ABSTRACT

As a leading mechanism of the global neoliberal paradigm, financialization plays a significant role in the growth of economies and changes in urban development patterns. Though particularly significant for post-socialist European countries, research on urban financialization considering both economic (rental income, property sales, interest rates) and noneconomic aspects (social dynamics, social and legal norms, financialized discourses) is yet to emerge in Serbia. Observing the period after the 2008 global economic and financial crisis, and based on multiple analyses (statistical, documentary and discourse), this paper first provides an overview of different global and national financial indicators, then elucidates the impact of market financing on the built environment at the national level, and, finally, illustrates the financialization of urban planning policies and discourses exemplified in the Belgrade Waterfront urban megaproject. The empirical analysis provides not only an insight into a strong structural and dynamic conditionality between various dimensions of financialization, but also highlights the nuances in decision-making, planning and governance influenced by the financialized discourses.

Introduction

The notion of financialization we face today originated in the 1990s in the United States (Krippner, Citation2005; Levine, Citation1997). Briefly put, financialization can be seen as a new stage in neoliberal financial capitalism, emerging as: a new regime of the accumulation involving the investment of accumulated capital into the built environment; a new form of corporate governance that prioritizes returns to shareholders; and as an individual strategy for citizens to become financial actors. As the financialization of real estate has become dominant after the global crisis of 2008, involving the widest circle of actors, not just financiers, interested in large urban development projects, i.e., investments into commercial properties in large cities, financialization as a strategy of economic recovery has also encouraged speculative investment approaches directly affecting urban (re)development, planning and governance.

Aalbers (Citation2019, p. 3) defines financialization as the “increasing dominance of financial actors, markets, practices, measurements and narratives at various scales, resulting in a structural transformation of economies, firms (including financial institutions), states and households.” He further distinguishes the financialization of the public sector (e.g., government, public authorities, education, health, social housing, etc.), which becomes dominated by financial discourses and practices. Accordingly, the financialization of public policy, particularly urban policy, means its transformation into a tool to facilitate financial investments in land, real estate and infrastructure. Briefly put, instead of providing public goods, urban planning becomes the enabler of creating financial assets (Aalbers, Citation2019, p. 7). However, despite growing research on the interdependence of urban development and financial markets, especially in the areas of securities, mortgages, and public property (Guironnet & Halbert, Citation2014), the nature of financialization as a profoundly spatial process has been neglected (French et al., Citation2011). Hence, the elucidation of the concept in the field of urban development requires (urban) research not to deal only with the financial capital, but also with the material capital (i.e., the built environment) and different mechanisms through which facilities and urban land are continuously reproduced as financial assets and are monetized on the market. Understanding land as a financial asset is a delicate perspective: financialization has the potential to harm public goods (Horodecka & Zuk, Citation2021), urban territorial capital and resources, common interest, public ownership, and public finance (Lapavitsas, Citation2013), hence, eroding the “social pact” between capital and labor, which serves as the foundation of the welfare state (Krippner, Citation2005).

In developed countries, the concept of financialization has been interpreted in different ways in various disciplines, however, primarily being understood as a globally and externally driven process in the neoliberal narrative (Epstein, Citation2005; Foster, Citation2007; Stiglitz, Citation2000). In developing countries, the research on financialization focuses either on market changes within a particular country over time, i.e., attending to the “longitudinal analysis” of financialization (Correa et al., Citation2012; Karwowski & Stockhammer, Citation2016; Rethel, Citation2010), or on the development of economics, especially the non-financial corporations (Becker et al., Citation2010; Demir, Citation2009; Gabor, Citation2012; Orhangazi, Citation2008). Hence, the general understanding of financialization as a global phenomenon triggered by external factors seems too simplistic. In addition, developing countries, as well as post-socialist countries characterized by strong financial deregulation, have experienced significant financialization of commercial properties and households and inflationary real estate prices without exposure to stronger foreign capital inflows (Karwowski & Stockhammer, Citation2016). This points to the role the national institutions and internal movements play in a better understanding of financialization in single countries (Rethel, Citation2010). Finally, despite the growing literature on financialization in post-socialist Europe, the analysis of the urban level that reflects all social relations operating in polarized spaces and local socio-cultural contexts influencing urban development strategies remains vague (Büdenbender & Aalbers, Citation2019).

Against this background that highlights the complex nature of the concept and as there have been neither systematic, rigorous, nor transparent evaluations of financialization in Serbia, the paper, more broadly, aims to elucidate the nature of the financialization process in Serbian transitional society, while, more narrowly, focusing on a critical understanding of the effects of financialization as a tool to shape urban development. Inspired by Becker et al.’s (Citation2010) approach comprising both economic and noneconomic aspects of financialization and drawing on Aalbers’ (Citation2019, p. 3) classification of dimensions of financialization, encompassing various levels (macro, meso, micro) and aspects (financial, material, discursive), the comprehensive research aim includes three more specific goals addressing the mentioned levels and aspects respectively. First, to critically evaluate financialization in the Serbian post-socialist socioeconomic-political setting, we analyze different global and national financial, monetary, investment, and macroeconomic indicators. Second, to elucidate the growth of urban financialization in Serbia, we focus on the significant impact of market financing on the built environment. Lastly, to examine the financialization of noneconomic aspects, we illustrate the role of the state, policy narratives and public discourses as exemplified in the development of the Belgrade Waterfront (BW) urban megaproject. Although the BW megaproject case has been covered in research literature attending to diverse topics in the domain of urban governance (Grubbauer & Čamprag, Citation2019; Koelemaij & Janković, Citation2020; Machala & Koelemaij, Citation2019; Perić, Citation2020a; Piletić, Citation2022; Perić & D’hondt, Citation2022; Zeković & Maričić, Citation2022; Zeković et al., Citation2018), it was not explored through the lens of urban financialization, despite the compatibility between the topic (megaproject development) and the approach (urban financialization). Notably, this is the research area where not only financial interests for monetizing the land and using land as a dominantly financial asset (without attending to social values), but also the forms of “authoritarian neoliberalism,” “capital urbanization,” and “populism” (Perić & Maruna, Citation2022; Sager, Citation2019; Tansel, Citation2017) are all mixed, making the case rich for the analysis at various scales and using different methods.

The paper is structured as follows. The introductory chapters position the topic of urban financialization, first, presenting the current body of literature on the financialization of the built environment, and second, reflecting upon the practice of urban financialization in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and Southeast Europe (SEE) to highlight a theoretical approach appropriate for exploring the practice. This is followed by a brief methodological section, which describes a multi-scalar mixed-method approach applied. The central part of the paper presents the findings of the analysis of urban financialization in Serbia, focusing on the economic dimensions of financialization at the macro and meso levels (as influenced by international and national factors), followed by the empirical evidence of the BW urban megaproject, depicting the noneconomic dimension of financialization: the financialization of the policy and public narratives. Finally, the paper concludes by summarizing the results of the study on the financialization of “the urban” in Serbia, attending to the interdependence between national financial and urban real estate indicators, and the role of finance as a discourse.

The financialization of the built environment: A conceptual overview

Urban development, be this decontamination and redevelopment of polluted, once industrialized land, construction of new buildings and infrastructure, and/or leasing and management of urban facilities, is a flourishing field for implementing various dimensions and mechanisms of financialization. Namely, treating land as a financial asset (Haila, Citation1988) means assigning (urban) land “not just a coordinating but also a transformative role in the transition from industrial to financial capitalism” (Kaika & Ruggero, Citation2016, p. 3). Shatkin (Citation2017) indicated that the real estate–driven creation of new urban space has emerged as a central tool for the achievement of development goals through three interdependent logics: the “technology of governing,” “strategy of accumulation,” and the “rent-seeking.” On the one hand, state and its institutions as managers of state-owned land undoubtedly represent the driving force of the urban real estate, through market-based mechanisms of urban governance. On the other hand, the real estate investment trusts (REITs) provide the ability to fictitious and interest-bearing capital to transfer into real estate development, directly extracting rents from real estates and land (through rental income, property sales, interest rates) and monetizing them through the trading of financial equity in the market. The mutual relationship between the state and REITs in the process of neoliberal financialization is supported by monetary policy based on “targeting inflation,” liberalized financial markets and flexible labor markets. A loose monetary policy usually aims at sustaining speculation and rising asset prices, hence, possibly creating real estate growth bubbles, however, with policy bailouts for the financial sector as an imperative.

