ABSTRACT

Despite the broad celebration of Brazil’s urban reform movement, recent events in Brazil have called attention to a paradox focused on the disappointing results of this movement to deal with Brazil’s complex urban context. Taking this “impasse” as a starting point, this article focuses on the role of politics and its relationship to economic interests in urban development in which much decision making around urban policy takes place to understand why Brazil’s progressive legislation has not succeeded in creating a more just and equitable urban environment. Using a case study of the city of Niterói, I show that patterns of state and nonstate actors are connected through both formal and informal relationships, and connections between public and private actors have a considerable impact on urban politics and policies. Focusing on the limits of participatory processes in Niterói, I call attention to the contradictions of participatory planning in Brazil.

Introduction

In the Brazil of the 1980s and 1990s, urban movements fought to advance the right to access urban land as a key claim of citizenship in Brazil’s democratization agenda. Fostering urban reform in the constitution-building process, this movement coalesced into a “popular democratic forum,” reconceptualizing inequitable land structures through participatory planning around three axes: (a) tenure security for low-income residents; (b) intervention in real estate speculation; and (c) the democratization of urban decision-making processes for direct participation (Rolnik, Citation2013). The urban reform movement has been broadly celebrated for its success in proposing a rights-based paradigm for urban development (Fernandes, Citation2011). Though Brazil has become known for producing a range of innovative urban experiments including participatory budgets, bus rapid transit, and other local progressive planning practices, the complexities of planning in Brazil offer theoretical insights to inform planning beyond Brazil. Indeed, the Brazilian case has been recognized given its approach as a democratic project to change the role of planning, the state, and social actors in governing cities based on social justice. Moreover, the successes and challenges of urban governance processes in Brazil provide opportunities to explore the efficacy of formalizing participatory institutions in challenging urban contexts.

Since 2013, recent optimism has shifted to pessimism in the context of broader politico-economic challenges in Brazil, especially regarding “the disappointing results of ‘really existing’ urban reform” (Klink & Denaldi, Citation2016, p. 404). Despite a favorable institutional environment, the democratization of decision making, and the availability of financial resources for social housing and slum upgrading, conditions in Brazilian cities have not improved and are often characterized by sociospatial and environmental contradictions, combined with a dynamic real estate market. Likewise, democratization has coincided with neoliberalization, changing the production of urban space in paradoxical ways (Caldeira & Holston, Citation2015). This context, overall, has been perceived as an “impasse” of urban reform in Brazil (Maricato, Citation2011). Despite achievements made since the 1988 constitution, urban policies have not been effective in dealing with the inherent challenges in Brazilian cities (Santos Junior & Montandon, Citation2011). Though this impasse has been used in reference to Brazil’s challenging urban context, Avritzer (Citation2016) points to the impasse as a democratic crisis in Brazil, arguing that two elements of this crisis are intertwined: the limits of popular participation on the one hand and a paradox in the fight against corruption on the other.

Beyond Brazil, there has been a growing critique of the limits of participatory planning. Despite divergence about what participation in planning entails (Day, Citation1997; Lane, Citation2005), it is grounded in conceptualizations of collaborative planning (Healey, Citation2006a), deliberative planning (Forrester, Citation1999), communicative rationality (Innes & Booher, Citation2010), and radical planning (Beard, Citation2003). Such approaches foreground the value of participation in changing the balance of power, providing meaningful opportunities for communities to deal directly with local issues, enhance fairness and justice, and advance the needs of the least advantaged groups (Innes & Booher, Citation2004). What Legacy (Citation2017) distinguishes as a crisis of participatory planning in the literature emphasizes the deficiencies of participation to address power inequalities and to accommodate equity-oriented approaches into planning processes (Sandercock, Citation1998; Yiftachel & Huxley, Citation2000). An early example is Arnstein’s (Citation1969) ladder of participation, which established the varying degrees to which participation could lead to influence and the varying types of participatory practices, from manipulation to citizen control. This epitomized a central debate: the extent to which involvement of the public is tokenistic or lacking the necessary level of delegated authority for citizen participation to be meaningful. Indeed, planning has long grappled with the issue of power in planning decision making, especially around the critique that there is a “dark side” to planning (Flyvbjerg, Citation1996; Yiftachel, Citation1998). Thus, rather than the idea that planning is inherently progressive, it may serve the interests of the powerful by marginalizing minority groups.

Foregrounded by the debate about the role of power in planning processes, in this article I argue that the paradox of participation in Brazil has to be understood by looking to the state and its relationship to economic interests, which ultimately reveals contradictions in participatory planning processes. I use the dual concepts of the relational fabric of the state and state permeability to show how state and nonstate actors are connected through formal and informal relationships (Marques, Citation2017). This also shows how the state can be both a central actor in the production of policies, while at the same time it is insulated and penetrated by private agents. The article adds to a growing debate that considers why Brazil’s progressive legislation has not succeeded in creating a more just and equitable urban environment (Klink & Denaldi, Citation2016; Rolnik, Citation2013). I use a case study of Niterói, a city across Guanabara Bay from Rio de Janeiro that advanced an urban reform agenda in the 1990s. Untangling a gap between theory and practice (Friendly, Citation2013), I use the case of Niterói as a starting point to understand the impasse of urban policy in Brazil. Though Brazil’s impasse of urban reform is complex, it is recently going through both challenges and new moments, with relevance for other countries in the Global South.

The case of Niterói is emblematic of the challenges faced by Brazilian cities; indeed, the same processes that transformed Brazil into an urban place induced the growth of Niterói. The city received considerable migration from other Brazilian states between the 1970s and 1980s, impelled by a supply of jobs in the construction of the Rio-Niterói bridge and Rio’s subway and the city’s fishing industry. Urban peripheralization to all parts of the city took place through migration from the north of Rio de Janeiro State and Brazil’s northeast. In the 1970s, Niterói began attracting high-income populations, intensifying in the 1980s with the densification of the Icaraí neighborhood; luxury real estate, mansions, and private clubs developed in contrast to the favelas in other parts of the city (Miranda, Citation2004). Residential expansion to the Oceânica region in the 1970s and 1980s—largely uninhabited until then—was led by developers, attracting both high- and low-income residents. Niterói thus gentrified, “attracting people with greater purchasing power and ‘expelling’ those with less purchasing power” to favela areas disdained by the market (Salandía, Citation2001, p. 110).

Niterói has a population of just over 500,000 residents, with the fourth highest gross domestic product per capita in the region (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE], Citation2018). Since the 1990s, Niterói’s human development index has climbed continually, the seventh highest in the country (Programa das Nações Unidas para o Desenvolvimento, Citation2018). Though Niterói built a middle-class image by adopting city marketing strategies since the 1990s, it is beset by a range of challenges similar to other Brazilian cities, including over 40,000 households living in 93 informal settlements, which rose 33.3% between 2000 and 2011 (ONU-Habitat/Universidade Federal Fluminense, Citation2013).Footnote1 These are often located in areas unsuitable for occupation, subject to landslides or floods, or lacking urban infrastructure (Fundação Getúlio Vargas [FGV], 2015). The proximity to Rio, Niterói’s prominent position within the Leste Fluminense metropolitan region, and the city’s position as a former state capital “indicate the possible relevance and attraction of the city as potential expansion for the real estate market” (Bienenstein, Bienenstein, Gorham, & Caputo, Citation2017, p. 11). Until the economic crisis that hit Brazil nationally, Niterói had an expanding real estate sector. Despite stagnation in these years, the market began climbing by 2017 (Secovi Rio, Citation2017). The propagation of an image of high quality of life and per capita income and a more affordable housing market than in Rio have attracted consumer interest to Niterói. Indeed, quality of life has been used in Niterói’s political discourse and appropriated by developers as a strategy to ensure its hegemony as a local political group (Carvalho, Citation2001). However, there is a perception that Niterói serves as a site for expanding the real estate market in Rio de Janeiro rather than for its working population (Luz, Citation2009). Indeed, Niterói is known deprecatingly as “cidade sorriso” (the smile city) because, the joke goes, the best quality of Niterói is the view of Rio.

