ABSTRACT

The Kenyan legal framework accords robust safeguards to private property rights. It is only in few cases that these rights may be limited. In Kenya, many informal settlements are on private land, which can limit the ability of residents to access life-saving basic services. Here, we explore how a public health emergency in Mukuru, one of Nairobi’s largest informal settlements, gave rise to a redefinition of private property, security of tenure and delivery of water and sanitation. We suggest that “everyday emergency” of public health threats in informal settlements offers an opportunity to ensure that property and planning norms deliver rights to both secure tenure and human health. Ultimately, we explore the place of public health in (re)negotiating for land rights in Nairobi, particularly to ensure that the urban poor can express their rights to health and well-being and assess what this portends for planners in their quest to upgrade informal settlements.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Understanding local conditions and vulnerabilities is imperative in any exercise that seeks to address health equity concerns. This is true for urban informal settlements whose landscapes already leave them vulnerable to infectious and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) with the natural outcome of widening the already existing gaps in health outcomes within cities (Ezeh et al., Citation2017). Informal settlements’ connections to the complex urban systems leave them exposed to diseases that may start elsewhere but find a ready host in the impoverished and non-responsive health and social safety systems of these communities. It is these concerns that have stimulated the adoption of varied approaches to understanding these settlements. Emphasis has been put on relational and context-specific approaches that put local knowledge and the inhabitants’ interactions with their living conditions at the fore when generating data (Corburn & Karanja, Citation2016).

Addressing gaps in provision of basic services has already been elevated in these approaches as a key entry point for containing infections and improving health outcomes within informal settlements (Corburn & Karanja, Citation2016; Fèvre & Tacoli, Citation2020). In fact, UN-Habitat (Citation2020) estimates that global pandemics such as the COVID-19 outbreak have reoriented focus on the vulnerabilities of the inhabitants of informal settlements and heightened calls to improve basic services and ensure the resilience of the inhabitants of these impoverished areas. Provision of basic services is quintessentially pegged on access to land and tenure security (Murthy, Citation2012). Indeed, some of the critical interventions that have been proposed in dealing with public health emergencies like COVID-19 entail restricting peoples’ movements. Governments have issued rallying calls to individuals to stay at home and observe basic hygiene. Having secure tenure is inevitably key to the success of these directives. However, with the current structuring of urban informal settlements, inhabitants are faced with practical difficulties in observing the directives. What we have witnessed is a majority of public health interventions habitually skirting around questions on tenure insecurity, which impedes realization of key proposals. COVID-19 has further unraveled these conventional public health approaches with this being accelerated by what we now see as the unequal impacts of public health crises on deprived urban neighborhoods.

By isolating land tenure as a key determinant of health, we build a case for tenure reforms and a guarantee of land rights for the inhabitants of informal settlements. We ascribe the bottlenecks in service provision that we are presently witnessing to the failure to orient land in the city to a more egalitarian form. Here, we take public health as an example and argue that the public health concerns, which we elaborate herein, provide a basis for tackling land distribution in Mukuru, one of Nairobi’s largest and most vulnerable informal settlements. As discussed here, Kenyan law provides for various ways through which threats to public health can be used to limit private land rights. For instance, public health concerns such as the threat of spread of infectious diseases would under the Kenyan Public Health Act (Cap 242) outweigh any protections that are accorded to the private land upon which the public health danger arises. Additionally, the Act in section 115 allows local authorities to enter the land to remove or to cause to be removed any nuisance or condition liable to be injurious or dangerous to health.

According to Galva et al. (Citation2005) these are “police powers” or development control powers which allow for limitation of private rights where there is need to preserve the common good, which here would be the preservation of public health. This common law doctrine is now entrenched in the Kenyan constitutional and statutory provisions, which limit property rights that are contained in Article 40(3)(b). As will be illustrated in this paper, the Land and Environment Court in Kenya has already held that public health concerns will override private property rights. It is these countervailing mechanisms that can be extended to enable access to land by the inhabitants of informal settlements to carry out such works that would facilitate provision of basic services like sanitation facilities, and hence address the identified public health concerns. So public health, whose outcomes are shaped by access to land, can also be invoked to occasion redistributive measures and hence eliminate the barriers to access to land for sanitation purposes.

Methods and data

In this study, we focus on the informal settlements of Mukuru Kwa Njenga, Kwa Reuben, and Viwandani (what we call here, Mukuru) located in the eastern parts of Nairobi. We relied on multiple data sources with our primary data source being the literature and data emerging from the Mukuru SPA process. We also engaged with the ongoing Special Planning process in Mukuru from which we were able to gather data on household living conditions in Mukuru, land tenure and health. Our participation in the SPA meetings was made possible through the support of Muungano wa Wanavijiji (the Kenyan affiliate of Slum Dwellers International) and the University of California, Berkeley. These two institutions have engaged residents of Mukuru in action research from which household data has been generated. The Health Services Consortium (HSC) of the Mukuru Special Planning Area also facilitated our access to health data generated over a 6-month period in 2018. In their research, the HSC administered two questionnaires to 966 participants. The questionnaires administered by the HSC specifically targeted individuals who inhabit the settlements, community interest groups such as Community Health Volunteers (CHVs), operators of private clinics, and people with special needs.

