ABSTRACT

Between 30 and 40% of 18-year olds in England, Wales and Northern Ireland enter tertiary education (university) each year. Young adulthood (ages 15 to 25) is the usual period in which problems with alcohol, drugs or other behaviors begin to emerge, and yet these issues have received limited study in the UK. Government policy dictates that a full continuum of treatment and recovery services should be available in each area of the country, but uptake of these services by university students appears to be limited. In this discussion paper we describe the background to, and components of, the Collegiate Recovery Program (CRP), an initiative that has grown rapidly in the USA in the past decade. We then describe how the first UK University-led CRP was set up, before outlining what has been learnt so far and the potential challenges facing this approach.

Introduction

In the UK most students start tertiary education at the age of 18 or 19, and between 30 and 40% of 18-year olds in England, Wales and Northern Ireland enter university each year (Bolton, Citation2024). Time spent at university represents a significant period of transition in the lives of young adults, and the university campus is an environment where cultural and environmental factors combine to promote increased frequency and intensity of psychoactive substance use (Moyle & Coomber, Citation2019; Rhodes, Citation2002). Engagement with rewarding behaviors such as substance use, gaming, gambling or use of pornography may become regular strategies for coping with difficult emotions. Although most students give these behaviors up as they move into jobs and adult roles (H. R. White et al., Citation2005), increasing use can also lead to the formation of habits which continue beyond tertiary education (Vasiliou et al., Citation2021). University students are less likely to develop an alcohol or drug (AOD) use disorder than non-student peers, but heavy use is associated with lower academic performance, increased likelihood of not finishing a course, unintentional injuries, increased rates of risky activities, legal problems, and an increased risk of substance use in adulthood (Skidmore et al., Citation2016).

AOD use by higher education students is not well researched in the UK (Boden & Day, Citation2023). A review of the UK prevalence literature found that the most common drug used by students was cannabis, with between 68 and 96% of respondents reporting lifetime use and 43–65% use in the past year (Holloway & Bennett, Citation2018). The latest (2021–22) survey in an annual series in the UK found 22% of students report drinking alcohol at least 2–3 times per week, but 37% never drink. Of the latter group, only 28% said this was due to religious or cultural reasons (Students Organising for Sustainability United Kingdom, Citation2023). Behavioral addictions are rarely considered in research with university students or in policy documents.

The UK provides treatment for AOD problems, and some behavioral issues (gambling, food addiction), free at the point of delivery. Each local authority in England has a dedicated service for young people, but this usually means people aged 18 or under. The Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) reported cuts of 37% to funding of treatment services for young people between 2013–14 and 2022, noting that treatment provision for this group was “patchy” and “not universal,” with “little systematic evidence of what worked” (Bowden Jones et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, although treatment is effective at helping individuals to achieve remission from AOD use disorders (Burkinshaw et al., Citation2017; Gossop et al., Citation2001), “recovery” is the organizing concept that aims to ensure that relapse is not the usual outcome (W. L. White, Citation2008). Recovery is “an intentional, dynamic, and relational process that involves sustained efforts to improve multiple aspects of wellness, and which may vary by individual, social, and experiential context” (Ashford et al., Citation2019).

Despite the frequency of AOD use disorders and behavioral problems, little is known about the prevalence, pathways and predictors of remission and long-term recovery among young adults (defined here as 18–25 years), and how this may contrast with recovery in older adults (Finch et al., Citation2020). Estimates of the number of students in recovery from addiction are hard to find, but three different sources of data allow a rudimentary calculation. Firstly, the Center for the Study of Addiction and Recovery (CSAR) at Texas Tech University estimated that 1.5% of the student population potentially require recovery support for alcohol use disorder each year (Harris et al., Citation2005). This translates to 301 people at an average UK university with 20,000 students. Secondly, the Drug Use in Higher Education in Ireland (DUHEI) study of nearly 13,000 students reported that 6.6% of participants had once had a problem with drugs or alcohol but no longer did (Byrne et al., Citation2022). This translates to 1,220 people at an average UK university with 20,000 students. Finally, in the UK National Recovery Survey, 5% of the population reported that they had overcome a problem with alcohol or drugs and 9% had overcome a problem behavior (listing compulsive shopping, food addiction, compulsive exercise, internet addiction, gambling, gaming or sex, love, or pornography addiction) (Day et al., Citation2023, Citation2024). Therefore, on an average campus 1000 students may benefit from recovery support for AOD problems and 1800 for behavioral addictions. Taken together, these findings suggest that between 300 and 1800 young adults may be trying to maintain remission from AOD problems or problem behaviors on an average UK university campus.