This article uses fieldwork conducted in Niterói between November 2010 and May 2011 as a starting point to reflect on the broader literature on Brazil’s challenging urban reform transition. Data collection included semistructured interviews, document analysis, and observation at participatory meetings in Niterói. Interviewees were chosen via snowball sampling and gatekeeper techniques, including 58 interviews with local government representatives, business sectors, civil society and social movements, academic and professional associations, and politicians.Footnote2 A second phase of the research included an analysis of municipal documents, council minutes, and local media reports in 2017 and 2018. The next section sets the context of Brazil’s urban reform movement, before moving on to explore the role of political culture in Brazil, followed by the case of Niterói. The final part concludes by considering urban reform as an evolutionary transformation in governance practices.

Brazil’s context of urban reform

Bacha (Citation1974) coined the term Belinda was coined to refer to the small population living the life of those in industrialized countries (Belgium), whereas the rest of the population lives in misery (India). For this and other reasons, the case of Brazil provides both concrete lessons and a challenging context to view urban development and planning. One striking aspect of Brazil’s current urban makeup is the rapid urbanization process of the past half century, far surpassing urbanization in developed countries in terms of speed, climbing from a population that was only 30% urban in 1940 to 76% by 2010 (IBGE, Citation2017).Footnote3 However, this context is based on colonial history going back 5 centuries and a history of asymmetry (Maricato, Citation2008). Part of this inequality is a result of the exclusion of many Brazilians from property, differentiating the ruling elite from others, originating with the interaction of centuries-old policies and practices of land use, law, and the development of illegal urban peripheries lacking infrastructure and services (Freitas, Citation2017; Holston, Citation2008). Exclusionary land markets, an absence of affordable housing, clientelism, and elitist urban planning practices have also contributed to this context (Fernandes, Citation2007).

Urban reform was initiated in the 1960s before the dictatorship within a wider movement calling for “base reforms” (reformas de base), questioning Brazilian urbanization from a Marxist perspective and using concepts of segregation, exclusion, inequality, and re-thematizing the question of housing (Monte-Mór, Citation2007). Urban reform remerged in the 1980s following 21 years of dictatorship (1964–1985), based on criticisms of the unsuccessful technocratic and authoritarian planning model prevailing up to that point. Following the participation of the National Movement for Urban Reform (Movimento Nacional de Reforma Urbana) in the 1986–1987 Constituent Assembly, the 1988 “citizens” constitution included a specific chapter on urban policy. Ultimately, the National Movement for Urban Reform was successful in including two items in the new constitution: a focus on the social function of property (the obligation to use land uses contributing to the common good) and the right to the city as a right to participate in the production of urban space. In Brazil, the right to the city means a combination of the social function of property and the democratic management of cities (Friendly, Citation2013). Although the urban reform movement initially focused on local issues such as housing, the support of the Catholic Church, professional bodies, and the impact of academics influenced by Lefebvre’s (Citation1968) work on the right to the city produced a more structural interpretation of the causes of urban inequalities. As Freitas (Citation2017, p. 957) notes, “The movement claimed that achieving such rights required structural changes in planning policies making them fight for democratizing decision-making processes and combating segregation patterns.”

After 13 years of debate, the Statute of the City was enacted in 2001, recognizing the right to the city and the social function of property, following an intense negotiation process combining the urban reform movement, the environmental and social movements, the real estate sector, the municipalities, the states, and the federal government institutions dealing with housing and the environment (Bassul, Citation2005). Regulating the 1988 constitution’s two articles on urban policy, the statute mandates participation in planning through master plans but also in managing master plans through participatory fora including urban development councils, conferences, and public hearings (Fernandes, Citation2011; Friendly, Citation2013). Linked to specific social policies, councils are deliberative with joint assembly between government and society. Conferences are large-scale fora for decision making on public policies for the interaction of society on urban issues at the national, state, and municipal levels in conjunction with the deadlines outlined by the Ministry of Cities. The statute provides legal, urban, and fiscal instruments that may be used by cities within the context of their master plans to regulate urban land and property markets based on the principle of the social function of property. Framed as a series of instruments—or a “toolbox”—it allows municipalities to realize the concept of the social function. By mandating participation and transferring control of municipal affairs to cities, the statute seeks social justice.

Given the changes since the 1990s in Brazilian cities, a paradox has been highlighted in the literature around the expectation that Brazil’s transformation would occur by moving away from clientelism and exclusionary social policies through a new pattern of intervention in cities (Santos, Citation2011). Several problems have been raised regarding the implementation of Brazil’s participatory planning directives. First, as Caldeira and Holston (Citation2015) note, “Without being binding, popular participation in urban planning risks becoming irrelevant because an administration (executive and/or legislative) can both follow the participatory requirements and ignore the results” (p. 2012). Referring to the case of São Paulo between 2007 and 2010 under Mayor Gilberto Kassab, the authors note how discussions around the revision of the city’s master plan and zoning law ignored required procedures of popular participation. Indeed, as Avritzer’s (Citation2017) work on participatory innovation has shown, the political system can block innovation by ignoring deliberative processes, such as those involved in participatory urban planning. Second, there is no assurance that such participatory practices will result in outcomes prioritizing social justice or follow the principles of the Statute of the City.

Though Brazil’s planning experience has resulted in a transformative policy environment in many respects, gains in access to planning processes have been tested by gaps in the quality of participation (Friendly & Stiphany, Citation2018). Though Donaghy (Citation2011), Wampler (Citation2011), and others highlight clear examples of participatory processes that were inclusionary and pro-poor, such effects did not happen cohesively across Brazil, nor were they successful in breaking with traditional decision-making processes on urban policies (Rolnik, Citation2013). Despite commitments to justice within the constitution and the statute and the promise of change, institutionalization does not lead executive and legislative branches of government to ensure implementation.Footnote4 With this in mind, the next section explores Brazil’s political system including the role of clientelism and interactions between state and nonstate actors.

Brazil’s political system: Troca de favores, clientelism, and the state

The idea of patrimonialism has often been used in Brazil to depict the private appropriation of state resources by politicians, public servants, or members of the private sector (Schwartzman, Citation1982; Sorj, Citation2000). Mainwaring (Citation1999) defines patrimonialism as

a situation in which political rulers treat the state as if it were their own property. … Rather than allocate public resources according to universalistic criteria, politicians do so on the basis of personal connections, bestowing favors on their friends, family and parentela. (p. 179)

In the 1950s, Raymundo Faoro’s Os Donos do Podor (Faoro, Citation1958) drew attention to the idea of patrimonialism. For Faoro (Citation1958), patrimonialism in the Brazilian context—an inherently regressive condition—helps to explain Brazil’s economic and political challenges. Indeed, what is unique to the Brazilian version of patrimonialism is its bond to extreme social inequalities and the legal impunity of elites (Sorj, Citation2000). Common elements include a combination of rational-legal and personal, traditional authority, the use of force and the law for personal control of the ruler, the appropriation of public resources by privileged private actors, clientelistic networks linked to privileged actors, and a poor sense of the public good and universalistic citizenship (Pereira, Citation2016). Despite the importance of this idea, Pereira (Citation2016) suggests that patrimonialism is becoming increasingly misleading as an explanation of the workings of the Brazilian state, suggesting a re-examination of the idea.