Through the HSC, participatory mapping was undertaken together with representatives from the community. This entailed mapping includes sanitation facilities, water access points, and drainage canals. In Mukuru, participatory mapping begins at the point where the community and external experts count and number each structure in the settlements. Existing infrastructure and services are also counted and numbered. Community mappers develop sketches of the settlements’ layout and indicate the location of existing infrastructure and services that they identify (Makau et al., Citation2012). These sketches are then overlaid on existing maps which are generated from freely available satellite images from sources like Google. According to Smith (Citation1984) involving communities in mapping is an acknowledgment that these communities must be at the center of decision-making. Mbathi (Citation2011) has further outlined the empowerment outcomes that can be derived from participatory mapping. He argues that participatory mapping plays the role of democratizing information, and it aids communities to identify local challenges and opportunities that they can use in improving their neighborhoods.

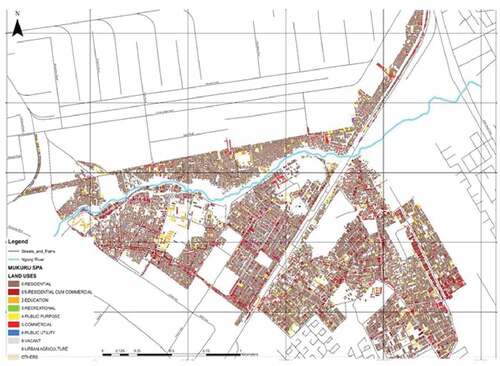

Mapping done by the HSC enabled the understanding of the nature of land use in Mukuru that is illustrated in . Our understanding of the land tenure situation was also facilitated by the information that we extracted from the land titles that we were able to obtain from the Ministry of Lands and which we subsequently analyzed. For the titles, we developed a data extraction form with which we were able to extract the relevant information that enabled us to understand the tenure security situation in Mukuru. The data extraction forms sought to gather information on the grant number, size of land, names of the landowners, and any changes that had been made on the ownership of the land. Once these data weregenerated, we analyzed the emerging land information and grouped the various tenure typologies identifiable in the Mukuru informal settlements.

Background: Expansion of informal settlements in Nairobi

UN-Habitat (Citation2014) projects that Nairobi’s population will reach 4.9 million by 2020 and 6.1 million by 2025, with growth rates exceeding 4.2% annually. Such rapid expansion occurs in a city where nearly 60% of the population currently lives in informal settlements, which collectively occupy less than 2.6% of Nairobi’s land area. Inadequate basic services in informal settlements, coupled with tenure insecurity and complex socioeconomic dynamics, have often hampered positive engagement between the Nairobi City County Government (NCCG) and the inhabitants of informal settlements. Within the informal settlements, wide gaps exist in provision of basic services with a number of these settlements such as Mukuru, Mathare, and others lacking state investments in sanitation facilities (Winter et al., Citation2019). A study by UC Berkeley, the University of Nairobi, and Muungano wa Wanavijiji (Citation2017) indicates that inadequate sanitation leaves certain categories of people particularly vulnerable to health and security problems, with women and girls being at higher risk of being sexually assaulted when trying to use a toilet without lighting or a lock at night. With the glaring shortfalls in provision of these basic services, cartels and informal providers readily fill the gaps and provide substandard services at unaffordable costs (Boakye-Ansah et al., Citation2019). This is also the case with healthcare services, where shortfalls have provided a booming business for unqualified healthcare service providers who offer unsafe services to a population that is already overburdened by diseases (Omulo, Citation2019).

Mukuru is one of Nairobi’s largest informal settlements, home to 100,561 households. Located on over 640 acres of private land in the industrial area, Mukuru regularly experiences fires and floods, alongside elevated levels of air pollution due to nearby factories. Flooding has multiple causes including Mukuru’s low-lying location next to the Ngong River, with some residents living on reclaimed land along the riparian reserve. Poor drainage and solid waste management only exacerbate flood risks as rubbish often clogs the already inadequate open drains. About 95% of the residents are tenants who rent rooms in single- or double-storey shacks, typically built of mud and/or galvanized iron sheets. Hazardous electricity connections are linked to Mukuru’s frequent fire outbreaks; fire risks are compounded by the area’s high-density shacks, paltry road networks, and limited access to emergency services. Residents usually have very limited access to water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) and typically endure long queues to access contaminated standpipes. Toilets are especially inadequate and present a health and safety hazard, especially for girls and women. Mukuru’s water and electricity networks are dominated by low-quality, often predatory informal service providers locally called “cartels” (UC Berkeley, University of Nairobi, and Muungano wa Wanavijiji, Citation2017).

Special planning area designation for informal settlements

Declaring areas in the city as Special Planning Areas (SPAs) is a critical intervention aimed at remedying the numerous challenges of public health, property rights and planning for informal settlements in Kenya. On August 11, 2017, the NCCG vide Kenya Gazette Notice No. 7654 declared Mukuru as a SPA. The declaration is anchored in the Constitution and the Physical Planning Act (Cap. 286, repealed) which in Section 23 granted powers to the county government to designate an area as a SPA if it is distinguished by unique development problems and environmental potential while also raising significant urban design and environmental challenges. The declaration would signal the start of a process to develop an Integrated Development Plan (IDP) for the SPA. For the SPA process, seven consortia were constituted to develop sector plans for the various key sectors in need of planning interventions.

