ABSTRACT

Urban governance has been thrust into the spotlight in the wake of the Sustainable Development Goals adopted by the United Nations in September 2015. A number of the 17 goals assume strong urban governments with the requisite powers and financial capacities to restructure the functioning of regional economies so as to establish transition pathways toward more sustainable societies. South Africa, and Johannesburg’s metropolitan government in particular, represents an instructive case study of precisely this kind of local government. South Africa adopted one of the most far-reaching systems of decentralization with the advent of democracy in the mid-1990s and enshrined local government autonomy within the constitution of 1996 along with the provision for integrated metropolitan governments. Significantly, these authorities have the powers and fiscal resources to confront conflictual and irresolvable differences in the city, which are inevitable outcomes from decades of oppressive racial government. The article explores the history of democratic decentralization reforms in South Africa and Johannesburg with an eye on analyzing the significance of the Corridors of Freedom flagship initiative of the Johannesburg metropolitan government. This exercise affords a critical perspective on the latest generation of strategic planning and prioritization in metropolitan South Africa.

Urban governance has been thrust into the spotlight in the wake of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by the United Nations in September 2015. A number of SDGs assume strong urban governments with the requisite powers and financial capacities to restructure the functioning of regional economies to establish transition pathways toward more sustainable societies. In light of the broad recognition that city-regions anchor the dynamic flows that constitute globalization processes, it follows that SDGs 8, 9, 11, and 12 pertaining to inclusive growth, decent work for all, resilient infrastructure, sustainable cities, and sustainable consumption and production patterns will fall onto the strategic agenda of urban governments (United Nations, Citation2015). However, assessments of policy reforms since Habitat II in 1996, where democratic decentralization was strongly promoted, suggest that the intergovernmental systems in most developing countries militate against the possibility of urban governments playing a meaningful developmental role (Bahl, Linn, & Wetzel, Citation2013; Pieterse, Citation2015; Smoke, Citation2015). This underscores the importance of exploring the potential of urban governance systems and processes of reform aim]ed at addressing complex development objectives as promoted by the SDGs.

South Africa, and Johannesburg’s metropolitan government in particular, represents an instructive case study. South Africa adopted one of the most far-reaching systems of decentralization with the advent of democracy in the mid-1990s and enshrined local government autonomy within the constitution of 1996. By 2000, a suite of laws had been passed to give effect to the intent of “developmental local government” as stated in the constitution (Parnell & Pieterse, Citation1999; van Donk & Pieterse, Citation2006). The local government elections of December 2000 ushered in the era of fully democratic, autonomous local government, most notably establishing single metropolitan governments in six major jurisdictions (Cameron, Citation2005). Moreover, these metros had strong financial powers and were responsible for up to 80% of their own revenues, a very unusual situation compared to much of the Global South (Gore & Gopakumar, Citation2015). Since then, South African urban governments have been tasked with dealing with the vexed inheritance of apartheid social engineering, spatial planning, and economic exclusion of Black populations (Dewar, Citation1992). At the same time, these authorities are also responsible for addressing the most obvious manifestation of poverty—a lack of access to basic municipal services (water, sanitation, electricity, waste removal, and health care). In other words, South African municipalities have been deeply engaged with the full range of goals encapsulated in the SDGs—the first seven that tend to deal with the fundamentals of abject poverty; the economic infrastructure ones that deal with industrial systems, markets, labor markets, infrastructure, consumption; and the last set that pertains to environmental systems and pressures. An analysis of the South African local governance system is highly relevant for current debates in policy and academic forums about the substantive meaning of developmental local government (Commonwealth Local Government Forum, Citation2013; Smoke, Citation2015).

A central premise of this article is that developmental local government fundamentally involves the capacity to confront conflictual and irresolvable differences in the city. It demands an agonistic spirit rooted in clearly defined principles that are captured in the right to the city movement and discourse (Harvey, Citation2008; Purcell, Citation2013).Footnote1 Practically, this means drawing on planning and governance literatures that demonstrate that urban management involves a continuous navigation of trade-offs between economic, social, and environmental imperatives (Campbell & Fainstein, Citation2003). This literature demonstrates that when unavoidable trade-offs are obscured it creates a breeding ground for simply perpetuating the status quo irrespective how progressive or radical the planning rhetoric might be. When trade-offs are surfaced and confronted through agonistic and systematic processes of deliberation and argument, there is a much greater possibility that public policies could in fact address the systemic causes of urban inequality and uneven development.Footnote2

Democratic urban governance is threatened by the tyranny of consultant-driven simplification and discursive fashions. A number of scholars have observed the damaging effects of policy fashions in terms of simplifying complex realities and shoe-horning politics to prioritize certain urban investments over others (Kornberger, Citation2012; Watson, Citation2014). Sustainable development discourses that operate on the assumption that it is possible to balance economic, social, and environmental issues through effective deliberative processes is certainly a big part of the problem (Pieterse, Citation2011). Thus, since the Earth Summit in 1992, we have seen a procession of urban development policy fashions, most recently manifest in the pervasive discourse on resilience (Newman, Beatley, & Boyer, Citation2009). It is not my intention to get into the intricate politics of urban policy discourse and power; instead, the article traces the evolution of the urban governance dispensation instantiated by the 1996 constitution without delving into the specific interest-based politics in the country or Johannesburg specifically.

In much of the literature on urban governance in Johannesburg, a very strong impression is created that a political fealty to neoliberal prescripts account for the decisions made by the metropolitan government (Didier, Morange, & Peyroux, Citation2012; Winkler, Citation2011; cf. Harrison, Gotz, Todes, & Wray, Citation2014). I argue that this is a fundamental misreading of the context and want to draw attention to the efforts of the political leaders to institutionalize macro processes of investment prioritization that seeks to actively mediate the tension between short-term delivery imperatives and long-term developmental objectives to alter the space economy of the city and address the imperative of spatial transformation in the interest of the urban working classes. This is based on the argument that at the core of effective planning and governance amidst complex trade-offs is the art of balancing short-term and long-term agendas, combined with fostering active political constituencies for the future (Amin & Thrift, Citation2013; Hillier, Citation2002). Whether the Johannesburg metropolitan government (hereafter City of Joburg) will succeed in its efforts to play this game is too early to judge, but shedding light on aspects of their prioritization mechanisms help us to understand future prospects and open the door for more comparative work.

The Corridors of Freedom flagship initiative of the City of Joburg provides a useful case study to explore the latest generation of strategic planning and prioritization in South Africa. This article provides an analytical account of the emergence and significance of the Corridors of Freedom with an eye on elucidating the recent policy processes at national and metropolitan scales to achieve much greater transformative impacts from better coordinated and targeted public-sector expenditure. The national government recently introduced a high-impact grant framework to accelerate transformative investments in the metropolitan areas called Built Environment Performance Plans (BEPPs), which is an outcome of the City Support Programme (CSP) launched in 2012. Johannesburg has been able to capitalize on this new facility because of its own efforts to formulate the Corridors of Freedom initiative, which is tightly aligned with the objectives of the CSP. Due to this confluence, the City of Joburg has been able to leverage substantial resources to move rather quickly with implementing the first phase of the Corridors of Freedom initiative, even though it is designed to achieve medium- and long-term spatial impacts. In this sense, the Corridors of Freedom case study can provide valuable insights into the politics and strategy of balancing short-term and long-term governance imperatives.

