Abstract

Objective: The aim of this work was to review evidence on the association between psychological rumination and distress in those diagnosed with cancer. Methods: Six databases were searched for studies exploring rumination alongside overall assessments of psychological distress, depression, anxiety, or stress. Results: Sixteen studies were identified. Rumination was associated with distress cross-sectionally and longitudinally. However, once baseline depression was controlled for, the association was no longer seen. The emotional valence of ruminative thoughts and the style in which they were processed, rather than their topic, was associated with distress. Brooding and intrusive rumination were associated with increased distress, deliberate rumination had no association, and reflection/instrumentality had mixed findings. Conclusions: This review highlights that it is not necessarily the topic of content, but the style and valence of rumination that is important when considering its association with distress. The style of rumination should be the target of clinical intervention, including brooding and intrusion.

Background

Each year, an estimated 17 million new cases of cancer are diagnosed worldwide.Citation1 Receiving a cancer diagnosis represents a set of significant psychological and physical threats.Citation2,Citation3 Those diagnosed face uncertainties about the future and risk of metastasis, while experiencing disruption to their everyday life.Citation4,Citation5 Unsurprisingly, as many as 80% of those diagnosed with cancer experience distress.Citation6,Citation7 Psychological distress represents a range of emotional components,Citation8 including symptoms of anxiety and depression, which are frequently assessed as measures of distress in cancer populations.Citation9–12 Although for many distress resolves over time, for some, distress is experienced long term and can influence treatment outcomes, quality of life, and recovery.Citation13–16 Given the impact on psychological and physical health, understanding factors that influence distress remains important in psychosocial oncology research.Citation17 Identifying potential factors that contribute to distress is important to enable early intervention for those at risk and attempt to reduce experiences of distress.Citation18–21

The way in which illness-related material is cognitively processed has been highlighted as a contributing factor of adjustment to chronic illness.Citation3,Citation20,Citation22 Rumination, a type of perseverative cognition, involves the processing of self-focused information regarding an individual’s problems and concerns.Citation23,Citation24 Ruminative thoughts are conscious and repetitive and are often unified by a common theme.Citation25,Citation26 Although derived from the same underlying process, rumination is considered multifaceted and can occur in different variations. For example, ruminative thoughts can center on a depressed mood, illness, or work-related issues. Some thoughts may dwell on negative events, and some focus on what can be done about problems.Citation27,Citation28 The tendency to ruminate in response to a stressor is generally considered to be a trait-like construct or “cognitive habit” used in an attempt to gain insight into the source of concern.Citation29–31 It has been estimated that around 46% of those diagnosed with cancer experience ruminative thoughts.Citation32 As a cancer diagnosis can force reevaluation of life goals and create a divide between the healthy and real self,Citation33 rumination may be engaged as a means to make sense of this disparity.

Although used to gain insight into problems, persistent rumination is often unconstructive and has been considered a vulnerability to psychological distress.Citation24,Citation34 Models used to understand how rumination may be associated with distress highlight the roles of cognitive deficits in executive control and positive and negative metacognitive beliefs.Citation35–37 Cognitive deficits and beliefs that rumination is helpful or uncontrollable initiate and maintain rumination, leading people to become stuck in a pattern of repetitive thinking in which they struggle to disengage.Citation38,Citation39 Attention is focused on the sources of threat and negative information that interferes with problem-solving, facilitates further rumination, and ultimately maintains distress.Citation40,Citation41

The association between distress and rumination has been well established in physically well populations.Citation42–44 Increased symptoms of depression and anxiety have been reported in those who ruminate.Citation45–47 However, distress after a cancer diagnosis represents a very different experience to that within nonclinical populations. People experience a multitude of emotions, including shock, anger, sadness, and fear, while experiencing distress in response to medical procedures, waiting for appointments, and uncertainty.Citation48–50 Rumination may present in a different manner, where negative or distressing thoughts may not always be uncommon or irrational.Citation51,Citation52The association between distress and rumination therefore cannot be inferred from research within nonclinical populations and should be explored separately.

Early evidence suggests that rumination plays a role in the psychological adjustment to physical illness.Citation53,Citation54 Rumination has been associated with greater difficulties in adjusting to a cancer diagnosis, but it has also been associated with positive outcomes such as posttraumatic growth.Citation32,Citation55,Citation56 As rumination is considered multifaceted, it is thought to encompass both maladaptive and adaptive components depending on the type of rumination.Citation40,Citation45,Citation57 However, at present there is no agreed-upon conceptualization of rumination. Some have argued that there are many distinct types depending on theme, emotional valence, and style.Citation25 Distinctions have been made between more reflective and controlled styles of rumination and brooding and intrusive styles, all of which may be differentially associated with outcomes.Citation55,Citation57 However, comparisons of different types of rumination with distress have not yet been reviewed in psycho-oncology research, and the potential adaptive nature of rumination remains in debate. Identifying what types of rumination are associated with distress is important to identify maladaptive targets for intervention.

With the importance of discovering potential contributors of cancer-related distress, an increasing number of studies have started to explore rumination alongside distress in those diagnosed with cancer. As emerging papers are published, a systematic review of the current literature is timely and informative to both clinicians and researchers. The results of the review could help guide future research and better inform whether rumination is associated with distress in those diagnosed with cancer and how this association is influenced by different types of rumination. If rumination is associated with distress after a diagnosis of cancer, this could be a potential target for intervention.

The primary aim of this review is to systematically identify and evaluate the evidence on whether rumination is associated cross-sectionally and prospectively with psychological distress in those with a current or previous diagnosis of cancer. The secondary aim of this review is to then explore whether different types of rumination (including content, valence, and style) are differentially associated with different distress outcomes.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This review was conducted following the PRISMA guidelinesCitation58 and was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration ID: CRD42021234846).