Collegiate recovery programs: definition and description of components

Tertiary education institutions in the USA have created services designed to support the student in recovery from addiction (Smock et al., Citation2011). Collegiate Recovery Programs (CRPs) were first developed on university campuses in the late 1970s, where a student in recovery was defined as a someone who “has a history of substance misuse that resulted in significant consequences in at least one life domain … [who] has made a voluntary commitment to a sober lifestyle and is actively engaging in activities that promote sobriety and overall wellness” (Perron et al., Citation2011). This definition could also include problematic behaviors such as gambling, gaming, use of sex or pornography, exercise, shopping or internet use. The early CRPs supported students to work steadily on their recovery process whilst also progressing toward a university degree. In 2005 Texas Tech University received US Government funding to document and export a model for recovery support services on campus. Effective service components of existing programs were put into a unified model termed the Collegiate Recovery Community (CRC, often used interchangeably with CRP) and widely disseminated. A rapid increase in the number of CRPs followed and estimates derived from the website of the Association for Recovery in Higher Education (ARHE) now put the number at more than 150 established or developing CRPs (Brown et al., Citation2018). Early data collection suggested that CRPs could promote recovery, prevent relapse, and improve educational outcomes for the individuals participating in them (Cleveland et al., Citation2007).

The primary goal of a CRP is to provide support for students who want to maintain abstinence from AOD or control of other problem behaviors (Harris et al., Citation2010). CRPs have developed in different ways depending on the social context in which they began, but key service elements are: (1) Recovery support facilitated by recovering students in conjunction with staff, with acceptance of all pathways to recovery. A safe, anonymous space on campus is important as a base for this activity; (2) Facilitation of substance-free, recovery-orientated social activities, as many social activities for university students take place in drinking or drug using contexts and social interactions are often facilitated by alcohol (Schulenberg & Maggs, Citation2002); (3) Educational support – some CRPs have a member of staff to assist with completing university admissions processes, oversee the orientation to university procedures in the first few weeks on campus, help develop individual plans of study, and provide general academic advice (completing forms, paying fees, registering for courses, developing study skills); (4) Building knowledge about addiction and recovery - staff facilitate a specific course for students focusing on relapse prevention, methods for building a positive social support network, health decision-making, conflict resolution skills, spiritual issues, time management, and general health and wellness; (5) Student peer mentors are trained to address both recovery and educational issues and may help new students with course administration and induction, campus orientation, and planning a personalized timetable for recovery support group attendance; (6) Community service - the recovery process often involves giving back to others, such as participating in fund raising for local homeless shelters and working with university-wide service projects; (7) Family support - parent and family weekends are a way of helping the student transition to a student life in recovery (Harris et al., Citation2007).

The evidence for CRPs

The research evidence base for CRPs is broad but not deep (Vest et al., Citation2021). Early work from Texas Tech University (TTU) showed that a CRP had a positive effect on students in recovery. Students from CRPs had a higher grade point average (3.18) than other students at the same university who were not in recovery (2.93), and the average graduation rate was 70% per year (compared to 60% in the university overall). Rates of relapse to addiction (defined as “any use”) were less than 8% per year (Harris et al., Citation2007), an important finding when compared with reported relapse rates of 60–79% in young adults in the first year post-treatment, and up to 90% within 5 years (Laudet, Harris, Kimball, et al., Citation2014).

The first cross-sectional nationwide survey of students engaged in a CRP included 486 participants from 29 different CRPs across the USA (43% female, mean age 26.2 years) (Laudet et al., Citation2015). Prior to joining the CRP most students had used multiple substances, experienced high levels of problem severity (including homelessness and criminal justice system involvement) and reported high rates of previous treatment and 12-step fellowship participation. The mean length of abstinence was three years, and participants often described being in recovery from, and currently engaging in, multiple behavioral addictions e.g., eating disorders, and sex and love addiction. One-third reported they would not be at university without the CRP support, and 20% would not have been at their current institution. CRP student retention and graduation rates exceeded that of the parent university by 5% and 21%, respectively (Laudet, Harris, Winters, et al., Citation2014).