Urban governance framework of South Africa

In order to make sense of the City of Joburg case study, it is important to provide some background on the urban governance system of South Africa as it has evolved with the introduction of a new legal dispensation as provided for in the constitution of 1996. However, this is an intricate story that is best consulted in an established body of literature (Harrison, Citation2001; Mabin & Smit, Citation1997; Parnell & Pieterse, Citation1999;Parnell, Pieterse, Swilling, & Wooldridge, Citation2002; Pieterse & van Donk, Citation2013; van Donk, Swilling, Pieterse, & Parnell, Citation2008). It will have to suffice to mention a few key points.

One, metropolitan governments were established as a direct political response to the deep history of racially defined and fragmented local government. Metropolitan governments were promoted to ensure a unified tax base and to most effectively execute a constitutional mandate to implement developmental local government. Central to this mandate was redress and tackling the spatial legacy of segregation, division between places of residence and work, and enhancing the opportunities of peripheral Black populations to access vital urban opportunities. Despite the new legal provisions, after a decade of implementing this local government system it was apparent that urban governments had not managed to fundamentally change the spatial, economic, and social dynamics of cities and towns, as spelled out in the National Development Plan (National Planning Commission, Citation2012). Johannesburg and all South African cities face a daunting set of challenges.

Competing urban policy pressures

Reflecting broader trends, the most challenging and profound pressure on the state in Johannesburg is the deeply entrenched and intertwined problems of structural unemployment, extraordinarily high racialized income inequality, and entrenched spatial divides between the poor on the one hand and formal economic opportunities and the middle classes on the other (City of Johannesburg [COJ], Citation2011; Gotz & Todes, Citation2014; Parnell & Robinson, Citation2006; Todes, Citation2014). The enduring effects of colonialism, racialized rule, and apartheid remain etched in space and the psyche of the society. This can be attributed to the lack of economic transformation in the ownership of the economy combined with limited redistribution of wealth and assets such as land (Philip, Citation2010; Pieterse & van Donk, Citation2008). Predominantly Black working-class people are also relatively poorly educated, which undermines their potential to access employment opportunities in a predominantly services economy. Limited economic transformation ties back to the terms of the negotiated settlement between the liberation movement parties and the apartheid-era White establishment, but it also reflects the limited policy space of post-apartheid South Africa as political freedom coincided with the full and unprotected insertion of the economy into globalized systems of trade and circulation (Marais, Citation2011). Put differently, the state has been profoundly constrained to undertake any economic or land market reforms that may be considered overly redistributive or a threat to market dynamics and private property rights. This is even more acute at the urban scale where local governments are primarily dependent on property taxes for the bulk of their income and loathe intervening in land markets (Todes, Citation2015).

Within this constrained macroeconomic environment, the primary mechanism of redistribution and economic inclusion has in fact been through what is known in South Africa as the social wage (National Planning Commission, Citation2012). This involves the combination of social welfare measures such as old age pensions and child grants, the provision of a minimum level of free basic services, access to public education and health services, subsidized public transport (rail and bus), a public housing program, rate discounts or full subsidies, and various intergovernmental grants to enable municipalities to create the network infrastructure to address basic services for the poor. Local government holds the primary responsibility for providing the built environment aspects of the social wage, which creates a number of complex technical and financial challenges because of the age of large network infrastructures and the speed with which demand for free basic services are growing (Todes, Citation2015).

The social wage cost pressures are compounded by the impacts of the public housing program, which is the de facto driver of urban development investments (Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs [COGTA], Citation2014; Turok, Citation2012). Since 1994, the government has processed close to 4 million subsidies, composed of 952,963 serviced cites and 2,930,485 housing units (by end of March 2015) and has set a target of completing another 1.5 million units by 2019 (Department of Human Settlements, Citationn.d). Similar to the Chilean model, the public housing program guarantees all households below a predetermined income threshold (R 3500/US$263 per month) the right to a “free” public house including the title deed. For the government, this entitlement is the programmatic expression of the constitutional commitment to the right to housing.

Of course, many progressive movements and governments in the (developing) world would be keen to have such a political commitment enshrined in public policy. But this seemingly progressive policy has had disastrous impacts on the livelihoods of the working classes and the poor and the overall urban landscape. Because the 100% subsidy covers the (market) cost of land, internal services, and the physical top structure, the only way in which the program could be implemented by private developers at such a massive scale was through the purchasing of large tracts of cheap land, typically on the peripheries of cities and towns (National Treasury, Citation2012). The spatial effect of this is that class and social segregation has intensified since 1994, with the poorest being furthest away from economic opportunities, and the extremely sprawled/low-density urban form of the apartheid era intensified with disastrous ecological consequences (Harrison, Citation2013; Turok, Citation2012). A diagnostic to this effect was articulated in the government’s Breaking New Ground policy framework of 2004 (Republic of South Africa [RSA], 2004), but without it leading to an exit from the free public housing approach (COGTA, Citation2014). Due to the location of these new housing settlements, local authorities have been compelled to continuously extend network infrastructure systems to far-flung areas without being able to invest nearly enough to ensure optimal maintenance of existing, and aging, infrastructure systems. Furthermore, the new infrastructure systems tend to be of a lower standard to make them affordable, further adding to the cost of routine maintenance. All the while, since the economy is ostensibly stuck in a low-growth gear, national and local budgets remain under severe and increasing strain.

In addition to the public housing program, existing townships and informal settlements are also densifying through infill developments in the form of what is known as “backyard shacks” in South African parlance (Charlton, Gardner, & Rubin, Citation2014). Typically, lower income households erect three to four shacks on their plot to derive rental incomes or provide accommodation for expanding families. This places enormous pressure on infrastructure systems that are designed for a particular level of consumption but are now forced to contend with demand that is four- to fivefold greater than what was designed for. Invariably this reduces the life span of the infrastructure networks, raises the cost of maintenance, and produces more frequent interruptions in the provision of services (Graham, Jooste, & Palmer, Citation2014).

These dynamics are certainly not unique to Johannesburg, but the city government has been engaged in various forms of strategic planning and invention to understand and overcome these pressing realities, from the very beginning of the council in 2001. This is the focus of the next section, but before we unpack that genealogy, it is necessary to explain a national policy intervention called the City Support Programme and, specifically, the BEPPs, which has come onto the table since 2012 to more proactively address these interlinking and arguably wicked urban challenges. In addition, these national government initiatives have reinforced the policy innovations in Johannesburg and provide a substantial portion of the infrastructure capital finance.

Nationally driven urban management innovations

The Breaking New Ground policy (RSA, 2004) adopted by the cabinet in 2004 was a policy watershed. It reflected the political acknowledgement that the public housing-led urban development model was broken and it was worsening the spatial and social dynamics of apartheid-based urban form. However, as intimated earlier, this did not lead to any significant change in the national housing policy approach of the government. Concerned senior policy officers in the presidency, the National Treasury, and the South African Cities Network mobilized behind the scenes to address this policy failure through the promotion of a National Urban Policy, which gained some traction but never achieved cabinet approval for a variety of reasons (Turok & Parnell, Citation2009).

By 2010, in a context of economic decline and stagnation, post the 2008 global economic crisis, the National Treasury had essentially lost all confidence that any of the key urban development departments—Human Settlements, Cooperative Governance, and Transport—could address the policy vacuum around urban development and it would prove impossible to establish a shared policy framework once President Jacob Zuma’s coalition of interests came into power. It was then that the CSP was mooted for the first time (National Treasury, Citation2012).

