ABSTRACT

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to explore the mediating roles of care receiver clinical factors on the relationship between care partner preparedness and care partner desire to seek long-term care admission for persons living with dementia at hospital discharge.

Methods

This study analyzed data from the Family centered Function-focused Care (Fam-FFC), which included 424 care receiver and care partner dyads. A multiple mediation model examined the indirect effects of care partner preparedness on the desire to seek long-term care through care receiver clinical factors (behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia [BPSD], comorbidities, delirium severity, physical function, and cognition).

Results

Delirium severity and physical function partially mediated the relationship between care partner preparedness and care partner desire to seek long-term care admission (B = -.011; 95% CI = -.019, −.003, and B = -.013; 95% CI = -.027, −.001, respectively).

Conclusions

Interventions should enhance care partner preparedness and address delirium severity and physical function in hospitalized persons with dementia to prevent unwanted nursing home placement at hospital discharge.

Clinical Implications

Integrating care partner preparedness and care receiver clinical factors (delirium severity and physical function) into discharge planning may minimize care partner desire to seek long-term care.

Introduction

Dementia is one of the primary reasons older adults are admitted to long-term care facilities (Fagundes et al., Citation2021; Tanuseputro et al., Citation2017). Although most people with dementia prefer to continue living in the community, about 46% of long-term care residents have dementia, and admission rates increase as the disease progresses (Alzheimer’s Association, Citation2024). Admission to long-term care often involves a careful decision to ensure enhanced care for the recipient, such as ensuring safety and assisting with daily activities, which can lead to improved health outcomes (Olsen et al., Citation2016). However, for individuals living with dementia, transition to long-term care can be associated with increased use of psychotropic medications, reduced levels of physical activity, diminished social contact, lower quality of life, higher healthcare costs, and increased mortality rates (Brent, Citation2022; Nikmat et al., Citation2015; Olsen et al., Citation2016).

Among community-dwelling persons living with dementia, the decision to seek long-term care can be influenced by various characteristics of both the care partner and the care receiver (Eska et al., Citation2013; Gallagher et al., Citation2011; Gaugler et al., Citation2009; Hébert et al., Citation2001; López et al., Citation2012; McCann et al., Citation2005; McCaskill et al., Citation2011; Saposnik et al., Citation2011; Vandepitte et al., Citation2018). For care partners, factors such as identifying as male, White race, advanced age, higher education level, employment status, lack of a spouse, residing with the person with dementia, depression, and burden can impact the decision to choose long-term care (Eska et al., Citation2013; Gallagher et al., Citation2011; López et al., Citation2012; McCaskill et al., Citation2011; Vandepitte et al., Citation2018). For care receivers, factors may include behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), multiple comorbidities, lower cognition, increased delirium, decreased mobility, and recurrent hospitalizations (Fong et al., Citation2012; Gaugler et al., Citation2009; McCann et al., Citation2005; Saposnik et al., Citation2011; Toot et al., Citation2017; Vo et al., Citation2023).

Compared to patients without dementia, hospitalized patients with dementia are more frequently discharged to long-term care facilities (Bu & Rutherford, Citation2018). Persons living with dementia require more intensive care during hospitalization due to factors such as increased delirium, heightened levels of BPSD, and declines in cognitive and physical function (Fogg et al., Citation2018; Hessler et al., Citation2017). Additionally, the presence of comorbidities further complicates their care needs, increasing the stress and burden on their care partners (Dauphinot et al., Citation2016; Jhang et al., Citation2024). At hospital discharge, care partners often want the person living with dementia, the care receivers, to return home at hospital discharge (Livingston et al., Citation2010; Mockford, Citation2015). However, during the post-hospital transition, care partners face more complex caregiving demands and feel unprepared to manage the heightened care needs, precipitating the admission of the care receiver to long-term care (Kuzmik et al., Citation2023). Limited research has explored the interplay of the clinical factors that connect care partner preparedness to care partner desire to seek long-term care admission. Understanding the underlying pathways of care receivers’ clinical factors is crucial for developing interventions that can support care partner preparedness and minimize unnecessary and/or undesired long-term care admissions during the critical transition period after hospital discharge.

