Abstract

Problem identification

Anxiety and depression are more prevalent in hematological cancer patients who experience unpredictable illness trajectories and aggressive treatments compared to solid tumor patients. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions targeted at blood cancer patients is relatively unknown. This systematic review examined trials of physical health and psychosocial interventions intending to improve levels of anxiety, depression, and/or quality of life in adults with hematological cancers.

Literature search

PubMed and CINAHL databases were used to perform a systematic review of literature using PRISMA guidelines.

Data evaluation/synthesis

Twenty-nine randomized controlled trials of 3232 participants were included. Thirteen studies were physical therapy, nine psychological, five complementary, one nutritional and one spiritual therapy interventions. Improvements were found in all therapy types except nutritional therapy.

Conclusions

Interventions that included personal contact with clinicians were more likely to be effective in improving mental health than those without.

Implications for psychosocial oncology

Various psychosocial interventions can be offered but interactive components appear crucial for generating long-standing improvements in quality of life, anxiety and depression.

Background

In the United Kingdom 40,000 people are diagnosed with blood cancer each year and 250,000 are currently living with blood cancer. Promisingly, the survival rates for many types of blood cancer have increased substantially over the past decade: leukemia and myeloma five-year survival rates are over 50%, Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is 65.9% and Hodgkin’s lymphoma is 82.3%.Citation39 However, despite these increases in survival, the blood cancer patient pathway is frequently challenging, with treatment regimens for hematological malignancies often lengthy, aggressive, and an unpredictable illness trajectory compared to solid tumors,Citation2 with related widespread physical and psychological repercussions for patients.Citation53

The psychological and social burden of a cancer diagnosis is considerable and can lead to patients experiencing higher levels of anxiety and depression than the general population.Citation31 Occasionally, emotional and psychological distress following a cancer diagnosis can lead to outcomes such as suicide or cardiovascular fatalitiesCitation25 and the presence of depression and anxiety can adversely affect cancer treatment, recovery and survival outcomes.Citation56 A number of studies have reported the prevalence of anxiety and depression of blood cancer patients as being higher than in patients with other forms of cancer.Citation1,Citation18,Citation28,Citation35 Depression and anxiety may be greater in blood cancer patients due to the uncertainty they face from living with a non-solid tumor.Citation53 It may also be due to the significant impact on their quality of life. A systematic review of the impact of hematological malignancies on quality of life, identified deterioration in many areas of patients’ lives including physical, psychological, social and even cognitive functioning.Citation5

Hematological cancer patients often undergo chemotherapy treatment, which requires patient to isolate. Not only are physical and mental wellbeing impacted by chemotherapy itself, but the experience of isolation also negatively impacts the quality of life, with patients often feeling lonely.Citation54 Yet, a recent study identified considerable variation in the psychosocial support that patients receive and less than half of professionals agreed that their patients’ psychosocial wellbeing were well supported.Citation13 Moreover, 85% of doctors and 40% of nurses stated they had no received training in the assessment and management of psychological needs of blood cancer patients.Citation13

Multiple meta-analyses and literature reviews have focused on the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in reducing anxiety and depression and increasing quality of life in cancer patients. Barsevick et al.Citation9 systematically reviewed 36 studies and concluded that psychoeducational interventions, including behavioral therapy, reduced depression in cancer patients. Similarly, a meta-analysis of 37 published controlled outcome studies conducted by Rehse and PukropCitation43 found that psychosocial interventions of at least 12 wk in length improved the quality of life of cancer patients. However, these studies included in these reviews either solely focused on patients with solid tumors or the majority of the study sample population were patients with solid tumors. Bryant et al.Citation15 conducted a review on the psychosocial outcomes of individuals with hematological cancers, aiming to understand the proportion of measurement, descriptive and intervention study designs conducted in this area, as well as their efficacy in improving anxiety and depression. Few studies found improvements in psychosocial outcomes in blood cancer patients, with only five of the included studies being classed as randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and the methodological quality of these studies was described as variable.Citation15

Thus, despite widespread evidence of the positive benefits of psychosocial interventions in enhancing mental health and health-related quality of life in cancer patients with solid tumors, there remains a paucity of evidence relating to the effectiveness of these psychosocial interventions targeted specifically at blood cancer patients. From the differences in prognosis and treatment for hematological malignancies compared to solid tumors, it is logical to expect that the psychosocial impact will also vary, and therefore it is important to ascertain which interventions improve the well-being of blood cancer patients.

