Abstract

When trying to understand why children's rights are being violated, legal pluralism has been used as a theoretical framework for the empirical study of children's rights by relatively few researchers. In most of these cases, it is unclear why a certain social phenomenon is categorized as “law,” and research on smaller legal orders related to children, such as the school and the household, is lacking. My hypothesis is that for children, law is mostly what their parents or their teachers tell them. Therefore, this law, that we find when looking at law through children's eyes, has to be recognized as part of a complete picture of law influencing the protection and/or violation of children's rights. In the current article, I present an alternative legal pluralist theoretical and methodological framework for the research of children's rights. To go beyond mere theory, I will show how I applied the theory to a case study on the child's right to education in the Central African Republic (CAR) and present its results.

1. Introduction

Although we are close to celebrating the 30th anniversary of the 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (hereafter CRC), children’s rights are grossly violated on a daily basis and on a global scale. When trying to understand why children’s rights are being so grossly violated, researchers often engage in analyzing international conventions and comparing these to national law, court proceedings and de facto reality. This kind of comparison and measurement is also the usual approach of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. However, understanding law as formal written law that addresses children seems a too limited perspective. My hypothesis is that for children, law is not necessarily what is stated in state or international legal codes, of which they are generally unaware, rather it is what their parents or their teachers tell them.1 Therefore, this law, that we find when looking at law through children’s eyes, has to be recognized as part of a complete picture of law influencing the protection and/or violation of children’s rights.2

Take for example the situation of domestic sexual abuse of children. This practice clearly goes against both national and international law. So why do children sometimes “agree” to have sex with their caretaker, especially when they detest this practice? Why do they not just go to the police, or generally ask for help (Kitzinger Citation1997, 168, 175)? I suggest that when we look at law from the child’s perspective, we can understand some of these instances as the child in fact complying with the law. The child complies with the law of the abusive father, who rules over the child: “you are not allowed to talk about our little game to anyone”. If children’s rights are analyzed in this way, if we truly listen to children, we might be able to understand much better what rights and laws are for children, and consequently, why their formal rights are being violated (and perhaps use this knowledge for social change). To this end, a far-reaching legal pluralist theoretical framework is necessary.3

Legal pluralism has been used as a theoretical framework for the empirical study of children’s rights by a handful of researchers.4 In these cases, the legal orders studied in addition to international, regional and state legal orders, have mostly been the religious legal order, and/or researchers have focused on the broader category of “customary law” or “indigenous law”. Although very interesting work has been done, I think there are two main issues with the current state of legal pluralist study of children’s rights: first, sometimes a definition of “law” and/or “legal order” is lacking, or if a definition is given, it is unclear what exactly, if found in empirical data, would count as “law” and/or “legal order”. Authors often shy away from making the distinction between “legal order” and “(other) normative order”, and don’t explain why they consider certain empirical data “customary law”, “social rule”, etc.5 Consequently, it is unclear why a certain empirical phenomenon would or would not be considered legal. As Tamanaha (Citation2000, 299) writes: “without agreement on fundamental concepts that allow for the careful delineation of social phenomena, there can be no cumulative observation and data gathering”. Second, children’s rights researchers have a tendency to group all non- international/state law under broad categories such as “customary law”, “local norms” or “indigenous norms” (Corradi and Desmet Citation2015b, 3). A further research on smaller legal orders often relevant to children (the household, the gang, the school, the classroom, etc.) is lacking.

Some authors may therefore decide to move away from “legal pluralism” and simply present a broader “norm pluralism” (Simon Citation2015, 177) (which, of course, comes with its own theoretical and methodological challenges). However, like I said, for children’s rights research I do see a value in researching specifically the pluralism of legal orders in society. In the current article I will present an alternative legal pluralist theoretical and methodological framework for the research of children’s rights. I agree with Tamanaha (Citation2000, 303) that “the validity of [the] approach must be measured by its value in illuminating the situation of law in society.” To go beyond mere theory, I will show how I applied the theory to a case study on the child’s right to education in the Central African Republic (CAR) and present its results. In sum, this article will serve three goals: first, to present an alternative legal pluralist theoretical and methodological framework for the research of children’s rights; second, to illustrate the application of the above-mentioned framework in a concrete case study, namely the child’s right to education in the Central African Republic (CAR); third, to present the results of the above-mentioned case study.

I will start by presenting the theoretical framework for researching children’s rights in different legal orders and an accompanying methodology (section 2). Second, I will introduce the case study (section 3). Third, I will present the results of the case study, discussing possible legal orders surrounding children’s education in CAR (section 4). I will end the article with a conclusion (section 5).

2. A theoretical and methodological framework for researching children’s rights in different legal orders

The theoretical framework starts from the basic assumption that law is a social fact; laws are created by persons, they do not exist objectively and externally to human understanding. Laws exist only where there is a relation between people, a specific sort of relation that takes on a certain character, so that we define it as legal. In addition, to clearly delineate what would be considered legal and not legal, I propose that each social order, to be classified as a legal order, has to possess the following four characteristics:

First, the sovereign (or legislator);6 the person, or group of people, that the (legal) community has authorized to make law over them. The community allows the sovereign to be the author of (part of) their actions,7 thereby giving up part of their individual freedom, bestowing legal power upon the sovereign. The sovereign is an artificial person.8 Second, the basic norm: the norm that presupposes that one ought to behave such as has been commanded by the sovereign, or that the sovereign is the legitimate sovereign (Kelsen Citation1949/2007, 115–18; Kelsen 1967/2009, 8–9; Hart 1961/Citation2012, 100). Third, the legal community: the person, or a group of people, to whom the laws of the legal order apply. They recognize the basic norm authorizing the sovereign to create laws. Fourth, laws: a law is a valid legal norm, which is valid within a legal order, by virtue of the fact that it has been created by a legitimate sovereign. Anyone who acts against the law (commits an illegal act) is liable to legal consequences posed within the same legal order. Note that a norm is a prescriptive statement, a rule by which a certain behavior is commanded, permitted or authorized, and laws can be written or unwritten, public or non-public.9

The legal order can then be defined as the legal community, sovereign and its laws taken together. Since law is a social fact, the existence of all of these elements, and ultimately the existence of any legal order, depends on the subjective belief of people. For there to be law, there has to be a legal community that recognizes the legal power of a sovereign, and a sovereign who in fact makes law over this community. I think this point is made quite clear by Haugaard’s (Citation2008, 122) example;

what distinguishes the actual Napoleon from the “napoleons” who are found in psychiatric institutions is not internal to them but the fact the former (unlike the latter) had a substantial ring of reference which validates his power.

Following this theoretical framework, five characteristics of the legal order have been distinguished that must have empirical (psychological) reality for there to be an actual legal order. These elements are: (a) the legal community, (b) the sovereign, (c) laws and the basic norm as objects of subjective belief, (d) the possibility of imposing legal consequences through legal power, (e) law (valid legal norms created by the sovereign). Clearly, these elements have to be seen in connection to each other and can only be separated artificially. In practice, they are interdependent; for example, the possibility of legal consequences prescribed by the sovereign (d) is in great part dependent on the subjective belief of the legal community in the basic norm of the legal order (a + c). It does not, however, mean that every law has to be known by the whole legal community for it to be law. It is sufficient for the legal community to generally believe in the basic norm that installs the sovereign, and for this sovereign to declare the law – even if only a limited amount of the members of the legal community know about this law.

2.1. Methodology

After concluding that what is law ultimately depends on the relevant community, that understands a certain social fact to have a legal meaning,10 one can now easily understand Ehrlich (1913/Citation1975, 498) who says that to find law, “there is no other means but this, to open one’s eyes, to inform oneself by observing life attentively, to ask people, and note down their replies”. But then how should we do this?