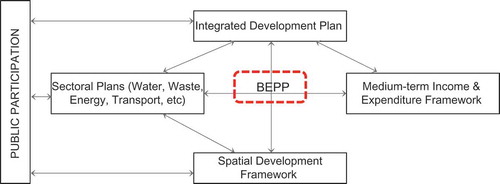

The CSP is premised on a specific problem definition, which in turn leads to a series of thematic priorities: city governance, human settlements, public transport, economic development, and climate change. The policy frame seeks to foster an understanding of the interdependencies of these themes through a conceptual model called the Urban Network Strategy, which in turn gets translated into a plan to drive short-term prioritization and sequencing, called the BEPP (see ). The problem statement of the CSP is blunt:

Urban performance has not, over the past twenty-one years, created cities that are sufficiently inclusive, productive and sustainable. […] The dispersed and fragmented spatial patterns of our cities contribute significantly to the serious structural challenges they face. Although some progress in providing basic services to urban residents have been made our cities remain segregated and exclusionary. […] All this is made worse by the fact that urban governance itself still reflects Apartheid fragmentation. There is a lack of integrated planning and budgeting at city levels where housing, transport and individual services are planned. The result is duplication of roles in project implementation, weak regulatory frameworks and limited oversight of actual performance. Thus there is diffuse accountability for development outcomes, including long-term environmental and fiscal sustainability of investment programmes. (National Treasury, Citation2015, p. 6)

Given the high concentration of the national economy in the eight metropolitan regions of South Africa, the CSP is designed to work closely with them in order to ensure much more effective intersectoral coordination and investment sequencing. The incentive for relatively autonomous and powerful metropolitan governments to participate is a very substantial capital grant program that can be used to acquire strategically located land and the provision of major new infrastructure to accelerate mixed-income, mixed-use living within a transport-oriented (TOD) planning model.Footnote3 The TOD model is localized through the policy strategy called the Urban Network Strategy. It argues that the “creation of inclusive, productive and sustainable cities requires the form of our cities to be transformed from their current fragmented, exclusive and low density spatial form to a more compact and integrated one based on transit oriented development (TOD) principles” (National Treasury, Citation2015, p. 8).

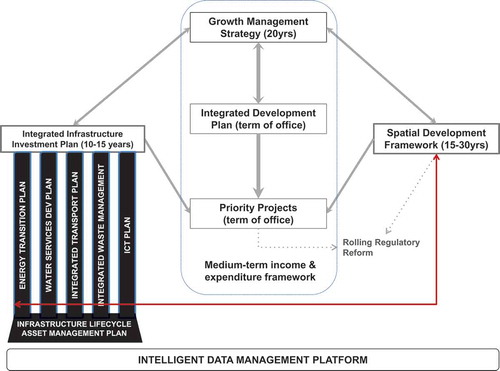

In order to find traction in the routine functioning of metropolitan governments, the CSP requires a new planning tool—the BEPP—to identify “integration zones” where a variety of public investments should be targeted to operate in a synergistic fashion. It is meant to translate the priority intervention points by articulating the statutorily required Integrated Development Plans (5-year term of office plans) and the Metropolitan Spatial Development Framework (20- to 30-year horizon), as illustrated in .

The hope of the National Treasury is that the BEPP will radically improve the practice of intergovernmental and interdepartmental integration to deliver more dynamic nodal points in the metropolitan space economy (National Treasury, Citation2012).Footnote4 The CSP emerged almost alongside the governance and planning reforms of the City of Joburg and as it became more mature it offered a powerful reinforcement for the ambitions of the city to come to terms with spatial transformation imperatives within a grounded understanding of urban growth patterns.

Coming to grips with growth management in Johannesburg

It is impossible to appreciate the significance of the governance shift that the Corridors of Freedom initiative represents without going back to the formation of the Johannesburg metro in 2000 and the preceding transitional phase of local government reform (1996–2000).Footnote5 With the advent of the transitional phase, it was agreed to have a two-tier metropolitan government system. Johannesburg had four strong metropolitan local councils (MLCs) and a relatively weak upper tier metropolitanwide council, known as the Greater Johannesburg Transitional Metropolitan Council (GJTMC). The two-tier arrangement for Johannesburg proved awkward almost from the start. The difficulties led rapidly to a very serious financial crisis (Beall, Crankshaw, & Parnell, Citation2002). Though there are many reasons for the crisis,Footnote6 at the root of all of the problems was that the two-tier arrangements created unhealthy competition between the lower tier MLCs and between the MLCs making up constituent parts of the Johannesburg metro. A problematic aspect of this system was that the MLCs had relative autonomy on expenditure and enjoyed the misplaced comfort that if they ran deficits, the GJTMC would equalize across the four local councils. Invariably, this quickly led to a financial disaster.

By the start of the 1998 financial year, a year and a half after the new system was established, reserves were depleted, the MLCs were in deficit, and none of the structures were in full control of cash flows. When the GJTMC was suddenly presented with a large bill for unpaid bulk electricity, this top-tier structure turned to the MLCs for the required cash and was bluntly informed that funds were not available. With creditors unable to be paid, Johannesburg was declared effectively bankrupt, and power was stripped from the newly elected council and placed in the hands of a small committee charged with ruthlessly cutting back budgets. Overnight the democratic system was replaced with a technocratic management committee appointed between the national and provincial governments (COJ, Citation2006; Todes, Citation2014). Under the auspices of this committee, a financial turnaround strategy was produced with the support of monitor consultants. The strategy was called iGoli 2002 and sought to stabilize the finances of the municipality by reigning in expenditure and effecting strong controls. It was highly controversial because it was seen as an extension of the national neoliberal macroeconomic austerity program introduced in 1996 called the Growth, Employment and Redistribution strategy (Beall et al., 2002).

This dispensation remained firmly in place until a new integrated one-tier City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality was elected in December 2000. However, it is arguable that it assisted the first Executive Mayor Amos Masondo to govern with stability and continuity in terms of governance and management arrangements. As a result, Joburg metro seemed to always be on the cutting edge of strategic metropolitan planning and governance, being early adopters of long-term strategic planning as discussed in the literature (Borja & Castells, Citation1997; Hall & Pfieffer, Citation2000; Healey, Citation2002). Thus, shortly after the elections, iGoli 2010 emerged as an outcrop of iGoli 2002, instantiating a process of strategic stacking with an eye on formulating not just the Integrated Development Plan (IDP) for the terms of office as required by law but also formulating a long-term strategic plan. Barely 6 months after the local elections, Joburg published the City Development Plan (COJ, Citation2001a) on May 29, 2001, to guide departmental prioritization and work, formalize the institutional structure, and create room for the iGoli 2010 process to unfold. By the end of 2001, the city finalized Joburg 2030, its first long-term strategic plan, and made this public by February 2002 (COJ, Citation2006). It had an explicit focus on understanding and responding to the regional economy, which was highly significant for the time when most municipalities were simply trying to figure out how to deal with basic service delivery pressures. However, to soften the economistic focus, Joburg 2030 was published alongside a new Human Development Strategy (COJ, Citation2006; Lipietz, Citation2008), reflecting a political commitment to respond to the claims of neoliberal governmentalityFootnote7 by reflecting a thoughtful engagement with the drivers of poverty and inequality (Gotz, Pieterse, & Smit, Citation2011). Importantly, at this stage there was still no capital budget to speak of, so the only game was achieving a reprioritization within the existing budget envelope of the sectoral departments and hoping for growth in rates income to build up capex capacity for a more expansionist stance.