The research on the benefits of the financial actors at the expense of local community became particularly strong after the 2008 global financial crisis (Guironnet et al., Citation2016; Savini & Aalbers, Citation2016; Weber, Citation2010), whereas urban development projects became the confrontational issue between global markets and local demands (Perić & D’hondt, Citation2022; Savini & Aalbers, Citation2016; Swyngedouw et al., Citation2002). Lake (Citation2015) points to the subordination of urban policy to the logic of the financial sector, with the help of financialization that generates the repurposing of urban public policy with the dominant fulfillment of developers’ expectations, rather than pressing social issues. Waldron (Citation2019) provided a new insight into the modification of how and why planning policy rules, practices and narratives have been subject to changes under the financialization of planning policy. Research on the financialization of urban policy and multi-scalar governance (Adisson, Citation2019; Anguelov et al., Citation2018; Waldron, Citation2019) indicates that the policy is increasingly being adapted and applied as a financial instrument to facilitate investment in urban built environment, and not as a practice of solving social needs (Lake, Citation2015). In this regard, financialization does not only transform financial circles, institutions and actors of urban development, but also contributes to the use of evaluation methods from financial markets in the financialization of the built environment and urban policy (Adisson, Citation2019).

The strong influence of global financial markets, new financial sources and investment vehicles penetrate deeply not only into the current activities of cities, but also anticipate, contour and determine the future of urban development in the long term, through e.g.,: the introduction of investment vehicles of greater degree of risk (stocks, options, futures, risky financial derivatives); new instruments of local public debt; anticipation of fiscal extraction of part of future local/urban budget revenue; conversion of part of future local public revenue to new financial instruments; assumption of non-performing loan (NLP) risk at the expense of the state; avoidance of taxation, etc. (Weber, Citation2010). Under such circumstances, city governments become increasingly exposed to fiscal constraints and budget rationalization. At the same time, the neoliberal state supports the development of innovative activity, as well as new forms of income increase largely mediated by global financial means. Peck and Whiteside (Citation2016) believe that this caused mutations from entrepreneurial to increasingly financial forms of urban governance (or, from bank-based to market-based by financial instruments), i.e., the increasing reliance of city authorities on financialization real estate market. Consequently, this led to the strengthening of new mechanisms that transform relations between public and private actors and define new forms of financial investments, techno-fiscal management, and income generation through new (project) financial engineering. Also, the austerity imposed on public budgets after 2008 encouraged local governments to take more debt in capital markets to finance urban services and infrastructure.

The financialization of urban development (as extracting of values of urban resources) means a distinction between creating of value in urban areas and appropriating the value of urban environment (as a goal of “alpha” profit) in line to capital allocation by mainstream financial actors. The results of the financialization of urban development can be an excessive supply of various commercial spaces and residential spaces for rich social groups; maintenance of continuous growth of real estate prices or their short-term stagnation; emptying of urban land and growing vacant spaces (empty buildings), usually accompanying gentrification and displacement of poorer citizens and other urban land users. Waldron (Citation2019) highlights issues regarding democratic urban policy development and the role of external (e.g., foreign capital) interests in shaping planning reforms. Namely, influential actors in finance and real estate development initiate the “development financial viability narrative” as an obstacle to creating housing supply so that planning must respond to market conditions. Foreign economic power shapes the national interests in real estate and urban development thus making foreign investors directly involved in decision-making, creation of public policies, regulation and urban planning and governance, ultimately contributing to socio-spatial inequality (Alexandri & Janoschka, Citation2017).

The literature on financialization ignores the role of social action and certain actors in coordinating and shaping the flows of global financial capital into local real estate, most often with a focus on the involved politicians, managers, and banks, however, with the absence of bureaucrats/administrative apparatus, advisors, planners who shape necessary institutional, legislative, and fiscal frameworks that support financialization in practice. At the urban level, the financialization of the built environment is often associated with the transformation of local state actors and urban elites into “agents of financialization” (Kaika & Ruggero, Citation2016), rarely specifying local mechanisms and relations to global actors. Therefore, although the expansion of foreign capital into property markets is considered a political process shaped by local actors, it remains vague why real estate markets engage with forms of urban financialization (Büdenbender & Aalbers, Citation2019, p. 670). Such research demands a deep understanding of both global and local contemporary conditions and more contextual and historical factors that affect current developments. As a result, the comprehensive and multi-dimensional research on financializing “the urban” is still an emerging area with exponential potential for future research.

Urban financialization in post-socialist societies: Practice and theoretical underpinnings

The European Union’s “inner periphery” (Göler, Citation2005) or even “super-periphery,” such as the so-called Western Balkans (Bartlett & Prica, Citation2013), has been burdened with the financialization of real estate, urban land and housing influenced by various factors. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the countries behind the Iron Curtain began the transformation of their centrally planned economy toward a market economy and political ideology of communism into a pluralist democracy. The commons built up during the socialist period were rapidly privatized, commodified and financialized, becoming the main drivers of urban development. Accordingly, the built environment has often generated, reproduced and intensified urban and social inequalities and gentrification (Kubeš & Kovacs, Citation2020). Under such circumstances, fast, financialized and decontextualized urban development was made possible through subordinate financialization of commercial and office real estate (Büdenbender & Aalbers, Citation2019; Mikuš, Citation2019; Posfai et al., Citation2018). Posfai et al. (Citation2018) argued on the dependent financialization and spatial inequalities in Eastern Europe, which reflect systematic patterns of unevenness and dependencies as the consequences of capital scarcities. The European (semi)periphery has been involved in financialization from a subordinate position, i.e., post-socialist countries provide room for the expansion of capital and reterritorialization (Brenner, Citation1999). The critical function of subordinate financialization is the absorption of globally mobile capital into private and mortgage loans, resulting in the one-way export of profits from the (semi)periphery to developed economies (“core”/“center”), and exposure of the (semi)periphery to the risks and discipline of financial markets. Interest rates and deficient private debt levels make these countries attractive for investment (Karwowski & Stockhammer, Citation2016), contributing to the construction boom in many cities in the (semi)periphery. In this regard, CEE countries (especially Hungary, the Czech and Slovak republics, and Poland) show similar dynamics of real estate financialization (Büdenbender & Aalbers, Citation2019; Kubeš & Kovacs, Citation2020; Sykora & Bouzarovsk, Citation2011).

The financialization of real estate opens a spatially sensitive perspective. Whether the policy facilitates or restricts foreign investment in the built environment depends not only on the attitude of local politics, but also on the broader institutional and regulatory context. The interaction of transitional reforms with existing socialist-era frameworks created an unfinished institutional landscape, which capital readily exploited. The countries with persistent financialization tendencies are Croatia, Latvia, Slovakia, and Poland, while Hungary and Estonia have displayed signs of possible de-financialization since the 2008 crisis. The financialization of the state might be particularly productive in Croatia, Hungary, Estonia, Latvia, Poland and Slovakia (Mikuš, Citation2019), as they tend to display the highest values for most of the indicators of financialization. Also, the financialization of the state corresponds to changes in the operational practices of the entities constituting the “state,” as well as their relationships (Lapavitsas, Citation2013; Mikuš, Citation2019; Posfai et al., Citation2018; Radošević & Cvijanović, Citation2015). Affected by numerous transformations of specific institutions, organizations and practice, the financialization of the state in the post-socialist Europe include the “state” (more precisely, social actors who control state power), various social forces, political strategies, obstacles and resistance to their realization. Sometimes processes identified in one spatial-temporal context may be irrelevant or impossible in another. States may undergo financialization spontaneously, as a result of specific public policies, or as a response to the power of financial capital (Aalbers, Citation2017), while peripheral states may be forced to do so by international actors (Mikuš, Citation2019).