According to Weber (Citation1949, 178, 311), to understand human social action (of which legal action is a subcategory) by means of qualitative research, one has to find “psychological and intellectual phenomena” (74), to collect these “various very disparate individual types of cultural elements” (89), looking for people’s “purposes”; their “conception[s] of an effect which becomes a cause of an action [author’s italics]” (83). Next, the researcher has to bring order into this “chaos of existential judgments about countless individual events” by relating it to the framework of cultural values “with which we approach reality” (78) (in this case, the characteristics described above form a set of “ideal types” with which we approach reality). We can use the constructed ideal type as “a heuristic device for the comparison of the ideal type and the facts” (102).

In practice, this means that a researcher who wants to find law has to engage in qualitative research with possible legal communities and possible sovereigns, in addition to literature study and the study of formal legal documents, to find which laws relate to children’s rights. To begin, one has to identify potential legal orders,11 in relation to the child’s right and the relevant society that are the subject of the research. As mentioned before, this might be, among many others: the household, the village, the school, the classroom, the workplace, the tribe, the religious order, the state, etc. The researcher will then engage in qualitative research conversations with members of the community and/or the sovereign(s) of all these potential legal orders. In the conversations, the researcher will ask people whether they concern themselves the addressees of a certain law (or rule), why they feel that they are addressed by that law, what the law says exactly, who created it and what will happen if they transgress the law. In these conversations, a researcher is particularly interested in a person’s sense of obligation that follows from authority. Indications of participants’ “psychological phenomena” that indicate (lack of) law, can be remarks such as “I did that because I had to”, “I have to do it, because my father says so”, “I did it in secret, because it is illegal”, or “No one tells me what to do”.

3. Research on the child’s right to education in the CAR

The Central African Republic (CAR), a former French colony, is a true competitor for the label “worst country in the world”. The country has been rated as having the lowest human development (UNDP Citation2016), as being both the poorest (Gregson Citation2017) and the unhappiest country in the world (Helliwel, Layard, and Sachs Citation2017). In terms of children’s rights, the country has been ranked the worst country regarding protection of children’s rights (KidsRights Foundation Citation2017), having the lowest opportunities for youth development (The Commonwealth Citation2016) and having the lowest education achievement in the world (UNDP Citation2016). Peace times are rare in the CAR, which has been involved in an on-and-off war for at least twenty years now. In August 2017, the UN Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs stated that “early signs of a genocide are there” (O’Brian Citation2017).

In terms of law and legal orders in the CAR, research shows a general lack of law and political organization. On the level of the national legal order, the CAR is generally known as a “failed state” or “phantom state” (International Crisis Group Citation2007; Carayannis and Lombard Citation2015, 3; Smith Citation2015, 17) meaning that even though the CAR has a government and a more or less defined territory, government governance of the territory is often minimal or absent. This does not seem to be a recent development. As de Vries and Glawion (Citation2015, 14) write: “From colonial times to today, rulers have […] never controlled their sovereign territory”.12 No CAR government to date has established an independent judiciary (Smith Citation2015, 38). Law enforcement officers are equally distrusted by the population, because they are perceived as not serving justice but rather engaging in corruption and extortion.13 The CAR government hardly operates as legislature (Marchal Citation2015, 70; Bierschenk and de Sardan Citation1997, 467). Some argue that, in line with general concessionary politics, even the task of legislating is outsourced to external actors.14 As Ngoumbango Kohetto (Citation2013, 211) writes:

in fact, the laws enacted in the “metropole” correspond to the needs and realities of Western society and are generally incompatible with the situation in the Central African Republic […] the jurisdictions are perceived as foreign. The law […] is like an external instrument.15

Or, in the words of Smith (Citation2015, 117):

CAR’s ruling elite has transacted the country’s sovereignty wholesale and no longer piecemeal […] a country which has descended into chaos by dint of outsourcing its state attributes in the first place is digging itself deeper into a hole with the altruistic help of the outside world.

International law does not seem to mean much in the country either, in spite of the physical presence of foreign peacekeeping forces, which can be seen from the fact that even the perpetrators of the worst violations of human rights, such as the mass killing of civilians,16 do currently not suffer any legal consequences of their actions (although perhaps the CAR special court might change this situation at some point).17

On a local level, conflict resolution is traditionally the domain of the village chief. However, it seems that this has never been much of a legal arrangement, but rather the chief has been sought out for his/her wisdom, to end conflict by giving advice to opposite parties on how to reconcile (Ngoumbango Kohetto Citation2013, 427; Bierschenk and de Sardan Citation1997, 444; Bigo Citation1988, 19). As Bigo (Citation1988, 19, 21–22) writes:

The chief does not command, he has the function of a mediator, and uses his prestige to convince the opposite parties of his words and wisdom […] the role of the chief is to be a mediator, a creator of peace […] he has no decisional power […] he has no authority.

It is with this in mind that I decided to travel to the CAR, to do research on the child’s right to education. I felt that in a context where there seems to be so little hope, education might be one of the best options for social change. My question for this case study was: “what laws, from what legal orders, have an influence on the child’s right to education in the CAR?”. Before arrival, I made a table of possible legal orders surrounding the child’s right to education in the CAR ():18

Table 1. Overview of possible legal orders related to the child's right to education in the CAR.

For the design of the qualitative interviews, I initially chose a very loose and unstructured design, basically posing only one question that the researcher and respondent could try and answer together, namely: “what is the meaning of the child’s right to education in the Central African Republic?” I chose this initial approach for three reasons; first, as I was looking for personal meaning-giving, I only wanted to decide on the main question, or subject, of the conversation, leaving as much room as possible for the respondent to freely express his/her personal beliefs and motivations.19 Second, I wanted to create as much equality between participant and researcher as possible, believing this would result in more reliable information.20 Third, although the main question of the case study was “what laws, from what legal orders, have an influence on the child’s right to education in the CAR?” (see above), this question seemed too complicated to discuss with respondents. Therefore, I simplified this to “what is the meaning of the child’s right to education in the CAR?”. I did explain to each participant that I was looking for relevant laws/rules related to the child’s right to education, and during the research conversation I kept a focus on identifying law and legal orders, meaning that I was at least in part looking for rules, consequences, authority, decisions and decision-makers related to education.

In doing interviews I combined the didactics of inquiry-based science instruction, a didactic practice where children (in this case, respondents in general) actively participate in the inquiry into a research question (Minner et al. Citation2010; Cremin et al. Citation2015; Keys and Bryan Citation2001), with the interviewing technique of the Socratic dialogue (Lipman, Sharp, and Oscanyan Citation1980; Vansielegem and Kennedy 2011), whereby the researcher uses dialectic reasoning, researching a certain main question together with the respondent. The most interesting of this approach is that it goes beyond mere question-and-answer, exploring deeper the convictions, ideas, experiences, etc. of the respondent (see also Areeda (Citation1996, 912)).

Based upon some first initial interviews with children, parents and NGO employees working on education in the CAR, I defined four main groups of interest:

Children (age 5–20)

Adults with parental responsibility: parents, other family members (grandparents, aunts/uncles, older siblings), tuteurs (an adult who has parental responsibility over a child, either a family member or an adoptive parent)21

Adults deciding in schools: (a) teachers, (b) school directors

Adults deciding over education: (a) education inspectors, (b) politicians, (c) NGO employees working on education, (d) members of the APE (“Association des Parents d’Elèves”, an organization of parents of students), (e) religious leaders

Over 3 months, I conducted research interviews with the following participants ():

Table 2. Overview of participants research interviews.

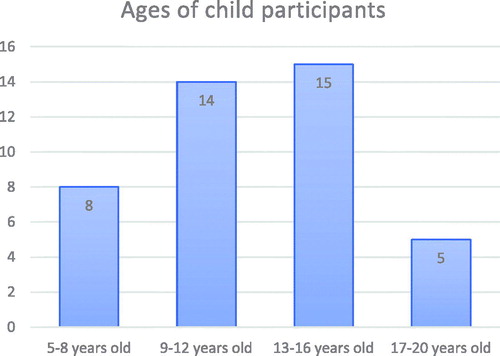

Insofar as they were willing or able to tell their age, the ages of the child participants were (see Chart 1):

Interviews usually took between 30 and 50 minutes, with some exceptions of >2 hour conversations. Interview data was supplemented by several recorded observations (among those lengthy observations in 10 different classrooms) and literature research.22

Although sometimes hindered by the security situation of the country,23 I travelled around as much as possible, finally having interviewed people in 10 different places of residency. These places were spread all over the country and included villages, towns and bigger cities, rural and urban areas, conflict zones and relatively safe areas.

