ABSTRACT

While the importance of residential moves and neighborhood context for children is widely recognized, few studies examine childhood mobility and neighborhood context together and over time. Using a typology of mobility trajectories based on frequency, age, distance and change in population density, this study analyzes the interrelatedness between mobility trajectories and socioeconomic neighborhood composition throughout childhood. Using full-population register data, we follow children born in the Netherlands in 1999 until age 16. Local spatial autocorrelation analyses reveal concentrations of childhood mobility and neighborhood deprivation in cities. Focusing on children born in metropolitan areas, results indicate that children born in deprived neighborhoods are more likely to experience any move. Short-distance moves are associated with increased exposure and long-distance moves with less exposure to neighborhood deprivation. We argue we need a multidimensional longitudinal perspective to fully capture residential contexts to which children are exposed and enhance knowledge of childhood accumulations of disadvantage.

Introduction

The neighborhood context where children grow up is important in shaping their socialization and development and may have a long-term impact on later life chances. Moving and the accompanying change of neighborhood context might have negative consequences for children due to the stress of moving, a change in environment, a possible disrupted socioemotional development and school career, and the potential loss of social ties. However, when a family moves to a better neighborhood with, for example, better schools and housing quality, the move might actually benefit a child (Morris et al., Citation2018; Robertson et al., Citation2021). While the importance of both moving and neighborhood context for children has been widely recognized, there are still few empirical studies that analyze childhood internal mobility and neighborhood context simultaneously. The current study therefore assesses the interrelatedness between internal mobility and neighborhood context throughout childhood.

We take up a life course approach to understand neighborhood changes in a child’s life by integrating insights from the mobility and the neighborhood effects literature. Mobility is increasingly viewed from a life course perspective, recognizing that moving is multidimensional, relational, dynamic, and unfolding over time and space, and should therefore be studied longitudinally (Findlay et al., Citation2015). Recognizing the multidimensionality of individual mobility trajectories over time, at least four dimensions are important to consider when studying moving during childhood: the number of moves, the age at moving, the distance moved and the change in population density (Kuyvenhoven et al., Citation2022). With the increasing availability of longitudinal data, there is a growing body of studies integrating the life course perspective into research on neighborhood effects as well (see Sharkey & Faber, Citation2014 for an overview). The neighborhood context might change over the course of a child’s life either because a child moves or because the neighborhood itself changes due to migration, natural change, or changing characteristics of its residents (Kleinepier & van Ham, Citation2017; Vogiazides & Mondani, Citation2023). Longitudinal studies of neighborhood effects generally show that it matters how long (duration) and when (timing) a child lived in a neighborhood and whether neighborhood circumstances improved or deteriorated over time (sequencing; Kleinepier & van Ham, Citation2018).

Integrating these insights, the current study assesses internal mobility across multiple dimensions and its association to neighborhood context over the entire childhood. In order to capture the mobility dimensions of frequency, timing, distance and change in population density, we use a previously developed typology of childhood internal mobility trajectories: non-movers, nearby pre-school-aged movers, nearby school-aged movers, distant movers to more densely populated areas, distant movers to less densely populated areas, and frequent movers (as developed by Kuyvenhoven et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, we study exposure to neighborhood deprivation throughout the entire childhood. In doing so, we aim to better understand whether and under which circumstances moving during childhood relates to an improved neighborhood context or an accumulation of neighborhood deprivation in childhood.

The study uses full population register data on all children born in the Netherlands in 1999 and combines two analytical strategies to analyze the associations between mobility and neighborhood context throughout childhood. First, we use local spatial autocorrelations to visualize and analyze spatial concentrations of childhood internal mobility and neighborhood socioeconomic composition. Based on the results from this analysis, we select all children born in the metropolitan areas of the four largest cities in the Netherlands (Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, and Utrecht) for the second part of the study. Here, we use individual-level regression models to analyze the associations between (1) the socioeconomic composition of the neighborhood of birth and different childhood mobility trajectories and (2) different childhood mobility trajectories and exposure to neighborhood deprivation across a child’s life course.

Childhood internal mobility

Most studies on residential mobility and internal migration focus on the drivers of household (im)mobility. These studies underline that mobility is a complex social process, often triggered by important life events, such as union formation and dissolution, family expansion and changes in employment, and is related to sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, employment, income, housing tenure and marital status (Clark, Citation2013; Coulter et al., Citation2016; Coulton et al., Citation2012; Morris et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, preferences in housing, location and neighborhood conditions and whether those preferences are met in the current housing situation, influence moving desires. Opportunities and constraints in the housing market, as well as available resources, determine whether those moving desires result in an actual move (Clark & Coulter, Citation2015; Coulton et al., Citation2012; Morris et al., Citation2018; Owens & Clampet-Lundquist, Citation2017). While moving is often motivated by the desire for an improvement in housing conditions, the environment or job opportunities, it might also reflect instability in income, employment, or housing (Coulton et al., Citation2012). The same applies to immobility, which might reflect stability, but could also result from a lack of resources to improve one’s living conditions (Coulton et al., Citation2012). In addition to these general drivers of household mobility, migrant groups often have a higher mobility rate compared to the majority population. This may be attributable to settlement trajectories after an international move, but also to differences in demographic and socioeconomic characteristics (Andersson, Citation2012).

For the U.S., DeLuca and Jang–Trettien (Citation2020) show that the majority of moving decisions of low-income parents are reactive in response to housing insecurity with limited time and resources in the moving process. Consequently, the parents’ main priority is housing, while improving neighborhood conditions may be less important in the decision process. In combination with structural constraints in the housing market, this results in poor families moving within or between deprived areas, reinforcing urban inequality and segregation (DeLuca & Jang–Trettien, Citation2020; DeLuca et al., Citation2019). In contexts like the Netherlands, with a stronger welfare regime, social housing and tenant protections, direct displacement of low-income households is less common. However, neoliberal housing policies promoting homeownership over social housing and the resulting rising housing prices have made urban housing increasingly unaffordable and inaccessible for low-income households, resulting in the suburbanization of poor households (Hochstenbach & Musterd, Citation2018). This indirect displacement limits the mobility options of low-income households, which might affect their decision process as being mainly driven by a search for affordable housing.

There is a lack of quantitative research on the mobility patterns of children, since they are not considered active agents in the decision process and thus not the drivers of mobility (Morris et al., Citation2018). Children are, however, often an important reason for families to move to better or larger housing, a more child-friendly environment, or to gain access to better schools (McKendrick, Citation2001). Furthermore, some groups of children are more likely to move than others. Mobility is especially high among very young children (ages 0–4)—which is often attributed to family expansion and the accompanying changing housing needs—after which mobility declines until adolescence (McKendrick, Citation2001). Young children thus often move due to a strategic parental motivation to live in a more appropriate home and neighborhood for raising children. On the other hand, moving frequently throughout childhood is arguably the result of instability and disadvantageous family situations. Several studies have indeed shown that frequent moving during childhood is associated with poverty, parental unemployment, parental union dissolution and single parenthood (Jelleyman & Spencer, Citation2008; Murphey et al., Citation2012).

