ABSTRACT

Many people living with substance use disorder require multiple types of support to reduce use and mitigate harms. Recovery community centers have emerged alongside formal substance use treatment and mutual self-help groups as another option to support peoples’ recovery. Research on the helpfulness of recovery community centers is limited. The purpose of this paper was to describe what Staff and Member Facilitators perceived as helpful components of a recovery community center. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 10 Staff and six Member Facilitators of a recovery community center, Recovery Café, in Seattle, Washington. Qualitative interviews were analyzed via grounded theory approach. Eleven themes emerged on the helpful components of Recovery Café, including tangible/infrastructure and intangible/experiential strengths. Three themes related to opportunities for program improvement. Many themes on the helpful components were consistent with prior research on recovery community centers and other supports for recovery. Findings provide insight into potential active ingredients and mechanisms of recovery community centers and highlight the potential role of recovery capital. Additional research is needed to test these components to improve the understanding of if and how recovery community centers work to support people with substance use disorders in recovery.

Introduction

An estimated 20 million people in the United States currently have a substance use disorder (SUD; SAMHSA, Citation2019). SUDs result in negative consequences to physical and mental health, relationships, and communities. People with an SUD are more likely to experience comorbid medical and mental health disorders, relationship problems, disruptions in employment, and legal involvement (Bahorik, Satre, Kline-Simon, Weisner, & Campbell, Citation2017; Dickey, Normand, Weiss, Drake, & Azeni, Citation2002; Franco et al., Citation2019; Rhee & Rosenheck, Citation2019). Just under four million individuals each year seek support, including formal detoxification, inpatient, residential, and/or outpatient SUD treatment, as well as community-based self-help groups, such as Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous (SAMHSA, Citation2019). For others, particularly those with more complex and severe disorders, additional or different support may be needed for sustained recovery management.

Recovery community centers (RCCs) have emerged among other grassroot recovery community organizations to address the needs of people with SUD that may be missed by formal treatment programs and mutual self-help groups (Haberle et al., Citation2014; Parkin, Citation2016; White, Kelly, & Roth, Citation2012). Rather than focusing on substance use alone, RCCs offer a more holistic approach to recovery, including individual, community, and cultural resources. This comprehensive approach to recovery is consistent with both NIAAA and NIDA’s recommendations to address SUD through a combination of treatment and service options for each person (NIAAA, Citation2021; NIDA, N. I. on D. A, Citation2019). Services offered at RCCs include support group meetings, assistance with basic needs and social services (e.g., employment assistance, family support services, housing assistance, education assistance), and facilitation of substance-free recreational services (e.g., sober social activities; Kelly et al., Citation2020). Similar places and environments for recovery have been in existence in Europe (e.g., “recovery cafés”; Parkin, Citation2016; Shortt, Rhynas, & Holloway, Citation2017). Although there has been no formal comparison of RCCs in North America and recovery cafés in Europe, they appear to share similar principles: stemming from grassroot origins, emphasizing a physical space for people to go, and offering resources for recovery (Parkin, Citation2016; Shortt et al., Citation2017).

RCCs are purported to strengthen long-term recovery through the accumulation of recovery capital and access to social support for recovery, which directly affect self-esteem, quality of life, and psychological distress (Kelly et al., Citation2020). Recovery capital is a combination of internal (“personal”) and external (“social”) resources that help individuals to endure and tolerate stressors, particularly those experienced in early recovery, and can be sustained over a longer period of time (Cloud & Granfield, Citation2008). Social support has long been identified as an important component to recovery from SUD (Beattie & Longabaugh, Citation1999; Groh, Jason, Davis, Olson, & Ferrari, Citation2007; Stevens, Jason, Ram, & Light, Citation2015). Social support can help people with SUD by providing instrumental resources (housing, transportation), emotional support, abstinence-specific support, and can mitigate the stress response that is impaired by chronic SUD (Hostinar, Sullivan, & Gunnar, Citation2014). Consistent with this theoretical model of RCCs, Kelly and colleagues (Kelly et al., Citation2020) found that increased use of RCCs was positively related to recovery capital and length of recovery, which were associated with improvements in self-esteem, quality of life, and psychological distress. Social support for recovery (e.g., having social network members who are abstinent) was not found to be associated between increased use of RCCs and improvements in self-esteem, quality of life, and psychological distress (Kelly et al., Citation2020). The authors noted that this theoretical model was an initial attempt at understanding the helpfulness of RCCs, especially as RCCs are fast-growing across the country (Kelly et al., Citation2020). Further investigation is needed to better expand and develop the theoretical model of RCCs and their benefits to participants.

