Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the relationship among sexual functioning, sexual script flexibility, and sexual satisfaction in individuals diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Design

Cross-sectional online survey.

Participants

Sixty-one men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer.

Methods

Online survey of sexual functioning, sexual script flexibility, and sexual satisfaction. Ordinal logistic regression investigated predictors of sexual satisfaction.

Findings

Greater sexual script flexibility was associated with a greater likelihood of being sexually satisfied.

Conclusions

Helping patients explore different ways of being sexual after treatment could help with sexual satisfaction maintenance.

Implications

Patients’ sexual satisfaction may benefit from discussions of issues related to sexuality and ways to work around treatment-related sexual dysfunction with healthcare providers.

Introduction

In Canada, prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in males and the third-leading cause of cancer death.Citation1 With one of the highest five-year net survivals of all cancers, most diagnosed individuals survive and live with the consequences of the disease and its treatments.Citation2–5 Reduced sexual functioning has been found to be one of the most prevalent and distressing side effects of prostate cancer treatment.Citation6–9 However, some men and their partners change their sexual practices to work around sexual dysfunction.Citation6,Citation8,Citation10

The ability to modify one’s sexual practices when experiencing sexual dysfunction may depend on how flexible one’s sexual script is. Sexual scripts include personal rules for essential components of a sexual interactionCitation11 and provide individuals with meaning and direction for sexual behaviors.Citation12 Sexual script flexibility refers to the ability to change one’s sexual script in response to sexual difficulties. Helping patients to modify their rigid and dysfunctional sexual scripts is one approach to treating sexual problems in sex therapy.Citation11

Two models highlight the importance of coping flexibly with sexual changes after cancer treatment. The first, the Flexible Coping Model,Citation13 describes two approaches with which individuals may respond to sexual problems: a “bottom-up” approach involving flexibility in one’s definition of sexual function, and a “top-down” approach involving modifying the importance of sexual function to one’s self-concept. The second model, the Physical Pleasure-Relational Intimacy Model of Sexual Motivation (PRISM modelCitation14) is based on findings that sex for relational intimacy (versus for physical pleasure), sexual flexibility, and sexual communication promote adjustment to treatment-induced sexual dysfunction.

The current study sought to investigate the relationship among sexual functioning, sexual script flexibility, and sexual satisfaction in individuals diagnosed with prostate cancer. Consistent with both the Flexible Coping and PRISM models, we hypothesized that individuals with better sexual functioning would report greater sexual satisfaction and that individuals who were more sexually flexible would report greater sexual satisfaction.

Method

Participants

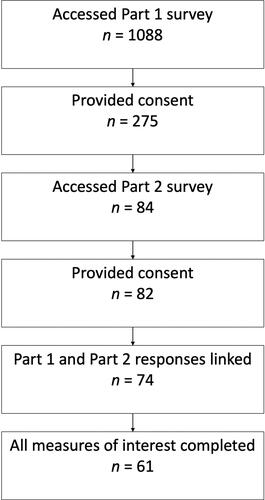

From January 2018 to October 2019, participants were recruited online via social media, paid advertisements, and emails to prostate cancer support groups, LGBTQ + organizations, and community health centers. Eligible participants were previously diagnosed with localized prostate cancer. The online survey was divided into two parts due to length. Participants created an anonymous ID number to link their responses between the two parts. A final sample of 61 participants who completed all measures of interest for the present analysis (outlined below) is described in this article (see ).

Measures

Demographics and cancer trajectory

Demographic and cancer trajectory questions were included in Part 1 of the survey. Demographic questions included those related to participants’ age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, ethnicity, and relationship status. Participants were also asked about their date of diagnosis and Gleason score. Those who underwent active treatment were asked for their treatment modality and wait time. Those who did not were asked to select between watchful waiting and active surveillance.

Sexual functioning

Participants completed the Clinical Practice form of the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-CPCitation15), a measure of health-related quality of life, in Part 1 of the survey. The three-item Sexual domain was used as a measure of sexual functioning. A domain score was calculated by summing the three item scores. Higher scores indicate worse sexual functioning. In the initial validation study, Cronbach’s α coefficient for the Sexual domain was .80 (present sample: Cronbach’s α =.81).

Sexual satisfaction

Participants completed the International Index of Erectile Function for men who have sex with men (IIEF-MSMCitation16) in Part 1 of the survey. The IIEF-MSM was modified for the present study to be inclusive of men with sexual partners of any gender. The single-item Overall Satisfaction domain was used to measure sexual satisfaction. Participants rated how satisfied they have been with their overall sex life over the past four weeks from zero (Very dissatisfied) to four (Very satisfied).

Sexual script flexibility

Participants completed the SexFlex Scale in Part 2 of the survey (SFSCitation17) to assess sexual script flexibility. The scale consists of 6 items that complete the phrase “When confronted with my sexual difficulty.” Participants rated each item from one (Seldom or never) to four (Almost always). Item scores were summed to create a total score. Higher scores indicate a greater frequency of flexible responses. The SFS demonstrates high internal consistency and good convergent and discriminant validity.Citation17 In the present study, Cronbach’s α = .91.

