Abstract

From the nineteenth century to the present day, external peoples, companies, and governments have perpetrated disrespectful attitudes and behaviours toward Amazonian Originary Peoples. In response, Originary Peoples have increasingly adopted their own protocols of respectful interactions with external actors. However, research on the development and implementation of intercultural understandings of “respect” in pluri-cultural interactions has been scarce. Drawing on findings from collaborative research in the Peruvian Amazon, this article explores how Asheninka and Yine perspectives and practices of “respect” inform and could transform euro-centric conceptions and hegemonic consultation processes based on “mutual respect,” proposing instead a practice of “intercultural respect.” The study was initiated at the invitation of Asheninka and Yine community members themselves. Long-term relationships catalysed an invitation to co-design a community-based collective endeavour, which began in 2015. The discussion and findings presented in this article are part of a larger project that attempts to portray how Asheninka and Yine collaborating communities want to be respected under their own terms. This collaborative work proposes: 1. An Originary methodology; 2. A paradigm-encounter frame; and 3. Ten principles to guide “intercultural respect” for the Peruvian Amazon.

Introduction

Relationships between Amazonian Originary Peoples and external agents have been tortuous for centuries. Violent incursions into Amazonian Originary territories were exacerbated during the consolidation of independence of the Peruvian Republic from the Spanish Crown in 1821, when “independence was granted to the European colonizers and their descendants” and not to the Afro-descendant or Originary Peoples (Chaumeil Citation2014; Espinosa Citation2009a; Santos Citation2020, 296). To prevent the loss of recently “independent” territory at the hands of bordering countries, the new government organized European and internal colonisation of the Amazon (Chirif Citation2017). To this day aggressive state policies have facilitated the expropriation and exploitation of Originary territories (Chavarría, Rummenhöller, and Moore Citation2020; López Citation2009). Whether for settlement, occupation, or exploitation, Amazonian ancestral territories are taken by force and offered to the highest bidder.

Recent political struggles have also shed light on historical and contemporary aggression by the state. In 2009, a violent clash known as the Baguazo emerged in the Amazon between Originary Peoples and military forces. The Baguazo was a grassroots response to governmental approval of policies implementing a Free Trade Agreement with the United States, which endangered the individual and collective rights of Amazonian Originary Peoples (Espinosa Citation2009a). After the Baguazo the government’s imaginary of the Amazon changed. From an empty and wasted place to be exploited (Valdivia Citation2009) to a place with “natives,” seen as an “obstacle and a hindrance” to the country’s development (Alfaro Citation2020). One of the most significant outcomes of the Baguazo was the incorporation of the right to prior consultation in the Peruvian national legal system (Urteaga-Crovetto Citation2018). The enactment of Law 29785 on the Right to Prior Consultation of Originary or Indigenous Peoples Recognized in Convention 169 of the International Labour Organization (ILO)Footnote1 (hereinafter referred to as the Prior Consultation Law, or “PCL”) brought initial hope to Peruvian Originary Peoples through the legal promotion of “mutual respect” and a virtual space to voice communities’ desired futures. The PCL is the legal interface structure between outsiders and Originary Peoples. However, as Urteaga-Crovetto notes, when implemented it “reduced the substance of the right to consultation and overrode the right to consent” (2018, 21).

International and national law and policies on consultation encourage “mutual respect” as the most important practice for peaceful coexistence in culturally diverse scenarios. The literature on “consultation” is extensive, with critical accounts revealing the process to be embedded in coloniality disrespecting Originary Peoples’ self-determination (Merino Citation2018; Achiume Citation2019; Flemmer and Schilling-Vacaflor Citation2016; Torres Citation2016; Gamboa and Snoeck Citation2012). However, research on the development and implementation of intercultural understandings of “respect” has been scarce, and it is this aspect that is the focus of our research. Researchers argue that a crucial way to address disrespectful attitudes and behaviours is through contextualizing the current PCL and articulating Originary visions of relationships under their own paradigms (Schilling-Vacaflor and Flemmer 2013; Gamboa and Snoeck Citation2012). Originary Peoples have increasingly adopted their own “respectful protocols” with external actors. We ask: does the “mutual respect” approach reflect how Originary Peoples imagine, practice, and feel “respect”? Is “mutual respect” paradigmatically dependent? Who defines the praxis of “mutual respect,” and how was it defined? Can this respect be “mutual” if Amazonian Originary sets of subjectivities, sensibilities, and practices of “respect” are unknown or neglected? What could a framework for the praxis of intercultural respect look like?

Drawing upon six years of collaborative research with Asheninka and Yine Peoples in the Atalaya Province of the Peruvian Amazon, this article analyses collaborators’ perspectives on “respect” and proposes ways in which they may inform and transform hegemonic conceptions and practices of “mutual respect” as they are executed in consultation processes. The methodology presented in this article is part of a larger project that aims to portray how Asheninka and Yine collaborating communities want to be respected under their own paradigms. Testimonies from our collaborative research show that their subjectivities, sensibilities, and practices are not considered or reflected in the current dominant conceptions of “respect.” Asheninka and Yine Peoples argue that their conceptions and practices of “respect” exceed those articulated in hegemonic spheres. Moreover, Asheninka and Yine collaborators articulate the importance for them that external agents “respect” their current norms so that external and Originary normative systems can be in dialogue.

We first describe the context of relationships between external agents and Asheninka and Yine Originary Peoples, and the Originary methodological approach of the research, which results from long-term relationships with collaborators. Second, we explore features of Originary Amazonian paradigms about “respect.” Third, we lay out the theoretical approach used to frame the co-weaving of knowledges with Asheninka and Yine Peoples. Fourth, we introduce a paradigm-encounter frame to represent the relationships between external and Originary paradigms and suggest ten guiding principles for an “intercultural respect” approach. Finally, we offer reflections on the limitations and paradigmatical bias of “mutual respect.” Collaborators want to be asked for permission before any interaction with their territories and bodies and for their laws also to be respected, which is a radically different approach from current national legislation on consultation. We envision collaborators’ requirements as the praxis of “intercultural respect” instead of “mutual respect,” and “asking permission” instead of “consultation.”

Co-developing an Originary methodological approach with Asheninka and Yine Peoples

The Asheninka and Yine Peoples are ancestral societies who have occupied the Amazon since pre-Hispanic times (Chavarría, Rummenhöller, and Moore Citation2020; Veber Citation2009). Academics classify both Peoples as part of the Arawak linguistic family and their territories along the riversides (Yine) and foothills (Asheninka) are mostly located in the central and south eastern Peruvian Amazon (Espinosa Citation2016; Killick Citation2008; Sarmiento Barletti Citation2016a; Opas Citation2014; Smith Bisso Citation2020). Asheninka and Yine social institutions are based on the Native Community and the school and their everyday life gravitates around kinship relations (Gow Citation2020). Some of their historical struggles have been around the rubber boom and the correrías (capture and sale of individuals to rubber tappers as cheap labour) in the nineteenth and beginning of twentieth centuries, the Peruvian internal armed conflict, habilitación (debt peonage system – a complex economic relationship with logging and loggers), and expansion of the transnational extractivist developments during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries (Castillo Citation2010; Sarmiento Barletti Citation2016b; Espinosa Citation2016; Smith Bisso Citation2020).

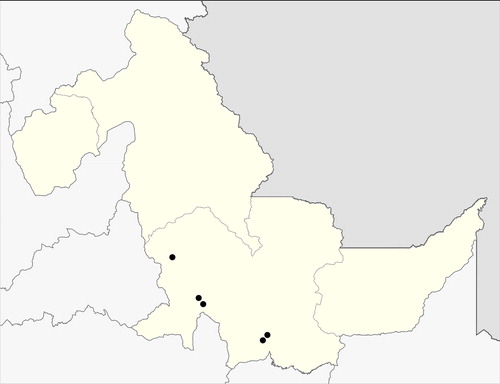

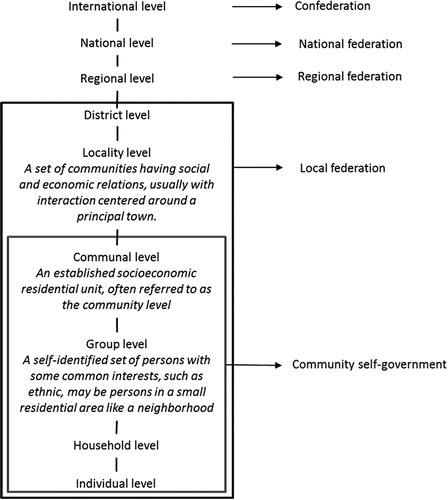

The Asheninka and Yine have a multi-level self-government system (). Originary federations were introduced in the Peruvian Amazon around the 1960s as a strategy to defend their way of life and territories to subsequently be incorporated into their self-government system (Chirif and García Citation2011; Espinosa Citation2009b). The federational political organization follows geographical and ethnic characteristics at the local, regional, national, and international level. It is understood that Originary federation representatives are spokespersons of their constituents, the communities, and the higher decision-making body is the assembly where community members are gathered (Vasquez Fernandez Citation2015). Asheninka and Yine life is profoundly intertwined with the forest and their own well-being depends on the health of those forests and their relationships with them (Varese, Apffel-Marglin, and Rumrrill Citation2013).

