ABSTRACT

In this observational study, recordings of 40 individual supervision meetings over six months for five supervisory dyads in an Irish, transdisciplinary youth mental health service were analyzed and illustrated according to the Seven-Eyed model of supervision. Results offer empirical support regarding the model’s relevance for supervision practice, provide practice-based evidence to elaborate aspects of the model, and show the model’s value in identifying areas of practice that may benefit from development. Illustrations of some supervision exchanges are shared which contribute to our understanding of the complexity of working at the personal-professional boundary, particularly in workplace, transdisciplinary supervision involving dual roles.

The practice of clinical supervision is understood to have three main functions: formative, contributing to supervisees’ continued professional development; normative, involving professional, ethical review of supervisees’ work; and restorative, supporting supervisees’ welfare and resilience (Proctor, Citation1988). In many professions and countries, clinical supervision of practice is required only during training, but in some contexts this requirement is career-long (e.g., psychotherapy in Ireland and the United Kingdom [UK]). Even when not required, the benefits of regular, ongoing supervision are increasingly recognized across a greater range of professions (Hawkins & McMahon, Citation2020), and many professionals voluntarily attend supervision. For instance, in a survey of qualified Irish psychologists, 91% reported attending regular supervision (McMahon & Errity, Citation2015). Furthermore, within the Irish public health context (the setting for this study), continuing supervision is promoted as part of good clinical governance: “all health and social care professionals should participate in regular, high quality, consistent and effective supervision” (Health Service Executive, Citation2015, p. 5).

However, research investigating the practice of supervision is still a developing area. The largest body of evidence to date involves supervisees’ reported experience of its benefits, which include increased self-awareness, knowledge, skills, self-efficacy, and strengthened client relationships (Watkins, Citation2011; Wheeler & Richards, Citation2007; Wilson et al., Citation2016). There are also reports of supervisees experiencing harmful and inadequate supervision (Ellis et al., Citation2015), indicating the serious professional responsibility that comes with supervisory work. Investigating the impact of supervision on clients is methodologically challenging and has produced mixed results to date (e.g., Bambling et al., Citation2006; Whipple et al., Citation2020). However, attending supervision has been associated with improved competency (e.g., Alfonsson et al., Citation2020; Schwalbe et al., Citation2014), greater job retention and satisfaction, and reduced burnout and stress (Dawson et al., Citation2013; Wallbank, Citation2013).

In addition to continuing to advance research in the above areas, there have been calls for observational, longitudinal studies to more closely investigate the processes involved in supervisory practice (Bernard & Luke, Citation2015; Goodyear et al., Citation2016; Watkins, Citation2020). Such studies are important to illuminate and guide good practice and to explore challenges. At a theoretical level, supervision models have been developed to guide practice, including those which are aligned with particular psychotherapy approaches (e.g., Milne & Reiser, Citation2017), developmental models which attend to the supervisee’s developmental stage (e.g., Stoltenberg & McNeill, Citation2010), and social role or process models which identify supervision functions and processes (e.g., Hawkins & McMahon, Citation2020). New supervision models continue to emerge, which Bernard and Goodyear (Citation2019) have dubbed ‘second generation’ models, as they build on existing models or focus on specific aspects (e.g., Attachment-Caregiving model, Fitch et al., Citation2010). As many as 52 models of supervision were identified in a recent review (Simpson-Southward et al., Citation2017), the authors reporting inconsistency in the elements included across the models and noting concern that over half of the models lacked any focus on the client. They also found minimal empirical evidence for the models, listing only 17 studies since the 1980s investigating the construct validity of just seven models, only three researching the impact of practising according to a supervision model on the supervisee, and none studying impact on client outcomes. It is also of note that only one of these studies was carried out within the last 20 years, indicating a clear need to investigate the applicability and impact of supervision models in current contexts.

Amongst the available models, the Seven-Eyed model, a social role/process model, is widely recognized as a core model in supervisor training and practice in Ireland and the UK (Carroll, Citation2020; Creaner & Timulak, Citation2016; Dunsmuir & Leadbetter, Citation2010; Townend et al., Citation2002). It has also been described as the most influential model in coaching supervision internationally (Joseph, Citation2017). It is a transtheoretical, relational model, drawing from systemic, humanistic, psychoanalytic, and cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy theories, as well as adult learning theory. Two interlocking systems are depicted – the client work system (the client, the supervisee’s interventions, and the client-supervisee relationship), and the supervisory system (the supervisee, the supervisor, and the supervisory relationship) – and the wider contexts of these two systems, thus making up the seven modes or ‘eyes’ of the model (see ).

Figure 1. Seven-Eyed model of supervision (Hawkins & McMahon, Citation2020, printed with permission).

At the time of the current study, descriptions of the seven modes were available in Supervision in the Helping Professions (4th ed., Hawkins & Shohet, Citation2012, pp. 88–90), summarized here:

Mode 1: Focus on the client: developing awareness of the observed, experienced reality of the client before moving into formulating; “how they breathe, speak, look, gesture, etc.; their language, metaphors, images and the story of their life as they told it.”

Mode 2: Focus on interventions: attending to what, how and why interventions were used; and planning/rehearsing interventions, anticipating their impact, aiming to “increase the supervisee’s choices and skills.”

Mode 3: Focus on the client-supervisee relationship: exploring conscious and unconscious dynamics in this relationship, including working with imagery or metaphor, aiming to help supervisees to “step out of their own perspective and develop a greater insight.”

Mode 4: Focus on the supervisee: exploring how supervisees are consciously and unconsciously affected by their work, including feelings, thoughts, actions, and countertransference reactions to their clients; and also attending to supervisees’ wellbeing and professional development, aiming to increase capacity to work in a steady, resourced way.

Mode 5: Focus on the supervisory relationship: attending to the quality of the supervision work and relationship, and exploring how it “may unconsciously be playing out or paralleling the hidden dynamics of the work with clients.”

Mode 6: Focus on the supervisor: supervisors focusing on their own process, including thoughts, feelings and images regarding the supervisee and their work, to provide an additional source of information about the supervisory or client relationships.

