ABSTRACT

Twenty-nine mental health support workers took part in an online-survey consisting of a vignette and scenarios to elicit information regarding their recovery perceptions and positive-risk taking approaches related to service-users with dual-diagnoses of mental illness and substance use disorder. Reflexive thematic analysis was used to analyze the survey-responses. Although the participants emphasized some aspects aligning with the recommended “recovery-oriented practice” approach, there was an overemphasis on reduced substance-use, aversive and overprotective approaches to positive risk-taking and a lack of emphasis on hope and the service-users’ strengths and abilities. It was concluded that there is a continuing need to implement recovery-oriented practice within mental health services.

Introduction

It has been widely acknowledged that substance use disorders (SUD) are increasingly prevalent in individuals with mental illnesses (Balhara et al., Citation2016; Crowe et al., Citation2013; Department of Health, Citation2011; Lee et al., Citation2010; Trull et al., Citation2018). It has been suggested that this co-occurrence may be the norm rather than an exception (Baldacchino, Citation2007; Crowe et al., Citation2013), and that approximately half of everyone with a mental illness will be diagnosed with a SUD at some point in their lifetime which is a three-time higher prevalence compared to the general population (Manuel et al., Citation2015). When these disorders are co-occurring, the term “dual diagnosis” tends to be used (Baldacchino, Citation2007; Crome et al., Citation2009; NICE, Citation2016, updated 2020). Dual diagnoses often involve a complex combination of high-level needs (Balhara et al., Citation2016; Department of Health, Citation2011; Evans-Lacko & Thornicroft, Citation2010; Roberts & Bell, Citation2013) and has been linked to several adverse outcomes, causing significant burden to the individual, their family, and the wider society (Crome et al., Citation2009; Gratz et al., Citation2008; Manuel et al., Citation2015).

The National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE, Citation2016, updated 2020) has acknowledged that there is a lack of research investigating recovery facilitators and barriers for individuals with dual diagnoses. It has however been stated that the “recovery-oriented practice” approach provides the best chance of recovery for both mental health conditions (Keet et al., Citation2019; Kenny et al., Citation2020; Leamy et al., Citation2016) and substance use disorders (Department of Health & Social Care, Citation2021) and aspects of this approach have been recommended in the support of individuals with dual diagnoses (NICE, Citation2016, updated 2020).

The recovery-oriented practice approach has been influenced by what individuals with lived experience of mental illness have mentioned as helpful during their recovery (Brekke et al., Citation2018; L. Byrne et al., Citation2013; Kenny et al., Citation2020; Rethink, Citation2010; Scott et al., Citation2018; Slade et al., Citation2014). Although definitions vary (Brekke et al., Citation2018), the approach is often connected to the concept of “personal recovery” (Anthony, Citation1993) focusing on the ability to live a subjectively hopeful, satisfying and contributing life alongside the limitations of the mental disorders. Further, mutual conceptualizations of recovery-oriented practice often emphasize the empowerment of service-users by focusing on their strengths, increased autonomy, and explain recovery as a non-linear journey (Holley et al., Citation2016; Scott et al., Citation2018; Tiderington, Citation2017).

Positive risk-taking has been mentioned as an imperative aspect of recovery-oriented practice by facilitating possibilities for progress and growth in life-areas perceived as important by the service-user (Bertram & Stickley, Citation2005; Gaffey et al., Citation2016; Giusti et al., Citation2019; Holley et al., Citation2016; Scott et al., Citation2018). Positive risk-taking has been described as involving situations that could both lead to positive or negative outcomes, but where the individuals’ strengths and potentials for positive outcomes should be emphasized (Felton et al., Citation2017; Scott et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, the possibility of adverse consequences is a natural part of life (Gaffey et al., Citation2016), and is important for providing opportunities for reflection and learning (Felton et al., Citation2017). Perceived challenging activities that could lead to a “slip” in progress, or relapse, should therefore not be avoided (Kenny et al., Citation2020).

Previous findings have however identified that mental health practitioners showed a reluctance to encourage positive risk-taking and held negative and risk aversive attitudes (Bertram & Stickley, Citation2005; Gaffey et al., Citation2016; Giusti et al., Citation2019). Further, current risk-assessment/management procedures that are routinely performed within UK mental health settings, have been criticized for overemphasizing the potential adverse consequences resulting from positive risk-taking, rather than focusing on the individual’s needs and rights (Bertram & Stickley, Citation2005; Holley et al., Citation2016). This supports the raised concerns and previous findings that the traditional, deeply rooted, “clinical recovery” approach may be lingering within the mental health system (Keet et al., Citation2019; Le Boutillier et al., Citation2015; Roberts & Bell, Citation2013). In contradiction to recovery-oriented practice, clinical recovery focuses on symptom-elimination, restoration, and relapse absence (Egeland et al., Citation2021; Luigi et al., Citation2020). And has been associated with institutional responses, coercive interventions, and an overemphasis of psychopharmacology (Slade et al., Citation2014).

For those with a dual diagnosis, recovery perceptions may differ related to the mental illnesses and the SUDs (Crowe et al., Citation2013). One disorder may overshadow the other (Black, Citation2021; Crome et al., Citation2009), and it is possible that aspects of the clinical recovery approach may particularly continue to be applied to individuals with SUDs, where abstinence or controlled substance use may be overemphasized as part of someone’s recovery journey, oversimplifying the recovery process (Department of Health & Social Care, Citation2021; Roberts & Bell, Citation2013). The recovery-oriented practice approach has previously been stated to have been met with suspicion and concern from policymakers and mental health practitioners, due to emphasizing a harm-reduction approach, rather than abstinence (Brekke et al., Citation2018; Crome et al., Citation2009; Roberts & Bell, Citation2013; Scott et al., Citation2018) – possibly reflected by legal issues relating to the use of illicit substances (Roberts & Bell, Citation2013).

Individuals with dual diagnoses are further part of a stigmatized group (Donald et al., Citation2019; NICE, Citation2016, updated 2020), which tends to increase pessimistic attitudes, disbelieves in recovery, and perceptions that treatment approaches need to be “harsher” (Gomez et al., Citation2020; Luigi et al., Citation2020). And all these aspects may negatively impact these individuals’ support and opportunities (Roberts & Bell, Citation2013). It has been suggested that mental health practitioners’ understandings, beliefs, and attitudes toward service-users’ recovery may particularly affect the implementation of recovery-oriented practice (Brekke et al., Citation2018; Keet et al., Citation2019; Wilrycx et al., Citation2015).

Due to an absence of specialist dual-diagnosis services in the UK, this group is primarily directed to community mental health services (CMHS) (NICE, Citation2016, updated 2020),: which plays a significant role in the provision of mental health care in the UK (the National Health Service NHS, Citation2019). The staff within CMHS largely consist of mental health support workers, who also comprise an increasing proportion of the workforce within the NHS (Wilberforce et al., Citation2017). This role includes closely working with the service-users by providing emotional support and support with practical tasks and social participation (Sandhu et al., Citation2017; Tiderington, Citation2017) to enhance their recovery progress (Bertram & Stickley, Citation2005; Keet et al., Citation2019; Tiderington, Citation2017), independence (Tiderington, Citation2017) and process of becoming active participants within their community, in a way that is most beneficial and meaningful to the individual (NHS, Citation2019) which aligns with the recommended recovery-oriented practice approach (Kenny et al., Citation2020; Leamy et al., Citation2016). It has been suggested that the mental health support worker role is understudied, offering fertile grounds to be explored (Wilberforce et al., Citation2017). Further, it is important to study the practice within these settings, as CMHS has been criticized of “re-institutionalizing” the service-users (Sandhu et al., Citation2017), and findings have shown that discharge rates and reductions in disability are low (Hamden et al., Citation2011; Sandhu et al., Citation2017) and that the service-users often live sheltered away from their community, are unemployed and have little social contact (Keet et al., Citation2019; Pattyn et al., Citation2013).