To address this research gap, we applied an adapted version of the Andersen Behavioral Model of Health Services Use (Andersen, Citation1995), which examines the influence of predisposing factors (individual characteristics), enabling resources (factors facilitating access), and need factors (health conditions requiring services) on health service use. Specifically, the purpose of this study was to explore the mediating roles of clinical factors in the person living with dementia (i.e., BPSD, comorbidities, delirium severity, physical function, and cognition) on the relationship between care partner preparedness and care partner desire to seek long-term care admission at hospital discharge. In this model, enabling resources are represented by the care partner’s perceived preparedness, including their ability and readiness to provide care. Care receiver clinical factors including BPSD, comorbidities, delirium severity, physical function, and cognition serve as need factors. The study controlled for predisposing factors such as care partner characteristics (i.e., age, gender, race, and cohabitation status with the care receiver). We hypothesized that care receiver clinical factors would mediate the association between care partner preparedness and care partner desire to seek long-term care admission.

Methods

Study design

This study conducted a secondary analysis, utilizing data from a cluster randomized trial titled Family centered Function-focused Care (Fam-FFC), registered under ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03046121. Fam-FFC represents a model fostering collaboration between nurses and family care partners. The objectives of the Fam-FFC intervention include improving the physical and cognitive recovery of hospitalized persons living with dementia during hospitalization and the subsequent 60-day post-acute period. Additionally, the model aims to enhance the preparedness and experience of family care partners. In the parent study, participants were randomized to either the intervention group, which implemented the Fam-FFC model, or the control group, which received education only. Fam-FFC obtained approval from the University Institutional Review Board and the study protocol has been published (Boltz et al., Citation2018). Before data collection, written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Sample and setting

Data were collected from 424 care receiver and care partner dyads from six medical units across three hospitals in Pennsylvania. In each hospital, the two units were randomized to either the control or intervention group. Family care partners were eligible to participate if they were at least 18 years old, proficient in English or Spanish, and closely related to the care receiver as a significant other, defined by the care receiver or a legally authorized individual providing primary oversight and support. Care partners who could not recall at least two words from a three-word recall were excluded.

Care receivers were eligible to participate if they were aged 65 years or older, spoke English or Spanish, resided in the community before hospitalization, and screened positive for dementia with a score of ≤ 25 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA; Nasreddine et al., Citation2005) and ≥ 2 on the AD8 Dementia Screening Interview (Galvin et al., Citation2006). Additionally, care receivers had to have a diagnosis of very mild to moderate stage dementia, indicated by a score of 0.5 to 2.0 on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR; Morris, Citation1997), demonstrate functional impairment with a score of ≥ 9 on the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ; Pfeffer et al., Citation1982), and have a family care partner participate throughout the study. Care receivers were ineligible for participation if they had a major acute psychiatric disorder, a significant neurological condition affect cognition other than dementia, were admitted from a nursing home, or enrolled in hospice care.

Procedures

After confirming eligibility and obtaining consent, trained research evaluators, blinded to the intervention, obtained data from both care receivers and family care partners. Within 48 hours of hospital admission, data on care receiver demographics, cognition, and comorbidities were collected via electronic medical records or direct observation by the research evaluator. Family care partners reported data on the care receiver’s BPSD, delirium severity, and physical function within 72 hours of the care receiver’s hospital discharge. During this same 72-hour period following the care receiver’s hospital discharge, information on the family care partners’ demographics, preparedness, and desire to seek long-term care was also collected through family care partner self-report.

Measures

Descriptive data for both care partners and care receivers included age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, and marital status. Additionally, for care partners, information was reported on whether they lived with the care receiver, their employment status outside the home, and the number of hours they worked outside of the home (per week).

Independent variable

Care partner preparedness was measured using the Preparedness for Caregiving Scale (PCS), an 8-item instrument that evaluates various domains of perceived preparedness in caregiving, including physical and emotional support, arranging support services, and managing care partner stress (Archbold et al., Citation1990). Each item is scored from 0 (not at all prepared) to 4 (very well prepared). Total scores range from 0 to 32, and higher scores reflect greater perceived preparedness. Previous testing of the PCS has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Hudson & Hayman-White, Citation2006; Kuzmik et al., Citation2021; Petruzzo et al., Citation2017; Pucciarelli et al., Citation2014).

Outcome variable

Care partner desire to seek long-term care admission was assessed using the Desire to Institutionalize Scale (DIS; Morycz, Citation1985). This 6-item instrument evaluates the extent to which a care partner has considered placing the care receiver in a nursing home. In this study, the scale measured the care partner’s desire to seek long-term care admission over the past month, with responses being “yes” or “no.” Total scores range from 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating a greater desire to seek long-term care. The DIS has established reliability and predictive accuracy for actual long-term nursing home placement (Gallagher et al., Citation2011; Morycz, Citation1985; Spitznagel et al., Citation2006; Spruytte et al., Citation2001).