Criteria for inclusion/exclusion

Studies were included if they quantitatively measured rumination and a form of psychological distress (including anxiety, depression, and stress) in people previously diagnosed with any form of cancer. Due to the novelty of the research, no time frame for diagnosis was included.

Studies meeting the following criteria were included: used a sample of adults (older than 18 years), used a validated measure of rumination, and used at least one validated measure of psychological distress. Studies were excluded if they were not peer reviewed and no grey literature was included.

Search strategy and study selection

Studies were identified by searching the following databases: Embase, Medline, CINAHL, PsycInfo, Web of Science, and Google Scholar (the first 200 articles from the search). This was in accordance with guidelines for conducting psychology reviews.Citation59 Reference lists of included studies and other relevant reviews were hand-searched to identify other possible eligible studies. Search terms included words relevant to (1) psychological distress (including depression, anxiety, negative affect, and stress), (2) perseverative thinking (rumination), and (3) cancer. See Appendix A for search terms used. Searches were limited to the English language. No date or methodological restrictions were applied. Searches were conducted in March 2021 and updated in May 2022.

All potentially relevant titles and abstracts were downloaded into a reference management database (EndNote) where duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts of the remaining articles were screened for their eligibility by the first author, followed by full-text records by two reviewers independently. Results were compared and discrepancies were amended by discussion.

Quality assessment

The quality of the included studies was independently evaluated by the reviewers using a modified Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool,Citation60 adapted for use with papers included in this review. Ratings were given across 5 components (sample selection, study design, confounders, data collection methods, and withdrawal). Each component was rated on a 3-point scale of being either weak, moderate, or strong. Ratings were based on information clearly provided within the study articles. Slight adaptions were made to fit the included studies more appropriately (e.g., blinding was omitted from this review as it was not reported within the studies). An overall score was then given based on the scores on each component. Assessments were completed separately by two reviewers and then compared. Discrepancies were amended by discussion.

Data extraction and synthesis

Descriptive and quantitative analysis of data retrieved was conducted. The following data were extracted from each included study: study characteristics (design, measures, type of distress, type of rumination), participant and cancer characteristics (age, gender, site of cancer, stage of cancer, time since diagnosis) and main findings. Findings that measured rumination within a mediation or moderation model were also included. Some studies included multiple styles of rumination and multiple distress outcomes.

Results

Study selection

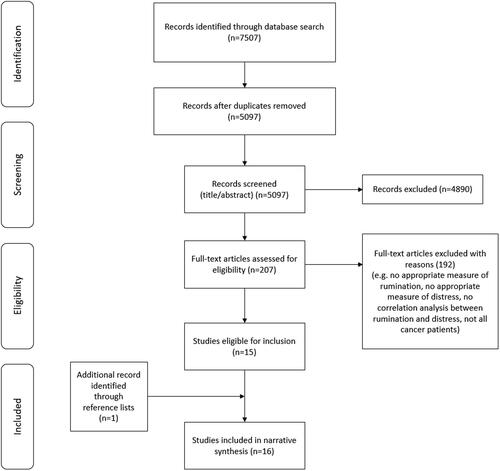

Sixteen eligible studies were included in this review. Fifteen were identified through the database searches and one additional study through the reference list of a relevant paper. Details of the study selection process are shown in .

Study characteristics

There were 10 cross-sectional studiesCitation33,Citation61–69 and 6 longitudinal studies (3 follow-ups at 1,Citation70 3,Citation71 and 8Citation72 months and 3 over multiple time points across 12 months,Citation73 21 months,Citation74 and 5 yearsCitation9). Characteristics and main findings of all included studies are given in .

Table 1. Study characteristics and findings of included papers.

Samples

Studies were conducted across 10 countries and included 2844 participants (range, 55 to 509; mean, 177.75; median, 155). Mean age of participants ranged from 47.5 to 65.9 years. Nine papers used a sample of 100% female,Citation21,Citation33,Citation61–63,Citation65,Citation69,Citation70,Citation74 with the remainder of the studies ranging from 46% to 80% female (total female N = 2504, 88.05%).

Seven studies explored rumination in those diagnosed with breast cancer only,Citation33,Citation61,Citation65,Citation69,Citation70,Citation73,Citation74 five in samples of mixed cancer,Citation9,Citation64,Citation66–68 two in colon/colorectal cancer,Citation71,Citation72 one in ovarian cancer,Citation62 and one in gynecological cancer (including ovarian and uterine).Citation63 In those that reported information on cancer diagnosis, most studies included those in stage 0 to IV or I to IV. Included studies were mixed in time since diagnosis/treatment of their sample (ranged from 1 week postdiagnosis to more than 10 years).

Measures

Across all studies, eight different measures of rumination were used. These included the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS; seven papers including the revised version), Event-Related Rumination Inventory (ERRI; two papers), Chinese Cancer Related Rumination Scale (CCRRS; one paper), Rumination Reflection Questionnaire (RRQ; one paper), Multi-dimensional Rumination in Illness Scale (MRIS; one paper), The Rumination Scale (TRS; one paper), and the Rumination subscale from the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ; 3 papers including the shortened version). All studies measured trait rumination (no paper assessed current/state rumination or induced rumination); however, one paper also examined differences in rumination within participants.Citation74

Four types of distress were measured (psychological/emotional distress, depression, anxiety, and stress) using seven different measures. Some papers measured multiple types of distress.

Quality appraisal

presents the component and overall quality assessment scores given for each included study. Based on the global quality ratings, 10 papers were weak,Citation33,Citation61–66,Citation68,Citation69,Citation71 2 were moderate,Citation9,Citation67 and 4 were strong.Citation70,Citation72–74 The main reason for some of the weaker studies was the nature of the design assessment from the quality tool. Due to the constraints of the EPHPP, cross-sectional studies were considered to be weaker in design, which may or not be an exact reflection of the quality of research.

