ABSTRACT

The role of urban cemeteries is highly context-dependent and varies greatly across cities and countries. Despite the growing body of literature on the cemeteries’ potential for urban development, Eastern Europe, and in particular Russia, remains underrepresented. Seeking to fill this empirical gap, this paper brings forward the case of cemeteries in Moscow, the capital of Russia. Using the concept of public space as a theoretical lens, I aim to explore the extent to which cemeteries are envisioned as public spaces in planning policies and development practices in Moscow. The study builds on a critical qualitative analysis of relevant policy documents and semi-structured interviews with experts, supplemented by field observations. The empirical material is analyzed through the prism of four dimensions: liminal, spiritual, commercial and multifunctional. The findings show that planning policies and development practices view cemeteries primarily in terms of disposal provision. Regarded as an “unspectacular” part of the urban environment, cemeteries are excluded from the authoritarian programs of improvement of public spaces in the city. However, Moscow cemeteries have a range of qualities which make them valuable—although invisible at the policy level—public spaces with a multifaceted role.

Introduction

While the primary function of cemeteries as burial spaces and places for memorialization (Bachelor, Citation2004) is almost universal, the way in which their role is embedded in spatial planning and governance varies in different contexts. National and cultural differences shape how societies deal with death and bereavement (Walter, Citation2020) and, consequently, plan and facilitate the use of cemeteries (Nordh et al., Citation2021; Rae, Citation2021). Moreover, the attitude and vision of policymakers may vary from country to country when it comes to incorporating cemeteries into the overall urban development. For example, the complex role of cemeteries is becoming increasingly acknowledged in large Scandinavian cities (Nordh & Evensen, Citation2018), whereas the evidence from some other regions, like Britain, is not always so bright (McClymont, Citation2014). In some cases cemetery planning fails to provide even the primary function of interment and memorialization (Blagojević, Citation2013; Rusu, Citation2020). Despite the growing body of research on the cemeteries’ potential for urban development (McClymont, Citation2016; Quinton & Duinker, Citation2019; Skår et al., Citation2018), Eastern Europe, and in particular Russia, remains underrepresented. This paper seeks to fill this empirical gap and brings forward the case of cemeteries in Moscow, the capital of Russia. Although there exist general studies of the Russian funeral industry (Moiseeva, Citation2013; Mokhov, Citation2021; Mokhov & Sokolova, Citation2020), as far as I am aware, this article is the first English-language paper which focuses on the spatial aspects of cemetery planning and development within a Russian context.

Despite the proclaimed “end of public space” (Mitchell, Citation2017), public space continues to be a priority of urban development worldwide (Mehaffy et al., Citation2019) and manifests in a variety of types designed for and used by different audiences (Carmona, Citation2015). In the case of urban cemeteries, Klaufus (Citation2018) demonstrates that a lack of recognition of their public space aspects among planners can be problematic. Formally, Moscow cemeteries fulfill two basic criteria of public space (Zukin, Citation1995): being accessible to everyone and being managed by public authorities. In this article I aim to explore the extent to which cemeteries are envisioned as public spaces in the planning policies and development practices in Moscow.

With a population of 12.7 million people and an area of 2,600 km2 (Federal State Statistics Service, Citation2020), Moscow is the largest city in Europe and a showcase for the Russian version of authoritarian urbanism (Zupan et al., Citation2021) and post-socialist neoliberal urban development (Golubchikov et al., Citation2014). For a discussion of the multifaceted role of urban cemeteries, Moscow is an insightful case due to three current trends: first, increased densification through a so-called housing renovation program (Khmelnitskaya & Ihalainen, Citation2021); second, the government’s recent ambitious efforts to improve public spaces (Kalyukin et al., Citation2015; Trubina, Citation2020), including green spaces (Blinnikov & Volkova, Citation2020; Zupan & Büdenbender, Citation2019); third, the emphasis on memorialization in the Russian state cultural ideology (Turoma & Mjør, Citation2020). As described below, Moscow cemeteries are publicly accessible green spaces and memorial sites, often situated close to or within residential areas undergoing densification (see ). These trends might have an impact on the role of cemeteries and how it is articulated at the policy level.

Figure 1. New large-scale housing complex built in 2016–2021 just outside of Vvedenskoe cemetery in Moscow, May 2021. Photo by Pavel Grabalov.

The structure of the paper is as follows. The first part of the research presents some contextual information about Moscow cemeteries’ historical and contemporary development. The second part outlines the conceptual and methodological approaches used in the research. The third part is intended to demonstrate how the analytical dimensions of cemeteries as public spaces manifest in the empirical material from Moscow. Finally, the paper concludes with critical reflections on the policy gaps surrounding Moscow cemeteries and cemeteries’ potential for the urban planning and development of the Russian capital.

Moscow cemeteries: Setting the scene

Contrary to many Western European and North American countries, where there was a clear distinction between religious churchyards and secular cemeteries (Laqueur, Citation2015), the history of the modern Russian cemetery (кладбище [kladbishche] in Russian, meaning any type of a burial space) has a different trajectory. Starting from the 18th century, modern Russian cemeteries had never been completely detached from the religious authorities until the beginning of the 20th century, when drastic changes to their governance were brought about (Dushkina, Citation1995; Mokhov, Citation2021; Shokarev, Citation2020). To contextualize the discussion of Moscow cemeteries as public spaces, it is worth pointing out some aspects of their historical and contemporary development with a focus on their differences from the cemeteries in Western Europe and North America, which are better described in the literature, and with regards to public space aspects.

History

In 1771, as a response to a plague epidemic, there were nine new cemeteries established in the fields just outside Moscow, aiming to replace the existing inner-city burial spaces next to the city’s parish churches and monasteries (Shokarev, Citation2020). From the beginning of the 19th century, these new cemeteries, except the cemeteries for religious minorities, were managed by the Russian Orthodox Church in collaboration with the city government; private and secular cemeteries did not exist. Contrary to the grand projects of garden cemeteries carried out during the same time in Western Europe and North America (Laqueur, Citation2015), Moscow cemeteries’ landscape organization and management were neglected. In the 19th century, the efforts to physically upgrade the cemeteries were mainly focused on building churches and constructing fences around the cemeteries (Pirogov, Citation1996). As a result of bad or absent planning, at the beginning of the 20th century, Moscow’s cemeteries were crowded (Sokolova, Citation2018) and looked like a labyrinth of old graves and informal greenery (Dushkina, Citation1995). At the same time, cemeteries were also recognized as heritage sites, offering attractive places for strolling and environments with a special atmosphere (Saladin, Citation1997).

The potential of cemeteries as public spaces was widely discussed in the first decades of Soviet Russia, after the 1917 revolution, when all cemeteries were municipalized, becoming the responsibility of city councils, which regarded them as both a burdensome duty and a source of resources and land (Sokolova, Citation2019). Many monastery burial spaces and several city cemeteries were then torn down and transformed into parks or residential and industrial areas. This demolition, still a sensitive topic for local heritage activists, is usually portrayed as part of a brutal anti-religious campaign (Malysheva, Citation2020; Shokarev, Citation2020). However, according to a recent archival study by Sokolova (Citation2018), “in most cases, behind the demolition of the cemeteries was not an atheistic propaganda but rather pragmatism of improving rapidly growing cities” (p. 94, my translation). Unfortunately, as Sokolova (Citation2018) points out, most of those projects destroyed the cemetery infrastructure, failing to build high-quality public spaces in their place.

The second half of the 20th century was characterized by two parallel tendencies. On the one hand, the city focused on the construction of new vast and simplistic-looking suburban cemeteries (Karavaeva, Citation2007; Merridale, Citation2003). On the other hand, due to a lack of services provided by the authorities, citizens had to organize funerals and graves within their own social networks, something that Mokhov and Sokolova (Citation2020) call “DIY-funerals.” Malysheva (Citation2018) notes that the funeral industry, including cemeteries, was the least controlled and financed area of Soviet ideology; therefore, citizens could express themselves there more freely than in other public spaces. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Russian funeral industry received many problems, amplified by the state’s withdrawal from public sectors, neoliberalization and an increase in criminal activities. In the 1990s, Moscow cemeteries suffered from vandalism (Dushkina, Citation1995) and were associated with mafia activities (Mokhov, Citation2021).

