?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In the literature on urban studies, the size distribution of cities has been attributed to a random growth process where transportation externalities, congestion costs, and capital formation all play a crucial role. However, the classic economics models do not fully capture the impact of political institutions, particularly fiscal decentralization, on urban size distribution and fail to explain the political economy of urban agglomeration. As a major transitional economy, China’s economic decentralization, in conjunction with political control, portends a more complex environment for urban agglomeration and offers a new ground to analyze its institutional roots and policy implications. This study employs a panel data analysis of Chinese provinces between 1994 and 2015 and finds a pattern where more decentralized regions (provinces) are associated with stronger dominance of large cities for the whole study period. However, the period between 1994 and 2003 displays a different pattern wherein fiscal decentralization is negatively associated with urban agglomeration. Such phenomena can be attributed to the heated competition among local governments and the absorption of resources by dominant cities under the framework of fiscal decentralization in China, particularly in the recent years. More effective coordination is called upon to mitigate the unintended outcome of fiscal decentralization without proper control in shaping urban hierarchy in China and the findings provide lessons for other developing countries.

Introduction

As a rapidly urbanizing country, China has faced an insuppressible rise of megacities and agglomerated urbanized regions. Core cities throughout China have grown disproportionally larger compared to other cities within the region. In other developing countries, urban agglomeration has occurred as well. Therefore, we aim to explore the factors affecting agglomeration in the Chinese context. In particular, we attempt to investigate the impact of political institutions such as fiscal decentralization on urban size distribution.

The Chinese government has carried out waves of national planning policies to coordinate this trend of urban agglomeration. The Five-Year Plan is considered the most powerful tool to guide growth and development in China. Starting at the third and fourth Five-Year Plans (1966–1975), the national government mandated the strategy of controlling the scale of large cities and encouraging small-city development. Such a strategy continued through the ninth Five-Year Plan (1995–2000). In the 1980s and 1990s, the national planning apparatus tightly controlled the expansion of large cities. For instance, the central government’s Minutes of the National Urban Planning Working Meeting announced in 1980 the policy of “controlling the scale of large cities, reasonably developing medium-size cities and actively developing small cities” (National People’s Congress, Citation1989). Such a tight control worked through the 1990s, but China continued to witness the emergence of mega urban regions.

It was not until the 2000s that the national government no longer prohibited the growth of megacities. The 10th Five-Year Plan (2000–2005) proposed for the first time a balanced development of large, medium, and small cities in China. Since then, the important function of large cities in leading national development has been increasingly realized (Fang, Citation2014). The 2008 Urban and Rural Planning Law formally gave up the “controlling the scale of large cities” policy. The latest National New Urbanization Plan 2014–2020 formally adopted the policy of “enhancing the function of the core cities, expediting the growth of medium and small size cities, focusing on developing small towns, in order to promote the coordinated development of cities and towns.” It shows that the trend of urban agglomeration has become a significant feature of China’s urbanization, not only in the absolute size but also in the relative concentration of population, economies, and activities in large cities.

In 2011, China announced that it was going to make the world’s biggest mega urban cluster by housing 42 million people in Guangdong Province. About 150 major infrastructure projects costing 2 trillion yuan will be put in place to connect the existing nine cities together with integrated transport, telecommunication networks, and water systems (“China to Create Largest Mega City in the World With 42 Million People,” Citation2011). The National Development and Reform Commission proposed developing 10 megaregions in the country, which would cover about 20% of the total area and half of national population. Unfortunately, the 10 megaregions are not developed evenly around the country but dominated by a limited number of major cities that are not geographically far away from each other, especially in the two most important regions: the Yangtze River Delta region and the Pearl River Delta region (Yang, Song, & Lin, Citation2014). This has led to a series of problems related to urban planning and development, such as long-lasting traffic congestion in megaregions, skyrocketing property prices, and worsening environmental problems, to name a few. Critics point out that China is not managing urban growth wisely because it has not utilized the advantages of the megaregions but instead is amplifying the related ills of massive metropolises (Quartz, Citation2014). Within a province, two to three cities have grown dramatically over the past few decades. Economic activities have been concentrated in these megacities while other cities starve of financial and human resources. Questions naturally arise. Why does a province have (or encourage) a dominance of large cities? What drives this pattern? In addition to resource endowments, are there any institutions at work in determining urban agglomeration in the Chinese context?

Tackling these questions, this study offers a new angle to study the driving forces of urban agglomeration from a political economy perspective. The article is organized as follows. The classic urban economics literature on urban size distribution is reviewed, followed by an in-depth discussion of the ongoing fiscal decentralization in China and its impact on urban growth patterns. The centralized system of governments in China is taken into careful consideration to develop an analytical model to explain the causal relations between fiscal decentralization and urban agglomeration. Panel data analyses of Chinese provinces between 1994 and 2015 are then developed to empirically test the research hypotheses and answer the research questions. Qualitative discussion follows the statistical analysis to further explain the urban hierarchy in China and how this may relate to other developing and developed countries in the world. Policy discussion and implications are offered at the end.

Fiscal decentralization and urban agglomeration

The process of urban agglomeration, which leads to urban primacy and the dominance of large cities, has been a heavily debated topic in the classic urban studies literature. First, agglomeration as an independent variable, as raised by Alfred Marshall 100 years ago, has been depicted as a driver of urban growth and productivity (Guimaraes, Figueiredo, & Woodward, Citation2000). The literature that seeks to explain urban growth in both developed and developing country contexts has boomed in this area. Second, urban agglomeration as a dependent variable has received less attention compared with the first case. Nevertheless, it has been accorded greater importance recently as urban agglomeration has been associated with productivity, congestion, inequality, etc. The traditional model of economic growth realized that as the urbanization process advances, cities tend to grow bigger, at least in the early stage of urban development. Such patterns have been investigated by several cross-country economic development studies (Ades & Glaeser, Citation1995; Henderson, Citation2003; Wheaton & Shishido, Citation1981; Williamson, Citation1965). Continuous efforts have been made to identify the key factors that contribute to the growth of cities and the tendency of urban agglomeration. On the one hand, economic factors—including transportation, capital investment, and human resources—are considered decisive in the early formation of giant cities. Agglomerated urban regions provide necessary nodes for technological advancement, firm clustering, and social development. Williamson (Citation1965) suggests that “agglomeration matters most at early stages of development. When transportation and communication infrastructure are scarce and the reach of capital markets is limited, efficiency can be enhanced by concentrating production in space” (p. 4). In the long run, due to the expansion of transportation infrastructure and the reduction in shipping costs, urban resources would be decentralized from a primate city to surrounding areas (Brülhart & Sbergami, Citation2009; Davis & Henderson, Citation2003; Hansen, Citation1965).

