?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Nowadays, cities’ involvement in sustainability efforts is becoming increasingly important. Of particular relevance are the horizontal networks and international initiatives that promote sustainability actions and help the participating cities to exchange knowledge and experience. Participation in such initiatives and the degree of involvement is largely determined by the political leadership of cities. This paper investigates the political determinants of applying for a European sustainability initiative, the European Green Capital Award, using binary logistic regression with data on the real applicants and control cities, up to the round of 2024. The results show that cities with left-wing leadership and more green party representatives in the city council are more willing to apply for the award. The finalist status in the competition was positively influenced by the city council’s environment-friendly attitude and the experience of previous applications.

Introduction

The vast majority of the world’s population now lives in cities, where various environmental, social and economic problems are concentrated, making the challenges of urban governance a central issue (Parnell, Citation2016). However, the development of cities is not just a part of climate problem, it can also be part of the solution (Kamal-Chaoui & Robert, Citation2009). The importance of action by cities was inspired by Agenda 21 (Zeemering, Citation2012), which encouraged cities around the world to adopt sustainability principles through the Local Agenda 21 processes. Sustainable cities are defined by Nijkamp and Perrels (Citation1994, p. 4) as cities “where socio-economic interests are brought together in harmony (co-evolution) with environmental and energy concerns in order to ensure continuity in change.” Based on the concept of sustainable cities, there is a growing interest in the contribution that cities can make to address global environmental challenges, and in particular, the fight against climate change (Bulkeley & Betsill, Citation2003). Tackling climate change is not limited to the national and international policy-making arena, but it is also a critical urban issue (Bulkeley & Betsill, Citation2013; Hughes, Citation2019). The role and potential of local governments and local initiatives is particularly important when states and international organizations are ineffective and stagnant in delivering appropriate policies (Wolfram et al., Citation2019). Most research agrees that cities play a key role in climate change mitigation and adaptation (Da Cruz et al., Citation2019; Dent et al., Citation2016; McPhearson et al., Citation2016). As a result, more and more municipal governments are now taking up the cause of climate change and in connection, states delegate certain tasks to the municipal level (van der Heijden, Citation2017). This gives the local level autonomy to pursue environmental policies that fit into the national framework but are tailored to local circumstances (van der Heijden, Citation2019). City governments are also an important factor in the advancement of the principles of sustainability (Zeemering, Citation2012). Local sustainability initiatives have emerged in response to the recognition of the importance of sustainability actions (Saha, Citation2009). However, there is considerable variation in the level of commitment and interest in sustainability across cities (Bulkeley & Betsill, Citation2013). The variation is caused by both the level of local government activity and the quality of urban climate governance. Scholars clearly identified several factors which enable effective urban climate action (van der Heijden, Citation2019). According to Jagers and Stripple (Citation2003, p. 385), climate governance refers to “all purposeful mechanisms and measures aimed at steering social systems toward preventing, mitigating, or adopting to the risks posed by climate change.”

This broad concept includes all actors that have some influence on decision-making, i.e., non-state actors as well as local, national and supranational political actors, which are interconnected and characterized by a variety of interaction dynamics (Ehnert et al., Citation2018). The phenomenon is described by the model of multi-level governance, which state that “decision-making competencies are shared by actors at different levels” (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2001, p. 3). Policy discussions about environmental issues that straddle levels of government and the range of institutional actors involved in making and executing policy fall within the concept of multi-level climate governance (Bulkeley & Betsill, Citation2003). In considering urban sustainability issues, researchers need to look beyond the local level and involve other governance levels (Ehnert et al., Citation2018), as they provide ideas, knowledge and resources that contribute to effective urban climate governance (Hofstad & Vedeld, Citation2021). Tackling climate change requires long-term commitment and investment by decision-makers and city managers (Sennett, Citation2014). This process involves adjusting and adapting governance strategies over time, as cities learn more about the challenges and uncertainties (Hughes, Citation2019). However, these investments may not be possible without the help and support of national and transnational governments, which may ultimately limit the implementation of innovations in urban governance (Da Cruz et al., Citation2019; Hughes, Citation2019).

European cities also have a regional actor, the European Union (EU), to take into account in climate governance. An additional level usually allows local actors to rely on it to counterbalance and compensate for the inaction or ignorance of one (e.g., national) level (Ehnert et al., Citation2018). EU support is important for cities even if national climate policies are relatively strong (Heikkinen, Citation2022). The EU has become a key partner in obtaining funding and collaborating on policy projects (Verdonk, Citation2014). Kern and Bulkeley (Citation2009) identified three dimensions of the Europeanization of local authorities. Top-down Europeanization involves cities becoming increasingly affected by EU regulations, with closer links between local authorities and EU institutions. The bottom-up form has been shaped by the growing importance of EU initiatives for the local sphere, leading to the creation of transnational organizations of cities. Lastly, horizontal Europeanization can be observed through mutual learning, information exchange and joint problem-solving. In a horizontal direction of multi-level governance, it is mainly the motivation of local activities that is important (Lee & Koski, Citation2015). Transnational horizontal European networks provide opportunity for cities to challenge the state-centric structure of the EU and to implement the ideology of European municipalism through cooperative links between municipalities (Mocca, Citation2021). Formalized city networks have also appeared in the field of urban sustainability (Acuto, Citation2016). Networking provides an avenue for cities to contribute to global change and influence sustainability policies at different levels (Heikkinen, Citation2022). However, participation in those horizontal partnerships does not necessarily imply a high level of urban environmental quality (Mocca, Citation2017). In line with the expansion in the number of networks, European city-to-city competitions have also become increasingly popular, bringing together different local activities in cities and rewarding them with awards (Kern & Bulkeley, Citation2009). One such example is the European Green Capital Award (EGCA), which rewards cities for their sustainability and environmental efforts. The prize is awarded by the European Commission on the basis of a centrally defined set of criteria, based on several environmental indicators, in a two-round competition (Gudmundsson, Citation2015). Cities with more than 100,000 inhabitantsFootnote1 from EU member states and European Economic Area countries are eligible, but previous winners are no longer considered (European Commission, Citation2021).

The main question of the study is how the political composition of the local city government is related to the fact of the EGCA application and the outcome of the bid. The role of political parties and their associated ideologies on environmental sustainability has been studied in previous research mainly from a national and international perspective (Bossuyt & Savini, Citation2018). For instance, Neumayer (Citation2003) found a link between left-wing parties and pollution reduction, Scruggs (Citation1999) explored the link between left-wing parties and good environmental indicators, while Biresselioğlu and Karaibrahimoğlu (Citation2012) pointed to the contribution of left-wing parties and Nicolli and Vona (Citation2019) to the contribution of green parties to the increasing share of renewable energy. At the urban level, the role of individual political parties is still considered irrelevant both for planners and the empirical literature on urban development (Bulkeley et al., Citation2013; Savini, Citation2014). As cities’ sustainability efforts are strongly influenced by local policies (North et al., Citation2017; Saha, Citation2009), politicians and local representatives play an active role in carrying and promoting the ideology of sustainable development (McCann, Citation2013). The importance of active, proactive political leadership that takes responsibility for the increased risks posed by climate change has been highlighted by several studies (Hanssen et al., Citation2013; Meijerink & Stiller, Citation2013; Orderud & Kelman, Citation2011). This current article aims to provide further evidence to the argument, that party politics is a key factor in shaping cities’ climate actions and in the pursuit of environmental sustainability (Bossuyt & Savini, Citation2018). The role of local politics cannot be marginal, if only because there are significant differences in the interest of some key local leadership actors in adapting to climate change (Swianiewicz et al., Citation2018) and because city officials do not have a uniform understanding of sustainability, leading to different political priorities (Zeemering, Citation2009). Political orientations are not just drivers but often also barriers to urban climate governance learning and urban sustainability plans (Prado-Lorenzo et al., Citation2010; Wolfram et al., Citation2019). The plans of society and experts can only become reality if they have the necessary political support and approval (Bulkeley & Betsill, Citation2003). A common example is that city leaders are aware of the threats posed by climate change but fail to act (Zahran et al., Citation2008). Moreover, development can sometimes conflict with the interests of central authorities and local actors (Bulkeley & Betsill, Citation2003; Hughes, Citation2019). It is a worrying trend, that European mayors typically did not prioritize the long-term perspective, which would be necessary to achieve sustainability goals, and did not consider the forecasting of future environmental impacts of projects as a high priority (Magnier et al., Citation2018). There are also political determinants of the existence of these long-term developments, with right-wing governments at the national level, for example, being more hesitant and not pursuing long-term sustainability investments (Arslan & Yildiz, Citation2022).