This systematic review aims to build upon previous reviews on this topic, with an updated literature search for RCTs. It also has a broader scope as the definition of psychological outcomes has been extended to include measures of health-related quality of life. Thus, the aim of this paper is to report on a systematic review of RCTs of physical health and psychosocial interventions that aimed to improve levels of anxiety, depression, and health-related quality of life in adults with blood cancer.

Methods

The systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist.Citation37 The protocol for this systematic review was registered on PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=209492) in November 2020.

Procedure

The search strategy was limited to human studies published in peer reviewed journals between the years 2000 – 2021 that were written in the English Language. Systematic searches of PubMed and CINAHL were undertaken between June 2020 and December 2021. The keywords and index terms in were used to search for relevant studies. The reference lists of all studies included in the review were also checked for relevant studies, as well as any related systematic reviews and literature reviews in this area. Grey literature was included in the search strategy but did not yield any results.

Table 1. Keywords and index terms used in systematic search of literature.

Eligibility

To be eligible for inclusion in the review, specific criteria were outlined. Studies needed to have utilized an RCT design. To be eligible for inclusion in the review, specific criteria were outlined. Studies needed to have utilized an RCT design. This review chose to only include RCT studies because this study design is the gold standard for testing the efficacy of interventions, as it reduces the bias inherently present in other study designs. This was a key consideration when designing this systematic review, as a previous review by Bryant et al.Citation15 included a variety of study designs and thus the papers included varied in quality and limited the conclusions that could be drawn. Study primary and/or secondary outcome measures included anxiety, depression or health related quality of life (HRQoL). Participants were aged 18 years or over and studies were only included if the majority of the study population sampled (>66%) had a diagnosis of blood cancer. Additionally, all included RCTs tested the effectiveness of a psychosocial intervention for blood cancer patients implemented in any setting. In accordance with previous reviewsCitation15,Citation50 a psychosocial intervention was considered an intervention that was designed to lead to psychological change or behavioral change. Studies that combined any psychosocial intervention with pharmacological or physical treatments were included. There were no restrictions on blood cancer stage or type of treatment undertaken.

Study selection

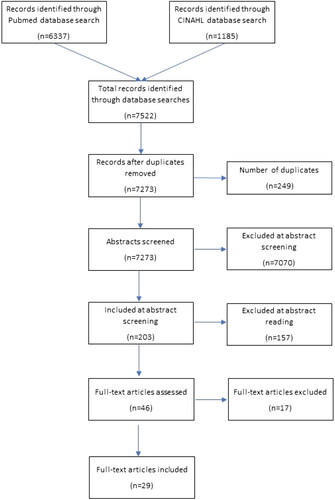

Once the database searches were completed, duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts of identified citations were screened for eligibility according to the predefined Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Context, Outcome (PICCO) criteria listed below (). The remaining full text papers were collated and screened for inclusion. Three reviewers undertook the screening process to ensure that a rigorous and comprehensive process was adhered to. Any discrepancies relating to whether a paper should be included in the review were discussed by the reviewers (VA, AF, MA, PD, FW). If no agreement could be achieved, then this was discussed at team meetings by the entire team until consensus was reached.

Table 2. PICCO Criteria for included studies.

Data extraction

Data were independently extracted from each included paper by two authors (VA, AF, JB, MA and FW), utilizing a data extraction form developed from a Cochrane Collaboration template.Citation34 Any discrepancies in the data extraction process were resolved by a third researcher. The following information was systematically extracted from all the included articles: study authors, date of publication, study population and participant characteristics (sample size, age, gender, country of origin, type of cancer, study methodology, setting and duration), method of outcome measurement, study outcomes and results. Where possible, data on experimental conditions, including the number of study arms, name and description of intervention(s) and comparator(s) groups were also extracted.

Quality appraisal

The quality of the included studies and the risk of bias were independently assessed by at least two authors, using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials.Citation21

Data analysis

Due to heterogeneity of the studies included in the review, meta-analysis was not conducted. However, all data were analyzed thematically to generate a descriptive and narrative synthesis.Citation41 For the purposes of the analysis, the included studies’ data was split into primary and secondary outcome measures and then further funneled into categories by intervention type: physical therapy interventions (e.g. Endurance training), complementary therapy interventions (e.g. Art Therapy, Hypnotherapy), psychological therapy interventions (e.g. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy), nutritional therapy interventions (e.g. Personalized nutrition programme) and spiritual therapy interventions (e.g. Spiritual Care).