For the current study, interviews were conducted with Staff and Member Facilitators of Recovery Café, an RCC in Seattle, Washington, to better understand the helpful and less helpful components and gather feedback on methods prior to doing an evaluation (e.g., important components to test, recruitment, assessment domains). Results from the feedback on evaluation methods will not be reported here. Thus, the objective of this study was to describe what Staff and Member Facilitators found helpful and less helpful about attending this RCC.

Materials and methods

Study overview

Data came from an evaluation of Recovery Café that was planned to be carried out over two phases. Phase 1 consisted of focus groups with Recovery Café Staff and one-on-one interviews with current Member Facilitators to develop methods to examine the effectiveness of the Recovery Café model. Phase 2 was initially planned to recruit new Members to test if the Recovery Café model improves outcomes, including substance use, recovery status, healthcare utilization, and arrests. However, it was decided in 2022 not to continue Phase 2 activities due to the ongoing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Café activities (e.g., indoor eating capacity restrictions). Only results for Phase 1 activities will be presented. Study procedures for Phase 1 were approved by the institutional review board at the University of Washington.

Setting

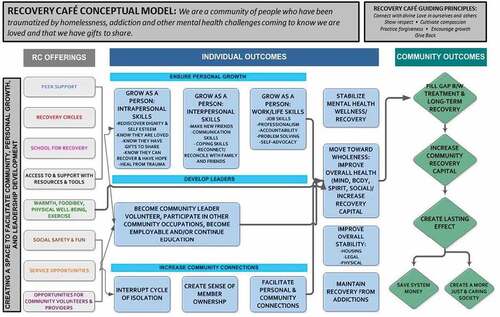

Recovery Café was founded in 2003 in Seattle, Washington, to address the unmet needs of individuals with lived experience of trauma, homelessness, alcohol and other drug use disorders, and/or other mental health challenges (). Although the Recovery Café in Seattle shares a namesake with recovery cafés in Europe, they do not originate directly from there (https://recoverycafe.org/about/history/). In 2016, Recovery Café launched the Recovery Café Network, which provides training and support to other organizations implementing the Recovery Café Network model in their communities. There are currently 49 Recovery Cafés in the United States and Canada.

Figure 1. Internally developed conceptual model of Recovery Café. Figure used with permission from Recovery Café, Seattle, WA, 2021. ©2021 Recovery Café. All rights reserved.

Prior to COVID-19 restrictions, Recovery Cafés are generally open 7 days a week, during daytime and early evening hours (8 am–8p m). They have an open, drop-in Café area that serves hot food and beverages, as well as classrooms for scheduled groups. Groups and activities include, but are not limited to, community meals, walking club, yoga classes, and Recovery Circles. Recovery Circles are led by trained peer Member Facilitators and offer non-clinical recovery support. Recovery support in Circles often takes the form of check-in, goal-setting, some educational component, and resource information sharing or feedback. Recovery Café also hosts events/celebrations, such as Open Mic Night, where Members can stand up to sing, recite poetry, and speak.

Staff are not in a formal treatment provider role. Member Facilitators are current Members who self-identify as being in recovery from a substance use or other mental health disorder. Individuals become Members by completing an initial orientation, and agreeing to be alcohol and drug free for 24 hours before coming to the Recovery Café, contribute to Recovery Café activities, and attend a weekly Recovery Circle. All study recruitment was from the Seattle flagship location.

Participants

The inclusion criterion for Recovery Café Staff was as follows: a) having worked at Recovery Café for at least 6 months. For example, newer Staff were not invited to participate. The inclusion criterion for Recovery Café Member Facilitators was as follows: a) being a current Member of Recovery Café, defined by the Recovery Café as having attended at least one Recovery Circle in the last 30 days. Operationally, Member Facilitators are not considered Staff as they are not on payroll. All Recovery Café Staff and Member Facilitators are over age 18.

Participants (N = 16) included 10 Staff across two focus groups (nine joined by video, one phone) and six Recovery Café Member Facilitators who completed interviews individually (three joined by video, three phone). Demographic characteristics of Staff and Member Facilitators are shown in . All Recovery Café Staff with direct client interactions participated in the focus groups. Most of the active Member Facilitators completed interviews (6 of 11 total active Member Facilitators).

