On November 2, 2016, Theresa Jarnagin Enos unexpectedly passed away at her home in Tucson, Arizona, leaving behind a trailblazing legacy of work in writing, teaching, scholarly editing, (wo)mentoring, administration, and service. An important figure in contemporary rhetoric and composition studies, Theresa—a self-proclaimed “maverick”—founded this journal, Rhetoric Review, on her own in 1982 due to the lack of publication venues for research concerning the history and theory of rhetoric. As the first peer-reviewed journal in rhetoric and composition studies, Theresa worked tirelessly to make Rhetoric Review the journal we know today—publishing manuscripts from the field’s superstars (Jim W. Corder, Frank D’Angelo, and Michael Halloran were among the first contributors in the inaugural issue), establishing an editorial board, soliciting peer reviewers, editing each manuscript scrupulously, advertising for new subscribers, all while printing issue copies and mailing them off to institutions herself. In 1987, Theresa was recruited by the University of Arizona where she helped establish its PhD program in Rhetoric, Composition, and the Teaching of English (RCTE). During her twenty-seven year tenure at the University of Arizona, Theresa taught undergraduate and graduate courses, served as associate composition director, program director of RCTE and, of course, maintained her editorship of Rhetoric Review. Theresa authored, edited, or co-edited over ten books including A Sourcebook for Basic Writing Teachers, Writing Program Administrator’s Resource, The Encyclopedia of Rhetoric and Composition, Gender Roles and Faculty Lives in Rhetoric and Composition, The Promise and Perils of Writing Program Administration, Defining the New Rhetorics, Living Rhetoric and Composition, Beyond PostProcess and Postmodernism: Essays on the Spaciousness of Rhetoric, in addition to numerous articles and chapters. The entries from colleagues and former students included in this Burkean Parlor allow us just a brief glimpse of Theresa’s influence on the lives and careers of so many of us in our discipline; how fortunate we are to have known her and to have learned from her.

ELISE VERZOSA HURLEY

Illinois State University

______________________

For over half a century—both as a student and as a professor—I have been involved in rhetoric. Over this period, I have had the opportunity to see our discipline grow and prosper to the point that it is (once again) an established part of higher education in America. In my opinion this dramatic transformation in higher education began with, and came about because of, the hard work, courage, and vision of twenty-five to thirty of our colleagues: One of them was Theresa Jarnagin Enos. I say this not only because of how Theresa brought her journal, Rhetoric Review, into national prominence, but also because of all that she did as a teacher, scholar, and leader. I say these things as an eyewitness because from 1985 to the present, I have had the honor of being on the Editorial Board of Rhetoric Review and from this position I was able to watch, for decades, how tirelessly Theresa worked for her students, her colleagues, and for our field. It goes without saying that she will be missed, but it also goes without saying that as long as we have historians of rhetoric, she will never be forgotten. We are so proud that she is an alumna of our program here at Texas Christian University.

RICHARD LEO ENOS

Texas Christian University

PETER ELBOW

University of Massachusetts Amherst

______________________

As anyone lucky enough to be published in Theresa Enos’s Rhetoric Review knows—and RR was hers from its birth to her death—she was an attentive editor and a terrifically meticulous proofreader. It might surprise those who didn’t know her well, however, that she was also, for lack of a better term, an expressivist. As she writes in “Road Rhetoric,” in her first year of doctoral study she was converted to rhetoric by her reading of Peter Elbow’s Writing without Teachers (Enos, Theresa Jarnagin. “Road Rhetoric: Recollecting, Recomposing, Remaneuvering.” Renewing Rhetoric’s Relation to Composition: Essays in Honor of Theresa Jarnagin Enos. Eds. Shane Borrowman, Stuart C. Brown, Thomas P. Miller. New York: Routledge, 2009).

Rhetoric that she went on to produce an Encyclopedia of, editing the work entirely by herself.