Figure 1. Levels of Originary self-government (Vasquez Fernandez Citation2015, 9) (adapted from Uphoff, 1986).

Amazonian Originary Peoples are dynamic societies engaged in constant processes of interaction, reflection, and decision-making about their surroundings, as well as tension, negotiation, agreement, and conflict with hegemonic praxes that come from the outside. This includes the terms used to identify Amazonian Peoples. During conversations with communities in Atalaya Province, it became apparent over time that several Originary individuals in Atalaya opted to employ for general self-identification Pueblo Originario or Originary People (in English) after the preferred name of their People, such as Yine or Asheninka (Vasquez-Fernandez and Ruiz Zevallos 2019). One of the co-researchers, Maria Shuñaqui, shared:

I feel insulted by that word “indígena,” I personally feel that way – and I respect my other friends [who use it]. And I also share the voice of a group of young people (men and women) and we feel like this … I know that it [indigenous] appears in many documents. It also appears [in terms like] campa or piro. But those [terms] have been western impositions. I wanted this space to share with you that I feel insulted. I feel like this when they call me indígena. I feel good when they call me Pueblo Originario. I am from the Asheninka Pueblo Originario, I think they are synonymous [Originario and indígena] and, if they are indeed synonymous, we feel good, I feel good when they call me Pueblo Originario (ONAMIAP-FEMIPA event “Mujeres indígenas, acceso a derechos y defensa de los bosques,” Atalaya 2020).

Terms such as “india,” “indígena,” “originaria” come from outside. During deconstructing, re-constructing, and meaning-making processes, Originary individuals and collectives in Atalaya explored which term in the hegemonic language (or autonym) better represented their identity. Our methodological approach is informed by these self-empowered processes of exploration, as well as the politics of hegemonic and subaltern paradigm encounters. Here we use the term paradigm to denote the set of assumptions related to ontology, epistemology, methodology, and axiology (Gavilán Pinto 2011; Creswell 1998; Wilson 2001). Paradigms might have multiple connections and influences with, to, and from other paradigms. Paradigms tend to be messy, fluid, contingent, uncertain, dynamic, and with fuzzy borders (Schmitter 2016). Each paradigm draws from different transcendental structures, each being informed by specific linguistic, discursive, physiological (including the technological extensions to human physiology), historical, cultural, political, institutional, economical, and sociological frameworks (Catren 2017).

The strategy to co-conduct this collaborative project builds on a previous (2012-2015) methodological approach co-developed with Asheninka and Yine Peoples (Vasquez-Fernandez et al. Citation2018). The pluri-cultural research team carried out this project at the invitation of Asheninka and Yine community members. After receiving the invite, the team engaged in extensive iterative dialogue with community members and federation representatives to understand what the project’s focus should be and how the research process should unfold. The team was commissioned to co-design, co-conduct, co-produce, co-publish, and co-mobilise an investigation, for which the regional federation Unión Regional de los Pueblos Indígenas de la Amazonía de la Provincia de Atalaya (URPIA) granted the main writer (Andrea) permission to access Originary territories. During 2015-2020 the main writer travelled to Lima, then to Atalaya (the capital of the province of Atalaya) by charter flight, taking small boats to each community to join collaborators and the rest of the research team to co-conduct the project. She spent around fourteen months in total with the communities over this six-year period.

The overall project methodology comprised four different stages: (1) preliminary meetings including communal assemblies and strategic meetings; (2) preparatory meetings that were mostly with the reseach team and federations; (3) content development including communal assemblies, conversational interviews, and group sessions that were both gender-based and mixed gatherings; and (4) mobilization of knowledges, work which is ongoing and transversal to other stages of the project. The central approach to interactions is storywork, where the storyteller, the story itself and the listener interact to generate knowledge with a strong social purpose (Archibald Citation2008). The research team listened to collaborators during numerous preliminary meetings. Initial meetings were with federation representatives and five communal assemblies in each of the collaborator communities to confirm the invitation made to Andrea and to define the research topic. The collaborating communities were identified by the federation representatives and their constituents. The five communities are in Diobamba (Tahuanía district); Chicosa and Boca Cocani (Raimondi district); Bufeo Pozo and Nueva Unión (Sepahua district) (). All are in the Atalaya Province, Ucayali Region, in the Peruvian central east Amazon.

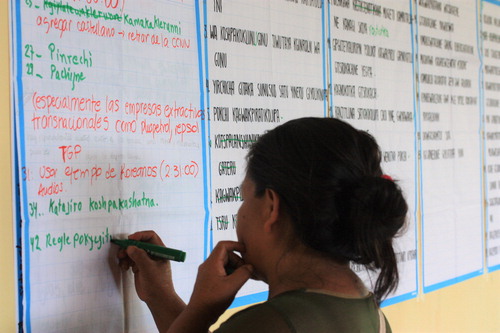

After listening to members’ current concerns and desired futures in each of the communities, the research team met again to draft and present the community-based suggestions to federation representatives. The research topic was agreed between federation and constituent communities and later communicated to the research team. Dozens of preparatory meetings were conducted to co-design the research questions and methodology. During the content development stage 150 collaborators shared their testimonies, opinions, and stories either individually or collectively. Fifteen group sessions (both mixed and gender-based) were then held employing performative narratives. Storyboards were developed with community collaborators, leaders, and federation representatives to answer the main research questions (). Each group session was concluded with shared meals which, at the suggestion of federations, were purchased in the communities to support their local economies. The co-created and articulated knowledges were analysed qualitatively by the research team using Nvivo12, and through both face-to-face and remote conversational sessions.

Figure 3. Group session, co-researcher Maria Shuñaqui using the storyboard method in the Asheninka language to ignite collaborators’ memories about Asheninka respect and disrespect, Diobamba 2020.

The research team members also have stories, which continuously inform our methodological approach and relationships. Andrea was inspired by the stories shared by her father about of her grandfather, Elías Vásquez who used to hunt in their territory in Ayacucho (central Andes) and was an informant and Quechua-Spanish interpreter for an anthropologist from the United States. Yet while Elías Vásquez had shared his knowledge with the researcher for a number or years, his voice and knowledge were made invisible in the researcher’s publications. Working with people like Andrea’s grandfather this collaborative project has sought to implement ways to address such power asymmetries in the co-design of research that works “with” research collaborators instead of “on” objects or subjects of research. Following conversations with collaborators, we have respected the choices of those who want to share their names. Some mentioned that they do not want to be an “X” on a paper. They wanted to use their own voice; a voice that belongs to someone – someone with a name. Although there are many more collaborators who shared testimonies and knowledge that have contributed to the research, we have identified the persons whose testimonies appear in this article and who wanted to be identified. On delicate subjects, the person’s name has not been made visible so as not to expose them.

Amazonian research team members are co-authors of this paper and their stories are also interwoven in the research. Maria is an Asheninka investigator, a leader, and an intercultural bilingual educator. She is a single mother and proactive member in her community. She is a former member of Tahuanía municipality council and prior to that she was the Vice-President of the Indigenous Organization of the Tahuanía District (OIDIT). Miriam is the President of the Indigenous Women’s Federation of Atalaya Province (FEMIPA). She is a dedicated mother and fervent women’s rights defender. She has been chief in her community numerous times. Miriam and Maria were key figures in the process to achieve legal recognition of the Asheninka alphabet. Judith and Raúl are wife and husband, Yine leaders, and active community members in their community. Raul is a bilingual teacher, and an influential elder in his community. Judith is a medicine woman and a caretaker (). Both complement each other contributing to the well-being of their community as well as to multilevel initiatives for development of intercultural educational material in Yine.