Table 1. Demographic information

Data collection

Recruitment

Focus groups and individual interviews were conducted between March and May 2020. Staff were emailed by Recovery Café leadership (R.M.), who maintain contact information for their employees, and invited to participate in focus groups. Recruitment of current Members was initially planned to be done in-person at the Recovery Café. In response to COVID-19 restrictions, Recovery Café ceased all regular in-person group activities (including their day center/café) in March 2020. Only Recovery Café Members who were also Recovery Circle facilitators were invited to participate via phone and/or e-mail because they had already given permission to the Recovery Café to be contacted for non-service-related purposes.

Focus groups and individual interviews

Focus groups and interviews were semi-structured, up to 1 hour, conducted remotely, and recorded for audio only. Member Facilitator interviews were one-on-one to help ensure they felt comfortable in sharing responses. Member Facilitators were given the option to complete the interviews via video conferencing or by phone given COVID-19 precautions. All focus groups and interviews were conducted by the lead author (M.D.O.) and began with reviewing the consent form and getting verbal assent. Participants first answered questions on the perceived helpfulness of Recovery Café, then gave feedback on Phase 2 evaluation, and, lastly, provided basic demographic information. Questions and their wording were selected in collaboration with Recovery Café leadership to inform methods for the Phase 2 evaluation. Questions were as follows:

Just to get started, tell me about the Recovery Café.

What has been/was helpful about what Members/you get from the Recovery Café?

What has been not helpful about the Recovery Café?

What is something special about the Recovery Café that has been helpful for Members/you?

Prompts included the following: What do you mean by__? Can you tell me more about__? Can you give me an example of__? Can you tell me about a time when__? Questions with Staff were framed about what has been helpful for Members. Question 3 was asked only with Member Facilitators. Questions were open-ended in an attempt to allow participants to freely generate their own responses.

Demographic information collected included a) age range (20s, 30s, etc.), b) gender (male, female, transgender, other identity), c) ethnicity (yes/no Latino or Hispanic), d) race (American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Black/African American, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Island, White, multiracial), and e) length of time being a Staff or Member (<1 year, 1–3 years, 3–5 years, 5–10 years, >10 years). For Member Facilitators only, they also were asked for time in recovery (<1 year, 1–3 years, 3–5 years, 5–10 years, >10 years). Staff were not paid for their participation because they completed hours during approved work time. Member Facilitators were mailed or emailed a $25 gift card for participating.

Qualitative analysis

Interviews were transcribed and then reviewed to remove identifying information. Because one of the Staff focus groups was not recorded, detailed interviewer notes, including quotes, were analyzed. Dedoose Version 8.0.35 (Dedoose Version 9.0.17, Citation2021), an online application for storing and analyzing qualitative data, was used for thematic coding of data and reliability analyses. Data were analyzed using a grounded theory approach such that text data are systematically classified by content themes that emerge from the data rather than using a coding system based on theory or a priori hypotheses (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005; Krippendorff, Citation2018). This approach is helpful when there is no existing research basis for themes, such as in this case, because there are no studies explicitly on the helpful components of recovery community centers (only on how participation relates to outcomes). First, two authors (M.D.O. and A.N.) reviewed participant responses independently to generate a list of potential thematic codes that came directly from the data (i.e., not from the existing literature). Next, these authors discussed and reconciled their lists to develop an initial set of codes. These authors then engaged in an iterative process of double-coding a subset of transcriptions, discussing discrepancies, and refining the codes until overall good agreement was reached based on pooled Cohen’s kappa (kappa = 0.72; Landis & Koch, Citation1977) and good to excellent agreement was reached for most of the individual codes (intraclass correlations >0.60; Cicchetti, Citation1994). Only two codes had ICCs below the good range. Atmosphere agreement was fair (0.49) and operational improvements was poor (0.37), likely due to low frequency. The two authors then double-coded all participant responses with the refined codes, reviewed results, and resolved all remaining discrepancies in coding. Final results and codes were then discussed among all authors, which included leadership and Staff from Recovery Café (R.T. and R.M.). The authors discussed overarching themes, collapsed codes when appropriate, and identified prototypic responses for each theme.

Results

Fourteen themes were identified from the Staff and Member Facilitator interviews about what was and was not helpful about Recovery Café (see ). All themes emerged from both Staff and Member Facilitator interviews, except for Opportunities for Improvement, which only emerged from Member Facilitator interviews in the context of the “What has not been helpful?” question.