These early experiments with large-scale and long-view strategies laid a foundation for the formulation of a new Growth and Development Strategy (GDS) and 5-year IDP, both approved in 2006. These two documents were seen as two sides of the same coin: the GDS asked and answered questions about the overall approach to development in the metropolis, set out a vision, and elaborated a set of long-term goals and strategic interventions. The IDP provided the medium-term, 5-year take on this agenda, defining exactly where the city wanted to be on its long term strategic path after the 2006–2011 term of office. It then set out 5-year objectives and a set of comprehensive programs of action in 12 sector plans covering everything from the economy to transport to health and the environment (R. Seedat, personal communication, September 4, 2013). The GDS and 5-year IDP have in turn provided a platform for innovative new strategies that seek to address Johannesburg’s distorted settlement patterns. Among the most important of these was the Growth Management Strategy (GMS) formulated in 2008 (Ahmad & Pienaar, Citation2014; Todes, Citation2014). It defines the desired spatial form of a future Johannesburg with a view to engaging with the stubborn drivers of uneven and unequal land use and property development. Most significant, the GMS compels the City of Joburg to confront its own complicity in this process as the regulatory authority that considers planning applications and grant approvals. At the heart of this act is a pragmatic acceptance that private-sector real estate dynamics are powerful forces that are hard to contain, especially if the revenue base is heavily dependent on property taxes. It is therefore important to briefly recount how the GMS came about and the governance and planning dynamics it set in motion.

Brief history of the GMS

The City of Joburg leadership meet at least twice a year for an extended strategic planning retreat, known as a Lekgotla in South African lingo. During these sessions the mayoral committee members, heads of departments, and senior policy analysts come together under the leadership of the executive mayor to consider high-level strategic priorities and budgetary implications.Footnote8 Most of the tough trade-offs are addressed during these days and in many senses they represent the most visible moments in the strategic trajectory of the metropolitan government. In May 2007, the city’s Lekgotla was held at the Sun City Resort Hotel and the most urgent issue on the agenda was how the municipality will respond to President Mbeki’s invocation that South Africa had to achieve at least 6–8% gross domestic product growth rates if it hoped to address the pervasive legacies of poverty and inequality. Joburg politicians came to the conclusion that this meant that Johannesburg had to achieve at least 9% regional gross domestic product growth rates to support South Africa to meet its goals. The question then arised, how can this be done? (Ahmad & Pienaar, Citation2014).

It is vital to keep in mind that ideologically the African National Congress (ANC) operated within a broader political coalition with parts of the labor movement and the South African Communist Party, espousing socialist commitments to nationalization and anticapitalism. The ANC itself is not socialist but draws on an eclectic mix of radical social democracy, worker control, mixed economy, deep redistribution, and a commitment to human rights principles. Concretely, it means that the ANC accepts a market-based economy but seeks active regulation in the public interest. However, especially White capital is regarded as the root cause of the extended periods of colonialism, neo-colonialism, and ultimately apartheid. This group is also seen as having lost nothing with the political settlement in 1994 and part of the reason why the ANC has struggled to improve the lot of poor Black South Africans in rural and urban areas. So, when a discourse emerges that the government’s primary priority has to be to pursue higher levels of growth, it goes against instinct and deep-seated values and attitudes about the market and the private sector—so much so that most national departments and local governments are deeply averse to entering into formal agreements and joint planning processes with the private sector, which also means that the state generally has a very poor understanding of the inner workings of markets and capital flows. Johannesburg was no exception. Yet, at the conclusion of the Sun City workshop, the idea of growth management had emerged explicitly for the first time and a team in the planning department was allocated R 10 million to explore the concept and present it at the next Lekgotla (Gotz, personal communication, July 7, Citation2014).On February 28, 2008, the first full draft of the Growth Management Strategy was presented at the budget Lekgotla (Pienaar, personal communication, July 3, 2014). It struck a balance between market pragmatism and ideological continuity with the political principles codified in Joburg 2030. The framing device was a two-by-two policy choice matrix that articulated two axes: economic growth and inclusivity. The presentation argued that Joburg was stuck in the low-growth and low-inclusivity box and needed to purposively transition to the high-growth, high-inclusivity box and, en route, avoid the most likely option: higher growth and low inclusivity. Put differently, due to the historical path dependency dynamics of the South African economy marked by mainly postindustrial features, there was a real danger that jobless growth that exacerbates already high levels of inequality will be the result of pursuing a high-growth agenda.

In order to achieve the favored high-growth and high-inclusive development trajectory, the GMS argued that the city had to perform a rigorous diagnostic to understand a number of dynamic trends: the real estate market and cyclical dynamics as shaped by both public and private investments; the state of bulk infrastructure systems and where demand was most acute; the impacts of the public housing program; and the potential of the renewed emphasis on public transport systems in the wake of the 2010 FIFA World Cup preparations. South Africa, and especially Joburg, embarked on an ambitious bus rapid transit system from 2005 onward, buoyed by a new national grant (Wood, Citation2015). In addition, the Gautrain rapid transit system was being implemented and these developments had to be reinforced and leveraged off in terms of the basic principles of the city’s Spatial Development Framework. Most important, the advances in the public transport investments allowed for a return to ideas about spatial restructuring established in the early 1990s and later on codified in various pieces of legislation in the 1994–1999 period (Pieterse, Citation2002, Citation2007).

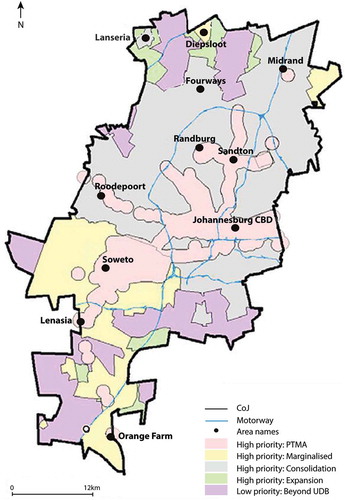

Once the rigorous and spatialized diagnostic is achieved, the GMS involves the identification and ranking of critical programs to address the deficits to a more economically vibrant and inclusive city. Contrary to previous approaches, the GMS argued for a package of incentives that would allow the City of Joburg to work more collaboratively and purposefully with the private sector (Ahmed & Pienaar, Citation2014). The entire scheme turned on a spatial classification that allows the planners to render the territory legible for scarce infrastructure resources or not. It is crucial to understand that at this point most network infrastructure systems were operating at maximum capacity, taking severe strain. In fact, in the early part of 2008, South Africa experienced months of electricity black-outs called “load-shedding” as demand for energy outstripped supply (Todes, Citation2015). Everyone was painfully aware that with a limited capital budget, only a few parts of the city could be invested in. The GMS provided the language, criteria, and decision-making hierarchies to identify where these areas were, with potentially major implications for those parts of the city that do not fall into those areas. The investment prioritization hierarchy operated on the basis of five categories that were within the urban development boundary:

High priority (development/investment/capital)

Public transport areas

Marginalized areas

Medium priority

Consolidation areas

Expansion areas

Low priority

Peri-urban areas (COJ, Citation2008).

provides an overview of how these categories manifest on the Joburg map.

Figure 2. Spatial identification of investment categories for Joburg, 2012. © City of Johannesburg Municipality. Reproduced by permission of City of Johannesburg Municipality. Permission to reuse must be obtained from the rightsholder.

The GMS is underpinned by a fascinating software program—the Capital Information Management System—that allows the planning department to input all of the capital expenditure requirements of the sectoral departments and agencies into a decision-making matrix calibrated to these categories of prioritization (Ahmed & Pienaar, Citation2014). For example, if the stormwater department seeks capex for a new extension to the network or replacing an aging one, it has to indicate whether the investment falls into one of the five categories, which will be taken into account when all of the investment requirements have been evaluated. Because the capex budget is oversubscribed by about 400% in any given year, this instrument does, in theory, provide a powerful means to reorient the investment priorities of the city toward its higher order spatial development goals. Thus, it is envisaged in the GMSFootnote9 that the following outcomes can be achieved over time:

“Prioritisation, clear targeting and programming of capital expenditure;

A strong link between public transport and residential and business development; […]

A change in the way development applications are dealt with, as developments will be subject to a range of new mechanisms to influence patterns and pace of development within the City;

A strong emphasis on the reduction of demand in respect of services; and

Land assimilation for the public good and the location of new housing aligned to these spatial priorities.” (COJ, Citation2008, p. 22)

It is precisely this agenda that compelled the incoming mayor after the 2011 elections to figure out how best the imperatives of restitching the city could be advanced through a high-profile, high-impact initiative.

