?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study investigates the driving forces of industrial land expansion under China’s unique land use system in the context of economic transition with an explicit emphasis of the interactive relationship between local government and enterprises. Stemming from institutional insights in a transitional economy, this study develops a novel framework to integrate governmental intervention, firm–government connection, and economic transition to explain the spatial patterns and reveal the mechanisms of industrial land expansion in China. Based on the national utilization conveyance data and spatial econometrics, this study confirms that local government intervention and firm–government connection affect industrial land development significantly and in a spatially heterogeneous way. This study contributes an institutional and transitional knowledge to understand rapid industrial land expansion in China.

Since the 1980s, China has experienced unprecedented economic growth, as well as dramatic land-centered urbanization (G. C. Lin, Citation2007). In China’s urbanization, the land has been used as a tool to stimulate economic development (Tian & Ma, Citation2009). As a result, construction land has witnessed a striking increasing. According to the national land utilization conveyance data compiled by the Ministry of Land and Resources, the urban area increased from 5.41 million ha to 8.01 million ha during 1996 to 2008. At the same time, as a critical dimension of urban expansion, China’s industrial land has witnessed a rapid growth; the total area of industrial land increased from 2.76 million ha to 4.04 million ha, with a growth rate of 46.4%. The rapid expansion of construction land, especially industrial land, has caused a major concern about food security and social disruptions (Lichtenberg & Ding, Citation2009; G. C. Lin & Ho, Citation2003, Citation2005; Song, Citation2014). Though the patterns and dynamics of urban land expansion have been well documented in the existing literature, industrial land expansion, which accounts for a lion share of construction land development, has not received much attention (He, Huang, & Wang, Citation2014; Huang, Wei, He, & Li, Citation2015; Tu, Yu, & Ruan, Citation2014).

Industrial land expansion has been rooted deeply in the context of China’s institutional restructuring and land administration. According to China’s Land Administration Law, land ownership is segmented into state-owned and rural collective–owned. The law also states that only the state-owned land can be used for nonagricultural purposes. With economic development, local governments have to requisition rural collective–owned land to meet the increasing industrial land demands. In the planned economies, industrial land was granted to state-owned enterprises for free (Huang & Du, Citation2016). Since the economic reform, the penetration of globalization has encouraged the bloom of foreign- and non-state–owned enterprises, which has accordingly promoted the marketization process of land use rights. As a result, industrial land markets have been established across the country since the 1980s (Zhu, Citation1994). However, at the initial stage, because of the intense competition among local authorities in attracting investments, industrial land prices were largely dependent on negotiations between local governments and investors, rather than a competitive outcome between enterprises, which directly led to low prices of industrial land use rights (W. D. Liu & Deng, Citation2008; Tu et al., Citation2014). To regulate and control local governments’ behavior, the approaches of bidding, auction, and listing were introduced to terminate the noncompetitive and agreement-based assignments of land use rights in 2003. Additionally, since 2006, the Ministry of Land and Resources has issued a standard to control the minimum price of transferring land use rights. Although several policies have been introduced to regulate the phenomena of transferring industrial land use rights at an extremely low price, compared to commercial and residential land prices, industrial land prices remain at a relatively low level, leading to the potential waste of land resource (Lai, Peng, Li, & Lin, Citation2014; Wu, Zhang, Skitmore, Song, & Hui, Citation2014).

Earlier literature mainly focuses on the patterns and mechanisms of urban land expansion in China by providing a neoclassical understanding from the demand side (Deng, Huang, Rozelle, & Uchida, Citation2008, Citation2010; He et al., Citation2014; Jiang, Deng, & Seto, Citation2012; Li, Wei, & Huang, 2014; Luo & Wei, Citation2009; Seto & Kaufmann, Citation2003). Recent studies have shifted to the political and institutional perspectives, which focus on the land supply-side story (Huang et al., Citation2015; Tian & Ma, Citation2009). Following this line, studies have further investigated industrial land expansion, an important dimension and component of urban land development (Huang et al., Citation2015; Tu et al., Citation2014). The institutional stream naturally overemphasizes efforts from the local administration as land providers and underestimates the influence of other important participants from the demand side (He, Zhou, & Huang, Citation2016; Ping, Citation2011; Wei & Ye, Citation2014). Therefore, an integrated and reliable framework emphasizing the roles of manufacturing firms and their connections to local government in industrial land development will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms of China’s land-centered urbanization.

This study therefore proposes a framework to investigate how the local government–enterprise relationship affects China’s industrial land development, by highlighting the importance of local government interventions, firm–government connection, and spatial dependence. The intervention from local government guarantees a low-price land transfer, and the firm–government connection further causes an oversupply of industrial land. Industrial land expansion in China is spatially correlated in nature, because the neighboring cities tend to follow each other to transfer industrial land to meet economic and political goals. Using national land utilization conveyance data for the prefectural cities during 2004–2008, this study first describes the patterns of industrial land expansion and then assesses the roles of local government–firm relationships in the expansion process. We find significant spatial variations in industrial land expansion at the prefectural level, and the agglomerations mainly concentrate in the Bohai Sea Rim Area and the Yangtze River Delta. Econometric modeling suggests that local government intervention could significantly promote industrial land expansion, and the three aspects of motivation, ability, and level affect expansion in different ways. Moreover, the firm–government connection plays a vital role in industrial land expansion.

This study contributes to the literature on urban land expansion in several ways. First, we focus on industrial land specifically, rather than simply treating urban land as an indistinguishable whole, which is particularly important when we realize that different land types display various mechanisms of expansion (He et al., Citation2016; Huang et al., Citation2015). Second, we develop an innovative framework to analyze industrial land expansion in transitional China, by highlighting the institutional foundations. Third, this study first measures prefectural government interventions and firm–government connection and further confirms their impacts on industrial land expansion, even after adjusting for variations in globalization, marketization, and spatial autocorrelation.