As Mocca (Citation2017) notes, research on cities’ participation in sustainability initiatives is mainly qualitative, with only a few studies using a quantitative approach (e.g., Broto & Bulkeley, Citation2013; Mocca, Citation2017; Portney & Berry, Citation2010). In addition, studies on urban climate governance typically focus on a small number of cities, and analyses with a large number of observations are rare (van der Heijden, Citation2019). The present study attempts an analysis based on quantitative methods to explore the political factors which may explain how cities that have already applied for the EGCA differ from other European cities that are not interested in applying. The second part of the research seeks to find out whether the fact of being a finalist in the competition can be linked to certain political characteristics. Since the evaluation of the application is based on environmental indicators and environmental developments, we can also indirectly conclude that some political factors are contributing to the success of the city. Thus, in contrast to studies on the role of formal networks, where little information is available on the role of these networks in terms of improvement in environmental indicators (e.g., Heikkinen et al., Citation2018), the EGCA evaluation allows us to make such relationship findings on political factors. Participation in horizontal networks is not primarily driven by the political will to improve the environmental performance of cities, which is reflected in the fact that these cities are not always characterized by particularly good environmental indicators (Mocca, Citation2017). The problem with these networks and participation in sustainability initiatives is that there is no distinction between “deep” and “superficial” commitment (Krause, Citation2011). In the case of EGCA, however, these two commitment types are sharply differentiated.

Political factors influencing environmental development

Green parties

García‐Sánchez and Prado-Lorenzo (Citation2008) argue that some political ideologies are more favorable to sustainability policies than others. This is most applicable to greens, since sustainability itself, the right of future generations to resources is reflected in Porrit’s (Citation1984) list of minimum criteria for being green. With the growing popularity of sustainability, the environment has become an issue along which urban electoral fault lines have been redefined, as indicated by the rise of green parties at the local level (Bossuyt & Savini, Citation2018). For greens, the most important political issue is the relationship between humans and the environment, which fundamentally sets them apart from other political ideologies (Leach, Citation1996). According to Goodin (Citation1992), the inherent moral value of nature is at the heart of green political theory. Green ideology is a fresh articulation of preexisting political elements (Stavrakakis, Citation1997), but also a distinct ideology, which is confirmed by Price-Thomas (Citation2016). For green parties, the environmental issue is the primary concern, and the topics of sustainability and ecology are also relevant for newer green parties, mainly formed in Central and Eastern Europe (van Haute, Citation2016). In addition to environmental questions, green parties are also concerned with subjects such as women’s equality, participatory democracy, sexual minorities and refugee rights (Talshir, Citation2002). Despite their commonalities, the green parties were not homogeneous from the beginning (Burchell, Citation2002; Müller-Rommel & Poguntke, Citation1989) and are not homogeneous in terms of ideology even today (Price-Thomas, Citation2016). However, their coherent set of ideological orientations allows them to be clearly distinguished from the rest of the parliamentary spectrum (Price-Thomas, Citation2016). In addition, the greens form the most homogeneous cluster of the European party families and, most importantly from the point of view of the current analysis, they take a very unified position on the critical role of environmental protection, the issue that they primarily own (Ennser, Citation2012). Their prioritization of environmental values makes them homogeneous, even despite the differences in their positioning on the left-right scale (Carter, Citation2013).

Neumayer’s (Citation2003) research has shown at the national level that a higher share of green parties (complemented by left-wing, liberal parties) in the legislature is associated with lower levels of pollution. The influence of green parties was also confirmed by Mourao’s (Citation2019) study, which found a relationship between the share of the green party family in parliaments and the air pollution reduction outcomes in each country. Some case studies report on the positive role of green parties at the local level. Manca’s (Citation2020) thesis on some of the cities that applied for and succeeded in the EGCA bid found that green parties were represented in some of the local governments of the cities in the study and that party representatives were committed to the Green Capital initiative. The positive local impact of green parties was confirmed by several case studies of winning cities. In Hamburg, for example, green parties were the main supporters of low-carbon housing programmes (Scheller & Thörn, Citation2018). And the city of Oslo was stably governed by a coalition that supported sustainability policies, and this was further strengthened in 2015 when a new red-green coalition came to power (Hofstad & Vedeld, Citation2021). The impact of the green parties may be felt in the long term. In Stockholm, although the green party Miljöpartiet de Gröna was not in government during the EGCA application phase in 2008, they were in coalition in the previous term. Per Bolund, the party’s Member of Parliament has noted that the city’s EGCA success was more due to the policies of the previous term, with the new right-wing government taking the credit (Lönegren, Citation2009).

However, the presence of a green party could even be detrimental to sustainability initiatives. This is due to political struggle and the efforts of other parties to maintain power. In Liverpool, for example, after the Green Party came into opposition in the local council, Labor representatives who had previously supported the EGCA initiative took no longer part in the project (North et al., Citation2017). As can be seen from this example, cooperation between greens and their left-wing counterparts does not always materialize. According to Huan (Citation1999), the relationship between them is “friendly but not close,” and in most cases, only a low level of cooperation is shown (as cited in Mourao, Citation2019).

H1-a: The higher the proportion of green party representatives on city councils, the better the chances that the city will apply for the EGCA.

H1-b: The higher the proportion of green party representatives on city councils, the better the chances that the city will make it to the EGCA final.

Parties’ attitudes toward sustainability

Political parties seek to maximize votes and act according to a power-gaining logic, and thus cannot ignore local green movements. Green parties also influence the policies of other parties by their mere presence and by bringing environmental issues to the fore. Although most parties have accommodated environmental issues to some extent, they have struggled to integrate the issue and there is still a large gap between the greens and other parties on environmental policy (Carter, Citation2013). A further drawback of the integration of green issues by other parties is that once the green party has been established, this act is counterproductive and only increases the green party’s electoral performance (Grant & Tilley, Citation2019). Although sustainable development can be considered a nonpartisan and nonpolitical concept, it seems to appeal to more progressive parties and is more compatible with the ideology of center-left parties (Mocca, Citation2017). Research by Wen et al. (Citation2016) found that left-wing governments tend to prioritize environmental quality over economic performance, while the reverse is true for right-wing governments. A potential reason is that governments with a left-leaning orientation are more sensitive to consumer and environmental movement requests for environmental protection (King & Borchardt, Citation1994). However, right-wing, conservative parties are not completely opposed to sustainability developments, and even among the far-right parties, some are supportive of certain renewable energies (Hess & Renner, Citation2019). The existence of right-wing city governments has a negative impact on the implementation of Local Agenda 21 (García‐Sánchez & Prado-Lorenzo, Citation2008). In Poland, mayors belonging to the right-wing Law and Justice party showed no significant interest in mitigating climate change at the local level, while in Norway there was no difference in sustainability efforts by party affiliation (Swianiewicz et al., Citation2018). Manca’s (Citation2020) research supports this statement by showing that in Oslo, the EGCA bid and sustainability were important issues for both the government and the opposition. However, Prado-Lorenzo et al. (Citation2010) conclude, based on a literature review, that there is insufficient evidence to identify which political orientations are more inclined to support sustainability efforts at the local level (and their research even suggests that the left-wing government has had a negative impact). This may be explained by the convergence of party positions on major policy issues such as sustainable development due to the strategic politicization of the issue (Lindblom, Citation1977 as cited in Bossuyt & Savini, Citation2018). The analysis of the political orientation of the local government is also of particular importance because, in the majority of cases, the local leaderships of the cities that have applied for the EGCA have not involved the opposition in the EGCA bidding process (Manca, Citation2020).