Corridors of Freedom

The shape of the future City will consist of well-planned transport arteries—the “Corridors of Freedom”—linked to interchanges where the focus will be on mixed-use development—high-density accommodation, supported by office buildings, retail development and opportunities for leisure and recreation. […] The “Corridors of Freedom” will transform entrenched settlement patterns which have shunted the majority of residents to the outskirts of the City, away from economic opportunities and access to jobs and growth. Through the “Corridors of Freedom” Johannesburg will make a decisive turn towards a low-carbon future with eco-efficient infrastructure that underpins a sustainable environment. (COJ, Citation2013, pp. 2, 4)

Corridors of Freedom (CoF) is an evocative title for the flagship initiative of the City of Joburg to systematically drive spatial transformation over the medium to long term. As the official quote above suggests, CoF is essentially a transit-oriented development approach that attempts to steer future (real estate) growth along specific corridors that connect a variety of interchanges and nodes. At these mobility nerve centers, the intention is to aggressively promote “mixed-use development” (Tau & Bloomberg, Citation2014) that will, over time, produce “a new City skyline will consist of high-rise residential developments growing around the transit nodes, gradually decreasing in height and density as it moves further away from the core” (COJ, Citation2013, p. 4).

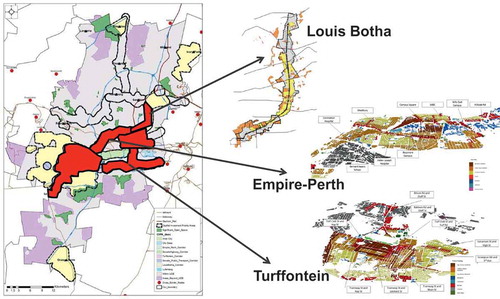

The title plays on the imaginary that 20 years after democratization, the majority of city-dwellers do not experience complete freedom because they remain spatially isolated from urban opportunities. It taps into the ideological discourse of the ANC as encapsulated in the Freedom Charter and is meant to preempt deep-seated frustration about the lack of visible change in the built environment to benefit poorer communities. Since the official unveiling in the State of the City address by Mayor Parks Tau in 2013, eight corridors were proposed, but four are currently under construction: Soweto; Empire-Perth linking Soweto to the CBD; Louis Botha Corridor linking the CBD to Alexandra and Sandton; and the Turfontein Node that is close to the CBD and serviced by the existing Metrobus and rail link (see ). It is anticipated that a Mining Belt corridor will complete its planning in 2016, and three further corridors—Randburg to OR Tambo Airport; Randburg to Diepsloot; and Lanseria Airport and the Mining Belt Alex to Ivory Park—are planned for completion before 2040. In other words, this signature program is a 2-decade agenda to intervene in the space economy of the city.

Figure 3. Corridors under construction. © City of Johannesburg Municipality. Reproduced by permission of City of Johannesburg Municipality. Permission to reuse must be obtained from the rightsholder.

Corridors of Freedom is significant in the larger South African urban planning and management landscape because all municipalities have been claiming a commitment to spatial transformation for the past 2 decades but hardly any have been able to demonstrate how, concretely, they hope to achieve it. The rhetorical power and popular appeal of the program is evident from the various speeches of the mayor in local and many international forums, no least prestigious ones such as C40 and Metropolis. It would not have been possible for Mayor Parks Tau to undertake this signature initiative if the fundamental institutional architecture of the GDS and the GMS were not in place. The commitment to BRT in the preparations for the World Cup in 2010 was also fortuitous because this provided a basis from which to expand the CoF agenda. Furthermore, the GMS argument in particular compelled city officers to understand the extremely fine-grained real estate and infrastructural planning for the corridors.

A number of interrelated policy tools were used. Each corridor has been fleshed out through detailed planning frameworks, which in turn are broken down into detailed precinct plans that allow the municipality to explore the unique development potential in terms of mixed uses at the fine-grained scale, which in turn forms part of a larger modeling exercise to understand the potential residential and business densities that could be yielded once the corridors are mature. In order to ensure that the planning frameworks and the precinct plans are systematically advanced, an integrated capital expenditure framework is produced to ensure optimum alignment, sequence, and integration of various investments into the corridors. This level of planning and foresight has put Johannesburg in a good position to optimize the new national incentives for more transformative planning that flow through the City Support Programme. These connects are set out in impressive detail in the City of Joburg’s BEPP that is available online for public review and comment (COJ, Citation2014).

In many respects, the CoF initiative is high risk. In the first instance, it does not target the most deprived areas in the city for this level of capital investment. This can fuel and exacerbate discontent within the ANC and among the poorest citizens who form the most important electoral constituency for the ruling party. The choice to concentrate investments in the corridors has already elicited vociferous criticisms from political opponents of the mayor within his party. This dynamic is being potentially exacerbated by the new initiative of the Gauteng government under the leadership of Premier David Makura. (The City of Joburg is one of three metropolitan governments within the Gauteng province.Footnote10) During his State of the Province address of 2015, he announced their own priorities for reordering the space economy of the province, which involves embracing a number of mega private-sector-led real estate developments that are arguably at the edges of the Johannesburg metropolitan area (Makura, Citation2015). The issue, of course, is that if these come to pass, they will require massive municipal infrastructure investments from Joburg and other adjoining municipalities to make them viable, which would undoubtedly dilute the resources available for the phasing of the implementation of the CoF. How this tension will be addressed remains unclear.

A third risk is the attitudes of the private sector and whether Joburg will be able to leverage in enough private-sector investment to make it viable in terms of the real estate growth assumptions of the policy approach. According to research by Cartwright and Marrengane (Citation2015), private-sector actors are adopting a wait-and-see attitude linked to a concern that the city is distorting conventional market dynamics. They are worried that the city will treat any project in the corridor as inherently good irrespective of its inherent coherence and viability, and this will have a negative impact on the market over the long term. Their concerns are not unrelated to the fact that the real estate market is in a slow-down since economic growth rates struggle to reach 2% at the moment.

In speaking to Mayor Parks Tau (personal communication, July 12, 2014) about these issues, he demonstrated an acute awareness and understanding of all of them but remains utterly convinced that a TOD-based, high-impact, and targeted intervention is not optional and that the middle-class and private-sector actors who remain skeptical need to appreciate that it is a historical and political necessity. It therefore requires a combination of steadfastness, clear incentives, political coherence, and enough short-term gains to grow a constituency behind it. Whether these elements will cohere or not is difficult to measure, but if there is a political leader with the experience and finesse in negotiating complex interests, it is probably Parks Tau.

Implications of the South African case

There are important lessons to be drawn from the South African and Johannesburg experience. If we take the SDG imperatives discussed in the introduction as a starting point for what urban governance and planning need to address during the next generation, it is clear that we need institutions that can negotiate long-term and short-term political and environmental imperatives; figure out how to sustain economic development but also effect a transition to a completely different kind of economy in terms of resource intensiveness, carbon emissions, consumer preferences, degree of inclusivity, and labor intensiveness; and the nature of political engagement and responsiveness. This is a tall order for established and relatively well-resourced urban governments in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries, let alone emerging systems in much of the Global South.