Figure 4. Group session, co-investigator Judith Canayo registering collaborators’ examples of Yine respect and disrespect in the Yine language, Bufeo Pozo 2020.

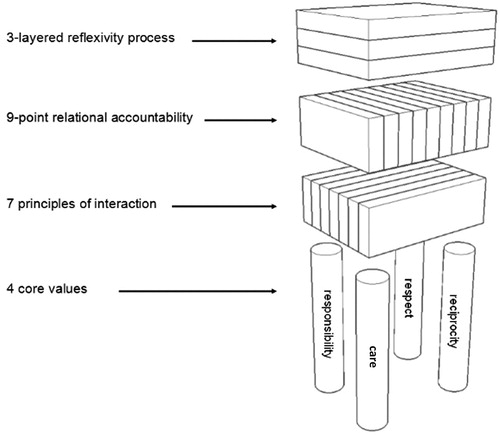

The methodology’s main elements are four core values, seven principles of interaction, a three-layered process of reflexivity, and a nine-point relational accountability protocol () (Vasquez-Fernandez et al. Citation2018). Our four core values of reciprocity, respect, responsibility, and care, are represented as pillars which support the seven interaction principles: (1) Cariño (love) toward Originary Peoples; (2) Compliance with recognised Originary structures and protocols; (3) Centring Originary knowledges, science, wisdom, and intellect in the study; (4) Flexibility and adaptation to collaborators’ agendas, spaces, time, languages, and activities; (5) Listening and waiting for collaborators to provide answers; (6) Facilitating collaborators’ processes to express their views, which implies asking rather than telling; and (7) Recognizing, with words and actions, that community members and federation officials are the experts of their own realities (Vasquez-Fernandez et al. Citation2018, 731).

Multi-layered reflexivity is important in our relationships, including self-reflexivity, intra-research team reflexivity, and collective reflexivity processes with collaborators (Nicholls Citation2009). Originary and western ethics protocols were braided in this pluri-paradigmatic enterprise. However, our endeavour is not neutral nor unbiased. To address colonial legacies and power asymmetries we centred on Originary protocols. To go beyond a fixed in time consent for the research, a nine-point relational accountability protocol was implemented. This is an ongoing relational process co-developed following collaborators’ paradigms and protocols for respectful engagements.

Some Originary perspectives on “respect” for persons

“Respect” comes from the Latin word respectus, meaning consideration and regard (Salazar 2019). For western ethical, moral, and political philosophy, the “person,” an agent capable of rational and moral functioning, is at the centre of the praxis of respect (Cranor Citation1975; Farley Citation2018). The Kantian idea “that all persons should be treated with respect simply because they are persons” (Dillon Citation2018, 2) has enduring influence in western moral philosophy (Buss Citation1999; Darwall Citation1977; Dillon Citation2015; Downie and Telfer Citation2021). This respect-for-persons interprets “persons” as autonomous, conscious, and rational beings with the capacity of moral choice, who, regardless of merit, are worthy of respect (Darwall Citation2013; Dillon 2014; Hill Citation2000c). Kant was specific about who a “person” could be. However, this narrow definition has been extended over time to include women, children, persons with mental disabilities, and Originary Peoples, who are now considered agents with intrinsic value and as deserving of respect (Dillon Citation2018). Indeed, the definition of personhood has been stretched beyond the human, and for the modern globalised legal system a company is recognised as a legal person, with many of the legal privileges and liabilities of a human being (or natural person) (Pietrzykowski Citation2018). Nature is also increasingly being recognized as a legal person in some countries including Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia and New Zealand (Dancer Citation2021). Respect for persons is promoted globally as the ethical guideline for any type of interactions in modern societies. Yet, in Asheninka and Yine Peoples’ paradigms, “person” has its own meaning. During our research we explored the question: who is a “person” for them?

In both western and Originary perspectives, respect is a means to maintain or achieve social harmony and peace with oneself and with others, the latter being challenging in pluri-cultural spaces. Yet, “persons” deserving of respect in Originary Amazonian contexts, have a broader meaning than is recognised in Roman-Germanic legal practice in Peru. Originary Amazonian Peoples do not find their concepts and practices of personhood reflected in the Peruvian or the dominant global legal system. For Asheninka and Yine Peoples, certain animals, plants, spirits (Madres and Dueños), and encantados (enchanted beings) can have the status of “person.” Community members referred to the encantados as non-human, non-vegetable, non-animal, and not necessarily like the wind (spirits). These are ambiguous entities and some take different shapes to deceive human beings. For the Asheninka People they may include the Amijari, Korinto, Janaete, and Peyari. The places where some of these entities live are sacred places -pashiwaka or sakatsiri ashitawori, in Yine and Asheninka languages respectively- and are in the monte (forest) or the cerro (hill). For example, a Shipibo Amazonian Originary student spoke of the importance of her medicine in facing the current COVID-19 pandemic: “plants take care of us. Plants are persons” (Rojas Sinti Citation2020, sec. 1:44:34). This was a common statement also among Yine community members:

We respect medicinal plants by asking for permission -and speaking to them as a person- to heal us. Some of our plants are toé [Brugmansia suaveolens], abuta [Abuta spp.], pájaro bobo [Tessaria integrifolia R.&P], catahua [Hura crepitans L.], shihuahuaco [Dipteryx spp.] and chiric sanango [Brunfelsia spp.]Footnote2 (Group session, Bufeo Pozo, 2020).

Similarly, Asheninka community members state: “We ask [the plants] for their power and wisdom to heal” (Group session, Gabriel Montes, Robinson Torres, and Eriko Velasquez 2020). Trees like lopuna colorada (Ceiba spp.), mango (Mangifera indica) or tornillo (Cedrelinga catenaeformis Ducke) also have an Ashitawori, a Madre (mother) or Dueño (owner), which is like a spirit who takes care of or inhabits the plant. If human beings want to benefit from the plant’s curative powers or from the timber, as a respectful behaviour they need to añanatziro (converse) with the Madre or Dueño and ask for permission, providing the motive for the request. A community member describes the very moment of the politics of the relationship:

[The tree] is spoken to. It seems as if we are talking [to a] person [but] there is nothing, there is only wood there… and they are asked… “I want wood, [so I can have money] to get dressed” or “I need to build my house” (Conversational interview, Amalia Coronado, 2020).

Elías Velasquez, an Asheninka elder, shared a story about three powerful sheripiari (Asheninka medical doctors) who together were invincible (). They drew their wisdom from three powerful trees who shared their healing gift with them to help the asheeninkaFootnote3 (people).

Figure 6. "The three powerful sheripiari." Text on the image: “The three trees are respected” (in English).

The inter-being-relationality between persons beyond the human (Kohn Citation2013) plays a central role in the politics of respect in the Amazon (Vasquez-Fernandez and Ahenakew Citation2020). Respectful protocols are applied internally in Asheninka and Yine realities and are expected to be fulfilled by external agents. Outsiders need to ask for permission before entering Asheninka or Yine communities. The person or organisation should coordinate with the Originary correspondent federation and be granted a visa-type document after explaining the purpose and the duration of the visit as well as who the visitors will be. Upon arrival at the community the person or group needs to present this document to the communal authority and introduce themselves. If everything is in order, the authority will decide and inform community members. Authorities may make a call through the communal speaker or through the vocales (who spread community-relevant messages house to house or by speaker) to convene the communal assembly (Conversational interview, community members, Bufeo Pozo, 2019). The communal assembly is the highest decision-making body in current Originary Amazonian self-government systems and makes the final verdict about transcendental and everyday life issues.

These relational norms or respectful protocols are not necessarily written down in reglamentos (bylaws) or statutes, but they are widely agreed upon and practiced when community members are self-empowered to do so. The following example illustrates how these processes of respect and asking permission work in practice. A logging company was interested in doing business with a Yine community and despite protocols of respect, the businessperson appeared in the communal assembly with a ready-to-sign contract and marketed the great possibility for jobs and economic benefits from logging in their communities. Community members shared how the community responded:

“Sir, you are the owner of your money and we are the owners of our resources. Therefore, if we want, we will give them to you, if not, you can go away with your money, no problem. We are not asking you to come (…)” We rejected them. That is what we have already lived, that is the experience lived already (Conversational interview, community members, Atalaya, 2017).