A number of proposals have thus been made by the seven consortia with these proposals feeding into the IDP, which is currently being developed. These proposals have been informed by the participatory and consultative processes that have underpinned the work of the SPA consortia (Horn et al., Citation2018). Under the Mukuru SPA public participation framework, locally generated knowledge feeds into the expert-guided processes to co-produce proposals and interventions aimed at addressing the various concerns identified by the Mukuru community. According to the Nairobi City County (Citation2020b) several interventions have been identified in dealing with the existing health and sanitation-related challenges in Mukuru. Some of these proposals include upgrading of healthcare facilities and connecting them to the utility networks established in the settlements. Through the SPA, the NCCG can now devise mechanisms to enable it deliver on its public health and sanitation obligations, which are conferred on it by the Constitution and the attendant legislation that are discussed here.

With regards to the proposals outlined by the water and sanitation and the health consortia, a number of challenges lie in the way and hinder their effective implementation. For instance, it would be difficult to establish sanitation infrastructure on land whose ownership is contested and where the interest of the private titleholders are accorded more protections than those of the individuals in actual occupation of the land. With these challenges, we are now presented with a compelling case to decisively tackle the land tenure concerns that would foreclose the implementation of the proposals outlined by the various consortia. The “everyday emergency” of public health and the realities presented by the COVID-19 pandemic provides impetus for the elimination of any factors that would accelerate adverse health outcomes. But before we discuss some of the possible interventions, we offer a brief prelude to the land tenure situation and the state of public health within the Mukuru SPA.

Land tenure contestations as foundation to the attendant challenges in service provision

An analysis of the urban conditions in many African cities reveals the ubiquity of land tenure and its role in amplifying inequalities. Rakodi (Citation1997) suggests that rapid growth in African cities has increased pressure on land and altered land markets making land inaccessible for the poor urban majority. For Bromley (Citation2004) and Roy (Citation2018), the dominant views on property which valorize private ownership tend to reproduce a binary in which one group is privileged over the other. The inegalitarian property arrangements have thus created a two-tiered citizenship that for Pieterse (Citation2008) is denoted by differential access to resources and opportunities in the city with the poor falling within the lower strata where access to public goods is often not guaranteed. Ultimately, rapid population growths interact with unfavorable property arrangements to produce unequitable spatial outcomes. This spatial divide is fertile ground for the emergence of informal settlements, which manifest in different forms from place to place and are often excluded from the imagination of the city during spatial planning processes and in provision of basic services. For Porter (Citation2014), such a divide signifies the existence of contestations between the different configurations of property rights in the city and illustrates how interests in land will often be layered and competing. This prominent role that land plays in influencing the distribution of basic services is also evident in Nairobi and particularly in its informal settlements.

In Mukuru, the land occupied by the informal settlements belongs to a category identified as public land. This land was in the 1980s and 1990s divided into a number of plots and allocated to certain grantees/lessees as 99-year conditional leaseholds under the now-repealed Registration of Titles Act (Cap. 281). Most of the grants were made to private individuals or corporations for business purposes, and in most cases, the land was specifically allocated for the development of light industries. A few grants were made to nonprofit corporations for the development of public facilities. Without exception, all these leaseholds had special conditions contained in the grant. All the grantees were required to comply with the special conditions outlined under the leases, which included a condition requiring that the grantees, within 24 months of the actual registration of the grant, complete the erection of buildings and construction of drainage systems in conformity with the plans, drawings, elevations, and specifications presented for approval. Where a grantee was unable to meet the conditions, the Commissioner of Lands would then (at the grantee’s expense) accept a surrender of the land. However, a majority of the grantees failed to meet these special conditions and failed to develop the lands. While some of the grants were issued over land that was already occupied, a majority were eventually occupied when the grantees failed to develop them as required.

With the constant population increases in the city, demand for land becomes more pronounced and more individuals are pushed into informal settlements, which are mostly located in undeveloped land. Absentee landlords are said to account for 95% of structure ownership within the informal settlements with rent paying tenants accounting for 92% of all inhabitants (Gulyani et al., Citation2006). With these challenges, Weru et al. (Citation2015) argue that the inhabitants of the informal settlements are forced to devise mechanisms that enable them to have access to land and establish the basic services, which they have not been provided by the relevant government agencies. However, a majority of the inhabitants disproportionately incur a “poverty penalty” as they have to access basic services at higher prices compared to those in other parts of the city (Mutinda & Otieno, Citation2016). Tenure insecurity thus presents unique development challenges in the SPA and is a hindrance to the realization of most of the SPA proposals including the provision of better sanitation services and realization of better health outcomes for the inhabitants.

Sanitation shortfalls in mukuru

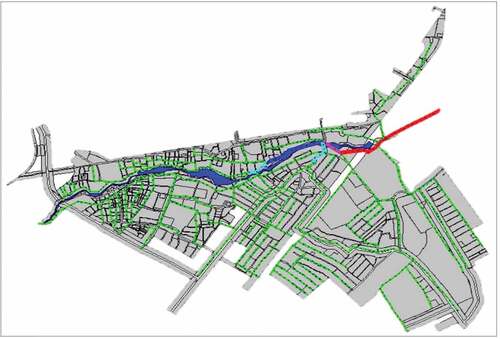

Despite the fact that a large proportion of the city’s poorest citizens live in these settlements, the Nairobi Water and Sewerage Company (NCWSC or “the company”) provides next to no municipal services. With this abdication of duty, garbage in the settlements is not collected and is dumped indiscriminately. Exhaustion services for the pits are not availed and latrines are ordinarily emptied manually with the raw human waste often disposed-off in nearby rivers and drains adjacent to homes and businesses. Water is only provided by the company up to the edge of the settlements with no government-initiated reticulation within the settlements. Consequently, residents have no option but to buy water from water vendors who reticulate it through flimsy unplanned water pipes that are mostly established without approval. This complex and chaotic system of pipes is popularly known as “spaghetti connections.” All of these tangled “spaghetti connections,” are unlicensed. They are often set up by water cartels who hook up to the municipal supply and take water to neighborhood taps and water tanks where people pay exorbitantly between KES.5–10 (US$1 = 103KES) for a 20-liter jerry can. As shown in , this makeshift water infrastructure is often laid over ground and is prone to breakage. The noxious black water that overflows from pit latrines and drains leaks into these pipes and is eventually used in households for cooking and drinking.