4. Results: looking for legal orders surrounding the child’s right to education in CAR

Based on what I found in the field, the actual legal orders and the law found on education in the CAR24 can be schematized as follows (see ):

Table 3. Legal orders found, in their relation to law on education in the CAR.

4.1. International and regional legal order

The Central African Republic is a state party to several international legal instruments, relevant for the child’s right to education, including the 1989 CRC.25

On the one hand, from the perspective of the CAR government, the rules laid down in this and other conventions signed by the government are laws. The CAR government seems to recognize the UN and the African Union as legitimate legislator, as seen for example by the fact that they signed the documents and that they report to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child.26 According to the CAR government, in their 2001 report to the UNCRC (CRC/C/CAF/2), “in the hierarchy of norms, international treaties are in second place, just after the Constitution and before domestic legislation” (19)).

On the other hand, CAR government policy is not exactly in line with this international and regional legislation. For example, the CAR government should grant every child in the CAR access to quality education,27 among others by providing free primary school education.28 However, in fact many CAR children are out of school (ICASEES 2012, 203–08; UNESCO n.d.),29 and an important reason for this is their inability to pay school fees.30 It is unclear what the legal consequences of acting against these international laws are exactly, and whether there are any at all.31

It is equally unclear whether international and regional law is recognized as such by the legal community of people residing in the CAR. The participants in the interviews did regularly mention either “children’s rights” or “human rights”, thereby seeming to acknowledge the existence of an international legal order. However, of the participants who spoke about the topic, the idea that children have rights seemed to be contested. It was perceived by some as something imposed by Western powers, and surely as something that did not mean much in a CAR context. Many seemed ambivalent about its status as proper law. Of all the respondents who had heard of children’s or human rights, only 24% seemed to understand it as a proper legal entitlement, even if permanently violated in the CAR context, as illustrated by the quote below.32 International staff of NGOs/UN, too, did not really claim a position for children’s rights, arguing that they mean little in the CAR context.33

Interview nr. 62. An employee of the Ministry of Education.

The first question is, do children have rights? In the context of the CAR, I personally think that we have to relativize that concept, compared to the Western world. Traditionally, in the CAR context, we think that the child does not have rights, only duties. S/he has to go to the field, to fish, to help the adults with the work. When s/he will attain a certain age, s/he will have rights. Today, there are changes. The youth asks for their rights. They are influenced by European ideas, human rights et cetera. Whether that is an advantage or an inconvenience, we still have to analyze.

It is worth noting that many children had an idea about what their right to education means – an idea that influences their behavior, but that is not related to any law that has been created by a sovereign. 63% of the children who claimed to know about the child’s right to education gave it a different meaning, not as a positive right to learn and develop, but as something quite different.34 For example:

Interview 8. An 11-year-old girl who is in class CP2 of a public school. She lives on an IDP site in a town in the center of CAR.

“For me, the child’s right to education in CAR, tells us not to move around randomly. So that the parents are not bothered a lot, when they have to come and search us […].”

These seem to be false beliefs in non-existent international law. However, as the source of this (idea of a) right was not clear, it could also refer to a local understanding of the child’s right to education resulting from a local legislator.35

4.2. The national legal order

CAR state written law has several articles relevant to the child’s right to education, namely the 2015 Constitution, the 2010 penal law and the 1997 law on education. The Ministry of Education also published decrees, such as the 2016 note circulaire that established school fees (République Centrafricaine Citation2016).

The legal community - people living in the CAR – seems to be aware of the existence of state written law and sometimes refers to it, but they usually do not know its content – including government officials. Of the 20 respondents that mentioned national law36 (mostly after I explicitly asked them), nine - of whom three were government officials - had false beliefs about the content,37 such as they argued that according to state law, the language of education is French,38 whereas in fact according to the 1997 education law, Sango and French are the two languages of teaching and “the teaching of, and in, Sango is introduced into the curriculum of primary school in the year 2000” (art. 42). They also argued that education is not obligatory according to state law,39 whereas in fact it is according to both the 2015 constitution (art. 7) and the 1997 education law (art. 6 and 50). Others had very limited knowledge of the law and could not say more than “the child has a right to education according to CAR law”,40 or “the chicotte41 is forbidden according to the national law on education”.42 Most state written laws on education were not mentioned by any respondent.

People who have knowledge of the state written law, do not have much faith in its rule; they do not expect it to influence the behavior of the people in the CAR, nor for compliance to be enforced. Several participants explained that in the CAR there is no system of national legislation; the laws are not known to the people, they are not publicly accessible. This is because many people are illiterate whereas the law is a written document. Even for the people who are able to read, the laws are not available in the language spoken by most people (Sango) but only in French, and most written laws are difficult to find, either on paper or online.43 In terms of enforcement, law enforcement officers are generally distrusted by the population (see section 3) and they do not seem to occupy themselves with education. If an education case gets in front of the judge, you cannot be sure what law will be applied44 and the outcome of the case might depend mostly on who pays the judge most and/or the socio-political position of the defendant.45

Another potential legislator of national law, when it comes to children’s education, seems to be the NGOs or, more specifically, the education cluster led by UNICEF.46 Several respondents indicated national laws on education that according to them were “UNICEF laws”, such as the obligation of parents to send their children to school, the prohibition to use the chicotte or the prohibition to letting children repeat a grade more than once.47

Do NGO(s) actually create law on a national level? This is hard to tell, especially because if such rules are created, they are unwritten. It is at least certain that NGOs have a lot of political power, and they do spread their messages over the CAR’s towns and villages through the practice of “sensibilisation” (a form of collectively informing and/or educating people, in some sense comparable to the role of the herald in the middle ages – although the emphasis of sensibilisation is more on providing information/education than on declaring law). Several respondents argued that NGOs use this practice to convince parents to send their children to school, often in cooperation with education inspectors.48 However, this does not seem to be a practice of declaring law, as they simply give arguments why it would be beneficial to send children to school, rather than argue that children must go to school because it is the law, because otherwise there will be legal consequences, etc.

Lombard (Citation2016, 217) indicates that in the CAR, there is:

opacity and uncertainty that surround who is ultimately in charge. Is it the UN mission? The French? Central African politicians? Perhaps there are complicated technical-legal answers to those questions, but on a day-to-day basis their answers are impossible to determine.

Some NGO employees might also understand NGOs, and in particular the NGO leading the education cluster, as a national level sovereign in the CAR, as indicated by the conversation below:

Interview 11. An employee of an NGO, working on the national level.

MH: So who would you say is governing the education decisions on a national level?

Resp: It’s definitely the NGOs. Definitely. I think there is a power relation, because humanitarian agencies have all of the money. But more and more I see the Ministry of Education being implicated, being involved in decisions, and they’re often put at the forefront, for example if we’re doing big events […]

MH: So in a way you are almost the minister of education?

Resp: Yes I would say in a way […]the power between [NGO] and the Ministry of Education is incomparable.

MH: Interesting, it is so un-democratic in a way.

Resp: It is, but then [NGO], they have all the expertise. Even the strategic document of the recovery plan, it is entirely developed by [NGO]. The Ministry of Education has 1 or 2 focal points, but the whole process is very much led by [NGO]. Because there are very clear deadlines and deliverables that need to be met with a certain quality of the work, and it’s clearly known that the Ministry of Education won’t be able to acquire the standard if they do it alone.

MH: The standard of the donors?