Moving during childhood is often theorized as a stressful and disruptive experience with negative implications for children due to disruptions to development, school career and social ties and the accompanying social and environmental changes to which children are more sensitive than adults (Morris et al., Citation2018). On the other hand, moving might have positive implications for a child when it involves a move to a better environment, which is often theorized to be the main motivation for families with children to move (Morris et al., Citation2018; Robertson et al., Citation2021). The potential consequences of childhood mobility have been studied for various outcomes (for a review, see Cotton, Citation2016 on problem behavior; and Jelleyman & Spencer, Citation2008; Simsek et al., Citation2021 on health-related outcomes). However, the empirical findings show inconsistent results regarding the negative or positive implications of moving (Bernard & Vidal, Citation2020). Since the impact of moving might depend on how often, when and how far a child moves, it is important to differentiate between different dimensions of mobility to better understand its consequences.

The most consistent finding across several studies is the negative impact of moving frequently, indicating a non-linear effect of mobility with additional moves having increasingly more impact (Leventhal & Newman, Citation2010). This suggests a cumulative effect of moving, often attributed to the impact of multiple disruptions and instability throughout childhood (Mollborn et al., Citation2018). Frequent movers are, however, also overrepresented among children growing up in families with other disadvantageous background characteristics (Murphey et al., Citation2012; Vidal & Baxter, Citation2018). Regarding the timing of moving, empirical findings suggest that moves during adolescence are most detrimental (Simsek et al., Citation2021). Adolescence is an important developmental period during which important friendship ties are established, which may be disrupted when moving (Li et al., Citation2019). Regarding the distance of the move, empirical findings are more ambiguous. While some studies find a negative impact of moving over long distances (Gillespie, Citation2013 on problem behavior; Price et al., Citation2018 on psychotic disorder), others find a positive impact (Vidal & Baxter, Citation2018 on school performance; Vogel et al., Citation2017; Widdowson & Siennick, Citation2021 on delinquency). While long-distance moves are theorized to be more disruptive to social ties, education and family life (Gillespie, Citation2013), this might in some cases work as a protective factor when disrupting negative peer relations (Vogel et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, long-distance moves are more often strategic and motivated by employment or other positive changes, while short-distance moves are more heterogeneous including negative drivers such as unemployment or union dissolution, implying that the positive or negative impact of moving partially depends on the motivation of the move (Morris et al., Citation2018).

Childhood neighborhood context and effects

Neighborhoods are important contexts for the socialization and development of children, since children rely more on their immediate surroundings for social interactions and peer networks than adults (Anderson et al., Citation2014; Morris et al., Citation2018). Empirical studies have shown that growing up in a disadvantaged neighborhood negatively affects child development, education, health and various behavioral and emotional problems (Anderson et al., Citation2014; Brandén et al., Citation2022; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, Citation2000). Several mechanisms have been theorized to be important for these so-called neighborhood effects, such as social isolation, limited social control and social cohesion, negative peer relations, the absence of positive role models, and a lack of important institutions (see Galster, Citation2012; Jencks & Mayer, Citation1990 on mechanisms of neighborhood effects).

Although the impact of neighborhood context on child development and well-being has gained a lot of attention across disciplines, there is still no consensus on the relative importance of the neighborhood. While most studies find a negative impact of concentrated disadvantage, the effects are small and largely reduced after taking into account individual, family, and school characteristics (Nieuwenhuis & Hooimeijer, Citation2016). An important argument for the relatively small effects of the neighborhood context is that until recently, most empirical studies relied on a point-in-time measure of the neighborhood. Wheaton and Clarke (Citation2003) argued that this static measure of the neighborhood context might underestimate its importance and that empirical studies should therefore take up a temporal life course approach to assess neighborhood effects. Such a perspective builds on the idea that the impact of the residential neighborhood largely depends on how long and when a child lived in that neighborhood (Sharkey & Faber, Citation2014).

With the increasing availability of longitudinal data, a growing body of research has been developed focusing on trajectories of neighborhood deprivation and duration and timing of exposure to neighborhood deprivation (Lee et al., Citation2017). These studies generally find that long-term exposure to deprivation has a more severe impact on child development, suggesting a cumulative impact of exposure to neighborhood deprivation (Crowder & South, Citation2011; Kleinepier & van Ham, Citation2018; Wodtke, Citation2013; Wodtke et al., Citation2011). Studies focusing on timing generally find a larger impact of neighborhood deprivation when experienced during adolescence (Kleinepier & van Ham, Citation2018; Wodtke et al., Citation2016). Neighborhood context should thus not be treated as static, but rather as a dynamic feature of a child’s life, recognizing that the neighborhood context might change over a child’s life course, either because a child moves to a different type of neighborhood or because the neighborhood itself changes (Kleinepier & van Ham, Citation2017). Kleinepier and van Ham (Citation2017) show, however, that children who moved at least once have much lower stability in neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics compared to non-movers, suggesting that geographical mobility is related to neighborhood socioeconomic mobility as well. In contrast, they find that children of immigrants have a higher stability in neighborhood characteristics throughout childhood despite their higher mobility rates compared to the majority population, suggesting that they are more likely to move within or between neighborhoods with similar compositions (Kleinepier & van Ham, Citation2017). Other studies also find relatively stable neighborhood trajectories among migrant populations, with the majority consistently residing in a disadvantaged neighborhood (Kleinepier et al., Citation2018; Vogiazides & Chihaya, Citation2020).

Childhood internal mobility and neighborhood context

Building on the life course perspective, both strands of literature on internal mobility and neighborhood effects have developed in similar ways in underlining the importance of accumulations, timing, and sequencing of events. In the mobility literature, the neighborhood is recognized as an important factor in explaining why moving might have negative or positive implications, especially in acknowledging that upward neighborhood mobility might compensate for the negative impact of moving, and actually lead to benefits (Robertson et al., Citation2021). In the neighborhood effects literature, mobility is considered an important factor for changes in the neighborhood context throughout childhood (Kleinepier & van Ham, Citation2017). Nevertheless, few studies have looked at the impact of moving and the neighborhood contexts throughout childhood simultaneously.

An exception is the study by Flouri et al. (Citation2013) who studied residential mobility and neighborhood deprivation simultaneously for the UK. They found that living in a less deprived neighborhood was associated with lower emotional and behavioral problems, but children who had moved were at a higher risk for emotional and behavioral problems, regardless of the composition of the destination neighborhood. These findings suggest a separate impact of mobility. In contrast, for the U.S., Mollborn et al. (Citation2018) found a negative impact of moving for behavioral problems, but only for frequent moves, moves to a different neighborhood, and for moves to a less advantaged neighborhood, but not for moves within the same neighborhood or to a more advantaged neighborhood. These findings suggest that the impact of moving depends on the type of move a child experiences, as well as on the socioeconomic composition of the origin and destination neighborhoods. Combining the spatial and temporal dimensions, Chetty et al. (Citation2016) find that moving to a lower poverty neighborhood at a young age (before 13) had a positive impact on college attendance and income and reduced the chance of becoming a single parent, while moving to a lower poverty neighborhood in adolescence had negative effects. Taken together, these studies call for more knowledge on the association between childhood mobility and neighborhood deprivation over time.