Research aims

To investigate mental health support workers recovery perceptions and approaches to positive risk-taking related to service-users with a dual diagnosis of mental illness and SUD.

Methods

Design

The current study was a cross-sectional design utilizing an online-survey that included a vignette, three positive risk-taking scenarios and related questions to generate qualitative data (survey-responses) from mental health support workers. The data was analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2013, Citation2019), providing a flexible guideline to the identification and interpretation of patterns within the data, that are interesting to the investigation of the participants recovery perceptions and positive risk-taking approaches related to service-users with a dual diagnosis of mental illness and SUD.

Participants

Twenty-nine UK based mental health support workers (see for participant information) completed the online-survey. The participants were recruited in May 2021 through convenience and snowball sampling methods. They were approached through a Welsh CMHS (where the lead researcher was employed), and through posts in a social media group for individuals aiming to become psychology trainees. It was believed that many support workers would be part of this group as the support worker role commonly is undertaken by psychology graduates to gain relevant experience before becoming a trainee.

Table 1. Participant information.

Materials

The materials that were developed for the current study included a vignette and three positive risk-taking scenarios (see supplementary materials) to help facilitate an analytic process and lead to responses that would be relevant to the research aims (Queiroz de Macedo et al., Citation2015), in an ethically sound and non-intimidating way (Holley & Gillard, Citation2018). Existing empirical literature, the DSM-V (APA, Citation2013) and discussions with the wider research team informed the procedure of developing the materials. As two of the researchers have expert knowledge on substance-misuse and addictions and one of the researchers have experience of supporting service-users with dual-diagnoses within a CMHS setting it was believed that plausible and realistic materials, effectively addressing the research questions, could be developed without the inclusion of external specialists on the topic.

The vignette

The vignette (Supplementary Material) described a service-user with a dual diagnosis within a CMHS. The development of this vignette was influenced by a case-study from Donald et al. (Citation2019) describing an individual with a dual diagnosis of borderline personality disorder and poly-drug SUD. The aim was to provide a hypothetical description of a service-user living within a CMHS. There was no mention of ethnicity or gender, as perceptions of recovery may differ depending on these factors (Holley & Gillard, Citation2018).

The positive risk-taking scenarios

The three positive risk-taking scenarios (Supplementary Material) described hypothetical scenarios that could have either positive or negative consequences. The first scenario focused on the regaining of financial responsibility; potentially leading to increased independence, or the money being spent on drugs. The second scenario focused on medication reduction/cessation; although it may lead to increased symptoms, an increased sense of control and life-quality may facilitate recovery (Felton et al., Citation2017; Rethink, Citation2010). Lastly, the third scenario focused on the attendance of a social gathering at a drinking establishment, which could lead to increased substance-use and thus a decrease in wellbeing or could reduce social isolation and thus improve wellbeing. The first scenario was retrieved from Holley and Gillard (Citation2018) and the other two scenarios were developed by the researchers, following the development-procedure described above. It was believed that three scenarios would generate enough data, while minimizing the risk of “respondent-fatigue” (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013).

Procedure

The online survey was distributed through “Onlinesurveys.ac.uk.” This data-collection method allowed for a rapid recruitment process, and importantly enabled anonymity and privacy to the participants (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013), as some may have been colleagues of the researcher. Furthermore, this method was safe during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. A link to the survey was shared with potential participants through the study-invitation. Before beginning the survey, the participants were asked to confirm that they had read the study-information, presented during the survey-introduction, and consent to their data to being used in the research. No incentives were offered. Ethical approval (20ET05LR) was obtained from the Faculty Ethics Committee of the University of South Wales.

The survey began by asking the participants to provide demographic information (displayed in ). Before proceeding to the main part of the survey, the participants were instructed to not write about any personal experiences with service-users to minimize the risk of disclosing someone’s identity, confidential information, or potential professional misconduct. They were also informed that there were no “right or wrong” answers.

The participants were asked to read the vignette and to respond to the three recovery-related questions: “When you think of recovery from a mental health disorder and substance use disorder, what may that mean?,” “When it comes to Sam specifically, what aspects do you think would help them to recover?” and “What may hinder Sam’s recovery, as you see it?.” These were influenced by questions asked by Brekke et al. (Citation2018) investigating practitioners dilemmas regarding the implementation of recovery-oriented practice to dual-diagnoses.

The participants were subsequently presented with the three positive risk-taking scenarios. After each scenario, they were asked: “If you were Sam’s support worker, what do you believe would be the right thing to do in this scenario?” and “What do you believe your responsibilities would be?.” The first question was influenced by a question asked during Holley et al. (Citation2016) study on positive risk-taking and recovery-oriented practice. The second question was developed by the researchers and believed to be important based on previous findings indicating that mental health practitioners tend to feel responsible to protect the service-users (Holley et al., Citation2016).

Data analysis

The data was analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006, Citation2013, Citation2019). Their six-phase process was adopted as a flexible guideline during the stages of data-engagement, coding, and theme development (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021). Before beginning the analysis, the data was prepared by collating the responses from the community and inpatient support workers into two separate datasets, to enable the identification of potential differences between the groups during the analysis as the latter group tends to support individuals with higher level needs, and these practitioners may therefore hold different recovery beliefs and positive risk-taking approaches (Stull et al., Citation2017).

The first step of the analysis began with data-familiarization, where the data was re-read over multiple sessions. Following this, the process of generating codes began. The coding process can be theory-driven (deductive) and data-driven (inductive), it has been argued that each approach cannot be used exclusively but that one approach tends to predominate (D. Byrne, Citation2022). In the context of the current study, the inductive approach predominated – but as emphasized by Braun and Clarke (Citation2021), thematic analysis cannot be carried out in a “theoretical vacuum” as researchers always make theoretically informed assumptions of what the data represents. This was evident when performing the analysis as literature on the research topics had been reviewed prior to developing the research aims. This influenced the analysis as there was a search for patterns in the data indicating whether aspects of the participants recovery perceptions and risk-taking approaches followed the recovery-oriented practice approach or the clinical recovery approach.

The process of coding in reflexive thematic analysis has been described as an open and organic process (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021, Citation2023). It involved going through the datasets multiple times while highlighting and labeling all data-extracts perceived as meaningful to the research questions. This was done manually (using “Pages”). Both semantic and latent codes were generated. As the coding process continued, less new codes were developed, and data-extracts could instead be labeled by an already existing code. Some data-extracts were labeled by more than one code if it could be described/interpreted in more than one way. The next step involved reviewing the codes, by collating all data-extracts belonging to each code into a list. This enabled the researcher to identify whether the codes accurately described the combined data-extracts. Sometimes, the code was adjusted to provide a better description of the combined data-extracts. Codes that included very few data-extracts were removed.

