Abstract

Purpose

To explore psychosexual experiences of women following radical radiotherapy for gynaecological cancer.

Methods

Seven women who had completed radical radiotherapy for gynaecological cancer were interviewed. Interviews were semi-structured, and data were analyzed using an interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) approach.

Results

Five superordinate themes were constructed: (1) No desire for sex since completing treatment; (2) Fear; (3) Unmet information and support needs; (4) Partner support and needs; and (5) Communication. Fear of adverse consequences following sex inhibited return to sexual activity after treatment. Misconceptions and lack of knowledge were evident. Communicating sexual issues was a difficulty that transcended personal relationships, also evident in professional medical relationships.

Conclusion

Simple measures, beginning with facilitating understanding and acceptance of psychosexual experiences, can help those experiencing psychosexual problems following radical radiotherapy. Encouraging discussion, providing options and practical knowledge, and clarifying misconceptions about risks from sex after cancer could improve outcomes for gynaecological cancer patients.

Introduction

Gynaecological Cancer (GC) refers to cancer involving the female reproductive tract and includes cancers of the cervix, endometrium, vulva, and vagina.Citation1 Due to an expanding and aging population, the number of GC cases is increasing.Citation2 Prevalence of sexual side-effects following therapy varies depending on cancer and therapy type but may be as high as 100% after treatment of genital cancers.Citation3–6 Common side-effects of radiotherapy specifically include vaginal dryness, shortness, and stenosis, dyspareunia, lack of sexual desire, and orgasmic issues.Citation7,Citation8

The term “psychosexual” describes the psychological and emotional attitudes surrounding sexual thought and activity.Citation9 Physical side-effects of treatment or personal experiences with symptoms of disease (e.g., menorrhagia) can have long-lasting psychosexual effects. Psychological distress imposed by fear (e.g., fear of recurrence, pain, and the unknown) and other stressors can affect libido and cause disinterest in sexual intimacy.Citation10–12 For sexual activity to be successful and fulfilling, the body must be functioning without psychological or emotional barriers affecting libido or limiting sexual enjoyment.Citation9

Many patients find it difficult to seek help for psychosexual problems due to embarrassment, shame, fear of being judged, fear of bearing bad news, or worry about not having the right words.Citation13 When sexual challenges are not expressed they may contribute to increased fear and anxiety, which tend to increase physical challenges such as discomfort and painCitation10,Citation11,Citation14 due to the close relationship between body and mind.Citation15 Despite the frequency of sexual dysfunction and distress amongst GC patients, it is not routinely addressed by medical staff.Citation8,Citation16–18 Many patients adjust to cancer and its treatment effects, but others struggle with emotional adjustment in the survivorship period,Citation12 which disrupts quality of life and return to usual activities.Citation19,Citation20

Existing research offering rich detailed accounts of psychosexual experiences of GC survivors is limited, highlighting an important gap in the literature. This study, therefore, aimed to qualitatively explore psychosexual experiences of women following radical radiotherapy for GC.

Methods

Research method

An interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) approach, rooted in critical realism and the social cognition paradigm, was employed to allow the exploration and generation of rich, detailed descriptions of participants’ lived psychosexual experiences following radiotherapy. IPA aims to provide insight into how an individual makes sense of a particular phenomenon through detailed exploration of the way they make sense of their world, from both a social and personal perspective.

Recruitment process

Patients who received radical radiotherapy as part of GC treatment between 6 and 24 months previously were considered for inclusion in the study. This timeframe was deemed appropriate to assess radiation late effects.Citation21 Potential participants had to be compos mentis (i.e. of sound mind and with the ability to give informed consent), fluent in English, and ≥18 years of age.

A database of patients who received radiotherapy for GCs between 2016 and 2018 (approximately 100 patients) was utilized to identify potential participants. Permission for access was granted by the Radiotherapy Services Manager and Radiation Oncologist at University Hospital Galway and ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Irish College of Humanities & Applied Sciences (ICHAS) and University Hospital Galway. A purposive sampling method was used to recruit participants. Eight patients were selected and contacted via phone to take part. Of these, one declined. Having never had sexual intercourse and with no interest in the subject this participant did not feel this study relevant to her and declined to participate. Informed consent was obtained, and interviews were arranged to coincide with a radiotherapy follow-up appointment for participant convenience.

