Abstract

Purpose

To summarize and critique research on the experiences and outcomes of sexual minority women (SMW) treated with surgery for breast cancer through systematic literature review.

Methods

A comprehensive literature search identified studies from the last 20 years addressing surgical experiences and outcomes of SMW breast cancer survivors. Authors performed a quality assessment and thematic content analysis to identify emergent themes.

Results

The search yielded 121 records; eight qualitative studies were included in the final critical appraisal. Quality scores for included studies ranged 6-8 out of 10. Experiences and outcomes of SMW breast cancer survivors were organized by major themes: 1) Individual, 2) Interpersonal, 3) Healthcare System, and 4) Sociocultural and Discursive.

Conclusions

SMW breast cancer survivors have unique experiences of treatment access, decision-making, and quality of life in survivorship. SMW breast cancer survivors’ personal values, preferences, and support network are critical considerations for researchers and clinicians.

Problem identification

In 2023, approximately 297,790 US women will be diagnosed with invasive breast cancer.Citation1 Approximately 6.4% of U.S. women identify as sexual or gender minority (SGM; including gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and other sexual and gender minority identities and experiences).Citation2 Though cancer incidence and prevalence is unknown for SGM people, extrapolation from the general population equates to over 15,000 SGM individuals diagnosed with invasive breast cancer in the U.S. in 2023.Citation3 However, despite calls from national organizations for systematic sexual orientation and gender identity data collection,Citation4,Citation5 this information is not routinely collected in health research or clinical health records, perpetuating invisibility of SGM people in research and clinical care.Citation5–7

Evidence is emerging that sexual minority women (SMW) face unique challenges throughout the cancer care continuum and do not receive care that adequately meets their needs.Citation8,Citation9 Starting before diagnosis, disparities for SMW have been identified in breast cancer risk and screening. Lesbian and bisexual women have a higher prevalence of breast cancer risk factors including nulliparity, obesity, alcohol use, and smoking. SMW are also less likely to have health insurance coverage, a recent pelvic examination, or mammogram.Citation10–12 Studies show Black SMW have even higher delays in breast care than white SMW, reporting intersectional stigma (i.e. stigma for Black and sexual minority identities) and lower social support.Citation13,Citation14 SGM people with breast cancer may have worse cancer-specific outcomes, including delayed diagnosis, faster cancer recurrence, increased likelihood of declining oncologist-recommended treatment modality, and age-adjusted risk for fatal breast cancer.Citation15,Citation16 While quality of life and psychological adjustment appear similar in SGM breast cancer survivors and cisgender, heterosexual survivors,Citation17–20 there remain unmet support needs for SGM breast cancer survivors.Citation21,Citation22

Treatment phase is another point for oncology clinicians to consider patients’ values, preferences, and lifestyle when discussing care. Treatment recommendations should follow national guidelines,Citation23 but many women have options requiring decision points, such as mastectomy vs. breast conserving surgery with radiation, or whether they wish to have reconstructive surgery.Citation24 There is evidence that in the general population of breast cancer patients, there is incongruence between patients and surgeons with regards to priorities and goals of breast reconstruction.Citation25 In SGM women specifically, there is evidence that assumptions and heteronormative, cisgender biases permeate the treatment discussion and recommendation process by clinicians, and by cancer surgeons specifically.Citation26,Citation27 The potential disconnect between patients and oncology clinicians related to values, preferences, and lifestyle can lead to dissatisfaction with care (such as exclusion of social support and lack of provision of relevant health information) and poor clinical outcomes including treatment side effects (i.e. arm morbidity, systemic side effects) and sexual health.Citation28–30

SMW report systemic barriers to obtaining safe and affirming healthcare, including lack of culturally competent care, fear of discrimination, experiences of homophobia, and lack of health and support information specific to the needs of SMW.Citation8,Citation31 These experiences lead many SMW to feel isolated and invisible during one of the most vulnerable times in their lives.Citation8 The purpose of this review was to summarize and critically appraise contemporary studies reporting breast cancer surgery outcomes and experiences of SMW patients. While quantitative studies speak to the prevalence of different surgery options (breast-conserving surgery vs. mastectomy),Citation30 our focus was gaining a better understanding of SMW survivors’ clinical and quality of life outcomes in order to identify important targets for tailored intervention. We utilize the Sexual & Gender Minority Health Disparities Framework, an adaptation of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Framework,Citation32 to examine the multi-level factors impacting the breast cancer surgical experiences and outcomes of SMW. The SGM Health Disparities Framework is an ecological model that highlights how individual, interpersonal, and community and societal factors can create SGM-specific health disparities.Citation32

Literature search

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included if: (1) participants had been diagnosed with breast cancer; (2) participants identified as members of the SGM community; (3) one or more of the following were reported: experiences, preferences, or needs related to breast cancer care or surgical treatment decision-making, as well as interactions with healthcare clinicians and support persons; (4) they used qualitative methodology; (5) were published in English; and (6) published in 2000 or later. The time frame was chosen to capture a wider breadth of studies, including those with more contemporary sociocultural contexts.