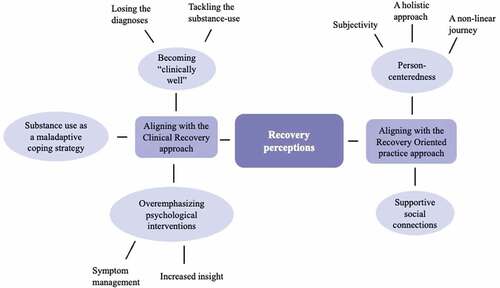

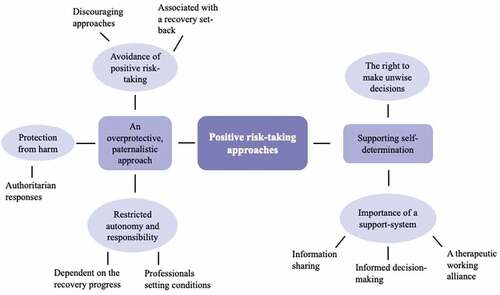

The codes were subsequently assembled to form initial themes (see for an overview of the theme development process). Codes that did not suit any of the themes or add any meaningful information to the research aims were saved under “miscellaneous” if proving useful later. If not, these codes were removed. During the theme-development stage, it was identified that the initial themes generated for the community- and inpatient support workers recovery perceptions and positive risk-taking approaches mainly shared similarities. Therefore, it was believed that there was no need to differentiate between the groups and the initial themes from the two groups were thus combined. The aim was to produce themes that cohered and fitted well within the overall analysis, while addressing the research aims (Braun & Clarke, Citation2023). To visualize this, thematic maps were created ().

Subsequently, the codes (and belonging data-extracts) connected to each theme were reviewed to ensure that the theme in question adequately captured the pattern of meaning in the data. As emphasized by Braun and Clarke (Citation2013); the importance of a theme was judged based on what it captured, and its meaningfulness relating to the research questions, rather than how it was quantified across the dataset. Thus, no rigid rules were set regarding the prevalence during the theme-development phase. Mainly semantic themes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2013) were generated. However, as the themes were identified through the light of the topic-related literature, the analysis became more interpretative during the write up of the findings, by discussing how the themes related to existing theories and previous research findings.

The initial analysis was conducted by the lead researcher with regular consultation with the wider research team to ensure rigor. Two of the researchers independently considered the appropriateness of the development of the codes, the themes and subthemes. Some modifications were made until agreement was reached on the applicability to the research questions.

Reflexive comment

The research-topics of the current study was influenced by the lead researchers critical reflections and past experiences of working as a mental health support worker within various CMHS. This experience also sparked the interest to focus on individuals with dual diagnoses after having witnessed the difficulties this group can have, including stigma and restricted opportunities. Lastly, the recovery-oriented practice approach aligns with the lead researcher values, who supports a humanistic and holistic approach within mental health practice.

Findings & discussion

The reflexive thematic analysis led to the identification of two overarching themes that related to the support workers recovery perceptions (“aligning with the clinical recovery approach” and “aligning with the recovery-oriented practice approach”) and two overarching themes that related to their positive risk-taking approaches (“An overprotective, paternalistic approach” and “supporting self-determination”). Each overarching theme consisted of several themes and sub-themes (see ) that have been described and discussed below, in light of previous research literature and accompanied by corresponding verbatim participant quotes.

Overarching theme - perceptions aligning with the clinical recovery approach

It was identified from the themes that some aspects mentioned as important to dual-diagnosis recovery followed the more traditional, clinical recovery approach primarily focused on reducing symptoms. In the current study, this perception was particularly evident related to the substance-use. It was also identified that the participants perceived that psychological interventions were important by, for example, helping the service-user to learn to manage the disorders. These aspects may however prevent the recovery progress, when perceived that symptom reduction or management needs to be achieved prior to focusing on other important recovery-elements (Keet et al., Citation2019).

Becoming “clinically well”

Distinctly aligning with the clinical recovery approach, participants sometimes perceived recovery as being reached when the service-user no longer had the diagnoses: “When it comes to mental health and substance misuse recovery may mean overcoming the issue and/or disorder to live a full life. E.g., Living a tee-total life, experience no mental ill health symptoms.” (P2). This approach has been mentioned as over-simplistic, over-ambitious and consequently preventing progress; due to the perceived need of being “clinically well” before focusing on other, potentially more important life-aspects facilitating the recovery progress, as mentioned above (Keet et al., Citation2019). However, this perception was particularly common related to the SUD, where the participants emphasized the importance of tackling the substance-use:

In regard to the substance use disorder I think of recovery as an individual attempts to try and reduce their usage of substances. (P21: Senior community SW, 3.5 years’ experience)

A person having help to not rely on substances and becoming clean from this. (P4: Inpatient SW, 21 months experience)

One commonly mentioned reason for the perceived importance of reduced substance use, was the belief that it could work as a recovery barrier by negatively affecting the service-users mental health:

The fact that he still needs to use substances weekly as they don’t help him with his mental health and dependence. (P3: Community SW, 3 months experience)

I think over time addressing the substance misuse is vital because it can significantly impair an individual’s cognitive ability and ultimately make it harder for Sam to manage his emotions. (P17: Inpatient SW, 14 months experience)

The perceived importance of reduced substance use aligns with previous findings investigating mental health practitioners’ recovery beliefs regarding SUD’s (e.g., Brekke et al., Citation2018; Scott et al., Citation2018) and supports the argument that the ability to live meaningfully alongside ongoing symptoms may be less emphasized for SUD’s compared to mental illnesses (Brekke et al., Citation2018; Roberts & Bell, Citation2013). The perception of substance-use reduction/abstinence as imperative may however be different to the service-user’s needs, wants and goals (Brekke et al., Citation2018) and improvements in wellbeing should be pivotal to the focus on reduced substance-use (Department of Health, Citation2011).

Substance misuse as a maladaptive coping strategy

Substance use was perceived to reinforce a negative loop, providing short-term relief, at the cost of long-term intensification of mental health struggles. As mentioned above, the participants perceived sustained substance use as a recovery barrier, due to negatively impacting the service-users mental health, but it was also identified that participants perceived that substance use could be a recovery barrier through working as a maladaptive coping mechanism, helping during times of mood-instability and emotional dysregulation. Hence, the need to identify and utilize alternative, “healthier” coping mechanisms was emphasized: “To me, recovery would reflect less dependence on substances to manage mental health, and more reliance on helpful, learned and self-taught coping skills.” (P26).