Poor sanitation and the lack of sewage systems in Mukuru have critical economic and health costs for residents. Some of the economic consequences include cyclic poverty due to high costs of treatment, losses in wages from missed work, and costs to repair property damage or having to rebuild or relocate their home altogether after flooding. Furthermore, Taffa & Chepngeno (Citation2005) have established that the inhabitants of informal settlements tend to pay more than their counterparts in other parts of the city to access sanitation, which is also inadequately provided. In Mukuru, exposed sewage and human waste, severe flooding, and high cost of sanitation and food contribute to unsafe food handling, food and water contamination, meal-skipping, and under nutrition (Nairobi City County, Citation2020a).

With the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the sordid underbelly of the unequal distribution of health resources and other social amenities has been exposed as governments scramble to assemble mostly reactionary measures to contain the spread. According to Senghore et al. (Citation2020) blanket restrictions and other preventative measures have been adopted without taking consideration of the uniqueness in various contexts particularly in urban informal settlements. However, the existing inequalities in the cities have elevated the vulnerabilities of the marginalized and indigent groups who lack access to running water and other sanitation amenities (UNAIDS, Citation2020). In Kenya, the government has belatedly acknowledged this reality and has tasked The National Treasury with allocating funds for the drilling of boreholes and installation of elevated tanks illustrated by () in informal settlements as a precautionary measure to deal with the pandemic. These interventions follow the proposals that have been outlined by the SPA particularly on how to establish sanitation works in the settlements.

Evidently, the pandemic has now brought to focus competing individual rights, which may impede certain collective interests (Meier et al., Citation2020). The Kenyan government has now come to face with the unyielding duty to provide interventions to safeguard public health notwithstanding the land proprietorship interests that may be upset by its intervention. It has already been demonstrated through its ongoing programs that public health emergencies will indeed call for novel measures to safeguard the collective interests of the population. Moreover, the palpable insufficiencies of the traditional coping mechanisms within the informal settlements now provide an incentive for the adoption of radical measures that will dismantle barriers to achieving the desired public health outcomes.

The state of public health in mukuru

Mukuru is home to about 300,000 people served by over 200 informal schools, countless informal businesses, only two fully functioning health clinics, and other numerous informal social services. As the area is unplanned, structures are often built haphazardly with insufficient access to roads or pathways, thus rendering it impossible to provide water, sewer, drainage, and waste disposal services. Its topographic profile, along with poor drainage and the lack of sewage infrastructure, makes this settlement a sink for many of the watersheds throughout the region with frequent instances of extreme flooding. Over 20% of households are vulnerable to flooding and displacement. There are also over 300 community toilets within the 30-m riparian flood zone, making residents further vulnerable to contaminated flood waters. This results in an overflow of filthy, highly contaminated, disease ridden, black water onto all the roads and walkways within the settlements as illustrated by ()

Exposure to these contaminants has contributed to extremely high rates of childhood diarrhea, stunting, and parasitic infections (UC Berkeley, University of Nairobi, and Muungano wa Wanavijiji, Citation2017). Regular flooding and threat of displacement also contribute to anxiety, fear, and stress among adult residents, and long-term stress is a known risk factor for chronic and infectious diseases. Additionally, there are over 1,150 industrial sites within a 2000-meter radius of Mukuru. Many of these unregulated industries emit toxic chemicals, including benzene and formaldehyde, and elevated levels of arsenic, cadmium, and zinc, which were found in soil samples near dump sites and e-waste recycling facilities in Mukuru (UC Berkeley, University of Nairobi, and Muungano wa Wanavijiji, Citation2017).

Most of the housing units have a shared pit latrine and bathroom, with many others lacking toilet or bathroom facilities. Families that have no toilet or bathroom facilities are often forced to use public toilets like the one shown in () that charge an average sum of KES.5 for adults and KES.3 (US$1 = 103KES) for children for every use. The majority of toilet facilities are not connected to a sewer line and rely instead on pits that must be emptied manually or that flow into open street drainage adjacent to structures and roads.

Figure 5. An elevated water tank at a borehole drilled with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Source: Authors).

The inordinate expense incurred by households that use these public facilities, pushes many to use tins and paper bags popularly known as “flying toilets.” Women and children are especially affected by the lack of adequate sanitation. They often experience rape and sexual harassment when they dare to venture out of their homes and plots in order to use public toilet facilities that are situated away from their homes. According to Subbaraman et al. (Citation2014) mental health is a likely casualty within these contexts of chronic deprivations and social exclusions. A range of problems related to poor sanitation also face the over 200 schools in Mukuru. The most significant being the lack of sufficient toilet facilities. Most schools in Mukuru have an average of 82 students to one toilet. School toilets are often poorly built, filthy pit latrines and are shared between teachers, boys and girls. As a result of the few toilets, long queues are to be found during toilet breaks that prevent many girls from changing their sanitary towels.