In Brazil, political culture has long been marked by the concession of privileges from the powerful to the powerless (Sales, Citation1994). In the 19th century, local politics was dominated by patron–client relationships through a system of troca de favores under coronelismo, Brazil’s unique form of clientelism in which local bosses known as coroneles exercised control over voting behavior in local elections (Abers, Citation2000). Drawing on the history of Brazilian politics, Gomes (Citation1998) identifies an equilibrium between public and private actors in Brazilian politics, what Rolnik (Citation2011, p. 244) translates as “constitutive ambiguity,” which produces dualisms—actual and legal, public and private—that ultimately reinforce such borders with the objective of maintaining them.

To understand why the expected impacts of participatory processes have not occurred in Brazil goes beyond a focus on participatory venues. One explanation—and the subject of this article—focuses on the political electoral game and its relationship to economic interests in urban development in which much decision making around urban policy takes place (Rolnik, Citation2013). In this reading, the “premodern forces” of clientelistic politics (Maricato, Citation2009, p. 207) deeply impact the implementation of institutionalized participation venues. Although not addressed sufficiently in the literature, the political system can block (democratic) innovation and in some cases even co-opt such experiences following its success (Avritzer, Citation2017). As Rolnik (Citation2011) explains, these connections between private and public actors deeply impact decision-making processes in urban development:

Businesses involved in formal urban production establish privileged connections with public agencies, who control the selection of urbanization projects and programs, as well as town planning, guaranteeing markets in certain urban areas for their products and protecting the profitability of their investments. In the area of urban development, these decision processes take place within land management bureaucracies, which are highly permeated by networks of influence that connect businesses with congressmen and political parties, since public works contractors, service providers and real estate developers and builders actively finance electoral campaigns. (p. 245)

In Brazil, there is evidence of clientelistic relations at the municipal level, in the management of public services, and in the ways in which Brazilians perceive power (Pereira, Citation2016). Clientelism, however, is a relatively secret phenomenon, while evidence about it is indirect and measurement is often based on perceptions (Avritzer, Citation2016). Indeed, Marques (Citation2017) suggests that though the role of politics and corruption is an implicit, unresearched area, some information suggests connections of local political and economic elites with capital, generating avenues for private sector influence on urban policies.

An obvious starting point in the literature is Molotch’s (Citation1976) urban growth machine, focusing attention on the actors driving change in cities and the power differentials that arise surrounding land, markets, and growth. According to Logan and Molotch (Citation1987), progrowth coalitions of government and economic interests focus on infrastructure and urban development in areas of profit to their interests, promoting an ideology of growth as a public good. Though the idea of growth machines originating from the United States was framed by a context in which local government financing left local places without funding sources, Brazilian cities have significant financial resources at their disposal (Arretche, Citation2012). As a result, the relationship connecting local elites to economic interests is not as dependent as in the U.S. case. Although the growth machine has been used in Brazil (Fix, Citation2009), the relationships between these actors are more political, more mediated by access to public funds, and more linked to elections than to the promotion of land policies as suggested by the urban growth machine literature (Marques, Citation2017). This suggests a need for a theory that better responds to the context of Brazilian urban development.

Following Marques (Citation2017), an understanding of this dynamic more specific to the Brazilian context is based on two dual notions: (a) the relational fabric of the state and (b) state permeability. First, the relational fabric of the state shows how patterns of state and nonstate actors are connected through formal and informal relationships that internally structure the state and couple it with the broader political environment. Second, state permeability refers to the connections between private and state actors, illustrating how the state can be, on the one hand, key in the production of policies, while it is both insulated and penetrated by private agents. The relational fabric of the state is constituted by overlapping networks including state technicians or bureaucracies, people demanding policies, contractors, politicians, and officials occupying elected or designated positions, yet such relations are constituted continuously over time and within policy communities. Moreover, the way in which this fabric is framed may influence political conflicts inside the state as actors use their relative positions as power resources.

These dual notions of the relational fabric of the state and state permeability resonate with the spatially selective nature of Brazilian urban planning (Klink & Denaldi, Citation2016), drawing on state spatial transformation. Indeed, Brenner (Citation2009) shows how the state spatial regime of European Fordism, what he calls spatial Keynesianism, was organized with a goal of economic growth and redistribution to produce a cohesive national economy. In the 1970s, shifting political and economic strategies transformed spatial Keynesianism into a rescaled and competitive state spatial regime. In Brazil, referring to housing finance and capital markets, Klink and Denaldi (Citation2014) show that the focus of the national developmental state has prioritized economic growth over redistributive and sustainable objectives. Indeed, Brazilian financialization is part of an “endogenous” process in which the state selectively intervenes in finance and housing delivery via the private sector. In the 1980s, this selective developmental state became the milieu for the contradictory social production of the city created “under the shadow of the state” (Rolnik, Citation2011, p. 245).

The participatory planning literature in Brazil shows a link—albeit vague—between clientelism and patronage on the one hand and the participatory process on the other. Here, I use the ideas of the relational fabric of the state and state permeability to understand this process, referring to this as a contradiction of participatory urban planning in Brazil. Dagnino (Citation2003, p. 7) calls this a “perverse confluence” between leftist and neoliberal participatory planning and development. Indeed, despite the recognition of participation in the legal-urban order in Brazil, it “has not taken place in all stages of decision-making and it has often been manipulated, reinforcing the long-standing tradition of political patronage” (Fernandes, Citation2018, p. 55). For example, Villaça’s (Citation2005) well-known work has shown private-sector interest and influence over the design of municipal regulations through deeply challenging relationships between master plans and politicians. Relatedly, using a case of a public–private partnerships in Porto Alegre’s participatory budget, Pimentel Walker (Citation2015) illustrates strategic co-optation by a neoliberal participatory project over a leftist agenda. Pimentel Walker (Citation2015) explains how center-right politicians were politically forced to envision a strategy of participatory planning to incorporate the outcomes of municipal socialism through popular participation characteristic of participatory budgeting. Indeed, the combination between vested interests in real estate and land markets and supported by interdependencies between global finance, the building and construction industry, and an open and liberalized Brazilian capital market produces complex challenges to make effective gains with the Statute of the City (Klink & Keivani, Citation2013). Given the role of politics and the framework of the relational fabric of the state and state permeability, in the next part I examine the case of Niterói.

The planning context in Niterói

Although the statute was adopted in 2001, many of its ideas were applied before its passage. This was the case in Niterói of the late 1980s and early 1990s, in a context in which new migrants were arriving to the city, together with private-sector expansion, the growth of favelas, and spatial segregation. Indeed, this was a period in which local political discourse intensified, strengthening the city’s leadership in the state of Rio de Janeiro. As a result, political actors identified urban management as a strategic space to empower “‘new’ vectors of local development” (Biasotto, Barandier, & Domingues, Citation2008, p. 3). Niterói’s first secretariat of urbanism was created at this time, driven by the ideological atmosphere of the new administration (Salandía, Citation2001). When Jorge Roberto Silveira of the Democratic Labour Party (Partido Democratico Trabalhista, PDT), a populist democratic social party, became mayor in 1989, he appointed former architecture professor João Sampaio as secretary of urbanism.Footnote5 Though the situation in Niterói was rather bleak, the prefeitura (the administrative entity of city hall) had no clear picture of Niterói’s challenges.Footnote6 Based on community consultation, the municipality commissioned a major report to better understand the city in preparation for its master plan (Instituto Brasileiro de Administração Municipal, Citation1991). The report lists 70 favelas in Niterói and summarizes the perceived problems, including sanitation, transportation and roads, housing, planning, and administration. The report notes that the city is “without sanitation, with a choked road system, precarious transport and lagoons plagued by squatting and land speculation,” whereas, in contrast, the area is lauded as “having enormous potential for tourism and as the ‘new Niterói’ which should house the city’s expansion” (Instituto Brasileiro de Administração Municipal, Citation1991, p. 78). This early reading paints a picture of a city in need of governance reforms and service upgrading and an administration prepared to facilitate reforms and include the population through local participatory processes.