On the other hand, it has been argued that institutional arrangements, in particular national political institutions, affect the degree of urban concentration. Overconcentration of resources in a few cities and the expansion of these cities may be encouraged by political institutions and policies that favor a very few number of dominant cities due to a variety of reasons, such as political considerations for developing power bases in these cities or the historical advantages that these cities possess. Such phenomena have been observed more frequently in developing countries, often occurring in national capitals, such as Bangkok, Mexico City, and Jakarta, or historically elite cities, such as São Paulo or Shanghai (Behrens & Bala, Citation2013; Henderson & Becker, Citation2000; Henderson & Kuncoro, Citation1996; Moomaw & Shatter, Citation1996).

However, limitations in the existing literature must be recognized. First of all, most studies employed national data and examined urban agglomeration at the national scale, taking the entire nation as one unit of analysis in cross-country studies. As a matter of fact, in many countries of the world, multiple urban centers exist and no single city is able to dominate the national development agenda (Savitch, Gross, & Ye, Citation2014; Xu & Yeh, Citation2010). For instance, China has established over a dozen urban regions across the country and designated several “national core cities,” including Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Chongqing. This list is about to expand to include additional cities to lead multicentric urban cluster development in the country. All of these core cities are centers for large and continuous urban regions, each of which has significantly varying policy frameworks and implementation schemes (Ye, Citation2013, Citation2014). As the development of urban regions has become the typical form of urbanization worldwide, it is necessary to perform a subnational analysis to better study these regional clusters.

Second, most institutional factors examined in the existing literature were national political institutions and development policies. Subnational political institutions, which are gaining importance in today’s decentralized world, have not been carefully taken into consideration in analyzing their impacts on urban agglomerations. In fact, subnational governments and policies play a crucial role in affecting local economic activities, urban planning and development, and environmental management, especially in developing countries like China (Jia, Guo, & Zhang, Citation2014; Leong & Lejano, Citation2016; Walder, Citation1995; Zhang, Citation2013). Importantly, institutional variations at the subnational level, especially in fiscal decentralization, will reveal more interesting interactions among different players who substantially shape local development.

Therefore, it is necessary to study political institutions such as fiscal decentralization at the subnational level and how they affect urban agglomeration. Empirically, the findings in the existing literature are rather divided as to whether fiscal decentralization has a positive or negative impact on urban growth and development. In early theories of fiscal decentralization, it was considered beneficial toward public goods provision and economic growth. In effect, governments closer to their constituents have better information about people’s preferences and tastes. The fiscal power granted to local governments can facilitate a good match between the needs of local constituencies and supplies of the government. The hierarchical, bureaucratic system distorts the flow of information from below to above. Therefore, decentralization more often than not should be favored (Cai & Treisman, Citation2006; Jin, Qian, & Weingast, Citation2005; Oates, Citation1999; Tiebout, Citation1956).

Some literature points out the complexities of the impacts of fiscal decentralization. For example, Lin and Liu (Citation2000) suggest that local authorities may not have sufficient incentives to learn the preferences of the constituents and respond to the demands at the constituent level. In addition to weak information disclosure, Bardhan (Citation2002) notes, “voting with feet” may not be applicable in some developing countries, because constituents are bound to their land or towns for various reasons. Therefore, fiscal decentralization may not benefit public goods provision and economic growth in the long run. According to Davoodi and Zou (Citation1998), fiscal decentralization negatively affects economic growth in developing countries but positively affects economic growth in developed economies. Drawing on the data of 23 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries between 1982 and 2000, Lessmann (Citation2009) suggests that decentralization has a significant association with regional disparities.

In China, fiscal decentralization and its impact on development issues have garnered wide attention in recent years. It is suggested that fiscal decentralization in China contributed to regional disparities and enlarged intraprovincial gaps in fiscal capacity (Li, Citation2018) and economic performance (Liu, Martinez-Vazquez, & Wu, Citation2017; see also Uchimura & Jutting, Citation2007). The rationale behind this is as follows: local governments as rational actors tend to concentrate their resources on richer regions to have positive economic growth in a given period, which tends to favor development in these richer regions. Poorer regions are in a weaker position in attracting both talent and investment, whether domestic or foreign (Prud’homme, Citation1995). Moreover, expenditure decentralization increases government spending and leads to the spending allocation with a greater weight on capital construction, which eventually contributes to larger cities (Jia et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, politically, rich regions tend to be influential with regard to decision making on regional development and other related matters. More often than not, richer regions receive more resources from higher authorities (Rodríguez-Pose & Ezcurra, Citation2010); therefore, preexisting disparities would be strengthened. For example, in the Chinese central government’s decision making, some rich provinces like Guangdong have a greater influence due to the national political structure that favors them (the party secretary of Guangdong Province usually is a member of the Politburo, the highest decision-making body in China). Although the Chinese government has claimed to narrow interregional gaps, decentralization has not addressed the problem but instead has led to the concentration of resources in some rich areas (Zhang, Citation2006). In a similar vein, some top cities may have more power, possess more resources, and spend more public money than smaller cities and therefore urban agglomeration increases.

Based on the previous literature, which was more focused on economics analysis, this study tackles the issue related to urban agglomeration under the structure of fiscal decentralization, which appears in the developing country contexts. Moving from some literature particularly on the relationships between fiscal decentralization and regional disparity, we advance the understanding of the impact of fiscal decentralization on urban agglomeration, which is more complex than expected in the extant literature. For instance, Liu et al. (Citation2017) point to the effectiveness of central transfers and the issue related to decentralization and income inequality, hypothesizing the impact of fiscal decentralization on regional inequality and the role of fiscal equalization policies on mitigating regional income inequality. Our study is situated in urban studies literature and proposes that through a concentration of economic resources in a few important locations, fiscal decentralization will facilitate and reinforce urban agglomeration. In addition, we emphasize the political motivation of local leaders in the Chinese context, which is similar in other transitional economy contexts. Furthermore, we find complex results with regard to the impact of decentralization on urban agglomeration (Ye & Wu, Citation2014). Therefore, this study intends to offer policy implications not addressed by the extant literature on the relationships between fiscal decentralization and urban agglomeration.