Data collection

Participants were invited to participate in an interview in the hospital at which they received their treatment. Individual interviews were conducted between March and April 2019 using a semi-structured topic guide. Demographic information (e.g., age, time since completion of treatment) was obtained first, followed by an in-depth discussion of psychosexual experiences. The researcher explained the nature of phenomenological research and encouraged participants not to feel uncomfortable during periods of silence but to allow for thoughts to process during the interview. In keeping with a phenomenological approach where the role of the researcher is that of distant observer, the interview guide asked participants to talk about their thoughts and feelings toward sex since completing treatment. At the end of each interview, the researcher spent additional time with the participant, checking their impressions were accurate and exploring thoughts and feelings in more detail. On average, interviews lasted approximately 50 minutes. Interviews were audio-recorded via Dictaphone and transcribed verbatim. Pseudonyms were given to each participant to protect anonymity. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was adhered to at all stages of the research. Data files with pseudonyms for the participants were stored on an encrypted USB in a locked file cabinet in the radiotherapy service manager’s office, to be retained for three years.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using IPA in accordance with the step-by-step guidelines outlined by Smith & Osborn.Citation22 First, transcripts were read and reread to facilitate familiarization through immersion in the data.Citation22 Voice recordings were also listened to repeatedly to get an overall impression of the entire experience and aid familiarization. Analysis involved continuous review of the transcripts to ensure themes were grounded within the text. Transcripts were analyzed by the lead researcher, who developed initial notes through free association and exploration of semantic content. Emergent themes were developed from these notes. Each transcript was analyzed separately, acknowledging that repeated and new themes from previously analyzed transcripts could be identified. Patterns of shared higher-order qualities across transcripts were identified, from which superordinate themes were constructed. Themes were chosen based on their importance in the process of participants’ change rather than their frequency and themes poor in evidence were abandoned.Citation22

Rigor and trustworthiness

Several steps were taken to ensure rigor and trustworthiness of the data. Research quality checks guided by an established frameworkCitation23,Citation24 were utilized to ensure dependability, transparency, credibility, and generalisability/transferability and foster trustworthiness while conducting this qualitative study.

To ensure the data were reflective of participants’ experiences and to enhance the credibility of the conclusions drawn by the authors, the lead researcher spent an additional 20–30 minutes with each participant to paraphrase and discuss their impression of what was discussed. The authors were confident that the data and the researcher’s interpretations were accurate and representative following agreement by participants during these discussions. Finally, to ensure dependability, or stability of the data over time, an audit trail was established. This involved tracking and recording all decisions which could have influenced the study so that an outside individual could examine the data.Citation25

Results

Seven participants were interviewed. Their average age was 48 years (range 36–66 years). On average, 15 months had passed since completion of radiotherapy (range 10–22 months). Participant demographics are shown in . Participants are referred to as P1, P2, etc. within the text.

Table 1. Participant demographics.

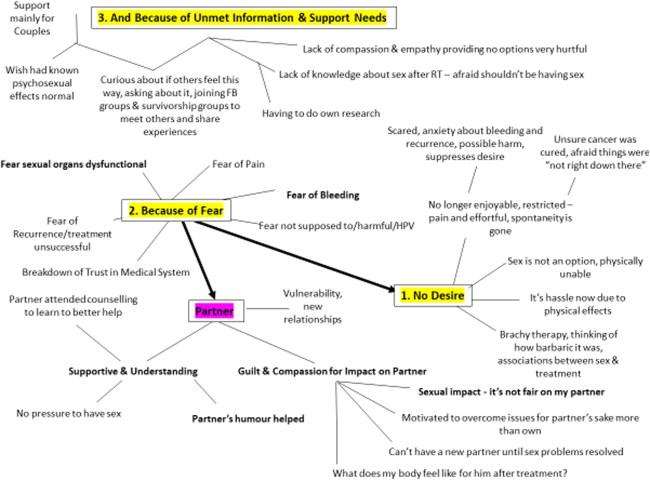

Five superordinate themes were developed: (1) No desire for sex since completing radiotherapy; (2) Fear; (3) Unmet information and support needs; (4) Partner support and needs; and (5) Communication. Each theme has related subordinate themes, which are discussed in turn in the following section.

No desire for sex since completing radiotherapy

Desire was suppressed by experiences of pain, fear, and anxiety.