Contemporary cemetery provision

Cemetery provision is a responsibility of local authorities in Russia, and in Moscow, all cemeteries are taken care of by an agency called Ritual (ГБУ “Ритуал”), which is owned by the city government and managed by its Department of Trade and Services (Департамент торговли и услуг). The agency is in charge for 136 cemeteries. Apart from running cemeteries, the agency offers all types of commercial funeral services competing with private companies. Mokhov and Sokolova (Citation2020) argue that the contemporary Russian funeral industry is fundamentally “broken” and functions as an informal network of actors controlling the funeral infrastructure, including the cemeteries. Moscow’s funeral business fits this picture, as demonstrated in a recent anti-corruption exposé (Golunov, Citation2019).

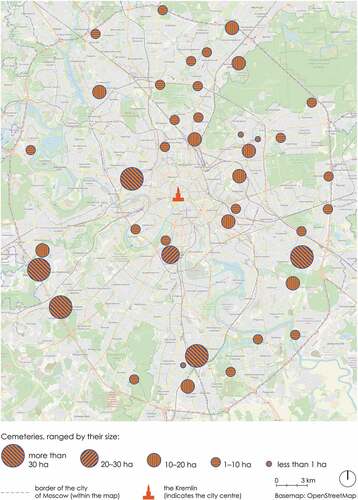

The cemeteries owned and managed by the Moscow government are situated both in Moscow and in the Moscow region—a separate administrative unit which surrounds the Russian capital—including the only three cemeteries that are “open” for Muscovites. These cemeteries have available land for new graves provided to citizens free of charge, as guaranteed in the Federal (Russian Federation, Citation1996) and City (Moscow government, Citation1997b) Funeral Laws. All other Moscow cemeteries are “closed” for new graves except for interments into relatives’ graves or special “family (ancestral) graves.” In reality, the difference between the “open” and “closed” cemeteries is blurred, with the “open” cemeteries catering for only 21% of the city’s 48,000 burials in the ground per year (Kuznetsova & Levinskaya, Citation2020). Moscow cemeteries vary in terms of their size, location, history, level of maintenance and landscape organization. This paper focuses on the cemeteries situated within the Moscow Ring Road (see ) as their range of functions is likely to be larger than at the cemeteries located in the fields outside the city.

Figure 2. Cemeteries within the Moscow Ring Road (МКАД), which demarcates the morphological city of Moscow. The cemeteries’ location and size are taken from the official websiteFootnote1 of Ritual.

Moscow cemeteries occupy 2,000 ha (Kuznetsova & Levinskaya, Citation2020) and have a permanent shortage of land for new graves due to the disposal and grave management system practiced in Moscow, which forces the authorities to open new cemeteries on a regular basis. Disposals include coffin burials and urn interments in the ground or columbaria; 50% of the disposals in the city are cremated remains (Kuznetsova & Levinskaya, Citation2020). Without explicit provision in the legislation, graves in the Moscow cemeteries are provided in perpetuity; the system of grave re-use is practiced mainly for relative’s graves. Because of a large share of coffin burials, which require more space compared to interment of cremated remains, and the de facto perpetual status of the graves, cemeteries quickly become saturated.

Conceptual and methodological approaches

Conceptually, this paper uses the notion of public space as a lens to explore how the role of Moscow cemeteries is articulated in the city’s planning policies. The paper is inspired by interpretative critical policy studies, which challenge a positivist approach to the analysis of policies as examination of inputs and outcomes, and instead focuses on the context, values and normative assumptions that are shaping policy processes (Fischer et al., Citation2015). In its normative understanding, the concept of public space is closely connected to social justice (Low, Citation2020), which is considered by Fainstein (Citation2015) the principal goal of urban policy. Cemeteries can contribute to socially just cities by fulfilling the right to a decent disposal with respect to people’s religious freedom and environmental sustainability (Rugg, Citation2022) and by providing access to diverse high-quality outdoor environments for recreational activities (Skår et al., Citation2018) and social encounters (Swensen & Skår, Citation2019).

This paper builds on a qualitative analysis of documents and semi-structured interviews with experts, complemented by field observations conducted at nine cemeteries in Moscow. The policy documents included various sources, such as cemetery and funeral industry-specific laws and regulations (both on the federal and city levels), general spatial plans of Moscow, programs and strategies, reports and standards, public opinion polls, mass media coverage and design manuals. Twenty-three experts took part in semi-structured interviews (in Russian) between August 2020 and June 2021, providing insights for four fields: cemetery and funeral industry, planning and architecture, environmental management, and cultural heritage and conservation (for more details of the methods see Grabalov, Citation2022).

Analyzing the documents and interviews, I followed the lead of Woodthorpe (Citation2011), who suggests seeing a cemetery as a simultaneous coexistence of different meanings, or landscapes (analyzing London cemeteries, she identifies landscapes of emotion, commerce and community). This paper uses the analytical framework developed recently for the study of Scandinavian cemeteries as public spaces, as outlined in Grabalov and Nordh (Citation2022), and refined for the empirical material from Moscow. This paper focuses on four dimensions: liminal, spiritual, commercial and multifunctional.

As liminal spaces, cemeteries function as border crossings between the world of the living and the dead, present and past, physical landscape and emotion (Francis et al., Citation2005). Moscow cemeteries’ liminality can be captured by highlighting the tension between the meanings associated with them and the meanings revealed in their planning documents. Spirituality and religion are inherent aspects of cemeteries (Jedan et al., Citation2020) that distinguish them from other types of public and green spaces (Grabalov & Nordh, Citation2020). The second dimension of the analytical framework—spiritual—is especially relevant for theoretical debates on a postsecular city, emphasizing the diversity of the contemporary relations between the spiritual and the secular (Beaumont & Baker, Citation2011). To articulate spiritual aspects of cemeteries and other urban spaces in planning, McClymont (Citation2015) developed an idea of municipal spirituality, which is an “inclusive language of public sacredness” that describes “a place which allows access to the transcendental and promotes the common good” (pp. 542–543).

The commercial dimension of the framework covers stakeholders’ efforts to profit from cemeteries. This dimension is closely linked to the debates around privatization of public space (Staeheli & Mitchell, Citation2008) and how neoliberal development shapes the public space of post-socialist cities (Kalyukin et al., Citation2015). Multifunctionality, the fourth framework’s dimension, is considered an essential ingredient of a genuine public space (Hajer & Reijndorp, Citation2001). Although cemeteries are designed for a particular function (interment and memorialization), they can also accommodate other functions, such as recreation, reflection or socialization (Evensen et al., Citation2017; Rae, Citation2021; Skår et al., Citation2018). A combination of these secondary functions varies across contexts, and the multifunctionality of cemeteries can have different relevance for the citizens.

Moscow cemeteries through the prism of four dimensions

The analysis of the empirical material revealed a set of common themes which demonstrated how each dimension of the analytical framework manifested in the case of Moscow cemeteries. These themes (see ) were discovered through an iterative process of analysis and aim to show how public space aspects of Moscow cemeteries are envisioned in planning policies and by experts. This section describes each theme and illustrates them with field observations and extracts from the documents and interviews (translated from Russian into English).

Table 1. Analysis result: Manifestation of the four dimensions of Moscow cemeteries as public spaces.

Liminal space

The analysis of the empirical material from Moscow shows that the liminal dimension manifests as three themes: physical separation of cemeteries from their surroundings; ambiguous positions in planning documents; the tension between general publicness and privateness of the graves.

The first theme highlights the physical liminality of Moscow cemeteries and their tangible exclusion from the surroundings. A significant part of the cemetery legislation on both federal and city levels is devoted to the sanitary and hygienic requirements for cemeteries. Public health concerns, which were important for the establishment of suburban cemeteries in many Western European cities in the 19th century (Laqueur, Citation2015), still guide cemeteries’ planning and management in Russia. While already in the end of the 19th century, Friedrich ErismannFootnote2 (Citation1887), a doctor and a pioneer of hygiene in Russia, emphasized that “from the point of view of sanitation, we should be more scared of the living than of the dead” (p. 387), the current Russian sanitary legislationFootnote3 (Chief Sanitary Inspector, Citation2011) portrays cemeteries as hazardous places. Prescription to have a sanitary protection (санитарно-защитная зона), or buffer, zone around each cemetery is a good illustration of this. According to federal norms (Chief Sanitary Inspector, Citation2007), the size of the buffer zone depends on the size and status of the cemetery, varying between 500 m for large working cemeteries and 50 m for columbaria and closed cemeteries. However, the zones around older Moscow cemeteries do not fully follow the regulations and sometimes exist only in documents. Nevertheless, as the areas around cemeteries cannot be legally developed, they often end up being used as wasteland with wild vegetation, car storages and depots of construction materials, further isolating cemeteries from the rest of the city.

