ABSTRACT

Objectives

Posttraumatic growth (PTG) is of increased theoretical and clinical interest. However, less is known about PTG in older adults specifically. This systematic review aimed to identify domains where PTG is studied for older adults; investigate factors associated with PTG in older adults; consider how these might differ between historical and later life traumas.

Methods

Online databases were searched for quantitative studies examining PTG outcomes in adults aged ≥ 60 years.

Results

15 studies were subject to a narrative synthesis.

Conclusions

Older adults can experience substantial levels of PTG, from traumas during later life or across the lifespan, and historical wartime traumas. Traumas can be diverse, some studies found equivalent levels of PTG from different traumas across the lifespan. Social processes may be a key variable for older adults. Additional psychosocial factors are found; however, diverse findings reflect no overall model, and this may be consistent with variations found in other PTG literature.

Clinical Implications

Clinical considerations are discussed. As diverse studies, findings may not be widely generalizable and directions for further research are highlighted. PROSPERO: CRD42020169318.

Introduction

Older adults and trauma

Specific age-related stressors and changes in physical health mean that older adults are particularly vulnerable to significant losses, illness, and other highly challenging experiences. Trauma experienced in earlier life may also have sequelae in later life, as well as the effects of chronic and lifelong traumatic experiences (Foster, Davies, & Steele, Citation2003; Raposo, Mackenzie, Henriksen, & Afifi, Citation2014; Rintamaki, Weaver, Elbaum, Klama, & Miskevics, Citation2009). Most adults (50–90%) have experienced trauma by the time they reach older age (Pless Kaiser, Cook, Glick, & Moye, Citation2019). Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) rates are, however, significantly lower for older adults and who may experience less traumatic experiences overall (Pless Kaiser et al., Citation2019; Reynolds, Pietrzak, Mackenzie, Chou, & Sareen, Citation2016); although there is suggestion these are likely to be under-reported and under-recognized (Cook, McCarthy, & Thorp, Citation2017). Whilst not frequent, the impacts of trauma and PTSD can lead to significant problems for older adults (Cook et al., Citation2017; Durai et al., Citation2011; Maercker et al., Citation2008). PTSD can lead to daily life impairments, decreased satisfaction, receiving lower-level care, older subjective age, and associations with physical health problems, disability, cognition, and considerable psychiatric comorbidity and psychosocial dysfunction, including depression and anxiety (Byers, Covinsky, Neylan, & Yaffe, Citation2014; Lapp, Agbokou, & Ferreri, Citation2011; Pietrzak, Goldstein, Southwick, & Grant, Citation2011; Schuitevoerder et al., Citation2013). Impacts of lifetime trauma can be wide ranging, impacting on life satisfaction (Krause, Citation2004), and rates of substance and alcohol use disorders where other mental health disorder rates are low (Williamson, Stevelink, Greenberg, & Greenberg, Citation2018).

Posttraumatic growth

Posttraumatic growth (PTG) is defined as, “positive psychological changes experienced as a result of the struggle with trauma or highly challenging situations” (Tedeschi, Shakespeare-Finch, Taku, & Calhoun, Citation2018, p. 3). Growth following a traumatic experience can lead to positive changes in one’s perception of self, experience of relationships with others, and general philosophy of life. PTG does not signify the absence or necessarily reduction of negative psychological and health impacts of trauma but describes a phenomenon where psychological growth is experienced alongside. PTG is therefore a separate, distinct process to decreases in posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS).

Whilst PTG’s clinical utility and legitimacy are controversial for some (Zoellner & Maercker, Citation2006), it has become increasingly interesting to researchers and clinicians in understanding a beneficial response to trauma and nonetheless been related to increased positive mental health, reduced negative mental health, and better subjective physical health, well-being and functioning (Boehm-Tabib & Gelkopf, Citation2021; Sim, Lee, Kim, & Kim, Citation2015; Tedeschi et al., Citation2018). Despite similarities to several proceeding and overlapping concepts, PTG, defined in 1995, has evolved into a specific and definitive model by Tedeschi et al. (Citation2018), emphasizing transformational changes as a response to the challenges to one’s core beliefs following genuine traumatic events. Consequently, a formal PTSD diagnosis is not a pre-requisite for experiencing PTG and trauma is defined more broadly as a life-altering event seismic enough to impact on one’s assumptive world, prioritizing one’s subjective response to significantly challenging events. Such traumatic events may include, for example, significant losses but not daily stressors. Furthermore, traumatic ‘events’ need not be confined to a specific incident but may refer to cumulative trauma or several related events occurring over time. The PTG process involves the development of deliberate and constructive rumination, self-analysis and self-disclosure, via sociocultural influences, leading to acceptance and growth. PTG can be measured using the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) (Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation1996), specifying five factors: relating to others (RO), new possibilities (NP), personal strength (PS), spiritual change (SC) and appreciation of life (AL).

PTG should be distinguished from resilience, for which there is a large literature relating to older adults, as high levels can exist (Gooding, Hurst, Johnson, & Tarrier, Citation2012; Hamarat, Thompson, Steele, Matheny, & Simons, Citation2002; Netuveli, Wiggins, Montgomery, Hildon, & Blane, Citation2008), and which may be important for supporting successful aging (MacLeod, Musich, Hawkins, Alsgaard, & Wicker, Citation2016; Taylor & Carr, Citation2021). Whereas resilience describes one’s ability to bounce back from, to resist or adapt well in the face of difficulties without prolonged negative effects (Rutter, Citation1985), PTG results from the ‘struggle’ with difficult circumstances (Tedeschi & Blevins, Citation2017). Conceptually, those who are more resilient to negative event impacts may engage less in PTG, although individuals with PTG experiences could be more resilient. However, research has produced mixed findings regarding this relationship (Tedeschi et al., Citation2018). Regardless, PTG provides a different framework in helping to identify how older adults might move forward when events are experienced as more traumatic.

PTG in later life

PTG is firmly established within a broad range of settings and traumas, including for example, bereavement, interpersonal violence and illness (Elderton, Berry, & Chan, Citation2017; Koutrouli, Anagnostopoulos, & Potamianos, Citation2012; Michael & Cooper, Citation2013). Such reviews have demonstrated that PTG can be observed following various traumas, whilst indicating several disparate factors involved, including demographics, social support, coping strategies, subjective appraisals, religion, and those trauma specific. Research often includes all age groups, but rarely focuses exclusively on older adults, making precise conclusions about later life PTG difficult to extrapolate. Nuccio and Stripling (Citation2021)’s scoping review examined resilience and PTG following late life polyvictimization, identifying a limited amount of research conducted on PTG in this context and mixed findings regarding PTG’s role on later life PTSD. Furthermore, little has been studied in how age-related changes might influence PTG processes, although common changes in cognitive or social functions are likely to be relevant. PTG has frequently been observed following traumatic brain injury (Kinsella, Grace, Muldoon, & Fortune, Citation2015), whilst in Eren-Koçak and Kiliç (Citation2014)’s study of working age adults following an earthquake, growth was predicted by executive functions, but not memory or processing speed. As PTG requires cognitive processing of one’s trauma response, functional deficits in this domain may theoretically influence growth, however more research is needed to understand these relations. Social support is an established factor in PTG (Prati & Pietrantoni, Citation2009) and will be important to consider in the context of later life where changes in one’s social environment, relationships, and approaches to these are common. For example, older adults often experience reduced but more positive relationships (Lang, Citation2001; Luong, Charles, & Fingerman, Citation2011).