Results

Included studies

The database searches returned 7522 articles to be assessed for eligibility. A total of 249 duplicates were removed, leaving 7273 for inclusion. After screening the titles and abstracts of these studies, 7070 were deemed to not meet the eligibility criteria for the review, leaving 203 abstracts remaining. On further inspection of the abstracts, an additional 157 were excluded. 46 of these remaining papers were reviewed by two authors. Upon examination, 17 studies were deemed to not meet the inclusion criteria. The main reasons for papers being excluded at the full text screening stage were as follows: wrong study design (n = 10); using the same study data as other included papers (n = 3); over one third of participants not being blood cancer patients (n = 1); not having access to the full text paper (n = 2); and not being explicit about the outcome measures used (n = 1). Therefore, twenty-nine studies were included in this review ().

Study characteristics

All included papers were published between 2000 and 2021. 44% of the studies identified were physical therapy interventions designed to reduce anxiety, depression and/or HRQoL. Furthermore, 17% of included studies were complementary therapy interventions, 31% psychological therapy interventions, 4% nutritional therapy interventions and 4% spiritual therapy interventions. A total of 10 studies investigated the efficacy of psychosocial interventions on supporting individuals manage various aspects of undergoing or recovering from receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplants. In total, 3232 participants were recruited to the studies, with a wide range of blood cancers, including multiple myeloma, B-cell lymphoma, T-cell lymphoma, acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 74 years, with a mean age of 50.5 years and 43.8% were women. Studies were conducted in many continents including Europe, Australasia, North America and Asia. provides an overview of the characteristics of included studies.

Table 3. Characteristics of randomized control trials included in the systematic review.

Quality of included studies

All included studies were RCTs and were deemed to be of adequate to good quality according to the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Checklist.Citation21 The risk of bias of studies included in the review is summarized in . The nature of the interventions included meant that participants could not be blinded to experimental or control arms meaning performance bias was unavoidable. Similarly, participant attrition was prominent in many studies; it is unclear whether this was directly related to the interventions under study or other confounders. Although selection bias was not evident, some studies included more male participants. Reporting bias appeared low.

Table 4. Risk of bias for studies included in this systematic review.

Review findings

The identified RCT studies were grouped into the following categories based on the content of the intervention: physical therapy (n = 13), psychological therapy (n = 9), complementary therapies (n = 5), nutritional therapy (n = 1) and spiritual therapy (n = 1). Types of physical therapy intervention ranged from endurance training to mixed modality exercise programs, with some programs implemented independently at home whilst others were supervised by healthcare professionals, and one used a combination of supervised and unsupervised training. The length of the physical therapy interventions studied ranged from one day to 36 wk. Studies were categorized as psychological interventions if they included known psychological therapies such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), or core components of psychological therapies such as psychoeducation about anxiety and depression, developing problem-solving skills to help individuals cope with symptoms and the challenges they experience. Counseling or peer support programs that were designed to reduce anxiety, depression, distress and improve HRQoL were also included in this category. These therapies varied in format, including face-to-face and/or virtual sessions, and duration the varied from weeks to months. The RCT studies identified as complementary therapy interventions included art therapy (n = 1), hypnosis (n = 1), music (n = 1), mindfulness (n = 1) as well as Tibetan yoga, which incorporated mindfulness (n = 1). Only one RCT investigated nutritional therapy. This study compared the effect of individualized nutritional support to usual diet on the HRQoL of patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.Citation45 Similarly, this review identified one RCT study of an intervention consisting of a planned spiritual care program designed to improve depression, anxiety and stress scores in blood cancer patients.Citation38

Description of study outcomes

Health-related quality of life outcomes

Of the twenty-nine studies included in this review, twenty-six included a HRQoL measure.Citation3,Citation4,Citation6,Citation8,Citation10,Citation14,Citation15,Citation17,Citation19,Citation20,Citation22,Citation23,Citation24,Citation26,Citation30,Citation32,Citation33,Citation36,Citation44,Citation45,Citation46,Citation48,Citation49,Citation51,Citation52,Citation55 The outcome measures of HRQoL varied from direct measures, with the EORTC QLQ-C30 the most commonly used,Citation3,Citation4,Citation8,Citation10,Citation17,Citation24,Citation30,Citation32,Citation33,Citation44,Citation45,Citation48,Citation51,Citation52 to other measures indicating of HRQoL improvements, such as coping with pain, fatigue, quality of sleep and psychological adjustment.Citation6,Citation15,Citation19,Citation20,Citation22,Citation23,Citation36,Citation46,Citation49,Citation55 Many of the HRQoL measures were specifically developed for assessing these outcomes in cancer patients, for example the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy, and were therefore considered to be psychometrically strong.