Table 2. Quality assessment of included studies.

Categorization of rumination

There was considerable heterogeneity in the type of rumination measured based on the high number of measures used. See for a visual breakdown of the types of rumination assessed in the included studies. Most papers used an overall score of rumination, and some explored different styles in which ruminative thoughts were processed (brooding, intrusion, deliberate, and reflection). Additionally, papers varied on the content (topic and emotional valence) of ruminative thought assessed. For example, seven papers measured rumination in response to a depressed mood,Citation9,Citation61,Citation64,Citation66–68,Citation74 four measured rumination in response to illness/cancer,Citation33,Citation62,Citation71,Citation73 three measured rumination in response to a stressful event,Citation63,Citation65,Citation70 one measured rumination of no specified theme,Citation72 and one assessed rumination in response to depressed mood and cancer.Citation69 One paper also explored the valence of ruminative content, comparing positive and negative ruminative thoughts.Citation73 To ease the understanding of findings, results are categorized into overall rumination (cross-sectional and longitudinal findings), style of rumination, and content of rumination.

Table 3. Categorization on type of rumination measured across studies.

Overall rumination and psychological distress

Of the 16 studies, nine explored overall rumination scores and psychological distress. Measures of overall rumination did not specify a particular style of rumination, but captured an overall assessment of the amount of ruminative thought experienced by participants. Results are divided into cross-sectional findings and longitudinal findings. Main findings from all included studies are summarized in .

Cross sectional findings

Seven papers reported results of a cross-sectional association between psychological distress, anxiety, and/or depression with rumination. In one paper, rumination was positively associated with a general measure of psychological distress.Citation68

In papers correlating rumination and anxiety, most found significant bivariate associations. Rumination was associated with higher anxiety in mixed cancer samplesCitation66,Citation68,Citation71 and in women with ovarian and uterine cancer.Citation63 These papers assessed anxiety in terms of symptoms over the previous week or month (DASS, HADS, and MHI). Moreover, those with a higher tendency to ruminate were more likely to be classified with clinical anxiety.Citation68 One study found no association between rumination and anxiety when measuring symptoms of anxiety at that current momentCitation65 (STAI).

Rumination was significantly associated with higher depression in mixed cancer samplesCitation64,Citation66,Citation71 and in women with breast cancer.Citation65,Citation69 Those with a higher tendency to ruminate were also more likely to be classified with clinical depression.Citation68 One study, however, found rumination not to be associated with depression in women with ovarian and uterine cancer.Citation63 It should also be noted that when repeating rumination and distress (depression and anxiety) measurements 3 months later, Salsman and coworkers (2009) did not replicate their significant association at baseline. The paper does not provide further details on this.

Longitudinal findings

Three studies explored overall rumination score and distress longitudinally or with a follow-up. Rumination at baseline was seen to be associated with anxiety and depression at a 3-month follow upCitation71 and with depression at an 8-month follow up.Citation72 In those categorized within high-depression groups 1 month later, rumination was seen to be higher relative to those within low-depression groups.Citation70 However, once baseline depression was controlled for, rumination was no longer associated with depression scores or depression group in either study.Citation70,Citation72

Style of rumination

Some papers explored specific styles of rumination (how ruminative thoughts are processed). This review highlighted four main separate style groups of rumination: brooding, intrusion, deliberate, and reflection/instrumentality. Definitions of these styles are provided below.

Brooding

Six papers explored “brooding,” a style of rumination involving passive judgmental thoughts and self-blame. Two types of brooding were highlighted: brooding and depressive brooding. Depressive brooding was associated with anxiety and depression.Citation61 Similarly, brooding was associated with higher anxiety, depression,Citation33,Citation61,Citation64 and stressCitation33 in women with breast cancer and with depression in those with mixed types of cancer.Citation67 In longitudinal analyses, brooding was found to be associated with depressive symptoms at baseline and 3, 9, and 21 months later in women with breast cancerCitation74 and with anxiety and depression during a 5-year follow-up in a mixed cancer sample.Citation9

When controlling for reflection, brooding was associated with depression,Citation74 and when controlling for instrumentality and intrusion, brooding about illness was associated with higher depression, anxiety, and stress.Citation33 In addition, higher brooding at the within level (changes over time) was associated with higher depression cross-sectionally and prospectively when controlling for within levels of reflection.Citation74

Intrusion

Two papers assessed intrusive rumination, defined as ruminative thought that is unintentional and difficult to control. Intrusive rumination of cancer-/illness-related information was associated with psychological distress when deliberate rumination was controlled forCitation62 and stress when brooding and instrumentality were controlled for.Citation33

Deliberate

One paper assessed deliberate rumination,Citation62 the act of ruminating at will and being in control of when rumination is engaged. Deliberate rumination was found to be associated with psychological distress. However, this was no longer significant when intrusive rumination was controlled for.

Reflection/instrumentality

Five studies assessed reflection/instrumentality, the purposeful turning inward in an attempt to problem-solve. Findings of the association between reflection and distress were mixed. Reflection was not associated with depression in patients with colon cancer at baseline or 8 months later.Citation72 When controlling for brooding and other coping strategies, within- and between-person reflection scores were not associated with depression.Citation74 Instead, instrumentality around illness was found to be associated with lower depression and stress scores when intrusion and brooding were controlled for.Citation33

With no other styles of rumination controlled, reflection was associated with higher depressive symptoms in a sample of patients with mixed types of cancerCitation64 and with higher anxiety and depression in those with breast cancer.Citation61 Similarly, when not controlling for brooding or coping strategies, Wang and associates (2020) did find reflection to be associated, albeit weakly, with higher depression at baseline (3 months after treatment). However, this association became weaker 3 and 9 months later and nonexistent after 21 months.