Consequently, the new generation of urban governance and strategic planning approaches will need to make allowance for the mediated nature of modern politics; that is, the ways in which politics is irrevocably embedded in constantly changing symbolic realms shaped by (new) media, the Internet, and the reorientation of traditional media. This era seems to insist on strong leader-led narratives about the future of cities that connects back to popular seams within the public realm and civil society. These narratives need material anchors that manifest in high-profile mayoral projects, which in turn make room for more systemic programs and strategic interventions that produce a structural change in urban space, access to opportunity, and political empowerment. City leaders and administrations that will try to spin these political imperatives will be punished politically as a much more restless, globally connected, and youthful citizenry shift the expectations of urban political compacts. The ICT revolution is central to this new political culture.

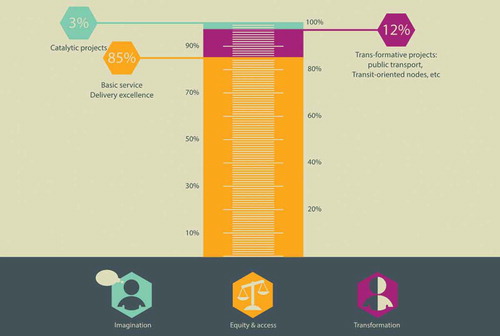

Because public transport, mobility, and safety are central to actualizing the right to the city, we can anticipate that the TOD-based agenda for spatial transformation that is gaining ground will remain a dominant theme in the repositioning of urban governance and planning. It is in this context that the City of Joburg Growth Management Strategy and evolving processes of spatial transformation point to an important 20/80 principle, which can help city governments in different contexts to close the gap between policy intent and outcomes. provides a stylized account of how to think about the distribution of resources of urban governments to exercise clear leadership, invest in TOD-based initiatives to catalyze spatial transformation, and pressurize the powerful sectoral departments to change the ways in which they do their work to bring it in line with the transformative goals of the city government and society.

In this stylization, the mayor or city leadership is afforded 2–3% of the total budget to drive highly visible public campaigns around the signature issues that mark the term of office. Ideally, these are not just vanity projects but consistent with the next 12–15% of expenditure, which seeks to effect systemic change through catalytic interventions. The remaining 85% reflects the routine operations of a municipality, with an understanding that the component of the sectors that need to collaborate on an area basis or interdisciplinary teams to make the catalytic projects succeed will be the leverage point to shift the institutional culture of the entire organization over time. This is exactly what the CoF represent in the Johannesburg case.

This summation is obviously an overly simplified and airbrushed rendition that does not foreground the messy realities of competing departmental rivalries, deep ideological and professional schisms (for example, between engineers and environmental planners), territorial competition for resources, political infighting among members of the party that impact on levels of cooperation and compliance, intergovernmental interference, corruption, the imperatives of populist gestures, and so on (Haferburg & Huchzermeyer, Citation2015). All of these factors are at play in Johannesburg and probably any city in the world one cares to mention. It is, of course, the stuff of modern democracy, but it remains possible to conceptualize an approach to navigating these realities toward the higher order developmental objectives that are now enshrined as global norms through the SDGs and, in the case of South Africa, the Bill of Rights.

In the end, urban management and politics is about fostering a commitment to societal learning through agonistic engagement and continuous agreements to take the next step, without being able to resolve all difference (McFarlane, Citation2011). On the contrary, the point is to recognize that in highly unequal and power-laden societies, difference cannot be erased but only deployed to clarify what exactly is required to effect social justice in the short and medium term to inform a learning agenda about what the long-term horizon requires from citizens, the associations, and political representatives elected into public office. Governance becomes meaningful and effective when short-term drivers in urban management are tempered by substantive, informed, and politically embedded long-term perspectives.

In South Africa, this learning has meant a refinement of the urban governance and planning imaginary of the mid-1990s as manifest in the constitution and the White Paper on Local Government (Department of Provincial and Local Government, Citation1998). Thus, instead of simply relying on a term of office plan, linked to a long-term spatial plan, there is now recognition that other instruments are needed to deepen democratic debate and achieve much greater precision in acting on the systemic drivers of urban injustice. sets out the emerging institutional architecture for urban governance in South Africa as recognized in the Integrated Urban Development Framework (COGTA, Citation2014) and the Built Environment Performance Plans of the eight metropolitan governments. Given the convergence of urban development challenges across the north and the south in an era where societies are trying to figure out the implications of low-carbon and inclusive growth paths, anchored in city-regions, the South African experience may be a useful place from which to theorize the implications.

Figure 5. Emerging urban planning and management system in South Africa. Adapted from Integrated Urban Development Framework: Draft for Discussion, by Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs, Citation2014, Pretoria, South Africa: Author. © Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs. Adapted by permission of Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs. Permission to reuse must be obtained from the rightsholder.

Conclusion

Urban governance has been thrust into the spotlight in the wake of the SDGs adopted by the United Nations in September 2015. The scope and interdependency of the 17 goals reflect the complexity of operationalizing actions within the state and across society to achieve these desired outcomes. It is striking that urban governments are given pride of place in taking the lead in implementing a range of policies to achieve complex SDG outcomes. In a broader context where democratic decentralization has not been implemented with great vigor or efficacy in large parts of the Global South, it is useful to turn to the South African experience with metropolitan governance with an explicit developmental mandate that preempts the discourse of the SDGs.

This article has provided a sweeping overview of the constitutional provisions of developmental metropolitan government that can adopt a highly proactive and strategic role in understanding and addressing systemic obstacles to the advancement of sustainable urban development. The article traces the constitutional and legal provisions that underpin the efforts of the City of Joburg in adopting strategic planning systems, which, in turn, over a decade produce a new set of planning instruments to be able to address the intransigent spatial underpinnings of uneven development. Put differently, the City of Joburg was compelled to move beyond a basic needs service delivery approach to one that seeks to reverse deep patterns of structural racial exclusion from the economy and urban opportunity. At its core, the article demonstrates that this demands an institutional and political willingness to surface and confront difficult trade-offs between competing priorities, with significant political implications. Over time, this broad commitment had to be concretized in order to impact on the spatial allocation of scarce capital investment resources that drive infrastructure investments.

The current mayor of Johannesburg packaged this agenda in the affective language of Corridors of Freedom, which turns out to be the result of a confluence of long-term institutional reforms to understand growth dynamics and the decisive role of national government in promoting spatial transformation through targeted infrastructure investment within a TOD planning paradigm. In the final instance, the article draws out a few implications of this case study to contribute to broader debates about the contested nature of urban governance and planning processes aimed at getting serious about spatial transformation and sustainability.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Nuno Ferreira da Cruz for his impeccable support. This article forms part of a larger and ongoing research collaboration with Graeme Gotz. His ideas and insights have greatly shaped the analysis, but the author remains solely responsible for the argument here.

Funding

The author acknowledges the support of the New Urban Governance Project by LSE Cities at the London School of Economics and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The research for this article was also supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions presented in this article are entirely those of the author and should not be attributed in any manner to any of these entities.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Edgar Pieterse

Edgar Pieterse holds the South African Research Chair in Urban Policy at the University of Cape Town and is director of the African Centre for Cities. He is the co-author with AdbouMaliq Simone of New Urban Worlds: Inhabiting Dissonant Times (Polity, in press) and City Futures: Confronting the Crisis of Urban Development (2008) and co-editor of Africa’s Urban Revolution (2014) and Rogue Urbanism: Emergent African Cities (2013). He is consulting editor of CityScapes, a magazine dedicated to urbanism in the Global South.

Notes

1. This is not the occasion to get into a detailed discussion on the differences within the right to the city movement and where I position myself. Those debates are captured in Marcuse et al. (Citation2009) and, pointedly, in Purcell (2013).