In this regard, we assume that a decentralized fiscal system tends to favor big cities thanks to fierce intercity competition and the high degree of concentration of resources, population, and economic activities. Chinese cities are in heated competition between each other, due to the drive for attracting investment and capital and boosting economic growth, with local governments acting like industrial firms (Walder, Citation1995). At the same time, provincial governments (intermediate governments) in China are under pressure to mitigate interregional disparities by carrying out regionwide policies (Liu et al., Citation2017). It is intriguing to find out whether fiscal decentralization would encourage urban agglomeration or vice versa at the subnational, regional level and whether or not the pattern is consistent with other experiences such as those in transitional countries.

The contribution of our study to the current literature is multifaceted. First, for the first time, a panel data analysis has been applied to investigate the determinants of urban agglomeration, especially through looking into the role of fiscal decentralization, which features the most crucial characteristics of the political and economic structure in China’s intergovernmental system. We argue that based on a panel data analysis capturing the cross-section and time-series dimensions urban agglomeration at the subnational level, this study offers an accurate and unbiased investigation of the relationship between fiscal decentralization and urban agglomeration in the Chinese context.

Second, in addition to the typical panel data analysis methods like fixed and random effects analyses and two-stage least squares (2SLS) models, we employ rigorous tests like generalized method of moments (GMM) estimates to isolate possible intervening factors and specify the causal relation between fiscal decentralization and urban agglomeration. With a variety of empirical tests, this study endeavors to investigate whether, how, and why fiscal decentralization affects the phenomenon of urban of agglomeration and the rise of megacities in China.

Before we embark on research design and methodology, the structure of the Chinese government deserves a note. The Chinese government consists of five tiers of government: central, provincial, prefectural, county, and township. According to the China Statistical Yearbook (Citation2015), subnational governments refer to 31 provincial-level governments in the mainland, 333 prefectural governments, 2,854 county-level governments (including counties, county-level cities and district governments in the urban area), and 40,381 township governments. Though it is a constitutionally unitary country, China is fiscally decentralized, especially on the expenditure side. The 1994 tax and revenue sharing system grants the central government a great role in extracting financial resources. The stable, lucrative taxes have been claimed by the central government for its own treasury (Feng, Ljungwall, Guo, & Wu, Citation2013).

Under the existing intergovernmental fiscal framework, the State Council provides detailed rules on fiscal decentralization. The central government can collect substantial revenues, whereas local governments (including provincial, prefectural, county, and township governments) have to cope with a growing demand for public services and an escalated increase in the price of public goods. Therefore, compared with local governments in China, over the past two decades the extractive capacity of the central government rose substantially, imposing a tremendous financial burden at the subprovincial level. This is because local governments in China provide the bulk of public services to local constituents, whereas about 70% of public expenditure is handled by subnational governments and 55% by subprovincial governments (World Bank, Citation2002). Such intergovernmental fiscal relations have been argued to affect many aspects of urban development in China, including regional collaboration (Ye, Citation2014), spatial inequality (Zhang, Citation2006), rural–urban interaction (Yang & Wu, Citation2016), local capture (Wu, Citation2013), and so on. With significant variations in both inter- and intraprovincial decentralization (Liu et al., Citation2017; Wu & Wang, Citation2013), it remains an intriguing question whether or not the variation in expenditure decentralization across provinces has an impact on urban agglomeration.

To fully tackle the research question, this study postulates that, in the Chinese context, the degree of fiscal decentralization in a region (notably a province) affects the degree of urban agglomeration. The more decentralized the intergovernmental relations in a province, the higher the degree of agglomeration that will occur. Large cities are likely to dominate under the decentralized subnational intergovernmental relations in the Chinese context. Therefore, the research hypotheses are as follows:

H1:

A higher degree of fiscal decentralization leads to a higher degree of urban agglomeration.

H0:

The degree of fiscal decentralization does not affect the degree of urban agglomeration.

Data analysis

This study tests the hypotheses by analyzing the panel data in China from 1994 to 2015. In 1994, China launched a major tax sharing reform that fundamentally altered the financial relations between central and subnational governments. First, two tax bureaus (national and local) were set up to collect central taxes and local taxes, respectively, until the most recent merging of the two tax bureaus into a single bureau in 2018 (all tax rates were determined by the central government). Second, the tax to GDP ratio has increased substantially and the share of central revenue to total venue has increased dramatically. It has made a sea change on China’s central–local fiscal relations. Therefore, the year 1994 was chosen as the starting point of analysis. Data analyses investigate the relations between fiscal decentralization and urban agglomeration at the subnational level in China.

Dependent variable

Urban agglomeration is measured by a modified urban agglomeration index to demonstrate the degree of megacity concentration within a province, taking into consideration China’s multicentric regional development model and demographic and economic data availability. The adjusted formula for the urban agglomeration (UA) index used in this study is

In the formula, Ai represents the GDP of any given city in a province. The total number of cities in a province is denoted N where n indicates the number of top cities in the province. IC represents a typical industrial concentration index method to measure the dominance of top units in the entire industry (top cities in the entire province in this case). However, the calculation of such an index is more useful when dealing with less variation in the number of total firms or cities in a region, but provinces in China have quite different numbers of prefecture-level cities, usually ranging from fewer than 10 to more than 20. Proportion P indicates the ratio of the number of top cities and the total number of cities in a province. It is argued that such a ratio affects the validity of the concentration index when it is applied to urban agglomeration. Therefore, a modified urban agglomeration (UA) index is adjusted by IC/P in the final formula. A similar proportional index is used in a large body of economics literature to measure urban agglomeration (Davis & Henderson, Citation2003; Gabaix, Citation1999; Rosen & Resnick, Citation1980). Such a modified index provides a suitable proxy of urban agglomeration in China.

