Abstract

Background:

The experiences of women who develop lymphoedema in the breast or trunk (BTL) after treatment for breast cancer have received little attention in either the academic or clinical setting. Consequently, women’s support needs remain unrecognized.

Objective and Design:

As this study sought to gain an understanding of women’s unheard experiences of a poorly understood condition, it was underpinned by The Silences FrameworkCitation1 which facilitates research into sensitive or marginalized issues.

Sample and Methods:

Fourteen women with BTL participated in individual, unstructured interviews, some using photographs or drawings to reflect their experiences. The data was analyzed using the Listening Guide.Citation2

Findings:

Participants revealed that they were unprepared for the development of BTL; for many, the symptoms were unfamiliar and distressing. Furthermore, their concerns were often dismissed by healthcare professionals (HCPs), leading to long delays in obtaining an accurate diagnosis and treatment. For some women, the practical and emotional impact of developing BTL was profound.

Practice Implications:

Increased awareness and education about the risk of BTL as a potential side-effect of treatment for breast cancer is required for HCPs and patients. This will alleviate distress, better prepare patients, and ensure timely referral for treatment to manage this chronic condition.

Introduction

… people don’t see there being any lasting effects of breast cancer … I think people just don’t realise …

(Alice)

The celebratory attitude toward survivorship promoted by the ‘pink ribbon’ culture denies the fact that many individuals who have breast cancer are living diminished lives because of treatment side-effects.Citation3,Citation4 Side-effects include lymphoedema, a chronic condition resulting in swelling from an accumulation of protein-rich lymph fluid. The arm, breast, and trunkFootnote1 are all at risk of developing lymphoedema because they share lymphatic drainage routes at the axilla, often a site of surgery and radiotherapy for breast cancer. Yet the academic literature shows a strong bias toward research about arm lymphoedema. In contrast, breast or trunk lymphoedema (BTL) has received little research attention, resulting in limited knowledge and understanding among healthcare professionals (HCPs). This has an impact upon the ability of HCPs to prepare patients for this potential treatment side-effect, to recognize the symptoms, and to refer patients for appropriate management.

Although a range of symptoms for breast lymphoedema has been described in the literature including swelling, pain, heaviness, redness, skin thickening and peau d’orangeCitation6, the lack of an accepted definition for BTL has hindered the development of an evidence base.Citation7 Determining the true incidence remains problematic, contributing to the wide variation of breast lymphoedema reported of between 0% and 90.4%.Citation8 Several risk factors have been proposed, including patient characteristics such as age and breast volumeCitation9 and treatment aspects such as length of fractionation schedule for radiotherapyCitation10 and post-operative complications.Citation11 Meanwhile there is a stark absence of evidence about women’s experiences of living with BTL, leaving healthcare services unequipped to address patients’ support needs. The purpose of this study was to explore those experiences to generate findings which could be used to inform and improve healthcare.

Methodological approach and study design

The investigation was underpinned by a conceptual framework known as The Silences FrameworkCitation1 which provides a lens through which to understand marginalized or sensitive issues. Acting as a guide throughout the research process, at its core is the concept of ‘screaming silences’ which represent issues or experiences which are undervalued, under-researched or ignored.Citation1 These issues resonate loudly for those experiencing them while they remain absent from wider discourses in society. ‘Screaming silences’ reflect how power is executed and what is accepted as knowledge at any particular time. In this study, the ‘screaming silences’ were proposed to be within women’s experiences of developing and living with BTL. The Silences Framework provides a four-stage process for exploring silenced issues. Tasks include examining the interdependent perspectives of the researcher’s background and influence on the silences which are ‘heard’; the unexplored or sensitive aspects of the research; and the absent voices of – in this instance - women who have BTL. The framework offers a cyclical process of analysis, incorporating feedback on the proposed themes (see below for more detail). In the final stage, the researcher considers the degree to which silences have been highlighted, altered, or indeed generated through the study. Recommendations for policy or practice are made considering the findings in terms of the expected benefits to addressing the exposed silences.

