptance during intensive treatment. Volkert et al. (Citation2014) evaluated procedures to teach chewing for one child via telehealth, with caregivers implementing treatment in a local hospital room.

Access to controlled treatment settings is a barrier for children with paediatric feeding disorders, particularly for those in international countries (Sharp et al., Citation2017; Taylor, Virues-Ortega, et al., Citation2021; Taylor & Taylor, Citation2021a). Recent and emerging research highlights positive treatment outcomes for children who receive the entire behaviour-analytic treatment in a home-based setting (Patel et al., Citation2022; Taylor, Citation2020; Taylor, Purdy, et al., Citation2019; Taylor et al., Citation2021). These studies have reported outcomes for children with tube dependency or severe paediatric feeding disorders, with treatment involving multidisciplinary evaluation and consultation, and a high degree of caregiver involvement. Recently, Patel et al. (Citation2022) presented outcomes for 78 children with tube dependency after home-based behaviour analytic intervention, whereby tube elimination was achieved in 8 months on average. Outside of the behavioural literature, effectiveness is also reported for hunger provocation approaches in homes for children with tube dependency (Marinschek et al., Citation2014; Wilken et al., Citation2013) In light of these findings, there is a need to evaluate further demonstrations of home-based interventions.

Outlined by recent reviews, a further need for paediatric feeding research is the reporting of treatment processes and outcomes (Taylor & Taylor, Citation2023; Williams & Seiverling, Citation2022). Treatment processes may include describing the overall progression of the intervention; specifically the targeting of variety, textures, and skills that enable the child to reach age-appropriate eating and drinking. Prior studies have tended to focus on a specific skill area (e.g., cup drinking) or analysis of specific procedures (e.g., reinforcement) without reporting the course of treatment or the overall outcome. However, some recent studies are making steps to increase reporting of the overall process, including the outcomes of home-based treatment. Taylor et al. (Citation2021) reported individualised goals for 26 participants with varied feeding difficulties who received home-based behaviour-analytic intervention. Example progressive goals for liquids included self-drinking from an open cup, full cup sipping, with generalization to water bottles. Example goals for eating included food acceptance and consumption, chewing, self-feeding with utensils, and self-scooping. For a 5-year old girl with tube dependency, Hansen and Andersen (Citation2020) also documented the entire treatment process, from the initial intensive programme to outpatient follow-up (including home and school settings). Treatment was described for initial goals of puree and formula consumption, followed by teaching chewing, self-feeding, then independently consuming age-appropriate portions of table-texture foods.

In terms of treatment outcomes, it is vital to convey that behaviour-analytic interventions can improve multiple domains of eating that result in changes to nutrition and quality of life. To this end, outcome reporting should extend beyond measures of mealtime behaviour, but multiple outcomes are infrequently reported in the literature (Taylor & Taylor, Citation2023; Taylor, Virues-Ortega, et al., Citation2021; Williams & Seiverling, Citation2022). Some examples include Taylor et al. (Citation2021) who reported improvements in mealtime behaviour and food variety, supported by photographs of food portions consumed. Wilkins et al. (Citation2014) provided data on behaviours and intake during caregiver-implemented meals up to 12 months follow-up (Wilkins et al., Citation2014). For children with tube dependency, Taylor, Purdy, et al. (Citation2019) and Hansen and Andersen (Citation2020) reported changes to behaviour, nutrition (weight, intake) during intervention and over long-term follow-up.

Overall, the evaluation of behaviour-analytic treatments for paediatric feeding disorders may be improved by broader reporting of goals, processes and outcomes. The aim of the current study was to evaluate processes of a home-based behaviour analytic intervention across feeding goal domains for a child dependent on nasogastric tube feeding. Primary outcomes included multiple measures of mealtime behaviour and nutrition during waitlist, intervention, and long-term follow-up. Mealtime behaviours were evaluated across key skill areas aligned with family goals, within a single-case design (multiple probe). Secondary outcomes included social validity and caregiver stress.

Method

Participant

The current participant, Maia, met inclusion criteria established for the trial, including: (a) being between 1 and 16 years old; (b) receiving 20% or more of nutrition enterally for 6 months or more; (c) stability or resolution of any contributing medical conditions (e.g., reflux adequately controlled); (d) not having any pending medical interventions that could interfere with treatment; (e) not having any anatomic or functional impairment precluding safe oral feeding; (f) being able to swallow liquids safely, as confirmed by a previous videofluroscopic swallow study; and (g) having a clinically safe weight with appropriate growth while being tube fed. Each child required eligibility to be confirmed by their multidisciplinary team (pediatrician, speech-language therapist, dietitian) according to these criteria. The researchers gained written informed consent from parents and assent from participants when possible to do so.

Maia was a 13-month-old girl of Chinese ethnicity. She was born prematurely at 33 weeks gestation (Birthweight 1270 g, <0.4th percentile) where she spent approximately two months in hospital. Maia received nasogastric tube feeding from birth and had diagnoses of faltering growth (weight remaining <0.4th percentile), and gastroesophageal reflux. Upon being discharged from the hospital, Maia continued tube feeding for all her nutritional requirements. It is important to note that international standards recommend nasogastric tube feeding to be temporary (a few months) prior to gastrostomy tube placement. However, surgery waitlists and healthcare system issues in New Zealand often result in nasogastric tubes being used for extensive periods (Jones et al., Citation2020).

At the time of referral, Maia assigned to the waitlist period for six months (13 to 19 months of age), before starting the intervention. She initially received 100% of her nutrition via tube feeding. She consumed adequate amounts of water from an open cup or straw bottle, but refused to drink any other liquids with these receptacles. Maia consumed some fruit purees (apple, banana) fed by a caregiver. Puree volume consumed was inconsistent, but Maia had been able to fully consume a pouch (120 g) on some occasions, based on waitlist records. Maia also self-fed specific packaged brands of cheese sticks, rice crackers, and yoghurt drops. Maia was seated in a highchair in front of the television for all meals, which played continuously. During the waitlist period, Maia’s food consumption declined and her parents reported increased crying, gagging and refusal (pushing spoon, head turning). By the time of admission, Maia was reported to refuse most attempts at feeding (purees) but continued to self-feed small amounts of aforementioned packaged foods. In addition, two weeks prior to intervention Maia had started to accept formula from a spoon, resulting in tube feeding reducing to 68% of nutritional requirements. In terms of prior services, Maia had accessed publicly-funded speech therapy, involving several home visits where general advice was provided to the family. As reported by her paediatrician, Maia had met other milestones expected at her age, including communication, gross motor, and fine motor skills. She could follow simple instructions and use single words to make requests or label items in Mandarin and English.

Setting and materials

Meal sessions were conducted in a home setting in the family dining room. The researcher/s, Maia’s caregivers, and occasionally grandparents were present in the room during sessions. The family dining room consisted of a dining room table and chairs, television, an electronic device for data collection, and electronic kitchen scales. Meal-related items included bowls, maroon spoons, a DoidyTM cup, and a sectioned plate (self-feeding). Maia was seated in an age-appropriate highchair with a tray attached that was approved by her speech-language therapist as providing a correct seating positioning for feeding. A Zoom video conferencing platform was used during follow-up visits and when Covid-19 restrictions prohibited in-person visits. Maia’s parents also provided mealtime videos for some pureed food sessions that occurred outside of researcher visits.