Procedure

Participants accessed the survey via the anonymous link presented in recruitment materials and provided their informed consent. Part 1 took approximately 60 min to complete. At the end, participants were presented with a debriefing letter, and were given the option of providing their email address to enter a prize draw and to proceed to Part 2 (30 min). This study received ethical clearance from the Queen’s University General Research Ethics Board (GPSYC-807-17).

Results

Sample characteristics

The mean age of participants was 66.11 years old (SD = 8.07 years). All participants identified as men. On average, participants had been diagnosed with prostate cancer 4.16 years ago (SD = 2.82 years; range: 3 months to 22 years; ).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics.

Sexual functioning, sexual script flexibility, and sexual satisfaction

See and for summary statistics and correlations among the measures of interest. We conducted an ordinal logistic regression with a cumulative logit model using PROC LOGISTIC in SAS Studio for Academics to determine if the predictive relationship between sexual functioning (EPIC-CP: Sexual domain) and sexual satisfaction (IIEF-MSM: Overall Satisfaction) was moderated by sexual script flexibility (SFS). We mean-centered the two continuous predictors to create more meaningful zero points for interpretation.

Table 2. Participants’ ratings of sexual functioning and sexual script flexibility by level of sexual satisfaction.

Table 3. Correlations among measures of interest.

The interaction between sexual functioning and sexual script flexibility was not significant, b = 0.023, SE = 0.015, Wald χ2 = 2.18, p = .14. Thus, we ran the more parsimonious cumulative logit model without the interaction term; the continuous predictors were uncentered. The score test for the proportional odds assumption was violated, χ2(6) = 12.66, p = .049. We proceeded to run a partial proportional odds model, using PROC LOGISTIC’s SELECTION option to determine which effects exhibited nonproportional odds. The final model included all equal slope parameters, as well as unequal slope parameters for sexual functioning.

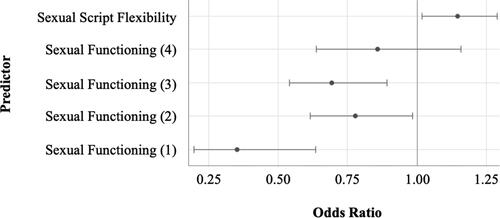

We examined the odds ratio for sexual script flexibility, as well as the odds ratios for sexual functioning at each level of sexual satisfaction. The odds ratio for sexual script flexibility was 1.15 (95% Wald CI [1.02, 1.30]); an increase in sexual script flexibility was associated with an increase in the odds of reporting greater sexual satisfaction. With regards to sexual functioning, for the response function comparing individuals who reported being “Very satisfied” with their overall sex life versus all other participants, the confidence interval for the odds ratio contained one (95% Wald CI [0.64, 1.16]), indicating that participants in either group were equally likely to have greater sexual satisfaction. The confidence intervals for the remaining odds ratios did not contain one; a decrease in sexual functioning was associated with a decrease in the odds of reporting greater sexual satisfaction ().

Discussion

Previous qualitative research has reported that some individuals treated for prostate cancer adopt new sexual practices post-treatment to maintain a satisfying sex life (Boehmer and Babayan 2004).Citation8,Citation10,Citation14 To our knowledge, this study is the first to quantitatively measure sexual script flexibility in this population and to investigate how it relates to sexual functioning and satisfaction. As hypothesized, greater sexual script flexibility was associated with greater likelihood of being sexually satisfied, above and beyond one’s level of sexual functioning.

In previous research, experiencing a greater number of sexual issues has been associated with lower sexual satisfaction.Citation18 It follows that those who can find ways to be sexual despite these issues would be more satisfied with their overall sex life. Qualitative research on prostate cancer patients and their partners has found that sexual flexibility separated sexually active couples from those who had ceased sexual activity since treatment.Citation14 In an online survey that asked individuals diagnosed with prostate cancer about changes they had made to their sexual practices since their diagnosis, many discussed reframing their sexual practices, such as by engaging in less frequent penetrative activities and more frequent partnered oral and manual stimulation, or attempting anal penetration and prostate stimulation for the first time.Citation10 Having a partner who was willing to try different activities was important for reframing their sexual practices.

The results of the present study have implications for patient healthcare. Discussions of issues related to sexuality and ways to work around potential treatment-induced sexual dysfunction could benefit patients’ sexual satisfaction. As one participant in Fergus et al.’sCitation8 study stated, “If you’ve got 10 fingers and a tongue, sex ain’t dead.” The sentiment behind this humorous statement is reflected in both the PRISM and Flexible Coping models.Citation13,Citation14 Reese et al.Citation13 discuss clinical implications of the Flexible Coping Model for individuals with cancer. By focusing specifically on the concept of flexibility, the model is a targeted form of sex therapy that can be used in cancer treatment settings with limited counseling time. The authors also suggest that patient informational materials incorporate this model, providing information on the concept of flexibility and highlighting ways in which patients can be flexible in their approach to sex. The authors stress the importance of assessing cancer patients’ sexual concerns as well as their flexibility. The results of the present study suggest that specific assessment of patients’ sexual script flexibility may be particularly helpful.