Later life psychology is also relevant, as older adults may manage challenging experiences differently. Relevant models include the accumulation of experiences that allows the de-emphasis of negative events and selective optimization of positive experiences (Shrira, Shmotkin, & Litwin, Citation2012), positive reappraisal in older adults (Nowlan, Wuthrich, Rapee, & Health, Citation2015), and developing acceptance strategies for managing life challenges (Baltes & Baltes, Citation1990). Indeed, research has consistently found that age can inversely impact the likelihood of PTG. One review found a higher combined prevalence of moderate-to-high PTG in those under 60 years to those older (Wu et al., Citation2019), whilst an inverse relationship between age and PTG was found in adults aged 20–70 years (Manne et al., Citation2004).

Given that later life presents specific age-related challenges, alongside changes that might influence PTG processes, a developed understanding of later life PTG should be explored.

Objectives

This study aimed to summarize and review literature explicitly considering PTG in older adults. Specific aims:

Identify domains in which PTG is studied for older adults

Identify factors associated with PTG in older adults

Consider any differences in factors relating to historical and later life traumas

Methods

Search strategy

This systematic review was conducted according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Group, Citation2009) and registered on the international prospective register of systematic reviews PROSPERO (CRD42020169318). The same search was conducted over six databases (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, PILOTS, Science Direct and Web of Science) on 24th June 2020 and 7th October 2021 (for articles since June 2020). Two separate searches were combined for older adults and PTG. MeSh terms were used, where possible. MEDLINE’s full electronic search: ((MM “Posttraumatic Growth, Psychological”) OR “posttraumatic growth” OR “post-traumatic growth” OR “post traumatic growth”) AND ((MH “Aged”) OR (MH “Aged, 80 and over”) OR “older adults” OR “older people” OR “elderly” OR “geriatric” OR “geriatrics” OR “aging” OR “ageing” OR “senior” OR “seniors” OR “aged 65” or “65+”), limited to English language, journal articles and published date 1995 to present. EndNote software was used to manage citations and Microsoft EXCEL for study data.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included for review if published in English since 1995, in online peer-reviewed journals with available full text and presenting quantitative data. No study methodology types (e.g., RCT, cohort), except qualitative studies, were excluded. The study’s entire (primary) sample was required to comprise of adults aged ≥ 60 years. Studies were required to measure and draw conclusions on PTG outcomes.

Researching older adults is problematic due to varying definitions of older adulthood and mixed samples included in studies (Shenkin, Harrison, Wilkinson, Dodds, & Ioannidis, Citation2017). This review defined older adults as aged ≥ 60 years (World Health Organisation, Citation2018) and excluded studies reporting mixed samples below and over 60 years, unless including a primary sample of adults aged ≥ 60 years, a direct comparison between these groups, and distinct conclusions about the older adult population.

This review operationally defined PTG in line with Tedeschi et al. (Citation2018)’s PTG model, with eligible studies required to (a) use the term ‘posttraumatic growth’ and (b) investigate PTG within the model’s intended meaning, by relating to a specific traumatic event or through a validated PTG measure. As described, trauma type was not scrutinized, so long as PTG was measured in relation to a perceived traumatic event. Only studies published from 1995, when the term was introduced, were included. PTG is commonly conflated with several overlapping terms, including, stress-related growth, benefit finding, thriving, flourishing, and resilience, which Tedeschi et al. (Citation2018) argue cannot reliably be synonymous in meaning, despite often associated or used interchangeably. To aid theoretical precision, studies only using such terms were excluded.

Screening

All studies’ titles and abstracts, and full text demographic information where necessary, were assessed. Papers were removed where not meeting format or study type criteria, clearly unrelated to older people and/or PTG, and where older people formed part of a mixed sample but not specifically delineated. Next, full texts were obtained where possible. Where studies did not report minimum ages, attempts were made to contact authors, and excluded if no response. Appropriate exceptions were made, such as recent studies examining Second World War (WW2) survivors. Papers including mixed samples or comparing older and younger samples but delineating some results for older adults were excluded due to none or insufficiently drawn conclusions for older adults. Papers were excluded where PTG was not satisfactorily addressed, such as reporting perceived growth over time, rather than following an identified traumatic event.

Data extraction

Data extracted from included studies related to: study characteristics (design, objectives, outcomes, and context), participant characteristics (demographics, samples), study outcomes, and outcomes and factors analyzed specifically in relation to PTG and older adults. These included: main findings, types of trauma, measures, and timescales of trauma, social and psychological processes, positive or negative outcomes, demographic factors, and any specific considerations for older adult PTG.

One reviewer extracted study data, whilst a second reviewer checked accuracy for 20% of studies. Any disagreements were resolved together.

Assessment of study quality

Quality assessment was conducted on included studies. To effectively and meaningfully appraise studies, the authors developed a bespoke 22-item tool, based on systematic review guidelines for quality assessment (Higgins & Green, Citation2011), and other established measures for specific study designs. Existing measures were consulted but deemed unsuitable given the review’s specific focus. The tool allowed a consistent appraisal of key quality features across study types, and review topic relevance; a detailed assessment of each study whilst maintaining inter-rater reliability.

Ratings (good, acceptable, poor) were allocated for items relating to selection of participants, study design, outcomes, review topic relevance, and comparability and intervention where applicable. Scores guided an overall appraisal and comparison of each study’s quality and risk of bias consistent with guidance of risk of bias assessment (Higgins et al., Citation2011). The quality ratings process mirrored that of data extraction. As a novel tool without standardized cutoffs, a 70% score, similar to cutoffs interpreted for other measures e.g. Islam et al. (Citation2016), was used to determine studies as ‘good,’ as well as ‘fair’ (>50%) and ‘poor’ (<50%). Ratings were used as a guide only.

Narrative synthesis

Narrative synthesis was deemed appropriate for this exploratory review, concerned primarily with the description, exploration, and interpretation of factors between studies (Pope, Mays, & Popay, Citation2007). In addition, a large heterogeneity of study methodologies, populations, and factors, meant that a statistical meta-analysis of data would not be meaningful in representing the diversity of data and studies (Campbell, Katikireddi, Sowden, McKenzie, & Thomson, Citation2018; Popay et al., Citation2006). Relevant effect sizes are inlcuded in online supplement table 2.

The narrative synthesis was based on the principles of framework synthesis (Brunton, Oliver, & Thomas, Citation2020; Gough, Oliver, & Thomas, Citation2017; Oliver et al., Citation2008), providing an integrative, structured, and transparent way of organizing and interpreting data within a clearly defined review question. This allowed for both pre-defined and emerging categories and potential for theorizing implications, particularly as data were disparate and largely descriptive. Between authors there was experience of working clinically, researching, and publication in the fields of PTG and older people separately. However, this was their first project examining PTG in older people. One author initially completed the synthesis independently and was then developed by all authors.

