ABSTRACT

Objectives

Research reports that providing care to a relative or friend with a chronic health condition or significant neurocognitive disorders, such as dementia is a demanding job. Caregiving often leads to higher risk for adverse mental health outcomes. In this study, we examine the short-term efficacy of the CaregiverTLC online psychoeducational program to caregivers of adults with chronic health or significant memory troubles.

Method

Using pre-post data from the CaregiverTLC randomized controlled trial (n = 81) we examined differences between the intervention and control conditions on caregivers’ psychosocial outcomes for depressive symptoms, self-efficacy, burden, anxiety, and caregiver gains.

Results

Data analyses indicated significant decrease in self-reported depressive symptoms, burden, anxiety, and significant increases in self-efficacy and caregiver gains for caregivers in the active intervention compared to those in the control condition.

Conclusions

These results suggest that regardless of whether caregivers care for a person with a chronic illness or significant neurocognitive disorder, they can benefit from participation in this online psychoeducational program.

Clinical Implications

The CaregiverTLC program may be an effective method to teach skills to reduce depression, burden, and anxiety, and improve self-efficacy and personal gains among caregivers of older adults with chronic illnesses.

Research has documented that providing care to someone with chronic medical conditions or a significant neurocognitive disorder is a demanding job. Numerous studies report deleterious effects on caregivers’ mental and physical health. While some of these issues may have existed before caregiving began, there are sufficient data to conclude that caregiving itself often leads to higher risk for adverse mental and physical health outcomes (Schulz et al., Citation2020). To address caregiver mental health issues, a variety of intervention programs have been developed and tested. Several have been designated as “evidence-based” or “evidence-derived” based on cumulative data from randomized controlled trials that reported small-to-moderate positive effects on the emotional and psychological wellbeing of caregivers receiving the intervention (Belle et al., Citation2006; Cheng et al., Citation2020; Walter et al., Citation2020). According to these reviews, psychoeducational skill-building programs are one type of intervention generally having positive results. These programs are conceptually rooted in stress and coping models (Pearlin et al., Citation1990) and use cognitive-behavioral principles and practices to reinforce learning (Gallagher-Thompson et al., Citation2012). A recent meta-analysis supports these findings and provides further evidence that specific caregiving interventions have positive effects on knowledge, subjective well-being, burden, depression, and anxiety. The type and magnitude of effects varying, according to the specific program (Walter et al., Citation2020). Similarly, Sun et al. (Citation2022) reviewed 85 studies of non-pharmacological interventions and found that multicomponent and psychoeducational interventions, as well as some forms of psychotherapy, significantly reduced depression in caregivers of persons living with dementia (PLWD). Research on the efficacy of such programs with caregivers of persons with chronic medical conditions has recently been reviewed by Rouch et al. (Citation2021). Their work is consistent with the observation that psychoeducational programs with a skill-building focus are effective with these populations as well.

One such psychoeducational program, Coping with Caregiving (CWC) was designed for family caregiver of PLWD (Gallagher-Thompson et al., Citation2003; Gallagher‐Thompson et al., Citation2000). The CWC consists of 4–12 weekly in-person meetings of 90–120 minute’s duration with a closed cohort of 6–12 family caregivers. Each includes a mini-lecture and experiential components (to foster participant interaction) along with home practice assignments. Caregivers enrolled in the CWC program have reported a significant reduction in depressive symptoms, better use of adaptive coping strategies, and a trend toward decreased use of negative coping strategies when compared to a support group condition (Gallagher-Thompson et al., Citation2003, Citation2012). These results are similar to other frequently used psychoeducational programs to treat caregiver distress, such as the Savvy Caregiver Program (K. W. Hepburn et al., Citation2007). However, since the COVID pandemic, awareness of significant limitations to implementation of these in-person programs has increased. For example, logistical issues, such as transportation and associated costs, as well as barriers to access associated with rural vs urban settings, reduce the likelihood that such programs will continue – despite their effectiveness. To overcome these difficulties investigators began using web-based virtual program delivery. As the use of technology for health care becomes more widespread, caregivers are turning to it to access supportive services and help overcome barriers. The use of on-line video teleconferencing in the caregiver’s own residence brings programming to the caregiver, reducing some of the barriers noted. For example, results from a randomized trial testing the efficacy of the Tele-Savvy caregiver program for dementia caregivers confirmed the program efficacy and the viability of using technology to support caregivers’ wellbeing and sense of mastery (K. Hepburn et al., Citation2022).