Resp: Exactly. […] the fact that the humanitarian organizations take such a, have such a … it almost takes away the responsibility of the government in providing access to education for the population. It almost takes away their credibility.

4.3. The religious legal order

Generally, it seems that religion – any kind of religion – does not constitute a legal order in the CAR, or at least not when it comes to education. None of the respondents, with one exception,49 referred to religion as a decisional power in their lives. Religious leaders themselves indicated that their role was not to rule, but to advise. When asked how they influenced the child’s right to education, for example among their followers, they would argue that their only role is to give advice (conseil) to for example parents or children.50 No respondent referred to any kind of holy scripture or other religious source as a source of law (or even of rules).

4.4. The local legal order

Alike the religious legal order, the local legal order does not seem to really have a say at least about education in the CAR. There are local leaders in CAR society, most notably the mayors and the village chiefs and perhaps we can also count the local NGO leaders under this heading. However, in line with other research findings (see section III), all these parties identified themselves as giving advise (conseil) to the people rather than legislating and/or enforcing anything.51 As this village chief explained:

Interview 28. Chief of a small village in the Center-South of the CAR, where there has not been a school for the past couple of years. At the time of the interview (August 2016), school was supposed to start again in September.

MH: Why do you not ask the literate parents to teach the children, each a few hours per week?

Resp: They cannot accept to teach if we don’t pay them.

MH: But what if they would just teach half a day per week?

Resp: […]I cannot command them. If they don’t want to, can you force them?

MH: You are the chief, do you not have that power?

Resp: I have power, but I cannot force people.

MH: So what kind of power do you have in relation to education?

[…]

Resp: Before, the young people were receiving the village chief. Nowadays, after the arrival of human rights, if you ask them to do something, they don’t accept it. When they don’t accept it, you have no right to take it by force.

This might have been different in the past, when perhaps village chiefs had more authority, as some respondents mentioned. However, none of the local leaders identified themselves as authorities and neither did respondents indicate a local leader as a decisional power over them in relation to education.52

One last exception worth mentioning is one town where at the time I was there for research (August 2016), an armed group (UPC, which is part of the ex-Seleka armed groups) was running a development program in the town, which included education. They ran a school which provided education for both children (during daytime) and adults (evenings and weekends). Teachers’ salaries and other expenses were paid for by the armed group’s leader, the General Ali Darass (also a sought war criminal), and when I visited the school it seemed like one of the better functioning schools in the country.53 Unfortunately I did not have the time to investigate the case more to see in what way it was law-based.

4.5. The school legal order

Most schools in the CAR have a document with school rules. These differ per school, but generally they state rules about at what time students and teachers have to be present in the morning, sometimes about clothes to wear (uniform or simply “clean clothes”), a prohibition on stealing and fighting and a prohibition on the use of corporal punishment by the teacher. See for an example.54

Table 4. An example of a document with school rules.

The situation in the school legal order seems to be quite similar to the situation of the national legal order, in particular when it comes to the role of the written law. Only few students and teachers seem to be aware of the formal written law within the school, and it does not seem to carry much weight. For example, one day when I came into a classroom to observe the lesson, the teacher had the school rules on her table and gave them to me to read. Article 10 stated that corporal punishment was forbidden. While I was reading the document in the classroom, she was walking through the classroom with a stick, beating students who did something wrong. After the lesson she came to see me, to ask about my research and mostly to inquire whether I knew things that she, as a teacher, could do better.55

4.6. The classroom legal order

The classroom seems to be perceived as a legal order by most students, with the teacher as the sovereign. Children are able to mention rules that the teacher imposes on them, including punishments if transgressed. These rules seem to be all orally transmitted.

The law (or rule) most mentioned by respondents is the fact that you are not allowed to make mistakes in your schoolwork. So if the teacher asks you to read something, or write something, or make a calculation, and you make a mistake, you’re doing something illegal.56 The most common punishment for this offense is for children to be hit with the chicotte.57

However, it has to be questioned whether this actually counts as “law”, or simply as a command backed by a direct threat. Hart (1961/Citation2012, 22-23) writes, when comparing the order of a gunman to the law of a legislator:

the gunman does not issue to the bank clerk […] standing orders to be followed time after time by classes of persons. […] We must therefore suppose that there is a general belief on the part of those to whom the general orders apply that disobedience is likely to be followed by the execution of the threat not only on the first promulgation of the order, but continuously until the order is withdrawn or cancelled. This continuing belief in the consequences of disobedience may be said to keep the original orders alive or ‘standing’ […].

In addition, Hart (1961/Citation2012, 51) argues that ‘the word ‘obedience’ often suggests deference to authority and not merely compliance with orders backed by threats.’. The question therefore is if students indeed feel an obligation to follow the rules of the teacher, even if there is no immediate, direct threat of getting hit. On the one hand, this does not seem to be the case because there are many students who on their own accord decide to exit the classroom, specifically not to endure any (more) corporal punishment.

The practice seems to be perceived by some more as a kind of terror – perhaps like a dictator reigning by terror (which does not exclude it necessarily from being law);

Interview 36. A 20-year-old girl who recently got her high school diploma (BAC) at a public school, in a city in the Center-South of the CAR:

Resp: When the teacher poses a question to the classroom, and the class cannot manage to find an answer, he starts to point at students, pointing, if he still doesn’t find a response, he starts letting students come to the front of the class. One by one, one by one, and if through bad luck one of them finds the answer, he can give the chicotte to all who are in front. Those who don’t know. Sometimes he will order the student who had the [correct] response to hit his/her fellow students.

MH: So you have also hit your fellow students?58

Resp: No, I haven’t, or yes, maybe I have done that, but I have already forgotten about it [laughs]

MH: Yes? Does it embarrass you?

Resp: Yes.

MH: Why does it embarrass you?

Resp: Because a person, completely like me, the way in which I hit, I try to put myself in his/her place and if someone hits me in that way it doesn’t do me good. What I don’t want others to do to me, I shouldn’t do that to others either.

MH: So why did you do it?

Resp: Because it was an order of the teacher. If I didn’t, he would have hit me. And if you don’t hit hard, your fellow student, the teacher will hit everyone. Hard.

On the other hand, it might be that students do feel an obligation to obey the classroom unwritten law if indeed they view the teacher as a sovereign, as someone who is the legitimate author of their actions (at least in part). To argue that legal enforcement is too harsh is not a denial of the legal power of the sovereign – it is rather an acknowledgment of the existence of a certain law and a certain legal enforcement, even if one disapproves of the type of enforcement from a normative perspective. As a legislator, the teacher may install the law “every student must know the correct answer to the question asked in the class”. Students may recognize the legitimate authority of the teacher as legislator, and therefore this (and other) rule(s) are laws. However, students may not agree with the enforcement measures executed as punishment for illegal behavior. The violent behavior of the teacher may limit the student’s belief in the authority of the teacher as a legislator in the longer run, because the student loses the respect required for personal (or, as Weber (Citation1978, 216–18) calls it, “charismatic”) authority. However, the student still respects the authority of the teacher as legislator based on what Weber calls “rational grounds”; they belief they owe obedience not to the teacher as an individual, but to the impersonal order of the school and the classroom.