Table 2. Interview themes

Tangible/infrastructure strengths

Classes/Recovery Circles/Resources

Participants spoke about multiple ways that programming was helpful, including Recovery Circles, the variety in topics, ways that they supported recovery, offering sober social events, and opportunities to give back. Connection to internal and external resources more generally were also discussed in interviews and how these could be useful to people at various stages in their recovery. Another participant said, “So, the Recovery Café is just an amazing, amazing recovery haven that provides all kinds of resources for people anywhere in their recovery journeys.” The helpfulness of Recovery Café being open to a variety of people along a spectrum of recovery, including mental health and substance use, also emerged in overlapping themes, such as accepting/welcoming.

Food/meals

Food and meals through Recovery Café were noted as being helpful. In particular, participants talked about how food often would be what “brings people in” or was what the first thing people heard about Recovery Café. The quality of the food was noted by Member Facilitators (“the food is awesome”). Relatedly, the Staff discussed the care they put into preparing meals: “I think that the amount of care that we put into what we serve translates into feeling like being cared for directly … It’s Maslow’s hierarchy, right? You’ve got to meet those needs as they go up. But I think it starts with the meal.” Food/meals also overlapped when discussing other themes, including connectedness. For example, a Member Facilitator noted how “sitting down eating a meal with another individual just to be social” was beneficial. This opportunity to socialize over meals also helped people learn to interact with others.

Opportunities to contribute

Recovery Café has multiple instances where Members can contribute to daily chores and other functions, including leading Recovery Circles; these were noted as being helpful from Staff and Member Facilitators. One Member Facilitator discussed these opportunities, “The Café gives me a place to be able to offer that help, whether it’s doing chores, cleaning, chores around the Café … .” Similarly, Staff saw the ability to contribute anything as important, both to the functioning of the Café, but also to the individual, “I really like that model that there’s not one way to give back to the Café, no matter what you have to offer you have something to offer.” Opportunities to contribute overlapped with developing self-worth, such that being able to contribute and give back emerged as an important part of recovery and the value of Recovery Café.

Space (physical)

Having a physical space to go to “a warm place to sit during the day” that was safe and for people in recovery was mentioned as being helpful during interviews. One participant reported, “ … one of the things that you’ll find is the café is perhaps [the] best ‘dayroom’ around … There’s not a whole bunch of drug dealing and stuff like that going on that’s just so obvious and all of that.” Staff similarly felt that having the physical space was important for serving this population, “It’s a safe community space for people who may not have access to a safe community space outside of the café to some degree.” Space coincided with other themes, including food/meals and connectedness, such as having a place to go to have a meal and be with other people.

Staff

The warmth, “kindness,” and helpfulness of Staff emerged as important components of why Members went to and stayed at Recovery Café. Staff also talked about how the welcoming nature starts “at the top” with the executive Staff and this warmth and dedication contributed to Recovery Café’s ongoing mission and programming. One Staff said, “we’re talking about from the executive director on down, everybody is engaged in some way or form or fashion in their role. Like our program director she’s always abreast of what’s the best practice.” The benefits of Staff were brought up in the context of other themes, particularly accepting/welcoming and creating a positive atmosphere.

Intangible/experiential strengths

Accepting/welcoming

A common theme among both Staff and Member Facilitators was the notion of how Recovery Café accepts everyone from “all walks of life” and actively makes the Recovery Café a welcoming environment for people at any place in their recovery. As one Staff described: “When we talk about recovery you know it’s not just the drugs and the alcohol, we have this philosophy that people are in recovery from a lot of different factors, you know whether it be homelessness, mental health, trauma, whatever.” Both Staff and Member Facilitators also talked about how people are almost always welcomed back even after incidents at the café. For Members, Recovery Café can be one of the few places where people with SUD can go and not be stigmatized.

Atmosphere

Participants commented specifically on the helpfulness of the positive atmosphere at Recovery Café. This theme often overlapped with other codes, including space (physical), Staff, and being a place that is accepting/welcoming. For example, one Member Facilitator stated, “I would say the thing that makes the Recovery Café what it is by far is the Staff and the atmosphere that they set for the whole building.” Thus, conceptualizing the atmosphere of Recovery Café may have to be done in the context of where it is, who works there, and explicit efforts to make Members feel like they belong.