H2-a: Cities with left-wing city governments are more likely to apply for the EGCA.

H2-b: Cities with left-wing city governments are more successful in the EGCA bidding process.

H3-a: Cities whose councils prioritize the protection of natural resources over economic growth are more likely to apply for the EGCA. This hypothesis takes into account all parties in local councils, not just the greens.

H3-b: Cities whose councils prioritize the protection of natural resources over economic growth are more successful in the bidding process. This hypothesis takes into account all parties in local councils, not just the greens.

Euroscepticism

As the EGCA is an EU initiative, participation in the competition is also influenced by the attitude of each party toward European integration. This determines the level of commitment of a city and its involvement in pan-European activities (Mocca, Citation2017). Center-left and left-wing parties are more inclined to participate due to their ideology (Mocca, Citation2017), while analysts also consider far-left parties to be Euroskeptic alongside far-right parties (Hooghe et al., Citation2002). As regards the attitude of the green parties toward European integration, the literature shows conflicting views. Marks et al. (Citation2002) consider green parties as moderately opposed to European integration however, Helbling et al. (Citation2010) claim the opposite and portray these parties as pro-integration. Mocca’s (Citation2017) study on socio-ecological urban networks among European cities concluded that the existence of membership in these networks is not influenced by the political orientation of the city administration. However, if the leadership is center-left, the city will participate in more horizontal organizations. Pablo‐Romero et al. (Citation2015) studied the Covenant of Mayors and found that the existence of a liberal local government is a factor that increases the odds of membership.

In most European countries, local politics is influenced by party affiliation (Kjaer & Elklit, Citation2010), but sometimes the loyalties of representatives to the local community and the national party are in conflict and ideological issues are less important in local politics (Egner et al., Citation2018). Thus, ideology-free decisions are often made to ensure the common good (Kukovic et al., Citation2015; as cited in Egner et al., Citation2018).

H4: Cities with a higher proportion of Euroskeptic representatives on their councils are less likely to apply for the EGCA.

The mayor as the champion of sustainability

The varying powers of mayors across countries are controlled for in the analysis. The reason is, that the role of the mayorFootnote2 is also an essential factor. Especially in countries where the mayor legally and legitimately controls all executive functions (Mouritzen & Svara, Citation2002). Manca’s (Citation2020) study gives examples of cases where the mayor has pushed for an EGCA application even when the structural conditions and the motivation of the city councilFootnote3 were not appropriate, or when the city’s application had already been unsuccessful several times. The vision and actions of a mayor committed to sustainability can guide future mayors and set the city’s sustainability ambitions for the long term, as in the case of Vitoria-Gasteiz (Neidig et al., Citation2022). The mayor’s firm commitment also supported Bristol’s and Ljubljana’s successful applications (Hambleton & Sweeting, Citation2016; Svirčić Gotovac & Kerbler, Citation2019). The importance of the mayor’s strong role is illustrated by the fact that the EGCA itself was the brainchild of the then mayor of Tallinn, Jüri Ratas. However, a mayoral decision can block a grassroots initiative (North et al., Citation2017), and an EGCA bid can fail after a change of mayor (Manca, Citation2020). A mayor can also slow down a city’s green ambitions even if he or she comes from a party that is committed to sustainability (Neidig et al., Citation2022). Mayors are not necessarily tied to party politics. The proportion of independent mayors varies significantly across countries, with nonpartisan governance being more common in Europe in cities with over 200,000 inhabitants (Egner et al., Citation2018). In some cities, city leaders other than the mayor, or experts are also becoming champions of sustainability and are seriously promoting the EGCA application. A good example is in Vitoria-Gasteiz (Neidig et al., Citation2022), where the initiative was spearheaded by Luis Andres Orive, Director of the Environmental Studies Center, and in Ljubljana (Svirčić Gotovac & Kerbler, Citation2019), where it was strongly supported by the chief architect Janez Koželj.

H5-a: Cities with a strong mayor format are more likely to apply for the EGCA.

H5-b: Cities with a strong mayor format are more successful in the bidding process.

Political fragmentation

A study of Spanish cities by Prado-Lorenzo et al. (Citation2010) found that the diversity of parties in local councils, the large number of interest groups and political competition all contribute to the city’s sustainability ambitions. However, fragmentation can also weaken governance. Alesina and Drazen (Citation1991) theorize that a fragmented party system is an obstacle to the introduction of reforms. When governments do not have an absolute majority, they cannot impose their will and policies (Prado-Lorenzo et al., Citation2010). The lack of coordination between policy frameworks that promote green economy measures poses a significant barrier to becoming a green city (Rode, Citation2013). Ward’s (Citation2008) research shows the non-significant role of fragmentation, as the author found no link between the fragmentation of a country’s legislature and the country’s actions to promote sustainability and green ambitions.

H6-a: Cities with a more fragmented council are less likely to apply for the EGCA.

H6-b: Cities with a more fragmented council are less successful in the bidding process.

Stability and possible central government support

Political stabilityFootnote4 is another factor that could theoretically facilitate the implementation of these policies. According to the cities that applied for the EGCA, sustainable development measures take time to implement and can only be felt in the medium to long term (Manca, Citation2020). The positive effect of stability on sustainability is also highlighted by García-Sánchez and Prado-Lorenzo (Citation2009), but another research by this pair of authors shows that political stability has no effect on the implementation of the Local Agenda 21 objectives (García‐Sánchez & Prado-Lorenzo, Citation2008), and a study by Prado-Lorenzo et al. (Citation2010) also found no relationship between stability and sustainability scores in Spanish cities.

H7-a: Cities that are politically stable are more likely to apply for the EGCA.

H7-b: Cities that are politically stable are more successful in the bidding process.

In addition to time, cities need adequate support to be successful (Manca, Citation2020). This could be financial or technical support. According to Bulkeley and Betsill (Citation2013), while local capacity and local politics play an important role in narrowing the gap between local urban development realities and sustainability aspirations, the most significant dynamics go beyond this level. Local authorities often lack the financial resources and technical capacity to implement sustainability efforts (Betsill & Bulkeley, Citation2007). Financial dependence is a particular problem in centralized states, where cities’ sustainability policies depend on central government support (Ehnert et al., Citation2018). There is a significant intergovernmental dependency in the domain of sustainability, i.e., local governments rely on the government for this policy (Denters et al., Citation2018). For example, the successful implementation of Agenda 21 depends on the provided by national administrations (García‐Sánchez & Prado-Lorenzo, Citation2008). As some examples illustrate (e.g., Yazar & York, Citation2021), sustainability action relies on the power relations between the parties that control the local and national government. If there is ideological conflict, the city can be left to its own devices. This could be one reason, why European mayors are frequently concerned about a general lack of technical support from higher levels (Magnier et al., Citation2018). In the analysis, the alignment of the political orientation of local and central government will be used as a dummy variable.