The adoption of this index takes into consideration both economic theories and the practical conditions in China. For instance, the traditional Jefferson’s rule and Zipf’s law only calculate the largest city’s population share in the country (Jefferson, Citation1939). In the Chinese case, each province tends to have two or three core cities to lead regional economic growth. Therefore, n is taken as 2 in the following statistical analysis.Footnote1 It is worth noting that the ratio of total population in core cities to all cities in a region seems to be a good indicator measuring urban agglomeration. However, existing population statistics in China about permanent residents (changzhu renkou) and residents with household registration (huji renkou) have serious problems. Many cities only count the number of residents with household registration and those permanent residents who have resided in the city for more than 6 months during the past year. The vast majority of the migrant population is not included in such population statistics. In addition, many cities and provinces did not start publishing population statistics for their permanent residents until the last decade, which makes longitudinal demographic studies more difficult. For all of these reasons, this study uses the proportional economic output data produced by the top cities to measure the degree of urban agglomeration. Whether the economic output is highly correlated with demographic data in any given geographic area has been tested and supports the adoption of GDP as the primary indicator of the dependent variable.

Independent variable

The main independent variable is the level of intraprovincial fiscal decentralization, measured by the ratio of expenditure at the subprovincial level, including prefectural, county, and township governments, to that of the entire province (see Wu & Wang, 2013). This type of decentralization reflects the political economy of intergovernmental relations in a given province. A higher ratio indicates a more decentralized fiscal relation in a given province. In China, the 1994 tax sharing reform only governs the relationship between the central and provincial governments. Subprovincial intergovernmental arrangements are left to the discretion of individual provinces, especially on the expenditure side. Therefore, expenditure decentralization varies substantially across provinces (Wu & Wang, Citation2013). Subprovincial fiscal relations affect local governments’ spending behavior on both public goods provision and economic development. According to Jia et al. (Citation2014), expenditure decentralization brings more spending on capital construction and less on education. Because capital spending and infrastructure development are fundamental to economic growth, it is hypothesized that fiscal decentralization, especially on the expenditure side, leads local governments to enlarge the dominance of large cities.

Control variables

A set of control variables is included as explained below. The selection of the control variables is based on literature review and data availability.

Economic structure

A modern economic structure contributes significantly to urban agglomeration and the growth of primate cities because these cities provide necessary concentration of economic activities and technological advancement (McGrath, Citation2005). We hypothesize that more advanced economic structures with higher shares of secondary and tertiary industries would push for a higher degree of urban agglomeration. This variable is measured by the share of the secondary industry in the total GDP and the share of the tertiary industry in the total GDP in a given year in a given province.

Transportation network

Basic infrastructures like roads provide hinterland regions with an interregional transportation network and connection to domestic and global markets, which might reduce the power of the primate city (Gallup, Sacks, & Mellinger, Citation1999). With more mature transportation networks, cities in a region tend to develop more evenly. We hypothesize that transportation networks reduce urban agglomeration in a province. This variable is measured by the length of roads per square kilometer in a given year in a given province.

Foreign investment dependence

The flow of foreign capital and investment reflects both a location’s capability to develop and its comparative advantages in economic competition (Wheaton & Shishido, Citation1981). More evenly distributed foreign direct investment across regions and cities would lower the degree of urban agglomeration. Some assume an opposite direction. Foreign investments tend to locate in bigger cities in order to tap into human resources and others, thereby resulting in greater urban agglomeration. We preliminarily hypothesize this variable to be negatively related to urban agglomeration because small cities nowadays offer more incentives to attract foreign direct investment. This variable is measured by the share of the total investment of foreign funded enterprises to the total GDP in a given year in a given province.

Export dependency

Studies have found that export dependency has a complex effect on urban agglomeration, either positive or negative (Mutlu, Citation1989; Rosen & Resnick, Citation1980). For example, higher export dependency may enhance urban agglomeration because export requires logistical support and human resource investment, which in turn demand a certain level of concentration of resources geographically. We hypothesize that this variable is positively related to the degree of urban agglomeration although acknowledging that the relationship could be complicated. This variable is measured by the ratio of export volume to the total GDP in a given year in a given province.

Labor force

As labor force can drive economic expansion and contribute to GDP growth, we assume that there is a positive relationship between labor force distribution and urban agglomeration. In the Chinese context, the labor force is usually concentrated in the core cities or regions. Therefore, it is hypothesized that labor force distribution will interact with the concentration of economic resources in top cities. This variable is measured by share of the labor force as a percentage of permanent residents in a given year in a province.

Fiscal independence is also included. We measure it using the ratio of budgetary revenue to budgetary expenditure. The fiscal situation of a given province will affect government activities and economic activities in general; therefore, fiscal independence may impact urban agglomeration. In addition to the above variables, we include the share of fixed asset investment in GDP and the permanent population as structural factors contributing to urban agglomeration.

summarizes the variables, measurements, and data sources. lists the descriptive statistics. It can be seen that between 1994 and 2015, subprovincial governments spent from 21% to 93% of total provincial budgets, recording a wide variation across the country. Other variables tend to vary to a certain degree, which depicts the different situations in the provinces in China.

Table 1. Measurement and data sources.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics, 1994–2015.

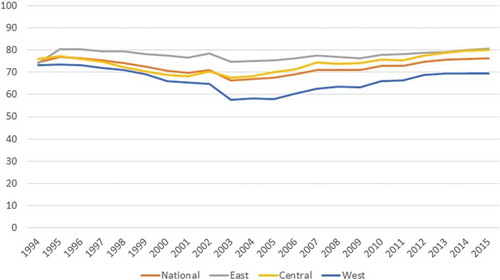

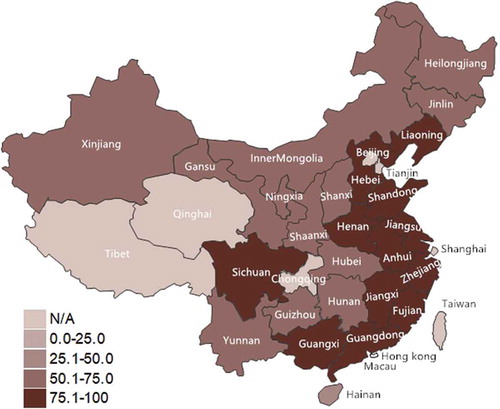

shows the average index of intraprovincial expenditure decentralization in China from 1994 to 2015, excluding four centrally administered cities of Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Chongqing; the Tibet Autonomous Region; Qinghai ProvinceFootnote2; and the special administrative regions (SARs). It can be seen that the eastern coastal areas had more decentralized intergovernmental fiscal relations, with more spending power delegated to the subprovincial level, including prefectural, county, and township governments. The northeast, central, and western regions had more financial resources at the provincial governments’ hands. Nevertheless, it is not a clear-cut pattern. For example, in central China, Sichuan had a relatively high intraprovincial fiscal decentralization.Footnote3

Figure 1. Expenditure decentralization by province in China, 1994–2015. Notes. 1. Colors and numbers indicate average expenditure decentralization at the provincial level between 1994 and 2015. 2. Data on centrally administered cities and SARs are excluded. 3. Some inland provinces also decentralized a substantial share of expenditure to local governments, which deserves exploration in another paper.

suggests regional variations in the change of expenditure decentralization between 1994 and 2015. During this period, the figure went up in most provinces except Heilongjiang, Shaanxi, Shanxi, and Xinjiang. Provinces in the eastern regions usually delegated around 80% of the spending to subprovincial governments, including both prefecture and county levels, where the provinces in the western region delegated less.