Mediator variables (care receiver clinical factors)

Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) were assessed with the Brief Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI-Q; Cummings et al., Citation1994). This instrument consists of 12 domains, including delusions, hallucinations, agitation/aggression, dysphoria/depression, anxiety, apathy, irritability, euphoria, disinhibition, aberrant motor behavior, sleep disturbances, and appetite and eating disturbances. The severity of behavioral expressions for each domain/item was assessed using a three-point scale: 1 for mild, 2 for moderate, and 3 for severe. Total scores, ranging from 0 to 36, were derived by summing each item, with higher scores indicating more severe BPSD. The NPI-Q has demonstrated evidence of validity and reliability (Cummings et al., Citation1994).

Comorbidities were categorized using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), a weighted tool that accounts for both the quantity and severity of various co-morbid diseases (van Doorn et al., Citation2001). Total scores can range from 0 to 30, with higher scores signifying an increased number of comorbidities. The CCI is a valid and reliable measure of disease burden (van Doorn et al., Citation2001).

Delirium severity was evaluated using the Confusion Assessment Method Short Form (CAM-S), a 4-item measure that examines acute onset, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness (Inouye et al., Citation2014). Total scores on the CAM-S can range from 0 to 7, with higher scores reflecting increased severity of delirium. Prior studies have shown that the CAM-S has strong psychometric properties (Inouye et al., Citation2014).

Physical function was assessed with the Barthel Index (BI), a 10-item measure that evaluates activities of daily living related to mobility, self-care, and bowel/bladder management (Mahoney & Barthel, Citation1965). Total scores can range from 0 to 100, where higher scores represent greater functional independence. Previous studies have confirmed the BI’s reliability and validity (Mahoney & Barthel, Citation1965; Ranhoff, Citation1997).

Cognition was measured using the MoCA, a cognitive tool that evaluates executive function, orientation, memory, abstract thinking, and attention (Nasreddine et al., Citation2005). The MoCA has shown excellent sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing between mild cognitive impairment, no dementia, and dementia. Validation studies of the MoCA have been conducted in populations with diverse cultural backgrounds (Bernstein et al., Citation2011; Goldstein et al., Citation2014).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics, including mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables, were utilized to characterize the sample. Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to examine the independence of key variables. As per Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation2013), any variables that did not correlate with either the independent variable (i.e., care partner preparedness) or the dependent variable (i.e., care partner desire to seek long-term care admission) were omitted from the mediation analysis. The presence of multicollinearity was indicated by high correlations among variables, where the correlation coefficients (r values) exceeded 0.9 (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2013).

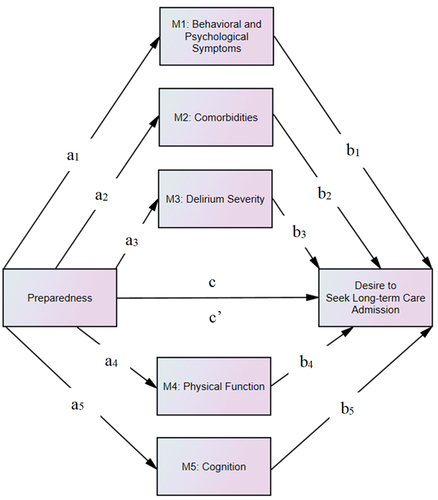

The mediating effects of care receiver clinical factors (BPSD, comorbidities, delirium severity, physical function, and cognition) on the relationship between care partner preparedness (independent variable) and care partner desire to seek long-term care admission (dependent variable) were analyzed using a nonparametric bootstrapping method with 5,000 samples (Hayes, 2017; Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008). In the multiple mediation model, we obtained unstandardized path coefficients (a, b, c, and c’) as shown in . The a-path showed the relationship between care partner preparedness and the mediator variables, and the b-path indicated the association between the mediator variables and care partner desire to seek long-term care admission. The relationship between care partner preparedness and desire to seek long-term care admission was represented by the c-path (total effect) and c’-path (direct effect), first without considering the mediators and then after accounting for them, respectively. Moreover, the mediation effect, known as the indirect effect, quantified the combined impact of the a-path and b-path on each mediator’s outcome, calculated as the product of a*b. Mediation was determined by the significance of the indirect effect, indicated by the absence of zero within the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval. The mediation analysis controlled for effects of the intervention (parent study control versus intervention group), care receiver length of hospital stay, and care partner characteristics including age, gender, race, and cohabitation status with the care receiver (Eska et al., Citation2013; Kuzmik et al., Citation2021; López et al., Citation2012; McCaskill et al., Citation2011; Vandepitte et al., Citation2018). The level of statistical significance was established at p ≤ .05, and analyses were performed using SPSS and AMOS (version 27; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Figure 1. Path diagram of the hypothesized multiple mediation model for the effect of care partner preparedness on desire to seek long-term care through proposed mediators.