Other territorial levels, not just the central government, can play an important role through multi-level governance. In the Netherlands, for example, provincial governments, in addition to the national government, have contributed to funding climate action at the local level (Hoppe et al., Citation2016). But still, higher levels of authority are not always required for successful local action (Bulkeley & Betsill, Citation2013). Intergovernmental dependency can be “remedied,” for example, by transnational networks, which allows cities greater autonomy (Mocca, Citation2017). Examples of such international organizations include ICLEI or the Covenant of Mayors, which are popular among EGCA winner and applicant cities (Neidig et al., Citation2022; Pantić & Milijić, Citation2021).

H8-a: Cities, where there is ideological alignment between the local and the national leadership, are more likely to apply for the EGCA.

H8-b: Cities, where there is ideological alignment between the local and the national leadership, are more successful in the bidding process.

Methodology

The analysis includes 110 cities that have applied for the EGCA up to the 2024 round. As these cities may have applied more than once and may have been characterized by completely different political variables at the time of application, the authors have treated each application separately. Thus, a total of 184 applications’ political backgrounds are included in the study. Apart from the first two calls (the 2010 and 2011 rounds and the 2012 and 2013 rounds were published together, in pairs), the deadline for applications was three years before the year of the round in which the application was submitted, in October (e.g., October 2013 for the 2016 round). The call for applications is usually published around May. The research raised the issue of what happens when there is a change of government and/or a new council is formed between the call and the deadline. On the one hand, since successful EGCA proposals are quite thorough and voluminous (for example, the document of the 2013 winner Nantes is 208 pages long), it is not realistic to prepare them in a few weeks. On the other hand, a new mayor or council can stop a proposal that is already in the process of being written. With these two constraints in mind,Footnote5 the authors examined the political variables observed halfway between the call for proposals and the deadline for submissions (mid-August, in May–October terms).

To test the hypotheses, 184 control cities were needed (Appendix A). These cities were selected from the Eurostat Urban Audit database. Prior to random selection, cities with a population of more than 100,000 were selected according to the EGCA criteria.Footnote6 Furthermore, as the database is predominantly composed of British, German, Spanish, Italian and French cities, these would have dominated the sample and thus skewed the analysis. To compensate for this, a maximum of three more cities from these countries could be included in the control sample compared to the total number of cities that actually applied for the EGCA from the given countries. In addition, countries that were included in the Urban Audit and had already launched a candidate city in reality, had to provide at least one control city. Thanks to random selection, the control sample included one city from Luxembourg, one from Cyprus and three from Switzerland, although zero cities from these countries had even applied, although the EGCA Rules for Participation allows the mentioned countries to take part in the competition. Control cities from Albania, Serbia, Iceland and Northern Macedonia were not selected as they were not included in the Urban Audit databaseFootnote7 (Appendix B). There was also a restriction that a city could only be included once in the control sample, and that a city that had actually been entered could be also selected as a control. The cities were then distributed between the 2010 and 2024 rounds according to the number of real applicant cities per round. If a real applicant was selected as control, the city had to be assigned to a year so that it was in a different election cycle compared to the city’s real application(s). The dependent variables in the analysis were the fact of bidding (0 = no, 1 = yes) and the outcome of the bid (0 = non-finalist, 1 = shortlisted finalist). Logistic regression analysis was used due to the binary nature of the two dependent variables.

Independent variables

For cities, the composition of local councils by party was examined. When some parties were running in a coalition, the exact party affiliation of the delegates (if not included in the national data) was obtained from the local government website. Where no such precise breakdown was available, the national importance of the parties in the given coalition was examined and weighted accordingly.Footnote8 Each party’s attitude toward sustainabilityFootnote9 was determined using a weighting factor from the 1999–2019 Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Jolly et al., Citation2022) and the 2019 CHES Candidate Survey (Bakker et al., Citation2020). The position toward environmental sustainability could obtain a value between 0 (Strongly supports environmental protection even at the cost of economic growth) and 10 (Strongly supports economic growth even at the cost of environmental protection). The survey covered several years (2010, 2014 and 2019), so that it could be fitted into the timeframe of the research from 2008 (rounds 2010 and 2011) to 2020 (round 2024).Footnote10 A problem occurred when some municipalities had a high proportion of independent or local party representatives. It would have potentially distorted the analysis, so a 75% threshold was set. The environmental index was calculated only if the share of the Chapel Hill Survey parties’ representatives in the council was above this value. The environmental index can be calculated using the following formula:

The percentage of green party representatives in local councils was also included as an independent variable. Green parties were defined based on the book Green Parties in Europe by van Haute (Citation2016) and on the relationship with the European Greens (full members, associate members, candidate members).Footnote11 This variable treats green parties as uniform, based on the homogeneous high prioritization of environmental values (Carter, Citation2013; Ennser, Citation2012). Any minimal differences in their environmental policies are represented by the previous variable, the environmental index. To confirm the H4 hypothesis, the proportion of representatives belonging to Euroskeptic parties was also determined. The parties that can be classified as such were defined on the basis of the PopuList (Rooduijn et al., Citation2019).

The fragmentation of the local council was identified by the effective number of parties. This measure of fragmentation was developed by Laakso and Taagepera (Citation1979) and can be described by the following formula:

Before examining the variables on stability and the orientation of the city leadership, it should be borne in mind that different types of local governance have developed in different countries. Mouritzen and Svara (Citation2002) distinguish four ideal forms: strong-mayor form, committee-leader form, collective form and council-manager form. Heinelt et al. (Citation2018) have classified most of the countries in Europe according to these categories. In this paper, the authors use this classification. The importance of mayors in the EGCA application (Manca, Citation2020) is also highlighted as an independent variable, the mayor’s power. Similar to Mocca’s (Citation2017) study, cities with a strong-mayor model are assigned a 1, while the rest are assigned a 0. The forms of urban governance were also used to determine how the authors define the political orientation and stability of urban governance. Complementing Mocca’s (Citation2017) political leaning table,Footnote12 in some countries the party affiliation of the mayor was the deciding factor, while in other countries the party with the highest percentage of seats on the council was the determinant. Political orientation is marked as 1 for left and center-left leadership and 0 for all other leaderships (including independent mayors). The stability variable was considered by the authors of this study to be achieved if the strong mayor systems had the same mayor at the time of the study and in the previous term, or if he/she was from the same party (coalition); while in the other cases, the same party was in government in the previous term.Footnote13 Possible national government support is also included as an independent variable. This is considered to be the case if, at the time of the analysis, the political orientation of the city government and the political orientation of the national government are aligned.Footnote14

As the success of a competition may be determined by the experience gained via previous applications (refinements due to detailed jury evaluation, incremental improvements over several applications) and by learning best practices via long-time participation, the analysis also took into account the number of times a city applied for the award.

Since the strength of green parties varies significantly across European countries (van Haute, Citation2016), and some other independent variables also show variations by country, the country variable was included as a fixed effect in the models with the existence of the application as the outcome. Another reason for using the fixed effect is that it allows us to compare municipalities that would have similar potential benefits due to multi-level governance (at least national and sometimes regional) for the development of environmental policies. For models investigating the success of the application, the round of the application was selected as a fixed effect. A potential reason for this was that the upward trend in the strength of European green parties—as indicated by the green’s success in Belgium and Germany in 2018 and the European Parliament elections in 2019 (Pearson & Rüdig, Citation2020)—may bias the analysis.Footnote15 Fixed effect regression models were constructed using the bifeFootnote16 package in R.

