ABSTRACT

Based on a Polanyi-inspired research program, we analyze urban transformations as interrelations between infrastructural configurations, i.e. context-dependent material infrastructures and their multi-scalar political-economic regulations, and socio-cultural modes of living. Describing different modes of infrastructure provisioning in Vienna between 1890 and today, we illustrate how political-economic processes of commodification and decommodification have co-evolved with socio-culturally specific modes of living, grounded in different classes and milieus. We show how, today, two modes of living—“traditional,” established during postwar welfare capitalism, and “liberal,” formed during neoliberal capitalism—co-exist. In the current conjuncture of rising inequality, neoliberal urban regeneration, and accelerating climate crisis, these modes of living are not only increasingly polarized and antagonistic, but also increasingly unable to satisfy needs and self-defined aspirations. Therefore, we explore the potential of social-ecological infrastructural configurations as an alliance-building project for a systemic social-ecological transformation, potentially linking different classes, social segments and forces around a common eco-social endeavor.

Introduction

This article explores political strategies to combine urban struggles against socio-spatial inequalities and against ecological degradation by elaborating a Polanyi-inspired research program that links social and ecological concerns. At the center of this new hegemonic project is a foundational approach (Foundational Economy Collective, Citation2018), identifying social-ecological infrastructural configurations as essential for a “good life for all” within ecological boundaries (cf. O’Neill et al., Citation2018). Hence, in our Polanyi-inspired research program, analyzing historically specific infrastructural configurations is conducive to the understanding of urban development.

Infrastructures are artifacts, like schools, roads, pipes, and cables. They create pathways of how everyday life can (and cannot) be lived and how an economy can (and cannot) function (cf. Barlösius, Citation2019). Without bicycle lanes, there is no safe cycling; without a sufficient housing stock and electricity, appropriate dwelling is impossible; without health and care facilities, there is no safeguarding in situations of physical and psychological vulnerability. The provisioning of these material infrastructures influences how needs can be satisfied and depends on multi-scalar regulations: Which traffic rules support cycling? How are national housing policies configured? Do health services offer access to all residents, to all citizens or only to private clients? Are care services provided locally or in large centralized care centers? Is education free for all? Or more generally, which regulations contribute to inclusive accessibility and which to social stratification and segregation? As such, infrastructural configurations are artifacts (the material infrastructures) plus the respective regulations for their provisioning and use. These infrastructural configurations interrelate with specific modes of living, i.e. predominant routinized, context-specific, and value-laden practices of how needs are satisfied. We do not decide daily how we travel to work, nor do we choose everyday anew how and where we spend our free time.

Historically, specific infrastructural configurations have emerged in response to specific problems, political alliances, and social struggles. In the 19th century in Europe, disastrous hygienic conditions as well as the requirements of modern industry stimulated a broad array of technical infrastructures,Footnote1 like electric cables, pipes for water and gas, streets and sewage systems. In the 20th century, an increasingly powerful workers movement as well as political democracy led to accessible and affordable social infrastructural configurationsFootnote2 (particularly public education, health care, and social housing). Technical and social infrastructural configurations, built in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, have not only accelerated capital accumulation, but also institutionalized civic, political, and social rights. Today, however, the climate crisis and increasing inequalities present new challenges that require more than the adaptation and extension of existing infrastructural configurations. New ones have to be created to overcome unequal and resource-intensive modes of provisioning that increasingly lead to social disarray, socio-spatial polarization, and ecological cataclysm, inhibiting a “good life for all.” Our Polanyi-inspired research program suggests that if such deep transformations are to take place, conflicts will be unavoidable. It acknowledges that social protection, i.e. the high-quality and affordable provisioning of universal basic needs, is a necessary but insufficient precondition to mitigate resistance and form new alliances against fossil- and finance-dominated power blocs, against soaring rents as well as a car-centered infrastructure.

In this article, we hence argue for the centrality of social-ecological infrastructural configurationsFootnote3 as an alliance-building project that has the potential to link different classes, social segments and forces around a common eco-social endeavor. We define social-ecological infrastructural configurations as accessible (e.g., public spaces), affordable (e.g., housing, health, and care) and sustainable,Footnote4 providing inter alia green spaces, decarbonized housing and modes of mobility as well as sustainable energy. Therefore, social-ecological infrastructural configurations make new modes of living possible, ones that do not predicate a good life only at the expense of others (cf. Brand & Wissen, Citation2018).

In Section 2, laying the theoretical foundation, we propose a Polanyi-inspired research program that analyses “the relations of the economic process to the political and cultural spheres of the society at large” (Polanyi, Citation1977, p. 35). This research program studies the relationships between political economy and culture (Jessop & Sum, Citation2013), between different modes of provisioning and modes of living. Subsequently, in Section 3, we apply this theoretical framework to the analysis of different historical periods of urban development in Vienna. After briefly sketching developments from 1890 until 1934, we will particularly focus on the periods 1945–1980 and 1980 until today to explain current crises in prevalent modes of living; this is discussed in Section 4. Finally, in Section 5, we explore the potential of social-ecological infrastructural configurations as an alliance-building project for a systemic social-ecological transformation of cities.

Making sense of transformation: A Polanyi-inspired research program

Karl Polanyi was a theorist of transformation, concerned with the interwoven dynamics of long-term and short-term change, of incremental and radical processes, of evolutionary changes (e.g., Industrial Revolution) and political ruptures (e.g., the rise of fascism). He conceptualized these transformations as (1) a double movement of commodification and decommodification, and (2) a dialectics between improvement and habitation.Footnote5 In what follows, Sections 2.1 and 2.2 reconstruct Polanyi’s argument, Section 2.3 offers a critical appraisal, and, based on this, Section 2.4 proposes our Polanyi-inspired research program for the analysis of infrastructural configurations and their relationship to modes of living.

Commodification and decommodification: The political-economic dialectics of capitalist development

Polanyi interpreted capitalism as an inherently contradictory process of commodification and decommodification:

Social history in the nineteenth century was thus the result of a double movement: the extension of the market organization in respect to genuine commodities was accompanied by its restriction in respect to fictitious ones. While on the one hand markets spread all over the face of the globe and the amount of goods involved grew to unbelievable dimensions, on the other hand a network of measures and policies was integrated into powerful institutions designed to check the action of the market relative to labor, land, and money. (Polanyi, Citation1944/2001, p. 79)

This interplay captures two simultaneous political-economic dynamics that shape modes of provisioning: on one hand, the expansion of market logic to ever new societal and natural domains, i.e. the expansion of market provisioning (commodification); and on the other, the deliberate or unintended regulation of markets as well as forms of non-market provisioning (decommodification), especially those of land, labor and money, which are “obviously not commodities,” but fictitious commodities.Footnote6 Regarding these, “the postulate that anything that is bought and sold must have been produced for sale is emphatically untrue” (Polanyi, Citation1944/2001, p. 75f). These fictitious commodities are peculiar and of particular social and political interest, since their ever-expanding commodification threatens to destroy society: “leaving the fate of soil and people to the market would be tantamount to annihilating them” (Polanyi, Citation1944/2001, p. 137); it would damage them irreversibly, be it an exhausted laborer or depleted soil.

Although Polanyi himself did not categorize different forms of countering commodification, Goodwin (Citation2018, p. 1274) provides a useful distinction: (1) intervening (direct interventions in markets, e.g., rent or labor market regulations), (2) limiting (supplementary mechanisms, e.g., housing benefits or social transfers) and (3) preventing and/or reversing (mechanisms to avert or reverse commodification, e.g., municipalization of housing or public education). While “intervening” and “limiting” reduce socio-economic vulnerabilities and stabilize ways of life in a market economy, only “preventing” and “reversing” fully decommodify certain economic sectors (e.g., housing, finance) or entire spheres of life (e.g., air and water, care, leisure), thereby institutionalizing forms of non-market provisioning. “Preventing” and “reversing” are thus offensive forms of decommodification, while “limiting” and “intervening” are rather defensive (cf. Goodwin, Citation2018, p. 1279ff).