The development of healthy coping strategies has indeed been mentioned as an important recovery aspect (Gratz et al., Citation2008; Trull et al., Citation2018), that has been supported by findings from research including service-users with borderline personality disorder (Kverme et al., Citation2019; Ng et al., Citation2019). However, as the purpose behind the identification of new coping mechanisms seemed to derive from the perception that this would help prevent the substance-use, it may nonetheless indicate that the participants beliefs align with the clinical recovery approach:

Recovery means they are able to live without strict support as they are able to correctly control themselves and deal adequately with their emotions so not to engage in self-harm or substance misuse. (P1: Inpatient SW, 14 months experience)

Substance misuse recovery is the gradual process of withdrawing from that substance and then afterwards identifying healthier coping mechanisms in order to prevent the consumption of that substance again. (P17: Inpatient SW, 14 months experience)

Overemphasizing psychological interventions

Although psychological interventions (including psychopharmacology) can be important to a person’s recovery, these aspects have been linked to the clinical recovery approach and mentioned as potentially hindering recovery when receiving the dominant focus and being perceived as facilitating recovery in isolation from other important recovery elements (Egeland et al., Citation2021; Holley et al., Citation2016; Rethink, Citation2010). In the current study, the participants often mentioned psychological interventions as facilitating recovery through the process of helping the service-user developing skills and techniques, helping with mood-instability and emotional dysregulation:

Sam may also benefit from some therapeutic support to help with low mood, such as some CBT from an IAPT service. (P26: Community SW, 7 months experience)

Psychological interventions around BPD to help with emotional regulation (CBT, DBT, MBT): (P1: Inpatient SW, 14 months experience)

An increased ability to manage the disorders was, for example, mentioned as important to enable service-users to live a subjectively meaningful life, focused on increasing life-quality alongside the disorders (Bird et al., Citation2014; Kverme et al., Citation2019):“ … recovery may mean the ability to manage their condition so that they can reach their full potential and live a relatively healthy life and possess a quality of life that is meaningful for that person.” (P23). As mentioned previously, this may prevent the recovery progress, by focusing on an increased ability to manage symptoms before focusing on other important aspects that can facilitate the recovery progress.

The participants also mentioned that the intervention’s psychoeducational facets could increase insight, which was perceived as important to, for example, understand the disorder’s interaction and into behavioral triggers, particularly the substance-use: “They start to understand their situation and addiction and they start to work out to stay away from their bad habits.” (P30). Insight may normalize experiences and increase acceptance, leading to a willingness to search for meaning and strengths from one’s experiences (Bird et al., Citation2014), but when emotions, thoughts and behaviors are connected to the disorders, it may lead to a sense of one’s own intentions being understated (Kverme et al., Citation2019), and of being no more than a diagnosis (Bird et al., Citation2014).

Overarching theme - beliefs aligning with recovery-oriented practice

It was however also identified from some themes that some of the aspects perceived as important to dual-diagnosis recovery aligned with the recommended recovery-oriented practice approach. Participants emphasized the importance of putting the individual in focus, and that each person’s recovery journey will be different by mentioning the imperative aspects of recovery being subjective, holistic, and non-linear. Perceptions aligning with recovery-oriented practice was also evident through participants emphasizing that meaningful and supportive social connections can be crucial to recovery-progress.

Person-centeredness

Some aspects that participants mentioned as important to recovery, followed a person-centered approach. Firstly, recovery was described as subjective: “Recovery means being able to improve their mental health and wellbeing. This is quite personal for each individual, so thinking about what they consider to be their good mental health, and what they want/need to get out of their lives.” (P16), which has been mentioned as empowering service-users to shape their lives and take ownership over their recovery (Department of Health, Citation2011; Kverme et al., Citation2019; Roberts & Bell, Citation2013). Further, this may discourage authoritative approaches, where mental health practitioners incorrectly believe to be knowing what is best for the service-users, overshadowing their own beliefs (Brekke et al., Citation2018).

The participants also mentioned the important aspect of recovery being seen as a holistic and non-linear journey (Katsakou et al., Citation2019; Scott et al., Citation2018): “Recovery encompasses many areas, and it is an ongoing process. It is not something that is reached but an ongoing journey for an individual, as well as the people involved in their care and support network.” (P32). Allowing temporary setbacks has been mentioned as important when taking steps toward development and growth (Kverme et al., Citation2019). Service-users thus needs to have access to support that is flexible and suited to their specific needs (von Braun et al., Citation2013; Slade et al., Citation2014). This has especially been mentioned as important relating to those with a dual diagnosis; due to its complex, chronic, and relapsing nature (Baldacchino, Citation2007; Manuel et al., Citation2015). This was highlighted by some participants: “ … (access to) support needed with good wellbeing and decline in wellbeing.” (P33)

Supportive social connections

The participants mentioned the importance of avoiding the trigger of spending time in friendship groups encouraging substance use and they recognized that new social contacts could help ease the break from old friendships by reducing loneliness and prevent increased substance-use:

Social support of people who are in similar situations so not to be around current friend circle who are using substances. (P1: Inpatient SW, 14 months experience)

I believe Sam would benefit from being part of a community that does not provide any negative behavioral influence. This would promote feelings of connectedness and help combat feelings of loneliness. (P26: Community SW, 7 months experience)

Previous research on recovery facilitators has emphasized that the ability to build meaningful and supportive social connections is crucial (Bird et al., Citation2014; Kverme et al., Citation2019; Ng et al., Citation2019; Rethink, Citation2010; Wilrycx et al., Citation2015); particularly in peer support-groups consisting of individuals sharing similar struggles, experiences, thoughts, and feelings, as it may lead to a sense of “connectedness,” compared to the “otherness” that service-users may experience from the outside world (Bird et al., Citation2014; Kverme et al., Citation2019). Further, it may encourage beliefs of recovery as possible, through meeting individuals further in their journey (Keet et al., Citation2019).

Overarching theme – an overprotective, paternalistic approach

As previously mentioned, positive risk-taking is an imperative element of recovery-oriented practice, by facilitating possibilities for progress and growth in life-areas perceived as important by the service-users. Some of the identified themes however showed that the participants were reluctant to encourage positive risk-taking, to avoid potential recovery-setbacks. Further, it was identified that the participants felt a responsibility to keep the service-users away from harm by, for example, withholding increased autonomy and responsibility, until a safer time, such as when the service-user’s recovery progress was seen as adequate.

Avoidance of positive risk taking

Positive risk-taking may have positive or negative outcomes. The potential for positive outcomes should however be emphasized, to enhance the service-users’ chances for progress and growth (Deering et al., Citation2019; Felton et al., Citation2017). Nevertheless, positive risk-taking was sometimes associated with a recovery set-back, or relapse: “If Sam is early in recovery, this risks a relapse. Even well into recovery this is still a risk.” (P25). As recovery setbacks may provide opportunities for growth and change (through a “trial and error” process), this should not cause risk-avoiding attitudes (Gaffey et al., Citation2016; Kenny et al., Citation2020). The participants however displayed discouraging attitudes to positive risk-taking, when believed to impact the progress negatively: “As she is not sectioned you cannot stop her from doing it but you could try and discourage it if you think it may result in relapse” (P1).

Alas, when mental health practitioners weigh up potential benefits against potential harms, the safe option of reducing exposure to risk tends to be emphasized (Giusti et al., Citation2019; Scott et al., Citation2018): “Encourage Sam to keep being under appointeeship since it is working well for him” (P22). Furthermore, participants mentioned coercive practices, through sharing risk-aversive attitudes; focusing on what could go wrong, progress that could be lost and the potential need for increased restrictions:

If Sam has capacity, I cannot change their mind so I would just make sure they are aware of the dangers and what they might be risking. (P24: Community SW, 1 year experience)

Inform what would be the best route … see if they can stick to goals to support freedom of choice or need to have stricter management of substances and monitoring friends who engage in such. (P33: Inpatient SW, 3 years’ experience)

“Fear inducing” approaches have been identified in previous qualitative research, where mental health practitioners used fear to leverage service-user’s to, for example, comply with treatment, through using threats of hospitalization during non-adherence (Tiderington, Citation2017).

