ABSTRACT

In recent decades, various cities in Sweden have implemented school closures as a desegregation strategy. Using simulation models calibrated with administrative data for all primary and lower secondary schools in Stockholm, Sweden, we assess the potential impact of school closure on ethnic school segregation. More specifically, we study how the characteristics of the school to be closed, the local opportunity structure for the displaced students, and the student reallocation criteria influence the effects of school closures on school segregation. Our findings show that the change in ethnic school segregation is highly dependent on reallocation criteria and local opportunity structures. Moreover, they demonstrate that the current practices associated with school closures in large urban areas (i.e., closing minority-dominated schools in minority-dominated neighborhoods) are likely to be ineffective in reducing school segregation, especially when students are reallocated to their nearest school or to schools whose composition resembles that of their former schools.

Introduction

In recent years, persistent ethnic segregation in European and U.S. schools has fueled discussions of new strategies to mitigate segregation (Council of Europe, Citation2017; Nuamah, Citation2017).Footnote1 One such strategy, school closure, has been implemented in various cities in the U.S. and in Europe. The majority of school closures have been justified by population decline, low academic performance, unequal access to resources, and concerns about accountability (Delpier, Citation2021; Haynes, Citation2022; Lehtonen, Citation2021; Lund, Citation2021; Nuamah, Citation2017; Sunderman et al., Citation2017; Taghizadeh, Citation2016). In Sweden, however, where the education system is built on the ideals of equality of opportunity and educational equity (SOU, Citation2020), school closure has recently been adopted as an intervention aimed at increasing integration among different ethnicFootnote2 groups (Arneback et al., Citation2021; Kornhall & Bender, Citation2018; Taghizadeh, Citation2019; Wendle, Citation2020). When it comes to implementation, minority-dominated schools (i.e., schools where ethnic minority students constitute a majority of the student body) tend to be more affected by closure decisions than majority-dominated schools (Caven, Citation2018; Nerenberg, Citation2021; Taghizadeh, Citation2020b; Tieken & Auldridge-Reveles, Citation2019). The main assumptions behind the closure of such schools are that (1) schools with a high proportion of minority students contribute more to increasing segregation than schools with a higher proportion of majority group students, and (2) displaced students will be reallocated to new schools in such a way that the level of segregation will decrease and the academic performance of minority group students will increase (Kornhall & Bender, Citation2018; Lund, Citation2021; Taghizadeh, Citation2020b).

School closure decisions are mainly based on the characteristics of the school to be closed (such as the ethnic composition of students and the number of students enrolled at the school). However, there are two aspects of school segregation that might challenge the expectations that closure of a minority-dominated school will decrease segregation. First, strong positive correlations between residential and school segregation in most urban districts mean that the effects of closures will vary by location of the closed schools (Boterman, Citation2019; Frankenberg, Citation2013). Since there may be differences in how displaced students are reallocated to the destination schools, it is difficult to assess patterns in how the closure of certain schools can change ethnic school segregation. Second, the differences in population composition of students between neighborhoods lead to a variation in parental opportunities to choose which school one’s children will attend. These interdependencies between school choice opportunities and population composition mean that school segregation is a multi-faceted phenomenon (Burgess et al., Citation2015; DeLuca, Citation2012). Hence, to assess the effects of school closure on segregation one must account for factors that extend beyond the characteristics of a single school.

In this paper, we argue that a comprehensive assessment of the effects of school closures on ethnic school segregation must include three dimensions: (1) the characteristics of the closed school, (2) the reallocation criteria used to assign students to new schools, and (3) the local opportunity structure. The first dimension relates to which schools are targeted, the second to how the displaced students are reallocated, and the third to where the closed school is located in the city, and to what new school choice options are available to the students within the vicinity of the closed school.

Taking these three dimensions (i.e., school characteristics, reallocation criteria, and local opportunity structure) into account, this paper empirically evaluates the effects of school closure on ethnic school segregation. We study segregation across all primary and lower secondary schools in Stockholm, Sweden, which consist of grades 1 to 9 (ages 7 to 16). At the city level, we study segregation between all schools in Stockholm. At the local level, we study segregation between schools within the neighborhood of the closed school. Finally, at the individual level, we study the out-group exposure of minority group students. In our analyses, we draw on population-level administrative data from 2017. One advantage of using Swedish administrative data is that they provide access to information for all students and schools on a range of important characteristics that allow us to make a detailed evaluation of the effects of school closure on segregation. Moreover, Stockholm is the most populous Swedish city, with an over-representation of foreign-born residents from a range of backgrounds (20% in Sweden as a whole, 25.6% in Stockholm), and it is also one of the cities in which school and residential segregation have increased over recent decades (Böhlmark et al., Citation2015; Malmberg et al., Citation2018; SCB, Citation2022).

To assess how school closures can affect school segregation, we counterfactually simulate the closure of each school in Stockholm separately and test various reallocation scenarios. Desegregation strategies aim to reallocate students to schools with an ethnic composition that differs from that of their origin school (i.e., heterophilous reallocation). At the same time, the literature on school segregation suggests two alternative patterns of reallocation. First, due to the proximity preferences of parents, students are likely to be allocated to schools close to their former school. Second, due to preferences for certain ethnic composition, students are likely to be allocated to schools whose ethnic composition is similar to their former school (Denice & Gross, Citation2016; Hastings et al., Citation2005). Using simulations to test these reallocation scenarios allows us to quantify how much school segregation can change, based on the characteristics of the closed schools and the use of different reallocation criteria.

Our findings demonstrate that the effects of a school closure vary substantially by differences in the school opportunity structure for the displaced students and the reallocation criteria used to distribute them to new schools. We find that reallocating students to schools whose ethnic composition differs from that of the closed school consistently produces a pattern of reduced segregation at the city level (heterophilous allocation: −0.72 ± 0.66, random allocation: −1.09 ± 0.80, in percentage points). However, allocation scenarios that rely on the school choice patterns observed in the literature, i.e., those based on compositional similarity and proximity preferences, generate only a marginal decrease in segregation at the city level (homophilous allocation: −0.32 ± 0.33, assigning to the nearest school: −0.20 ± 0.30). Overall, we also find that the change in city level segregation is much smaller than changes generated at the local level (heterophilous: −24.16 ± 18.43, random: −1.55 ± 12.63, homophilous: −12.47 ± 13.96, nearest school: −8.40 ± 14.23). In addition, the change in local area segregation is highly dependent on the ethnic composition of the schools in those areas. Regarding the characteristics of the closed schools, our results show that the closure of large and ethnically homogenous schools—i.e., schools where 100% of the students are either of Swedish or minority background respectively—has a greater effect on reducing ethnic school segregation than the closure of small schools. The results also show that closing schools with a high proportion of minority students that are surrounded by schools with a similar ethnic composition decreases the chances of reducing school segregation.

Our empirical findings based on comprehensive simulation analyses add to the existing and growing literature on the outcomes of desegregation policies in large urban areas. At the student level, the school closures implemented in the U.S. and Sweden over recent decades have been shown to be mostly ineffective in increasing the academic performance of displaced students (Kirshner et al., Citation2010; Taghizadeh, Citation2020b). Since school closures are currently implemented in a way that primarily affects schools with a high proportion of minority group students, our study provides further empirical evidence that such closures are also likely to be ineffective in decreasing segregation. Moreover, our analytical approach not only addresses the effects of the characteristics of closed schools on school segregation but also takes the displaced students’ opportunity structure and various reallocation criteria into account, both of which are of major relevance for school segregation. Hence, our findings also speak to policymakers, since they demonstrate that school closure cannot be viewed in isolation but must be considered in relation to other factors that also contribute to school segregation.