Mode 7: Focus on the wider context: including a focus on the familial, social, cultural, professional, organizational, political, and economic context of all stakeholders, exploring how the wider context “impinges upon and colours” the work.

Practitioners have elaborated the usefulness of the Seven-Eyed model for supervision practice in various professions and contexts (international coaches: Henderson & O’Riordan, Citation2020; Irish clinical psychologists: McMahon, Citation2014; Irish social care workers: McLaughlin et al., Citation2019; UK nurses: Regan, Citation2012). However, as with other supervision models, empirical research is scarce. Just one published study was found, involving interviews with 57 Australian coaches, where their reflections on issues explored in their supervision groups were coded according to the Seven-Eyed model’s modes (double-coding being used; Lawrence, Citation2019). This study found that exploring interventions (mode 2; 95%) was most common, followed by a focus on the client (mode 1; 67%), the coach (mode 4; 49%), and external factors (mode 7; 40%), with less attention to the coach-client relationship (mode 3; 18%) and none to the supervisory relationship (mode 5) or the supervisor (mode 6). This indicated that some modes were rarely utilized, despite the study’s supervisors (also interviewed) most frequently mentioning the Seven-Eyed model as a guide for practice. Further investigation of the model’s relevance for supervisory practice is needed, including detailed study of less utilized modes.

Given a clear need for further research on supervision models and processes generally, and the paucity of research regarding the Seven-Eyed model, the current study had the following aims: to analyze how the Seven-Eyed model maps onto individual supervision practice in a naturalistic workplace setting; to gain practice-based evidence for the model and contribute to its theoretical elaboration in the 5th edition of Supervision in the Helping Professions (being written at the time of the study; Hawkins & McMahon, Citation2020); and to offer illustrations of supervisory interventions and dialogs.

Method

Ethics

Ethical approval for this study was granted by both the first author’s university and the study site’s research ethics committees. Key ethical issues were ensuring confidentiality and anonymity; given the small number of male employees in the study site, gender-neutral pseudonyms and ‘she/her’ are used for all participants. Following receiving a full study report, all participants gave consent for the study site to be identified or identifiable through study author affiliations and/or description of the organization’s work.

Study setting and procedure

The study setting was an Irish primary care youth mental health organization providing a brief assessment and therapeutic intervention service of up to eight sessions for young people (aged 12–25 years) experiencing mild/moderate mental health difficulties. The organization was also engaged in community mental health promotion work. The staff worked in transdisciplinary teams, which included clinical, counseling and educational psychologists, social workers, mental health nurses, and occupational therapists. At the time of the study, 14 clinical supervisors were supervising 46 clinical staff, the latter also having separate line management/administrative supervisors.

An invitation e-mail to participate in a six-month observational study of individual clinical supervision practice was sent to all clinical staff, followed up by two reminder e-mails. Before starting, participants met with the first author to discuss the study protocol in person or by video link. During the study, the supervisors audio-recorded all individual supervision meetings with their study partner and uploaded recordings to a secure digital platform. There was occasional e-mail contact between the first author and participants regarding technical difficulties with recording/uploading, and to clarify study procedures/timings. Close to the end of the study period, preliminary results, which were being presented at a national conference, were shared with participants (the impact of this is included in the results section).

Participants

Five supervision dyads participated in the study (N = 10: 5 supervisors and 5 supervisees), four of whom were transdisciplinary dyads. At the start of the study, the dyads had worked together for an average of 15 months (range = 2–28 months; SD = 9.9). Three dyads completed the full six months in the study and two finished slightly earlier (after 5 months, and 4.5 months) as their supervision relationships ended due to staff changes.

Supervisor participants were qualified clinical psychologists, occupational therapists, or social workers, practising for an average of 11 years (range = 3–20 years; SD = 7.4). All supervisors had attended at least six days’ clinical supervisor training (M = 14.3 days; range = 6–40 days; SD = 14.5) and averaged 7.4 years’ supervisory experience (range = 1–16 years: SD = 6.1). The first author had facilitated four days of clinical supervision training with the organization’s supervisors over the two years before the study commenced, providing introductory training in key supervisory competencies (e.g., contracting and working with the supervisory relationship) and in two supervision models of practice (the Seven-Eyed model, and the Cyclical model; Page & Wosket, Citation2015).

Supervisee participants were qualified counseling psychologists, occupational therapists, or social workers, practising for 4.6 years on average (range = 2–7 years; SD = 1.8).

Measure

Forty clinical supervision meetings were recorded (total = 52.6 hrs), on average eight per dyad (range = 6–10; SD = 1.4). Three meetings during the study period were not recorded due to technical issues. The mean length of meetings was 1.3 hrs (range = 53–107 mins; SD = 0.25). All recordings were transcribed verbatim, including nonverbal content (e.g., laughter, sighs, pauses).

Data analysis

A qualitative content analysis approach (QCA) was followed as a systematic method of describing and quantifying qualitative data (Mayring, Citation2000; Schreier, Citation2012). Content analysis is also recognized as a suitable method when aiming to assess, validate or conceptually extend a theoretical framework (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005), as was the case for this study. The method involved both deductively and inductively developing a coding framework, which operationalized and illustrated the modes of the Seven-Eyed model, and line-by-line coding of all supervisors’ speech in all 40 transcriptions, aided by NVivo software. As the model is primarily concerned with the supervisor’s choice of focus, supervisees’ speech provided context but was not coded. On average, the supervisors spoke 43.7% of the time (range = 30.6–57.4%; SD = 12.3).