Limitations and directions for future research

It will be important to replicate these results in larger samples. Time since diagnosis ranged greatly; future research might take a longitudinal approach in investigating how the relationship among sexual functioning, sexual satisfaction, and sexual script flexibility changes over time. Nearly a quarter of participants in our sample identified as gay or bisexual; research that compares sexual script flexibility in heterosexual and gay/bisexual men diagnosed with prostate cancer may be important in developing relevant models and counseling approaches. Further, expanding this research to diverse patient populations experiencing sexual dysfunction as a result of their disease and/or treatment, regardless of their specific cancer diagnosis, is also warranted. Finally, research on the flexible coping model developed by Reese et al.Citation13 should investigate the impact of this targeted form of sex therapy on patients’ sexual script flexibility and their overall sexual satisfaction.

Conclusions

Prostate cancer is common. The high survivorship and many treatment options mean that most diagnosed individuals are living with the disease and treatment side effects. Sexual script flexibility, in addition to sexual functioning, are significantly associated with sexual satisfaction in men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer. Helping patients explore different ways of being sexual after treatment could help them to maintain their sexual satisfaction.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial conflicts of interest to report.

Funding

This work was supported by a Prostate Cancer Canada Movember Discovery Grant (Grant Number: D2017-1850).

References

- Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2017. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2017.

- Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2018. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society: Toronto, ON; 2018.

- Goldstone SE. The ups and downs of gay sex after prostate cancer treatment. J Gay Lesbian Psychother. 2005;9(1-2):43–55. doi:10.1300/J236v09n01_04

- Hurwitz M. Combined external beam radiotherapy and brachytherapy for the management of prostate cancer. Oncol. Hematol. Rev. 2006;202(5):973–978. doi:10.17925/OHR.2006.00.00.29

- Singer EA, Golijanin DJ, Miyamoto H, Messing EM. Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9(2):211–228. doi:10.1517/14656566.9.2.211

- Boehmer U, Babayan RK. Facing erectile dysfunction due to prostate cancer treatment: Perspectives of men and their partners. Cancer Invest. 2004;22(6):840–848.

- Bokhour BG, Clark JA, Inui TS, Silliman RA, Talcott JA. Sexuality after treatment for early prostate cancer. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(10):649–655.

- Fergus KD, Gray RE, Fitch MI. Sexual dysfunction and the preservation of manhood: Experiences of men with prostate cancer. J Health Psychol. 2002;7(3):303–316.

- Helgason AR, Adolfsson J, Dickman P, Fredrikson M, Arver S, Steineck G. Waning sexual function: The most important disease-specific distress for patients with prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 1996;73(11):1417–1421.

- Wassersug RJ, Westle A, Dowsett GW. Men’s sexual and relational adaptations to erectile dysfunction after prostate cancer treatment. Int J Sexual Health. 2017;29(1):69–79. doi:10.1080/19317611.2016.1204403

- Wiederman MW. The state of theory in sex therapy. J Sex Res. 1998;35(1):88–99. doi:10.1080/00224499809551919

- Wiederman MW. The gendered nature of sexual scripts. Family J. 2005;13(4):496–502. doi:10.1177/1066480705278729

- Reese JB, Keefe FJ, Somers TJ, Abernethy AP. Coping with sexual concerns after cancer: The use of flexible coping. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(7):785–800.

- Beck AM, Robinson JW, Carlson LE. Sexual values as the key to maintaining satisfying sex after prostate cancer treatment: The Physical Pleasure-Relational Intimacy Model of Sexual Motivation. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42(8):1637–1647. doi:10.1007/s10508-013-0168-z

- Chang P, Szymanski KM, Dunn RL, et al. Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite for Clinical Practice: Development and validation of a practical health related quality of life instrument for use in the routine clinical care of patients with prostate cancer. J Urol. 2011;186(3):865–872. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2011.04.085

- Coyne K, Mandalia S, McCullough S, et al. The International Index of Erectile Function: Development of an adapted tool for use in HIV-positive men who have sex with men. J Sex Med. 2010;7(2 Pt 1):769–774.

- Gauvin S, Pukall CF. The SexFlex Scale: A measure of sexual script flexibility when approaching sexual problems in a relationship. J Sex Marital Therapy. 2018;44(4):382–397. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2017.1405304

- Byers ES, MacNeil S. The relationships between sexual problems, communication, and sexual satisfaction. Can. J. Human Sex. 1997;6(4):277–284.