Results

presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of the care partners and care receivers (N = 424). Majority of the care partners identified as female (72.4%), with an average age of 62.0 ± 14.0 years. The care partners were either non-Hispanic White (65.8%) or non-Hispanic Black (34.2%). Among the care partners, 61.3% were married, 65.1% had education beyond high school, and 59.9% cohabited with the care receiver. Additionally, 44.6% of care partners were employed outside of the home, dedicating an average of 40.2 ± 14.1 hours per week. Care partners also indicated low levels of desire to seek long-term care (DTI, 1.4 ± 2.4) and reported a moderate level of perceived preparedness (PCS, 23.8 ± 6.7).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of sample (N = 424).

Among the care receivers, the average age was 81.5 ± 8.3 years, with 58.3% identified as female. Most of the care receivers were non-Hispanic White (65.3%), and one-third were non-Hispanic Black (34.7%). The average length of hospital stay for the care receivers was 6.4 ± 4.3 days. In addition, 40.3% of the care receivers had completed high school, and 54.5% were widowed, divorced, or separated. The care receivers had an average of 4.3 ± 2.8 comorbidities. They also demonstrated some form of cognitive impairment (MoCA, 11.8 ± 7.0), moderate functional dependence (BI, 68.3 ± 27.3), low BPSD (NPI, 6.3 ± 5.9), and slight delirium severity (CAM-S, 1.0 ± 1.5). Care receivers were admitted to the hospital for various reasons, with the most common being infections (19.8%), followed by altered mental status, including delirium (11.1%), and pain (10.8%). Additionally, 39.6% developed delirium during the hospitalization.

displays the correlations among the study variables. The strongest correlation coefficient among the variables was .33, indicating that all variables met the assumptions of multicollinearity. Findings showed that lower care partner preparedness was associated with higher desire to seek long-term care. Except for comorbidities, all other potential mediators were significantly associated with care partner preparedness or desire to seek long-term care. Hence, comorbidities were excluded as a potential mediator in the subsequent analysis.

Table 2. Bivariate correlations among study variables.

shows the effect of care partner preparedness on desire to seek long-term care through BPSD, delirium severity, physical function, and cognition as potential mediators. Significant total and direct effects of care partner preparedness on desire to seek long-term care were found (c-path; B = −.079, p < .001 and c’-path; B = −.046, p = .007, respectively). Care partner preparedness was significantly associated with each potential mediator (a-path): BPSD (B = −.145, p < .001), delirium severity (B = −.033, p = .001), physical function (B = .550, p = .003), and cognition (B = .160, p = .002). However, only delirium severity (B = .340, p = .022) and physical function (B = −.023, p = .046) had significant effects on desire to seek long-term care admission (b-path).

Table 3. Results of multiple mediation analysis (N = 424).

The indirect effects of preparedness on desire to seek long-term care admission were significant via delirium severity (B = −.011; 95% CI = −.019, −.003) and physical function (B = −.013; 95% CI = −.027, −.001). Specifically, the indirect effect through delirium severity accounted for 13.9% of the total effect, and the indirect effect through physical function accounted for 16.5% of the total effect. The indirect effects of BPSD (B = −.005; 95% CI = −.007, .005) and cognition (B = −.004; 95% CI = −.010, .002) were not significant. Therefore, decreased preparedness was associated with higher delirium severity and, in turn, higher delirium severity was associated with increased desire to seek long-term care admission. Additionally, higher care partner preparedness was associated with increased physical function, and, in turn, lower physical function was associated with greater desire to seek long-term care admission.

Discussion

In the present study, we explored the mediating roles of care receiver clinical factors (i.e., BPSD, comorbidities, delirium severity, physical function, and cognition) on the relationship between care partner preparedness and care partner desire to seek long-term care admission for persons living with dementia at hospital discharge. The hypothesis of this study was partially supported, revealing that factors such as delirium severity and physical function partially mediated the effect of care partner preparedness and care partner desire to seek long-term care admission. However, factors such as BPSD, comorbidities, and cognition did not mediate the relationship between care partner preparedness and desire to seek long-term care admission. These results highlight that care partner preparedness, as well as care receiver clinical factors (i.e., delirium severity and physical function), are significant predictors of the care partner’s desire to seek long-term care at hospital discharge. Interventions should focus on enhancing care partner preparedness and addressing delirium severity and physical function of the hospitalized person with dementia to prevent unwanted nursing home placement at hospital discharge.