Eligible participants were female and at least 18 years old. Men were excluded from this exploratory study as they constitute less than one per cent of cases of breast cancer.Citation12 Participants had developed lymphoedema in their breast or trunk after breast-conserving surgery, mastectomy, or radiotherapy for breast cancer. They were identified through the recruitment avenues approved by the NHS research ethics committeeFootnote2. These included a local lymphoedema service acting as the participant identification site (n = 8); a cancer support center (n = 1); word-of-mouth (n = 3) and via social media outlets (n = 2). Written informed consent was obtained. Participants were invited to use photographs during their interview which reflected their experiences; however, this was not a condition for participation.

JU undertook individual, unstructured, audio-recorded, face-to-face or telephone interviews with participants, lasting between 19 minutes and one hour 22 minutes. JU also maintained a research diary throughout the study, incorporating reflective notes. Personal information was shared by JU with participants if it was felt that it would engender an open, equal relationship.

The Voice-Centred Relational Method - specifically its analytical tool the Listening GuideCitation2 - was used for data analysis. This method draws upon relational beliefs about the self as experienced in relation to others.Citation13,Citation14 Its four steps enable the researcher to develop a multi-layered understanding of a participant’s narrative. Hence ‘listening’ occurs in the literal sense of attending to the interview recordings but is also a particular way of following the transcripts, noticing the different ‘voices’ in which a person speaks and their way of thinking. An example of this process, including the development of themes from the data, is provided in the supplementary materialFootnote3. In this analysis, the meaning of any images used during the interview was also established by noting how they were discussed by the participant.

During the developing analysis MD, LS and HP contributed to the verification process by reviewing examples of JU’s interpretation of the data alongside the related interview transcripts. When inviting participants to provide feedback on proposed themes, they were also provided with their interview transcript for reference. Assisted by ATLAS.ti softwareFootnote4, broader provisional themes were subsequently developed from participants’ individual themes and shared with participants. The proposed findings were also shared with members of the ‘collective voices’,Citation1 who in the current study represented others with personal or clinical experience of lymphoedema (in the breast, trunk, or arm) after treatment for breast cancer. This enabled the researcher to establish whether the findings resonated with those beyond the research setting and so had potential to transfer to similar contexts.

Participants were placed in the position of expert as JU had no knowledge of the topic prior to the investigation. JU, MD, LS and HP all have prior experience of conducting and analyzing qualitative research. HP has extensive experience of cancer care as a therapeutic radiographer and of research relating to radiotherapy for breast cancer. LS developed The Silences Framework and brought considerable experience in the use of this framework across a range of research topic areas. None of the authors were involved in any aspects of the participants’ cancer care and MD, LS and HP had no direct contact with the study participants, providing an independent perspective to the data analysis.

Findings

Fourteen women aged between 41 and 83 years participated in the study; all participants identified themselves as White. Most had lymphoedema in their treated breast, the remaining participants having it predominantly in the trunk (n = 1) or chest wall (n = 2) area. Some women also had lymphoedema in the arm or armpit. Time since treatment ranged from several months to several years. Six participants opted to be interviewed in their own home; the others selected venues known to them, such as their workplace. Two interviews were conducted by phone. Ten participants used images (photographs or drawings) during their interview to reflect aspects of their experiences. All names used below are pseudonyms, apart from in one instance where the participant has opted for her real first name to be used.

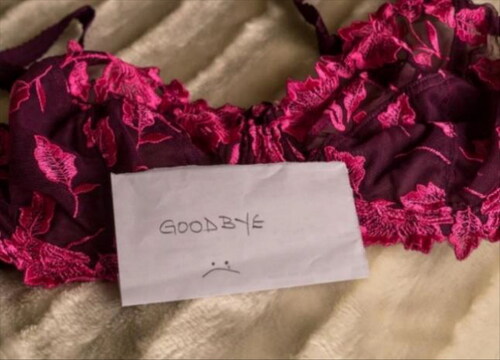

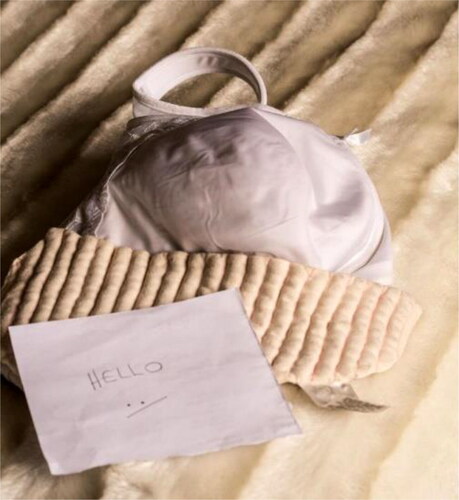

Figure 1. My breast was feeling very hard and lumpy… like there were stones in it (Zoe). © Zoe (a pseudonym). Reuse not permitted.