Nearly half of the published academic literature about CRPs has used qualitative research designs (Vest et al., Citation2021). A meta-synthesis of such studies evaluating the impact of CRPs identified six “metaphors” that were central to their activity (Ashford, Brown, Eisenhart, et al., Citation2018): (1) Social connectivity: Active addiction leads to a breakdown in social connections and the CRP provides a ready-made group of people who have direct experience of the potential issues facing the student in recovery (Laudet et al., Citation2016; Scott et al., Citation2016; Washburn, Citation2016); (2) Recovery support: Timetabled events and services accommodate recovery needs within a CRP (Bell et al., Citation2009; Casiraghi & Mulsow, Citation2010; Kimball et al., Citation2017; Laudet et al., Citation2016; Washburn, Citation2016) including help and information to develop skills such as stress management, advocacy, building relationships, and relapse prevention techniques; (3) Drop-in recovery centers: A dedicated space on campus supportive of recovery provides a buffer to the dominant “partying” narrative of campus life and can provide support to cope with the stress of transitions and change; (4) Internalized feelings: These include identity, values, coherence, and development. Both the educational and recovery journey are marked by ongoing renegotiation of the identity process and value systems (Ashford, Brown, Eisenhart, et al., Citation2018); (5) Coping mechanisms: These include dealing with stress, resolving conflicts, improving emotional regulation, and other cognitive behavioral changes; (6) Conflict of recovery and student status: Intimate relationships, dating and social activities are particularly challenging. Success for individuals in recovery includes expansion into ever-widening social circles while navigating value conflicts.

The last decade has seen a significant increase in published research papers and academic dissertations on the topic of CRPs and 54 studies met the inclusion criteria for a scoping review published in 2021 (Vest et al., Citation2021). Primary outcomes were found to fall into four major domains: clinical outcomes (e.g. substance use or abstinence, cravings, co-morbid health conditions), recovery experience (students answered open-ended questions about their experiences), program characterization, and non-clinical student outcomes (e.g. stigma, grades, vocation). Numerous gaps in the literature were identified, including a lack of controlled trials and implementation science research designs, and limited study of sociodemographic differences among CRP students or co-morbid mental health issues. Conceptual models were rarely used to inform research design and data collection, although recent theoretical papers have proposed the potential application of socio-ecological (Vest et al., Citation2023) and recovery capital (Hennessy et al., Citation2022) models.

The development of a UK university-led CRP

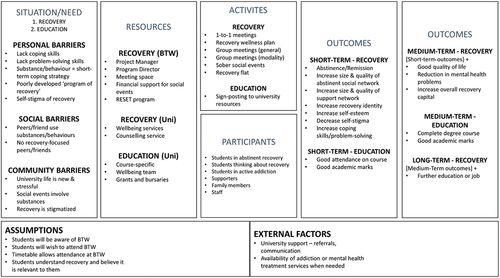

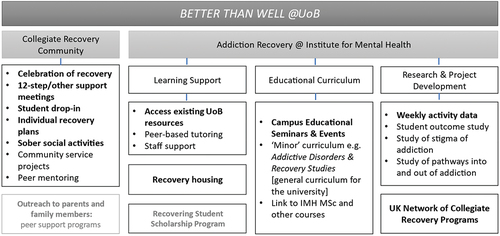

The university of Birmingham is a public research university that was the first English civic or “red brick” university to receive its own royal charter in 1900. The student population includes approximately 23,000 undergraduate and 12,500 postgraduate students making it the 7th largest in the UK out of 169. The concept of a CRP was originally pitched to the university in early 2020, supported by funding from a philanthropic donor. The plans were developed by a clinical academic specializing in treatment of addiction (ED) in close association with the university’s welfare and wellbeing service. The name CRP was used throughout the development process for consistency, but the term is less meaningful outside of a US context. The CRP therefore took on the name “Better Than Well” (BTW) in the early months of operation, a name chosen by the student participants. The original plan for the development of BTW is shown in .

Figure 1. A summary of the proposed elements of the CRP at the start of year 1 (September 2021). Components in operation as of December 2023 are in bold.

The main focal point of Better Than Well (BTW) was the weekly “Celebration of Recovery” meeting. This was the first component put in place and ran every single Friday following its inception in September 2021 (including university holidays). The 1-hour meeting was held in a large room in the main university building with simultaneous online access also available. It was open to anyone in recovery or interested in addiction or recovery and followed no one pathway to recovery. Participants suggested potential issues for discussion in advance, usually focusing on an area of recovery relevant to students or young adults. Students could attend The Lodge, a small but comfortably furnished building in a central location on the main campus. One-to-one sessions were available every day with the Program Manager (LT), either in-person or via a video platform. These sessions were available on demand and could be structured by the co-production of a recovery support plan. The Program Manager was a part-time postgraduate student at the university when BTW began and, as a member of two 12-step fellowships and a previous SMART Recovery facilitator, he was well connected with the recovery community in Birmingham beyond the university. A second weekly meeting was set up to loosely follow the format of a 12-step meeting by inviting a person in recovery to deliver a 20 minute “share” of their personal recovery story followed by a discussion of the issues raised. The Program Manager then accompanied students to a local 12-step fellowship meeting. Two weekly SMART Recovery groups were set up, one online and the other in-person on campus.