But she did not become a partisan of rhetoric only. She always stood with “composition”—writing and writing programs—throughout her time as a faculty member in the graduate program in Rhetoric, Composition, and the Teaching of English at the University of Arizona. After that program’s creation in 1988, she was the first outside faculty member hired into the program.

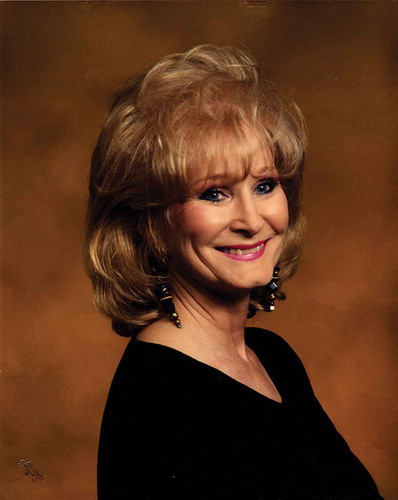

She was an unlikely academic who came up a hard way. She didn’t dress like an academic. She dressed like a “Baylor Beauty,” which is what she was called by the writer of an article in the Baylor University alumni magazine during the time she was in an MA program there.

She dressed that way to the end. Did she suffer for this in the academy? We academics like to think we aren’t moved by such. But name another academic woman who sports a blonde bouffant and fancies ballroom dancing in gowny dresses.

We could never have mistaken her for anybody else.

JOHN WARNOCK

The University of Arizona

______________________

Nearly twenty-five years ago when I was a graduate student, I had my first encounter with Theresa Jarnagin Enos via email. I had sent her a manuscript for Rhetoric Review that I coauthored with Elenore Long, our first essay for publication. Theresa was so encouraging with her feedback and treated us both with such dignity that I felt we were truly welcomed as scholars in the field of rhetorical studies. Around the same time, I coauthored with Richard Young, my mentor, a piece for Theresa and Stuart Brown’s Defining the New Rhetorics. Richard left the correspondence with Theresa and Stuart up to me. Again, Theresa treated me respectfully as if I were her colleague rather than the all-thumbs graduate student I was. Indeed, I’m sure my emails were naïve but she mentored gently and well. My experiences draw attention to one of the wonderful strengths Theresa had—she gave graduate students a voice in her journal and other publications, mentoring them patiently with decorum. I would go on to publish several more pieces in Rhetoric Review and my dealings with Theresa were always so wonderful. I didn’t meet Theresa face-to-face until the 1996 Rhetoric Society of America (RSA) conference that she hosted in Tucson. When I introduced myself and thanked her for her kindness, she already knew me and remembered my coauthored pieces she had published. As busy as she was seeing to all the details of RSA, she took the time to speak with me. I see her as a mentor’s mentor not only in her dealings with those she published, but also in all of her own publications. She left us a wonderful legacy of work that continues to teach us and to stand the test of time.

MAUREEN DALY GOGGIN

Arizona State University

______________________

So much of what we take for granted today in the intellectual world that makes up rhetoric, composition, and writing studies appeared at an early date in Rhetoric Review. When Theresa started the journal in 1982, she provided both an outlet and an impetus for important work that could not be published elsewhere at the time. Look at the tables of contents in issues from the 1980s and 1990s and you see a field coming into being. I am grateful to Theresa for her discerning and non-dogmatic editorship. She should get a lot of the credit for bringing the pulse of rhetoric to the study and teaching of writing.

JOHN TRIMBUR

Emerson College

______________________

I will go to my own end remembering Theresa Enos for being one of the truly major—and usefully so—contributors to rhetoric and composition: for the journal, the Encyclopedia, the surveys of and guides to the graduate programs, the collections done in honor of others, that Rhetoric Society of America (RSA) conference she hosted in Tucson. I will remember her for her great, unapologetic style; for her mentoring of her graduate students and the graduate students of others before, during, and after; for her living example of feminism at work, a smart and strong woman often sailing against winds. We were back-to-back RSA hosts and, as such, had some great notes to share and more than a few tales to tell. We were both late-PhD-getters who had entered academic life as grownups. We could talk turkey, and did. She was a good friend.