Connectedness

Being able to connect and meet other people was cited as being an important part of Recovery Café. Participants discussed connectedness with forming specific relationships with other Members, being around others more generally, and being a part of a community. One Member Facilitator said, “It helps me with anxiety, depression to be around people.” Another discussed how it helped with recovery, “[It] allowed my life to expand and to go out and do different things and go out with people who were clean and sober, which was something that was actually missing.” Connectedness is encouraged throughout the Recovery Café Classes, Recovery Circles, meals, and the dayroom setting all are structured to encourage Members and Staff to interact with each other. One Staff emphasized connectedness above other parts: “ … initially I think [food] definitely brings people in. But it’s that sense of community and love. The way we treat people with respect and dignity and just having just an opportunity to kind of be a part of community that’s ultimately what I think definitely keeps people a part of our Membership at the Recovery Café.”

Developing self-worth

Staff and Member Facilitators noted the benefits of developing their self-worth through volunteering for chores, working in the kitchen, and leading Recovery Circles. It was mentioned that these chances to give back were particularly helpful for people who have struggled in the past, “It helps me feel useful, which is a – that cannot be understated, the importance of that. Because being somebody who’s had struggles with mental health for decades, and being in the system – in the system [laughs] – and not being able to successfully continue to work, you know, to have a place where I feel like I’m contributing is so important. It’s so important.” Being able to contribute and develop self-worth instilled hope among Members and encouraged their recovery. Thus, Recovery Café’s offering of classes and Recovery Circles as well as opportunities to volunteer may lead to developing self-worth, which can help meet individuals’ long-term recovery needs.

Opportunities for personal growth

Having “opportunities to grow” and learning to be more positive were discussed by participants as being helpful components of Recovery Café. Relatedly, participants stated having a place to go where they could sit down and interact with a variety of people helped them in “learning how to be social,” which then was useful for “interacting with the public.” This personal growth was also instrumental in participants’ recovery. As one Member Facilitator noted, “What Recovery Café did was to offer me these new opportunities in my life to grow even more, and to expand my experiences and my possibilities for recovery.” This Member Facilitator’s experience is consistent with Recovery Café’s goals of offering a variety of opportunities and resources to people across multiple places in their recovery.

Space (structure to day)

In addition to having a physical space to go to (i.e., a dayroom), participants commented on the value of somewhere to go to add purpose to their day and help keep them busy. For example, one person said, “I mean it gave me – that start right there was to give me something to do where I was sitting home watching TV or staring out the window, maybe reading. So just to begin with was to have that one-hour a week structure when I had no structure.” Relatedly, it was noted that having a structure to the day that included other positive elements, such as food, social interaction, and the Recovery Circles, was beneficial.

Opportunities for improvement

Challenging staff interactions

When asked for something that has not been helpful, one participant said: “Sometimes when I would you know we’d have to work some things out too that I might not be happy about. Sometimes I tell Staff something and sometimes people will get emotional about it.” This was a report of a challenging Staff interaction; however, it also was paired with statement of understanding from the Member Facilitator: “I would have to sit there and realize, ‘Well they’re upset,’ but they’re upset about the situation that I just described and they’re concerned about it.”

Desire for more accountability

The most commonly reported opportunity for improvement was the potential need for additional accountability of Members. One participant stated, “I feel like sometimes there are situations where the cost-benefit has to be weighed out, and the cost-benefit for the Members as a whole needs to be weighed out. And, so, in some situations, I think it would be better not to give infinite chances to every person.” For Member Facilitators, it appeared that while there were benefits of allowing people to make mistakes, there may be instances where chances to return to the Café community have to be limited.

Operational improvements

Suggestions for operational improvements included opening a separate location in the north side of Seattle, offering additional training for Staff around mental health, providing additional medical treatments onsite, and offering mentoring programs.

Discussion

Fourteen themes emerged from interviews on the helpful components of Recovery Café. Many themes overlapped across the two strength categories, such that there were many tangible things that RCCs could offer that are helpful (e.g., food/meals, physical space), but it is also about creating a positive experience for Members (e.g., helping them feel accepted/welcomed). Developing self-worth and opportunities for personal growth came from classes/Recovery Circles/resources and opportunities to contribute, and may be important for recovery. These themes from Recovery Café interviews provide insights into theoretical and testable RCC models.