Local government intervention, firm–government connection, and industrial land expansion: Analytical framework

In a transitional economy, relationship refers to using interpersonal resources to gain benefits. A relationship in this context is not just a simple connection or an artifact of social embeddedness but also the result of shared responsibility between counterparts in society. In China, relationship is a cultural tradition that should be established and maintained and mobilized intentionally and as part of the social ladder that plays a critical role in shaping social structures. Thus, in this study, government–firm relationship essentially refers to the interactions between local governments and businesses. Governments and firms are the most important and influential organizations in China, and the cooperative or competitive nature of their relationships greatly influence economic operations. We further divide the government–firm relationship into two interactive parts: local government intervention and firm–government connection. Local government intervention refers to how the local governments affect firms, whereas firm–government connection means the effects from the opposite direction.

Local government intervention

In a marketized economy, there has been a long-term debate over government interventions since the classical economic theory. Adam Smith (1776/Citation2002) emphasizes the role of “night watchman,” which means leaving the economy to the market. In contrast, to explain the underlying mechanisms of the Great Depression, the Keynesian school emerges by arguing that government regulation and intervention are necessary to avoid market failure. In a transitional economy, China’s experience proves that rent-seeking behavior of local officials is not an inevitable outcome of government intervention, and the pro-business role of local officials plays a decisive role in economic growth (Frye & Shleifer, Citation1997).

In China, local government intervention is the result of fiscal decentralization and political centralization (He et al., Citation2016). Since the 1980s, the central government has gradually transferred its power to localities, which has deeply altered central–local relations and the behavior of local governments (He & Zhu, Citation2007). As a result, local governments hold primary responsibility for urban and economic development in their jurisdictions (Qian & Weingast, Citation1996). At the same time, the tax sharing system has granted local governments more fiscal responsibility. The tax sharing system has introduced a clear distinction between federal and local taxes. The central government collects the value-added tax, which is shared by local governments at a fixed ratio of 25% (Chung, Citation1994). This tax sharing system has substantially reduced the revenue streams of local governments, which further forced localities to secure extra-budgetary revenues.

Although the Chinese economy has largely been liberalized, institutional and cultural environments have remained politically centralized. The power of promotion of local officials is still highly concentrated in upper-level governments. Economic performance and other competence-related indicators have become the primary criteria for evaluation of governmental officials (Li & Zhou, Citation2005). The central government rewards and punishes local officials on the basis of economic performance, pushing them to pursue higher gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates and more local revenues (Blanchard & Shleifer, Citation2001). Pressure from upper-level governments and competition with neighboring administrative units provoke local officials to step into local economic activities in the role of governor and participant at the same time (He et al., Citation2016). The most common manner is attracting investments by leasing land to manufacturing sectors to maintain a stable and long-term tax income.

Local governments can accumulate low-cost land under the current land administration system (Ding, Citation2007). According to China’s land use policies, there are only two kinds of land ownership: land owned by the state and land belonging to village collectives. Rural collective–owned land can only be used for agricultural or rural development. Developers or firms who need the land for urban or industrial construction should request a land quota from local governments. Therefore, as the sole supplier of land, local governments can use their “monopoly” as a key instrument in the regional competition for investments (M. Liu, Tao, Yuan, & Cao, Citation2008; Tao, Su, Liu, & Cao, Citation2010). By providing land at a very low negotiated price, local governments are capable of attracting industrial investors through site-clearing–style packaged development, which means that local governments are responsible for clearing up potential industrial sites and improving their infrastructure (G. C. Lin, Citation2007).

Therefore, three aspects could be used to identify local governments’ interventions in their industrial land supply: motivation for intervention, ability to intervene, and level of intervention. Motivation for intervention refers to the stimuli that prompt local governments to intervene in the industrial land expansion process. Ability to intervene can be defined as the authority or administrative resources to intervene in economic activities. Financial resources and approaches are necessary for local authorities to deal with land requisition and demolishing, as well as to clean up the potential industrial land. Level of intervention refers to the extent to which local governments intervene in industrial activities. Overall, strong motives and the ability for government intervention will encourage local governments to provide more land for industrial use. We propose the first research hypothesis here:

H1:

Stronger local government intervention results in faster industrial land expansion.

Firm–government connection

Firm–government connection refers to the active relation to local governments developed by firms for subsidies or other economic benefits. Its theoretical basis is the social capital theory posited by Pierre Bourdieu (Citation1986) in the 1970s. Social capital is made up of social connections and can be transformed into economic capital and institutional capital. This means that individual actors can leverage their existing capital to obtain economic resources, enhance their influential positions, and forge close relationships with formal institutions (Bourdieu, Citation1986). Portes (Citation2000) considers social capital to be realistic or potential integration of resources, which more or less have some relationship with institutional familiarity and approval. N. Lin (Citation2002) defines social capital as the access to various resources through network ties. Thus, as an important form of social capital, the firm–government connection will apparently benefit enterprises, especially in China.

Empirical studies have documented the existence of firm–government connections worldwide. Faccio (Citation2006) points out that a large number of listed companies from 47 countries are politically connected, especially in countries with higher levels of corruption. Using survey data from firms and entrepreneurs in Liuzhou, Guangxi, Chen, Cheng, and Gao (Citation2005) provide evidence that Chinese entrepreneurs in private businesses are translating their economic richness and household backgrounds into political power. In China, typical motivations for firm–government connections include an imperfect institutional design, low marketization, and special cultural traditions (Fan, Wong, & Zhang, Citation2007). Bai, Lu, and Tao (Citation2006) further show that the firm–government connection is particularly effective in promoting corporate development and protecting property rights.

