Abstract

Problem identification: Loneliness is common after cancer, contributing to poor outcomes. Interventions to modify loneliness are needed. This systematic review describes the current literature regarding loneliness interventions in cancer survivors.

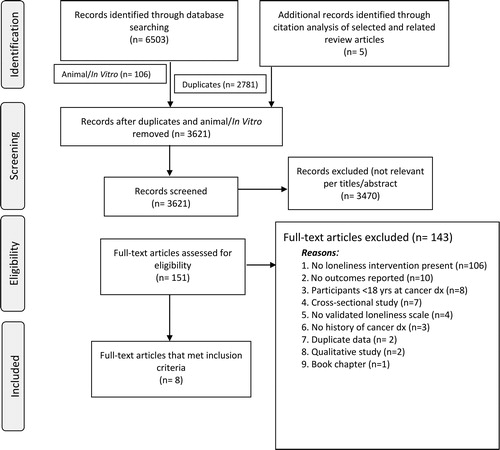

Literature search: Databases including: Ovid/MEDLINE; The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); Elsevier/Embase; Clarivate/Web of Science (Core Collection), EBSCO/PsycINFO, EBSCO/CINAHL were used to perform a systematic review of literature using PRISMA guidelines. Second, risk of bias, meta-analysis and a narrative synthesis approach was completed to synthesize findings from multiple studies.

Data evaluation/synthesis: Six thousand five hundred three studies were initially evaluated; eight studies met inclusion criteria. Findings indicate a paucity of interventions, generally of lower quality. Interventions were feasible and acceptable; those interventions with cultural modifications were more likely to demonstrate effectiveness.

Conclusions: There are limited interventions addressing loneliness in cancer survivors. Development and testing of culturally-relevant programs are warranted.

Implications for psychosocial oncology: Current studies suggest the psychosocial symptom of loneliness is modifiable among adult cancer survivors. Few interventions have been tested and shown to be effectiveness in cancer survivors in the U.S. and none have been tailored for older adult survivors, by patient gender/sex and few for specific race/ethnic groups. Results from this systematic review: a narrative synthesis and meta-analysis can inform future interventions targeting loneliness in this growing, yet vulnerable, adult cancer survivor population.

Introduction

In the United States (US), there are an estimated 16.9 million cancer survivors, with predictions reaching above 20 million survivors by 2026.Citation1,Citation2 A person is considered a cancer survivor from the time of diagnosis until the end of life.Citation3 Within this increasing population, adults make up a significant proportion of this survivorship group. Cancer diagnoses are associated with unique and at times profound psychological and physiological symptoms, particularly among older survivors.Citation4 One of the frequent symptoms is loneliness.Citation5 Loneliness, defined as “the perceived experience of deprived social contract or relationships,” has been observed as a unique experience among cancer survivors as compared to other groups.Citation5,Citation6 Loneliness can be exacerbated in individuals with lower social support, however, social support is discriminately different in that social support refers to the availability of interpersonal resources.Citation6 Notably, increasing levels of loneliness are correlated with the absence of social support.Citation7

Loneliness is a serious and often unidentified psychosocial symptom among adult cancer survivorsCitation5which has been associated with diminished health outcomes and even all-cause mortality after cancer.Citation8,Citation9 More specifically, evidence suggest that cancer survivors whom have greater loneliness have higher levels of depressionCitation10 and loneliness further predicts numerous physiological responses including poorer immune function, higher pain, sleep disturbance, functional decline and fatigue.Citation10–13 These adverse consequences of loneliness should not be taken lightly among cancer survivors, particularly those of advanced age wherein concurrent chronic conditions may exacerbate loneliness while also contributing to greater needs in relation to survivorship care.Citation9,Citation10,Citation14 Given that evidence has supported interventions targeting loneliness in adults more generally,Citation15 research ought to purposefully aim to expand on the current limited studies addressing loneliness in cancer survivors, a population with potentially even greater risk and ramifications for loneliness.Citation10 Thus, establishing effective interventions to address loneliness in cancer survivors is likely to improve their overall health.

As a first step toward mitigation of loneliness among cancer survivors, it is vital to identify, enumerate, and describe the current state of the evidence in regard to interventions and their effectiveness in decreasing loneliness. The overall goal of this systematic review is to describe the current literature related to interventions targeting loneliness in adult cancer survivors. Quantifying the number of interventions targeting loneliness among cancer survivors was of importance as evidence supports the strong correlation between loneliness and mortality in the general population.Citation16 Further, we detail specific characteristics of interventions, expand on those descriptions by describing behavioral theories and/or theoretical constructs incorporated into loneliness interventions, all in order to inform the design of future interventions targeting loneliness. Given that many deleterious outcomes are associated with loneliness,Citation14,Citation16–18 and the pervasiveness of cancer incidence is high in adults,Citation19 it is important to gain a greater understanding of intervention effectiveness toward mitigating loneliness. To quantify that degree of effectiveness, a meta-analysis of treatment efficacy was conducted.

Research objectives

The purpose of this systematic review is to identify, critically assess, present key components, summarize, and synthesize interventions that aim to reduce loneliness in adult cancer survivors. These objectives are pursued by: 1) detailing the specific characteristics of interventions reducing loneliness in adult cancer survivors including: the population characteristics, the study length, loneliness measures collected, and key results; 2) providing an expanded description of the individual intervention components and characteristics including delivery mode, treatment length, number of sessions, behavior theories and constructs applied; 3) conducting a meta-analyses of post-treatment effect sizes of self-reported loneliness across each of these interventions; and finally 4) offering a narrative summary and synthesis of the systematic review findings to improve the understanding of influential factors relative to loneliness intervention effectiveness.