In general, the purpose of a sanitary protection zone is to decrease the potential harm from objects, mostly industries, for the environment and people’s health. The regulations, however, do not explain what kind of danger cemeteries pose. This danger can include contamination of the ground water, but this is unlikely to be mitigated through allocation of buffer zones; the risk is more relevant for smaller settlements without a safe drinking water system (Karavaeva, Citation2007). Some interviewees were critical of this situation, asserting that it did not reflect the real danger from cemeteries. For example, an interviewed planner said, “A cemetery is a huge stain on the city’s body, causing legally as much harm as a cement factory” (Interviewee O).

According to the Moscow Construction Norms for Funeral Infrastructure (Moscow government, Citation1997a), the zones around cemeteries are meant to protect the “health of the people who participate in funerals, visit graves, work at the funeral-related objects, live and work at the territory around the cemetery or crematorium.” An environmental management expert interviewed for this study noted that the zones around cemeteries were meant to not only prevent pollution but also provide “moral protection,” a term that is also used but not explained in the Federal Funerary and Cemetery Recommendations (Gosstroy, Citation2002). In this sense, sanitary-protection zones are supposed to take care of the emotionally challenging connotations associated with cemeteries.

The second theme that captures the liminal dimension of Moscow cemeteries is their ambiguous position in the planning legislation: different planning documents place them in different categories. For example, the Federal Urban Planning Code (Russian Federation, Citation2004) considers cemeteries, along with crematoria, burial grounds for cattle and landfills, part of a “zone reserved for special use.” According to the Moscow legally binding Land Use Plan (Moscow government, Citation2017), cemeteries are in the same category as landfills and mentioned as part of “industrial territories,” while the city’s Urban Planning Code (Moscow government, Citation2008a) and General Plan (Moscow government, Citation2010) view cemeteries as objects of social infrastructure, similar to the health, education and other services. Several interviewees emphasized a utilitarian stand on cemeteries in Moscow spatial development: cemeteries are intended to fulfill disposal needs, being excluded from all later strategic planning. A planner interviewed for this study explained this attitude as follows: “We [planners] are cynical and utilitarian. It [a cemetery] is a very complex phenomenon. Actually, everything related to the non-material sphere, to the cultural or religious sphere, is a serious problem because it does not fit our material estimation” (Interviewee I).

The third theme sustaining cemeteries’ liminality articulates tensions between the public character of cemeteries and the private and intimate nature of graves. Moscow cemeteries are publicly accessible spaces where visitors can enter freely within opening hours and without necessarily being relatives or friends of the people buried there. At the same time, highly personalized graves, which occupy the largest part of cemeteries, are very private spaces (see ). The relative responsible for a grave has the right to choose how to arrange it and has the property right for the headstones and other constructions at the grave (Moscow government, Citation2008b), whereas the land is owned by the city. The person officially responsible for a grave must maintain the grave in a proper (надлежащий) manner. The cemetery legislation, however, does not clarify what “proper”—a liminal category in itself—means and in general provides a flexible framework for personalizing graves. The Funeral Decree of the Moscow government (Moscow government, Citation2008b) does not define any characteristics of tombs and other constructions but notes that they should fit the “architectural and landscape environment of the cemetery” (p. 46) without explaining what this means in practice.

Fences, which are common at Moscow cemeteries, demonstrate the complexity of individual choices in a cemetery space. In a more general context of abnormal exuberance of fences in Russia (Trudolyubov, Citation2018), fences around individual graves can be seen as a way to protect property rights in a situation when formal legal mechanisms do not function correctly (Mokhov, Citation2021). A planner, interviewed for this study, explained it as follows:

Not from a legal but from a practical point of view, neither in our culture nor everyday life do we have a clear distinction between a public and a private space. … Unless you install a fence, you cannot be sure that people will not crush everything by walking there. (Interviewee J)

At Moscow cemeteries, most graves are fenced in a different style, and there are often fences of two adjoined graves standing side by side, compromising their practical purpose.

The history of cemetery legislation demonstrates ambiguous attitudes to this practice: from prohibiting (Ministry of Housing and Utilities, Citation1979) and discouraging (Chief Sanitary Inspector, Citation1977) in the 1970s, although with little success, to silence in the current documents. However, the cemetery authorities in Moscow do not approve of such “privatization” of graves. In an interview published in an online media (Loriya, Citation2021), the director of the agency Ritual agreed that Moscow cemeteries were not as aesthetically impressive as the European ones and explained that Ritual was in charge of just 15% of the territory, with everything else being the responsibility of individuals. In that interpretation, the rest of the cemetery does not belong to public space. In another interview (Kuznetsova & Levinskaya, Citation2020), Ritual’s director noted that it was impossible to interfere with the “memorial self-expression” and “jumble of fences” at the existing cemeteries. So, instead, Ritual developed standards for new cemeteries: the agency is promoting new fence-free cemeteries in its social media accounts as part of their effort to “educate the population about funeral culture” (gbu_ritualofficial, Citation2021). In that sense, the cemetery authorities oppose the aesthetics of individual fences rather than acknowledge the rationales behind such “privatization.” Feeling insecure about one’s formal rights is one of these rationales; desire to taking care of the graves by individuals is another one.

Spiritual space

The spiritual dimension of Moscow cemeteries is disclosed through four themes: grave visitation and care; “honorable” graves; pilgrimage; the role of religion in cemetery management.

The first theme describes the practice of visiting and maintaining graves, which is an ultimate expression of “proper” Russian cemetery culture (Bouchard, Citation2004). Each grave is an object of care for the relatives and a way to commemorate the deceased. A typical visit to the cemetery includes such activities as conversations with the deceased, “cemetery labor” (cleaning, painting, planting, watering vegetation, etc.), bringing fresh and faux flowers, memorabilia and sometimes sweets and vodka. The city agency Ritual facilitates these practices by providing water, sand and garden tools to borrow and offers a paid grave maintenance service. However, according to the annual public opinion poll (Sinergia, Citation2016) run by the Department of Trade and Services, the majority of the respondents prefer doing it themselves; the authors of the report explained that as follows: “Maintenance of a grave is considered an honorable and in most cases pleasant responsibility, a sacred way to communicate with the deceased” (p. 26). Moreover, taking care of a grave is a very active way to interact with the environment for a change, something that is unimaginable in other, more controlled, public spaces of the city.

The results of the poll (Sinergia, Citation2016) show that 56.4% of the respondents visit cemeteries at least once a year. People come to the graves of their loved ones on the birth or death days of the deceased and during traditional periods of mass visitation (e.g., at Orthodox Easter in spring). While visiting a cemetery on Easter day is not supported by the Russian Orthodox Church, during the Soviet times of oppression of religious practices, cemetery visitation on Easter was the only public religious ritual (Levkievskaya, Citation2006). Moscow authorities facilitate such mass visits (up to 1 million people came to the cemeteries at Easter time in 2019) by providing extra public transport, tools for maintaining graves and portable toilets (Mayor of Moscow, Citation2019). Presence of a large number of people in the usually deserted cemeteries transforms these places and adds a public dimension to their character.

The second theme that reveals the spiritual dimension of Moscow cemeteries is a special attitude toward the so-called “honorable” graves (почётные захоронения) that belong to the citizens with some merits to the state and society; such people can be buried in the old and closed cemeteries (Moscow government, Citation2006). Typically, honorable citizens are veterans, politicians, actors, artists, scientists or journalists. Merits are not specified, and it is the Moscow government that decides to grant plots after an application from trade unions, state agencies or other organizations. The allocation of grave plots is not a transparent process. The Federal Funerary and Cemetery Recommendations (Gosstroy, Citation2002) prescribe “honorable” graves to be situated in the “best” part of the cemetery in terms of their accessibility and view. Usually, such graves are marked with large memorials (Kucheryavaya, Citation2021). The presence and elimination of “honorable” graves at Moscow cemeteries adds another spiritual meaning to these places and highlights their publicness. Such graves not only comprise cemeteries heritage sites but also allow cemeteries to serve as spiritual hotspots where visitors can experience proximity to the life and death of famous people.