Under China’s unique land use policy, the firm–government connection can benefit related firms in several ways. As the sole supplier of industrial land in China, local government approval is certainly central to firms’ economic pursuits. To some extent, the establishment of firm–government connections is a prerequisite for gaining industrial land, and this influence on China’s industrial land development is also self-evident. Local governments tend to provide more land resources to firms with a better connection with local officials, which also implies selective and biased land supply. Cai, Henderson, and Zhang (Citation2013) argue the existence of selective auctions in China’s land market. Local governments are more likely to use listing, rather than bidding and auction, to transfer and use rights, because listing is easier to manipulate to meet some strategic conspiracies achieved by local governments and target enterprises. Thus, we propose the second research hypothesis as follows:

H2:

A more robust firm–government connection leads to greater industrial land expansion.

Additionally, existing literature has clearly demonstrated the existence of spatial autocorrelation in China’s urban land expansion (He et al., Citation2014; Li, Wei, Liao, & Huang, Citation2015). Scholars have found clusters of urban land development in the Yangtze River Delta, Pearl River Delta, and some other urban agglomerations. Two primary reasons could explain these clusters. First, factors influencing urban expansion, such as trade between prefectures, technology, and knowledge diffusion, as well as, more generally, regional spillovers are likely to lead to geographically dependent urban land development for prefectures (He et al., Citation2014; Li et al., Citation2015). Second, competition among local governments in attracting investment leads to a similar magnitude of urban expansion (Lin & Ho, Citation2005). In particular, industrial land development is significantly influenced by regional spillovers and local competition (He et al., Citation2016; Tao et al., Citation2010). Scholars have found that local governments follow their neighbors to build industrial parks and development zones, and the leasing price for industrial land is significantly impacted by the action price of neighboring cities (Huang & Du, Citation2016; Thun, Citation2004; Wei & Ye, Citation2014). The “race to the bottom” results not only in low leasing prices but to similar patterns and mechanisms of industrial land expansion in neighboring cities (Tu et al., Citation2014).

In summary, we hypothesize that industrial land expansion in China is significantly associated with local government intervention and firm–government connection (). To investigate the role of local government intervention thoroughly, we stress the importance of three dimensions of motivation for intervention, ability to intervene, and level of intervention. Furthermore, globalization and marketization have been widely confirmed as two significant forces of urban land expansion in transitional China (Huang et al., Citation2015; Li et al., Citation2015). Globalization has urged cities to establish economic development zones and to improve infrastructure and R&D facilities to attract foreign direct investments (FDIs) and other global resources. Marketization has not only triggered the development of private enterprises but has also led to the openness of land markets.

Data sources and methodology

Data sources

The land use data used in this study are official national land utilization conveyance data from 2004 to 2008. The data are provided by the Ministry of Land and Resources (MLR) of the People’s Republic of China and initially taken from the first national land survey in 1996. The MLR has since updated the land use data based on the annual official approval of land utilization conveyance collected by land departments at the county level until 2008. The data are the official land use change data in China and are often used in academic studies (G. C. Lin, Citation2007, Citation2009; Wang, Chen, Shao, Zhang, & Cao, Citation2012). It is worth pointing out that the national land utilization conveyance data may underestimate the actual changes in land use, because there are some unapproved land developments (G. C. Lin & Ho, Citation2005). The underestimation could be more significant in large and fast-growing cities where land development propels accelerating revenues.

In the national land utilization conveyance data, land use is divided into categories at three levels: the first level includes agricultural land, construction land, and unused land. The category of construction land consists of three subcategories: settlements and industrial/mining sites, transportation land, and land for water conservancy facilities. The settlements and industrial/mining sites subcategory could further be divided into cities, designated towns, rural settlements, standalone industrial/mining sites, and other construction land uses. This study defines industrial land as land use for standalone industrial/mining sites, which are largely located outside the city. Standalone industrial/mining sites are chosen for two reasons. First, because we aim to examine the change in industrial land during 2004–2008, standalone industrial/mining sites are appropriate because industrial firms are established primarily at the edges of cities instead of at the core of urban areas. Second, mining industries face the similar administrative regulations as all other industrial sectors.

We choose 2004–2008 as the study period based on the following reasons: First, industrial land expanded rapidly from 2004 to 2008, which gives us a chance to explore its underlying mechanisms. Second, two relevant events happened during 2001–2003: one was China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in late 2001; another was the establishment of bidding, auction, and listing procedures by the MLR in 2003. These two events might alter the patterns and mechanisms of China’s industrial land development. Third, the classification criteria and statistical scope of the land use survey have changed since 2009. Thus, to maintain comparability of data, we choose 2004–2008 as our investigation period.

This study focuses on industrial land in 286 prefectural and above cities (Lhasa was excluded due to data availability). According to China’s land management law and land use policies, only municipal and county-level governments have the right to lease land to firms. The power allows municipal governments to act strategically in supplying land for industrial uses. As such, the prefectural city level is an appropriate scale for our analysis.

Model specifications and variables

To understand the mechanisms of industrial land expansion, we conducted a spatial econometric analysis to link local government–firm connection to industrial land expansion during 2004–2008. As we mentioned in the literature review, the stiff competition and similar economic development goals of neighboring prefectures might lead to a spatially correlated expansion in industrial land (He et al., Citation2014). We apply the spatial lag model (SLM) and spatial error model (SEM) to identify the determinants of industrial land expansion by controlling spatial autocorrelation. The equations for SLM and SEM, respectively, are as follows:

where is the spatial weight matrix, and

and

are coefficients for spatial lag and spatial error terms, respectively.

refers to the total change in industrial land in prefectural city i during 2004–2008.

and

are the independent variables relating to local government intervention and firm–government connection, respectively, in city i in 2004, and

refers to their interaction effect.

is the controlling variable vector.

and

are error terms for city i. We apply OpenGeoda (Anselin, Syabri, & Kho, Citation2010) to generate the

matrix using first-order rook contiguity.