Methods

The research protocol developed for this review followed recommendations defined by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses,Citation20 registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO 2019 CRD42019133886, 2019).

Eligibility criteria

Studies were selected in accordance with the following inclusion criteria:

Participants were adult (age ≥18 years) survivors of any type of cancer. The study being developed is focused on adult cancer survivorship experiences, which are different from those of childrenCitation21; a separate study for children that examines their unique developmental experiences should be created to accommodate their distinct needs.

The intervention utilized in the study had to primarily or secondarily (intervention to directly intervene and address loneliness) include strategies to reduce loneliness as reported by cancer survivors, or as part of a multi-component intervention in which the data associated to the loneliness components could be identified. Second, studies were only included if loneliness was measured with a validated loneliness scale (e.g., UCLA Loneliness Scale,Citation22 De Jong Gierveld Scale,Citation23 R-UCLA Loneliness Scale Version 3Citation24).

To be included, studies had to be interventions (e.g., controlled trials, or pre-post trials) in a peer-reviewed and published format. Observational studies (e.g., cohort studies, case-control studies, case series, case reports, or cross-sectional) were excluded. Book chapters, dissertations, meta-analyses, protocol papers, reviews, and systematic reviews were also excluded.

Studies had to include loneliness as one of the reported outcomes in order to be included in the analysis.

Searches

For purposes of evaluation and reporting of this systematic review, adherence to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)Citation20 was followed. An information specialist (CLH) conducted searches in the following databases: Ovid/MEDLINE; The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); Elsevier/Embase; Clarivate/Web of Science (Core Collection), EBSCO/PsycINFO, EBSCO/CINAHL, and ClinicalTrials.gov. All databases were searched on May 13, 2019 with no date restrictions on the publication, in addition to an English language filter applied. The Ovid/MEDLINE search strategy and terms are detailed in Supplementary material and analogous to the searches for the remaining databases. References from relevant reviews as well as references to and from the final selected publications for this review were also searched.

Selection of qualifying studies

Upon completion of extraction of records from the databases, records were then transferred to EndNote Version X9 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), a citation management platform. Any replicate records were documented and removed. Independent reviewers (JJM and MBS) screened all titles and abstracts for relevance utilizing Endnote. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus, and if needed, consultation with the senior author (CAT). Next, full texts of all references meeting the primary screening criteria were independently screened for inclusion by reviewers (JJM and MBS) following the specific inclusion/exclusion criteria outlined. Disagreements were resolved by consensus and with discussion with the senior author (CAT).

Collection of data and management

Data management followed recommendations for data extraction as outlined in The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions v. 5.1Citation25 and followed a pre-defined coding sheet in REDCap,Citation26 an online data management tool to extract and analyze data. The following data were extracted/documented for each study that met the stated inclusion criteria: date reviewed, citation, reasons for inclusion or exclusion, research design, source of research, research study length, sample size, demographics of participants (age, sex, race/ethnicity, etc.), cancer diagnosis, location of research study, types of intervention groups, intervention specifics, details about comparison group, if utilized, and details of the intervention outcomes. Any theoretical models, behavioral theories or constructs used in the interventions were similarly extracted and detailed if employed in the intervention. Alongside the platform of intervention delivery structure (e.g., telephone, in person at the clinic, or WebCT-delivery, etc.), research participant engagement (e.g., family, caregiver or dyad) was extracted. Any secondary outcomes targeted by the intervention on (e.g., anxiety/depression, psychological well-being), or health behaviors (e.g., physical activity) and quality of life (e.g., social interaction and support) were comprehensively explicated.

Evaluating study quality and bias

Studies were critically assessed following the Downs and Black Study Quality checklistCitation27 to evaluate the quality of the studies concerning the external and internal validity. Predetermined scoring of study quality from this checklist established the following cut points: 0: “none,” 1–3: “very low,” 4–6: “low,” 7–9: “moderate,” 10–12: “high,” and 13–15: “very high.” The five study quality domains included: 1) Reporting (8 items), 2) external validity (2 items), 3) internal validity—bias (3 items), 4) internal validity—confounding (1 item), 5) power (1 item). Predetermined scoring of study quality from this checklist has the following cut points: 0: “none,” 1–3: “very low,” 4–6: “low,” 7–9: “moderate,” 10–12: “high,” and 13–15: “very high.” The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: The Cochrane Collaboration’s ‘Risk of Bias’ toolCitation25 guided the evaluation of the research study bias. Both reviewers JJM and MBS assessed this bias by evaluating the following for each study included: selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting, and other bias by the ranking of “high risk” (–) to “low risk” (+) on seven domains.