A coding framework was initially developed deductively by the second author by drawing definitions of the seven modes from theoretical descriptions in Hawkins and Shohet (Citation2012). The first two authors separately coded three transcripts to test the coding framework, following which differences in interpretation and application were discussed and resolved. Double-coding was done where relevant, but not in some instances (e.g., when mode 5 was coded, double-coding to modes 4 or 6 was not done as a focus on the supervisee and supervisor was already included in mode 5; this principle was also applied to mode 3 coding, with modes 1 and 4 then not double-coded). The coding framework was then inductively developed by the first two authors. This involved adding new specifications and illustrative quotes to the coding guidelines for each of the modes, derived from analysis of the study data, thus expanding the deductively developed framework. Inter-rater reliability (IRR) checks were then completed to ensure adequate consistency in coding. For each IRR check, four transcripts were separately coded by these authors (10% of the data set; Neuendorf, Citation2009) and compared using Cohen’s (Citation1960) kappa (k). The first two IRR checks achieved moderate agreement (combined k = .55 and .52; Landis & Koch, Citation1977), and substantial agreement was achieved on the third round (combined k = .70). After each IRR check, differences were discussed until consensus was reached, clarifications and adaptations were made to the coding framework, and further data-based examples were added (the coding framework is available on request from the first author). The remaining transcripts were then divided and independently coded.

In total, 10,238 meaning units of text were coded, a ‘meaning unit’ representing a complete, comprehensible expression (ranging from one word to several sentences). For each supervisor, both number of meaning units and percentage of their overall speech coded to each mode were calculated. Each method resulted in largely the same ordering of modes in terms of frequency of focus, so, as meaning units varied in length, percentage of supervisor speech is reported to more accurately reflect time supervisors spent focusing in each mode.

Results

Nearly all the supervisors’ speech (97.8%) was coded to at least one mode in the Seven-Eyed model, indicating that the model mapped well onto supervisory practice in a transdisciplinary community mental health service. An additional code, ‘Setting the focus,’ was added for speech that could not be coded to any of the modes (2.2%). This included practical considerations before a focus was taken, including listing/ordering agenda items and checking time.

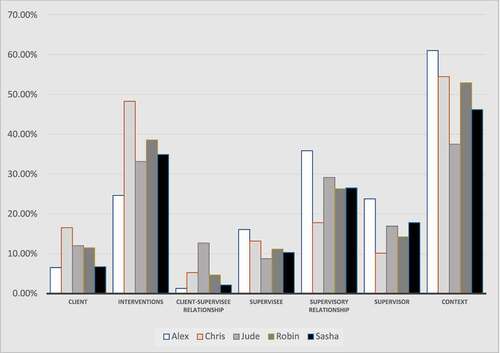

Mode 7 (the wider context) was a dominant focus for the supervisors (present in half of their speech), followed by mode 2 (interventions; in over one-third of their speech), and mode 5 (the supervisory relationship; in over one-quarter). All other modes were less often focused on by supervisors, including mode 6 (the supervisor; 17% of speech), mode 4 (the supervisee; 12%), mode 1 (the client: 11%), and lastly mode 3 (the client-supervisee relationship: 5%) (see, ). Analysis and illustrations of supervision practice in each mode follows, with more detailed presentation of material in mode 5 to illuminate some sensitive supervisory exchanges.

Figure 2. Percentage of each study supervisor’s speech coded to each mode of the Seven-Eyed model (N = 40 meetings; double-coding used).

Mode 1: focus on the client

A mode 1 focus was observed in only 10.7% of the supervisors’ speech on average and was the second least common mode. However, a short mode 1 query from the supervisor (e.g., Describe [the client] to me, tell me what he’s like [Chris: 6]) often led to supervisees describing their client at some length, with supervisors’ attentiveness evidenced by simple verbal encouragers (‘mmm,’ ‘yeah’), which were not coded in this study (note: to locate quotes in the study data set, the number beside the pseudonym represents the supervision meeting number).

In this mode, the supervisors most often focused on practical information gathering about clients, querying age, referral source, and presence of medical, psychiatric, or risk issues, as well as the client’s family situation (then also double-coded as mode 7.1). They also regularly offered formulations, less commonly asking supervisees for their own formulations:

How does [the client] manage when he can’t be in control of the situation … ? Often what they’re looking for is what, how can I make sure that I’m never being disempowered again. (Jude: 5)

A typically observed pattern was for supervisors to initially focus on gathering information about clients and their families, followed by offering formulations, and then swiftly moving into intervention planning (mode 2). It was rare for the supervisors to invite their supervisees to elaborate on how the client presented or behaved in session.

As well as individual therapy clients (as typically described in Hawkins & Shohet, Citation2012), the supervision work in this mode also focused on a variety of other clients, including client groups, the supervisees’ own supervisees/trainees, and community health or educational groups. This informed an explicit broadening of ‘clients’ in Hawkins & McMahon (Citation2020, p. 89) to “any individuals or groups who are receiving a service from the supervisee.”

Mode 2: focus on interventions

The supervisors engaged strongly with mode 2, their second most dominant mode, and observed in just over one third of their speech on average (35.9%). The supervisees frequently brought questions to supervision about what to do next with their clients. In response, the supervisors sometimes encouraged them to develop their own thoughts:

What would you wish for [the client] … if you could go absolutely wild and kind of give her anything in the world … the sky is the limit? (Alex: 2)

This enquiry-based approach was typically followed by direct guidance from the supervisors. This included proposing an intervention, offering a rationale, considering the desired impact, and modeling how the supervisee might go about the intervention, either recounting how they spoke to similar clients in the past or describing how they would speak to the current client:

I think I’d be kinda saying … ‘I wanted to let you know that people sometimes do this kinda stuff because of other things that might be going on for them. You mentioned a few times around how you don’t really talk about feelings or things like that at home.’ (Sasha: 2)

Role plays to rehearse planned interventions occurred in only two supervision meetings, both suggested by the supervisee rather than the supervisor. In addition, reviewing past interventions was rare:

Out of all the people on your list there, who would be your shining moment, who would you have thought, that went really, really well? (Chris: 1).