Improvement and habitation: The socio-cultural dialectics of capitalist development

For Polanyi, this double movement cannot be reduced to economistic dynamics of more or less markets, of commodification and decommodification. It is always and simultaneously a dialectics of change and stability (Berman, Citation1988; Harvey, Citation1990), progress and tradition. Polanyi conceptualizes this as a dialectic of “improvement” and “habitation.” Efforts toward rapid and uncontrolled economic “improvement,” i.e. specific accumulation strategies to increase productivity, profitability and economic growth, lead to planned and unplanned counter-movements for social protection. The quest for “habitation” motivates diverse reactions to excessive commodification.

Although Polanyi left the concept of habitation under-explained, we can ascribe to it a double meaning: etymologically, it refers to the fact or act of living in a place (Etymology Dictionary, Citationn.d.) which suggests two moments. First, the fact of living (in a place) depends on certain material preconditions in order to sustain livelihood. Habitation is, therefore, a universal basic need, independent of temporal and spatial specifications. Second, the act of living in a place expresses itself in particular practices of how needs are satisfied, which are culturally, spatially and historically contingent (cf. Gough, Citation2017), shaped by specific modes of provisioning. As such, “habitation” is metonymic with “mode of living.” It is based on certain values and is class-specific, depending on concrete wage relations and on gendered divisions of labor (Kesteloot, Citation2005). To take the “American way of life” during welfare capitalism as an emblematic case, it was based on moral judgments prioritizing a materialist understanding of a good life, its manifestation was a stratified and highly (ethnically) segregated society, dependent on an international division of labor beneficial to the U.S. and on a gendered division of labor (the male-breadwinner model).

Polanyi illustrates the concepts of “improvement” and “habitation” in The Great Transformation. Regarding the former, he notes how the process of enclosure in the 18th century triggered substantial improvements: “Enclosed land was worth double and treble the unenclosed. Where tillage was maintained, employment did not fall off, and the food supply markedly increased” (Polanyi, Citation1944/2001, p. 35f). Similarly, in the 19th century the “modernization of legislation,” which extended the “freedom of contract” to land, fostered the “owner’s right to improve his land profitably” (Polanyi, Citation1944/2001, p. 191). But alongside these improvements came “grave dislocation in habitations” (Polanyi, Citation1944/2001, p. 191), causing “devastations” for “social order” and “ancient law and custom,” thereby disrupting the social fabric of communities (Polanyi, Citation1944/2001, pp. 21/36f). With regard to housing, “this powerful trend was reversed only in the 1870s, when legislation altered its course radically” and “the ‘collectivist’ period” began:

The inertia of the common law was now deliberately enhanced by statutes expressly passed in order to protect the habitations and occupations of the rural classes against the effects of freedom of contract. A comprehensive effort was launched to ensure some degree of health and salubrity in the housing of the poor, providing them with allotments, giving them a chance to escape from the slums and to breathe the fresh air of nature, the ‘gentleman’s park’: Wretched Irish tenants and London slum-dwellers were rescued from the grip of the laws of the market by legislative acts designed to protect their habitation against the juggernaut, improvement. (Polanyi, Citation1944/2001, p. 191)

Polanyi, however, was no anti-modernist; he did not prefer stability over change, habitation over improvement, even that induced by capitalist modernization. Acknowledging their respective merits, he favored modernization at a moderate pace, as slow change permits the mitigation of destructive effects arising from improvement.Footnote7 Rapid and “blind improvements” (Polanyi, Citation1944/2001, p. 257), on the contrary, cause social ruptures and threaten “habitation,” i.e. prevalent modes of living.

Hence, “if market economy was a threat to the human and natural components of the social fabric … what else would one expect than an urge on the part of a great variety of people to press for some sort of protection?” (Polanyi, Citation1944/2001, p. 156; our italics). The emphasis on some sort is crucial, as the quest for protection to meet basic needs is universal, but its form of provisioning contextually variegated, thereby shaping specific acts of living in a place. Attempts to decommodify modes of provisioning, as a reaction to excessive commodification, are therefore contingent and thus overdetermined (Novy et al., Citation2019), depending not least on powerful narratives, successful alliance-building and effective drawing on cultural, political and economic resources (Burawoy, Citation2003, p. 221). For example, the collapse of liberal capitalism in the world economic crisis after 1929 triggered counter-movements against excessive commodification which were socio-culturally diverse—some were democratic, others authoritarian, some state-driven, others anarchistic; ranging from fascism and Roosevelt’s New Deal to Stalin’s centrally planned economy (Polanyi, Citation1944/2001, p. 248). “Plotting [counter-movements’] coordinates is no simple task” (Dale, Citation2012, p. 12).

Polanyi’s shortcomings

The double movement is a powerful and immensely helpful analytical concept. However, Polanyi remained victim of a linear understanding of progress which led to his well-known, but erroneous assumption of “the end of market society” (Polanyi, Citation1944/2001, p. 260). He rightly assumed that the liberal capitalism of the 1920s was inherently unstable. But he underestimated the possibility of stabilizing the market economy in new forms—even if only temporarily. What he terms economic “improvement,” i.e. a specific accumulation strategy, is never, as Polanyi assumed, only a result of commodification, but always emerges through the dialectical interplay between commodification and decommodification, market and state agency—emphatically emphasized in research on gentrification (Zuk et al., Citation2018) and financialization (Aalbers, Citation2017): public investment in transportation infrastructure and green spaces can increase rent gaps, i.e. the difference between the actual and the potential profitability of housing (Smith, Citation1979), which enables private rent appropriation; labor regulation is decisive for increasing labor productivity; during Fordism, policies that decommodified housing created intimate dwellings that facilitated mass consumption, leading to commodification as a new “social consumption norm” (Aglietta, Citation2015, p. 82).

Hence, contrary to Polanyi’s assumption, the history of capitalism is neither a linear process of ever more spheres of life being commodified, nor did non-market provisioning per se subvert capitalism. In order to reproduce itself, capitalism as a mode of production systemically relies on both decommodification and commodification dynamics in specific sectors.Footnote8 Decommodifying certain economic sectors (especially infrastructure provisioning) and spheres of life (especially the household) can be functional for capital by safeguarding it from its self-destructive tendencies (Offe, Citation1975). At the same time, decommodifying modes of provisioning (e.g., public housing or transport) need public funds that have to be obtained via taxes levied on the commodification of labor power. In capitalism, commodification and decommodification are always entangled.

However, given that capitalism’s relentless pursuit of profit and the imperative of accumulation tend to “melt all that is solid into air” (Marx & Engels, Citation1976, p. 487), the decommodification of certain sectors never constitutes a lasting accommodation (cf. Jessop, Citation1990, p. 40). For example, while decommodifying the provisioning of social infrastructures during welfare capitalism mitigated detrimental societal effects of excessive commodification during liberal capitalism, falling rates of profit triggered a new shift toward commodification in neoliberal capitalism from the 1980s onward. Hence, the spatio-temporal oscillation between commodification and decommodification of land, labor and money results from specific constellations of power and produces variegated forms of capitalism in different historical and spatial contexts (cf. Peck & Theodore, Citation2007).Footnote9

Furthermore, Polanyi introduced the term countermovement to capture socio-culturally distinct tendencies of decommodification of fictitious commodities in order to protect one’s “habitation” as a response to movements of commodification, erroneously assuming that this countermovement was definitive after World War II, thereby failing to explain the postwar history (Dale, Citation2012, p. 11). As a matter of definition, Polanyian-type countermovements are therefore widely conceived as movements that unequivocally resist any market provisioning. At the same time, Polanyi himself recognized that movements of protection can also serve pro-market political alliances: “The reactions of the working class and the peasantry to market economy both led to protectionism, the former mainly in the form of social legislation and factory laws, the latter in agrarian tariffs and land laws. Yet there was this important difference: in an emergency, the farmers and peasants of Europe defended the market system, which working-class policies endangered” (Polanyi, Citation1944/2001, p. 200). This illustrates that countermovements as they emerge in the real world, like the above-mentioned peasantry, are complex and ambivalent. They cannot be reduced to an unequivocal resistance to market provisioning, but might remain favorable to capitalist commodification in general, while selectively opposing certain forms of commodification (in this case a global agrarian market).