Results

The descriptive statistics of the variables included in the analysis are illustrated in . The results of the fixed effect logistic regression models, with the existence of the applications as the dependent variable, are shown in . The accuracy of the final model is 61.88%. The only independent variable that retained a significant effect in all models is the left-wing led local government. This suggests that cities with left-wing leadership are more likely to apply for the EGCA. The models estimate that the effect of this variable is significant, with Model 6 suggesting that the presence of a left-wing government is associated with a 25% increase in the probability of applying (based on the average partial effects). Contrary to the hypotheses formulated, there is no significant effect of the proportion of representatives belonging to euroskeptic parties, nor of the value of the environmental index of the local council. For stability and political fragmentation we found weak evidence (positive effect for stability, and negative effect for fragmentation), which disappeared after Model 4. According to the last model, the proportion of green party representatives in the local council is related to an increased chance of applying for the award. However, this result should be treated with caution, as due to a lack of data, only less than 60% of the initial cities were included in the last model. In addition to the countries with a few candidate cities (e.g., Serbia, Albania, Iceland), models 5 and 6 do not include cities from Finland and Estonia, which have already provided two EGCA winners. If this limitation is taken into account, it can be stated that a one percent growth in the share of green party representatives is associated with the growing probability of applying with a small amount of 0.9% and 1.5% respectively (based on average partial effects derived from Model 5 and Model 6).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for the variables in the analysis.

Table 2. Results of the fixed effect binary logistic regression models treating the existence of an application as a dependent variable.

The results show that the variables under consideration are much more suitable for modeling the non-finalist/finalist difference than previously for the non-applicant/applicant relationship (). The accuracy of the final model is 82.9%, with 92.5% of non-finalists correctly categorized. The role of three variables can be clearly highlighted: a greener, more nature-friendly city council and previous experience are associated with increased chances of a successful application, while political stability is connected with a decreased probability. The importance of experience in the application process is indicated by the fact that even one previous application shows a 17% increment in the probability of being a finalist. Several of the analyzed cities (Ljubljana, Lisbon, Tallinn) failed to make it to the final with their first application, but have steadily improved since then, becoming finalists and then winners. However, there are also cities in the sample which, despite having applied several times, have never made it to the final (e.g., Pécs, Budapest). The results show that cities with a higher proportion of green representatives and a lower environmental index, i.e., a greater focus on natural values and nature conservation, are more likely to be finalists. A 1% increase in the proportion of green party representatives is associated with a 0.9% increased chance of being a finalist, while the increase of the environmental index by one is related to a 21.2% reduced probability of being a finalist, according to the results of Model 6. Again, as a limitation, it should be noted that the number of cases in the last model is notably reduced after including the environmental index (61.9% of all observations are included in this model).

Table 3. Results of the fixed effect binary logistic regression models with the fact of being a finalist as a dependent variable.

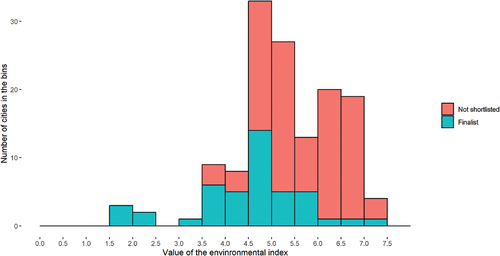

The role of the environmental index is underlined by the fact that only one of the 10 candidates with the lowest index values, Montpellier (2010 round), did not make it to the final. Furthermore, it is important to note that four winning cities are also on this list. confirms this statement and also shows that there are only a few finalist cities above the index value of 6. The finalist with the least favorable environmental index is Tallinn’s application for the round 2022 (7.21).

Figure 1. The relationship between the value of the environmental index and the fact of being a finalist. Histogram with 0.5 bandwidth specification.

The role of stability is opposite to what was expected, as the model predicts that if a city is under stable management, then all other variables held constant, it is 15.58% more likely to be among the non-finalists. Based on the raw data, this strange difference is also noticeable among the winners, as there are fewer stable cities than those with new city leadership (the difference is not statistically significant, however). The political ideology of the city government and the allegedly supporting role of the central government showed significant effect until the inclusion of the sustainability index variable and the large reduction in sample size. These results suggest that a left-wing ideology, in addition to the connection with a boost in the likelihood of the application’s existence, also shows an association with the probability of its success. The strength of local government is illustrated by the fact that cities can be successful even if the party governing the city is not a part of the country’s government. The fragmentation of the council, the existence of a strong mayor and the proportion of Euroskeptic representatives have no significant effect.

Discussion and conclusion

In the study, hypotheses were identified and tested in relation to the political factors associated with the application to the EGCA and the outcome of this bid. In doing so, the present analysis fits into a series of previous studies (e.g., García‐Sánchez & Prado-Lorenzo, Citation2008; Mocca, Citation2017) that have investigated the participation of European cities in sustainability efforts comprehensively. The innovation of the current study, besides the thorough analysis of the sustainability endeavor under study, the EGCA, is that it examines not only the factors influencing participation but also the political variables that can be associated with the success of the bid and thus sustainability improvements. Thereby distinguishing between sufficient or deep participation in sustainability initiatives. The models developed in this study suggest that both the existence of the applications and the outcome of the bids are influenced by the political background of the cities. Although the fit of the models constructed to explain the difference between the applicant cities and the control sample is not outstanding, they show significant improvement over the null model. The models that predicted the success of the applications, on the other hand, performed particularly well and showed a convincing fit.

The main finding of the research is the positive impact of the local green parties on sustainable development efforts. This supports the claim of Bossuyt and Savini (Citation2018) that party politics is also a key factor for environmental sustainability at the local level. Cities with a high proportion of green party representatives in the local councils are more willing to participate in this European sustainability initiative (given the limitation, that this model was run on a reduced sample size) and to undertake a thorough assessment and evaluation of their sustainability indicators. The role of the green parties and, in line with this, the attitude of the entire municipal council toward the environment, will provide a solid basis and a good estimate of the success of the application. Although sustainability is an ideal that has great appeal across the political spectrum (Bossuyt & Savini, Citation2018), the party composition of local councils has a significant impact on the prioritization of sustainability efforts. EGCA finalists are typically cities whose councils are sensitive to environmental concerns. In contrast, the councils of the cities that have only applied for the competition, but did not become finalists, do not include green parties, and local politicians tend to prioritize economic interests on the basis of their party affiliation. Given that the results suggest that green parties are key to a successful bid, the reason for the typically unsuccessful bids in eastern and southeastern European cities may be due to the limited green movements and green parties in these countries (van Haute, Citation2016), both at the local and national level. The results also suggest that, in the case of the EGCA finalist cities, the policies of local green representatives have been successful in terms of environmental ambitions. In addition to the studies of Neumayer (Citation2003) and Mourao (Citation2019), which indicated the successful policy implementation of green parties in the national parliament, this study has also demonstrated the positive actions of their policies at the local level to promote sustainability. As the EGCA can also be seen as a kind of green city ranking (Meijering et al., Citation2014), it can be assumed that the role of political factors is crucial in achieving a better placement in the green city rankings, in contrast to for example, smart city rankings (Gil et al., Citation2020), and it is important in the development of green city branding. Thus, the degree of activity of green parties at the local level cannot be separated from the metrics of sustainability ambition. In general, it is easier for green parties to break through at the sub-national level than at the national stage (Harrison, Citation1995). Thus, the positive role of their policies may first be seen in the urban area, which has been identified as a priority level for sustainability. The results show that their environmental policy is successful. Furthermore, participation in government at the local level provides these parties with valuable experience that they can use in the national government (Poguntke, Citation2002). For this reason, these parties are of particular importance at the local level. In terms of the policy proposals formulated, this paper emphasizes the claims of Mourao (Citation2019). It is important to involve actors in governance that are responsible for sometimes neglected issues. This is also necessary because the participation of green parties in councils allows them to implement some of their policies, which are generally effective from an environmental point of view (Mourao, Citation2019). Furthermore, the role of green parties was confirmed using quantitative methods on a larger sample, aligning with previous case studies at the city and national levels (Berg, Citation2011; Hofstad & Vedeld, Citation2021; Manca, Citation2020). The greater extent of efforts by cities led by parties that prioritize environmental protection is similar to the results of research in the U.S. that highlighted the positive role of Democratic Party city leadership (Krause, Citation2011).