According to our framework, we have three dimensions in measuring local government intervention: motives, ability, and level. To quantify these factors, we select some variables as proxies.

First, motives for intervention refers to the reasons or objectives for which local governments are likely to intervene in the industrial land expansion process. We employ two variables to quantify the reasons for intervention, including the growth of industrial output (INDUS) and the growth of local industrial employment (JOB). Economic output and employment are two important indicators to evaluate the performance of local governments under the politically centralized institutional arrangement in China. Both indicators have a close association with the promotional opportunities of local officials. Thus, an active and significant relationship is expected for these two variables.

Second, the ability to intervene is defined as the authority or administrative resources a local government has to intervene in economic activities. Because fiscal decentralization is an essential characteristic of the economy of transitional China, financial conditions will significantly influence local governments’ behaviors (G. C. Lin, Li, Yang, & Hu, Citation2014; G. C. Lin & Yi, Citation2011; Tao & Wang, Citation2010). Improved fiscal capacity is an incentive to supply more land for industrial uses. We introduce the ratio of fiscal income to fiscal expenditures at the prefectural level (EXPEN) into the model to capture the tax capacity of local governments (He et al., Citation2016) and expect a positive coefficient. The other aspect of the ability to intervene is the administrative capacity, which can be captured by whether it has a national-level economic and technological or high-tech industrial development zone (DZ; Wei & Ye, Citation2014). The establishment of DZs can enhance the power of local governments by offering them more rights to create attractive investment policies (Yang & Wang, Citation2008).

Third, the level of intervention refers to the extent to which local governments intervene in economic activities. We introduce the ratio of fiscal income to GDP at the prefectural level (LEVEL) to quantify the level of intervention that local governments could provide in local economic development (He et al., Citation2016). We expect a positive coefficient as well.

To assess the impact of firm–government connection, we use the ratio of new firms that gain subsidies from local governments (SUBSIDY) as a proxy (Fisman, Citation2001). The subsidy has been widely used in capturing connections between firms and local governments. Firms with a closer relationship with local authorities are more likely to gain more subsidies. We expect a positive coefficient here.

Globalization and marketization are two factors that influence industrial land expansion significantly. China has been gradually integrated into the global market since the 1980s. With increasing globalization, increasing foreign investment has boosted economic growth in China, especially in coastal provinces. FDI in China is mainly concentrated in the manufacturing sectors, which directly leads to rapid expansion of industrial land. We select the ratio of industrial output from foreign firms to the GDP (notated herein as rFDI) to reflect the effect of globalization. Marketization emphasizes the increasing role of markets and private sectors. Since the 1980s, non-state–owned enterprises (NSOEs) have increased rapidly in scale and size, which in turn requires more industrial land. Thus, the ratio of industrial output from NSOEs to the gross industrial output (rNSOE) is chosen to capture the effect of economic marketization.

Furthermore, we control for a range of variables that influence land resource constraints and industrial land demands. The first is the prefectural population density (DENS), which reflects the direct land use demand (Huang & Du, Citation2016). The second is the ratio of secondary output to GDP in the prefectural city (SECOND), which reflects the economic structure of a city (Huang & Du, Citation2016). Next, we include cultivation land per capita in (PCULTI) to capture the restriction of land resources (He et al., Citation2014). Higher levels of cultivated land provide local governments with more opportunities to convert agricultural land for industrial use. Then, the land leasing price (PRICE) is included in the models to control local governments’ price competition. Finally, to monitor the effects of minimum price standards, we add a dummy variable of URBAN, which equals 1 if a city belongs to direct-controlled municipalities, vice-provincial cities, or capital cities. We speculate that the minimum price standards policy might have a greater impact on prefectural-level cities than those of direct-controlled municipalities, vice-provincial cities, or capital cities. All variables are summarized and reported in .

Table 1. Definition of independent variables.

In addition to the land use data, other socioeconomic data used are collected from China Statistical Yearbooks (National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2005d, Citation2006d, Citation2007d, Citation2008d, Citation2009d), China City Statistical Yearbooks (National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2005b, Citation2006b, Citation2007b, Citation2008b, Citation2009b), and China’s Regional Economic Statistical Yearbooks (National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2005e, Citation2006e, Citation2007e, Citation2008e, Citation2009e). Land supply data are from China Statistical Yearbooks of Land and Resources (National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2005c, Citation2006c, Citation2007c, Citation2008c, Citation2009c). The variable “SUBSIDY” is derived from the Annual Survey of Industrial Firms provided by the National Bureau of Statistics (Citation2005a, Citation2006a, Citation2007a, Citation2008a, Citation2009a) in China, which offers detailed amounts of governmental subsidies to each firm. To ensure the comparability of monetary variables, we use the Consumer Price Index to compute the constant price data.

Spatial patterns of industrial land expansion

Along with the rapid growth of China’s economic scale, industrial land in China has witnessed significant increases since the 1990s and skyrocketed after China entered the World Trade Organization in 2001. shows the growth of the city and designated towns land and industrial land areas. From 2004 to 2008, the city and designated towns land increased from 3.40 million ha to 3.96 million ha, whereas industrial land area jumped from 3.60 million ha to 4.04 million ha. The growth rates reached 16.47 and 12.22%, respectively. The rapid expansion of industrial land could be explained by China’s industrialization after the reform and opening-up to some extents, but more research is needed to explore the broad mechanisms.