(i) Sex is painful or difficult

Lack of desire was largely attributed to the effort, pain, and discomfort involved in the act of sex itself. A sense of dread for the ordeal of sex was expressed:

I did get out of bed quickly for fear that he had an erection. I just kind of didn’t want the whole big deal about it, getting the lubrication and trying to…I didn’t have the patience really to go through the whole thing. (P4)

We did attempt sex within a few months of me finishing treatment…it was very uncomfortable. Very dry. I felt very tight. I felt he was too big for me to get in. It only lasted a minute or two. I had to tell him, stop. (P4)

Participants who expressed no sexual desire attributed this to anxiety, which was largely driven by a fear of the unknown. P6 expressed fear that she was “not right down there,” unsure about whether she was supposed to be having sex since radiotherapy, afraid it could be harmful:

I didn’t want anything to hurt me. Or do damage to me. […] I was just thinking, should I be doing this now? Should we be doing this? (P6)

I’m just afraid…I just have this big fear what is going to happen if I do actually end up having sex? (P1)

Fear

Fear was discussed in relation to the feared harm of sex.

(i) Fear sex could cause trauma to the treatment area

Five women spoke of being afraid to have sex after radiotherapy in case it could be harmful or cause vaginal bleeding. After radiotherapy, the thought of seeing blood again incited a fear that the cancer was back, or propelled the participant back to the trauma experienced prior to diagnosis.

It’s scary, it really is…There’s still some bleeding after, and that just puts the fear of God into me. So, I definitely was avoiding sex, because as soon as I see any bleeding from there, it just propels me right back to when I was diagnosed. (P7)

P4 expressed fear that having sex could cause trauma to the treatment site, which caused her to feel “uptight” and “nervous.”

I was afraid of being hurt, afraid of being damaged inside…And I was very anxious, nervous… (P4)

(ii) Cancer-related fears

Five women talked about other cancer-related fears that caused them to side-line sex. P3 and P7 referred to persisting fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) several times throughout their interviews:

I know I’m fine, but it’s just… at the back of my head, the fear. Now is it a fear that it is going to come back again? Yes. (P3)

…got the all-clear in January, and then around April, I just hit the wall kind of with anxiety I started to get panic attacks…the idea of anything kind of sexual was off the table. (P7)

We used a condom, whereas we never used a condom before, for my own mental health and that I associate my cancer with a man’s penis now, and whatever is on that virus or whatever, so I still see the penis now as something harmful, something dangerous, something that could do more harm to me. (P4)

I fear that…that maybe the fact that having sex will kind of bring it [the cancer] back again. (P3)

Unmet information & support needs

This theme captures the lack of information, support, and unique needs of this cohort.

(i) Being single versus coupled

P5 was the only participant who was not in a relationship. She noted a unique lack of support for single women. She recounted her experience with a sexual psychotherapist:

She’s like, you go back to basics and touching, build up that whole relationship again, from the outside. And I was like yeah, but what happens when you don’t have that other person to be there with you, that you’re starting from scratch? (P5)

A lack of knowledge and support was evident across the interviews. One participant described the way a doctor informed her that she “may never have sex again,” as devastating. His comment about alternative ways to be intimate left her confused and upset:

He [doctor] said, ‘well there’s other ways and means,’ and I went out to the car and I was crying and I was on to my sister and I said, ‘I can’t have anal sex, my rectum is fecked as well from radiotherapy like.’ I said, ‘I don’t want anal sex anyway!’ She was laughing at me, ‘I don’t think that’s what he was on about.’ I said, ‘well can you explain to me so what he was on about?!’ So, I think that at that point, that’s what caused the most damage. (P5)

There wasn’t any could this or this could or could anything? No, it was just this is it, done. A whole chapter in your life completely done in a matter of five seconds. (P5)

Is it normal for you know, for me, for women to feel like this or am I just, totally crazy altogether, d’you know what I mean? (P1)

Partner support and needs

Most participants felt that their partner was very understanding of their position after radiotherapy; however, some expressed worries in relation to the effect of their experiences on their partners.

(i) Understanding/supportive partner

Six women felt that their partners were very supportive in helping them cope with trying to overcome psychosexual challenges after treatment. P7 felt understood by her husband, who attended counseling himself to understand how to better support his wife:

He totally understood what I was going through. I think he just felt like he wanted to help in some way, but he couldn’t, so he actually went to one or two counselling sessions. He said he feels fine with it personally, but he went to try and help how to understand how to help me better. […] he’s been brilliant… I think it’s almost made us closer. (P7)

Five participants expressed worries about their partners or at the idea of a future partner, worried about what post-treatment changes would feel like during sex and the impact of more infrequent sex on the relationship. The only single participant worried about future partners.