The themes developed from the interview data are presented in . The key theme mysterious breast or trunk lymphoedema reflects the point at which participants developed symptoms. Women described limited chest and shoulder movement, sharp or ‘jabbing’ pains, tightness, redness, hardness, heaviness, prickliness, heat, soreness, and severe swelling persisting for many months or more. Zoe reported that “my breast was feeling very hard and lumpy … like there were stones in it” () adding that she felt “like there was an insect crawling under my skin.” The swelling could fluctuate, prompting Sandra to take photographs as evidence for her clinical appointments of how it appeared at its worst. For Sharon, her pain and subsequent despair were so great that she asked her breast surgeon to remove her breast altogether. Leah described how her painful breast lymphoedema affected her sleep:

Table 1. Key themes, themes, and sub-themes.

it used to wake me up in the night … the jabbing pains I can only describe as like an electric shock, like a zzzz, that kind of oh! –

Feelings of uncertainty were exemplified by Joanna: “is it going to keep getting bigger or what’s going to happen with it?” Several participants believed that their experiences of fatigue were associated with having breast lymphoedema. Significantly, several became anxious that their symptoms were an indication of cancer recurrence.

Overall, participants could not recall being told about BTL as a potential side-effect of treatment; patient information about lymphoedema was limited to the arm. The situation was compounded by some women having difficulty acknowledging their symptoms, “not wanting to accept what was going on …” (Joanna). Moreover, there often appeared to be a silence around the topic which may be related to the breast as a sensitive subject for discussion. Some women suggested that, once their treatment for breast cancer was finished, there were limited opportunities to discuss symptoms with their healthcare team; Jackie remarked that she felt as though she had “fallen off a cliff.” In addition, many HCPs appeared unknowledgable about BTL. Their responses are reflected in the key theme you meet a wall, representing an attitude of indifference or dismissiveness. For example, Zoe was told by her breast care team that breast lymphoedema was “very, very rare.” At times a misdiagnosis resulted in inappropriate treatment, such as repeated antibiotics for presumed cellulitis. Sometimes recognition of BTL appeared to occur by chance at a follow-up mammogram or during attendance at one of Breast Cancer Now ‘s ‘Moving Forward’ course sessions.

In the absence of a prompt assessment and accurate diagnosis, some women experienced prolonged periods of anxiety and a worsening of their symptoms. One participant endured breast lymphoedema for two years before she was able to access treatment. Trying unsuccessfully to get HCPs to listen to her concerns, Samantha reflected:

… the doctors not listening and not acknowledging. That just made, I guess, all my appointments stressful because … I’d been preparing for them thinking, well, how can I really try and get them to listen to this? … just to get knocked back every time …

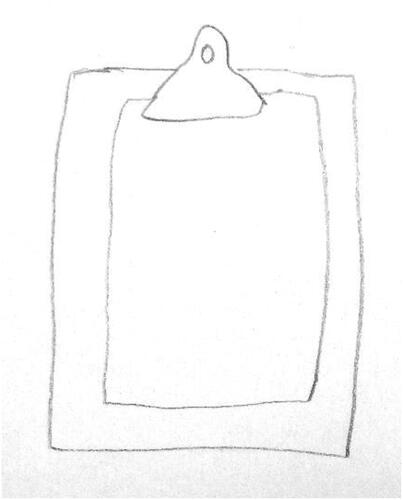

The psychological impact of the attitude from some HCPs was significant. Samantha was made to feel “like I was making it up and it’s all psychological”; while Sharon spoke of her concerns being “brushed aside.” There was speculation that each HCP has a specific remit, beyond which they may not register issues of importance to patients. Hence BTL was simply “not there on the checklist” (). Sandra gave an account of being made to feel “so small, so awful” by her GP for requesting antibiotics to take on holiday abroad, even though this is the recommended precaution against infection for people with lymphoedema. In the authors’ opinion, the GP’s authoritarian stance demonstrates an unwillingness to accept patient knowledge as legitimate and even superior to that of the HCP. Meanwhile, sometimes participants were led to believe that they were to blame for developing BTL.