Logging and other industries that profit from extracting richness may provide good dividends to a local community initially, but disproportionate weight is given to economic gain. Under such contracts Originary Peoples’ territories and their bodies have been exposed to exploitation, with contamination and disillusionment remaining long after the money has run out.

Yine community members shared:

Atalayan fishermen are disrespectful when they come to extract commercial fish and leave the non-commercial ones, [which we also consume], to rot. They shouldn’t come to fish in our area, they should ask as for permission. If they want to do so [fishing], they [should] leave a percentage of the fish caught in the community. Furthermore, most of them do not even have authorization from the fisheries ministry (Group session, Nueva Unión, 2020).

Contemporary community respectful protocols use innovative ancient, as well as modern, and post-modern discursive and political tools toward envisioning self-determined desired futures. According to Parks, community protocols are avenues to challenge power asymmetries at local, national and international levels and a tool for attaining just benefit-sharing (Parks Citation2018). In Asheninka and Yine communities, community respectful protocols are tools, first of self-government and self-determination, and second to share benefits with outsider proponents, provided they are aligned with communities’ desired futures.

In the community respectful protocols framework, community members could also be offenders and face the consequences of their actions. The Madre or Dueño can get upset if their respectful protocol was not fulfilled. The Madre can kutipar the disrespectful being who hurt her protégée. The term kutipar is related to the Quechuan term kutimuyFootnote4 from the Andes, which means regresa “return” or “get back” (Personal conversation, Rolando Vásquez, Lima, 2020), a type of reciprocity. The influence and usage of Quechua language in the Amazon is prominent, which helps us understand the politics of these relationships in the Amazon (Varese Citation2016; Greene Citation2006).

[Kutipar] is the expression of the act of responding to another act of praise or offence, being more accentuated in the act of offence. [The offended] has no other way to respond than with the same firmness. It is a way of claiming and defending one’s own interests and surroundings, which is not always understood. The norms or laws that are dictated have a wide scope and equally compliance can even be harmful to the Originary Peoples (Personal conversation, Máximo Flores, Lima, 2020).

In a conversation with an Asheninka family, a mother explains the respectful behaviours that they (as a family) expect from others and she equates it to the respectful behaviours that Madres expect from human beings when they enter the monte, their home.

Those plants are plants that have a Madre who takes care of them. It is just like our home, if someone comes and enters our house and they take our clothes, we get upset. If a dad or a mom passes by there [the Madre’s home], the Madre reacts, the Dueño gets mad and that's why the children get sick (Conversational interview, Martha Pascual, Boca Cocani, 2020).

Some of the repercussions of disrespectful behaviours and attitudes can affect vulnerable family members including babies and children, generate disease or even cause the death of the offender. So why respect someone that might kutiparte, hurt you?

They are beings who deserve to be respected. [In addition,] without them we would not have existed. It is like a chain. Because before we did not know the pills and there are plants that are very effective and are beings that respond. From their reaction [the balance continues]. They should continue to exist. But they are already disappearing due to the noise, the machines, and big sounds. It was well balanced. For example, let’s say Maria asks for three trees and [the Dueño] gives them to her, but those greedy do not ask. They see a mahogany manchal [cluster] and they cut everything. Then, her Madre reacts. We call these places sacred places. These beings hinder [the depredation]. It is part of the balance (Personal conversation, Maria Shuñaqui, Atalaya, 2020).

The politics of respectful relationships between persons who consider paradigms beyond their own will diverge from those who believe that their own paradigm is unique, univocal, and compulsory. One Asheninka teacher shared that, “the population has been humiliated,” while another community member said, “[w]e do not want other people to come and walk over or trample us,” and specified that “[t]he central government (…) does not know our problems and does not respect us” (Communal assembly, Fermín and Wilmer, Boca Cocani, 2016). Such Asheninka and Yine reports of disrespect are not suspended in a void. To reach a comprehensive understanding of Asheninka and Yine Peoples’ concerns and desired futures, and their vision for a collective articulation of “respectful” relationships between them and external agents, it is important to situate these in historical context and a decolonial theoretical analysis of disrespectful attitudes towards Originary Peoples embedded in coloniality and modernity.

The modernity/coloniality theoretical approach: disrespectful relationships

Using a decolonial theoretical approach that has emerged from where the collaborators’ communities are located, Abiayala or so-called Latin America (Del Valle Escalante Citation2018), we place our research processes, co-created and articulated knowledges and our relationships in a long genealogy of past and present colonial disrespectful attitudes and behaviours toward Originary Peoples. The decolonial lens provided by the Southern theoretical concept of modernity/coloniality of “mak[ing] visible what is invisible” brings to the conventional eye the systematic disrespectful attitudes and behaviours toward Originary Peoples in Peru (Mignolo and Wannamaker Citation2016, 2).

The colonization of Abiayala in the fifteenth century involved the control and domination of Originary territories and bodies to the advantage of a European minority (Quijano Citation2007). When the conquistadors arrived, colonization was operationalized through the rhetoric of necessity for the slavery of African and Originary Peoples and the dispossession of Originary territories to carry out the “salvation” of our souls (Chirif Citation2017; Williams Citation1994; Hanke Citation1959). Quijano argues that despite the independence and formation of new nation-states, relationships continue to be framed by domination: “the colonization of the imagination of the dominated,” called coloniality (Citation2007, p. 169).

The current dominant western modernity paradigm emerged between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries (Santos Citation2020). Modernity is presented as ultimate “salvation” as we, in Abiayala, are seen –through the colonial lens– as uncivilized, uneducated, underdeveloped/least developed/developing, poor, and/or needy. Currently, modernity is implemented through the rhetoric of necessity of development and progress, which mono-paradigmatic and homogenizing tendencies “destroy[ing] as it proceeds, undermin[ing] as it builds, attack[ing] the environment and mak[ing] war on indigenous cultures” (Mitcham Citation1995, 324; Santos Citation2020). According to Santos, modernity has internal forces which are in constant tension: modern regulation and modern emancipation. The former striving for the stability of institutions, norms, and practices and the latter aspiring for a “good society” and a “good order” calling instead for challenging the status quo. When a new stability is achieved, the “good order” becomes “order,” the “good society” becomes “society” and the process of tension between forces starts again with new emancipatory struggles; no final settlement is achieved between both forces (Santos Citation2020). Mignolo also argues that from the initial invasion of Abiayala to the present time, two strategies are employed. During early colonization it was salvation (through Christianity and civilization) and novelty (based on the benefits of the Renaissance). Now, strategies continue to be salvation (through development/modernity/progress), and novelty (based on the benefits of technology and the free market) (Mignolo Citation2009, 2016).

The confluence between coloniality and modernity is not accidental, coloniality is decisively implicated in the constitution of modernity (Quijano Citation2007). The modernity/coloniality approach recognizes the praxis of modernity/progress/development as dominant euro-western narratives that have been historically disrespectful toward Originary Peoples in Abiayala. Displaying modernity as the shiny front, coloniality is its unnoticed constitutive counterpart. Coloniality is the quiet side that crawls behind the dazzling bling-bling of modernity. In other words, coloniality, or the Colonial Matrix of Power (CMP), as Mignolo conceptualizes it, is the engine behind the rhetoric of modernity (Mignolo Citation2009; Citation2007). The concept of CMP emerged in Abiayala at the intersection of public and academic realms to describe a multilevel, inter-relational, and dynamic structure that spatially and temporally connects the colonizer and the colonized (Radcliffe Citation2015).

The CMP perpetuates and reinvents itself through two foundational pillars and four axes (Mignolo Citation2009). The first pillar is the racial classification in which some human beings are disposable (Hanke Citation1959) and racially, aesthetically (Kant Citation1960) and intellectually inferior (Chirif Citation2017). The second pillar is the superiority of white men (but not white women) as the conscious, autonomous, and rational beings, who are “ends in themselves” and worthy of respect (Kant, quoted in Darwall Citation2013):

The fact that man is aware of an ego-concept raises him infinitely above all other creatures living on earth. Because of this, he is a person; and by virtue of this oneness of consciousness, he remains one and the same person despite all the vicissitudes which may befall him. He is a being who, by reason of his pre-eminence and dignity, is wholly different from things, such as the irrational animals whom he can master and rule at will (Kant Citation1978, 9).

Kantian foundational ideas spread through the modern world, cementing what today is the effect of those teachings. The two pillars are the base of the four axes that make up the CMP as identified by Mignolo (Citation2009, 49):

Management and control of subjectivities (for example, Christian and secular education, yesterday and today, museums and universities, media and advertising today).