With the previous in mind, it is interesting to elucidate theoretical approaches that affected research on financialization in post-socialist societies. Caused by financial liberalization or deregulation (Gabor, Citation2012; Georgia & Janoschka, Citation2017; Karwowski & Stockhammer, Citation2016), the study of financialization in developing and post-socialist countries is based on heterodox approaches such as: the post-Keynesian approach (Correa et al., Citation2012; Demir, Citation2009), the Marxist approach, which includes changes in the relations between enterprises, banks and workers, and international integration through global financial flows (Lapavitsas, Citation2013), or the institutionalist tradition, e.g., regulationist learnings (Becker et al., Citation2010). The latter seems particularly relevant for elucidating the role of state as being dominated by financial narratives, practices and measurements.

Aalbers (Citation2019, p. 3) considers it only possible to think of financialization as an accumulation regime by considering the role of the state in its different constitutive dimensions. For Becker et al. (Citation2010, p. 226), accumulation and regulation are dialectically linked. Accordingly, the regulationist approach offers not only analytical concepts for the accumulation process, but connects forms of accumulation to prevalent social and legal norms and forms of state intervention. Such an approach of linking social dynamics to various financialization dimensions is particularly relevant for post-socialist societies where international financial consortia, the state, politics, and stemming legal and social norms all play critical roles in understanding the process of financialization (Becker et al., Citation2010; Büdenbender & Aalbers, Citation2019).

To enable systematic analysis of the financialization process, the theory of regulation emphasizes the following aspects (Aalbers, Citation2019; Becker et al., Citation2010). First, the role of the state vis-à-vis previous forms of capital has been highlighted. Namely, the state facilitates financial investments, particularly in material assets like land, real estate and infrastructure. In so doing, the state becomes detached from its traditional role of securing public goods and protecting public interest to instead transform its organizational culture toward the idea of New Public Management, with policies modified to serve the creation and growth of financial assets (Aalbers, Citation2019, p. 8). Second, as financialization is connected to the changes of regulation, it is crucial to attend to the political processes that enable financialization. In other words, the proliferation of financial assets implies the shift into the structure of institutional settings and decision-making bodies, often affecting deregulation in policymaking. Policies, including urban policy, become tweaked to enable and attract mostly foreign (Becker et al., Citation2010), but also institutional capital (Aalbers, Citation2019). Finally, changes in regulation are socially and politically contested, including international bodies as drivers of financialization and domestic actors that serve to modify and implement global trends into the local settings, with greater or lesser success in addressing the given legal and social norms (Büdenbender & Aalbers, Citation2019). As these three aspects are relevant for examining urban financialization in Serbia as a periphery, they will be attended to in the central segment of the paper devoted to the micro-level analysis of the BW urban megaproject.

Methodology and data

As presented, global flows, national institutional contexts and locally regulated social relations interact to strengthen the financialization of “the urban,” thus engaging with various dimensions, mechanisms and instruments of financialization. To address the nature of urban financialization in Serbia, attending to economic, but also noneconomic aspects, e.g., social dynamics, social and legal norms (Becker et al., Citation2010) and even the specific discourse used to promote finance (Aalbers, Citation2019, p. 3), the paper applies a multi-scalar mixed-method approach conjoint in an in-depth case study. The following methods have been used to address the main research goals.

To critically evaluate the type, scope and dynamics of financialization in the Serbian post-socialist socioeconomic-political setting, observed particularly in the post-global crisis period (2008–2021), we identify five dimensions of financialization and their quantitative indicators. The data concerning indicators have been collected through publicly available registers of the national and international institutions (e.g., the Bank of International Settlements (BIS), CEIC, Eurostat, World Bank, National Bank of Serbia (NBS), Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (SORS), the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Construction, Transportation and Infrastructure).

To shed light on the almost exponential growth of the process of urban financialization in Serbia (i.e., financialization of land, real estate and infrastructure) in the analyzed post-crisis period, we interrelate the findings concerning macro-economic trends and their reflection upon urban processes, using the specific data available from the national institutions and other primary sources (legislations and regulations, statistical reports, official national reports, public policies, and strategic documents).

To examine the process of urban financialization in contemporary Belgrade’s urban development, informed by the previously elucidated regulationist approach to financialization as a proper lens for exploring urban financialization in the post-socialist context, we apply qualitative analysis of the BW megaproject development, attending to the following variables: the nature of incentives of private developers (e.g., rent-seeking, i.e., directed to profit only and/or of exercising political influence); the response of the state public authorities (e.g., reactive, i.e., fully supportive to the developers’ demands, or proactive, i.e., enabling the setting for addressing both private and public interests); the position of planners toward the partnerships between investors and public authorities; and the level of public engagement as a response to the main coalitions in urban megaproject development. As the essential understanding of the mentioned variables is possible in the period before the official construction on the site of the BW megaproject started, the triangulation approach in data generation relates to the period between 2012 and 2015. More precisely, we collect: (1) official documentation (national laws, plans, strategies, regulations, and contracts) that depict the position of the state (and city) authorities toward the megaproject development, (2) scholarly articles on the BW megaproject that provide a critical perspective on the current urban practices, and (3) newspaper announcements, which illustrate the general narrative behind the BW megaproject implementation.

The financialization of urban development in post-socialist Serbia

This section presents the process of urban financialization in contemporary Serbia. Like in other post-socialist states, financialization in general and urban financialization have been affected by both domestic circumstances and global conditions. Hence, the following subsections: nest the trend of financialization into the Serbian post-socialist economic, institutional and political setting, describe the core features of urban financialization in Serbia, and provide an example of urban financialization through the mechanism of urban megaproject development, depicted in the case of the BW project.

Serbian post-socialist context and financialization

Over more than 3 decades, Serbia has been moving from a centrally planned economy with self-management elements to a market-based economy, however, critical institutional reforms are yet to emerge. A brief overview of the economic, institutional and political features of the Serbian post-socialist transition across various phases is given as follows.

Although Yugoslavia was never a part of the Soviet bloc, exercising self-management socialism, i.e., “industrial democracy” (Ramet, Citation1995), and “market socialism” (Zukin, Citation1975), i.e., the free-market principles introduced into a state-controlled economy, the collapse of the state during the 1990s’ civil wars, sanctions by the United Nations, economic blockade and an isolated position resulted in a particularly long and difficult institutional reform in Serbia. The critical contextual factors of the post-socialist transition in the 1990s—harsh socioeconomic conditions seen in the unregulated capture of public goods, land and facilities, and an obsolete institutional framework—conditioned a prolonged economic recession, impoverishment and decline in quality of life, brain-drain, an influx of over 700,000 refugees and internally displaced persons, immigrants, and massive illegal construction (Perić, Citation2020a; Zeković & Maričić, Citation2022). As in other CEE countries, the financial liberalization and the privatization of social property began in Serbia in the early 1990s as part of the IMF-supported program, enabling the formation of the capitalist class and attracted many international financial actors. In 1991, Serbia adopted the first law on privatization during the socialist government. However, the integration into the system of financial capitalism and the intensification of the privatization of the economy became feasible only in 2000s.