Content of rumination

No stark dissimilarities were found between studies that assessed different topics of rumination content. For example, rumination in response to a depressed mood, a stressful event, and a cancer diagnosis were all similarly associated with psychological distress. One study, however, found the valence of rumination content to be differentially associated with distress. Lam and colleagues (2013) found that those who ruminated about negative cancer-related content were more likely to be categorized as having high stable levels of anxiety and depression over 12 months. Those who ruminated about positive cancer-related content were more likely to report low levels of anxiety and depression (they were less likely to have depression or anxiety).

Other processes involved in rumination and psychological distress

Some papers also explored other factors associated with distress alongside rumination. Rumination was associated with depression in those with high levels of fear of recurrence, but not those with low levels of fear of recurrence.Citation66 Similarly, higher reflective rumination was associated with lower depression in those using disengagement coping and higher depression in those who used engagement coping.Citation74 Gender was also found to moderate the association between brooding and anxiety. Men with high brooding reported greater anxiety than women.Citation9

Rumination mediates association between psychological distress and other variables

Depressive rumination mediated the relationship between harm/loss appraisal and depressive symptoms.Citation69 Low levels of depressive brooding mediated the relationship between self-compassion and distress,Citation61 age and depressive symptoms, and the relationship between thanksgiving prayer and depressive symptoms fully.Citation67

Rumination (including brooding and reflection also) was found to mediate the association between dysfunctional attitudes and depressive symptoms.Citation64 Yet, in the same study dysfunction attitudes were also seen to mediate the relationship between rumination and distress.

Discussion

This systematic review is the first synthesis of published literature exploring the cross-sectional and prospective association between rumination and distress in those diagnosed with cancer. The majority of studies reported a significant, positive association between rumination and distress; however, in longitudinal studies that controlled for baseline depression this association was no longer seen. In relation to the second aim of this review, the valence of ruminative thought rather than the topic was found to be associated with distress. Moreover, more negative styles such as brooding and intrusion were associated with higher distress, whereas associations between distress and deliberate, reflection, and instrumentality styles were mixed.

Overall rumination and distress

Overall rumination was associated with clinical and nonclinical psychological distress cross-sectionally and longitudinally. In general, there was a positive association between overall rumination and trait anxiety and depression (symptoms of distress over a period of time, e.g., the previous week or month). Rumination was not, however, associated with state anxiety. This is not surprising as the included papers in this review all assessed trait rumination and not whether participants were ruminating at the time of the study. Those with a trait tendency to ruminate do so at certain times, not necessarily all the time.Citation75 Therefore, it may be that some aspects of distress, such as anxiety, are experienced only during times of rumination which would be captured by trait, not state, measures of anxiety. However, as only one paper of weak quality assessed state anxiety and no studies explored state or induced rumination, this association remains unclear.

Contrary to the papers that found an association between overall rumination and depression, one cross-sectional study did notCitation63, and another failed to replicate their original association found 3 months prior.Citation71 This may have been due to the way rumination was assessed. Kulpa and colleagues authored the only study to use a shortened subscale measure of rumination. Although initial validity was shown,Citation76 its reliability and validity has since been questioned with one of the two items considered as tapping into curiosity rather than rumination.Citation77 Similarly, Salsman and colleagues used a measure that in their own paper had questionable and adequate internal consistency, has reported weak consistency in previous research,Citation78 and has been critiqued as containing items reflecting worry rather than rumination.Citation79 These measures may not have captured the same rumination construct as the other included papers.

Additionally, an important caveat to the significant association between overall rumination and depression was seen in the longitudinal studies that controlled for baseline depression. When baseline depression was controlled for, rumination was no longer associated with depression at follow-up. Some theoretical models define rumination and depression as having a reciprocal relationship, where rumination forms a part of depression as well as being a vulnerability factor.Citation80 Rumination is experienced in response to a negative mood, which it then prolongs in a cyclical manner.Citation81 As such, removing the shared variance of depression and rumination may affect their association in longitudinal studies. However, only two of the six longitudinal studies in this review controlled for baseline distress. Future research should explore whether rumination is independently associated with distress or whether it is the shared variance responsible.

Type of rumination

The findings from this review suggest it may not be the topic of ruminative thoughts that is key when considering distress in cancer, but their style and valence. The main styles of rumination apparent in this review included brooding, intrusion, deliberate, and reflection/instrumentality, consistent with literature on depressive and posttraumatic rumination.Citation57 Intrusion and brooding are believed to overlap to form maladaptive rumination, whereas reflection and deliberate may overlap to represent more adaptive forms.Citation82 In line with this presentation and previous research (e.g., Javaid et al.Citation83; Morris-Shakespeare and FinchCitation84), brooding and intrusion were more consistently associated with increased distress compared to deliberate rumination. Reflection, on the other hand was more complex and inconsistent; with some research showing positive associations with distress, while others demonstrated no association. This is in line with the current debate in the literature on the adaptive nature of reflection. This review found reflection, on the most part, not to be associated with anxiety and depression. This is supported by Guan and associates (2021), who found intrusion and brooding, not reflection and deliberate rumination, to be associated with depression and anxiety in cardiac patients.

Ruminating about negative cancer-related content was associated with higher depression and anxiety compared to ruminating about positive content. This may be because when ruminating about negative material, attention is focused on negative content which increases emotional arousal.Citation85,Citation86 Ruminating on more positive content may not elicit the same distress response. Some evidence has suggested that positive rumination may even be protective against depressive symptoms by buffering against negative outcomes of rumination.Citation87 As most measures used in this review tap into rumination on negative affect, that is, depressive rumination, rather than on positive affect,Citation88 the valence of thoughts could determine whether distress is maintained.