This observation is supported by the fact that respondents do indicate several classroom rules, of which the most commonly cited were:

You are not allowed to make mistakes in your schoolwork59

You are not allowed to fight or hurt others60

You are not allowed to chat/make noise (bavarder) in the classroom61

You have to arrive on time for class62

Other rules were mentioned only by 3 respondents or less and therefore seem to apply more to individual classrooms, such as a prohibition on pregnancy, having to greet your parents, having to respect the teacher.63 In addition to the chicotte, quite a few other methods of enforcement/punishment were mentioned by respondents, of which the most common were:

Advise (conseil) by the teacher (mostly not seen as a punishment but mentioned as a way of enforcement nonetheless)64

Having to sit on your knees for a period of time65

Being sent home66

Positive enforcement was not mentioned by respondents at all in the context of obedience to rules, but was observed regularly during classroom observations by the researcher. Means of positive enforcement included a lot of singing and dancing. For example, when a student gives a correct answer, the teacher asks the class “and, is it good?” and the class responds “yes, it’s good, it’s beautiful!” (Et, c’est bien? – Oui, c’est bien, c’est joli!).67

4.7. The household legal order

It seems that CAR children and caretakers present different views on the household as a legal order. In relation to education, only 29% of children argued that their caretakers decide whether they go to school or not, whereas 71% of the caretakers interviewed argue that they are the ones who decide whether the child goes to school or not. The caretakers do this either through violence (“if my child does not listen, I use the chicotte”), or through advising the child (conseil).68 A possible unwritten law for the household community could be “the child has to go to school” or the opposite “the child is not allowed to go to school”. These were the only two possible household laws found during the research in relation to education. Whether this is indeed law for the household community seems questionable and might differ per household. In the case of the caretaker as adviser, the caretaker is not the legislator since the decisional power lies with the child, and there are no legal consequences of going against the advice. In the case of enforcement through violence, whether this is indeed legal enforcement depends on how the child perceives the situation – is it random violence of someone trying to force you to do something, or is it the legal enforcement of a legitimate law? Both situations seem to occur in the CAR.

A factor influencing the possible status of the caretaker as legislator seems to be the situation of the household. During childhood, CAR children often move through different households. For example, a child might be cared for as a baby, then start contributing to the family income by working in the mines for a few years, then live on the street for a while, before they move to the household of different family members.69 This process of moving around different households is greatly influenced by poverty, armed conflict and disease.

Most likely the instability of households for children makes them more autonomous; knowing that you often cannot count on your family to help you, as you cannot even know for how long they are going to be around, makes that you have to take care of yourself (see more below).

4.8. The autonomous child

At the end of the day, CAR children for the most part seem to be autonomous, in the sense of autos-nomos: making law for one’s self. Some CAR children live without a family and as a consequence they have to take care of themselves. But even for the ones who do share a household with caretakers, few of them seem to think of the caretakers as legislators. There was in this sense no difference between the different age groups.

As has been mentioned, most children argue that they themselves decide whether they go to school (71%). This is confirmed by teachers and education inspectors who observe that children are often left to themselves, especially when the family cannot afford school fees.70 These children have to go around searching money for school fees, asking all adults they know for money, working for money or, in the case of girls, finding a boyfriend who will pay for them. Although some children are heavily influenced by their families in taking this decision, they still argue it is them who decide, and they do indeed sometimes act against the wishes of their family.

Several children argued that even though their caretakers had different preferences, they went to school anyway – even when threatened with violence.71 So in these cases, it is only when there is a direct threat of violence that the will of the caretaker was enforced upon the children, much like a gunman forcing the bank clerk to hand in money by threatening him/her with a gun, rather than a legislator ruling over the addressee of the law. See for example the reasoning of this girl:

Interview 32. A 14-year-old girl who lives in a town in eastern CAR.

MH: Who decides if you go to school or not?

Resp: Me.

MH: And if you say in the morning I am not going to school, do you not go?

Resp: No. My father will hit me with the chicotte.

MH: So, it’s your father who says you have to go to school, or is it you who chooses to go?

Resp: It’s me. Who chooses to go to school.

Other examples of the autonomous position of the child that came to the fore in the research were participants’ observations that children themselves decide to go to school (they enroll themselves, they themselves are responsible for finding the money required for enrolment),72 or when participants argued that the child itself is responsible when they choose to have sex with the teacher in return for good marks.73

5. Conclusion: law on education for children in the CAR

As has been shown under section 4, there seems to be little law for children in the CAR that is relevant in their lived realities, when it comes to their right to education. For all of the potential legal orders and their laws related to education, with the exception of the classroom legal order, it seems that one or several of the characteristics of a legal order are missing so that we cannot properly call it a legal order, and we cannot properly call its norms laws.

On the level of the international legal order, it is unclear whether the basic norm is recognized by the relevant legal community. The CAR government did sign international and regional conventions and even reports on them (although these reports are most likely written, at least in part, by NGOs rather than the CAR government).74 However, there seems to be little recognition among government employees of international norms as laws, including the fact that they do not know its content. Also there do not seem to be legal consequences of not abiding the law. The CAR population generally does not seem to know international laws either nor are they enforced.

On the level of the national legal order, the CAR government does publish formal, written law, but these documents are very difficult to access, especially for the mostly illiterate, Sango speaking, non-digital75 CAR population. So although the CAR population, as the legal community of the CAR national legal order, seems to recognize the CAR government as its legitimate sovereign, they do not have knowledge of its laws nor are these laws enforced.

Another potential legislator on the national level would be the NGOs, specifically the cluster education. However, it is unclear to what extent they engage in legislating, and even if they do, again these laws are mostly not known by the legal community nor enforced.

Both the religious and local leaders seem to give advice to the population rather than legislate over them. The school and household legal orders, too, seem to generally lack recognition of their norms as laws by the relevant legal community.

A clear exception here seems to be the legal order of the classroom. The teacher is seen as a legal authority by most students, and s/he creates and enforces law over the students. Although the enforcement practices are often perceived as too harsh and unjust (though not by all), and students might adhere to the classroom law more out of fear for punishment than out of respect for the law (besides, the most important classroom law is “you are not allowed to make mistakes”, a law that is extremely difficult to adhere to because students simply do not always know the correct answers to the teacher’s questions), the laws of the classroom are still recognized as law.

However, on the whole when it comes to education, it seems that CAR children are mostly autonomous. They do not feel that anyone makes any law over them; not the government, not the NGOs, not the religious leaders or the village chiefs – with the exception of the teacher in the classroom. Even when frequently facing (threats of) violence, mostly by their caretakers, they take their own decisions, such as whether to go to school or not.

This specific approach to the case study, as described in the theoretical and methodological sections of this paper, gives a clear overview of all legal orders and their laws as regards education in the CAR. This is possible because the framework provides:

Definitions of what is understood by “law” and “legal order”, including the empirical elements that constitute a legal order

A way in which to include the child’s perspective in researching relevant laws related to the protection/violation of children’s rights, whereby smaller potential legal orders such as the classroom and the household are included in the legal analysis

A methodology for the (empirical) study of all laws relevant for an understanding of the protection/violation of children’s rights

Hopefully this overview will be of use to anyone who wants to improve the situation for CAR children.76 Based on this research, one can conclude that for example if one would want children to go to school, the most effective intervention would probably be to empower these largely autonomous children themselves, rather than to aim interventions at caretakers, religious leaders and/or village chiefs. Another option might be to more actively involve the teachers, who are viewed by the children as legitimate authorities.

Through this study, anyone wanting to intervene at least gets a clear picture of the current state of legal orders surrounding the child’s right to education in the CAR. How the data will be used is a political decision. It might lead politicians and/or NGO employees to conclude that law is perhaps not the most useful instrument through which to intervene in the CAR. This goes beyond the scope of the current research. It is however shown that to approach children’s rights research through a far-reaching legal pluralist theoretical framework which includes the study of legal orders surrounding the children, such as the household, the school and the classroom, gives a much more precise and detailed picture of the total pluralism of legal orders surrounding a child, which in turn may create more understanding on the question of why a child’s right is being violated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 According to data of the US government, 51% of CAR people are Protestants, 29% Roman Catholic, 10% Muslim, 4,5% other religious groups and 5,5% have no religious beliefs (Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (2014)).

2 Informal interviews are discussions which I recorded with the permission of the participant. These conversations were more spontaneous discussions about the subject of the research, which I used to test certain theories or to discuss specific subjects.

3 Including: 6 education inspectors, 9 politicians, 17 NGO/UN employees working on education and/or child protection, 3 members of the APE, 13 religious leaders.