The role of the local leadership’s political orientation in pan-European sustainability initiatives and cooperation is supported by the literature and the present study. Left-lead cities are more inclined to take part in the contest, which supports the idea that these parties are more active in European programmes (Mocca, Citation2017). Furthermore, the existence of left-wing leadership seems to provide a small, albeit not significant advantage in the competition as left-led cities do perform better, i.e., they do have better sustainability indicators.

The current research does not confirm the benefits of political stability. Instead, it highlights the highly influential positive role of EGCA experience and repeated bidding. This effect is evident even when political stability is not present. Multiple applications also provide an opportunity for cities to benefit from EGCA as a form of horizontal multi-level governance. This concerns both joint workshops and conferences and the adaptation of best practices from previous Green Capitals. Moreover, the models highlight the importance of innovation and the novelty that new political leadership brings to the finalists. This result is in contrast to Manca’s (Citation2020) claim, which is based on expert interviews, that successful EGCA bidding can only be achieved with medium- or long-term commitment. However, it is also possible that these new political leaderships are merely reaping the laurels of the previous era(s) of sustainability policy (Lönegren, Citation2009; Neidig et al., Citation2022), and that there were indeed long-lasting improvements in sustainability under the previous leadership. This is a positive result, as it shows that once a city is on the road to becoming a green city, even a change of political power cannot stop it. The potential reasons for this, apart from the long-term commitments inherent in membership in sustainability initiatives (Pablo‐Romero et al., Citation2015), are the possibility of inter-party cooperation that has been developed in the earlier stages of the bid, in addition to the already established public and media support. Contrary to hypotheses, the significant role of fragmentation, the proportion of euroskeptic representatives, the power of the mayor and the alignment of the local and national government (negative effect in some models with the success of the application as the dependent variable) was not found in any of the final models. The latter is particularly interesting from the perspective of multi-level governance. The results show that ideological similarity with the national level government does not provide competitive advantage, in the same way, that in the U.S. the political ideology of the state level does not influence the climate action of individual cities (Krause, Citation2011).

A mixed-method approach and analysis of local-level city plans and documents, party manifestos and city council records would be recommended to support the findings of the study. Such studies have already been carried out in some EGCA cities, but they cannot be generalized to the full range of European applicants. As the analysis of urban plans is particularly useful to explore the interdependence arising from the concept of multi-level governance (Zeemering, Citation2012), such an analysis could also shed light on how cities use EGCA as a form of horizontal multi-level governance. As a limitation of the study, it should be noted that some of the political factors included in the analysis (green party strength, councils’ environmental index) may be spatially auto-correlated, and therefore, the results may be biased. For further research, it is recommended to consider geographical proximity and the resulting spill-over effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank anonymous reviewers for their constructive suggestions and comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dávid Sümeghy

Dávid Sümeghy is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Pécs, Department of Political Geography, Development and Regional Studies. His research focuses on the study of voter behavior, social cohesion and the urban application of spatial econometric analysis. His work has also been published in East European Politics, Quality & Quantity, and Regional Statistics.

Dalma Schmeller

Dalma Schmeller is a geographer, urban system engineer and geoinformatics assistant, PhD student at the University of Pécs Doctoral School of Earth Sciences. Her research interests include the European Green Capital Award, urban modeling, sustainable and green urban planning.

Notes

1. In countries where there is no city with more than 100,000 inhabitants, the largest city is eligible to apply (European Commission, Citation2021).

2. In this study, the term mayor is used to refer to the political leader of a municipality, irrespective of the local names that vary from country to country.

3. In this study, a council is defined as the elected collective decision-making body of a municipality/city/town, irrespective of its local names, which vary from country to country.

4. Political stability typically means that the current leadership (mayor or party) has governed the city in the previous term too.

5. It is also possible that some cities will submit applications well in advance of the deadline.

6. This limitation does not take into account that in some countries where there is no city with a population of more than 100,000 people, the most populous city can apply for the award.

7. This was partly the reason that the sample did not match the actual number of applications per country, and also that only two Slovenian and one Estonian control city could have been selected compared to the real 5–5 applications.

8. If no party did better than 15% nationally, seats were allocated by the number of parties in the coalition. If there was only one party that performed above 15%, 80% of the seats went to that party and the rest was divided among the remaining members (the most typical case). If more parties scored above 15%, 80% of seats were divided equally between them. When non-whole seats were calculated, the value of the party that performed better nationally was rounded up.

9. Here again, the authors highlight Egner et al.’s (Citation2018) finding that local politicians do not always follow the ideological guidelines of their national party, so the application of this weighting factor at the local level can be biased.

10. The 2010 weighting factor has been applied to the values before 2010. And for subsequent years, the value of the survey prior to the election year. If there was a data gap, the weighting factor closest in time was assigned. And if the 2014 value was missing, the 2010 and 2019 values were averaged.

12. Countries not included in Mocca’s (Citation2017) analysis defined by mayor’s party are Cyprus, Croatia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Türkiye; and by the largest party are Czechia, Estonia, North Macedonia, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Norway, Serbia, Switzerland. To determine these, the mayor’s strength calculation of Heinelt et al. (Citation2018) was used, or if this was not available, the value of neighboring countries was examined.

13. In the event of a succession or withdrawal from the old party, stability is maintained.

14. The ideological similarity is not a sufficient criterion, the mayor’s party/party in the majority in the city government must be part of the country’s government.

15. Since the main research question for the existence of the application was why exactly those cities that applied are interested in the EGCA, we decided to use the country variable as a fixed effect. In the case of the success of the application, it is necessary to consider all applicants in a given year jointly and to compare them. Here, country differences are factors that are also reflected in some EGCA indicators (transport culture, geography influencing energy usage, air pollution), which can be an advantage or a disadvantage in the evaluation of the bid.

16. Czarnowske, D., Heiss, F., & Stammann, A. bife-Binary Choice Models with Fixed Effects.

References

- Acuto, M. (2016). Give cities a seat at the top table. Nature, 537(7622), 611–613. https://doi.org/10.1038/537611a

- Alesina, A., & Drazen, A. (1991). Why are stabilizations delayed? American Economic Review, 81(5), 1170–1188.

- Arslan, Ã., & Yildiz, T. (2022). Political orientations of governments and renewable energy. International Business Research, 15(11), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v15n11p17

- Bakker, R., Hooghe, L., Jolly, S., Marks, G., Polk, J., Rovny, J., Steenbergen, M., & Vachudova, M. A. (2020). 2019 chapel hill candidate survey (Version 2019.1). University of North Carolina. chesdata.eu.

- Berg, M. M. (2011). Climate change adaptation in dutch municipalities: Risk perception and institutional capacity. In K. Otto-Zimmerman (Ed.), Resilient cities (pp. 265–272). Springer.