As well as focusing on client interventions, planning regarding inward and onward referrals and contact with families was also common (also involving the wider context, mode 7.2). Also, in line with a broader classification of ‘the client,’ supervisors offered guidance regarding interventions with community groups, and induction or supervision of new staff and students:

You could really spend time exploring with the student … their own views, their own values, their own biases, their own life experiences. (Robin: 5)

Mode 3: focus on the client-supervisee relationship

This mode was the least frequently focused on by the supervisors (5.2% of speech), and was not observed at all in five of the 40 sessions. When they did focus on mode 3, at times the supervisors simply invited their supervisees to reflect on their experience of the client: What is it like being in the room with [the client]? (Sasha: 5)

At other times, the supervisors actively named or wondered about a potential dynamic between the supervisee and client:

It sounds like she has really rolled up her sleeves and has decided I’m going to engage, and that’s evoked some sort of anxiety in you, are you going to meet her expectations? … Isn’t there a mirroring going on? She’s anxious and you’re anxious. (Robin: 1)

However, while the supervisors occasionally spoke in general terms about the importance of good therapeutic relationships to facilitate client development, they rarely invited exploration of specific client-supervisee dynamics.

As with the other modes, the supervisors also focused on exploring relationships with a wider spectrum of clients, including those between the supervisees and their own supervisees, with other professionals on community projects, and most commonly with clients’ parents: [Mum’s] kind of looking to us to kind of fix or to make things all alright. (Jude: 1)

Mode 4: focus on the supervisee

This mode was focused on in 11.9% of the supervisors’ speech on average (5th most common), most frequently attending to the supervisees’ general wellbeing and professional development and less frequently on their responses to their clients.

A focus on supervisees’ welfare was present in all sessions to some degree, and typically involved check-ins in relation to work, work-life balance, and general wellbeing: ‘In terms of your own welfare, just to say work aside, how are you?’ (Robin: 1). The supervisees’ experience of managing their caseload in the fast-paced, brief-intervention service was often queried, as well as experiences of organizational changes and policies, and relationships with colleagues. The supervisors encouraged their supervisees to actively attend to self-care and to access supports, often offering direct support:

Does your caseload feel manageable at the moment? … Keep an eye on it and flag it with me if I need to speak to admin. (Chris: 3)

The supervisors also regularly focused on their supervisees’ professional development. They frequently offered guidance about new areas of work and skills development, including advice about attending interviews, at times encouraging supervisees to highlight the value of their own professional discipline in the transdisciplinary organization:

In preparation for any senior interview you might have, I think this is really helpful to have clear in your mind as to, you know, what sets you out or what sets you apart from others … your passion, energy and skill set. (Sasha: 5)

When exploring supervisees’ responses to their clients, the supervisors at times focused on emotional responses when with clients (‘So you kind of went into that with a panicked feeling that something was wrong,’ Chris: 2), emotional responses while talking about a client in supervision (‘Has that touched on something for you?,’ Alex: 8), and when anticipating working with a client (‘How does the prospect of the intervention feel to you?,’ Sasha: 5). While often briefly checked in about, attention to the supervisees’ emotions was rarely in-depth and was not a dominant focus. Exploration of supervisees’ transference or countertransference in relation to clients was also rare, observed only once:

There’s a huge amount of warmth emanating from you … I’m just wondering does [the client] remind you of anyone from another area of your life? (Jude: 2).

Supervisors also rarely focused on exploring their supervisees’ beliefs or value systems in relation to their work:

Some people would believe that everything happens for a reason and I guess that is one of your beliefs isn’t it? … I wonder if that is a comforting thing? (Alex: 8)

Mode 5: focus on the supervisory relationship

This was the third most dominant area of focus for the supervisors, present in over one-quarter of their speech on average (27.1%). However, while exploring potential parallel processes is considered a key part of working within this mode, there was only one brief instance of the supervisor remarking on an apparent mirroring or paralleling of a client-supervisee dynamic in the supervisory relationship, which was not further explored: As you will have wanted to reassure [the client], I want to reassure you (Alex: 2).

The main work in this mode involved the supervisors attending to the quality of the supervisory alliance through checking that their supervisees’ needs were being met (Anything else that you wanted to get from today? Chris: 1) and regularly offered validating and supportive feedback. Often these were brief affirmations (“great,” well done”) and sometimes more specific: You collaborate so much with all the young people … which is a real strength. (Jude: 1), but constructive, developmental feedback was rare. Providing feedback was not clearly located in any mode in Hawkins and Shohet (Citation2012), but was coded as mode 5 in this study as it was judged to involve an immediate relational exchange (and was subsequently included in mode 5 in Hawkins & McMahon, Citation2020).

An aspect of mode 5 that was regularly observed in the study meetings (and also added into Hawkins & McMahon, Citation2020), involved review and planning of collaborative service management or delivery (e.g., community initiatives): Myself and [another manager], we’re very supportive and open for whatever this project needs (Sasha: 4).

At times the supervisors focused on reviewing the supervisory contract and discussing lines of responsibility and accountability within the supervisory relationship (also coded to mode 7.5, involving role/power issues in the organization):

I hear what you’re saying … you feel that you’re losing a bit of autonomy in terms of clinical decision making … Am I clear in saying that obviously if there’s any, like if there’s significant risk, it’ll always have to come to me. (Robin: 1)

Explicit conversations about the supervisory relationship or process were seldom observed in the study sessions. However, a few significant discussions occurred about the relevance of exploring supervisees’ emotional responses to their work. The conversations of two dyads are shared here at some length as they illustrate the sensitivity and complexity of this issue. Here, the supervisor had just asserted her belief in the value of personal therapy rather than supervision for exploring some issues (supervisor in italics; supervisee in plain text):

If I were to talk to you about [a regular tearfulness that the supervisee had just named] … I would be kind of going into things which are really quite private and personal … I wouldn’t want to disrupt our relationship … I would be happy to hear things if you wanted to bring them back in if you thought actually this would be helpful to talk about in relation to this person or how I am at work.Yeah, yeah, to keep it work-related. … I could sit here and do therapy with you but … I think it would be slightly abusive of my power I think, because you might say things to me because you trust me enough, things that you might not have wanted to have said … I’m kind of also, kind of aware of how vulnerable that might make you. (Alex & Ali: 2)

In a meeting three months later, the supervisee shared that a personal issue had been triggered for her when with a client earlier that day:

I was fine like, but obviously I’m an emotional wreck about it now (crying and laughing). … I have gotten a lot more overwhelmed than this, and you have as well (laughing). And I have as well (laughing)… Sorry, I suppose you just got the brunt of that emotion. Ah sure, no, no … there’s something about the humanity of it that I actually respect, you know, that you can be vulnerable … or just genuinely say this is what is happening. Yeah and Isuppose it is the same for me, that Ifeel safe in this space and so maybe that is why it has come out now. (Alex & Ali:8)

…

While still navigating some vulnerability and uncertainty, it seems that over time both the supervisor and supervisee had become more comfortable with sharing emotional reactions to their work. In another dyad, the supervisor was advocating more attention to the emotional impact of the work, her supervisee being more familiar with case management supervision:

I don’t feel like we, certainly don’t often go there … the emotional impact that an individual might have on you …

Do you mean like, if I’m sitting with young people, and how that’s impacting me? And … might be impacting on the intervention? … something they did reminded me of something and maybe that may give me a kind of a prejudice or something? … I just try and catch them. I don’t know …

I guess that’s what I feel supervision can be good for is when you do catch them, kinda reflecting on it afterwards and wondering … does that young person experience that with other people … [as a] micro example of how they are in the real world? …

I think it is really important … it can inform the practice too in a, kinda in a really helpful way, I just don’t know how to do it.

Sure, but are you interested?Yeah, I am, I am. It’s gonna like, it’ll be weird.

Sure … we might go there sometimes, we might not, and I guess maybe it feels a bit more comfortable to go there now … for the first 6, 12 months maybe I was very aware of not wanting you to be uncomfortable. (Sasha & Sam: 3)

This discussion clearly involved sensitive navigation to map out potential new territory for working at the personal-professional boundary in supervision. Also within mode 5, there was occasional attention to minor ruptures or misunderstandings in the supervision relationship. In the session following the above discussion, the supervisee shared her upset at believing that her supervisor judged her typical guidance-seeking to be easier than emotional exploration:

You made a comment about coming here looking for direction is very easy, and then started to talk about the other aspect [emotional processing], and I suppose just to kinda flag, that coming in here looking for direction is not easy … I was just like, kinda a bit seething over it [small laugh] … I got over it, but I thought I should say it.

No better person [small laugh]. Em, what my intention from that would have been is that, it’s maybe more straightforward, so not that it’s ever easy. (Sasha & Sam: 4)

Receiving the preliminary findings near the end of the study period also prompted explicit conversations about the supervisory work for three of the dyads: all three discussed the issue of exploring emotions in supervision, having seen some of the quoted material above (see also mode 7.6 below); and one dyad also reflected on ways of discussing interventions in supervision, the supervisor referring to a quoted example of an exploratory question:

One of them is … if I gave you a magic wand … how you would feel if I did talk like that?

Fine, yeah … it is just a way to try and open up my thinking about it. (Sasha & Sam: 8)

Mode 6: focus on the supervisor

Work within this mode involved 16.6% of the supervisors’ speech on average (4th most common mode). The supervisors most often brought in a focus on themselves through sharing stories or insights from their own experience, occasionally referencing books they had found helpful, and also sharing their own values or beliefs related to their work (these aspects of this mode were added in Hawkins & McMahon, Citation2020):

That was one of the best learnings for me, was getting right up and personal with my own life story and … make sense of it and be clear about my boundaries. (Robin: 5)

The supervisors also often brought in a brief focus on their own uncertainty before offering guidance: I wonder whether, I know there is no straightforward answer, but … (Chris: 5).

The supervisors also regularly shared their immediate personal reactions to their supervisees’ work: ‘fascinating’ (Jude: 1), ‘that must have been really heavy’ (Chris: 2), including how they were emotionally impacted:

My overwhelming [feeling] … is of such immense hurt and pain … it upsets me just the thought of [the client] and what she has been through, so I can just imagine that having an impact on your own session. (Sasha: 5)

Such sharing was usually simply acknowledged by the supervisees as fitting their experience, occasionally strongly so, as in Sam’s response to Sasha’s comment: “It was like being hit by a bulldozer.” However, there was no evidence of the supervisors further exploring their own reactions to shed light on the client or supervisory relationship, noted to be the main aim of work in this mode. The supervisors also rarely spoke about their imagined relationship with the client (described as mode 6a in the Seven-Eyed model), as this example shows (but was not elaborated on to develop potential insight): I really like the sound of him, [the client] is speaking to a part of me. (Robin: 3).

Mode 7: focus on the wider context

Mode 7 was the most dominant focus for supervisors (present in half of the supervisors’ speech on average; 50.4%). This mode was always double-coded as it represented the wider context of one or more of the other six modes, supervisors most often referring to the organizational context of interventions (mode 7.2) and of the supervisory relationship (mode 7.5). Overall, the high level of attention to wider contexts fit with the brief-intervention nature of the service and its young client group, which necessitated frequent liaison work.

7.1 The client context (14% of mode 7 codes)

Regular attention was given to the clients’ families, followed by exploring the reason for referral, clients’ past experience of help-seeking, and their current interests and resources. Diversity issues were also focused on at times:

Parents worry a lot when their young person is other than the typical in society … they may feel like their child is going to be very unsafe, or rejected in some way. (Jude: 7)

7.2 The professional/organizational context of the supervisee’s interventions (24.3%)

A strong focus was on how the brief-intervention nature of the organization’s work influenced interventions, involving liaison and planning with families and other services. Occasionally, the approach that different disciplines took to interventions was also discussed.

7.3 The context of the client-supervisee relationship (1.4%)

As with mode 3, this submode was rare, mostly focusing on how the client was referred, clients’ and family members’ expectations, and their impact on the client-supervisee relationship:

So, it’s easier to kind of come into sessions … than to have an argument with mum about not going, and mum sounds quite invested in her going. (Jude: 1)

7.4 The wider world of the supervisee (17.5%)

At times, supervisees’ personal circumstances were focused on (e.g., family responsibilities), but most frequently opportunities for supervisees’ professional development were discussed:

If you have experience of supervising a student, in terms of your career trajectory that can only be a good thing. (Robin: 1)

7.5 The context of the supervisory relationship (24.8%)

Given their responsibility as seniors in the organization, most dominant here was supervisory review of supervisees’ management of risk issues, caseloads, and case notes. This also included discussions about roles and responsibilities in collaborative work on service projects.