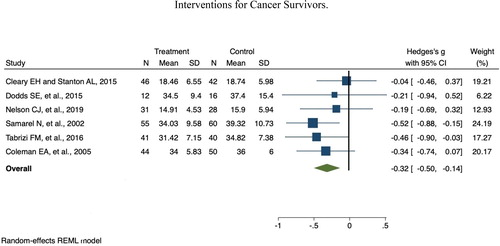

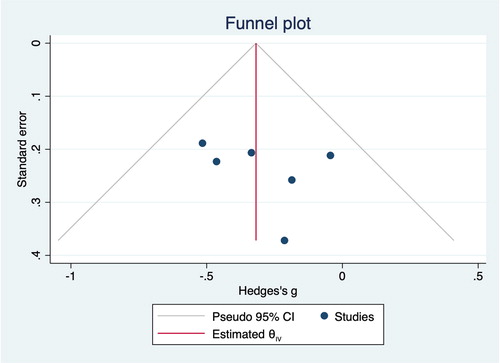

Meta-analysis

In the quantification of the effects of interventions on loneliness in cancer survivors, standardized mean differences between treatment and control groups were estimated using small sample size corrected Hedge’s g statistics and were synthesized across studies using a random-effects model. Heterogeneity of the studies was measured using restricted maximum likelihood estimates, reported as the I2 statistic. Missing standard deviations were computed using available standard errors (SE = σ/√n). Although heterogeneity statistics indicate the absence of a significant amount of heterogeneity across studies, we have decided to conservatively meta-analyze the effect sizes using a random-effects model to avoid the possibility of an inflated Type I error. Risk of bias related to small-study effects were evaluated using a funnel plot of effect size estimates and Hedge’s g and Egger’s test for small study effects using random-effects. All analyses were conducted using the meta package available in Stata 16.0 (Stata Corp, LLC, Cary, NC, USA).

Narrative synthesis of intervention components

Following the Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews,Citation28 a narrative synthesis was completed of included intervention components (). A narrative synthesis purposes to summarize and explain findings related to the effects of the intervention alongside factors which may influence the implementation of the intervention. A preliminary synthesis of findings of the included studies was explored for relationships within the data while evaluating the robustness of the data.Citation28 Study data were further processed and organized into groups to provide categorial descriptions while concurrently assessing patterns within and across the studies. This process also allows for the identification of any influencing factors on the effectiveness of loneliness interventions for adult cancer survivors ().

Table 1. Characteristics of interventions (N = 8): description of participants, intervention, measurements and significant findings.

Results

In all, 6503 records were found searching the following databases: Ovid/MEDLINE (n = 953); The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (n = 302); Elsevier/Embase (n = 2639); Clarivate/Web of Science (Core Collection) (n = 1567), EBSCO/PsycINFO-461, EBSCO/CINAHL (n = 581) and ClinicalTrials.gov. (n = 0), in addition, five publications were included from relevant review articles. After 2781 duplicates and 106 animal/in vitro studies were removed, a total of 3621 publications remained (). From this, 3470 citations were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria based on review of titles/abstracts. Of the 151 articles left for full-text review, texts which did not meet inclusion were excluded due to: loneliness not being a primary or secondary outcome in the intervention (n = 106), no outcomes reported (n = 10), age of participants <18 years at cancer diagnosis (n = 8), cross-sectional observational study (n = 7), no validated loneliness scale utilized (n = 4), participants did not have a history of a cancer diagnosis (n = 3), duplicate studies (n = 2), qualitative study (n = 2), or a book chapter (n = 1). A total of eight studies met the inclusion for this review.Citation29–36

Characteristics of studies

Of the eight included studies offering loneliness outcome measures (Nelson et al. (2019)Citation29; Rigney et al. (2017)Citation30; Tabrizi et al. (2016)Citation31; Dodds et al. (2015)Citation32; Cleary et al. (2015)Citation33; Coleman et al. (2005)Citation34; Fukui et al. (2003)Citation35; Samarel et al. (2002)Citation36) seven were randomized control trials (RCT) and one had a pre-post pilot evaluation study design.Citation30 Key study characteristics are reported in . Of the eight studies, two were conducted outside of the U.S. in IranCitation31 and Japan,Citation35 while the remaining were conducted within the U.S.Citation29,Citation30,Citation32–34,Citation36 U.S. studies were funded either by foundation or federal funding.Citation29,Citation30,Citation32–34,Citation36 Both international peer reviewed publications were funded by their respective universityCitation31 and the other studyCitation35 was funded through their country’s Ministry of Health and Welfare with supplementary federal grant funding. The duration of interventions varied, ranging from 6 weeksCitation35 to 13 months; only two studies were longer than 12 months.Citation34,Citation36 While all studies reported a baseline assessment of loneliness, follow-up time points ranged from immediately following the intervention to six-months postintervention.

Modality of study delivery was diverse; four were in a group format,Citation30–32,Citation35 three were one-on-one telephone based,Citation29,Citation34,Citation36 and one study was delivered as a one-on-one internet-based platform.Citation33 Recruitment for study participants most frequently took place at university cancer centers, followed by initiatives from local cancer support groups and community-based clinics. Interventions presented wide-ranging age distributions representing participants 18 to 83 years old, with only one study specifically designed to target loneliness in older adult cancer survivors ≥70 years of age.Citation29 The U.S. based studies were somewhat homogeneous in terms of sample race and ethnicity, as participants were predominantly college educated non-Hispanic white (NHW) women.Citation29,Citation30,Citation32–34,Citation36 All interventions reported institutional review board approval; with the exception for a program evaluation of a lung cancer support group, wherein informed consent was collected.Citation30

Meta-analysis findings

Out of the eight studies included in this systematic review, sixCitation29,Citation31–34,Citation36 were included in the meta-analysis. Reasons for exclusion included not reporting adequate data to include in a meta-analysis (n = 2).Citation30,Citation35 Samarel et al.,Citation36 had two control groups, for this meta-analysis the means and standard deviations from the true control group and true intervention group were used. The total pooled analysis represented 465 cancer survivors. presents results of the meta-analysis of interventions effects on loneliness in cancer survivors. The overall Hedge’s g was –0.32 (95% CI: –0.50 to –0.14, p < 0.001) indicating interventions overall had a significant effect on reducing loneliness for cancer survivors. Heterogeneity of the effect sizes was tested with Cochran’s Q and the I2 statistic. Cochran’s Q = 5.99, p = 0.31, indicating nonsignificant heterogeneity in effect sizes over the studies. However, Q has low statistical power especially when the number of studies is small as in this case. The I2 between studies was 16.58%, also indicating low heterogeneity between studies.Citation37 This indicates that just over 16% of the variance in the observed effects is due to variation in true effects.Citation38 A funnel plot of Hedge’s g and standard error of studies included in the meta-analysis are displayed in (). Egger’s test for small studies effects of publication bias indicated no significant bias (p = 0.51).