P2, who had surgery and brachytherapy worried her body would feel different to her partner during sex, more conscious of her partner’s pleasure than the pain of sex:

I was more sort of worried about what it felt like for him. If I had changed, you know? (P2)

I felt it was unfair on him. I worried he might be a bit resentful…I felt a bit bad. Other men are having sex. Now, my poor husband isn’t having regular sex. (P4)

Communication

Three participants expressed a desire but an inability to communicate psychosexual issues with partners.

(i) Desire but inability to communicate psychosexual issues with partner

Though partners were supportive, the couple did not discuss their sexual abstinence and psychosexual issues in three cases. P1 stated that her partner was “a very understanding man,” but that they did not talk about “the sex part” of their relationship.

P6 acknowledged that communicating sexual issues with a new partner might be particularly challenging:

It would be hard to let them know [reasons for sexual reluctance].

Despite the impact of psychosexual experiences, only P4 and P5 spoke about addressing their issues with the medical team, highlighting that talking about sex may be a difficult for patients but also for healthcare professionals (HCPs), who struggled to discuss sexual challenges beyond a medical perspective.

P2 acknowledged that some patients may benefit from having a HCP prompt a discussion about psychosexual impacts:

I think if somebody maybe was having problems but were shy in coming forward and talking about them, maybe a little prompt, you know, or a little sort of nudge would help. (P2)

I’ll just kind of stress the point that I am using my dilators, you know, to stop the conversation I suppose more so than get into it. (P1).

They’d ask if you’re back to sexual activity, was I using the dilators or was I doing it the old-fashioned way, and I was saying not as much as I should because I’m spotting and it gives me huge fear. And they said, okay, we understand the spotting is normal, and that’s if you’re hitting scar tissue or site, whatever, it should ease. (P7)

Discussion

This study aimed to explore psychosexual experiences of women following radiotherapy for a GC. Most participants expressed feelings of fear, both that sex could be physically harmful and in terms of recurrence risk, creating a psychosexual barrier. Physical effects of radiotherapy contributed to a lack of sexual desire, further suppressed by anxiety, driven by a fear of the unknown with respect to sex after treatment. A lack of awareness surrounding “psychosexual issues,” an unfamiliar term, was evident. Those who were unaware of the prevalence of psychosexual issues following radiotherapy were relieved to learn their experiences were “normal.” Misconceptions and lack of knowledge were evident, with some women afraid that having sex after treatment could cause cancer recurrence or physical harm. Partners were commended for their understanding and support during the recovery process, but participants worried about partners’ needs and feelings in the absence of discussion. Communicating issues of a sexual nature was an issue that transcended personal relationships, evident in professional medical relationships also.

The current findings demonstrate that following cancer treatment, physical and psychological challenges relating to sex often go hand-in-hand. It is possible that post-menopausal status contributed to sexual disinterest in this study population;Citation25 however, reasons given by participants for lack of desire were directly attributed by them to their cancer and treatment. Sex was no longer spontaneous due to physical side-effects such as vaginal dryness and stenosis. Concerns that sex could lead to recurrence, as well as a fear of pain and other cancer-related fears, affected libido. This is consistent with the literature, whereby psychological distress was found to be negatively associated with libidoCitation12 and women tended to avoid sexual contact due to sexual pain and discomfort, or anxiety for pain.Citation11,Citation12,Citation26,Citation27

A physical and psychological approach is required in the management of sexual issues as both body and mind are involved during sexual engagement.Citation28 Having options to help overcome barriers to sex appeared meaningful for participants. Identifying possible solutions to potentially lifelong physical and psychological sexual problems was motivational and provided hope. This suggests that simple measures, such as routinely asking about sexual activity and discussing physical and psychological factors in consultations, could be impactful.Citation28,Citation29

Fear (e.g., FCR due to sex) contributed to psychosexual distress of participants. Little is known about the specific nature and cognitive mechanisms of FCR,Citation30 though some research suggests higher levels of FCR may occur among females and people diagnosed at a younger age.Citation31–33 The demographic profile of participants in this study may partly explain the dominance of this theme.