Rumination and other factors

Factors alongside rumination were explored to explain more about its association with distress. Moderators included fear of recurrence, engagement/disengagement coping, and gender. Rumination was associated with depression in those with high fear of recurrence, but not low, while brooding was associated with anxiety in men with high rumination, but not women. Higher reflective rumination was associated with lower depression in those using disengagement coping, and higher depression was found in those who used engagement coping. This suggests that rumination can exacerbate issues in certain genders or those with an underlying vulnerability such as fear of recurrence, but it also suggests that some styles can have a protective or harmful effect when used in combination with other coping strategies.

Quality of research

The quality of the included studies was variable. Quality was mostly compromised by the use of a cross-sectional design. More research is needed to explore the association between rumination and distress prospectively and over time in those diagnosed with cancer. Longitudinal research should also consider controlling for baseline distress to be able to decipher whether rumination is independently associated with distress or whether it is the shared variance that is responsible.

Additionally, some papers used the CERQ which, although validated, is not the most comprehensive measure of rumination.Citation77 Many papers also used depressive rumination measures which may have some overlap with depression and/or negative emotion.Citation28,Citation69 Depressive thoughts may not be uncommon after a diagnosis of cancer and, as such, measures that focus on depressed mood may not be completely suitable. Future research could benefit from using more distinct rumination measures when examining distress.

Study limitations

Some limitations of this review should be acknowledged. There was much heterogeneity in the measures used to assess rumination, which made comparisons between studies more difficult. To help synthesize the findings, results were qualitatively grouped into types of rumination (overall rumination, style, and content). It could be argued that some measures fit more appropriately to their allocated group than others. Although they are distinct, there is much overlap between the different styles of rumination.Citation82 Instrumentality and reflection may involve deliberate rumination, representing purposeful engagement in ruminative thought.Citation33 Nevertheless, the layout provides a clearer way of understanding how different styles and content of rumination may be differently associated with distress.

As this is the first time research on rumination and cancer distress has been synthesized in this way, the current review included all types of cancer at any points after diagnosis. Although no clear differences by site of cancer or duration since diagnosis appeared in this review, there may be nuances missed in the distress or rumination experience. Likewise, age and gender have been shown to be influential in rumination,Citation89,Citation90,Citation91 and differences in the relationship between rumination and depression have been seen across ethnicities.Citation92 As participant age and ethnicity were not controlled for and the studies included mainly women, this may have impacted the results.

Clinical implications

The findings of this review suggest that having a ruminative thinking style is associated with psychological distress including depression and anxiety after a cancer diagnosis. Therefore, rumination could be used to identify those at risk for distress or as a potential target of interventions.

The findings highlight the importance of the style in which ruminative thoughts are processed when looking at distress. From this review, there appear to be both maladaptive and adaptive forms of rumination, which may contribute to differential outcomes in those diagnosed with cancer.

This review identified four main styles, supporting previous research.Citation57 As different styles may increase, decrease, or have no effect on distress, it may be too simplistic to aim to solely reduce rumination. Interventions may seek to avoid reducing rumination as a whole and instead be designed to reduce the maladaptive styles of rumination, particularly brooding and intrusion, and rumination of negative valence. Interventions may also seek to work with patients to change their rumination style from brooding and intrusion to a more deliberate and instrumental style. Components of preexisting interventions used in oncology such as acceptance and commitment therapy could be tailored to include styles of rumination when considering which thoughts are helpful and which are not, rather than reducing all rumination. It would be useful to map existing interventions in psycho-oncology to see where the greatest benefit may be for patients. For example, our previous research showed that imagery rescripting could be a powerful tool to address intrusive thoughts in people diagnosed with cancerCitation93 and may be relevant for those experiencing an intrusive rumination style.

Conclusions

This review presents an overview of the current research exploring rumination and distress in those diagnosed with cancer. The main and consistent finding was that emotional valence and style of rumination are important when interpreting the association between rumination and distress. Ruminating on negative cancer-related content and maladaptive styles such as brooding and intrusion seem to be uniquely associated with distress, including anxiety and depression. In contrast, ruminating about positive content and in a deliberate or instrumental manner may not be as harmful. More research is needed to decipher the differences between styles of rumination and distress after a diagnosis of cancer within the same sample, and more longitudinal research is warranted to explore changes in this association over time.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

References

- Cancer Research UK. Cancer incidence statistics. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/worldwide-cancer. Accessed March, 2022.

- Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US) National Cancer Policy Board, Hewitt M, Herdman R, Holland J, eds. Meeting Psychosocial Needs of Women with Breast Cancer. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2004. Copyright 2004 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

- Soo H, Burney S, Basten C. The role of rumination in affective distress in people with a chronic physical illness: a review of the literature and theoretical formulation. J Health Psychol. 2009;14(7):956–966. doi:10.1177/1359105309341204

- Dinkel A, Kremsreiter K, Marten-Mittag B, Lahmann C. Comorbidity of fear of progression and anxiety disorders in cancer patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(6):613–619. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.08.006

- Stanton AL, Revenson TA, Tennen H. Health psychology: psychological adjustment to chronic disease. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:565–592. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085615

- Abbey G, Thompson SB, Hickish T, Heathcote D. A meta-analysis of prevalence rates and moderating factors for cancer-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychooncology. 2015;24(4):371–381. doi:10.1002/pon.3654

- Caruso R, Nanni MG, Riba MB, Sabato S, Grassi L. The burden of psychosocial morbidity related to cancer: patient and family issues. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2017;29(5):389–402. doi:10.1080/09540261.2017.1288090

- Vitek L, Rosenzweig MQ, Stollings S. Distress in patients with cancer: definition, assessment, and suggested interventions. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11(3):413–418. doi:10.1188/07.CJON.413-418

- Priede A, Rodríguez-Pérez N, Hoyuela F, Cordero-Andrés P, Umaran-Alfageme O, González-Blanch C. Cognitive variables associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with cancer: a five-year follow-up study. Psychooncology. 2022;31(5):798–805. doi:10.1002/pon.5864