The beginning of the new millennium designated a political and ideological rebranding effort for Serbia. In political terms, Serbia overthrew the authoritarian political regime in late 2000 to embrace democracy—though the latter being labeled as “defective” (Vujačić, Citation2009) and “proto-democracy” (Vujošević, Citation2010), with the glorification of a neoliberal approach and policy framework with significant state control mechanisms. However, this approach has yielded disastrous outcomes, attributed mainly to the extensive redistribution of assets, income, and development opportunities resulting from the privatization and liberalization of foreign trade, mainly imports. The strengthening of the import economy, on the one hand, and the weakening of industry and the real sector, on the other, stimulated growth until 2008: approximately €157 billion has been invested in Serbia, primarily directed toward the import of products and services and the growth of supporting economic activities such as transportation, commerce, and the financial sector (Zeković et al., Citation2015). This has occurred alongside a significant deindustrialization process, which has been particularly severe in Serbia compared to other former socialist countries (Zeković & Perić, Citation2023). As a result, imports have served to finance industries in other countries, predominantly those in highly developed European economies such as Germany and Italy, contributing to their economic and political expansion toward the East.

The parallel process of economic reforms in preparation for the EU accession has facilitated the rapid expansion of private capital inflows, i.e., Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), especially in privatization-related projects, with the largest part of FDI directed to the banking and financial sector—an average of 36.9%–46.9% until 2008 (Hunya, Citation2009, p. 96). By 2005, the privatization was mostly completed with considerable failure (about 30% of failed privatizations). Increased inflows of FDI, remittances and credit were the main drivers of high Gross Domestic Product (GDP) rates between 2000 and 2008, with an average annual growth of 6.5%. The liberalization of economic policy, especially monetary policy (e.g., floating exchange rate), opened the way for the expansion and dominance of foreign banks in Serbia. This enabled lending “cheap money” (to companies) and increased individual consumer and housing loans. About 9.01% of households took loans in foreign currencies, and 4.7% took mixed loans in local currency (RSD). The considerable rise of housing and consumer loans until 2008 contributed to the growth of external debt, despite the fall in public debt (Dvorsky et al., Citation2010, p. 85), with an exceptionally high degree of currency substitution (dollarization or euroization): foreign cash and deposits related to total cash and deposits were 88% in 2009 (Becker et al., Citation2010; Dvorsky et al., Citation2010, p. 88).

The recuperation after the 2008 global crisis was slow and difficult. In political terms, Serbian semi-consolidated democracy (2010–2018) started to vanish so that since 2019, Serbia has been considered a “competitive authoritarian,” “transitional” or “hybrid” regime (between democracy and autocracy Freedom House, Citation2022). Accordingly, the evolution of urban policy in Serbia has been mostly influenced by the crisis of the welfare state, economy and social corporatism, the collapse of the socialist order, and the role of the state in the post-socialist transition (Vujošević et al., Citation2014). In the face of growing corruption, established institutions often cannot control the bureaucracy inherited from the socialist period, protect property, and support the actual rule of law (Perić, Citation2020b). Some institutional functions were taken over by powerful elites, who organized institutions according to their political interests. Inherited institutions in the post-socialist period were affected by economic and social shocks and implicitly enacted new rules (Zeković et al., Citation2015). The political elite shifts power to parties and individuals, often businessmen, leaving numerous institutions powerless. The elite is often considered the generator and driver of urban development and the creator of new rules, habits and procedures in institutions aimed at gaining various benefits (Zeković et al., Citation2020). State-led financialization of urban development in Serbia can be interpreted as a product of a weak market balance (supply and demand mechanism), with the state acting as a decision-maker/policy-creator, regulator, planner, investor, and controller informed by individual decisions (of international companies, private funds, domestic investors) without any social, institutional or other constraints.

As financial indicators (with primarily various financial, investment and macroeconomic variables) are difficult to observe separately from the indicators of urban real estate (residential and nonresidential, commercial real estate), it is useful to shed light on their strong structural connection and conditionality. Informed by the relevant body of literature on various dimensions on financialization (Aalbers, Citation2017, Citation2019, Citation2020; Becker et al., Citation2010), the systematic framework for the analysis of the financialization process has been introduced, comprising the following dimensions: (1) transition from a bank-based financial system toward a market-based one, (2) foreign financial inflows, (3) financialization of non-financial corporations, (4) financialization of housing and households, and (5) urban financialization. The results of the extended analysis of five dimensions of financialization applied in the Serbian case for the period between 2008 and 2021, including relevant indicators for each dimension, are presented and summarized in .

Table 1. Indicators of financialization in Serbia.

Urban financialization in Serbia: An initial insight

The urban financialization in Serbia has been fueled by growing interests of capital in the real estate sector. The financialization would have been almost impossible without the arrival of the world’s leading REITs and the investment of international capital in housing and other commercial properties. Urban financialization is the dominant and fastest-growing economic activity that uses new financial instruments and products. However, the introduction of new regulations in financial activities with an aim to neutralize the speculative tendencies on the market was largely absent, which is especially reflected in urban (re)development (Zeković & Maričić, Citation2022). The shift from entrepreneurial to increasingly financial forms of urban development through market-based financial instruments and the new shaping of social behaviors also contribute to the weakening of the participatory nature of urban governance (Perić, Citation2020a). Urban development emerges out of a mix of the mentioned dimensions of financialization.

In Q3 of 2021, about 35,000 purchases and sales on the real estate market in Serbia amounted to €1.5 billion (ca. €6 billion annually), 56% of which were apartments, 11% housing buildings, 8% construction land, 4% business space, and 2% business buildings (Republic Geodetic Authority [RGA], Citation2021). In the total turnover value on the housing market in 2021, sales in Belgrade dominated with 62.38%. The nominal and absolute residential property prices index shows relatively moderate volatility in Serbia (). However, it has changed in the last two years due to a sharp jump. Serbian real estate index DOMex indicates the stability of housing prices under state guarantee (assessment has included three quarters of the properties; Nacionalna korporacija za osiguranje stambenih kredita [NKOSK], Citation2021). The actual ability of Serbia to cope with the adverse effects of residential property price bubbles is limited. The property price-to-income ratio in Serbia has reached 14.99 (Numbeo, Citation2022), especially in Belgrade (21.19), Niš (12.88) and Novi Sad (14.87). The indicator of mortgages as a share of the income has above-average values in Belgrade (154.66%) and below-average in Niš (91.61%) and Novi Sad (104.73%). However, Belgrade has the lowest loan affordability index, while more favorable indices have Novi Sad and Niš.

Urban financialization in Belgrade: The case study of the Belgrade Waterfront megaproject

Urban (re)development has been for a long time on the tail of financial capital, however, the changes in the structure of building provisions (supply-side) have embedded property development more deeply into the global financial markets. Both states and international financial institutions and companies have boosted urban (re)development through large urban development projects, also known as flagship projects or megaprojects, by increasing the influence of the corporate sector in the financialization of urban properties. The mobility of financial capital has also been improved by modern urban design and strategies of smart cities, with general consent for pro-development regulatory changes. Financial capital investments in large urban development projects (real estate projects) are, finally, increasingly based on sustainability.

Notably, financialization includes different aspects of extracting urban values, such as: “invisible” extraction, resulting from the invisible hand of the market (emphasis alluding to Adam Smith), corresponding mainly to the Anglo-American financial logic of advanced capitalist societies; “visible” hand of the state that supports financialization, referring to a stronger intervention of the public sector in the market; and “the long arm of finance,” addressing urban development in transitional societies beyond the regulated capital markets (Hendrikse, Citation2016). Such classification aligns well with the specificities of urban megaproject development in various socio-spatial settings. Namely, Western liberal democracies with a strong capitalist outlook marginalize governmental support into megaproject development; more conservative (once welfare) states still tend to pursue a deliberative process of defining common goods and public interest; the Global South and post-socialist Europe build radical feedback between the state and dominant financial actors—through strengthening “private governance,” and a “top-top,” i.e., a regulationist state-led approach, respectively (Perić & Maruna, Citation2022, p. 1; Zeković & Maričić, Citation2022). Reflecting upon the latter, post-socialist urban megaprojects point to “social distortions caused by the superior position of the private sector, opportunism within government structures, lack of professional expertise and, finally, neglect of the public interest” (Perić, Citation2020a, p. 213).