Protection from harm

Discouragement of positive risk-taking may derive from a perceived responsibility to protect the service-users from potential harm (Deering et al., Citation2019; Holley et al., Citation2016) and in the current study participants mentioned doing this by working in what was perceived to be the service-user’s “best interest:” … to have (their) best interests at heart and keep (them) safe and free from risk/vulnerability.’ (P8). This may however decrease the service-user’s autonomy and responsibility:

I would facilitate conversation around what (they) wanted to be different by taking over her own finance management and determine whether these changes could be put into place by continuing with the appointeeship. (P26: Community SW, 7 months experience)

It has been suggested that this approach may be encouraged through risk-assessments as these tends to overemphasize the protection of service-users (Gaffey et al., Citation2016). This potentially induce risk-aversive attitudes and stigmatized beliefs of service-users as incompetent, helpless (Stull et al., Citation2017), irresponsible (Balhara et al., Citation2016), and the often-faulty assumption of knowing what is in their “best interest” (Bertram & Stickley, Citation2005; Brekke et al., Citation2018; L. Byrne et al., Citation2013). Consequently, this may overthrow the persons autonomy, needs and goals (Crowe et al., Citation2013; Jackson-Blott et al., Citation2019; Wilrycx et al., Citation2015). Indeed, the traditional approach to positive risk-taking has tended to involve authoritarian responses and the belief that professionals need to make decisions for the service-users (Balhara et al., Citation2016; Brekke et al., Citation2018), which was held by some:

Be a part of MDT to make decisions about her progress and change in care plans. (P1: Inpatient SW, 14 months experience)

Ensuring Sam had access to speak with professionals who would make this decision. (P12: Community SW, 3.5 years’)

Blocking the psychological need of feeling empowered and competent by making choices and fulfilling goals, may cause feelings of being controlled and thus amotivation (Corrigan et al., Citation2014). As service-users often feel disempowered, and like they have lost control over their lives, identification of opportunities to regain control and of taking initiative is imperative (Rethink, Citation2010). However, the protective culture within these services may cause service-users to feel apprehensive toward increasing own responsibility and independence (Holley et al., Citation2016). A good balance has thus been mentioned as crucial, focusing on motivation and personal courage alongside appropriate support (Brekke et al., Citation2018; Rethink, Citation2010).

Restricted autonomy and responsibility

Previous findings have identified that mental health practitioners struggled to balance the amount of help offered with the responsibility given, by overemphasizing the former (Bertram & Stickley, Citation2005; Brekke et al., Citation2018) and feeling responsible to assess the service-users mental health prior to the positive risk-taking; risking that symptom alleviation takes priority over progress (Holley et al., Citation2016). Similarly, in the current study participants mentioned that the suitability of increased responsibility depended on their current mental health and recovery progress:

If Sam is on a positive path, yes, he should be allowed that responsibility back, that is his choice. (P25: Senior Community SW, 2 years’ experience)

Could be difficult as she is still using substances, but it is good to encourage independence … if her progress is sufficient … (P1: Inpatient SW, 14 months experience)

One way of increasing service-users autonomy and responsibility is to include them in the decision-making process regarding the positive risk-taking (Deering et al., Citation2019). Indeed, the participants mentioned this as important: “I think it is important that Sam is able to be involved in decision-making … ” (P10), although often by emphasizing a gradual approach, involving making compromises and setting conditions:

Maybe there could be a compromise where Sam is in charge of some of their money, but some is kept behind specifically for bills. (P15: Community SW, 18 months experience)

Come to an agreement and conditions and the spending limit per day should be set gradually. (P30: Inpatient SW, 4 years’ experience)

Further, participants mentioned that the service-users mental health should be monitored to ensure that it did not worsen as a consequence, but also to see whether they stuck to the compromises and hence could be given further control: “Maybe allowing Sam to have small increments of their money … so that they can practice budgeting their money … before increasing the increments slowly over time if Sam uses their money wisely.” (P24). The notion of shared decision-making as involving compromising and professionals setting conditions, rather than it being an active, collaborative process where experiences, knowledge and expertise can be shared (Rethink, Citation2010) was also identified in Holley et al. (Citation2016) study. And although this approach could withhold autonomy, and slow the recovery, a systematic review by Deering et al. (Citation2019) investigating what service-user’s perceived as beneficial regarding risk-management, identified that some preferred the withholding of responsibility, until having decided on the preferred pace of regaining control. This aligns with the notion mentioned above, of it being important to find a good balance between dependency and independence, suited to the service-users’ own preferences (Brekke et al., Citation2018; Rethink, Citation2010).

Overarching theme - supporting self-determination

Some themes however identified that the participants emphasized that service-users have the right to make their own decisions, and instead of trying to discourage positive risk-taking it was believed as important to provide a support-system of various professionals that could help service-users to make an informed decision, which has been mentioned as a crucial element of positive risk-taking. It was also perceived as important to provide a safe and therapeutic space where concerns could be discussed in an honest way, which also has been mentioned as useful to enable the identification of the right type of support for the service-user.

The right to make unwise decisions

As previously mentioned, it is imperative that everyone is given the right to make their own life-decisions and to make mistakes (Felton et al., Citation2017). In a previous study, it was identified that mental health practitioners acknowledged that they had to accept the service-users’ choices regardless of the potential consequent harm (Tiderington, Citation2017). This was also acknowledged by participants in the current study:

Regardless of Sam’s vulnerabilities unless he is not deemed to have mental capacity, he has the right to make unwise decisions. (P14: Community SW, 10 years’ experience)

Importance of a support-system

The participants perceived that they had a responsibility to report about the service-users positive risk-taking to their mental health team. This may benefit the practitioners, as the perceived responsibility over the service-users wellbeing is shared between several professionals, decreasing the fear of being held accountable during adverse consequences (Holley et al., Citation2016). However, in the current study, information-sharing was particularly perceived as important to provide the service-users with a wider support-system:

I would make my management aware that this is something they may want to do … so we would be able to support that decision and support them to the best that we can. (P19: Senior Community SW, 1.5 years’ experience)

Discuss with Sam that this may need to be shared with the wider team, just so information is handed over, rather than a controlling of risk. (P32: Inpatient SW, 3 years’ experience)

Further, this was perceived as enabling the service-users to receive support in making an informed decision, which has been mentioned as imperative to positive risk-taking, involving exploration of all potential (positive and negative) consequences (Holley et al., Citation2016; Rethink, Citation2010) prior to the service-users decision:

Without telling Sam what you believe he should do, encourage Sam to weigh up those pros and cons. (P25: Senior Community SW, 2 years’ experience)

Provide Sam with information about the risks/options so they can make an informed decision. (P10: Inpatient SW, 5 years’ experience)

To enhance the communication and collaboration between the service-users and the mental health practitioner’s regarding risk-management, the aspect of a therapeutic working alliance has been mentioned as important (Brown & Calnan, Citation2013; Deering et al., Citation2019). The participants in the current study did indeed mention feeling responsible to develop therapeutic rapport with the service-users regarding the positive risk-taking:

Provide a place for Sam to talk through their worries and thoughts (P31: Community SW, 6 months experience)

“Providing a therapeutic space for Sam to talk, discuss things in a safe environment… discuss any worries/concerns about it I would listen and try help find ways to manage situations that might come up”. (P10: Inpatient SW, 5 years’ experience)

This may enable the exploration of the service-users’ past difficulties, and more importantly – current potentials (Deering et al., Citation2019), while further increasing their confidence in raising sensitive matters and discussing their needs and wants; enabling the mental health practitioner to provide the right support (Brown & Calnan, Citation2013). Further, research findings have shown that service-users valued strong, honest, trusting and collaborative working relationships as part of their recovery (Bird et al., Citation2014; Kverme et al., Citation2019; Ng et al., Citation2019; Rethink, Citation2010).