Our findings align with previous research, demonstrating that lower care partner preparedness is associated with greater desire to seek long-term care for hospitalized persons with dementia (Kuzmik et al., Citation2023). Additionally, the finding that higher delirium severity and lower physical function were associated with an increased desire to seek long-term care admission is consistent with other studies involving persons living with dementia (Toot et al., Citation2017; Vo et al., Citation2023). This study builds on previous research by exploring the interplay between care partner preparedness, care receiver clinical factors, and care partner desire to seek long-term care at hospital discharge. Recognizing care receiver delirium severity and physical function as mediators between care partner preparedness and the desire to seek long-term care underscore the need for specific interventions and strategies to improve care partner preparedness and reduce unnecessary or unwanted long-term care placements at hospital discharge. Moreover, the emergence of delirium and its dramatic presentation during hospitalization can cause significant stress in the care partner. Thus, due to the possibility of delirium cases emerging during the hospital stay, it is important to focus on hospital-based interventions to prevent delirium. Such interventions could include routine delirium screening, early mobilization, and tailored care plans that promote comfort, nutrition, and emotional support, which may help mitigate delirium onset and severity. Future research should conduct a longitudinal examination of the mediating roles of care receiver delirium severity and physical function on the relationship between care partner preparedness and the desire to seek long-term care, extending beyond the immediate post-hospitalization period. Additionally, using causal modeling techniques, such as structural equation modeling (SEM), will help better identify and understand the complex causal pathways and interactions between care partner preparedness, care receiver clinical factors, and care partner desire to seek long-term care.

Delirium severity and physical function showed modest mediating effects (13.9% and 16.5%, respectively) on the relationship between care partner preparedness and desire to seek long-term care admission. These findings underscore the complexity of factors influencing caregiving decisions for persons living with dementia. Additional factors such as health literacy, social support networks, and financial burden should be explored to gain deeper insights into this relationship.

Unlike other studies (Gaugler et al., Citation2009; Saposnik et al., Citation2011; Toot et al., Citation2017), we found that care receiver factors including BPSD, comorbidities, and cognition did not mediate the relationship between care partner preparedness and desire to seek long-term care admission. The differing results could indicate that the findings are influenced by the unique features of the sample, underscoring the need for careful assessment. In our sample, persons with dementia experienced minimal BPSD and had few comorbidities, suggesting that the low levels of these factors may have resulted in a failure to detect a difference in the desire to seek long-term care. Furthermore, only care receivers with mild to moderate dementia were included in our sample. Future research is warranted to conduct a more in-depth investigation of persons with dementia at hospital discharge, considering different levels of severity across care receiver clinical factors to explore the relationship between care partner preparedness and desire to seek long-term care.

In this study, we highlight a vulnerable care receiver population that could benefit from intervention at hospital discharge to prevent undesired long-term care admissions. Integrating care partner preparedness and care receiver clinical factors (i.e., delirium severity and physical function) into the evaluation and planning process at hospital discharge may minimize care partner desire to seek long-term care during this transition period. Healthcare providers (i.e., clinicians and service providers) could implement an instrument like the PCS at hospital discharge to identify specific areas of need for improving care partner preparedness (Kuzmik et al., Citation2021, Citation2023) while simultaneously addressing care receiver delirium severity and physical function, helping to avoid admission to a long-term care facility. Recent evidence suggests that partnering with family care partners during and after hospitalization and preparing them with information and guidance on promoting functional recovery supports the care receiver’s return to baseline function (Boltz et al., Citation2023). By prioritizing these areas, clinicians and service providers can develop comprehensive discharge plans that support both care receivers and their care partners, leading to improved care partner preparedness, better management of care receivers’ delirium severity and physical function, and a lower incidence of undesired long-term care admissions.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths, including a large sample size and a focus on a typically underrepresented population of hospitalized persons living with dementia. Notably, it is among the few studies to explore the mediating roles of care receiver clinical characteristics on the relationship between care partner preparedness and the desire to seek long-term care, addressing a crucial timepoint of hospital discharge that has received inadequate attention for this vulnerable group. Additionally, the inclusion criteria required rigorous screening through cognitive assessments to identify mild moderate dementia (Galvin et al., Citation2006; Morris, Citation1997; Nasreddine et al., Citation2005; Pfeffer et al., Citation1982).