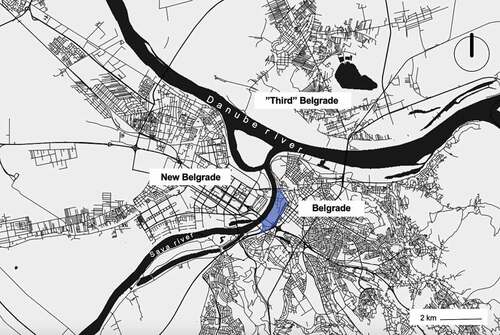

For the first time, the BW megaproject was announced as the flagship project in 2012, immediately after the then-largest opposition party won the elections with a great majority of voices. After three years of the political propaganda under the motto “fast-lane approach to investors” (Zeković & Maričić, Citation2022), the cornerstone for its future development was set in September 2015, designating the start of fulfilling a grand political and urban megaproject vision financed by Eagle Hills, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) investor, with considerable subsidies provided by the Serbian government. The BW megaproject covers an almost 90-ha area close to the confluence of two rivers and the historical core of the city of Belgrade (), providing 2 million square meters of exclusive residential, commercial and office space. The professionals claim the project a problematic from both the urban design and urban planning point of view, i.e., it contributes to ruining Belgrade’s identity and questions the resilience of formal planning procedures under the neoliberal trend of urban development (Maruna, Citation2015). Citizens point out the need for more transparency in projects of such scale (Perić, Citation2020a). However, politicians, regarded as the vital factor for the success of financialized real estate development in post-socialist societies (Becker et al., Citation2010), overrule all the remarks by experts and the public to praise the BW megaproject as the role model of contemporary urban development () assigning it an attribute of the project of “national importance” (Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 1/Citation2012) (although the project included foreign developers as the main financial partner to the Serbian government). Taking this statement critically, i.e., addressing the BW criticisms such as zero accountability in decision-making, weak monitoring and control systems, and rudimentary mechanisms for evaluating social, economic, and environmental impacts (Zeković et al., Citation2018), and informed by the regulationist approach to financialization in post-socialist societies (Aalbers, Citation2019; Becker et al., Citation2010), the following subsections elucidate various mechanisms of financialized urban development, such as: deregulation as an enabler of legitimate collaboration between high-level politicians and foreign developers; the modification of planning procedures to transform planning into the tool for creating financial assets; and civic response against a dominantly financialized narrative.

Figure 1. The position of the Belgrade Waterfront project within the Belgrade city pattern.

Figure 2. The Belgrade Waterfront project (model).

The joint public-private effort in a quest for deregulation

Since the very first idea on the BW megaproject in 2012, it was promoted as the “best practice” example for the future urban development of Belgrade. Over the course of next 2 years, the high-level political representatives have been systematically revealing the peculiar nature of what they considered “the best” mechanism for attracting new investments: there were no tenders in choosing the developers, and the planning documentation was set as flexible, i.e., following the new fast-track adopted legislation. Selected upon direct negotiations with the Serbian government, i.e., without international bidding, the Abu Dhabi-based Eagle Hills got numerous subventions to invest in BW. These were covered by the Law Ratifying the Agreement on Cooperation between the Government of the Republic of Serbia and the Government of the United Arab Emirates (Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 3/Citation2013), which later served to legitimize the agreements made without an open tender procedure and open lucrative opportunities for monetizing the public land. This Law stipulates that agreements, contracts, programs and projects concluded in accordance with the agreement are not subject to public procurement, public tenders or competitions envisaged by Serbian legislation (Zeković & Maričić, Citation2022).

First, the Serbian state obliged itself to secure the land decontamination, remove the obsolete infrastructure in the area and provide the new one, and, finally, lease the land to the developer for 99 years (Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 3/Citation2013). Notably, the law excludes charging any fee to Eagle Hills during leasing the land, converting leasehold into freehold upon constructing the building stock and a month after a use-permit is obtained, and transferring the freehold to other parties. On top of this, Serbia was obliged to adopt any changes to other laws and regulations that were desirable for foreign investors. For example, based on this piece of legislation and the amended Law on Planning and Construction (Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 132/Citation2014), a Joint Venture Agreement was signed in April 2015. Serbian government founded the common Serbian-UAE company (Beograd na vodi/Belgrade Waterfront, LLC) for the realization of the BW project with a real estate company from the UAE (Belgrade Waterfront Capital Investment, LLC) as a strategic partner. Belgrade Waterfront LLC has been composed of both Eagle Hills and Serbian experts in charge of operations on the Belgrade Waterfront project (Perić, Citation2020b). Despite the obvious imbalance of the power geometries between the two parties, the dominant political narrative to the public was highly financialized: “one must respect other people’ money” and “we cannot joke about someone’s three billion dollars” (Blic, Citation2014b).

The instrument considered a distinct example of deregulation is the so-called Lex Specialis, i.e., the Law on Establishing the Public Interest and Special Procedures of Expropriation and the Issuance of Building Permit for the Project Belgrade Waterfront (Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 34/Citation2015). The Anti-Corruption Agency of Serbia (ACAS, Citation2014) analyzed the corruption risks in the Lex Specialis and gave a negative opinion on enacting it for the purpose of only one project. The law allows land expropriation for the commercial project only in the interest of Eagle Hills, with the national interest seen in creating new workplaces and assigning the construction work to the Serbian subcontractors (Perić & D’hondt, Citation2022, p. 302). Accordingly, it is not apparent how the highly commercial BW project can preserve and be in the public interest, nor how this works in practice, as specific regulations on implementing the mentioned law do not exist (Zeković & Maričić, Citation2022). Missing directives for transposing the law allow different malversations infringing the public interest.

Finally, although the financialization of the state can include various tiers of public authorities (Aalbers, Citation2019), in contrast to megaprojects in developed societies where local politicians take a key role in steering the development with financial actors (Fainstein, Citation2008; Machiels et al., Citation2021), the post-socialist states favor the national politics (Becker et al., Citation2010). Namely, the voice of the Mayor of Belgrade was only heard because he belonged to the same ruling political regime (Maruna, Citation2015), making any bottom-up deliberation subordinate to the higher goal of using the (public!) land as a financial asset. However, according to Joint Venture Agreement, the Serbian state is far more inferior to the strategic partner, Eagle Hills and his leading representative, Sheikh Mohamed Alabbar, with the backup support of the UAE government through bilateral (UAE and Serbia) cooperation agreements on different issues (BW, agriculture, air-transport). Hence, the Serbian national politics’ withdrawal from protecting social values seen in the greater power of the contract over the law and using land as a source of speculative financial growth exemplifies the trend of “authoritarian entrepreneurialism” or “capital urbanization” (Perić & D’hondt, Citation2022, p. 302).

Urban planners between the professional norms and neoliberal reality

Although the Belgrade Waterfront project was formally designated as a project of national interest, in media was glorified as “Allabar’s project” (Blic, Citation2014a). Such narrowing of the entire development and, in final stance, tailoring to individual interests posed an immense burden on other interested and affected parties. However, the professionals’ response was mixed (Perić & Maruna, Citation2022): the voices of planners and architects, e.g., the Architecture Committee of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, the Academy of Architecture of Serbia and some eminent individuals, were either weak, i.e., not pointing to the failures of the planning procedure, but considered more functional constraints, or confusing, as the president of the Academy of Architecture of Serbia was in favor of the project described by his fellow academicians as the “world’s largest illegal construction site” (Blic, Citation2015). The only actors acting as facilitators in the BW megaproject elaboration were the public planning bodies close to the government (Zeković & Maričić, Citation2022). The preparation process of the critical planning and legal instruments was as follows.