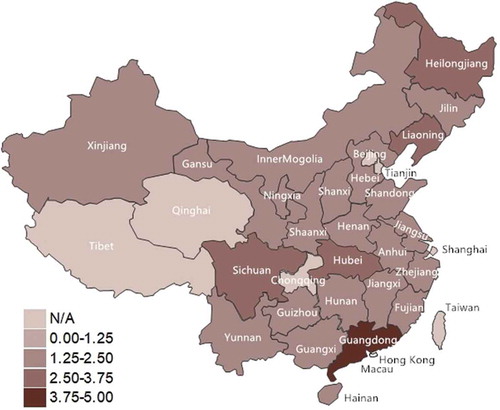

Figure 3. Urban agglomeration by province in China, 1994–2015. Notes. 1. Colors and numbers indicate expenditure decentralization at the provincial level. 2. Data on centrally administered cities and SARs are excluded.

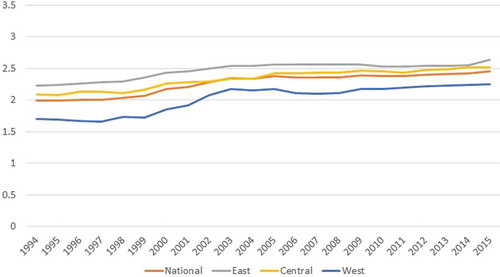

shows the average urban agglomeration scale in China between 1994 and 2015, where most provinces witnessed an increasing level of agglomeration, except Shanxi, Yunnan, Tibet, and Qinghai. With regard to regional variation over these years, the provinces in the eastern region had slightly higher degrees of urban agglomeration. As a more advanced area in China, the eastern region has a higher degree of integration into the global economy, which provides a solid foundation for the formation of mega urban regions (Ye, Citation2013, Citation2014).

demonstrates that almost all regions experienced an increasing urban agglomeration between 1994 and 2015, most significantly between the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s.

Estimation methodology

Panel data models are used in this study. Based on the assumption that the random effects do not correlate with the random error, random effects models usually are more efficient. Nevertheless, in our study, the Hausman test suggests that fixed effects models should be preferred. The province fixed effects and the year fixed effects have been included. shows the baseline results. Model 1 suggests that fiscal decentralization is significantly positively related with urban agglomeration. A one percentage point increase in fiscal decentralization is associated with a 0.078% increase in urban agglomeration. Given that fiscal decentralization may have lag effects, we include one- to two-period lagged values of fiscal decentralization, and the results remain almost the same in most models.

Table 3. Fixed effects modelsa.

Endogeneity may exist in the models. For example, urban agglomeration as the ratio of the GDP of large cities to the total GDP of the province may have an impact on labor force distribution. The relationship between GDP and labor force has been well documented. According to Wooldridge (Citation2009), endogeneity results in biased and inconsistent coefficient estimates. We run 2SLS and difference GMM estimations, because two-period lags of labor force distribution are treated as instruments. The instruments we use in the 2SLS estimation pass the weak instrument test and overidentification test (Hayashi, Citation2000; Stock & Motohir, Citation2005). The p values of the Hansen tests for overidentifying restrictions are above .5. The Arellano-Bond autoregressive (AR) (2) tests (insignificance) suggest no autocorrelation of the second order. The validity of difference GMM estimation has been supported.

As shown in , the 2SLS results regarding the relationship between fiscal decentralization and urban agglomeration remain almost the same as those of the baseline models. The coefficient of labor force distribution is positive and significant.

Table 4. Two-stage least squares modelsa.

shows the difference GMM estimation results. The results confirm the significantly positive relationship between fiscal decentralization and urban agglomeration. According to and , the degree of decentralization declined during 1994–2001, whereas the degree of urban agglomeration increased during the same time period. In order to further explore the reason for this change, we divided the study time period into two stages of 1994–2003 and 2004–2015 to see whether the relationship between those two variables varies.

Table 5. Difference GMM modelsa.

It suggests a different pattern compared with the analysis using the data between 1994 and 2015 (see ). In the period between 1994 and 2003, the relationship between fiscal decentralization and urban agglomeration was significantly negative, whereas the relationship was positive in the period from 2004 to 2015. This indicates a complex situation. As stated above, the Chinese government did not support the development of large cities until the 2000s. Such a national strategy limited urban agglomeration before 2003. In the meantime, fiscal decentralization has continued (on average, all subnational governments have enhanced their expenditure shares within their jurisdictions). Therefore, expenditure decentralization started to impact urban agglomeration positively after the national government encouraged the growth of large cities over smaller cities. This suggests that expenditure decentralization through offering local governments spending responsibilities could enhance the concentration of economic resources in core cities. This result may not be the intended outcome of large cities policy in China. However, it appears that fiscal decentralization has played its role in the concentration of economic resources in a small number of cities because the politico-economic situation in China has facilitated the process. displays the different fixed effects estimation results of the two time periods.

Table 6. Fixed effects modelsa.

Findings and implications

The statistical analyses in this article find that with more decentralized fiscal relations between the provincial and subprovincial governments, the level of urban agglomeration tends to rise when it is allowed by the central government. More decentralized intergovernmental arrangements favor well-developed cities where the investment will have better returns and good outputs. The pressure for growth becomes the invisible hand behind the strong trend of urban agglomeration in China. Nevertheless, this study also observes a different pattern using the data between 1994 and 2003. It indicates a complex situation with regard to the impact of expenditure decentralization on the concentration of economic resources in top cities.