To produce the city’s master plan internally, the prefeitura hired several recent graduates, given that it had no experienced staff, helping to consolidate Niterói’s planning vision. João Sampaio’s vision was key in producing a master plan, conceived under the aegis of a progressive ideology intended to introduce planning innovations (Biasotto et al., Citation2008). According to Sampaio, in the early 1990s, the necessity of urban legislation was clearly apparent: “We felt it was time to have urban legislation, because the city was very sparse, very clustered and very old. So it was time to do something more updated, including new guidelines that were already there, the constitution itself” (personal interview [PI], March 18, 2011).

The 1992 master plan divided the city into five regions—Praias da Baía, Oceânica, Pendotiba, Norte, and Leste—requiring regional urban plans (planos urbanísticos regionais, PUR) for each. Essentially a “mini” master plan, PURs establish urban parameters for land use for each region, respecting the master plan’s guidelines. The master plan reflected a focus on social justice, the means to apply the social function of property, applied by using the urban tools in the master plan. It adopted several tools to enforce the social function, an urban development council, and delegated responsibility to the PURs. Though this restructuring eliminated the pre-existing patchwork with little planning logic, without a federal law to regulate this such as the statute, the urban tools could not be implemented (Salandía, Citation2001). Though struggles over the statute’s content took place nationally, cities like Niterói made commitments to social justice by including such tools in their master plans, to be put into practice at a future date. Despite advances in the 1990s, Niterói’s master plan instituted a planning system that took more than a decade to be partially constructed.

State permeability in Niterói

Reflecting the ideas of the relational fabric of the state and state permeability used by Marques (Citation2017), urban planning in Brazil is highly influenced by centralized bureaucracies depending on decision-making processes influenced by political and economic interests. As Rolnik notes (Citation2011),

More than a supposed “political desire” to follow a master plan, local governments clearly lack incentives to do so, since … decision-making processes on investments and the future of the city are, under the current Brazilian federative model and political system, based on a different logic. (p. 252)

Given the paradox cited in the literature and Brazil’s challenges in the urban reform process, the political context plays a role in applying the norms upheld by the urban reform movement.

In an interview, João Sampaio of the PDT, former Niterói mayor and secretary of urbanism asks, “Who calls the shots in the city? It’s more or less the same gang that is in Congress” (PI, March 18, 2011), meaning that politicians in the city are powerful actors. Since 1989, the PDT has been the predominant political party in Niterói. Interviewees referred to the presence of a political machine as an element in local policymaking, defined by an academic as “a mafia, a group that has appropriated what is public, which is the executive power itself, and exercises a model of tyranny” (PI, November 8, 2010). Jorge Roberto Silveira (PDT) has been mayor of Niterói three times between 1989 and 2012, although the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, PT) has also been represented. During Silvera’s years as mayor, the same city councilors were often elected and many of these were often aligned with the executive power. In Silveira’s many years in office, there were often claims about his appointees making deals.Footnote7 Though these claims are hard to document, the state of Rio de Janeiro has a history of clientelistic politics under Governor Leonel Brizola, also of the PDT, and in Niterói during the Silveira years (Alves, Citation2015; Arias, Citation2006).Footnote8 As a political aide to Marcelo Freixo, then a progressive state deputy of the Socialism and Freedom Party (Partido Socialismo e Liberdade), noted, “In Rio de Janeiro State there is a tradition relating to this co-optation politics that we can see in the government of Jorge Roberto Silveira, who is from the PDT and Leonel Brizola” (PI, May 12, 2011). Likewise, the mayor’s opposition in city council is limited to a few members of the Socialism and Freedom Party, leading a member of the nongovernmental organization Viva Niterói to observe that “Niterói has captive electorates” who vote in the same members of the political machine (PI, March 16, 2011). In 2013, Rodrigo Neves of the PT was elected mayor but in 2017 realigned himself with PDT.Footnote9

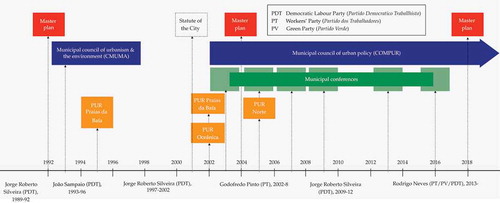

Similar to other Brazilian cities, Niterói’s prefeitura is closely tied to real estate speculators. For example, Alves (Citation2015) shows that in 2012, the PT received more than 50% of its campaign revenue from real estate companies. Referring to this period, Alves (Citation2015) notes how Niterói is governed managerially, affording it a business approach, which is distant from a socially oriented governance approach of earlier years in the city. As Alves (Citation2015) explains, “This implies granting the interests of the market, of the companies, to the detriment of the public interest and the well-being of the population, especially the most needy” (p. 69). To examine the idea of state permeability in more detail in connection to participatory spaces, the next section focuses on state permeability within two participatory venues: the master plan and its urban development council known as COMPUR.Footnote10 shows an overview of Niterói’s participatory achievements since the 1990s.

Contradictions of participatory institutions in Niterói

Participation was crucial to the vision of Niterói’s 1992 master plan, resulting from an understanding that the constitution required participatory master plans. According to the statute, participatory master plans are required for cities larger than 20,000, and participation is a criterion for master plans to be considered valid and legally binding. In Brazil’s system of urban development, master plans are the basic instrument of urban development, despite the urban reform movement’s rejection of the master plan based on its ideological character in discouraging urban conflicts (Maricato, Citation2000). Though the master plan was not included in the urban popular amendments presented to the constitutional assembly, it was integrated into the final constitutional text on urban policy by conservative deputies (Bassul, Citation2005). Thus, ironically, in the implementation of the Statute of the City, members of the urban reform movement supported this requirement as the key means to transform urban policy at the national level and to stimulate justice through popular participation. Indeed, participatory master planning incorporates a rather heterogeneous set of actors and interests, and it is consultative rather than deliberative (Calderia & Holston, Citation2015).

During the plan’s preparation in Niterói, participation occurred through public hearings and thematic seminars. At the meetings, the report commissioned in preparation for the master plan was presented alongside a questionnaire asking about city problems (including sanitation, transportation, housing, planning, and other challenges) and hopes for the master plan (Carvalho, Comarú, & Teixeira, Citation2009). The questionnaire, which involved the community, was used to compile information on land use, urban infrastructure, and transportation, although proposals were often specific demands rather than strategic planning proposals. Despite little understanding of what participation entailed, the population was relatively mobilized. Indeed, members of Niterói’s civil society noted that the master plan involved “real” participation because everyone could participate, that participation in the 1990s was based on an open model, and that the process was legitimized by the population. Despite such positive comments, respondents criticized the prefeitura for applying participation because it was an obligation. Indeed, an academic notes,

Niterói always had militant segments, so these segments occupied these meetings, but the issue-based groups are more or less the same groups which are here today. … Even then, it was participation in meetings to try to add one or another initiative and not properly a democratic meeting in a broad way. (PI, November 8, 2010)Footnote11

This suggests that civil society was largely left out of a government-led process.

Approved during Niterói’s first municipal conference in 2003, the municipal council of urban policy (conselho municipal de política urbana, COMPUR) brings together government and civil society to propose and assess the city’s urban development, focusing on land regularization, housing, environmental sanitation, transportation, and urban mobility.Footnote12 COMPUR is considered to be deliberative, meaning that draft bills have to pass through it before going to city council. Considered a proportional entity—half are managers and producers of urban space (government, city council, and businesses), whereas the other half are movements, unions, professional or academic entities, and nongovernmental organizations, representing two different visions of the city. Councilors are elected during the bi-annual municipal conference, where objectives are set for achieving urban policy, the effectiveness of proposals from past conferences is evaluated, new discussion topics are proposed, and proposals are forwarded to the state and federal conferences.