Research questions and hypotheses

This study takes up a life course approach in studying the association between childhood internal mobility trajectories and neighborhood context throughout childhood. We consider four dimensions of moving during childhood that are important from a life course perspective: the number of moves, the age at moving, the distance moved and the change in population density (Kuyvenhoven et al., Citation2022). Acknowledging the importance of timing and duration of exposure to neighborhood context, we analyze neighborhood socioeconomic composition at birth as well as cumulatively throughout childhood. We focus on the Dutch context in addressing the following research questions: First, how is the socioeconomic composition of the neighborhood of birth associated with different mobility trajectories during childhood? (RQ1). Second, how do different childhood mobility trajectories relate to exposure to neighborhood deprivation throughout childhood? (RQ2). We identify three processes that might influence the association between mobility and neighborhood context during childhood based on the literature on general patterns of (household) mobility (Clark, Citation2013; Coulter et al., Citation2016; Coulton et al., Citation2012; Morris et al., Citation2018). First, moving is often motivated by a desire for improvement, with families moving to a better environment for raising children (upward mobility). Second, mobility might reflect instability, as disadvantageous families may move due to socioeconomic insecurity or an unstable family situation (instability). Finally, some families might prefer to move but lack the resources to do so (limited opportunities; Coulton et al., Citation2012).

Building on these theoretical ideas, we propose two competing hypotheses regarding RQ1. On the one hand, children born in more deprived neighborhoods might experience higher mobility either due to upward mobility or due to instability (H1a). Building on the idea of upward mobility, they might especially experience higher mobility at younger ages since families tend to search for better living conditions before children start school (Morris et al., Citation2018). Building on the idea of instability, children might move more frequently when they experience socioeconomic or family instability (Mollborn et al., Citation2018). Conversely, however, children born in more deprived neighborhoods might experience lower mobility due to limited opportunities or resources to move (H1b), which might limit distant moves, for which generally more resources are needed.

Similarly, we propose two competing hypotheses regarding RQ2. On the one hand, mobility might be related to lower levels of exposure to neighborhood deprivation throughout childhood, due to upward mobility of resourceful families and immobility among families with limited resources (H2a). Upward mobility might be especially salient among young children, a period in which families move due to changing housing needs, and among those born in deprived neighborhoods, which increases the likelihood that there is a mismatch between the current and preferred living situation. On the other hand, mobility might be related to higher levels of exposure to neighborhood deprivation throughout childhood, due to socioeconomic insecurity and family instability of children who move (H2b). This instability might be especially salient among frequent movers, but also among children moving close to their first place of residence, since short-distance moves are more often forced due to, for example, parental job loss or union dissolution (Morris et al., Citation2018).

The Dutch context

Internal mobility rates in the Netherlands are relatively high compared to those in other European countries (Bernard & Vidal, Citation2020). This also applies to children; 61% of the Dutch children move at least once between the ages of 0 and 16 (Kuyvenhoven et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, children of immigrants in the Netherlands move more often, but mobility patterns vary by migrant origin group. Differences in migration histories, demographic and socioeconomic compositions, as well as patterns of household transitions between migrant origin groups arguably explain this variation (Kuyvenhoven et al., Citation2022). In the Netherlands, important motivations for families to move are related to changing housing needs due to changes in the household composition, such as union formation and dissolution and the birth of a child (De Groot et al., Citation2011). In many metropolitan regions, mobility of families is often related to preferences for better or larger housing (Booi et al., Citation2021). The tight housing market in Dutch cities might, however, restrict especially low-income families to move to their preferred housing. There indeed seems to be a growing socioeconomic divide in access to homeownership, which might result in increasing socio-spatial inequalities (Arundel & Hochstenbach, Citation2020). Nevertheless, segregation of both poverty and affluence is still smaller in Amsterdam compared to many other European capital cities (Haandrikman et al., Citation2023).

Data and methods

This study combines two methodological approaches. In Part I, we used spatial autocorrelation techniques to identify associations between spatial patterns of childhood internal mobility and the socioeconomic composition at the neighborhood-level. Based on the results from these exploratory spatial analyses, for the second part of the study we selected all children born in the metropolitan areas of the four largest cities in the Netherlands (Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, and Utrecht). In Part II, we analyzed the associations between mobility and socioeconomic neighborhood context for individual children, following them through childhood, using regression models.

Data

This study used linked population data from administrative registers from the System of Social Statistical Datasets (SSD) of Statistics Netherlands containing demographic, socioeconomic, and spatial data for the entire Dutch population. The research population consisted of all children born in the Netherlands in 1999 who lived in the country for 16 consecutive years. Excluding children who experienced an international migration during childhood allowed us to analyze the full internal mobility pattern of our research population between ages 0 and 16. Additionally, we excluded children who lived in an institutional household for over half a year. From this population, we selected a random sample of one child per household, resulting in a total subset of 182,430 children. Using anonymized personal IDs, we linked children to all their home addresses in the study period, with moves operationalized as any move between addresses where a child resided for at least 45 days.

For the neighborhood-level data, we aggregated individual-level data for the entire Dutch population on the first of January for the years 1999–2015 to the smallest administrative neighborhood units (buurten) using the 2019 neighborhood boundaries (13,594 neighborhoods). We constructed five indicators of neighborhood socioeconomic status for each year in the study period: the proportion of the working-age population that is (1) employed; and (2) receiving social benefits; the proportion of households (3) with a low income (lowest quintile); and (4) with a high income (highest quintile); and (5) the median standardized household income. In order to reduce problems of multicollinearity and to create a comprehensive measure of neighborhood socioeconomic status, we performed Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for each year using these socioeconomic neighborhood variables. To test the suitability of the variables for PCA, we performed KMO tests and Bartlett’s test that indicated substantial correlations. PCA revealed that all variables loaded onto one factor, explaining between 63% and 73% of the total variance for the different years. The resulting factor score indicates neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES), with a higher value reflecting a higher neighborhood SES ().

We then linked the neighborhood SES score to the neighborhoods of all the addresses where the children in the study population lived during childhood. The final subset included 180,526 children, born in 10,884 neighborhoods for whom mobility and the neighborhood context could be analyzed for all 16 years of childhood.

Part I: Neighborhood-level spatial concentrations of mobility and socioeconomic status

For Part I, we selected all neighborhoods where in 1999 at least one child in the study population resided, had a known SES score, and had at least one adjacent neighborhood with a known SES score. For these 10,725 neighborhoods, we measured (1) childhood mobility as the proportion of children born in the neighborhood who moved at least once during childhood and (2) neighborhood SES as the socioeconomic status factor score.

We examined the spatial concentration of childhood mobility and neighborhood SES using Moran’s I. This is a widely used measure for spatial autocorrelation to assess whether a spatial distribution of a phenomenon is clustered, dispersed, or random. A negative value indicates spatial dissimilarity, whereas a positive value represents spatial similarity of the indicators between adjacent neighborhoods. We used a queen’s contiguity row-standardized weights matrix indicating the spatial structure in the data, in which neighborhoods are considered contiguous when bordering one another. For both neighborhood childhood mobility and SES, we calculated (1) Global Moran’s I to identify general spatial patterns for contiguous neighborhoods across the total neighborhood sample and (2) Local Moran’s I (LISA) to identify local spatial patterns for each neighborhood in relation to adjacent neighborhoods. We also calculated the global and local bivariate Moran’s I to examine the spatial correlation between childhood mobility and neighborhood SES. Here, a negative value indicates dissimilarity between concentrations of childhood mobility and (neighboring) socioeconomic status across space and a positive value indicates similarity. We used the R spdep package to calculate spatial statistics and QGIS for visualization.