The third theme defining the spiritual aspects of Moscow cemeteries is their role as pilgrimage sites and spaces for a range of spiritual practices from quiet, meditative walks to spiritual rituals. During my field trips to Moscow cemeteries I observed a variety of such practices: praying at the graves of saints or praised religious people, writing wishes on the walls of mausoleums or leaving small paper notes on special graves, visiting significant graves of famous people or the graves of special artistic or visual value and strolling around the cemetery to feel particular emotions (e.g., by the people associated with the gothic subculture). Moroz (Citation2021) considers such cemetery practices examples of spontaneous rites or creative bottom-up search of urban dwellers for spiritual traditions. Although this role is completely ignored by cemetery legislation, field observations and media coverage reveal that spiritual values of the city’s cemeteries, especially the old ones, are important for their visitors. In the conducted interviews, acknowledgment of spiritual qualities was also common and considered as something that is not recognized at the policy level. A social infrastructure planner interviewed for this study connected transcendent values of cemeteries with their potential as restorative environments:

Our lifestyle—I think not only in Moscow—is bereft of humanity. … Every day, we need more and more tools for rest, for a deeply emotional, psychological rest. … In this sense, a cemetery is a unique place not only because of its historical potential and culture, but because a cemetery tells us that life is temporal: you can jump around now, pretending to be a boss, but everyone ends up here. This psychotherapeutic nature and role of the cemeteries are unique. And you can arrange it with a very respectable design, physical amenities, opportunities to rest … Of course, it is difficult to realize and may take considerable time, but I think it is a very relevant and necessary task. The idea of integrating cemeteries into human life does not exist at all, no one is talking about it. (Interviewee H)

More than other public spaces, cemeteries are influenced in their use and management by traditions and stereotypes, which often have a religious background. The role of religion and beliefs in cemetery management is the fourth theme illuminating the spiritual dimension of Moscow cemeteries. The city inherited a secular, or even an atheist, orientation of cemeteries from the Soviet times, but religion (predominantly, Russian Orthodox) is now visible there again: chapels and churches are being restored or constructed and religious symbols are common grave decorations. Talking about the extent to which religion influences decisions in cemetery governance and planning, it can be noted that there are confessional cemeteries (Armenian Orthodox, Jewish and Muslim) within the city-governed Moscow cemetery system, and the laws and regulations prescribe reappearance of special confessional sections and cemeteries. In the past few decades, there have been attempts to strengthen the role of religious organizations in the funeral industry: a draft of a new Federal Funeral Law (Gosudarstvennaya Duma, Citation2020) suggested a more active role of religious organizations in managing and even owning confessional burial spaces. An article in the official journal of the Russian Orthodox Church, which participated in drafting the law, highlighted the importance of confessional cemeteries for increasing spirituality in society (Erofeev, Citation2012). The revision of the Federal Funeral Law has been discussed since 2012 (Mokhov, Citation2021) but has not been adopted yet, so religious organizations still have very limited formal participation in cemetery governance in Moscow.

Commercial space

The Federal Funeral Law (Russian Federation, Citation1996) has a clear welfare orientation, stipulating that grave plots should be provided by the local authorities free of charge and respecting the wish of the deceased. Therefore, cemeteries are supposed to function to benefit all citizens equally, regardless of their income status. In reality, Moscow cemeteries are far from this because both formal and informal stakeholders try to use cemeteries to gain commercial profit (Golunov, Citation2019; Mokhov, Citation2021; Mokhov & Sokolova, Citation2020). There are two themes which describe Moscow cemeteries as a commercial space: debates around the idea of private cemeteries and the practice of selling grave plots at the existing cemeteries.

One of the most prominent ideas which is believed to be able to solve the problems of the Russian funeral industry is the liberalization of the market. Recent discussions about introducing private cemeteries based on the revision of the Federal Funeral Law provide rich insights into this idea. The initial draft of the document was written by the Federal Antitrust Agency (Федеральная антимонопольная служба) that saw the main cause of the industry’s problems in the monopolization of funeral markets by the local authorities. The Ministry of Construction, Housing and Utilities (Министерство строительства и жилищно-коммунального хозяйства) supported the idea of private cemeteries to increase the quality of funeral services and promote investment in the industry (Ministry of Construction, Citationn.d.). The scale of the discussion about private cemeteries, as well as positive attitude to them, is impressive among practitioners (based on the content of the conferences by the Union of Funeral Organizations and Crematoriums, Citation2021). According to the conducted interviews, the idea of private cemeteries was generally accepted well: a representative of an urban design consulting company considered commercial companies a potential driver of positive changes; an interviewee from a private funeral agency suggested that the need to have a competitive advantage might lead to improved landscape design of private cemeteries. However, the drafts of the revised Funeral Law did not include a mechanism to safeguard the future of private cemeteries, which are dependent on the availability of plots and the financial resources of the owner.

Although Moscow cemeteries are owned and managed by public authorities and are supposed to be used only for common good, they are used to gain profit. Apart from corruption (Golunov, Citation2019), there is an official way to do it, which is selling grave plots at the existing Moscow cemeteries officially closed for new interments. This is the second theme that is relevant for the commercial dimension of Moscow cemeteries and demonstrates cemeteries’ subtle privatization. Ritual, which provides this service, does not call it a “sale” (sales of grave plots is not allowed by the funeral legislation), but operates with the “distribution of rights for family (ancestral) graves (семейные (родовые) захоронения).” So, the city government does not sell plots; rather, according to the regulations (Moscow government, Citation2015), the land is provided for free, and the person buys only the right to dispose of their dead family members. In practice, however, this right is explicitly connected to a particular grave plot, and the price depends on the rank of the cemetery and the plot’s location and size.

Although a transparent system of plot selling could fight the corruption associated with the distribution of plots, it would pose challenges for the cemeteries’ role as an inclusive and accommodating public space. The price of a “family (ancestral) grave” at the central Moscow cemeteries can reach up to 6 million rubles (Loriya, Citation2021), or roughly €72,000, which makes these places available for the interment of either rich Muscovites or people whose relatives are buried there. Another negative aspect is how cemetery authorities “find” new plots at the existing cemeteries: without a grave re-use system, it means that the open space of these already full cemeteries is shrinking further. The photographs of available plots in the online register on the websiteFootnote4 of the Moscow government confirm it: most plots are organized between the existing graves or between the existing graves and the fences or paths. It can be argued that this profit is channelized within the Moscow cemetery authorities and is supposed to be used for public purposes; however, the system of “family (ancestral) graves” creates fundamental injustice both for the dead, who cannot be buried where they want to unless they have much money, and the living, who have less physically accessible space.

Multifunctional space

Even though Moscow planning documents mostly consider the primary function of cemeteries as burial grounds, the role of the city’s cemeteries is multifaceted. Some of the cemeteries’ secondary functions can be found in the sectorial planning legislation (e.g., in terms of heritage or green infrastructures), whereas other functions, such as recreation, can be seen only in the observations of visitors’ behavior. In the analysis of the empirical material from Moscow, cemeteries are explored as multifunctional spaces through three themes: cemeteries as heritage sites; contribution to green infrastructure; the actual use, relevant management and design solutions.

Despite the dramatic loss during the first half of the 20th century, Moscow cemeteries, some of which are over 200 years old, contain a significant number of the traces of the past and function as heritage sites, constituting the first theme of the multifunctional dimension. The responsibility for the heritage of Moscow cemeteries lies with the city’s Department of Cultural Heritage (Департамент культурного наследия). About 1,500 graves (Interviewee T) are recognized as heritage objects and being taken care of by the city. There are two types of cemetery cultural heritage objects: the graves of outstanding people or the tombs of artistic value.