Prior to the review, the first author familiarized themselves with the PTG literature through relevant sources and literature scoping. An initial framework was developed from this and previous PTG reviews, e.g., Meyerson, Grant, Carter, and Kilmer (Citation2011) for the a priori data extraction categories. Following searching/screening, these data were extracted and charted into a framework to compare and contrast, and derive subthemes from factors; including separating historical and later life traumas. Factors were then mapped and interpreted by considering their relevance to PTG in older people and the relevant wider literature. Given the diversity of factors reviewed, over-interpretations or a theoretical model of factors was avoided.

Results

details the study selection process: 16 papers met review eligibility.

Narrative synthesis

Assessment of study quality and risk of bias

Quality rating agreement between raters was excellent (k = .857, p < .001). The overall quality of included studies was deemed good or fair. All studies gave appropriate descriptions of participant selection, design, methods, and justifiable outcomes, allowing synthesis integration. The generalizability of several studies was reduced due to limited study designs, and specific or small samples. shows overall results from the quality rating tool.

Study and participant characteristics

Studies, published between 2008 and 2021, included a total of n = 2373 participants (1967, excluding controls) from varied countries. Two studies (Greenblatt-Kimron, Citation2021; Greenblatt-Kimron, Marai, Lorber, & Cohen, Citation2019) used the same sample but both were included in the review as they identified different factors. Eight studies used a cross-sectional observational design, six case-control, and two were clinical trials; including one randomized control trial (RCT); both trials, conducted by the same authors with different populations, tested the same PTSD intervention. Thirteen studies measured PTG as part primary outcome using the PTGI, the majority validated in their relevant language. Three studies measured PTG as secondary outcome, with three using short-form PTGIs.

Across studies, participants age ranged from 60 to 100 years (primary sample mean age range: 67.7 to 82.7 years). All studies reporting on gender, except two, contained predominately women (range 52% to 100%). Across studies, level of education varied, with reporting differences making interpretations difficult. Married status varied, with most samples including majority married or widowed participants. Ethnicity was diverse. Detailed study and participant characteristics are displayed in online supplement table 1.

PTG study features

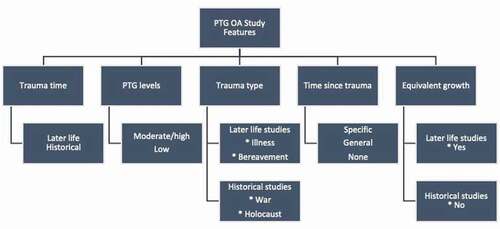

shows a graphical view of study features.

Trauma type, levels, and time since trauma

Seven studies reported traumas occurring in later life or across the lifespan, and nine studies reported historical war-related traumas occurring in early life. Later life studies assessed PTG relating to bereavement (López, Camilli, & Noriega, Citation2015; Oksuzler & Dirik, Citation2019) and illnesses of cancer (Brix et al., Citation2013; Heidarzadeh, Dadkhah, & Gholchin, Citation2016; Hoogland, Jim, Schoenberg, Watkins, & Rowles, Citation2019), diabetes (Senol-Durak & Durak, Citation2018) and living with stoma (Blaszczynski & Turek, Citation2013). Whilst no standardized cut-off for PTGI scores exists, as with Wu et al. (Citation2019), >60% of the highest PTGI score (i.e. 63; SF 3) was used to indicate moderate-to-high levels. PTG levels varied between studies, with notable variation within cancer studies and moderate-to-high scores in bereavement and stoma studies. Whilst overall varied, the highest PTG scores were within later life studies.

Historical trauma studies all related to war: three examining Holocaust trauma (Greenblatt-Kimron et al., Citation2019; Lev-Wiesel & Amir, Citation2003; Lurie-Beck, Liossis, & Gow, Citation2008), two describing interventions for PTSD (Böttche, Kuwert, Pietrzak, & Knaevelsrud, Citation2016; Knaevelsrud et al., Citation2014) and individual studies examining decorated veterans (Stein, Bachem, Lahav, & Solomon, Citation2020), sexual violence (Kuwert et al., Citation2014), and former child soldiers (Forstmeier, Kuwert, Spitzer, Freyberger, & Maercker, Citation2009). PTG levels varied between these studies; Holocaust studies reported lower PTG levels.

The time since trauma event was only generally or not appropriately described for the majority of later life studies. For example, 60% of Heidarzadeh et al. (Citation2016)’s sample had a cancer diagnosis for more than one year, and the majority of López et al. (Citation2015)’s recorded events were more than three months ago. Timescales were more specifically described within the majority of historical studies.

Equivalent growth

The three later life case–control studies found equivalent levels of PTG across trauma types, including individuals living with a stoma vs other various traumatic events (Blaszczynski & Turek, Citation2013), in widows vs non-widows (López et al., Citation2015) and for women with breast cancer (BC) vs controls (Brix et al., Citation2013). In these studies, participants reported on growth from their chosen most traumatic experience across their lives. This equivalency was not found within the two historical case–control studies, with Holocaust survivors and women with sexual trauma from WW2 demonstrating higher PTG than those with no Holocaust experience or non-sexual trauma (Greenblatt-Kimron et al., Citation2019; Kuwert et al., Citation2014).

Factors associated with PTG in older adults

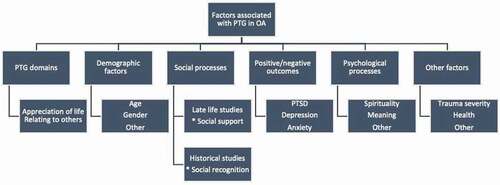

shows a graphical view of identified factors. Additional details of factors are displayed in online supplement table 2; the framework synthesis is shown in online supplement table 3.

Social processes

Social support in later life

Social support was identified as a factor across several later life studies, including positive associations with more children, and perceived family support in diabetic older adults (Senol-Durak & Durak, Citation2018) and with perceived family support from friends and significant others in the bereaved (Oksuzler & Dirik, Citation2019). A reliance on supportive others was important in those with cancer (Hoogland et al., Citation2019), and through a positive relationship between support offered by religious or spiritual communities and PTG (López et al., Citation2015). High PTG levels were found in those part of supportive organizations (Blaszczynski & Turek, Citation2013).

Social recognition for historical traumas

Social recognition was identified in three historical studies. Recognition predicted PTG in former child soldiers (Forstmeier et al., Citation2009); survivor support group membership related to PTG and higher NP, PS, and AL in Jewish Holocaust survivors (Lurie-Beck et al., Citation2008). However, alongside higher PTG, sexual trauma victims perceived less positive acknowledgment as survivors in their personal environment and more family disapproval relative to controls (Kuwert et al., Citation2014). Recognition could also be relevant in Stein et al. (Citation2020)’s finding that decorated vs. non-decorated veterans experienced higher PTG.