We follow the strategy proposed by Ingram and Harbers (Citation2020) to use the LISA statistics for case selection to select regions with the most evident concentrations of and associations between childhood mobility and neighborhood socioeconomic status. Based on the spatial analyses, revealing that childhood mobility and neighborhood deprivation concentrate in cities, we focused further in-depth quantitative analyses on the metropolitan areas of the four largest cities of the Netherlands: Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, and Utrecht.

Part II: Individual-level regression models

In Part II, we selected all children in the study population who were born in one of these four metropolitan areas (N = 49,391). Excluding records with missing values in one or more of the variables in the analyses resulted in a subset of 45,784 children born in 2,051 neighborhoods. We used the childhood mobility trajectories and neighborhood SES as the main indicators in these analyses and accounted for several background characteristics.

The childhood mobility trajectories were based on a previously developed typology of childhood mobility patterns which was constructed using K-means cluster analysis for four indicators of mobility (see Kuyvenhoven et al., Citation2022): frequency (the number of moves between ages 0–16), timing (the age of the first move), distance (the average distance of all moves), and change in population density (the difference in population density between the first and the last address). This cluster analysis revealed six clusters of childhood mobility trajectories: (1) non-movers; (2) nearby pre-school-aged movers; (3) nearby school-aged movers; (4) distant movers to more densely populated areas; (5) distant movers to less densely populated areas; and (6) frequent movers. While it is possible for children to have mobility trajectories that resemble multiple categories, such as those in the “frequent movers” category also moving long distances, it is important to note that these categories are mutually exclusive. Each child is uniquely assigned to a single category, determined by its deviation from the group mean. shows the different childhood mobility trajectories and how they vary across the four mobility indicators.

Table 1. Mobility indicators for the childhood mobility trajectories of children born in metropolitan areas who moved (N = 30,675).

Table 2. Socioeconomic characteristics of origin neighborhoods in metropolitan areas.

For this part of the analysis, we classified the neighborhood SES factor score for all neighborhoods in the Netherlands into neighborhood SES quintiles ranging from (1) very deprived to (5) very affluent. We used two variables of neighborhood SES in the analyses. First, neighborhood of origin SES quintiles was based on the neighborhood SES quintile for each child’s first address in 1999. shows the socioeconomic indicators used in the PCA and the mean SES factor score by the neighborhood of origin SES quintiles. The second measure of neighborhood SES is the duration of exposure to neighborhood deprivation, measured as the years in childhood (age 0–16) a child resided in a most deprived neighborhood (Q1). Since neighborhood quintiles can change between years, and as children may move to other neighborhoods within a year, we measured duration of exposure to neighborhood deprivation as follows: the days a child resided on an address in a Q1 neighborhood in a given year; summarized for all addresses and years; and converted into years, resulting in a measure ranging from 0 to 16 years.

We controlled for several background characteristics of the children (migrant background, gender), their family (socioeconomic status, household composition), and place of birth (urbanity, metropolitan area) in the models. Children of immigrants are all children born in the Netherlands with at least one foreign-born parent. We define country of origin based on the mother’s country of birth and if the mother is born in the Netherlands, the father’s country of birth. We categorized migrant origin into six groups: (1) no migrant background, (2) Moroccan, (3) Turkish, (4) Surinamese, (5) Antillean, (6) other migrant background. We included gender in the models as (1) male or (2) female. We operationalized parental employment as a continuous measure for both parents separately as the years in employment averaged over 16 years, based on semiannual employment status. We measured household income as the annual standardized household income in euros averaged over 11 years (child aged 5–15) since data on income are only available from 2003 onward. We used the log of household income centered around the mean. To account for the household composition during childhood, we compared parental union at birth with parental union at age 16 and categorized parental union as (1) stable union (parents remained together throughout childhood), (2) union dissolution (parents divorced or separated), (3) single parent (parents never lived together throughout childhood, possibly re-partnered), (4) started living together (parents lived apart at birth and started living together). We included the degree of urbanity for the municipality of birth based on the average address density measured as the number of surrounding addresses per km2 and categorized as (1) low (<1,000), (2) moderate (1,000–1,500), (3) high (1,500–2,500), and (4) very high urbanity (≥2,500). Finally, we controlled for the metropolitan area of birth: (1) Amsterdam, (2) Rotterdam, (3) The Hague, and (4) Utrecht.

We use two approaches to examine the associations between childhood internal mobility and neighborhood context. First, we analyzed the association between the neighborhood of origin SES and different childhood mobility trajectories (RQ1). Here, we use the childhood mobility trajectories as a dependent variable in a multinomial logistic regression model, using non-movers as the base-category. The main independent variable is a neighborhood of origin SES quintile. Second, we analyzed the association between childhood mobility trajectories and duration of exposure to neighborhood deprivation throughout childhood (RQ2). Here, we analyze the duration of exposure to neighborhood deprivation as a dependent variable in a linear regression model. The main independent variable was the childhood mobility trajectory. Additionally, we conducted this analysis separately for different neighborhoods of origin SES quintiles. For all models, we use robust standard errors clustered by the origin neighborhood to account for the clustering of individuals in neighborhoods. We used Stata mlogit and regress for the analyses.

Results

Spatial concentrations of mobility and neighborhood socioeconomic status

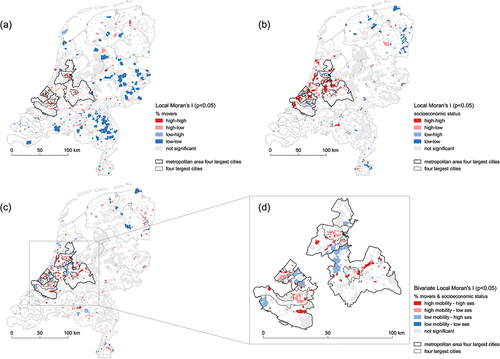

Results of the spatial analyses show that both childhood mobility rates and neighborhood socioeconomic status are clustered in space. Global Moran’s I for both childhood mobility (I = 0.228) and neighborhood SES (I = 0.403) are positive and significant (p < .001). This indicates similarity between neighborhoods and their adjacent neighborhoods on both indicators, in other words, neighborhoods with high and low values on the indicators are spatially clustered. The results of Local Moran’s I reveal regional differences in the spatial patterns of similarity. For childhood internal mobility (), spatial clusters of high mobility are most evident in cities (high–high), while clusters of low mobility are found in more rural areas in the east and south of the Netherlands (low–low). For neighborhood SES (), spatial clusters of deprivation are again manifested in cities, as well as in some rural areas in the north (low–low) while clusters of affluence are mostly evident in less urban areas surrounding the larger cities (high–high).

Figure 1. Local spatial autocorrelation (Moran’s I) of neighborhood (a) childhood mobility rates and (b) socioeconomic status; and bivariate local spatial autocorrelation (Moran’s I) of neighborhood childhood mobility rates and socioeconomic status for (c) the total country and (d) metropolitan areas. (p < .05).