There are 29 burial spaces in Moscow registered as cultural heritage sites as whole entities according to the Moscow government Open Data website.Footnote5 Most of these cemeteries are working and open, at least, for the interments into the relatives’ graves. The heritage aspects attract visitors to the cemeteries, with numerous excursions held at old cemeteries and organized by the city history and heritage groups, private guides and Ritual itself. Therefore, Moscow cemeteries function as outdoor museums and public collections of the city’s past. Moscow cemetery conservation, however, focuses more on single graves and buildings than on the protection of the cemetery as an ensemble (see, e.g., Moscow government, Citation2019, for a heritage protection order of Vvedenskoe cemetery), which leads to the fragmentation of cemetery space as acknowledged by a representative of the Moscow Department of Cultural Heritage:

People usually associate a necropolis [cemetery] with abandonment, emergency condition, something not very beautiful visually. There is no understanding that there can be unique things. … And when we renovate just some items, you cannot see the value of the whole picture. I would like to tell people about heritage through conservation, to make people perceive a cemetery not as a cemetery but as a cultural place, an outdoor museum. (Interviewee S)

Moscow cemeteries make room not only for heritage sites, but also for greenery. Cemeteries’ contribution to green infrastructure is the second theme which reveals their multifunctional dimension. Moscow cemetery vegetation has been planted mostly by the bereaved at the graves and grown without any control or maintenance. Therefore, Moscow cemeteries are green spaces, providing access to urban nature and, perhaps, serving as a biodiversity habitat similar to the historic cemeteries in other countries (Kowarik et al., Citation2016). On the negative side, out-of-control mature vegetation, together with the density of individual graves and a lack of a proper system of paths, makes maintenance challenging (Karavaeva, Citation2007). According to the Moscow Planning and Construction Norms (Moscow government, Citation2000), no less than 20% of the cemetery territory should be taken by greenery, which, as explained by an expert in environmental management interviewed for this study, is supposed to increase the quality of the soil to facilitate decomposition.

Moscow planning documents ascribe a utilitarian role to cemetery greenery. The City Urban Planning Code (Moscow government, Citation2008a) divides green spaces into three categories: public usage (accessible to all citizens; e.g., pocket parks, parks, gardens), limited usage (accessible for a particular group; e.g., the courtyards and green spaces adjoining educational and health facilities) and special usage. Cemeteries, alongside technical green spaces (special buffer zones for water and fire protection, areas along roads and railroads) are included in the last category and, thus, distinguished from public green spaces. In the discussion around Moscow’s green infrastructure in the City General Plan (Moscow government, Citation2010) there is no mention of cemeteries, so their role as public green spaces that give citizens access to nature and provide habitat for wildlife and vegetation is overlooked.

The third theme revealed in the analysis is cemeteries’ actual use and the way cemetery authorities accommodate such use. According to the rules for behavior at Moscow cemeteries (Moscow government, Citation2008b), visitors must keep public order and must not make noise; some activities (many of them are outdated now) are prohibited, such as walking dogs, using cemeteries as a place for pasture, wood and sand, entering the cemetery outside working hours or providing commercial services. Moscow cemeteries are closed during the night and open from 9:00 to 19:00 from May to September and from 10:00 to 17:00 during the other months of the year (Moscow government, Citation2008b). During my field visits to Moscow cemeteries, I observed mostly activities centered around visiting graves, but there were also people who strolled quietly around the cemetery or came for an excursion (see ). The spread of such cultural leisure activities varied across the cemeteries I visited and was more prominent at the cemeteries situated close to the city center, within a densely built environment. I did not observe any types of more active recreation, such as doing sports or walking dogs.

Figure 4. An excursion devoted to cemetery art and history. Vvedenskoe cemetery, Moscow. June 2018. Photo by Pavel Grabalov.

Unlike other regions—for example, Scandinavia (Wingren, Citation2013)—where urban cemeteries are often characterized by a remarkable landscape design and a higher level of upkeep than at parks, Moscow cemeteries demonstrate poor organization of landscape and a lack of care compared to other public spaces in the city. According to the drafted revised Federal Funeral Law (Gosudarstvennaya Duma, Citation2020), a cemetery should have lighting and a navigation system and can be divided into functional zones, such as the entrance, ritual, service, burials and greenery. The entrance of the cemetery should have benches, public toilets, water for gardening, sand, rubbish containers and a gardening tools rental service. This basic provision can already be found at some Moscow cemeteries, but more developed infrastructure for recreational visitors, such as a navigation system, a clear path structure and benches, is still missing. The city agency Ritual has announced a program called My Cemetery (Моё кладбище), similar to the famous My Street (Моя улица) program of the Moscow public space improvement campaign (Trubina, Citation2020). A press-release of the agency claimed that the program aimed to reconstruct 52 Moscow cemeteries and ensure they are “associated not with dark graveyards but with cozy places for visitation” (Shishalova, Citation2021, p. 236). However, the program My Cemetery has not been formally publicized apart from a brief mention in a press release. A funeral industry expert interviewed for this study suggested that such a program did not actually exist and could be just a PR effort. Several interviewees noted a lack of motivation of Ritual to develop any functions of cemeteries beyond interment provision.

According to a federal public opinion poll devoted to practices and meanings associated with cemetery visitation in Russia (Public Opinion Fond, Citation2014), 51% of the respondents did not like to be at a cemetery, mostly because of the “depressing atmosphere.” Moscow cemeteries are not planned and designed as welcoming multifunctional spaces, so they fit this public opinion. However, analyzing the empirical material, I came across an idea of a memorial park featuring some qualities of publicness. According to the authors of guidebooks for architects (Bogovaya & Teodoronskiy, Citation2014; Gorokhov, Citation1991), memorial parks are meant to be a special type of urban parks devoted to commemoration of honorable citizens and historical events and are intended to replace cemeteries in the future. A similar vision of future cemeteries as memorial parks was presented in the Soviet cemetery manual for architects (Tavrovskiy et al., Citation1985): apart from their primary function as a burial site, future cemeteries, or memorial parks, should become urban public spaces. Transformation of cemeteries into memorial parks was also supported by several interviewees and described as a desirable change. For example, a city planner said that “seeing a cemetery not as a place of grief but as a place of memory requires some mental change” (Interviewee J). Despite the formal recognition of the idea of a memorial park, there are no changes in how ordinary Moscow cemeteries have been planned and managed. Several interviewees pointed out that Moscow cemeteries did not have detailed planning and design documents, “dropping out of the architecture and planning and becoming just a utility service” (Interviewee L).

Some experts interviewed for this study suggested that reconstruction of cemeteries, endowing them with some physical features of city parks, would lead to more recreation: as a representative of a private funeral agency put it, “infrastructure would prescribe culture” (Interviewee D). Many interviewees, however, shared the idea that the utilitarian attitude to Moscow cemeteries at the policy level and the low presence of secondary functions, especially recreation, is related to Russian cultural and religious values. Nevertheless, it seems problematic to find what exactly these values involve and whether poor planning and management of Moscow cemeteries acknowledge them. For example, a representative of the Russian Orthodox Church denied any contradiction between cemetery excursions and a Christian view on cemeteries:

Cemeteries must be honored, visited, taken care of. The fifth commandment of God says, “Honor thy father and thy mother.” Christians always honored the deceased, but it has changed because death has become a taboo in the consumer society. No one wants to talk about it. Walking through a cemetery, no one wants to see an old epitaph by chance, “We were like you. You will be like us.” That is why people think that a cemetery is something scary. (Interviewee W)

Although this quote could be interpreted in terms of the spiritual dimension, it also deepens the understanding of what a Russian proper multifunctional cemetery might be and questions to what extent the contemporary Moscow cemeteries are honored and visited by the bereaved and other citizens.

Discussion and concluding remarks

The four-dimensional analytical framework used in this study helped to reveal essential aspects of Moscow cemeteries as a public space. The cemeteries of the Russian capital are intrinsically liminal in sense of their physical separation from the surroundings, ambiguous positions in planning documents and pronounced tension between private graves and general publicness. Cemeteries are also inherently spiritual as they provide a space for spiritually meaningful practices of grave visiting and pilgrimage. The prominence of the idea of private cemeteries and the practice of selling grave plots support the cemeteries’ commercial dimension. Finally, Moscow cemeteries are multifunctional spaces because they accommodate heritage sites, urban greenery, excursions and recreational strolling.

Embodied spiritual aspects are among cemeteries’ characteristics which are difficult to incorporate into utilitarian planning policies. Contrary to the Soviet times, in contemporary Moscow, there is no lack of churches and other religious buildings, but the spiritual dimension of the city’s cemeteries is still prominent and manifests in a variety of forms and rituals. Cemetery planning and management need to be sensitive to this dimension and accommodate citizens’ spiritual needs beyond memorialization and commemoration practices, which is an especially prominent task in postsecular cities (Beaumont & Baker, Citation2011). The language of municipal spirituality (McClymont, Citation2015) that was developed in the British context but is nevertheless relevant for Moscow allows planners and policymakers to acknowledge the spiritual dimension of urban cemeteries and incorporate spiritual aspects into urban development. Moreover, as international research (Nordh et al., Citation2017) on cemeteries shows, spiritual qualities are essential for cemeteries’ restorative potential for different groups of citizens (a similar idea was shared by a social infrastructure planner cited above).