Recovery Café had an established model for their flagship location that was developed internally (). Recovery Café leadership (R.T. and R. M.) provided input on the naming, understanding, and description of themes that were conceptually similar. For example, opportunities to contribute was originally named volunteering by coders, but, after discussion, was renamed since it aligned with the existing model. Many other themes also were consistent with this model, including classes/Recovery Circles/resources (“Recovery Circles,” “access to resources”), space (“warmth”), and food/meals (“food/beverages”). Intangible/experiential strengths were consistent with Individual Outcomes from the original Recovery Café model, such as connectedness (“make new friends”). These results may serve as the foundation for future research on other RCCs.

Many findings were consistent with previous research by Kelly and colleagues (Kelly et al., Citation2020) and provided additional insight into how RCCs may support long-term recovery among people with SUDs. Overlapping variables between the study findings and the model by Kelly and colleagues were connectedness and social support for recovery, developing self-worth and self-esteem, and opportunities for personal growth and recovery capital (Kelly et al., Citation2020). Results from the interviews may highlight ways to expand the Kelly et al. model (Kelly et al., Citation2020), such as potential active ingredients of Recovery Café and other RCCs (), like tangible/infrastructure strengths. Longitudinal research on people participating in RCCs is needed to test the expanded model proposed here (), including how components relate temporally. It would be helpful to examine the impact of potential active ingredients of RCCs (e.g., classes, food, and opportunities to contribute) on other domains (e.g., self-esteem, quality of life, and psychological distress) as they relate to long-term recovery. This line of research could inform theories of recovery, such as the importance of recovery capital.

Figure 2. Expanded theoretical model of Kelly et al. (Citation2020) model based on study findings.

There also was a combination of themes that converged around the helpfulness of having a “Third Place” to go (): A place that is accepting/welcoming, has a positive atmosphere, is a physical location to go (space), and is a place to go to structure time in the day (space). In sociology, the Third Place has been described as “the benefits of the accrue from the utilization and personalization of places outside the workplace and the home” (Oldenburg & Brissett, Citation1982, pg. 265). Shortt and colleagues (Shortt et al., Citation2017) similarly highlighted the importance of having a space and environment for recovery from alcohol use disorder, even including the use of “third place.” Many people with SUDs may isolate because of disruptions in employment and relationships, to avoid triggers, and because they experience stigma in treatment and healthcare settings. Thus, having a Third Place to go that is welcoming may be especially helpful for people with SUDs, particularly in early recovery. The benefits of a Third Place may be even greater for people with SUDs when those places have multiple resources, such as connectedness with other sober people, food/meals, and classes/Recovery Circles/resources. Future studies should examine if and how the Third Place may play a role in the helpfulness of RCCs for people with SUD.

This study provided insights into how RCCs may help people with SUDs, but there are notable limitations. First, there was a small sample of Staff and Member Facilitators of Recovery Café that largely was due to in-person recruitment restrictions related to COVID-19. It may be that Members that do not facilitate Recovery Circles have different insights into what is helpful about Recovery Café. All participants came from one RCC, which further restricts how results may represent other RCCs around the country. For example, it may be that other RCCs do not offer food/meals or have more stringent policies about allowing Members to return. Alternatively, other RCCs may offer medication management services that are greatly needed, but are not offered at this location. Last, this study did not examine if the purported helpful components of Recovery Café related to Members’ outcomes. Thus, future research should test if and how the tangible/infrastructure and intangible/experiential strengths predict improvements in quality of life, long-term recovery, and other outcomes among RCC Members.

Conclusions

Findings from interviews with Staff and Member Facilitators from Recovery Café improved the understanding on how RCCs may be helpful for people with SUDs, as well as for those experiencing homelessness and mental health disorders. Many themes supported the accumulation of recovery capital as an important component of RCCs and the theory of recovery. Tangible/infrastructure strengths may be potential active ingredients of RCCs, such as classes/Recovery Circles/resource and food/meals. There may also be new components to consider in the theoretical model of RCCs, including the Third Place, somewhere people can go to have basic needs met (food, shelter/space), that is friendly and accepting, and may help connect them with other resources (classes). The results can inform future longitudinal research on RCCs, which is needed as RCCs continue to expand across the country.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Recovery Café, Seattle, Washington. The authors would like to thank David Coffey for his input on this manuscript and Laura Hamill for her contributions to the Recovery Café conceptual model. Thank you to Recovery Café staff and Members for their participation in the interviews.