Considering the spatial correlation between childhood mobility and neighborhood socioeconomic status, the results show a negative (but weak) and significant (p < .001) bivariate Global Moran’s I (I = −0.074), indicating that childhood mobility is spatially associated with (neighboring) concentrations of deprivation, while immobility is spatially associated with concentrations of affluence. shows the bivariate local Moran’s I, which confirms the spatial patterns presented in . We find concentrations of high mobility-low SES mostly in the larger cities and spatial clusters of low mobility-high SES and high mobility-high SES mainly in the less urban surrounding areas. Spatial associations between childhood mobility and socioeconomic status are especially evident in the four largest cities and their surrounding areas (Bivariate Global Moran’s I = −0.180). Based on these results we therefore selected children born in these metropolitan areas (Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, and Utrecht) for further analyses ().

Childhood mobility and neighborhood socioeconomic status in metropolitan areas: Descriptives

shows descriptive statistics for the study population for all children born in the Netherlands and for children born in the selected metropolitan areas, the latter being selected for the individual-level analyses. As expected from the spatial analyses, childhood mobility is somewhat higher among children born in metropolitan areas, with 67% of children moving at least once compared to 59% among all children. Especially longer-distance moves to less densely populated areas are more common among children from metropolitan areas, which points to family moves out of the cities. Again, in line with the findings from the spatial analyses, children from metropolitan areas are more often born in the most deprived (29%) as well as the least deprived (31%) neighborhoods compared to all children (22% and 19%, respectively). These children also live on average more years in a highly deprived neighborhood (4.3 years vs. 3.5 years) between ages 0–16. In metropolitan areas, more children have immigrant parents (31% vs. 17%), as the share of migrants is higher in these areas. The labor force participation of both mothers and fathers is slightly lower among children in metropolitan areas, but the average household income is somewhat higher. In metropolitan areas, children more often grow up in single-parent households. Taken together, these findings confirm that children in metropolitan areas are at higher risk of multiple adversities in terms of mobility, neighborhood context as well as family-level context.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics on the selected study population for all children born in the Netherlands (N = 169,870) and children born in the metropolitan areas (N = 45,784).

Neighborhood of origin socioeconomic status and childhood mobility in metropolitan areas

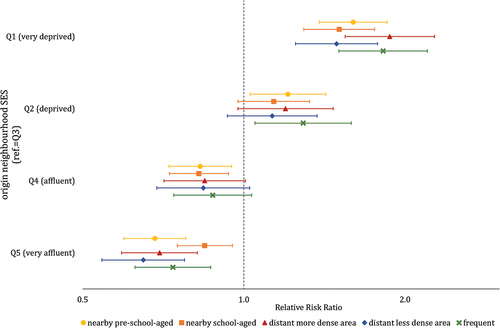

Using a multinomial logistic regression model, we first analyze the relative risk of experiencing a mobility trajectory in childhood compared to not moving (reference-category) by neighborhood of origin SES, controlling for migrant background, gender, parental SES, parental union, degree of urbanity, and metropolitan area of birth. shows the relative risk ratios of the childhood mobility trajectories by the neighborhood of origin SES quintiles for this model (see in the appendix for the full model). Results indicate that children born in a very deprived neighborhood (Q1) are significantly more likely to experience any kind of mobility trajectory compared to children born in an intermediate neighborhood. They are especially more likely to move longer distances to more densely populated areas and to move frequently. Children born in a deprived neighborhood (Q2) are also more likely to experience any mobility trajectory, but differ only significantly from children born in intermediate neighborhoods in moving nearby at a pre-school age or moving frequently. Children born in a more affluent neighborhood (Q4 & Q5), on the other hand, are less likely to move: children born in an affluent neighborhood (Q4) are significantly less likely to move nearby, at both pre-school and school ages, while children born in the most affluent neighborhoods (Q5) are less likely to make any move.

Figure 2. Relative risk ratios childhood mobility trajectories (ref. = non-movers) by neighborhood of origin SES quintile (ref. = intermediate) controlling for background characteristics for children born in the metropolitan areas (N = 45,784).

Regarding other background characteristics included in the model, results generally show that children of immigrants are more likely to move: children of Moroccan or Turkish parents are more likely to move nearby, children of Surinamese parents to move to more distant and densely populated areas, and children of Antillean parents to make any move with the exception of moving to less densely populated areas. Labor force participation of the father increases the likelihood of experiencing any move except moving frequently, while labor force participation of the mother only increases the likelihood of moving nearby at pre-school ages. A higher household income is associated with a higher likelihood of making any move except moving frequently. Children whose parents are not in a stable union throughout childhood are more likely to make any move, and especially moved frequently. Being born in an urban area increases the likelihood of moving nearby at pre-school ages, moving long-distance and moving frequently.

Childhood mobility and exposure to neighborhood deprivation in metropolitan areas

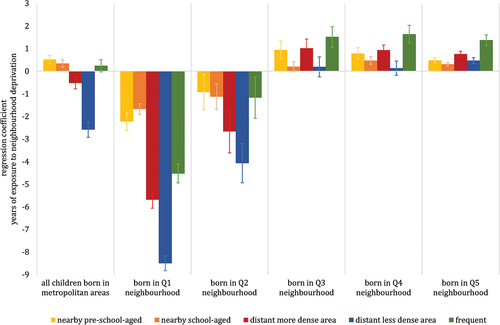

The final analysis examines how childhood mobility is associated with duration of exposure to neighborhood deprivation for children in metropolitan areas, using a linear regression model. The results show that mobility trajectories are associated with the duration of exposure to deprivation in varying ways (see appendix for results of the full models). shows the years of exposure to neighborhood deprivation by the mobility trajectories, controlling for several background characteristics for all children in the metropolitan areas, and separately modeled for the different SES quintiles of the origin neighborhood. Results for all children in metropolitan areas (left panel) show that children moving nearby (both pre-school and school-aged) are significantly longer exposed to neighborhood deprivation throughout their childhood, compared to children who do not move. Frequent movers also experience somewhat longer exposure to neighborhood deprivation but do not differ significantly from children who do not move. Children moving distantly (both to a more or less densely populated area), on the other hand, are significantly less exposed to neighborhood deprivation compared to non-movers.

Figure 3. Years of exposure to neighborhood deprivation by childhood mobility trajectory (ref.=non-movers) controlling for background characteristics for children born in the metropolitan areas (N = 45,784) and by neighborhood of origin SES (Q1: N = 13,170; Q2: N = 5,249; Q3 = 5,256; Q4: N = 7,719; Q5 = 14,390).

The extent to which a child experiences neighborhood deprivation throughout childhood partly depends on their neighborhood of birth. Therefore, in separate analyses, we also analyzed the duration of exposure to neighborhood deprivation by mobility trajectory for the different neighborhood of origin quintiles. shows that among children born in the most deprived neighborhoods (Q1–Q2), the duration of exposure to neighborhood deprivation is lower among those who moved compared to those who stay, which is especially evident among children moving longer distances. On the other hand, children born in intermediate neighborhoods (Q3) and in the most affluent neighborhoods (Q4–Q5) are more exposed to deprivation when moving. This difference is most evident for those who move frequently and, to a somewhat lesser extent, those moving longer distances to a more densely populated area.