- Betsill, M., & Bulkeley, H. (2007). Looking back and thinking ahead: A decade of cities and climate change research. Local Environment, 12(5), 447–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830701659683

- Biresselioglu, M. E., & Karaibrahimoglu, Y. Z. (2012). The government orientation and use of renewable energy: Case of Europe. Renewable Energy, 47, 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2012.04.006

- Bossuyt, D. M., & Savini, F. (2018). Urban sustainability and political parties: Eco-development in Stockholm and Amsterdam. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 36(6), 1006–1026.

- Broto, V. C., & Bulkeley, H. (2013). A survey of urban climate change experiments in 100 cities. Global Environmental Change, 23(1), 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.07.005

- Bulkeley, H., & Betsill, M. M. (2003). Cities and climate change: Urban sustainability and global environmental governance. Routledge.

- Bulkeley, H., & Betsill, M. M. (2013). Revisiting the urban politics of climate change. Environmental Politics, 22(1), 136–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2013.755797

- Bulkeley, H., Jordan, A., Perkins, R., & Selin, H. (2013). Governing sustainability: Rio+20 and the road beyond. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 31(6), 958–970. https://doi.org/10.1068/c3106ed

- Burchell, J. (2002). The evolution of green politics: Development and change within European green parties. Earthscan.

- Carter, N. (2013). Greening the mainstream: Party politics and the environment. Environmental Politics, 22(1), 73–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2013.755391

- Da Cruz, N. F., Rode, P., & McQuarrie, M. (2019). New urban governance: A review of current themes and future priorities. Journal of Urban Affairs, 41(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2018.1499416

- Dent, C. M., Bale, C., Wadud, Z., & Voss, H. (2016). Cities, energy and climate change mitigation: An introduction. Cities, 54, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.11.009

- Denters, B., Steyvers, K., Klok, P. J., & Cermak, D. (2018). Political leadership in issue networks: How mayors rule their world? In H. Heinelt, A. Magnier, M. Cabria, & H. Reynaert (Eds.), Political leaders and changing local democracy (pp. 273–296). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Egner, B., Gendźwiłł, A., Swianiewicz, P., & Pleschberger, W. (2018). Mayors and political parties. In H. Heinelt, A. Magnier, M. Cabria, & H. Reynaert (Eds.), Political leaders and changing local democracy (pp. 327–358). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ehnert, F., Kern, F., Borgström, S., Gorissen, L., Maschmeyer, S., & Egermann, M. (2018). Urban sustainability transitions in a context of multi-level governance: A comparison of four European states. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 26, 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2017.05.002

- Ennser, L. (2012). The homogeneity of West European party families: The radical right in comparative perspective. Party Politics, 18(2), 151–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068810382936

- European Commission. (2021). European Green Capital Award - Applying for EU Green Capital. Retrieved July 3, 2022, from https://ec.europa.eu/environment/european-green-capital-award/applying-eu-green-capital_en#ecl-inpage-1647

- García‐Sánchez, I. M., & Prado-Lorenzo, J. M. (2008). Determinant factors in the degree of implementation of local agenda 21 in the European Union. Sustainable Development, 16(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.334

- García-Sánchez, I. M., & Prado-Lorenzo, J. M. (2009). Decisive factors in the creation and execution of municipal action plans in the field of sustainable development in the European Union. Journal of Cleaner Production, 17(11), 1039–1051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.01.008

- Gil, M. N., Carvalho, L., & Paiva, I. (2020). Determining factors in becoming a sustainable smart city: An empirical study in Europe. Determining Factors in Becoming a Sustainable Smart City: An Empirical Study in Europe, (1), 24–39. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2020/13-1/2

- Goodin, R. E. (1992). Green political theory. John Wiley & Sons.

- Grant, Z. P., & Tilley, J. (2019). Fertile soil: Explaining variation in the success of Green parties. West European Politics, 42(3), 495–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2018.1521673

- Gudmundsson, H. (2015). The European Green Capital Award. Its role, evaluation criteria and policy implications. Toshi Keikaku, 64(2), 2–7.

- Hambleton, R., & Sweeting, D. (2016). Developing a leadership advantage? An assessment of the impact of mayoral governance in Bristol. Regions, 302(1), 17–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13673882.2016.11742702

- Hanssen, G. S., Mydske, P. K., & Dahle, E. (2013). Multi-level coordination of climate change adaptation: By national hierarchical steering or by regional network governance? Local Environment, 18(8), 869–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2012.738657

- Harrison, L. (1995). Green parties in Europe–evidence from sub-national elections. Environmental Politics, 4(2), 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644019508414201

- Heikkinen, M. (2022). The role of network participation in climate change mitigation: A city-level analysis. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 14(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2022.2036163

- Heikkinen, M., Ylä-Anttila, T., & Juhola, S. (2018). Incremental, reformistic or transformational: What kind of change do C40 cities advocate to deal with climate change? Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(1), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2018.1473151

- Heinelt, H., Hlepas, N., Kuhlmann, S., & Swianiewicz, P. (2018). Local government systems: Grasping the institutional environment of mayors. In H. Heinelt, A. Magnier, M. Cabria, & H. Reynaert (Eds.), Political leaders and changing local democracy (pp. 19–78). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Helbling, M., Hoeglinger, D., & Wüest, B. (2010). How political parties frame European integration. European Journal of Political Research, 49(4), 495–521. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01908.x

- Hess, D. J., & Renner, M. (2019). Conservative political parties and energy transitions in Europe: Opposition to climate mitigation policies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 104, 419–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.01.019

- Hofstad, H., & Vedeld, T. (2021). Exploring city climate leadership in theory and practice: Responding to the polycentric challenge. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2021.1883425

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2001). Multi-level governance and European integration. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hooghe, L., Marks, G., & Wilson, C. J. (2002). Does left/right structure party positions on European integration? Comparative Political Studies, 35(8), 965–989. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041402236310

- Hoppe, T., van der Vegt, A., & Stegmaier, P. (2016). Presenting a framework to analyze local climate policy and action in small and medium-sized cities. Sustainability, 8(9), 847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8090847

- Huan, Q. (1999, March 26–31). The relationships between green parties and environmental groups in Belgium, Germany and the U.K. In 27th ECPR Workshop on ‘Environmental Protest in Comparative Perspective.

- Hughes, S. (2019). Repowering cities: Governing climate change mitigation in New York City, Los Angeles, and Toronto. Cornell University Press.

- Jagers, S. C., & Stripple, J. (2003). Climate govenance beyond the state. Global Governance, 9(3), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-00903009

- Jolly, S., Bakker, R., Hooghe, L., Marks, G., Polk, J., Rovny, J., Steenbergen, M., & Vachudova, M. A. (2022). Chapel hill expert survey trend file, 1999–2019. Electoral Studies, 75, 102420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102420

- Kamal-Chaoui, L., & Robert, A. (Eds.). (2009). Competitive cities and climate change. OECD Regional Development Working Papers No. 2. OECD Publishing.

- Kern, K., & Bulkeley, H. (2009). Cities, Europeanization and multi‐level governance: Governing climate change through transnational municipal networks. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 47(2), 309–332.