2. The theoretical underpinnings of this approach are explored elsewhere (Pieterse, 2005).

3. It is beyond the scope of this article to delve into the expansive literature on TOD (Curtis, Renne, & Bertolini, Citation2009). Similar to other contexts, TOD references the promotion of urban development that involves medium- and high-density mixed-use settlements anchored by public transport nodes and the gradual intensification of mobility corridors between such nodes to evolve a dense and efficient urban form. In South Africa it is explicitly connected to social and racial integration objectives as well (Bickford, Citation2014).

4. The CSP focused on the eight metropolitan governments has a finite life span: April 1, 2012–March 31, 2017. There will be a major evaluation in 2016 to determine wheter it should be redesigned to extend to the 22 second-tier cities in South Africa.

5. This section draws liberally on Gotz et al. (Citation2011).

6. For a full account of the reasons for the crisis, see COJ (Citation2001b), section 1.

7. The charge of neoliberal reform was also rooted in the fact that iGoli 2002 created a basis for a new institutional model that saw the administration being broken up into a variety of corporatized entities (nine), agencies (two), and utilities (three), all of which supported by a core administrative cohort along with some remaining sectoral departments (COJ, Citation2006). For an excellent version of this critique, see Murray (Citation2008).

8. In terms of the relevant legislation, the executive mayor is elected by the full council. He or she is then empowered to appoint a mayoral committee that assists in making decisions, proposals, and plans that have to be approved by council, where legislative authority resided. The council may delegate any executive powers to the executive mayor and in most cases they have extensive delegations, making the mayoral committee function almost like a cabinet structured around specific portfolios.

9. An important consequence of the GMS was a clear representation of where real estate development was concentrated over a 5-year period (2006–2010). It demonstrated unequivocally that the bulk of new development approval applications were in the consolidation areas, close to the urban development boundary. For example, in the period 2006–2010, 468 applications were submitted in the consolidated areas, of which 221 were approved, compared to 79 applications submitted in the high-priority public transport areas, of which only 22 were approved. In other words, despite the rhetoric of earlier development planning frameworks and various policy commitments to pursue densification along transport corridors, the day-to-day exigencies of the planning approval system were effectively reproducing patterns of urban development that went against the grain of the formal priorities. An important step in being able to address this dynamic is to make it legible and subject to explicit political consideration. This is precisely what the GMS enabled.

10. Provincial governments are predominantly responsible for social development functions such as education and health and share concurrent powers with other levels of government for economic planning, housing, and infrastructure provision and environmental planning. However, provinces rely on national transfers for 95% of their revenue, whereas municipal governments like Joburg raise up to 80% of their own revenue, making them a lot more autonomous and flexible compared to provincial governments.

References

- Ahmad, P., & Pienaar, H. (2014). Tracking and understanding changes in the urban built environment: An emerging perspective from the city of Johannesburg. In P. Harrison, G. Gotz, A. Todes, & C. Wray (Eds.), Changing space, changing city: Johannesburg after apartheid (pp. 101–116). Johannesburg, South Africa: Wits University Press.

- Amin, A., & Thrift, N. (2013). Arts of the political. New openings for the left. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Bahl, R. W., Linn, J. F., & Wetzel, D. L. (Eds.). (2013). Financing metropolitan governments in developing countries. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

- Beall, J., Crankshaw, O., & Parnell, S. (2002) Uniting a divided city: Governance and social exclusion in Johannesburg. London, England: Earthscan.

- Bickford, G. (2014). Introduction. In South African Cities (Ed.), How to build transit-oriented cities. Exploring the possibilities (pp. 1–12). Johannesburg, South Africa: South African Cities Network.

- Borja, J., & Castells, M. (1997). Local and global. The management of cities in the Information Age. London, England: Earthscan.

- Cameron, R. (2005). Metropolitan restructuring (and more restructuring) in South Africa. Public Administration and Development, 25, 329–339.

- Campbell, S., & Fainstein, S. (2003). Introduction: The structure and debates of planning theory. In S. Campbell & S. Fainstein (Eds.), Readings in planning theory (2nd ed., pp. 1–17). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Cartwright, A., & Marrengane, N. (2015). Urban governance and turning African cities around. Unpublished manuscript, City of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa.

- Charlton, S., Gardner, D., & Rubin, M. (2014). Post-intervention analysis: The evolution of housing projects into sustainable human settlements. In South African Cities Network (Ed.), From housing to human settlements. Evolving perspectives (pp. 75–94). Johannesburg, South Africa: South African Cities Network.

- City of Johannesburg. (2001a). City development strategy. Draft. Johannesburg, South Africa: Author.

- City of Johannesburg. (2001b). Johannesburg: An African city in change. Johannesburg, South Africa: Zebra Press.

- City of Johannesburg. (2006). Reflecting on a solid foundation: Building developmental local government 2000–2005. Johannesburg, South Africa: Author.

- City of Johannesburg. (2008). Growth management strategy, 2008. Johannesburg, South Africa: Author.

- City of Johannesburg. (2011). Joburg 2040: Growth and development strategy. Johannesburg, South Africa: Author.

- City of Johannesburg. (2013). Corridors of Freedom: Re-stitching our economy to create a new future. Johannesburg, South Africa: Author.

- City of Johannesburg. (2014). Built Environment Performance Plan 2014/15: Towards the Corridors of Freedom. Johannesburg, South Africa: Author. Retrieved from https://csp.treasury.gov.za/Resource%20_Centre/Cities/Pages/City_of_Johannesburg.aspx

- Commonwealth Local Government Forum. (2013). Developmental local government: Putting local government at the heart of development. London, England: Author.

- Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs. (2014). Integrated Urban Development framework: Draft for discussion. Pretoria, South Africa: Author.

- Curtis, C., Renne, J. L., & Bertolini, L. (2009). Transit oriented development: Making it happen. London, England: Routledge.

- Department of Human Settlements. (n.d.) Housing delivery statistics. Pretoria, South Africa: Author. Retrieved from http://www.dhs.gov.za/content/housing-delivery-statistics

- Department of Provincial and Local Government. (1998). White paper on local government. Pretoria, South Africa: Author.

- Dewar, D. (1992). Urbanization and the South Africa City: A manifesto for change. In D. Smith (Ed.) The apartheid city and beyond (pp. 244–255). London, England: Routledge/Witwatersrand University Press.

- Didier, S., Morange, M., & Peyroux, E. (2012). The adaptative nature of neoliberalism at the local scale: Fifteen years of city improvement districts in Cape Town and Johannesburg. Antipode, 45, 121–139.

- Gore, C., & Gopakumar, G. (2015). Infrastructure and metropolitan reorganization: An exploration of the relationship in Africa and India. Journal of Urban Affairs, 37, 548–567.

- Gotz, G., Pieterse, E., & Smit, W. (2011). Desenho, limites e perspectivas da governança metropolitana na África do Sul [Design, limits and prospects of metropolitan governance in South Africa]. In J. Klink (Ed.), Governança das metropoles: Conceitos, experiências e perspectivas [Comparative perspectives on metropolitan governance for Brazil] (pp. 127–156). Sao Paulo, Brazil: Annablume.

- Gotz, G., & Todes, A. (2014). Johannesburg’s urban space economy. In P. Harrison, G. Gotz, A. Todes, & C. Wray (Eds.), Changing space, changing city: Johannesburg after apartheid (pp. 117–136). Johannesburg, South Africa: Wits University Press.

- Graham, N., Jooste, M., & Palmer, I. (2014). Municipal planning framework. In South African Cities Network (Ed.), From housing to human settlements. Evolving perspectives (pp. 29–54). Johannesburg, South Africa: South African Cities Network.