7.6 The context of the supervisor (18%)

Sometimes, the supervisors referred to their experience in other contexts in relation to arising issues in supervision. For instance, in response to her supervisee’s self-questioning about exploring her emotional process in supervision after seeing the study’s preliminary findings (“Was I using supervision as a more therapy? … I didn’t feel it at the time.” Ali, 10), the supervisor shares her own self-questioning in relation to this personal-professional boundary:

Am I overstepping the mark here? … On balance I wouldn’t have thought [so] … because I explore those things in my own supervision. (Alex: 10)

Discussion

The Seven-Eyed model was found to be a meaningful framework for analyzing supervision practice over a six-month period in an Irish transdisciplinary primary care mental health setting. This study offers some empirical support for this popular supervision model, affirming its value in conceptualizing supervisory work. The practice-based evidence from this study also contributed valuable elaborations of some of the modes (subsequently included in the updated book depicting the model; see, Hawkins & McMahon, Citation2020). The elaborations included a broader definition of the ‘client’ in mode 1; elaboration of mode 4 to include more attention to supervisees’ professional development; expansion of mode 5 to include the relational exchange in offering feedback, management of boundaries/dual roles, and negotiation of collaborative work; and expansion of mode 6 to include supervisors’ sharing of their values, beliefs, and experiences.

Results indicated supervisors gave most time and attention to the wider context of the work (mode 7) and to intervention planning (mode 2), and least attention to the client (mode 1) and the client-supervisee relationship (mode 3). Attention to the wider context mostly focused on liaison work with families and other services, which was fitting given the young client group and the brief-intervention nature of the service. This strong mode 7 focus also included regular attention to managerial concerns within the supervisory relationship, such as supervisees’ management of caseloads, even though the supervisees also had separate line management supervision. In previous research (e.g., McMahon & Errity, Citation2015), it has been found that supervisors holding a dual managerial/clinical supervision role can impact supervisees’ feelings of safety and it is possible that this may have contributed to the limited attention given to some modes in this study, as further discussed below.

Within mode 1, rather than holding a strong focus on the client’s presentation in session, as recommended within the Seven-Eyed model, the supervisors primarily focused on formulation, typically quickly followed by intervention planning (mode 2). Thus, the supervisors generally were more directive than facilitative. Again, given the brief-intervention nature of the organization, a focus on efficient interpretation and decision-making was understandable. However, taking time to explore how clients presented and related could help to inform more attuned and confident interventions for supervisees by heightening awareness of “the actuality of the experience of being with the client prior to doing” (Hawkins & Shohet, Citation2012, p. 90).

It was also noteworthy that the supervisors rarely facilitated their supervisees to reflect on their own ideas for interventions or to rehearse intervention plans. This finding indicates the value of discussing supervision goals, including whether supervisees’ experiential learning is a shared objective. Such experiential work, including role plays and review of supervisees’ live or recorded practice, may be important given that live, experiential learning and review of recordings is associated with maintaining and developing practitioner competency (e.g., Alfonsson et al., Citation2020; Bearman et al., Citation2017).

Given the well-established importance of the therapeutic alliance for good client outcomes (Flückiger et al., Citation2018), the scarce attention to client-supervisee relationships (mode 3) in this study was also notable. In addition, work was rarely done within modes 4 to 6 to enhance understanding of the supervisees’ therapeutic relationships. This could have included exploration of the supervisees’ emotional responses to their client work in more depth (mode 4), attention to potential parallel processes between the supervisory and client relationships (mode 5), and exploration of supervisors’ responses to supervisees’ clients to shed light on client dynamics (mode 6). Exploring supervisees’ emotional responses to their work is not only valuable for processing the impact of working with clients in distress, but is also supported by evidence that working through therapists’ countertransference reactions is related to good client outcomes (Hayes et al., Citation2018). Hawkins and Shohet (Citation2012) asserted that modes 3 to 6 are more commonly used as supervisees gain experience and are better able to attend to relational processes in their work. The under-representation of mode 3 and of the dynamic, relational aspects of modes 4 to 6 in the supervision of the early-career practitioners in this study offered some evidence for this. However, other factors were also likely to be operative here. For example, dual roles in these workplace supervisory relationships may have affected safety to explore relational dynamics, and their transdisciplinary nature was likely to have led to differing expectations, with some disciplines having more experience of attending to relational processes in supervision than others. These ‘relational’ modes were also less commonly identified in Lawrence’s (Citation2019) study of coaching supervision, indicating that working with relational dynamics may be less common in some supervision contexts and for some disciplines, and may need focused training and consultative supervision to develop supervisors’ skills and competence in this area.

Although the relational elements of mode 4 were not well attended to, regular work was observed within this mode to review and support the supervisees’ professional development plans. In a transdisciplinary service, this work could be developed further to focus more on supervisees’ theories, values, and beliefs from within their own professional discipline (see, also Davys et al., Citation2021), as this was seldom attended to in the supervision meetings reviewed for this study.

Within mode 5, the supervisors regularly offered validating feedback but constructive or developmental feedback was rare, indicating that more may need to have been done to balance attention to formative, normative, and restorative functions of supervision (Proctor, Citation1988). The implications of this finding are that explicit discussion and regular review of the goals of clinical supervision may be necessary for workplace supervisory dyads, and when developing organizational policy for workplace supervision. Previous researchers also suggested that supervisors may need specific training to develop skills and confidence in providing feedback (Borders et al., Citation2017).

Discussions were seldom had about the supervisory work or relationship, which is of concern given the well-evidenced importance of the quality of the supervision relationship (Watkins, Citation2014). Such discussions may be particularly important in transdisciplinary supervision, given the likely differences in experiences and expectations noted above. Calvert et al. (Citation2016) emphasized the value of developing competence in metacommunication during supervision and exploring here-and-now relational dynamics, which can foster supervisees’ competence in metacommunication in their therapeutic relationships. However, illustrative dialogs in this study regarding working with emotions at the personal-professional boundary also highlighted the sensitivity of this work, requiring close attentiveness to supervisees’ experience of vulnerability, power, and safety (see McMahon, Citation2014, Citation2020).