Along these lines, given the diffusion of commodified modes of living in the 21st century, reactionary socio-cultural quests for protection might actualize as specific responses to overall commodification (e.g., of employment or pensions) that simultaneously oppose new forms of decommodification (e.g., those promoted by climate policies, like changes in building regulations, land use and mobility). Such socio-cultural quests for protection might be an effort to protect one’s culturally, spatially, and historically contingent, but supposedly legitimate, mode of living against changes caused by decommodification. This reaction is more widespread in contemporary, highly-commodified societies in Western Europe and North America, which are deeply accustomed to extensive market provisioning. Modes of living are conservative in the literal meaning: they seek to conserve socio-culturally specific ways of satisfying needs as well as accompanying moral judgments. Perceived threats might create reactions in defense of commodification and freedom of (market-)choice. These reactions always emerge from diverse “sectional interests” that serve as a “vehicle of social and political change” (Polanyi, Citation1944/2001, p. 159): “The ‘challenge’ is to society as a whole, the ‘response’ comes through groups, sections and classes” (Polanyi, Citation1944/2001, p. 260). The “challenge” of the climate crisis will not lead to a “response” through humanity, but through political alliances between specific societal actors, as we will propose in section 5.

A Polanyi-inspired research program

To sum up, we propose a Polanyi-inspired research program that (1) analyses the relationships between the (de)commodification of modes of provisioning (conceptualized as infrastructural configurations) and modes of living (conceptualized as routinized, context-specific and value-laden practices), and (2) accounts for the ambiguity of counter-movements.

With regard to (1), the provisioning of housing is central to our analysis. Housing is deeply entangled in different infrastructural configurations: its proper functioning depends on technical infrastructures; its living environment’s attractiveness on the availability of social infrastructures such as kindergartens, schools, or care facilities; and its sustainability and resilience on ecological infrastructures. Its accessibility and affordability depends on the configuration of multi-scalar regulations that (de)commodify their provisioning and use, including rent and zoning regulations as well as legal entitlements and ownership (e.g., public or private). Our research program hence investigates these specific configurations—through the lens of commodification (particularly in the form of weakened rent regulation, privatization, and financialization) and decommodification (intervening, limiting, reversing/preventing)—and their relations to modes of living.

Regarding (2), Polanyi’s asymmetrical countermovement (moving unequivocally against commodification) has to be understood as part of a broader, more ambiguous and symmetrical phenomenon to guide concrete research. To take the burning issue of ecological urban regeneration: Improving the decommodified provisioning of, for instance, green and public infrastructure accessible for leisure, cycling, and pedestrianism, might come at the cost of private parking lots, challenging prevalent modes of living based on commodified mobility habits of residents who depend on the car (e.g., for work) or perceive it as constitutive of a specific way of life. Resistance against the “loss of a sense of place,”Footnote10 can thus be expected; especially if change happens quickly and the spectrum of action becomes as narrow as “adapt or move” (Goossens et al., Citation2019, pp. 19/14). Therefore, movements of protection—“the active defense of environments, of social relations, of processes of social reproduction, of collective memories and cultural traditions” (Harvey, Citation2019, p. 114, in reference to Polanyi)—might also be directed against specific measures of decommodification.

Our research program is therefore conducive to a better understanding of (socio-cultural contestations and struggles for and against) variegated capitalist modes of provisioning and their entanglement with modes of living. Moreover, in a more visionary sense, it permits research on pathways toward post-capitalist societies in which decommodifying modes of provisioning is no longer merely functional for the reproduction of capital, but becomes part of “a civilizational transformation in accord with the fundamental need of people to be sustained by social relations of mutual respect” (Polanyi Levitt, Citation2013, p. 105).

A short history of urban infrastructural configurations: The case of Vienna

The city of Vienna is well known for its high quality of life, historically rooted in its public infrastructure, especially its housing sector, built up over three periods of urban development. First, we provide a brief retrospect covering the period up to World War II, in which different strategies dealt with the darker sides of modernization (Berman, Citation1988), quite successfully controlling diseases and improving formerly deplorable living conditions while pursuing different (and not always progressive) socio-cultural aspirations. Subsequently, we will address postwar urban development and neoliberal urban regeneration from the 1980s onward in more detail. In each period we observe a specific interplay of commodification and decommodification with different socio-cultural manifestations. While decommodification dominated in essential economic sectors and spheres of life in the postwar period, the 1980s led to a new wave of modes of market-based provisioning. Both periods gave rise to specific infrastructural configurations and related modes of living.

A brief retrospect: Urban development before World War II

In the late 19th century, there was a first “heroic municipal phase” that “set in train a material transformation of life chances, life quality and everyday life experience” in European cities (Foundational Economy Collective, Citation2018, p. 33). In Vienna, between the 1890s and 1910s, an anti-socialist countermovement under the leadership of the Christian-Social mayor Karl Lueger decommodified major parts of urban infrastructure, taking over from previously private foreign-owned enterprises a wide range of essential services like gas, electricity, water, sanitation, and tramways. This decommodification of technical infrastructures was functional for local enterprises. Lueger was supported by traditional sectors of landlords, craft and trade, and confronted liberal elites. The latter even allied with the Emperor to prevent him taking office in 1895 (Schorske, Citation1980). Given the prominence of Jewish professionals, artists, and entrepreneurs, Lueger “invented” a political anti-Semitism that created a new “political culture that incited the masses against the (old) elites and the “integrated” against the “outsiders”” (Maderthaner & Musner, Citation2002, p. 867). Lueger’s offensive decommodification of technical infrastructures thus concretized itself in a socio-culturally conservative, exclusionary and religious anti-liberalism, hostile to liberal elites and secularized Marxism. The working class was systematically excluded and women’s rights restricted.

Due to Lueger’s alliance with landlords, residential construction remained almost entirely in private hands, leading to soaring housing costs for working-class households. Red Vienna (1919–1934), the world-renowned social-democratic municipal reformism, made housing policy, the neglected field of Lueger’s modernization project, the center of its decommodification efforts. Investment was financed by taxation with graduated progressive consumption taxes on luxury goods and a housing construction tax that taxed small apartments at 2% and luxury apartments at up to 36%. Social-democracy not only targeted the decommodification of housing offensively, but was also socio-culturally transformative. The decommodification of housing went hand in hand with social policies and a proletarian counter-culture, promoting the pride of the working class (Kadi, Citation2018), introducing new gender roles, and reforming school education, social assistance and public health. Due to this comprehensive transformative agenda, Red Vienna faced fierce resistance from the political Right, the Christian Social Party, monarchists, German nationalists and the Nazis (Wasserman, Citation2014), leading to its defeat in a short civil war in 1934.