FRED REYNOLDS

The City College of New York

______________________

The strongest memory I have of Theresa, from the many years we worked, wrote, and edited together, is the graduate seminar in Writing Program Administration that we co-taught, perhaps ten years ago. We would meet some time before class and map out the issues to be dealt with and how much time to allot to each. We would plan to alternate—twenty minutes for her, twenty minutes for me—as discussion leaders. We had such contrasting teaching styles, it must have been rocky for the students: I’m sure some of them will read this and I’d love to know how they remember it. It was a large and wonderfully engaged group of students. Theresa was organized, structured, and held rigorously to our plan, while I was ever ready to let the class take off in various directions. Just when we were on a roll, she would tap me on the shoulder and point to her watch—my twenty minutes were up. She quieted things down and got us back on track. She combined real professionalism with a delightful warmth of manner, both in teaching and in life. She was a great colleague.

EDWARD M. WHITE

The University of Arizona

______________________

Dang it, Theresa. Thank you for raising us wisely, dear friend, you with your kick-ass boots and honey-please eyes. “It still takes phronesis, practical wisdom,” I remember writing you years ago, “to raise a rhetorician.” Remember? You taught us that lesson over and over, and over again. Bless your big rhetorical heart. Bless your beloved Rhetoric Review. You accepted us all, some of us “with revisions.” In 2009, when I composed a few Wallace Stevens-esque lines for you, we celebrated our forty-some years of professional friendship: “I do not know which to prefer, /The beauty of knowing /Or the beauty of learning, /Wisdom whistling /Or just after.” I’m so thankful that your beauty became our beauty; your truths, our truths; your dangs, my dangs. We’ll miss your wisdom whistling. We’ll miss your love.

HUGH BURNS

Texas Woman’s University

______________________

While I was a PhD student, I met Theresa at Texas Christian University. A new assistant professor at a nearby institution, she told me she was starting a new journal. She exulted that she had coaxed Jim Corder, Ed Corbett, and other luminaries to serve on her editorial board. Somehow, she found the needed funds. After she was—quite unfairly—denied tenure at the nearby, benighted university, she exported her journal to Arizona. She observed, “There are no weekends in this profession.” Her other maxim was: “If I don’t understand an essay, I won’t print it.” When I hear that journals reject excellent work, I gently respond, “Maybe you should start your own journal.” Yet almost no one has the rare blend of initiative, doggedness, and humility that Theresa evinced. The number of our PhD programs has at least tripled or quadrupled since she started Rhetoric Review, as has the number of professional luminaries. Very few people contributed to this blossoming as much as Theresa did. And she published at least eighty percent of them. After being denied tenure, she became a cornerstone for the whole profession.

KEITH MILLER

Arizona State University

______________________

I became a graduate student at a “later age,” past the point of most of my peers in RCTE. I was standing outside the door to Theresa’s next seminar one semester, waiting for a different group of graduate students to exit the room and talking to some of the RCTErs who also waited. I was talking about how I wondered if I was really too old to be doing this, to be in graduate school at all! Behind me I heard Theresa’s voice: “Barbara Heifferon! Don’t you doubt that for one second. You are going to be just fine!” She was always there for me in my moments of doubt and my moments of challenge. I even felt that we have had ESP together when I began to write my comprehensive exam. Imagine my surprise when she had asked about Paul Feyerabend on my philosophy of science exam; he was the theorist I most admired and had read more voraciously than others in this area. Usually our questions were mostly general, and hers, too, were often that way. But she must have known my close affinity for this particular theorist!