To map and capture the spatial variation of industrial land expansion, we define central, eastern, and western regions according to their geographical locations. depicts the prefectural variation in industrial land expansion during 2004–2008. The prefectural cities in the eastern provinces of Liaoning, Hebei, Shandong, Jiangsu, Fujian, and Guangdong, as well as some inland prefectures such as Chongqing, Erdos, and Kunming, witnessed faster industrial land expansion. In contrast, prefectural cities in the western and central regions experienced less industrial land development. The spatial inequality is largely caused by the open door policy and globally general preferences for coastal regions. China’s open door policy was spatially unequal, with coastal cities first being opened up to foreign investors. The coastal areas have used their locational and institutional advantages to attract more FDIs and international trade, leading to faster industrial land expansion.

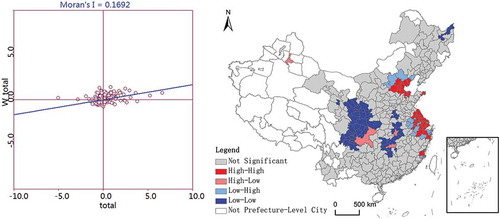

We further apply Moran’s I and local indicators of spatial association (LISA) to analyze the global and local spatial dependence of industrial land expansion. Positive and significant values for Moran’s I indicate spatial dependence, whereas LISA analyses allow us to evaluate local variations in spatial relations. The Moran’s I value for the change in industrial land area between 2004 and 2008 is 0.17 and statistically significant, indicating that industrial land expansion in China exhibits significant spatial dependence. Chinese cities seem to follow their neighbors to provide land for industrial uses in response to the strong fiscal and political incentives of land development (He et al., Citation2016). Spatial dependence in industrial land expansion arises from regional spillover, as well as interregional competition in economic development and the imperatives of political promotion. As shown in , high–high values of industrial land use change are found in the Bohai Sea Rim Area and the Yangtze River Delta. Industrial land changes in the northeast and northern regions tend to be more spatially segregated. Interregional competition in central China may not be as intensive as it is in the east because of the lagging market reforms.

Mechanisms of industrial land expansion

presents the correlation coefficients between variables. The change in industrial land area is positively and significantly associated with the proxies for the local government–firm relationship. Globalization and marketization are also positively related to industrial land expansion. In line with our expectations, the relationship of PCULTI and industrial land change is negative. EXPEN and INDUS, as well as EXPEN and DZ, are moderately correlated, with correlation coefficients exceeding 0.5, 0.51, and 0.54, respectively. Other correlation coefficients are relatively small. Therefore, there is no serious multicollinearity issue in the model estimations.

Table 2. Correlation coefficient matrix.

shows the results of ordinary least squares (OLS), SLM, and SEM. Because the dependent variable is the change in industrial land area from 2004 to 2008, all variables use data from 2004 except for proxies for motives for intervention and firm–government connection. Among the models, R2 values are higher than 0.36, indicating that the model is sufficiently robust to explain industrial land expansion.

Table 3. Exploring the mechanisms of industrial land expansion in China.

The regression results suggest that motives for intervention and ability to intervene, firm–government connection, their interactions, globalization, marketization, as well as spatial dependence have a significant influence on China’s industrial land expansion. First, existing studies attribute the promotion of local GDP growth and the increase in employment as primary motivations for local governments to supply industrial land (Yang & Wang, Citation2008). The coefficient of INDUS is significantly positive, whereas JOB has a negative but insignificant coefficient. The results indicate that local economic growth is indeed the primary motive to supply land to industries. The creation of industrial employment, however, is not a key factor. Second, for the ability to intervene, the variables of EXPENS and DZ are positive and significant. Better fiscal condition enhances the financial ability of local governments to clear up the potential industrial land. Higher administrative status also provides more policy flexibility to attract investments (Li et al., Citation2015; Tu et al., Citation2014; Yang & Wang, Citation2008). The results are consistent with our expectation that the ability to intervene is significantly related to industrial land expansion in China. Third, the coefficient of SUBSIDY is significantly positive, which is in line with our expectation. As SUBSIDY increases by 1%, industrial land expands by 0.322%. Prefectures giving more subsidies to manufacturing firms witness more expansion of industrial land, indicating the importance of firm–government connections (Fisman, Citation2001).

Fourth, the interactions INDUS*SUBSIDY and EXPEN*SUBSIDY have significantly positive coefficients, suggesting that high motives for government intervention and financial ability coupled with firm–government connection collectively drive China’s industrial land expansion. This confirms our theoretical proposition and highlights the critical role of local governments in supplying industrial land and the significant feedback role of manufacturing firms. Fifth, globalization and marketization significantly promote industrial land expansion. As China’s industrialization process unfolds along with the opening up, the influx of FDI and international trades stimulate the rapid development of manufacturing, which in turn increases the demand for industrial land (Huang et al., Citation2015). Meanwhile, China’s industrialization process is closely related to market-oriented reforms, which have spawned a large number of non-state-owned firms, increasing the demand for industrial land.

Finally, the coefficients of spatial lag variable and spatial error variable are significantly positive, implying that there are significant spatial effects in the industrial land expansion. The spatial dependence of industrial land expansion can be attributed to the regional spillover of driving factors and interjurisdictional competition in local development (He et al., Citation2014; Li et al., Citation2015). Fiscal decentralization has triggered interregional competition to develop industries to increase local revenues, and political centralization has stimulated interregional competition between local officials in improved economic performance for promotion opportunities. Local governments tend to follow their neighboring regions to provide land for industries (He et al., Citation2016).