- Haferburg, C., & Huchzermeyer, M. (2015). An introduction to the governing of part-apartheid cities. In C. Haferburg & M. Huchzermeyer (Eds.), Urban governance in post-apartheid cities. Modes of engagement in South Africa’s metropoles (pp. 3–14). Pietermaritzberg, South Africa: University of Kwa-Zulu Natal Press.

- Hall, P., & Pfheiffer, U. (Eds.). (2000). Urban Future 21. A global agenda for twenty-first century cities. London, England: E & FN Spon.

- Harrison, P. (2001). The genealogy of South Africa’s Integrated Development Plan. Third World Planning Review, 23(2), 175–193.

- Harrison, P. (2013). South Africa’s spatial development: The journey from 1994. Johannesburg, South Africa: Wits University.

- Harrison, P., Gotz, G., Todes, A., & Wray, C. (2014). Materialities, subjectivities and spatial transformation in Johannesburg. In P. Harrison, G. Gotz, A. Todes, & C. Wray (Eds.), Changing space, changing city: Johannesburg after apartheid (pp. 2–39). Johannesburg, South Africa: Wits University Press.

- Harvey, D. (2008). The right to the city. New Left Review, 53, 23–40.

- Healey, P. (2002). On creating the “city” as a collective resource. Urban Studies, 39, 1777–1792.

- Hillier, J. (2002). Shadows of power. An allegory of prudence in land-use planning. London, England: Routledge.

- Kornberger, M. (2012). Governing the city: From planning to urban strategy. Theory, Culture and Society, 29, 84–106.

- Lipietz, B. (2008). Building a vision for the post-apartheid city: What role for participation in Johannesburg’s city development strategy? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32, 135–163.

- Mabin, A., & Smit, D. (1997). Reconstructing South Africa’s cities? The making of urban planning 1900–2000. Planning Perspectives, 12, 193–223.

- Makura, D. (2015). Gauteng State of the Province Address 2015. Johannesburg, South Africa: Gauteng Provincial Government.

- Marais, H. (2011). South Africa pushed to the limit: The political economy of change. London, England: Zed Books.

- Marcuse, P., Connolly, J., Nolly, J., Olivo, I., Potter, C., & Steil, J. (Eds.). (2009). Searching for the just city. Debates in urban theory and practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

- McFarlane, C. (2011). Learning the city. Knowledge and translocal assemblage. Chichester, England: Wiley Blackwell.

- Murray, M. J. (2008). Taming the disorderly city. The spatial landscape of Johannesburg after apartheid. Cape Town, South Africa: UCT Press.

- National Planning Commission. (2012). National Development Plan 2030: Our future—Make it work. Pretoria, South Africa: The Presidency, Republic of South Africa.

- National Treasury. (2012). Budget Review 2012. Pretoria, South Africa: Author.

- National Treasury. (2015). Cities Support Programme framework. Pretoria, South Africa: Author.

- Newman, P., Beatley, T., & Boyer, H. (2009). Resilient cities: Responding to Peak Oil and Climate change. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Parnell, S., & Pieterse, E. (1999). Developmental local government: The second wave of post-apartheid urban reconstruction. Africanus, 29(2), 68–85.

- Parnell, S., Pieterse, E., Swilling, M., & Wooldridge, D. (Eds.) (2002). Democratising local government: The South African experiment. Cape Town, South Africa: UCT Press.

- Parnell, S., & Robinson, J. (2006). Development and urban policy: Johannesburg’s city development strategy. Urban Studies, 43, 337–355.

- Philip, K. (2010). Inequality and economic marginalisation: How the structure of the economy impacts on opportunities on the margins. Law, Democracy & Development, 14, 105–132.

- Pieterse, E. (2002). From divided to integrated city? Critical overview of the emerging metropolitan governance system in Cape Town. Urban Forum, 13, 3–37.

- Pieterse, E. (2005). Transgressing the limits of possibility: Working notes on a relational model of urban politics. In A. Simone& A. Abouhani (Eds.), Urban processes and change in Africa (pp. 160–180). London, England: Zed Books.

- Pieterse, E. (2007). Tracing the “integration” thread in the South African urban development policy tapestry. Urban Forum, 18, 1–30.

- Pieterse, E. (2011). Recasting urban sustainability in the south. Development, 54, 309–316.

- Pieterse, E. (2015). Governance and legislation. Cape Town, South Africa: African Centre for Cities, University of Cape Town.

- Pieterse, E., & van Donk, M. (2008). Developmental local government: Squaring the circle between policy intent and outcomes. In M. van Donk, M. Swilling, E. Pieterse, & S. Parnell (Eds.), Consolidating developmental local government: Lessons from the South African experience (pp. 51–76). Cape Town, South Africa: UCT Press.

- Pieterse, E., & van Donk, M. (2013). Local government and poverty reduction. In U. Pillay, G. Hagg, J. Jansen, & F. Nyamnjoh (Eds.), State of the nation 2012–13. Addressing inequality and poverty (pp. 98–123). Pretoria, South Africa: HSRC Press.

- Purcell, M. (2013). The right to the city: The struggle for democracy in the urban public realm. Policy & Politics, 41, 311–327.

- Republic of South Africa. (2004). Breaking new ground. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Human Settlements, South African Government.

- Smoke, P. (2015). Rethinking decentralization: Assessing challenges to a popular public sector reform. Public Administration and Development, 35(2), 97–112.

- Tau, P., & Bloomberg, M. (2014, October 13). Green cities can help breathe new life into a nation’s growth. Business Day.

- Todes, A. (2014). The impact of policy and strategic spatial planning. In P. Harrison, G. Gotz, A. Todes, & C. Wray (Eds.), Changing space, changing city: Johannesburg after apartheid (pp. 83–100). Johannesburg, South Africa: Wits University Press.

- Todes, A. (2015). The external and internal contest of post-apartheid urban governance. In C. Haferburg & M. Huchzermeyer (Eds.), Urban governance in post-apartheid cities. Modes of engagement in South Africa’s metropoles (pp. 15–35). Pietermaritzberg, South Africa: University of Kwa-Zulu Natal Press.

- Turok, I. (2012). Urbanisation and development in South Africa: Economic imperatives, spatial distortions and strategic responses ( Working Paper No. 8). London, England: International Institute for Environment and Development.

- Turok, I., & Parnell, S. (2009). Reshaping cities, rebuilding nations: The role of national urban policies. Urban Forum, 20(2), 157–174.

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. New York, NY: Author.

- van Donk, M., & Pieterse, E. (2006). Reflections on the design of a post-apartheid system of (urban) local government. In U. Pillay, R. Tomlinson, & J. du Toit (Eds.), Democracy and delivery: Urban policy in South Africa (pp. 107–134). Pretoria, South Africa: HRSC Press.

- van Donk, M., Swilling, M., Pieterse, E., & Parnell, S. (Eds.) (2008). Consolidating developmental local government: Lessons from the South Africa experiment. Cape Town, South Africa: UCT Press

- Watson, V. (2014). African urban fantasies: dreams or nightmares? Environment and Urbanization, 26, 215–231.

- Winkler, T. (2011). On the Liberal Moral Project of Planning in South Africa. Urban Forum, 22, 135–148.

- Wood, A. (2015). Transforming the post-apartheid city through bus rapid transit. In C. Haferburg & M. Huchzermeyer (Eds.), Urban governance in post-apartheid cities. Modes of engagement in South Africa’s metropoles (pp. 79–97). Pietermaritzberg, South Africa: University of Kwa-Zulu Natal Press.