In the regular spatial planning practice, the project elaboration follows the rules and parameters given in the plan. However, in the case of the BW megaproject, the international architectural office (Skidmore, Owings & Merrill—SOM Architects) prepared the preliminary design project to serve as a base for the elaboration of the urban plan. Accordingly, the Urban Planning Institute, the principal public urban planning office in Belgrade, created the Belgrade Waterfront Concept Masterplan in July 2014 (Perić, Citation2020a). As it was significantly different to the nature of the official Master Plan of Belgrade (Zeković et al., Citation2018), it was ex-post adopted as Amendments to the Master Plan of Belgrade (Official Gazette of the City of Belgrade 70/Citation2014) by the city assembly in September 2014.

However, as the Master Plan of Belgrade, the highest-tier urban plan, can be implemented only through second-tier regulatory plans (which is a time-consuming procedure that demands more local coordination, public debates and approvals), in June 2014, a month before the BW “masterplan” was prepared, the Government decided to create the special spatial plan. Namely, the Spatial Plan for the Area of Specific Use is, according to the planning law (Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 1/Citation2012), created only (1) for non-urban areas of particular importance (i.e., areas with natural, cultural-historical values; exploitation of mineral raw materials; areas of tourist potentials; hydro-potential areas, etc.), and (2) in accordance with the higher-tier plans (i.e., regional or national spatial plans). Despite the lack of higher-tier plans and the fact that the BW area is undoubtedly urban, it was decided to proceed with preparing the special spatial plan (Perić, Citation2020a).

The legal basis for such a decision was found in the Regulations on the Content, Method and Procedure of Drafting Planning Documents instead in the planning law. The Regulations indeed contain a provision according to which the Serbian government (as the authority responsible for the adoption of spatial plans as the highest tier, i.e., national planning instruments) can decide at its discretion to proceed with the preparation of this type of planning document. However, the then-valid planning law did not recognize this right. In the hierarchy of planning instruments, the provisions of the regulations cannot be above the provisions of the law. Accordingly, this is clear evidence of “decisionism”—the rule of the political establishment through by-laws outside the law (Zeković & Maričić, Citation2022).

The Republic Agency for Spatial Planning (RASP) prepared this special spatial plan following the Belgrade Waterfront Concept Masterplan. For years, this state-owned agency was responsible for creating spatial plans. However, once the document was made (in a record timeframe, only five months after the decision was issued), the RASP was abolished in December 2014 according to the new planning law—Law on Planning and Construction (Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 132/Citation2014), and all its tasks were undertaken by the Serbian Ministry of Construction, Transport and Infrastructure. Hence, the plan-making and its expert control were united into one governmental body, thus representing a “direct conflict of interests, centralization of power, and lack of transparency in the BW process (Perić, Citation2020a, p. 224). Finally, to address the fact that the new spatial plan for BW had no backing in law, as it waived the requirement to hold an international design competition for the waterfront area and changed the land use rules (Perić & Maruna, Citation2022), the newly updated planning law included two new special zones—areas with tourism potential and areas of national importance—added under the category of the Spatial Plan for the Area of Specific Use. The spatial plan for BW was made legitimate and was adopted in January 2015 (Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 7/Citation2015). Briefly put, “politicization of planning” (Grange, Citation2017) makes planners loyal to neoliberal politics of “decisionism” (Zeković & Maričić, Citation2022) that takes non-grounded decisions often without any analysis, based on by-laws (from the high-level politicians), and so the planning becomes a mere tool in the hand of financialized urban development.

Civic voices against top-top decisions

Under the circumstances of the intertwined interests between the state representatives and private developers in financializing real estate, on the one hand, and powerless experts whose professional norms become subordinated to material values provided by land as the financial asset, on the other, social norms can be seen as a corrective factor in urban financialization (Becker et al., Citation2010). In the case of the BW megaproject development, the civil sector played a significant role in elucidating all the deregulation mechanisms and distortions of the legal rules. Represented by two NGOs—“Don’t let Belgrade d(r)own!” (Ne da(vi)mo Beograd!) and the Ministry of Space (Ministarstvo prostora)—the civil sector organized a range of activities.

As a reaction to the proposed amendments to the Master Plan of Belgrade, the citizens of Belgrade made over 3,000 complaints. At the same time, more than 200 people actively participated in the procedure of public viewing, pointing out all kinds of irregularities proposed by the master plan amendments. All complaints were rejected or only superficially taken into consideration, so the Amendments to the Master Plan of Belgrade (Official Gazette of the City of Belgrade 70/Citation2014) were verified in September 2014 (Perić, Citation2020b). Despite this, the civil sector continued with public discussions. The open debate with academics, “What is hidden beneath the surface of the ‘Belgrade Waterfront,’” was held in October 2014 parallelly to the procedure of spatial plan-making.

A month later, the creative performance “Operation Lifebelt” was organized during the public meeting on the approval of the Spatial Plan for the Area of Specific Use, with the activists trying to attend to the shortcomings as presented in the plan. Again, the political structures embodied in the planning commission turned a deaf ear to citizens’ calls, which resulted in the adoption of the preliminary version of the spatial plan in January 2015, thus excluding all public remarks (Perić & D’hondt, Citation2022, p. 297).

Even after the start of construction of the BW project in September 2015, citizens regularly organized protests in 2016 and 2017. The latter was mainly due to the peculiar demolitions (that happened during the night executed by no officially registered companies for such activities) of legal and illegal facilities in the Savamala quarter, organized due to the need to continue the BW construction (Perić, Citation2020a). The public revolt, however, did not prevent the further development of the area. Currently (2023), an array of housing facilities, a shopping mall, a tower, a great deal of road infrastructure and public open spaces have been finalized and open for the public (). It seems that the spatial planning paradigm and social norms, in general, have been affected dramatically by the illiberal democracy and ad-hoc and opportunist state approaches toward securing investments for major (re)development projects.

Figure 3. The Belgrade Waterfront project (implementation, December 2022).

Conclusions

This paper provides evidence about the process of urban financialization in Serbia by intertwining the global and national financialization indicators and urban real estate indicators and elucidating the BW case through decision-making, planning and governance linked with different dimensions of financialization. As in the rest of the European (semi)periphery (Aalbers, Citation2020; Becker et al., Citation2010; Büdenbender & Aalbers, Citation2019) faced with the privatization of the state and social fund, the financialization of urban land in Serbia contributes to massive changes, such as the creation of new urban identity, real estate bubble, deindustrialization, the intensive transformation of the urban core, and the rise of socio-spatial inequalities. In other words, urban financialization in Serbia is far from the mainstream approach: a critical standpoint is necessary to fully understand the effect of financialization as a tool to shape urban development.

The financialization of “the urban” in the Serbian context is much more than a mere implementation of global trends aimed at increasing benefits and returns to the most influential stakeholders/shareholders. On the contrary, if the global neoliberal trends are to find fruitful ground in Serbia, financialization must enter into the institutional and decision-making structure not only through the changed policies and policy narratives in support of the fast-track decision-making (Waldron, Citation2019; Weber, Citation2010), but also in the overall public discourse, where the financialization is to be presented as a tool for “benefitting all” despite the contrary effects, such as the distortion of the public interest, as happening in urban development practice. Such narrative and attempts to implement the financial instruments that fit only the financial market and financial institutions at the expense of all other stakeholders and social norms are based on the logic of exception: through transforming the process of decision-making, and respective norms and standards, the state uses its discretionary power to apply the “exception principle,” thus incrementally leading to land grabbing, extraction of the land value and treating land as a tradable income-yielding asset. By establishing the financialization under the patronage of the state and international investors, the decision-making, urban planning and governance evolve into the top-top approach, violating different social norms. Briefly put, the overwhelming interconnectedness between the forms of capital accumulation and legal and social norms makes the Serbian urban financialization case well-suited to the regulationist learnings, focusing on the role of state vis-à-vis capital, the changes in regulation to enable financialization and the social and political contestation of such changes. Hence, urban financialization in Serbia applies a more nuanced and complex approach that serves as a powerful tool to observe the nature and all maleficence of the current spatial planning decision-making and urban governance. Some critical findings interconnecting global macroeconomic trends and the micro level of BW urban megaproject are given below.