Design

The current study took place within a larger ongoing trial (Ready to Eat), and reports findings for an individual participant. Ethics approval was obtained from a national ethics committee with trial information listed in a clinical trial database (UTN identification number U1111-1226-0354). The Ready to Eat trial involves randomization of each participant to waitlist or intervention. In addition, single-case designs are adopted to demonstrate experimental control of individualised intervention procedures and to facilitate clinical decision-making essential to paediatric feeding disorders (Kempen, Citation2011). In single-subject experiments each participant serves as their own control, and data are visually examined.

The current study adopted a multiple probe across behaviours (skills) design. A multiple probe design involves first applying intervention procedures to one context (or, skill) while subsequent skills continue to be monitored (or, remain under baseline conditions). In this study, the intervention was applied to the first family-selected goal (purees), followed by goals of self-feeding and self-drinking. Criteria informing the advancement of the intervention within and across skills was at least 80% consistent consumption, and inappropriate mealtime behaviour below 20%, across three consecutive sessions.

Primary outcome: behavioural measures

Observers scored behaviours either in real time or from video recordings using Countee installed on an iPad or iPhone device. For puree foods and drinks sessions, target behaviours were initially scored on a trial-by-trial basis and summarised as a percentage of trials. Acceptance was scored when Maia accepted the entire bolus from the spoon or cup. During initial empty spoon/cup sessions, acceptance was scored when Maia opened her mouth to allow full lip closure on the spoon or rim of the cup. Mouth clean was scored if there was no food larger than the size of a pea in Maia’s mouth, 30 s after acceptance, unless absence was due to expulsion. Inappropriate mealtime behaviour (IMB) was scored if Maia turned her head >45° from the spoon or cup, pushed the feeder’s arm, utensils, or plate, or engaged in vocal protest (“no,” crying). Self-feeding meals were conducted in a free operant (portion-based) format where Maia was able to choose bites of food from the plate. For these meals the frequency of self-fed acceptance was scored when Maia placed the entire bite of food into her mouth. Mouth clean was scored via checks approximately 30 s after acceptance, or prior to Maia attempting to take another bite, whichever occurred earlier. Acceptance and mouth clean data for self-feeding meals were summarised as the percentage of bites consumed out of the total number of bites (out of 25 bites), during a 20-minute meal session, and IMB was summarised as responses per minute.

Inter-observer Agreement (IOA)

Secondary observers recorded the occurrence of acceptance, mouth clean and IMB. Inter-observer agreement (IOA) was collected in person or via video recording across study phases during 41% of puree sessions, 36% of self-feeding sessions, and 24% of self-drinking sessions. For trial-by-trial data (purees, drinking), IOA was calculated by dividing the total number of overall agreements by the total number of agreements plus disagreements, multiplied by 100. An agreement was defined as a trial in which both observers scored the occurrence or non-occurrence of the behaviour. Disagreement was defined as a trial in which one observer scored occurrence, and the other scored a non-occurrence of the behaviour or vice versa. For self-feeding data, IOA was calculated by dividing the smaller total count by the larger total count within five-min intervals, multiplied by 100. Across skill areas, mean IOA for acceptance was 96% (range, 80% to 100%), mouth clean was 97% (range, 80% to 100%), and IMB was 96% (range, 70% to 100%).

Primary outcome: nutritional measures

Oral intake was calculated by using an electronic kitchen scale, subtracting the pre-meal weight from the post-meal weight to obtain the number of grams consumed per meal. Tube intake was reported by caregivers as the daily amount (mL) provided via the tube, corresponding with dietitian recommendations. Body weight was measured at regular intervals, by the researchers or the dietitian using a calibrated Tanita Digital Scale.

Feeders

During waitlist and part of the baseline sessions, Maia’s mother acted as the feeder. Maia’s mother and father were of Chinese ethnicity and worked primarily from home due to the Covid-19 restrictions at the time. The feeder during baseline (portion of) and intervention sessions in the intensive phase was a psychologist and doctoral-level Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA). Following training, Maia’s mother then conducted most mealtime sessions for the first month of caregiver implementation (later described), followed by Maia’s father sharing this role (feeding approximately 40% of meals). During caregiver implementation, a postgraduate student studying towards a master’s degree in Applied Behaviour Analysis conducted further caregiver training for self-feeding and self-drinking goals under supervision of the BCBA and monitored implementation. During the caregiver implementation phase, the BCBA reviewed mealtime data weekly, provided in vivo supervision weekly (fading to bi-weekly), reviewed caregiver mealtime videos, and consulted with the multidisciplinary team.

Multidisciplinary team

Maia’s multidisciplinary team were in place prior to the study (public-funded) and conducted initial evaluation for the purposes of determining eligibility. Further, the team provided ongoing consultation throughout the study. Roles were as follows: a speech-language therapist (SLT) assessed feeding safety and gave recommendations relating to feeding posture, bite size, food textures, utensils, and cups to facilitate self-drinking. During intervention, the speech therapist visited once, and observed mealtime videos to provide feedback on two occasions. The dietitian recommended food types, portion size, and determined tube feeding reductions following review of oral intake and body weight. During intervention, the dietitian visited on a weekly basis initially to obtain weight, reducing to bi-weekly, then monthly visits. The paediatrician evaluated Maia’s medical suitability and conducted one further review during the intervention period, according to usual paediatrician schedules.

Procedure

The overall phases of the study included a waitlist period of 6 months, followed by an intervention period of 6 months. The intervention phase initially involved an intensive period, consisting of multiple meal sessions per day, followed by weekly to bi-weekly visits to support caregiver implementation.

Waitlist

During the 6-month waitlist, data were collected at two-monthly intervals. At the first visit, a semi-structured clinical interview was completed which obtained information regarding Maia’s medical and feeding history, family food preferences, mealtime behaviours, and currently accepted foods. During waitlist visits, the researchers did not provide any recommendations, and referred the family back to their health professionals where required. Waitlist visits involved a meal observation conducted by Maia’s mother for a maximum duration of 10 minutes (purees, formula), or 20 minutes (self-feeding). Maia’s mother was instructed to present foods or drinks as she “normally would.” with the addition of a mouth clean check 30 s after acceptance (if this occurred). Purees were selected by the family from a list of eight Stage 2 puree blends. Foods were selected across food groups but were a blend common to store-bought purees (e.g., carrot & apple, banana & oats, lamb & vegetables). The television (YouTube children’s videos) was on during all observed meal attempts in waitlist. To avoid the potential reactivity of waitlist observations, the researchers sat at a distance at the table and minimised interactions with Maia or her mother, until after the observation was complete.