Theresa was a good role model; I admired her grit, her abilities, and her strong work ethic. I understood that her early years in West Texas had not been an easy path and yet saw her as so successful in academia, also not a particularly easy path. She kept Rhetoric Review going up until her last days; I had heard from her recently as she needed yet another medical rhetorician to review a submission. I had hoped to see her when I returned to Tucson next year. She will be sorely missed and strongly remembered, perhaps especially by those of us women who still sometimes come up against obstacles because of our gender.

BARBARA HEIFFERON

Louisiana State University

______________________

I first met Theresa at a luncheon for new graduate students. She had presence. Her big jewelry and hair, her makeup, her voice—she was beyond life. I couldn’t stop staring. Nervously, I approached her, thinking my recent acceptance into CCCC was the ticket to the conversation. In her Texan twang, she said: “I don’t like CCCC! It’s toooo big!” Theresa wasn’t one to posture or mince words. That’s when my love for her began.

Her physical voice is now only in my mind; its loss is overwhelming. Roland Barthes, mourning his mother, describes this strange absence: “[H]er voice, which I knew so well, and which is said to be the very texture of memory, I no longer hear” (Mourning Diary: October 26, 1977 – September 15, 1979. Trans. Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang, 2010, 14). I strain to hear Theresa in her scholarship. She critiques the postmodern death of the author because she sees rhetorical ethos as presence: “[E]thos … require[es] both the writer’s textual presence and the reader’s interaction with the living active presence” (Enos, Theresa Jarnagin. “Reports of the ‘Author’s’ Death May Be Greatly Exaggerated But the ‘Writer’ Lives on in the Text.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 20.4 [1990]: 341). Authorial voice, to her, is essential in identification(s).

The practice of a spacious rhetoric, then, is one where “invention, voice, and ethos” are “intertwining and continually opening out again after each closure” one where “argument emerg[es] out of this process and construct[s] ourselves among others” (Enos, Theresa Jarnagin. “From Invention, Voice, and Ethos to Neo-Epideictic Time and Space.” Rhetoric Review 32.1 [2013]: 5). Rhetoric is being in community. Theresa often wrote on the board in class, Rh = Life. It is only fitting that this memorial to my dear friend should end—and so begin—the unending conversation on voice, on presence, on rhetoric, on life.

ROSANNE CARLO

College of Staten Island

______________________

On my first rejection letter for a manuscript I submitted to Rhetoric Review as a graduate student in 2005, Theresa had drawn a smiley face. One of the reviewers had been terse: “I found the paper smug.” Probably accurate, but it crushed my sapling scholarly ego in half. I took Theresa’s smiley face as encouragement, and submitted another project a year later. The next letter I got from the desk of RR—on that official letterhead with the watermark of the pencil becoming a rose—was more promising. She’d scratched out “Professor Jackson” and above it had handwritten “Brian.” At the bottom of the page, she wrote by hand some encouraging words that sweetened the officialese with which she addressed me in the typed comments, the comments about what the reviewers had said and what needed to change in the manuscript. I really liked that mix of high standards and personal support. I sensed, to my chagrin, that Theresa wasn’t going to do me any personal favors to get me published. But I also felt that she had confidence that I could do it. That meant a lot to me at the time.

BRIAN JACKSON

Brigham Young University

______________________

I am indebted to Dr. Theresa Enos for many things including her feminist mentoring, fierce activism in the academy, and fabulous knack for storytelling. Theresa was an important role model for how to be confident and comfortable in one’s skin and one’s decision-making, and she could often get the last word in a debate without making anyone feel silenced. I saw this strength of hers many times during my tenure sitting in RCTE faculty meetings as the English Graduate Union representative. She moved—her pen and her body—with a grace that felt flawless and provoking. Nearly every interaction with her brought clarity to the kind of feminist and academic that I wanted to be, and I am so grateful for the distinct ways that she guided and supported me over the past nine years.