First, the empirical analysis provides an insight into the complex nature of the relationship between the financialization indicators at the national level and urban real estate indicators, i.e., their strong structural and dynamic conditionality. The findings indicate huge creditism, growth of total external debt, public debt, increasing indebtedness of the private sector and households (mainly due to the growth of housing loans in recent years) and pronounced volatility in real estate prices as a consequence of financialization, i.e., transformations of the socioeconomic system and foreign financial inflows.

Furthermore, the research provides insight into the relationship between finance, macroeconomic trends and urban (re)development. Real estate investments are usually introduced into public policies and plans, in which property development is often imperatively in accordance with the investors’ interests (Guironnet & Halbert, Citation2014), while the negative sides of financialization are reflected at the expense of the erosion of public interests and goods (Horodecka & Zuk, Citation2021). The findings indicate a close connection between the intertwining of the global financial and macroeconomic trends and the urban (re)development process, i.e., the financial capital investments are increasingly relying on real estate markets and large urban projects, as illustrated by the findings on the BW megaproject. Financial capital investors acquire different segments of urban structures, primarily commercial properties, as “tradable income-yielding assets.” Urban financialization implies a new framework in which the authorities rely heavily on major players in the real estate market and public resources. Therefore, the expectations of financial capital investors are directly related to monetary, credit, fiscal, developmental, and urban policy. Cooperation with state institutions aims to facilitate the conditions for lending and the sale of commercial and residential real estate with the protection and guarantees of the state.

Finally, the financialization of urban development, as indicated in the BW megaproject case, shows that the institutional framework became the backbone for anchoring global financial capital in the capital of Serbia, despite the still transitional settings characterized by a mixture of past and present and old and new approaches, mechanisms and instruments. The BW megaproject case introduces additional arguments about the nature of subordinate financialization in the post-social context of Serbia (e.g., by considering the transformation of the institutional framework from state socialism to market capitalism), a better understanding of the incorporation of capital in the built environment, and an empirical evidence of how political actors shape the national trajectory of financialization of the urban environment.

To conclude, institutional changes are needed to reorient socioeconomic perceptions from the optics of financialization to the preservation of public goods and sustainable urban development. Solutions should provide standards for the better functioning of financial capital in urban development and facilitate a dialogue between different financial interests. Hence, it is necessary to find new mechanisms to diminish the room for social risk and embezzlement as well as the irrational urban real estate market boom, followed by speculative bubbles, collapse, debt growth and systemic crises. This seems an ambitious task for research on financialization and its practical implementation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Slavka Zeković

Slavka Zeković is principal research fellow at the Institute of Architecture and Urban & Spatial Planning of Serbia, Belgrade.

Ana Perić

Ana Perić is assistant professor in the UCD School of Architecture, Planning and Environmental Policy, and Senior Research Associate at the Department of Urban Planning, University of Belgrade.

Miroljub Hadžić

Miroljub Hadžić is professor at the Faculty of Business at the Singidunum University, Belgrade.

References

- Aalbers, M. (2017). Corporate financialization. In D. Richardson, N. Castree, M. F. Goodchild, A. Kobayashi, W. Liu, & R. A. Marston (Eds.), International encyclopedia of geography: People, the earth, environment, and technology (pp. 1–11). John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.

- Aalbers, M. (2019). Financialization. In D. Richardson, N. Castree, M. F. Goodchild, A. Kobayashi, W. Liu, & R. A. Marston (Eds.), International encyclopedia of geography (pp. 1–12). John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.

- Aalbers, M. (2020). Financial geography III: The financialization of the city. Progress in Human Geography, 44(3), 595–607. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519853922

- ACAS. (2014). Opinion on estimation of the risk of corruption in the provisions of the draft the law on establishing the public interest and special procedures of expropriation and the issuance of building permit for the project Belgrade Waterfront (in Serbian). http://www.acas.rs/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Misljenje-o-Predlogu-zakona-o-Beogradu-na-vodi-final-1.pdf

- Adisson, F. (2019). The transformation of urban policy by financial valuations methods. The case of the urban development projects in Italy. Espaces et societes, 174(3), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.3917/esp.174.0087

- Alexandri, G., & Janoschka, M. (2017). Who loses and who wins in a housing crisis? Lessons from Spain and Greece for a nuanced understanding of dispossession. Housing Policy Debate, 21(1), 117–134.

- Anguelov, D., Leitner, H., & Sheppard, E. (2018). Engineering the financialization of urban entrepreneurialism: The JESSICA urban development initiative in the European Union. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 42(4), 573–593. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12590

- Bank of International Settlements. (2022a). Residential property prices: detailed series (nominal). https://www.bis.org/statistics/pp_detailed.htm

- Bank of International Settlements. (2022b). Total credit to the non-financial sector (core debt). https://stats.bis.org/statx/srs/table/f1.1

- Bartlett, W., & Prica, I. (2013). The deepening crisis in the European super-periphery. Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, 15(4), 367–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/19448953.2013.844587

- Becker, J., Jäger, J., Leubolt, B., & Weissenbacher, R. (2010). Peripheral financialization and vulnerability to crisis: A regulationist perspective. Competition & Change, 14(3–4), 225–247. https://doi.org/10.1179/102452910X12837703615337

- BELEX (Beogradska berza). (2022). Annual statistics. https://www.belex.rs/eng/trgovanje/izvestaj/godisnji

- Blic. (2014a, January 9). Vučić: Al Abar u Beograd na vodi ulaže 3,1 milijardu dolara [Vučić: Alabbar invests $ 3.1 billion in Belgrade Waterfront]. https://www.blic.rs/vesti/ekonomija/vucic-al-abar-u-beograd-na-vodi-ulaze-31-milijardudolara/2wznz6j

- Blic. (2014b, January 20). Vućić o “Beogradu na vodi”: Posao će biti završen [Vučić on “Belgrade Waterfront”: Work will be completed]. https://www.blic.rs/vesti/politika/vucic-o-beogradu-na-vodi-posao-ce-biti-zavrsen/bex1vzv

- Blic. (2015, March 6). Arhitekte: Hitno obustaviti projekat Beograd na vodi [Architects: Urgently suspend the Belgrade Waterfront project]. https://www.blic.rs/vesti/beograd/arhitekte-hitno-obustaviti-projekat-beograd-na-vodi/6y1zc7m

- Brenner, N. (1999). Globalisation as reterritorialisation: The re-scaling of urban governance in the European Union. Urban Studies, 36(3), 431–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098993466

- Büdenbender, M., & Aalbers, M. (2019). How subordinate financialization shapes urban development: The rise and fall of Warsaw’s Służewiec business district. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 43(4), 666–684. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12791

- CEIC. (2021). Serbia market capitalization: % of GDP. https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/serbia/market-capitalization–nominal-gdp

- Correa, E., Vidal, G., & Marshall, W. (2012). Financialization in Mexico: Trajectory and limits. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 35(2), 255–275. https://doi.org/10.2753/PKE0160-3477350205

- Demir, F. (2009). Financial liberalization, private investment and portfolio choice: Financialization of real sectors in emerging markets. Journal of Development Economics, 88(2), 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.04.002

- Dvorsky, S., Scheiber, T., & Stix, H. (2010). Real effects of crisis have reached CESEE households: Euro survey shows dampened savings and changes in borrowing behavior. Focus on European Economic Integration, 2, 79–90.