Fifteen studies found significant improvements in HRQoL post-intervention. Of these studies, six were exercise interventions.Citation17,Citation20,Citation26,Citation30,Citation48,Citation52 These exercise interventions varied in formats with two studies, with two studiesCitation17,Citation30 examining physical therapy programs implemented independently at home, whereas the other four assessed the efficacy of supervised training.Citation20,Citation26,Citation48,Citation52 Seven studies that found significant HRQoL improvements were psychological therapy interventions.Citation6,Citation22,Citation23,Citation24,Citation33,Citation44,Citation49 The psychological therapies also differed in structure and content. One RCT investigated a face-to-face palliative care intervention focusing on the management of physical and psychological symptoms,Citation24 whereas another two RCTs focused on the efficacy of problem-solving training to improve psychosocial outcomes.Citation6,Citation49 Three RCTs investigated CBT interventions, delivered by a therapist either via telephoneCitation23 or in a virtual setting,Citation33 or as a self-directed internet-based program.Citation22 A fourth RCT investigated the efficacy of a novel program combining trauma-focused CBT and psychotherapy, delivered face-to-face.Citation44 The two complementary therapies were similar, with one RCT studying the efficacy of a mindfulness intervention to improve psychosocial outcomesCitation55 and the other of a Tibetan yoga intervention, which also incorporated mindfulness.Citation19

Anxiety and depression outcomes

Twenty-two studies measured changes in patients’ anxiety and/or depression scores.Citation3,Citation4,Citation6–8,Citation14,Citation15,Citation19,Citation20,Citation22,Citation23,Citation24,Citation26,Citation32,Citation36,Citation38,Citation44,Citation46,Citation47,Citation49,Citation52,Citation55 These studies also varied in the tools used to measure anxiety and depression, including the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,Citation4,Citation7,Citation26,Citation32,Citation52 the Visual Analogue Scales,Citation46 the Montgomery-Âsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS),Citation8 the short-form (SF) Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale, the SF Spielberger State Anxiety InventoryCitation20 and the PROMIS short form measures of anxiety and depression.Citation15 The measures used to assess changes in individuals’ anxiety and depression were considered to be psychometrically adequate, though it is acknowledged that there is a lack of literature specifically assessing these outcome measures in blood cancer patients.Citation57

Twelve studies found significant improvements in anxiety and/or depression post-intervention. Three were physical exercise interventions and all were supervised.Citation20,Citation26,Citation52 Four psychological therapies were found to significantly improve anxiety and/or depression.Citation6,Citation7,Citation23,Citation24 Similar to the psychological therapies that were shown to improve HRQoLCitation6,Citation7,Citation22,Citation23,Citation24,Citation44,Citation49 also utilized telephone counseling as well as health education and psychological guidance as part of their intervention designed to improve psychosocial outcomes in acute myeloid leukemia patients. Four complementary therapies were found to improve anxiety and depression: a study examining the effect of hypnosis on anxiety and pain relief prior to bone marrow biopsy,Citation46 an RCT examining the effect of listening to live or prerecorded music on anxiety levels in patients undergoing chemotherapy,Citation14 an RCT assessing the effect of the art therapy on anxiety, depression, and distress in patients undergoing stem cell transplantationCitation36 and a mindfulness intervention.Citation55 Additionally, one spiritual care intervention, which included two major components of supportive presence and support for religious rituals, was also found to be effective in reducing anxiety and depression.Citation38

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of RCTs assessing the effectiveness of physical health and psychosocial interventions on anxiety, depression and quality of life in patients with blood cancer. Nineteen RCTs investigating a range of interventions utilized primary outcomes measures of anxiety, depression or HRQoL. A further 10 RCTs, of which all were physical interventions, investigated these as secondary outcomes.

Six studies that examined supervised or home-based exercise interventionsCitation17,Citation20,Citation26,Citation30,Citation48,Citation52 yielded statistically significant results regarding quality of life, depression and/or anxiety. A common factor between these studies was that participants had contact with hospital or research staff during the study duration.Citation17,Citation20,Citation26,Citation48,Citation52 While Hathiramani et al.Citation30 explored the effects of a home-based exercise intervention, participants had personal interaction with research staff at baseline for advice, instruction, demonstration, and practice. This pattern of personal contact suggests that this element of the intervention is an important factor in their success. A previous review of exercise adherence in cancer patients also found support from coaches was an important predictor of patients’ adherence to exercise interventions.Citation40 Although those interventions aimed to improve physical health through increased engagement, similar findings in the current review potentially suggests that support from professionals is also important for the improvement of blood cancer patients’ mental health.