Though COMPUR is considered a proportional entity, in practice its composition is more favorable to the government, according to interviewees, who noted that the government often acts to deplete meetings so that quorum cannot be reached, resulting in delayed discussions. Rather than crafting policies, it is perceived to legitimize the government’s actions and back government policies. A member of the Community Council of the Orla da Baía (see note 11) observed that “we become pawns for them to legitimize. They know they need the council to receive funds, so they do it in a way that they don’t get harmed” (PI, April 27, 2011). This backing of government policies is reiterated by the ex-secretary of urbanism: “I understand [COMPUR] as just a chore … something that we have to give to the council because it has a certain representativity and for it being a broadcaster of what is happening” (PI, March 23, 2011). A member of the Federation of Associations of Residents of Niterói (Federação das Associações de Moradores de Niterói), Niterói's umbrella civil society organization, notes that:

We see a lot of what the administration wants to do, then we see we’re nothing for the government. They will decide it, they find a way to approve what they want and we never get to include anything of ours. So I see COMPUR today is just for us to acknowledge what they are doing, but we have no active voice to do something. Afterwards, the government has its defence to say, “No, we held the meeting and people were there to hear,” but people were there and we had no decision power. (PI, January 25, 2011)

In addition, because legislative power is vested in the city council, in practice COMPUR plays a consultative role. Despite intense discussions, proposals made in COMPUR are often not carried out in city council. For example, despite amendments passed in COMPUR for the revitalization of Niterói’s center in 2006, a U.S. consultant was hired to prepare the plan without COMPUR’s oversight, as interviewees noted. However, city staff and the private sector maintain that a deliberative council would create difficulties. Though COMPUR’s powers are legally established, the city council often ignores it and acts alone; the government, by contrast, uses COMPUR to justify its actions. A challenge, therefore, is to ensure the effectiveness of such democratic institutions, rather than to legitimize the specific interests of certain actors (Hagino, Citation2007; Thibes, Citation2008).

Despite challenges, COMPUR is part of Niterói’s participatory planning system. Many of Niterói’s participatory achievements are attributed to the municipal conferences in 2003 and 2005 (Santos & Oliveira, Citation2009). The most obvious was the renewal of COMPUR, following the first municipal conference in 2003. Moreover, Brazil’s experience with participatory democracy is recent, often challenging the autonomy of councils. For one former planner in Niterói, COMPUR’s viability depends on the prefeitura’s commitment to participation and civil society’s degree of mobilization (Friendly, Citation2013). However, civil society on its own cannot force the government to concede to opening spaces for participation. Thus, the participatory institutions required by law at a national level remain even more important. As Avritzer’s (Citation2017) work has shown, Brazil’s policy councils seek to create institutions following a citizenship logic and are disconnected from the electoral system. Such councils question the technical and bureaucratic logic of policymaking, yielding efficiency in public policy through social participation. In that sense, these councils connect participatory design with bottom-up and horizontal policy design.

Following the statute’s approval, Niterói adequated its new master plan in 2004 to the recently approved Statute of the City. Though the 2004 law is considered an adequation to make the master plan compatible with the statute (Salandía, Citation2004), it did not make significant changes to the previous version, instead strengthening the implementation of the statute’s norms.Footnote13 Though participation in 2004 was relatively weak, it was not prioritized by the prefeitura. Public hearings were based on bureaucratic formalities, leading to an assumption that the prefeitura did not fulfill its obligation to discuss urban issues with the community (Teixeira, Comarú, & Carvalho, Citation2005). Indeed, a study of the process found that proposals for the master plan were discussed in restricted technical forums to incorporate the minimum conditions to adopt the Statute’s new tools (Biasotto et al., Citation2008). As one member of the Community Council of the Orla da Baía noted, “They simply held a public hearing, but they didn’t explain anything, it caught everyone by surprise” (PI, March 30, 2011). Referring to the case of Niterói, Carvalho et al. (Citation2009) note that substantial power differentials result in asymmetrical decision-making roles between the private sector and the population, influencing the implementation of the statute’s tools. Thus, tools

that regulate and which are interesting to the real estate market are rapidly deployed, while those of interest to the poorest take much longer to be implemented. One cause for this is a tradition of close relations between the agents linked to real estate sector and parts of the administrative structure. Even when it sides in favour of the most vulnerable segments [of society], the administration has difficulties in making a political confrontation in the application of innovative instruments in urban policy … without the support of social pressure. (Carvalho et al., Citation2009, p. 110)

In parallel to COMPUR, another participatory entity emerged in 2012, illustrating a reaction to the difficulties encountered within the city’s existing institutional structures (Alves, Citation2015). Known as the urban policy forum of Niterói (Fórum de Política Urbana de Niterói, Citation2018), it was formed at the initiative of some COMPUR councillors to better tackle issues within a conflictual context with the government, yet without decision-making capabilities or being institutionalized. As Alves (Citation2015) notes, the role of urban policy forum of Niterói is to

interfere by creating barriers, calling society and the powers established for reflection, through public hearings, specialized debates and with the support of community associations and experts on the issues addressed. In the last case, through denunciations with the Ministério Público, matters in newspapers, etc. (p. 88)

In 2014, plans began for a revision of Niterói’s master plan, carried out by the FGV, a private higher education institution based in São Paulo. This episode was highly criticized given that the FGV had no history in Niterói and, subsequently, the case was brought to the Ministério Público because the FGV was awarded the contract without a bidding process (Schmitt & Sodré, Citation2014).Footnote14 Ultimately, the FGV carried out a series of reports in preparation for the master plan (FGV, 2015). The municipal government used several strategies, including fragmenting civil society; using images of an imagined city; calling long or overly technical public hearings; convening bureaucrats to defend its interests; reducing discussion time, making participants into spectators; failing to disclose public hearings; and co-opting key leaders by trading public positions to facilitate approval of initiatives (Bienenstein et al., Citation2017). Although the process began in 2014, the plan was not approved until 2017, which was ultimately suspended following an injunction based on procedural irregularities and an absence of effective participation.

Although the prefeitura had outlined a plan for participation in the master plan, without a broader and more detailed discussion, the result was a set of generic intentions without the possibility of immediate application, instead referring the issue to be solved by subsequent laws or at the discretion of the municipal executive—a common challenge of Brazil’s master plans (Bienenstein et al., Citation2017). In 2017, based on a study by the Laboratory of Social Participation in Urban Policy, an initiative of two universities, the Institute of Architects of Brazil, and civil society, procedural irregularities and an absence of effective debate on the master plan resulted in the suspension of Niterói’s new master plan (Martins, Citation2015; Martins, Araújo, Maia, & Drumond, Citation2017). In an interview, city Councilor Carlos Jordy of the Social Christian Party (Partido Social Cristão) noted that

what happened was that the project arrived at the Câmara [city council] full of vices and irregularities, without respecting the Statute of the City. … Our mandate noted insurmountable irregularities. We observed that public hearings only took place with the Chamber, with the legislative power organizing after the project has already been prepared, and the Statute of the City provides that in the elaboration phase the executive power should organize public hearings and debates to listen to the society that will help in the preparation of the project, and this was not done by the executive power, the city hall delivered the project already prepared for the Chamber to present the society. (Anonymous, Citation2017)

The master plan was suspended in late 2017 after an injunction granted at the request of Councilor Jordy, yet the injunction was subsequently suspended in early 2018. The suspension of this process can be considered a triumph of institutions to ensure a more democratic and participatory plan is put in place. Ultimately, however, in late November 2018, the new master plan was finally approved in city council amid criticism from progressive sectors of the city.Footnote15