The paper also highlights the interrelation between the policy framework and the way people use cemeteries. According to Rugg (Citation2022), the economics of the cemetery business defines the status of the user as a citizen, consumer or powerless “supplicant.” In Russian cemeteries, the user is also a laborer who actively takes cares of the grave of the loved one. Through “cemetery labor,” inhabitants can use and physically change the urban environment localized in a grave to an unprecedented for other types of public spaces degree. Following Henri Lefebvre’s notion of the right to the city, Moscow cemeteries provide an opportunity for citizens to appropriate space. However, as Purcell (Citation2002, p. 103) notes, “not only is appropriation the right to occupy already-produced urban space, it is also the right to produce urban space so that it meets the needs of inhabitants.” In this sense, it is not clear if the “cemetery labor” in Moscow fulfills the need of the citizens to personalize commemoration in public space or can be explained by a lack of resources and the overall low-quality cemetery infrastructure. I think that these two sets of reasons exist side-by-side.

The commercial dimension of Moscow cemeteries can be interpreted in view of the so-called “end of public space” (Mitchell, Citation2017), which was proclaimed due to several trends, including privatization of public space. Being very uncritically adapted in Russia (Golubchikov et al., Citation2014), neoliberalism laid the foundation for the idea of private cemeteries to be embraced by professionals. Based on the experience in other countries, private cemeteries can provide an alternative to public overcrowded cemeteries although their long-term operation is challenging and can lead to “aggressive neoliberal managerial practices” (Rusu, Citation2020, p. 582). Moreover, as argued by Rugg (Citation2022), “the intervention of the private sector tends to exacerbate inequalities” (p. 871). The system of selling plots for “family (ancestral) graves” established by Ritual contributes to the rise of inequalities with regard to access to burial at Moscow cemeteries and physical reduction of publicly accessible parts of cemeteries in favor of the private ones. An administrative context might also contribute to the commercial dimension of Moscow cemeteries: Ritual is managed by the Department of Trade and Services, which oversees the commercial sector, such as retail, food and household services. Financial resources are essential for the sustainability of cemeteries, and it feels natural that those responsible for the graves should contribute to cemeteries’ maintenance and development. However, the system for such contributions should be built on the principles of social justice (Rugg, Citation2022).

Apart from the primary function of cemeteries, heritage aspects of Moscow cemeteries are the only other function articulated at the policy level. Taking into account the focus of the Russian state cultural policy on memorialization (Turoma & Mjør, Citation2020), cemeteries, which are memorial places by their nature, could be used as an ideological resource. However, there is no evidence available. Malysheva (Citation2018) demonstrates that the attempt of the Soviet Union to use cemeteries in ideological work failed as cemeteries “proved to be one of the most stable and archaic social spheres” (p. 357). One of the reasons why cemeteries have always been absent from the national memorialization discourse might be that they are viewed as spaces of personal memories rather than national glory, which would explain the lack of attention to ordinary Moscow cemeteries. Not every grave is or has to be a heritage one, but it does not mean that “ordinary” graves do not deserve public attention.

The idea of future cemeteries as memorial parks also demonstrates that public memory is viewed as a contradiction to private grief; however, grief is legitimate in the cemeteries which should be able to provide consolation for everyone who seeks it (Bachelor, Citation2004). Cemeteries are genuine public spaces because social encounters occur here through sharing private grief and memories in a public setting rather than through physical contact as it is practiced in other types of public space. Contemporary cities need a variety of public spaces which fulfill different needs and address different audiences (Carmona, Citation2015); therefore, cemeteries’ unique role as public spaces accommodating grief and contemplation should not be overlooked.

Different aspects and meanings exist simultaneously in cemetery space (Woodthorpe, Citation2011): Moscow cemeteries are both spiritual and commercial, liminal and multifunctional. The four dimensions nourish and contradict each other, shaping the policy gap this study has identified. The federal and city planning policies view cemeteries primarily in terms of interment provision and overlook their other functions. However, the complexity of the qualities Moscow cemeteries hold, as revealed in this attempt to analyses them as public spaces, should not be ignored if the authorities aim to build a human-centered city with a variety of types of public spaces available. Evidence from other cities undergoing densification demonstrates that this process might lead to reconfiguration of the role of cemeteries at the policy level and incorporation of cemetery development into larger urban planning goals (Grabalov & Nordh, Citation2020). This paper shows that Moscow policymakers to date fail to address the complexity of cemeteries’ functions and integrate cemetery legislation and spatial development visions and practices. To some extent, this failure explains the neglect and disorder of Moscow cemeteries.

A utilitarian view on cemeteries determines their exclusion from the priorities of Moscow spatial development, including the current public space improvement campaign run by the city government. The campaign was initially inspired by the ideas of human-centered, pedestrian-friendly and livability-focused urban development (Zupan & Büdenbender, Citation2019), yet pushing forward public space aesthetics rather than functional and political attributes (Kalyukin et al., Citation2015). Trubina (Citation2020) sees it as a case of speculative urban development which focuses on attractive visible results and quick fixes, ignoring the “unspectacular” parts of urban infrastructure. Based on the analysis presented in this paper, Moscow planners and policymakers mainly consider the primary function of cemeteries as burial grounds and places for personal commemoration without paying attention to cemeteries’ multifaceted role as public spaces (cf. similar findings of Klaufus, Citation2018 in Bogotá). Cemeteries belong to the unspectacular urban infrastructure and have many meanings, such as their spiritual aspects, which are difficult to address in policies and legislation. Therefore, including cemeteries in the public space improvement campaign seems problematic, and Moscow cemeteries are likely to remain invisible at the policy level public spaces.

Epilogue

This paper was written and submitted before February 24, 2022, when the Russian army brutally invaded Ukraine. This invasion demonstrates the dysfunctionality of both the Russian state and the Russian society—something that has been nurtured by the authoritarian regime led by Vladimir Putin for many years. The funeral industry is an integral part of this inhuman and criminal regime: in the beginning of his career in the Saint Petersburg government, Vladimir Putin himself supervised the city’s funeral industry and nonpublic arrangements of the market, according to an informant in Moiseeva’s (2013, p. 152) study. In this context, it is not surprising that Putin’s authoritarian regime cannot apprehend and care for the humanistic aspects of the funeral industry—and cemeteries in particular—but aims to create conditions for profit generation that benefits a favored few.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to all interviewees for their insightful stories and accounts. My special gratitude to Olga Ivlieva for help with the organizing of some key interviews. I would also like to thank Helena Nordh and Beata Sirowy for their vital support of the study and writing process. My sincere thanks to Oscar Damerham, Marianne Mosberg, Ioanna Paraskevopoulou and Yegor Vlasenko for providing valuable feedback on the drafts of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pavel Grabalov

Pavel Grabalov is an urban researcher with a recently awarded PhD degree from the Faculty of Landscape and Society, Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU). This paper is part of his PhD thesis devoted to the role of cemeteries across different urban contexts: “Urban cemeteries as public spaces: A comparison of cases from Scandinavia and Russia.” His research interests revolve around interrelations between people and their environments and how these interrelations are captured or ignored by urban planning and development policies.

Notes

2. I am grateful to Anna Mazanik for drawing my attention to the lectures of Friedrich Erismann.

3. The Russian sanitary legislation is currently being transformed drastically as part of a regulatory reform but is likely to keep sanitary protection zones for cemeteries. This paper analyses the legislation as of December 2020.

References

- Bachelor, P. (2004). Sorrow & solace: The social world of the cemetery. Baywood.

- Beaumont, J., & Baker, C. (2011). Introduction: The rise of the postsecular city. In J. Beaumont & C. Baker (Eds.), Postsecular cities: Space, theory and practice (pp. 1–11). Continuum.

- Blagojević, G. (2013). Problems of burial in modern Greece: Between customs, law and economy. Bulletin of the Institute of Ethnography, 61(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.2298/GEI1301043B

- Blinnikov, M. S., & Volkova, L. (2020). Green to gray: Political ecology of paving over green spaces in Moscow, Russia. International Journal of Geospatial and Environmental Research, 7(2), Article 2. https://dc.uwm.edu/ijger/vol7/iss2/2

- Bogovaya, I., & Teodoronskiy, V. (2014). Объекты ландшафтной архитектуры [Objects of landscape architecture]. Lan’.