Concluding discussion and implications

The current study aimed to investigate mental health support workers’ recovery perceptions and positive risk-taking approaches related to service-users with a dual diagnosis of mental illness and SUD to help identify whether the recommended recovery-oriented approach (Department of Health & Social Care, Citation2021; Keet et al., Citation2019; Kenny et al., Citation2020; Leamy et al., Citation2016) has been implemented within practice related to this group of service-users. The findings indicated that although some of the themes followed aspects of recovery-oriented practice- many of the themes aligned with the clinical recovery approach. This supports previous research findings and the notion that this traditional approach continues to prevail the mental health system (e.g., Gaffey et al., Citation2016, Giusti et al., Citation2019; Le Boutillier et al., Citation2015). The findings also support a recent comment by Egeland et al. (Citation2021), stating that more effort is needed to implement recovery-oriented practice within mental health services.

The key-findings from the current study were firstly the prevalent belief that it was imperative that the substance-use was targeted as part of the service-users recovery. This aligns with previous findings (e.g., Brekke et al., Citation2018; Scott et al., Citation2018) and supports the notion that aspects from clinical recovery approach may particularly be applied to the individual’s SUD, such as the belief that recovery only can be reached after the service-user reduces/stops their substance-use (Crowe et al., Citation2013; Roberts & Bell, Citation2013). As previously mentioned, the overemphasis of substance-use reduction/abstinence may detract from other important (e.g., psychosocial) aspects (Thylstrup et al., Citation2009), that may matter more to the service-user and which they should be encouraged to achieve despite continued substance use (Brekke et al., Citation2018; Department of Health & Social Care, Citation2021), to avoid oversimplifying the recovery process and negatively impacting these individuals’ opportunities (Roberts & Bell, Citation2013).

Secondly, it was identified that the participants tended to hold risk-aversive, overprotective approaches to positive risk-taking, supporting previous research findings also investigating mental health practitioners approaches to positive risk-taking (Bertram & Stickley, Citation2005; Gaffey et al., Citation2016; Giusti et al., Citation2019; Holley et al., Citation2016). Risk-aversive, overprotective approaches have been identified as counterproductive (Department of Health, Citation2009; NHS, Citation2019) and incompatible with recovery-oriented practice, through decreasing autonomy and increasing disempowerment (Brekke et al., Citation2018; Crowe et al., Citation2013; Jackson-Blott et al., Citation2019; Rethink, Citation2010; Wilrycx et al., Citation2015), which consequently may hold the service-users back in their recovery journey. It is unclear if the participants’ views would have differed if the vignette had focused on different mental health conditions. It may be that their attitudes to positive risk-taking reflects the stigma related to dual diagnoses, as mental health practitioners previously have underestimated these individuals by describing them as having lower cognitive abilities and as being disadvantaged (Gomez et al., Citation2020; Luigi et al., Citation2020) which can lead to discouragement and prevent the service-users from realizing their full potentials leading to under-achievement, worse life-chance and poorer wellbeing

Thirdly, there was an identified lack of emphasis on the imperative aspects of providing empowerment and hope regarding recovery, while focusing on the service-user’s strengths and abilities (Bird et al., Citation2014; Department of Health & Social Care, Citation2021; Kverme et al., Citation2019; Ng et al., Citation2019). Providing encouragement and hope that recovery is possible, while emphasizing the person’s abilities and strengths are central aspects of both recovery-oriented practice and positive risk-taking (Bird et al., Citation2014; Department of Health, Citation2009; Ng et al., Citation2019; Skogens et al., Citation2018) as this may lead to increased feelings of agency and courage which has been associated to recovery progress (Bertram & Stickley, Citation2005; Kverme et al., Citation2019). Further, Roberts and Bell (Citation2013) emphasized that these aspects encourage service-users to reach for their true potential.

Recommendations

The findings of the current study points toward a need to increase mental health support workers understanding of recovery-oriented practice and positive risk-taking related to service-users with a dual diagnosis of mental illness and SUD, to increase recovery-oriented practice within the settings that these professionals work in. Further, these findings support a recent argument from a UK government review focusing on recovery from addictions, stating that the workforce needs to be trained to improve their response to individuals with dual diagnoses (Black, Citation2021). This is important, to avoid negative implications for these service-users recovery, and the consequent negative effects that this may have on our society (Department of Health, Citation2009; Keet et al., Citation2019).

Promisingly, an NHS funded intervention (REFOCUS) is currently being evaluated within mental health services in England (Slade et al., Citation2017), aiming to provide training and support to mental health practitioners to implement recovery-oriented practice. Beneficially, REFOCUS is trans-diagnostic and trans-professional and can thus be applied to service-users with dual diagnoses, and within various settings, including CMHS and inpatient settings (Slade et al., Citation2015). However, REFOCUS is a lengthy, hence costly, intervention of 12 months duration (Slade et al., Citation2017) and the mental health-system has a longstanding history of financial challenges (Roberts & Bell, Citation2013). Nonetheless, the implementation of recovery-oriented practice is likely to improve cost-savings long-term through decreasing the service-users’ needs for services (Slade et al., Citation2017). If services begin routine monitoring of how their practices align with recovery-oriented practice, including positive risk-taking, it could encourage reflection and identification of specific practices in need of improvement (Leamy et al., Citation2016), enabling the intervention to be tailored to target these aspects.

It is important to mention that as most recovery research originates from Western countries where individualism is favored over collectivism, it is uncertain how the recovery-oriented practice suits individuals from Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic backgrounds. Future research should thus target this knowledge gap (Slade et al., Citation2017), to enable the development and implementation of culturally sensitive recovery approaches.

Study limitations

In the context of the current study it was useful to use an online-survey as data-collection method by providing the participants with anonymity and privacy, as potential participants were colleagues of the researcher. Noteworthy, there are also weaknesses to this method, that applied to the present study. Surveys tend to generate limited amount of data (e.g., one-line replies), further complicated by the inability to ask follow-up questions (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013). This issue was however balanced out by including a larger sample-size.

The current study included both community and inpatient based mental health support workers, and these groups may differ as the latter group often support individuals experiencing a mental health crisis (Wood et al., Citation2019) with higher level needs and these practitioners may therefore hold different recovery beliefs and approaches (Stull et al., Citation2017). However, including a vignette allowed everyone to focus on the same fictional service-user, instead of thinking of experiences related to the service-users that they encounter. Further, the potential differences were accounted for by separating the data from the two groups during the initial part of the analysis, until it was identified that the themes from the groups were similar. It is also important to mention that many of the participants were collected from a single CMHS in Wales and from a social media group for psychology graduates aiming to progress within the field. Hence, the sample may not be representative, and the current study would have benefitted from the inclusion of a wider sample.

Lastly, although it has recently been stated that the common practices of triangulation and member checking are unsuitable when using reflexive thematic analysis, as researcher subjectivity is perceived as a valued resource – the practice of member reflections has been recommended (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022), where the participants are asked to reflect on the analysis to provide further insights, enabling the identification of, for example, knowledge gaps and differences in understanding. The inclusion of member reflections was not possible in the current study, due to the anonymity of the participants. However, it could be argued that the inclusion of member reflections was less important in the context of the current study, as the lead researcher had several years of experience of working in the same role as the participants (mental health support worker) and therefore had an in-depth understanding of this role and insight into the work-environments.