The findings relating to the effectiveness of complementary therapies in reducing depression and anxiety in blood cancer patients indicate that more research in this area is required. The included studies encompassed complementary therapies including art therapy, yoga, mindfulness, music and hypnosis. Most of these studies reported a significant reduction in anxiety and/or depression when comparing the intervention to usual care. Though different measurement scales were used across studies to measure levels of depression and anxiety, making cross study comparisons difficult, the findings do indicate that a variety of complementary therapies can be offered to blood cancer patients to provide them with psychological support throughout their cancer journey. Similarly, the significant improvements in depression scores in blood cancer patients who received a spiritual care programCitation38 highlights the important role of spiritual therapy in supporting blood cancer patients, something which is identified by other research in this area.Citation11,Citation16,Citation42 However, more studies are needed to investigate the effects of spiritual care interventions on a variety of cultures and populations to make generalizable conclusions regarding their effectiveness.

Of the four studies that investigated the use of CBT in improving blood cancer patients HRQoL and/or anxiety/depressionCitation22,Citation23,Citation33,Citation44 two utilized a virtual setting.Citation22,Citation33 David et al.Citation22 did not find significant changes in anxiety or depression, only an increase in patients “fighting spirit”, whereas Jim et al.Citation33 found significant improvements in HRQoL more broadly. Another study that utilized a survivorship program in a virtual environment also did not find any significant improvement on measures of depression, and only found a reduction in distress in participants who also engaged in additional problem-solving sessions via telephone.Citation49 Online interventions have many advantages, including convenience and ease of access, and their potential has been realized more fully during the recent COVID-19 pandemic. However, participants who took part in the modular format CBT sessionsCitation22 reported limited benefits to the programme and that they would have appreciated the opportunity to share their experiences with other participants. This may suggest that although online and virtual sessions have benefits in terms of accessibility, flexibility, cost-effectiveness and inclusivity, the added value of interacting with others may have more widespread benefits than can be achieved through the sharing of information alone. This corroborates a recent systematic of the use of digital technologies in mental health.Citation12

Despite differences between the interventions included in this systematic review, common themes were identified across all studies. Many psychosocial interventions reported statistically significant improvements in the mean scores of depression, anxiety and health-related quality of life of blood cancer patients when the delivery of these included some form of face-to-face interaction between those delivering the intervention and the participants. This finding was consistent across four of the five psychosocial intervention types, suggesting that the development of an interactive relationship between session facilitators and patients may be an important factor in improving symptom management and HRQoL in blood cancer patients. However, considerations need to be given regarding the cost and feasibility of implementing interactive psychosocial interventions outside of research settings, and further research on the outcomes of interactive relationships in interventions is required.

Clinical implications

This systematic review demonstrates that the majority of studies and types of intervention were found to be effective in reducing anxiety, depression and/or health related QoL. This therefore suggests that hematological cancer patients could have a choice in the type of intervention that they engage in to reduce the psychological burden of their condition. The evidence-based intervention(s) that a patient chooses may depend on their preference and/or their stage of treatment, but with many options available this could make psychosocial support more accessible to this population. Findings from a recent studyCitation27 suggested that people living with blood cancer were at increased risk of depression during COVID-19, due to an increasing sense of isolation. What is more, Harada, Masumoto and KondoCitation29 examined the relationship between exercising alone, exercising with others, and mental health among middle-aged and older adults and discovered that exercising with others had a positive influence on participants’ mental well-being compared to exercising alone. Many psychosocial interventions are currently hosted online, as a way of minimizing unnecessary face-to-face contact during COVID-19. This may result in fewer face-to-face interventions being delivered in the longer term, due to the benefits outlined above, which potentially has implications for blood cancer patients. This review suggests there may be advantages of blood cancer patients maintaining some human interaction with others, as the benefits of the psychosocial interventions may not be purely due to the content delivered within them. Though our findings potentially indicate that the relational aspects of face-to-face interventions are beneficial, many blood cancer patients may not be able to finance or access face-to-face supervised training sessions due to a lack of resource. Therefore, further work is needed to fully understand if and what the benefits of face-to-face interventions are, and how these elements can be incorporated into future online interventions.