Strengths, limitations, and directions for further research

This is the first published observational study analyzing the applicability of the Seven-Eyed model to supervision practice, offering some empirical validation for the model. The study also offers a rare window into naturalistic supervision practice, with detailed examples of sensitive discussions about the personal-professional boundary in supervision. As a longitudinal study, a substantial data set was involved and the impact of recording is likely to have been minimized (see, Marshall et al., Citation2001). However, changes in the relative areas of focus for each supervisory dyad over time were not analyzed, and this would be beneficial in future studies. It would be particularly valuable if individualized feedback from observation of clinical practice was included and its subsequent impact analyzed (as in Milne et al., Citation2013).

Significant time was given to refining a coding framework for the Seven-Eyed model and to gaining consistency in coding decisions through repeated IRR checks and discussions, enhancing rigor and validity. However, other researchers may have made different coding decisions, some subjectivity remaining when judging supervisors’ focus (e.g., depending on levels of sensitivity to issues of culture, diversity, and power when double-coding for mode 7).

Furthermore, this study only analyzed the supervisors’ speech, as the Seven-Eyed model offers a framework for considering the supervisor’s choice of focus. However, supervision is a co-created endeavor and further studies could incorporate analysis of the supervisee’s choices (for instance, a mode 1 focus was higher in the supervisees’ speech in this study).

This study is also limited to a particular cultural and work context, and to a small study sample. More observational research in other contexts is needed to provide further practice-based evidence for the Seven-Eyed model. In addition, it would be valuable to carry out an observational study of the model’s application to group supervision. Findings also point to the importance of further research to explore what facilitates and impedes the use of experiential learning processes in supervision, such as role-plays, review of recordings, and providing regular, developmental feedback; to explore experiences of working with relational dynamics in supervision, including working at the personal-professional boundary; and to investigate experiences of transdisciplinary supervision, particularly in work contexts involving dual roles.

Conclusions and implications

This study offered some empirical evidence for the construct validity of the Seven-Eyed model of supervision, led to the expansion and elaboration of some of the model’s modes in Hawkins and McMahon (Citation2020), and offered illustrations of practice in an Irish transdisciplinary, youth mental health work context. This research also showed how analyzing practice according to the Seven-Eyed model can identify areas of supervisory work that may need development, as findings highlighted some important issues for consideration for supervisors, and supervisor trainers and consultants.

Supervision researchers are still at an early developmental stage in investigating and exploring what is involved in the important but complex, multi-layered relational work of supervising practice. This study was the result of a collaboration between an academic researcher/trainer and the clinical director of a mental health service. Both had a strong commitment to practice-based research, as did the study participants. Further naturalistic, observational studies are needed through practitioner-researcher collaborations in order to continue to build our understanding of the detailed intricacies, challenges, and rewards of supervisory practice.

Acknowledgments

With many thanks to the study’s supervisory dyads who generously shared their work, and to Sarah Moorhead, Rachael McDonnell Murray and Shannon Gray for their painstaking transcription work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Aisling McMahon

Aisling McMahon is a clinical psychologist, integrative psychotherapist and Assistant Professor in Dublin City University, Ireland, where she teaches on postgraduate psychotherapy and clinical supervision training programmes. With Peter Hawkins, Aisling is coauthor of the 5th ed. of Supervision in the Helping Professions. Her research interests are clinical supervision and practitioner development from training to retirement.

Ciaran Jennings

Ciaran Jennings is a research assistant at Dublin City University, Ireland. He also works as a counseling psychologist and clinical supervisor in private practice. His research interests include clinical supervision, emotion focused therapy, shame, homelessness, harm reduction, and therapeutic recreation.

Gillian O’Brien

Gillian O’Brien is a clinical psychologist and Clinical Director with Jigsaw, The National Centre for Youth Mental Health, Ireland.

References

- Alfonsson, S., Lundgren, T., & Andersson, G. (2020). Clinical supervision in cognitive behavior therapy improves therapists’ competence: A single-case experimental pilot study. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 49(5), 425–438. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2020.1737571

- Bambling, M., King, R., Raue, P., Schweitzer, R., & Lambert, W. (2006). Clinical supervision: Its influence on client-rated working alliance and client symptom reduction in the brief treatment of major depression. Psychotherapy Research, 16(3), 317–331. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300500268524

- Bearman, S., Schneiderman, R., & Zoloth, E. (2017). Building an evidence base for effective supervision practices: An analogue experiment of supervision to increase EBT fidelity. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(2), 293–307. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0723-8

- Bernard, J., & Goodyear, R. (2019). Fundamentals of clinical supervision (6th ed.). Pearson.

- Bernard, J., & Luke, M. (2015). A content analysis of 10 years of clinical supervision articles in counseling. Counselor Education and Supervision, 54(4), 242–257. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12024

- Borders, L. D., Welfare, L. E., Sackett, C. R., & Cashwell, C. (2017). New supervisors’ struggles and successes with corrective feedback. Counselor Education and Supervision, 56(3), 208–224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12073

- Calvert, F. L., Crowe, T. P., & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2016). Dialogical reflexivity in supervision: An experiential learning process for enhancing reflective and relational competencies. The Clinical Supervisor, 35(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2015.1135840

- Carroll, M. (2020). Foreword. In P. Hawkins & A. McMahon (Eds.), Supervision in the helping professions (5th ed., pp. xiii–xiv). McGraw-Hill Open University Press.

- Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104

- Creaner, M., & Timulak, L. (2016). Clinical supervision and counseling psychology in the Republic of Ireland. The Clinical Supervisor, 35(2), 192–209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2016.1218812

- Davys, A., Fouché, C., & Beddoe, L. (2021). Mapping effective interprofessional supervision practice. The Clinical Supervisor, 40(2), 179–199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2021.1929639

- Dawson, M., Phillips, B., & Leggat, S. (2013). Clinical supervision for allied health professionals: A systematic review. Journal of Allied Health, 42(2), 65–73.