Welfare capitalist urban reformism (1945–1980s)

The lessons taken from the civil war, fascism and prolonged class antagonism were a class compromise, leading to the corporatist regulation of welfare capitalism adjacent to and spatially constrained by the Iron Curtain until 1989. Local manufacturing remained strong. Specific zones for the manufacturing industries were set up at Vienna´s periphery, including a significant expansion of the road system, while dismantling tram lines. From the 1960s onward, and due to the declining resident population, immigration of mainly unskilled workers from what was then Yugoslavia and later also from Turkey was promoted. At the same time, in the inner district, the service sector expanded rapidly from the 1960 onward, increasingly replacing local manufacturing. (Eigner & Resch, Citation2001)

Throughout this period, the Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) ruled with absolute majority, but integrated the ÖVP, the successor party of the Christian Social Party, in urban policymaking. Postwar municipal policies retained Lueger’s decommodified technical infrastructure, extended Red Vienna’s decommodified housing policies to the middle classes, and improved decommodified social infrastructures, especially health and education.

A structural shift toward decommodification

In postwar Keynesianism, decommodification in the housing sector was accompanied by the expansion of other decommodified provisioning of social infrastructures and related services—e.g., free access to health centers and university, free distribution of schoolbooks. Affordable, in part even free, access to housing, health and education was gradually expanded to more and more layers in society, thereby increasing purchasing power.

Social housing policy became the core of post-World War II reconstruction efforts and turned housing at least partlyFootnote11 into a social right (Gutheil-Knopp-Kirchwald & Kadi, Citation2017; Schwartz & Seabrooke, Citation2009). Although statistically, sufficient housing existed in Vienna, in practice, with numerous new and mostly smaller households being established, there was a significant shortage until the 1960s (Matznetter, Citation2019). New council housing, in which apartments were permanently withdrawn from the private market, was constructed to prevent commodification, and the expansion of the limited-profit housing sectorFootnote12 limited commodification. In the Austrian corporatist model, subsidized housing construction allowed for compromises between social-democrats and ÖVP: the former favored the construction of subsidized rental housing and the latter the construction of subsidized condominiums (Kadi, Citation2018). Residential construction was financed through a mandatory levy for all employees (1% of ancillary wage costs).

The reenactment of Austrian tenancy law of 1922/1929, whose origins lay in the First World War, further limited commodification, freezing rents for apartments built before the Second World War, and protecting existing tenants—although these immobilized parts of the rental market led to (sometimes) illegal methods of commodification, like subletting and high compensation payments for cheap rents (Matznetter, Citation2019, p. 19). Social housing was opened to the middle classes. Private housing stock was substantially upgraded, from the installation of electricity, water, and gas to bathrooms and toilets, with very little proper investments by homeowners.

A “modern” mode of livingFootnote13

Postwar social housing policy was shaped by Austria’s conservative welfare state, including the reconciliation of different interests (corporatism), the key role of the family (based on the male-breadwinner model) and a stable political order (based on mass parties) (Kadi, Citation2018). Inclusive growth strategies that focused on resource-intensive durable consumption goods as well as decommodified social infrastructures benefitted almost all classes by increasing wages, incomes, profits, pensions, and welfare services. Social advancement manifested itself in Fordist mass consumption: a private car, household utilities (TVs, refrigerators, etc.), and holiday travel. The understanding of a good life was materialistic, based on homogeneity, welfare, and mass consumption.

Collective bargaining and full employment extended a middle-class lifestyle to large segments of the working class and migrants, in part even those with low formal qualifications. This “middle-class-appropriate” lifestyle enabled a shared self-consciousness: a strong work and family ethos, upward social mobility for many, and increased “status investments,” e.g., in the form of real-estate loans for home ownership (Reckwitz, Citation2019, p. 76). Postwar modes of living stressed loyalty to given institutions, be it family or country (Reckwitz, Citation2019, p. 98f). “Normality” and order, conceptualized as steady professional career and a predictable life path, pervaded all spheres of life: consumption and leisure, work and family, dwelling as well as gender relations (cf. Whyte, Citation2002). This required social control and the individual’s integration into cohesive arrangements (Reckwitz, Citation2019, p. 77). Non-conformity was socially devalued and rejected as a form of extremism.

Neoliberal urban regeneration (1980s onward)

In 1988, Vienna recorded its lowest population level in the 20th century with just 1.48 million inhabitants and was one of Europe’s oldest cities demographically (City of Vienna, Citation2019). Since then, Vienna’s population has increased significantly, not least due to immigration—mainly from neighboring countries, east-central and south-east Europe as well as Turkey. Today, Vienna is heading toward 2 million people.

Despite considerable job losses in the secondary sector, employment increased, primarily due to the expansion in “finance and credit, private insurance and economic consulting” as well as “personal, social and public services.” Between 1995 and 2003 almost 17% of newly created jobs emerged in the creative industries (Falk, Citation2006). This tertiarization shifted the focus back to the inner city and changed the stable political setting of postwar welfare capitalism. Vienna’s economic-policy focused on overcoming the traditional domestic-market orientation and mass city tourism became increasingly relevant. (Eigner & Resch, Citation2001)

After decades of absolute majority, votes for Vienna’s SPÖ dropped to less than 40% in 1996, resulting in a coalition government with ÖVP that embraced New Public Management and neoliberal reforms (Novy et al., Citation2001). From 2001 to 2010, Social Democrats governed alone again, and since 2010 they have formed a coalition with the Greens that has defended most decommodified technical and social infrastructures (Plank, Citation2019). However, this large decommodified welfare sector became increasingly entangled with market-enhancing policies (Peck et al., Citation2013).Footnote14 The rise of a “post-modern” mode of living, opposed to the rigid socio-cultural structures caused by cultural homogenization in the postwar period, was more favorable to commodification in certain spheres of life. The desire for cultural differentiation and self-realization as well as ecological concerns became increasingly topical in discourses on and policies of neoliberal urban regeneration.

A structural shift toward commodification

A long period of enlarging and stabilizing decommodified urban infrastructures was followed, from the 1980s onward, by pressure toward commodification. Emblematic examples in the field of housing were:

(1) To increase housing supply by attracting private investment for urban regeneration, diverse constellations of national governments weakened Austrian rent control and/or transferred competences to the federal states (Bundesländer). This reduced tenants’ security with respect to the price and stability of housing and instigated a coerced mobility. Fully-equipped dwellings in the highest category were excluded from rent regulations, short- and fixed-term tenancies were facilitated (Reinprecht, Citation2014, p. 65), and the ability to charge extra premiums for quality- and location-related considerations introduced (Kadi, Citation2015, pp. 253ff; Matznetter, Citation2019, p. 22). Rents increased, especially for new contracts in private rented dwellings (Tockner, Citation2017, p. 12) and land prices exploded.Footnote15 Furthermore, “soft urban renewal”—a large municipal program to subsidize refurbishment investments in private substandard dwellings, introduced by the municipal government in the 1970s—offered long-term potential for rent increases and thus rent gaps (Kadi, Citation2015, p. 255; Hatz, Citation2019), although subsidy-receiving landlords were obliged to cap rents for incumbent residents for 15 years. The program was so successful that it kicked off unsubsidized renovations, which were not subject to rent regulation (Kadi & Verlič, Citation2019, p. 41).

Digital platforms have further contributed to the erosion of tenancy law by offering apartments as “vacation rentals” that sit outside rental regulations, effectively circumventing the scope of tenancy law. Airbnb is one such platform that attracts higher returns for rental properties than otherwise possible, thus removing them from the housing market. Via virtual spaces, private apartments are traded by residents, profoundly changing the spatiality, physical access, governance and use of housing and neighborhood (Cócola-Gant, Citation2016; Wachsmuth & Weisler, Citation2018). Between 2014 and 2017, Airbnb listings increased by 560% (Kadi et al., Citation2019). While some Viennese Airbnb operations are “home-share,” 26.7% of all listings are entire units rented on a permanent basis. Commercial providers dominate in traditional tourism neighborhoods (Kadi et al., Citation2019, p. 18f).