Strengths and limitations

To date little systematic evidence has focused on the impact of psychosocial interventions in improving quality of life, anxiety and depression in blood cancer patients. The clearly defined eligibility criteria, search terms and selection strategy in this review yielded a large number of RCTs across many continents, though only two carefully selected databases were searched, which was a study limitation Most studies were of adequate to good quality, adding confidence in the reliability of the findings. However, the heterogeneity amongst the different psychosocial interventions, as well as the time between participants’ cancer diagnoses and their study participation, means that any findings should be interpreted with caution. There were noticeable differences in the intensity, duration and frequency of some of the psychosocial interventions, as well as the way they were delivered, making it difficult to draw true comparisons across studies. Across the included studies, participants received a wide range of treatments and their time since diagnosis was variable, making comparisons across studies limited. A range of scales were also used to measure anxiety, depression, and quality of life across the studies, increasing the heterogeneity of the findings. Greater consensus and consistency on scales used to measure these outcomes in future studies would improve understanding of intervention efficacy.

Conclusions

This systematic review has examined the effectiveness of RCT interventions aimed at improving HRQoL, depression and anxiety for people living with blood cancer. Most studies identified were physical therapy interventions, with some psychological, complementary, nutritional and spiritual therapy interventions. Four of the five intervention types demonstrated improvements in HRQoL, depression and/or anxiety. Future research is required to build on the review findings; however, policy makers and clinicians should consider these findings when deciding which types of psychosocial interventions to recommend to blood cancer patients. Whilst a variety of psychosocial interventions can be recommended to patients depending on their needs, preferences and beliefs an interactive component appears crucial for generating long standing improvements in the HRQoL, anxiety and depression of blood cancer patients.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abuelgasim KA, Ahmed GY, Alqahtani JA, Alayed AM, Alaskar AS, Malik MA. Depression and anxiety in patients with hematological malignancies, prevalence, and associated factors. Saudi Med J. 2016;37(8):877–881. doi:10.15537/smj.2016.8.14597

- Albrecht TA, Rosenzweig M. Management of cancer related distress in patients with a hematological malignancy. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2012;14(7):462–468. doi:10.1097/NJH.0b013e318268d04e

- Alibhai SMH, Durbano S, Breunis H, et al. A phase II exercise randomized controlled trial for patients with acute myeloid leukemia undergoing induction chemotherapy. Leukemia Res. 2015;39(11):1178–1186. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2015.08.012

- Alibhai SMH, O'Neill S, Fisher-Schlombs K, et al. A pilot phase II RCT of a home-based exercise intervention for survivors of AML. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(4):881–889. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-2044-8

- Allart-Vorelli P, Porro B, Baguet F, Michel A, Cousson-Gélie F. Haematological cancer and quality of life: a systematic literature review. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5(4):e305-e305. doi:10.1038/bcj.2015.29

- Balck F, Zschieschang A, Zimmermann A, Ordemann R. A randomized controlled trial of problem-solving training (PST) for hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients: Effects on anxiety, depression, distress, coping and pain. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2019;37(5):541–556. doi:10.1080/07347332.2019.1624673

- Bao H, Chen Y, Li M, Pan L, Zheng X. Intensive patient’s care program reduces anxiety and depression as well as improves overall survival in de novo acute myelocytic leukemia patients who underwent chemotherapy: a randomized, controlled study. Transl Cancer Res. 2019;8(1):212–227. doi:10.21037/tcr.2019.01.32

- Barğı G, Güçlü MB, Arıbaş Z, Akı ŞZ, Sucak GT. Inspiratory muscle training in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients: a randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(2):647–659. doi:10.1007/s00520-015-2825-3

- Barsevick AM, Sweeney C, Haney E, Chung E. A systematic qualitative analysis of psychoeducational interventions for depression in patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29(1):73–85. doi:10.1188/02.ONF.73-87

- Baumann FT, Zopf EM, Nykamp E, et al. Physical activity for patients undergoing an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: benefits of a moderate exercise intervention. Eur J Haematol. 2011;87(2):148–156. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.2011.01640.x

- Bolhari J, Naziri GH, Zamanian S. Spiritual approach to treatment efficacy in reducing depression, anxiety and stress in women with breast cancer. J Woman Soc. 2012;3:85–115.

- Borghouts J, Eikey E, Mark G, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of user engagement with digital mental health interventions: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(3):e24387. doi:10.2196/24387

- Brett J, Henshall C, Dawson P, et al. 2023. Examining the levels of psychological support available to haematological cancer patients in England: a mixed methods study. (Under Review).