In Niterói, though laws are discussed within COMPUR, when voting in city council, a different outcome can result from the council’s decision. An emblematic case is the Urban Concorciated Operation (Operação Urbana Consorciada, OUC)—a public–private partnership—to revitalize Niterói’s center within a context of financial crisis across Brazil, proposed at the beginning of Rodrigo Neves’s 2013 mandate. Referring to the process in which Niterói considered the use of OUC in the city, Bienenstein, Bienenstein, and Sousa (2015) note that these

strategies focused on leaving parts of the city under the free will of the real estate market, stimulating the historical process of land use, of which the real estate market is a protagonist. In general, the purpose of this type of initiative is to change the laws of these urban areas, creating exclusive areas where real estate capital can act directly, without obstacles and, perhaps more problematic, without risks. (p. 1)

By using the sale of Certificates of Additional Construction Potential, allowing developers to build above the parameters established by law, the prefeitura intended to raise R$1 billion to finance the operation.Footnote16 In fact, Neves constructed a discourse based on a scenario for the city center that supported the adoption of the OUC as a single solution for the crisis facing the city—which included disorganization, deterioration, economic stagnation, and insecurity, presenting the OUC as a window of opportunity for Niterói in reference to Kingdon’s (Citation1995) multiple-streams framework. Following the case of Porto Maravilha in Rio, the project was heavily supported by the real estate sector (Bienenstein, Bienenstein, & Sousa, Citation2015). Though Niterói has experienced urban expansion since the 1970s and processes of real estate speculation, the OUC would provide for an intensification of this process in the center directed to middle and upper classes (Figueiredo, Citation2015). Since the 2000s, proposals for Niterói’s center have promoted increased real estate profits by changing urban legislation and intensifying land use in the city’s most valued areas, yet without studies indicating possible impacts on infrastructure and urban mobility (Sousa, Citation2017).

In the COMPUR meeting on May 21, 2013, the OUC project was presented to the surprise of the councilors, yet not discussed during the meeting.Footnote17 Subsequently, on June 4, Law PL 143/2013 was approved in the câmara, allowing the municipality to institute the OUC. The prefeitura tried to show that there had been strong participation by COMPUR in discussions of the OUC project. Indeed, in the executive message preceding the law, Neves noted that

in the last months, through periodic meetings of the Council of Urban Policy of the Municipality—COMPUR, representatives of civil society, representative associations and unions participated in the process of defining the area of special urban interest delimited for the preliminary studies to the draft law, as well as the definition of the guidelines, objectives and instruments for the implementation of OUC. (Câmara Municipal de Niterói, Citation2013)

The law was denounced on the grounds that it was not discussed within COMPUR before being approved and because studies of the project had not been carried out (Bienenstein et al., Citation2017; Schmitt, Citation2013). Indeed, local officials did not foresee the capacity by organized civil society to organize and to attract the attention of the state Ministério Público, who submitted the proposal to a series of public hearings (Madeira Filho & Terra, Citation2013).Footnote18 The result was also likely influenced by the 2013 protests in Brazil, which had also taken place in Niterói. As Sousa (Citation2017) shows, beginning in 2012, the process was characterized by co-optation “with the hiring, by means of commissioned positions, of some of the most important and active leaders … in struggles for democratization of the planning and management of the city, thus being able to immobilize them” (p. 14).Footnote19

A key challenge of this approach based on the demands of the market—that of state permeability—is that it can result in the erosion of urban planning as a tool of democratization or worse, aimed at “guaranteeing governability through progressive ‘taming,’” referring to the movements becoming passive (Sousa, Citation2017, p. 17). Indeed, participatory fora are designed to deter power arrangements from taking over planning processes. For that reason, Flyvbjerg (Citation2002) proposed using planning councils in decision-making processes to account for the issue of power and the engagement of stakeholders. However, the composition of such councils and stakeholder decisions are political acts, and as Huxley and Yiftachel (Citation2000) remind us, the powers of private developers and the state are entangled in communicative encounters involving planners. As the problems with COMPUR show, the presence of a planning council is not enough to dissuade powerful forces from playing a key role in urban policy.

Although such cases in this area are challenging to prove (Avritzer, Citation2016), in Niterói the perception is that politicians alter outcomes to fit their interests. Indeed, Alves’s (Citation2015) study of Niterói’s participatory institutions found that in COMPUR, though many issues reach a consensus, the role of state actors and their interests ultimately prevail, without justification. Indeed, a study in several cities of the Leste Fluminense region also found that the local government manipulated policy councils (Barros, Citation2011). In Niterói, though the population is consulted, “the mayor has a majority, that’s the political game … they do whatever they want,” as a municipal secretary noted (PI, December 20, 2010). The mayor’s support is thus key to the fulfillment of democratic processes and to how the power dynamics play out in the city. Indeed, research shows that the outcomes of participatory institutions in Brazil are related to the level of mayoral support, who must delegate authority to citizens (Wampler, Citation2007). For that reason, an academic based in Niterói notes that “who has the power need not participate in these things. Access to decisions is made by other paths. Even direct access to those who call the shots” (PI, April 12, 2011).

On the other hand, private actors are participating actively in Niterói’s institutionalized participatory fora, in contrast to a smaller role in the past. Though developers were relatively inactive in the 1990s, by 2009 they had become more engaged. For an architect with the Institute of Architects of Brazil, an alternative view is that the contradictions in Niterói are rarely evident “because those who have power don’t need to go to COMPUR to defend their ideas, they have a direct channel to the executive” (PI, December 3, 2010). Therefore, though in theory COMPUR should represent the city’s urban sectors, the outcome of participation in institutionalized spaces—as shown in the case of Niterói—is often altered by powerful forces.

Overall, these examples point to sentiments expressed by several interviewees: local governments and the public interest are compromised by private interests. As Alves (Citation2015) explains:

Niterói’s urban policy agenda is determined by the market and there is a total lack of willingness of the state actors in relation to the social participation in the decisions of public policies, mainly because their interests collide with those of the civil society. Also, because electoral campaigns are financed by corporate resources, another example of how the current electoral financing process is deleterious to political relations. (p. 88)

Indeed, in evaluating the limitations and opportunities in institutionalizing Brazil’s urban reform agenda, Rolnik (Citation2011) notes that businesses involved in urban development form privileged connections with governments, guaranteeing access to markets in urban areas and protecting their investments’ profitability. As a result, within the debate about the paradox of participation, the relationship between the state and economic interests—using the idea of the relational fabric and state permeability—illustrates troubling tendencies and, ultimately, reveals contradictions in participatory planning in Brazil. In the final section, I reflect on these contradictions with reference to Healey’s (Citation2006b) work on governance transformations.

What’s next for urban reform?

A detailed reading of the Niterói case shows that patterns of state and nonstate actors are connected through both formal and informal relationships, and connections between public and private actors have a considerable impact on urban politics and policies, showing that politics does matter (Marques, Citation2017). Based on the case of Niterói, this detailed reading is shown by exploring the complex workings of COMPUR, the revision (and ultimate suspension) of the city’s new master plan, as well as the case of the OUC proposed to revitalize Niterói’s center. Thus, state and nonstate actors affect the outcomes of participatory planning processes, an overall process that I connect with the limits of participatory planning and its contradictions. This perspective emphasizes the complex workings of Niterói’s political and economic actors, the inequalities among them, and the consequences of this disparity. This points to the complexity of heterogeneous power relations when powerful actors use social processes to their own advantage (Healey, Citation2006a), giving rise to outcomes favoring the city’s political and economic powers. Despite a master plan and related urban legislation focused on social justice, planning policy has not prioritized the interests of the poor in Niterói, and those with political or economic connections often define the city’s political discourse.