1 See for example de Sousa Santos (Citation2002, 392–393), who defines different legal orders, including the family.

2 Although the current article focuses on children’s rights research, it could be interesting, and in my view certainly possible, to apply the proposed theory and methodology to human rights research, and I do hope it may also be useful for other empirical study of law.

3 In this way, the proposed theory and methodology in this article provide a way in which to find the information required by children’s rights strategies, as indicated by Corradi and Desmet (Citation2015b, 12–13) when they argue that such a strategy “needs to be rooted in grounded knowledge about the lived realities of children and the multiple normative orders at play.”

4 For an overview, see Corradi and Desmet (Citation2015a, Citation2015b).

5 See also Corradi and Desmet (Citation2015b) who in their analysis of the literature on children’s rights and legal pluralism, keep referring to normative orders, norms, laws, standards, without indicating what the difference is between these. Consequently, it is unclear why certain research includes the study of legal orders, and which research in fact studies how for example the protection of international law might be influenced by local social practices, traditions, etc. It is also in this sense that the theory presented in this paper is different from Moore’s conception of the semi-autonomous field, because the practices and rules that she finds in the New York garment industry and the Chagga tribe, she considers non-legal (Moore Citation1973).

6 In contrast to Sacco (Citation1995, 455–56) and Glenn (Citation2014, 63, 67), I argue in this article that without sovereign there is no law. A sovereign may appear in many different forms, including a deity, a dictator or a complete legal community, but there is no law without sovereign for the purpose of this article. Rules without the legal power of a sovereign are simply social rules. Having said that, if indeed there are social orders that possess all other characteristics of the legal order and that the community considers a legal order with laws – as someone recently told me can be found in some Kenyan villages – this might be an exception to this rule.

7 See also Arendt (1970, 44): “When we say of somebody that he is ‘in power’ we actually refer to his being empowered by a certain number of people to act in their name. The moment the group, from which the power originated to begin with (potestas in populo, without a people or group there is no power), disappears, ‘his power’ also vanishes”.

8 See Hobbes (Citation1651/1996, 88–91, 120): “Since man's passions incline men to peace, out of fear of death […] they covenant amongst themselves to submit to a sovereign. In other words; by covenant they create an artificial person, a Leviathan, and they appoint one man to bear their person of whose actions they are all the author”.

9 This point, although widely accepted in theories of legal pluralism, certainly is contested among legal scholars in general. For a more elaborate defence of this approach, see Hopman (Citation2017).

10 Similar to Tamanaha (Citation2000, 315).

11 This initial identification of potential legal orders is meant as a first start and has to be set up broadly so as to hopefully not exclude any existing legal order related to the research topic. The researcher has to keep in mind that it is quite possible that s/he will find other legal orders when engaging in field research, or that legal orders turn out not to exist or function and be sufficiently flexible to incorporate these into the study.

12 A possible exception here might be some elements of Bokassa’s reign – according to Bigo (Citation1988, 61), farmers in the CAR in the beginning complied to “operation Bokassa”. Farmers had to sow coton off all fields, and if they would not succeed to (which often happened), they would be threatened with prison sentences. However, the population worked hard to attain these goals only during one or two harvests, and then went back to their traditional ways and rhythm.

13 “In July 2010, President Bozizé made a speech saying that the CAR police was ‘full of bandits’ and that people should not trust them” (Marchal Citation2015, 58). See also Knoope and Buchanan-Clarke (Citation2017, 11); World Bank Group (2012, 37).

14 According to Bigo (Citation1988, 86), at least in 1988 and probably since independence, the CAR politicians are no more than the puppets of the French government.

15 See also Lombard and Batianga-Kinzi (Citation2015, 9).

16 A very striking recent example is the attack of an armed group on the camp for internally displaced people in the town of Kaga Bandoro on October 12, 2016. The camp which was situated directly next to a UN MINUSCA camp which houses 70 police officers and 200 soldiers. Although the armed group only consisted of about 60 soldiers, they have ‘shot, stabbed, or burned to death the civilians, including at least four women, five children, three older people, and four people with disabilities’ (Human Rights Watch 2016). See also: MINUSCA Human Rights Division (2016).

17 Although a Special Criminal Court has been established, until date perpetrators of such crimes live in the CAR with impunity. See Mudge (Citation2017a, Citation2017b); Knoope and Buchanan-Clarke (Citation2017, 11).

18 The kind of legal orders identified resemble very loosely the six legal orders defined by de Sousa Santos (Citation2002, 68, 85). Potential legal orders were defined based on earlier mentioned literature research.

19 In qualitative research in general, but in research with children in particular, researchers very quickly and easily engage in adult ethnocentric bias. Because research questions are usually designed by adults, they are often oriented towards “adult thinking”. In addition, research data is again usually interpreted by adults. Leading to a great misunderstanding of the actual beliefs and ideas of children. See for example Powell and Smith (Citation2009, 125); Christensen and James (2008, 2); Alderson (2008, 155); Morrow (2005, 151).

20 Over the last decades there have been many researchers experimenting with giving more responsibility for the research process to children. See for example Woodhead and Faulkner (Citation2008); Powell and Smith (Citation2009); Alderson (Citation2008); Davies (Citation1984).

21 Through the following text, for reasons of clarity I will refer to this group as “parents” or “caretakers”, even if in the CAR the notion of parenthood is much more fluent than we are used to in the West. Mostly I would not know if a child’s “parent” was either his/her biological parent, another family member, an adoptive parent and/or a tuteur. Therefore “adult with parental responsibility” would be the more correct term.

22 The literature research included all kinds of sources that could tell me something about the history, culture, education, law, human rights and children’s rights situation in the CAR. Sources included international legal documents, NGO reports, available academic articles, newspaper articles, PhD theses.

23 The CAR has been plagued by recurring outbursts of violence over at least the past 20 years. Armed groups are present in many areas in the country and their movements often make whole areas inaccessible. However, as far as reasonably possible, I did try to also visit areas where armed groups were actively present.

24 One of the reviewers remarked that at least from a (human) rights perspective, there is a basic difference between the child’s right to education and laws on education, since the latter may include for example administrative laws. This is true, yet because in this case I tried to understand the protection/violation of the child’s right to education in the CAR, I think it is relevant to study all laws related to education, since they could all potentially contribute to the protection or violation of this right.

25 Namely: Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) (1948); International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) (1966); African (Banjul) Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights; Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989); United Nations Convention against Corruption (2003); African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (Kampala Convention) (2009); Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment (1984).

26 Although this argument might be slightly deceiving, if we realize that these reports, even if they are written on behalf of the State, are most likely written by the international staff of international organizations.

27 African Charter on Human and People’s Rights (Banjul Charter) (1981), art. 17; International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) (1966), art. 13; Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) (1989), art. 28-29.

28 ICESCR (1966), art. 13.2; UDHR (1948), art. 26 (1).

29 Interviews 5, 8, 11-14, 18, 21, 25, 28, 29, 36, 44, 45, 48, 50, 51, 53, 54, 57, 64, 76, 77, 80; observation 18.

30 Including inability to afford necessary school materials (books, notebooks, etc). Interviews 1, 4- 7, 10, 12, 14-16, 21, 22, 24, 25, 27- 29, 38, 42- 45, 47- 49, 51, 53, 54, 56, 57, 59, 60, 70, 71, 80, 81, 120, 121, 127, 128. See also: Banque Mondiale (Citation2008, 44).

31 Of course this is generally an issue in international law. See, among others Chinkin (Citation1989); Hafner-Burton (Citation2008).

32 Interviews 4, 8–10, 12, 14–21, 24, 28, 29, 32, 34, 37, 39, 40, 42, 43, 45, 47-49, 51, 55, 57, 59-62, 64, 65, 75, 80-83, 86, 87, 92.