- Bro ML, Johansen C, Vuust P, et al. Effects of live music during chemotherapy in lymphoma patients: a randomized, controlled, multi-center trial. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(10):3887–3896. doi:10.1007/s00520-019-04666-8

- Bryant AL, Deal AM, Battaglini CL, et al. The effects of exercise on patient-reported outcomes and performance-based physical function in adults with acute leukemia undergoing induction therapy: exercise and quality of life in acute leukemia (EQUAL). Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17(2):263–270. doi:10.1177/1534735417699881

- Chen J, Lin Y, Yan J, Wu Y, Hu R. The effects of spiritual care on quality of life and spiritual well-being among patients with terminal illness: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2018;32(7):1167–1179. doi:10.1177/0269216318772267

- Chuang TY, Yeh ML, Chung YC. A nurse facilitated mind-body interactive exercise (Chan-Chuang qigong) improves the health status of non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients receiving chemotherapy: Randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;69:25–33. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.004

- Clinton-McHarg T, Carey M, Sanson-Fisher R, Tzelepis F, Bryant J, Williamson A. Anxiety and depression among haematological cancer patients attending treatment centres: prevalence and predictors. J Affect Disord. 2014;165:176–181. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.072

- Cohen L, Warneke C, Fouladi RT, Rodriguez MA, Chaoul-Reich A. Psychological adjustment and sleep quality in a randomized trial of the effects of a Tibetan yoga intervention in patients with lymphoma. Cancer: Interdis Int J Am Cancer Soc. 2004;100(10):2253–2260. doi:10.1002/cncr.20236

- Courneya KS, Sellar CM, Stevinson C, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of aerobic exercise on physical functioning and quality of life in lymphoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(27):4605–4612. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0634

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. 2019. CASP (Randomised Controlled Trials) Checklist [online]. https://casp-uk.net/. Accessed October 2020.

- David N, Schlenker P, Prudlo U, Larbig W. Internet-based program for coping with cancer: a randomized controlled trial with hematologic cancer patients. Psycho-Oncol. 2013;22(5):1064–1072. doi:10.1002/pon.3104

- DuHamel KN, Mosher CE, Winkel G, et al. Randomized clinical trial of telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce post-traumatic stress disorder and distress symptoms after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(23):3754–3761. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.26.8722

- El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc T, VanDusen H, et al. Effect of inpatient palliative care on quality of life 2 weeks after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2094–2103. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.16786

- Fang F, Fall K, Mittleman MA, et al. Suicide and cardiovascular death after a cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(14):1310–1318. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110307

- Furzer BJ, Ackland TR, Wallman KE, et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing the effects of a 12-week supervised exercise versus usual care on outcomes in haematological cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(4):1697–1707. doi:10.1007/s00520-015-2955-7

- Gallagher S, Bennett KM, Roper L. Loneliness and depression in patients with cancer during COVID-19. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2021;39(3):445–451. doi:10.1080/07347332.2020.1853653

- Gheihman G, Zimmermann C, Deckert A, et al. Depression and hopelessness in patients with acute leukemia: the psychological impact of an acute and life-threatening disorder. Psycho-Oncol. 2016;25(8):979–989. doi:10.1002/pon.3940

- Harada K, Masumoto K, Kondo N. Exercising alone or exercising with others and mental health among middle-aged and older adults: longitudinal analysis of cross-lagged and simultaneous effects. J Phys Act Health. 2019;16(7):556–564. doi:10.1123/jpah.2018-0366

- Hathiramani S, Pettengell R, Moir H, Younis A. Relaxation versus exercise for improved quality of life in lymphoma survivors—a randomised controlled trial. J Cancer Surv. 2021;15(3):470–480. doi:10.1007/s11764-020-00941-4

- Jadoon NA, Munir W, Shahzad MA, Choudhry ZS. Assessment of depression and anxiety in adult cancer outpatients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer. 2010;10(1):1–7. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-10-594

- Jarden M, Baadsgaard MT, Hovgaard DJ, Boesen E, Adamsen L. A randomized trial on the effect of a multimodal intervention on physical capacity, functional performance and quality of life in adult patients undergoing allogeneic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43(9):725–737. doi:10.1038/bmt.2009.27

- Jim HS, Hyland KA, Nelson AM, et al. Internet-assisted cognitive behavioral intervention for targeted therapy–related fatigue in chronic myeloid leukemia: results from a pilot randomized trial. Cancer. 2020;126(1):174–180. doi:10.1002/cncr.32521

- Li T, Higgins JPT., Deeks, JJ. (Eds). Chapter 5: Collecting data. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 6.3. Cochrane; 2022.