This study was limited by its reliance on secondary analysis and cross-sectional data. Consequently, factors such as socioeconomic status, competing demands, living environments, length of caregiving, and patients’ psychotropic medication use and medical complexity, which could influence care partner desire to seek long-term care admission, were not thoroughly examined. Further, due to limitations in the data, we were not able to identify the exact onset of delirium that was present upon admission and the potential contribution of a protracted pre-admission delirium upon the care partners’ desire to see long-term care. In addition, the generalizability of our findings is limited by the inclusion of only care receiver/care partner dyads from three hospitals in Pennsylvania. Lastly, using self-report measures during data collection may have introduced biases associated with social desirability and memory-related issues.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, our findings indicate that care receiver factors, including delirium severity and physical function, mediated the relationship between care partner preparedness and care partner desire to seek long-term care admission. The results underscore the need for clinicians and service providers to prioritize care partner preparedness and account for care receiver factors (i.e., delirium severity and physical function) in clinical interventions at hospital discharge to minimize undesired long-term care admissions. Future research is needed to expand this work by including diverse populations, such as persons living with dementia and their care partners from various cultures and geographic Locations.

CLINICAL IMPLICATION

Implement tools like the PCS at hospital discharge to identify and address areas needing improvement in care partner preparedness, preventing unwanted long-term care admissions.

Focus on managing care receiver delirium severity and physical function during discharge planning to support their return to baseline function and avoid unnecessary long-term care placement.

Engage family care partners during and after hospitalization, providing them with information and guidance to promote the care receiver’s recovery from delirium and improvement in physical function, minimizing the desire for long-term care admissions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2024). 2024 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures

- Andersen, R. M. (1995). Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health & Social Behavior, 36(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137284

- Archbold, P. G., Stewart, B. J., Greenlick, M. R., & Harvath, T. A. (1990). Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Research in Nursing & Health, 13(6), 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770130605

- Bernstein, I. H., Lacritz, L., Barlow, C. E., Weiner, M. F., & DeFina, L. F. (2011). Psychometric evaluation of the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) in three diverse samples. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 25(1), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2010.533196

- Boltz, M., Kuzmik, A., Resnick, B., Trotta, R., Mogle, J., BeLue, R., Leslie, D., & Galvin, J. E. (2018). Reducing disability via a family centered intervention for acutely ill persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: Protocol of a cluster-randomized controlled trial (fam-ffc study). Trials, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2875-1

- Boltz, M., Mogle, J., Kuzmik, A., BeLue, R., Leslie, D., Galvin, J. E., Resnick, B., & Makaroun, L. K. (2023). Testing an intervention to improve posthospital outcomes in persons living with dementia and their family care partners. Innovation in Aging, 7(7), igad083. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igad083

- Brent, R. J. (2022). Life expectancy in nursing homes. Applied Economics, 54(16), 1877–1888. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2021.1983138

- Bu, F., & Rutherford, A. (2018). Dementia, home care and institutionalisation from hospitals in older people. European Journal of Ageing, 16(3), 283–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-018-0493-0

- Cummings, J. L., Mega, M., Gray, K., Rosenberg-Thompson, S., Carusi, D. A., & Gornbein, J. (1994). The neuropsychiatric inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology, 44(12), 2308–2314. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308

- Dauphinot, V., Ravier, A., Novais, T., Delphin-Combe, F., Moutet, C., Xie, J., Mouchoux, C., & Krolak-Salmon, P. (2016). Relationship between comorbidities in patients with cognitive complaint and caregiver burden: A cross-sectional study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 17(3), 232–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2015.10.011

- Eska, K., Graessel, E., Donath, C., Schwarzkopf, L., Lauterberg, J., & Holle, R. (2013). Predictors of institutionalization of dementia patients in mild and moderate stages: A 4-year prospective analysis. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders Extra, 3(1), 426–445. https://doi.org/10.1159/000355079

- Fagundes, D. F., Costa, M. T., Alves, B. B. D. S., Carneiro, L. S. F., Nascimento, O. J. M., Leão, L. L., Guimarães, A. L. S., de Paula, A. M. B., & Monteiro-Junior, R. S. (2021). Dementia among older adults living in long-term care facilities: An epidemiological study. Dementia and Neuropsychologia, 15(4), 464–469. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-57642021dn15-040007

- Fogg, C., Griffiths, P., Meredith, P., & Bridges, J. (2018). Hospital outcomes of older people with cognitive impairment: An integrative review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(9), 1177–1197. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4919