Disclosure statement

Recovery Café leadership were involved in the study design, interpretation, and reviewing and offering edits of the report. Recovery Café staff did not make changes to study results. The authors have no other conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bahorik, A. L., Satre, D. D., Kline-Simon, A. H., Weisner, C. M., & Campbell, C. I. (2017). Alcohol, cannabis, and opioid use disorders, and disease burden in an integrated healthcare system. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 11(1), 3. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000260

- Beattie, M. C., & Longabaugh, R. (1999). General and alcohol-specific social support following treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 24(5), 593–606. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00120-8

- Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6(4), 284. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284

- Cloud, W., & Granfield, R. (2008). Conceptualizing recovery capital: Expansion of a theoretical construct. Substance Use and Misuse, 43(12–13), 1971–1986. doi:10.1080/10826080802289762

- Dedoose Version 9.0.17. (2021). Web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data (2021). Los Angeles, CA, USA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC. www.dedoose.com

- Dickey, B., Normand, S.-L. T., Weiss, R. D., Drake, R. E., & Azeni, H. (2002). Medical morbidity, mental illness, and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services, 53(7), 861–867. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.53.7.861

- Franco, S., Olfson, M., Wall, M. M., Wang, S., Hoertel, N., & Blanco, C. (2019). Shared and specific associations of substance use disorders on adverse outcomes: A national prospective study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 201, 212–219. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.003

- Groh, D. R., Jason, L. A., Davis, M. I., Olson, B. D., & Ferrari, J. R. (2007). Friends, family, and alcohol abuse: An examination of general and alcohol-specific social support. American Journal on Addictions, 16(1), 49–55. doi:10.1080/10550490601080084

- Haberle, B. J., Conway, S., Valentine, P., Evans, A. C., White, W. L., & Davidson, L. (2014). The recovery community center: A new model for volunteer peer support to promote recovery. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 9(3), 257–270. doi:10.1080/1556035X.2014.940769

- Hostinar, C. E., Sullivan, R. M., & Gunnar, M. R. (2014). Psychobiological mechanisms underlying the social buffering of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical axis: A review of animal models and human studies across development. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 256. doi:10.1037/a0032671

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

- Kelly, J. F., Fallah-Sohy, N., Vilsaint, C., Hoffman, L. A., Jason, L. A., Stout, R. L., … Hoeppner, B. B. (2020). New kid on the block: An investigation of the physical, operational, personnel, and service characteristics of recovery community centers in the United States. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 111(December2019), 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2019.12.009

- Kelly, J. F., Stout, R. L., Jason, L. A., Fallah-Sohy, N., Hoffman, L. A., & Hoeppner, B. B. (2020). One-stop shopping for recovery: An investigation of participant characteristics and benefits derived from U.S. Recovery community centers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 44(3), 711–721. doi:10.1111/acer.14281

- Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. California, United States: Sage publications.

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174. doi:10.2307/2529310

- NIAAA. (2021). Why do different people need different options? Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://alcoholtreatment.niaaa.nih.gov/what-to-know/different-people-different-options

- NIDA, N. I. on D. A. (2019). Treatment approaches for drug addiction. National Institutes of Health, Retrieved January 1–7, 2021, from https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/df_treatmentapproaches_1_2016.pdf

- Oldenburg, R., & Brissett, D. (1982). The third place. Qualitative Sociology, 5(4), 265–284. doi:10.1007/BF00986754

- Parkin, S. (2016). Salutogenesis: Contextualising place and space in the policies and politics of recovery from drug dependence. International Journal of Drug Policy, 33, 21–26. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.10.002

- Rhee, T. G., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2019). Association of current and past opioid use disorders with health-related quality of life and employment among US adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 199, 122–128. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.004

- SAMHSA. (2019). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publication No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54, 170, 51–58. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.042

- Shortt, N. K., Rhynas, S. J., & Holloway, A. (2017). Place and recovery from alcohol dependence: A journey through photovoice. Health & Place, 47, 147–155. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.08.008

- Stevens, E., Jason, L. A., Ram, D., & Light, J. (2015). Investigating social support and network relationships in substance use disorder recovery. Substance Abuse, 36(4), 396–399. doi:10.1080/08897077.2014.965870

- White, W. L., Kelly, J. F., & Roth, J. D. (2012). New addiction-recovery support institutions: Mobilizing support beyond professional addiction treatment and recovery mutual aid. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 7(2–4), 297–317. doi:10.1080/1556035X.2012.705719