Challenges in developing equitable, long-term solutions to Nairobi’s public health problem

The Nairobi Water and Sewerage Company Social Connection Policy (NWSCSCP) was developed by the Nairobi City Water and Sewerage Company (Nairobi City Water & Sewerage Company, Citation2011) as a response to the constitutional right of all Kenyans to clean and safe water in adequate quantities. It seeks to develop systems that can break dependence by the poor on exploitative water vendors and cartels. The policy aims to improve water and sanitation services by providing subsidized first-time connections for domestic water and sewer to people living in informal settlements and low-income areas. It establishes a social connection fund, which is intended to subsidize first-time connections by providing beneficiaries with credit facilities through an appointed financial institution. The guidelines for eligibility in the policy, appreciate that the poor within the city are concentrated in informal settlements and that it is economically efficient to provide subsidies targeted at all the residents in informal settlements. Under the policy, the NCWSC is mandated with procuring and overseeing the installation of materials up to its customers premises (Nairobi City Water & Sewerage Company, Citation2011). It is the responsibility of the customer to provide their internal plumbing.

Despite its advancement of such policies targeting the poor, the water company is often reluctant to provide water and sewer services to the residents of Mukuru. In its Strategic Guidelines for Improving Water and Sanitation Services in Nairobi’s Informal Settlements, the company indicates that informal settlements lack the legal standing to be included in the formal planning frameworks of the various state agencies (Nairobi City Water & Sewerage Company, Citation2009). Mudege and Zulu (Citation2011) have suggested that its hesitation to provide this much needed basic service has been based on the numerous court cases brought by title holders against it for providing services to the inhabitants of informal settlements living on leased land. This fear is reflected in the NWSCSCP, which to a large extent, prohibits the allocation of subsidies for the provision of water and sanitation services to informal settlements situated on private land (Nairobi City Water & Sewerage Company, Citation2011). The NWSCSCP specifically provides that The Water Co. will develop a list of all eligible informal settlements, and it, however, notes that:

As a way of avoiding controversy with the owners of private land which has been occupied by squatters, the social connection policy will only focus on informal settlements which are situated on government land or owner-occupied land. (Nairobi City Water & Sewerage Company, Citation2011)

Such prohibitions are perhaps informed by the unwillingness by some donors to fund projects in areas where tenure is contested (Drabble et al., Citation2018). A toolkit prepared for Kenya’s Water Service Providers (The World Bank, Citation2015) and whose publication was supported by the World Bank also advises water service providers to target settlements in which land ownership is allocated by the county government, owner-occupied or government land. Additionally, households located within riparian, rail, oil pipeline power, or any other official way-leave are barred from benefiting from the subsidy. Such provisions effectively foreclose any investments in settlements that are irregularly established on private land. They are especially worrying given that at least 50% of all informal settlements in the city are situated on private lands.

A major consideration when striving to achieve the constitutional promise of access to clean water in adequate quantities, must therefore be how informal settlements situated on private land can access these much-needed services while overcoming the hurdles posed by the land ownership questions. Reconciling the property rights of titleholders against the public health interests of the inhabitants of Mukuru and the entire city, is without doubt a complex and highly contested issue. Indeed, for Gostin and Wiley (Citation2016), the enforcement of any public health powers is often laden with paradoxes, and a balance must be struck between limiting individuals’ rights in the name of the common good. Yet, it is an essential step toward resolving the many problems facing the inhabitants of informal settlements and the city at large. In seeking to resolve these challenges, several questions arise, such as whether the state has the constitutional and legal mandate to enter onto private land, to invest public resources, and rectify the existing situation in informal settlements given the property interests of titleholders. We explore some proposals on how to navigate these complexities below.

Legislative interventions safeguarding public health

Under the Constitution of Kenya, individuals are bestowed with the right to own property for which they shall not be arbitrarily deprived. This right is, however, not absolute and may be restricted in the public interest or for a public purpose. Any deprivation of property rights shall be accompanied by prompt payment in full of just compensation unless the property was unlawfully obtained. The state, in furtherance of its obligation to deliver on the various functions vested in it, is on the other hand, mandated with the regulation of title. The public interests for which the state can regulate private title are more specifically laid out in Article 66 (1) of the Constitution and this includes public health.

Under the Health Act 2017, the state is mandated with devising and implementing measures to promote health and to counter influences having adverse effect on the health of the people. Such measures that are envisioned by the Act include interventions to reduce the burden imposed by communicable and non-communicable diseases and neglected diseases, especially among marginalized and indigent populations. County governments are also required to maintain their counties in clean and sanitary conditions by maintaining standards of environmental health as laid down in applicable laws.

The Public Health Act (Cap 242) also makes provision for securing and maintaining public health by requiring both national and county governments to take all practicable measures to prevent the occurrence of any outbreak or prevalence of any infectious or communicable diseases, such as cholera, smallpox, typhus fever, or plague. The Act in section 116 further vests upon local authorities the duty to take all lawful, necessary, and reasonably practicable measures for maintaining sanitary conditions and to remedy any conditions liable to be injurious or dangerous to health. Further, under section 115, the Act prohibits persons from causing or suffering to exist on any land or premises owned or occupied by him, which he is in charge of any nuisance or other condition liable to be injurious or dangerous to health. This is a duty that is imposed on any person in occupation of, or owning a premise regardless of the legality of such ownership or occupation. Thus, local authorities are under the Act tasked with maintaining cleanliness and preventing nuisances from occurring. This obligation vests in local authorities the duty to take all necessary measures to maintain sanitary conditions and to prevent the recurrence of nuisance.