Risk of bias assessment

Studies were critically assessed following the Modified Downs and Black Study Quality checklistCitation27 to evaluate the quality of the studies apropos the external and internal validity. These scores are provided in . Five of the eight studies received “very high” scores for study quality,Citation29,Citation31,Citation32,Citation35,Citation36 two studies received “high” scores,Citation33,Citation34 and one studyCitation30 received a “low” score. Adhering to The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: The Cochrane Collaboration’s ‘Risk of Bias’ tool,Citation25 five of the eight studiesCitation29,Citation32–34,Citation36 presented a low risk of bias. One studyCitation35 lacked blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessments while another studyCitation31 revealed reporting bias. The final studyCitation30 receiving high risk of bias across all categories, including lack of disclosure of funding source, may have been due to the non-reported data by reason of the restricted reporting space offered as part of the conference abstract space allocation.

Table 2. Assessment of study bias.

Results of studies

The overall results of this systematic review support current interventions in terms of feasibility and acceptability among cancer survivors but demonstrate less evidence in support of effectiveness in modifying loneliness in cancer survivors. In all studies, loneliness was measured using the UCLA Loneliness Scale or versions of this instrument. The original scale consists of 20 items, scoring from 20 to 80, higher score indicating greater feelings of loneliness.Citation24 Revised versions are similar in scoring with a refinement of items in the scale via simplifying the response format and wording. Among the interventions, both international studiesCitation31,Citation35 (utilizing validated translated scales in study-specific language) found a significant reduction in loneliness compared to only one study in the U.S.Citation33 Of the eight studies reviewed, one reported significantly reduced loneliness scores six-months postintervention with several studies finding a significant mediating role of loneliness for improvement of other psychosocial problems. The Cleary et al. (2015)Citation33 study showed that loneliness six-months postintervention mediated improvement in participants’ depressive symptoms.

Narrative summary of intervention delivery mode

Research shows that enhanced social support is among the most prevalent and influential ways of reducing loneliness.Citation13,Citation39 Of the eight studies included herein, four studies were group-based,Citation30–32,Citation35 three were telephone-based,Citation29,Citation34,Citation36 and one study was web-based,Citation33 offering a varied group of delivery formats. Of these, four studies had survivors participate in an in-person support group-based discussion while the other studyCitation32 offered in-person group Cognitively-Based Compassion Training (CBCT) sessions. Rigney et al. (2017)Citation30 evaluated in a pre/post design support group participation among lung cancer survivors (Gilda’s Club Nashville; n = 20 with an average age of 54.8) for loneliness, quality of life, and program engagement. Preliminary results showed a significant decrease in overall distress (p = 0.0067) following group participation, but no change in loneliness was found. Only 50% of participants completed the intervention and follow-up survey. Tabrizi et al. (2016)Citation31 looked at the effects of a 12-week 90-minute unstructured supportive-expressive discussion group on loneliness, hope, and quality of life in 41 Iranian breast cancer survivors. Based out of north-western Iran, this intervention was culturally tailored to incorporate cultural norms and structure to create an opportunity whereby the women felt they could share information.Citation31 Researchers found a significant reduction in loneliness scores over the study period (F = 69.85, p < 0.001). Fukui et al. 2003Citation35 examined the effect of a psychosocial group-based intervention on loneliness and social support for 25 Japanese women (average age: 53.6 ± 7.0). Investigators applied a conceptual frameworkCitation40 to their culturally appropriate intervention model. Findings showed a significant reduction in loneliness with the experimental group demonstrating an average of –2.7 (36.6 ± 7.2 baseline to 33.7 ± 8.5 on six-week follow-up) decrease in loneliness score as compared to wait-list control group with a mean change score of –0.1 (32.8 ± 6.8 baseline to 32.7 ± 8.2) during the same time frame. At six months, the experimental group showed an additional reduction in loneliness score, on average, of –0.2, while the control group showed a 1.2 increase in loneliness score. Of note, participants with highest participation were significantly older than those with lower participation (53.6 ± 7.0 years vs. 50.0 ± 8.6). Factors influencing participation included childcare concerns and difficulty accessing the hospital where the intervention was held. Lastly, Dodds et al. (2015)Citation32 pilot-tested the feasibility of an intervention with weekly, two-hour classes over eight weeks plus booster CBCT group sessions four weeks later in 33 breast cancer survivors. Results showed that the intervention was feasible and satisfactory to participants. When compared to wait-list controls, both groups showed a decline in loneliness score that was not significantly different by treatment arm (decrease of 3.8 and 3.3, intervention vs. control, respectively) during the intervention.