Larger cities enjoy favorable competitive advantages in the more decentralized framework and become more dominant in the urban network in China, particularly in the recent decade. The political economy behind such phenomena lies in that Chinese cities are not equal with regard to their political and administrative resources. For instance, cities like Guangzhou and Shenzhen possess far stronger powers than other cities in Guangdong Province. These two cities can sometimes obtain support even from the national government for their aggressive economic growth and urban development, which might come at the expense of other cities in the region. Furthermore, intergovernmental fiscal relations enhance the possibility of concentrating economic resources in such powerful cities in the Chinese context. Fiscal decentralization is posited to enhance local public governance and to some extent improve balanced regional development through yardstick competition.Footnote4 Nevertheless, in the Chinese context, fiscal decentralization breeds urban agglomeration and spurs the growth of big cities. The statistical findings provide a new angle to examine decentralization policies in the developing part of the world.

Lessons have to be learned for some developing countries that are undergoing rapid urbanization. As discussed earlier in this article, according to the Williamson’s hypothesis, “agglomeration promotes growth at early stages of development but has no, or even detrimental, effects in economies that have reached a certain income level” (Williamson, Citation1965, p. 4). Bertinelli and Black (Citation2004) further established “the model of urbanization and growth,” which states that the gain of agglomeration would diminish when the cost of static congestion diseconomies continues to rise and the development would be trapped if the region did not take advantages of infrastructure improvement to produce more balanced and dynamic growth.

China is facing the challenge of overconcentrating metropolises, where sprawling cities have made quality of life less desirable for residents due to prolonged commuting time, unaffordable housing prices, and serious environmental threats (Roxburgh, Citation2017). As these megacities grow larger, they occupy an increasingly important position in regional economies. The increasing concentration of primate cities does not secure a more balanced regional development. Andrew and Feiock (Citation2010) point out that “the productive advantages of spatial closeness require intergovernmental coordination and strategies for successful management of urban growth” (p. 494). It is important to recognize the link between the new economic geography in the globalized world and lessons for regional governance in public administration. For instance, Krugman’s core–peripheral economic geography model entails the advantages of economies of scale and the tendency of regional clustering (Krugman & Livas, Citation1996). Nevertheless, a caveat is in order. The economic return of urban agglomeration will diminish as the development process moves forward. Socially and economically, the cost of urban agglomeration will gradually outweigh the benefits in the long run. Therefore, the Chinese government should be cautious about the overgrowth of large cities and its pertinent problems. Based on the experience in other countries, some institutional arrangements such as intergovernmental mechanisms and checks and balances from the bottom up (including the general publicFootnote5) need to be put in place to balance the tradeoffs between urban agglomeration and regional development.

Conclusion

This study contributes to the literature that investigates the theoretical and empirical linkages between political institutions such as fiscal decentralization, socioeconomic factors, and urban geography such as urban agglomeration. Empirical evidence suggests that more decentralized regions (provinces) tend to experience stronger dominance of large cities for the whole study period. It is much more complicated when we break the study period into two stages, because expenditure decentralization went down in the late 1990s and recovered and grew in the early 2000s, likely due to the national strategy against large city formation before the early 2000s. The late 2000s envisaged the concentration of economic resources in large cities under enhanced fiscal decentralization.

Although we do not identify good or bad sides of urban agglomeration, our study points to some policy implications or suggestions for regional development in China and lessons for other developing countries.

Fiscal decentralization associated with urban agglomeration may promote economic and political incentives of local leadersFootnote6; however, we need to acknowledge that in the long run, the demerits of urban agglomeration may outweigh its merits.Footnote7 This echoes what Martinez-Vazquez and McNab (Citation2003, p. 1605) have pointed out: “Unfettered fiscal decentralization is likely to lead to a concentration of resources in a few geographical locations and thus increase fiscal disparities across sub-national governments.” In the end, the peripheries will lose to the cores even though interregional inequality has been a great concern to the Chinese government. Therefore, when higher authorities possess more power, they are able to help mitigate unwanted agglomeration in their jurisdictions. The goal of regional equalization would be better implemented with relatively high spending at the senior governments’ hands, if the senior governments are able to allocate the resources according to regional needs equitably. We are not arguing for fiscal centralization. Rather, we suggest a balance between decentralizing power, empowering local public officials financially, and mitigating economic concentration and economic inequality in the future.

The findings in this article provide policy implications for designing appropriate political institutions such as expenditure decentralization that encourage local autonomyFootnote8 and promote balanced regional development and good geographical distribution of economic resources simultaneously. Decentralization of power needs to be implemented with carefully designed policies to enhance balanced urban development and suitable urban agglomeration. As China further develops, a wise design of fiscal decentralization and geographical development policies is important. A decentralized development strategy with clear direction for balanced regional growth will enable the country to find the desirable urban scale, avoid the unsustainable use of space, and improve quality of life.

Acknowledgments

An earlier edition of the article was presented at the 46th Annual Meeting of the Urban Affairs Association. The usual disclaimer applies.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alfred M. Wu

Alfred M. Wu is an Associate Professor in the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore. His research interests include public sector reform, central–local fiscal relations, corruption and governance, and social protection in Asia. His research has been supported by the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong and the government of Hong Kong’s Central Policy Unit. His articles appear in World Development, Public Choice, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, International Tax and Public Finance, Journal of Urban Affairs, Environment and Urbanization, Social Policy & Administration, and Ageing & Society, among others.

Lin Ye

Lin Ye is a Professor in Center for Chinese Public Administration Research, School of Government at Sun Yat-sen University, China. His research interests lie in urban policy, public administration and regional governance. He published 10 books and over 60 articles in journals including Public Administration Review, American Review of Public Administration, Cities, Social Policy & Administration, Small Business & Economics, Public Money & Management, Chinese Public Administration Review, Journal of Urban Development and Planning, among others.

Hui Li

Hui Li is an Assistant Professor in the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore. Her research interests lie in intergovernmental fiscal relations, local finance and governance, and corruption and development in emerging economies. Some of the topics she has worked on are China’s intra-provincial fiscal disparities and fiscal equalization policies, land finance and land use reforms, and local cadres’ performance and promotion. Her articles appear in Journal of Contemporary China, China: An International Journal, Journal of Urban Affairs, Public Finance and Management, Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, among other outlets.