- Bouchard, M. (2004). Graveyards: Russian ritual and belief pertaining to the dead. Religion, 34(4), 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.religion.2004.09.009

- Carmona, M. (2015). Re-theorising contemporary public space: A new narrative and a new normative. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 8(4), 373–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2014.909518

- Chief Sanitary Inspector. (1977). Санитарные правила устройства и содержания кладбищ [Sanitary Regulations for Cemeteries]. N 1600-77. https://docs.cntd.ru/document/1200007278

- Chief Sanitary Inspector. (2007). Санитарно-защитные зоны и санитарная классификация предприятий, сооружений и иных объектов [Regulations for Sanitary Protection Zones]. СанПиН 2.2.1/2.1.1.1200-03. https://docs.cntd.ru/document/902065388

- Chief Sanitary Inspector. (2011). Гигиенические требования к размещению, устройству и содержанию кладбищ, зданий и сооружений похоронного назначения [Sanitary Regulations for Cemeteries and Funeral Infrastructure]. СанПиН 2.1.2882-11. https://docs.cntd.ru/document/902287293

- Dushkina, N. (1995). The historic cemeteries of Moscow: Some aspects of history and urban development. In O. Czerner & I. Juszkiewicz (Eds.), Cemetery art (pp. 85–97). ICOMOS, Polish National Comittee.

- Erismann, F. (1887). Курс гигиены [Lectures on hygiene] (Vol. 1). Tipographia Kartseva.

- Erofeev, K. (2012). Вероисповедальные кладбища [Confessional cemeteries]. Prikhod, 3(105). http://www.patriarchia.ru/db/text/2259343.html

- Evensen, K. H., Nordh, H., & Skår, M. (2017). Everyday use of urban cemeteries: A Norwegian case study. Landscape and Urban Planning, 159, 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.09.019

- Fainstein, S. S. (2015). Social justice and urban policy deliberation: Balancing the discourses of democracy, diversity and equity. In F. Fisher, D. Torgerson, A. Durnová, & M. Orsini (Eds.), Handbook of critical policy studies (pp. 190–204). Edward Elgar.

- Federal State Statistics Service. (2020). Russian statistical yearbook. https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/Ejegodnik_2020.pdf

- Fischer, F., Torgerson, D., Durnová, A., & Orsini, M. (2015). Introduction to critical policy studies. In F. Fischer, D. Torgerson, A. Durnová, & M. Orsini (Eds.), Handbook of critical policy studies (pp. 1–24). Edward Elgar.

- Francis, D., Kellaher, L. A., & Neophytou, G. (2005). The secret cemetery. Berg.

- gbu_ritualofficial. (2021, October 18). Окружающая действительность … [Environment …] [ Instagram]. https://www.instagram.com/p/CVKR-mcAcr8/

- Golubchikov, O., Badyina, A., & Makhrova, A. (2014). The hybrid spatialities of transition: Capitalism, legacy and uneven urban economic restructuring. Urban Studies, 51(4), 617–633. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013493022

- Golunov, I. (2019). Bad company: How businessmen from southern Russia seized control of Moscow’s funeral industry, and who helped them do it. Meduza. https://meduza.io/en/feature/2019/07/01/bad-company

- Gorokhov, V. (1991). Городское зелёное строительство [Urban green construction]. Stroyizdat.

- Gosstroy. (2002). Рекомендации о порядке похорон и содержании кладбищ [Funerary and Cemetery Recommendations]. МДК 11-01.2002. https://ritual.mos.ru/normativnyeakty/MDK11-01.2002.pdf

- Gosudarstvennaya Duma. (2020). О похоронном деле в Российской Федерации … [Draft of the Funeral Law]. N 1063916-7. https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/1063916-7

- Grabalov, P. (2022). Urban cemeteries as public spaces: A comparison of cases from Scandinavia and Russia [Doctoral dissertation, Norwegian University of Life Sciences]. Brage Open Research Archive. https://hdl.handle.net/11250/3030771

- Grabalov, P., & Nordh, H. (2020). “Philosophical park”: Cemeteries in the Scandinavian urban context. Sociální studia/Social Studies, 17(1), 33–54. https://doi.org/10.5817/SOC2020-1-33

- Grabalov, P., & Nordh, H. (2022). The future of urban cemeteries as public spaces: Insights from Oslo and Copenhagen. Planning Theory & Practice, 23(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2021.1993973

- Hajer, M. A., & Reijndorp, A. (2001). In search of new public domain: Analysis and strategy. NAi Publishers.

- Jedan, C., Kmec, S., Kolnberger, T., Venbrux, E., & Westendorp, M. (2020). Co-creating ritual spaces and communities: An analysis of municipal cemetery Tongerseweg, Maastricht, 1812–2020. Religions, 11(9), 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090435

- Kalyukin, A., Borén, T., & Byerley, A. (2015). The second generation of post-socialist change: Gorky Park and public space in Moscow. Urban Geography, 36(5), 674–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2015.1020658

- Karavaeva, N. (2007). Социально-экологические аспекты изучения некрополя как феномена культурного наследия (на примере Москвы) [Socio-ecological aspects of studying necropolises as a cultural heritage phenomenon (the case of Moscow)] [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Lomonosov Moscow State University.

- Khmelnitskaya, M., & Ihalainen, E. (2021). Urban governance in Russia: The case of Moscow territorial development and housing renovation. Europe-Asia Studies, 73(6), 1149–1175. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2021.1937573

- Klaufus, C. (2018). Cemetery modernisation and the common good in Bogotá. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 37(2), 206–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.12599

- Kowarik, I., Buchholz, S., Von Der Lippe, M., & Seitz, B. (2016). Biodiversity functions of urban cemeteries: Evidence from one of the largest Jewish cemeteries in Europe. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 19, 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2016.06.023

- Kucheryavaya, M. (2021). Memorial space of the necropolis: The case of Novodevichy Cemetery. In I. R. Lamond & R. Dowson (Eds.), Death and events: International perspectives on events marking the end of life (pp. 48–62). Routledge.

- Kuznetsova, Y., & Levinskaya, A. (2020). Глава ГБУ “Ритуал”—РБК: “В Москве восемь агентов на одну смерть” [The head of Ritual—RBC: “In Moscow there are eight agents on one death”]. RBC. https://www.rbc.ru/interview/politics/08/10/2020/5f7b0a689a7947e66df9ee0c

- Laqueur, T. W. (2015). The work of the dead. Princeton University Press.

- Levkievskaya, E. (2006). Пасха” по-советски”: личность в структуре праздника [Easter in the Soviet way: A person in the structure of a celebration]. In Морфология праздника [Morphology of a holyday] (pp. 175–185). Saint Petersburg University.

- Loriya, Y. (2021). “Мы движемся в сторону очеловечивания отрасли” [“We are moving towards humanisation of the industry”]. Izvestiya. https://iz.ru/1137433/elena-loriia/my-dvizhemsia-v-storonu-ochelovechivaniia-otrasli?fbclid=IwAR3Bo4Mzwur8wrocAO–xHgOwmp12dHTwBydFvzYf0%E2%80%A6

- Low, S. (2020). Social justice as a framework for evaluating public space. In V. Mehta & D. Palazzo (Eds.), Companion to public space (pp. 59–69). Routledge.

- Malysheva, S. (2018). Soviet death and hybrid Soviet subjectivity: Urban cemetery as a metatext. Ab Imperio, 2018(3), 351–384. https://doi.org/10.1353/imp.2018.0066

- Malysheva, S. (2020). Soviet cemeteries. In P. N. Stearns (Ed.), The Routledge history of death since 1800 (pp. 406–422). Routledge.

- Mayor of Moscow. (2019). Все кладбища Москвы подготовили к весенним религиозным праздникам [All Moscow cemeteries have been prepared to spring religious holidays]. https://www.mos.ru/mayor/themes/1299/5598050/?utm_source=search&utm_term=serp

- McClymont, K. (2014). Planning for the end? Cemeteries as planning’s skeleton in the closet. Town and Country Planning, 83(6–7), 277–281.