- Epstein, G. A. (2005). Introduction: Financialization and the world economy. In G. A. Epstein (Ed.), Financialization and the world economy (pp. 3–16). Edward Elgar.

- Eurostat. (2021). Online data code (bop_c6a Eurostat credit).

- Fainstein, S. S. (2008). Mega-projects in New York, London and Amsterdam. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32(4), 768–785. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2008.00826.x

- Foster, J. B. (2007, April 1). The financialization of capitalism. Monthly Review, 58 (11), 1. https://monthlyreview.org/2007/04/01/the-financialization-of-capitalism/

- Freedom House. (2022, July 3). Nations in transit – Serbia country report. https://freedomhouse.org/country/serbia/nations-transit/2022

- French, S., Leyshon, A., & Wainwright, T. (2011). Financializing space, spacing financialization. Progress in Human Geography, 35(6), 798–819. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510396749

- Gabor, D. V. (2012). The road to financialization in Central and Eastern Europe: The early policies and politics of stabilizing transition. Review of Political Economy, 24(2), 227–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/09538259.2012.664333

- Georgia, A., & Janoschka, M. (2017). Who loses and who wins in a housing crisis? Lessons from Spain and Greece for a nuanced understanding of dispossession. Housing Policy Debate, 21(1), 117–134.

- Göler, D. (2005). South-East Europe as European periphery? Empirical and theoretical aspects. In Serbia and modern processes in Europe and the world (pp. 137–142). University of Belgrade, Faculty of Geography.

- Grange, K. (2017). Planners – A silenced profession? The politicisation of planning and the need for fearless speech. Planning Theory, 16(3), 275–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095215626465

- Grubbauer, M., & Čamprag, N. (2019). Urban megaprojects, nation-state politics and regulatory capitalism in Central and Eastern Europe: The Belgrade Waterfront project. Urban Studies, 56(4), 649–671. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018757663

- Guironnet, A., Attuyer, K., & Halbert, L. (2016). Building cities on financial assets: The financialization of property markets and its implications for city governments in the Paris city-region. Urban Studies, 53(7), 1442–1464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015576474

- Guironnet, A., & Halbert, L. (2014). The financialization of urban development projects: Concepts, processes, and implications. Document de travail du LATTS - Working Paper 14–04. http://hal-enpc.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01097192.

- Haila, A. (1988). Land as a financial asset: The theory of urban rent as a mirror of economic transformation. Antipode, 20(2), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.1988.tb00170.x

- Hendrikse, R. (2016). The long arm of finance: Exploring the unlikely financialization of governments and public institutions [Doctoral dissertation, Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Amsterdam Institute for Social Science Research]. https://dare.uva.nl/search?identifier=07dd1c7c-ffba-42db-910c-f6e79a5cd3b4

- Horodecka, A., & Zuk, A. (2021). Financialization and the erosion of the common good. Studia humana, 10(2), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.2478/sh-2021-0007

- Hunya, G. (2009). WIIW database on foreign direct investment in Central, East and Southeast Europe. The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies.

- Kaika, M., & Ruggero, L. (2016). Land financialization as a ‘lived’ process: The transformation of Milan’s Bicocca by Pirelli. European Urban and Regional Studies, 23(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776413484166

- Karwowski, E., & Stockhammer, E. (2016). Financialisation in emerging economies: A systematic overview and comparison with Anglo-Saxon economies. Working Paper 1616, Post Keynesian Economics Study Group. http://www.postkeynesian.net/downloads/working-papers/PKWP1616_haHHGZM.pdf

- Koelemaij, J., & Janković, S. (2020). Behind the frontline of the Belgrade Waterfront: A reconstruction of the early implementation phase of a transnational real estate development project. In J. Petrović & V. Backović (Eds.), Experiencing postsocialist capitalism: Urban changes and challenges in Serbia (pp. 45–66). University of Belgrade, Faculty of Philosophy.

- Krippner, G. R. (2005). The financialization of the American economy. Socio-Economic Review, 3(2), 173–208. https://doi.org/10.1093/SER/mwi008

- Kubeš, J., & Kovacs, Z. (2020). The kaleidoscope of gentrification in post-socialist cities. Urban Studies, 57(13), 2591–2611. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019889257

- Lake, R. W. (2015). The financialization of urban policy in the age of Obama. Journal of Urban Affairs, 37(1), 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12167

- Lapavitsas, C. (2013). The financialization of capitalism: ‘Profiting without producing.’ City, 17(6), 792–805. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2013.853865

- Levine, R. (1997). Financial development and economic growth: Views and agenda. Journal of Economic Literature, 35(2), 688–726.

- Machala, B., & Koelemaij, J. (2019). Post-socialist urban futures: Decision-making dynamics behind large-scale urban waterfront development in Belgrade and Bratislava. Urban Planning, 4(4), 6–17. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v4i4.2261

- Machiels, T., Compernolle, T., & Coppens, T. (2021). Explaining uncertainty avoidance in megaprojects: Resource constraints, strategic behaviour, or institutions? Planning Theory & Practice, 22(4), 537–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2021.1944659

- Maruna, M. (2015). Can planning solutions be evaluated without insight into the process of their creation? In M. Schrenk, V. Popovich, P. Zeile, P. Elisei, & C. Beyer (Eds.), Plan together–right now–overall – proceedings of the REAL CORP 2015 conference (pp. 121–132). REAL CORP.

- Mikuš, M. (2019). Financialization of the state in postsocialist East-Central Europe: Conceptualization and operationalization. GEOFIN Working Paper No. 3, Trinity College Dublin. https://geofinresearch.eu/outputs/working-papers/

- Ministry of Finance of Serbia. (2021). Public finance bulletin, 4/2021 – Bilten javnih finansija, 4/2021 (in Serbian).

- Nacionalna korporacija za osiguranje stambenih kredita. (2021). Domex index in Serbia. https://www.nkosk.rs/cir/domex–indeks-cena-nepokretnosti-nacionalne-korporacije-za-osiguranje-stambenih-kredita/

- National Bank of Serbia. (2010). Annual financial stability report.

- National Bank of Serbia. (2014). Annual financial stability report.

- National Bank of Serbia. (2020). Annual financial stability report.

- National Bank of Serbia. (2021b). Report on the dinarisation of the Serbian financial system.

- National Bank of Serbia. (2021c). Housing loans - review of annual effective rates.

- National Bank of Serbia. (2021d). Annual financial stability report.

- National Bank of Serbia. (2022). Macro-economic developments in Serbia.

- Numbeo. (2022). Property prices in Serbia. https://www.numbeo.com/property-investment/country_result.jsp?country=Serbia

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 1/2012. Ordinance on the Methodology and Procedures on Realization the Projects of Importance for the Republic of Serbia.

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 3/2013. Law Ratifying the Agreement on Cooperation between the Government of the Republic of Serbia and the Government of United Arab Emirates.

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 132/2014. Law on Planning and Construction.

- Official Gazette of the City of Belgrade 70/2014. Amendments on the Master Plan of Belgrade.

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 34/2015. Lex Specialis – Law Establishing Public Interest and Special Expropriation and Construction Permitting Procedures for the Belgrade Waterfront Project.

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 7/2015. Regulation on the Spatial Plan for the Area of Specific Use for the Waterfront of the River Sava for the Belgrade Waterfront Project.

- Orhangazi, Ö. (2008). Financialisation and capital accumulation in the non-financial corporate sector: A theoretical and empirical investigation on the US economy: 1973–2003. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 32(6), 863–886. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/ben009