Search strategy

Selected databases included PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and LGBT Life with Full Text (EBSCO). Key search subjects included the following: (1) sexual and gender minority women or transgender men; (2) breast or chest cancer; (3) treatment, mastectomy, or reconstruction; (4) treatment experience or navigation or satisfaction (for specific search terms, see Supplemental Online Resource 1). Literature searches were initially conducted on July 14, 2021 and repeated/updated on February 22, 2023; all searches were limited to English and January 2000 to February 2023.

Study selection

Search results from each database were imported into Covidence® and duplicates were removed. The remaining articles were screened by title and abstract, then full-text articles were retrieved and reviewed against inclusion/exclusion criteria, all conducted by three reviewers (EA, ER, and JKS). Details of the systematic review plan were submitted to PROSPERO (CRD42021224205) on December 2, 2020.

Quality appraisal

All included studies were assessed for quality using Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research ().Citation33 Full quality assessment tools with authors’ scores can be found in Supplemental Online Resource 2. Using this tool, three reviewers (EA, ER, and JKS) independently appraised each study and then discussed and reconciled any discrepancies.

Table 1. Summary table describing studies included in the review.

Thematic analysis

A paired review group (EA, ER, CL; two authors per manuscript) independently identified themes and sub-themes from included manuscripts. Subsequent themes were inductively developed, reviewed by the group, and refined. Authors reviewed the refined themes, discussed thematic relevance and organization, and reached consensus on primary themes, sub-themes and cross-cutting concepts. Previously published methodology for qualitative data analysis guided this approach.Citation34

Data evaluation/synthesis

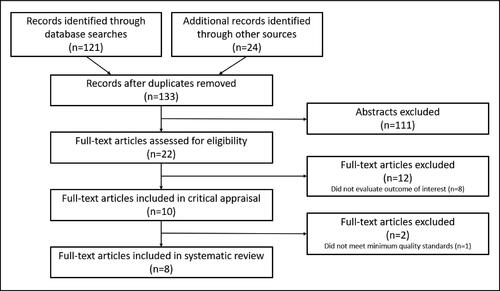

The literature search yielded 121 records, and an additional 24 were identified through manuscript reference list review (). After removal of duplicates, 133 records were screened for eligibility. Eight studies (6%) reporting breast cancer surgery outcomes and experiences of SMW patients met our eligibility criteria and were included in the systematic review (). Quality assessment scores for included studies ranged 6-8 (possible range 0-10).

All eight manuscripts reported results of qualitative studies performed in the U.S. and Canada, with data collected through focus groups, interviews, and online support group posts. Study samples included lesbians, transgender, gender non-conforming, bisexual women, women who partner with women, and sexual and gender diverse individuals who may have used multiple terms to describe their sexual orientation and gender identity (). Though our literature search included both sexual and gender minority identifiers, five studies had exclusively lesbian or cisgender sexual minority participants, two had a mix of sexual and gender minority participants and one dealt exclusively with gender minority participants. When referring to included studies throughout the systematic review, specific study samples are described in a manner consistent with the original cited source. Additional demographic information for the samples is presented in .

Table 2. SGM survivor characteristics of reviewed papers within the scoping review.

Experiences and outcomes of SMW breast cancer survivors were organized by major themes based on the Sexual & Gender Minority Health Disparities FrameworkCitation32 to illustrate the complex and layered experience of SMW breast survivors. These were 1) Individual, 2) Interpersonal, 3) Healthcare System (Community), and 4) Sociocultural and Discursive (Societal). Subthemes were explored for each major theme ().

Table 3. Major themes and subthemes for SMW breast cancer survivors’ experiences.

Individual

Though study participants describe a range of experiences, values, and opinions, there were common considerations for how cancer diagnosis and treatment affect their body appearance and function as well as self-image, identity, and gender.

Appearance and function

SMW (lesbian, bisexual, and women who partner with women) who chose reconstruction after surgery reported that they considered symmetry, avoiding uncomfortable prostheses, feeling ‘whole’, and looking ‘normal’.Citation35 They suggested their choice to appear to have a ‘normal’ looking feminine chest would help with avoiding depression after cancer surgery. Similarly, SMW survivors explained how a reconstructed feminine chest appearance can be ‘passing’ as normal and healthy, helping them to ‘pass’ as not ill, not a cancer patient, and cover up physical effects of cancer.