(2) Fiscal constraints triggered privatization. In 2004, the municipality terminated the building of new council housing (Kadi, Citation2018). Subsequently, construction has been undertaken by limited-profit housing cooperatives or private for-profit providers. Despite public subsidies, limited-profit housing is less affordable than council housing, and thus closer to the commodified private housing market, as tenants have to make down-payments (Kadi, Citation2018). Furthermore, allocating subsidies for social housing to for-profit developers (who can remove rent regulations after 30 years for new leases) as well as the option to buy rental apartments after 5 years (introduced in parts of the limited-profit housing sector) opens the possibility for private appropriation of real-estate valorization. Home ownership benefits middle and upper classes (Aalbers, Citation2017, p. 145) and offers in principle a secure life-long habitat. Yet, privatizing is often the first step to transforming an immobile dwelling with a specific use value into a mobile asset, commensurable and exchangeable like any other financial asset. It creates fertile ground to turn “the fixed and immobile property of built environments into spheres of liquid investment” (Clark et al., Citation2015, p. 11).

(3) The deregulation of financial markets as well as dwindling interest rates and investment opportunities after 2008 have stimulated the financialization of housing and impelled investments in “concrete gold”—asset-based rent-seeking (cf. Forrest & Hirayama, Citation2015). A recent study (ÖNB—Österreichische Nationalbank, Citation2019) calculated a 26% overvaluation of real estate in Vienna, a sign of a potential bubble.Footnote16 The resultant mortgage debts reinforced responsibilization. This individualized asset-based welfare strategy assumes that individuals take personal responsibility for financial self-improvement, which therefore depends on individual financial endowment (Heeg, Citation2017). Responsibilization integrates households into global financial markets (Ronald et al., Citation2017). National tax incentives (e.g., deductibility of loan interests, writing off abandoned property) have further intensified financialization in residential real estate (Aigner, Citation2019).

The structural shift toward commodification in some parts of Vienna’s housing segment has been part of a neoliberal strategy of urban regeneration, which all too often served to exploit the rent gap. Following this logic, urban regeneration strategies have taken up climate challenges to commercialize “green living” as a market-good (Luke, Citation2005; Quastel, Citation2009). Resultant “green” gentrificationFootnote17 has changed neighborhoods, not only in housing structure and urban infrastructure, but also in residential composition, due to the expulsion of incumbent, often low-income residents (cf. Gould & Lewis, Citation2017; Wolch et al., Citation2014). Therefore, neoliberal urban ecological regeneration strategies are double-edged: although they improve the habitat, respond to ecological challenges and increase quality of life (for those who can afford it), they are conducive to a profit- and market-logic and thus act as a driver of segregation. Under these conditions, ecological sustainability is not “an obstacle to capitalist accumulation, but rather a constituent part of it” (Gibbs & Krueger, Citation2007, p. 103), with the effect that the provisioning of an improved quality of life rests on individuals’ ability to pay, and is thus exclusionary: within such an infrastructural configuration, an ecologically sustainable and socially just city seems mutually incompatible.

A “post-modern” mode of living

The liberalization and commodification tendencies in the housing market co-evolved with increasing cultural differentiation, post-materialism, and new gender roles. In Vienna, new (subsidized) housing constructions such as FrauenwerkstattFootnote18 I (1997/98) and II (2004), car-free living (1999), intercultural living (1996) and multi-generational living (2000) are examples of themed housing projects that are conceptually based on post-traditional ideas of a differentiation of lifestyles (Reinprecht, Citation2019, p. 26ff). Contrary to the mere satisfaction of basic needs in the postwar period, housing became increasingly a place for individual identity formation as well as the expression of new life paths and alternative living arrangements (Reinprecht, Citation2019). Demands for individualization, autonomy and self-realization became new guiding values. This “post-modern” mode of living is mobile and cosmopolitan, diversity-sensitive, green in principle, globalist in outlook, “creative” and open to innovation, aiming at well-being in an integral way: a job that “fulfills”; food that is organic, esthetic, and ethical; parenting that seeks to unfold diverse talents (Reckwitz, Citation2019, p. 93). It seeks to leave behind and nullify (oppressing) norms of the past by emancipation from traditional collective categories (e.g., citizenship, family, ethnicity, gender).

While this “post-modern” value system transcends collective norms and standards, it becomes increasingly market-compliant under contemporary neoliberalism. Already in 1989, Zukin (Citation1989, p. 68) observed that the “mass production of the individual” gives way to an “individualization of mass production.” The search for the unconventional and singular on the demand side conjoins the search for rent gaps on the supply side. The distinction-seeking “post-modern” middle-class valorizes consumer sovereignty and singularity, including the current appreciation of ecological sustainability. “Green living” is reduced to a special, to be curated, lifestyle; a form of self-realization and a cultural good acquirable through the market. Places are increasingly viewed and bought for reasons of socio-cultural reputation (Savage et al., Citation2005, p. 207), thus triggering class-biased ecological lifestyles (Gould & Lewis, Citation2017, p. 112).

Two modes and an impasse: Segregation and anachronism in Vienna

Let us briefly recapitulate the developments that have led to the present situation. The construction of decommodified technical and social infrastructural configurations paved the way for Vienna as a modern city. It emerged out of severe social and political conflicts, leading to an accommodation of class struggle by homogenizing modes of provisioning. These infrastructural configurations satisfied basic needs through affordable, in part even free, access to housing, health, and education. This freed up expendable income, which simultaneously fostered capitalist improvement and shaped a mode of living oriented to mass consumption as well as an orderly and predicable professional career and life-path. In parts of Vienna, this mode of living, hereafter called “traditional,” has survived, especially at the periphery. From the 1980s onward, hyperglobalized finance capitalism has transformed welfare capitalism, creating pressure toward commodifying infrastructural configurations, and social movements have challenged the conformist postwar societal order, thereby giving rise to a “post-modern” (hereafter “liberal”) mode of living, concentrated in inner-city neighborhoods.

In what follows, we first analyze the coexistence of these two modes of living in Vienna, showing increasing antagonisms leading to conflicts, uneven spatial configurations and contradictory multi-class alliances. Subsequently, in the face of accelerated ecological threats, increasingly insecure labor and housing markets and brittle social cohesion, we analyze their anachronism, i.e. their incongruity in the current historical conjuncture.

Segregated coexistence

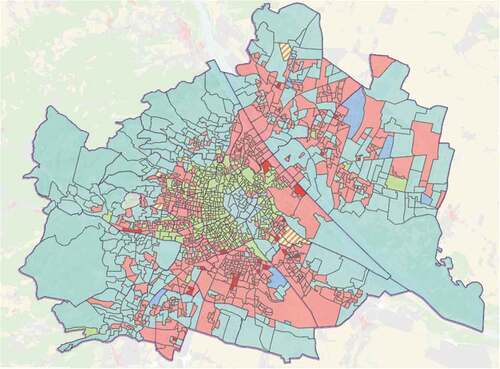

Taking Vienna’s voting behavior as a rough proxy, spatial patterns of these modes of living can be identified. Both coexist in a segregated way. Social democracy is still the strongest party, well represented in all parts of the city. However, while liberal Green-voters are concentrated in inner-city neighborhoods,Footnote19 the outer city has become a stronghold of right-populist FPÖ, replaced by increasingly populist ÖVP in the 2019 national elections. shows this voting pattern.

Figure 1. Voting behavior in the 2019 national elections (green = The Greens; red = social democratic SPÖ; turquoise = conservative-populist ÖVP; blue = right-populist FPÖ); map retrieved from Vienna City Administration (Citationn.d.).