Intensive period

As per general study protocols, Maia was initially scheduled to participate in a 2-week intensive period, but timing of Covid-19 stay-at-home orders reduced this period to eight days. Week 1 consisted of two consecutive days, and Week 2 consisted of 6 consecutive days, after which stay-at-home orders resumed. Researchers were generally present in the home for 4–5 hours, with a break away from the home when Maia napped. Initial meal blocks were 45 min in duration consisting of two 15-min meals, with a 10–15 min break between. Meal blocks were conducted at 1.5–2 hours after Maia’s last tube feed. Owing to the reduced intensive period, the initial family-selected goal was to increased consumption of varied pureed foods. Baseline data for formula drinking and self-feeding were also collected in this period.

Baseline

Baseline observations were conducted during the intensive period in a similar manner to waitlist observations but were more formally structured to obtain trial-based (bite-by-bite) data. Maia’s parents listed her preferred television shows, and prior to the session, provided brief access to 3–4 shows (10–15 s per show) to allow Maia to choose a show. The television was then on continuously throughout the meal, as this represented a “true baseline.” Foods were the same as during waitlist. During each session, 3–4 food types were used and rotated on each trial. During five-trial sessions, the feeder presented the bite (level spoon volume) to Maia’s lips with a verbal instruction to “Take a bite” approximately every 30 seconds. If Maia accepted the bite, praise was provided (e.g., “well done”). During a 15-minute meal, three five-trial sessions were typically conducted (i.e., 15 bite presentations). The meal session terminated at the time cap (15-minutes, not upon refusal), but would have been terminated earlier if safety concerns were noted (e.g., vomiting, allergic reaction). Approximately 30 s post-acceptance, the feeder prompted a mouth clean check (“show me aah”) and delivered praise for clean mouth. If Maia had not swallowed the bite at the mouth clean check (packing), the feeder provided instruction to “swallow,” then conducted a further mouth clean check (and instruction if required) every 30 s. A new bite was not presented until Maia had swallowed the previous bite. If Maia was still packing at the 15 min time cap, the feeder would have scooped out the food, but this never occurred, nor any packing. If Maia expelled a bite (did not occur), it was not re-presented. If Maia did not accept a bite within 5 s and/or engaged in IMB, the spoon was removed for approximately 30 s before the next bite was presented. To evaluate whether continuous access to television influenced behaviour (i.e., served as a “distractor” from eating), we also conducted further sessions with the same procedure as above, but with the television off, until data were stable.

Baselines for self-feeding and self-drinking were conducted by Maia’s mother. Targeted foods for self-feeding were initially from a list of 12 family-selected foods across food groups. Based on speech therapist observation and recommendation, food texture was initially mashable (e.g., avocado, cooked carrot, cooked apple, steamed fish) with the bite able to be squished flat between finger and thumb, or dissolvable (e.g., cracker, potato stick). Bite sizes were initially 1 × 1 cm. At caregiver request, five bites of a preferred food were initially included in self-feeding meals (cheese, potato stick). Overall, the plate included 25 bites, including 5 bites each of preferred food, fruit, vegetable, protein, and carbohydrate. A spoon and child’s fork were provided.

At the start of the session, the feeder placed the plate in front of Maia with instruction to “take a bite,” and this verbal instruction was repeated approximately every 30 s. No physical guidance or assistance was provided by the feeder unless Maia required assistance with the utensil (e.g., attempting to spear a food with the fork). Consequences for acceptance and IMB were similar to that described for purees, with the addition of blocking any attempt to play with food or tipping the plate over (neither behaviour occurred). The television was on continuously.

For self-drinking, the targeted drink was Maia’s prescribed Infatrini formula (later changed to Fortini upon dietitian guidance). During five-trial sessions, the feeder placed the cup on Maia’s tray approximately every 30 s with instruction “take a drink.” All other aspects of the procedure were the same as the pureed food baseline procedure, with the addition of blocking any attempt to push or tip the cup.

Differential Reinforcement of Alternative Behaviour (DRA) + volume fading

Intervention sessions for purees were initially conducted by the BCBA, then Maia’s mother upon stable progress (training started from Day 7). Maia’s mother was involved in food preparation and observed all meals, seated at the table. Maia’s father participated in meal preparation or meal observation during 50% of sessions owing to work commitments. Prior to meals, caregivers were instructed to (1) provide praise upon acceptance or mouth clean if they chose to, (2) to engage in general interactions with Maia, and (3) to not provide attention upon IMB. General interactions included physical touch or conversation that Maia’s parents typically engaged in with her, for example: answering a question, repeating a word Maia stated, or labelling television characters in Mandarin.

The initial volume starting point for purees was established via initial volume probes (empty, dipped, pea-size, ½, level spoon; empty, 2 mL, 3 mL cup). Prior to sessions, the feeder initially modelled DRA contingencies to Maia with role play (e.g., “when we take a bite, we watch television”) for approximately 5 min. Maia was able to choose the television show in the same manner as baseline, and the opportunity to choose was provided at the start of each meal block. At the start of a DRA session, the television was off and brief instruction was provided. The spoon was presented to Maia every 30 s with the instruction “take a bite.” If Maia accepted the bite, the feeder provided praise and immediate access to television for 30 s (i.e., the contingency was applied to acceptance). Following a mouth clean check, the television was paused, and the next bite was presented. If Maia did not accept the bite within 5 s, television access was not provided, and the spoon was withdrawn for approximately 30 s, before the next trial began. Mastery criteria at each volume was set at two consecutive sessions at mouth clean 80% or higher. The terminal goal for purees was set at a level maroon spoon, with overall meal volume to be at least 100 g (based on dietitian recommendation to reduce tube feeds).

Caregiver implementation

By Day 7 of the intensive period, Maia was successfully consuming pureed foods fed by an adult. Outside of sessions her parents observed increased consumption of formula from a spoon and offered this during dinner time. Maia’s mother was trained to implement procedures for pureed foods. Behavioural skills training comprised a combination of (1) verbal and written instructions for the procedures, (2) modelling in which the researcher demonstrated correct implementation, (3) caregiver rehearsal, and (4) feedback both immediately and at the end of the meal (Miles & Wilder, Citation2009).

Goals for advancement developed with Maia’s parents included: (1) to continue to increase volume of purees consumed, (2) to increase formula consumption from an open cup, and (3) to increase self-feeding of soft textures. Maia already demonstrated independence with self-drinking water from an open cup, thus self-drinking was targeted. Maia also demonstrated independence with self-feeding a few selected foods, and her speech therapist approved the goal to increase consumption of soft-cooked and dissolvable foods. The resumption of Covid-19 stay-at-home orders delayed researcher visits by a further week, but puree intervention sessions or other baselines were conducted by the caregivers in this period via Zoom. Thereafter, researcher visits occurred twice weekly during afternoon meals, focusing on self-drinking and self-feeding. Maia’s caregivers implemented all intervention sessions for self-feeding and self-drinking. Behavioural skills training was applied in a similar manner as described for purees when intervention was applied to each goal domain. The researchers discussed progress and answered questions from Maia’s caregivers in between sessions.

For self-feeding the same DRA intervention was applied as for purees. At the start of the session, brief instruction was provided “when you take a bite, you can watch _____.” If Maia was not eating, the verbal instruction “take a bite” was repeated approximately every 30 s. When Maia self-fed a bite, the television was provided for 30 s, after which the show was paused, and a mouth clean check was conducted. Volume fading was not systematically applied, however bite sizes gradually increased over the course of caregiver implementation. Similar to baseline, no physical guidance or assistance was provided by the caregivers unless Maia required assistance with the utensil (e.g., attempting to spear a food with the fork). When food textures increased, Maia’s caregivers often consumed similar foods and modelled chewing (e.g., “watch me, like this”). The criterion for mastery of a specific food type was 80% bites consumed (4 out of 5) across At least two sessions before it was replaced with another novel food. As foods were mastered, they rotated into the “preferred” section of the plate. We included caregiver-reported information from meals (pre- and post-plate photos) when researchers were not present to inform food rotations. The goal was for Maia to consume at least 80% of bites for 20 foods (five foods from each food group).

Self-drinking procedures were generally the same as those previously described for purees. Initial volume probes informed the initial starting point (empty, 2 mL, 3 mL cup). The instruction provided was “take a drink” and initial sessions involved the researcher modelling drinking with a separate cup. Following instruction, if Maia accepted the drink, immediate access to the television was provided. If she did not self-drink within 15 s, television access was not provided, and the cup was withdrawn for approximately 30 s, before the next trial began. Mastery criteria at each volume was set at two consecutive sessions at mouth clean 80% or higher. The terminal goal for self-drinking was for Maia to consume a 100 mL portion of formula within 15 min (three times per day), as recommended by the dietitian.

Fading reinforcement and researcher visits

A plan for fading mealtime reinforcement (television) was applied during caregiver implementation. Maia’s caregivers were instructed to fade reinforcement for purees after consistent consumption at level spoon volume, after 70 mL portions with self-drinking, and after 20 new foods were introduced in self-feeding meals. Fading included the television being provided for 30 s after 1) every 2–3 drinks/bites, 2) upon ½ the drink/plate volume/portion consumed, and 3) upon the entire volume consumed (self-drinking) or at the end of the meal. Maia’s caregivers typically replaced television access with high-fives, thumbs up, tickles, and verbal praise for at least every few bites or drinks consumed. Once Maia reached the terminal goal for a skill (outlined above), researcher visits were faded, by replacing one visit with video call, reducing to once weekly visits.

Follow-up

Follow-up visits were planned at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months from study completion. These visits involved a meal observation relevant to each feeding goal, collection of nutritional data, and general recommendations.

Procedural integrity (treatment fidelity)

Procedural integrity (PI) was measured via direct observation of BCBA- and caregiver-implemented meals in terms of key treatment components specific to purees, self-feeding, or self-drinking. PI was collected for 26% of pureed food sessions, 28% of self-feeding sessions, and 28% of drinking sessions. Key treatment components as noted in procedures included correctly presenting the food or drink, providing instructions, praise, checks for swallowing, and access to the television.

Further measures of PI included correctly preparing the self-feeding food plate, assessed via caregivers remotely sharing meal plate photos (23 mealtimes). As Maia’s intervention advanced, aspects of the protocol were faded, such as mouth clean checks and reinforcement, thus PI scoring was adjusted accordingly. For BCBA-implemented sessions (purees), PI was 100% for all components. For caregivers, PI for purees was 98% for presentations (80%−100%), 100% for prompts, and 96% for consequences (range, 80%–100%). For self-feeding, PI for preparation was 87% (range, 80%–100%), presentations were 92% (range, 80% to 100%), prompts were 100%, and consequences were 90% (range, 75% to 100%). For self-drinking, PI was 100% for presentations, 88% for prompts (range, 60–100%), and 86% for consequences (range, 60–100%).

Secondary outcomes: social validity and caregiver stress

At the end of the intervention, social validity was evaluated using a consumer-informed survey specific to caregivers of tube-dependent children (Anderson et al., Citation2022). The survey contained 23 questions with a 7-point Likert scale (Supplementary Information). Following the satisfaction questionnaire, caregivers also took part in an open-ended interview with the researchers, as part of the standard study protocol. The interview provided the opportunity for caregivers to discuss survey responses or anything that was not captured in the survey.

In terms of caregiver stress, Maia’s mother completed the Pediatric Inventory for Parents (PIP; Streisand et al., Citation2001) prior to intervention (end of waitlist period) and post-intervention. The PIP is a well-established measure of caregiver stress in the context of chronic illness. Total and subscore scales were compared at pre-and post-treatment, with a higher score indicating higher stress levels. Statistical analyses were not possible for one single case but will be conducted as part of a future group outcome study.

Results

Primary outcome: behavioural measures

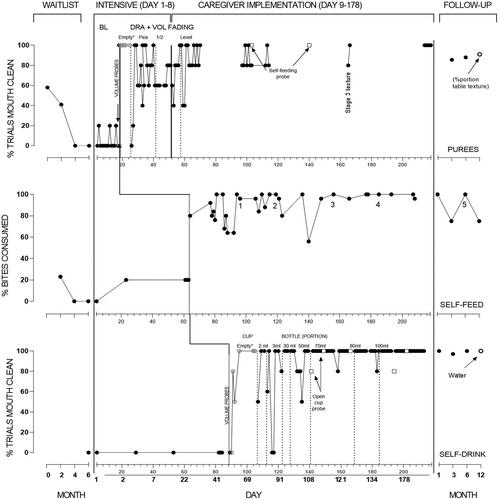

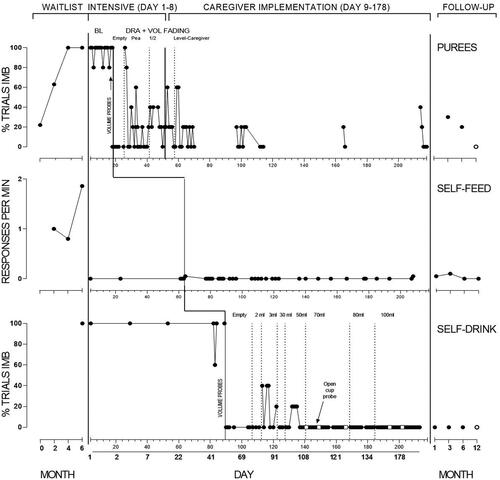

displays mouth clean (consumption) across purees, self-feeding, and self-drinking, and IMB is presented in . Each panel displays study phases including waitlist, intensive period (baseline, intervention), caregiver implementation, and follow-up. For ease of interpretation of the entire timeline, days are included in the top figure labels, and are represented under sessions in the bottom x-axis. Further, the reader may refer to for an overall timeline. Initially the intervention involved an intensive phase whereby multiple sessions occurred on a day. The number of sessions per day then reduced over the caregiver implementation period (i.e., during 1–2 weekly visits).

Figure 1. Mouth clean (consumption) for Maia across puree, self-feeding, and self-drinking sessions.

Note. Sessions are indicated on each x-axis, with the overall timeline of corresponding days on the bottom panel. For purees, the final three baseline sessions were conducted by the BCBA. During intervention for purees and self-drinking, * indicates that acceptance was scored for empty spoon/cup. In panel 2 (self-feeding), texture/volume advancements are noted as follows (1) 2 × 2 cm, (2) 3 × 3 cm, (3) bite-off soft regular (e.g., cheese stick, cooked carrot stick, sandwich quarters, cooked chicken), and (4) raw regular (e.g., strawberry, pear).

Figure 2. Inappropriate mealtime behaviour (IMB) for Maia across puree, self-feeding, and self-drinking sessions.

Note. Sessions are indicated on each x-axis, with the overall timeline of corresponding days on the bottom panel. For purees, the final three baseline sessions were conducted by the BCBA.

Table 1. Outline of overall timeline of treatment.

For purees (panel 1), Maia’s initial consumption was 58%, which declined over subsequent waitlist observations to zero, concurrent with increasing IMB. At the commencement of the intensive phase, baseline data showed consumption was low but variable ranging between 0 and 20%, and IMB over 80%, including during BCBA-implemented sessions. Three sessions where the television was off (not depicted) showed consumption stable at zero and IMB at 100%.

Informed by volume probes (0% acceptance except for empty spoon; 100%) DRA commenced with an empty spoon with acceptance remaining at 100%. Consumption decreased upon increased volume but improved to meet mastery at each spoon volume. Maia’s mother started to implement procedures from Session 47. Caregiver implementation continued with a level spoon, and Maia’s consumption increased to high levels. From Session 103, probes for self-feeding purees were conducted, showing 100% consumption. However, Maia’s caregivers stated preference to continue adult-feeding purees as they considered it more efficient. Videos of caregiver-implemented meals were provided infrequently, but showed consumption remaining above 80%. During caregiver implementation Maia’s caregivers chose not to fade reinforcement during puree food sessions, indicating preference to fade this during follow-up.

For self-feeding (panel 2), Maia’s frequency of consumption during waitlist observations was initially at low levels and decreased to zero with high levels of IMB. During the intensive period, consumption was low in baseline (20%), with Maia only consuming familiar food from the plate. IMB was at zero, as Maia typically ignored the rest of the foods on the plate. Upon the introduction of DRA, Maia’s consumption increased markedly with 80% or higher consumption across the majority of sessions, with IMB remaining at near-zero levels. Numbers on this panel denote where general advancements to bite-size or texture occurred. Advancements were as follows: (1) 2 × 2 cm, (2) 3 × 3 cm, (3) bite-off soft regular (e.g., cheese stick, cooked carrot stick, sandwich quarters, cooked chicken), and (4) raw regular (e.g., strawberry, pear). At the end of the intervention period, Maia’s caregivers had faded reinforcement during self-feeding meals, but Maia could access television or other chosen preferred activities after the meal. Maia’s caregivers presented all foods in regular form at this stage including vegetables (raw carrot) and meats (e.g., lamb chops, chicken wings).

For self-drinking (panel 3), consumption was zero with IMB at 100% of trials during baseline. This is despite Maia consuming formula from a spoon during caregiver meals (dinner time), and consumption of water from an open cup (data available from the author). Similar to purees, volume probes informed the initial starting point, and DRA was applied with an empty cup. Performance was high with an empty cup, IMB was at zero, and volume progressed to 3 mL. An increase in IMB initially occurred with decreased and consumption increased to 100%. Following 3 mL, the goal was for Maia to finish an overall portion of 30 mL from the cup during the session. At this point Maia’s caregivers highlighted a preference for Maia to use a child’s drink bottle (with straw). This was in view of plans for Maia to enter daycare, and to avoid spills with increased volume. Data from this point forward therefore represent percentage of trials consumption from the straw bottle, but open cup probes were continued (open circles). Consumption from the bottle remained high, with overall volumes increasing to 100 mL, and IMB at zero. Open cup probes showed consumption to be 80% or higher. By the end of intervention Maia’s caregivers had partly faded reinforcement for self-drinking (providing television after every few drinks).

Follow-up

Follow-up was conducted via video call at 1, 3, and 6 months owing to Covid-19 restrictions, and in-person at 12 months. Owing to time constraints each goal could not be evaluated at each follow-up. Follow-up data for purees could not be collected at 1 month, but caregivers indicated consistent consumption via oral intake records. Further timepoints showed some decline in consumption, with increased IMB, which improved over subsequent timepoints. Data for self-feeding and drinking generally showed maintenance of effects.

Maia’s caregivers continued to fade reinforcement (television) for purees and self-drinking, with the use of television ceased from 6 months. Between the 6 and 12-month follow-up, Maia’s caregivers reported two periods of illness including Covid-19. Maia’s parents reported a decrease in eating during these periods which quickly resolved and Maia accepted required medications (oral suspension). At 12 months, Maia was no longer required to drink formula, owing to sufficient variety and volume of foods. She was no longer having pureed foods (besides yoghurt, soup), was self-feeding all meals with appropriate utensils (spoon, fork) or fingers, and was consuming the same meals as other family members. The final data point indicates the percentage consumed of a typical family meal (Spaghetti Bolognese with sauce and mince). The final data point for self-drinking was water from a similar straw bottle.

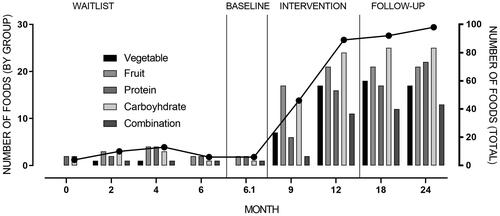

Primary outcome: nutritional measures

Food variety is depicted in . Food variety during waitlist was captured via observation and caregiver food records, showing an average of eight foods consumed, with declining variety just prior to intervention. During intervention, food variety increased to 48 by 3 months, reaching 89 at the end of intervention, including multiple foods across food groups. Follow-up showed further increases in variety to 98 at final follow-up.

Figure 3. Food variety across time points. Number of foods by food group is graphed on left y-axis, with total foods graphed on right y-axis.

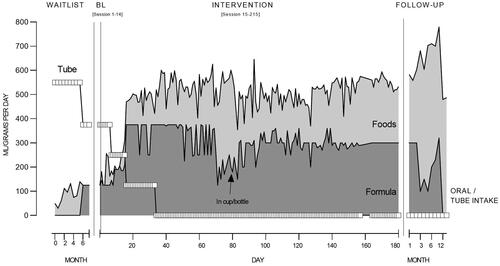

shows Maia’s daily oral and tube intake across the entire study period, with shading to indicate daily formula and food volume. During the waitlist period, Maia’s daily tube intake was 550 mL with oral intake ranging from 30 to 139 g per day. Just prior to intervention, Maia was refusing all foods but had started to accept formula from a spoon (125 mL/g per day), resulting in tube intake reducing to 375 mL per day. During the intensive period, Maia’s daily food intake increased to 100 g per day, with formula continuing at 125 mL per day (via spoon outside of researcher sessions). Tube feeding was subsequently reduced to 250 mL per day by Maia’s dietitian. During caregiver implementation (Day 9 onwards), oral intake continued to increase as Maia’s caregivers implemented further meal opportunities across the day, and further reductions to tube feeding were approved by the dietitian based on Maia’s intake and body weight. Oral intake showed some variability but continued on an increasing trend, to levels between 550 and 600 g per day. Based on intake and body weight, Maia’s dietitian recommended that the NG tube be removed from Day 34. As Maia progressed with self-drinking, Maia’s parents offered more formula in the cup/bottle (instead of spoon), with all formula provided in the bottle from Day 79. Oral intake generally remained at high levels. On Day 83 and 127 Maia was reported unwell, coinciding with reduced oral intake. It is important to note that common dietitian practice in New Zealand is to reduce tube feeding amounts over a period, as opposed to meal-by-meal reductions. In terms of body weight, Maia’s weight was initially 7.2 kg, and gradually increased over the intervention to 7.8 kg (tracking along <0.4th percentile), which was determined appropriate by her dietitian alongside tube feeding reductions.

Figure 4. Maia’s daily oral and tube intake.

Note. BL = Baseline. Note that formula was initially provided via spoon by Maia’s caregivers. From Day 79, formula was provided only in a cup or bottle.

During follow-up, oral intake maintained at high levels and further increased to 600 mL/g per day. At 12-month follow-up, oral intake was reported as lower (480, 487 g per day), but consisted of regular textured table foods and was stated as appropriate for growth and nutrition by Maia’s dietitian. At this point Maia was no longer prescribed any formula (nor milk requirements). In follow-up her weight further increased at each timepoint, to 9.5 kg (0.4th percentile) at 12-month follow-up.

Secondary outcomes: social validity and caregiver stress

displays social validity scores categorized into general caregiver-reported themes (Anderson et al., Citation2022). Maia’s caregivers generally provided high to very high scores for all questionnaire items, with a mean score of 6 post-intervention (range, 5–7). Maia’s caregivers provided a high score (6) for the intervention being culturally appropriate. Post-intervention, specific items that scored lower included those related to procedures (“The techniques we were taught were highly effective/easy to use,” scores of 5), and the overall requirements of the process (“It was easy to keep up with the required information recording,” score of 5). During the open-ended interview, Maia’s caregivers reported that DRA felt difficult to implement initially as they were accustomed to leaving the television on. Further, their work demands during the pandemic resulted in shortened time for Maia’s meals and food preparation. Maia’s parents also felt that adequate oral intake (to reduce tube feeding) took time to achieve, and that recording oral intake data was effortful, but helped to track and share progress with the dietitian. Maia’s parents expressed relief at the NG tube being removed, and felt that tube removal contributed to further progress with food textures and chewing. Overall Maia’s caregivers felt that improving eating would not have been possible without the intervention, and reported that they had previously “tried everything.” Generally, higher scores were noted at final follow-up (mean of 6.1, range 6–7), when compared with post-intervention.

Table 2. Caregiver mean score (range) for each social validity theme.

Maia’s mother’s PIP scores are presented in . The original authors of the PIP do not suggest interpretation brackets, but pre-treatment stress scores were similar to other clinical populations (Streisand et al., Citation2001). Comparing pre- and post-treatment, difficulty scores across subdomains were substantially lower. The overall frequency score had also reduced, albeit less substantially. While two subdomains (communication, role function) showed small increases in frequency scores, corresponding difficulty scores were lower. Whilst full interpretation is difficult, these findings reflect that the intervention had a positive impact on overall stress levels.

Table 3. Pediatric Inventory for Parents (PIP) score at pre- and post-intervention.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to evaluate intervention provided across key goal areas, to ultimately support the transition from tube feeding to eating. Further, we aimed to evaluate caregiver implementation over a longer-term period, as well as report behavioural and nutritional outcomes. Overall, Maia successfully met all three family-selected goals, ceased tube feeding, and maintained progress over the longer-term.

A key strength of the current study is progress reporting with respect to key clinical goals, including longer-term follow-up (Foxx, Citation2013; Taylor & Taylor, Citation2023; Williams & Seiverling, Citation2022). This study fills a gap in the existing behaviour-analytic feeding literature, in which there tends to be a focus on a narrower analysis of an intensive treatment or later skill advancement, but without the overall timeline of intervention. Our findings support those of Hansen and Andersen (Citation2020), who reported the full process of treatment including caregiver implementation, for a child with tube dependency. However, the current study was conducted entirely in the home setting, and adds to the increasing body of international literature demonstrating the effectiveness of home-based behavioural interventions for paediatric feeding disorders (Taylor, Purdy, et al., Citation2019; Taylor et al., Citation2021).

DRA and volume fading successfully increased consumption of pureed foods and self-drinking formula, and DRA alone increased self-feeding. Although past studies have succeeded in improving food acceptance through the use of reinforcement schedules such as DRA in combination with antecedent procedures, it is seldom for these improvements to be obtained without using an escape extinction (EE) procedure (e.g., Bachmeyer et al., Citation2013; Berth et al., Citation2019; Sharp et al., Citation2015; Wilkins et al., Citation2014). For instance, Berth et al. (Citation2019) compared the effects of DRA, noncontingent reinforcement (NCR), and the relative effects of EE. They found that EE was a required component to increase acceptance and that positive reinforcement, specifically DRA, enhanced the EE component. Further, DRA also produced faster skill acquisition and a decrease in IMB. It is also important to note that Maia’s caregivers stated discomfort with extinction-based procedures when initially described, given history of feeding attempts, and Maia having an nasogastric tube.

Also with regards to self-feeding and self-drinking, Maia had pre-requisite skills in this domain (prior food consumption, prior water from cup consumption), and thus did not require further contingencies beyond DRA (Peterson et al., Citation2017; Rivas et al., Citation2014) or specific chew training besides adult modelling (e.g., Volkert et al., Citation2014). A few studies show similar findings (e.g., DRA for self-drinking; Peterson et al., Citation2015), but participants have commonly received prior extinction-based treatments.

The contrasting result of the current study may be attributed to multiple participant characteristics. Compared with existing literature, Maia was of a comparatively younger age, had prior eating experience, less duration of tube feeding, was typically developing, and had no specific oral motor deficits. However, as evidenced by waitlist data over six months, sufficient outcomes were not achieved or sustained from standard care from other disciplines. Regarding the waitlist period, Maia’s caregivers did note that waiting for intervention to begin was difficult. However, the current clinical trial does not have the resource to shorten waitlist periods, due to a lack of BCBA’s that can provide the intervention in New Zealand. Upon further resourcing it will be beneficial to evaluate data-based comparisons with shorter waiting periods.

Overall, access to behaviour analytic intervention earlier may promote more efficient and least intrusive intervention that establishes progression of feeding skills, and is more cost-effective (Ibañez et al., Citation2020; Taylor, Purdy, et al., Citation2019; Taylor & Taylor, Citation2021b; Williams et al., Citation2007). Very few behaviour-analytic studies report early intervention, or when a nasogastric tube is still in place, but this is likely due to gastrostomy tube placement occurring earlier. Future research should concentrate on earlier access to intervention, to obtain more data regarding the use of specific procedures.

A further strength of the current study is the emphasis on caregiver involvement and implementation. Maia’s mother (and often father) were present during all sessions initially implemented by researchers and then implemented all procedures. Procedural integrity was generally at high levels for measured components. Of the reviewed literature, most studies conduct caregiver training, but do not report longer-term caregiver implementation.

In this study we attempted to evaluate generalization within a multiple probe design, and used sequential modification, whereby intervention was provided for subsequent skills upon lack of generalization (Arnold-Saritepe et al., Citation2023; Stokes & Baer, Citation1977), Skill areas were topographically different and time constraints prevented other strategies (e.g., intervening for self-drinking earlier). While we did not evaluate other generalization strategies, they are a common part of study procedures, such as common stimuli (home environment, caregivers in meals from the outset) and multiple exemplars. In future research it would be of interest to further evaluate planning for generalization within paediatric feeding interventions.

One issue related to overall integrity (or, adherence) in this study related to agreement with recommendations for goal advancement. It was important for Maia to learn to self-feed with a spoon, and probes showed that Maia could independently self-feed, despite it taking longer and resulting in some spills. However, Maia’s caregivers were concerned about meal length and volume. This was mostly related to their full-time work from home schedules during the pandemic, where they preferred briefer meals to achieve volumes required for Maia’s tube feeding reductions. Further in relation to self-drinking, Maia’s caregivers did not see the value in continuing open cup drinking when volumes increased, stating preference for less likelihood of spills. Lastly, Maia’s caregivers also stated preference to fade DRA later in follow-up. Given the historical use of television in Maia’s meals, our intervention was noted as difficult but more acceptable to Maia’s caregivers than attempting alternative procedures. Whilst an intervention involving television access may be contrary to general mealtime advice (i.e., remove all distractions; Taylor & Taylor, Citation2021a), our data actually showed that behaviour worsened if the television was merely turned off.

Overall, Maia’s caregivers reported additional stressors due to regular dietitian weight checks and meal volumes that are inherent to weaning from tube feeding. Despite these potential barriers to skill advancement, the researchers respected caregiver values in the process to conduct intervention in an acceptable manner, and this may have supported sustained caregiver engagement and high social validity ratings (Simione et al., Citation2020). Family values and collaboration are essential to compassionate care and this is another area requiring increased reporting in the literature (Taylor, LeBlanc, et al., Citation2019; Wei et al., Citation2023).

Limitations

We did not conduct observation of all goals at each waitlist visit as goals were not specified fully until nearing intervention. In addition, instructions provided in waitlist observations were those naturally provided by Maia’s parents, in comparison to specific instructions during the baseline phase (“take a bite/drink”). In further studies it may be beneficial to assess standardised goals that would be expected outcomes of intervention, and standardize other elements of the observations (instructions). However, doing so must be balanced with brief observation periods to minimize burden to caregivers over multiple visits, as well as child prerequisite skills (e.g., higher textures may not be safe for some children).

As previously outlined, caregiver agreement with recommendations affected the progression of treatment and data (e.g., change from cup to bottle), and measurement systems differed across skills (e.g., self-feeding). It may have been beneficial to assess self-feeding initially in a trial-based format to obtain equivalent data before moving to portion-based meals.

Lastly, interventions for tube dependency commonly involve a higher frequency of dietitian involvement with respect to tube feeding adjustments. Despite requesting guidelines for meal-by-meal reductions (i.e., reducing the next tube feed based on oral intake in the prior meal; Hansen & Andersen, Citation2020), dietitian preference was to recommend longer-term changes based on weight and a period of oral intake. We recognise that this method is not ideal (e.g., may increase vomiting), particularly for children who may be sensitive to increased volume. However, it may be a safer approach to reducing tube feeding in advance of oral intake (i.e., hunger provocation), particularly for children with a history of faltering growth (Taylor, Virues-Ortega, et al., Citation2021). and allows for skill development to be prioritized over volume. In addition, Maia’s parents were provided with guidelines from the dietitian to stop tube feeds upon signs of discomfort.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current study found that a home-based behaviour-analytic intervention was effective in improving several feeding domain areas for a young child, supporting the transition from tube feeding. A strength of this study was being conducted in a home setting, having waitlist data as added baseline points, and having extended long-term follow-up to a year. An initial intensive period supported treatment effectiveness and allowed for efficiency of caregiver training to continue advancement of further feeding goals. Treatment effectiveness was demonstrated across multiple behavioural and nutritional measures and supplemented by ratings of social validity and caregiver stress. This study adds to the body of literature for paediatric feeding disorders, in particular adding to the literature suggesting that a home-based intervention can be suitable for some children and should be accessed as early as possible.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (66 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alshaikh, B., Yusuf, K., Dressler-Mund, D., Mehrem, A. A., Augustine, S., Bodani, J., Yoon, E., & Shah, P. (2022). Rates and determinants of home nasogastric tube feeding in infants born very preterm. The Journal of Pediatrics, 246, 26–33.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.03.012

- Anderson, R., Virues-Ortega, J., Taylor, S. A., & Taylor, T. (2022). Thematic and textual analysis methods for developing social validity questionnaires in applied behavior analysis. Behavioral Interventions, 37(3), 732–753. https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.1832

- Arnold-Saritepe, A., Phillips, K. J., Taylor, S. A., Gomes-Ng, S., Lo, M., & Daly, S. (2023). Generalization and maintenance. In J. L. Matson (Ed.), Handbook of applied behavior analysis for children with autism: Clinical guide to assessment and treatment. Springer Cham.

- Bachmeyer, M. H., Gulotta, C. S., & Piazza, C. C. (2013). Liquid to baby food fading in the treatment of food refusal. Behavioral Interventions, 28(4), 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.1367

- Berth, D. P., Bachmeyer, M. H., Kirkwood, C. A., Mauzy, IV. C. R., Retzlaff, B. J., & Gibson, A. L. (2019). Noncontingent and differential reinforcement in the treatment of pediatric feeding problems. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 52(3), 622–641. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.562

- Foxx, R. M. (2013). The maintenance of behavioral change: The case for long-term follow-ups. The American Psychologist, 68(8), 728–736. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033713

- Greer, A. J., Gulotta, C. S., Masler, E. A., & Laud, R. B. (2008). Caregiver stress and outcomes of children with pediatric feeding disorders treated in an intensive interdisciplinary program. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33(6), 612–620. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsm116

- Hansen, B. A., & Andersen, A. S. (2020). Behavior-analytic treatment progression for a child with tube dependence: Reaching age-typical feeding. Clinical Case Studies, 19(6), 403–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650120950525

- Ibañez, V. F., Peterson, K. M., Crowley, J. G., Haney, S. D., Andersen, A. S., & Piazza, C. C. (2020). Pediatric prevention: Feeding disorders. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 67(3), 451–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2020.02.003

- Jones, E., Southwood, H., Cook, C., & Nicholson, T. (2020). Insights into paediatric tube feeding dependence: A speech-language pathology perspective. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 22(3), 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2020.1754910

- Kempen, J. H. (2011). Appropriate use and reporting of uncontrolled case series in the medical literature. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 151(1), 7–10.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2010.08.047

- Lagatta, J. M., Uhing, M., Acharya, K., Lavoie, J., Rholl, E., Malin, K., Malnory, M., Leuthner, J., & Brousseau, D. C. (2021). Actual and potential impact of a home nasogastric tube feeding program for infants whose neonatal intensive care unit discharge is affected by delayed oral feedings. The Journal of Pediatrics, 234, 38–45.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.03.046

- Marinschek, S., Dunitz-Scheer, M., Pahsini, K., Geher, B., & Scheer, P. (2014). Weaning children off enteral nutrition by netcoaching versus onsite treatment: A comparative study. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 50(11), 902–907. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.12662

- Martinez-Costa, C., Calderón Garrido, C., Borraz, S., Gómez-López, L., & Pedrón-Giner, C. (2013). Satisfaction with gastrostomy feeding in caregivers of children with home enteral nutrition: Application of the SAGA-8 questionnaire and analysis of involved factors. Nutricion Hospitalaria, 28, 1121–1128. https://doi.org/10.3305/nh.2013.28.4.6555

- Mason, S. J., Harris, G., & Blissett, J. (2005). Tube feeding in infancy: Implications for the development of normal eating and drinking skills. Dysphagia, 20(1), 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-004-0025-2

- Miles, N. I., & Wilder, D. A. (2009). The effects of behavioral skills training on caregiver implementation of guided compliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42(2), 405–410. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2009.42-405

- Patel, M. R., Patel, V. Y., Andersen, A. S., & Miles, A. (2022). Evaluating outcome measure data for an intensive interdisciplinary home-based pediatric feeding disorders program. Nutrients, 14(21), 4602. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214602

- Pedersen, S. D., Parsons, H. G., & Dewey, D. (2004). Stress levels experienced by the parents of enterally fed children. Child, 30(5), 507–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00437.x

- Peterson, K. M., Volkert, V. M., & Milnes, S. M. (2017). Evaluation of practice trials to increase self-drinking in a child with a feeding disorder. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 10(2), 167–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-016-0147-7

- Peterson, K. M., Volkert, V. M., & Zeleny, J. R. (2015). Increasing self-drinking for children with feeding disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 48(2), 436–441. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.210

- Reddy, S., & Anitha, M. (2015). Culture and its influence on nutrition and oral health. Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal, 8(october Spl Edition), 613–620. https://doi.org/10.13005/bpj/757

- Rivas, K. M., Piazza, C. C., Roane, H. S., Volkert, V. M., Stewart, V., Kadey, H. J., & Groff, R. A. (2014). Analysis of self-feeding in children with feeding disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47(4), 710–722. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.170

- Sharp, W. G., Trumbull, A., & Lesack, R. (2015). Blending to treat expulsion in a child with food refusal. Behavioral Interventions, 30(3), 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.1413

- Sharp, W. G., Volkert, V. M., Scahill, L., McCracken, C. E., & McElhanon, B. (2017). A systematic review and meta-analysis of intensive multidisciplinary intervention for pediatric feeding disorders: How standard is the standard of care? The Journal of Pediatrics, 181, 116–124.e114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.10.002

- Simione, M., Dartley, A. N., Cooper-Vince, C., Martin, V., Hartnick, C., Taveras, E. M., & Fiechtner, L. (2020). Family-centered outcomes that matter most to parents: A pediatric feeding disorders qualitative study. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 71(2), 270–275. https://doi.org/10.1097/mpg.0000000000002741

- Stevenson, K. (2018). A consultation journey: Developing a Kaupapa Māori research methodology to explore Māori whānau experiences of harm and loss around birth. AlterNative, 14(1), 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180117744612

- Stokes, T. F., & Baer, D. M. (1977). An implicit technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10(2), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1977.10-349

- Streisand, R., Braniecki, S., Tercyak, K. P., & Kazak, A. E. (2001). Childhood illness-related parenting stress: The pediatric inventory for parents. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 26(3), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/26.3.155

- Taylor, T. (2020). Side deposit with regular texture food for clinical cases in-home. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 45(4), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa004

- Taylor, T., Blampied, N., & Roglić, N. (2021). Consecutive controlled case series demonstrates how parents can be trained to treat paediatric feeding disorders at home. Acta Paediatrica, 110(1), 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15372

- Taylor, B. A., LeBlanc, L. A., & Nosik, M. R. (2019). Compassionate care in behavior analytic treatment: Can outcomes be enhanced by attending to relationships with caregivers? Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12(3), 654–666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-018-00289-3

- Taylor, S. A., Purdy, S. C., Jackson, B., Phillips, K., & Virues-Ortega, J. (2019). Evaluation of a home-based behavioral treatment model for children with tube dependency. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 44(6), 656–668. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsz014

- Taylor, S. A., & Taylor, T. (2021a). The distance between empirically-supported treatment and actual practice for paediatric feeding problems: An international clinical perspective. International Journal of Child and Adolescent Health, 14(1), 3–15.

- Taylor, T., & Taylor, S. A. (2021b). Let’s not wait and see: The substantial risks of paediatric feeding problems. International Journal of Child and Adolescent Health, 14(1), 17–29.

- Taylor, T., & Taylor, S. A. (2023). Reporting treatment processes and outcomes for paediatric feeding problems: A current view of the literature. Manuscript Submitted for Publication.

- Taylor, S. A., Virues-Ortega, J., & Anderson, R. (2021). Transitioning children from tube to oral feeding: A systematic review of current treatment approaches. Speech, Language and Hearing, 24(3), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/2050571X.2019.1684068

- Volkert, V. M., Peterson, K. M., Zeleny, J. R., & Piazza, C. C. (2014). A clinical protocol to increase chewing and assess mastication in children with feeding disorders. Behavior Modification, 38(5), 705–729. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445514536575

- Volkert, V. M., Piazza, C. C., & Ray-Price, R. (2016). Further manipulations in response effort or magnitude of an aversive consequence to increase self-feeding in children with feeding disorders. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(2), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-016-0124-1

- Wei, Q., Machalicek, W., & Zhu, J. (2023). Treatment acceptability for interventions addressing challenging behavior among Chinese caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53(4), 1483–1494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05196-1

- Wilken, M. (2012). The impact of child tube feeding on maternal emotional state and identity: A qualitative meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 27(3), 248–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2011.01.032

- Wilken, M., Cremer, V., Berry, J., & Bartmann, P. (2013). Rapid home-based weaning of small children with feeding tube dependency: Positive effects on feeding behaviour without deceleration of growth. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 98(11), 856–861. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2012-303558

- Wilkins, J. W., Piazza, C. C., Groff, R. A., Volkert, V. M., Kozisek, J. M., & Milnes, S. M. (2014). Utensil manipulation during initial treatment of pediatric feeding problems. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47(4), 694–709. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.169

- Williams, K. E., Riegel, K., Gibbons, B., & Field, D. G. (2007). Intensive behavioral treatment for severe feeding problems: A cost-effective alternative to tube feeding? Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 19(3), 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-007-9051-y

- Williams, K. E., & Seiverling, L. (2022). Behavior analytic feeding interventions: Current state of the literature. Behavior Modification, 2022, 014544552210981. https://doi.org/10.1177/01454455221098118