ABSTRACT

Municipal climate resiliency and re-naturing plans are promoting greening and green (re)development, such as the inclusion of new parks, greenways, or rehabilitated shorelines, frequently as a-political, win-win solutions for all residents. Greenwashing and (re)development of green amenities in vulnerable neighborhoods—those often most in need of support toward resilience and adaptation—expose residents to the impacts of green gentrification, such as the pricing-out and physical displacement from housing, socio-cultural displacement from public space, and associated personal and community traumas. This paper explores an under-researched avenue in the green gentrification literature: How do grassroots community activists organize to address housing and greening simultaneously and how do they operate to achieve justice in greening neighborhoods? We examined the strategies and tools used by community groups in 10 cities in the United States facing green gentrification. We find that justice-driven strategies and tools are supported by the formation of multi-sectoral coalitions which strengthen what we define as “community infrastructures”—social, economic, and political capacities—against exclusive green-washing. We argue that each of the three capacities must be built amongst residents in order to fortify the material and immaterial components of community infrastructure.

Introduction

Green gentrification has proven to be a controversial and complex challenge for urban planners and the community and nonprofit activist groups who mobilize with and on behalf of local residents with aims to achieve a more just, green city. While greening is much needed in communities that have long been deprived of the public health and well-being benefits of green space, such as increased outdoor activity with positive impacts on cardiovascular health, obesity rates, and stress levels (Cohen-Cline et al., Citation2015; Dadvand et al., Citation2018; Gill et al., Citation2007; Triguero-Mas et al., Citation2015), research has also demonstrated that green gentrification contributes to both residential and socio-cultural displacement as well as removal or exclusion from the benefits that are intended to emerge from green spaces and amenities (Anguelovski et al., Citation2021, Citation2022; García-Lamarca et al., Citation2020; Jelks et al., Citation2021). It can be what some call “disruptive green landscapes” for the health of historically marginalized groups (Triguero-Mas et al., Citation2021).

Yet, local governments often present urban greening as an a-political discourse, a win-win solution whereby all can benefit from the “good” of greening (Garcia-Lamarca et al., Citation2021), further framing any greening agenda through a performative lens that tends to deny any oversight of equity and justice, simply stating “green is good” (Angelo, Citation2019). Governmental action tends to overlook that in many global cities undergoing green (re)development both lower-income tenants and working-class homeowners are being priced-out of their neighborhood housing and/or socio-culturally displaced by greening and gentrification (Oscilowicz et al., Citation2022). In response to housing and green space displacement, community and grassroots activists in socially and ecologically vulnerable neighborhoods are organizing to demand improved housing affordability and accessibility rights simultaneously with more equitable green space/amenity rights (Anguelovski & Connolly, Citation2021). Previous research has provided case studies of such activism in the face of greening and gentrification (Alkon et al., Citation2020) while other research has attempted to identify some of the tactical developments within grassroots mobilizations for just and sustainable neighborhoods (Anguelovski, Citation2015; Derickson et al., Citation2021; Pearsall & Anguelovski, Citation2016, p. 201). However, no study has yet addressed the construction of multi-stakeholder and cross-issue coalitions that can respond to green exclusion and address concurring socio-ecological challenges. Recognizing this gap, this paper builds on the following question: How do grassroots activists organize to simultaneously address housing and greening and how do they operate to achieve justice in greening neighborhoods?

Drawing from interviews with 250 community activists, nonprofit employees, and municipal leaders in 10 cities in the U.S., we conducted a novel study at the intersection of green gentrification, community mobilization, and environmental justice. The originality of our work lies in exploring a diverse spread of mobilizations in neighborhoods experiencing green gentrification across a diversity of regional geographies and urban development histories based on data gathered from fieldwork conducted in 10 American cities. Our paper offers three contributions to the planning and community mobilization literature. First, we identify three mobilizing strategies and seven corresponding tools that coalitions use to address different processes and contexts of green gentrification and show how those strategies and tools are important transversal mechanisms for building social, economic, and political capacities. Those capacities are key because they make up the material and immaterial components of community infrastructure that can resist green gentrification (Pearsall & Anguelovski, Citation2016). We define the strategies discussed in this article as the plans of action made by coalitions and activists as a means to achieve an end goal and the tools discussed as the actions made within each strategy to achieve the end goals. Second, we discuss in which specific ways and innerworkings in which coalition building amongst community-serving actors/organizations and those outside the community can improve housing and greening equity outcomes (Chaskin, Citation2001b; Rigolon & Németh, Citation2018). Finally, building on these analyses, we offer a novel theoretical conceptualization of social, political, and economic capacities as components of community infrastructure—an essential characteristic of building neighborhood power in the context of unequal urban development.

The next section provides a literature review of green gentrification, displacement, and exclusion and connects it to the role that community infrastructure can play in addressing those threats. What follows is an explanation of our methodology and case selection, continued by a section detailing our empirical findings through the framing of multi-expertise coalitions that enhance social, economic, and political capacities of individual residents in order to strengthen the larger community infrastructure. We conclude the paper with brief reflections on the contribution of our analysis to green gentrification literature and discuss how our findings may be useful to activists themselves.

Distributive to procedural injustice concerns in the context of green gentrification

The body of literature studying green gentrification is growing and, at its core, considers the magnitude of socio-environmental riskscapes (Cole et al., Citation2021). It also explores the social impacts of new green amenities that privilege the white, wealthy, and educated in historically marginalized communities undergoing urban greening transformation (Anguelovski, Citation2016; Gould & Lewis, Citation2016; Immergluck & Balan, Citation2018; Pearsall, Citation2010). These urban greening transformations have taken the form of parks, gardens, nature preserves, recreational areas or greenways (Triguero-Mas et al., Citation2022) as well as climate-adaptive green roofs and buildings, run-off swales, and flood-resilient shorelines and canals (Staddon et al., Citation2018). A majority of the environmental gentrification literature has thus far focused on the distributional justice elements of green gentrification processes, such as physical displacement from green amenities as well as displacement and pricing out from housing within the periphery of these green (re)developments and amenities (Pearsall & Eller, Citation2020; Rigolon, Citation2017; Sax et al., Citation2022). More attention is recently being brought to procedural justice issues in green (re)development, focusing on by whom and under what processes are policy decisions for new green (re)developments made (Anguelovski et al., Citation2019; Krings & Schusler, Citation2020; Rigolon et al., Citation2020). Another emerging research stream highlights the importance of protecting housing rights for working-class residents in urban greening projects, including the preservation of affordable green housing, a housing model where housing costs remain below 30% of tenant income (Bouzarovski, Citation2022). Affordable green housing can indeed support sustainable, healthy living environments, including energy efficiency projects, access and inclusivity of green spaces and its benefits, and a walkable urban design (Ahn et al., Citation2014; Rigolon et al., Citation2020; S. Williams & Bourland, Citation2008). Meanwhile, in a scoping review of all literature related to green gentrification, (Quinton et al. Citation2022) frame the term green gentrification as an often nebulous joining of housing challenges that have arisen as a result of greening practices, further urging researchers to avoid the misrepresentation of any increase to property value as green gentrification

Focusing in on the United States, social inequality driven by race and racism remains central to the understanding of distributive and procedural dimensions of green injustice (Pulido, Citation2017) and is a factor in the unequal localization and typology of greening within American cities (Boone et al., Citation2009; Connolly & Anguelovski, Citation2021; Rigolon, Citation2016). Urban growth patterns of American cities in particular have been demonstrated to be a determinant of environmental injustice, with recent studies finding that cities with continuous high and rapid levels of growth in the postwar period exhibit the strongest relationship between increased greening and whiter populations (Connolly & Anguelovski, Citation2021). In addition, in public-facing discourse and municipal sustainability/greening plans, the experiences of socially marginalized residents of green gentrification-related displacement, loss, stress, and detrimental effects on well-being are largely omitted or replaced with perceptions of greening as “cleaning up” or “improvement” (Melstrom et al., Citation2021). This exclusion leads to a non- or diminished response to the needs and knowledge of those residents whom are often racialized, minority, marginalized, and most vulnerable to climate change and other urban transformations (Cole et al., Citation2019; Sharifi et al., Citation2021). In this context, some urban researchers—acknowledging and supporting the existing experiences, knowledge and agency of BIPOC, immigrant, racialized, low-income and other minority communities—have called for further investigation of the strategies and tools which activists employ to build green and just cities in order to better understand how and where community mobilization against green gentrification is occurring and what transformative potential they hold (Anguelovski et al., Citation2019; García-Lamarca, Citation2017).

Contestation and responses to green gentrification

As a preliminary prescription for the conundrum around greening as a potentially green locally unwanted land use (GreenLULU; Anguelovski, Citation2016), initial findings in the planning literature pointed a variety of community resistance practices against green gentrification (Pearsall & Anguelovski, Citation2016). This literature also identified “just green enough” practices as a municipality-led approach to prioritize consultation and participation with residents to resist displacement and exercise resilience through implementation of small-scale green planning and design interventions (Curran & Hamilton, Citation2012; Wolch et al., Citation2014). This practice has been presented as an alternative to larger, grander (re)development projects where investors would be drawn to speculate on real estate through investment next to and in greening projects (García-Lamarca et al., Citation2022). More recently researchers have found evidence that casts some doubt on the “just green enough” approach, demonstrating that many scales of greening interventions, from smaller greening interventions—such as urban gardens or climate mitigation interventions (Anguelovski et al., Citation2018; Jim, Citation2013; Loder, Citation2020)—to high profile green (re)development projects and iconic parks—such as the New York High Line (Black & Richards, Citation2020) or the Atlanta Beltline (Immergluck & Balan, Citation2018)—may result in displacement of long-term residents.

With these findings, planning practitioners and urban researchers have since argued to articulate strategies that can complement or move beyond “just green enough” interventions (Dooling, Citation2017; Mabon & Shih, Citation2018; Rigolon & Németh, Citation2020). They instead call for community-based research that can help prioritize long-term procedural justice and investigate the participatory processes of green (re)development strategies while incorporating comprehensive housing equity (Amorim-Maia et al., Citation2022; Oscilowicz et al., Citation2021; Rice et al., Citation2020; Shokry et al., Citation2021). These researchers and others (Anguelovski et al., Citation2022) point to the compounding incidences of displacement from housing or pricing-out of neighborhoods as a result of new green spaces or infrastructures as a critical frontier for novel investigation into residential and green space displacement. Here, direct engagement with affected residents and the supporting groups around them is seen as the basis of community-driven resistance and alternative building against unjust green cities. This approach is at the basis of our paper.

Conceptualizing “community infrastructure” as a foundation to housing and greening equity

Another integral component to the implementation of long-term procedural and distributional justice in greening cities is the concept of community capacity, or the realization of individual and collective action for the protection and improvement of social, political, and economic community well-being (Chaskin, Citation2001a; Dapilah et al., Citation2020; Freudenberg et al., Citation2011; Gil-Rivas & Kilmer, Citation2016). Previous community-based participatory research, especially public health studies (Lisovicz et al., Citation2006; Pothukuchi, Citation2005; Richter et al., Citation2005), has aimed to define capacity and sustainability as outcomes of a developed community infrastructure (Chaskin, Citation2001b; Shandas & Messer, Citation2008). We further operationalize and expand on this definition, arguing that community infrastructure is an outcome variable of strengthened social, economic, and political capacities of residents, which can emerge from or become visibly mobilized as a neighborhood experiences rapid socioeconomic disruption. Community infrastructure can be elaborated as the development of the material (organizational structures such as grassroots community associations and allies, as well as the physical spaces where residents can meet to strengthen capacities) as well as the immaterial (shared values, goals, care) networks that support a community over a longer period of time (Hacker et al., Citation2012). Care is indeed a central infrastructure to protect and advocate for and through in gentrifying neighborhoods (Binet et al., Citation2021), which our research further brings to the forefront. In short, we offer a novel conceptualization of the role of community infrastructure and define it as the material and immaterial backbone to community autonomy that provides determination to “stay put” while reinforcing longevity of self-directed outcomes.

We define social capacity as the ability of individuals within community to maintain and develop relationships that share common values in order to progress in achieving specific goals (Stupar et al., Citation2022). Social capacity is often rooted in place, where material and physical spaces provide opportunity for residents to deepen their capacity to maintain and develop relationships (Manzi et al., Citation2010; P. Williams & Pocock, Citation2010). Economic capacity refers to the ability of communities to maintain and develop financial resources to support the community’s goals and vision, including programming as well as physical infrastructure spaces such as community centers, gyms, and schools (Westwood, Citation2009). And political capacities include the ability of communities to mobilize for the purpose of collectively working together to tackle issues within community (Wang et al., Citation2012). Moreover, community infrastructure and its components provide the social, functional, emotional and spatial bonds of place attachment that act as an attachment “glue” to physical infrastructure (Hosseini et al., Citation2021). Nevertheless, community infrastructure, including each economic, social, and political capacity component held by community residents, has not yet been sufficiently examined and theorized in regard to community-based green urban planning, a key motivation for this paper.

Methodology

Our paper builds on the analysis of qualitative data systematically collected as part of a European Research Council–funded project which analyzed the social impact of urban green amenities as well as the relationship between green gentrification and community activism. Members of the research team conducted fieldwork between 2018 and 2020 in 24 mid-sized cities (defined as those with populations between 500,000 and 1.5 million residents) in Western Europe, Canada and the United States. These cities represent a diversity of urban development pathways, histories, (i.e., industrial and post-industrial, economically growing or shrinking; compact or sprawling), are geographically distributed throughout the regions included in the study. After a comprehensive review of gray literature, media articles, demographic change, and local expert input, we selected one (at times two closely located ones) gentrifying neighborhoods as our focus for qualitative field work in each city.

According to the parent project inclusion criteria, selected neighborhoods were experiencing or threatened by gentrification processes along with urban renewal or revitalization, high-end and luxury (re)developments, retail changes, and socio-demographic changes where new green amenity developments were also being implemented. All neighborhoods had also been or were about to be the site of different types of greening projects, including new or rebuilt parks, gardens, greenways, community gardens, waterfronts, canals and/or riverways. These changes were made evident by the arrival of socially privileged residents, increased property value, property taxes, and increased rental costs. Some of those changes were taking place in post-industrial neighborhoods with large amounts of cleaned-up and/or regenerated land (i.e., San Francisco) while others were located in marginalized neighborhoods, that is, places which had historically suffered from under-investment and abandonment, and where historically marginalized groups—working class and racialized people—were and are often still stigmatized and segregated (i.e., Dallas; Washington, DC; Portland). We verified these trends with quantitative data analysis wherein gentrification was measured using a neighborhood-scale index of multiple demographic indicators (Anguelovski et al., Citation2022). Each case also represented a unique urban history, specific gentrification dynamics and redevelopment projects, reflecting diverse relations between greening and development.

Study sample, data collection, and analysis

Field data collection in all case sites and analysis followed the same protocol. We pretested, modified and selected a final set of questions and probes for a semi-structured interview guide based on the overall aim of the larger study, from which this sub-study draws. Individual researchers spent approximately one month conducting intensive and targeted fieldwork in each neighborhood/city, after recruiting a diversity of participants representing community activists, city employees, developers, and community-based organizers to maximize the heterogeneity of perspectives on the topics of interest. In all cities, across Europe, the U.S., and Canada, 492 interviews were transcribed and coded, of which 250 were selected for this analysis from the American fieldwork. All data was coded through an initial round of thematic coding in Nvivo, identifying all interview materials related to community mobilization, activism, strategies, tools, housing, and greening. These codes were organized into two categories: general strategies and more specific tools within each of those strategies.

In a second stage, we elected to continue coding through a bottom-up inductive approach on American cities, as these cities demonstrated the greatest degree to which community mobilization, housing, and greening equity were discussed. Canadian and European data related to activism reflected a mitigated (comparatively to the American context) intensity related to intersectional challenges faced by activists, such as institutional racism, stigmatization of public/subsidized housing, that were discussed by American activists. After selecting only U.S. data, we aimed for diversity in the development type, continental geography, and economy of cities in the 10 U.S. cities/neighborhoods discussed (see ). For those 10 cases we conducted a more specific, targeted coding of 250 semi-structured interviews with key activists and community leaders discussing community mobilization strategies and tools related to housing and greening equity. In this second round of coding, we used a bottom-up, inductive approach focusing on the following codes: youth/children involvement; equitable housing relations; housing coalition; environmental coalition; business partnership; alternative housing; data gathering; and, among others, conservation. These codes were then cross-analyzed in a third stage in order to articulate the tools and strategies discussed in the results section of this paper.

Table 1. Overview of activist strategies and tools.

During this analysis, we also went back to our larger dataset to complement our understanding of community mobilization with contextual data obtained in our broader set of interviews. These were interviews that did not discuss community mobilization in great detail yet helped us understand unequal redevelopment and greening in each city. In some cases, original interview transcripts were revisited manually to cite exemplary statements made by community activists, community-based organizations, and municipal leaders. We selected quotes from these actors, demonstrating the expectations, understanding and importance of each of the analyzed strategies and tools. This grounded theory approach and coding informed the identification of strategies and tools utilized by mobilized activists and community leaders in response to green gentrification and related pressures in their neighborhood.

Limitations

While it was our goal to highlight common trends across cities while providing nuances in the exact strategies and tools deployed, it is important to recognize several limitations of this work. First, within each city, snowball sampling of interviewees occurred, leading to a non-representative sample amongst activists. However, while not exhaustive, our sample of 250 interviewees from 10 mid-sized U.S. cities represented a diversity of voices and histories of urban development and city typologies, increasing the generalizability of our findings in the U.S. context. Second, our analysis did not consider the outcomes or “successes” of all these strategies; instead, we focused on ongoing and continuing coalition work for urban green justice and call for future research on identifying the effectiveness of all the identified strategies. We bring attention to several tools that appear across the landscape of our case studies, pointing to the ease of application for these tools across different cultural, historical, and political contexts. Future studies should evaluate and monitor strategies of coalitions, partnerships, and programs between grassroots initiatives and non-community associated actors (Ruiz-Mallén et al., Citation2022). Moreover, future research may also identify the less frequently utilized strategies and tactics as these may also provide insight into unusual or special circumstances. Third, we did not pursue further analysis into scaling the degrees of intensity/power of capacity within community infrastructure (e.g., highest capacity vs. lowest capacity). Future research would likely provide significant contributions to planning literature should such a scale be produced. Last, our article does not analyze the question of limited accountability of local nonprofit groups, activists, and grassroots mobilizations in their actions and deliverables within their missions and objectives (Rigolon & Németh, Citation2018).

Identifying coalition strategies and tools to enhance community infrastructure in a green gentrification context

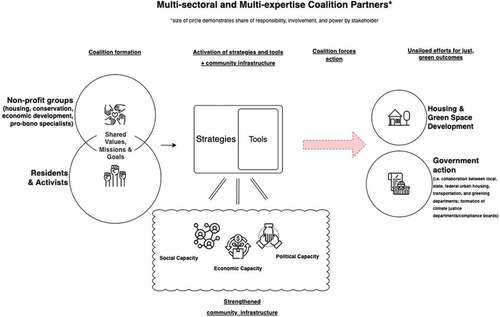

This section outlines the three major strategies we identified across the 10 neighborhoods studied, where each neighborhood was selected and analyzed with the observation that greening was contributing to displacement from both housing and new green spaces themselves (see, , Column 2 for more details on green plans/projects). These strategies and tools are adopted in tandem by coalitions made up of community organizations, nonprofit groups, and civic leaders as a means to reduce and prevent displacement from both housing and greenspace (). Identified strategies were observed in at least three of the 10 selected cities. Within each strategy, our analysis discusses tools that activists directly utilize in order to put their strategy to action. Throughout our results, we also point to the transversal mechanisms within each of the larger strategies and specific tools that then activate and strengthen the economic, social, and political capacities that make up what we define as community infrastructure (). We include representative quotes for many of the applied tools within each strategy, whereby we identify the gender and ethnicity/race of each speaker in order to better frame the context and positionality of each activist strategy and tool, while leaving other identifiable characteristics anonymous.

Figure 1. Three strategies and associated tools (7) utilized by coalitions of community residents, neighborhood alliances, nonprofit groups, and civic leaders that support strengthened community infrastructures in achieving just housing and greening outcomes.

Figure 2. Multi-sectoral and multi-expertise coalition partners for equitable housing and inclusive urban green amenities. The size of the circles represents which stakeholder groups we found to play a more central role in building urban green justice.

These strategies as well as their tools have impact at the neighborhood scale, however many of them are also inherently multi-scalar, interacting with the municipal or federal governments. In , we outline the results of the thematic coding of strategies and tools utilized by activists in the 10 cities/neighborhoods studied, the context of the greening in each neighborhood, and identification of the relevant coalitions involved.

Strategy: Affordable and accessible housing through participatory development

Tools for imagining and implementing alternative community-owned neighborhood development

In some cities where cost of housing has increased dramatically as a result of or as part of municipally implanted greening strategies, nonprofit groups and organizations are mobilizing around alternative neighborhood development schemes that can help secure affordable and accessible housing as well improvements to green amenities/spaces through enhanced participation. Three racially and ethnically diverse communities in three cities (Boston, Portland, and Washington, DC) have all implemented Community Land Trusts (CLTs)Footnote1 as an alternative development and housing model in cooperation with their municipalities in areas undergoing greening in order to direct the development of affordable housing, contribute to the equity growth of existing families, and protect the environmental quality status of a parcel of land. One white male housing community activist from the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI) in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston who has advocated for the development of a CLT in East Boston describes the immaterial components of housing, including heightened sense of ownership, strengthened sense of place, and positive health impacts, lending to strengthened social and political capacities, that have come as result of the Dudley Street CLT:

… to see a community or communal taking back of land and seeing that control and then putting it to good use … just that unifying force bringing people together around land and making sure that land is available long term. And then just I mean the cleaning up, that was the environmental justice issue … So initially I think it was a real environmental, health benefit of getting [the land parcel] cleaned up and then a source of pride.

By establishing a community-driven instrument for secure housing and community-driven development that also incorporates greening and environmental improvement, individuals describe the reduction of stress on families and the resulting generational impacts CLTs have on community, both lending to strengthened social capacity. The same housing activist in Boston explains the impact of an ecosystem of care within secure housing for community members on social, economic, and political capacity as well as the strengthening of political and economic capacity that the Dudley Street CLT would come to produce for its younger generations:

… having a base of homeowners means families … which means kids in the neighborhood who can participate in the DSNI youth program. Youth get involved at a young age in DSNI, maybe they live in the Land Trust, maybe they live next to somebody on the Land Trust, but they’re in the neighborhood and they’re benefiting from programs … [later on] they’re benefiting from a job, or you know college application program, and then if they move back to the neighborhood, they can get a home on the community land trust …

In the Anacostia neighborhood of Washington, DC, the Douglass Community Land Trust (DCLT) is under development at the time of writing of this article (fall, 2022) and is similarly driven by community leadership and economic development, as defined in the 2018 Equitable Development Plan. Leaders from the Douglass CLT remarked on the core values of the upcoming CLT, such as community control of both housing and greening development and programming as well as healthy housing that benefits the physical, emotional, and environmental quality of life for residents. As part of the CLT development, a white female leader from DCLT highlighted the need to ensure the immaterial stability of community leadership and power so as to best develop, manage, and secure affordable housing and wealth creation in the Black, working-class gentrifying neighborhood of Anacostia through the CLT:

So that notion of community control, the permanent affordability, the right to stay and thrive, the balancing public/community benefit with individual household benefit, and what that means is trying to create intentional pathways for asset building, wealth creation … [and] creating healthy sustainable environments … . [With inclusion and representation] of a diversity of voices [from the community].

Co-operative housing is another form of alternative equitable housing which can support strengthening economic capacity through generational wealth accumulation and serve as a form of social protection amongst vulnerable neighbors. Nonprofit community organizations, such as the Queen City Cooperative in Denver, have implemented a form of co-operative housing in centrally located, highly walkable and attractive green neighborhoods that rehabilitates existing housing and allows individuals or families to buy shares into a property and accrue limited equity over time, thus strengthening long-term economic capacity. One white male representative from Queen City Cooperative of Denver which operates in the gentrifying neighborhoods of Athmar Park and Capitol Hill, explains how the tool provides affordability to material housing, while still also allowing the tenant to build equity and generational wealth within their share:

[Co-operative housing] is a structure where people own shares of the house, you know that grows over time but it’s at a small rate. So if they were to own a house out in the world they would grow at the market rate and they would be able to sell it and buy it at whatever the market would bear but our house we want to grow at a smaller rate so we’re aiming for 3% in order to protect affordability but also balance the need for affordability with the members desire to build an asset that they can have.

In the American context of a liberal-democratic system with a history of de-funding social and public housing programs, utilizing existing federal financial schemes to benefit low-income housing is another alternative housing tool by which community and housing activists can mobilize to provide opportunity for affordable housing. The Detroit Shoreway Community Development OrganizationFootnote2 in Cleveland, Ohio, was able to leverage a critical public-private working partnership to address rising housing costs in a neighborhood along a newly redeveloped riverfront that was previously an industrial shoreline. It formed a nonprofit housing organization that was able to apply for the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) in exchange for 15 to 30 years of housing rates accessible to residents below 60% of median income in a new build or renovation. The nonprofit then partnered with a private developer with material capital means to construct the residential building, offering the developer the tax credit. The tax credit significantly reduces the cost of development, provides the developer incentive to participate, and retains low maintenance costs for the nonprofit housing manager. A MENA (Middle Eastern, North African) male nonprofit housing developer from CHN Housing PartnersFootnote3 describes the process for financing new affordable housing development in Cleveland’s Detroit Shoreway:

Say you build $1 million project, you can get a tax credit that’s worth up to $900,000. So, like I said we’re a non-profit, we don’t pay taxes so we can’t do anything with a tax credit. A bank, for example, has a very big tax bill so what they can do is they invest in our project, they give us $900,000 and we give them the right to take that $900,000 credit. So instead of paying their taxes, they’re paying us and then they get to reduce their tax bill. And so our $1 million project only has a mortgage of $100,000 because that’s all that’s left in there and that’s how we can afford to rent it out at a very low cost.

For many nonprofit groups, attracting public funds to secure housing stability and affordability and addressing overlapping environmental concerns has several challenges, especially in conservative states. In Dallas, housing activists described being confronted with little financial and legislative support from municipal and state governments, proving detrimental to community economic and political capacities, and further compounded by overturning of federal support by more conservative municipal planning committees and standards. For these housing activists, coalition building is imperative in order to provide affordable and subsidized housing particularly in neighborhoods that are seeing rapid increases to property taxes, rent, and cost of living after greening programs have been implemented by municipal government. Mobilization efforts amongst neighborhood coalitions of Black and Latiné communities within West Dallas during the toxins clean-up of a lead plant was crucial in the community-owned and -led development of two physical infrastructures that also provide a immaterial community of care to residential neighborhoods, ultimately enhancing the social, economic, and political capacities of residents: the Bataan Community Health Center (advocated for by the Latiné community) and the Benito Juarez Parque de Heroes neighborhood sports field (advocated for by both the Black and Latiné community in cooperation with a governmental nonprofit organization). As the health center and sports field were being built, the residents approached the funding of the material spaces differently as Black community residents were more readily accepting of cooperation and funding from institutional structures including governments and charities, while Latiné residents preferred an internal, self-funded grassroots approach.

Interviews with several housing activists in Boston, Denver, Cleveland, and Dallas also demonstrated how coalitions of community groups, citizen housing movements, and nonprofit developers utilized different tools to provide alternative housing arrangements in gentrifying neighborhoods undergoing new greening implementations. In turn, the coalitions and tools provided physical spaces for the strengthening of economic, social and political capacities of communities, which then deepened immaterial attachment to place and maintains longevity of secure housing in function. The same MENA male representative from CHN Housing Partners summarizes this process through an understanding of the organization’s mission statement:

Our motto is the power of a permanent address, and our primary objective is to promote the stability and health and economic vitality of communities and neighborhoods by making them more secure places to live, essentially our approach is that by stabilizing the household first in terms of having housing security that it kinda frees up family’s cognitive overhead, their ability to focus on other aspects of their lives.

While varied in their structure and approach, communities can more fluidly mobilize in cooperation with their municipalities, developers, or other residents to secure more affordable and safe housing as well as community-owned development.

Tools for using data science and technical knowledge toward more effective advocacy in urban planning processes and decisions

Effective advocacy tools and strategies from residents/activists toward municipal planners is critical to producing the foundation to a strong community infrastructure. This advocacy, in turn, produces a heightened sense of political capacity within civic coalitions. In cases in which residents and activists were under pressures from industrial to residential transformations, brownfield clean up and conversion, and increased redevelopment—such as Atlanta, San Francisco, and Seattle—community members partnered with external, pro bono specialists to sit on design review boards that would review, critique, and ensure new neighborhood developments would follow previously adopted community guidelines, a procedurally just step often overlooked as it can delay or redirect a project. In these three community cases, the partnership of citizen volunteers and pro bono technical specialists provided opportunity for in-depth investigation and consideration of the technical aspects of a project, particularly its contributions or changes to physical green spaces/amenities as well as consideration of a project’s immaterial impact on social, economic, political capacities within the community infrastructure. In speaking with an Asian male planner from the City of San Francisco, he explains the intensity of scrutiny during review and the improvements to communication amongst multi-expertise stakeholders as a result:

[The community is] really active around development. They’ve had for many years a really robust Design Review Committee that reviews every single development project that comes into the neighborhood, big and small. So, really conversant in design issues, planning issues.

Integration of residents into conversations with planning departments and urban experts was also accomplished in Portland, a city undergoing large-scale (re)development of neighborhood parks and construction of green transit networks catalyzing dramatic increased to rental costs. Members of the citizen’s group Antidisplacement PDXFootnote4 have been building political capacity by demanding rent control and consideration of the right to place for mobile home parks. Those affordable, low-cost housing units are indeed being threatened by applications for re-zoning to higher density, luxury developments. Here, a white male representative from Antidisplacement PDX speaks on the political capacity needed in order to conduct an effective land use negotiation between planners and mobile home residents, and how “data science” from below—communicated by residents themselves—has great value:

I think we were able to kind of bring this combination of the land use, technicalities, and knowledge to have a technical land use conversation with the Planning Bureau, but also have the campaign be led by mobile home residents themselves telling their own stories and bringing those stories to decision makers who have probably never set foot in a mobile home park before and had never met someone who lived in a mobile home park before.

Many activists we spoke with also described the need for technical data and science to provide material evidence for the housing and environmental injustices occurring in their neighborhood that could validate their claims to municipal planners, enhancing residents’ political capacities to advocate for themselves as well as economic capacities to fund community programming. In San Francisco, environmentally oriented community organizations appeared especially connected to evidence-based housing demands and environmental justice interventions and mobilizations. In Bayview Hunters Point, air quality presents a significant, enduring health issue for residents, particularly children/youth and the elderly—an issue around which residents have created different advocacy tools through a combination of youth engagement in data collection and citizen science. A Black, female community civic group advocate highlights how the workforce development programming for youth around contamination issues together with data gathering and analysis are enhancing political, social and financial capacities of participants and, in turn, community infrastructure:

It started with youth and they train them in all kinds of stuff and last summer they did ground-truthing … this year all 10 of that cohort is going to also be trained in this technology as well. So, the hope is, particularly if we can get some government or corporate agencies, part of their salaries will continue to be [funded].

Co-production of data and community-led data gathering when coupled with coalition-building is an important tool in holding municipalities and government organizations accountable, empowering residents’ political capacity through affirming their expertise of local knowledge, and building participatory coalitions between residents and nonprofit groups. By pairing immaterial epistemic knowledge and material observational data with theoretical expertise through citizen-public partnerships, housing and greening equity objectives may be more efficiently realized. The same San Francisco activist describes leveraging grassroots citizen science to create partnerships with health organizations and universities in order to apply for funding that benefits community economic capacity and political capabilities:

We just got [another] grant and we are just creating these theory committees and attempting to include every entity that has to do with the environment and with respiratory health and with maintaining and cleaning up the environment. Everybody that has to do with managing air quality [and] illnesses that are born out of air quality. We [will] have collected a trough of data that can validate these problems, that they cannot look past anymore, and require them to do something about it. Because historically it has been like our social association and splinter groups in the community. No one speaking in one voice. But with this grant, all of the community organizations are joined.

As neighborhood change and displacement pressures threaten communities, residents may not feel they have significant political capacity to review, provide feedback, prove, or discuss potential urban transformations. However, expert and citizen collaboration has been shown to provide opportunity for coalition building and partnership around data science, ultimately with opportunity to deliver evidence-based data around a variety of economic, social, environmental, and health concerns.

Strategy: Community programming, coordination, and facilitation

Tools for multi-sectoral programming, activities, and skill building

In interviews, we also heard how the organizing of programming, activities, and events amongst partnered civic organizations constitutes a powerful tool for strengthening social capacity by fostering sense of community and sense of place and thereby empowering residents to mobilize in response to other issues within their communities (e.g., lack of affordable or appropriate housing or exclusive greening) that often comes as a result of greenwashing or neighborhood transformation. Coalitions of community groups in Boston, Atlanta, Cleveland, Dallas, San Francisco, and Philadelphia each established programming for environmental stewardship and ownership, small-scale agriculture, family and children’s recreation, and more. In Boston, GreenRoots organizes Caminatas Verdes (Green Walks) for Latiné residents to help reclaim public space along the gentrifying green resilient shoreline in the East Boston waterfront. Many of these programs are aimed at supporting intersectional, vulnerable groups within communities, thus strengthening social, economic, and political capacities of those whom often have least capacity due to other burdens and responsibilities, further laying a strong foundation for a community infrastructure. In Atlanta, a Black male leader for Parks with a PurposeFootnote5 describes the multiple actions and purposes of the community environmental organization, all of which rely on the appropriation of green spaces by residents through improved outreach, educational tools, or fundraising. The environmental programming around ecological management, such as weed and native plant gardening, and urban agriculture, such as small-scale vegetable garden beds, strengthens social, economic, and political capacity and in turn community infrastructure:

… [the organization] is focused on developing parks in vulnerable and marginalized communities, helping them to develop not only new parks and green space but to sort of wring all the potential benefits out of the projects, so capturing storm water on site, incorporating edible landscapes, job training programs, working with partners on environmental education … We [also help residents] get funding, broaden resources for them … creating flyers and marketing materials and social media content. We’re going to send some of them to some Office classes so they can learn Excel and Word and so just really very basic capacity building. And then we’ve also been helping take residents to different conferences to speak so that they can share their story with other groups, which has been really powerful.

The same conservation program leader made clear the importance of coalition-building between organizations of shared values, but with different expertise, providing further improvements to social, economic, and political capacities that can benefit both housing and greening goals in communities:

… we are a conservation organization and there’s only so many of things we can tackle so we try to really bring a whole bunch of partners and others to the table so we can do what we specialize in and they can do what they specialize in and hopefully, you know, as a collaborative effort we get more results out of a smaller project … We obviously can get a lot more done when we partner together to get things accomplished where we all have our skills sets … When seven organizations say we need to look at something then we have a lot more visibility and attention for that request, both from the community and from our cities.

While missions and objectives may initially be different amongst these activist and nonprofit groups, the shared value of strengthening community infrastructure can provide a unifying strategy to achieve housing and greening equity.

Tools for children/youth engagement around inclusive greening

In many communities, families, children, and youth are major users of green and public spaces while also most vulnerable to gentrification and displacement from neighborhood green play spaces (Oscilowicz et al., Citation2020). As the incoming and inheriting generation of a community, children/youth and their social, economic, and political capacity are thus integral to sustaining attachment to physical space through healthy community infrastructure over the long-term in contexts of greening, gentrification, and displacement. Recognizing children’s and youth’s overlapping vulnerabilities, community groups in Atlanta, Cleveland, Philadelphia, Seattle, and San Francisco are engaging with children/youth and their families in order to assess their housing and greening needs while providing space for their own agency in the face of unequal neighborhood redevelopment. For example, a Black female leader in the San Francisco community greening group Friends of the Urban ForestFootnote6 describes that partnerships between residents and nonprofit organizations give agency to neighborhood youth. This agency offers them opportunity to self-learn, support their sense of place in greenspace and strengthen the direct connection to their neighborhood and its environmental assets and physical infrastructures, all of which lend to strengthening of social and political capacities:

[We give] youth options for what it is that they want to do in programming that day, giving youth an outlet in which they are facilitating, right? So we are like breaking away from this model of like … I’m the expert here, all of you are listening here doing what I’m telling you to do, right? So sharing and building up those leadership skills … They’re fundamental principles.

These values are further exemplified in child/youth engagement around neighborhood beautification projects as this approach also strengthens social capacity by increasing the longevity and acceptance of a project, (e.g., community gardening implemented through after-school environmental stewardship camps) while also extending this impact to parents, extended families, and even across generations. In Cleveland, a Black male Detroit Shoreway Neighborhood climate ambassador describes youth engagement through partnership-based after-school programs as a means to creating a sense of attachment to place for youth by providing opportunity to be part of the decision-making and stewardship components of park clean-up rather than “not getting ‘buy-in’ [if] somebody else is coming in and doing this for you rather than you having a stake in the land.” In sum, activists regularly engage children/youth as part of their overall strategy for partnered, multi-stakeholder community programming that aims to strengthen the social capacity of community infrastructure, thereby enhancing attachment to physical infrastructure and youth’s own agency. Activists also attempt to engage parents and older family members into place-based activism and stewardship.

Tools for community-oriented economic development and job empowerment around the green economy

As a complementary process to strengthening social capacity, many activists and nonprofit representatives we spoke with also explained the priority given to strengthening the economic capacity amongst residents who were engaging with activist programming. In Portland and Atlanta, civic groups and cooperatives are contracting out many on-the-the-ground jobs related to environment conservation (e.g., green space maintenance and trail building) and housing development (e.g., construction or landscaping) to local residents in order to provide them with financial support while also offering job training. In both places, these contracts often became full-time, long-term hires for residents who had completed all trainings and demonstrated commitment to the community. In Atlanta, a Black male nonprofit representative from The Conservation Fund describes the benefits of hiring for programming amongst partnered organizations from within the community, and how this also has had an impact on other residents’ sense of belonging, broader community building, and created a positive feedback loop for further community wealth creation:

It’s sort of a way not only to provide some skills and some job training for [activists] but then to help get the other members of the community invested as well. When they see ‘oh, these are people who live in our neighborhood who built this, not people we don‘t recognize’ and then [activists are] paid throughout that whole process and then hopefully at the end of that either the contractor will hire them. [The contractor has] said they’re willing to hire folks if they, you know, show that they’re willing to work.

Partnerships and coalitions are also critical in the development of community and residents’ economic capacity and construction of further community infrastructure to sustain this capacity in both neighborhoods of Atlanta and Portland. Networks of activists and cooperatives have formed and are taking control over broader hiring and job creation partnerships in the community. In Portland, the Living Cully networkFootnote7 partners with nonprofit housing developers and the social-enterprise landscaping and contracting company, Verde, for projects involving physical environmental and housing improvements with the aims to improve green space quality and address climate goals while combatting gentrification and displacement (see, also Enelow & Hesselgrave, Citation2015). Within these solidarity economy enterprises, local residents are offered training and work on climate resilient, affordable housing construction and landscaping, which contributes to both the social and economic capacity of community infrastructure. A white male representative of the 42nd AveFootnote8 Neighborhood Development Association explains the prioritization of community negotiative power, agency, and solidarity when working amongst a variety of organizations and entities as well as their vision for community-driven economic development—that is development from within: “We might work with an outside business, but we want to negotiate with them to ensure that their hiring practices or other things related to their economic function are very intentional in creating opportunity for community members.”

Community activists are also working to offer income stability to members of the community through grant-funded projects. In East Boston, the multi-lingual coalition network Solidarity Economic Initiative (SEI)Footnote9—consisting of seven philanthropic organizations including City Life/Vida Urbana, Eastie Farm, GreenRoots, and Solidarity—launched a Solidarity Fund to financially support community groups engaging in a socially just and environmentally just sustainable economy model.Footnote10 These grants have funded projects to support community economic capacity programs and workshops on solidarity economy and funding strategies to support immigrant-led worker cooperatives in East Boston. These groups provide collective power, mutual benefit, and environmental stewardship to promote community solidarity in East Boston. Here, a locally grounded model of economic development that supports economic capacity and in turn strengthens the community infrastructure allows for more just economic development models controlled by and born within local civic initiatives to support green neighborhood goals.

Strategy: Policy advocacy, education, and networking

Tools to demand equitable, affordable (green) housing rights

Activists demonstrated several approaches and action pathways in demanding equitable housing policy and advocating for tenants’ rights in neighborhoods undergoing dramatic changes to rental costs. Community members in Atlanta, Cleveland, Denver, San Francisco, and Portland each described strengthening political capacity through education of housing stakeholders (tenants, landlords, homeowners, private management) in order to develop context-specific, human-rights oriented, campaigns or education platforms for which housing stability and security are prioritized in landscapes where gentrification is related to greening. In Cleveland, the Legal Aid Society of ClevelandFootnote11 and the Housing Justice AllianceFootnote12 have partnered to offer an educational methodology aimed at preventing evictions by teaching solidarity- and dignity-driven communication strategies to mom-and-pop landlords as well as tenants as a means to improve housing security, reduce displacement, and increase the social and economic capacities in community infrastructure of both stable landlords and tenants. Here, a white male Cleveland landlord participating in landlord equity programming describes the coalition-produced program and how it has led to improved rental housing guidelines in other contexts:

If it’s a financial issue that’s causing [tenants] to fall behind, instead of pushing for eviction or to get the person out quickly to cut losses, that would be normal in the private market, we have sort of mediated with the tenant to figure out what is possible for them to pay or what they can do for repayment … It’s kind of an amalgam, a whole bunch of different strategies usually based on the principle that we should be able to, or we hope that we’re able to find a way to run this business in a way that preserves respect and dignity for tenants … [We aim to] create a sort of handbook [or] a model for equitable land-lording that we can then share and promote to others.

In Atlanta, a similar approach to empowering residents through anti-gentrification partnerships is provided for homeowners, particularly Black homeowners for whom homeownership provides generational security that was historically denied to them. These activists offer educational events to existing homeowners to build awareness of ongoing tax exemptions, subsidized home efficiency greening programs, homestead exemptions, and other tools which provide homeowners more opportunity for maintaining and feeling connected with their homes without fear of gentrification impacts such as property tax increases and displacement. Coalition building and partnership remain critical aspects of strengthening social and political capacities within community infrastructure through homeowner activism, as described here by a Black female housing activist in Atlanta:

We did a series of what we call homeowner empowerment workshops that help to connect [residents] and make sure residents knew about homestead exemptions … we had [also invited] partner organizations who help with home repair …

Overall, values of respect and dignity remain as core goals when prioritizing equitable housing, asserting tenants’ rights, and providing opportunity to enhance the material livability of homes through new green spaces or environmental efficiency. Activists are able to tackle a compounded, intersectional issue at the root, as opposed to seeking superficial or confrontational solutions to miscommunication, disagreement, and eventual displacement, thus enhancing social, economic, and political capacities of community infrastructure. Meanwhile, by building and supporting residents’ housing agency, leading to more prolonged periods without stress of displacement from their homes or leases, activists may mobilize these same residents to focus attention to other missions, such as improving greenspace, green amenity equity, and building greater political capacity around those goals and beyond them.

Tools for sharing successes

Opportunities for sharing, collaborating, discussion, and debate amongst residents and activists came up as cornerstones to improving programming, opening new creative channels for action, and strengthening political capacities within community infrastructure. Activists from communities we interviewed in Boston, Cleveland, Philadelphia, Portland, and Seattle each discussed how seeking knowledge, support, and advice from other activist groups outside of their context (be it municipality, region, state, or country) was an important component of continuing to build momentum within effective housing and environmental campaigns/programs. In Philadelphia, Green Building UnitedFootnote13—a nonprofit green building group which promotes low-cost, low-risk interventions for homeowners to improve the efficiency of their homes—found significant support and opportunity for widespread coalition building by facilitating a gathering of green building professionals. As a white female facilitating member of Green Building United shares, bringing together these professionals and experts from Pennsylvania and beyond provided opportunity to continue to develop policy and share creative, equity-driven alternatives to existing housing financing and construction practices, contributing to strengthening social, economic, and political capacity in community infrastructure:

What does it take to develop? What does it take to design? What does it take to implement? What sort of financing is available? What sort of financing is needed? What are the barriers? What is the actual performance of these buildings? … [These questions] developed into a conference and so we have anywhere from a dozen to 20 sessions, people coming from all over the world … sharing the lessons learned. So, they’re architects, they’re builders, they’re developers and they’re saying this is what I did, this is what I’ve seen, this is the data, how can we learn from each other … So we gather speakers, gather attendees and have these shared discussions about what it means to build affordably, equitably and in a way that’s also considering climate change.

Other activist groups also found success in organizing on themes around green buildings, tree-planting, community gardens, land trust finance schemes, and more amongst both activist residents as well as professionals. While residents may not be aware of exact terminologies when discussing the science of climate change or jargon related to housing development, activist groups and nonprofits have shared and leveraged their first-hand experiences and embodied community knowledge of what is occurring in neighborhoods as a result of climate change or displacement. As the same Philadelphia Green Building United activist describes, listening and sharing amongst activists is also an effective way to foster social capacity in community infrastructure: “The people who are impacted the most don’t necessarily know the vocabulary of resilience and climate change, but they do know what’s happening to their neighborhoods … .”

Valuing community lived experience and perceptions related to climate change, greening impacts, or housing insecurity and displacement at a grassroots level provides opportunity to bridge silos and propose creative solutions to both housing and environmental equity challenges amongst a variety of stakeholders and learning from residents and activists.

In the two cases—the first of more formalized networking facilitated by activists, the second more casual networking amongst neighbors—knowledge, successes, and failures are shared with the result of strengthening social and political capacities of residents to engage further with their local activist groups and benefit the overall community infrastructure.

Discussion

Our study, based on 250 interviews from 10 U.S. cities, investigated the strategies and tools used by neighborhood residents working in coalitions with civic groups, nonprofit housing developers, nonprofit conservation groups, and other major community stakeholders in the face of housing, community, and cultural displacement pressures resulting from (re)development of green amenities and real estate projects in previously underinvested or post-industrial neighborhoods. In our results, we identified how these strategies and tools utilized within coalitions were capable of strengthening social, economic, and political capacities within the community infrastructure of each neighborhood. We argue that each of the three capacities (social, economic, and political) must be built amongst residents in order to fortify the material and immaterial components of community infrastructure. We thus provide a unique analysis of recent activist strategies and tools through the lens of coalition building and their role in strengthening community infrastructures across gentrifying neighborhoods in the United States. These findings contribute to recent debates on activism strategies and practices for housing and green justice (Anguelovski & Connolly, Citation2021; Rigolon & Németh, Citation2018), broader processes of community mobilization (Alkon & Cadji, Citation2020; Anguelovski, Citation2014; Chaskin, Citation2001a; Pearsall & Anguelovski, Citation2016), and environmental justice in the context of greening (Anguelovski, Citation2016; Wolch et al., Citation2014).

Our approach was not comparative, but rather layered. The multiplicity of cases we analyzed allowed us to identify core trends in strategies, namely: affordable and accessible housing through participatory development; community programming, coordination, and facilitation; and policy advocacy, education, and networking. In addition, we found that tool 4.1.1 regarding alternative community-owned neighborhood housing was the most utilized tool within the selected studied cities. This is likely due to the immediate demand for affordable housing by residents across greening neighborhoods, as well as the multitude of developed financial mechanisms that have been tried, tested, and successfully utilized by communities and developers (Derickson et al., Citation2021; Oscilowicz et al., Citation2021). Other specific commonly used tools included: data science designed through citizen and specialist co-creation; environmental ownership and stewardship activities; economic asset building in the green economy; or education of housing stakeholders through a more compassionate approach. Our analytical approach also highlighted some unique cases and circumstances in coalition building, such as the case of West Dallas where two neighborhoods, one identifying as primary Latiné and the other primarily Black, were able to form a coalition that sought similar justice-oriented material and immaterial housing and greening.

Through this analysis, we have identified two major civic processes: (a) Multi-sectoral, dynamic coalitions provide opportunity to challenge top-down, government imposed glitzy, green urbanism () and (b) Those coalitions empower residents to reinforce community infrastructure, which itself is enabled by the strengthening of social, economic, and political capacities. In terms of the latter, we offer a novel definition of community infrastructure whereby long-term, durable social, economic, and political community capacities provide agency and power to processes of procedural justice needed in green gentrifying neighborhoods (), thereby positively strengthening both material and immaterial housing and greening equity (). These findings support the existing agency and visibility of community activists in accomplishing their goals.

Figure 3. Three types of community capacities that make up community infrastructure and resulting vision of just green urban futures.

Figure 4. Community infrastructure and its three capacity components provide the social, functional, emotional and spatial bonds necessary for physical infrastructures (e.g., community-developed and maintained affordable housing, community health centers, neighborhood sports fields, community food co-ops, etc.) to provide reinforced justice-centered immaterial green such as attachment to place, sense of community care, and sense of community ownership.

Defying glitzy, green resilience traps and greenwashing through coalitions

First, our analysis calls attention to the multiplicity, overlap, and combination of coalitions amongst activists and nonprofit groups that safeguard just greening, housing equity, and a fair community-centered economy while also starkly contrasting with the largely technocratic attempts for adaptation that many cities implement in low-income, vulnerable neighborhoods (Agyeman, Citation2013). We heard from activists that processes and attempts by local governments are largely short-sighted, siloed to only housing, siloed to only greening, and/or without proper discussion and consideration of historically marginalized residents’ needs. We find two major characteristics within the process of coalition building: who is an actor in the coalition as well as what is their expertise. We argue that coalitions consisting of multi-sector, multi-expertise organizations with complementary values and goals can better support communities in strengthening social, economic, and political capacities. These multi-sector, multi-expertise coalitions may derive from within multiple domains and expertises including but not limited to: housing stability, housing development, ecological resilience, just and equitable green spaces, political empowerment, community cohesion and place making, economic development and community wealth creation. Dynamic coalitions provide opportunity for a community to reclaim neighborhood urban transformations and utilize a community-born counter-narrative that defies top-down “resilience traps” or “greenwashing” (Angelo, Citation2019; Checker, Citation2011; Urson et al., Citation2022). The strategies and tools we analyzed provide methods by which dynamic coalitions might implement more equity-driven green (re)development plans (Anguelovski, Citation2015; Campbell-Arvai & Lindquist, Citation2021; Meenar et al., Citation2022).

Furthermore, this finding affirms that through strengthened community infrastructures, housing can indeed be “within the same business as park development.” This result contrasts with recent research that identifies boundaries and silos between nonprofit groups and finds that both groups are not part of the same “business” (Rigolon & Németh, Citation2018). We thus call for municipal action to be taken toward supporting dynamic multi-sector and -expertise coalitions through empathetic and social justice-oriented empowerment, and early on in greening projects. Moreover, provision of seed, grant, or program funding led and directed by community groups may be effective in ensuring just, sustainable, and equitable neighborhood outcomes (Anguelovski et al., Citation2020; Bolland & McCallum, Citation2002; Campbell et al., Citation2021; Connolly, Citation2019; Schnake-Mahl & Norman, Citation2017; Shandas & Messer, Citation2008).

Building community infrastructures for enacting neighborhood green justice

Our second key finding demonstrates that there is a relationship between strong community infrastructures and positive housing and greening equity (). What we see as strong social, political, and economic capacities provide residents and activists within communities the purpose, reasoning, and ability to identify, mobilize, and address enduring and emerging socio-ecological problems (Williamson et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, our analysis demonstrates that these three types of capacities make up the larger community infrastructure, of which can be further strengthened through coalition formation (Beckley et al., Citation2008). Additionally, we found the strengthening of one element of community infrastructure (i.e., economic capacity) may also amplify another element of community infrastructure (i.e., political capacity) in order to address major compounding challenges, such as lack of affordable housing or socio-cultural displacement from greenspace. We argue that a strengthened and solidified community infrastructure lays the foundation to generate the “city of heart’s desire” (Harvey, Citation2003) and protect residents against the multiple forms of displacement they may be experiencing in the green city. Realization of all three elements of community infrastructure can support both provision of physical space for affordable and accessible housing as well as their immaterial constructs, such as increased desire to participate in both social and political events as well as a strengthening sense of care amongst community, while also considering accessibility to and inclusivity of green space.

In strengthening community social capacity, we highlighted a novel aspect in housing activism: the unique, transformative potential of compassion, care, and empathy as an anti-displacement provision. As an ideal housing relationship framework that moves away from traditional models of paternalistic, aggressive landlording (Keller, Citation1987; Power & Gillon, Citation2022), some coalitions (made up of activists, tenants, homeowners/landlords, and nonprofits) seem focused on establishing a long-term social foundation of trust, respect, and security amongst all participating stakeholders. Those practices highlight the emerging need for a reimagining of relationships amongst housing stakeholders, made possible through the coalition model that prioritizes frameworks of empathy, compassion, feminism, emancipation, and decolonization (Anguelovski et al., Citation2020, Citation2021; Slater, Citation2004).

Meanwhile, strengthening economic capacity takes on multiple responsibilities and roles at different levels of individual and community income creation and for a variety of social classes in each neighborhood. We determine economic capacity can be accomplished through the provision of entry-level and more advanced training toward jobs for both adult and youth residents around the green economy that build educational and job opportunities and reduce wealth gaps amongst local residents. Economic capacity also consists in the creation of community-driven and -owned green cooperatives and social enterprises that can vertically integrate the financing, construction and maintenance of affordable green housing and inclusive green infrastructure.

In consolidating political capacity, we found there to be a symbiotic relationship between residents’ sense of place as well as physical and emotional belonging that endowed a renewed sense of ownership and empowerment in processes of reclaiming and advocating for neighborhood green space. Through reclamation and empowerment, residents, in turn, are emotionally, socially, and strategically equipped to mobilize and address compounding housing and greening riskscapes within their urban arenas (Shokry, Citation2021). This finding is also supported in European green gentrification literature, where investigation of strengthening political infrastructures through networking amongst citizen and worker activists allowed opportunity for alternative neighborhood visions that incorporated both social justice in housing as well as green infrastructures (Alexandrescu et al., Citation2021).

Finally, our analysis demonstrated the transformative justice potential of the immaterial outcomes of community infrastructure. We observed that when a combination of the three capacities of community infrastructure were strengthened, they would provide the necessary social, functional, emotional, and spatial bonds to generate justice-centered immaterial green outcomes. These outcomes include attachment to place, a sense of community care, sense of community ownership, sense of community trust, sense of identity, and other iterations that describe relationships amongst people and the environment.

Conclusion

While it may appear ironic to contest urban greening projects, recent research and shared lived experiences of residents in neighborhoods undergoing significant urban (re)development have demonstrated the “green is good” orthodoxy is impacting beyond mere access to local urban parks and into overall housing, health, and well-being of local residents. The experiences of activists in our studied cities may offer lessons for green gentrification activism across the United States, considering similar histories of racial and social injustice, and other countries, particularly in the Global North. Identifying these similar threads of strategies and tools utilized in the face of green gentrification provides support and structure for mobilized groups to learn from one another’s successes and failures, and bring a sense of community, partnership, and strength to larger national networks. Our discussion presents a novel perspective on the relationship between community infrastructures and activist coalition building and provides research support for future activist mobilization analysis in the context of green gentrification.