Vienna´s inner city (marked as predominately green/green-red in ) is characterized by a built environment that goes back to the 19th century, with less social housing, a higher share of migrants, dynamics of gentrification and a specific mode of living that has co-evolved with ecological infrastructural configurations in these areas (e.g., densification of public transport, cycling lanes, and extension of pedestrian and shared zones). In terms of modal split, inner-city districts have a high incidence of walking (33%), cycling (9%) and public transport (41%), while motorized private transport is relatively low (17%; WUA—Wiener Umweltanwartschaft, Citation2016). The high proportion of Green-voters suggests an attitudinal and social basis that is highly educated, typically working as social-cultural specialists with a distaste for hierarchy, emphasizing self-realization and having environmental, libertarian and pro-immigration inclinations (Dolezal, Citation2010). This liberal mode of living not only places specific demands and expectations on residents (e.g., tolerance of diversity, the embrace of change and innovation), but also on its living environment: housing is considered more than comfortable private dwellings, but something ideally integrated into a lively surrounding offering attractive possibilities for unique cultural, educational and leisure experiences. As an unintended consequence, these expectations have supported market-compliant strategies of neoliberal urban regeneration. The race for innovation and sustainability, and for the new and exceptional, has led to an influx of premium office spaces, gentrification, privatization and individualization, but has also fostered the development of ecological, but partially exclusive, living environments for a like-minded educated middle class.

Vienna´s outer city (marked as predominately turquoise/turquoise-red in ) has long been the stronghold of the working class, with substantial council housing and increased limited-profit construction. Today, it features a type of working- and middle-class mode of living based on mass-consumption, motorization, and—if possible—private amenities, which again has co-evolved with infrastructural configurations in these areas (e.g., less socio-culturally differentiated housing arrangements as well as cultural, educational and leisure facilities, less densified public transportation networks, more highways and thoroughfares). For example, in the South of Vienna, the shares of walking (24%), cycling (4%) and public transport (33%) are markedly lower than in inner districts, while motorized private transport is substantially higher (39%) (WUA—Wiener Umweltanwartschaft, Citation2016). A study conducted by the Vienna City Administration (Citation2007) highlighted important traits of this traditional mode of living in the outer city: an appreciation of low density, orderliness, social homogeneity, and the possession of private gardens or terraces. Compared to inner-city areas, the availability of retailing and cultural institutions is restricted, though perceived as sufficient. The traditional mode of living comprehends good habitation less in terms of an attractive and exciting common living environment than as a private living environment of good quality. It often rejects environmental policies as “elitist” and tends to resist changes to the fossil-fuel based mobility and energy system. This mode of living is more sedentary, defending “normality” in the way things have to be done. It sympathizes with traditional gender roles and communitarian, often nationalist, sometimes even racist, world views. In the study, more than half expressed a feeling of belonging to the suburban part of Vienna, not the city itself. Social change through any influx of lower-income residents is feared, especially of migrants. Right-wing populist scapegoating is commonplace.

As a means of demonstration, Vienna’s 7th (inner city) and 23rd district (suburbs), “Neubau” and “Liesing,” exemplify these diverging socio-spatial dynamics. Although these districts are certainly not homogenous with regards to their modes of living, a liberal mode of living is dominant in Neubau and a traditional one in Liesing. While there are few differences in average per capita income, marked variations appear in built environment, population density and composition, political leanings, living arrangements and environments, as well as international reputation. Neubau is a densely populated inner-city area, a “colourful clutch of the young and trendy,” known for its “multicultural and vibrant” atmosphere and its “abundance of edgy cafés and minimalist restaurants full of bright young things in the evenings” (Culture Trip, Citation2018); “a fashionable neighbourhood for students, intellectuals and creative industries” (TourMyCountry, Citationn.d.b). Liesing, in the South, is less densely populated, hard to find in any standard guidebook except “somewhere on the edge” and consisting “mostly of highways, vast commercial areas, ugly apartment blocks, more highways and shopping centers” (TourMyCountry, Citationn.d.a).Footnote20 summarizes and compares selected characteristics.

Table 1. Data from Taxacher and Lebhart (Citation2016) and VCÖ (Citation2018).

To sum up, green-liberal aspirations dominate (amidst other aspirations) in the densely populated, culturally diverse, but increasingly gentrified inner city, which also remained home for the majority of the diverse migrant population,Footnote21 while traditional values and respective parties are strong on the periphery, especially in former strongholds of social democracy. As proponents of liberal avant-garde lifestyles often degrade traditional ways of life, and adherents to traditional modes of living increasingly accept exclusionary and authoritarian policies, their understanding of habitation differs profoundly. Conflict is unavoidable.

Anachronism: Two modes out of tune

Although the traditional and liberal modes of living coexist, in the current conjuncture both have become dysfunctional to an increasing part of its proponents.Footnote22 The former was created under a Fordist mode of regulation, with strong trade unions, full employment, a policy focus on long-term investment, a solid public sector, and extensive decommodified social infrastructures. This welfare-capitalist conjuncture enabled order, i.e. a steady professional career and a predictable life path, to become the central social norm. Since the 1980s, however, this norm has been threatened by political-economic and socio-cultural dynamics. First, financialization and hyperglobalization have led to fiercer locational competition, short-termism due to shareholder value-orientation, increasing unemployment, flexibilization, and job insecurity. As a result, traditionalists attempt to conserve the status quo with ever more aggressive, exclusionary and scapegoating practices (Blühdorn, Citation2020; Brand & Wissen, Citation2018), seeking to limit social protection to ever smaller parts of the (domestic as well as global) population. However, rapidly emerging economies in the Global South, fiercer geopolitical competition as well as a strong urban-policy orientation toward attracting and retaining international investors and highly mobile knowledge workers in competition with other “global” or “knowledge” cities increasingly undermines the successful pursuit of such an exclusionary strategy—as exclusion becomes reflexively a potential threat to themselves. Their socio-economic stability and order becomes more endangered than ever. Second, socio-culturally the traditional mode of living is on the defensive too: its core principles have lost their former social dominance in increasingly differentiated and “liquid” (Bauman, Citation2012) post-modern societies, triggering conflicts about socio-cultural hegemonies (Reckwitz, Citation2019, p. 67). Environmental policies and green values are denounced as “luxuries,” apparently solely promoted by a liberal-elitist minority. There is a nostalgic yearning for order, for how things “used to be,” including those habits and routines that lead to an unsustainable ecological footprint.

At the same time, the neoliberal shift from government to market-compliant forms of governance beyond the state (Jessop, Citation2002, p. 455; Swyngedouw, Citation2005, p. 1992) biased contemporary ecological challenges as problems of market choice. Given the unequal distribution of income and wealth, this tends to reinforce a hierarchic character in access to consumer goods, with exclusionary and segregating consequences. Contemporary policy-focus on market solutions and locational competition, has first and foremost empowered solvent innovation-friendly residents, institutional investors, and large corporations, thereby creating possibilities for the exploitation of rent gaps as a strategy of urban regeneration.Footnote23 This has hindered access to affordable housing for the working class, but also an increasing part of the middle classes. Therefore, the liberal aspiration for self-realization has become dependent on individual purchasing power, which makes its achievement not only illusory for many, but, remaining consumption-oriented, also unachievable for broader parts of the population within ecological limits. Therefore, in this neoliberal conjuncture of market-driven urban development, neither mode of living manages to deliver what their protagonists aspire to.Footnote24

Social-ecological infrastructural configurations and new modes of living: Learning from the case of Vienna

In this section, we propose social-ecological infrastructural configurations—sustainable, affordable and/or accessible for all—as a pathway toward a social-ecological transformation, enabling new modes of living through decommodifying modes of provisioning. Given the climate crisis and neoliberal financialization, such an approach must transcend Vienna’s timid reformism. Today, mainly defending projects of the past that decommodified parts of technical and social infrastructure provisioning, is insufficient. Novel courageous attempts toward decommodifying modes of provisioning, including ecological infrastructures, are required and must be accompanied by multi-scalar policies that limit resource-intensive individual consumption (e.g., through taxation of high-carbon luxuries) to have positive ecological effects. Hence, extending the sphere of decommodified and inherently collective social-ecological infrastructures, while reducing the sphere of private consumption, is at the core of an eco-social strategy, because there is strong evidence “that public consumption is more eco-efficient than private consumption” (Gough, Citation2017, p. 163). As this challenges fossil- and finance-dominated power blocs, its actualization depends on active alliance-building between specific societal actors by improving social-ecological infrastructural configurations. This appeals to popular, but increasingly frustrated, interests and aspirations of both modes of living, enabling new and broad political alliances, from “below” and “above.”