Sober social events were organized every month and funded by the CRP. These were activities chosen by the students that were fun, interesting, and away from a pressure to drink alcohol or use drugs. Examples included a meal at a local restaurant, a visit to an art gallery, 10-pin bowling, or an escape room. Events were organized each semester to present research on addiction-related topics on campus to an audience of staff, students, and local residents. One event on behavioral addictions incorporated presentations on sex or porn addiction and gambling and was live streamed as part of a university-wide festival. BTW recovery accommodation opened in January 2023. This was a 5-bedroom apartment on the university’s main residential site re-purposed as a recovery-focused residence by the accommodation services team. This meant that it was advertised as drug and alcohol-free with regular peer-support meetings. A first-year undergraduate student with seven years of abstinent recovery was asked to act as “senior peer” within the apartment and his accommodation fees were paid by BTW in recompense. Two other students moved in during its first semester of operation, and three further students requested to live in the recovery apartment when joining the university in September 2023.

The characteristics of the BTW community

Advice from colleagues in the USA suggested that a CRP would take five years to fully establish. The first two years (2021–23) unexpectedly exceeded all expectations as 61 students contacted BTW, of which 39 (64%) attended at least one program activity. By the end of the second year of operation the BTW community had grown to 24 students (see supplement). In some US CRPs recovery seminars form part of each student’s taught academic program and are compulsory to attend. In contrast, BTW sessions were voluntary and not part of the students’ weekly academic timetable. The supplementary document of demographic data illustrates the diversity of the student BTW members, including a range of ages, social backgrounds, ethnicity, religion, academic subject and year of study. The median age of participants was 22, with a median of 8 months in recovery. Participating students reported a wide range of substance or behavioral issues that had developed in a variety of ways, sometimes involving early trauma, coping with low mood, anxiety and other symptoms of mental ill health. The reported primary problem issue split evenly between alcohol, drugs and behaviors.

What have we learnt from the process of developing a CRP at a UK university?

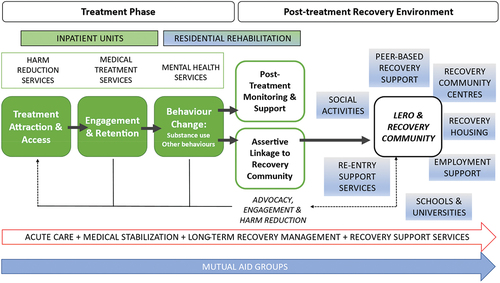

After two years of operation, BTW had become an established support network within the wider university community with a “secure base” (the Lodge) on campus and a daily network of peer support through regular group meetings, accommodation, sober social events, and an active WhatsApp group. The BTW project had demonstrated a demand for recovery support amongst a cohort of young adults attending university and created a strong foundation on which to build other initiatives to help students at different points in the “addiction spectrum” and continuum of care shown in . BTW also helped educate others about the issue, including staff, fellow students, the media, and the wider population of the city and the UK.

Figure 2. The Recovery Orientated System of Change (ROSC), presented as a continuum of care. Support from Mutual aid groups such as the 12-Step Fellowships may be an alternative to the treatment and recovery pathway, but acute care/medical stabilization, long-term recovery management and recovery support services must be available in every Local Authority in England. LERO = Lived Experience Recovery Organisations are peer-led organisations in the UK providing a range of recovery support services.

Problematic behaviors appeared to be just as prominent in the student population as issues with AOD. A third of BTW participants cited either sex, pornography, gaming, exercise, or overeating as their primary problem, and reported this behavior caused a similar level of distress as AOD. There are few treatment services available in the UK to tackle these issues, and students reported feeling more stigmatized than others with AOD problems. However, having made a decision to manage their problem behavior, this group found the peer support offered by BTW extremely useful, and attendance levels for this sub-population were high. The opportunity to talk about their struggles was often an emotional experience as it was rare that they had discussed them previously with anyone in their family, wider social network or the university.

Students often described using psychoactive substances or rewarding behaviors to cope with unhappiness or stress. This “dysphoria” was a prominent subject within BTW topic groups, which allowed the students to explore some of the psychological, social and emotional roots of their addiction. This narrative acted as a useful gateway for exploring the progression and dimensions of addiction across the life course. The process of understanding the nature of their addiction and the choice to focus on abstinence appeared to be potentially life changing for many of this cohort. The work that BTW students have done to build their recovery capital as young adults could potentially change the whole trajectory of their life.

Challenges facing young adults in recovery in the UK

Two significant challenges for young adults seeking recovery in the UK emerged during the development of BTW. The first challenge was the difficulty in accessing meaningful treatment and recovery support. UK universities have been uncertain about their role as provider of welfare services for their students (Jefford, Citation2024). Although the focus of this debate has been provision of mental health services, issues with AOD or other behaviors have long been ignored or minimized. The lack of data on student AOD use (Boden & Day, Citation2023) and on AOD use in young people in the UK in general (Bowden Jones et al., Citation2022) is alarming and acts as a further barrier to action. The median age of attendees at BTW (22) was considerably younger than cohorts studied in the USA (29) (e.g (Smith et al., Citation2024)), as was the median time in recovery (8 months vs. 48 months). Although some participants were older postgraduate students, two-thirds of participants were in the 18–25 age group. Also in contrast to the experience of programs in the USA (Laudet et al., Citation2015; Smith et al., Citation2024) many students at BTW had not received formal treatment and had made the decision to become abstinent whilst at university. It became apparent that the treatment services for young adults within the wider city focused on the criminal justice system or young people leaving the care system. The few students that attempted to access these services found that they did not understand or cater to their needs, and they often found them inaccessible or intimidating places. It is therefore important that the whole recovery orientated continuum of care is available to students in the future (see ) (Day, Citation2021). The implications of dropping out of a university degree course without a degree are potentially severe and are only likely to increase the severity of the harms in the short-term. In contrast, developing strategies and daily routines that promote wellbeing are potentially beneficial for all students. As such, a peer-support network scaffolded by the university may be an effective and cost-effective way of delivering all mental health services (Ashford, Brown, & Curtis, Citation2018).

A significant number of BTW students engaged with recovery programs (mostly 12-step fellowships) that sat outside the university. Some had found this recovery pathway prior to joining the university, but a majority embraced it after engaging with BTW. Several potential barriers for adolescent 12-step participation have been proposed (Nash, Citation2020; Sussman, Citation2010). Young people tend to have shorter substance use histories and fewer negative consequences of use, which may result in low problem recognition. A developmental need for autonomy may also lead young people to resist the 12-step concept of powerlessness. The average age of UK AA members is 54.7 (Alcoholics Anonymous UK, Citation2020) and worldwide the NA average is 42.7 (Narcotics Anonymous World Services Inc, Citation2012), and this age disparity with most students may lead them to feel unsafe or unable to relate to the life roles and experiences of older adults (Sussman, Citation2010). This issue is addressed by the formation of young people’s mutual help groups, but these are rare in the UK outside of London. However, it is possible that as the BTW community grows, participating students will start to organize these meetings beyond the campus.

The second challenge facing recovering students in Birmingham was the stigma of addiction, in common with the worldwide research findings in this area (Kilian et al., Citation2021; Nieweglowski et al., Citation2018). Students described being unable to talk about addiction and recovery with any of the important people in their lives: friends did not understand if they had not experienced similar problems, and parents were kept at a distance in a desire to resolve problems in a new “adult” role. They feared the university would ask them to leave (particularly if the issue was illegal drug use), and treatment services (including primary care) would record details on their medical record which may be shared with future employers. Stigma is often seen as having two distinct dimensions, public (external, enacted) and self-stigma (felt, internalized). Public stigma is associated with discrimination of individuals based on stereotypes which pervade public perception formed around inaccurate and insulting characterizations and assumptions. Self-stigma describes the internalization of the external stigma where the individual agrees with the stereotype (stereotype agreement), begins to believe it is a legitimate representation (self-concurrence) and suffers a significant loss of self-esteem (self-esteem decrement) (Corrigan et al., Citation2006). We observed that self-stigma could lead to a spiral of isolation and worsening use of AOD or problem behaviors. Public stigma caused damage on both personal and societal levels, and self-stigma in early or even long-term recovery was also profoundly debilitating.

The strongest evidence for strategies to overcome stigma comes from the mental health field (Corrigan et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017b). Although the academic literature on stigma reduction tends to focus on “anti-stigma” campaigns and education aimed at the public and particularly the public sector workforce (Lloyd, Citation2013), such education-based strategies are less helpful against self-stigma. A consensus report from the US National Academy of Sciences (NAS) concluded that “strategic disclosure” of mental illness can be effective in decreasing the harmful effects of stigma on the individual (National Academies of Sciences, E., and Medicine, Citation2016). We found that BTW students had very different levels of ability and willingness to disclose. Typically, those from a 12-Step recovery background were more confident and adept at sharing their experiences, having been engaged with a process of disclosure in the community prior to university. This could present problems for students adopting non-12-Step pathways to recovery, as members from other recovery backgrounds sometimes felt excluded. Our solution was to encourage cross-pollination of recovery ideas at every level of program delivery and community life. The bulk of this was done in the “all-recovery” celebration groups, a place for the free exchange and celebration of recovery ideas and journeys every week. This kind of open forum of ideas and experience meant that students learned and assimilated concepts and practice from each other, leading to narratives and opinions that were less homogeneous and rigid.