- Fong, T. G., Jones, R. N., Marcantonio, E. R., Tommet, D., Gross, A. L., Habtemariam, D., Schmitt, E., Yap, L., & Inouye, S. K. (2012). Adverse outcomes after hospitalization and delirium in persons with Alzheimer disease. Annals of Internal Medicine, 156(12), 848–W296. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-156-12-201206190-00005

- Gallagher, D., Ni Mhaolain, A., Crosby, L., Ryan, D., Lacey, L., Coen, R. F., Walsh, C., Coakley, D., Walsh, J. B., Cunningham, C., & Lawlor, B. A. (2011). Determinants of the desire to institutionalize in Alzheimer’s caregivers. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 26(3), 205–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317511400307

- Galvin, J. E., Roe, C. M., Xiong, C., & Morris, J. C. (2006). Validity and reliability of the AD8 informant interview in dementia. Neurology, 67(11), 1942–1948. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000247042.15547.eb

- Gaugler, J. E., Yu, F., Krichbaum, K., & Wyman, J. F. (2009). Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Medical Care, 47(2), 191–198. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818457ce

- Goldstein, F. C., Ashley, A. V., Miller, E., Alexeeva, O., Zanders, L., & King, V. (2014). Validity of the Montreal cognitive assessment as a screen for mild cognitive impairment and dementia in African americans. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 27(3), 199–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988714524630

- Hébert, R., Dubois, M.-F., Wolfson, C., Chambers, L., & Cohen, C. (2001). Factors associated with long-term institutionalization of older people with dementia: Data from the Canadian study of health and aging. Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 56(11), M693–M699. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.11.M693

- Hessler, J. B., Schäufele, M., Hendlmeier, I., Junge, M. N., Leonhardt, S., Weber, J., & Bickel, H. (2017). Behavioural and psychological symptoms in general hospital patients with dementia, distress for nursing staff and complications in care: Results of the general hospital study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 27(3), 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016001098

- Hudson, P. L., & Hayman-White, K. (2006). Measuring the psychosocial characteristics of family caregivers of palliative care patients: Psychometric properties of nine self-report instruments. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 31(3), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.07.010

- Inouye, S. K., Kosar, C. M., Tommet, D., Schmitt, E. M., Puelle, M. R., Saczynski, J. S., Marcantonio, E. R., & Jones, R. N. (2014). The CAM-S: Development and validation of a new scoring system for delirium severity in 2 cohorts. Annals of Internal Medicine, 160(8), 526–533. https://doi.org/10.7326/M13-1927

- Jhang, K.-M., Liao, G.-C., Wang, W.-F., Tung, Y.-C., Yen, S.-W., & Wu, H.-H. (2024). Caregivers’ burden on patients with dementia having multiple chronic diseases. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 17, 1151–1163. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S454796

- Kuzmik, A., BeLue, R., Resnick, B., Rodriguez, M., Berish, D., Galvin, J. E., & Boltz, M. (2023). Caregiver preparedness is associated with desire to seek long-term care admission of hospitalized persons with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 38(9), e6006. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.6006

- Kuzmik, A., Boltz, M., Resnick, B., & BeLue, R. (2021). Evaluation of the Caregiver preparedness scale in African American and white caregivers of persons with dementia during post-hospitalization transition. Journal of Nursing Measurement, JNM-D-20–00087. https://doi.org/10.1891/JNM-D-20-00087

- Livingston, G., Leavey, G., Manela, M., Livingston, D., Rait, G., Sampson, E., Bavishi, S., Shahriyarmolki, K., & Cooper, C. (2010). Making decisions for people with dementia who lack capacity: Qualitative study of family carers in UK. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed), 341(aug18 1), c4184. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c4184

- López, J., Losada, A., Romero-Moreno, R., Márquez-González, M., & Martínez-Martín, P. (2012). Factors associated with dementia caregivers’ preference for institutional care. Neurología (English Edition), 27(2), 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrleng.2012.03.004

- Mahoney, F. I., & Barthel, D. W. (1965). Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Maryland State Medical Journal, 14, 61–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/t02366-000

- McCann, J. J., Hebert, L. E., Li, Y., Wolinsky, F. D., Gilley, D. W., Aggarwal, N. T., Miller, J. M., & Evans, D. A. (2005). The effect of adult day care services on time to nursing home placement in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease. The Gerontologist, 45(6), 754–763. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/45.6.754