The duration of exposure to neighborhood deprivation is furthermore generally higher for children of immigrant parents. Children of Turkish and Antillean parents only experience a higher exposure to neighborhood deprivation when born in a (very) deprived neighborhood, while children of Moroccan, Surinamese, and other origins experience higher exposure when born in any type of neighborhood, compared to children of non-migrant parents born in similar neighborhoods. Children who experienced parental union dissolution or lived in a single-parent household throughout childhood experience more years of exposure to neighborhood deprivation compared to children who consistently lived with both parents, regardless of the socioeconomic composition of the neighborhood they were born in. Children born in (highly) urban areas in all types of neighborhoods are also more exposed to neighborhood deprivation. Employment status of the mother and father as well as household income, on the other hand, is associated with lower exposure to neighborhood deprivation in all types of neighborhoods of origin.

Discussion and conclusion

We find that childhood internal mobility is associated with exposure to neighborhood deprivation. This association is, however, not one-dimensional; it depends on the mobility trajectory a child experiences—in terms of frequency of moves, age at moving, distance of moves, and change in population density—as well as the socioeconomic status of the neighborhood they were born in. This multidimensionality of moving experiences and exposure to neighborhood deprivation clearly underlines the importance of the simultaneous study of mobility and neighborhood context throughout childhood to enhance our knowledge on how and for whom moving might have long-term consequences. This study aims at better understanding the interrelatedness between different mobility trajectories and neighborhood SES during childhood by analyzing the associations between (1) the socioeconomic status of the neighborhood of origin and different childhood mobility trajectories and (2) different childhood mobility trajectories and exposure to neighborhood deprivation throughout childhood.

First, the study showed that children born in more deprived neighborhoods are more likely to experience any mobility trajectory as opposed to not moving, which is in line with the upward mobility and instability hypothesis (H1a). Results indicated that children born in the most deprived neighborhoods are particularly more likely to move over longer distances, to more or less densely populated areas. The latter might be indicative of upward mobility of families moving out of the city to a more child-friendly environment (Coulton et al., Citation2012). The likelihood of moving close by at pre-school and school ages and to move frequently is also considerably higher for children born in the most deprived neighborhoods. For those mobility trajectories, especially frequent moves, this might also reflect moves due to insecurities (Coulton et al., Citation2012). Although these results indicate high mobility among children born in deprived areas, there might thus be differences in the underlying processes between the different mobility trajectories.

Second, results showed that children who move generally experience more neighborhood mobility in terms of the socioeconomic composition than non-movers, which is in line with the findings of Kleinepier and van Ham (Citation2017). We show, however, that the direction of neighborhood change depends on the mobility trajectory as well as the socioeconomic composition of the neighborhood they were born in. In terms of mobility trajectory, nearby pre-school and school-aged moves are associated with longer exposure to neighborhood deprivation, confirming the instability hypothesis (H2b). We hypothesized this to be especially evident among frequent movers and among children moving nearby, but the results only confirmed the latter, which could be indicative of short-distance moves being more often forced, due to limited choice, insecurity, and instability. Distant moves, on the other hand, are related to lower exposure to neighborhood deprivation, confirming the upward mobility hypothesis (H2a). These results seem to indicate that moves over somewhat longer distances are made to improve a child’s living environment, which seems in line with the suburbanization pattern of families in the Netherlands (Booi et al., Citation2021). Overall, children moving nearby are thus experiencing higher levels of neighborhood deprivation and might, in combination with their moving experiences, be more prone to an unstable childhood, while children moving over longer distances are more likely to experience upward neighborhood mobility, which might compensate for the negative experiences of moving. The possible positive implications of moving to a better neighborhood should be studied more extensively given the inconsistent findings in previous studies (Chetty et al., Citation2016; Flouri et al., Citation2013; Mollborn et al., Citation2018).

The relationships between different childhood mobility trajectories and exposure to neighborhood deprivation depend on the type of neighborhood a child was born in. Children born in more affluent and intermediate SES neighborhoods who move experience a higher exposure to neighborhood deprivation compared to non-movers. In line with the instability hypothesis (H2b), this is especially evident among frequent movers. Children born in somewhat more deprived neighborhoods are less exposed to accumulative neighborhood deprivation when they move nearby during school age and when they move over a longer distance. Children born in the most deprived neighborhoods clearly have the largest benefits from moving, which is evident for all moves. In particular, children moving long distance to less densely populated areas show a very large decrease in the years of exposure to neighborhood deprivation, pointing to the upward mobility of suburbanizing families.

Taken together, these results imply that children who are born in a more deprived neighborhood have a higher likelihood of moving, making them more prone to the negative effects of moving. But those who move are generally less exposed to accumulated neighborhood deprivation, especially when moving longer distances, which might compensate for the negative impacts of moving. Children born in a more affluent neighborhood, on the other hand, have a lower likelihood of moving during childhood. But those who do move are more exposed to neighborhood deprivation, making them more vulnerable to negative neighborhood effects. Additionally, children of immigrants are more likely to move and generally experience higher levels of exposure to neighborhood deprivation. Children from more affluent families—in terms of parental employment and household income—are more likely to move both to nearby and distant areas and experience lower exposure to neighborhood deprivation. Children from unstable families—in terms of parental dissolution and single parenthood—are more likely to experience any mobility trajectory (as opposed to not moving) and experience higher exposure to neighborhood deprivation. This diversity in mobility and exposure to neighborhood deprivation underlines the complexity of processes of mobility (Clark, Citation2013; Coulter et al., Citation2016; Coulton et al., Citation2012; Morris et al., Citation2018), as well as the importance of considering the temporal dynamics of neighborhood context (Kleinepier & van Ham, Citation2018; Sharkey & Faber, Citation2014).

Our results have important implications for how we study contextual effects during childhood. A one-dimensional and static perspective on mobility and neighborhood context might mask the underlying complexity and variation in the residential contexts to which children are exposed. Therefore, when studying neighborhood effects, one should consider how long children are exposed to affluence or deprivation, and what their starting point on the housing market is. Furthermore, the study shows that some forms of mobility reflect an upward trajectory while other forms of mobility are more indicative of instability. These findings suggest that there might be large variations in the impact of moving, which adds to our understanding of the seemingly mixed findings regarding neighborhood and mobility effects for individual outcomes (Chetty et al., Citation2016; Flouri et al., Citation2013; Mollborn et al., Citation2018) and calls for a multidimensional longitudinal approach in studying mobility and neighborhood effects simultaneously in future research. Children experiencing unstable mobility trajectories—such as those moving frequently, between or within deprived neighborhoods, or due to parental union dissolution—might be particularly vulnerable and in need of support in adjusting to a new environment. Finally, the results point to selection into different mobility and neighborhood trajectories for different groups of children, which may reinforce segregation patterns, and the intergenerational transmission of neighborhood deprivation. Since already vulnerable groups of children experience both higher mobility and increased neighborhood deprivation, this might result in increasing segregation. Given that previous studies show that neighborhood deprivation is persistent and transmitted between generations, these patterns might have long-term consequences for socio-spatial inequalities (Gustafsson et al., Citation2017; Sharkey, Citation2008; Van Ham et al., Citation2014).