Telephone interventions are commonly used to navigate any potential barriers to participation related to transportation. Three of the eight interventions implemented a telephone-based program, in which participants were randomized to receive either psychotherapyCitation29 or social support with education that included efforts to reduce loneliness.Citation34,Citation36 Nelson et al. (2019)Citation29 developed a telephone-based psychotherapy intervention specifically designed to alleviate distress, and addressing loneliness, in older (≥70 years old) adult cancer patients. The intervention included 31 older adult cancer patients who completed five sessions of psychotherapy over seven weeks. These sessions were based on two well-established theoretical models: Erikson’s developmental model of psychosocial tasks related with the later stages of life and Folkman’s cognitive model of coping,Citation41,Citation42 to encompass approaches best suited for older people with cancer; followed by evaluation by an expert panel of older adults with cancer in which they provided feedback for researchers to make additional modifications prior to program implementation. Through these approaches, feasibility was demonstrated and positive but no significant reductions in loneliness (p = 0.21) were reported. Both Coleman et al. (2005)Citation34 and Samarel et al. (2002)Citation36 offered multi-phase social support and education via telephone to women diagnosed with breast cancer. In the Samarel et al.’s study,Citation36 no difference in cancer-related worry or well-being, including loneliness, was found. In both studies no variance was noted as a function of whether a participant received telephone support alone or combined with in-person group social support and education.Citation34,Citation36 However, the intervention delivered by Samarel et al.Citation36 did reduce loneliness scores by an average of 2.7 at 16-weeks, a reduction that was attenuated to 1.9 at 50 weeks, while the second control group showed a rise in loneliness during the initial 8-10 weeks of intervention. Both Coleman et al., 2005 [34] and Samarel et al., 2002 [36] interventions were guided by the Roy Adaptation Model of Nursing.Citation43

Of the studies, only one applied a web-based approach for delivery, and that was the single study with positive findings related to a reduction in loneliness. Women included in this study were diagnosed with invasive or metastatic breast cancer (n = 88; age range: intervention: 55 ± 12 (28–76) vs. control: 56 ± 10 (37–76) years), and were randomly allocated to take part in a three-hour workshop to create a personal website (Project Connect Online, PCO) or a wait-list control condition. The personal websites consisted of blog postings where participants could post relevant personal photos, journal posts, and a page for visitors to potentially take action on posted requests page (“How You Can Help”). All participants were trained in basic computer skills and how to get online to complete searches. Analyses showed a significant reduction in loneliness and an increase in perceived social support. Loneliness significantly mediated the relationship between the participant’s depressive symptoms and the PCO intervention (B = –1.34, SE = 0.91, 95% CI [–3.84 to –0.06]). A total of 86% (n = 76) of the participants randomized completed the one-month and six-month assessment.

Narrative synthesis of intervention components

As part of the narrative synthesis, we explored the data extracted and the main findings from the review are highlighted in (). Each characteristic of the interventions was organized into groups by intervention type, intended outcomes, and mechanisms by which loneliness was targeted. In our integrative review four overarching categories related to intervention type were identified which included: 1) enhancing social support (i.e., the intervention aim offered consistent contact or companionship), 2) social access (i.e., the intervention increased prospects for participants to partake in social contact such as online or group-based activities), 3) social cognitive training (i.e., the intervention aim was changing participants’ social cognition), and 4) social skills training (i.e., the intervention aim was improving participants’ interpersonal communication skills). While the included studies were limited in number, at least half resulted in reduced loneliness scores.Citation31,Citation33,Citation35,Citation36 Of the included studies, five were categorized as enhancing social support,Citation30,Citation31,Citation34–36 one as enhancing social access,Citation33 one social cognitive training,Citation32 and one as social skills training.Citation29 Key characteristics, thematic synthesis of design type, and intervention main findings of included studies are detailed in . Results from our narrative synthesis inform us on approaches to consider when planning future loneliness interventions for adult cancer survivors.

Of the eight studies included, various approaches were presented to reduce loneliness among cancer survivors. Two international studiesCitation31,Citation35 were modified to the unique cultural populations offering culturally tailored participatory methodologies. Five studies offered health education and social support (group and individual formats).Citation30,Citation31,Citation34–36 One study included psychotherapy counseling,Citation29 and another cognitively-based training.Citation32 It is important to note that among these interventions, there was large variability in effectiveness in terms of reducing loneliness. Telephone-based psychotherapy aimed at older adults (≥70 years old) was deemed feasible and accessible in one study;Citation29however, only a small effect on loneliness was found (d = 0.19 [CI: –0.34 to 0.72], p = 0.21). This was despite the fact that study content was developed, evaluated and revised with input from an expert panel of older adult cancer patients and survivors. Of note, this was the only intervention specifically designed for older adult cancer patients. In Cleary et al.,Citation33 a significant reduction in loneliness was demonstrated among breast cancer survivors and was shown to be a significant contributing factor related to positive adjustment to breast cancer in participants. Cleary et al.’sCitation33 PCO workshop offered statistically significant sustained benefits in regard to loneliness six months after the workshop. Perceived support from friends and coping self-confidence similarly increased.Citation33

Several implementation strategies, intervention components and characteristics including delivery mode, treatment length, number of sessions, behavioral theories and constructs applied seemed to influence the effectiveness and also varied appreciably across study settings. For example, five of the eight studies incorporated behavioral theory or models. These included Action Theory and Conceptual Theory,Citation33 Roy Adaptation Model of Nursing,Citation34,Citation36 Conceptual Framework of Stewart et al.,Citation40 and Social Learning (Cognitive) TheoryCitation35 and one study incorporated two aging models (Folkman’s Cognitive Model of Coping, Erikson’s Developmental Model of Psychosocial TasksCitation29) to better adapt efficient and effective methodologies aimed at older adults with cancer.