PTG domains

Dominant PTG domains were not analyzed in most studies. However, in later life studies, AL was high in both groups of Blaszczynski and Turek (Citation2013), significantly higher in those with BC vs. those without (Brix et al., Citation2013), and the highest scoring domain in Hoogland et al. (Citation2019)’s participants with cancer. Within historical studies, AL had a large effect size in Holocaust survivors (Greenblatt-Kimron et al., Citation2019) and was most associated with Holocaust experience in Lurie-Beck et al. (Citation2008). AL had the largest effect size for decorated veterans when compared to non-decorated veterans (Stein et al., Citation2020).

In later life studies, RO was greater in both groups of Blaszczynski and Turek (Citation2013) and significantly higher in women with BC vs controls (Brix et al., Citation2013). Heidarzadeh et al. (Citation2016) found that RO (alongside SC) was the highest domain in cancer patients.

Psychological processes

Spirituality

In later life studies, spirituality was a factor with PTG in bereavement, with Oksuzler and Dirik (Citation2019) finding PTG enhanced with positive, as well as negative religious coping; in addition to López et al. (Citation2015)’s findings on religious/spiritual community support.

Meaning

Meaning in life was positively associated with PTG and world assumptions in Holocaust survivors, and had a positive mediating effect on their association (Greenblatt-Kimron, Citation2021). Meaningfulness predicted PTG in former child soldiers (Forstmeier et al., Citation2009) and was significantly associated with greater PTG across various later life traumas (López et al., Citation2015).

Other psychological processes

Other psychological processes were not reported in many studies. High levels of acceptance of illness alongside high PTG scores were found in those living with stoma (Blaszczynski & Turek, Citation2013), as well as health locus of control (LOC) dimensions associated with PTG domains. Internal LOC, alongside PTG, predicted better therapy outcomes for PTSD (Böttche et al., Citation2016). Curiosity was negatively associated with SC in those living with stoma (Blaszczynski & Turek, Citation2013), and PTG and all domains associated with hope in cancer patients (Heidarzadeh et al., Citation2016).

Positive or negative outcomes

PTSD

Historical studies found a mixed relationship between PTSD and PTG. Lev-Wiesel and Amir (Citation2003) found PTSD negatively associated and contributed significantly to PTG, Greenblatt-Kimron et al. (Citation2019); Greenblatt-Kimron (Citation2021) found a positive association between PTSS and PTG, and Forstmeier et al. (Citation2009) found that PTSD severity was not correlated with PTG in former soldiers, except intrusive symptoms and NP. Knaevelsrud et al. (Citation2014) and Böttche et al. (Citation2016) saw negative associations between PTG and PTSD during ITT intervention trials with childhood war trauma survivors, with PTG predicting better outcomes for RCT participants (Böttche et al., Citation2016).

PTSD symptoms were positively related to SC in Jewish Holocaust survivors (Lurie-Beck et al., Citation2008) and arousal positively associated with PTG domains in Holocaust survivors (Lev-Wiesel & Amir, Citation2003). In Stein et al. (Citation2020), avoidance was higher over time with lower PTG for non-decorated veterans. Within later life studies, avoidance was positively associated with PTG in those with diabetes (Senol-Durak & Durak, Citation2018) and negatively associated with PTG across later life traumas (López et al., Citation2015).

Depression and anxiety

Two later life studies found PTG (and domains) negatively correlated with depression (Blaszczynski & Turek, Citation2013; Heidarzadeh et al., Citation2016), although the latter found some individuals with concurrent high depression and PTG. Oksuzler and Dirik (Citation2019) found no association between depression and PTG. Blaszczynski and Turek (Citation2013) found PTG negatively associated with anxiety and Stein et al. (Citation2020)’s decorated vs non-decorated veterans experienced lower anxiety and depression with higher PTG. Forstmeier et al. (Citation2009) found depression and anxiety were not correlated with PTG in former soldiers.

Demographic factors

Age

In later life studies, age was negatively associated with PTG, in relation to a range of events across life (Brix et al., Citation2013; Hoogland et al., Citation2019; López et al., Citation2015). Age of childhood survivor (during Holocaust) contributed significantly to PTG (Lev-Wiesel & Amir, Citation2003) and was positively associated with AL in Jewish Holocaust survivors (Lurie-Beck et al., Citation2008). Forstmeier et al. (Citation2009) found age of onset at deployment, or at time of study was not associated with PTG, although their sample had a small age range.

Gender

Only Oksuzler and Dirik (Citation2019) reported notable gender differences, with bereaved women reporting higher PTG. No gender effects were specifically found in several studies (Boettche et al., Citation2016; Greenblatt-Kimron, Citation2021; Knaevelsrud et al., Citation2014; Lev-Wiesel & Amir, Citation2003; López et al., Citation2015; Lurie-Beck et al., Citation2008; Senol-Durak & Durak, Citation2018).

Other demographics

There were mixed findings on the relationship between education and PTG (Knaevelsrud et al., Citation2014; López et al., Citation2015), and positive associations with single status (López et al., Citation2015) and number of children (Senol-Durak & Durak, Citation2018).

Additional factors

Trauma severity

Various severity of cancer domains and time since operation were positively associated with PTG (Brix et al., Citation2013), whilst López et al. (Citation2015) found that traumas where another person’s physical integrity was threatened associated with higher PTG; although a negative association with PTG and number of lifetime traumatic events witnessed. Severity of trauma factors were identified within some historical studies, including a positive association between number of traumatic experiences and PTG in former child soldiers (Forstmeier et al., Citation2009), with sexual trauma victims experiencing higher PTG than non-sexual WWII-related trauma victims (Kuwert et al., Citation2014), and in the nature of Holocaust experiences and whether survivors were alone (Lurie-Beck et al., Citation2008).

Physical health

Higher diet adherence and being an inpatient positively related with higher PTG in those with diabetes (Senol-Durak & Durak, Citation2018). Greenblatt-Kimron et al. (Citation2019) found that Holocaust survivors, along with higher PTSS and PTG, had better heart rate variability (HRV) than controls: higher PTG was related to higher HRV with PTG playing a mediating role in PTSS and better HRV.

Discussion

PTG in older adults

Older adults can experience substantial levels of PTG, both in the context of historical traumas, and from those during later life or across the lifespan. Highest PTG scores were found amongst later life studies, however scores varied across both study types and low scores were also present. Older people might display equivalent levels of PTG from various traumas across the lifespan when examined in later life, but this might not be the case with historical wartime traumas. There was an indication that social processes (support and recognition) are a key factor in PTG for older adults. An association with PTG domains of AL and RO were important across some traumas, whilst PTG may be an important variable in enhancing PTSD outcomes with ITT. There was evidence of a mixed relationship between PTG and PTSD within historical studies, and with anxiety and depression, a negative association between age and PTG in a range of events across the lifespan, associations between PTG and trauma severity across trauma types, and some indication of potential health benefits. A number of psychosocial variables were found to be associated with PTG in older people, particularly spirituality and meaning. However, findings were diverse with no overall model indicating clear relationships between psychosocial factors, trauma, and PTG. Reviewed studies adhered to an appropriate standard of methodology, PTG definitions, and measures. Whilst studies represent diverse cultures, cross-sectional designs, small and culturally specific samples make it difficult to generalize results or establish causality between variables.