Notes

1. An n equal to 3 is also tested and most statistical findings remain with little change.

2. Less than two prefecture-level cities in the province in the majority of the period examined in this study.

3. Based on informants in the Sichuan Provincial Fiscal Bureau whom we contacted, the significantly higher expenditure decentralization in the province was due to at least two reasons. One is that a large amount of intergovernmental transfers from the central government is distributed to cities and counties as the provincial government spends less. In addition, Sichuan has over 100 cities and counties, therefore a significant amount of government expenditure is required to support the operation of the subprovincial governments. Some other historical legacies and geographical conditions contribute to the high expenditure decentralization, which is worth investigating in another paper.

4. Caldeira (Citation2012) notes that under a vertical bureaucratic control system, the central government (instead of local constituents in the Western context) pushes local governments to compete with each other.

5. Compared with the Western world, public participation has not played a large role in East Asia’s inclusive growth over the past decades (Chou & Huque, Citation2016). Some efforts need to be made to enhance checks and balances from the bottom up.

6. It should be noted that economic and political incentives of local leaders may be heterogeneous in different localities of China (Gao, Citation2017), which could complicate policy implications of this study. Li (Citation2016) documents that different sources of revenue in local governments led to distinct spending priorities at the local level in China. This means that local leaders could pursue different policy agendas.

7. We do not identify the threshold value of urban agglomeration. Some debates in China do point to the “big city disease,” such as traffic congestion and environmental pollution (see Roxburgh, Citation2017), as widely criticized urban sprawl in North America and some parts of Europe. In the meantime, we also pay attention to the study highlighting too many small cities and too few large cities in China (see Lu & Wan, Citation2014).

8. Autonomy could be meaningful in different contexts. Aoki (Citation2015) investigates autonomy in a work unit such as school. Our study points to autonomy in local governments; therefore, it means that local governments could have their urban planning and economic development policies.

References

- Ades, A., & Glaeser, E. (1995). Trade and circuses: Explaining urban giants. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110, 195–227. doi:10.2307/2118515

- Andrew, S. A., & Feiock, R. C. (2010). Core–peripheral structure and regional governance: Implications of Paul Krugman’s new economic geography for public administration. Public Administration Review, 70, 494–499. doi:10.1111/(ISSN)1540-6210

- Aoki, N. (2015). Institutionalization of new public management: The case of Singapore’s education system. Public Management Review, 17(2), 165–186. doi:10.1080/14719037.2013.792381

- Bardhan, P. (2002). Decentralization of governance and development. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(4), 185–205. doi:10.1257/089533002320951037

- Behrens, K., & Bala, A. P. (2013). Do rent-seeking and interregional transfers contribute to urban primacy in sub-Saharan Africa? Papers in Regional Science, 92, 163–195.

- Bertinelli, L., & Black, D. (2004). Urbanization and growth. Journal of Urban Economics, 56, 80–96. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2004.03.003

- Brülhart, M., & Sbergami, F. (2009). Agglomeration and growth: Cross-country evidence. Journal of Urban Economics, 65, 48–63. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2008.08.003

- Cai, H., & Treisman, D. (2006). Did government decentralization cause China’s economic miracle? World Politics, 58, 505–535. doi:10.1353/wp.2007.0005

- Caldeira, E. (2012). Yardstick competition in a federation: Theory and evidence from China. China Economic Review, 23, 878–897. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2012.04.011

- China to create largest mega city in the world with 42 million people. (2011, January 24). The Telegraph. Retrieved from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/china/8278315/China-to-create-largest-mega-city-in-the-world-with-42-million-people.html

- China Statistical Yearbook (2015). Chapter I The National Administrative Jurisdictions. Beijing, China.

- Chou, B. K., & Huque, A. S. (2016). Does public participation matter? Inclusive growth in East Asia. Asian Journal of Political Science, 24(2), 163–181. doi:10.1080/02185377.2016.1164067

- Davis, J. C., & Henderson, V. J. (2003). Evidence on the political economy of the urbanization process. Journal of Urban Economics, 53, 98–125. doi:10.1016/S0094-1190(02)00504-1

- Davoodi, H., & Zou, H. F. (1998). Fiscal decentralization and economic growth: A cross-country study. Journal of Urban Economics, 43, 244–257. doi:10.1006/juec.1997.2042

- Fang, C. (2014). A review of Chinese urban development policy, emerging patterns and future adjustments. Geographical Research, 33, 674–686 (in Chinese).

- Feng, X., Ljungwall, C., Guo, S., & Wu, A. M. (2013). Fiscal federalism: A refined theory and its application in the Chinese context. Journal of Contemporary China, 22, 573–593. doi:10.1080/10670564.2013.766381

- Gabaix, X. (1999). Zipf’s law for cities: An explanation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114, 738–767. doi:10.1162/003355399556133

- Gallup, J., Sacks, J., & Mellinger, A. (1999). Geography and economic development. International Regional Science Review, 22, 179–232. doi:10.1177/016001799761012334

- Gao, X. (2017). Promotion prospects and career paths of local party-government leaders in China. Journal of Chinese Governance, 2, 223–234. doi:10.1080/23812346.2017.1311510

- Guimaraes, P., Figueiredo, O., & Woodward, D. (2000). Agglomeration and the location of foreign direct investment in Portugal. Journal of Urban Economics, 47, 115–135. doi:10.1006/juec.1999.2138

- Hansen, N. (1965). Unbalanced growth and regional development. Western Economic Journal, 4, 3–14.

- Hayashi, F. (2000). Econometrics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Henderson, J. V. (2003). The urbanization process and economic growth: The so-what question. Journal of Economic Growth, 8, 47–71. doi:10.1023/A:1022860800744

- Henderson, J. V., & Becker, R. (2000). Political economy of city size and formation. Journal of Urban Economics, 48, 453–484. doi:10.1006/juec.2000.2176

- Henderson, J. V., & Kuncoro, A. (1996). Industrial centralization in Indonesia. World Bank Economic Review, 10, 513–540. doi:10.1093/wber/10.3.513

- Jefferson, M. (1939). The law of the primate city. Geographical Review, 29, 226–232. doi:10.2307/209944

- Jia, J., Guo, Q., & Zhang, J. (2014). Fiscal decentralization and local expenditure policy in China. China Economic Review, 28, 107–122. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2014.01.002

- Jin, H., Qian, Y., & Weingast, B. R. (2005). Regional decentralization and fiscal incentives: Federalism, Chinese style. Journal of Public Economics, 89, 1719–1742. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.11.008

- Krugman, P. E., & Livas, R. (1996). Trade policy and the third world metropolis. Journal of Development Economics, 49, 137–150. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(95)00055-0

- Leong, C., & Lejano, R. (2016). Thick narratives and the persistence of institutions: Using the Q methodology to analyse IWRM reforms around the Yellow River. Policy Sciences, 49, 445–465. doi:10.1007/s11077-016-9253-1

- Lessmann, C. (2009). Fiscal decentralization and regional disparity: Evidence from cross-section and panel data. Environment and Planning A, 41, 2455–2473. doi:10.1068/a41296

- Li, H. (2016). An empirical analysis of the effects of land-transfer revenues on local governments’ spending preferences in China. China: An International Journal, 14(3), 29–50.