Management and control of authority (for example, viceroyalties in the Americas, British authority in India, US army, [and] Politbureau in the Soviet Union).

Management and control of economy (for example, by reinvesting of the surplus engendered by massive appropriation of land in America and Africa; massive exploitation of labour starting with the slave-trade; by foreign debts through the creation of economic institutions such as World Bank and International Monetary Fund).

Management and control of knowledge (for example, theology and the invention of international law that set up a geo-political order of knowledge founded on European epistemic and aesthetic principles that legitimised the disqualifications over the centuries of non-European knowledge and non-Europeans’ aesthetic standards, from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment and from the Enlightenment to neo-liberal globalisation; [and western] philosophy). (Translated by the main writer)

The CMP structure is implemented through managing and controlling the subjectivities, authority, economy, and knowledge that later determine the policies, programs, projects and “the normal.” The coloniality/modernity structure clashes with realities such as those of Amazonian Peoples. Understanding the CMP structure, its constitutive elements, and position in time and space is useful for identifying the strategies that disallow the Asheninka and Yine Peoples from being respected by external agents. It also provides a realistic general framework to inform and transform dominant ideas of “respect” and “mutual respect” respectively.

Consultation law and mutual respect in Peru: they make you sign and then, they say "it’s already consulted"

The Prior Consultation Law (PCL) is an illustration of the coloniality/modernity of today, evoking a sort of déjà-vu of the 1514 Requerimiento – an official document from the Spanish crown that was required by law to be read to Originary Peoples to “inform” them they will be subjects of the crown and to accept Christianity. If they refused to accept it, the crown would wage war against them, their lands and richness would be taken, and their bodies enslaved (Hanke Citation1959). Originary Peoples “could not legitimately ignore this ‘legal condition’ from then on, even if they had understood nothing of what had been read to (against) them” (Santos Citation2020, 294).

Peru’s ratification of the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention No. 169 (ILO C169) in 1994, enshrined the principle of “respect” in national law. “With the ratification, the convention is integrated into national legislation and it is up to national states to generate the regulatory framework that includes the precepts contained in the Convention” (Salazar-Xirinachs 2016, 11). Two decades later, after the Baguazo, the government was pushed to start “consulting” Originary Peoples. The deadly aftermath of the Baguazo generated national and international outrage, which pressured the government to regulate and implement tools to (better) interact with Originary Peoples (Urteaga-Crovetto Citation2018). The PCL was passed in 2011 as the result of the Originary decades-long movement demanding that they be able to make decisions that concern their own futures and for the state to follow socially just and respectful protocols (Espinosa Citation2017; Comisión Especial Citation2009).

With the implementation of the PCL, Amazonian Peoples expected that their struggles against the imposition of development projects, programs and policies would be addressed, respectful attitudes would be embraced, and violence diminished. However, Originary Peoples’ paradigms have historically been excluded from public policy making (Chino Dahua Citation2020; Surrallés, Espinosa, and Jabin Citation2016), and the PCL is a good example of this. Although ignited by the Baguazo as a bottom-up demand to shape public policies, as Urteaga-Crovetto observes, “the right to consultation has been transformed into a complex ensemble of legal practices and techniques geared towards procedimentalization, that captures indigenous self-determination within the realm of the state law alien to indigenous peoples” (2018, 20).

The elaboration process for the PCL as well as its content were disappointing for the Originary movement (AIDESEP Citation2012). Despite the efforts of Amazonian Peoples to have a voice in their futures, article 23.1 of the PCL’s Regulation confirms that the government institution that deals with the topic in consultation would have the final word in any consultation process, reducing the “consultation” process to a mere informative act or potentially a bargaining tool, which would depend on the leverage power of the Originary People (Torres Citation2016). Community members also expressed their disappointment at the PCL process:

[The petroleros, those who work around the business of extracting oil] look for their strategy and they make you sign and then they say, "it’s already consulted." It is already authorized for them to work. Look, that is wrong. If you don't want to sign, [then,] it is a “No.” That's all, you don't want them to work, so there is nothing to do! (Group session, Mayer Sanchez, Diobamba, 2020).

In 2014 Asheninka and Yine Peoples became subject to consultation for oil and gas exploration and exploitation. The state company PeruPetro conducted the consultation process for the approval of blocks 175 and 189 in the Ucayali Basin. Yet despite the fact that the consultation process for the blocks was ongoing, PeruPetro had already offered Asheninka and Yine traditional territories to international bidders (Miro-Quesada Citation2014). During our research in a communal general assembly, current communal authorities and community members expressed surprise, frustration, and disappointment to learn, for the very first time, that their community lands had been confirmed for exploitation without their permission six years ago during a consultation process that they were neither aware of, nor participated in (Communal assembly, Boca Cocani, 2020).

Additionally, Asheninka delegates who had participated in the consultation process stated that they entered the process without their own lawyer or technical adviser, while PeruPetro had brought their own lawyer, a technical specialist and a translator. Delegates indicated a number of concerns, including: (1) they did not fully understand what was said during the process because Spanish is not necessarily their first language, the Spanish dialect in Amazonian communities is distinct from those in the cities, and they were unfamiliar with the technical terms used; (2) there were inconsistencies in the registration process, where communities had been listed as consulted even though consultation processes had never happened; (3) they argued that despite their concerns about the incompatibility between their desired futures and oil exploitation and exploration, they were persuaded and in certain cases obligated to sign the “Plan de Consulta” (Consultation Plan); and (4) the title of the signed document was Consultation Plan, trusting that since it was a “plan” there would be additional occasions for participation prior to the consulted measure being approved.

Hermano [brother] I have opposed, but what has he [PeruPetro representative] said? “if you do not sign, I will not pay your return [to your community]” And I did not have money… How are we going to come back to our communities again? (Group session, accredited delegate, Boca Cocani, 2020).

The PCL calls for “mutual respect” between the Peruvian state and Originary Peoples, as well as respect for the different Originary Peoples’ cultures, norms, and the environment (Ministerio de Cultura Citation2013). However, the prior consultation implementation process in Peru is far from being an instrument to prevent and resolve violent conflicts over dominant perspectives of development (Urteaga-Crovetto Citation2018; Jara 2020). Instead, it re-enacts colonization by further encroaching upon Originary territories and livelihoods:

At the same time, the state promotes the consultation and does not respect the Originario (…). They must respect! It is going to happen at any time also a Baguazo. A conflict between us (Group session, community member, Diobamba, 2020).

Mutual respect is the common modern approach to address disagreements or conflicts that are the result of diverse cultural, political, and religious engagements (Brown Citation2000). Mutual respect goes beyond tolerance and considers constant self-reflection, openness, and continued interaction “in the hope of eventually arriving at improved understandings and closer agreement” (Macedo Citation1999, 9). Hill urges us to commit “to certain attitudes about cultural diversity” (Hill Citation2000b, 87) (emphasis added). Individuals could find:

an intermediate ground between a dogmatic moralism that would impose all of our values upon everyone and an uncritical relativism that would accept anything, no matter how cruel, in the name of diversity (Hill Citation2000a, para. 63).

Yet, all operate within our own (individual and collective) transcendental structures, which define the lenses used at me moment of delineate “mutual respect.” If power asymmetries are not intentionally challenged, we will be unable to respect other’s worldviews. “Mutual respect” in the PCL dismisses the pluri-meaning of respect in pluricultural realities. This brings to the surface the unseen side of modernity in three main ways: (1) it unveils the structural asymmetry, the uneven terrain in which western and non-western relationships occur; (2) it highlights the misleading equivalence between nationhood, ethnicity, and statehood; (3) it reinforces the extent to which the conventional legal order ignores Originary legal traditions and cultures (Santos Citation2020). In fact, Fish argues that “‘mutual respect’ should be renamed ‘mutual self-congratulation,’ since it will not be extended beyond the circle of those who already feel comfortable with one another” (Fish Citation1999, 95). To go beyond limited modern/colonial forms of politics and law-making that define current approaches of “mutual respect,” it is necessary to know how “respect” is understood in practical terms by cultural and ethnic groups in Peru, and how “intercultural respect” could be practiced between external agents and Originary Peoples.

The paradigm-encounter frame and intercultural respect

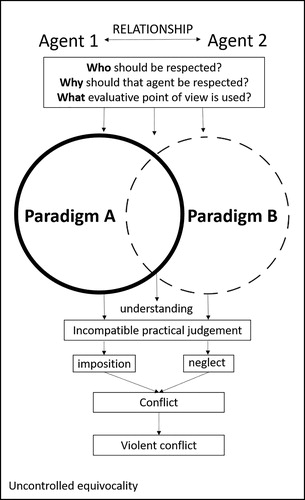

The paradigmatic platform from which judgment is made determines who should be respected, why they should be respected, and what is the evaluative point of view in the judgement (Hill Citation2000a). Based on our theoretical and empirical research, we propose a paradigm-encounter frame to explain the politics and negotiation of relationships between external agents and Originary Peoples in the Peruvian Amazon (). Respect or disrespect are expressions of agency generated in these complex relationships (Martin Citation2008; Cranor Citation1975; Dillon 2014). Let us say two persons have different paradigms. There are some areas of conjunction and disjunction between these different paradigms. The interaction between persons drawing from different paradigms might be denoted by uncontrolled equivocality (Viveiros De Castro Citation2004), incommensurable clashes of divergent worlds (Strengers Citation2018). In other words, even when parties (A and B) speak the same language (Spanish) and use the same words “respect” and “person,” they may not be referring to the same representation of the terms. Paradigm B is represented by an intermittent line denoting an entrenched asymmetry of power in the relationship. If the definition of who, why, and what is established by drawing from the conjunction areas between the paradigms, there is a great possibility that there will be an understanding. If not, an “incompatible practical judgment” arises (Cranor Citation1975, 319). Building on the modernity/coloniality framework in this relationship, if Agent 1 answers these questions (who, what and why to respect), Agent 1’s ideas and actions will be imposed on Agent 2. And if Agent 2 answers the questions, it is likely to be unnoticed or deliberately ignored. Consequently Agent 2’s expressions are neglected because of the historical power asymmetry existing in the relationship. There is also the possibility that through the Colonial Matrix of Power (CMP) Agent 2 could supress their expressions resulting also in the imposition of Agent 1 over Agent 2. Either way, the interaction unfolds in conflict, which could trigger violence.

Figure 7. B = Amazonian (Asheninka and Yine) Originary paradigm and A = Euro-western and westernized paradigm.

The current mutual respect approach operates within the CMP threatening Agent 2’s norms, lifestyles, and self-determined Originary economies. During our conversations, collaborators demanded respectful attitudes and behaviours from outsiders that follow their perspectives of respect:

We have always been told what to do and how to do things, now we want to investigate how the western [and westernised] society should behave when interacting with us and our territories (Preparatory meeting, Linder Sebastian, Atalaya 2016).

Asheninka and Yine community members and leaders have shown that there is neglect and disinterest from external agents to understand and practice what the research team is calling “intercultural respect.” “Intercultural respect” refers to practices that are based on care, curiosity, unsettling instances, and acknowledging that the only commonality might be the uncommon and diverge aspects in pluri-paradigmatical interactions. Our results show that intercultural respect is a means to achieve and maintain peace, tranquillity, and harmony (kametha ajaeke, pomjiru, and sumak kawsay in Asheninka, Yine and Quechua respectively). Furthermore, practicing intercultural respect could help in preventing or addressing violent conflicts that emerge from asymmetrical encounters. This could also provide the foundation for an interdependent, hyperdynamic, and polycentric interlegality, albeit one which operates in uneven social and legal terrains (Santos Citation2020; Proulx Citation2005).

As a result of the six years of collaborative research with Asheninka and Yine Peoples between 2015 and 2020, we propose ten guiding (dynamic) principles for intercultural respect (). Intercultural respect might imply re-enforcing Originary own norms. Collaborators mentioned their “law” should be respected just as they respect Peruvian law, implying a dialogue rather than imposition of legal orders. Operationalization of intercultural respect promotes instances where Asheninka and Yine Peoples weave new relationships between their legal orders and other local, national, and global legal orders: the very expression of interlegality (Santos Citation2020). Thus, interlegality becomes a way to counteract the modern/coloniality inertia, pushing toward political evolutions.

Table 1. Based on conversations with Asheninka and Yine Peoples between 2015 and 2020.

External and internal compliance with the ten principles for intercultural respect is challenging. As previously discussed, community members could also be offenders. Nevertheless, while community members are accountable to the communal assembly and state authorities, external agents might not. For example, PeruPetro is liable under corporate law to the oil and gas exploration and exploitation corporations, which are their clients, but it is not accountable to Peruvian citizens. Strategies of external compliance under the guiding principles for intercultural respect include: interpersonal call out (for example, community members telling municipal engineers to ask for permission before taking fruits from the plants in their community); collective call out (for example, wake-up call from the communal assembly to NGOs, private, and public representatives if community respectful protocols are not fulfilled); and institutional call out (for example, when Originary federations formally call out disrespectful attitudes and behaviours at the local, municipal, national, or international level). These strategies demanding compliance with intercultural respect principles are not necessarily exclusive and can be combined.

There are major incompatibilities between intercultural respect and current praxis under the PCL. The latter promotes a type of respect (mutual respect) that does not consider “other” praxes of respect, which in turn generates disrespectful attitudes and behaviours. For instance, in consultation processes Originary real-life desired futures, challenges, and concerns have often been overlooked (Flemmer and Schilling-Vacaflor Citation2016). The consulted are persuaded to approve the consulted measure “no matter what, so that it is no longer an obstacle for the company” (Jara 2020, para. 3; Merino Citation2018). The right to consent can be overruled (Urteaga-Crovetto Citation2018). Consent could also be misinterpreted in legal contexts, which some define as “non-supersedable authority to deny access” (Personal conversation, Bjorn Stime, Vancouver, 2020) or as collaborators have expressed: by “asking for permission” which considers “yes,” “no,” “maybe,” or “not now” possibilities. The UN Special Rapporteur, Tendayi Achiume, addresses the issue:

No should mean no: permanent sovereignty over natural resources should be understood to include the right of peoples, especially those most negatively affected by the extractivism economy, to say no to extractivism, its processes and its logics (Achiume Citation2019, 20).

Conclusion

Through dominant euro-western legal narratives “mutual respect” has become an important principle toward attaining harmony and peace in contemporary pluri-cultural societies. The Prior Consultation Law (PCL) is the legal structure mediating the relationships between Amazonian Originary Peoples and external agents. Originary Peoples expected the PCL could address their long struggles for “respect.” However, although state and suprastate structures promote “mutual respect,” their premises disrespect existent Amazonian normative orders. Since definitions, indicators, and limits of “mutual respect” remain western-centred, an “incompatible practical judgement” (Cranor Citation1975, 319) has emerged because Originary Peoples draw their perspectives of “respect” from distinct (non-dominant) paradigmatic platforms. As a result, conflicts have arisen unleashing in some cases violent clashes between Originary Peoples and external agents.

The testimonies are overwhelming (): there are historical and current disrespectful attitudes and behaviours from external agents (including state, NGOs, extractive industries, researchers, and tourists) toward Amazonian Originary Peoples. The collaborative work with Asheninka and Yine Peoples demonstrates that the praxis of “mutual respect” operates within the Colonial Matrix of Power (CMP) as the dominant ideas, practices, and sensibilities that come from western and westernized societies are imposed on their societies. The euro-western paradigm pretends to monopolize knowledge production, methodology, and methods that shape public policies (Santos Citation2020). The “mutual respect” approach creates an illusion of an equitable relationship –imposing one understanding of respect and controlling who is in or out of the relationship. Amazonian Originary Peoples demand that public policies should more closely reflect their dynamic existing social realities (Radcliffe Citation2015, 8). Indeed, the presumption that there is one praxis of respect has lingered from the sixteenth century to the present day (Proyecto Andino de Tecnologías Campesinas Citation2008).

Amazonian Originary Peoples are articulating counter arguments and stories that envision “intercultural respect” instead. The ten principles for intercultural respect that we propose, could benefit contemporary societies in multiple ways: expanding notions of respect and personhood beyond the human; acting as an emancipatory challenge to the CMP; enriching political and legal fields by generating different normative linkages (such as community protocols) between infrastate and suprastate structures; and proposing alternative approaches to address modern problems by pushing the evolution of law and politics, for example “asking for permission” instead of “consulting.” Intercultural respect recognizes the coexistence of legal orders operating in diverse time-space structures and scenarios of interlegality. While mutual respect attempts to homogenize societies re-enacting colonization (Santos Citation2020). In paradigmatically diverse settings, it is necessary to extend and diversify our understandings of “respect” to prevent and address violent conflicts. Through our collaborative work with the Asheninka and Yine Peoples, Originary Peoples aspire to inform and transform public policies, so that extensions and variations on “respect” practices continue, and both law and praxis become (more) receptive to the diverse realities in the Amazon and beyond.

Disclaimer

The views express herein do not necessarily represent those of IDRC or its Board of Governors, or The Bene Endowment Fund or its contributors.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to Helen Dancer for her invaluable suggestions and support. For insights into the Quechua terms we are indebted to Andrea’s father Rolando Vásquez and uncle Máximo Flores, Ayacuchan Quechua speakers who kindly shared their knowledge. We are thankful to Pedro Favarón, Chonon Bensho, and Carlos Reynel for sharing their knowledge, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their feedback, which enriched this article.

In memory of a dear friend, co-researcher, and co-author Judith Canayo Otto deceased on March 15th, 2021 prior the publication of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Reglamento de La Ley No 29785, Ley Del Derecho a La Consulta Previa a Los Pueblos Indígenas u Originarios Reconocido En El Convenio 169 de La Organización Internacional Del Trabajo (OIT). El Peruano, Normas Legales 463587- 463595 Martes 3 de Abril 2012.

2 We recognize the reductionist risk of using scientific names to refer to such complex and multifaceted beings, who were pigeonholed by the standardized Linnaean methodology of naming them. Although this does not convey their existence in both worlds, such usage should be considered as an effort to communicate to western readers.

3 Although in the Asheninka language normalization process delegates agreed to write this word with one “e” (asheninka), collaborating Asheninka communities argued that the correct way of writing this word is with double “e” (asheeninka). Additionally, it was agreed that the name of their People will continue to be written with one “e.” We respect this agreement.

4 The Originary Quechua (Runasimi or peoples’s language) suffered a series of adaptations when Spaniards brought the Latin alphabet. Other phonetically accepted ways to write this term are cutimuy or q’timuy.

References

- Achiume, T. 2019. Global Extractivism and Racial Equality: Report of the Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance. A/HRC/41/54. New York: United Nations General Assembly.

- AIDESEP. 2012. AIDESEP Rechaza el Reglamento de Consulta Previa y Lamenta Decisión del Gobierno Lima: AIDESEP. https://www.servindi.org/actualidad/62444.

- Alfaro, A. 2020. Desafío de Los Pueblos Indígenas de Las Comunidades de Las Cuatro Cuentas (Loreto) Frente Al COVID-19. YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jBh134vqzUo.

- Archibald, J. 2008. Indigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body, and Spirit. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Brown, C. 2000. “Cultural Diversity and International Political Theory: From the Requirement to ‘Mutual Respect’.” Review of International Studies 26 (2): 199–213. doi:10.1017/S0260210500001996.

- Buss, S. 1999. “Respect for Persons.” Canadian Journal of Philosophy 29 (4): 517–550. doi:10.1080/00455091.1999.10715990.

- Castillo, B. H. 2010. Despojo Territorial, Conflicto Social y Exterminio – Pueblos Indígenas En Situación de Aislamiento, Contacto Esporádico y Contacto Inicial de La Amazonía Peruana. Informe 9. Copenhague: IWGIA. http://www.iwgia.org/iwgia_files_publications_files/0459_INFORME_9.pdf

- Chirif, A., and P. García. 2011. “Organizaciones Indígenas de La Amazonía Peruana. Logros y Desafíos.” In Movimientos Indígenas En América Latina: Resistencia y Nuevos Modelos de Integración, edited by A. C. Betancur, 106–132. Copenhague: IWGIA.

- Chaumeil, J.-P. 2014. “Liderazgo En Movimiento: Participación Política Indígena En La Amazonía Peruana.” In De La Política Indígena: Perú y Bolivia, edited by Georges Lomné, 21–40. Lima: IEFA, IEP.

- Chavarría, M. C., K. Rummenhöller and T. Moore, eds. 2020. Madre De Dios: Refugio de Pueblos Originarios. Lima: USAID.

- Chino Dahua, A. 2020. Desafío de Los Pueblos Indígenas de Las Comunidades de Las Cuatro Cuentas (Loreto) Frente Al COVID-19. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jBh134vqzUo&t=7187s.

- Chirif, A. 2017. Después Del Caucho. Lima: Lluvia Editores.

- Comisión Especial. 2009. Informe Final de La Comisión Especial Para Analizar Los Sucesos de Bagua. Lima. http://www.servindi.org/pdf/Informe_final_de_la_commision_especial_sucesos_de_agua.pdf

- Cranor, C. 1975. “Toward a Theory of Respect for Persons.” American Philosophical Quarterly 12 (4): 309–319.

- Dancer, H. 2021. “Harmony with Nature: Towards a New Deep Legal Pluralism.” The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law. doi:10.1080/07329113.2020.1845503.

- Darwall, S. 2013. “Kant on Respect, Dignity, and the Duty of Respect.” In Honor, History and Relationship: Essays in Second-Persona Ethics II, edited by S. Darwall, 1–30. Connecticut: University Press Scholarship.

- Darwall, S. 1977. “Two Kinds of Respect.” Ethics 88 (1): 36–49. doi:10.1086/292054.

- Dillon, R. S. 2015. “Humility, Arrogance, and Self-Respect in Kant and Hill.” In Reason, Value, and Respect: Kantian Themes from the Philosophy of Thomas E. Hill, Jr., edited by M. Timmons and R. N. Johnson, 1–34. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Dillon, R. S. 2018. “Respect.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/respect/

- Downie, R., and E. Telfer. 2021. Respect for Persons: A Philosophical Analysis of the Moral, Political and Religious Idea of the Supreme Worth of the Individual Person. Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Espinosa, O. 2016. “Los Asháninkas y La Violencia de Las Correrías Durante y Después de La Época Del Caucho.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’études andines 45 (45 (1): 137–155. doi:10.4000/bifea.7891.

- Espinosa, O. 2017. “No Queremos Inclusión, Queremos Respeto: Los Pueblos Indígenas Amazónicos y Sus Demandas de Reconocimiento, Autonomía y Ciudadanía Intercultural.” In En Busca de Reconocimiento: Reflexiones Desde El Perú Diverso, edited by M. E. Ulfe and R. Trinidad, 119–136. Lima: PUCP.

- Espinosa, O. 2009a. “¿Salvajes Opuestos Al Progreso?: Aproximaciones Históricas y Antropológicas a Las Movilizaciones Indígenas En La Amazonía Peruana.” Anthropologica 27 (27): 123–168.

- Espinosa, O. 2009b. “Las Organizaciones Indígenas de La Amazonía y Sus Reivindicaciones.” Argumentos: Revista de Análisis y Crítica, 3 July https://argumentos-historico.iep.org.pe/articulos/las-organizaciones-indigenas-de-la-amazonia-y-sus-reivindicaciones/

- Farley, M. A. 2018. “A Feminist Version of Respect for Persons.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 9 (1): 183–198.

- Fish, S. 1999. “Mutual Respect as a Devise of Exclusion.” In Deliberative Politics: Essays on Democracy and Disagreement, edited by S. Macedo, 88–102. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Flemmer, R., and A. Schilling-Vacaflor. 2016. “Unfulfilled Promises of the Consultation Approach: The Limits to Effective Indigenous Participation in Bolivia’s and Peru’s Extractive Industries.” Third World Quarterly 37 (1): 172–188. doi:10.1080/01436597.2015.1092867.

- Gamboa, C., and S. Snoeck. 2012. Análisis Crítico de La Consulta Previa En El Perú: Informes Sobre El Proceso de Reglamentación de La Ley de Consulta y Del Reglamento. Lima: Grupo de Trabajo sobre Pueblos Indígenas de la Coordinadora Nacional de Derechos Humanos https://www.corteidh.or.cr/tablas/r31020.pdf

- Gow, P. 2020. De Sangre Mezclada: Parentesco e Historia en la Amazonía Peruana. Lima: Fondo Editorial UCSS.

- Greene, S. 2006. “Getting over the Andes: The Geo-Eco-Politics of Indigenous Movements in Peru’s Twenty-First Century Inca Empire.” Journal of Latin American Studies 38 (2): 327–354. doi:10.1017/S0022216X06000733.

- Hanke, L. 1959. The Spanish Struggle for Justice in the Conquest of America. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Hill, T. E., Jr. 2000a. “Basic Respect and Cultural Diversity.” In Respect, Pluralism, and Justice: Kantian Perspectives, 59–86. Padstow: Oxford University Press.

- Hill, T. E., Jr. 2000b. “Must Respect Be Erned?” In Respect, Pluralism, and Justice: Kantian Perspectives, 87–118. Padstow: Oxford University Press.

- Hill, T. E., Jr. 2000c. Respect, Pluralism and Justice. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kant, I. 1960. Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and the Sublime. Berkeley: University of California.

- Kant, I. 1978. Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View. Translated by V. L. Dowdell. Revised and edited by H. H. Rudnick. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Killick, E. 2008. “Creating Community: Land Titling, Education, and Settlement Formation among the Ashéninka of Peruvian Amazonia.” Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 13 (1): 22–47. doi:10.1111/j.1548-7180.2008.00003.x.

- Kohn, E. 2013. How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology beyond the Human. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- López, F. 2009. Amazon for Sale. Peru: IWGIA. https://vimeo.com/11007631.

- Macedo, S. 1999. “Deliberative Politics.” In Deliberative Politics: Essays on Democracy and Disagreement, edited by S. Macedo, 1–30. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Martin, K. L. 2008. Please Knock before You Enter: Aboriginal Regulation of Outsiders and the Implications for Researchers. Brisbane: Post Pressed.

- Merino, R. 2018. “Law and Politics of Indigenous Self-Determination: The Meaning of the Right to Prior Consultation.” In Indigenous Peoples as Subjects of International Law, edited by I. Watson, 120–140. Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Mignolo, W. 2007. “Coloniality: The Darker Side of Modernity.” Cultural Studies 21 (2-3): 449–449. doi:10.1080/09502380601162647.

- Mignolo, W. 2009. “La Colonialidad: La Cara Oculta de La Modernidad.” In Modernologías: Artistas Contemporáneos Investigan La Modernidad y El Modernismo. Barcelona In Breitwieser, Sabine Klinger, Cornelia Mignolo, Walter D Eds. pp. 39-49. Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Barcelona.

- Mignolo, W., and W. H. Wannamaker. 2016. ““Global Coloniality and the World Disorder: Decoloniality after Decolonization and Dewesternization after the Cold War.” Paper presented at the 13th Rhodes World Public Forum “Dialogue of Civilizations. https://www.academia.edu/21395973/Global_Coloniality_and_the_World_Disorder_Decoloniality_after_Decolonization_and_Dewesternization_after_the_Cold_War

- Ministerio de Cultura. 2013. Consulta a Los Pueblos Indígenas: Guía Metodológica. Ley Del Derecho a La Consulta Previa a Los Pueblos Indígenas u Originarios, Reconociedo En El Convenio No 169. Lima: Ministerio de Cultura. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/90577/108172/F-1993885983/PER90577.pdf

- Mitcham, C. 1995. “The Concept of Sustainable Development: Its Origins and Ambivalence.” Technology in Society 17 (3): 311–326. doi:10.1016/0160-791X(95)00008-F.

- Miro-Quesada, O. 2014. “Hydrocarbon Investment Opportunities in Peru.” PeruPetro. https://www.perupetro.com.pe/wps/wcm/connect/corporativo/b310900b-cada-4843-9d50-c73af18e9089/LONDRES%252B140304_Presentaci%25C3%25B3n%252BAPPEX%252B

- Nicholls, R. 2009. “Research and Indigenous Participation: Critical Reflexive Methods.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 12 (2): 117–126. doi:10.1080/13645570902727698.

- Opas, M. 2014. “Ambigüedad Epistemológica y Moral En El Cosmos Social de Los Yine.” Anthropologica 32: 167–189.

- Parks, L. 2018. “Challenging Power from the Bottom up? Community Protocols, Benefit-Sharing, and the Challenge of Dominant Discourses.” Geoforum 88: 87–95. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.11.011.

- Pietrzykowski, T. 2018. Personhood beyond Humanism: Animals, Chimeras, Autonomous Agents and the Law. Katowice: Springer.

- Proulx, C. 2005. “Blending Justice: Interlegality and the Incorporation of Aboriginal Justice into the Formal Canadian Justice System.” The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 37 (51): 79–109. doi:10.1080/07329113.2005.10756588.

- Proyecto Andino de Tecnologías Campesinas. 2008. Epistemologías En La Educación Intercultural: Memorias Del I Taller Sobre Educación Intercultural y Epistemologías Emergentes. Lima: PRATEC.

- Quijano, A. 2007. “Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality.” Cultural Studies 21 (2-3): 168–178. doi:10.1080/09502380601164353.

- Radcliffe, S. A. ed. 2015. Dilemmas of Difference: Indigenous Women and the Limits of Postcolonial Development Policy. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Rojas Sinti, S. 2020. Seminario GAA-GAMSI COVID-19 y Amazonía Indígena. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Jbpe3ieR_o

- Santos, B. de Sousa. 2020. Toward a New Legal Common Sense: Law, Globalization, and Emancipation. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sarmiento Barletti, J. P. 2016a. “La Comunidad En Los Tiempos de La Comunidad: Bienestar En Las Comunidades Nativas Asháninkas.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’études andines 45 (45 (1): 157–172. doi:10.4000/bifea.7904.

- Sarmiento Barletti, J. P. 2016b. “The Angry Earth: Wellbeing, Place, and Extractivism in the Amazon.” Anthropology in Action 23 (3): 43–53. doi:10.1063/1.2756072.

- Smith Bisso, A. 2020. “El Pueblos Indígena Yine Del Perú.” In Madre De Dios: Refugio de Los Pueblos Originarios, edited by M. C. Chavarría Mendoza, K. Rummenhöller, and T. Moore, 289–314. Lima: USAID.

- Strengers, I. 2018. “The Challenge of Ontological Politics.” In A World of Many Worlds, edited by Marisol de la Cadena and Mario Blaser, 83–111. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Surrallés, A., O. Espinosa, and D. Jabin, eds. 2016. Apus, Caciques y Presidentes: Estado y Política Indígena Amazónica En Los Países Andinos. Lima: IWGIA.

- Torres, M. 2016. “Prior Consultation and Extractivism: Evidence from Latin America.” PhD thesis., Washington DC: American University.

- Urteaga-Crovetto, P. 2018. “Implementation of the Right to Prior Consultation in the Andean Countries. A Comparative Perspective.” The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 50 (1): 7–30. doi:10.1080/07329113.2018.1435616.

- Valdivia, F. 2009. La Traversía de Chumpi. Teleandes Producciones. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AH8kPS_HVsc

- Valle Escalante, E. Del. 2018. “De América Latina a Abiayala. Hacia Una Indigeneidad Global.” Revista Transas: Letras y Artes de America Latina. https://www.revistatransas.com/2018/12/17/hacia-una-indigenidad-global/

- Varese, S. 2016. “Relations between the Andes and the Upper Amazon.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History, 1–18. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.62.

- Varese, S., F. Apffel-Marglin, and R. Rumrrill. 2013. Selva Vida: De La Destrucción de La Amazonía Al Paradigma de La Regeneración, edited by IWGIA and UNAM. Lima: Casa de América.

- Vasquez Fernandez, A. M. 2015. “Indigenous Federations in the Peruvian Amazon: Perspectives from the Ashéninka and Yine-Yami Peoples.” Masters' thesis., The University of British Columbia. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

- Vasquez-Fernandez, A. M., and C. Ahenakew. 2020. “Resurgence of Relationality: Reflections on Decolonizing and Indigenizing ‘Sustainable Development’.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 43: 65–70.

- Vasquez-Fernandez, A. M., R. Hajjar, M. I. Shuñaqui Sangama, R. S. Lizardo, M. Pérez Pinedo, J. L. Innes, and R. A. Kozak. 2018. “Co-Creating and Decolonizing a Methodology Using Indigenist Approaches: Alliance with the Asheninka and Yine-Yami Peoples of the Peruvian Amazon.” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 17 (3): 720–779.

- Veber, H., ed. 2009. Hisotorias Para Nuestro Futuro: Yontantsi Ashi Otsipaniki. Lima: IWGIA.

- Viveiros De Castro, E. 2004. “Perspectival Anthropology and the Method of Controlled Equivocation.” Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America 2 (1): 3–22.

- Williams, E. 1994. Capitalism and Slavery. 2nd ed. North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press.