- Ahlberg K, Ekman T, Wallgren A, Gaston‐Johansson F. Fatigue, psychological distress, coping and quality of life in patients with uterine cancer. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45(2):205–213. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02882.x

- Brown SL, Fisher PL, Hope-Stone L, et al. Predictors of long-term anxiety and depression in uveal melanoma survivors: a cross-lagged five-year analysis. Psychooncology. 2020;29(11):1864–1873. doi:10.1002/pon.5514

- Secinti E, Tometich DB, Johns SA, Mosher CE. The relationship between acceptance of cancer and distress: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;71:27–38. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2019.05.001

- Bárez M, Blasco T, Fernández-Castro J, Viladrich C. A structural model of the relationships between perceived control and adaptation to illness in women with breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2007;25(1):21–43. doi:10.1300/J077v25n01_02

- Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullum J, et al. High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(12):2297–2304. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601887

- Costa-Requena G, Rodríguez A, Fernández-Ortega P. Longitudinal assessment of distress and quality of life in the early stages of breast cancer treatment. Scand J Caring Sci. 2013;27(1):77–83. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01003.x

- Helgeson VS, Snyder P, Seltman H. Psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer over 4 years: identifying distinct trajectories of change. Health Psychol. 2004;23(1):3–15. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.3

- Langford DJ, Morgan S, Cooper B, et al. Association of personality profiles with coping and adjustment to cancer among patients undergoing chemotherapy. Psychooncology. 2020;29(6):1060–1067. doi:10.1002/pon.5377

- Dauphin S, Jansen L, De Burghgraeve T, Deckx L, Buntinx F, van den Akker M. Long-term distress in older patients with cancer: a longitudinal cohort study. BJGP Open. 2019;3(3):bjgpopen19X101658. doi:10.3399/bjgpopen19X101658

- Dunn J, Ng SK, Holland J, et al. Trajectories of psychological distress after colorectal cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22(8):1759–1765. doi:10.1002/pon.3210

- Gonzalez BD, Manne SL, Stapleton J, et al. Quality of life trajectories after diagnosis of gynecologic cancer: a theoretically based approach. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(2):589–598. doi:10.1007/s00520-016-3443-4

- Lam WW, Shing YT, Bonanno GA, Mancini AD, Fielding R. Distress trajectories at the first year diagnosis of breast cancer in relation to 6 years survivorship. Psychooncology. 2012;21(1):90–99. doi:10.1002/pon.1876

- Helgeson VS, Zajdel M. Adjusting to chronic health conditions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2017;68:545–571. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044014

- Brinker JK, Dozois DJ. Ruminative thought style and depressed mood. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(1):1–19. doi:10.1002/jclp.20542

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2008;3(5):400–424. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x

- Martin LL, Tesser A. Some ruminative thoughts. Ruminative Thoughts. 1996;9:1–47.

- Smith JM, Alloy LB. A roadmap to rumination: a review of the definition, assessment, and conceptualization of this multifaceted construct. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(2):116–128. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.003

- Cristea IA, Matu S, Szentagotai Tatar A, David D. The other side of rumination: reflective pondering as a strategy for regulating emotions in social situations. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2013;26(5):584–594. doi:10.1080/10615806.2012.725469

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: a psychometric analysis. Cogn Ther Res. 2003;27(3):247–259. doi:10.1023/A:1023910315561

- Watkins ER, Nolen-Hoeksema S. A habit-goal framework of depressive rumination. J Abnorm Psychol. 2014;123(1):24–34. doi:10.1037/a0035540

- Papageorgiou C, Wells A. An empirical test of a clinical metacognitive model of rumination and depression. Cogn Ther Res. 2003;27(3):261–273. doi:10.1023/A:1023962332399

- Thomsen DK, Yung Mehlsen M, Christensen S, Zachariae R. Rumination—relationship with negative mood and sleep quality. Pers Individ Diff. 2003;34(7):1293–1301. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00120-4

- Gorini A, Riva S, Marzorati C, Cropley M, Pravettoni G. Rumination in breast and lung cancer patients: preliminary data within an Italian sample. Psychooncology. 2018;27(2):703–705. doi:10.1002/pon.4468

- Soo H, Sherman KA. Rumination, psychological distress and post-traumatic growth in women diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2015;24(1):70–79. doi:10.1002/pon.3596

- Connolly SL, Wagner CA, Shapero BG, Pendergast LL, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Rumination prospectively predicts executive functioning impairments in adolescents. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2014;45(1):46–56. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.07.009

- DeJong H, Fox E, Stein A. Rumination and postnatal depression: a systematic review and a cognitive model. Behav Res Ther. 2016;82:38–49. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2016.05.003

- Mor N, Daches S. Ruminative thinking: lessons learned from cognitive training. Clin Psychol Sci. 2015;3(4):574–592. doi:10.1177/2167702615578130

- Matthews G, Wells A. Rumination, depression, and metacognition: the S-REF model. In: Papageorgiou C, Wells A, eds. Depressive Rumination: Nature, Theory and Treatment. England: Wiley; 2004:125–151.