SMW considered how others would view their body form after cancer treatment to varying extents. Participants described pressures from cisgender societal norms to have reconstructed breasts.Citation35–37 These pressures also came specifically from their surgeons, who often failed to present any options other than reconstruction after mastectomy, framing reconstruction as the natural next step after mastectomy.Citation37 Some sexual minority patients said they were concerned about being mistaken for transgender or transitioning, which was not how they identified and also increased their risk of experiencing transphobia.Citation35,Citation36,Citation38

Sexual minority breast cancer patients often had a strong focus on body health and physical functioning of the chest, for both strength and intimacy. Many SMW believed that body strength and physical function were more important than having breasts,Citation35 and they did not want breast reconstruction to get in the way of their activities,Citation36 or to worry about implants, or additional surgeries or complications.Citation37

In a study of SMW’s breast surgery decision-making, those who did not have reconstruction generally had no regrets and still felt desirable, attractive, and “freed”.Citation35 Those who chose reconstruction more often talked about discomfort or pain, numbness, limited range of motion, and scar tissue. Women who chose reconstruction had mixed opinions with regards to their satisfaction with the outcome, such that some expressed doubts and regrets about their decision, while others were happy with the cosmetic outcome.Citation35

One common experience of those with reconstruction was the perception that they were not well-prepared regarding potential for complications, limited esthetic results, and physical limitations after reconstruction.Citation35,Citation39 Many SMW prioritized sensation over appearance and considered loss of breast and nipple sensitivity when deciding on treatment options.Citation35,Citation36 For some survivors, loss of breast/nipple sensation from mastectomy along with other cancer treatment effects, such as hair loss, diminished libido, and vulvovaginal dryness, combined to negatively impact their sexual response and satisfaction.Citation40 This extended to concerns about their partners’ sexual arousability in response to their lack of breasts.

Self-image, identity, and gender

Many SMW patients in the studies reviewed suggested that they felt more prepared to reject the desirable feminine form construct, as they had already refused to accept prevailing hegemonic views of heteronormative and cisgender womanhood.Citation37 Lesbian patients suggested that not being defined by their breasts was aligned with identifying as a lesbian.Citation35,Citation36,Citation39 Others agreed that being part of a queer community may have facilitated their ability to challenge mainstream beauty ideals, ‘‘play’’ with gender (e.g. deciding to wear prostheses or not), and separate having or not having breasts from one’s personal gender identity.Citation37

Narratives from studies included in this systematic review suggest gender influenced treatment choices, including the choice to reconstruct after breast surgery. Patients reported some intersection of personal feelings about breast surgery with or without reconstruction and gender-affirming surgery (top surgery).Citation41 Many SMW patients who chose to forgo reconstruction, particularly those who identified as genderqueer, felt their new flat chest was affirming to their gender fluidity and flexibility to ‘wear boobs’ or not.Citation40,Citation41

Interpersonal

Relationships with partners, family (including chosen family), and larger social networks influence personal experiences of the body, gender identity, and how SMW individuals navigate treatment decision making and adjust to treatment outcomes.

Partners and dating

Studies included in this systematic review suggested partners have an influence on treatment decision-making. In a study of SMW and their support people, Boehmer et al. found differences in congruence of values and shared decision-making for those who chose reconstruction compared to those who chose esthetic flat closure.Citation35 For SMW who chose reconstruction, partners were often more passive in the decision-making process and appeared to have more doubts after reconstruction than partners of SMW who opted to forgo reconstruction. Partners of SMW who had reconstruction recognized when the survivor had regrets due to breast mound changes in appearance, feel (contour, weight, density), and sensation. SMW who chose esthetic flat closure more often had partners who echoed their satisfaction and affirmed their attractiveness regardless of breast status. For SMW without a partner, some opted for reconstruction with the thought of how future partners might view them in mind. Alternatively, other SMW without partners reported that going flat felt protective from ‘the objectifying male gaze’, and served to screen out potential partners who value breasts and feminine appearance too highly.Citation35

Social support

When reporting social support related to breast cancer experiences, some studies report social isolation and fragile care networks related to stigma and biases faced by those in the SMW community.Citation38,Citation41 Many individuals reported experiencing barriers to accessing affirming support, including acquiring cancer-related knowledge and coping resources. SMW patients often turned to the SMW community to find support that is affirming to their sexual orientation. Some participants felt the SMW social context was more supportive of breastlessness and of all body types (i.e. size, shapes, and gender expressions).Citation36 At the same time, some reported interacting with SMW individuals who were less understanding of a desire to reconstruct, assuming that because they were a member of the SMW community that they would not want breast mounds/reconstruction.Citation37

SMW breast cancer patients report challenges with finding relevant breast cancer specific knowledge and support through community and healthcare connections. Breast cancer support groups of cisgender and heterosexual women were not a good fit for several SMW patients.Citation40 Many said their needs went unmet and they often reported being uncomfortable ‘coming out’.Citation37,Citation39 Many study participants suggested their diagnosis and treatment experiences were very different and perceived it as irrelevant to hear about others’ experiences with husbands and children, and an emphasis on being attractive to (cisgender and heterosexual) men. They felt there was a strong emphasis on appearance, and much less on physical limitations and functioning, which were more distressing to them.Citation40 Patients also reported a lack of culturally relevant cancer information and resources online, especially for transgender and gender non-conforming patients.Citation41

Healthcare system

SMW in the included studies reported biased experiences within the healthcare system at the surgeon and institutional level. These experiences ranged from microaggressions to overt bias, to blatant discrimination.