The case of Niterói helps to elucidate some of the challenges of participatory planning due to power imbalances. Indeed, what I have referred to as a contradiction of participatory planning—explained through decision-making processes influenced by economic and political actors—helps to understand why some characteristics of urban policies block the attempts at implementing a reform agenda based on cities planned democratically in the public sphere (Rolnik, Citation2011). Such participatory governance arrangements are inherently “Janus-faced” because the political sphere is undermined by the encroachment of market forces setting the rules of the game (Swyngedouw, Citation2005). As Caldeira and Holston (Citation2015) note, the implementation of Brazil’s participatory planning experience

raises troubling and paradoxical questions as to whether the working-class production of urban life will continue to define city-making in Brazil through participatory processes or whether it will be gutted by those—executives, legislators and developers—who find ways to ignore or usurp participation. (p. 2002)

Indeed, the paradox of participatory planning in Brazil raises questions about the future of urban reform and what shape it will take in the future. Ultimately, what is at stake in this context is a deep imbalance in power relations, with disparities in how different socioeconomic groups participate in decision-making processes but also divergent capabilities, resources, influence, and knowledge.

Within the literature on the limits and potentials of Brazil’s challenging move toward urban reform, Klink and Denaldi (Citation2016) suggest that the “really existing” spaces and scales of urban reform should be studied within a more complex and contingent context in which both state and nonstate actors strive to influence it according to their interests. Broadly, Healey’s (Citation2006b) work on governance transformations sheds light on the issue of implementing the urban reform agenda, given the challenges highlighted in this article. As Healey (Citation2006b) notes, such processes link networks, discourses, and practices with cultural assumptions giving legitimacy to actors and processes. For Healey (Citation2006b), governance transformations are sustained through long-term shifts in economic, sociocultural, and political relations, yet such innovations need to become institutionalized to endure. A planner at the Ministry of Cities reiterates this point, noting that the statute’s inception creates an expectation that rules are followed and the requirement that the guidelines are implemented. However, “it requires much articulation, mobilization, much awareness, and all that with strong political support, because otherwise it does not advance” (PI, December 9, 2010).

Healey’s (Citation2006b) work on governance transformations also suggests that the urban reform process is evolutionary. In considering these governance transformations in Brazil, these ideas are particularly relevant in the context of the considerable changes that have occurred since the end of the dictatorship, the return to democracy, and the models of institutionalized participatory governance that have taken root in the last 30 years. The complexities of planning in Brazil—and the contradictions such as those detailed in Niterói—are made further challenging in the context following Dilma Roussef’s impeachment process in 2016.Footnote20 In addition, the de-institutionalization of participation in urban policies together with an overall fragility of these innovations have occurred in the context of a weakened democracy.Footnote21 Healey’s (Citation2006b) suggestion about the institutionalization of policies suggests that perhaps more time is needed for Brazil’s urban innovations to endure. Indeed,

transformative initiatives which succeed in “institutionalization” need to have the capacity to “travel” not just from one arena to another, but from one level of consciousness to another. By this, a translation is meant from the level of conscious actor invention and mobilization to that of routinization as accepted practices, and beyond that to broadly accepted cultural norms and values. (p. 304)

Thus, according to Healey (Citation2006b), to become institutionalized would depend on sets of ideas or institutionalized regulatory practices and ways of using and shaping resource distribution.

More broadly, promise can be seen in the movement of insurgent practices starting with the June 2013 manifestations that asserted themselves to demand something better for everyday life in cities in Brazil (Friendly, Citation2017; Vicino & Fahlberg, Citation2017). This broad movement represents “both a complaint against contradictory inherited spaces and a demand for better projected spaces” (Klink & Denaldi, Citation2016, p. 413). Indeed, the sustained role of social pressure from civil society actors is necessary to make the right to the city a reality in cities like Niterói. However, what role participation takes in the future is under question. Finally, without developing redistributive policies in Brazil to address its enduring inequality, changes in the urban sphere will be difficult to reverse. In recent years, Brazil has made some headway nationally (Souza, Citation2012), although the retraction of the past few years, the economic crisis, and—even more worrying—the national turn toward the political right have likely reversed such improvements. Overall, any proposal to transform urban legislation in Brazil—such as involving more democratic principles or improving the transparency of the processes—has to account for the fact that the system of urban development is entrenched within a highly established political context. Such experiences—including Brazil’s successes and challenges—are therefore particularly important in providing lessons for other countries in the Global South.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the four anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on this draft. The author also thanks the many research participants in Niterói.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Abigail Friendly

Abigail Friendly, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Human Geography and Spatial Planning at Utrecht University and a Research Fellow at the Global Cities Institute, University of Toronto. Friendly holds an MSc in global politics from the London School of Economics and a PhD in planning from the University of Toronto. Her research interests focus urban policy, governance, participation, and justice in the Latin American context. Over the last few years, Friendly’s research has focused on urban policies in Brazil, including work on metropolitan governance, land value capture, and city diplomacy.

Notes

1. Brazil’s census includes a category for informal settlements, updated in 2011. IBGE (2011) calculates that there are 24,286 households located in 77 informal settlements comprising 16% of Niteroí’s population. Despite measurement challenges, the difference between ONU-Habitat/Universidade Federal Fluminense (Citation2013) and Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (2011) calculations is marked. For more information on the methodology used to measure precarious settlements, see Bienenstein, Sanchez, Amaral, and Reis (Citation2009).

2. I established rigor by spending prolonged engagement in Niterói, building trust among respondents, and ensuring that the research was clearly documented through an audit train including the documentation of data.

3. In 2017, IBGE released new projections for Brazil’s urban population based on a new classification system within the 2020 Census (IBGE, Citation2017). This puts Brazil’s urban population at 76%, as opposed to 84.4% as presented in the previous 2010 Census. This projection is based on the fact that only 25% of Brazil’s municipalities are considered to be urban, whereas the majority of Brazilian municipalities are predominantly rural in character.

4. Elsewhere, I have highlighted the poor implementation of the statute’s tools based on the case of Niterói (Friendly, Citation2013).

5. In Brazil, the secretária (secretary) of urbanism, like other secretaries, is appointed by the mayor. The secretária of urbanism oversees the secretariat of urbanism or the planning department.

6. I use the Portuguese prefeitura to refer to the administrative entity of city hall, containing the executive and mayor’s offices.

7. In 2016, Silveira, along with others in his administration, was convicted of “administrative impropriety” regarding benefit payments of a social rent program and negligence of public money (Gonzaga, Citation2016).

8. Elected state governor in 1982, Brizola worked to improve basic urban services in favelas, yet he is known to have employed clientelism by co-opting favela leaders into his government who could have demanded the continuation of his policies after leaving office (Arias, Citation2006).

9. In 2015, Neves disaffiliated from the PT in favor of the Green Party (Partido Verde). He ultimately left the Green Party for the PDT in 2017.

10. Instances of participatory planning also take place in the context of the regional urban plans known as PURs. The process involves meetings in each neighborhood, starting from a diagnosis, and then returning with proposals based on community involvement, followed by approving the legislation with the population. Although there are five administrative planning regions, PURs exist for only three, and there has been considerable controversy surrounding these processes. Indeed, the final hearings in city council of the 2004 PURs suggest a political bargaining process between the legislature and local real estate agents (Biasotto et al., Citation2008).

11. Although this article does not focus on the role of civil society, it is key in considering the effects of urban reform. In Niterói, civil society organizations formed around housing and urban land policies during the 1980s; the Federation of Associations of Residents of Niterói (Federação das Associações de Moradores de Niterói), an umbrella organization, emerged in 1982. Since the late 1990s, the critical mass of Niterói’s civil society has resided with several additional key organizations including the Community Council of the Orla da Baía (Conselho Comunitário da Orla da Baía) and the Community Council of the Oceânica Region (Conselho Comunitário da Região Oceânica; Friendly, Citation2016).

12. A precursor council known as the Municipal Council of Urbanism and the Environment was created under the aegis of the 1992 plan but was deactivated following the start of Silveira’s term as mayor, coinciding with discussions of a controversial tool called operações interligadas (Biasotto et al., Citation2008; Salandía, Citation2001).