- Brosschot JF, Gerin W, Thayer JF. The perseverative cognition hypothesis: a review of worry, prolonged stress-related physiological activation, and health. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(2):113–124. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.06.074

- Darabos K, Hoyt MA. Emotional processing coping methods and biomarkers of stress in young adult testicular cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2020;9(3):426–430. doi:10.1089/jayao.2019.0116

- Guan YY, Phillips L, Murphy B, et al. Impact of rumination on severity and persistence of anxiety and depression in cardiac patients. Heart Mind. 2021;5(1):9. doi:10.4103/hm.hm_38_20

- Lyubomirsky S, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Effects of self-focused rumination on negative thinking and interpersonal problem solving. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(1):176–190. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.69.1.176

- Ehring T, Kleim B, Ehlers A. Combining clinical studies and analogue experiments to investigate cognitive mechanisms in posttraumatic stress disorder. Int J Cogn Ther. 2011;4(2):165–177. doi:10.1521/ijct.2011.4.2.165

- McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49(3):186–193. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.12.006

- Muris P, Roelofs J, Rassin E, Franken I, Mayer B. Mediating effects of rumination and worry on the links between neuroticism, anxiety and depression. Pers Individ Diff. 2005;39(6):1105–1111. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.04.005

- Grierson AB, Hickie IB, Naismith SL, Scott J. The role of rumination in illness trajectories in youth: linking trans-diagnostic processes with clinical staging models. Psychol Med. 2016;46(12):2467–2484. doi:10.1017/S0033291716001392

- Hsu KJ, Beard C, Rifkin L, Dillon DG, Pizzagalli DA, Björgvinsson T. Transdiagnostic mechanisms in depression and anxiety: the role of rumination and attentional control. J Affect Disord. 2015;188:22–27. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.008

- Rude SS, Little Maestas K, Neff K. Paying attention to distress: what’s wrong with rumination? Cogn Emotion. 2007;21(4):843–864. doi:10.1080/02699930601056732

- Cameron LD, Wally CM. Chronic illness, psychosocial coping with. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. 2015;2(3):549–554.

- Pearson M, Brewin CR, Rhodes J, McCarron G. Frequency and nature of rumination in chronic depression: a preliminary study. Cogn Behav Ther. 2008;37(3):160–168. doi:10.1080/16506070801919224

- Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):300–322. doi:10.1007/s11764-013-0272-z

- Fisher PL, Byrne A, Salmon P. Metacognitive therapy for emotional distress in adult cancer survivors: a case series. Cogn Ther Res. 2017;41(6):891–901. doi:10.1007/s10608-017-9862-9

- Edmondson D. An enduring somatic threat model of posttraumatic stress disorder due to acute life‐threatening medical events. Soc Pers Psychol Compass. 2014;8(3):118–134. doi:10.1111/spc3.12089

- Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Rumination: relationships with physical health. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012;9(2):29–34.

- Sears SR, Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S. The yellow brick road and the emerald city: benefit finding, positive reappraisal coping and posttraumatic growth in women with early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2003;22(5):487–497. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.487

- Chan MW, Ho SM, Tedeschi RG, Leung CW. The valence of attentional bias and cancer-related rumination in posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth among women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2011;20(5):544–552. doi:10.1002/pon.1761

- Kolokotroni P, Anagnostopoulos F, Tsikkinis A. Psychosocial factors related to posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors: a review. Women Health. 2014;54(6):569–592. doi:10.1080/03630242.2014.899543

- García FE, Duque A, Cova F. The four faces of rumination to stressful events: a psychometric analysis. Psychol Trauma. 2017;9(6):758–765. doi:10.1037/tra0000289

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

- Bramer WM, Rethlefsen ML, Kleijnen J, Franco OH. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: a prospective exploratory study. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):245. doi:10.1186/s13643-017-0644-y

- Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1(3):176–184. doi:10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x

- Brown SL, Hughes M, Campbell S, Cherry MG. Could worry and rumination mediate relationships between self-compassion and psychological distress in breast cancer survivors? Clin Psychol Psychother. 2020;27(1):1–10. doi:10.1002/cpp.2399

- Hill EM, Watkins K. Women with ovarian cancer: examining the role of social support and rumination in posttraumatic growth, psychological distress, and psychological well-being. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2017;24(1):47–58. doi:10.1007/s10880-016-9482-7

- Kulpa M, Ziętalewicz U, Kosowicz M, Stypuła-Ciuba B, Ziółkowska P. Anxiety and depression and cognitive coping strategies and health locus of control in patients with ovary and uterus cancer during anticancer therapy. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2016;20(2):171–175. doi:10.5114/wo.2016.60074

- Lam KF, Lim HA, Tan JY, Mahendran R. The relationships between dysfunctional attitudes, rumination, and non-somatic depressive symptomatology in newly diagnosed Asian cancer patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;61:49–56. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.06.001

- Lee J, Youn S, Kim C, Yeo S, Chung S. The influence of sleep disturbance and cognitive emotion regulation strategies on depressive symptoms in breast cancer patients. Sleep Med Res. 2019;10(1):36–42. doi:10.17241/smr.2019.00388

- Liu J, Peh CX, Simard S, Griva K, Mahendran R. Beyond the fear that lingers: the interaction between fear of cancer recurrence and rumination in relation to depression and anxiety symptoms. J Psychosom Res. 2018;111:120–126. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.06.004

- Pérez JE, Rex Smith A, Norris RL, Canenguez KM, Tracey EF, Decristofaro SB. Types of prayer and depressive symptoms among cancer patients: the mediating role of rumination and social support. J Behav Med. 2011;34(6):519–530. doi:10.1007/s10865-011-9333-9

- Priede A, Hoyuela F, Umaran-Alfageme O, González-Blanch C. Cognitive factors related to distress in patients recently diagnosed with cancer. Psychooncology. 2019;28(10):1987–1994. doi:10.1002/pon.5178

- Steiner JL, Wagner CD, Bigatti SM, Storniolo AM. Depressive rumination and cognitive processes associated with depression in breast cancer patients and their spouses. Fam Syst Health. 2014;32(4):378–388. doi:10.1037/fsh0000066

- Wang Y, Yi J, He J, et al. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies as predictors of depressive symptoms in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2014;23(1):93–99. doi:10.1002/pon.3376

- Salsman JM, Segerstrom SC, Brechting EH, Carlson CR, Andrykowski MA. Posttraumatic growth and PTSD symptomatology among colorectal cancer survivors: a 3-month longitudinal examination of cognitive processing. Psychooncology. 2009;18(1):30–41. doi:10.1002/pon.1367