The regional differences in economic development, resource endowments, and institutions lead to a different mechanism of industrial land expansion. We conducted regressions for subsamples of the three regions and aim to reveal significant spatial differences in the driving forces of industrial land development ().

Table 4. Spatial heterogeneity of mechanisms of industrial land expansion in China.

First, the coefficient of INDUS is significantly positive in the models of the eastern and western regions but not significant in the central region model. Local governments in both coastal and western regions have strong motives to supply industrial land. The coastal region has been pursuing industrial upgrading, replacing traditional labor-intensive industries by capital- and technology-intensive industries. The western region has been rapidly and extensively industrialized, relying on resource exploitation.

The central region has also been actively receiving industries transferred from the coastal region. Local governments in the central region also have a strong motive to supply industrial land to attract manufacturing firms. This motive, however, has not significantly expanded industrial land. This might be because the motive did not draw significant outcomes. Different from the motive, the ability to intervene in the central region triggers rapid industrial land expansion. Government’s ability to intervene is more of a factor in industrial land expansion in the central region because industrial development in the central region is still on the rise and the central region forms the core of regional industrial transfer. Local governments in the region compete intensively to attract transferring firms, which in turn motivates local governments to increase their intervention efforts vis-à-vis investment in infrastructure and the related economic activities. Therefore, the financial and administrative capacities of local governments are particularly important in the industrial land expansion process (Huang et al., Citation2015).

Second, for the eastern and western regions, strong firm–government connections significantly promote industrial land expansion, whereas it has an insignificant influence in the central region. This result could be interpreted from the perspective of regional resource disparities. As the constraint on land resources has increased in the eastern region, the access to land resources has become increasingly difficult. Political connections enable firms to gain land because local governments are the sole provider of land. In the central region, land is relatively abundant. In the western region, strong firm–government connections would significantly stimulate the expansion of industrial land due to the less liberalized economy and the long-term traditions of local government intervention.

Furthermore, the interactions between local government intervention and firm–government connection have significant and positive effects on industrial land expansion in models of central and western regions, providing further evidence to support the critical role of local governments in industrialization of inland regions. Finally, the effects of globalization and marketization show significant regional variances. Globalization plays a major role in the eastern region, whereas market forces show strong effects in the central region, indicating that the growth of the non-state–owned economy is of particular importance to industrial land expansion for central prefectures.

Overall, industrial land development not only relies on the process of globalization and marketization but is determined by local government intervention and the firm–government connection. Moreover, these multiple institutional factors are sensitive to regional disparities. The eastern and western regions’ industrial land development received more influence from the relationships between firms and local governments.

Summary and policy implications

China has witnessed significant industrial land expansion in the past 2 decades. Based on national land utilization conveyance data from 2004 to 2008, this study finds substantial spatial variations in industrial land expansion at the prefectural level. Industrial land expansion is also found to be spatially dependent, with high–high values particularly in the Bohai Economic Rim and the Yangtze River Delta. The results of OLS, SLM, and SEM indicate that local government interventions, firm–government connections, and their interactions significantly promote China’s industrial land expansion.

Rapid industrial land expansion has accompanied China’s remarkable economic development and urbanization. Unprecedented industrialization and FDI flows have created huge demands for industrial land. The story of how fiscal and political incentives urge local governments to provide more land for industrial use has been widely neglected (Ping, Citation2011). This study offers a new perspective to understand the driving forces of industrial land expansion in China by highlighting the critical roles of local government intervention and firm–government connection. This study provides an institutional and social understanding of rapid industrial land expansion in a transitional economy. We argue that China’s urbanization cannot be simplified as a land-centered urbanization but is a relationship-based process involving various actors.

This article has several policy implications according to industrial land use. First, because local government intervention has been the main driving force of industrial land expansion, the central government needs to temper local authorities’ impetus to sell land. One of the instruments for the central government might be controlling the scale of expropriating agriculture land. In addition, regulating land use efficiency standards in development zones is a strategy that could prohibit industrial land expansion. Second, governments should build a more open and competitive land market to create a fair environment for firms to use industrial land. Furthermore, industrial land prices should be regulated above a certain level to prevent inefficient use of land. Third, because firm–government connections have a great impact on industrial land expansion, more transparency is needed in the process of selling land. Bidding and auction are apparently better approaches than listing in achieving this target. Finally, more local context–based land use policies should be established. More attention should be paid to regulating the land market in the central region for its current rapid industrial land expansion.

Funding

We acknowledge funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41601126, 41425001), Central University of Finance and Economics (QJJ1528), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (China).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zhiji Huang

Zhiji Huang earned his PhD in human geography from Peking University in 2015 and currently serves as an Assistant Professor at the Central University of Finance and Economics in Beijing, China. He has been a Research Fellow at Peking University–Lincoln Institute Center for Urban Development and Land Policy since 2015 and served as a Vice Executive Secretary of the Regional Science Association of China since 2016. His research interests include industrial development and land use policy. He has co-authored three academic books and published more than 20 papers.

Canfei He

Canfei He is a Professor and the Dean of College of Urban and Environmental Sciences at Peking University. He earned his PhD in geography from Arizona State University in 2001. Dr. He is the deputy director of the Peking University–Lincoln Institute Center for Urban Development and Land Policy. His research interests include industrial geography and urban and regional development. He is on the editorial board of Eurasian Geography and Economics, Growth and Change, and Area Development and Policy. Dr. He has published 12 books in Chinese and about 70 papers in international journals. He was granted the Outstanding Young Scientist Award by the National Natural Science Foundation of China in 2014 and was entitled the Cheung Kong professorship in 2016 by the Ministry of Education in China. He was listed by Elsevier as one of the most cited researchers in mainland China (social sciences) for three consecutive years (2015–2017).