Conclusion

Alcohol or drug use, and other problematic behaviors such as gambling, are significant public health problems in young people. Time spent in tertiary education is potentially a useful developmental period for intervention in this area, whether this is harm reduction, treatment or recovery support. As described in the introduction, there are significant gaps in AOD disorder treatment provision for young adults in England, and the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the prevalence of mental health problems in the student population. This first description of a CRP supports the further study of recovery on campus in the UK as part of a continuum of care for AOD problems. The first two years of operation of Better Than Well have shown that a population of students exists that wish to remain abstinent from problematic substance use or behaviors, and that they benefit from peer support in this task. The implementation of the CRP model on a UK campus has face-validity, but a case for dissemination to other universities now needs to be made. The university of Birmingham has invested in the BTW program, providing the staff costs for the next three years. However, there is need to demonstrate both effectiveness and cost effectiveness of the model if it is to be sustained over the long-term and other universities are to follow suit.

Implications for further services and research

These findings support the further study of the CRP model in UK higher education institutions. As the network of CRPs grows (there are currently three – Birmingham, Teesside and Sunderland), it will be important to learn from the North American experience in evaluating their impact. Key variables must be collected at baseline, allowing longitudinal study of markers of remission and recovery. Qualitative methodology will be useful to understand the individual student perspective, and to detail how the UK experience differs from North America. The CRP is a system-level intervention that supports the individual to understand and utilize their own strengths and skills within a safe environment to practice recovery. Vest and colleagues have developed a social-ecological framework that conceptualizes the multifaceted factors that influence recovery in students (Vest et al., Citation2023). Such a theory-driven framework captures the levels of complexity of CRPs, combining individual interventions with intervention from multiple stakeholder groups (Vest et al., Citation2023). Recovery capital is another useful theoretical framework for understanding the CRP as it details the resources an individual could use in their recovery journey that the program facilitates access to (Hennessy et al., Citation2022). Work is underway to develop an evaluation framework based on the theory of change presented in . It will be important to understand the mechanisms underpinning the program, which may prove to be a laboratory for testing ideas about the process of recovery in the UK.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alcoholics Anonymous UK. (2020). AA membership survey 2020. https://www.alcoholics-anonymous.org.uk/download/1/documents/AA%20Membership%20Survey%202020.pdf

- Ashford, R. D., Brown, A., Brown, T., Callis, J., Cleveland, H. H., Eisenhart, E., Groover, H., Hayes, N., Johnston, T., Kimball, T., Manteuffel, B., McDaniel, J., Montgomery, L., Phillips, S., Polacek, M., Statman, M., & Whitney, J. (2019). Defining and operationalizing the phenomena of recovery: A working definition from the recovery science research collaborative. Addiction Research & Theory, 27(3), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2018.1515352

- Ashford, R. D., Brown, A. M., & Curtis, B. (2018). Collegiate recovery programs: The integrated behavioral health model. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 36(2), 274–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2017.1415176

- Ashford, R. D., Brown, A. M., Eisenhart, E., Thompson-Heller, A., & Curtis, B. (2018). What we know about students in recovery: Meta-synthesis of collegiate recovery programs, 2000-2017. Addiction Research & Theory, 26(5), 405–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2018.1425399

- Bell, N. J., Kerksiek, K. A., Kanitkar, K., Watson, W., Das, A., Kostina-Ritchey, E., Russell, M. H., & Harris, K. (2009). University students in recovery: Implications of different types of recovery identities and common challenges. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 27(4), 426–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347320903209871

- Boden, M., & Day, E. (2023). Illicit drug use in university students in the UK and Ireland: A PRISMA-guided scoping review. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 18(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-023-00526-1

- Bolton, P. (2024). Higher education student numbers. Research Briefing, Issue.

- Bowden Jones, O., Finch, E., & Campbell, A. (2022). Re: ACMD vulnerable groups – young people’s drug use. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/761123/Vulnerability_and_Drug_Use_Report_04_Dec_.pdf

- Brown, A. M., Ashford, R. D., Heller, A. T., Whitney, J., & Kimball, T. (2018). Collegiate recovery students and programs: Literature review from 1988-2017. Journal of Recovery Science, 1(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.31886/jors.11.2018.8

- Burkinshaw, P., Knight, J., Anders, P., Eastwood, B., Musto, V., White, M., & Marsden, J. (2017). An evidence review of the outcomes that can be expected of drug misuse treatment in England. Public Health England. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/drug-misuse-treatment-in-england-evidence-review-of-outcomes.