Under section 119 of the Act, the medical officer of health, if satisfied of the existence of a nuisance, shall serve a notice instructing the author of the nuisance to remove the nuisance or carry out any works (emphasis added) to prevent a recurrence of the said nuisance. The implication of this is that the medical officer can serve a notice to the tenant or the owner of the structure over which the existence of the nuisance is established instructing him to remove the said nuisance. Thus, a structure owner can be instructed under the notice to carry out certain works that will enable the removal of the nuisance complained of. The kind of works envisioned under the Act may entail requiring a structure owner to put up sanitation facilities for the evacuation of waste where the nuisance complained of is sanitation related.

Discussion

The goal of advancing public health objectives is substantively hindered by existing norms governing private property. Within the current property framework, little accommodation is made for public interest that may be derived from allowing access to private property. We can see the powerful influence that the law exerts on public health through the property arrangements that it creates (Gostin et al., Citation2019). Yet, it remains vital that a balance is struck between the various competing interests to ensure that benefits to the public are still maintained notwithstanding the protections accorded to private property. This calls for regulation of private interests to enable realization of public health objectives. Regulating private property importantly acknowledges the nexus between public health and how land is held and used. It also unmasks the existing power inequalities that perpetrate unjust outcomes for the inhabitants of informal settlements. We have already elaborated on the state’s power under the Public Health Act which charges it with the duty to prevent nuisances from occurring. This together with the state’s power to regulate private property can form the basis of any interventions proposed for Mukuru.

The state remains the principal bearer of the public health duties that have been enumerated above. It is expected that the state shall act in the best interest of the people and devote the requisite resources to enable realization of the public health objectives (Gostin & Wiley, Citation2016). Indeed, the state will act as the arbiter between the often competing common good and the narrow private interests. By exercising its “police powers,” Gostin (Citation2011) argues that the state will effectively be discharging its legal obligation to promote the common good and to prevent the noxious exercises of private rights. In exercising its coercive public health powers, the state will be required to adopt the least-intrusive interventions that respect individual rights while at the same time guaranteeing community well-being (Gostin & Wiley, Citation2016).

In Kenya, the Land and Environment Court has already held that public health concerns will override private property rights that an individual may claim over a piece of land. In Martin Waweru Nguru v Godfrey Momanyi Onchanya & 2 others ELC Case No. 968 of 2013 the Claimant sued the Defendants in their capacity as the officials of Mukuru Slum Water and Sanitation Improvement Project claiming that they had encroached on his parcel of land and constructed public toilets. The said land had been issued to the Claimant through a grant in 1990. In arriving at its determination, the Court noted that even though the Claimant was the registered owner of the suit property, the block of ablutions constructed on the property served a large number of people living in the Mukuru informal settlements. It was the court’s view that

Weighing the Plaintiff’s proprietary rights in the Suit Property against the broader public interest served by the ablution block for sanitation purposes and good hygiene for a great number of people living in Mukuru, the court is of the view that granting the orders sought in the plaint is not the most efficacious remedy in light of the public nature to which the suit land is being put.

Here, the court acknowledges that the Claimant has legitimate interests in the suit property while at the same time taking cognizance of the public interest or the common good to be served by the ablution block that had been constructed on the Claimant’s property. Similarly, the High Court in Ibrahim Sangor Osman v Minister of State for Provincial Administration & Internal Security Constitutional Petition No. 2 of 2011 issued an order compelling the state to allow the petitioners who had been evicted from an informal settlement to return to the land and for the state to further construct amenities that would ensure access to reasonable standards of sanitation by the Petitioners. According to Wash United (Citation2014) the duty of the state to provide adequate sanitation to the public will subsist irrespective of land tenure and property rights. This position is restated in the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights General Comment No. 15 on the right to water.

With regards to the Mukuru leases, the state can enter into the respective parcels of land to carry out water and sanitation works without undue interference on the property rights of the grantees, effectively recognizing the inhabitants rights to use the land for sanitation-related purposes. This is a power that is reserved to the state by legislation and also the leases issued to the grantees. As was held in Theresa Constabir v Jeremiah M. Maroro & 3 others Land Case No. 39 of 2013, the special conditions contained in the leases issued under the repealed Government Land Act are an import of the common law doctrine of “police powers” as the government through these conditions regulate the use of the land leased to an individual for a defined period. Similarly, under the grants issued for the land in which Mukuru occupies, a grantee is bound by certain special conditions. For instance, upon being issued with the grant, a grantee was required to allow the Commissioner of Lands to enter into the land and construct sewer lines or roads at such costs that were to be met by the grantee.

It was envisioned that the grantees would connect their parcels to the established utility lines at their own cost to meet the sanitation needs that would arise from the activities that they were permitted to carry out on the land. Failure to do this gave the state such powers to enter into the land and establish the required connections. Such rights like the right to lay water pipes, sewer trunks, telephone lines, etc., were thus rights that were subsisting when the grants were issued, registered, and lasted for the entire lifetime of the grants. So, each of the titles for the various parcels of land in Mukuru was subject to the special conditions as an overriding interest. As most of the grantees and purchasers of the land failed to carry out any developments on the land allocated to them, the state can still exercise its police powers and task its agencies with entering into the land and establishing such connections as may be required. Once the state has established these connections then it can exercise the powers granted by the Public Health Act, to compel the current occupants of the land or structure owners to connect their homes to such infrastructure that has been laid for the purposes of evacuating the waste and household discharges emanating from the various households. However, as Mudege and Zulu (Citation2011) have already cautioned, such kinds of interventions will invariably attract litigation as the holders of the property titles will seek to challenge any perceived interference by the state. This can stall necessary interventions and leave inhabitants of informal settlement in peril.