Surgeon level

Study participants generally wanted to play an active role in their own care and decision-making, but some felt discouraged by their surgeon’s cisgender and heteronormative presentation of surgical options.Citation14,Citation37 SMW breast cancer patients reported feeling disempowered after experiences with surgeons who presented breast reconstruction as the natural progression in treatment.Citation36–38 Study participants felt they needed to justify why they were opting out of surgery, but reasons for opting in were viewed as self-evident.Citation37 Some reported having to fight to have their surgeon accept their esthetic flat closure decision, with some surgeons enlisting help of family members/partners and mental health professionals to convince the patient to have reconstruction.Citation38 Several SMW patients were so overwhelmed by the process, they chose to go along with the surgeon’s recommendations, regardless of a hesitancy to reconstruct.Citation35,Citation39 Both outright discrimination and surgeon discomfort with providing culturally competent care to SGM survivors led many to experience emotional distress and question their safety and the trust they placed in their surgeons to provide quality cancer care.Citation14,Citation38,Citation41

Conversely, some SMW patients were satisfied with their care because the cancer surgery was successful in removing their cancer, and they had positive healthcare clinician interactions. This was exemplified in a focus group study of lesbian and heterosexual women’s experiences by Matthews et al.Citation39 Like their heterosexual counterparts, SMW patients valued shared decision-making, respect, attention, and time provided by the oncology physicians, and were dissatisfied with those who were rushed or condescending. In a study of Black SMW, participants described positive interactions with a variety of oncology and primary care clinicians with whom they shared at least one characteristic (e.g. race, ethnicity, sexual orientation).Citation14 They felt like their clinicians had an understanding of their needs and were accepting of their intersectional identities.

A common theme across studies was the experience of cisgender and heteronormative assumptions built into cancer treatment plans and anticipated treatment outcomes. Participants felt that surgeons and other oncology clinicians needed training on meeting the needs of SMW patients and that their care was disorienting and uncoordinated .Citation40 Gender-affirming care was rarely considered by oncology clinicians, despite potential conflict of these treatments (e.g. hormone therapy, mastectomy scar location, or chest reconstruction options). Lastly, the two specialties, oncology and gender-affirming care, were ‘in silos’ with no coordination or sharing of knowledge, which made decision-making difficult for transgender patients.Citation41

Institutional level

Institutional-level subthemes included accessing care that feels safe and inclusive, treatment goals standardized for cisgender and heterosexual women, and poor coordination of care and services. One key aspect of access to affirming care and the safety of SMW breast cancer patients is whether or not they disclose their sexual orientation to healthcare workers. SMW breast cancer patients reported continually assessing whether it was safe to ‘come out,’ and how being ‘out’ might affect their care.Citation38 Participants reported needing to come ‘out’ repeatedly to many members of the healthcare team as they progressed through their care. Participants who were not ‘out’ reported feeling like they were betraying themselves and their partner and reported feeling invisible or erased from the community of survivors.

Participants described a process of discernment regarding whether they felt safe, respected, and affirmed with individual clinicians and within healthcare environments. In some cases, participants reported obvious displays of homophobia and transphobia that were compounded by racism in SGM people of color.Citation14,Citation38 Some altered their appearance or behavior, or chose not to bring their partner to appointments to avoid discrimination.Citation41 Others simply felt like a number more than a person in a crowded waiting room or overbooked clinic schedule.Citation14 If clinicians and care environments were not able to support participants’ autonomy, self-care competence, and human relatedness, survivors often felt alienation for themselves and their partners during a very vulnerable time.Citation14

Sociocultural and Discursive

Sociocultural and discursive subthemes included politics of gender and breast cancer subculture.

Politics of gender

Participants report experiencing ‘gender policing’, with others in general society imposing their opinions of what SMW patients’ gender expression should be. Several SMW patients felt deciding to forgo reconstructed breasts was an empowering decision. Some felt comfortable expressing this as a socio-political decision, while others felt marked as oppositional or trying to make a political statement, when they were making a very personal decision.Citation37 Participants described feeling caught in a Catch-22: if they opted for no reconstruction they were seen by general society as a desexualized woman, but if they chose reconstruction they were seen as buying into women’s objectification.Citation37 Patients said that living up to the image of ‘breastless warrior’, like survivors seen posing topless proudly without breasts in media, is not as easy as pictures look and can make some feel inadequate.Citation37

Culture of breast cancer survivors

Sociopolitical influences exist within the breast cancer community, and may be felt by both SMW and cisgender, heterosexual women. SMW patients commented on the ‘pinkwashing’ of breast cancer culture, covering clinical, commercial, and media products with the color symbolizing femininity, and often sponsored by fashion and cosmetic industries.Citation37,Citation40 Some participants perceived that breast cancer is portrayed as a cosmetic crisis, rather than a health crisis, which one patient found “a convenient way to displace sheer terror”.Citation37 A focus on cosmetics and fashion can be distracting from important underlying problems, like social and employment discrimination based on a cancer diagnosis. For example, one participant related that it was more difficult to ‘come out’ to a prospective employer about a cancer status than to ‘come out’ about their sexual orientation.Citation37 Many SMW patients felt they needed to hide their cancer diagnosis from employers for fear of discrimination, including lost career opportunities.

Feelings of exclusion created by pink-washing the breast cancer experience was especially poignant for transgender and gender non-conforming patients.Citation41 SMW with breast cancer often still identify under the umbrella of ‘women’s cancers’, however, transgender and gender non-conforming patients may not identify as women and are again rendered invisible in cancer programs intended for ‘women’s health’.

Conclusions

This systematic review summarized and critically appraised contemporary studies of breast cancer surgery outcomes and experiences of SMW survivors. While the general needs and outcomes of SMW are similar to heterosexual women, SMW experience them through a cultural lens informed by their lived experiences.Citation31 Our findings largely reflect what is seen in contemporary literature describing oncology healthcare experiences of SGM individuals.Citation27,Citation42 This study has several key themes and subthemes reflecting multi-level impacts of patients’ outcomes and perceptions, and can inform clinical, research, and policy approaches to improving health equity.

At each ecological level, themes presented are drivers of decision-making and may be considered by oncology clinicians in a culturally responsive, shared medical decision-making model.Citation38,Citation41,Citation43 On the individual level, clinical decisions were based on a wide variety of factors, often balancing external pressures with being true to oneself. Important clinical outcomes affect both heterosexual and SMW, including breast and nipple function, vaginal health and sexual function, body image changes, psychological health (e.g. coping and resilience), and overall self-rated health.Citation11,Citation28,Citation44 The impact of these outcomes post-treatment may be different for many SMW, and therefore a more culturally sensitive and tailored approach is warranted.Citation28 Clinicians may reassess their approach with some periodicity as individual’s sexuality and gender identification may be fluid over time and their needs may change.Citation45,Citation46 Most study participants included in this systematic review are described as cisgender SMW (), and thus it is imperative to further research gender diverse breast cancer survivor clinical needs, values, and preferences.

On an interpersonal level, clinicians would do well to understand the makeup and involvement of SMW breast cancer survivors’ support networks.Citation21,Citation47 Social support networks often provide unpaid practical, emotional, and decision-making support to survivors.Citation48,Citation49 There is clear evidence that social support leads to improved outcomes in cancer survivors,Citation50 and this is especially relevant for SGM people who are at higher risk for social vulnerability factors.Citation51 SMW breast cancer survivors may experience distress in clinical settings through discrimination, discomfort disclosing sexual orientation or relationship with their support person, and lack of culturally appropriate support services.Citation14,Citation21,Citation52 Additional research is needed to explore the social support needs of SGM breast cancer survivors, and how addressing those needs improves clinical outcomes.

In the clinical setting, open communication with oncology clinicians, including breast cancer and reconstructive surgeons, and informed decision-making were challenges for many SMW breast cancer survivors. Many clinicians, particularly breast surgeons, think of breast reconstruction as a biomedical inevitability and patient norm and have not considered gender and sexual identity as integral to the decision-making process.Citation36–38,Citation40,Citation41 Current breast cancer treatment decision support tools were developed based on (presumably) cisgender and heterosexual patients’ opinions and preferences.Citation25,Citation53 Future studies should confirm whether these tools are valid and reliable in SMW patients and adapt them appropriately.

Healthcare systems could make meaningful changes to the care delivery environment to make clinical spaces more welcoming and affirming to SGM folks.Citation54,Citation55 Distrust in the healthcare system has been linked to poor breast cancer outcomes, including use of breast cancer screening, genetic testing and counseling, and adjuvant treatment.Citation56–59 This has been shown to be critical for SMW and particularly for Black SMW.Citation60 It is vital that clinicians ask about sexual orientation and gender identity and document it appropriately, and then be mindful of how individual’s identity may impact their decision-making, support system, and cancer care. While others have pointed to lack of clinician knowledge or relevant support resources when describing SMW unmet survivorship needs,Citation61–63 this review shows that many surgeons lack cultural sensitivity to SGM patients preferences and values in the context of reconstruction decision making.

Limitations

The literature reviewed has several limitations that should be considered when drawing conclusions and informing future research and practice. Most study participants were white, well-educated, and self-identified as lesbian, thus limiting generalizability. A major deficit in the current knowledge of SGM breast/chest cancer experiences and outcomes is the lack of diversity in gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and other intersectional social determinants of health that amplify the cancer disparities of SMW like many of those included in these studies. Diverse SGM survivors are less likely to participate in research due to medical and research mistrust very much based in historical atrocities, and it is the responsibility of clinicians and researchers to work diligently to earn the trust of vulnerable communities.Citation64–67

Included studies had small sample sizes with minimal geographic/rural distribution, with participants from Boston, New York City, Chicago, the San Francisco Bay Area, Canada (specifically urban, suburban, and rural locations in the Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and Nova Scotia), and those recruited though social media/national recruitment. Only one study included support people to describe experiences and outcomes of SMW breast cancer patients,Citation35 and none included the clinician or surgeon perspective.

Implications for psychosocial oncology

There are several implications for research and practice based on results of this systematic review. At each level of the SGM Health Disparities Framework, clinicians and researchers have an opportunity to intervene to improve the quality, safety, and relevance of breast cancer care for SMW.

Results indicated that SMW breast cancer patients feel largely invisible and misunderstood as they navigate a cisgender and heteronormative clinical, social support, and survivorship system.

The studies suggest oncology clinicians could improve shared treatment decision-making by reviewing individual preferences, values, and family/social support networks.

More research is warranted to describe the breast cancer experiences of SGM people with particular attention to diversity of gender, relationship status, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and other factors of social vulnerability.

This systematic review found that SMW breast cancer patients have unique experiences of healthcare access, decision-making, and quality of life in survivorship. Thus, researchers and clinicians must consider SMW breast cancer patients’ personal values and preferences for treatment, as well as their support network. Culturally responsive healthcare clinician interactions are critical for reducing health disparities in cancer care access and quality of life outcomes for this underserved and understudied population.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the review conception and design. Literature search and Covidence® management were performed by Emily Ridgway. Title, abstract, and full text screening and manuscript quality assessments were performed by Elizabeth Arthur, Emily Ridgway, and Jessica Krok Schoen. Thematic analysis was performed by Elizabeth Arthur, Emily Ridgway, and Clara Lee. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Elizabeth Arthur and Emily Ridgway, and all authors made substantive comments and revisions to subsequent versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, et al. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(1):17–48. doi:10.3322/caac.21763

- Jones JM. LGBT identification rises to 5.6% in latest U.S. estimate. Gallup News Service. 2021; p. N.PAG-N.PAG. https://news.gallup.com/poll/329708/lgbt-identification-rises-latest-estimate.aspx. Accessed: August 22, 2021.

- National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. Cancer Stat Facts: Female Breast Cancer 2022. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. Accessed November 28, 2022.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Electronic Health Record Incentive Program-Stage 3 and Modifications to Meaningful Use in 2015 Through 2017, H. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Editor. 2015. p. 62761–62955.

- Griggs J, Maingi S, Blinder V, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Position Statement: strategies for reducing cancer health disparities among sexual and gender minority populations. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(19):2203–2208. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.72.0441

- Cahill S, Singal R, Grasso C, et al. Do ask, do tell: high levels of acceptability by patients of routine collection of sexual orientation and gender identity data in four diverse American community health centers. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107104. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0107104

- National Academies of Sciences, E., and Medicine. Understanding the Well-Being of LGBTQI + Populations. Washington, DC: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Washington, DC; 2020.

- Lisy K, Peters MDJ, Schofield P, et al. Experiences and unmet needs of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people with cancer care: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. Psychooncology. 2018;27(6):1480–1489. doi:10.1002/pon.4674

- Margolies L, Brown CG. Current state of knowledge about cancer in lesbians, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2018;34(1):3–11. doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2017.11.003

- Cochran SD, Mays VM, Bowen D, et al. Cancer-related risk indicators and preventive screening behaviors among lesbians and bisexual women. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(4):591–597.

- Hutchcraft ML, Teferra AA, Montemorano L, et al. Differences in health-related quality of life and health behaviors among lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual women surviving cancer from the 2013 to 2018 National Health Interview Survey. LGBT Health. 2021;8(1):68–78. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2020.0185

- Hart SL, Bowen DJ. Sexual orientation and intentions to obtain breast cancer screening. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009;18(2):177–185. doi:10.1089/jwh.2007.0447

- Poteat TC, Adams MA, Malone J, et al. Delays in breast cancer care by race and sexual orientation: results from a national survey with diverse women in the United States. Cancer. 2021;127(19):3514–3522. doi:10.1002/cncr.33629

- Greene N, Malone J, Adams MA, et al. “This is some mess right here”: exploring interactions between Black sexual minority women and health care providers for breast cancer screening and care. Cancer. 2020;127(1):74–81. doi:10.1002/cncr.33219

- Eckhert E, Lansinger O, Liu M, et al. A case-control study of healthcare disparities in sex and gender minority patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16_suppl):6517–6517. doi:10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.6517

- Cochran SD, Mays VM. Risk of breast cancer mortality among women cohabiting with same sex partners: findings from the National Health Interview Survey, 1997-2003. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2012;21(5):528–533. doi:10.1089/jwh.2011.3134

- Boehmer U, Glickman M, Winter M. Anxiety and depression in breast cancer survivors of different sexual orientations. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(3):382–395. doi:10.1037/a0027494

- Boehmer U, Glickman M, Milton J, et al. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer survivors of different sexual orientations. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(2):225–236. doi:10.1007/s11136-011-9947-y

- Bazzi AR, Clark MA, Winter MR, et al. Resilience among breast cancer survivors of different sexual orientations. LGBT Health. 2018;5(5):295–302. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2018.0019

- Boehmer U, Stokes JE, Bazzi AR, et al. Dyadic quality of life among heterosexual and sexual minority breast cancer survivors and their caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(6):2769–2778. doi:10.1007/s00520-019-05148-7