The Caregiver: Thrive, Learn & Connect program (CaregiverTLC), was derived from CWC through a developmental process of several months’ duration. Goals of CaregiverTLC were to reduce burden, anxiety, and depressive symptoms, to increase self-efficacy and perceived gains from caregiving, and to be a viable program that could be offered remotely, rather than an in-person small group format. To reach these goals, core components of CWC were maintained and other evidence-based and evidence-informed components were added. Delivery stayed in a small group format presented in real time by the facilitators, but it moved from in-person to a virtual group delivered via a teleconference program. Contents remain similar for both formats with topics presented in lecture form followed by interactive exercises; however, examples were changed to be more inclusive for caregivers of persons with chronic illness in addition to PLWD. An optional-to-use website was developed to offer additional resources to the caregiver for each session topic. The website contents include supplemental educational material on each topic covered, as well as listings of curated resources (local and national). Pilot testing was done to assess flow of material and caregiver acceptability of this on-line technology-based intervention and appropriate modifications made, based on feedback obtained.

Core CWC components of stress management (behavioral activation for depressive symptoms and importance of caregiver self-care) were used to develop Sessions 1, 2, and 4 (see for Session description). In addition, the following evidence-based and evidence-informed materials were added. Session 3”s topics of addressing caregivers” negative worldviews was theoretically derived from positive psychology and Seligman’s “Three Good Things” exercise (Seligman et al., Citation2005). The second half of Session 3 uses the Atlas CareMap as a method to visualize a caregiver’s support network (Mehta & Nafus, Citation2016). Session 5’s topic of anger management uses an earlier program developed by Gallagher-Thompson and DeVries (Citation1994). Session 6‘s topic discusses social isolation and how caregiving can lead to loneliness. Drawing on current information available on the internet, caregivers are introduced to a variety of specific methods of finding support online.

Table 1. Week-by-week description of CaregiverTLC.

This paper reports on the efficacy of the randomized trial of the CaregiverTLC program. The two primary outcomes were the program’s effect on depressive symptoms and self-efficacy. Secondary outcomes tested the effect of the program on caregiver burden, anxiety, and perceived gains. Our main hypotheses were: (1) caregivers in the experimental condition will report significantly lower scores on depressive symptom measures compared to those in waitlist control condition, and (2) will report significantly higher self-efficacy that those in waitlist control conditions.

Methods

This study used a prospective, randomized controlled trial design comparing intervention group vs. waitlist group participation, to examine the efficacy of the CaregiverTLC, an online psychoeducational program. Each workshop is comprised of 6–8 caregivers who attend 90 min on-line Zoom meetings, led by a facilitator trained by research staff. Each session begins with a check-in to review home practice, followed by description of the meeting’s agenda and content. Then interactive activities are used to introduce and to practice the specific skills focused on in that session. Following this, a summary of important facts and skills, and creation of an action plan for home practice, are completed (see for description of the sessions). Ongoing access to resources available on the website was encouraged every session. In the final session, each caregiver creates a master action plan so they can identify which skills they are most likely to use to meet future caregiving challenges.

To evaluate whether the program was delivered as intended by trained facilitators, we implemented a multi-pronged fidelity plan. First, interventionists were given the program manual and a set of PowerPoint slides to use at each session. Facilitators received 12 h of training that covered the content itself as well as skills for presenting this program in a teleconferencing format. Then, facilitators were observed conducting every session of their first workshop, and their performance was evaluated using a checklist of key components for each session that was designed for this research. All facilitators attended regular Zoom meetings to review and discuss performance and to problem-solve issues that arose. Next, random sessions from each facilitator were selected, observed, and scored and all were required to attend regular Zoom-based consultation meetings (led by project training staff) to monitor continued protocol adherence.