13. The word adequation is taken from the Niterói case, where it refers to the adaptation of the 2004 master plan to the new directives of the statute. Adequation is used because it is a more accurate translation of the Portuguese adequação.

14. The Ministério Público refers to Brazil’s collective body of public prosecutors, an important legal institution that separates the three branches of government, charged with defending society and the law.

15. In Brazil, city hall and city council are separate entities; local government—which is autonomous—is composed of an executive power (the mayor) and a legislative power (city council, or câmara municipal), which legislates local public policies and oversees executive actions.

16. Certificates of Additional Construction Potential are securities sold to release building rights to be used within OUCs, areas defined for redevelopment in the city. There has been substantial critique focusing on gentrification, the selectivity of public investments, social segregation, and contradictory results (Siqueira, Citation2014).

17. In May 2013, a few months before these events, the fifth municipal conference of Niterói contained no mention of the OUC (Madeira Filho & Terra, Citation2013).

18. In Niterói, debates around verticalization and city expansion have tended to be polemic. In 2011, Jorge Roberto Silveira presented an OUC called Novo Centro Expandido, allowing land use changes in several neighborhoods, but it was halted due to controversy.

19. As this process continued, the verticalization debate in Niterói underwent changes with the modification of a tool called the onerous grant of the right to construct (outorga onerosa do direito de construir, OODC), which allows for increases in building height in exchange for projects of social interest. Although Niterói had used the OODC in the past, the 2016 changes meant that alterations through the OODC were cheaper than those through the OUC, likely resulting in real estate speculation.

20. Roussef’s impeachment followed an ongoing corruption crisis that started with the state-owned oil company Petrobras and came to include a diverse range of politicians.

21. A study of public policy councils in Brazil across different sectors in 2016 found that these spaces were under threat of extinction and deactivation, given the uncertainty and changes during this period (de Avelino, Alencar, & Costa, Citation2017).

References

- Abers, R. N. (2000). Inventing local democracy: Grassroots politics in Brazil. London, UK: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Alves, A. C. T. D. M. (2015). O Sentido da Participação Social: Um Estudo de Casos Múltiplos no Setor de Política Urbana de Niterói-RJ (Masters thesis). Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói, Brazil.

- Anonymous. (2017, November 13). Liminar Suspende a Primeira Votação do Novo Plano Diretor de Niterói. Journal Cidade de Niterói, Retrieved from http://cidadedeniteroi.com/blog/2017/11/23/liminar-suspende-primeira-votacao-do-novo-plano-diretor-de-niteroi/

- Arias, E. D. (2006). Drugs and democracy in Rio de Janeiro: Trafficking, social networks and public security. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Arnstein, A. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Planning Association, 35(4), 216–224.

- Arretche, M. (2012). Democracia, Federalismo e Centralização no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Fiocruz/FGV.

- Avritzer, L. (2016). Impasses da Democracia no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Civilização Brasileira.

- Avritzer, L. (2017). The two faces of institutional innovation: Promises and limits of democratic participation in Latin America. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bacha, E. L. (Ed.). (1974). O Rei da Belíndia: Uma Fábula para Tecnocratas. Os mitos de uma década (pp. 57–61). Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Paz e Terra.

- Barros, A. M. B. (2011). Controlando as Políticas Públicas: O Papel dos Conselhos Municipais. Revista de Direito da Cidade, 1(4–7), 1–25.

- Bassul, J. R. (2005). Estatuto da Cidade: Quem Ganhou? Quem Perdeu? Brasília, Brazil: Senado Federal.

- Beard, V. A. (2003). Learning radical planning: The power of collective action. Planning Theory, 2(1), 13–35. doi:10.1177/1473095203002001004

- Biasotto, R., Barandier, H., & Domingues, R. L. (2008). Avaliação dos Planos Diretores—Estudo de Caso de Niterói. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Instituto de Pesquisa e Planejamento Urbano e Regional.

- Bienenstein, R., Bienenstein, G., Gorham, C., & Caputo, C. (2017, November 8–10). Desafios da Participação e Controle Social na Gestão Urbana Contemporânea: O Caso de Niterói. Paper presented at the 4° Fórum Habitar, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

- Bienenstein, R., Bienenstein, G., & Sousa, D. M. M. D. (2015, May 18–21). A Cidade dos Negócios e os Negócios na Cidade: Notas Sobre as Operações Urbanas na Região Metropolitana do Rio de Janeiro. Paper presented at the XVI Encontro Nacional da ANPUR, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

- Bienenstein, R., Sanchez, F., Amaral, D. F., & Reis, E. P. D. (2009, April 3–7). Geoprocessamento: Um Possível Instrumento para o Desenho de Políticas Públicas de Habitação. Paper presented at the XII Encuentro de Geógrafos de América Latina, EGAL, Montevideo, Uruguay.

- Brenner, N. (2009). Urban governance and the production of new state spaces in Western Europe, 1960–2000. In B. Aarts, A. Lagendijk, & H. Van Woutum (Eds.), The disoriented state: Shifts in governmentality, territoriality and governance (pp. 41–77). Nijmegen, the Netherlands: Springer.

- Caldeira, T., & Holston, J. (2015). Participatory urban planning in Brazil. Urban Studies, 52(11), 2001–2017. doi:10.1177/0042098014524461

- Câmara Municipal de Niterói. (2013). Mensagem Executiva 17/2013/2013, Projeto de Lei No 00143/2013. Retreived from http://camaraniteroi.rj.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/ab9bcfca008d65af8c64ddb03085dc63eafada73.pdf.

- Carvalho, M. A. J., Comarú, F. D. A., & Teixeira, A. C. C. (2009). Plano Diretor de Niterói, Rio de Janeiro: Desafios da Construção de um Sistema de Planejamento e Gestão Urbana. In R. Cymbalista & P. F. Santoro (Eds.), Planos Diretores: Processos e Aprendizados (pp. 91–112). São Paulo, Brazil: Instituto Pólis.

- Carvalho, M. C. A. (2001). Niterói: A Construção de Uma Imagem de Cidade da Qualidade de Vida (Masters thesis). Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói, Brazil.

- Dagnino, E. (2003). Citizenship in Latin America: An introduction. Latin American Perspectives, 30(2), 3–17. doi:10.1177/0094582X02250624

- Day, D. (1997). Citizen participation in the planning process: An essentially contested concept? Journal of Planning Literature, 11(3), 421–434. doi:10.1177/088541229701100309

- de Avelino, D. P., Alencar, J. L. O., & Costa, P. C. B. (2017). Colegiados Nacionais de Políticas Públicas em Contexto de Mudanças: Equipes de Apoio e Estratégias de Sobrevivência. Brasília, Brazil: IPEA.

- Donaghy, M. (2011). Do participatory governance institutions matter? Municipal councils and social housing programs in Brazil. Comparative Politics, 44(1), 83–102. doi:10.5129/001041510X13815229366606

- Faoro, R. (1958). Os Donos do Poder: Formação do Patronato Político Brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Editora Globo.

- Fernandes, E. (2007). Constructing the ‘Right to the City’ in Brazil. Social and Legal Studies, 16(2), 201–219. doi:10.1177/0964663907076529

- Fernandes, E. (2011). Implementing the Urban reform agenda in Brazil: Possibilities, challenges, and lessons. Urban Forum, 22(3), 299–314. doi:10.1007/s12132-011-9124-y

- Fernandes, E. (2018). Urban planning at a crossroads: A critical assessment of Brazil’s City statute, 15 years later. In G. Bhan, S. Srinivas, & V. Watson (Eds.), The Routledge companion to planning in the Global South (pp. 48–58). London, UK: Routledge.

- Figueiredo, K. S. (2015). A Incorporação do Espaço Urbano Pelo Setor Imobiliário na Cidade de Niterói (RJ) e a Questão da Localização e das Forças Monopólio. Ensaios de Geografia, 4(8), 49–69.