- Linden W, Vodermaier A, MacKenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(2–3):343–351. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.025

- McCabe C, Roche D, Hegarty F, McCann S. ‘Open Window’: a randomized trial of the effect of new media art using a virtual window on quality of life in patients’ experiencing stem cell transplantation. Psycho-Oncol. 2013;22(2):330–337. doi:10.1002/pon.2093

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Musarezaie A, Moeini M, Taleghani F, Mehrabi T. Does spiritual care program affect levels of depression in patients with Leukemia? A randomized clinical trial. J Edu Health Promo. 2014;3:96.

- Office for National Statistics. Cancer Survival in England: Adult, Stage at Diagnosis and Childhood – Patients Followed up to 2018. United Kingdom. Office for National Statistics; 2019.

- Ormel HL, Van der Schoot GGF, Sluiter WJ, Jalving M, Gietema JA, Walenkamp AME. Predictors of adherence to exercise interventions during and after cancer treatment: a systematic review. Psycho-Oncol. 2018;27(3):713–724. doi:10.1002/pon.4612

- Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Product ESRC Methods Programme. Version 1; 2006:b92.

- Rajagopal D, Mackenzie E, Bailey C, Lavizzo-Mourey R. The effectiveness of a spiritually-based intervention to alleviate subsyndromal anxiety and minor depression among older adults. J Relig Health. 2002;41(2):153–166. doi:10.1023/A:1015854226937

- Rehse B, Pukrop R. Effects of psychosocial interventions on quality of life in adult cancer patients: meta analysis of 37 published controlled outcome studies. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50(2):179–186. doi:10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00149-0

- Rodin G, Malfitano C, Rydall A, et al. Emotion and symptom-focused engagement (ease): a randomized phase II trial of an integrated psychological and palliative care intervention for patients with acute leukemia. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(1):163–176. doi:10.1007/s00520-019-04723-2

- Skaarud KJ, Hjermstad MJ, Bye A, et al. Effects of individualized nutrition after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation following myeloablative conditioning; a randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018;28:59–66. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2018.08.002

- Snow A, Dorfman D, Warbet R, et al. A randomized trial of hypnosis for relief of pain and anxiety in adult cancer patients undergoing bone marrow procedures. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30(3):281–293. doi:10.1080/07347332.2012.664261

- Stevenson W, Bryant J, Watson R, et al. A multi-center randomized controlled trial to reduce unmet needs, depression, and anxiety among hematological cancer patients and their support persons. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2020;38(3):272–292. doi:10.1080/07347332.2019.1692991

- Streckmann F, Kneis S, Leifert JA, et al. Exercise program improves therapy-related side-effects and quality of life in lymphoma patients undergoing therapy. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(2):493–499. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdt568

- Syrjala KL, Yi JC, Artherholt SB, et al. An online randomized controlled trial, with or without problem-solving treatment, for long-term cancer survivors after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12(4):560–570. doi:10.1007/s11764-018-0693-9

- Teo I, Krishnan A, Lee GL. Psychosocial interventions for advanced cancer patients: a systematic review. Psycho-Oncol. 2019;28(7):1394–1407. doi:10.1002/pon.5103

- Wehrle A, Kneis S, Dickhuth HH, Gollhofer A, Bertz H. Endurance and resistance training in patients with acute leukemia undergoing induction chemotherapy—a randomized pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(3):1071–1079. doi:10.1007/s00520-018-4396-6

- Wiskemann J, Dreger P, Schwerdtfeger R, et al. Effects of a partly self-administered exercise program before, during, and after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood, J Am Soc Hematol. 2011;117(9):2604–2613. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-09-306308

- Yang SY, Park SK, Kang HR, Kim HL, Lee EK, Kwon SH. Haematological cancer versus solid tumour end-of-life care: a longitudinal data analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020. 29 Dec 2020. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002453

- You WY, Yeh TP, Lee KC, Ma WF. A preliminary study of the comfort in patients with leukemia staying in a positive pressure isolation room. IJERPH. 2020;17(10):3655. doi:10.3390/ijerph17103655

- Zhang R, Yin J, Zhou Y. Effects of mindfulness-based psychological care on mood and sleep of leukemia patients in chemotherapy. Int J Nurs Sci. 2017;4(4):357–361. doi:10.1016/j.ijnss.2017.07.001

- Zhu J, Fang F, Sjölander A, Fall K, Adami HO, Valdimarsdóttir U. First-onset mental disorders after cancer diagnosis and cancer-specific mortality: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(8):1964–1969. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdx265

- Ziegler L, Hill K, Neilly L, et al. Identifying psychological distress at key stages of the cancer illness trajectory: a systematic review of validated self-report measures. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(3):619–636. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.06.024