Conclusion

As the transformation of the mental health system continues to move toward recovery-oriented practice; rigid systems, cultures and attitudes are required to shift away from the traditional clinical recovery approach (Gaffey et al., Citation2016). Thus, there is a continuous need for research to investigate facilitators or barriers to its implementation which may exist at macro-systemic, organizational, and individual levels (Tiderington, Citation2017). The current study contributed to recovery research by focusing on a prevalent but understudied professional-group’s recovery beliefs relating to a particularly vulnerable group of service-user’s, namely those with a dual-diagnosis of mental illness and SUD.

The findings supported previous findings focusing on mental health practitioners’ beliefs regarding recovery and risk-taking; that more effort is needed to move mental health services away from the clinical recovery and toward recovery-oriented practice, which arguably is a more humanistic approach. The current study particularly identified three aspects in need of change: the overemphasis on reduced substance use to dual-diagnosis recovery, the aversive and overprotective approaches to positive risk-taking and the lack of emphasis on providing hope, empowerment and highlighting the service-users strengths and abilities. It is imperative to target these aspects to avoid negative implications for these service-user’s life-quality and to enhance their recovery progress- which consequently should have beneficial effects on society long-term. Fortunately, interventions to increase recovery-oriented practice are currently being evaluated in England. However, due to the length- and hence the cost of these, it may be beneficial for services to start routine evaluation of their practices, to enable the intervention to target service-specific areas in need of improvement.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.5 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants who contributed with their time and effort to partake in the present study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request, without undue reservation.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2023.2234307

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychological Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Anthony, W. A. (1993). Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 16(4), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095655

- Baldacchino, A. (2007). Co-morbid substance misuse and mental health problems: Policy and practice in Scotland. The American Journal on Addictions, 16(3), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/08982100701375209

- Balhara, Y. P., Parmar, A., Sarkar, S., & Verma, R. (2016). Stigma in dual diagnosis: A narrative review. Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry, 32(2), 128–133. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-9962.181093

- Bertram, G., & Stickley, T. (2005). Mental health nurses, promoters of inclusion or perpetuators of exclusion? Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 12(4), 387–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2005.00849.x

- Bird, V., Leamy, M., New, J., Le Boutillier, C., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2014). Fit for purpose? validation of a conceptual framework for personal recovery with current mental health consumers. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 48(7), 644–653. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867413520046

- Black, C. (2021) Review of drugs part two: Prevention, treatment, and recovery. UK Department of Health and Social Care. Retrieved from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-drugs-phase-two-report/review-of-drugs-part-two-prevention-treatment-and-recovery

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research. Sage Publications.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? what counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. International Journal of Transgender Health, 24(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2023). Is thematic analysis used well in health psychology? A critical review of published research, with recommendations for quality practice and reporting. Health Psychology Review, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2022.2161594

- Brekke, E., Lien, L., Nysveen, K., & Biong, S. (2018). Dilemmas in recovery-oriented practice to support people with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: A qualitative study of staff experiences in Norway. International Journal Mental Health System, 12(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-018-0211-5

- Brown, P., & Calnan, M. (2013). Trust as a means of bridging the management of risk and the meeting of need: A case study in mental health service provision. Social Policy and Administration, 47(3), 242–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2012.00865.x

- Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality & Quantity, 56(3), 1391–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

- Byrne, L., Happell, B., Welch, T., & Moxham, L. J. (2013). ‘Things you can’t learn from books’: Teaching recovery from a lived experience perspective. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 22(3), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00875.x

- Corrigan, P. W., Druss, B. G., & Perlick, P. A. (2014). The Impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 15(2), 37–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100614531398

- Crome, I., Chambers, P., Frisher, M., Bloor, R., & Roberts, D. (2009). The relationship between dual diagnosis: Substance misuse and dealing with mental health issues. Social Care Institute for Excellence, 30, 1–23. https://www.scie.org.uk/publications/briefings/files/briefing30.pdf

- Crowe, T. P., Kelly, P., Pepper, J., McLennan, R., Deane, F. P., & Buckingham, M. (2013). Service based internship training to prepare workers to support the recovery of people with co-occurring substance abuse and mental health disorders. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 11(2), 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-012-9419-9

- Deering, K., Pawson, C., Summers, N., & Williams, J. (2019). Patient perspectives of helpful risk management practices within mental health services. A mixed studies systematic review of primary research. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 26(5–6), 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12521

- Department of Health. (2009). Best practice in managing risk: Principles and guidance for best practice in the assessment and management of risk to self and others in mental health services. Crown Copyright.

- Department of Health. (2011). No health without mental health: A cross-government mental health outcomes strategy for people of all ages. Crown Copyright.

- Department of Health & Social Care. (2021). UK government recovery champion annual report. Crown Copyright.

- Donald, F., Arunogiri, S., & Lubman, D. I. (2019). Substance use and borderline personality disorder: Fostering hope in the face of complexity. Australasian Psychiatry, 27(6), 569–572. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856219875061

- Egeland, K. M., Benth, J. S., & Heiervang, K. S. (2021). Recovery-oriented care: Mental health workers’ attitudes towards recovery from mental illness. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 35(3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12958

- Evans-Lacko, S., & Thornicroft, G. (2010). Stigma among people with dual diagnosis and implications for health services. Advances in Dual Diagnosis, 3(1), 4–7. https://doi.org/10.5042/add.2010.0187

- Felton, A., Wright, N., & Stacey, G. (2017). Therapeutic risk-taking: A justifiable choice. BJ Psychology Advances, 23(2), 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.115.015701

- Gaffey, K., Evans, D. S., & Walsh, F. (2016). Knowledge and attitudes of Irish mental health professionals to the concept of recovery from mental illness - five years later. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 23(6–7), 387–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12325

- Giusti, L., Ussorio, D., Salza, M., Malavolta, M., Aggio, A., Bianchini, V., Casacchia, M., & Roncone, R. (2019). Italian investigation on mental health workers’ attitudes regarding personal recovery from mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(4), 680–685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-018-0338-5

- Gomez, K. U., Carson, J., Brown, G., & Holland, M. (2020). Positive psychology in dual diagnosis recovery: A mixed methods study with drug and alcohol workers. Journal of Substance Use, 25(6), 663–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2020.1760376

- Gratz, K. L., Tull, M. T., Baruch, D. E., Bornovalova, M. A., & Lejuez, C. W. (2008). Factors associated with co-occurring borderline personality disorder among inner-city substance users: The roles of childhood maltreatment, negative affect intensity/reactivity, and emotion dysregulation. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49(6), 603–615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.04.005

- Hamden, A., Newton, R., McCauley-Elmson, K., & Cross, W. (2011). Is deinstitutionalization working in our community? International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 20(4), 274–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2010.00726.x

- Holley, J., Chambers, M., & Gillard, S. (2016). The impact of risk management practice upon the implementation of recovery-oriented care in community mental health services: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Mental Health, 25(4), 315–322. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1124402

- Holley, J., & Gillard, S. (2018). Developing and using vignettes to explore the relationship between risk management practice and recovery- oriented care in mental health services. Qualitative Health Research, 28(3), 371–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317725284

- Jackson-Blott, K., Hare, D., Davies, B., & Morgan, S. (2019). Recovery-oriented training programmes for mental health professionals: A narrative literature review. Mental Health and Prevention, 13, 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2019.01.005