Timing of intervention relative to cancer diagnosis was an additional feature/component of the study that was evaluated herein. The studies that offered specific details on timing of intervention (most with education and social support) suggested that most frequently interventions were offered four months or later after primary treatment.Citation31,Citation34–36 For example, Samarel et al.Citation36 recruited women with Stage 0–III breast cancer early post breast surgery, but initiated the loneliness reduction intervention at 16 weeks. At Phase I (weeks 16–18) there was a demonstrated reduction in loneliness, followed by an additional reduction during Phase III (weeks 50–52). In another study by Tabrizi et al.Citation31 there was a significant reduction in loneliness scores over the study period among breast cancer survivors who were 4–18 months postsurgery (intervention group: 34.15 (8.45) baseline; 31.42 (7.15) postintervention; to 30.89 (6.94) at the eight-week follow-up assessment and the control group: 34.82 (7.38) baseline; 34.82 (7.38) postintervention; to 34.87 (7.43) at the same time frame). A similar recruitment time period was used by Fukui et al.,Citation35 also among early stage breast cancer patients, and also demonstrating a reduction in loneliness scores which was consistent over all successive assessment time points.

Discussion

The objective of this review was to provide a current appraisal of effective interventions aimed at improving loneliness among adult cancer survivors. The search resulted in eight studies, which represented several intervention modalities and variations in intervention components of interest. The findings highlight an overall lack of studies in adult cancer survivors, particularly studies with large samples that had adequate, statistical power. The meta-analytic findings revealed relatively modest and homogeneous effects of the interventions for reducing loneliness in cancer survivors. The modest effect of loneliness interventions in cancer survivors is comparable to that of other psychosocial interventions for positive affect, depression, pain, and fatigue.Citation44,Citation45

On review of demographic factors, the studies conducted in the U.S., recruited homogeneous samples of predominantly non-Hispanic, Caucasian and female participants. In fact, samples largely represented college-educated women.Citation29,Citation30,Citation32–34,Citation36 Furthermore, interventions that were evaluated primarily enrolled women younger than ≤65 years of age, while only one studyCitation29 explicitly recruited those who were age ≥70 years, despite the likelihood that advanced age combined with a cancer diagnosis further amplifies risk for loneliness. With an anticipated 73% (26.1 million) of survivors aged 65 years and older by 2040, there is a need for interventions serving survivors of advanced ageCitation1 in order to address their unique aging-related psychosocial concerns, including loneliness. Additional features remain largely unaddressed in the current literature including, the need to address loneliness in individuals of lower socio-economic status and under-represented culturally diverse groups. Yet, literature suggests loneliness may be higher in these groups.Citation13 Of note, these groups are the more understudied in broader cancer survivorship research, which may be in part due to difficulty attaining diverse samples via conventional recruitment methods.Citation46 Efforts to decrease disparities in survivorship care should further consider cultural variables (e.g., language, appraisal of the healthcare system), resources and access to care in future explorations of interventions aimed at loneliness mitigation for cancer survivors.

It is clear that this published literature does provide preliminary evidence of intervention feasibility, acceptability, and to a more limited extent, effectiveness, yet, with the representation of only small sample of survivors it is difficult to robustly extrapolate information to the broader cancer survivor population. The U.S. studies included in our review consistently found lower loneliness scores with intervention, although only one achieved a statistically significant reduction when compared to a control condition. Small sample sizes (n = 20 to 125 subjects) likely reduced statistical power to robustly evaluate intervention effects. Importantly, our results are supported by other reviews evaluating interventions for loneliness reduction in adults without a prior diagnosis of cancer.Citation47

Across studies, variable delivery formats were used to address loneliness. Variability may be intentional as interventions are tailored to local needs (characteristics which may influence outcomes of interest such as age related to means of mobility and transportation, race related to cultural acceptance and uptake, and socio-economic status influence on participant resource constraints). Programs delivered via the telephone or internet-based platforms showed greatest reductions in loneliness;Citation29,Citation33,Citation36 face-to-face interventions, generally, showed less favorable results. In fact, no change in loneliness score was reported in the two face-to-face studies in the U.S.Citation30,Citation32 Outcomes from Cleary et al.Citation33 indicate that interventions delivered by web-based platforms were able to mediate psychosocial well-being, including loneliness, for cancer survivors, even among older cancer survivors, suggesting this modality should be further evaluated in future interventions. Participants assigned to PCO intervention, showed a decrease in loneliness while increasing both perceived support from friends and coping self-confidence. Importantly, these promising web-based findings have been found in other interventions aimed at alleviating loneliness in non-cancer survivor samples.Citation48 Of note, the studies that were developed did not consistently include a behavioral theory-based framework to intervene on loneliness, despite broad literature supporting the application of behavioral theory to interventions.Citation47 The somewhat limited application of theoretical approaches relevant to cancer survivors could have influenced the effectiveness of select interventions described herein. In fact, three studies did not describe a behavior theory to the workCitation30–32 and of those, two were not effective in reducing loneliness among cancer survivors.Citation30,Citation32

Studies seemed to vary in terms of feasibility given the wide differences in study attrition rates. Rigney et al.Citation30 reported a high attrition rate of 50% at the six-month follow-up time point for the face-to-face based intervention, while the study by Fukui et al.,Citation35 using face-to-face delivery experienced only an 8% drop out. Although the attrition rate is very low, further qualitative evaluations found that the weekly site visits for participants in this study were cumbersome and challenging. These studies suggest that the feasibility and acceptability of interventions may be influenced by delivery method. In this regard, telephone-based and web-based approaches hold promise for greater adherence and ultimately reducing loneliness among cancer survivors. Moreover, these studies also provide data supporting the use of technology-based interventions to improve health status and reduce risk for psychosocial depressive symptoms among cancer survivors.Citation49