- McCaskill, G. M., Burgio, L. D., Decoster, J., & Roff, L. L. (2011). The use of Morycz’s desire-to-institutionalize scale across three racial/ethnic groups. Journal of Aging & Health, 23(1), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264310381275

- Mockford, C. (2015). A review of family carers’ experiences of hospital discharge for people with dementia, and the rationale for involving service users in health research. Journal of Healthcare Leadership, 7, 21–28. https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S70020

- Morris, J. C. (1997). Clinical dementia rating: A reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. International Psychogeriatrics, 9(Suppl 1), 173–176. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610297004870

- Morycz, R. K. (1985). Caregiving strain and the desire to institutionalize family members with Alzheimer’s disease: Possible predictors and model development. Research on Aging, 7(3), 329–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027585007003002

- Nasreddine, Z. S., Phillips, N. A., Bédirian, V., Charbonneau, S., Whitehead, V., Collin, I., Cummings, J. L., & Chertkow, H. (2005). The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(4), 695–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

- Nikmat, A. W., Hawthorne, G., & Al-Mashoor, S. H. (2015). The comparison of quality of life among people with mild dementia in nursing home and home care—A preliminary report. Dementia (London, England), 14(1), 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301213494509

- Olsen, C., Pedersen, I., Bergland, A., Enders-Slegers, M.-J., Jøranson, N., Calogiuri, G., & Ihlebæk, C. (2016). Differences in quality of life in home-dwelling persons and nursing home residents with dementia – a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 16(1), 137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0312-4

- Petruzzo, A., Paturzo, M., Buck, H. G., Barbaranelli, C., D’Agostino, F., Ausili, D., Alvaro, R., & Vellone, E. (2017). Psychometric evaluation of the caregiver preparedness scale in caregivers of adults with heart failure. Research in Nursing & Health, 40(5), 470–478. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21811

- Pfeffer, R. I., Kurosaki, T. T., Harrah, C. H., Chance, J. M., & Filos, S. (1982). Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. Journal of Gerontology, 37(3), 323–329. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/37.3.323

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

- Pucciarelli, G., Savini, S., Byun, E., Simeone, S., Barbaranelli, C., Vela, R. J., Alvaro, R., & Vellone, E. (2014). Psychometric properties of the caregiver preparedness scale in caregivers of stroke survivors. Heart and Lung, 43(6), 555–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.08.004

- Ranhoff, A. H. (1997). Reliability of nursing assistants’ observations of functioning and clinical symptoms and signs. Aging (Milan, Italy), 9(5), 378–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03339617

- Saposnik, G., Cote, R., Rochon, P. A., Mamdani, M., Liu, Y., Raptis, S., Kapral, M. K., Black, S. E., & Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network, & Stroke Outcome Research Canada (SORCan) Working Group. (2011). Care and outcomes in patients with ischemic stroke with and without preexisting dementia. Neurology, 77(18), 1664–1673. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823648f1

- Spitznagel, M. B., Tremont, G., Davis, J. D., & Foster, S. M. (2006). Psychosocial predictors of dementia caregiver desire to institutionalize: Caregiver, care recipient, and family relationship factors. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 19(1), 16–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988705284713

- Spruytte, N., Van Audenhove, C., & Lammertyn, F. (2001). Predictors of institutionalization of cognitively-impaired elderly cared for by their relatives. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(12), 1119–1128. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.484

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Pearson.

- Tanuseputro, P., Hsu, A., Kuluski, K., Chalifoux, M., Donskov, M., Beach, S., & Walker, P. (2017). Level of need, divertibility, and outcomes of newly admitted nursing home residents. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 18(7), 616–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.02.008

- Toot, S., Swinson, T., Devine, M., Challis, D., & Orrell, M. (2017). Causes of nursing home placement for older people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610216001654

- Vandepitte, S., Putman, K., Van Den Noortgate, N., Verhaeghe, S., Mormont, E., Van Wilder, L., De Smedt, D., & Annemans, L. (2018). Factors associated with the caregivers’ desire to institutionalize persons with dementia: A cross-sectional study. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 46(5–6), 298–309. https://doi.org/10.1159/000494023

- van Doorn, C., Bogardus, S. T., Williams, C. S., Concato, J., Towle, V. R., & Inouye, S. K. (2001). Risk adjustment for older hospitalized persons: A comparison of two methods of data collection for the Charlson index. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(7), 694–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00367-X

- Vo, Q. T., Koethe, B., Holmes, S., Simoni-Wastila, L., & Briesacher, B. A. (2023). Patient outcomes after delirium screening and incident Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias in skilled nursing facilities. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 38(2), 414–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07760-6