AMANDA B. WRAY

University of North Carolina, Asheville

______________________

We used Theresa’s A Sourcebook for Basic Writing Teachers in my first MA class at Northern Arizona University. Having such a wonderful resource was invaluable to us in the class, of course, but the book also made Theresa into something of a hero to me. You can imagine how excited I was, then, when I completed my MA to be accepted in the RCTE program at the University of Arizona—and I was allowed to help Theresa with Rhetoric Review! Working with her was a joy and those of us who she allowed to help with RR learned so, so much from her (as we did from her graduate classes). I have many wonderful and touching (and funny) memories of those four years—certainly some of the best four years of my life, thanks to my RCTE classmates, faculty, and especially, Theresa.

GREG GLAU

Northern Arizona University

______________________

Theresa once interrupted a Rhetoric Review meeting to pass me two large shopping bags of high heels. She told me that she was too old to wear them and that I was the only person she knew who would appreciate them as much as she had. She then leaned in and added, in her thick accent, “And I don’t have to tell you they’re Italian.” I wore a pair (cherry red pumps, with a bow on top) on my next birthday, and another (three-inch slides in metallic gold) to my high school reunion. I’d always joked with Theresa that I wanted to be her when I grew up. She welcomed me to the field; she introduced me to the study of style; and she always approached life with humor, tenacity, and a great outfit. While I don’t imagine I’ll ever leave the legacy she has, at least I’ll get to walk around awhile in her shoes.

STAR MEDZERIAN VANGURI

Nova Southeastern University

______________________

Theresa would not accept excuses for avoiding what it was we needed to do in the academy. She was dedicated to her students, and she challenged us to check our boundaries and egos. She brought together strands of stylistics, craft, ethos, and identification. She wasn’t about to let us forget the significance of these areas to whichever rhetorical theory was all the rage, and she would not let us forget or marginalize the historical narratives of our field. She was a complicated and important role model. She was a feminist powerhouse. She was not going to fit in a box that made perfect sense, and I admired this very much about her. I know she touched many of us and that several of my colleagues are in mourning. Rest in peace, Theresa. We’ll miss you.

AMANDA FIELDS

Fort Hays State University

______________________

In the fall of 1987, as a reentry student over forty, I ended up at the University of Arizona in Theresa Enos’s Basic Writing class. All those years before, I had been calling it Developmental Writing! Theresa was a diligent, professional, disciplined, and thorough professor. From several classes of hers, I learned how to reframe my twenty years of teaching into professional terms and develop a schema for teaching composition. Theresa also served on my dissertation committee and continued her precise analysis of my submissions. In her classes, Theresa developed her books that would come later. We could discuss Richard Enos’s contributions at CCCC or claim a Peter Elbow sighting. She welcomed her graduate students into the profession with warmth and assistance in any matters we encountered. All during that time, she continued her editorship of Rhetoric Review. In my teaching at Yavapai College in Prescott, Arizona, and at Bradley University in Peoria, Illinois, her voice and wisdom would echo in my ears as I developed assignments, created lectures, and commented on student essays. I was always proud to call Theresa Enos my mentor, inspiration, and wise professor.

EDITH M. BAKER (LAUERMAN)

Bradley University

______________________

Theresa profoundly shaped who I am, both as a teacher and as a scholar. Her critique of my (admittedly awful) comprehensive exam essay so affected me that I worked for the next ten years to write something that would earn her respect, because Theresa has always been “the field” for me. I always imagine her questioning my arguments and my assumptions. When I write, Theresa is the skeptical reader whom I must convince (“Well what do you mean that exotic dancing is rhetorical, Maggie?”). I try to do for my students what she did for me: Inspire them to push themselves because they have something to say. Take them seriously. Respond to them seriously. And remember that flair and humor is always appreciated. And so to end with a bit of that, I give readers this: In the last email exchange we had, we discussed Jo Weldon’s advice that if you can’t think of a burlesque name, just choose your favorite flower and favorite cheese. So in case anyone in rhetoric and composition is wondering, Theresa Enos’s imaginary burlesque name was “Gardenia Havarti.”