- Dunsmuir, S., & Leadbetter, J. (2010). Professional supervision: Guidelines for practice for educational psychologists. British Psychological Society.

- Ellis, M. V., Creaner, M., Hutman, H., & Timulak, L. (2015). A comparative study of clinical supervision in the Republic of Ireland and the United States. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(4), 621–631. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000110

- Fitch, J. C., Pistole, M. C., & Gunn, J. E. (2010). The bonds of development: An attachment-caregiving model of supervision. The Clinical Supervisor, 29(1), 20–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07325221003730319

- Flückiger, C., Del Re, A. C., Wampold, B. E., & Horvath, A. O. (2018). The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 316–340. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pst0000172

- Goodyear, R. K., Borders, L. D., Chang, C. Y., Guiffrida, D. A., Hutman, H., Kemer, G., Watkins, C. E., & White, E. (2016). Prioritizing questions and methods for an international and interdisciplinary supervision research agenda: Suggestions by eight scholars. The Clinical Supervisor, 35(1), 117–154. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2016.1153991

- Hawkins, P., & McMahon, A. (2020). Supervision in the helping professions (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill Open University Press.

- Hawkins, P., & Shohet, R. (2012). Supervision in the helping professions (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill Open University Press.

- Hayes, J. A., Gelso, C. J., Goldberd, S., & Kivlighan, D. M. (2018). Countertransference management and effective psychotherapy: Meta-analytic findings. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 496–507. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000189

- Health Service Executive (2015). HSE/public health sector guidance document on supervision for health and social care professionals; improving performance and supporting employees. https://www.hse.ie/eng/staff/resources/hr-circulars/circ00215.pdf

- Henderson, A., & O’Riordan, S. (2020). Resourcing the supervisory relationship during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Coaching Psychology, 1(3), 1–10. https://ijcp.nationalwellbeingservice.com/volumes/volume-1-2020/volume-1-article-3/

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Joseph, S. (2017). SAFE TO PRACTISE: A new tool for business coaching supervision. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 10(2), 115–124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17521882.2016.1266003

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310

- Lawrence, P. (2019). What happens in group supervision? Exploring current practice in Australia. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 17(2), 138–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24384/v0d6-2380

- Marshall, R. D., Spitzer, R. L., Vaughan, S. C., Vaughan, R., Mellman, L. A., MacKinnon, R. A., & Roose, S. P. (2001). Assessing the subjective experience of being a participant in psychiatric research. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(2), 319–321. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.319

- Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(2). Art. 20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.2.1089.

- McLaughlin, A., Casey, B., & McMahon, A. (2019). Planning and implementing group supervision: A case study from homeless social care practice. Journal of Social Work Practice, 33(3), 281–295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2018.1500455

- McMahon, A., & Errity, D. (2015). From new vistas to life lines: Psychologists’ satisfaction with supervision and confidence in supervising. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 21(3), 264–275. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1835

- McMahon, A. (2014). Four guiding principles for the supervisory relationship. Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 15(3), 333–346. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2014.900010

- McMahon, A. (2020). Five reflective touchstones to foster supervisor humility. The Clinical Supervisor, 39(2), 158–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2020.1827332

- Milne, D., Reiser, R., & Cliffe, T. (2013). An N = 1 evaluation of enhanced CBT supervision. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 41(2), 210–220. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465812000434

- Milne, D., & Reiser, R. (2017). A manual for evidence-based CBT supervision. Wiley.

- Neuendorf, K. (2009). Reliability for content analysis. In A. Jordan, D. Kunkel, J. Manganello, & M. Fishbeing (Eds.), Media messages and public health: A decisions approach to content analysis (pp. 67–87). Routledge.

- Page, S., & Wosket, V. (2015). Supervising the counsellor and psychotherapist: A cyclical model (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Proctor, B. (1988). Supervision: A co-operative exercise in accountability. In M. Marken & M. Payne (Eds.), Enabling and ensuring (pp. 21–23). National Youth Bureau and Council for Education and Training in Youth and Community Work.

- Regan, P. (2012). Reflective insights on group clinical supervision: Understanding transference in the nursing context. Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 13(5), 679–691. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2012.697880

- Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. Sage.

- Schwalbe, C. S., Oh, H. Y., & Zweben, A. (2014). Sustaining motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of training studies. Addiction, 109(8), 1287–1294. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12558

- Simpson-Southward, C., Waller, G., & Hardy, G. E. (2017). How do we know what makes for “best practice” in clinical supervision for psychological therapists? A content analysis of supervisory models and approaches. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 24(6), 1228–1245. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2084

- Stoltenberg, C., & McNeill, B. (2010). IDM supervision: An integrative developmental model for supervising counselors and therapists (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Townend, M., Iannetta, L., & Freeston, M. H. (2002). Clinical supervision in practice: A survey of UK cognitive behavioural therapists accredited by the BABCP. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 30(4), 485–500. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465802004095

- Wallbank, S. (2013). Maintaining professional resilience through group restorative supervision. Community Practitioner, 86(8), 26–28.

- Watkins, C. E. (2011). Does psychotherapy supervision contribute to patient outcomes? Considering thirty years of research. The Clinical Supervisor, 30(2), 235–256. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2011.619417

- Watkins, C. E. (2014). The supervisory alliance: A half century of theory, practice, and research in critical perspective. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 68(1), 19–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2014.68.1.19

- Watkins, C. E. (2020). What do clinical supervision research reviews tell us? Surveying the last 25 years. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 20(2), 190–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12287

- Wheeler, S., & Richards, K. (2007). The impact of clinical supervision on counselors and therapists, their practice, and their clients: A systematic review of the literature. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 7(1), 54–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140601185274

- Whipple, J., Hoyt, T., Rousmaniere, T., Swift, J., Pedersen, T., & Worthen, V. (2020). Supervisor variance in psychotherapy outcome in routine practice: A replication. Sage Open, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019899047

- Wilson, H. M. N., Davies, J. S., & Weatherhead, S. (2016). Trainee therapists’ experiences of supervision during training: A meta-synthesis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 23(4), 340–351. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1957