Growth domains

Studies may reflect the varied nature of what older people experience as trauma. Whilst studies follow much of the PTG literature’s focus on chronic disease and war; later life health conditions and other significant changes in life or relationships e.g., bereavement, can mean specifically impactful consequences, yet also PTG, for older adults who often experience poorer health, less support and less independence or access to resources. This relates to previous findings that unexpected death or serious illness or injury to someone close were commonly identified as the worst stressful events for older adults (Pietrzak et al., Citation2011).

It should be noted that what was included as trauma in this review depended on what study authors defined as trauma and measured PTG in relation to. Identifying living with diabetes or stoma as trauma may be controversial, despite observations of PTG. As described, the PTG model emphasizes ‘genuine traumatic events’ as needed to trigger PTG but also highlights individuals’ perception of the event, rather than the event itself, as the trigger for PTG processes (Tedeschi & Blevins, Citation2017). Within the context of older adults, there is also an argument that ‘normative’ traumatic events (such as spousal bereavement) are not adequately represented within diagnostic definitions of trauma (Weathers & Keane, Citation2007), although they might be sufficiently challenging to one’s beliefs.

Factors associated with PTG in older adults

The finding of equivalent growth amongst varying types of trauma could relate to an effect of perspective on one’s experiences when examined in later life, with traumas contextualized within a lifespan of multiple challenging experiences (Brix et al., Citation2013). Hoogland et al. (Citation2019) suggests this relates to a lifetime of developing coping strategies/resilience. However, as these differ from PTG, it may be that other factors, such as severity or duration of trauma, are more significantly implicated in PTG levels than simply trauma type (Helgeson, Reynolds, & Tomich, Citation2006; Kira et al., Citation2013). That this was not found within the two historical case–control studies could indicate that certain early life traumas result in greater capacity for PTG when assessed in later life. Or it could indicate that PTG processes were initiated when younger, before later life psychological profiles. Long-term effects of time since event could be implicated, however this is difficult to determine without further and more precise data. Stein et al. (Citation2020)’s findings demonstrate that additional factors, such as those relating to social desirability, expectations, or gains might additionally affect how levels differ when examined later in life.

Social processes

Social support can predict PTG (Dong et al., Citation2017; Sattler, Boyd, & Kirsch, Citation2014), whilst emotional support can offset the effects of trauma on life satisfaction in older adults (Krause, Citation2004). This review suggests social support may be an important factor in PTG with older people; whether in later life: with social support, or from historical traumas with social recognition. Social recognition findings highlight the importance of social expectations and perceptions, considering historical social contexts that might have impacted one’s ability to develop PTG, and how shifts in cultural/social views may open up new opportunities for this later in life. This importance of social processes corresponds with notions that older people can often experience reduced independence and a greater reliance, though less access to, social support systems. Consequently, social contextual interventions, promoting societies inclusive and supportive of older people and providing appropriate social contact might lead to better environments for developing PTG and potentially enhance intervention outcomes.

Additional factors

Whilst additional findings are numerous, generalizations are difficult due to the varied evidence reviewed, and at times contradictory nature of findings, likely reflecting varied samples and contexts, and complexity of the PTG phenomenon. Studies reporting more details on PTG may also be unfairly weighted within these findings. However, such variation and inconsistencies are common within PTG’s literature (Tedeschi et al., Citation2018; Zoellner & Maercker, Citation2006).

PTG domains AL and RO, were notably high within cancer and important in Holocaust studies. AL may have meaning for older people, who have both experienced more life and are closer to its end than younger adults, whilst RO may reflect the importance of social processes and relationship changes in later life.

Some psychological processes previously associated with PTG were found to be supported with older adults, including spirituality (Shaw, Joseph, & Linley, Citation2005) and meaning (Aflakseir, Soltani, & Mollazadeh, Citation2018; Mostarac & Brajković, Citation2021). Within demographic factors, age was negatively associated with PTG in several later life studies, supporting previous findings that PTG decreases with age (Wu et al., Citation2019). In addition, highest reported PTG scores were in later life studies. However, two studies reviewed here report on events from across the lifespan, telling us less about how this might differ within later life. Furthermore, moderate-to-high PTG scores were found in traumas from over 60 years ago, indicating older adults retain capacity for substantial PTG.

The relationship between PTSD symptoms and increased PTG in wartime traumas supports some previous findings (Dekel, Ein-Dor, & Solomon, Citation2012; Schubert, Schmidt, & Rosner, Citation2016); however, this varied between studies, consistent with mixed findings in the literature, suggesting these are independent constructs. A meta-analysis found PTG may be positively correlated with PTSD symptoms, but this relationship is modified by age, trauma type, and time since trauma (Liu, Wang, Li, Gong, & Liu, Citation2017). It is notable to see increasing PTG from psychological interventions for PTSD in older adults, and that PTG can predict better treatment outcomes. Such effects have been found previously (Nijdam et al., Citation2018), indicating PTG’s potential clinical utility. Findings that depression was negatively associated with PTG in two later life studies may relate to previous theories that depressive symptoms inhibit PTG processes (Linley & Joseph, Citation2004). However, clear conclusions cannot be drawn from the small evidence reviewed here.

Within additional factors, severity of trauma across both later life and historical studies, supports previous findings (Helgeson et al., Citation2006; Kira et al., Citation2013). Finally, PTG may have implications for physical wellbeing. HRV, a metric of autonomic nervous system engagement, has been viewed as a possible mechanism linking physical and psychological health and social connection (Porges, Citation2011; Mead et al, Citation2019). Viewing HRV in the context of PTG for older people may have implications for wellbeing and health, and wider societal and environmental processes. Evidence suggests links between PTG and reductions in physiological arousal (Katz, Flasher, Cacciapaglia, & Nelson, Citation2001); given the impact of stress and trauma on health, and later life health changes (Cook et al., Citation2017; Durai et al., Citation2011), this may be particularly interesting for future research.

Do factors differ between later life and historical traumas?

Historical and later life studies demonstrated some difference in factors: equivalence of growth across trauma types, and aspects of social and psychological processes identified. Higher PTG scores were found in later life studies, however not consistently. Similarities included positive associations between severity of trauma and PTG, and significance of the AL domain. However, this review does not present clear differences in factors between historical and later life traumas. This may relate to variations in factors, as well as contexts studied.

Separating historical and later life studies may also be problematic. Later life studies frequently lacked specific detail reporting times since trauma, making it difficult to determine whether PTG measured relates to trauma occurring during later life or significantly before, or when growth occurred. For historical traumas studies, limited longitudinal data means identifying if PTG processes occurred closer to a trauma, later in life, or as an ongoing process is challenging. A lack of long-term follow-up studies is a gap given potential long-term interactions between traumatic experiences, growth components, and psychosocial factors, including community membership and support. However, such studies may not have been identified in this review’s search. Previous research suggests that course and severity of PTSD symptoms in older adults depends on when traumas occurred (early versus late life), and that for early-life traumatization, a decline in PTSD severity can be observed over the lifespan (Böttche, Kuwert, & Knaevelsrud, Citation2012). For PTG, this relationship requires further research, as relationships between time since trauma and PTG are often inconsistent and complex (Prati et al., Citation2009; Tsai, Sippel, Mota, Southwick, & Pietrzak, Citation2016)

Finally, there was limited consideration of later life psychology and PTG. Older people may experience positive psychological growth, through the challenging of one’s beliefs, throughout later life as part of normal aging. As life outlooks and understandings naturally change, a more transcendent view of life and increased life satisfaction, ‘gerotransendence,’ is possible (Tornstam, Citation2011). PTG, whilst involving growth from traumatic experiences rather than normal aging, may theoretically accelerate gerotransendence (Weiss, Citation2014). Later life presents a duality of normative losses yet high wellbeing (e.g. Office for National Statistics, Citation2016), and what distinguishes PTG from growth within normal psychological aging is an area rich for exploration.

Review limitations

Challenges of studying older people and PTG should be noted when interpreting these findings. Requiring studies to contain adults aged ≥ 60 years may be strict, as social and cultural norms define ‘becoming’ an older adult. Whilst intending to add precision, studies providing useful findings may have been excluded. This review excluded qualitative studies that provide important insights for less studied populations. Precisely defining PTG and limiting to papers published after 1995 means that other and previous studies examining equivalent concepts may have been missed, restricting what we can learn about PTG in older adults from the literature. More thought on disentangling what these terms mean, and how they have been used, within an older adult context is needed. The use of a framework approach with a priori categories means that this review presents a mostly deductive grouping of factors. Finally, studies that adopted a liberal use of the term ‘trauma’ may have been included when their inclusion is subject to debate. In intending to remain exploratory and true to the concept of PTG’s emphasis on subjectivity, this review may have forgone accuracy in diagnostic definitions of trauma and potential clinical applications.

Future research

Future studies should be more specific about the timing of traumatic events, as well as longitudinal studies examining PTG into older adulthood and those looking exclusively at traumas occurring within later life. More precise studies targeting a number of contextual factors, to further disentangle variables such as trauma severity and type are desirable. Further research examining implications of PTG for wellbeing and the role of social support may help better understand PTG within the specific context of later life. The relationship between older adults demonstrating resilience yet experiencing PTG requires further examination, through research examining more diverse challenging and traumatic experiences and considering other forms of later life growth. One additional area for future work is on methods to foster PTG in older adults, especially among recently traumatized individuals.

Clinical implications

PTG in older adults is an area lacking clear evidence, however these studies tell us something about how PTG is experienced from the vantage point of later life, across a range of settings and contexts.

Findings suggest clinicians be sensitive to the types of experiences older people may find traumatic and experience growth from, taking specific factors into account, including the impact of later-life stresses, as well as early life trauma and their historical contexts.

It may be that equivalent levels of PTG can be identified from different traumas across the lifespan when examined from the perspective of later life, but this may be different for certain early life traumas.

There is some evidence on the role of PTG enhancing outcomes for PTSD treatment. Interventions looking to support PTG in older people might want to focus on the utilization of social support and social contextual interventions. Consideration may also be taken into the potential impacts of trauma severity, age, depressive symptoms, the benefits of spirituality, and potential normative growth.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (85.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aflakseir, A., Soltani, S., & Mollazadeh, J. (2018). Posttraumatic growth, meaningfulness, and social support in women with breast cancer. International Journal of Cancer Management, 11(10), e11469.

- Baltes, P., & Baltes, M. (1990). Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. Successful Aging: Perspectives from the Behavioral Sciences, 1(1), 1–34.

- Blaszczynski, P., & Turek, R. (2013). Better life after trauma: Stomic society as an environment for posttraumatic growth for stomic patients [Lepsze zycie po traumie: Stowarzyszenie stomijne jako srodowisko rozwoju potraumatycznego pacjentow ze stomia jelitowa.]. Psychiatria I Psychologia Kliniczna, 13(3), 164–173.

- Boehm-Tabib, E., & Gelkopf, M. (2021). Posttraumatic growth: A deceptive illusion or a coping pattern that facilitates functioning? Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 13(2), 193. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000960

- Böttche, M., Kuwert, P., & Knaevelsrud, C. (2012). Posttraumatic stress disorder in older adults: An overview of characteristics and treatment approaches. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(3), 230–239. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2725

- Böttche, M., Kuwert, P., Pietrzak, R. H., & Knaevelsrud, C. (2016). Predictors of outcome of an Internet-based cognitive-behavioural therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in older adults. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 89(1), 82–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12069.

- Brix, S. A., Bidstrup, P. E., Christensen, J., Rottmann, N., Olsen, A., Tjonneland, A., Johansen, Christoffer,andDalton, S. O. (2013). Post-traumaticgrowth among elderly women with breast cancer compared to breast cancer-free women. Acta Oncologica, 52(2), 345–354. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2012.744878.

- Brunton, G., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (2020). Innovations in framework synthesis as a systematic review method. Research Synthesis Methods, 11(3), 316–330. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1399

- Byers, A. L., Covinsky, K. E., Neylan, T. C., & Yaffe, K. (2014). Chronicity of posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of disability in older persons. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(5), 540–546. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.5

- Campbell, M., Katikireddi, S. V., Sowden, A., McKenzie, J. E., & Thomson, H. (2018). Improving Conduct and Reporting of Narrative Synthesis of Quantitative Data (ICONS-Quant): Protocol for a mixed methods study to develop a reporting guideline. BMJ Open, 8(2), e020064. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020064

- Cook, J. M., McCarthy, E., & Thorp, S. R. (2017). Older adults with PTSD: Brief state of research and evidence-based psychotherapy case illustration. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(5), 522–530. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2016.12.016

- Dekel, S., Ein-Dor, T., & Solomon, Z. (2012). Posttraumatic growth and posttraumatic distress: A longitudinal study. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(1), 94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021865

- Dong, X., Li, G., Liu, C., Kong, L., Fang, Y., Kang, X., & Li, P. (2017). The mediating role of resilience in the relationship between social support and posttraumatic growth among colorectal cancer survivors with permanent intestinal ostomies: A structural equation model analysis. European Journal Of Oncology Nursing: The Official Journal Of European Oncology Nursing Society, 29, 47–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2017.04.007

- Durai, U. N. B., Chopra, M. P., Coakley, E., Llorente, M. D., Kirchner, J. E., Cook, J. M., & Levkoff, S. E. (2011). Exposure to trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in older veterans attending primary care: Comorbid conditions and self-rated health status. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59(6), 1087–1092. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03407.x

- Elderton, A., Berry, A., & Chan, C. (2017, April). A Systematic Review of Posttraumatic Growth in Survivors of Interpersonal Violence in Adulthood. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 18(2), 223–236. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015611672

- Eren-Koçak, E., & Kiliç, C. (2014). Posttraumatic growth after earthquake trauma is predicted by executive functions: A pilot study. The Journal Of Nervous And Mental Disease, 202(12), 859–863. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000211

- Forstmeier, S., Kuwert, P., Spitzer, C., Freyberger, H. J., & Maercker, A. (2009). Posttraumatic growth, social acknowledgment as survivors, and sense of coherence in former German child soldiers of World War II. The American Journal Of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal Of The American Association For Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(12), 1030–1039. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ab8b36

- Foster, D., Davies, S., & Steele, H. (2003). The evacuation of British children during World War II: A preliminary investigation into the long-term psychological effects. Aging & Mental Health, 7(5), 398–408. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1360786031000150711

- Gooding, P., Hurst, A., Johnson, J., & Tarrier, N. (2012). Psychological resilience in young and older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(3), 262–270. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2712

- Gough, D., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (2017). An introduction to systematic reviews. London: Sage.

- Greenblatt-Kimron, L. (2021). World assumptions and post-traumatic growth among older adults: The case of holocaust survivors. Stress and Health, 37(2), 353–363. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3000

- Greenblatt-Kimron, L., Marai, I., Lorber, A., & Cohen, M. (2019). The long-term effects of early-life trauma on psychological, physical and physiological health among the elderly: The study of Holocaust survivors. Aging & Mental Health, 23(10), 1340–1349. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1523880

- Hamarat, E., Thompson, D., Steele, D., Matheny, K., & Simons, C. (2002). Age differences in coping resources and satisfaction with life among middle-aged, young-old, and oldest-old adults. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 163(3), 360–367. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00221320209598689

- Heidarzadeh, M., Dadkhah, B., & Gholchin, M. (2016). Post-traumatic growth, hope, and depression in elderly cancer patients. International Journal of Medical Research & Health Sciences, 5(9), 455–461.

- Helgeson, V. S., Reynolds, K. A., & Tomich, P. L. (2006). A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(5), 797. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.797

- Higgins, J. P., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Jüni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., … Sterne, J. A. (2011). The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj, 343(oct18 2), d5928. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928

- Higgins, J. P. T., & Green, S. E. (2011). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Version 5.1.0). The Cochrane Collaboration. www.handbook.cochrane.orgwww.handbook.cochrane.org. Retrieved from www.handbook.cochrane.org

- Hoogland, A. I., Jim, H. S. L., Schoenberg, N. E., Watkins, J. F., & Rowles, G. D. (2019). Positive Psychological Change Following a Cancer Diagnosis in Old Age: A Mixed-Methods Study. Cancer Nursing. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000766

- Islam, M. M., Iqbal, U., Walther, B., Atique, S., Dubey, N. K., Nguyen, P.-A., … Shabbir, S.-A. (2016). Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia in the elderly population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology, 47(3–4), 181–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000454881

- Katz, R. C., Flasher, L., Cacciapaglia, H., & Nelson, S. (2001). The psychosocial impact of cancer and lupus: A cross validation study that extends the generality of “benefit-finding” in patients with chronic disease. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 24(6), 561–571. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012939310459

- Kinsella, E. L., Grace, J. J., Muldoon, O. T., & Fortune, D. G. (2015). Post-traumatic growth following acquired brain injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1162. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01162

- Kira, I. A., Aboumediene, S., Ashby, J. S., Odenat, L., Mohanesh, J., & Alamia, H. (2013). The dynamics of posttraumatic growth across different trauma types in a Palestinian sample. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 18(2), 120–139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2012.679129

- Knaevelsrud, C., Böttche, M., Pietrzak, R. H., Freyberger, H. J., Renneberg, B., & Kuwert, P. (2014). Integrative testimonial therapy: An Internet-based, therapist-assisted therapy for German elderly survivors of the World War II with posttraumatic stress symptoms. The Journal Of Nervous And Mental Disease, 202(9), 651–658. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000178

- Koutrouli, N., Anagnostopoulos, F., & Potamianos, G. (2012). Posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth in breast cancer patients: A systematic review. Women & Health, 52(5), 503–516. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2012.679337

- Krause, N. (2004). Lifetime trauma, emotional support, and life satisfaction among older adults. The Gerontologist, 44(5), 615–623. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/44.5.615

- Kuwert, P., Glaesmer, H., Eichhorn, S., Grundke, E., Pietrzak, R. H., Freyberger, H. J., & Klauer, T. (2014). Long-term effects of conflict-related sexual violence compared with non-sexual war trauma in female World War II survivors: A matched pairs study. Archives Of Sexual Behavior, 43(6), 1059–1064. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0272-8

- Lang, F. R. (2001). Regulation of social relationships in later adulthood. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56(6), 321–326. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/56.6.P321

- Lapp, L. K., Agbokou, C., & Ferreri, F. (2011). PTSD in the elderly: The interaction between trauma and aging. International Psychogeriatrics, 23(6), 858–868.

- Lev-Wiesel, R., & Amir, M. (2003). Posttraumatic growth among Holocaust child survivors. Journal of Loss &trauma, 8(4), 229–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020305884

- Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2004). Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 17(1), 11–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e

- Liu, A.-N., Wang, L.-L., Li, H.-P., Gong, J., & Liu, X.-H. (2017). Correlation between posttraumatic growth and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms based on Pearson correlation coefficient: A meta-analysis. The Journal Of Nervous And Mental Disease, 205(5), 380–389. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000605

- López, J., Camilli, C., & Noriega, C. (2015). Posttraumatic Growth in Widowed and Non-widowed Older Adults: Religiosity and Sense of Coherence. Journal Of Religion And Health, 54(5), 1612–1628. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9876-5

- Luong, G., Charles, S. T., & Fingerman, K. L. (2011). Better with age: Social relationships across adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 28(1), 9–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407510391362

- Lurie-Beck, J. K., Liossis, P., & Gow, K. M. (2008). Relationships between psychopathological and demographic variables and posttraumatic growth among Holocaust survivors. Traumatology, 14(3), 2016-09-15, 28–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765608320338

- MacLeod, S., Musich, S., Hawkins, K., Alsgaard, K., & Wicker, E. R. (2016). The impact of resilience among older adults. Geriatric Nursing, 37(4), 266–272. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.02.014

- Maercker, A., Forstmeier, S., Enzler, A., Krüsi, G., Hörler, E., Maier, C., & Ehlert, U. (2008). Adjustment disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depressive disorders in old age: Findings from a community survey. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49(2), 113–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.07.002

- Manne, S., Ostroff, J., Winkel, G., Goldstein, L., Fox, K., & Grana, G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth after breast cancer: Patient, partner, and couple perspectives. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66(3), 442–454. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000127689.38525.7d

- Mead, J., Fisher, Z., and Wilkie, L. (2019). Rethinking wellbeing: Toward a more ethical science of wellbeing that considers current and future generations. Authorea. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.22541/au.156649190.08734276

- Meyerson, D. A., Grant, K. E., Carter, J. S., & Kilmer, R. P. (2011). Posttraumatic growth among children and adolescents: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 949–964. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.06.003

- Michael, C., & Cooper, M. (2013). Post-traumatic growth following bereavement: A systematic review of the literature. Counselling Psychology Review, 28(4), 18–33.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Mostarac, I., & Brajković, L. (2021). Life After Facing Cancer: Posttraumatic Growth, Meaning in Life and Life Satisfaction. Journal Of Clinical Psychology In Medical Settings, 28(1), 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-020-09752-2

- Netuveli, G., Wiggins, R. D., Montgomery, S. M., Hildon, Z., & Blane, D. (2008). Mental health and resilience at older ages: Bouncing back after adversity in the British Household Panel Survey. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 62(11), 987–991. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2007.069138

- Nijdam, M. J., van der Meer, C. A., van Zuiden, M., Dashtgard, P., Medema, D., Qing, Y., … Olff, M. (2018). Turning wounds into wisdom: Posttraumatic growth over the course of two types of trauma-focused psychotherapy in patients with PTSD. Journal Of Affective Disorders, 227, 424–431. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.031

- Nowlan, J. S., Wuthrich, V. M., and Rapee, R. M., & . (2015). Positive reappraisal in older adults: A systematic literature review. Aging & Mental Health, 19(6), 475–484.

- Nuccio, A. G., & Stripling, A. M. (2021). Resilience and post-traumatic growth following late life polyvictimization: A scoping review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 57, 101481.

- Office for National Statistics. (2016). Measuring national well-being: at what age is personal well-being the highest? Retrieved from: https://www.ons.gov.Uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/measuringnationalwellbeing/atwhatageispersonalwellbeingthehighest

- Oksuzler, B., & Dirik, E. (2019). Investigation of post-traumatic growth and related factors in elderly adults’ experience of spousal bereavement. Turkish Journal of Geriatrics-Turk Geriatri Dergisi, 22(2), 181–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.31086/tjgeri.2019.91

- Oliver, S. R., Rees, R. W., Clarke-Jones, L., Milne, R., Oakley, A. R., Gabbay, J., … Gyte, G. (2008). A multidimensional conceptual framework for analysing public involvement in health services research. Health Expectations, 11(1), 72–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00476.x

- Pietrzak, R. H., Goldstein, R. B., Southwick, S. M., & Grant, B. F. (2011). Prevalence and Axis I comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: Results from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal Of Anxiety Disorders, 25(3), 456–465. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.11.010

- Pless Kaiser, A., Cook, J. M., Glick, D. M., & Moye, J. (2019). Posttraumatic stress disorder in older adults: A conceptual review. Clinical Gerontologist, 42(4), 359–376. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2018.1539801

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., … Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme Version, 1, b92.

- Pope, C., Mays, N., & Popay, J. (2007). Synthesising qualitative and quantitative health evidence: A guide to methods: A guide to methods. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

- Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology).New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Prati, G., & Pietrantoni, L. (2009). Optimism, social support, and coping strategies as factors contributing to posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 14(5), 364–388. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020902724271

- Raposo, S. M., Mackenzie, C. S., Henriksen, C. A., & Afifi, T. O. (2014). Time does not heal all wounds: Older adults who experienced childhood adversities have higher odds of mood, anxiety, and personality disorders. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(11), 1241–1250. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2013.04.009

- Reynolds, K., Pietrzak, R. H., Mackenzie, C. S., Chou, K. L., & Sareen, J. (2016). Post-traumatic stress disorder across the adult lifespan: Findings from a nationally representative survey. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(1), 81–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2015.11.001

- Rintamaki, L. S., Weaver, F. M., Elbaum, P. L., Klama, E. N., & Miskevics, S. A. (2009). Persistence of Traumatic Memories in World War II Prisoners of War. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57(12), 2257–2262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02608.x

- Rutter, M. (1985). Resilience in the face of adversity: Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. The British journal of psychiatry, 147(6), 598–611.

- Sattler, D. N., Boyd, B., & Kirsch, J. (2014). Trauma-exposed firefighters: Relationships among posttraumatic growth, posttraumatic stress, resource availability, coping and critical incident stress debriefing experience. Stress and Health, 30(5), 356–365. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2608

- Schubert, C. F., Schmidt, U., & Rosner, R. (2016). Posttraumatic growth in populations with posttraumatic stress disorder—A systematic review on growth-related psychological constructs and biological variables. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 23(6), 469–486. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1985

- Schuitevoerder, S., Rosen, J. W., Twamley, E. W., Ayers, C. R., Sones, H., Lohr, J. B., … Thorp, S. R. (2013). A meta-analysis of cognitive functioning in older adults with PTSD. Journal Of Anxiety Disorders, 27(6), 550–558. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.01.001

- Senol-Durak, E., & Durak, M. (2018). Posttraumatic growth among Turkish older adults with diabetes. Journal of Aging and Long-Term Care, 1(2), 55–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.5505/jaltc.2018.36844

- Shaw, A., Joseph, S., & Linley, P. A. (2005). Religion, spirituality, and posttraumatic growth: A systematic review. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 8(1), 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1367467032000157981

- Shenkin, S. D., Harrison, J. K., Wilkinson, T., Dodds, R. M., & Ioannidis, J. P. (2017). Systematic reviews: Guidance relevant for studies of older people. Age and Ageing, 46(5), 722–728. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx105

- Shrira, A., Shmotkin, D., & Litwin, H. (2012). Potentially traumatic events at different points in the life span and mental health: Findings from SHARE-Israel. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(2), 251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01149.x

- Sim, B. Y., Lee, Y. W., Kim, H., & Kim, S. H. (2015). Post-traumatic growth in stomach cancer survivors: Prevalence, correlates and relationship with health-related quality of life. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 19(3), 230–236. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2014.10.017

- Stein, J. Y., Bachem, R., Lahav, Y., & Solomon, Z. (2020). The aging of heroes: Posttraumatic stress, resilience and growth among aging decorated veterans. The Journal of Positive Psychology. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1725606

- Taylor, M. G., & Carr, D. (2021). Psychological resilience and health among older adults: A comparison of personal resources. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(6), 1241–1250. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa116

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Blevins, C. L. (2017). Posttraumatic growth: A pathway to resilience. In U. Kumar (Ed.), The Routledge international handbook of psychosocial resilience (pp. 324–333). New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal Of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490090305

- Tedeschi, R. G., Shakespeare-Finch, J., Taku, K., & Calhoun, L. G. (2018). Posttraumatic growth: Theory, research, and applications. New York: Routledge.

- Tornstam, L. (2011). Maturing into gerotranscendence. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 43(2), 166–180.

- Tsai, J., Sippel, L. M., Mota, N., Southwick, S. M., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2016). Longitudinal course of posttraumatic growth among US military veterans: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Depression and Anxiety, 33(1), 9–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22371

- Weathers, F. W., & Keane, T. M. (2007). The Criterion A problem revisited: Controversies and challenges in defining and measuring psychological trauma. Journal Of Traumatic Stress, 20(2), 107–121. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20210

- Weiss, T. (2014). Personal transformation: Posttraumatic growth and gerotranscendence. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 54(2), 203–226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167813492388

- Williamson, V., Stevelink, S. A., Greenberg, K., & Greenberg, N. (2018). Prevalence of mental health disorders in elderly US military veterans: A meta-analysis and systematic review. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(5), 534–545. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2017.11.001

- World Health Organisation. (2018). Ageing and Health. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health.

- Wu, X., Kaminga, A. C., Dai, W., Deng, J., Wang, Z., Pan, X., & Liu, A. (2019). The prevalence of moderate-to-high posttraumatic growth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal Of Affective Disorders, 243, 408–415. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.023

- Zoellner, T., & Maercker, A. (2006). Posttraumatic growth in clinical psychology—A critical review and introduction of a two component model. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(5), 626–653. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.008