Strengths of this systematic review include: the large time frame of data extraction, the comprehensiveness of search terms and engines interrogated, and the in-depth review of study design, populations and intervention components as well as the application of meta-analysis. Additionally, the use of narrative methods has been consistently recognized in the investigation of heterogeneity across primary studies and in the understanding of which characteristics of a study may be critical for its effectiveness or the likelihood that the study variability may be due to theoretical variables.Citation28

Despite promising findings identified above, some limitations emerged. This published literature represents a small number of survivors and it is difficult to robustly extrapolate information from a limited amount of studies for comparison. Expanding the search criteria to include non-English research may have increased the number of studies, but would likely have increased study heterogeneity and perhaps reduced generalizability, even further, a limitation of this work. Limitations of the meta-analysis include a small number of studies. Evaluation of the homogeneity of effects between studies should be interpreted cautiously. While a meta-analysis can be conducted with two or more studies,Citation37 more studies are often required for a random-effect models to ensure stable estimates of heterogeneityCitation50and to allow for appropriate tests of sources of heterogeneity.

To move beyond the limitations of the current body of evidence, researchers should consider formative qualitative work with cancer survivors. Such efforts should delineate the unique psychosocial challenges of cancer survivors, including the unique survivor loneliness experience, in order to better intervene on this modifiable risk factor.Citation5 Given, current evidence that loneliness increases over time in cancer patients,Citation51,Citation52 and may occur with other symptoms, interventions may be more efficacious during specific timeframes or when addressing a range of post-treatment symptoms. Future research will need to specifically measure change in loneliness using validated instruments. Strengths of this systematic review include the application of PRISMACitation20 methods, general quality of the studies included, the focus on studies using validated instruments to assess loneliness and the expansive database searched to ascertain results.

Conclusion

This systematic review offers researchers conducting studies addressing loneliness in adult cancer survivors a comprehensive and current assessment of the state of the evidence related to effective interventions. The appraisal of the literature has identified gaps including the limited number of interventions tested, the small sample size of most trials and the need to recruit more heterogeneous (age, sex, socioeconomic, etc.) samples. Advancing knowledge of the strengths and weaknesses of existing loneliness interventions supports the development of future studies particularly those fostering reduced loneliness in adult community-dwelling cancer survivors. With the majority (five of eight) of studies identified in the literature showing feasibility and modest but not robust effectiveness, there is a need to create future interventions with a bottom-up approach. Tailored methodologies informed by cancer survivors, rather than retrofitting existing interventions to cancer survivors, are advisable. Our evaluation of the interventions to date, offers insights into the future approaches, including attention to health behavior theory, and application of technology or telephone-based platforms to reduce the burden of loneliness after a cancer diagnosis.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

Ethical Approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent: This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (60 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the "Silver Tsunami": Prevalence Trajectories and Comorbidity Burden among Older Cancer Survivors in the United States. In: Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prevention. Philadelphia, PA: American Association for Cancer Research; 2016:1029–1036. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0133

- Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016; 66(4):271–289. doi:10.3322/caac.21349

- National Cancer Institute. NCI dictionary of cancer terms [definition of survivor]. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/survivor. Accessed July 27, 2019.

- Sulicka J, Pac A, Puzianowska-Kuźnicka M, et al. Health status of older cancer survivors-results of the PolSenior study. J Cancer Surviv. 2018; 12(3):326–333. doi:10.1007/s11764-017-0672-6

- Rosedale M. Survivor loneliness of women following breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36(2):175–183. doi:10.1188/09.ONF.175-183

- Peplau LA. Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research, and Therapy. Vol. 36. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 1982.

- Yildirim Y, Kocabiyik S. The relationship between social support and loneliness in Turkish patients with cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(5–6):832–836. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03066.x

- Drageset J, Eide GE, Kirkevold M, et al. Emotional loneliness is associated with mortality among mentally intact nursing home residents with and without cancer: a five-year follow-up study. J Clin Nurs. 2013; 22(1–2):106–114. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04209.x

- Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness and pathways to disease. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17(Suppl 1):S98–S105. doi:10.1016/S0889-1591(02)00073-9

- Jaremka LM, Andridge RR, Fagundes CP, et al. Pain, depression, and fatigue: loneliness as a longitudinal risk factor. Health Psychol. 2014;33(9):948–957. doi:10.1037/a0034012

- Jaremka LM, Fagundes CP, Peng J, et al. Loneliness promotes inflammation during acute stress. Psychol Sci. 2013;24(7):1089–1097. doi:10.1177/0956797612464059

- Nausheen B, et al. Relationship between loneliness and proangiogenic cytokines in newly diagnosed tumors of colon and rectum. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(9):913–914.