- Thomsen DK, Jensen AB, Jensen T, Mehlsen MY, Pedersen CG, Zachariae R. Rumination, reflection and distress: an 8-month prospective study of colon-cancer patients. Cogn Ther Res. 2013;37(6):1262–1268. doi:10.1007/s10608-013-9556-x

- Lam WW, Soong I, Yau TK, et al. The evolution of psychological distress trajectories in women diagnosed with advanced breast cancer: a longitudinal study. Psychooncology. 2013;22(12):2831–2839. doi:10.1002/pon.3361

- Wang AW, Chang CS, Hsu WY. The double-edged sword of reflective pondering: the role of state and trait reflective pondering in predicting depressive symptoms among women with breast cancer. Ann Behav Med. 2021;55(4):333–344. doi:10.1093/abm/kaaa060

- Schütze R, Rees C, Slater H, Smith A, O'Sullivan P. ‘I call it stinkin’ thinkin’’: a qualitative analysis of metacognition in people with chronic low back pain and elevated catastrophizing. Br J Health Psychol. 2017;22(3):463–480. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12240

- Garnefski N, Kraaij V. Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire – development of a short 18-item version (CERQ-short). Pers Individ Diff. 2006;41(6):1045–1053. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.010

- Ireland MJ, Clough BA, Day JJ. The cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire: factorial, convergent, and criterion validity analyses of the full and short versions. Pers Individ Diff. 2017;110:90–95. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.01.035

- Segerstrom SC, Roach AR, Evans DR, Schipper LJ, Darville AK. The structure and health correlates of trait repetitive thought in older adults. Psychol Aging. 2010;25(3):505–515. doi:10.1037/a0019456

- McLaughlin KA, Borkovec TD, Sibrava NJ. The effects of worry and rumination on affect states and cognitive activity. Behav Ther. 2007;38(1):23–38. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2006.03.003

- Rood L, Roelofs J, Bögels SM, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schouten E. The influence of emotion-focused rumination and distraction on depressive symptoms in non-clinical youth: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(7):607–616. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.001

- Moberly NJ, Watkins ER. Ruminative self-focus and negative affect: an experience sampling study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117(2):314–323. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.314

- Öcalan S, Üzar-Özçetin YS. The relationship between rumination, fatigue and psychological resilience among cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2021;31:3595–3604.

- Javaid D, Hanif R, Rehna T. Cognitive processes of cancer patients: a major threat to patients’ quality of life. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2018;28(3):218–221. doi:10.29271/jcpsp.2018.03.218

- Morris BA, Shakespeare‐Finch J. Rumination, post‐traumatic growth, and distress: structural equation modelling with cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2011;20(11):1176–1183. doi:10.1002/pon.1827

- Koster EH, De Lissnyder E, Derakshan N, De Raedt R. Understanding depressive rumination from a cognitive science perspective: the impaired disengagement hypothesis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(1):138–145. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.005

- Zetsche U, Joormann J. Components of interference control predict depressive symptoms and rumination cross-sectionally and at six months follow-up. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2011;42(1):65–73. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.06.001

- Li YI, Starr LR, Hershenberg R. Responses to positive affect in daily life: positive rumination and dampening moderate the association between daily events and depressive symptoms. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2017;39(3):412–425. doi:10.1007/s10862-017-9593-y

- Yang H, Wang Z, Song J, et al. The positive and negative rumination scale: development and preliminary validation. Curr Psychol. 2020;39(2):483–499. doi:10.1007/s12144-018-9950-3

- Kwon H, Yoon KL, Joormann J, Kwon JH. Cultural and gender differences in emotion regulation: relation to depression. Cogn Emot. 2013;27(5):769–782. doi:10.1080/02699931.2013.792244

- Ricarte J, Ros L, Serrano JP, Martínez-Lorca M, Latorre JM. Age differences in rumination and autobiographical retrieval. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20(10):1063–1069. doi:10.1080/13607863.2015.1060944

- Sütterlin S, Paap M, Babic S, Kübler A, Vögele C. Rumination and age: some things get better. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:1–10. doi:10.1155/2012/267327

- Cheref S, Lane R, Polanco-Roman L, Gadol E, Miranda R. Suicidal ideation among racial/ethnic minorities: moderating effects of rumination and depressive symptoms. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2015;21(1):31–40. doi:10.1037/a0037139

- Whitaker KL, Brewin CR, Watson M. Imagery rescripting for psychological disorder following cancer: a case study. Br J Health Psychol. 2010;15(Pt 1):41–50. doi:10.1348/135910709X425329

Appendix A

Search Terms

“Cancer” OR “Oncology”

AND

“rumination” OR “ruminative thinking” OR “ruminative thought”

AND

“depress*” OR “depression” OR “depressive thought” OR “depressive thinking” OR “depressive disorder” OR “anx*” OR “anxiety” OR “anxious” OR “anxiety thought” OR “anxiety thinking” OR “anxiety disorder” OR “stress” OR “stress thought” OR “stress thinking” OR “negative affect” OR “emotional distress” OR “psychological distress”

The following strings were also added to include further papers:

“rumination” OR “ruminative thinking” OR “ruminative thought” OR “worry” OR “worry thought” OR “worry thinking” OR “perseverative thought” OR “perseverative thinking” OR “intrusive thought” OR “intrusive thinking” OR “negative thought” OR “negative thinking” OR “repetitive thought” OR “repetitive thinking”

AND

“depress*” OR “depression” OR “depressive thought” OR “depressive thinking” OR “depressive disorder” OR “anx*” OR “anxiety” OR “anxious” OR “anxiety thought” OR “anxiety thinking” OR “anxiety disorder” OR “stress” OR “stress thought” OR “stress thinking” OR “negative affect” OR “emotional distress” OR “psychological distress”