We can, however, see from the foregoing discussions that private interests in land will be liable to conditions and interests that the public may have over such land. Being a custodian of the public interest, the state is mandated with enforcing its public health obligations notwithstanding the likelihood of this offending any existing property rights (Gostin, Citation2011). So, when faced with the dilemma of existing private property rights standing in the way of public health goals, then the law mandates the state to act in the interest of protecting public health by providing the requisite services that would abate the public health concerns. The precarity of public health conditions in informal settlements coupled with the radical title that the state has over land commands it to invoke its regulatory powers over private property. Failure by the state to exercise this discretion is arguably a violation of its legal duty to provide adequate sanitation (Murthy, Citation2012). Additionally, establishing these connections does not in any way confer legal rights over the land to those in occupation of it. On the contrary Murthy (Citation2012) argues that it recognizes that there is a wider public interest to be met by disentangling water and sanitation provision from the larger question of land tenure.

This is critical for Mukuru where we now have the SPA process that spells out the manner in which the state can proceed in laying down infrastructure that will enable the evacuation of any hazards that may endanger the health of the inhabitants. As illustrated by (), the SPA process has generated designs for the provision of water and sanitation services. These designs have been developed through participatory processes, which view sanitation and public health as public goods. The designs feature a centralized water and sewer system connected to NCWSC’s main trunk, which traverses Mukuru, with ablution blocks being provided at either the household level or for every 10 households (UNAIDS, Citation2020). Importantly, the SPA separates the question of access to basic services from that of land ownership and it recognizes the right of the inhabitants of Mukuru to access adequate sanitation.

Conclusion

With the numerous challenges experienced in informal settlements that have been highlighted herein, there is a renewed impetus for the state to ensure that it fulfills its constitutional and legislative obligations. This would enable the inhabitants of the informal settlements have access to the much-needed water, sanitation, waste collection, and other environmental health services even in the absence of land titles. NCCGs Declaration of Mukuru as a SPA and the subsequent planning initiatives that have been undertaken by the various consortia provide a framework on how the requisite public health infrastructure can be delivered within the bounds of the law. Such participatory, locally rooted strategies can generate the necessary momentum to address current problems and to achieve a more inclusive, vibrant future for Nairobi’s low-income majority. We suggest that the state can exercise its public health powers to deliver both life-supporting infrastructure and land titles in Mukuru. Given the urgency of the current public health situation, the findings here should inform policy and practice not just in Mukuru, but for all informal settlements in Kenya. The Mukuru example provides important lessons for other African cities that have similar property arrangements and which seek to address public health concerns.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Smith Ouma

Smith Ouma is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the African Cities Research Consortium at the University of Manchester.

Jason Corburn

Jason Corburn is in the Department of City and Regional Planning and the School of Health at the University of California, Berkeley. He also directs the Institute of Urban & Regional Planning.

Jane Weru

Jane Weru is the executive director of the Akiba Mashinani Trust (AMT), a nonprofit organization working on developing innovative community-led solutions to housing and land tenure problems for the urban poor in Kenya. AMT is the financing facility of the Kenya Federation of Slum Dwellers (Muungano wa Wanavijiji).

References

- Boakye-Ansah, A. S., Schwartz, K., & Zwarteveen, M. (2019). From rowdy cartels to organized ones? The transfer of power in urban water supply in Kenya. The European Journal of Development Research, 31(5), 1246–1262. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-019-00209-3

- Bromley, N. (2004). Unsettling the city: Urban land and the politics of property. Routledge.

- Corburn, J., & Karanja, I. (2016). Informal settlements and a relational view of health in Nairobi, Kenya: Sanitation, gender and dignity. Health Promotion International, 31(2), 258–269. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dau100

- Drabble, S., Mugo, K., & Renouf, R. (2018). A journey of institutional change: Extending water services to Nairobi’s informal settlements. Water & Sanitation for the Urban Poor.

- Ezeh, A., Oyebode, O., Satterthwaite, D., Chen, Y.-F., Ndugwa, R., Sartori, J., Mberu, B., Melendez-Torres, G. J., Haregu, T., Watson, S. I., Caiaffa, W., Capon, A., & Lilford, R. J. (2017). The history, geography, and sociology of slums and the health problems of people who live in slums. The Lancet, 389(10068), 547–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31650-6

- Fèvre, E., & Tacoli, C. (2020, February 26). Coronavirus threat looms large for low-income cities. iied. https://www.iied.org/coronavirus-threat-looms-large-for-low-income-cities

- Galva, J. E., Atchison, C., & Levey, S. (2005). Public health strategy and the police powers of the state. Public Health Reports, 120(1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549051200S106

- Gostin, L. (2011). Public health theory and practice in the constitutional design. Health Matrix, 11(2), 265–326. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1559&context=healthmatrix

- Gostin, L., Monahan, J. T., & Kaldor, J. (2019). The legal determinants of health: Harnessing the power of law for global health and sustainable development. The Lancet, 393(10183), 1857–1910. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30233-8

- Gostin, L., & Wiley, L. (2016). Public health law: Power, duty, restraint. University of California Press.

- Gulyani, S., Talukdar, D., & Potter, C. (2006). Inside informality: Poverty, jobs, housing and services in Nairobi’s informal settlements [Report No. 36347- KF] The World Bank.