Five women feared that sex would be harmful and were particularly distressed by the idea of bleeding following intercourse, especially participants who had experienced menorrhagia before diagnosis. Following a trauma like a cancer diagnosis, patients can develop symptoms similar to those of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).Citation34,Citation35 Some studies reference bleeding as a distressing side effect of treatment due to the commonality of bleeding in recurrenceCitation36,Citation37 but additional research exploring fear of bleeding from the perspective of trauma is needed.

Some participants expressed fear that sex could cause cancer recurrence. Rositch et al.Citation38 demonstrated that most incidents of HPV infection was attributable to past, not current, sexual behavior at older ages, supporting a natural history model of viral latency and reactivation. Providing more information about the nature of HPV, and other key medical information to patients could reduce fears surrounding its role in recurrence risk.

The views of the only single participant in this study (age 36 years) were consistent with the literature. McCallum et al.Citation39 stated that younger single women were more likely to experience a variety of sexual issues due to early treatment-induced menopause, infertility, and a higher frequency of new and developing relationships with which they may require more emotional support. In P5’s experience, the focus of psychosexual support was limited to people in relationships.

A desire but an inability to communicate sexual issues that transcended relationships was evident, leading to suppressed feelings of loss, guilt, and sadness. Cohee et al.Citation40 found that FCR may be maintained in breast cancer survivors if they are unable to talk about the cancer experience with their partners. A good relationship with their partner helps women with the coping process.Citation25,Citation29 Partners may unknowingly contribute to psychosexual barriers by declining invitations to talk about what is going on for the couple. Only two of the women chose to bring up psychosexual issues at their medical follow-up appointments. It was also suggested that HCPs struggled to respond beyond a medicalised fashion, suggesting that they too feel uncomfortable with discussion of sexual matters.

Practice implications

The current study identifies several potential measures to improve psychosexual care following radiotherapy for GC. Existing supports available to participants in this study included clinician referral to a psychosexual therapist. Due to demand and limited resources, wait times for an appointment is typically one year. Other resources available to patients include free general counseling provided externally by cancer charities, or private psychosexual therapy that must be sourced and arranged by the patient themselves. Outsourcing psychosexual care may represent a missed opportunity for HCPs to intervene early and may erroneously send the message that psychosexual care is not a central element of treatment and recovery.

This study identified a need for sexual health communication training for HCPs treating GC patients so that they can comfortably initiate conversations about psychosexual experiences in an informed manner. Radiation therapists who engage with patients during and after treatment, and typically provide information and support, may be best placed to support patients’ psychosexual care needs. Clinicians could be trained to offer a certain level of information and support, and to refer patients for additional counseling and psychosexual services as required, an approach currently being trialed in the Netherlands.Citation41 Online, evidence‐based, interactive communication skills programmes may also be appropriate, such as those developed in AustraliaCitation42 with the aim to improve the ability of HCPs to provide effective psychosexual care to women affected by GC.

The current findings also highlight the need for further interventions to address emotional aspects of treatment and its potential impact on intimate relationships for this cohort. Low-intensity interventions, for example information booklets created to address psychosexual impact,Citation7 can validate patient experiences and help to overcome psychosexual difficulties. Further research to develop and test patient-focused interventions to promote psychosexual health is now warranted.

Study limitations

Although treatment for GC is similar for its subgroups, the extent of treatment and modality vary depending on histology, staging, and patient preference. In this study, treatment ranged from brachytherapy alone to full pelvic external beam radiotherapy with brachytherapy +/- chemotherapy. A correlation between more extensive treatment and increased risk of side-effects, and therefore psychosexual effects, is probable and acknowledged within the literature.Citation7,Citation40 Studies focused on each subgroup may provide important insight into treatment- or diagnosis-specific experiences. Similarly, all but one participant were in long-term relationships and all had similar sociodemographic backgrounds, which means important perspectives were underrepresented. Limitations notwithstanding, this article provides important insight into psychosexual experiences for survivors of GC through its robust approach to qualitative investigation.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that relatively simple measures, such as normalizing psychosexual therapies and providing reliable information, may enhance psychosexual care. Knowing their experiences are normal can provide relief to distressed patients. Delivery of compassionate care that provides options, choice, and practical knowledge, and clarifies misconceptions about sex after cancer could greatly improve quality of care for this cohort. Radiation therapists, particularly HCPs in advanced practice roles with a focus on gynecology patients, would be well placed in providing psychosexual information and support to GC patients. To ensure a broad awareness of psychosexual experiences and a wide range of support for this patient cohort, the authors recommend training and education for all HCPs (e.g., social workers, nurses, and oncologists) involved in the care path of this patient cohort.