- Byrne, M., Dick, S., Ryan, L., Dockray, S., Davoren, M., Heavin, C., Ivers, J.-H., Linehan, C., & Vasiliou, V. (2022). The Drug Use in Higher Education in Ireland (DUHEI) survey 2021: Main findings. http://www.duhei.ie/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/duhei21.pdf

- Casiraghi, A.-M., & Mulsow, M. (2010). Building support for recovery into an academic curriculum: student reflections on the value of staff run seminars. In H. H. Cleveland, K. S. Harris, & R. P. Wiebe (Eds.), Substance abuse recovery in college: Community supported abstinence (pp. 113–144). Springer.

- Cleveland, H. H., Harris, K. S., Baker, A. K., Herbert, R., & Dean, L. R. (2007). Characteristics of a collegiate recovery community: Maintaining recovery in an abstinence-hostile environment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 33(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2006.11.005

- Corrigan, P. W., Schomerus, G., Shuman, V., Kraus, D., Perlick, D., Harnish, A., Kulesza, M., Kane-Willis, K., Qin, S., & Smelson, D. (2017a). Developing a research agenda for reducing the stigma of addictions, part II: Lessons from the mental health stigma literature. The American Journal on Addictions, 26(1), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12436

- Corrigan, P. W., Schomerus, G., Shuman, V., Kraus, D., Perlick, D., Harnish, A., Kulesza, M., Kane-Willis, K., Qin, S., & Smelson, D. (2017b). Developing a research agenda for understanding the stigma of addictions part I: Lessons from the mental health stigma literature. The American Journal on Addictions, 26(1), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12458

- Corrigan, P. W., Watson, A. C., & Barr, L. (2006). The self-stigma of mental illness: Implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25(8), 875–884. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2006.25.8.875

- Day, E. (2021). Illicit drug use: Clinical features and treatment. In E. Day (Ed.), Seminars in Addiction Psychiatry (pp. 65). Cambridge University Press.

- Day, E., Manitsa, I., Farley, A., & Kelly, J. F. (2023). A UK national study of prevalence and correlates of adopting or not adopting a recovery identity among individuals who have overcome a drug or alcohol problem. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-023-00579-2

- Day, E., Manitsa, I., Farley, A., & Kelly, J. F. (2024). The UK national recovery survey: a nationally representative survey of overcoming a drug or alcohol problem. British Journal of Psychiatry Open, 10(2), e67. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.654

- Finch, A. J., Jurinsky, J., & Anderson, B. M. (2020). Recovery and youth: An integrative review. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 40(3). https://doi.org/10.35946/arcr.v40.3.06

- Gossop, M., Marsden, J., & Stewart, D. (2001). NTORS after 5 years: Changes in substance use, health and criminal behaviour during the five years after intake.

- Harris, K. S., Baker, A., & Cleveland, H. H. (2010). Collegiate recovery communities: What they are and how they support recovery. In H. H. Cleveland, K. S. Harris, & R. P. Wiebe (Eds.), Substance abuse recovery in college, advancing responsible adolescent development. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1767-6_2

- Harris, K. S., Baker, A. K., Kimball, T. G., & Shumway, S. T. (2007). Achieving systems-based sustained recovery: a comprehensive model for collegiate recovery communities. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 2(2–4), 220–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/15560350802080951

- Harris, K. S., Baker, A. K., & Thompson, A. A. (2005). Making an opportunity for your campus: A comprehensive curriculum for designing a collegiate recovery community.

- Hennessy, E. A., Nichols, L. M., Brown, T. B., & Tanner-Smith, E. E. (2022). Advancing the science of evaluating collegiate recovery program processes and outcomes: A recovery capital perspective. Evaluation and Program Planning, 91, 102057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2022.102057

- Holloway, K., & Bennett, T. (2018). Characteristics and correlates of drug use and misuse among university students in wales: A survey of seven universities. Addiction Research & Theory, 26(1), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2017.1309031

- Jefford, W. (2024). ‘We won’t stop fighting for university duty of care’. BBC News. Retrieved February 17, 2024, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c516gx7p4ygo

- Kilian, C., Manthey, J., Carr, S., Hanschmidt, F., Rehm, J., Speerforck, S., & Schomerus, G. (2021). Stigmatization of people with alcohol use disorders: An updated systematic review of population studies. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 45(5), 899–911. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14598

- Kimball, T. G., Shumway, S. T., Austin-Robillard, H., & Harris-Wilkes, K. S. (2017). Hoping and coping in recovery: A phenomenology of emerging adults in a collegiate recovery program. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 35(1), 46–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2016.1256714

- Laudet, A. B., Harris, K., Kimball, T., Winters, K. C., & Moberg, D. P. (2014). Collegiate recovery communities programs: What do we know and what do we need to know? Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 14(1), 84–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533256X.2014.872015