Separate regression models based on the type of neighborhood of origin confirm the upward neighborhood mobility for movers among those born in the most deprived neighborhoods. However, those who move might move to a slightly less deprived neighborhood, and thus do not experience a substantial change in neighborhood context. One disadvantage of the used measure of exposure to neighborhood deprivation—years lived in most deprived neighborhoods—is that those who are born in a most deprived neighborhood and do not move will most likely have the highest exposure to deprivation. This is particularly plausible since we know from previous studies that children who do not move experience little change in their neighborhood context (Kleinepier & van Ham, Citation2017). We therefore also analyzed cumulative exposure to neighborhood deprivation as the sum of the neighborhood socioeconomic status score to check the robustness of our findings, which showed similar results. Nevertheless, there might still be variations in the trajectories of mobility and exposure to neighborhood deprivation, and therefore future research should look into the sequencing of mobility and neighborhood context. Additionally, staying in the most deprived neighborhood throughout childhood might actually be more beneficial compared to moving to a slightly less deprived neighborhood since children who stay do not experience a disruption of their local social network. Future research should therefore not only consider neighborhood socioeconomic context but also neighborhood social cohesion and the disruption of a child’s own social network.

Our study controlled for a range of background characteristics that are known to be associated with mobility as well as neighborhood deprivation (i.e., migrant background, family SES, household composition, and degree of urbanity). While our results remain largely unchanged after controlling for these factors, variations between different groups of children in their mobility and exposure to deprivation might still exist and are important to explore further. In particular, the movement of poor families into and out of deprived neighborhoods requires further research to better understand selection into mobility as well as neighborhood deprivation. Housing tenure as well as the motivation for the move, which we were not able to include in our analyses, are important aspects to consider if we want to increase our understanding of patterns of upward mobility. Obtaining more insights into the housing tenure (change) of low-income families who move (i.e., between social or private housing or into home-ownership) as well as the reasons for low-income families to move will provide a better understanding of possible housing insecurity, unaffordability, and inaccessibility as impetus for moves (DeLuca & Jang–Trettien, Citation2020; Hochstenbach & Musterd, Citation2018). The current housing situation as well as opportunities and constraints in the housing market are important for understanding why some households might have more resources and opportunities to move. Nevertheless, this study points to the importance of studying the multidimensionality of childhood internal mobility trajectories and how these are related to neighborhood deprivation throughout childhood to gain a better understanding of mobility as well as neighborhood effects for inequalities.

Acknowledgments

The use of Dutch register data was made possible by Statistics Netherlands (CBS) through the CBS-NIDI collaboration. We thank CBS and particularly Marjolijn Das for the collaboration and the anonymous reviewers for the comments and suggestions that greatly improved our work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Joeke Kuyvenhoven

Joeke Kuyvenhoven is a PhD student at the Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute. Her PhD research focuses on differential patterns of childhood internal mobility and neighborhood change and their consequences for educational outcomes. Research interests include internal mobility, segregation, neighborhood effects and socio-spatial inequalities.

Karen Haandrikman

Karen Haandrikman is associate professor of human geography at the Department of Human Geography of Stockholm University, with a PhD from the University of Groningen, the Netherlands. Current research interests include segregation, integration, and neighborhood effects.

Rafael Costa

Rafael Costa has a background in economics and demography (PhD, University of Louvain). He has conducted research on different topics focusing on socio-spatial inequalities and using quantitative methods based on register data. He currently works as an expert at the Belgian Federal Planning Bureau and is affiliated with the University of Antwerp.

References

- Anderson, S., Leventhal, T., & Dupéré, V. (2014). Exposure to neighborhood affluence and poverty in childhood and adolescence and academic achievement and behavior. Applied Developmental Science, 18(3), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2014.924355

- Andersson, R. (2012). Understanding ethnic minorities’ settlement and geographical mobility patterns in Sweden using longitudinal data. In N. Finney & G. Catney (Eds.), Minority internal migration in Europe (pp. 263–291). Ashgate. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315595528

- Arundel, R., & Hochstenbach, C. (2020). Divided access and the spatial polarization of housing wealth. Urban Geography, 41(4), 497–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2019.1681722

- Bernard, A., & Vidal, S. (2020). Does moving in childhood and adolescence affect residential mobility in adulthood? An analysis of long‐term individual residential trajectories in 11 European countries. Population, Space and Place, 26(1), e2286. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2286

- Booi, H., Boterman, W. R., & Musterd, S. (2021). Staying in the city or moving to the suburbs? Unravelling the moving behaviour of young families in the four big cities in the Netherlands. Population, Space and Place, 27(3), e2398. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2398

- Brandén, M., Haandrikman, K., & Birkelund, G. E. (2022). Escaping one’s disadvantage? Neighbourhoods, socioeconomic origin and children’s adult life outcomes. European Sociological Review, 39(4), 601–614. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcac063

- Chetty, R., Hendren, N., & Katz, L. F. (2016). The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment. The American Economic Review, 106(4), 855–902. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20150572

- Clark, W. A. V. (2013). Life course events and residential change: Unpacking age effects on the probability of moving. Journal of Population Research, 30(4), 319–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-013-9116-y

- Clark, W. A. V., & Coulter, R. (2015). Who wants to move? The role of neighbourhood change. Environment and Planning A, 47(12), 2683–2709. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15615367

- Cotton, B. P. (2016). Residential mobility and social behaviors of adolescents: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 29(4), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12161

- Coulter, R., van Ham, M., & Findlay, A. M. (2016). Re-thinking residential mobility: Linking lives through time and space. Progress in Human Geography, 40(3), 352–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132515575417

- Coulton, C., Theodos, B., & Turner, M. A. (2012). Residential mobility and neighborhood change: Real neighborhoods under the microscope. Cityscape, 14(3), 55–89.

- Crowder, K., & South, S. J. (2011). Spatial and temporal dimensions of neighborhood effects on high school graduation. Social Science Research, 40(1), 87–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.04.013

- De Groot, C., Mulder, C. H., Das, M., & Manting, D. (2011). Life events and the gap between intention to move and actual mobility. Environment and Planning A, 43(1), 48–66. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4318

- DeLuca, S., & Jang–Trettien, C. (2020). “Not just a lateral move”: Residential decisions and the reproduction of urban inequality. City & Community, 19(3), 451–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12515

- DeLuca, S., Wood, H., & Rosenblatt, P. (2019). Why poor families move (and where they go): Reactive mobility and residential decisions. City & Community, 18(2), 556–593. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12386

- Findlay, A., McCollum, D., Coulter, R., & Gayle, V. (2015). New mobilities across the life course: A framework for analysing demographically linked drivers of migration. Population, Space and Place, 21(4), 390–402. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1956

- Flouri, E., Mavroveli, S., & Midouhas, E. (2013). Residential mobility, neighbourhood deprivation and children’s behaviour in the UK. Health & Place, 20, 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.12.002

- Galster, G. C. (2012). The mechanism(s) of neighbourhood effects: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. In M. van Ham, D. Manley, N. Bailey, L. Simpson, & D. Maclennan (Eds.), Neighbourhood effects research: New perspectives (pp. 23–56). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2309-2_2