Han Li

Han Li is a Postdoctoral Research Associate in the Department of Geography at University of Utah. His research interests include urban amenities, urbanization, and urban land expansion in China and the United States. His current research utilizes the technical advancements in GIS spatial modeling, remote sensing, and spatial statistics to examine the dynamics and effects of urban expansion in developing countries.

References

- Anselin, L., Syabri, I., & Kho, Y. (2010). GeoDa: An introduction to spatial data analysis. In M. M. Fischer & A. Getis (Eds.), Handbook of applied spatial analysis: Software tools, methods and applications (pp. 73–89). Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Bai, C.-E., Lu, J., & Tao, Z. (2006). Property rights protection and access to bank loans. Economics of Transition, 14, 611–628. doi:10.1111/ecot.2006.14.issue-4

- Blanchard, O., & Shleifer, A. (2001). Federalism with and without political centralization: China versus Russia. IMF Staff Papers, 48(4), 171–179.

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of social capital. In G. John Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–260). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Cai, H., Henderson, J. V., & Zhang, Q. (2013). China’s land market auctions: Evidence of corruption? The Rand Journal of Economics, 44, 488–521. doi:10.1111/rand.2013.44.issue-3

- Chen, G., Cheng, L. T., & Gao, N. (2005). Information content and timing of earnings announcements. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 32(1–2), 65–95. doi:10.1111/j.0306-686X.2005.00588.x

- Chung, J. H. (1994). Beijing confronting the provinces the 1994 tax-sharing reform and its implications for central–provincial relations in China. China Information, 9(2–3), 1–23. doi:10.1177/0920203X9400900201

- Deng, X., Huang, J., Rozelle, S., & Uchida, E. (2008). Growth, population and industrialization, and urban land expansion of China. Journal of Urban Economics, 63, 96–115. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2006.12.006

- Deng, X., Huang, J., Rozelle, S., & Uchida, E. (2010). Economic growth and the expansion of urban land in China. Urban Studies, 47, 813–843. doi:10.1177/0042098009349770

- Ding, C. (2007). Policy and praxis of land acquisition in China. Land Use Policy, 24, 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2005.09.002

- Faccio, M. (2006). Politically-connected firms: Can they squeeze the state? American Economic Review, 96, 369–386. doi:10.1257/000282806776157704

- Fan, J. P. H., Wong, T. J., & Zhang, T. (2007). Politically connected CEOs, corporate governance, and post-IPO performance of China’s newly partially privatized firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 84, 330–357. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2006.03.008

- Fisman, R. (2001). Estimating the value of political connections. American Economic Review, 91, 1095–1102. doi:10.1257/aer.91.4.1095

- Frye, T., & Shleifer, A. (1997). The invisible hand and the grabbing hand. American Economic Review, 87, 354–358.

- He, C., Huang, Z., & Wang, R. (2014). Land use change and economic growth in urban China: A structural equation analysis. Urban Studies, 51, 2880–2898. doi:10.1177/0042098013513649

- He, C., Zhou, Y., & Huang, Z. (2016). Fiscal decentralization, political centralization, and land urbanization in China. Urban Geography, 37, 436–457. doi:10.1080/02723638.2015.1063242

- He, C. F., & Zhu, S. J. (2007). Economic transition and industrial restructuring in China: Structural convergence or divergence? Post-Communist Economies, 19, 317–342. doi:10.1080/14631370701503448

- Huang, Z., Wei, Y. D., He, C., & Li, H. (2015). Urban land expansion under economic transition in China: A multi-level modeling analysis. Habitat International, 47, 69–82. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.01.007

- Huang, Z. H., & Du, X. J. (2016). Strategic interaction in local governments’ industrial land supply: Evidence from China. Urban Studies. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/0042098016664691

- Jiang, L., Deng, X., & Seto, K. C. (2012). Multi-level modeling of urban expansion and cultivated land conversion for urban hotspot counties in China. Landscape and Urban Planning, 108, 131–139. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.08.008

- Lai, Y., Peng, Y., Li, B., & Lin, Y. (2014). Industrial land development in urban villages in China: A property rights perspective. Habitat International, 41, 185–194. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2013.08.004

- Li, H., Wei, Y. H. D., & Huang, Z. (2014). Urban land expansion and spatial dynamics in globalizing Shanghai. Sustainability, 6, 8856–8875. doi:10.3390/su6128856

- Li, H., Wei, Y. D., Liao, F. H., & Huang, Z. (2015). Administrative hierarchy and urban land expansion in transitional China. Applied Geography, 56, 177–186. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2014.11.029

- Li, H., & Zhou, L.-A. (2005). Political turnover and economic performance: The incentive role of personnel control in China. Journal of Public Economics, 89, 1743–1762. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.06.009

- Lichtenberg, E., & Ding, C. (2009). Local officials as land developers: Urban spatial expansion in China. Journal of Urban Economics, 66, 57–64. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2009.03.002

- Lin, G. C. (2007). Reproducing spaces of Chinese urbanisation: New city-based and land-centred urban transformation. Urban Studies, 44, 1827–1855. doi:10.1080/00420980701426673

- Lin, G. C. (2009). Scaling-up regional development in globalizing China: Local capital accumulation, land-centred politics, and reproduction of space. Regional Studies, 43, 429–447. doi:10.1080/00343400802662625

- Lin, G. C., & Ho, S. P. (2003). China’s land resources and land-use change: Insights from the 1996 land survey. Land Use Policy, 20, 87–107. doi:10.1016/S0264-8377(03)00007-3

- Lin, G. C., & Ho, S. P. (2005). The state, land system, and land development processes in contemporary China. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 95, 411–436. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.2005.00467.x