The limits of timid reformism

Historically, the successful tackling of common challenges has rested on political struggles for different forms of collectivization in “collectivist” periods (Polanyi, Citation1944/2001, p. 191), leading to several regulations that decommodified parts of infrastructure provisioning in central economic sectors and spheres of everyday life. Learning from these historical experiences, both, public policies that implement social-ecological infrastructural configurations as well as social struggles that demand and co-create them, can inspire a political project that pursues three interrelated policy objectives which have to be addressed on multiple scales:

Urban development based on offensive decommodification secures, maintains, partially rebuilds (e.g., through pedestrian and shared zones), and expands (e.g., via platform cooperativism and commoning) the decommodified technical infrastructures of the 19th century.

It defends and partially restores the decommodified social infrastructures of the 20th century, while implementing policies that define urban citizenship as material and social rights to the city for its workers and residents.Footnote25

It constructs an accessible and/or affordable urban environment for an ecological transformation based on green and public spaces as well as decarbonized housing and modes of mobility. At the same time, resource-intensive infrastructures that maintain current unsustainable mobility, energy and food systems have to shrink and limits on individual consumption need to be imposed.

Defending existing municipal ownershipFootnote26 remains a key component of Vienna’s collective provisioning of basic needs. Given the ongoing threat of further liberalization via European competition law, which creates constant pressure to constrain public housing provisioning even while accepting social housing as a service of general economic interest (Shah, Citation2019), the City of Vienna lobbies for an improved supra-local policy framework, e.g., by supporting the EU-wide citizens’ initiative “housing for all.” Furthermore, to reduce socio-economic vulnerabilities caused by more flexible labor markets, global competition and financialization, thereby limiting commodification, the City of Vienna offered equity replacement loans (reducing financial barriers for low-income earners to enter the limited-profit housing sector) and subject-linked cash benefitsFootnote27 as a form of needs-based allocation. The municipal government is further trying to intervene in commodification through its new building law amendment, enacted in 2019, which introduced a new zoning category, “subsidized housing construction,” applying to all future construction projects zoned as residential or mixed building areas. All construction projects of 5,000 square meters and more have to dedicate two-thirds of their area to subsidized housing in which rents must not exceed €4.97 net per square meter (as of 2019), land prices are capped at €188 per square meter of gross surface area (for 40 years), and apartments are subject to a ban on resale. While not interfering with existing zonings, the new instrument changes profit expectations (e.g., for rent gaps) for future construction projects and re-zonings, thereby capping rental and land prices, devaluing housing and land as a commodity, and encouraging investment in affordable housing provisioning.

While these regulations are crucial building blocks to tackle challenges posed by neoliberal attacks on common modes of provisioning, they fail to address key drivers of the climate crisis. Diverse counter-movements to prevent commodification have remained limited, like 4,000 new council apartments, planned for 2020, and self-organized construction projects (such as “habiTAT”Footnote28) which seek to isolate housing provisioning from the real-estate market (and thus from speculation and personal enrichment) through democratizing its ownership, use and maintenance. The last substantial offensive decommodification, appealing to broad segments of Vienna’s population, with lasting beneficial social-ecological consequences occurred in the 1980s with the construction of Donauinsel, a huge artificial recreational island with free access for all. Over the last years, a key climate policy has been the affordable €365 annual public-transport ticket which has led to the increase of sold annual tickets from 363,000 (2011) to 852,000 (2019; Wiener Linien, Citation2020). However, while Vienna has an excellent public transport system, urban policy has never abdicated car-centric transportation policies. Given the scarcity of urban space, this has resulted in only modest expansion of cycling lanes and public spaces.

To put it in a nutshell, policymaking has remained timid, predominantly focusing on (1) the protection, maintenance and partial rebuilding of the decommodified technical infrastructures of the 19th century and (2) the defending of decommodified social infrastructures of the 20th century, thereby mainly capitalizing on past achievements. It has been too fainthearted given the climate crisis and neoliberal financialization, which require more social pressure “from below,” new narratives and more radical policies on multiple levels to disrupt the dominance of finance, real estate, and fossil-fuel-dependent capital that currently structure modes of provisioning and private consumption. Only broad alliances of civic movements, political actors, and public authorities can change dominant discourses, institutions, and power relations on different levels—and therefore restructure regulations of infrastructure provisioning toward sustainability and inclusiveness.

A political project for social-ecological infrastructural configurations

Today, conflicts with respect to ecological transformations, like pedestrian and shared zones, are predominantly framed as socio-cultural conflicts between liberal and traditional world views—in Polanyian terms, conflicts about the form of habitation. Although both the traditional and liberal modes of living are structurally dependent on market-compliant behavior, focusing on social-ecological infrastructural configurations in policymaking as well as political mobilization might appeal to central, but increasingly frustrated, socio-cultural determinants of traditional and liberal modes of living. A successful social-ecological transformation has to incorporate diverse “interests and aspirations” into a “common world outlook” supported by “dominant classes,” “social categories,” and “significant social forces” (Jessop, Citation1990, p. 43). Therefore, “different but similar” narratives (Hajer, Citation2006, p. 71), carrying and (re)producing ways to make sense of the world, can re-solidify those bonds which “interlock individual choices in collective projects and actions” (Bauman, Citation2012, p. 6) to tackle common eco-social challenges such as the climate or housing crisis. This discursive strategy makes new ‘discourse coalitions’ (Hajer, Citation2006, p. 66ff) for a social-ecological transformation possible. Hence, in what follows, we construct two differentiated, but mutually affinitive narratives around a potentially hegemonic project of social-ecological infrastructural configurations.Footnote29

Reframing the traditional narrativeFootnote30

We argued that traditional interests and aspirations for a steady professional career and a predictable life path are increasingly under (actual and perceived) threat. Contemporary hyperglobalized finance capitalism undermines the traditional order in general, including “the ‘ordinary’ moments of social reproduction which play host to nostalgic ambivalences and persistent yearning” (Jarvis & Bonnett, Citation2013, p. 2366). Over the past decades, infrastructural investments focused on increasing connectivity over space, thereby reducing time in circulation of commodities. This enabled contemporary hyperglobalization with its resource-intensive mode of production, communication and transportation networks. As a result, increasingly complex, global supply chains created unstable international dependencies (as has become evident during the Covid-19 crisis) and restrained access to good domestic jobs and social protection, thereby making socio-economic stability and predictability increasingly difficult. The resultant dissatisfaction drives collective and political radicalization in favor of more stable and predictable socio-economic arrangements. A solidaristic movement in line with a foundational approach is based on territorialized infrastructural configurations of a “grounded city” (Engelen et al., Citation2017) that enable place-building as well as local forms of sense-making and belonging rather than space-annihilation and outsourcing.