- Gillespie, B. J. (2013). Adolescent behavior and achievement, social capital, and the timing of geographic mobility. Advances in Life Course Research, 18(3), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2013.07.001

- Gustafsson, B., Katz, K., & Österberg, T. (2017). Residential segregation from generation to generation: Intergenerational association in socio-spatial context among visible minorities and the majority population in metropolitan Sweden. Population, Space and Place, 23(4), e2028. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2028

- Haandrikman, K., Costa, R., Malmberg, B., Rogne, A. F., & Sleutjes, B. (2023). Socio-economic segregation in European cities. A comparative study of Brussels, Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Oslo and Stockholm. Urban Geography, 44(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2021.1959778

- Hochstenbach, C., & Musterd, S. (2018). Gentrification and the suburbanization of poverty: Changing urban geographies through boom and bust periods. Urban Geography, 39(1), 26–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1276718

- Ingram, M. C., & Harbers, I. (2020). Spatial tools for case selection: Using LISA statistics to design mixed-methods research. Political Science Research and Methods, 8(4), 747–763. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.3

- Jelleyman, T., & Spencer, N. (2008). Residential mobility in childhood and health outcomes: A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 62(7), 584–592. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2007.060103

- Jencks, C., & Mayer, S. E. (1990). The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood. In National Research Council (Ed.), Inner-city poverty in the United States (pp. 111–186). The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/1539

- Kleinepier, T., & van Ham, M. (2017). The temporal stability of children’s neighborhood experiences: A follow-up from birth to age 15. Demographic Research, 36, 1813–1826. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2017.36.59

- Kleinepier, T., & van Ham, M. (2018). The temporal dynamics of neighborhood disadvantage in childhood and subsequent problem behavior in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(8), 1611–1628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0878-6

- Kleinepier, T., van Ham, M., & Nieuwenhuis, J. (2018). Ethnic differences in timing and duration of exposure to neighborhood disadvantage during childhood. Advances in Life Course Research, 36, 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2018.04.003

- Kuyvenhoven, J., Das, M., & de Valk, H. A. G. (2022). Towards a typology of childhood internal mobility: Do children of migrants and non-migrants differ? Population, Space and Place, 28(2), e2515. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2515

- Lee, K. O., Smith, R., & Galster, G. (2017). Neighborhood trajectories of low-income U.S. Households: An application of sequence analysis. Journal of Urban Affairs, 39(3), 335–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2016.1251154

- Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 309–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309

- Leventhal, T., & Newman, S. (2010). Housing and child development. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(9), 1165–1174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.03.008

- Li, M., Li, W. Q., & Li, L. M. W. (2019). Sensitive periods of moving on mental health and academic performance among university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1289. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01289

- McKendrick, J. H. (2001). Coming of age: Rethinking the role of children in population studies. International Journal of Population Geography, 7(6), 461–472. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijpg.242

- Mollborn, S., Lawrence, E., & Root, E. D. (2018). Residential mobility across early childhood and children’s kindergarten readiness. Demography, 55(2), 485–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0652-0

- Morris, T., Manley, D., & Sabel, C. E. (2018). Residential mobility: Towards progress in mobility health research. Progress in Human Geography, 42(1), 112–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516649454

- Murphey, D., Bandy, T., & Moore, K. A. (2012). Frequent residential mobility and young children’s well-being. Child Trends Research Brief.

- Nieuwenhuis, J., & Hooimeijer, P. (2016). The association between neighbourhoods and educational achievement, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 31(2), 321–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-015-9460-7

- Owens, A., & Clampet-Lundquist, S. (2017). Housing mobility and the intergenerational durability of neighborhood poverty. Journal of Urban Affairs, 39(3), 400–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2016.1245083

- Price, C., Dalman, C., Zammit, S., & Kirkbride, J. B. (2018). Association of residential mobility over the life course with nonaffective psychosis in 1.4 million young people in Sweden. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(11), 1128–1136. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2233

- Robertson, O., Nathan, K., Howden Chapman, P., Baker, M. G., Atatoa Carr, P., & Pierse, N. (2021). Residential mobility for a national cohort of New Zealand-born children by area socioeconomic deprivation level and ethnic group. British Medical Journal, 11(1), e039706. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039706

- Sharkey, P. (2008). The intergenerational transmission of context. American Journal of Sociology, 113(4), 931–969. https://doi.org/10.1086/522804

- Sharkey, P., & Faber, J. W. (2014). Where, when, why, and for whom do residential contexts matter? Moving away from the dichotomous understanding of neighborhood effects. Annual Review of Sociology, 40(1), 559–579. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043350

- Simsek, M., Costa, R., & de Valk, H. A. G. (2021). Childhood residential mobility and health outcomes: A meta-analysis. Health & Place, 71, 102650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2021.102650

- Van Ham, M., Hedman, L., Manley, D., Coulter, R., & Osth, J. (2014). Intergenerational transmission of neighbourhood poverty: An analysis of neighbourhood histories of individuals. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 39(3), 402–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12040

- Vidal, S., & Baxter, J. (2018). Residential relocations and academic performance of Australian children: A longitudinal analysis. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 9(2), 133–156. https://doi.org/10.14301/llcs.v9i2.435

- Vogel, M., Porter, L. C., & McCuddy, T. (2017). Hypermobility, destination effects, and delinquency: Specifying the link between residential mobility and offending. Social Forces, 95(3), 1261–1284. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sow097

- Vogiazides, L., & Chihaya, G. K. (2020). Migrants’ long-term residential trajectories in Sweden: Persistent neighbourhood deprivation or spatial assimilation? Housing Studies, 35(5), 875–902. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1636937

- Vogiazides, L., & Mondani, H. (2023). Neighbourhood trajectories in Stockholm: Investigating the role of mobility and in situ change. Applied Geography, 150, 102823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2022.102823

- Wheaton, B., & Clarke, P. (2003). Space meets time: Integrating temporal and contextual influences on mental health in early adulthood. American Sociological Review, 68(5), 680–706. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240306800502

- Widdowson, A. O., & Siennick, S. E. (2021). The effects of residential mobility on criminal persistence and desistance during the transition to adulthood. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 58(2), 151–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427820948578

- Wodtke, G. T. (2013). Duration and timing of exposure to neighborhood poverty and the risk of adolescent parenthood. Demography, 50(5), 1765–1788. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0219-z

- Wodtke, G. T., Elwert, F., & Harding, D. J. (2016). Neighborhood effect heterogeneity by family income and developmental period. American Journal of Sociology, 121(4), 1168–1222. https://doi.org/10.1086/684137

- Wodtke, G. T., Harding, D. J., & Elwert, F. (2011). Neighborhood effects in temporal perspective: The impact of long-term exposure to concentrated disadvantage on high school graduation. American Sociological Review, 76(5), 713–736. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122411420816

Appendix

Table A1. Relative risk ratios (RRR) multinomial logistic regression of childhood mobility trajectories for children born in the metropolitan areas.

Table A2. Beta coefficients linear regression of duration of exposure to neighborhood deprivation for children born in the metropolitan areas and separate models by neighborhood of origin SES quintiles.