- Li, H. (2018). Intra-provincial fiscal disparities and the role of the provincial fiscal transfer system in China: A case study of Henan Province. Public Finance and Management, 18(2), 137–167.

- Lin, J. Y., & Liu, Z. (2000). Fiscal decentralization and economic growth in China. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 49, 1–21. doi:10.1086/452488

- Liu, Y., Martinez-Vazquez, J., & Wu, A. M. (2017). Fiscal decentralization, equalization, and intra-provincial inequality in China. International Tax and Public Finance, 24, 248–281. doi:10.1007/s10797-016-9416-1

- Lu, M., & Wan, G. (2014). Urbanization and urban systems in the People’s Republic of China: Research findings and policy recommendations. Journal of Economic Surveys, 28, 671–685. doi:10.1111/joes.2014.28.issue-4

- Matinez, J., & McNab, R. (2003). Fiscal Decentralization and Economic Growth. World Development, 31(9), 1597–1616.

- McGrath, D. T. (2005). More evidence on the spatial scale of cities. Journal of Urban Economics, 58, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2005.01.003

- Moomaw, R., & Shatter, A. (1996). Urbanization and economic development: A bias toward large cities? Journal of Urban Economics, 40, 13–37. doi:10.1006/juec.1996.0021

- Mutlu, S. (1989). Urban concentration and primacy revisited: An analysis and some policy conclusions. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 37, 611–639. doi:10.1086/451745

- National People’s Congress. (1989). Urban Planning Law. Chapter I Article 4. Beijing, China.

- Oates, W. E. (1999). An essay on fiscal federalism. Journal of Economic Literature, 37, 1120–1149. doi:10.1257/jel.37.3.1120

- Prud’homme, R. (1995). The dangers of decentralization. The World Bank Research Observer, 10, 201–220. doi:10.1093/wbro/10.2.201

- Quartz. (2014). China’s mega-cities are combining into mega-regions, and they’re doing it all wrong. Retrieved from http://qz.com/201012/chinas-mega-cities-are-combining-into-even-larger-mega-regions-and-theyre-doing-it-all-wrong/

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Ezcurra, R. (2010). Does decentralization matter for regional disparities? A cross-country analysis. Journal of Economic Geography, 10, 619–644. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbp049

- Rosen, K., & Resnick, M. (1980). The size distribution of cities: An examination of the Pareto law and primacy. Journal of Urban Economics, 8, 165–186. doi:10.1016/0094-1190(80)90043-1

- Roxburgh, H. (2017, May 5). Endless cities: Will China’s new urbanization just mean more sprawl? The Guardian.

- Savitch, H. V., Gross, J. S., & Ye, L. (2014). Do Chinese cities break the global mold? Cities, 41, 155–161. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2014.03.009

- Stock, J. H., & Motohir, Y. (2005). Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. In D. W. K. Andrews, T. J. Rothenberg, & J. H. Stock (Eds.), Identification and inference for econometric models: Essays in honor of Thomas Rothenburg (pp. 80–108). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Tiebout, C. (1956). A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy, 64, 416–424. doi:10.1086/257839

- Uchimura, H., & Jutting, J. P. (2007). Fiscal decentralization, Chinese style: good for health outcomes? (Discussion Papers No. 11). London, UK: Institute of Developing Economies.

- Walder, A. G. (1995). Local governments as industrial firms: An organizational analysis of China’s transitional economy. American Journal of Sociology, 101, 263–301. doi:10.1086/230725

- Wheaton, W., & Shishido, H. (1981). Urban concentration, agglomeration economies, and the level of economic development. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 30, 17–30. doi:10.1086/452537

- Williamson, J. G. (1965). Regional inequality and the process of national development. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 13(4), 3–45. doi:10.1086/450136

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2009). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach (4th ed.). Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.

- World Bank. (2002). China: National development and subnational finance, a review of provincial expenditures. Washington, DC: Author.

- Wu, A. M. (2013). How does decentralized governance work? Evidence from China. Journal of Contemporary China, 22, 379–393. doi:10.1080/10670564.2012.748958

- Wu, A. M., & Wang, W. (2013). Determinants of expenditure decentralization: Evidence from China. World Development, 46, 176–184. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.02.004

- Xu, J., & Yeh, A. G. O. (2010). Planning mega-city regions in China: Rationales and policies. Progress in Planning, 73, 17–22.

- Yang, J., Song, G., & Lin, J. (2014). Measuring spatial structure of China’s megaregions. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 141(2), 323–340.

- Yang, Z., & Wu, A. M. (2016). The dynamics of the city-managing county model in China: Implications for rural–urban interaction. Environment & Urbanization, 27, 327–342. doi:10.1177/0956247814566905

- Ye, L. (2013). Urban transformation and institutional policies: Case study of mega-region development in China’s Pearl River Delta. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 139(6), 292–300. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)UP.1943-5444.0000160

- Ye, L. (2014). State-led metropolitan governance in China: Making integrated city regions. Cities, 41, 200–208. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2014.03.001

- Ye, L., & Wu, A. M. (2014). Urbanization, land development and land financing: Evidence from Chinese cities. Journal of Urban Affairs, 36(S1), 354–368. doi:10.1111/juaf.12105

- Zhang, G. (2013). The impacts of intergovernmental transfers on local governments’ fiscal behavior in China: A cross-county analysis. The Australia Journal of Public Administration, 72(3), 264–277. doi:10.1111/1467-8500.12027

- Zhang, X. (2006). Fiscal decentralization and political centralization in China: Implications for growth and inequality. Journal of Comparative Economics, 34, 713–726. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2006.08.006