- Paul LB, Pitagora D, Brown B, et al. Support needs and resources of sexual minority women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2014;23(5):578–584. doi:10.1002/pon.3451

- Brown MT, McElroy JA. Unmet support needs of sexual and gender minority breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(4):1189–1196. doi:10.1007/s00520-017-3941-z

- Gradishar WJ, Anderson BO, Abraham J, et al. Breast Cancer, Version 3.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(4):452–478. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2020.0016

- Offodile AC, 2nd, Lee CN-H. Future directions for breast reconstruction on the 20th anniversary of the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(7):605–606. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.0397

- Lee CN, Hultman CS, Sepucha K. Do patients and providers agree about the most important facts and goals for breast reconstruction decisions? Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64(5):563–566. doi:10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181c01279

- Sledge P. From decision to incision: Ideologies of gender in surgical cancer care. Soc Sci Med. 2019;239:112550. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112550

- Alpert AB, et al. I’m not putting on that floral gown: enforcement and resistance of gender expectations for transgender people with cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(10):2552–2558.

- Boehmer U, Ozonoff A, Timm A, et al. After breast cancer: sexual functioning of sexual minority survivors. J Sex Res. 2014;51(6):681–689. doi:10.1080/00224499.2013.772087

- Arena PL, Carver CS, Antoni MH, et al. Psychosocial responses to treatment for breast cancer among lesbian and heterosexual women. Women Health. 2006;44(2):81–102. doi:10.1300/j013v44n02_05

- Boehmer U, Glickman M, Winter M, et al. Long-term breast cancer survivors’ symptoms and morbidity: differences by sexual orientation? J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(2):203–210. doi:10.1007/s11764-012-0260-8

- Hill G, Holborn C. Sexual minority experiences of cancer care: a systematic review. Journal of Cancer Policy. 2015;6:11–22. doi:10.1016/j.jcpo.2015.08.005

- Sexual & Gender Minority Research Office. Sexual & Gender Minority Health Disparities Research Framework (Adapted from the NIMHD Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Framework). National Institutes of Health Sexual & Gender Minority Research Office; 2021.

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Tools for Use in JBI Systematic Reviews: Checklist for Qualitative Research. J.B. Institute, Editor. 2017.

- Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, et al. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(1):45–53. doi:10.1177/135581960501000110

- Boehmer U, Linde R, Freund KM. Breast reconstruction following mastectomy for breast cancer: the decisions of sexual minority women. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(2):464–472. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000246402.79334.3b

- Wandrey R, Qualls W, Mosack K. Rejection of breast reconstruction among lesbian breast cancer patients. LGBT Health. 2016;3(1):74–78. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0091

- Rubin LR, Tanenbaum M. “Does that make me a woman?”: Breast cancer, mastectomy, and breast reconstruction decisions among sexual minority women. Psychol Women Q. 2011;35(3):401–414. doi:10.1177/0361684310395606

- Bryson MK, Taylor ET, Boschman L, et al. Awkward choreographies from cancer’s margins: incommensurabilities of biographical and biomedical knowledge in sexual and/or gender minority cancer patients’ treatment. J Med Humanit. 2018;41(3):341–361. doi:10.1007/s10912-018-9542-0

- Matthews AK, Peterman AH, Delaney P, et al. A qualitative exploration of the experiences of lesbian and heterosexual patients with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29(10):1455–1462. doi:10.1188/02.ONF.1455-1462. https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/NIH-SGM-Health-Disparities-Research-Framework-FINAL_508c.pdf. Accessed Feb 2, 2023.

- Brown MT, McElroy JA. Sexual and gender minority breast cancer patients choosing bilateral mastectomy without reconstruction: “I now have a body that fits me”. Women Health. 2018;58(4):403–418. doi:10.1080/03630242.2017.1310169. https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Systematic_Reviews2017_0.pdf. Accessed Feb 7, 2020.

- Taylor ET, Bryson MK. Cancer’s Margins: Trans* and gender nonconforming people’s access to knowledge, experiences of cancer health, and decision-making. LGBT Health. 2016;3(1):79–89. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0096

- Kamen CS, Alpert A, Margolies L, et al. “Treat us with dignity”: a qualitative study of the experiences and recommendations of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(7):2525–2532. doi:10.1007/s00520-018-4535-0

- Grabinski VF, Myckatyn TM, Lee CN, et al. Importance of shared decision-making for vulnerable populations: examples from postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Health Equity. 2018;2(1):234–238. doi:10.1089/heq.2018.0020

- Pratt-Chapman ML, Alpert AB, Castillo DA. Health outcomes of sexual and gender minorities after cancer: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):183. doi:10.1186/s13643-021-01707-4

- Diamond LM. Sexual fluidity in male and females. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2016;8(4):249–256. doi:10.1007/s11930-016-0092-z

- Mittleman J. Sexual fluidity: implications for population research. Demography. 2023;60(4):1257–1282. doi:10.1215/00703370-10898916

- Boehmer U, Stokes JE, Bazzi AR, et al. Dyadic stress of breast cancer survivors and their caregivers: are there differences by sexual orientation? Psychooncology. 2018;27(10):2389–2397. doi:10.1002/pon.4836

- Arora NK, Finney Rutten LJ, Gustafson DH, et al. Perceived helpfulness and impact of social support provided by family, friends, and health care providers to women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2007;16(5):474–486. doi:10.1002/pon.1084

- Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, et al. Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer. 2016;122(13):1987–1995. doi:10.1002/cncr.29939

- Kroenke CH, Kubzansky LD, Schernhammer ES, et al. Social networks, social support, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(7):1105–1111. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2846

- James SE, et al. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016.