- Horn, P., Mitlin, D., Bennett, J., Chitekwe-Biti, B. & Makau, J. (2018). Towards citywide participatory planning: Emerging community-led practices in three African cities. GDI Working Paper 2017-034. Manchester: The University of Manchester. https://hummedia.manchester.ac.uk/institutes/gdi/publications/workingpapers/GDI/GDI-working-paper-201834-Horn-Mitlin-etal.pdf

- Makau, M. J., Dobson, S., & Samia, E. (2012). The five-city enumeration: The role of participatory enumerations in developing community capacity and partnerships with government in Uganda. Environment & Urbanization, 24(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247812438368

- Mbathi, M. M. (2011). Integrating geo-information tools in informal settlement upgrading processes in Nairobi, Kenya (PhD thesis, Newcastle University).

- Meier, B. M., Evans, D. P., & Phelan, A. (2020). Rights-based approaches to preventing, detecting, and responding to infectious disease outbreaks. Infectious Diseases in the New Millennium: Legal and Ethical Challenges, 82, 217–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39819-4_10

- Mudege, N. N., & Zulu, E. M. (2011). Discourses of illegality and exclusion: When water access matters. Global Public Health, 6(3), 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2010.487494

- Murthy, S. L. (2012). Land security and the challenges of realizing the human right to water and sanitation in the slums of Mumbai, India. Health and Human Rights, 14(2), 61–73. https://www.hhrjournal.org/2013/08/land-security-and-the-challenges-of-realizing-the-human-right-to-water-and-sanitation-in-the-slums-of-mumbai-india/

- Mutinda, M., & Otieno, S. (2016). Unlocking financing for slum redevelopment: The case of mukuru. Harvard Africa Policy Journal, XI, 44–54. https://apj.hkspublications.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/APJ-full-031716.pdf

- Nairobi City County. (2020a). Mukuru health sector plan (special planning area). Nairobi City County Government.

- Nairobi City County. (2020b). Mukuru special planning area project (spa) water, sanitation and energy sector plan. Nairobi City County Government.

- Nairobi City Water & Sewerage Company. (2009). Strategic guidelines for improving water and sanitation services in Nairobi's informal settlements. Nairobi City Water and Sewerage Company.

- Nairobi City Water & Sewerage Company. (2011). Social connection policy for Nairobi's informal settlements. Nairobi City Water and Sewerage Company.

- Omulo, C. (2019, April 10). 7,900 clinics operating illegally in Nairobi, committee reports. The Daily Nation.

- Pieterse, E. (2008) City future: Confronting the crisis of urban development. UCT Press.

- Porter, L. (2014). Possessory politics and the conceit of procedure: Exposing the cost of rights under conditions of dispossession. Planning Theory, 13(4), 387–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095214524569

- Rakodi, C. (1997). Residential property markets in African cities. In C. Rakodi (Ed.), The urban challenge in Africa: Growth and management of its large cities (pp. 371–410). United Nations University.

- Roy, A. (2018). The potency of state: Logics of informality and subalternity. The Journal of Development Studies, 54(12), 2243–2246. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2018.1460470

- Senghore, M., Savi, M. K., Gnangnon, B., Hanage, W. P., & Okeke, I. N. (2020). Leveraging Africa’s preparedness towards the next phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 8(7), E884–E885. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30234-5

- Smith, L. G. (1984). Public participation in policy making: The state-of the-art in Canada. Geoforum, 15(2), 253–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7185(84)90036-8

- Subbaraman, R., Nolan, L., Shitole, T., Sawant, K., Shitole, S., Sood, K., Nanarkar, M., Ghannam, J., Betancourt, T. S., Bloom, D. E., & Patil-Deshmukh, A. (2014). The psychological toll of slum living in Mumbai, India: A mixed methods study. Social Science & Medicine, 119(1982), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.021

- Taffa, N., & Chepngeno, G. (2005). Determinants of health care seeking for childhood illnesses in Nairobi slums. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 10(3), 240–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01381.x

- UC Berkeley, University of Nairobi, and Muungano wa Wanavijiji. (2017). Mukuru: 2017 situational analysis. Squarespace. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58d4504db8a79b27eb388c91/t/5a65fbd653450a34f4104e69/1516633087045/Mukuru+SPA+Situational+Analysis+2017+Phase+2.pdf

- UNAIDS. (2020, March 20). Rights in the time of COVID-19: Lessons from HIV for an effective, community-led response. UNAIDS. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/human-rights-and-covid-19_en.pdf

- UN-Habitat. (2014). The state of African cities 2014: Re-imagining sustainable urban transitions. UN–Habitat.

- UN-Habitat. (2020, March 20). COVID and Informal Settlements. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/03/english_final_un-habitat_key_messages-covid19-informal_settlements.pdf

- Wash United. (2014). The human rights to water and sanitation in courts worldwide- A selection of national, regional and international case law. WaterLex and WASH United.

- Weru, J., Wanyoike, W., & Di Giovanni, A. (2015). Confronting complexity using action-research to build voice, accountability and justice in Nairobi’s Mukuru informal settlements. The World Bank Legal Review, 6, 233–255. https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/handle/10625/55278

- Winter, S. C., Dreibelbis, R., & Dzombo, M. N. (2019). Mixed-methods study of women’s sanitation utilization in informal settlements in Kenya. PLoS One, 14(3), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214114

- The World Bank. (2015). Water service provider toolkit for commercial financing of the water and sanitation sector in Kenya. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank.