ABSTRACT

Municipal rainbowization has proliferated globally in tandem with LGBTQ+ equalities gains. The rainbow—a globalized aesthetic of an imagined community that symbolizes LGBTQ+ empowerment, belonging, and safety—is increasingly integrated into municipal infrastructure as a neoliberal place-branding tool of social inclusion and performative progressiveness. On urban peripheries, the rainbowization of infrastructure embeds LGBTQ+ imaginaries in heteronormative suburbia, simultaneously evoking rainbow infrastruggles—morality-led conflicts over questions of representational excess and legitimacy. In the absence of queer infrastructure on the Vancouver city-region periphery, this paper examines how municipal rainbowization generates infrastruggle through bureaucratic processes that perform progressiveness by aestheticizing LGBTQ2S social inclusion in generic crosswalks, city hall plaza lighting, and flagpoles. It argues that as a metaphoric policy intervention, such rainbow aestheticization performs surplus visibility as progressiveness and confines LGBTQ+ issues to the symbolic realm. To compensate for inaction on more substantive LGBTQ+ social inclusion, municipal rainbowization is a rhetorical move in which queer bodies are absented in a quest for political absolution that maintains citywide heteroneutrality. The neologism infrastruggle contributes an understanding of infrastructure as a buried site of heteronormative political assumptions and a way of seeing the inconspicuous infrapolitics of a subordinated group in the public realm.

Introduction

In the contemporary “infrastructural moment” (Amin, Citation2014), cities and their technological and aesthetic materiality remain sites of struggle over “the exercising of social and political power” (Graham, Citation2002, p. 175)—what this paper terms infrastruggle. Given the significant material and economic investments in the built environment’s technical systems and their contributions to the distribution of urban resources and public goods, infrastructure is a site of political claims-making wherein social inequities can be both reinforced and contested (Datta & Ahmed, Citation2020; Siemiatycki et al., Citation2020). By reflecting and materializing power dynamics, infrastructure undergirds social action, making it a venue for political engagement and opening it up for negotiation, disobedience, and contestation (Kleinman, Citation2014; Sizek, Citation2021). This paper uses the term infrastruggle to not only reinforce the contentiousness of infrastructural claims, particularly for minoritized groups, but also to convey their subterranean “infrapolitical” dimensions. Infrapolitics is a domain that “encompasses the acts, gestures, and thoughts that are not quite political enough to be perceived as such” in form or content (Marche, Citation2012, p. 3). As Scott (Citation1990, p. 183) asserts, infrapolitics resides in the “unobtrusive realm of political struggle” involving practices of resistance that lie beneath the threshold of politics yet remain elemental to the dissent of minority and marginalized cultures (c.f. Marche, Citation2012). For the purposes of this paper, infrastruggle, then, contributes a twofold understanding of infrastructure as both a buried site of heteronormative political assumptions and a way of seeing the inconspicuous infrapolitics of a subordinated group in the public realm.

For sexual and gender minorities in the urban West, infrastruggles have been grounded in a quest for central-city visibility. As both a tactic and a goal of liberal gay identity politics, increased visibility works within and against dominant cultural formations offering an opportunity to be seen and heard in public fora to “gain greater social, political, cultural or economic legitimacy, power authority, or access to resources” (Brouwer, Citation1998, p. 118). Gay village territories have been formally demarcated through property ownership, anchor institutions, and commemorations with rainbow motifs that convey the networked presence of urban sexual subcultures and a sense of LGBTQ+Footnote1 permanence in the urban landscape (Ghaziani, Citation2014). Furthermore, LGBTQ+ urban histories are grounded in clandestine appropriations of municipal infrastructure (e.g., parks, public restrooms, and bathhouses) and the navigation of municipal licensing regimes governing urban entertainment venues (e.g., bars, cabarets, and taverns; Chauncey, Citation1994). Indeed, Campkin (Citation2021, p. 97) refers to such networks and their nodes of commercial-night venues as “queer infrastructure,” a means to serve multiple LGBTQ+ groups by transporting resources and enabling “heterogeneous forms of sociality” despite the “issues of uneven provision and access to space” arising across intersectional differences. Queer infrastructure can also be a powerful metaphorical policy tool because it turns the respective group into a “named minority” with “protected characteristics and identities,” mobilizes designations of their spaces as their property, and activates “planning instruments designed to designate community value and protect heritage” (Campkin, Citation2021, p. 82). Rainbowization is often a key policy tool adopted to enhance LGBTQ+ visibility, leveraging the rainbow motif to “stand in as a geographical expression of … gay and lesbian identity” (Papadopoulos, Citation2005, pp. 233–234). Nevertheless, rainbowization also becomes expediently enfolded in municipal neoliberal competitive place-branding strategies to convey a willingness to recognize LGBTQ+ contributions to cosmopolitan diversity while simultaneously signaling the ethnicization and homonormalization of sexual identities as “pliable categories” (Papadopoulos, Citation2005, p. 234). Moreover, it is a governance tactic that reinforces LGBTQ+ metronormativities by containing LGBTQ+ celebratory spaces in the central city (Knopp, Citation1995).

The contemporary centrifugal dispersal of sexual and gender minority communities across city-regions poses a challenge for LGBTQ+ visibility politics (Bain & Podmore, Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2021a). As queer metropolitan community life in North American cities shifts “from historic inner-city enclaves … to outer neighbourhoods and municipalities with more affordable housing and rapid growth in jobs” there are “few services for LGBT populations” creating “a reversal of a century of sexual minority concentration” (Brochu-Ingram, Citation2015, p. 228). Although this dispersal is accompanied by many rights and protections, the suburbs to which gender and sexual minorities migrate were built as places to reproduce familial heterosexuality and therefore lack historic queer infrastructure and thus the socio-spatial resources to support the thriving of LGBTQ+ populations (Bain & Podmore, Citation2021a, Citation2021c; Podmore & Bain, Citation2020, Citation2021). Differential local governance pressures stemming from the mainstreaming of national equalities legislation and the decentralization of LGBTQ+ households and community organizations has led to increased LGBTQ+ suburban activism. Such activism places the onus on peripheral municipalities to provide queer infrastructure where none existed before rather than simply virtue signaling allyship by “performing progressiveness” (Ghaziani, Citation2014) through the excesses of rainbow visibility (Bain & Podmore, Citation2021a). Originally representing gay rights and community solidarity in opposition to heternormativity, the banal malleability and pretty colors of the rainbow offer municipalities a degree of absolution for political inaction by permitting a disassociation between its aestheticization and the messiness of LGBTQ+ bodies (Brodyn & Ghaziani, Citation2018). Rainbowizing municipal infrastructure (e.g., crosswalks, street signs and banners, benches, garbage bins, stairs and ramps to storefronts, lamp posts, planter boxes, utility boxes and newspaper kiosks) signals LGBTQ+ inclusion (Bitterman, Citation2021), but it also permits a “blissful but non-malicious ignorance about sexual inequality” and the coexistence of liberal positions on sexuality with conservative “homonegative” place-based behaviors within one municipality (Ghaziani, Citation2014, p. 255). Infrastruggle emerges in the tensions between the “surplus visibility” (Patai, Citation1992) that challenges heteronormative expectations of LGBTQ+ silence and invisibility and the potential of the rainbow to reconcile different local political positions by generating “legitimacy-without-controversy” (Berg, Citation2011, p. 21).

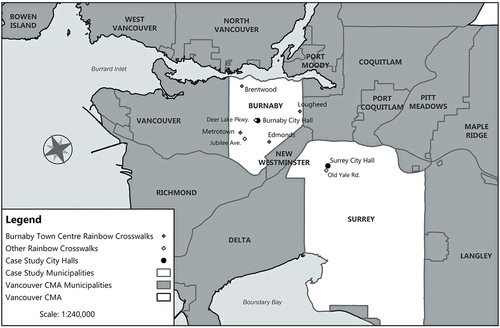

The objective of this paper is to show how municipal rainbowization and its surplus visibility in the absence of historic queer infrastructure becomes infrastruggle on city-region peripheries through bureaucratic processes of generic social inclusion. It draws on field research from two neighboring peripheral municipalities in the Vancouver city-region, Burnaby and Surrey (), to demonstrate the twofold limitations of rainbow aestheticization as a metaphoric policy intervention. First, rainbow aestheticization performs surplus visibility as progressiveness, standing in for more substantive LGBTQ+ social inclusion policy and the production of suburban queer infrastructure. Second, rainbow aestheticization confines LGBTQ+ issues to the symbolic realm, disembodying the rainbow from the lives of queer citizens. To develop this argument, the following literature review brings a queer sensibility to established notions of aestheticization and infrastructure. It demonstrates how the neologism of infrastruggle reveals the heteronormativity of municipal infrastructure while simultaneously serving as metaphorical policy tool to insert sexual and gender minorities into municipal discourses of social inclusion. The research methods section operationalizes infrastruggle, providing details on case study selection, data collection, and data analysis techniques. The empirics focus on three examples of suburban infrastruggle (rainbow crosswalks, pride flags, and civic plaza lighting) in order to examine how the rainbow aestheticization of municipal infrastructure is part of a performance of progressiveness. It concludes by asserting that the rainbowization of infrastructure standardizes and reproduces a globally recognizable symbol of LGBTQ2S “liberation” but, ultimately, its transformative potential is limited, offering little in the way of an alternative queer suburban future.

Municipal infrastructure and suburban rainbow aestheticization

Infrastructure—its provision (e.g., roads, sewers, water, transit, schools, and airports), use, and accessibility—is central to suburban studies scholarship (c.f., Addie, Citation2016; Young & Keil, Citation2011). Suburban civic investment in infrastructural renewal and expansion has facilitated the universalized movement of people and goods and generic service provision, raising urban planning and governance challenges (in terms of funding, management, maintenance, efficiency, and environmental sustainability), often to the neglect of social considerations of equity and inclusion (Young & Keil, Citation2011). Most suburban infrastructural planning prioritizes questions of mobility to maximize “the connection of prime network spaces in the downtowns to major transportation and communication hubs in the region” (Keil & Young, Citation2011, p. 9). The ensuing disconnections under-serve suburbs, exacerbating gendered and sexual minority “structural and systemic violence in which politicians, the media, publicity and institutions are complicit” (Hancock et al., Citation2018, p. 25), but their infrapolitics are under-examined. Keil and Young (Citation2011, p. 13), therefore, rightly underscore that suburban infrastructure “fails many people most of the time and some people sometimes” but they do not examine the infrastruggles that emerge in relation to this failure. Instead, political economy suburban studies scholars continue to emphasize the “hard” (technical, material, and digital) dimensions of infrastructural imbalances to the neglect of softer “social arrangements,” “everyday rituals,” and aesthetics that “condition the capacities of people in places” and produce conflict (Addie, Citation2016, p. 274). Furthermore, this lack of municipally-provided “social infrastructure” (Klinenberg, Citation2018) means racialized, gendered, and class-based infrastruggles continue to be a by-product of this civic neglect (Carpio et al., Citation2011). Out of necessity, the “subaltern cosmopolitan citizenry” of today’s suburbs respond by adaptively re-using discarded brownfields, dead malls, vacant industrial warehouses, and strip mall storefronts as spaces for worship, community building, and “integrative multiplicity” (Basu & Fiedler, Citation2017, p. 25).

At its most basic, infrastructure is a material manifestation of universalized cultural norms (Gandy, Citation2011), giving physical form to the common needs of citizens that skew toward the interests of the majority. Given its underlying centrality to everyday life, to belong to a culture involves a degree of infrastructural fluency in the recognition of its use and access (Edwards, Citation2003). Built into infrastructure’s production are assumptions about who will use it and how, but this “obduracy” of “infrastructural settlement” can also be challenged through inhabitation (Latham & Wood, Citation2015). Urban infrastructure, then, can be understood as a cultural product of urban lives that is contingent upon infrastruggles to materialize different and competing urban imaginaries. Political conflicts over the urban iconography of infrastructure “necessarily bring questions of aesthetics and cultural representation into our analytical frame” (Gandy, Citation2011, p. 63). For example, in contemporary postcolonial urban theory, physical infrastructural systems and their aesthetics are theorized as reproducing settler narratives that turn cities into sites of precarious inhabitation for marginalized social groups. The embodied spatial claims of “people as infrastructure” (Wilson & Jonas, Citation2021), are often discounted by the state unless “they are manifested in behaviours that can be measured, subjected to the probabilities of specific outcomes, and ally with political and economic projects that seek to define and mobilize them” (Simone, Citation2021, p. 1344). As such, the marginalized must fend for themselves in the cracks and discards of the mainstream, building and adapting infrastructure to meet their own needs. Extending this postcolonial critique, the monolith of infrastructure and its heteronormative assumptions about the universal subject can be confronted by a queer aesthetic (Walters, Citation1996), interrupting “indurated conventions long enough for strange or queer ways of being, acting and knowing to be imagined” (Isherwood, Citation2020, p. 232).

From the crevices of central city entertainment districts, sexual and gender minorities, for example, have built what Campkin (Citation2021, p. 97) refers to as “queer infrastructure” through disparate nodes that form networks of commercial-night venues. Queer infrastructure has not only helped to build LGBTQ+ community, but more recently, in the face of growing LGBTQ+ equalities legislation and the marketized diversity regimes of urban neoliberalism, this queer infrastructure has concomitantly become vulnerable to economic displacement and homonormalization. Nevertheless, such a venue- and central-city-oriented infrastructural analysis depends upon already existing densities of LGBTQ+ sites and privileges the historic placemaking of cis-gendered, middle-class, gay men. A huge swath of LGBTQ+ life exists outside of central city service densities, requiring “a shift in conversations around sexual minority vulnerability, needs, and entitlements from earlier activist challenges to inequities (and subsequent constructions of rights and protections), to building expanded and truly inclusive social spaces, entertainment establishments, service programs, and facilities” in the suburbs (Brochu-Ingram, Citation2015, pp. 227–228). A more responsive and expansive understanding of queer infrastructure, Brochu-Ingram (Citation2015, p. 228) argues, treats it as the sum of “protections, organizations, social spaces, and service programs for overcoming homophobia and transphobia, along with intersecting inequities rooted in misogyny, racism, neocolonialism, cultural chauvinism, and anti-migrant xenophobia.” Such a queer “infrastructuring” perspective is larger than the LGBTQ+ community (Korn et al., Citation2019). It invites municipalities and their multiple publics to engage in a more reparative and redistributive approach to all of the city-region’s infrastructure, appreciating that it is never static and involves constant readjustment to ensure socio-spatial intersectional inclusions. While in the central city, the quantification of preexisting queer infrastructure as a “policy metaphor” can render it more legible and protectable within the urban planning and policy frameworks of governance (Campkin, Citation2021), in suburban areas without a density of queer public life, aestheticization through civic infrastructural transformation predominates.

When governments aestheticize public infrastructure to promote diversity on behalf of minoritized groups using representative iconography or programming, there is always the potential for infrastruggle because these civic practices of inclusion appear as preferential treatment. The infrastructural practices of municipalities can be mobilized to celebrate minority inclusion (e.g., postering, awareness campaigns, public art, flag raisings, plaza lighting, proclamations, commemorative displays, toponymy and eponomy, festival calendars, and lamp standard banners), but when minoritized groups are centered in common public infrastructure, what looks like recognition shifts toward overrepresentation in the mainstream public imagination, what researchers have called “surplus visibility” (Patai, Citation1992). Strategically used by “traditionally powerless and marginalized groups to challenge the expectation that they should be invisible and silent,” surplus visibility makes use of a minority group’s already-existent hyper-visibility to subvert the notion that “any space that minorities occupy appears excessive and the voices they raise sound loud and offensive” (Patai, Citation1992, p. 35). The municipal generation of LGBTQ+ surplus visibility, therefore, involves the aestheticization of the public realm in unexpectedly colorful, graphic, and iconographic ways to challenge social exclusion. It generates what appears as a surfeit presence to those privileged by a “simple” (DePalma & Atkinson, Citation2009) status quo postionality (often able-bodied, cis-male, non-racialized, heterosexuals) with access to public spaces, political networks, and commercialization (Muller Myrdahl, Citation2011). This presence is deemed excessive precisely because it is not adequately contained and raises civic questions about who has visual legitimacy in the built environment. As a political strategy, however, hypervisibility is often “a necessary intermediate step between invisibility and simple visibility” as minority groups are “talked into a state of ordinariness” (DePalma & Atkinson, Citation2009, p. 884).

Sexual and gender minorities, in particular, have developed a politics of visibility that depends on the aestheticization of infrastructures as inclusion, specifically the rainbowization of municipal crosswalks, flagpoles, and plazas (Hauksson-Tresch, Citation2021). Designed a half-century ago by artist Gilbert Baker for San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk, the rainbow flag was an empowering political symbol to counter heteronormativity and, in the 1990s, became an alternative to the reclaimed Nazi-era pink triangle (Bitterman, Citation2021). The rainbow encapsulates a politics of hope, with each color representing different LGBTQ+ life-affirming elements (e.g., red is life, orange is healing, yellow is the sun, green is nature, turquoise is art, royal blue is harmony, and purple is spirit; Bitterman, Citation2021). When displayed in homes, businesses, and institutions, the rainbow is a boundary object and a visual code for LGBTQ+-friendly spaces of safety, welcome, and belonging (Alm & Martinsson, Citation2016). The rainbow’s aesthetic became internationalized with the diffusion of Pride parades and festivals (Binnie, Citation2004), representing a transnational imagined community while simultaneously signifying “(neoliberal) tolerance and diversity aimed at inviting and producing as many consumer subjectivities as possible” (Klapeer & Laskar, Citation2018, p. 528). Thus, the rainbow brand is critiqued by some radical queer groups as homonationalist because it symbolizes “a new sexual neo/colonialism” and “gay imperialism” (Klapeer & Laskar, Citation2018, p. 530).

Municipal rainbowization aesthetically draws on global imagery to represent sexual and gender minority “liberation” by transforming (if only temporarily) local municipal infrastructure in the name of “progressive” inclusion. While seemingly banal and celebratory, this domain of aesthetics, particularly the “aesthetic-visual,” is inherently political because it is a crucial tool of power that conditions who and what is seen (Speer, Citation2019). There is, Brighenti (Citation2010, p. 33) argues, “no visible without modes of seeing.” It is in these modes of seeing that the power dynamics of infrastruggle are established, permitting civic leaders to include (or not) minoritized populations in the state’s field of vision. However, rainbow aesthetics may conceal as much as they represent. While aesthetics carry the capacity to bring marginalized social identities into being (Jacobs, Citation1998), they are only a superficial acknowledgment that leads to “an anaesthetization of reception, a viewing of the ‘scene’ with disinterested pleasure” (Buck-Morss, Citation1992, p. 38). For example, within gentrifying inner-city areas, such anaesthetization is enabled through the capitalist aesthetics of urban revitalization that orders and controls bodies through strategic beautification, adopting a symbolic language that reshapes how cities are envisioned for middle-class consumption, and experienced as sites of aggressive displacement for marginalized communities (Speer, Citation2019). As part of central city “revitalization” processes, Summers (Citation2019, p. 3) documents how the emplacement of Black aesthetics (e.g., in gentrification, heritage tourism, product marketing, and place branding) serves as “a mode of representing blackness in urban capitalist simulacra, which exposes how blackness accrues value that is not necessarily extended to black bodies.” As municipalities rebrand themselves as “diverse” by appropriating the unstable aesthetic codes of “the Other,” they strategically foster a disassociation from the lived “messiness” of marginalized queer bodies (Manalansan, Citation2015).

As an aesthetic code, the rainbow motif is a temporally and spatially variable resource that can be civically deployed to signal social inclusion, but it does not have the power to eliminate the “problems and deficits of those labelled ‘excluded’” (Cameron, Citation2007, p. 397). Within any system of social power that is fractured along an inclusion/exclusion binary, distinctions between “those who represent a particular kind of threat to social harmony” from those who do not are distorted by the “mess” of difference and the “excesses” of surplus visibility (Allman, Citation2013, p. 7). Instead, social inclusion policies that are derived from a “moral obligation … borne out of an appreciation of human equality” (Boyd, Citation2006, p. 875) are replaced by a seductive rainbow aesthetic that merely symbolically and temporarily expands normative boundaries. Thus, municipalities are driven by urban neoliberal entrepreneurial and cosmopolitan ideals to emphasize the commodification of “difference” as civic place-brand to the neglect of “community needs and problems” (Paganoni, Citation2012, p. 15). Such a performance of progressiveness is further overdetermined by the banal malleability, ubiquity, and vividness of the rainbow in the absence of political demonstrations.

In their study of Chicago, Brodyn and Ghaziani (Citation2018) present a fourfold typology of the performances of progressiveness by heterosexual gayborhood residents that includes: spatial entitlement; rhetorical moves; political absolution; and affect. Their concept of performative progressiveness is intended to capture the ambivalence arising from progressive attitudes that exist alongside homonegative actions producing “conflicting visions of place” (Brodyn & Ghaziani, Citation2018, p. 310). It focuses on “straights who say they are open-minded about homosexuality but whose behavior betrays a sexual ethnocentrism, or heterocentrism” meaning that they “are not overtly homophobic” but nor “are they marching in the streets for gay rights” (Brodyn & Ghaziani, Citation2018, p. 310). Having built a typology of individual dispositions, they find that positive attributes associated with LGBTQ+ individuals do not always scale up to progressive and politicized attitudes toward the group as a whole. Within the confines of the present analysis, two of these attitudes can be applied to municipal governance and are relevant beyond the gayborhood to more peripheral places. While spatial entitlement (the heterosexual privilege of access to queer spaces and commodities) and affect (the disbelief in LGBTQ+ desires to have their own spaces) are more clearly a product of inhabiting gayborhoods, rhetorical moves and political absolution are more discursive and can be adopted by suburban political actors. Rhetorical moves are homonormalizing in that they celebrate equality gains as long as gays and lesbians “adopt heteronormative ideals” (e.g., relationship monogamy, marriage, and children; Brodyn & Ghaziani, Citation2018, p. 317). Political absolution emphasizes place-based and individualized solidarities rather than larger networked alliances that bring about minority group equities, perpetuating “political avoidance and apathy” along with “a nonchalant attitude about social inequality” (Brodyn & Ghaziani, Citation2018, p. 317). Rhetorical moves and political absolution are both dynamics at play in the suburbs of Canadian cities where rainbowization in infrastructure is the predominant progressive performance of LGBTQ+ social inclusion. In the search for some political absolution for a lack of LGBTQ+-specific social agenda, suburban municipalities leverage the metaphorical and rhetorical policy possibilities of the rainbow to reinforce the local state’s heteroneutrality.

When appreciated through the lens of municipal rainbowization, infrastructure is imbricated in infrastruggle’s subordinated infrapolitics and mode of seeing, resulting in surplus visibility that ultimately fails to adequately address LGBTQ+ bodies and resource needs. In the absence of queer suburban infrastructure, municipal rainbowization initiatives are the predominant, yet limited, tools of LGBTQ+ social inclusion. A malleable and unifying symbol of diversity for hetero-publics that also signifies safety and welcome for some sexual and gender minorities, the rainbow and its colorful aestheticization in suburban infrastructure provides municipalities with sufficient distance from queer embodiment to anaesthetize its message of inclusion. Using the neologism infrastruggle, the paper invites urban scholars to appreciate the contested character of seemingly banal suburban municipal rainbowization projects that demonstrate the power of infrastructure to perpetuate suburbia’s heternormativities.

Research methods

To illustrate the suburban infrastruggles deriving from rainbowization, this paper draws on a larger research program about suburban LGBTQ2S-placemaking processes in Canada’s largest cities (see, Bain, Citation2022; Bain & Podmore, Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2021a, Citation2021c; Bain et al., Citation2020; Podmore & Bain, Citation2019). It focuses on two peripheral Vancouver city-regional case studies, Burnaby and Surrey. These municipalities were chosen because of their frequency in the project’s newspaper database of LGBTQ2S suburban representation (n = 741 of which 209 or 28% were for Burnaby and 270 or 36% were Surrey) and confirmed by census data on the concentration of same-sex households (16% in Burnaby and 18% in Surrey; Statistics Canada, Citation2017). Fieldwork interviews (n = 98) revealed densities of LGBTQ2S political organizing that resulted in a discrete set of identifiable infrastruggles captured in the project’s municipal policy database (n = 170). Burnaby and Surrey both have significant levels of media coverage, high relative densities of same-sex residents, and material evidence of municipal LGBTQ2S inclusions and suburban community activism in their policy records (Bain & Podmore, Citation2021b, Citation2022).

This paper integrates key informant interviews with ethnographic fieldwork (site visits and event attendance) and policy database analysis in an effort to triangulate mixed methods data on rainbowization and its contribution to suburban infrastruggles in the case study municipalities. Much queer scholarship in the humanities and social sciences requires critical reconsideration of social scientific data collection methods since queers are often pathologized in archives and invisibilized in public spaces, generating data sets that are often too small to be generalizable (Ghaziani & Brim, Citation2019). Within cultural studies, Halberstam (Citation1998, p. 13) has, therefore, proposed a “scavenger methodology” which “uses different methods to collect and produce information on subjects who have been deliberately or accidentally excluded from traditional studies of human behavior” and synthesizes “methods that are often cast as being at odds with one another” and refuses “the academic compulsion toward disciplinary coherence.” The current project, then, makes use of scavenging to amass what ultimately became nodes of quite conventional data around a few infrastructural case studies. At the intersection of the field observations, interviews, and policy documents, three specific examples of the suburban rainbowization of municipal infrastructure emerged, becoming the focus of this paper: crosswalks, flagpoles, and lighting. Since these were the data set’s only coherent examples of suburban LGBTQ2S infrastruggle across all sources, selection bias in the choice of case study material or any potential exclusions of negative evidence were eliminated. Given that the paper addresses the inclusion of a vulnerable category of people, it adopts a more inductive approach to “engaged urbanism” that recognizes that “each urban phenomenon may need its own methodological toolbox” (Campkin & Duijzings, Citation2016, p. 3). This paper’s methodology, therefore, seeks to respond to the changing realities of contemporary suburban life by working with the “intuitive, in situ and ‘trial-and-error’ processes” that emerge from highly localized municipal examples of attempts to engage (or not) suburban LGBTQ+ constituencies through infrastructural transformations (Campkin & Duijzings, Citation2016, p. 1).

The three modes of data collection were undertaken in the summer months between 2017 and 2019. The researchers, both of whom are queer-identified, participated in a range of community activities and events (e.g., LGBTQ2S seniors’ dances, movie and pub nights, drag shows, bingo fundraisers, monarchist ceremonies, poetry readings, pecha kuchas, protests, Pride festivals and marches, and flag raisings) and did onsite visits to each municipality’s queered infrastructure. The fieldwork also involved nearly 100 semi-structured, informational interviews with key informants (municipal politicians and urban planners, municipal and community service providers, and local activists) to trace the struggles associated with queering suburban infrastructure and policy. Municipal politicians, staff, and urban planners described social inclusion policies, governance priorities, infrastructural investments, and local LGBTQ2S initiatives. Service providers and activists detailed organizational involvement in infrastruggles, describing interventions as well as collaborations. Sections of these recorded interviews were selectively transcribed based on the thematic coding of detailed hand-written interview notes that indicated where and when infrastructural discussions emerged. Finally, a LGBTQ2S social inclusion policy database of civic records from 1995 to 2020 (composed of meeting minutes, departmental reports, plans, and policies) was compiled from public-facing documents posted on the case study municipal websites that contained LGBTQ2S-related keywords. In the iterative analytical movement between coding field notes, selecting relevant portions of the interview transcripts, and the gathering of civic records, infrastructure was solidified as a thematic that was repeatedly challenged, therefore, requiring the neologism of infrastruggle to overtly capture this contestation.

Within social scientific methods, research seeks to analyze the relationships between independent and dependent variables to infer causation (Babbie, Citation2020). In conventional methodological terms, the research targeted the relationship between requests for rainbowization that required a municipal response through infrastructural change (independent variable) and the extent to which infrastruggles over the legitimacy of LGBTQ+ surplus visibility ensued (dependent variable). In the LGBTQ2S social inclusion policy database, the case study municipalities were dealt with discretely, their public-facing documents ordered according to year, initiative, and governance actor (politicians, municipal representatives, service providers, para-public agents, community groups, and activists). The analysis classified forms of LGBTQ2S political actions (awards, delegations, funding requests, information, infrastructure, presentations, proclamations, requests, reports, and updates) and outcomes (adopted, recommended, denied, funded, not funded, motions, received, and referred). situates infrastructure relative to nine other governance actions.Footnote2 Quantitatively, the proportion of infrastructural actions (e.g., council, committee, and departmental discussions of LGBTQ2S issues in relation to municipal infrastructure) were variable: 22% in Burnaby, representing the second largest category; and 2% in Surrey, representing the second smallest category. Qualitative analysis, however, brings forward the political struggles over infrastructural actions, rendering them infrastruggle when contextualized within the micro-infrapolitics of everyday governance. A number of infrastructural concerns were separately raised in select interviews, field notes, and the policy database (e.g., retrofitting and access to universal changing rooms and restrooms in public facilities, and inadequate LGBTQ+-specific community social space), however, most were referenced as fragmentary and piecemeal instances. Only the three selected case studies (crosswalks, flagpoles, and plaza lighting) were sufficiently triangulated to permit analysis across all data sources. In the empirical discussion that follows, these three LGBTQ2S infrastruggles demonstrate how the performatively progressive rainbow aestheticization of municipal infrastructure is contested when it spills out into highly visible public spaces. As universalizing as the rainbow aesthetic appears on the surface, it hides micro-political struggles over where surplus visibility in the infrastructure of suburban municipalities is permitted and for whom.

Rainbow infrastruggles in Burnaby and Surrey, British Columbia

This section considers how two adjacent peripheral municipalities in the Vancouver city-region infrastructurally aestheticize the rainbow to foster LGBTQ2S social inclusion. Burnaby, an older inner-suburb with a diverse immigrant and working-class population, has struggled over LGBTQ2S inclusion since the 2011 adoption of its schoolboard’s Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (SOGI) policy which intensified its reputation for homonegative politics in public discourse. Municipal governance priorities shifted in 2018 with pressure from “insider activists” (from the departments of planning and parks and recreation, libraries and some para-public agencies) to launch Burnaby’s first Pride celebrations (Browne & Bakshi, Citation2013). Across the Fraser River, Surrey, a large and growing outer suburb in the “Bible Belt,” exemplifies a different form of rainbow infrastructural aestheticization in its flag protocol and civic plaza lighting. Surrey has experienced two decades of rainbow infrastruggle against homonegative politics by community activists and more recently by an openly-lesbian city councilor. Both peripheral municipalities exemplify highly localized rainbow infrastruggles across different infrastructural mediums (road surface treatments for crosswalks, fabric flags and steel poles, and ephemeral artificial lighting).

Queering the pedestrian: Burnaby’s rainbow crosswalks

In the multiple-threat scenarios of mixed traffic roadway systems, crosswalks (pedestrian or zebra crossings) infrastructurally ensure walking safety by visually marking pedestrian right-of-ways with universal design, lighting, and traffic signalization. Yet, different governance values are incorporated into crosswalk design, recognizing pedestrian variability in gait, speed, and reaction, and how land uses shape pedestrian safety and flow. As Loukaitou-Sideris et al. (Citation2007, p. 349) note, “[c]rosswalks should be designed taking into consideration the age and other characteristics of pedestrians and should be avoided at intersections with high traffic speeds, poor illumination, and insufficient visibility for drivers.” Autocentric suburban landscapes make crosswalks a crucial, yet banal, infrastructure of pedestrian accessibility, often used without regard for their cultural symbolism.

Over the last decade, however, crosswalks have become increasingly aestheticized. Rainbow crosswalks, for example, have proliferated as visible, permanent, and replicable markers of LGBTQ+ inclusion in the landscape (Bain & Podmore, Citation2022). Varying in their patterning and placement (often in the downtown core or at symbolic intersections), rainbow crosswalks are usually painted in the eight colors of the original Pride flag as a “symbolic gesture of an inclusive community or an illustration of a wider embrace of social diversity” (Muller Myrdahl, Citation2021, p. 50). While walking on a flag is considered to be a desecration and violation of protocol, walking on the rainbow crosswalk is intentionally invited. Due to their surplus visibility, rainbow crosswalks are further subject to civic debate and even homophobic vandalism, producing municipal infrastruggle. While rainbow crosswalks politically “surface” issues of representational equity, for transportation engineers (concerned with paint technology, durability, legibility, and location), the priority is ultimately pedestrian safety. For conservative critics, however, concerns about whether rainbow colors improve or impair pedestrian safety masks localized homonegative reactions.

The Vancouver city-region’s first rainbow crosswalks were painted downtown in 2013 in Davie Village with peripheral municipalities following suit (e.g., New Westminster in 2015 and Burnaby and Surrey in 2018; Wells, Citation2018). For Burnaby, rainbow crosswalks became compensation for its late emergence of LGBTQ2S support, rapidly generating “surplus visibility” by installing them at high-profile intersections between 2018 and 2020 (Bain & Podmore, Citation2020b). As an “interim measure,” the first crosswalk was painted in 2018 on a “redundant street” with low traffic volume to inaugurate the city’s initial Pride event (Social Planner, interview, 9 July 2019). Temporary and rushed, it was installed 3 days before Pride. With no budget nor available road crews, the social planner and Engineering Department staff painted the crosswalk with deck paint in four hours. Its location on Jubilee Avenue was both practical and symbolic: fronting municipal youth and recreation centers (that were key to Pride organizing); and a local road with minimal traffic to create wear. Hours after its installation, it was vandalized with a spray-painted green question mark inside a silhouette resembling the municipality. After it was repainted, 24-hour security prevented further homophobic vandalism. At its inauguration during Pride, the mayor in the company of Indigenous elders and political dignitaries interpreted the crosswalk in metaphorical policy terms as a bridge across multicultural differences (): “In this city, we believe that it is essential for all of us to cross the bridge of our differences … in a community with over a 100 languages, that brings people together from all over the world, this diversity is our strength and this crosswalk is an important statement that all of us believe in each other” (Field Notes, 11 August 2018). This road infrastructure manifested more than its materiality: it was activated by para-public networks, deft political maneuvering, and institutional and civic departmental allyship, exemplifying aestheticized suburban infrastruggles over diversity, inclusion, and representation.

The second most ethno-culturally diverse peripheral municipality in the Vancouver city-region, Burnaby filtered its use of the rainbow through the diversity and inclusion portfolio of the city’s social planner, the main “insider activist” championing the city’s rainbow crosswalks (Browne & Bakshi, Citation2013). This planner (interview, 9 July 2019) assumed the “queer file” in 2018 because “the city decided it was time to undertake this work.” Furthermore, it was suggested that the fall election made it a pivotal year: “there was a lot of willingness to act on things.” Within 7 weeks, the city flew its first rainbow flag, installed a rainbow crosswalk, and hosted Pride. Pressure had also mounted outside of city hall, with youth and immigrant para-public institutions seeking to make Burnaby more LGBTQ2S-friendly. A community organizer (Program Manager, Burnaby Neighborhood House, 5 July 2018) recalled that following the planner’s Pride street closure request, the politics surrounding the rainbow crosswalk installation “blew up.” With city council’s publicized approval of the crosswalk plan, complaints ensued from “the antis” opposing this infrastructural change (Program Manager, Burnaby Neighborhood House, 5 July 2018). Community groups responded with a networked call for support. The coordinator of the Burnaby Intercultural Planning Table (16 August, 2018) recounted that “By Monday morning,” we didn’t “have to worry anymore. There ha[d] been such a huge response from everybody … saying, we need to be more inclusive.” A single crosswalk aestheticized the rainbow in the city’s infrastructure. It combatted the homonegativity that had shaped the political landscape since 2011, but it did not generate enough electoral traction for the mayor to extend his three decades in office.

A new mayor built on this community momentum for LGBTQ2S surplus visibility by extending municipal infrastructural rainbowization. Burnaby’s Sustainable City Advisory Committee received a citizen request for additional rainbow crosswalks at six South Burnaby intersections close to key organizing institutions (e.g., Burnaby Neighborhood House, Bob Prittie Metrotown Library, Burnaby Youth Hub, and Bonsor Recreation Center). The request inspired staff to identify new rainbow crosswalk intersections. Derived from discretionary capital in the city’s Gaming Fund for “one-time projects,” its funding stream deliberately “avoid[ed] an impact on the Burnaby taxpayers” (City Council, Minutes, 13 May 2019). Although the Finance Department estimated individual crosswalk installation costs of C$8000, they only allocated C$35,000 for four projects and for repainting the first crosswalk “with more durable products” (ibid.), namely methyl methacrylate valued for its “excellent brilliance of colour, good traction, and a long life expectancy” (City of Burnaby, Citation2020). Even in its paint choice, the city underscored its aesthetic commitment to the rainbow as a tool of sexual and gender minority inclusion by creating an enduring road infrastructure that could withstand high-use and vandalism.

The city consulted citizen advisory groups and departments to determine ideal crosswalk locations and the social planner took these recommendations to the Department of Engineering to evaluate questions of visibility and long-term maintenance as part of this rainbowized infrastruggle. As the planner (interview, 9 July 2019) cautioned, “[i]t is worse to have a rainbow crosswalk that looks terrible—you want it to look good.” This rhetorical move to ensure the caliber of the rainbow aesthetic intervention speaks to the need to showcase the municipality’s minimal efforts but also to ensure the deflection of further pejorative homonegativity. Engineers proposed four “high community profile [intersections] close to civic facilities where higher pedestrian activity can be anticipated” (City of Burnaby, Citation2019c; ). As “pedestrian gateways to community services,” the locations of these rainbow crosswalks were rhetorically leveraged to uncritically communicate the heterocentric “core values of Community, Integrity, Respect, Innovation and Passion” outlined in the city’s Corporate Strategic Plan (ibid.).

Figure 4. Burnaby department of engineering (17 June 2019) proposed locations for four town-center rainbow crosswalks: (i) Brentwood (Willingdon avenue at Albert street close to confederation Center, McGill Library, and Eileen Dailly Pool); (ii) Lougheed (Cameron Street at Erickson Drive adjacent to the Cameron Community Center); (iii) Metrotown (Kingsborough Street at Mckay Avenue close to Bob Prittie Library); (iv) Edmonds (Edmonds Street at Humphries Avenue adjacent to the Edmonds Community Center) (Source: City of Burnaby, Citation2019c).

Heteronormalizing synergistic planning goals included a socially connected and universally inclusive community “that encourage[s] and welcome[s] all community members and create[s] a sense of belonging” while celebrating diversity (ibid.). Engineers determined that although “there are many major intersections with higher traffic volumes, those locations are generally not as hospitable for pedestrians and would increase maintenance costs due to increased tire wear across the painted markings” (ibid.). Throughout this technocratic civic decision-making, the universal pedestrian was prioritized over any queer subject. Indeed, the council’s motion identified walking and safe pedestrian travel as “valued aspect[s] of life” and “favorite recreational activit[ies]” of all Burnaby residents (City of Burnaby, Citation2019b). It also accentuated the city’s “extensive tradition of ensuring safe intersections … through safety features such as crosswalks, lighting and other technologies” (City of Burnaby, Citation2019a).

Burnaby’s civic leaders gave the rainbow crosswalk to all of its citizens. In so doing, they disassociated its aesthetic from local LGBTQ2S bodies, making rainbowization inadequate as compensation for a history of oversight and discrimination. This aestheticization also resonated with suburban technocratic governance which accelerated its adoption in crosswalk infrastructure. Council biopolitically instrumentalized support for rainbow crosswalks based on LGBTQ population estimates from the Canadian Community Health Survey and the BC Center for Excellence in HIV/AIDS. Since the adjacent City of Vancouver was estimated at 40,000+—“in an environment where not everyone is willing or able to declare”—it was assumed that “proportionally comparable populations of LGBTQ are believed to exist in neighboring metro communities” (City of Burnaby, Citation2019b). Appreciating the metaphorical policy power of the rainbow crosswalk’s surplus visibility, the mayor’s office also specifically requested the installation of a sixth in front of city hall and Burnaby Central High School, a location described as “well used” with symbolic value “consistent with the goal of signaling to the public the City’s goal of inclusivity” (City of Burnaby, Citation2019c). While a rainbow crosswalk aestheticizes inclusion in infrastructure, the coordinator of the Burnaby Youth Hub (interview, 11 July 2019) rightly calls it out as an attempt at political absolution: it “doesn’t mean that the city is supportive, an ally, or educated”; instead, it serves as “a visual representation of municipal support around something that is controversial.” Here, the municipality leverages the rainbow to reinforce its place-brand, attempting to gain social legitimacy as a sustainable and diverse city without political controversy. This was possible because the rainbow is so banal and malleable.

The rainbow is a “fuzzy” symbol that is simultaneously child-like, hopeful, and playful, and can even signal care (as used in day cares, elementary schools, and healthcare settings). During the COVID-19 pandemic, it has been appropriated as a symbol of hope by institutions and governments, including the UK’s National Health Service leadings to critiques of co-option by queer community groups. In response to “insider activism” in an electorally contentious governance context (Browne & Bakshi, Citation2013), rainbow crosswalks permitted Burnaby’s politicians to intensely perform progressiveness by aestheticizing inclusion through bureaucratic routines, offering compensation without adequately addressing LGBTQ2S resource and infrastructural needs. This intense 1-year fetishization of rainbow aesthetics attests to the municipal technocratic comfort with “hard” infrastructure as opposed to the messier embodied politics of “people as infrastructure” (Simone, Citation2004, p. 407). In neighboring Surrey, flagpole and lighting infrastruggles offer a counterpoint.

Aesthetically queering city hall: Surrey’s rainbow plaza lighting and flagpole politics

Artificial lighting is celebrated by urban scholars for its experimental and experiential design aesthetics (Ebbensgaard, Citation2020). For municipalities, illumination is “sacrosanct” because it shapes public nightscapes through plans, policies, and technical specifications (Edensor, Citation2015). When applied to civic spaces, like city hall plazas, lighting can enhance place-branding and public realm usage. As urban architectural monuments to “civic pride,” city halls and plazas spatialize the relationship between citizens and municipal authority (Chattopadhyay & White, Citation2014). As “instance[s] of civic materialism,” plazas are contentious public spaces where competing access demands and regulatory regimes of surveillance condition use and behavior, while centering them in urban revitalization plans (Chattopadhyay & White, Citation2014, p. 5).

Over a decade ago, the City of Surrey commissioned architects to develop a new plan for city hall to transform “the architectural landscape of the city center” and reshape “the culture and ethos” of Surrey “from ‘suburb’ to thriving business and urban center” (Architizer.com, Citation2021, n.p.). Physical structures like Surrey’s city hall are used by state actors “as abstract, neutral sites for architectural redesign and reinvention” and are “heralded as a necessary process in the city remaking itself and its perpetual state of becoming modern” (Summers, Citation2019, p. 21). Opened in 2014, the 210,000 square-foot city hall was built at a cost of C$97 million as the centerpiece of Surrey’s new downtown. While it focused on economic growth and office space expansion, it also displaced long-time low-income residents. The site was designed to create “a welcoming, warm environment belonging to a diverse demographic that cuts across cultures and age groups” in a “seamlessly integrated landscape” where the “building forms were meant to be there with as much legitimacy as the mountains themselves” (Architizer.com, Citation2021, n.p.).

Spatially intended to bring residents together at concerts, community festivals, and holiday celebrations, only some community groups have received official plaza hosting permits (e.g., Surrey Filipino Heritage Festival, African Heritage Festival of Music and Dance, Surrey Latin Festival, Surrey Tree Lighting Festival, and Party for the Planet). Initially absent from this list is the LGBTQ2S community, which the city until 2022 refused to overtly recognize by permitting access to the plaza for Pride. Instead, the LGBTQ2S community mounted history displays in city hall’s atrium and informally launched Pride from the plaza but used a nearby park and shopping mall for the event. The Plaza’s four-sided panopticon has more welcoming institutions, including Surrey City Center Library, Kwantlen Polytechnic University, and the North Surrey Recreation Center. Along the plaza’s facades are black wall luminaires, while stainless steel in-grade lighting is integrated into stone to provide underfoot illumination. Both lighting technologies accentuate the plaza’s morphology and illuminate its architectural features, creating an affective and celebratory atmosphere (Edensor, Citation2015).

Plaza lighting is curated as part of Surrey’s official annual calendar of events to recognize select community groups and activities (see, ). The calendar specifies municipal cultural governance priorities, standardizing civic actions of the recognition of diversity (e.g., Intranet postings, employee profiles, displays in the foyer of city hall, and the color of plaza lighting). Scavenged from the appendices of a corporate report from the parks, recreation, and culture and human resources departments to mayor and council, its inclusion calendar makes a rhetorical move by directing city staff to expand their “awareness and education of the diversity of Surrey and strengthen … inclusiveness” (City of Surrey, Citation2016b, n.p.). By 2020, 32 events were celebrated, 14 were ethno-cultural or religious, 15 raised awareness for social issues (e.g., autism, disability, mental health, and environment), and five were national. Artificial lighting, with its colors, atmospherics, and shadows, is civically instrumentalized to dramatize the hard surfaces of the plaza using color schemes and patterns that grow increasingly complex: red (Lunar New Year, Canada Day, Remembrance Day); pink (Pink Shirt Day); orange (Orange Shirt Day); yellow (Vaisakhi, Easter); green (Earth Day, Nowroz, Mental Health); dark blue (Autism Awareness); purple (Epilepsy Awareness, Rakhi); rainbow (Pride); white, blue, and pink (Diwali); and red and white (Canada Day and Christmas Day). Every year, new celebrations are added to the calendar to reflect an increased local awareness of international rights recognitions, national celebrations, and religious events. Municipal lighting solutions offer aesthetic representation to causes, populations, or events, and initiate some civic dialogue.

Table 1. City of Surrey staff inclusion calendar of holidays to be celebrated and accompanying civic plaza lighting schemes, 2017–2020 (Source: Authors).

While all colors are selectively available to mark calendar events in the plaza, it was not until 2018 that rainbow colors were used to celebrate Pride week, June 21–25. In this sanitized civic space, Pride and International Day of the Pink are occasions to bathe the plaza in vibrant colors, but they also avoid official sanction of messy, queer, indeterminate bodies and their colorful excess (e.g., face paints, feathers, sequins, satins, flags, banners, and slogans). The diffusiveness of rainbow lighting ephemerally compensates for the long-refusal to emplace queer bodies in civic space: “redistribut[ing] the field of the sensible in ways that neutralise opportunities for contesting this very distribution” (Ebbensgaard, Citation2020, p. 1973). The dramatic evanescence of rainbow lighting is not a tool of resource redistribution to address everyday material and service inequalities and discriminations, but it does avoid defacement and, thus, the opportunity to express suburban homonegativity. Furthermore, it serves to mute rainbowization controversies by using a similar color palette and lumination treatment to other community celebrations in the calendar. In a city where the singular municipal rainbow crosswalk has been repeatedly vandalized and the rainbow flag has only been flown once, these luminary rainbow aesthetics are unrequested activist compensation—a performance of progressiveness intended to curtail additional requests.

Surrey’s official flagpole is not located in the civic plaza. Instead, government flags fly on three poles on the northwest corner of city hall. Civic leaders have long denied local activist Pride requests to fly the rainbow or trans flags. The first request in 2005 was rejected by the mayor via e-mail. As an activist told the press, “the policy at city hall is only to have whatever the regular flags are … if they put ours up, then they’d have to do it for everybody” which they feared “would open a floodgate of requests to have flags flown over city hall” (Colley, Citation2005, p. 1). This quotation underscores a “rhetorical move” by civic leaders to condition the expression of inclusion in Surrey by refusing to make an exception for the LGBTQ2S community (Brodyn & Ghaziani, Citation2018). A 2014 request to council by a 15th Annual Pride celebration delegation was also rejected. City council responded that “only Government flags are flown at City Hall” and they would report back with “what other regions and cities have done in terms of flag protocol” (City of Surrey, Citation2014). The city clerk’s report (23 June, 2014) recommended that council adopt Corporate Policy R026 which “ensure[s] that all flags at City Hall and other City operated municipal facilities are flown and displayed in a consistent manner.” Surrey has a longstanding practice of aligning their flag protocol with the British Columbia Office of Protocol and the federal Department of Canadian Heritage. As for the “recent request to fly a symbolic flag on one of the City’s official City flagpoles,” the city clerk noted that Surrey “embraces diversity and inclusiveness” by offering “numerous initiatives and opportunities and venues to promote diversity, reduce the barriers and increase understanding to this end” (such as the Diversity Advisory and Social Policy Advisory Committees promotion of “special events” that “bring awareness of their culture or cause”). The city defines symbolic flags as those that “identify people belonging to a group,” restricting group membership to municipal, provincial, and national communities because they symbolize unity (and not division) “without distinction of race, language, belief or opinion” (ibid.). Thus, the report concluded that “Flying our Canadian, Provincial and City flags on the official City flagpoles fully represent[s] embracing diversity and inclusiveness in our City” (ibid.). The notion that state flags “deny the fundamental social conflicts within nations” ignoring their inherent fractures and continuities was not a civic consideration (Laskar et al., Citation2017, p. 196). In its promotion of unity through jurisdictional parity (such that every group is treated as equal based upon heteronormative standards), the municipality used “linguistic relativity” to sustain its performance of progressiveness with a “rhetorical move” (Brodyn & Ghaziani, Citation2018).

Non-state flags have been flown at Surrey’s city hall on two occasions. First, in 2010, the Winter Olympic flag was flown because Surrey was classified as an Olympic Venue City. Second, in 2016, the rainbow flag was used to commemorate the lives lost in the Orlando, Florida, gay nightclub mass shooting. Although these exceptions to the protocol set new precedents, no permanent exception has been made. In the case of the Orlando mass shooting, an emotional request to city council came from Surrey’s first openly lesbian city councilor who asked “that everyone take a moment to pause, reflect and remember those who lost their lives” (City of Surrey, Citation2016a). It took an extreme act of violence against the LGBTQ2S community for the city council and the mayor to agree to lower city hall’s flags to half-mast and fly the rainbow flag (from 13 June until the Surrey Pride Festival on 26 June 2016). The mayor’s accompanying official statement to council emphasized that this flag-raising gesture was intended to show “solidarity, sympathy and support for all those who lost their lives under these extraordinary and trying circumstances” (ibid.). This is a temporary civic response to an exceptional situation of homphobic violence directed at LGBTQ2S bodies that offered political absolution without the need to provide sustained solidarity to combat ongoing, everyday discrimination. When local LGBTQ2S activists made subsequent requests for a flag to be flown, they were still denied, an outcome that journalists saw as inconsistent. Highlighting the performative dimensions of the Orlando commemoration as a special moment of progressiveness, the press drew attention to the city’s protocol inconsistencies and ridiculed arguments that the cost of a fourth community flagpole was prohibitive (Booth, Citation2014). By 2022, however, the city capitulated. A small flagpole was erected in the plaza above the entrance doors to city hall, permitting community flags to be temporarily flown, physically separated from the city’s jurisdictional flags and their protocols.

Flag raisings are anything but quotidian acts; not only are they full of protocol, they symbolize “imagined communities” (Anderson, Citation1983, p. 1) and banal forms of nationalism (Billig, Citation1995). Like the ubiquitous presence of a nation’s flag, the rainbow too can be found everywhere, signaling banal belonging. The rainbow may be used to “flag” sexual and gender diversity in everyday civic life, as it navigates between complex webs of social norms, languages, and fictions offering connection to a broader community beyond any municipality (Klapeer & Laskar, Citation2018). Nevertheless, as boundary objects, rainbow flags are not static; rather, they are “multifocal and multivalent,” facilitating “interactions, translations, and coherence, but also stir[ring] conflicts over meaning across diverse social worlds” (Laskar et al., Citation2017, p. 194). Where a rainbow flag’s materiality creates controversy and leads to municipal infrastruggles around community representation, the ephemerality and surplus luminescence of rainbow civic plaza lighting is politically palatable and difficult to vandalize as aestheticized infrastructure. The rainbow flag became suburban infrastructural surplus for homonegative publics because it usurped government space, while rainbow plaza lighting made a diffuse and disembodied civic spatial claim. Thus, LGBTQ2S infrastruggle was greater when accessing harder infrastructures (e.g., flagpoles, roadways, parks, and plazas) via bureaucratic protocols, because it invited the centralization of queer excess by emplacing LGBTQ2S bodies in suburban public spaces.

Conclusion

Municipal infrastructure is a site of political struggle and claims-making because its technological and aesthetic materiality is shaped by bureaucratic processes that condition social action. By reinforcing cultural norms and requiring literacy for residents to use and access it, infrastructure materializes place-based power dynamics, becoming the basis of local infrapolitics through which minority groups negotiate, disobey, and contest its obduracy on a micro- and embodied scale. As a way of seeing the political assumptions buried within infrastructure, infrastruggle is a conceptual tool to appreciate the inconspicuous infrapolitics of subordinated groups in the public realm. For sexual and gender minorities, not only are many aspects of municipal infrastructure hetero- and cis-normative, but the rainbow that aestheticizes their inclusion for progressive gain also conditions and limits how “we come to see, know, and practice” queerness within municipal policy and political frameworks (Summers, Citation2019, pp. 21–22). By reducing the complexity of a diverse social group to a rainbow, the repetition of this aesthetic as inclusion provides civic comfort of “assumed knowingness” that narrows bureaucratic visions of how queerness should be “expressed, recognized, and visualized” in suburban municipal infrastructure (Summers, Citation2019, p. 22). While queer can be “stretched and pulled in various ways to do different work in different contexts” (Gerteman as citied in Isherwood, Citation2020, p. 232), in municipal governance it requires deconstruction of a universal municipal subject, confrontation of the compulsory heterosexuality conditioning infrastructure, and critical interpretation of infrastructure’s aesthetics.

On the peripheries of the Vancouver city-region in Burnaby and Surrey, conflicts over LGBTQ2S policy inclusions and the relative extent of progressiveness occurred within the confines of a local political system in which heteronormativity remains pervasive, invisibilized, and instrumentalized through bureaucratic processes. Neither case study municipality has a single LGBTQ2S-focused policy for inclusion. However, bureaucrats in both suburbs linked rainbowization to infrastructural functionality and social sustainability (e.g., the safety of pedestrians, suburban walkability, the celebration of municipal diversity, and governance protocol). A municipal micro-technocratic fixation with paint quality, luminescence, and flag protocol, offers the procedural illusion of “progress” and the bringing of LGBTQ2S “issues” into civic discourse while never actually reworking the urban policies of suburban citizenship that shape LGBTQ2S lives year-round through access to and inclusion in housing, transportation, community services, and public spaces. Small, scavenged, and often temporary acts of rainbowizing crosswalks, plaza lighting, and flagpoles, then, afford a degree of LGBTQ2S visibility, but civic leaders instead focused on tempering its excess. They strove to balance a politics of visibility within the confines of localized homonegative attitudes among some of their electorate, leveraging the rainbow as political absolution for their relative municipal policy inaction.

LGBTQ2S municipal infrastruggles are grounded in iterative performances of progressiveness as manifest through rhetorical moves in search of political absolution. Burnaby exemplifies a peripheral municipality where the aesthetic difference of the rainbow is integrated into place-branding. Civic leaders diffused the rainbow aesthetic through “hard” suburban infrastructure initially only because of pressure from a network of public and para-public insider activists and allies who came together to launch a municipal Pride movement. In a grand gesture of political absolution, Burnaby’s accelerated distribution of rainbow crosswalks targeted prominent town center intersections near municipal facilities, but did little to change a mayoral history of active avoidance that had resulted not only in LGBTQ2S invisibility, but also more concerningly, a lack of programming or community services. As policy metaphor, this more permanent visual intervention of surplus rainbowization in crosswalk infrastructure swiftly gathered cross-departmental traction as it moved through the bureaucratic protocols of city hall where decisions were made about costing, funding, site selection, materials, installation, and maintenance. By working within this established civic political system to aestheticize the rainbow, queerness accrued value as a “prized aesthetic” (Summers, Citation2019, p. 4). It buffered LGBTQ2S inclusion from homonegative reactions while responding to pressure from insider activists and parapublic agencies for political legitimacy. By resisting public statements of LGBTQ2S inclusion and then ultimately intensifying municipal rainbowization, infrastruggles in Burnaby were acted out through the technocratic realm. Surrey exemplifies a municipality with a long history of homonegative politics and LGBTQ2S activism that has strategically aestheticized the rainbow in “soft” infrastructure. By regulating the emplacement, duration, and medium of rainbow infrastructural aestheticization through bureaucratic frameworks, Surrey’s civic leaders gained inclusion legitimacy all the while downplaying LGBTQ2S visibility in order to avoid the accusations of surplus visibility so as to maintain representational parity. This city has only one rainbow crosswalk, refuses to fly the rainbow flag on its official flagpole, and only recently included the “aesthetic upgrade” (Summers, Citation2019, p. 16) of diffuse rainbow lighting in its city hall plaza to temporarily celebrate Pride as part of a multicultural calendar of events. The manufacturing of a shared sensuous disposition of the rainbow aesthetic is merely one part of an urban revitalization project. As such, it temporarily performs LGBTQ2S progressive inclusion while anaesthetizing public reception of sexual and gender difference. Rainbow aestheticization, then, goes hand-in-hand with controlling “the look” of this center of political power, and the people who are invited to be visible and politically active within it. Taken together, these two case studies demonstrate that rainbow aestheticization in the “hard” and “soft” infrastructure of peripheral municipalities is embedded in conflicting visions of place that result in infrastruggle, often in response to activists and allies’ calls for greater social inclusion.

Infrastruggle over the rainbow aestheticization of municipal infrastructure epitomizes LGBTQ+ infrapolitics and the contestations emerging between municipal actors, activists, and parapublic agencies in suburbs lacking queer infrastructure. The rainbow itself is a globally recognizable symbol of LGBTQ2S “liberation” and rainbow aesthetics, as a mode of infrastructural reconfiguration, are “plastic enough towards different meanings and interpretations” to technocratically accrue value as floating signifiers of social inclusion and civic performances of progressiveness (Laskar et al., Citation2017, p. 196). Yet, the rainbow is too easily co-opted by state actors who use rhetorical moves in the service of political absolution. It confines LGBTQ+ inclusion to the symbolic realm and maintains heteroneutrality. The rainbow aesthetic, then, is inadequate as a queering device in municipal governance because it does not offer a new kind of politics. In these cases, it does not confront or disrupt suburbia’s entrenched heteronormativity. It does not adopt a queer way of seeing or an attitude that questions the standardization and reproduction of the rainbow motif on municipal infrastructure. As such, it does not offer queer bodies an alternate suburban future (Isherwood, Citation2020). Beyond mere performance, any truly “progressive” commitment to social inclusion within liberal democracies means inviting minority citizens to exert their agency in unprescribed ways that can help reconfigure the built-in structural inequities governing municipal planning and policy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alison L. Bain

Alison L. Bain is a professor of the Geographies of Inclusive Cities and cochair of the Urban Geography section in the Department of Human Geography and Spatial Planning at Utrecht University and Adjunct Professor at York University. Her research examines the spatial, infrastructural, and creative affordances of cities and their peripheries for cultural workers and LGBTQ+ populations. She leverages feminist and queer theories to study urbanism/urbanization and suburbanism/suburbanization through the lenses of identity politics, social justice, artistic labor, and vernacular creative practice, unpacking the power relations shaping urban inequities as manifest through the planning and policy frameworks of urban governance. She is a North American Managing Editor for the journal Urban Studies, has authored Creative Margins: Cultural Production in Canadian Suburbs, co-edited two editions of the textbook Urbanization in a Global Context, and has co-edited the book The Cultural Infrastructure of Cities.

Julie A. Podmore

Julie A. Podmore is a professor in Geosciences at John Abbott College and Affiliate Assistant Professor in Geography, Planning and Environment at Concordia University in Montreal. Julie is a socio-cultural geographer with an interest in LGBTQ+ urban histories and geographies. Her first publications focused on gentrification and the historical geographies of Montreal’s lesbian communities, but more recent projects examine LGBTQ+ neighborhood formation, suburbanisms, activisms, municipal governance, and planning and policy inclusions in Canadian cities and suburbs. She is co-editor of Lesbian Feminisms: Essays Opposing Global Heteropatriarchies and The Cultural Infrastructure of Cities.

Notes

1. While LGBTQ+ is the more common international acronym for sexual and gender minorities, the geographically specific acronym LGBTQ2S (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Two-Spirit) is used in this paper to combat the erasure of the long-standing presence of Two-Spirit communities (a term used by some Indigenous peoples to refer to the intersection of a masculine and feminine spirit in their sexual, gender, and spiritual identities) on Turtle Island (North America) and within the unceded Indigenous territories of the Vancouver city-region.

2. These categories included: (i) awards (selective recognition of specific LGBTQ2S individuals or organizations to rainbowize civic leadership); (ii) delegations (reception of LGBTQ2S representatives at municipal council and committee meetings to inform civic leadership); (iii) funding requests (financial support sought by LGBTQ2S community groups from finance committees and departments for rainbowized events and infrastructure); (iv) information (mention of LGBTQ2S content in council and committee meetings); (v) infrastructure (council, committee, and departmental discussions of LGBTQ2S issues in relation to municipal infrastructure); (vi) presentations (sharing of information by delegations or internal civic actors); (vii) proclamations (mayoral statements promoting the recognition of LGBTQ2S populations and social issues); (viii) reports (civic documents describing departmental and committee responses to LGBTQ2S inclusions); (ix) requests (community group rainbowization demands other than funding); and (x) updates (council and committee informational statements that reference LGBTQ2S communities).

References

- Addie, J. P. (2016). Theorising suburban infrastructure: A framework for critical and comparative analysis. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 41(2), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12121

- Allman, D. (2013). The sociology of social inclusion. Sage Open, 3(1), 215824401247195 n.p. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244012471957

- Alm, E., & Martinsson, L. (2016). The rainbow flag as friction: Transnational, imagined communities of belonging among Pakistani LGBTQ activists. Culture Unbound, 8(3), 218–239. https://doi.org/10.3384/cu.2000.1525.1683218

- Amin, A. (2014). Lively infrastructure. Theory, Culture, and Society, 31(7–8), 137–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276414548490

- Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso.

- Architizer.com. (2021). Surrey City Hall + Civic Centre. https://architizer.com/projects/surrey-city-hall/

- Babbie, E. R. (2020). The practice of social research. Cengage learning.

- Bain, A. L. (2022). Queer affordances of care in suburban public libraries. Emotion, Space, and Society, 45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2022.100923

- Bain, A. L., & Podmore, J. A. (2020a). Scavenging for LGBTQ2S public library visibility on Vancouver’s periphery. Tidjschrift voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 111(4), 601–615. https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12396

- Bain, A. L., & Podmore, J. A. (2020b). Challenging heteronormativity in suburban high schools through “surplus visibility”: Gay-Straight Alliances in the Vancouver city-region. Gender, Place, and Culture, 27(9), 1223–1246. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2019.1618798

- Bain, A. L., & Podmore, J. A. (2021a). Relocating queer: Comparing suburban LGBTQ2S activisms on Vancouver’s periphery. Urban Studies, 58(7), 1500–1519. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020931282

- Bain, A. L., & Podmore, J. A. (2021b). Linguistic ambivalence amidst suburban diversity: LGBTQ2S ‘social inclusions’ on Vancouver’s periphery. Environment and Planning C, 39(7). https://doi.org/10.1177/23996544211036470

- Bain, A. L., & Podmore, J. A. (2021c). More-than-safety: Co-creating resourcefulness and conviviality in out-of-school spaces for suburban LGBTQ2S youth. Children’s Geographies, 19(2), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2020.1745755

- Bain, A. L., & Podmore, J. A. (2022). The scalar arrhythmia of LGBTQ2S social inclusion policies in the peripheral municipalities of a ‘progressive’ city-region. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 46(5), 784–806. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.13121

- Bain, A. L., Podmore, J. A., & Rosenberg, R. D. (2020). ‘Straightening’ space and time? Peripheral moral panics in print media representations of Canadian LGBTQ2S suburbanites, 1985–2005. Social and Cultural Geography, 21(6), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2018.1528629

- Basu, R., & Fiedler, R. (2017). Integrative multiplicity through suburban realities: Exploring diversity through public spaces in Scarborough. Urban Geography, 38(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1139864

- Berg, L. D. (2011). Banal naming, neoliberalism, and landscapes of dispossession. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 10(1), 13–22. https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/881

- Billig, M. (1995). Banal nationalism. Sage.

- Binnie, J. (2004). The globalization of sexuality. Sage.

- Bitterman, A. (2021). The rainbow connection: A time-series study of rainbow flag display across nine Toronto neighborhoods. In A. Bitterman & D. B. Hess (Eds.), The life and afterlife of gay neighborhoods: Renaissance and resurgence (pp. 117–140). Springer.

- Booth, M. (2014, July 10). Pride flag flap reveals flaws in city policies. The Tri-Cities Now, A11. https://www.surreynowleader.com/community/booth-pride-flag-flap-reveals-flaws-in-surrey-policies/

- Boyd, R. (2006). The value of civility? Urban Studies, 43(5–6), 863–878. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980600676105