- Katsakou, C., Pistrang, N., Barnicot, K., White, H., & Priebe, S. (2019). Processes of recovery through routine or specialist treatment for borderline personality disorder (BPD): A qualitative study. Journal of Mental Health, 28(6), 604–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1340631

- Keet, R., de Vetten-McMahon, M., Shields-Zeeman, L., Ruud, T., van Weeghel, J., Bahler, M., Mulder, C. L., van Zelst, C., Murphy, B., Westen, K., Nas, C., Petrea, I., & Pieters, G. (2019). Recovery for all in the community; position paper on principles and key elements of community-based mental health care. BMC Psychiatry, 19(174), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2162-z

- Kenny, T. E., Boyle, S. L., & Lewis, S. P. (2020). #recovery: Understanding recovery from the lens of recovery- focused blogs posted by individuals with lived experience. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(8), 1234–1243. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23221

- Kverme, B., Native, E., Veseth, M., & Moltu, C. (2019). Moving toward connectedness – a qualitative study of recovery processes for people with borderline personality disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(430), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00430

- Leamy, M., Clarke, E., Le Boutillier, C., Bird, V., Choudhury, R., MacPherson, R., Pesola, F., Sabas, K., Williams, J., Williams, P., & Slade, M. (2016). Recovery practice in community mental health teams: National survey. British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(4), 340–346. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160739

- Le Boutillier, C., Chevalier, A., Lawrence, V., Leamy, M., Bird, V. J., Macpherson, R., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2015). Staff understanding of recovery-orientated mental health practice: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Implementation Science, 10(1), 87–87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0275-4

- Lee, H. J., Bagge, C. L., Schumacher, J. A., & Coffet, S. F. (2010). Does comorbid substance use disorder exacerbate borderline personality features? a comparison of borderline personality disorder individuals with vs. without current substance dependence. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, & Treatment, 1(4), 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017647

- Luigi, M., Rapisarda, F., Corbière, M., De Benedicts, L., Bouchard, A. M., Felx, A., Miglioretti, M., Abdel-Baki, A., & Lesage, A. (2020). Determinants of mental health professionals’ attitudes towards recovery: A review. Canadian Medical Education Journal, 11(5). https://doi.org/10.36834/cmej.61273

- Manuel, J. L., Gandy, M. E., & Rieker, D. (2015). Trends in hospital discharges and dispositions for episodes of co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Admin Policy Mental Health, 42(2), 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-014-0540-x

- National Institute of Clinical Excellence. (2016; updated 2020). Coexisting severe mental illness and substance misuse: Community health and social care services. Retrieved from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng58

- Ng, F. Y. Y., Townsend, M. L., Miller, C. E., Jewell, M., & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2019). The lived experience of recovery in borderline personality disorder: A qualitative study. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 6(10), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-019-0107-2

- NHS England and NHS Improvement and the National Collaborating Central for Mental Health. (2019). The community mental health framework for adults and older adults. Retrieved from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/the-community-mental-health-framework-for-adults-and-older-adults/

- Pattyn, E., Verhaeghe, M., & Bracke, P. (2013). Attitudes toward community mental health care: The contact paradox revisited. Community Mental Health Journal, 49(3), 292–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-012-9564-4

- Queiroz de Macedo, J., Khanlou, N., & Villar-Luis, M. A. (2015). Use of vignettes in qualitative research on drug use: Scoping review and case example from Brazil. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 13(5), 549–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-015-9543-4

- Rethink. (2010). Recovery insights: Learning from lived experience. Retrieved from: https://www.slamrecoverycollege.co.uk/uploads/2/6/5/2/26525995/recovery_insights.pdf

- Roberts, M., & Bell, A. (2013). Recovery in mental health and substance misuse services: A commentary on recent policy development in the United Kingdom. Advances in Dual-Diagnosis, 6(2), 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1108/ADD-03-2013-0007

- Sandhu, S., Priebe, S., Leavey, G., Harrison, I., Krotofil, J., McPherson, P., Dowling, S., Arbuthnott, M., Curtis, S., King, M., Shepherd, G., & Killaspy, H. (2017). Intentions and experiences of effective practice in mental health specific supported accommodation services: A qualitative interview study. BMC Health Services Research, 17(471), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2411-0

- Scott, A. L., Pope, K., Quick, D., Aitken, B., & Parkinson, A. (2018). What does “recovery” from mental illness and addiction mean? perspectives from child protection social workers and from parents living with mental distress. Children and Youth Services Review, 87, 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.02.023

- Skogens, L., von Greiff, N., & Topor, A. (2018). Initiating and maintaining a recovery process – experiences of persons with dual diagnosis. Advances in Dual Diagnosis, 11(3), 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1108/ADD-09-2017-0016

- Slade, M., Amering, M., Farkas, M., Hamilton, B., O’Hagan, M., Panther, G., Perkins, R., Shepherd, G., Tse, S., & Whitley, R. (2014). Uses and abuses of recovery: Implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry, 13(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20084

- Slade, M., Bird, V., Chandler, R., Clarke, E., Craig, T., Larsen, J., Lawrence, V., Le Boutillier, C., Macpherson, R., McCrone, P., Pesola, F., Riley, G., Shepherd, G., Tew, J., Thornicroft, G., Wallace, G., Williams, J., & Leamy, M. (2017). REFOCUS: Developing a recovery focus in mental health services in England. Institute of Mental Health.

- Slade, M., Bird, V., Le Boutillier, C., Farkas, M., Grey, B., Larsen, J., Leamy, M., Oades, L., & Williams, J. (2015). Development of the REFOCUS intervention to increase mental health team support for personal recovery. British Journal of Psychiatry, 207(6), 544–550. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.155978

- Stull, L. G., McConnell, H., McGrew, J., & Salyers, M. P. (2017). Explicit and implicit stigma of mental illness as predictors of recovery attitudes of assertive community treatment practitioners. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 54(1), 31–38.

- Thylstrup, B., Johansen, K. S., & Sønderby, L. (2009). Treatment effect and recovery - dilemmas in dual diagnosis treatment. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 26(6), 552–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/145507250902600601

- Tiderington, E. (2017). “We always think you’re here permanently”: The paradox of “permanent” housing and other barriers to recovery-oriented practice in supportive housing services. Administration Policy Mental Health, 44(1), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0707-0

- Trull, T. J., Freeman, L. K., Vebares, T. J., Choate, A. M., Helle, A. C., & Wycoff, A. M. (2018). Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders: An updated review. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 5(15), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-018-0093-9

- von Braun, T., Larsson, S., & Sjöblom, Y. (2013). Chapter 11. narratives of clients’ experiences of drug use and treatment of substance use-related dependency. Substance Use & Misuse, 48(13), 1404. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2013.817148

- Wilberforce, M., Abendstern, M., Tucker, S., Ahmed, S., Jasper, R., & Challis, D. (2017). Support workers in community mental health teams for older people: Roles, boundaries, supervision and training. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(7), 1657–1666. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13264

- Wilrycx, G., Croon, M., Van den Broek, A., & van Nieuwenhuizen, C. (2015). Evaluation of a recovery-oriented care training program for mental healthcare professionals: Effects on mental health consumer outcomes. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 61(2), 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764014537638

- Wood, L., Jones, A., Bishop, E., & Williams, C. (2019). Evaluating the introduction of assistant psychologists to an acute mental health inpatient setting. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 15(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2019.003