School closure as a desegregation strategy

Since the beginning of the 2010s, the number of school closures has increased significantly in both the U.S. and Europe (Brazil, Citation2020; Green et al., Citation2019; Nerenberg, Citation2021; Taghizadeh, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). In addition to school-related factors, such as decreases in student enrollment, school bankruptcy, or poor infrastructure, education authorities may also resort to school closure as a potential solution to their accountability concerns (Delpier, Citation2021; Lee & Lubienski, Citation2017; Sunderman et al., Citation2017; Taghizadeh, Citation2020b; Tieken & Auldridge-Reveles, Citation2019).

Perhaps with the exception of this latter reason, school closures are primarily aimed at achieving a specific objective that benefits the students of the schools to be closed. One of the main aims of such school closures is to improve the academic performance of students. In the U.S., following the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act, Chicago, Philadelphia, and several other cities authorized the closure of low-performing schools (Burdick-Will et al., Citation2013; Delpier, Citation2021; Good, Citation2017; Nuamah, Citation2017). While low academic performance constitutes the most common reason for school closures in both the U.S. and Sweden, there has also been an increasing trend in various Swedish cities to utilize school closure as an instrument to mitigate school segregation (Kornhall & Bender, Citation2018; Lund, Citation2021).

Much like the racial integration policies implemented in the U.S. in the 1960s, such as school busing, various cities in Sweden have used school closure as a means of increasing ethnic school integration and improving the academic performance of minority students through peer effects. School closures are currently being implemented in Sweden with a focus on schools with a higher proportion of minority students. This resembles the closures that have been taking place across the U.S. over recent decades (Arneback et al., Citation2021; Brazil, Citation2020; Caven, Citation2018; Good, Citation2017). While there is no national policy of controlled educational integration in Sweden, various reports and studies have noted that school closures are expected to lead to the integration of minority groups with the majority population (Lund, Citation2021; Wendle, Citation2020; Wigerfelt, Citation2010). For example, in an interview study, Lund (Citation2021) found that Swedish authorities tend to justify the closure of schools with a high proportion of minority students by arguing that desegregation will increase the equality of opportunity for disadvantaged students. Moreover, they also argue that desegregation will lead to a greater social cohesion and will counteract prejudices.Footnote3 Although this reasoning appears to many to constitute a plausible argument for school closure, in this paper we argue that such reasoning overlooks several well-studied aspects of school segregation that challenge the argument’s validity, and that deeper analysis is therefore required.

A framework to assess the impact of school closure on school segregation

Given that current school closure interventions focus exclusively on the characteristics of the closed schools, they tend to disregard some of the key aspects of segregation processes. For instance, school choice options available to the displaced students and the criteria for allocating students to other schools are also likely to moderate the effects of school closure on school segregation. We expect that the effectiveness of school closures on desegregation will vary based on: (1) the characteristics of the closed school, (2) the reallocation criteria, and (3) the local opportunity structure for the displaced students.

Closed school characteristics

Several studies and reports by education authorities have noted that almost all schools that have been closed have been characterized by a student population with a high proportion of minority students (Arneback et al., Citation2021; Nuamah, Citation2017; Taghizadeh, Citation2019). This finding suggests that the following logic is in play: given that some schools are segregated (i.e., minority-dominated schools), closing a segregated school will reduce segregation. However, this rationale overlooks the fact that segregation measures the distribution of different ethnic groups across schools in a given city, and that all schools contribute to observed levels of segregation. For example, let us assume a hypothetical city with only two schools, and where the population of students consists of two ethnic groups. If one of the schools has an exclusively native student population and the other exclusively non-native students, the closure of either of these schools would have the same effect on reducing school segregation.

Moreover, segregation depends not only on schools’ ethnic composition but also on the schools’ sizes and on the relative size of different groups within the population (Elbers, Citation2021; Frankel & Volij, Citation2011; James & Taeuber, Citation1985; Massey & Denton, Citation1988). In large cities in particular, if a small school only hosts a very small proportion of the city’s minority student population, the school’s contribution to overall segregation at the city level will be marginal. In such a case, closing the school is also likely to have only a marginal effect on segregation. Given that real-world school segregation is much more complex than these hypothetical examples, studies of the effect of school closures on segregation must take variations in school size and school composition into account.

Reallocation criteria for the displaced students

Once a school is closed, there are two possibilities for the reallocation of students to alternative schools: students can freely choose a new school, or the education authorities can assign them to one or several schools. In the first case, students’ school choices are shaped by student and parent preferences, which points to the importance of the demographic characteristics of both the closed school and the alternatives that are available. Studies on school choice have consistently shown that school choices tend to be driven by ethnic and socioeconomic homophily, and by home-to-school proximity (Andersson et al., Citation2010; Ong & De Witte, Citation2014; Rangvid, Citation2010; Schneider & Buckley, Citation2002). As a result, majority group students tend to choose schools with a high proportion of majority students, while minority students tend to choose schools that have a higher proportion of minority students (Kristen, Citation2008; Lareau, Citation2014). Further, given that levels of school segregation reflect ethnic residential segregation to a large extent, choosing a new school that is located nearby to the school that has been closed will mean that the destination schools will be similar to the schools formerly attended by the displaced students, which will thus not have an effect on school segregation (Burgess et al., Citation2015; Frankenberg, Citation2013; Rich & Jennings, Citation2015).

The second reallocation strategy, i.e., allocation by the authorities, may mirror the first strategy if students are allocated to nearby schools. However, the authorities might also choose to assign students to new schools outside their neighborhoods in order to break the link between school segregation and neighborhood segregation (Reardon, Citation2016; Reardon & Owens, Citation2014). The segregation literature on busing provides a good example of this reallocation strategy. Busing policies were initially, and for the most part only, implemented in the United States. These policies aim to reduce school segregation by transporting minority students from schools with a high proportion of racial minorities to schools with a high proportion of White students. Since these latter schools were often located at some distance from the schools originally attended, the busing was carried out via public transport or a school transport system (Danns, Citation2014; Delmont, Citation2016; Eaton, Citation2001; Esteves, Citation2018). However, in countries where school proximity constitutes an important parental preference, it may be difficult to maintain such policy interventions in the long run, or they may even be impossible to implement as a result of public opposition (Delmont, Citation2016).

Overall, the evidence on the reallocation of displaced students in different countries is mixed and tends to reflect variation in the implementation of school closures. While some studies have shown that students tend to move to several different schools (Nerenberg, Citation2021), others have found that they tend to cluster in only a few (Ong & De Witte, Citation2014). When it comes to closed schools in Sweden, for example, Taghizadeh (Citation2020b) found that when parents were allowed to choose, a large majority of displaced students moved to the public school closest to home.

Local opportunity structure

Given the properties of segregation measures, to change segregation the exchange of students between schools should satisfy the so-called principle of transfers (James & Taeuber, Citation1985). Applied to the school closure context, the principle of transfers would imply that changes in segregation depend not only on the ethnic composition of the closed schools but also on that of the schools to which the students are reallocated. However, the set of schools to which students are likely to be reallocated is highly dependent on the spatial distribution and characteristics of the schools located close to the closed school, i.e., the local opportunity structure.

The local opportunity structure is particularly important as a result of the strong positive correlation between school and residential segregation (Boterman, Citation2019; Frankenberg, Citation2013). Given the tendency to attend a nearby school, residential areas with a high proportion of minorities are also home to schools with high proportions of minority group students (Bernelius & Vaattovaara, Citation2016; Burgess et al., Citation2015). This also implies that the school alternatives available to minority group students who attend schools in minority-dominated neighborhoods are likely to have similar characteristics, with the same applying to majority group students. The following extreme case example illustrates the relevance of this factor for school segregation. Suppose that in a hypothetical city there are four schools with the following distribution of students: Schools A and B are located close to each other, with each having 150 majority students and no minority students; schools C and D are also located close to one another, but lie further away from schools A and B, and have 75 minority students each and no majority-group students. If we closed school D and reallocated all of its students to school C, which happens to be a nearby school, there would be no change in the level of school segregation. Hence, the characteristics of the school choice alternatives for the displaced students constitute a critical factor for any potential change in segregation.

In sum, we argue that to form expectations about the effect of a given school closure on school segregation, one must analyze the contribution of each of the three aspects described above, i.e., closed school characteristics, the school opportunity structure for the displaced students, and the reallocation criteria, and also how these factors interact to bring about the observed level of segregation. In the remainder of this paper, we first introduce the Swedish context, the data employed in our analyses, and our methods. We then present the results of our empirical analyses, and we conclude with a discussion.

The Swedish context

The Swedish primary and secondary school system is based on a universal voucher system, which came into effect at the beginning of the 1990s. This policy change introduced both parental choice and independent schools (friskolor in Swedish, similar to voucher schools in the U.S. context) to the education system. In 2017, 113 out of 249 primary and lower secondary schools in Stockholm were independent schools, and about 25% of all students attended these schools (Skolverket, Citation2021).

Neither public nor independent schools are allowed to charge fees. All schools receive the same allocation per student, which is paid by the municipalities where students reside. While there are some minor differences between municipalities, parents can apply to send their child to any school in their city. Of course, this does not mean that all students get to attend the school to which their parents have applied. Since some schools are more popular than others, various allocation rules are used to sort among applicants. While proximity-based allocation rules dominate the admission process to public schools, a first-come-first-served rule guides the admission process to independent schools. Municipalities prioritize students on the basis of home-to-school walking distance and whether the student has a sibling who has already been enrolled at a given school. On the other hand, if students (or their parents) have not actively selected a school by the time of the application deadline, they are placed in one of the public schools near their home.

Over recent decades, Sweden has also experienced a demographic shift, from an ethnically homogenous toward a multiethnic society. In 1960, for example, immigrants and their children comprised only 4% of the total Swedish population; by 2020, this proportion had increased to 20% (SCB, Citation2021). This demographic change has increased the presence of minority students in Swedish schools, and thus led to a demographic transformation of the school system (Böhlmark et al., Citation2015). At the same time, there has been a concurrent increase in the level of residential segregation (Andersson & Kährik, Citation2016; Bråmå, Citation2008; Malmberg et al., Citation2018). Today, despite the existence of universal school choice, parents’ preferences for a nearby school as well as the proximity-based school allocation rules mean that patterns of ethnic school segregation in Sweden largely reflect the patterns of ethnic residential segregation (Andersson et al., Citation2012; Böhlmark et al., Citation2016; Burgess et al., Citation2015; Hastings et al., Citation2005; Kessel, Citation2018).

The Swedish school system has a decentralized governance structure, and the municipalities have substantial autonomy with regard to the opening and closing of schools within their administrative boundaries. Closures tend to be proposed by elected municipal politicians and evaluated by the municipal education board, on which all political parties are represented. The process of closing a school may then be started, depending on the education board’s evaluation, and this process then also includes choosing potential schools for the displaced students (as well as finding new workplaces for teachers) and communicating with the students and parents at the closing and destination schools. Following a closure, if students do not actively select a destination school, they are placed in one of the schools in their neighborhood (Taghizadeh, Citation2020b). Until the 2000s, school closures in Sweden were mainly driven by population decrease in various neighborhoods and rural areas (Taghizadeh, Citation2016, p. 37). Over the last few years, however, school characteristics such as academic performance and the ethnic composition of the students have become an important concern, and various municipalities have implemented school closures as a desegregation strategy (Örebro: Arneback et al., Citation2021; Nyköping: Kornhall & Bender, Citation2018; Taghizadeh, Citation2019; Trollhättan: Trollhättans Stad, Citation2021; Linköping: Wendle, Citation2020; Malmö: Wigerfelt, Citation2010).

Data and methods

Data

In the remainder of the paper, we test the extent to which school closures impact ethnic school segregation using empirically calibrated simulations and regression analyses. We employ population-level administrative register data on all primary and lower secondary schools and students in Stockholm in 2017. The register data provide detailed background information on each school, including the geo-coded location of each school at the level of 100 by 100-meter squares and detailed background information on all students.

The primary and lower secondary education in Sweden lasts 9 years (1st to 9th grade), and our data include 84,458 students in all grades who attended the 249 schools in Stockholm in 2017.Footnote4 Approximately 41% of the schools in our data include all grades (1 to 9), while 25.3% only offer primary school education, i.e., grades 1 to 6. The remaining schools only offer lower secondary education (grades 6 to 9), or only grades 1 to 3, 1 to 5, or 4 to 9, with each type constituting about 5% of all schools. Of the students, 93.3% reside in Stockholm, while the remaining 7% live in the neighboring municipalities but attend a school in Stockholm. Our analyses take account of differences in the schools’ grade-coverage by ensuring that the students from closed schools are only reallocated to schools that offer the grade level that the student had been attending in the closed school.

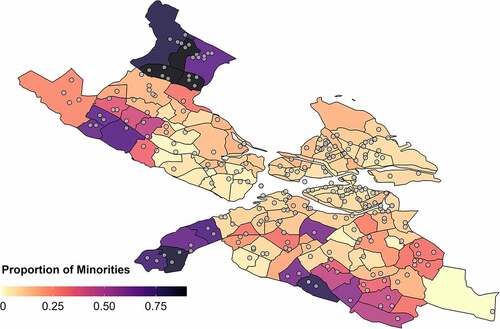

Given that data on racial identification are not available in Sweden, we study segregation on the basis of ethnic background, based on the migration history of students and their parents. We categorize students as the majority if one or both of their parents were born in Sweden, while those whose both parents were born outside Sweden are categorized as the minority. The majority group students comprise 73.85% of all students in our data and the minority group students 26.15%. shows the proportion of minority group students in different neighborhoods and schools in Stockholm in 2017. The points represent the schools in the city, while their colors show the proportion of minority students in each school. The areas with gray borders show neighborhoods (SAMS) designed by the Swedish Bureau of Statistics for market research purposes.Footnote5 The colors in each area indicate the proportion of minority students residing in these neighborhoods in 2017. As can also be seen from the figure, the composition of schools is highly reflective of the student composition in the surrounding areas; the bivariate correlation between the two is 0.76.

Measures

Closed school characteristics

The two school characteristics that we employ in the study are school size and ethnic composition. School size refers to the total number of students in each school. The least populous school in our data had six students, while the most populous had 1,051 students (mean: 339.19 ± 248.35). The majority of the larger schools include all grade levels (1–9), whereas smaller schools tend to offer primary school education (grades 1–6). In order to measure the ethnic composition of schools, we use the proportion of minority group students (both parents born outside Sweden) in each school. The proportion of minority group students in the 249 schools ranges from a minimum of zero to a maximum of one hundred percent, with a mean of 31.1% (±29.3).

Local opportunity structure

The local opportunity structure for displaced students is measured in terms of the similarity or dissimilarity of each school’s ethnic composition to the ethnic composition of nearby schools. To quantify the opportunity structures for the students displaced by school closure, we define local neighborhoods within a 2-km radius for each school. The 2-km threshold was chosen because this was the average distance between closed and target schools for those students who were displaced by school closures in Stockholm between 2008 and 2017. Using this 2-km radius around each school, we first specified local neighborhoods for each school in our dataset. We then calculated the difference in the proportion of minority group students between the focal school and the neighboring schools within this 2-km radius. The maximum number of schools in the neighborhoods is 38, with an average of 16.85 (±8.93) schools. One school in our data set had no other school within 2 km, and for this school, we instead employed a 5-km radius.

School segregation

Choosing measures of school segregation is an important part of examining the use of school closure as a means of decreasing segregation, since these measures provide an understanding of how segregated a given school system is, and thus of the effectiveness of school closures. We use the information theory index H to quantify the levels of segregation between majority and minority group students in different schools at the city level and at the local level (i.e., among schools within a 2-km radius of the closed schools). The information theory index is consistent with the principle of transfers and is also invariant to size differences between schools (James & Taeuber, Citation1985, p. 14; Reardon & Firebaugh, Citation2002). Moreover, it is an evenness measure based on entropy, and ranges between zero and one. When the composition of all individual schools is identical to the composition of the overall student population in the city, there is zero segregation. As the composition of different schools starts to deviate from the composition of the overall population, the level of segregation increases. A value of one indicates complete segregation, with all students attending schools comprised exclusively of students with the same background as themselves. Whereas our analyses of city-level segregation include all schools in the calculations, for local-level segregation, we measure segregation within the 2 km neighborhood around each school in our data. In Stockholm, the observed level of school segregation at the city level was 0.295 in 2017, while the average local-level school segregation was 0.162 (±0.088, min: 0.007, max: 0.483).Footnote6

At the individual level, we adopt an approach that quantifies the experience of the displaced students. To this end, we measure the out-group exposure of the minority group students prior to and after the closure event. Our exposure index quantifies the degree to which a member from one group is potentially in contact with members from another group in their school (Burgess & Platt, Citation2021; Davies et al., Citation2011; Hooijsma & Juvonen, Citation2021; Massey & Denton, Citation1988). The advantage of using the exposure index at the school- and city levels is that doing so also takes the relative group sizes of the majority and minority groups into account. That is, even if the proportion of majority-group students in a given school is high if only a very small proportion of the city’s population of minority students are attending that school, the out-group exposure of the school’s minority group students will still be low.

Analytical strategy

Dissecting the potential real-world impact of school closure on segregation constitutes a challenging task as a result of year-on-year changes in the population, the school market (i.e., new schools entering the market and others exiting), admission rules, and also in the between-school mobility of students. By restricting our focus to a single year, we are able to isolate our study from population changes both in schools and in the city. To ensure that our results are not driven by period effects, we also replicate the analyses using data for 2016, and we report these results in the appendix.

Given the complex ways in which closing one school can affect characteristics of other schools that are of primary importance to measure segregation (e.g., change in the ethnic composition of schools) and the role of reallocation criteria on these changes, we apply a simulation approach which allows us to capture those interdependencies in the school system (Epstein, Citation1999). Using simulations, we counterfactually evaluate the extent to which the closure of each school would impact segregation. Our simulation model is closely grounded on empirical data and provides an understanding of how school characteristics, in interaction with one another, can lead to changes in levels of segregation.

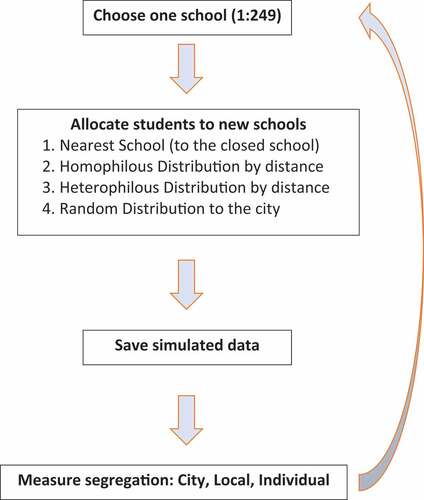

We start each simulation round in an environment where the characteristics of schools and students are identical to their real-world counterparts in 2017 on all observables. We simulate the closure of each of the 249 schools in our data separately and study four different school reallocation criteria to distribute the students from the closed school to alternative schools (see flowchart in ). That is, we start with the observed data from 2017, close one school, reallocate the students to new schools, and measure the change in ethnic school segregation produced by each of our four different reallocation criteria. After this step, we return to the original data, select another school to be closed and reallocate those students. This process is then repeated for each of the remaining 247 schools in our data. By analyzing all schools in the city, we aim to identify any statistical regularities in the effects that the characteristics of closed schools (vis-à-vis those of other schools in their neighborhoods) have on school segregation. To capture the effect of stochasticity on our simulation outcomes, we run 65 repetitions for each parameter combination.

Our four reallocation scenarios cover a range of possibilities based on both policy expectations and the findings from previous school choice studies. Each of these scenarios provides us with an understanding of the potential impact of closing schools with different characteristics and varying local opportunity structures. Given that the policy expectation is for student reallocation to result in a decrease in segregation, we implement two scenarios that are expected to decrease segregation: random reallocation and heterophilous reallocation. At the same time, research shows that most students are in fact likely to be reallocated to one of the schools that lie closest to the closed school and that parents are more likely to choose schools that have similar characteristics to their children’s previous school. We, therefore, test two other scenarios: assignment to the nearest school, and homophilous reallocation. Our four reallocation scenarios are operationalized in the following way:

Nearest School: The first reallocation method is a simple heuristic that allocates all displaced students to the school nearest to the closed school, which has also been found to be the most common pattern among displaced students in Sweden (Taghizadeh, Citation2020b).

Homophilous Distribution by Distance: The second reallocation scenario is based on a probabilistic method. Instead of sending students to the nearest available school, we choose their new school from among the schools located in the neighborhood of the closed school. As noted previously, we define these schools as those that are within a 2-km radius of the closed school. We then allocate students to the schools in this particular neighborhood based on the homophilous assignment. In this specification, we use multinomial sampling, weighted on the basis of compositional similarity between the closed school and the schools in the neighborhood. For the weighted similarity measure, we use the absolute difference in the proportion of minority students between the closed school and the alternative schools. In this way, more students are allocated to those schools in the neighborhood that are compositionally similar to the closed school, while fewer are allocated to dissimilar schools.

Heterophilous Distribution by Distance: In the third reallocation scenario, we again allocate students to the schools in the neighborhood, but this time using heterophilous assignment. This specification also uses multinomial sampling but is weighted on the basis of the compositional dissimilarity between the closed school and the alternative schools located within 2 km of that school. In this scenario, more students are allocated to those schools in the neighborhood that are compositionally different from the closed school, while fewer are allocated to schools whose composition is more similar to that of the closed school.Footnote7

Random Distribution: The final reallocation method is based on random distribution. We employ uniform sampling to choose one school from among the remaining 248 schools in the city for each student at the closed school. This method allows us to evaluate the potential lower bound of the segregational change that might be generated by the closure of each school.

In each of these scenarios, students are allocated only to schools that offer their grade level. That is, the students from a given closed school may have different school alternatives based on the grade levels offered by each school. Following each round of the simulation, we save the new data generated by the simulations (minus the closed school), and measure levels of segregation at the city and local levels using the information theory index (H). To compare changes in segregation at the individual level, we calculate the out-group exposure of minority group students. Here, the change in segregation is measured as the difference between the average level of out-group exposure among the minority students at their destination schools and their prior level of out-group exposure at the closed school. Positive values indicate increased potential exposure and negative values indicate decreased potential exposure.

Further, to quantify the marginal effects of school characteristics on school segregation in relation to each of the reallocation criteria, we estimate linear regression models. The school characteristics examined are the size of the closed school, the proportion of minority group students attending the closed school, and the weighted compositional dissimilarity between the closed school and the neighboring schools located within 2 km, which measures the local opportunity structure for students. The weighted dissimilarity measure used in the regressions comprises the average of the absolute differences between each school pair, weighted on the basis of the school sizes of the nearby schools. We also include interactions to evaluate how segregation is affected by the interaction between the ethnic composition of the closed school and the local opportunity structure for displaced students.

Results

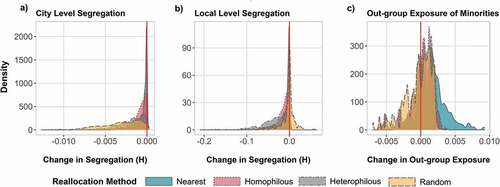

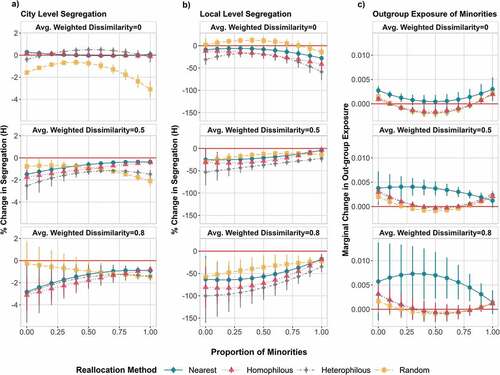

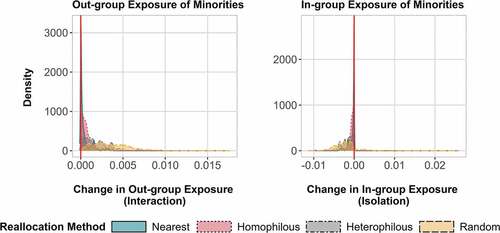

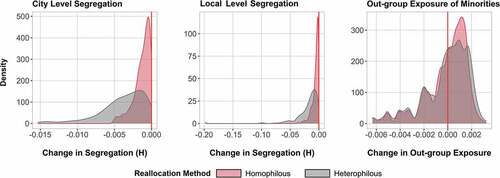

Using the four reallocation criteria described above, we counterfactually assess the closure of the 249 schools that existed in Stockholm in 2017.Footnote8 shows the change in segregation observed after closing each school and reallocating the school’s students using our four allocation rules. The x-axis in each panel shows the change in segregation, the y-axis shows density. The vertical red line in all three panels corresponds to no change. At the city level, panel a shows that while allocating students to the nearest school (blue area) reproduces the observed levels of segregation, random allocation (yellow area) tends to generate the largest decrease in segregation. Among the two weighted distribution methods, heterophilous school assignment (gray area) produces a similar degree of change to the random allocation method and produces a greater decrease in segregation than the homophilous weighted distribution (red area).

Figure 3. Density of schools based on the change in segregation generated by their closure. (a) City-level segregation, measured using the two-group information theory index, H. In Stockholm, the observed level of segregation in 2017 was 0.295. (b) Local-level segregation, measured using the two-group information theory index, H. The local area is defined as the 2 km radius around the closed school. The average local-level segregation in the observed data is 0.162(±0.088, min: 0.006, max: 0.483). (c) Change in the out-group exposure of the minority student population to majority group students, measured only for students from the closed schools. For each closed school, and each simulation, the new level of exposure is the average of the minority students’ school-level exposure at their destination schools.

In panel b of , we see that a heterophilous school assignment decreases segregation at the local level more than a homophilous assignment. As was the case at the city level, allocating students to the nearest school tends to reproduce the observed levels of segregation (hence, the peak around zero on the x-axis). Interestingly, when we randomly allocate students to schools across the city, the closure of about half of the schools appears to result in increased rather than decreased segregation at the local level.

At the individual level, we evaluate how the out-group exposure of minority group students changes for those students who are displaced as a result of school closure. In panel c, we compare the students’ prior exposure at the closed school to the average level of exposure at their destination schools. Overall, we see that a majority of the closures increase the out-group exposure of the minority population to majority-group students, with the largest increases being observed when we allocate students to the nearest school (blue area). Apart from this, however, we find similar levels of change in out-group exposure using different reallocation methods.Footnote9

Closed-school characteristics and the school-opportunity structure for students

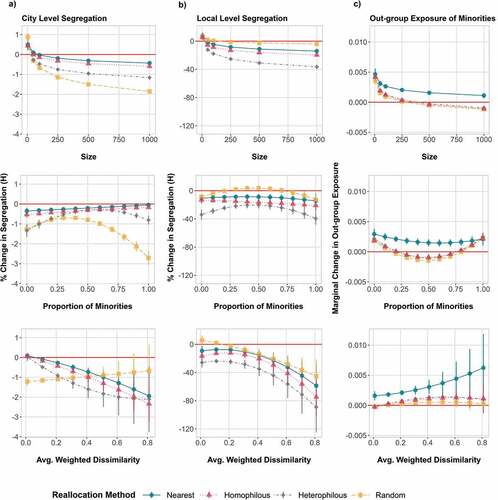

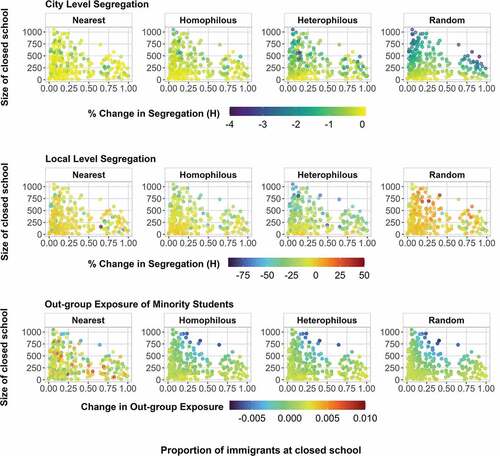

Next, we assess whether the changes in segregation presented in are generated by similar types of schools based on their size, ethnic composition, and the students’ local opportunity structures, which are measured as the average compositional dissimilarity between the closed school and the alternative schools located within 2 km of this school, weighted by the size of the alternative schools. We present the adjusted predicted change in segregation for each of these characteristics in (the estimated model results are presented in the Appendix). Each column in shows the adjusted marginal change in segregation (y-axis) at three distinct levels, (a) the city level, (b) the local level, and (c) the individual level, with respect to the different school characteristics (x-axes). The zero line shows no change.

Figure 4. Adjusted predictions for the change in segregation produced by each reallocation method, by closed school characteristics. (a) Percentage change in city-level segregation, measured by the information theory segregation index, H. (b) Percentage change in local-level segregation, measured by the information theory segregation index, H. (c) Marginal change in the out-group exposure of minority group students (destination schools—closed school).

At the city level (column a), we see that for all three characteristics the nearest school allocation method (solid blue lines) produces the smallest change in segregation, followed by homophilous assignment (red lines), and heterophilous assignment (gray lines). The decrease in segregation produced by these three allocation criteria tends to be driven by large schools, schools that are more homogenous (with either a lower or a higher proportion of minority group students), and schools that are compositionally more different from other schools in their neighborhood (i.e., where the average weighted dissimilarity is higher). The changes produced by random allocation, however, tend to vary depending on school characteristics. When students are randomly allocated to other schools in the city, the closure of schools that are compositionally more similar to the neighboring schools (third row, avg. weighted dissimilarity close to 0) tends to decrease city-level segregation, but the closure of the largest schools (first row), and of schools that are more homogenous (second row), tends to decrease city-level segregation to a greater extent.

At the local level, and independent of school characteristics, we see that the largest decrease in segregation is achieved when students are allocated based on the heterophilous reallocation criterion (column b, gray lines), followed by homophilous allocation (red lines), and the nearest school allocation criterion (blue lines). Changes in local segregation are also driven by the closure of more homogenous schools, schools with higher student numbers, and schools whose population characteristics differ from those of the neighboring schools. Column b in shows that when we distribute students randomly to the other schools in the city (yellow lines), the closure of mixed schools (proportion of minority group students ~0.25–0.75) and of schools that are similar to their neighboring schools tends to increase segregation at the local level (which can also be seen in , column b). Regarding local segregation, the third row in shows that the existence of a wider opportunity structure for students results in a greater decrease in segregation independent of the allocation method (see, also in the Appendix, which presents scatter plots describing the change in segregation for each school, based on school characteristics).

Column c in presents the change in the out-group exposure of displaced minority students, showing that out-group exposure increases when students are allocated to the nearest available school. The results for the other allocation methods are rather mixed. Whereas the closure of small schools increases the out-group exposure of minorities, the closure of large schools tends to decrease the level of out-group exposure (column c, first row, red, gray, and yellow lines). Moreover, compared to the closure of mixed schools, the closure of homogenous schools increases out-group exposure (second row). On the other hand, for these three allocation criteria, we see that out-group exposure increases only if the schools are located in mixed neighborhoods and if the students are allocated on the basis of the homophilous or heterophilous reallocation criteria.

Overall, we see that the largest decreases in segregation observed at the city and local levels are generated by the closure of large schools, schools that have a more homogenous composition, and schools whose composition differs from that of other schools nearby. The increase in segregation at the local level observed in the case of random allocation tends to be due to the closure of mixed schools and of schools that are compositionally similar to their neighboring schools.

Interaction between ethnic composition and opportunity structure

We now turn to the analysis of how changes in segregation are moderated by the interaction between local opportunity structure and the ethnic composition of the closed schools. shows the adjusted marginal effects (y-axis) for the interaction between the proportion of minority students in closed schools and the degree to which the ethnic composition of the local neighborhood schools differs from the ethnic composition of the closed school, i.e., the average weighted dissimilarity in relation to the schools within a 2-km radius (x-axis). We measure the marginal change in segregation based on three levels of compositional dissimilarity: similar (0, first row in each column), mixed (0.5, second row), and dissimilar (0.8, third row).

Figure 5. Adjusted predictions for the interaction between ethnic composition and opportunity structure: Adjusted predictions for the marginal effects of the interaction terms between the proportion of minority students (x-axis) at closed schools, and the average weighted dissimilarity between the closed schools and neighboring schools within 2 km (Avg. Weigh. Dissimilarity in in the Appendix). Presented by different levels of compositional dissimilarity (rows) with the values: 0, 0.5, 0.8.

At the city level (, column a), when we use random allocation (yellow line), the closure of homogenous schools with a high proportion of either minority or majority group students tends to decrease segregation more when the composition of nearby schools is similar to that of the closed school (first row). However, if students are reallocated based on heterophilous assignment (gray lines), the closure of mixed schools (proportion of minority students ~0.25–0.75) that are located in mixed-school neighborhoods (first row) increases segregation at the city level. On the other hand, if students are reallocated on the basis of homophilous (red lines) or heterophilous assignment (gray lines), or to the nearest school (green lines), then the closure of majority-dominated schools that are more dissimilar to neighboring schools (second and third rows) decreases segregation more than the closure of minority-group dominated schools.

At the local level (, column b), other than in the case of random assignment following the closure of mixed schools that are very similar to their neighboring schools (first row), the overall pattern is one of a decrease in segregation for all other reallocation types and school characteristics. Independent of local opportunity structures, the heterophilous reallocation criterion (gray lines) results in the greatest decreases in segregation, followed by homophilous assignment, and then nearest school assignment. Among schools located in mixed areas (avg. weighted dissimilarity = 0.5, second row), the closure of schools with a high proportion of majority-group students decreases segregation more than the closure of minority-dominated schools.

Finally, at the individual level, when we allocate students using methods other than the nearest school criterion, closing schools that are both mixed (proportion of minority students ~0.25–0.75) and located in areas where the neighboring schools are similar to the closed schools (compositional difference = 0) produces a decrease in the out-group exposure of the minority students (, column c, first row). On the other hand, the closure of homogenous schools increases the out-group exposure of minority students, especially if these schools are located in areas where the ethnic composition of the neighboring schools is similar to that of the closed school (first and second rows). When the closed schools are compositionally quite different from neighboring schools (third row), we do not find a significant effect of the composition of the closed school on the out-group exposure of minority students, except in the case of nearest school reallocation. Overall, our results show that the potential change in segregation following the closure of a given school very much depends on the school’s characteristics, on student opportunity structures, and the reallocation method employed.Footnote10

Discussion and conclusions

School closure has long been one of the instruments to which authorities have resorted as a result of population shrinkage in rural areas (Egelund & Laustsen, Citation2006; Haynes, Citation2022; Lehtonen, Citation2021). Over recent decades, various large cities in both the U.S. and Sweden have also experienced an increase in school closures. While closures in the U.S. tend to be driven by low academic performance, many municipalities in Sweden have implemented closures as a desegregation strategy. Independent of the reason for closures, however, the common pattern in both settings has been that minority-dominated schools (dominated by racial minorities in the U.S. and students of immigrant origin in Sweden) have been more affected by school closure than majority-dominated schools (Brazil & Candipan, Citation2022; Taghizadeh, Citation2016; Tieken & Auldridge-Reveles, Citation2019; Weber et al., Citation2020). While much of the scholarly work on the consequences of school closure has focused on the individual level outcomes for students, in this study we focused on the macro level consequences of school closures, i.e., their effects on ethnic school segregation (Brummet, Citation2014; de la Torre & Gwynne, Citation2009; Gordon et al., Citation2018; Larsen, Citation2020; Taghizadeh, Citation2020b).

In order to measure the effects of school closures on school segregation, we have used a simulation framework that allows us to evaluate the effects of school closure from a multidimensional perspective across different scenarios. Our framework consists of three interconnected aspects: the characteristics of the closed school, the reallocation criteria, and the local opportunity structure experienced by the displaced students. Using empirically calibrated simulation methods based on administrative records for all primary and lower secondary schools and their students in Stockholm, Sweden, we have counterfactually analyzed how the closure of each of the 249 schools in the municipality in 2017 would change the level of school segregation, and how such changes are moderated by the three dimensions that are varied across our simulations.

Our findings demonstrate that allocating students to ethnically dissimilar schools generates a consistent pattern of reduced segregation at the city level. On the other hand, reallocation scenarios that rely on observed school choice patterns, i.e., those based on compositional similarity and proximity preferences, generate only a marginal decrease in segregation at the city level. Overall, the change in segregation is much larger at the local level than at the city level in all our reallocation scenarios. However, whether closures result in an increase or decrease in local segregation is highly dependent on the local opportunity structure and the relative compositional (dis)similarity between the closed school and the neighboring schools. Our findings show that school closure is likely to be least effective as a desegregation strategy in large urban areas when minority-dominated schools in minority-dominated neighborhoods are closed, especially when students are reallocated to their nearest school, or to schools that are compositionally similar to their school of origin.

We have studied the effects of school closure using a simulation framework that involves certain behavioral assumptions about school choice, and in an environment that is isolated from population changes. However, there are two factors that are likely to have an impact on the effects of school closure beyond those observed in our counterfactual simulations. First, we have only analyzed the immediate effects of school closure on school segregation, rather than the cumulative effects of such a closure (Tapia, Citation2022). Empirical evidence from the school segregation literature shows that school choices are dependent on the ethnic and socioeconomic characteristics of both students and schools (Billingham & Hunt, Citation2016). Once a school has closed, the reallocation of the displaced students might change the composition of the destination schools in a way that may trigger subsequent heterogeneous school mobility decisions in those schools after the first year (Brummet, Citation2014; Coleman, Citation1975). The transferred students may also subsequently change schools again (de la Torre & Gwynne, Citation2009), which adds to the long-term complexity of this issue.

Second, we have focused only on the consequences of school closures for ethnic school segregation and have not evaluated other factors that might be of relevance to school closure decisions, such as socioeconomic segregation or population change. Even when ethnic composition and socioeconomic status are correlated, the effects of school closures may differ at the individual level. For instance, when students are segregated on the basis of ethnicity and income, families whose incomes are higher than those of other families in a given closed school may be able to opt into schools other than those suggested by officials. Moreover, our study only measures potential changes in school segregation. Given that families’ school choices, and consequently their effects on school composition, are affected by many factors, such as population change and family dynamics, measuring actual changes in school segregation following school closure is a challenging task. A natural extension of our study would thus be to analyze the effect of school closure from a dynamic perspective and would require a large-scale simulation approach that takes interdependencies between mobility events and inequality and segregation in other domains into account (Tapia, Citation2022).

Nonetheless, on the basis of our rigorous, empirically calibrated simulation setting, we can conclude that the standard practices that characterize school closures (i.e., the closure of minority-dominated schools in segregated neighborhoods) are likely to be ineffective in decreasing ethnic school segregation, especially if they overlook the opportunity constraints that affect the displaced students. Our main findings, together with the following three aspects of school closures that have already been established in the research literature, raise serious questions about the effectiveness of school closure as a desegregation policy. First of all, school closures tend to be controversial. Closures tend to generate negative public reactions in the neighborhood of the closed school (Nuamah, Citation2017). Parents may also disagree with the decision to close a school, for example, because they perceive the closure as involving the loss of an important public service (Arneback et al., Citation2021; Egelund & Laustsen, Citation2006; Green et al., Citation2019; Lee & Lubienski, Citation2017; Lund, Citation2021; Taghizadeh, Citation2016).

Second, once the policy has been implemented, school closures may result in various unintended consequences. As has been the case with the busing policies employed in the U.S., forced integration policies may lead to a White flight from the destination schools and may even increase school segregation (Clark, Citation1987; Coleman, Citation1975; Danns, Citation2014; Delmont, Citation2016; Roda & Wells, Citation2013). In some cases, students may simply not choose to go to their “allocated schools,” making it difficult to plan transition policies for the displaced students (Gordon et al., Citation2018; Nerenberg, Citation2021; Taghizadeh, Citation2020a). Moreover, decreased segregation through the reallocation of students may not be sufficient for the integration of students within schools (Delmont, Citation2016; Kretschmer & Leszczensky, Citation2022; Leszczensky & Pink, Citation2015; McPherson et al., Citation2001; Wigerfelt, Citation2010). Displaced students may feel excluded and unmotivated in their new schools, and closures may even decrease the academic performance of these students (Kirshner et al., Citation2010; Steggert & Galletta, Citation2020).

Last but not least, as has been suggested by recent studies on the links between school closure and neighborhood change, the reasons for school closures such as low academic performance, decrease in enrollment, or racial composition also reflect the situation in the neighborhood of these schools (Bierbaum, Citation2020; Brazil & Candipan, Citation2022; Danns, Citation2014). In relation, the effects of the closure of a school are likely to extend to individuals and communities that have no direct ties to the closed school (Bierbaum, Citation2021; Brazil, Citation2020; Pearman & Marie Greene, Citation2022). That is, while changes in neighborhood characteristics can trigger school closures, the closure of schools may also impact the trajectory of the neighborhoods those schools are located.

To conclude, our empirical findings increase our understanding of how school closure may affect school segregation at the macro level, and they add to the growing evidence on the potential ineffectiveness of school closure as a desegregation strategy. Our findings strongly suggest that in designing school desegregation policies in general, and school closures in particular, policymakers should consider factors beyond the characteristics of the targeted schools. Those factors must take account of the local opportunity structure of students and allow for the understanding of segregation at different levels (i.e., at the city level, at the local level, as well as at the group level).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Hanno Kruse, Marc Keuschnigg, Jacob Habinek, as well as Stanford University SCANCOR seminar participants for helpful feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript. We also thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor for helpful comments and suggestions throughout the revision process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Selcan Mutgan

Selcan Mutgan holds a PhD in Analytical Sociology, and she is a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for Analytical Sociology, Linköping University, Sweden. Her research primarily concerns school and residential segregation, as well as spatial income inequality. Her current project focuses on the opportunity constraints in school and residential choices of families, and joint dynamics of school and residential segregation.

Eduardo Tapia

Eduardo Tapia holds a Ph.D. in computational sociology from The Autonomous University of Barcelona. He is a researcher at the Institute for Analytical Sociology of Linköping University, Sweden. As a segregation scholar, he applies statistical methods to analyze residential and school choices and large-scale simulation models to evaluate segregation dynamics and the potential effects of policy interventions.

Notes

1. Discussions and policies in the U.S. mainly refer to racial school segregation rather than ethnic segregation. Data on racial identification in Europe are largely nonexistent, however. Studies on ethnic segregation are therefore more common than studies on racial segregation, and ethnic categories tend to be described on the basis of country of origin. Throughout this study, we define ethnic segregation as segregation between majority group Swedes (students born to at least one native-born parent) and minority group students (students of immigrant origin, both of whose parents were born outside Sweden).

2. While desegregation policies in the U.S. are primarily focused on achieving racial integration, in most European countries, including Sweden, such policies focus on integrating those of immigrant origin with the native population.

3. While it is outside the scope of the current study, it is important to note that the implementation of school closures in Sweden is not uncontroversial. In both the U.S. and Sweden, some parents, local residents, and also students oppose closures by arguing that since closures mostly affect minorities (students of immigrant origin in Sweden, and Black and Latinx students in the U.S.) rather than their majority group peers, they tend to perpetuate societal inequalities (Good, Citation2017; Lund, Citation2021; Nuamah, Citation2017; Taghizadeh, Citation2016).

4. Since 2018, preschool grade (grade 0) is also part of the primary education in Sweden. We excluded schools with fewer than 5 students since these are more likely to be special schools. From the observed initial population of 91,766 students, we have excluded 7,308 students who had missing information on migration background or school location for either 2016 or 2017, because we also replicated the analyses for 2016. Overall, we excluded 4 schools from a total of 253 schools. In order to obtain a full picture of the school composition observed in our data, our analyses also include all students who were not residing in Stockholm but were attending Stockholm schools.

5. SAMS neighborhoods are Small Areas for Market Statistics, which are based on a non-administrative division designed for market research by SCB, the Swedish Bureau of Statistics. SAMS are commonly used in research using Swedish registers as proxies for neighborhoods. These areas can differ in terms of both their population size and their density, especially between different cities.

6. While the index score of 0.295 represents a historically high level of segregation for Stockholm, it is relatively low compared to the levels found in the U.S. Bearing in mind that it is not possible to directly compare levels of segregation between countries, Frankel and Volij (Citation2011) reported an index score of around 0.4 for school segregation in the U.S. in 2008.

7. In both weighted distribution types (homophilous and heterophilous), we sample 1,000 random vectors for the multinomial sampling.

8. We have also replicated the simulations using data for 2016, with equivalent results. See Appendix .

9. See Appendix for overall change in the out-group exposure as well as the in-group exposure of the minority group (isolation) at the city-level.

10. We have further replicated these analyses using a larger neighborhood definition, 5 km instead of 2 km. The results for the overall changes in segregation are presented in the Appendix, .

References

- Andersson, R., & Kährik, A. (2016). Widening gaps: Segregation dynamics during two decades of economic and institutional change in Stockholm. In T. Tammaru, S. Marcińczak, M. van Ham, & S. Musterd (Eds.), Socio-economic segregation in European capital cities: East meets West (pp. 134–155). Routledge.

- Andersson, E. K., Malmberg, B., & Östh, J. (2012). Travel-to-school distances in Sweden 2000–2006: Changing school geography with equality implications. Journal of Transport Geography, 23, 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.03.022

- Andersson, E. K., Östh, J., & Malmberg, B. (2010). Ethnic segregation and performance inequality in the Swedish school system: A regional perspective. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42(11), 2674–2686. https://doi.org/10.1068/a43120

- Arneback, E., Bergh, A., Jämte, J., & Trumberg, A. (2021). En skola i integration? Lärdomar från Örebro kommuns arbete med styrd skolintegration (Research Report). Örebro University. http://oru.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1553601/FULLTEXT02.pdf

- Bernelius, V., & Vaattovaara, M. (2016). Choice and segregation in the ‘most egalitarian’ schools: Cumulative decline in urban schools and neighbourhoods of Helsinki, Finland. Urban Studies, 53(15), 3155–3171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015621441

- Bierbaum, A. H. (2020). Managing shrinkage by “right-sizing” schools: The case of school closures in Philadelphia. Journal of Urban Affairs, 42(3), 450–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2020.1712150

- Bierbaum, A. H. (2021). School closures and the contested unmaking of Philadelphia’s neighborhoods. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 41(2), 202–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18785018

- Billingham, C. M., & Hunt, M. O. (2016). School racial composition and parental choice: New evidence on the preferences of White parents in the United States. Sociology of Education, 89(2), 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040716635718

- Böhlmark, A., Holmlund, H., & Lindahl, M. (2015). School choice and segregation: Evidence from Sweden. Working Paper No. 2015:8. IFAU - Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy. https://www.ifau.se/globalassets/pdf/se/2015/wp2015-08-school-choice-and-segregation.pdf

- Böhlmark, A., Holmlund, H., & Lindahl, M. (2016). Parental choice, neighbourhood segregation or cream skimming? An analysis of school segregation after a generalized choice reform. Journal of Population Economics, 29(4), 1155–1190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-016-0595-y

- Boterman, W. R. (2019). The role of geography in school segregation in the free parental choice context of Dutch cities. Urban Studies, 56(15), 3074–3094. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019832201

- Bråmå, Å. (2008). Dynamics of ethnic residential segregation in Göteborg, Sweden, 1995–2000. Population, Space and Place, 14(2), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.479

- Brazil, N. (2020). Effects of public school closures on crime: The case of the 2013 Chicago mass school closure. Sociological Science, 7, 128–151. https://doi.org/10.15195/v7.a6

- Brazil, N., & Candipan, J. (2022). The neighborhood ethnoracial and socioeconomic context of public elementary school closures in U.S. metropolitan areas. Social Science Research, 103, 102655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2021.102655

- Brummet, Q. (2014). The effect of school closings on student achievement. Journal of Public Economics, 119, 108–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.06.010

- Burdick-Will, J., Keels, M., & Schuble, T. (2013). Closing and opening schools: The association between neighborhood characteristics and the location of new educational opportunities in a large urban district. Journal of Urban Affairs, 35(1), 59–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12004

- Burgess, S., Greaves, E., Vignoles, A., & Wilson, D. (2015). What parents want: School preferences and school choice. The Economic Journal, 125(587), 1262–1289. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12153

- Burgess, S., & Platt, L. (2021). Inter-ethnic relations of teenagers in England’s schools: The role of school and neighbourhood ethnic composition. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(9), 2011–2038. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1717937

- Caven, M. (2018). Quantification, inequality, and the contestation of school closures in Philadelphia. Sociology of Education, 92(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040718815167

- Clark, W. A. V. (1987). School desegregation and white flight: A reexamination and case study. Social Science Research, 16(3), 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/0049-089X(87)90001-9

- Coleman, J. S. (1975). Recent trends in school integration. Educational Researcher, 4(7), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X004007003

- Council of Europe. (2017). Fighting school segregation in Europe through inclusive education. Position Paper. Council of Europe, Commissioner for Human Rights. https://rm.coe.int/fighting-school-segregationin-europe-throughinclusive-education-a-posi/168073fb65

- Danns, D. (2014). Desegregating Chicago’s public schools: Policy implementation, politics, and protest, 1965–1985. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137357588

- Davies, K., Tropp, L. R., Aron, A., Pettigrew, T. F., & Wright, S. C. (2011). Cross-group friendships and intergroup attitudes: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(4), 332–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868311411103

- de la Torre, M., & Gwynne, J. (2009). When schools close: Effects on displaced students in Chicago public schools (Research Report). Consortium on Chicago School Research at the University of Chicago Urban Education Institute. https://consortium.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/2018-10/CCSRSchoolClosings-Final.pdf

- Delmont, M. F. (2016). Why busing failed: Race, media, and the national resistance to school desegregation. University of California Press.

- Delpier, T. S. (2021). The community consequences of school closure and reuse [Doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University]. https://d.lib.msu.edu/etd/49756/datastream/OBJ/view

- DeLuca, S. (2012). What is the role of housing policy? Considering choice and social science evidence. Journal of Urban Affairs, 34(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2011.00598.x

- Denice, P., & Gross, B. (2016). Choice, preferences, and constraints: Evidence from public school applications in Denver. Sociology of Education, 89(4), 300–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040716664395

- Eaton, S. E. (2001). The other Boston busing story: What’s won and lost across the boundary line. Yale University Press.

- Egelund, N., & Laustsen, H. (2006). School closure: What are the consequences for the local society? Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 50(4), 429–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830600823787

- Elbers, B. (2021). A method for studying differences in segregation across time and space. Sociological Methods & Research, 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124121986204

- Epstein, J. M. (1999). Agent-based computational models and generative social science. Complexity, 4(5), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0526(199905/06)4:5<41::AID-CPLX9>3.0.CO;2-F

- Esteves, O. (2018). The “desegregation” of English schools: Bussing, race and urban space, 1960s–80s. Manchester University Press.

- Frankel, D. M., & Volij, O. (2011). Measuring school segregation. Journal of Economic Theory, 146(1), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jet.2010.10.008

- Frankenberg, E. (2013). The role of residential segregation in contemporary school segregation. Education and Urban Society, 45(5), 548–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124513486288

- Good, R. M. (2017). Invoking landscapes of spatialized inequality: Race, class, and place in Philadelphia’s school closure debate. Journal of Urban Affairs, 39(3), 358–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2016.1245069

- Gordon, M. F., de la Torre, M., Cowhy, J. R., Moore, P. T., Sartain, L., & Knight, D. (2018). School closings in Chicago: Staff and student experiences and academic outcomes (Research Report). University of Chicago Consortium on School Research. https://consortium.uchicago.edu/publications/school-closings-chicago-staff-and-student-experiences-and-academic-outcomes

- Green, T. L., Sánchez, J. D., & Castro, A. J. (2019). Closed schools, open markets: A hot spot spatial analysis of school closures and charter openings in Detroit. AERA Open, 5(2), 2. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419850097

- Hastings, J. S., Kane, T. J., & Staiger, D. O. (2005). Parental preferences and school competition: Evidence from a public school choice program. NBER Working Paper No. 11805. National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w11805.pdf

- Haynes, M. (2022). The impacts of school closure on rural communities in Canada: A review. The Rural Educator, 43(2), 60–74. https://doi.org/10.55533/2643-9662.1321

- Hooijsma, M., & Juvonen, J. (2021). Two sides of social integration: Effects of exposure and friendships on second- and third-generation immigrant as well as majority youth’s intergroup attitudes. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 80, 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.10.008

- James, D. R., & Taeuber, K. E. (1985). Measures of segregation. Sociological Methodology, 15, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/270845

- Kessel, D. (2018). School choice, school performance and school segregation: Institutions and design [Doctoral dissertation, Stockholm University]. http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1204635/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Kirshner, B., Gaertner, M., & Pozzoboni, K. (2010). Tracing transitions: The effect of high school closure on displaced students. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 32(3), 407–429. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373710376823

- Kornhall, P., & Bender, G. (2018). Ett söndrat land. Skolval och segregation i Sverige (Research Report). Arena Idé. http://arenaide.se/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/10/rap-skolval-final5.pdf

- Kretschmer, D., & Leszczensky, L. (2022). In-group bias or out-group reluctance? The interplay of gender and religion in creating religious friendship segregation among Muslim youth. Social Forces, 100(3), 1307–1332. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soab029

- Kristen, C. (2008). Primary school choice and ethnic school segregation in German elementary schools. European Sociological Review, 24(4), 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcn015

- Lareau, A. (2014). Schools, housing, and the reproduction of inequality. In A. Lareau & K. A. Goyette (Eds.), Choosing homes, choosing schools (pp.169–206). Russell Sage Foundation.

- Larsen, M. F. (2020). Does closing schools close doors? The effect of high school closings on achievement and attainment. Economics of Education Review, 76, 101980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2020.101980

- Lee, J., & Lubienski, C. (2017). The impact of school closures on equity of access in Chicago. Education and Urban Society, 49(1), 53–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124516630601

- Lehtonen, O. (2021). Primary school closures and population development—Is school vitality an investment in the attractiveness of the (rural) communities or not? Journal of Rural Studies, 82, 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.01.011

- Leszczensky, L., & Pink, S. (2015). Ethnic segregation of friendship networks in school: Testing a rational-choice argument of differences in ethnic homophily between classroom- and grade-level networks. Social Networks, 42, 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2015.02.002

- Lund, S. (2021). Styrd skolintegration för ökad likvärdighet och social sammanhållning. Pedagogisk Forskning i Sverige, 26(4), 4. https://doi.org/10.15626/pfs26.04.03