- Thompson T, Heiden-Rootes K, Joseph M, et al. The support that partners or caregivers provide sexual minority women who have cancer: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2020;261:113214. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113214

- Berlin NL, Tandon VJ, Hawley ST, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of decision aids to improve decision making for postmastectomy breast reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Decis Making. 2018;39(1):5–20. doi:10.1177/0272989X18803879

- Arthur E, Glissmeyer G, Scout S, et al. Cancer equity and affirming care: an overview of disparities and practical approaches for the care of transgender, gender-nonconforming, and nonbinary people. CJON. 2021;25(5):25–35. doi:10.1188/21.CJON.S1.25-35

- Quinn GP, Alpert AB, Sutter M, et al. What oncologists should know about treating sexual and gender minority patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol Oncology Practice. 2020;16(6):309–316. doi:10.1200/OP.20.00036

- Mouslim MC, Johnson RM, Dean LT. Healthcare system distrust and the breast cancer continuum of care. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;180(1):33–44. doi:10.1007/s10549-020-05538-0

- Bickell NA, Weidmann J, Fei K, et al. Underuse of breast cancer adjuvant treatment: patient knowledge, beliefs, and medical mistrust. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(31):5160–5167. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.22.9773

- Sheppard VB, Mays D, LaVeist T, et al. Medical mistrust influences black women’s level of engagement in BRCA 1/2 genetic counseling and testing. J Natl Med Assoc. 2013;105(1):17–22. doi:10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30081-x

- Dean LT, Moss SL, McCarthy AM, et al. Healthcare system distrust, physician trust, and patient discordance with adjuvant breast cancer treatment recommendations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(12):1745–1752. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0479

- Dean LT, Greene N, Adams MA, et al. Beyond Black and White: race and sexual identity as contributors to healthcare system distrust after breast cancer screening among US women. Psychooncology. 2021;30(7):1145–1150. doi:10.1002/pon.5670

- Webster R, Drury-Smith H. How can we meet the support needs of LGBT cancer patients in oncology? A systematic review. Radiography (Lond). 2021;27(2):633–644. doi:10.1016/j.radi.2020.07.009

- Seay J, Mitteldorf D, Yankie A, et al. Survivorship care needs among LGBT cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2018;36(4):393–405. doi:10.1080/07347332.2018.1447528

- Quinn GP, Schabath MB, Sanchez JA, et al. The importance of disclosure: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, queer/questioning, and intersex individuals and the cancer continuum. Cancer. 2015;121(8):1160–1163. doi:10.1002/cncr.29203

- Brenick A, Romano K, Kegler C, et al. Understanding the influence of stigma and medical mistrust on engagement in routine healthcare among Black Women who have sex with women. LGBT Health. 2017;4(1):4–10. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2016.0083

- Hostetter M, Klein S. Understanding and Ameliorating Medical Mistrust among Black Americans, in Transforming Care. Commonwealth Fund; 2021. https://doi.org/10.26099/9grt-2b21. Jan 14, 2021.

- Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, et al. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):879–897. doi:10.1353/hpu.0.0323

- Underhill K, Morrow KM, Colleran C, et al. A qualitative study of medical mistrust, perceived discrimination, and risk behavior disclosure to clinicians by U.S. male sex workers and other men who have sex with men: implications for biomedical HIV prevention. J Urban Health. 2015;92(4):667–686. doi:10.1007/s11524-015-9961-4

- Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, Sutton SK, et al. Cancer and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) populations. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(5):384–400. doi:10.3322/caac.21288

- Gordon JR, Baik SH, Schwartz KTG, et al. Comparing the mental health of sexual minority and heterosexual cancer survivors: a systematic review. LGBT Health. 2019;6(6):271–288. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2018.0204

- Williams AD, Bleicher RJ, Ciocca RM. Breast cancer risk, screening, and prevalence among sexual minority women: an analysis of the National Health Interview Survey. LGBT Health. 2020;7(2):109–118. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2019.0274

- Malone J, Snguon S, Dean LT, et al. Breast cancer screening and care among black sexual minority women: a scoping review of the literature from 1990 to 2017. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28(12):1650–1660. doi:10.1089/jwh.2018.7127

- Zaritsky E, Dibble SL. Risk factors for reproductive and breast cancers among older lesbians. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19(1):125–131. doi:10.1089/jwh.2008.1094