Disclosure statement

The authors certify that they have no conflict of interest to declare relevant to the content of this article.

Funding

The authors reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

References

- Boggett A, Graham L, Wersch AV. Sexuality in women recovering from gynaecological cancer. Int J Gynecol Obstet Res. 2015;3(1):1–6. doi:10.14205/2309-4400.2015.03.01.1

- White MC, Holman DM, Boehm JE, Peipins LA, Grossman M, Henley SJ. Age and cancer risk: a potentially modifiable relationship. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(3 Suppl 1):S7–S15.

- Schover LR, Kaaij MVD, Dorst EV, Creutzberg C, Huyghe E, Kiserud CE. Sexual dysfunction and infertility as late effects of cancer treatment. EJC Suppl. 2014;12(1):41–53. doi:10.1016/j.ejcsup.2014.03.004

- Kennedy V, Abramsohn E, Makelarski J, et al. Can you ask? We just did! Assessing sexual function and concerns in patients presenting for initial gynecologic oncology consultation. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(1):119–124. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.01.451

- Ben Charif A, Bouhnik A, Courbiere B, et al. Patient discussion about sexual health with health care providers after cancer—a national survey. J Sex Med. 2016;13(11):1686–1694. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.09.005

- Mishra N, Singh N, Sachdeva M, Ghatage P. Sexual dysfunction in cervical cancer survivors: a scoping review. Womens Health Rep (New Rochelle). 2021;2(1):594–607. doi:10.1089/whr.2021.0035

- Lubotzky FP, Butow P, Hunt C, et al. A psychosexual rehabilitation booklet increases vaginal dilator adherence and knowledge in women undergoing pelvic radiation therapy for gynaecological or anorectal cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2019;31(2):124–131. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2018.11.035

- Iżycki D, Woźniak K, Iżycka N. Consequences of gynecological cancer in patients and their partners from the sexual and psychological perspective. Prz Menopauzalny. 2016;15(2):112–116. doi:10.5114/pm.2016.61194

- Brough P, Denman M. 2019. Introduction to Psychosexual Medicine. Milton: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- Yang Y, Cameron J, Humphris G. The relationship between cancer patient’s fear of recurrence and radiotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2017;26(6):738–746. doi:10.1002/pon.4224

- Shay LA, Carpentier MY, Vernon SW. Prevalence and correlates of fear of recurrence among adolescent and young adult versus older adult post-treatment cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(11):4689–4696. doi:10.1007/s00520-016-3317-9.

- Yi J, Syrjala K. Anxiety and depression in cancer survivors. Med Clin North Am. 2017;101(6):1099–1113. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2017.06.005

- Goldfarb S, Mulhall J, Nelson C, et al. Sexual and reproductive health in cancer survivors. Semin Oncol. 2013;40(6):726–744. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.09.002

- Bukovic D, Silovski H, Silovski T, et al. Sexual functioning and body image of patients treated for ovarian cancer. Sex Disabil. 2008;26(2):63–73. doi:10.1007/s11195-008-9074-z

- Krouwel EM, Albers LF, Nicolai MP, et al. Discussing sexual health in the medical oncologist’s practice: exploring current practice and challenges. J Canc Educ. 2020;35(6):1072–1088. doi:10.1007/s13187-019-01559-6

- Juraskova I. Quality of LIFE/Quality of SEX: Psycho-sexual adjustment following gynaecological cancer. Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller; 2009.

- Rizzuto I, Oehler MK, Lalondrelle S. Sexual and psychosexual consequences of treatment for gynaecological cancers. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2021;33(9):602–607. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2021.07.003

- Berg CJ, Stratton E, Esiashvili N, Mertens A. Young adult cancer survivors’ experience with cancer treatment and follow-up care and perceptions of barriers to engaging in recommended care. J Cancer Educ. 2016;31(3):430–442. doi:10.1007/s13187-015-0853-9

- Reis N, Beji N, Coskun A. Quality of life and sexual functioning in gynecological cancer patients: results from quantitative and qualitative data. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14(2):137–146.

- National Cancer Strategy 2017-2026, Ireland. published 2017.

- Lacey A, Luff D. Qualitative Research Analysis. The NIHR RDS for the East Midlands/Yorkshire & the Humber, 2007.

- Smith J, Osborn M. Interpretive phenomenological analysis. In Smith JA, ed. Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods. London: Sage; 2007:51–80.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Matthews B, Ross L. 2010. Research Methods. London: Pearson Longman.

- Dempsey PA, Dempsey AD. Using Nursing Research; Process, Critical Evaluation, and Utilization. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2000:262.

- Carter J, Huang H, Chase DM, et al. Sexual function of patients with endometrial cancer enrolled in the Gynecologic Oncology Group LAP2 Study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22:1624–1633.

- Vermeer WM, Bakker RM, Kenter GG, et al. Cervical cancer survivors’ and partners’ experiences with sexual dysfunction and psychosexual support. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(4):1679–1687. doi:10.1007/s00520-015-2925-0

- Domoney C. Psychosexual problems. Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Med. 2014;24(2):56–61. doi:10.1016/j.ogrm.2013.12.004

- Lebel S, Ozakinci G, Humphris G, et al. From normal response to clinical problem: definition and clinical features of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(8):3265–3268. doi:10.1007/s00520-016-3272-5.

- de Souza C, Santos AVDSL, Rodrigues ECG, Dos Santos MA. Experience of sexuality in women with gynecological cancer: meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Cancer Invest. 2021;39(8):607–620. doi:10.1080/07357907.2021.1912079

- Petzel MQB, Parker NH, Valentine AD, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence after curative pancreatectomy: a cross-sectional study in survivors of pancreatic and periampullary tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(13):4078–4084. doi:10.1245/s10434-012-2566-1

- Mehnert A, Berg P, Henrich G, Herschbach P. Fear of cancer progression and cancer-related intrusive cognitions in breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2009;18(12):1273–1280. doi:10.1002/pon.1481.

- van de Wal M, Servaes P, Berry R, Thewes B, Prins J. Cognitive behavior therapy for fear of cancer recurrence: a case study. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2018;25(4):390–407. doi:10.1007/s10880-018-9545-z

- Shand LK, Brooker JE, Burney S, et al. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress in Australian women with ovarian cancer. Psychooncology. 2015;24(2):190–196. doi:10.1002/pon.3627

- Gilbert E, Ussher JM, Perz J. Sexuality after gynecological cancer: a review of the material, intrapsychic, and discursive aspects of treatment on women’s sexual-wellbeing. Maturitas. 2011;70(1):42–57. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.06.013

- O’Connor M, O’Donovan B, Drummond F, Donnelly C. The Unmet Needs of Cancer Survivors in Ireland: A Scoping Review. Cork: National Cancer Registry Ireland; 2019.

- Ferrandina G, Mantegna G, Petrillo M, et al. Quality of life and emotional distress in early stage and locally advanced cervical cancer patients: a prospective, longitudinal study. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(3):389–394. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.09.041.

- Rositch AF, Burke AE, Viscidi RP, Silver MI, Chang K, Gravitt PE. Contributions of recent and past sexual partnerships on incident human papillomavirus detection: acquisition and reactivation in older women. Cancer Res. 2012;72(23):6183–6190. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2635

- McCallum M, Jolicoeur L, Lefebvre M, et al. Supportive care needs after gynecologic cancer: where does sexual health fit in? Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(3):297–306. doi:10.1188/14.onf.297-306.

- Cohee AA, Adams RN, Johns SA, et al. Long-term fear of recurrence in young breast cancer survivors and partners. Psychooncology. 2015;26(1):22–28.

- Suvaal I, Hummel SB, Mens JWM, et al. A sexual rehabilitation intervention for women with gynaecological cancer receiving radiotherapy (SPARC study): design of a multicentre randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):1–14. doi:10.1186/s12885-021-08991-2

- Yates P, Nattress K, Hobbs K, Juraskova I, Sundquist K, Carnew I, Cancer Australia. Improving the psychosexual care of women affected by gynaecological cancers: an interactive web‐based communication skills module. Asia‐Pacific J Clin Oncol. 2010;6(S3):231.

&

Appendix

Table A1. Themes and prevalence across participants.

‘Mind-Map’ of results