Social-ecological infrastructural configurations have the potential to chime with such yearnings. These configurations are inherently place-sensitive, conserving, nurturing and building sites of identification and meaning in context-sensitive ways: from decentralized public care and health facilities, where one meets familiar faces, to local sports venues and the pub around the corner as social meeting points; from localized repair shops as well as the bakery and corner shop nearby, allowing for more regular grocery shopping of smaller quantities, thereby making the use of a car less attractive, to localized green recreational centers and affordable public ponds in the district.

What is more, social-ecological infrastructural configurations offer an alternative socioeconomic foundation that is compatible with traditional values. In this regard, it is decisive to expose how dependent the traditional mode of living is on decommodified configurations of social infrastructures. The collectivist postwar period was more prone to individual upward mobility and societal stability, while currently such aspirations can only be met by an increasingly shrinking segment of traditionalists. By strengthening and decommodifying the “foundational urban systems” that provide “the critical goods of everyday life” (Hall & Schafran, Citation2017, p. 2), social-ecological infrastructural configurations support and sustain the foundational economy (Foundational Economy Collective, Citation2018). This foundational economy facilitates and strengthens the vital, i.e. welfare-critical, but often neglected, mundane aspects of a civilized life, enabling and foregrounding those daily activities that are the same for everyone and on which all inhabitants rely: from electricity, water, and housing to local food supply, health, and care. This shift in focus toward a grounded city may consequently reduce “opportunities to compare one’s consumption with other and richer groups, which is one of the drivers towards hyper-consumption” and ecological cataclysm (Gough, Citation2017, p. 162 f). A grounded city is appreciated by its internal ability to distribute mundane goods and services not by furthering international competitiveness through city branding, large financial centers and over-tourism. Hence, it prioritizes everyday human needs, satisfiable through collective provisioning, over individual consumer preferences, met through individualized market provisioning, “if the two conflict or if resources are scarce” (Gough, Citation2017, p. 4). Such a prioritization implicates positive ecological effects since “meeting needs will always be a lower carbon path than meeting untrammelled consumer preferences financed by ever-growing incomes” (Gough, Citation2017, p. 13). Decommodifying modes of collective provisioning not only reduces costs of living, but also prioritizes long-term economic thinking, planning, cooperation, and a focus on resilience rather than short-term profit maximization for certain groups and unconditional competition. As such, foundational-economic activities constitute capitalism’s non-capitalist foundation, preventing its self-destruction (Streeck, Citation2017) and, already today, generating 40% of all jobs (Foundational Economy Collective, Citation2018, p. 24)—jobs that are almost entirely locally and regionally anchored.

Reframing the liberal narrative

We argued that the liberal aspiration for self-realization and “uniqueness” is increasingly unachievable in an era of market-driven urban development. Self-realization then becomes reliant on sufficient purchasing power, illusory for large parts of the working class, but also increasing parts of the middle-classes. A reframed liberal narrative has to expose how commodified provisioning counteracts efforts toward self-realization and how the decommodification of social-ecological infrastructures is conducive to restoring it.

Following this line of argument, if self-realization is the aspiration, many of those who follow a liberal mode of living are better served by restoring the collective ability of self-determination (cf. Gräfe, Citation2019, p. 81), i.e. the ability to democratically restructure—“through institutionally coordinated processes of contestation, deliberation and collective will-formation” (Hausknost & Haas, Citation2019, p. 11)—the very terrain on which self-realization can unfold in the first place. Broad public participation can shape social-ecological infrastructural configurations. Politicizing the quality of and access to social-ecological infrastructures is therefore necessary to restore the capacity of self-realization. Bottom-linked political agency combines bottom-up mobilization and top-down policymaking. Institutionalizing innovative and creative initiatives has the potential to empower self-realization in more qualitative, use-value terms—conferring more free time instead of increasing wages,Footnote31 accessing public goods instead of possessing private ones, and reducing costs of living instead of raising purchasing power. The focus thus shifts from (highly constrained forms of) self-realization through market choice within already marketized infrastructural configurations to self-determination through systemic decisions on infrastructural configurations as such.

For example, certain inner-city neighborhoods, even in parts of Neubau, are still characterized by lower life quality due to high noise and air pollution, and inhabited by those groups—predominately migrant, less formally educated and low-income—who can only afford modest rents (Stadtentwicklung Wien, Citation2016). Following rent-gap theory, these inner-city neighborhoods are prime candidates for ecological gentrification with stratifying consequences for residents,Footnote32 if left to market choice. But they could also, through decisions on social-ecological infrastructural configurations, including tenant-friendly rent regulations (a “top-down” policy), be transformed by social movements and participatory policies (“from below”) into mixed neighborhoods, innovatively designed according to local needs and accessible to all.

(Visionary) outlook

Our Polanyi-inspired analysis of historically arisen infrastructural configurations is conducive to understanding and shaping urban transformations. It illustrates how political-economic regulations of (de)commodification interrelate with specific socio-cultural modes of living. By tracing the origins of these modes of living and discussing their effectiveness in satisfying deeply engrained self-defined aspirations in contemporary conjunctures, it exposes prevailing fallacies in accomplishing these aspirations. This helps to formulate narratives appealing to while simultaneously reframing interests and aspirations, thereby creating new discursive affinities for broader alliances. In this sense, a focus on social-ecological infrastructural configurations can mobilize social and political movements as well as public authorities and is conducive to overcoming the dualism between minor improvements (reforms) and profound re-ordering (revolution), thereby acknowledging that alliances and alternative hegemonies need to incorporate popular interests and aspirations rather than merely “working to reinforce the revolutionary movement” (Jessop, Citation1990, p. 42). A political project for social-ecological infrastructural configurations overcomes “the destructive and self-restraining dualism of incremental and radical change, … of small steps within the existing order and major advances of radical change” (Novy, Citation2019, p. 126 f), thereby enabling, in progressive steps, a “good life for all.”

First, social-ecological infrastructural configurations have a civilizing effect on capitalism, contributing—in certain contexts—to the satisfaction of basic needs in a decommodified and social-ecologically sustainable way. The actualization of this potential, however, depends on struggles against the fossil- and finance-dominated power blocs. These struggles can only be successful if (1) key political actors like social movements, political parties, trade unions and other civic initiatives adhere to a narrative that unites proponents of different modes of living, and if (2) this narrative for decommodifiying social-ecological infrastructures (while limiting individualized private consumption) becomes institutionalized in practices and policies (cf. Hajer, Citation2006, p. 71). Reframed narratives, appealing to diverse popular interests and aspirations (ad 1) and the collective struggle for as well as the context-sensitive and participatory implementation and collective use of social-ecological infrastructures (ad 2) are crucial elements of effective social-ecological transformations.

While transformative agency has to be courageous to institutionalize new modes of living, a focus on differentiation and context-sensitivity can mitigate feelings of displacement and the fear associated with abrupt change. Context-specific forms of struggle for as well as implementation and use of social-ecological infrastructures are important. This refers to different cultural milieus as well as different types of neighborhoodsFootnote33: while eliminating fossil-fuel-based forms of mobility in Neubau would be a feasible medium-term vision, substantially reducing private fossil-fuel transport in Liesing would not only likely be disruptive but also presuppose major investments in the extension of public transportation; while art exhibitions in open cultural centers might be a desired recreational event in Neubau, watching a football game with family and friends at the local sports venue might, for many, be a more desirable recreational activity in Liesing. Gradual and context-sensitive implementation of social-ecological infrastructural configurations enable transformations at a moderate pace, acknowledging one of Polanyi (Citation1944/2001, p. 35ff) key insights: a wisely-tempered velocity is crucial for success. This is a viable recommendation to move beyond neoliberalism.