Figure 2. The clipboard to me represents the fact that I’m not a person in the eyes of so many of the professionals, I’m just a problem and a problem to be fixed medically and anything else that gets in the way of that - me having a personality … - it gets in the way (Samantha). © Samantha (a pseudonym). Reuse not permitted.

While some women felt unable or unwilling to absorb information about potential side-effects, there was an acknowledgment that there would be a point in the treatment pathway when they would feel more receptive. The perceived lack of patient support beyond their treatment for breast cancer was disappointing to women. Nevertheless, a sense of gratitude and an appreciation of the NHS for successfully treating their breast cancer meant that often participants were willing to accept its inadequacies in detecting and treating BTL. In contrast, participants frequently complimented the care and expertise displayed by staff once they were able to access a lymphoedema service. There was a sense, however, that lymphoedema services were not accorded high priority for resources and consequently could be “a bit of a battle” (Sandra) to access.

The theme the silent consequences describes the considerable physical, psychological, and social impact of BTL for some women. It seemed to the authors that participants often chose to remain silent or downplay their symptoms for the protection of themselves or others. Some despaired at having coped with breast cancer, they were now facing an unexpected treatment side-effect. The impact upon women’s lives was often significant with the realization that this was a life-long condition which would require regular management and precautions against infection. For some participants this entailed time-consuming daily massage to drain lymph fluid from the swollen areas, acting as a constant reminder of breast cancer. Thus, developing BTL was perceived as life-changing, in some ways “as much as … if not more than the cancer” (Samantha). Jackie reflected that “the lymphoedema upset me more than anything else … I coped with the cancer … I coped with the treatment … It was the final kick.”

The relatively high profile of arm lymphoedema in existing patient information contributed to the sense of shock at developing BTL; moreover, several participants feared that they would also go on to develop lymphoedema in their arm. In addition, participants felt excluded from being able to wear their preferred clothing, Jackie noting that “you almost feel cheated that you can’t wear nice things.” The compression garments provided to women were often uncomfortable and affected participants’ feelings of femininity. Sharon described her appearance as "totally flat chested … as though I’d been bound;" while Tilly remarked “what’s it come to, I’ve got through cancer, radiotherapy and now I’m reduced to looking like a man.” Leah presented before-and-after photographs displaying an attractive item of lingerie that she had previously enjoyed wearing, next to the rather clinical-looking supportive bra that she was now required to wear ( and ).

The final theme, adapting to breast or trunk lymphoedema, encompasses women’s experiences of developing expertise and an ability to accommodate the condition both practically and psychologically. All participants spoke about the challenge of obtaining suitable bras: frequently they were too tight (particularly for women with trunk or chest wall lymphoedema) or unsupportive (for those who had breast lymphoedema). They described a trial-and-error process of finding bras that were comfortable, supportive, and met their lymphoedema needs as well as their wishes to regain their breast shape or take part in physical activity. Attempting to accommodate fluctuating breast or chest wall swelling often resulted in repeated purchases as bras quickly became ill-fitting. There were stories of women’s success in obtaining well-fitting, supportive, and attractive bras when they were provided with individual attention and support from retail staff, both in chain stores and in specialist shops. However, some participants were disappointed at the lack of knowledge among bra-fitting services.

With specialist support, women developed an understanding of when they needed to employ techniques to drain lymph fluid from their breast, trunk, or chest wall. The demands of self-massage varied between participants, with some needing to set aside 20 to 30 minutes up to two to three times daily. One participant found kinesiology tapingFootnote5 to be effective in reducing swelling around her mastectomy scar. Several participants described ways in which they had reached an acceptable compromise which enabled them to manage their lymphoedema while maintaining their feminine and sexual identity. For instance, Helen, who had been upset at being advised against wearing her usual underwired bras, took the initiative to wear them for special occasions and manage the build-up of lymph fluid afterwards. Women’s attempts to accept BTL was evidenced in their satisfaction at managing the condition and an ability to contrast their own circumstances with others who were perceived to be less fortunate.

Discussion

This study sought to explore women’s experiences of developing and living with BTL after treatment for breast cancer. The language of ‘screaming silences’ provided by The Silences Framework helped to maintain a focus upon the marginalized position of women’s experiences of BTL. The framework encouraged critical thinking by drawing attention to power dynamics within and outside of the research context. Although this was a small study, the process of wider consultation during the cyclical analysis indicated that the findings resonated beyond the research setting.

Within academic and healthcare environments, BTL has failed to receive the same degree of attention and significance as other side-effects; yet it clearly has some negative consequences for women. The prevailing discourses around survival and optimism after cancer treatment cause these alternative experiences to be marginalized and risk silencing women. This was demonstrated in participants’ accounts of disempowering experiences in relation to developing and seeking support for symptoms of BTL. Women not being believed about their bodily symptoms also exemplifies the way in which the medical profession may hold onto their authority over patients by determining what constitutes legitimate knowledge, asserting their expertise over patient experience.Citation16 A perceived lack of investment or political will to explore treatments for lymphoedema is another example of how women felt ignored or dismissed, contributing to their sense of marginalization.Citation17 The findings of this study show that HCPs frequently lacked awareness or understanding of BTL, held inaccurate beliefs and adopted a dismissive or minimizing approach toward patients’ concerns, hindering women’s access to appropriate and timely support. The result for some women was that their symptoms worsened, and they required more complex and lengthy treatment. Moreover, the breast and trunk area as culturally sensitive and intimate areas of the body appeared to influence the willingness of patients and HCPs to investigate symptoms of BTL. During radiotherapy for breast cancer, women are required to be undressed above the waist, their bodies manipulated by therapeutic radiographers to achieve positional accuracy for treatment. The routine nature of breasts being under the clinical gaze resulted in some participants assuming that their breast would be monitored after treatment, which was not always the case.

Women risk further marginalization because generally there is no visible evidence of this condition or its impact. Yet this study found that sometimes there were significant emotional, social, and physical consequences. Women expressed feelings of fear and anxiety prior to obtaining diagnosis; and their experiences of fluctuating and uneven breast size could be experienced as threatening.Citation18 Often the edematous breast was larger than the other one initially; however, it became the smaller one once the swelling subsided because breast tissue had been surgically removed. The repeated purchases of bras to accommodate fluctuating BTL clearly carried financial as well as body image implications. Some spoke of their dismay at being offered a compression vest for BTL which effectively flattens the chest area, indicating the negative effect of this garment upon their feminine and sexual identity.

Like the findings of studies investigating the experiences of women who develop lymphoedema in the arm after treatment for breast cancerCitation19 this study found that information about the risk of BTL was unavailable to women. Nevertheless, there is an important distinction: although patients may not be offered it, information about arm lymphoedema does exist, whereas BTL does not appear to be routinely included in patient literature in the UK. This is relevant as there is evidence that quality of life and levels of anxiety and depression are influenced by the extent to which patients’ information needs are met.Citation20,Citation21 In the present research, none of the participants could recall being told about BTL as a potential side-effect of treatment. This suggests that the treatment pathway fails to address individual patient readiness for and preferred degree of information,Citation22 such that information provision may be limited to a broad reference to lymphedema during the consent to treatment process when patient anxiety is already heightened. Certainly, the findings of one small study (n = 16)Citation22 indicate that there is not a one-size-fits-all to information provision.

The expertise of lymphoedema specialists and their skill in imparting information to patients in an accessible way encouraged participants to make their own decisions about managing their BTL. Sometimes this involved resisting guidance about features of suitable bras and finding a compromise which met women’s emotional as well as their physical needs. However, some participants had difficulty acknowledging bodily changes caused by lymphoedema. Other research suggests that the degree of breast lymphoedema has a negative impact upon body imageCitation23 and distress.Citation24 Moreover, the potential emotional significance of BTL is indicated in the finding of study (n = 350)Citation25 that participants rated the avoidance of severe breast symptoms such as pain and edema higher than a two-year increase in disease-free survival (Relative Importance 18.30, 95% CI 17.38-19.22).

Implications for practice

The findings indicate disempowerment and the marginalization of women caused by inadequate patient information and poor awareness among HCPs about the risk of BTL after treatment for breast cancer. This has several implications for practice. Patients are currently unprepared for the potential development of BTL following treatment for breast cancer. Their readiness to receive information may impact upon their ability to absorb and recall any guidance: several women in this study did not remember being told about lymphoedema (of any type) as a possible side effect of surgery or radiotherapy. Thus, information repeated at different timepoints during the treatment pathwayCitation26 – not just at the time of consent to treatment when patients may be anxious – may improve understanding about side effects such as BTL. A tool for patients to monitor for signs and symptoms of BTLCitation27 would enable patients to gain consistent and personalized information, reduce anxiety and improve communication with HCPs. It could empower women to recognize the signs and seek help, increase HCP understanding and promote faster detection and diagnosis. Similarly, a patient reported outcome measure such as the Breast Edema Questionnaire (BrEQ)Citation28 could be valuable not only as a tool for detection but to assist HCPs to understand the impact of BTL upon women’s daily lives.

A lack of HCP knowledge about BTL and its consequences negatively impacts upon women and the quality of their care and treatment. HCPs should not blame women for developing BTL; there is no consensus about risk factors, and it is unlikely that women can alter those risks.Citation26 Rather, HCPs can support patients by signposting them to resourcesFootnote6 which can raise awareness and support within patients’ social networks. This study found that friends and family were often unaware of the negative physical, emotional, and social consequences of developing and living with BTL. Frequently women appeared stifled by the dominant discourse of positivity around survivorship, compelling them to remain silent about the unexpected challenges of BTL. Such side-effects were not accorded the same significance by others as breast cancer itself.

Through their experiences of BTL, participants developed expertise and adapted to living with the condition, indicating the potential to improve the experiences of other women by incorporating patient knowledge into patient resources. Involving patient advocates in co-design research is an effective way of harnessing this expertise. For instance, women who had radiotherapy for breast cancer were involved in the development of an online resource which is widely used by patients and HCPs in radiotherapy departments in the UK,Citation28 with research funding secured to extend this resource to include information about BTL.

Limitations of the study

The stories of some women are missing from the study findings. No participants from Black or Asian ethnic backgrounds were recruited despite attempts to reach communities through several local and national organizations. This may be due to cultural sensitivities around the research topic.Citation29 Women may also have been excluded if they felt deterred by the invitation to use images.

Conclusion

Women have remained unheard about their experiences of BTL which continues to be a poorly acknowledged condition. From the interviews conducted in this study it emerged that participants were unprepared for the development of BTL and symptoms were often unfamiliar and distressing. Moreover, women’s concerns were frequently ignored or dismissed by HCPs, leading to lengthy delays in obtaining an accurate diagnosis and treatment. For some women, the physical, practical, and emotional impact of BTL was considerable. Developing resources about BTL will equip patients and HCPs with improved awareness and lead to faster detection and management of BTL, improving women’s quality of life after treatment for breast cancer.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (1 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and involvement of Breast Cancer Now in this study, particularly in helping to recruit participants and disseminate the study findings.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The data (anonymised interview transcripts and images) underpinning this study are archived at http://doi.org/10.17032/shu-180039 and for ethical reasons cannot be made available.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Janet Ulman

Dr Janet Ulman qualified as an Occupational Therapist in 1997 and for sixteen years worked in the NHS, predominantly with people who have dementia and their carers. She completed an NIHR-funded MSc in Clinical Research at the University of Sheffield which led her to pursue a research career. Her professional interest in understanding health experiences guided her to undertake a PhD exploring women’s experiences of breast or trunk lymphoedema after treatment for breast cancer under a Vice Chancellor scholarship from Sheffield Hallam University. Alongside a research role in other cancer-related projects, Dr Ulman intends to complete some follow-on research based upon her doctoral study’s recommendations.

Laura Serrant

Professor Laura Serrant has over thirty years’ experience of health care practice, research, policy development, training, and management. Currently she is regional head of Nursing and Midwifery (North East and Yorkshire) for Health Education England. Previous roles include Professor of Nursing at Sheffield Hallam University and Head of Evidence and Strategy in the Nursing Directorate, NHS England. Her research interests relate to health disparities and the needs of marginalized and ‘seldom heard’ communities; and she has developed a theoretical framework for conducting research in this field.Citation1 Professor Serrant’s awards include Queen’s Nurse status and an OBE for services to nursing and health policy.

Margaret Dunham

Dr Margaret Dunham worked in the NHS for 16 years as an adult nurse (RGN) and became a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Pain Management. Her research interests focus upon older people’s experiences of health care, using mainly qualitative methods to gain an understanding of their needs to inform policy and develop age-appropriate assessment methods and innovative support. Dr Dunham works with local and national groups to improve experiences of pain services; and she co-ordinated the update of the National Guidelines for Pain in Older People. She has collaborated with academics and healthcare professionals across the UK, Europe and the US, presenting her work nationally and internationally.

Heidi Probst

Professor Heidi Probst has 14 years prior clinical experience working as a Therapeutic Radiographer in the NHS and over 20 years’ experience in academia as a researcher and lecturer. She leads on the Cancer Management Research cluster, part of the Aging and Long-term conditions research theme in the Centre for Applied Health and Social Care Research (CARe) at Sheffield Hallam University. She is also the Director of the Health Research Institute. Her main research area is radiotherapy for patients diagnosed with breast cancer. Currently she is the Principal Investigator for two breast cancer studies (The SuPPORT 4 All projectFootnote7, and The Respire project www.respire.org.uk)

Notes

1 Where ‘trunk’ denotes areas of the upper body including the chest, armpit, back and shoulderCitation5.

2 IRAS project ID 225878

3 See document entitled ‘Use of the Voice-Centred Relational Method to develop individual themes’

4 ATLAS.ti Version 8.4.20

5 A treatment designed to lift the skin away from the underlying tissues, thereby promoting the flow of lymph fluidCitation15.

6 The Lymphoedema Support Network has produced an educational book for people who have lymphoedema entitled Your lymphoedema: taking back control (published in 2022; ISBN 978-1-3999-2883-0) which includes detailed practical and emotional advice and self-management information.

7 The patient experience of radiotherapy for breast cancer: A qualitative investigation as part of the SuPPORT 4 All study H. Probst, K. Rosbottom, H. Crank, A. Stanton and H. Reed Radiography (Lond) 2021 Vol. 27 Issue 2 Pages 352-359 Accession Number: 33036914 PMCID: PMC8063584 DOI: 10.1016/j.radi.2020.09.011

References

- Serrant-Green L. The sound of ‘silence’: a framework for researching sensitive issues or marginalised perspectives in health. J Res Nurs. 2011;16(4):347–360. doi:10.1177/1744987110387741

- Gilligan C, Eddy J. Listening as a path to psychological discovery: an introduction to the Listening Guide. Perspect Med Educ. 2017;6(2):76–81. Harvard University Press: Cambridge. doi:10.1007/s40037-017-0335-3

- Balmer C, Griffiths F, Dunn J. A ‘new normal’: exploring the disruption of a poor prognostic cancer diagnosis using interviews and participant-produced photographs. Health (London, England: 1997). 2015;19(5):451–472. doi:10.1177/1363459314554319

- Porroche-Escudero A. The ‘invisible scars’ of breast cancer treatments. Anthropol Today. 2014;30(3):18–21. doi:10.1111/1467-8322.12111

- Lymphoedema Support Network. 2019. Lymphoedema of the Breast and Trunk. (Revised June 2019).

- Verbelen H, Tjalma W, Dombrecht D, Gebruers N. Breast edema, from diagnosis to treatment: state of the art. Arch Physiother. 2021;11(1):8. doi:10.1186/s40945-021-00103-4

- Gupta SS, Mayrovitz HN. The breast edema enigma: features, diagnosis, treatment, and recommendations. Cureus, 2022;14(4):1–8. doi:10.7759/cureus.23797

- Verbelen H, Gebruers N, Beyers T, De Monie A-C, Tjalma W. Breast edema in breast cancer patients following breast-conserving surgery and radiotherapy: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;147(3):463–471. doi:10.1007/s10549-014-3110-8

- Barnett GC, Wilkinson JS, Moody AM, et al. The Cambridge breast intensity-modulated radiotherapy trial: patient- and treatment-related factors that influence late toxicity. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol(Great Britain)). 2011;23(10):662–673. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2011.04.011

- Brunt AM, Haviland JS, Wheatley DA, et al. Hypofractionated breast radiotherapy for 1 week versus 3 weeks (FAST-Forward): 5-year efficacy and late normal tissue effects results from a multicentre, non- inferiority, randomised, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2020;395(10237):1613–1626. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30932-6

- Fu MR, Guth AA, Cleland CM, et al. The effects of symptomatic seroma on lymphedema symptoms following breast cancer treatment. Lymphology. 2011;44(3):134–143. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22165584/

- Cancer Research UK. 2021. September 28. Breast cancer incidence (invasive) statistics: Breast cancer incidence by sex and UK country. Breast cancer incidence (invasive) statistics | Cancer Research UK. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/breast-cancer/incidence-invasive#heading-Zero

- Brown LM, Gilligan C. 1992. Meeting at the Crossroads: Women’s Psychology and Girls’ Development. Harvard University Press.

- Nortvedt P, Hem MH, Skirbekk H. The ethics of care: role obligations and moderate partiality in health care. Nurs Ethics. 2011;18(2):192–200. doi:10.1177/0969733010388926

- Finnerty S, Thomason S, Woods M. Audit of the use of kinesiology tape for breast oedema. J Lymphoedema. 2010;5(1):38–44. lymphodemaaudit.pdf (theratape.com). https://theratape.com/education-center/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/lymphodemaaudit.pdf

- Cheek J. Negotiating delicately: conversations about health. Health Soc Care Commun. 1997;5(1):23–27. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.1997.tb00093.x

- Ridner SH, Bonner CM, Deng J, Sinclair VG. Voices from the shadows: living with lymphedema. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35(1):E18–26. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e31821404c0

- Nash M. Breasted experiences in pregnancy: an examination through photographs. Vis Stud. 2014;29(1):40–53. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2014.862992

- Burckhardt M, Belzner M, Berg A, Fleischer S. Living with breast cancer- related lymphedema: a synthesis of qualitative research. Oncoly Nurs Forum. 2014;41(4):E220-37. doi:10.1188/14.ONF.E220-E237

- Faller H, Koch U, Brähler E, et al. Satisfaction with information and unmet information needs in men and women with cancer. J Cancer Surviv: Res Pract. 2016;10(1):62–70. doi:10.1007/s11764-015-0451-1

- Husson O, Mols F, van de Poll-Franse LV. The relation between information provision and health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(4):761–772. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq413

- Honnor A. The information needs of patients with therapy-related lymphoedema. Cancer Nurs Pract. 2009;8(7):21–26. doi:10.7748/cnp2009.09.8.7.21.c7257

- Adriaenssens N, Verbelen H, Lievens P, Lamote J. Lymphedema of the operated and irradiated breast in breast cancer patients following breast conserving surgery and radiotherapy. Lymphology. 2012;45(4):154–164.

- Degnim AC, Miller J, Hoskin TL, et al. A prospective study of breast lymphedema: frequency, symptoms, and quality of life. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(3):915–922. doi:10.1007/s10549-012-2004-x

- Kool M, van der Sijp JRM, Kroep JR, et al. Importance of patient reported outcome measures versus clinical outcomes for breast cancer patients evaluation on quality of care. Breast. 2016;27:62–68. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2016.02.015

- Aunan ST, Wallgren GC, Saetre Hansen B. Breast cancer survivors’ experiences of dealing with information during and after adjuvant treatment: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(15–16):3012–3020. doi:10.1111/jocn.14700

- Probst H, Rosbottom K, Crank H, Stanton A, Reed H. The patient experience of radiotherapy for breast cancer: a qualitative investigation as part of the SuPPORT 4 All study. Radiography. 2021;27(2):352–359. doi:10.1016/j.radi.2020.09.011

- Probst H, Barry J, Clough H, et al. Resource to prepare patients for deep inspiration breath hold: the RESPIRE project. Radiography. 2020;26:S10. doi:10.1016/j.radi.2019.11.027

- Bedi M, Devins GM. Cultural considerations for South Asian women with breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv: Res Pract. 2016;10(1):31–50. doi:10.1007/s11764-015-0449-8