33 Interviews 11, 16, 17, 61, 84.

34 Interviews 8, 9, 10, 12, 19-21, 32, 37, 59.

35 I thank the anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

36 Interviews 4, 14, 16, 17, 22, 42, 43, 52, 53, 60, 62, 75, 80-82, 90, 91, 96, 104, 109

37 Interviews 14, 16, 17, 22, 52, 53, 62, 96, 109.

38 Interviews 52, 62, 96, observations 1, 8, 13-16, 20, 22, 24.

39 Interviews 4, 16, 62.

40 Interviews 22, 75, 81.

41 A whip used for corporate punishments in CAR classrooms in particular, and in CAR society in general. It consists of a wooden stick with rubber bands (cut out from tires) attached.

42 Interviews 22, 42, 43.

43 Interviews 16, 22, 52, 90, 91. It is indeed true that although I was able to find the penal code and the text of the constitution online (both in French, and not easy to find), I could not find the education law anywhere. In my effort to find this text, I searched online, I searched in the general library of the university in Bangui as well as in the library of the law faculty of the same university, I asked several government officials (both working on national and local level, including all education inspectors). The only person finally able to provide me with the text of this law was an NGO employee working on the national level. The document I received was sometimes hard to read.

44 For example, a lawyer I spoke to had a booklet with an old version of the penal law, printed in the 90s. I asked him whether he had a newer version, he said that the court also still worked with this older version.

45 Interviews 16, 22, 52, 73, 90, 91, 104. On the lack of independent judiciary in the CAR several other authors have written. See for example Lombard who writes that ‘In the research project I led on the topic of access to justice in CAR […] every single person interviewed described the state judicial sector as wholly corrupt’ (2016, 193). See also World Bank Group (2012), Smith (Citation2015), Ngoumbango Kohetto (Citation2013) and Marchal (2015).

46 In situations of humanitarian crises, humanitarian organizations are grouped per main sector of humanitarian action, such health or education. One leading party is appointed – this can be either the government or, in the case of CAR, an NGO (IASC Citation2015).

47 Interviews 47, 53, 55, 92, 96.

48 Interviews 13, 17, 51, 52, 81; observation 13.

49 Interview 10, where a mother indicated that the Imam of her village preached to the Muslim community that they should not send children to school. She added that she disagreed and she simply sent her children to school.

50 Interviews 15, 23, 64, 65, 81, 89, 95, 96, 127, 128.

51 Interviews 7, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 22, 28, 47, 53, 55, 57, 70, 79, 80, 81, 84, 93. There was one exception to this, namely I encountered a mayor who argued that she obliged all children in the village to go to school. She argued that she would send the gendarmerie to the mines to collect the children and send them to school. She would also fine the parents if children were not in school. Due to this policy, she said, now 100% of the children between ages 6–18 of the village were in school (interview 56). However, it is hard to take this very seriously, first of all because there was only one school with two classrooms and two teachers in the village – classrooms which were overcrowded as it was, with children no older than 12 (observations 14 and 15). Second, her own secretary denied the story, saying it was a lie (interview 57).

52 See also: World Bank Group (Citation2012), Bigo (Citation1988).

53 Interviews 23, 93, observation 25.

54 Interviews 4, 17, 51, 52, 62, 75, 80; observations 16, 22.

55 Observation 16.

56 Interviews 18, 21, 31, 36, 37, 40, 47, 50, 59, 60, 68, 83, 92.

57 Interviews 18-21, 24, 31, 36, 37, 39-41, 45, 47, 49, 50, 59-61, 68, 78, 80, 83, 92, 107.

58 Because respondent indicated earlier in the interview that she was a good student.

59 Interviews 18, 21, 31, 36, 37, 40, 47, 50, 59, 60, 68, 83, 92.

60 Interviews 18, 31, 39, 40, 45.

61 Interviews 18, 19, 21, 24, 31, 36, 41, 45, 54, 70.

62 Interviews 18, 40, 49, 80, 82, 83.

63 Interviews 20, 21, 39, 40.

64 Interviews 19, 20, 24, 32, 54, 55.

65 Interviews 31, 41, 48, 49, 55, 70, 71.

66 Interviews 31, 32, 39, 40, 45, 49.

67 Observations 6, 16, 18.

68 Interviews 1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 13, 15, 16, 18, 20, 23, 25, 32, 34, 36, 39, 40, 46, 47, 49, 50, 54, 55, 66, 69, 72, 80, 82, 83; observation 17.

69 Interviews 1, 6, 14, 33, 36, 37, 38, 41, 44, 50, 55, 75, 76, 77, 78.

70 Interviews 4, 7, 42, 43, 47, 48, 49, 53, 54, 57, 81; observation 12.

71 Interviews 6, 8, 18, 39, 45.

72 Interviews 19, 21, 24, 29, 31, 32, 34, 36, 37, 40, 43, 45, 48, 50, 55, 57, 60, 81; observation 20.

73 Interviews 22, 36.

74 CRC/C/CAF/Q/2/Add.1 (4-6); interview 11.

75 See also World Bank Group (2017, 13), showing that of the 7 regions in CAR, in 4 regions 0% of the principal towns have electricity available.

76 More practical and detailed information on the child’s right to education in the CAR can be found in the popular scientific report on the case study. See: Hopman, Dopani, and Saragnet (Citation2017).

References

- Alderson, P. 2008. Young Children's Rights: Exploring Beliefs. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Areeda, P. E. 1996. “The Socratic Method (SM) (Lecture at Puget Sound, 1/31/90).” Harvard Law Review 109 (5): 911–22.

- Arendt, H. 1970. On violence. Orlando: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

- Banque Mondiale. 2008. Le Système éducatif Centrafricain: Contraintes et marges de manoeuvre pour la reconstruction du système éducatif dans la perspective de la réduction de la pauvreté. Washington: Banque internationale pour la reconstruction et le développement/Banque mondiale.

- Bierschenk, T., and O. de Sardan. 1997. “Local Powers and a Distant State in Rural Central African Republic.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 35 (3): 441–68. doi:10.1017/S0022278X97002504.

- Bigo, D. 1988. Pouvoir et Obéissance en Centrafrique. Paris: Karthala.

- Carayannis, T., and L. Lombard. 2015. “Making Sense of CAR: An Introduction”. In Making Sense of the Central African Republic, edited by T. Carayannis and L. Lombard, 1–16. London: ZED Books.

- Chinkin, C. M. 1989. “The Challenge of Soft Law: Development and Change in International Law.” The International and Comparative Law Quarterly 38 (4):850–66. doi:10.1093/iclqaj/38.4.850.

- Christensen, P., and A. James. 2008. "Introduction: Researching Children and Childhood Cultures of Communication”. In Research with Children: Perspectives and practices, edited by P. Christensen and A. James, 1–9. Oxon: Routledge.

- Corradi, G., and E. Desmet. 2015a. “Editorial Introduction: Children and Young People in Legally Plural Worlds.” The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 47 (2): 170–4. doi:10.1080/07329113.2015.1099791.

- Corradi, G., and E. Desmet. 2015b. “A Review of Literature on Children’s Rights and Legal Pluralism.” The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 47 (2): 226–45. doi:10.1080/07329113.2015.1072447.

- Cremin, T., E. Glauert, A. Craft, A. Compton, and F. Stylianidou. 2015. “Creative Little Scientists: Exploring Pedagogical Synergies between Inquiry-Based and Creative Approaches in Early Years Science.” Education 43 (4): 404–19. doi:10.1080/03004279.2015.1020655.

- de Sousa Santos, B. 2002. Toward a New Legal Common Sense. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- De Vries, L., and T. Glawion. 2015. Speculating on Crisis: The Progressive Disintegration of the Central African Republic’s Political Economy. Den Haag: Clingendael.

- Davies, B. 1984. “Children through Their Own Eyes.” Oxford Review of Education 10 (3): 275–92. doi:10.1080/0305498840100305.

- Ehrlich, E. 1913/1975. Fundamental Principles of the Sociology of Law. New York: Arno Press.