The last email I got: “I’ve made the changes, Maggie Daisy—thanks, Theresa Gardenia.”

MAGGIE M. WERNER

Hobart & William Smith Colleges

______________________

Because of Theresa’s many contacts and associations, our then newly-founded RCTE graduate program heard lectures from some of the most prominent scholars in the field of rhetoric and composition: Richard Enos, Patricia Bizell, and many others. I remember a training session for composition instructors in her lovely condo on River Road and a vase of red roses.

CYNTHIA L. HALLEN

Brigham Young University

______________________

I knew Theresa Enos as her intern for Rhetoric Review in 2010. One vivid memory I have of her concerns her asking me to engage in a thought experiment during my oral comprehensive exams. “We’re in a bar, Jessica, now tell me what this is essay is about.” Theresa did not anticipate my aversion to bar scenes, which I still avoid due to experiences therein when I was a graduate student in philosophy. Despite the fact that my response to her question was to freeze, Theresa was much more gracious than someone of her stature needed to be and I trusted her to strike a balance between being tough and supporting me to develop professionally. Theresa, as a mentor and scholar, will always be my bedrock in my conception of audience; she was adamant about imagining and conjuring audience as a means to enter an unending conversation. I hear traces of Theresa’s voice when I read her mentor Jim W. Corder’s words: “We’re here. We make what’s left. Then we go. While we’re here, we give witness to others, to ourselves” (“Symposium: Hunting Jim W. Corder.” Rhetoric Review 32.1 [2013]: 24). Theresa was keenly attuned to how we develop identity with others. Should there be a pub at the end of the universe, I hope to find Theresa there so that I can pull up a chair and tell her what I wanted to write.

JESSICA L. SHUMAKE

The University of Arizona

______________________

During class introductions in my first year as a PhD student in Theresa’s Stylistics and Writing for Publication course, she exclaimed, in her distinctive Texas twang: “Ah-leese, you’re from Texas? But you don’t sound like me!” We were both from the Dallas/Fort Worth area, and I initially chose to pursue my doctoral studies at the University of Arizona because I had written my MA thesis on Corderian rhetoric; Jim W. Corder was, after all, one of Theresa’s mentors. And so, began our nine years of working together—first as her student, then as Rhetoric Review’s intern, assistant editor, and book review editor.

Theresa mentored generously, fiercely, and in numerous ways: I learned just as much about our discipline and our profession, about rhetoric and writing, and about the kind of teacher-scholar I wanted to be from the thoughtful comments she wrote on my seminar papers, as I did from listening to her tell some wild hilarious story about some well-regarded person at some conference, or hearing about her latest ballroom dancing competition and the art of the rhumba, her favorite dance, while we sat, for hours, poring over RR manuscripts in her office. I will miss her candor and her sense of humor, her gentle but unwavering adherence to standards. She asked me to be book review editor not long after I graduated, in those first few months when I struggled with the demands of being a new assistant professor at a new institution in a new part of the country. One day I received a package from her in my campus mailbox. In it were manuscript proofs, with a handwritten note in that green ink she always used for editing: “I just wanted to remind you of why I made these emendations. These ‘RR style’ things actually came from you when you were the style watchdog when you were assistant editor. I think you may have forgotten some of them so I just wanted to remind you.” I read it aloud to myself in her drawling accent and laughed; Theresa always had a way of calling people out, when necessary, without making them feel dumb or inept. She was a remarkable woman, scholar, teacher, mentor, and friend with a larger than life intellect and personality. And she was always well-coiffed, to boot. She was a powerhouse, that Theresa.