- Segrin C, Badger TA, Sikorskii A. A dyadic analysis of loneliness and health-related quality of life in Latinas with breast cancer and their informal caregivers. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2019;37(2):213–227. doi:10.1080/07347332.2018.1520778

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Crawford LE, et al. Loneliness and health: potential mechanisms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(3):407–417. doi:10.1097/00006842-200205000-00005

- Masi CM, Chen H-Y, Hawkley LC, et al. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2011;15(3):219–266. doi:10.1177/1088868310377394

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227–237. doi:10.1177/1745691614568352

- Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40(2):218–227. doi:10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

- Theeke LA. Sociodemographic and health-related risks for loneliness and outcome differences by loneliness status in a sample of U.S. older adults. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2010;3(2):113–125. doi:10.3928/19404921-20091103-99

- Simon S. Cancer facts & figures 2019. 2019. https://www.cancer.org/latest-news/facts-and-figures-2019.html. Accessed July 27, 2019.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- D’Agostino NM, Edelstein K. Psychosocial challenges and resource needs of young adult cancer survivors: implications for program development. 2013. https://doi-org.ezproxy4.library.arizona.edu/10.1080/07347332.2013.835018. Accessed July 27, 2019.

- Russell D, Peplau LA, Ferguson ML. Developing a measure of loneliness. J Pers Assess. 1978;42(3):290–294. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4203_11

- De Jong Gierveld J, Van Tilburg T. The De Jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: tested on data from 7 countries in the UN generations and gender surveys. Eur J Ageing 2010;7(2):121–130. doi:10.1007/s10433-010-0144-6

- Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39(3):472–480. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472

- Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. 2019. www.handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed July 7, 2019.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52(6):377–384. doi:10.1136/jech.52.6.377

- Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden AJ, Petticrew, M. Developing guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Commun Health 2005;59 (Suppl 1):A7.

- Nelson CJ, Saracino RM, Roth AJ, et al. Cancer and aging: reflections for elders (CARE): a pilot randomized controlled trial of a psychotherapy intervention for older adults with cancer. Psychooncology 2019;28(1):39–47. doi:10.1002/pon.4907

- Rigney M, Abramson K, Buzaglo J, et al. Evaluation of lung cancer support group participation: preliminary results. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(1):S1116–S1117. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2016.11.1562

- Tabrizi FM, Radfar M, Taei Z. Effects of supportive-expressive discussion groups on loneliness, hope and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: a randomized control trial. Psychooncology 2016;25(9):1057–1063. doi:10.1002/pon.4169

- Dodds S, et al. Feasibility and effects of Cognitively-Based Compassion Training (CBCT) on psychological well-being in breast cancer survivors: a randomized, wait list controlled pilot study. Psychooncology 2015;24:96–97.

- Cleary EH, Stanton AL. Mediators of an Internet-based psychosocial intervention for women with breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2015; 34(5) :477–485. doi:10.1037/hea0000170

- Coleman EA, Tulman L, Samarel N, et al. The effect of telephone social support and education on adaptation to breast cancer during the year following diagnosis. Oncol Nurs Forum 2005;32(4):822–829. doi:10.1188/05.onf.822-829

- Fukui S, Koike M, Ooba A, et al. The effect of a psychosocial group intervention on loneliness and social support for Japanese women with primary breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2003;30(5):823–830. doi:10.1188/03.ONF.823-830

- Samarel N, Tulman L, Fawcett J. Effects of two types of social support and education on adaptation to early-stage breast cancer. Res Nurs Health 2002;25(6):459–470. doi:10.1002/nur.10061

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

- Borenstein M, Higgins JPT, Hedges LV, et al. Basics of meta-analysis: I 2 is not an absolute measure of heterogeneity. Res Syn Meth. 2017;8(1):5–18. doi:10.1002/jrsm.1230

- Pehlivan S, Ovayolu O, Ovayolu N, et al. Relationship between hopelessness, loneliness, and perceived social support from family in Turkish patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer 2012;20(4):733–739. doi:10.1007/s00520-011-1137-5

- Stewart M, Craig D, MacPherson K, et al. Promoting positive affect and diminishing loneliness of widowed seniors through a support intervention. Public Health Nurs. 2001;18(1):54–63. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1446.2001.00054.x

- Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(8):1207–1221. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00040-3

- Erikson J. The Life Cycle Completed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.; 1997.

- Roy C, Andrews HA. The Roy Adaptation Model: The Definitive Statement. Norwalk, CT: Appleton and Lange, 1991.

- Salsman JM, Pustejovsky JE, Schueller SM, et al. Psychosocial interventions for cancer survivors: A meta-analysis of effects on positive affect. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(6):943–955. doi:10.1007/s11764-019-00811-8

- Sheinfeld GS, et al. Meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions to reduce pain in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(5):543–545.

- Salman A, Nguyen C, Lee Y-H, et al. A review of barriers to minorities' participation in cancer clinical trials: implications for future cancer research. J Immigrant Minority Health 2016;18(2):447–453. doi:10.1007/s10903-015-0198-9

- Dickens AP, Richards SH, Greaves CJ, Campbell JL. Interventions targeting social isolation in older people: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2011;11:647.

- Poscia A, Stojanovic J, La Milia DI, et al. Interventions targeting loneliness and social isolation among the older people: An update systematic review. Exp Gerontol. 2018;102:133–144. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2017.11.017

- Lee HY, Kim J, Sharratt M. Technology use and its association with health and depressive symptoms in older cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(2):467–477. doi:10.1007/s11136-017-1734-y

- Cheung M, Vijayakumar R. A guide to conducting a meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev. 2016;26(2):121–128. doi:10.1007/s11065-016-9319-z

- Deckx L, van den Akker M, Buntinx F. Risk factors for loneliness in patients with cancer: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18(5):466–477. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2014.05.002

- Deckx L, van den Akker M, van Driel M, et al. Loneliness in patients with cancer: the first year after cancer diagnosis. Psychooncology. 2015;24(11):1521–1528. doi:10.1002/pon.3818