- Glenn, H. 2014. Legal Traditions of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gregson, J. 2017. The World’s Richest and Poorest Countries. Accessed 20 June 2017. https://www.gfmag.com/global-data/economic-data/worlds-richest-and-poorest-countries

- Hafner-Burton, E. M. 2008. “Sticks and Stones: Naming and Shaming the Human Rights Enforcement Problem.” International Organization 62 (4): 689–716. doi:10.1017/S0020818308080247.

- Hart, H. L. A. 1961/2012. The Concept of Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Haugaard, M. 2008. “Power and Legitimacy” In Knowledge as Social Order: Rethinking the Sociology of Barry Barnes, edited by Massimo Mazzotti, 119–130. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Helliwel, J., R. Layard, and J. D. Sachs. 2017. World Happiness Report 2017. Accessed 27 June 2017. http://worldhappiness.report/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/03/HR17.pdf

- Hobbes, T. 1651/1996. Leviathan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hopman, M. J. 2017. “Lipstick Law, or: the Three Forms of Statutory Law.” The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 49 (1):54–66. doi:10.1080/07329113.2017.1308787.

- Hopman, M. J., P. Dopani, and D. C. B. Saragnet. 2017. The Child’s Right to Education in the Central African Republic. Accessed 9 June 2018. http://kinderrechtenonderzoek.nl/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Childrens-raport-ENG-OK.pdf.

- Human Rights Watch. 2016. Central African Republic: Deadly Raid on Displaced People: UN Peacekeepers Should Offer Increased Protection. Accessed 6 August 2017. https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/11/01/central-african-republic-deadly-raid-displaced-people

- IASC: Inter-Agency Standing Committee. 2015. Reference module for cluster coordination at country level. Accessed 3 December 2018. https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/cluster_coordination_reference_module_2015_final.pdf

- ICASEES: Institut Centrafricain des Statistiques et des Études Économiques et Sociales. 2012. Enquête par grappes à indicateurs multiples – MICS couplée avec la sérologie VIH, RCA, 2010: Suivi de la situation des enfants, des femmes et des hommes. Bangui: ICASEES.

- International Crisis Group. 2007. Central African Republic Anatomy of a Phantom State. Accessed 29 March 2018. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/central-africa/central-african-republic/central-african-republic-anatomy-phantom-state

- Kelsen, H. 1949/2007. General Theory of Law and State. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

- Kelsen, H. 1967/2009. Pure Theory of Law. Clark, NJ: The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd.

- Keys, C. W., and L. A. Bryan. 2001. “Co-Constructing Inquiry-Based Science with Teachers: Essential Research for Lasting Reform.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 38 (6):631–45. doi:10.1002/tea.1023.

- KidsRights Foundation. 2017. The KidsRights Index 2017. Accessed 27 June 2017. https://kidsrights.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/The%20KidsRights%20Index%202017.pdf

- Kitzinger, J. 1997. “Who Are You Kidding? Children, Power, and the Struggle Against Sexual Abuse.” In Constructing and Reconstructing Childhood, edited by A. James and A. Prout, 157–183. London: Falmer Press.

- Knoope, P., and S. Buchanan-Clarke. 2017. Central African Republic: A Conflict Misunderstood. Capetown: The Institute for Justice and Reconciliation.

- Lipman, M., A. M. Sharp, and F. S. Oscanyan. 1980. Philosophy in the Classroom. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Lombard, L., and S. Batianga-Kinzi. 2015. “Violence, Popular Punishment, and War in the Central African Republic.” African Affairs 114 (454): 52–71. doi:10.1093/afraf/adu079.

- Lombard, L. 2016. State of Rebellion: Violence and Intervention in the Central African Republic. London: ZED Books.

- Marchal, R. 2015. “Being Rich, Being Poor: Wealth and Fear in the Central African Republic”. In Making Sense of the Central African Republic, edited by T. Carayannis and L. Lombard, 53–75. London: ZED Books.

- Minner, D. D., A. J. Levy, and J. Century. 2010. “Inquiry-Based Instruction - What Is It and Does It Matter? Results from a Research Synthesis Years 1984 to 2002.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 47 (4): 474–96. doi:10.1002/tea.20347.

- MINUSCA Human Rights Division. 2016. Special Report on Kaga-Bandoro Incidents: 12 to 17 October 2016. Accessed 6 August 2017. https://minusca.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/minusca_report_kaga_bandoro_en.pdf.

- Moore, S. F. 1973. “Law and Social Change: The Semi-autonomous Social Field as Appropriate Subject of Study.” Law & Society Review 7 (4): 719–46.

- Morrow, V. 2005. “Ethical Issues in Collaborative Research with Children”. In Ethical Research with Children, edited by A. Farrel, 150–165. Berkshire: Open University Press.

- Mudge, L. 2017a. Killing without Consequence: War Crimes, Crimes against Humanity and the Special Criminal Court in the Central African Republic. Human Rights Watch. Accessed 6 August 2017 https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/07/05/killing-without-consequence/war-crimes-crimes-against-humanity-and-special

- Mudge, L. 2017b. Justice Needed for Lasting Peace in Central African Republic: Prosecute Those Responsible for Grave Crimes. Human Rights Watch. Accessed 6 August 2017 https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/06/20/justice-needed-lasting-peace-central-african-republic

- Ngoumbango Kohetto, J. 2013. L’accès au droit et à la justice des citoyens en République centrafricaine. Bourgogne: Université de Bourgogne/HAL.

- O’Brian, S. 2017. Statement and Speech. Accessed 9 June 2018. https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/statement-and-speech/ERC_USG%20Stephen%20O%27Brien%20Statement%20to%20the%20Memeber%20States%20on%20DRC%20and%20CAR%20-%2007Aug2017.pdf

- Powell, M. A., and A. B. Smith. 2009. “Children's Participation Rights in Research.” Childhood 16 (1):124–42. doi:10.1177%2F0907568208101694.

- République Centrafricaine 2016. Decision: Portant Fixation des Frais d’Inscription au Fondamental 1, 2, Secondaire General et Technique et du Retrait des Diplomes. Accessed 1 April 2017. https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/fr/operations/central-african-republic/document/rca-note-circulaire-frais-de-scolarit%C3%A9-sept16

- Sacco, R. 1995. “Mute Law.” The American Journal of Comparative Law 43 (3): 455–67.

- Simon, C. 2015. “The ‘Best Interests of the Child’ in a Multicultural Context: A Case Study.” The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 47 (2): 175–89. doi:10.1080/07329113.2015.1091188.

- Smith, S. W. 2015. “CAR’s History: The Past of a Tense Present”. In Making Sense of the Central African Republic, edited by T. Carayannis and L. Lombard, 17–52. London: ZED Books.

- Tamanaha, B. Z. 2000. “A Non-essentialist Version of Legal Pluralism.” Journal of Law and Society 27 (2): 296–321. doi: 10.1111/1467-6478.00155.

- The Commonwealth. 2016. Global Youth Development Index and Report. London: Commonwealth Secretariat. Accessed 27 June 2017. http://cmydiprod.uksouth.cloudapp.azure.com/sites/default/files/2016-10/2016%20Global%20Youth%20Development%20Index%20and%20Report.pdf

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2016. 2016 Human Development Report.

- UNESCO. n.d. Central African Republic. Accessed 4 April 2017. http://uis.unesco.org/country/CF

- Vansielegem, N., and D. Kennedy. 2011. “What Is Philosophy for Children, What Is Philosophy with Children - After Matthew Lipman?” Journal of Philosophy of Education 45 (2): 171–82. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9752.2011.00801.x.

- Weber, M. 1949. On the Methodology of the Social Sciences. Glengoe: the Free Press of Glengoe.

- Weber, M. 1978. Economy and Society. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Woodhead, M., and D. Faulkner. 2008. “Subjects, Objects or Participants? Dilemmas of Psychological Research with Children”. In Research with Children: Perspectives and Practices, edited by P. Christensen and A. James, 10–39. Oxon: Routledge.

- World Bank. 2017. Central African Republic. Accessed 2 April 2017. http://data.worldbank.org/country/central-african-republic