- McClymont, K. (2015). Postsecular planning? The idea of municipal spirituality. Planning Theory & Practice, 16(4), 535–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2015.1083116

- McClymont, K. (2016). ‘That eccentric use of land at the top of the hill’: Cemeteries and stories of the city. Mortality, 21(4), 378–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2016.1151865

- Mehaffy, M. W., Haas, T., & Elmlund, P. (2019). Public space in the new urban Agenda: Research into implementation. Urban Planning, 4(2), 134–137. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v4i2.2293

- Merridale, C. (2003). Revolution among the dead: Cemeteries in twentieth-century Russia. Mortality, 8(2), 176–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357627031000087415

- Ministry of Construction. (n.d.). Проект стратегии развития жилищно-коммунального хозяйства в Российской Федерации на период до 2020 года [Draft of the Strategy of Development of the Russian Housing and Utilities Infrastructure]. https://acato.ru/media/downloads/news/Strategia_GKH_2020.pdf

- Ministry of Housing and Utilities. (1979). Инструкция о порядке похорон и содержании кладбищ в РСФСР [Funeral and Cemetery Management Instruction]. https://docs.cntd.ru/document/9011254

- Mitchell, D. (2017). People’s park again: On the end and ends of public space. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(3), 503–518. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15611557

- Moiseeva, E. (2013). Экономико-социологический анализ рынка ритуальных услуг в России [Economic and sociological analysis of the funeral market in Russia] [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. European University at Saint Petersburg, HSE University.

- Mokhov, S. (2021). Death and funeral practices in Russia. Routledge.

- Mokhov, S., & Sokolova, A. (2020). Broken infrastructure and soviet modernity: The funeral market in Russia. Mortality, 25(2), 232–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2019.1588239

- Moroz, A. (2021). Почитаемые склепы на Введенском кладбище в Москве: “Чёрный спаситель”—история культа [The venerated crypts in the Vvedensky cemetery in Moscow: “The Black Savior”—the history of a cult]. Etnograficheskoe Obozrenie, 1(1), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.31857/S086954150013603-3

- Moscow government. (1997a). Здания, сооружения и комплексы похоронного назначения [Moscow Construction Norms for Funeral Infrastructure]. МГСН 4.11-97. https://docs.cntd.ru/document/1200000477

- Moscow government. (1997b). О погребении и похоронном деле в городе Москве [City Funeral Law]. Закон N 11. https://docs.cntd.ru/document/3601419

- Moscow government. (2000). Нормы и правила проектирования планировки и застройки города Москвы [Moscow Planning Norms]. МГСН 1.01-99. https://docs.cntd.ru/document/1200003977

- Moscow government. (2006). Порядок подготовки и выдачи разрешений на захоронение на закрытых для свободного захоронения кладбищах [Rules for Application for Graves in Cemeteries Closed for New Interments]. N 802-ПП. https://docs.cntd.ru/document/3668320?marker=65A0IQ

- Moscow government. (2008a). Градостроительный кодекс города Москвы [Moscow Urban Planning Code]. https://docs.cntd.ru/document/3692117

- Moscow government. (2008b). О состоянии и мерах по улучшению похоронного обслуживания в городе Москве [Decree on the Conditions of Funeral Service in Moscow]. N 260-ПП. https://docs.cntd.ru/document/3688619

- Moscow government. (2010). Генеральный план города Москвы [Moscow General Plan]. https://genplanmos.ru/project/generalnyy_plan_moskvy_do_2035_goda/

- Moscow government. (2015). О проведении в городе Москве эксперимента по размещению семейных (родовых) захоронений [Regulations for Family (Ancestral) Graves in Moscow Cemeteries]. N 570-ПП. https://docs.cntd.ru/document/537979864

- Moscow government. (2017). Правила землепользования и застройки города Москвы [Moscow Land Use Plan]. https://www.mos.ru/mka/documents/pravila-zemlepolzovaniya-i-zastrojki-goroda-moskvy/

- Moscow government. (2019). Об утверждении охранного обязательства … Введенского кладбища [Heritage Protection Order for Vvedenskoe cemetery]. N 508. https://docs.cntd.ru/document/554839732

- Nordh, H., & Evensen, K. H. (2018). Qualities and functions ascribed to urban cemeteries across the capital cities of Scandinavia. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 33, 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2018.01.026

- Nordh, H., Evensen, K. H., & Skår, M. (2017). A peaceful place in the city—a qualitative study of restorative components of the cemetery. Landscape and Urban Planning, 167, 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.06.004

- Nordh, H., House, D., Westendorp, M., Maddrell, A., Wingren, C., Kmec, S., McClymont, K., Jedan, C., Priya Uteng, T., Beebeejaun, Y., & Venbrux, E. (2021). Rules, norms and local practices—A comparative study exploring disposal practices and facilities in Northern Europe. OMEGA—Journal of Death and Dying, 003022282110421. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228211042138

- Pirogov, V. (1996). Архитектурно-планировочные особенности московских кладбищ и мемориалов XVIII—начала ХХ веков [Architectural and planning characteristics of Moscow cemeteries and memorials in 18th—beginning of the 20th century. In I. Bondarenko (Ed.), Архитектура в истории русской культуры [Architecture in the history of Russian culture] (pp. 148–157).

- Public Opinion Fond. (2014). Практики и смыслы посещения кладбищ [Practices and meanings of visiting cemeteries]. https://fom.ru/TSennosti/11810

- Purcell, M. (2002). Excavating Lefebvre: The right to the city and its urban politics of the inhabitant. GeoJournal, 58(2), 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:GEJO.0000010829.62237.8f

- Quinton, J. M., & Duinker, P. N. (2019). Beyond burial: Researching and managing cemeteries as urban green spaces, with examples from Canada. Environmental Reviews, 27(2), 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1139/er-2018-0060

- Rae, R. A. (2021). Cemeteries as public urban green space: Management, funding and form. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 61, 127078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127078

- Rugg, J. (2022). Social justice and cemetery systems. Death Studies, 46(4), 861–874. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1776791

- Russian Federation. (1996). О погребении и похоронном деле [Funeral Law]. Федеральный закон N 8-ФЗ. https://ritual.mos.ru/normativnyeakty/FZ-8.pdf

- Russian Federation. (2004). Градостроительный кодекс [Urban Planning Code]. https://docs.cntd.ru/document/901919338

- Rusu, M. S. (2020). The privatization of death: The emergence of private cemeteries in Romania’s postsocialist deathscape. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 20(4), 571–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2020.1845471

- Saladin, A. (1997). Ocherki istorii moskovskih kladbisch [Essays of history of Moscow cemeteries]. Knizhnyj sad. (Original work published 1916).

- Shishalova, J. (2021). Постпамять и постсмерть: Ландшафт как мост между мирами [Postmemory and post-death: Landscape as bridge between worlds]. Project Russia, 95, 227–256. https://prorus.ru/interviews/postpamyat-i-postsmert-landshaft-kak-most-mezhdu-mirami/

- Shokarev, S. (2020). Источники по истории Московского некрополя XII—начала XX века [Sources of the history of the Moscow necropolis in 12th—beginning of the 20th century]. Nestor.

- Sinergia. (2016). Мониторинг общественного мнения о системе ритуального обслуживания в городе Москве [Public opinion poll on the Moscow funeral industry]. https://www.mos.ru/upload/documents/files/3643/Ritual(2).pdf

- Skår, M., Nordh, H., & Swensen, G. (2018). Green urban cemeteries: More than just parks. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 11(3), 362–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2018.1470104

- Sokolova, A. (2018). Новый мир и старая смерть: судьба кладбищ в советских городах 1920–1930-х годов [New world and old death: Urban cemeteries in the 1920s–1930s USSR]. Neprikosnovennyy zapas, 117, 74–94. https://www.nlobooks.ru/magazines/neprikosnovennyy_zapas/117_nz_1_2018/article/19533/

- Sokolova, A. (2019). Soviet funeral services: From moral economy to social welfare and back. Revolutionary Russia, 32(2), 251–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546545.2019.1687188

- Staeheli, L. A., & Mitchell, D. (2008). The people’s property? Power, politics, and the public. Routledge.

- Swensen, G., & Skår, M. (2019). Urban cemeteries’ potential as sites for cultural encounters. Mortality, 24(3), 333–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2018.1461818

- Tavrovskiy, A., Limonad, M., & Benyamovskiy, D. (1985). Здания и сооружения траурной гражданской обрядности [Buildings and constructions of funeral civil rituals]. Stroyizdat.

- Trubina, E. (2020). Sidewalk fix, elite maneuvering and improvement sensibilities: The urban improvement campaign in Moscow. Journal of Transport Geography, 83, 102655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102655