Sample and recruitment

The CaregiverTLC study was approved by the IRB of the University of North Carolina, Charlotte. Caregivers were eligible who met the following criteria: (a) 18 years of age or greater, (b) caring for an adult relative or friend with at least one chronic medical illness or significant memory problems requiring assistance for day-to-day function, (c) provide at least 4 h of care weekly (broadly defined ranging from hands-on care to assistance with tasks, such as medication management and paying bills), (d) reliable access to the internet, a valid e-mail address, and means and ability to participate in the synchronous and asynchronous program components, and (e) ability to read and understand written and spoken English. Caregivers were recruited from public service announcements, newsletter descriptions, information posted in church bulletins, and through several community-based organizations working with older adults. A community advisory board was assembled to assist with dissemination and recruitment of caregivers.

In total, 107 caregivers who contacted the program’s website for information were assigned to groups of 6–8 members, based on availability to attend the day and time of the weekly workshops. Groups were randomly assigned to the experimental or waitlist control conditions. Sixty caregivers were assigned to CaregiverTLC and 47 to waitlist control (see ). Following randomization six withdrew before the program started, 16 withdrew prior to completing the Time 2 (T2) assessment, and of those completing the T2 assessment, three attended fewer than four workshop sessions. All such cases were excluded from the present analyses.

Data collection

Caregivers who indicated interest on the program website were contacted by research staff by phone and received the option to complete surveys on-line or by phone. Caregivers who chose the former were emailed a link to the respective survey; those who chose the latter were called by trained research assistants who entered their responses into the web-based survey fields. Caregivers attended workshops during fall 2021 through spring 2023. Participants received $10 electronic gift cards for each survey to compensate for their time. Data were collected at baseline (T1) and post intervention (T2), which was typically after 8 weeks when the intervention or time on the waitlist were completed. Caregivers on the waitlist were offered the opportunity to attend the CaregiverTLC workshop.

Outcome measures

Caregiver Depression was measured as the frequency and type of depressive symptoms using the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Spitzer et al., Citation1999), on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (Not at All) to 3 (Nearly Every Day). Higher scores reflect higher depression (α = .80).

Caregiver Self-efficacy was assessed with the Revised Scale for Caregiving Self-Efficacy (CSES-8; Ritter et al., Citation2022). This is an 8-item Likert-type questionnaire where caregivers rate their confidence to do a caregiving task on a 1–10 scale (e.g., asking a friend/relative to stay with care partner). Higher scores reflect higher self-efficacy (α = .82).

Caregiver Burden was measured with the 12-item Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-12), developed by Bédard et al. (Citation2001). All questions are answered as “never” (0), “rarely” (1), “sometimes” (2), “quite frequently” (3), or “nearly always” (4). Higher scores indicate higher burden (α = .83).

Caregiver Anxiety was assessed with the 7-item GAD-7 scale (Spitzer et al., Citation2006). Caregivers indicated over the last 2 weeks ‘How often have been bothered by the problems (afraid, nervous, etc.). Using a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 3 (Nearly every day). Higher scores indicate higher caregiver anxiety (α = .88).

Caregiver Gains were measured with 10-items scale of GAINS developed by Yap et al. (Citation2010). Items assess the experience of gains in caregivers covering areas of personal growth and social and emotional support from others. Caregivers used a 7-point scale (1 Strongly Disagree − 7 Strongly Agree) to indicate how caring for a relative improved their personal development. Higher scores indicate higher caregiver gains (α = .91).

Two-way repeated measures ANOVAs were used to assess differences in the treatment groups across time (SPSS v.29). We tested for differences in participant characteristics and levels of the outcome variables at baseline between the two conditions, as well as testing for differences between caregivers completing T2 assessments and those who dropped out of the study prior to completing T2.

Results

displays caregivers’ demographic information. Caregivers are primarily female and on average 65 years old. About two-thirds were White (61.7%), more than one-third were Black (37%), and one caregiver self-reported as Asian American (1.2%). All reported providing care to individuals of the same racial and ethnic background as their own. The majority of caregivers were college graduates (82%) and were retired or not working by choice (46%). More than half (60%) reported household income was $75,000 and greater before taxes. Most were dementia caregivers (69%) with the remainder (31%) caring for persons with other chronic conditions. Most reported caring for a parent (58%) followed by a spouse (34%) and provide more than 20 h of care per week to the care-recipient (56%).

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of caregivers by condition group.

One-way ANOVA or Chi-square analytic methods found no significant differences at baseline (T1) between caregivers in the two conditions (see ). Caregivers randomly assigned to the intervention group, who either withdrew from the study prior to completing the T2 assessment or did not complete a minimum of 4 modules (n = 23), did not significantly differ from those completing at least 4 modules and the T2 assessment (n = 37) on any demographic factors or baseline levels of depression, self-efficacy, burden, anxiety, or gains. Additionally, Black caregivers (n = 30) did not significantly differ from White caregivers (n = 50) on baseline levels of depression (F1, 78 = .92, p = .34), self-efficacy (F1, 77 = .03, p = .86), burden (F1, 78 = 1.84, p = .18) or anxiety (F1, 78 = .69, p = .41), although White caregivers reported significantly higher gains at baseline (F1, 78 = 9.51, p =.003). Likewise, caregivers caring for individuals with dementia (n = 56) did not significantly differ from those providing care to persons with chronic illness (n = 25) on baseline levels of depression (F1, 79 = .03, p = .87), self-efficacy (F1, 78 = 3.92, p = .05), burden (F1, 79 = 1.85, p = .18), anxiety (F1, 79 = 2.00, p = .16), or gains (F1, 79 =.78, p = .39).

CaregiverTLC efficacy results

Prior to conducting efficacy analyses, one-way ANOVAs were conducted to determine whether caregivers in the intervention condition differed significantly from the control condition on baseline levels of depression, self-efficacy, burden, anxiety, and gains. Results revealed that caregivers in both groups did not significantly differ in their levels of depression (F1, 79 = .66, p = .42), self-efficacy (F1, 78 = 1.23, p = .27), anxiety (F1, 79 = 1.48, p = .23), or gains (F1, 79 = 1.47, p = .23).

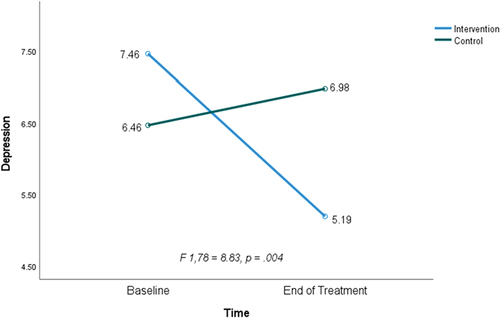

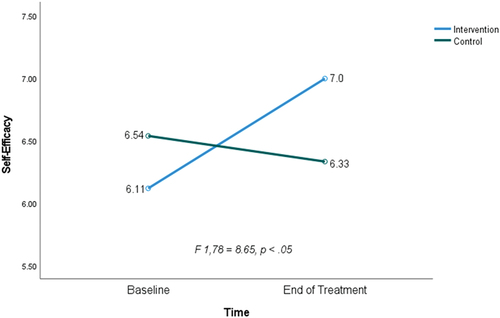

display results from the two-way repeated measures ANOVAs for primary and secondary outcome measures.

Depression: we found a significant group × time interaction for depression (F 1, 79 = 8.83, p = .004), with caregivers in the intervention group reporting lower levels of depression at Time 2. The intervention has a medium effect size (d = .52, ηp2 = .10) for improvement in depression (power = .83). PHQ-9 scores at Time 1 ranged from 0 to 18 (M = 6.99, SD = 4.78). Scores at Time 2 ranged from 0 to 22 (M = 6.15, SD = 4.72).

Self-efficacy: there was a significant group × time interaction (F1, 79 = 8.65, p =.004) with the intervention group experiencing an increase in self-efficacy levels at Time 2. The intervention has a medium effect size (d = .51, ηp2 = .10) on self-efficacy (power =.83). CSES-8 mean scores at Time 1 ranged from 2.13 to 10 (M = 6.34, SD = 1.69). Scores at Time 2 ranged from 1.25 to 10 (M = 6.64, SD = 1.80).

Burden: there was a significant group × time interaction for burden (F1,79 = 7.82, p = .006), with caregivers in the intervention group reporting lower levels of burden at Time 2. The intervention has a small-to-medium effect size (d = .30, ηp2 = .09) on burden (power = .79). ZB-6 scores at Time 1 ranged from 0 to 21 (M = 12.72, SD = 4.82). Scores at Time 2 ranged from 1 to 22 (M = 12.14, SD = 4.60).

Anxiety: there was a significant group × time interaction for anxiety (F1,79 = 4.72, p = .03), with caregivers in the intervention group reporting lower levels of anxiety at Time 2. The intervention has a small-to-medium effect size (d = .29, ηp2 = .06) on anxiety (power = .57). GAD-7 scores at Time 1 ranged from 0 to 20 (M = 8.18, SD = 5.08), and scores at Time 2 ranged from 0 to 21 (M = 6.76, SD = 5.08).

Gains: there was a significant group × time interaction (F1,79 = 4.43, p = .04) with those in the intervention group experiencing an increase in gains at Time 2. The intervention has a small-to-medium effect size (d = .27, ηp2 = .05) on caregiver gains (power = .55). Gains scores at Time 1 ranged from 0 to 40 (M = 27.36, SD = 9.09) and scores at Time 2 ranged from 2 to 40 (M = 27.41, SD = 9.11).

Table 3. Repeated measures time by group for caregivers’ dependent outcomes.

show estimated marginal means for T1 and T2 for experimental and control groups, displaying the effect of the CaregiverTLC on each of the two primary outcomes of interest.

Additional analyses were performed to test controlling by race (White versus Black) and type of chronic condition of the care-recipient (significant neurocognitive disorder vs. chronic medical condition), including them as covariates in each of the models. Results showed that the group × time interaction remained significant for all outcomes, suggesting that the CaregiverTLC program has similar positive effects on Black as well as White caregivers, and on caregivers of persons with chronic medical conditions as well as those caring for a PLWD or other significant forms of cognitive impairment.

We also computed mean change on depression scores from baseline to end of treatment for the intervention group to determine the average change in depression scores over time. Participants were classified as reporting none/minimal (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), moderately severe (15–19), or severe (20 to 27) depression using PHQ-9 scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 as the cut points, respectively (Kroenke & Spitzer, Citation2002). At baseline, 13 (35.1%) reported none/minimal, 12 (32.4%) reported mild, 8 (21.6%) reported moderate, and 4 (10.8%) reported moderately severe depression. At end of treatment, 24 (64.9%) reported none to minimal, 6 (16.2%) reported mild, 5 (13.5%) reported moderate, and 2 (5.4%) reported moderately severe depression. Paired-samples t-test analyses were conducted to compute mean change scores for participants with improved depression scores from baseline to end of treatment, unchanged depression scores, and increased depression scores. Results revealed depression scores improved (Mdiff = −6.93, SDdiff = 4.46) for 14 (37.84%) intervention participants, remained unchanged (Mdiff = .05, SDdiff = 1.06) for 19 (51.35%) and worsened (Mdiff = 3.00, SDdiff = 2.16) for 4 (10.81%).

Discussion

Results of this randomized controlled trial support the efficacy of the CaregiverTLC online psychoeducational program to significantly reduce depressive symptoms and improve self-efficacy among caregivers attending the program in comparison to caregivers in the waitlist control condition. Effect sizes for depressive symptoms (d =.52) and self-efficacy (d =.51) are moderate. These findings are consistent with a recent randomized trial testing the efficacy of the Tele-Savvy online psychoeducation program (K. Hepburn et al., Citation2022). Results are likewise consistent with previous findings from in-person RCTs studies testing psychoeducational interventions where significant reduction of depressive symptoms was found among dementia caregivers (Rouch et al., Citation2021; Sun et al., Citation2022). Some studies also reported significantly lower levels of burden in comparison to control conditions (Rabinowitz et al., Citation2011).

In addition to these positive findings on the primary outcome measures, analyses of secondary outcomes are also supportive of the value of CaregiverTLC to improve several dimensions of caregiver well-being. Although effect sizes are low to moderate, significant reductions in levels of burden (d = .30) and anxiety (d=,29) as well as improvement in perceived positive aspects of caregiving (d = .27), were found for those in the intervention condition compared to those in the wait list control condition. The reduction of caregiver burden by this program is notable since prior reviews reported mixed results regarding the ability of psychoeducational programs to impact caregiver burden (Schulz et al., Citation2020). However, a recent systematic review of psychoeducational interventions reports that at least some of these programs did reduce caregiver burden (Cheng et al., Citation2020). Therefore, it is of interest that the CaregiverTLC corroborated such caregiver burden reduction. This positive effect may reflect the program’s emphasis on learning and practicing a set of skills likely to improve everyday quality of life for the family caregiver and by extension the care recipient.

The low to moderate effect on caregivers’ anxiety is consistent with findings from an Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy randomized controlled pilot study with informal high-intensity, long-term caregivers in Lithuania (Biliunaite et al., Citation2021), although they found moderate-to-high between-group effect sizes on measures of anxiety in their sample. This discrepancy may reflect the fact that CaregiverTLC did not emphasize teaching skills for managing anxiety; rather it focused more on managing feelings of depression. It may be worthwhile to include anxiety reduction skills in future iterations of CaregiverTLC.

The low effect on caregiver gains is consistent with similar reports namely, although positive gains may be present, they exist alongside of many challenging aspects of caregiving which can at times be overwhelming, depending to some extent on stage of the care recipient’s illness (Gallagher-Thompson et al., Citation2020).

Finally, post-hoc analyses indicated similar patterns of change on the two key outcome measures for both White and Black caregivers. These results are consistent with findings from previous studies where derivatives of the CWC psychoeducational program were used effectively with caregivers from a variety of racial and ethnic backgrounds – including Hispanic/Latino, Chinese American, and Vietnamese American (see Gallagher-Thompson et al. (Citation2020) for review of these culturally adapted programs). These patterns of change were similar for caregivers of PLWD and those providing care for adults with chronic health conditions. We believe that the careful selection of topics and skills incorporated into CaregiverTLC (see ) was a contributing factor to the success of the program in addressing the core needs of caregivers in both groups. However, although both of these results are encouraging, these post-hoc analyses were not adequately powered to directly test between-group differences of interest. Future research should employ outreach and enrollment strategies that permit these results to be tested as formal hypotheses.

This study has several other limitations to keep in mind when interpreting results. First, the data indicate that improvement in anxiety and positive gains from caregiving (although statistically significant) were small in magnitude, suggesting that further refinement of CaregiverTLC content is needed to address these domains of caregiver well-being. Second, it was noted that a number of caregivers dropped out before completing the full program and/or the post-intervention surveys. Participants were not required to provide a rationale for dropping out of the study. Thus, data regarding reasons for discontinuing the program are not available. Drop out could be due to several factors, such as increased time and energy demands on the caregiver due to changes in their care-recipient’s health, which interfered with their ability to attend scheduled meetings (e.g., unexpected medical appointments). Other factors, such as lack of perceived relevance of specific content to their caregiving situation, may have resulted in some dropping the program. Future studies need to incorporate methods to follow up with those who discontinue to document the reasons why so this information can be used to guide development of new studies. Finally, greater incorporation of the project’s website into workshop session content, and more encouragement of its use should occur. The website was designed to provide supplemental educational material on each topic covered, as well as listings of curated resources (local and national) which could be helpful long after CaregiverTLC is completed. Focused attention on this issue is warranted in future studies.

Development, evaluation, and implementation of effective interventions to reduce caregiver distress and improve their sense of being able to manage caregiving-related stressful situations is key to maintaining health and well-being. On the national level, currently there is increased attention to the key role that caregivers play, as well as on their needs for supportive programs and interventions (RAISE Act Family Caregiving Advisory Council & The Advisory Council to Support Grandparents Raising Grandchildren, Citation2022). Given this commitment to the expansion of behavioral health to address caregivers’ mental health needs, we believe these results are timely: decreasing depressive symptoms and increasing perceived self-efficacy are important domains of caregiver well-being that are related to maintenance of good mental health (Schulz et al., Citation2020). These data add to the existing body of knowledge as to effectiveness of psychoeducational programming. The fact that CaregiverTLC was delivered entirely on-line suggests that it is an effective approach with caregivers who are unwilling or unable to attend in-person programs. In addition, it provides a service delivery option for agencies that want to offer both types of services to expand the numbers of caregivers they serve. Locally, staff in agencies that already deliver services to caregivers are being trained to deliver the program so it can be embedded within their existing offerings. A future research direction may be the evaluation of the use of the CaregiverTLC program once embedded into the community-based organization. This should increase sustainability of CaregiverTLC after completion of the research.

Finally, our findings provide initial support for effective use of this program with caregivers of both White and Black racial/ethnic backgrounds, as well as with caregivers caring for a person with chronic health conditions or neurocognitive disorders, such as dementia. Our results are also consistent with those obtained with similar in-person programs, thus increasing accessibility for many caregivers who might not otherwise be able to participate.

Clinical implications

Psychoeducational programs such as CaregiverTLC, when delivered via technology, seems to be an effective strategy to teach specific skills to reduce depression and strengthen self-efficacy in caregivers of persons with chronic illnesses, including the dementias.

Although some caregivers may be relatively inexperienced with telehealth-type service delivery at the outset, they can and do learn enough to be able to participate in this type of program and complete on-line questionnaires.

Embedding effective programs such as these into community-based agencies increases their sustainability and accessibility to caregivers who might otherwise be experiencing significant distress related to caregiving but who do not have the wherewithal to access mental health services directly. Psychoeducational programs are flexible and by working collaboratively with community-based agencies, appropriate content could be developed, evaluated, and incorporated into future programming. This feature warrants continued support by the research community.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Data are available from the first author upon request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bédard, M., Molloy, D. W., Squire, L., Dubois, S., Lever, J. A., & O’Donnell, M. (2001). The Zarit burden interview: A new short version and screening version. The Gerontologist, 41(5), 652–657. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/41.5.652

- Belle, S. H., Burgio, L., Burns, R., Coon, D., Czaja, S. J., & Gallagher-Thompson, D., … Martindale-Adams, J. (2006). Enhancing quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups: A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 145(10), 727–738. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00005

- Biliunaite, I., Kazlauskas, E., Sanderman, R., Truskauskaite-Kuneviciene, I., Dumarkaite, A., & Andersson, G. (2021). Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for informal caregivers: Randomized controlled pilot trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(4), e21466. https://doi.org/10.2196/21466

- Cheng, S.-T., Li, K.-K., Losada, A., Zhang, F., Au, A., Thompson, L. W., & Gallagher- Thompson, D. (2020). The effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions for informal dementia caregivers: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 35(1), 55–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000401

- Gallagher‐Thompson, D., Lovett, S., Rose, J., McKibbin, C., Coon, D., Futterman, A., & Thompson, L. W. (2000). Impact of psychoeducational interventions on distressed family caregivers. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology, 6(2), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009584427018

- Gallagher-Thompson, D., Bilbrey, A. C., Apesoa-Varano, E. C., Ghatak, R., Kim, K. K., Cothran, F., & Siegel, E. O. (2020). Conceptual framework to guide intervention research across the trajectory of dementia caregiving. The Gerontologist, 60(Supplement_1), S29–S40. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz157

- Gallagher-Thompson, D., Coon, D. W., Solano, N., Ambler, C., Rabinowitz, Y., & Thompson, L. W. (2003). Change in indices of distress among Latino and Anglo female caregivers of elderly relatives with dementia: Site-specific results from the REACH national collaborative study. The Gerontologist, 43(4), 580–591. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/43.4.580

- Gallagher-Thompson, D., & DeVries, H. M. (1994). “Coping with Frustration” classes: Development and preliminary outcomes with women who care for relatives with dementia. The Gerontologist, 34(4), 548–552. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/34.4.548

- Gallagher-Thompson, D., Tzuang, M., Au, A., Brodaty, H., Charlesworth, G., Gupta, R., Lee, S. E., Losada, A., & Shyu, Y.-I. (2012). International perspectives on nonpharmacological best practices for dementia family caregivers: A review. Clinical Gerontologist, 35(4), 316–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2012.678190

- Hepburn, K. W., Lewis, M., Tornatore, J., Sherman, C. W., & Dolloff, J. (2007). The savvy caregiver. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 33(3), 30–36. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20070301-06

- Hepburn, K., Nocera, J., Higgins, M., Epps, F., Brewster, G. S., Lindauer, A., Morhardt, D., Shah, R., Bonds, K., Nash, R., Griffiths, P. C., & Meeks, S. (2022). Results of a randomized trial testing the efficacy of Tele-Savvy, an online synchronous/asynchronous psychoeducation program for family caregivers of persons living with dementia. The Gerontologist, 62(4), 616–628. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab029

- Kroenke, K., & Spitzer, R. L. (2002). The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals, 32(9), 509–521. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06

- Mehta, R., & Nafus, D. (2016). Atlas of caregiving pilot study report. San Francisco: Family Caregiver Alliance.

- Pearlin, L. I., Mullan, J. T., Semple, S. J., & Skaff, M. M. (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30(5), 583–594. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/30.5.583

- Rabinowitz, Y. G., Saenz, E. C., Thompson, L. W., & Gallagher-Thompson, D. (2011). Understanding caregiver health behaviors: Depressive symptoms mediate caregiver self- efficacy and health behavior patterns. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias®, 26(4), 310–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317511410557

- Recognize, Assist, Include, Support, and Engage (RAISE) Act Family Caregiving Advisory Council & The Advisory Council to Support Grandparents Raising Grandchildren. (2022). 2022 National Strategy to Support Family Caregivers. Administration for Community Living. https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/RAISE_SGRG/NatlStrategyToSupportFamilyCaregivers.pdf

- Ritter, P. L., Sheth, K., Stewart, A. L., Gallagher-Thompson, D., Lorig, K., & Meeks, S. (2022). Development and evaluation of the eight-item Caregiver Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES-8). The Gerontologist, 62(3), e140–e149. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa174

- Rouch, S. A., Fields, B. E., Alibrahim, H. A., Rodakowski, J., & Leland, N. E. (2021). Evidence for the effectiveness of interventions for caregivers of people with chronic conditions: A systematic review. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(4). https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2021.042838

- Schulz, R., Beach, S. R., Czaja, S. J., Martire, L. M., & Monin, J. K. (2020). Family caregiving for older adults. Annual Review of Psychology, 71(1), 635. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-050754

- Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. The American Psychologist, 60(5), 410–421. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Patient Health Questionnaire Primary Care Study Group, & Patient Health Questionnaire Primary Care Study Group. (1999). Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. Jama, 282(18), 1737–1744.

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Sun, Y., Ji, M., Leng, M., Li, X., Zhang, X., & Wang, Z. (2022). Comparative efficacy of 11 non-pharmacological interventions on depression, anxiety, quality of life, and caregiver burden for informal caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 129, 104204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104204

- Walter, E., Pinquart, M., & Heyn, P. C. (2020). How effective are dementia caregiver interventions? An updated comprehensive meta-analysis. The Gerontologist, 60(8), e609–e619. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz118

- Yap, P., Luo, N., Ng, W. Y., Chionh, H. L., Lim, J., & Goh, J. (2010). Gain in Alzheimer care Instrument–a new scale to measure caregiving gains in dementia. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(1), 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181bd1dcd