ELISE VERZOSA HURLEY

Illinois State University

______________________

Jim W. Corder, her teacher and colleague, emphasizes the importance of the “maverick strain among us,” a metaphor that aptly describes Theresa Enos and her legacy in the field of rhetoric and composition. Fiercely independent and proudly stubborn, Theresa was a true maverick. She wandered from the herd, she forged another path, and she showed others the way.

Theresa believed that in order to push back against the limits, restraints, and failures of language, we must build more space and time into our discourse and that we need to create broader, more inclusive avenues for discourse. Her philosophy of rhetoric is explained in the essay, “A Call for Comity,” which offers a timely perspective in the current socio-political landscape. “We don’t have to argue for a conflict-free society, but we can work toward more constructive, and civil, ways of opposition,” she says, for if “exploring ways of suspending urgency, for a moment can lead to greater comity among us, then this is in itself an opening up to the spaciousness of rhetoric” (“A Call for Comity.” Renewing Rhetoric’s Relation to Composition: Essays in Honor of Theresa Jarnagin Enos. Eds. Shane Borrowman, Stuart C. Brown, Thomas P. Miller. New York: Routledge, 2009. 232).

Theresa believed in me, providing me room to grow, to take risks, and to explore new territory. Sometimes we butted heads, but her love and support propelled me into the professional world, revealed my own maverick strain, and encouraged my commitment to comity in my life as a rhetor and rhetorician.

JENNIFER JACOVITCH

Independent Scholar

______________________

In my office at Moravian College, I have a whiteboard on which I post inspirational quotes. When I received word that my mentor, Theresa Enos, had passed, the board read: “Argument is emergence toward the other. That requires a readiness to testify to an identity that is always emerging, a willingness to dramatize one’s narrative in progress before the other; it calls for an untiring stretch toward the other, a reach toward enfolding the other” (Corder, Jim W. “Argument as Emergence, Rhetoric as Love.” Rhetoric Review 4.1 [1985]: 26). Election day was imminent, and to me there were few better words of praxis than those from Jim Corder to guide me and my students through the divisive political landscape. Theresa not only taught and advocated for this praxis built on a nuanced understanding of narrative and ethos, but she also forwarded Corder’s transactional concept of emergence toward the other in much of her scholarship.

Of course, I will ever appreciate and love Theresa the Rhetoric Review editor, the indefatigable director of the University of Arizona’s RCTE program, the prolific storyteller and fierce feminist. But most important from my perspective is her scholarship on ethos, voice, reflection, and comity. Rejecting postmodern claims of authorial death, she, similar to Corder, believed that writers can live on in their writing via their “transforming ethos,” which she argues manifests itself, dialogically and joyfully, as “voice [that] emerges through the discourse as a way of becoming, knowing” (Enos, Theresa Jarnagin. “Voice as Echo of Delivery, Ethos as Transforming Process.” Composition in Context: Essays in Honor of Donald C. Stewart. Ed. W. Ross Winterowd and Vincent Gillespie. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1994. 187). I take comfort in knowing that I can pick up nearly any piece of Theresa’s scholarship and hear her voice, be with her ethos that surely has transformed and continues to transform me and so many other writer-teacher-scholars in our field.

As Facebook began to flood with memories of Theresa—stories trying to capture her love of rhetoric and composition, her eccentricity, her joy de vivre—I erased the Corder quote and replaced it with the apt closing from “A Call for Comity”: “Time gives us the opportunity for reflection. Because writing stabilizes language … we can actually create time by freezing thoughts that invite reflection and that give us the opportunity to not only self-reflect but reflect as a community” (Enos, Theresa Jarnagin. “A Call for Comity.” Renewing Rhetoric’s Relation to Composition: Essays in Honor of Theresa Jarnagin Enos. Eds. Shane Borrowman, Stuart C. Brown, Thomas P. Miller. New York: Routledge, 2009. 232). Let us heed Theresa’s words as we reflect on her life and continue the work of emergence at a time when doing so may be more important than ever.

CRYSTAL FODREY

Moravian College