- Lin, G. C., Li, X., Yang, F. F., & Hu, F. Z. (2014). Strategizing urbanism in the era of neoliberalization: State power reshuffling, land development and municipal finance in urbanizing China. Urban Studies, 52, 1962–1982. doi:10.1177/0042098013513644

- Lin, G. C., & Yi, F. (2011). Urbanization of capital or capitalization on urban land? Land development and local public finance in urbanizing China. Urban Geography, 32, 50–79. doi:10.2747/0272-3638.32.1.50

- Lin, N. (2002). Social capital: A theory of social structure and action (Vol. 19). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Liu, M., Tao, R., Yuan, F., & Cao, G. (2008). Instrumental land use investment-driven growth in China. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 13), 313–331. doi:10.1080/13547860802131300

- Liu, W. D., & Deng, Z. H. (2008). Study on the rational determination of the standard of industrial land prices. Journal of Zhejiang University (Humanities and Social Sciences), 4, 146–153 (Original in Chinese)

- Luo, J., & Wei, Y. D. (2009). Modeling spatial variations of urban growth patterns in Chinese cities: The case of Nanjing. Landscape and Urban Planning, 91(2), 51–64. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2008.11.010

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2005a). China Annual Survey of Industrial Firms 2005. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2005b). China City Statistical Yearbook 2005. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2005c). China Land and Resources Statistical Yearbook 2005. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2005d). China Statistical Yearbook 2005. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2005e). China Statistical Yearbook for Regional Economy 2005. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2006a). China Annual Survey of Industrial Firms 2006. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2006b). China City Statistical Yearbook 2006. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2006c). China Land and Resources Statistical Yearbook 2006. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2006d). China Statistical Yearbook 2006. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2006e). China Statistical Yearbook for Regional Economy 2006. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2007a). China Annual Survey of Industrial Firms 2007. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2007b). China City Statistical Yearbook 2007. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2007c). China Land and Resources Statistical Yearbook 2007. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2007d). China Statistical Yearbook 2007. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2007e). China Statistical Yearbook for Regional Economy 2007. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2008a). China Annual Survey of Industrial Firms 2008. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2008b). China City Statistical Yearbook 2008. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2008c). China Land and Resources Statistical Yearbook 2008. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2008d). China Statistical Yearbook 2008. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2008e). China Statistical Yearbook for Regional Economy 2008. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2009a). China Annual Survey of Industrial Firms 2009. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2009b). China City Statistical Yearbook 2009. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2009c). China Land and Resources Statistical Yearbook 2009. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2009d). China Statistical Yearbook 2009. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2009e). China Statistical Yearbook for Regional Economy 2009. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press.

- Ping, Y. C. (2011). Explaining land use change in a Guangdong county: The supply side of the story. The China Quarterly, 207, 626–648. doi:10.1017/S0305741011000683

- Portes, A. (2000). Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. In E. L. Lesser (Ed.), Knowledge and social capital (pp. 43–67). Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Qian, Y., & Weingast, B. R. (1996). China’s transition to markets: Market-preserving federalism, Chinese style. The Journal of Policy Reform, 1, 149–185. doi:10.1080/13841289608523361

- Seto, K. C., & Kaufmann, R. K. (2003). Modeling the drivers of urban land use change in the Pearl River Delta, China: Integrating remote sensing with socioeconomic data. Land Economics, 79, 106–121. doi:10.2307/3147108

- Smith, A. (2002). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. In N. W. Biggart (Ed.), Readings in economic sociology (pp. 6–17). Malden, MA: Blackwell. (Original work published 1776)

- Song, W. (2014). Decoupling cultivated land loss by construction occupation from economic growth in Beijing. Habitat International, 43, 198–205. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.03.002

- Tao, R., Su, F., Liu, M., & Cao, G. (2010). Land leasing and local public finance in China’s regional development: Evidence from prefecture-level cities. Urban Studies, 47, 2217–2236. doi:10.1177/0042098009357961

- Tao, R., & Wang, H. (2010). China’s unfinished land system reform: Challenges and solution. International Economic Criticism, 2, 93–123 (Originalin Chinese)

- Thun, E. (2004). Keeping up with the Jones’: Decentralization, policy imitation, and industrial development in China. World Development, 32, 1289–1308. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.02.007

- Tian, L., & Ma, W. (2009). Government intervention in city development of China: A tool of land supply. Land Use Policy, 26, 599–609. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.08.012

- Tu, F., Yu, X., & Ruan, J. (2014). Industrial land use efficiency under government intervention: Evidence from Hangzhou, China. Habitat International, 43, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.01.017

- Wang, J., Chen, Y., Shao, X., Zhang, Y., & Cao, Y. (2012). Land-use changes and policy dimension driving forces in China: Present, trend and future. Land Use Policy, 29, 737–749. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.11.010

- Wei, Y. D., & Ye, X. (2014). Urbanization, urban land expansion and environmental change in China. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment, 28, 757–765. doi:10.1007/s00477-013-0840-9

- Wu, Y., Zhang, X., Skitmore, M., Song, Y., & Hui, E. C. M. (2014). Industrial land price and its impact on urban growth: A Chinese case study. Land Use Policy, 36, 199–209. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.08.015

- Yang, D. Y. R., & Wang, H. K. (2008). Dilemmas of local governance under the development zone fever in China: A case study of the Suzhou region. Urban Studies, 45, 1037–1054. doi:10.1177/0042098008089852

- Zhu, J. (1994). Changing land policy and its impact on local growth: The experience of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone, China, in the 1980s. Urban Studies, 31, 1611–1623. doi:10.1080/00420989420081541