- Laudet, A. B., Harris, K., Kimball, T., Winters, K. C., & Moberg, D. P. (2015). Characteristics of students participating in collegiate recovery programs: A national survey. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 51, 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2014.11.004

- Laudet, A. B., Harris, K., Kimball, T., Winters, K. C., & Moberg, D. P. (2016). In college and in recovery: Reasons for joining a collegiate recovery program. Journal of American College Health, 64(3), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2015.1117464

- Laudet, A. B., Harris, K., Winters, K., Moberg, D., & Kimball, T. (2014). Nationwide survey of collegiate recovery programs: Is there a single model? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 140, e117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.335

- Lloyd, C. (2013). The stigmatization of problem drug users: A narrative literature review. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy, 20(2), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2012.743506

- Moyle, L., & Coomber, R. (2019). Student transitions into drug supply: Exploring the university as a ‘risk environment’. Journal of Youth Studies, 22(5), 642–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2018.1529863

- Narcotics Anonymous World Services Inc. (2012). Narcotics anonymous 2011 membership survey. https://www.na.org/?ID=PR-index

- Nash, A. J. (2020). The twelve steps and adolescent recovery: A concise review. Substance Abuse: Research & Treatment, 14, 1178221820904397. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178221820904397

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. (2016). Ending discrimination against people with mental and substance use disorders: the evidence for stigma change. The National Academies Press: Washington DC.

- Nieweglowski, K., Corrigan, P. W., Tyas, T., Tooley, A., Dubke, R., Lara, J., Washington, L., Sayer, J., & Sheehan, L. (2018). Exploring the public stigma of substance use disorder through community-based participatory research. Addiction Research & Theory, 26(4), 323–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2017.1409890

- Perron, B. E., Grahovac, I. D., Uppal, J. S., Granillo, M. T., Shuter, J., & Porter, C. A. (2011). Supporting students in recovery on college campuses: opportunities for student affairs professionals. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 48(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.622

- Rhodes, T. (2002). The ‘risk environment’: A framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. International Journal of Drug Policy, 13(2), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0955-3959(02)00007-5

- Schulenberg, J. E., & Maggs, J. L. (2002). A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement(s14), 54–70. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54

- Scott, A., Anderson, A., Harper, K., & Alfonso, M. L. (2016). Experiences of students in recovery on a rural college campus: social identity and stigma. Sage Open, 6(4), 2158244016674762. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016674762

- Skidmore, C. R., Kaufman, E. A., & Crowell, S. E. (2016). Substance use among college students. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 25(4), 735–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2016.06.004

- Smith, R. L., Bannard, T., McDaniel, J., Aliev, F., Brown, A., Holliday, E., Vest, N., DeFrantz-Dufor, W., & Dick, D. M. (2024). Characteristics of students participating in collegiate recovery programs and the impact of COVID-19: An updated national longitudinal study. Addiction Research & Theory, 32(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2023.2216459

- Smock, S. A., Baker, A. K., Harris, K. S., & D’Sauza, C. (2011). The role of social support in collegiate recovery communities: A review of the literature. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 29(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2010.511073

- Students Organising for Sustainability United Kingdom. (2023). Students, alcohol and drugs survey 2022-23. SOS-UK. Retrieved December 15, 2023, from https://www.drugandalcoholimpact.uk/research/students-alcohol-and-drugs-national-survey-2022-23

- Sussman, S. (2010). A review of alcoholics anonymous/Narcotics anonymous programs for teens. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 33(1), 26–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278709356186

- Vasiliou, V. S., Dockray, S., Dick, S., Davoren, M. P., Heavin, C., Linehan, C., & Byrne, M. (2021). Reducing drug-use harms among higher education students: MyUSE contextual-behaviour change digital intervention development using the behaviour change wheel. Harm Reduction Journal, 18(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00491-7

- Vest, N., Hennessy, E., Castedo de Martell, S., & Smith, R. (2023). A socio-ecological model for collegiate recovery programs. Addiction Research & Theory, 31(2), 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2022.2123471

- Vest, N., Reinstra, M., Timko, C., Kelly, J., & Humphreys, K. (2021). College programming for students in addiction recovery: A PRISMA-guided scoping review. Addictive Behaviors, 121, 106992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106992

- Washburn, S. C. (2016). Trajectories, transformations, and transitions: A phenomenological study of college students in recovery finding success. University of St. Thomas. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss/76

- White, W. L. (2008). Recovery management and recovery-oriented systems of care: Scientific rationale and promising practices.

- White, H. R., Labouvie, E. W., & Papadaratsakis, V. (2005). Changes in substance use during the transition to adulthood: A comparison of college students and their noncollege age peers. Journal of Drug Issues, 35(2), 281–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204260503500204