- King, R. F., & Borchardt, A. (1994). Red and green: Air pollution levels and left party power in OECD countries. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 12(2), 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1068/c120225

- Kjaer, U., & Elklit, J. (2010). Local party system nationalisation: Does municipal size matter? Local Government Studies, 36(3), 425–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003931003730451

- Krause, R. M. (2011). Policy innovation, intergovernmental relations, and the adoption of climate protection initiatives by US cities. Journal of Urban Affairs, 33(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2010.00510.x

- Kukovic, S., Copus, C., Hacek, M., & Blair, A. (2015). Direct mayoral elections in Slovenia and England: Traditions and trends compared. Lex Localis, 13(3), 697. https://doi.org/10.4335/13.3.697-718(2015)

- Laakso, M., & Taagepera, R. (1979). “Effective” number of parties: A measure with application to West Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 12(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041407901200101

- Leach, R. (1996). Green ideology. In R. Leach (Ed.), British political ideologies (pp. 261–283). Palgrave.

- Lee, T., & Koski, C. (2015). Multilevel governance and urban climate change mitigation. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 33(6), 1501–1517. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X15614700

- Lindblom, C. (1977). Politics and markets, the world’s political economic systems. Basic Books.

- Lönegren, L. (2009). The European Green Capital Award-towards a sustainable Europe? [Bachelor thesis]. Malmö Högskola.

- Magnier, A., Getimis, P., Cabria, M., & Baptista, L. (2018). Mayors and spatial planning in their cities. In H. Heinelt, A. Magnier, M. Cabria, & H. Reynaert, (Eds.), Political leaders and changing local democracy (pp. 411–445). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Manca, L. (2020). Green Capitals “in the hearts and minds of the people”. A qualitative enquiry into the perception of the influence of the European Green Capital Award among municipal officials [Master thesis]. Maastricht University.

- Marks, G., Wilson, C. J., & Ray, L. (2002). National political parties and European integration. American Journal of Political Science, 46(3), 585–594. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088401

- McCann, E. (2013). Policy boosterism, policy mobilities, and the extrospective city. Urban Geography, 34(1), 5–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2013.778627

- McPhearson, T., Parnell, S., Simon, D., Gaffney, O., Elmqvist, T., Bai, X., Roberts, D., & Revi, A. (2016). Scientists must have a say in the future of cities. Nature News, 538(7624), 165. https://doi.org/10.1038/538165a

- Meijering, J. V., Kern, K., & Tobi, H. (2014). Identifying the methodological characteristics of European green city rankings. Ecological Indicators, 43, 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2014.02.026

- Meijerink, S., & Stiller, S. (2013). What kind of leadership do we need for climate adaptation? A framework for analyzing leadership objectives, functions, and tasks in climate change adaptation. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 31(2), 240–256. https://doi.org/10.1068/c11129

- Mocca, E. (2017). City networks for sustainability in Europe: An urban-level analysis. Journal of Urban Affairs, 39(5), 691–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2017.1282769

- Mocca, E. (2021). The municipal gaze on the EU: European municipalism as ideology. Journal of Political Ideologies, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2021.1947571

- Mourao, P. R. (2019). The effectiveness of green voices in parliaments: Do green parties matter in the control of pollution? Environment, Development and Sustainability, 21(2), 985–1011. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-017-0070-2

- Mouritzen, P. E., & Svara, J. H. (2002). Leadership at the apex: Politicians and administrators in Western local governments. University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Müller-Rommel, F., & Poguntke, T. (1989). The unharmonious family: Green parties in Western Europe. In E. Kolinsky (Ed.), The greens in West Germany: Organisation and policy-making (pp. 11–29). Berg.

- Neidig, J., Anguelovski, I., Albaina, A., & Pascual, U. (2022). “We are the Green Capital”: Navigating the political and sustainability fix narratives of urban greening. Cities, 131, 103999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.103999

- Neumayer, E. (2003). Are left-wing party strength and corporatism good for the environment? Evidence from panel analysis of air pollution in OECD countries. Ecological Economics, 45(2), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(03)00012-0

- Nicolli, F., & Vona, F. (2019). Energy market liberalization and renewable energy policies in OECD countries. Energy Policy, 128, 853–867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.01.018

- Nijkamp, P., & Perrels, A. (1994). Sustainable cities in Europe. Routledge.

- North, P., Nurse, A., & Barker, T. (2017). The neoliberalisation of climate? Progressing climate policy under austerity urbanism. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(8), 1797–1815. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16686353

- Orderud, G. I., & Kelman, I. (2011). Norwegian mayoral awareness of and attitudes towards climate change. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 68(5), 667–686. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207233.2011.587648

- Pablo‐Romero, M. D. P., Sánchez‐Braza, A., & Manuel González‐Limón, J. (2015). Covenant of mayors: Reasons for being an environmentally and energy friendly municipality. Review of Policy Research, 32(5), 576–599. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12135

- Pantić, M., & Milijić, S. (2021). The European Green Capital Award—Is it a dream or reality for Belgrade (Serbia)? Sustainability, 13(11), 6182. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116182

- Parnell, S. (2016). Defining a global urban development agenda. World Development, 78, 529–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.028

- Pearson, M., & Rüdig, W. (2020). The greens in the 2019 European elections. Environmental Politics, 29(2), 336–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1709252

- Poguntke, T. (2002). Green parties in national governments: From protest to acquiescence? Environmental Politics, 11(1), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/714000585

- Porrit, J. (1984). Seeing green: The politics of ecology explained. Basil Blackwell.

- Portney, K. E., & Berry, J. M. (2010). Participation and the pursuit of sustainability in US cities. Urban Affairs Review, 46(1), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087410366122

- Prado-Lorenzo, J. M., García-Sánchez, I. M., & Cuadrado, B. (2010). Sustainable cities: Do political factors determine the quality of life? WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, 142, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2495/SW100041

- Price-Thomas, G. (2016). Green party ideology today: Divergences and continuities in Germany, France, and Britain. In E. van Haute (Ed.), Green parties in Europe (pp. 280–298). Routledge.

- Rode, P. (2013). Cities and the green economy. In R. Simpson & M. Zimmermann (Eds.), The economy of green cities: A world compendium on the green urban economy (pp. 79–98). Springer.

- Rooduijn, M., Van Kessel, S., Froio, C., Pirro, A., De Lange, S., Halikiopoulou, D., Lewis, P., Mudde, C., & Taggart, P. (2019). The PopuList: An overview of Populist, far right, far left and Eurosceptic parties in Europe. www.popu-list.org

- Saha, D. (2009). Factors influencing local government sustainability efforts. State and Local Government Review, 41(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X0904100105

- Savini, F. (2014). What happens to the urban periphery? The political tensions of postindustrial redevelopment in Milan. Urban Affairs Review, 50(2), 180–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087413495809

- Scheller, D., & Thörn, H. (2018). Governing ‘sustainable urban development’ through self‐build groups and co‐housing: The cases of Hamburg and Gothenburg. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 42(5), 914–933. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12652

- Scruggs, L. A. (1999). Institutions and environmental performance in seventeen western democracies. British Journal of Political Science, 29(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123499000010

- Sennett, R. (2014, October 9). Why climate change should signal the end of the city-state. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/oct/09/why-climate-change-should-signal-the-end-of-the-city-state

- Stavrakakis, Y. (1997). Green ideology: A discursive reading. Journal of Political Ideologies, 2(3), 259–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569319708420763

- Svirčić Gotovac, A., & Kerbler, B. (2019). From post-socialist to sustainable: The city of Ljubljana. Sustainability, 11(24), 7126. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247126

- Swianiewicz, P., Lackowska, M., & Hanssen, G. S. (2018). Local leadership in climate change policies. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 14(53), 67–83. https://doi.org/10.24193/tras.53E.5

- Talshir, G. (Ed.). (2002). The political ideology of green parties: From the politics of nature to redefining the nature of politics. Springer.

- van der Heijden, J. (2017). Innovations in urban climate governance: Voluntary programs for low carbon buildings and cities. Cambridge University Press.