ABSTRACT

The transformation of lakefronts from spaces of privatization and contamination to vibrant public areas signifies a significant urban shift in Wuhan over the past 2 decades. This article explores a shift toward integrating bottom-up participatory approaches to sustainable environmental management with the top-down planning system amid this profound urban transition. By examining the unintended planning consequences and civic actions across Sha Lake and Dong Lake, this study uncovers a complex urban process marked by conflicts over waste management, property rights, and cultural identity issues at the water-land interface. In this process, new forms of civic participation emerged in Wuhan’s environmental management in the digital age, despite the lack of official participatory mechanisms. The study identifies parallels in the formalization of community engagements between Wuhan and other locales, notwithstanding China’s continued dominance of centralized governance, as middle-class activists increasingly play active roles in environmental management projects, utilizing skills, networks, and dedication.

Introduction

The lakefront in Wuhan’s central city is a vibrant and ever-changing scene. From the Cherry Blossom Festival in the early spring to the music carnivals in the summertime, several major public events are hosted in succession during the tourist season. On ordinary days, it draws people who come to stroll, jog, cycle along the greenway trail, fish, camp, birdwatch in the restored forewater wetland, or simply sit by the shore, taking in the tranquil moments amidst the passing crowds. What was once a notorious place marred by privatization, ecological degradation, and chaotic spatial governance in the early 2000s has become the most beloved urban public space, cherished by both locals and tourists.

However, this thrilling transformation was far from an easy journey. Legislative and urban planning efforts to curb illegal watershed encroachments unexpectedly pitted the municipal government against long-standing lakefront residents. Plans for new landfills, aimed at creating amusement parks, luxury housing, hotels, and other recreational facilities, triggered unprecedented outrage among those who wished to preserve the city’s dwindling urban lakes and their public access points. The city’s remaining public shorelines became a battleground that united various seemingly unrelated urban communities. A continuous collection of social conflicts has come to define the post-2000 history of Wuhan’s lakefront.

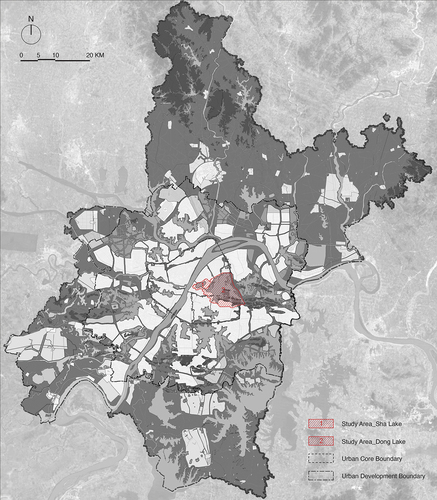

This study explores a trend toward incorporating grassroots participatory methods into sustainable environmental management alongside traditional top-down planning systems, within the context of significant urban transformation, viewed through the prism of spatial politics. Through an analysis of unplanned planning outcomes and community initiatives along the shores of Sha Lake and Dong Lake in central Wuhan (), this research aims to explore how novel modes of civic engagement have surfaced in Wuhan’s environmental governance, notwithstanding the absence of formal participatory structures.

Literature review

The politics of waterfront transition is not new to scholars in critical social science. Inspired by Hoyle et al. (Citation1988) and Malone’s (Citation1996) edited collections, earlier studies on this global waterfront phenomenon have adopted a political-economic framework, illuminating the processes through which changes in transportation technologies and economic structures since the 1970s have turned urban waterfronts into hubs for investment, speculation, and consumption (Desfor & Laidley, Citation2011; Desfor et al., Citation2011; Dovey & Sandercock, Citation2005; Porfyriou & Sepe, Citation2017; Richard, Citation2004). Following this template, investigations into mega-scale urban redevelopment schemes along China’s coastal line, such as Pudong Development Area and Lingang New Town in Shanghai, have provided rich insights into how waterfront revitalization has been integrated with city branding, regional economic restructuring, and state rescaling at different stages of China’s economic reform (Arkaraprasertkul, Citation2010; Hu, Citation2019; J. Li & Chiu, Citation2020; Marshall, Citation2001; Schubert, Citation2009; V. Wu, Citation1998; Xue et al., Citation2011). More recent case studies of the Suzhou Industrial Park (Xie & Lu, Citation2021), Wuhan Erqi Riverfront Business District (S. Lin et al., Citation2023), etc., have enriched the scope of this body of literature by shifting the focus to the inland and less-developed areas. However, usually focusing on the financial and institutional drivers, these studies paid relatively little attention to the social and cultural dimensions that have become increasingly essential to waterfront changes over the past few decades (Stevens, Citation2020).

With mounting concerns over space privatization, exclusion, and polarization within its highly neo-liberal political context (Bunce & Desfor, Citation2007; O’Callaghan & Linehan, Citation2007; Porfyriou & Sepe, Citation2017), waterfront, as a specific genre of urban public space, is increasingly integrated with the concept of “the right to the city” in the newer generation of waterfront studies. This literature can be broadly categorized into two sections.

The first category has its roots in professional planning practices and theories. Innovative redevelopment initiatives targeted at social and environmental sustainability have been widely discussed. Concepts such as housing affordability, public space accessibility, and the level of civic engagement have been implemented to examine the extent to which justice has been achieved during or after a variety of top-down affairs (Avni & Fischler, Citation2020; Miller, Citation2016; Taşan-Kok & Sungu-Eryilmaz, Citation2011; Wessells, Citation2014). A majority of existing studies on Wuhan’s lakefront, while more of a quantitative base than a qualitative one, fall partly into this category (W. Wang et al., Citation2016; J. Wu, Li, et al., Citation2019; J. Wu, Ling, et al., Citation2019; J. Wu, Luo, et al., Citation2019; J. Wu, Yang, et al., Citation2019; J. Wu et al., Citation2020). For instance, W. Wang et al. (Citation2016) examined the level of sustainability of Wuhan’s Big East Lake Coastal Area via the Collaborative Development Model, which integrates Landsat data analysis with a series of environmental, infrastructural, social, and economic indexes. Wu Jing and her colleagues at the School of Urban Design at Wuhan University have investigated the urban transition across Wuhan’s lakefronts from the perspectives of demographic distribution, transportation accessibility and movement patterns, thereby providing references to promote equity in the sustainable transition of Wuhan’s urban lakes (J. Wu, Li, et al., Citation2019; J. Wu, Ling, et al., Citation2019; J. Wu, Yang, et al., Citation2019). While growing attention has been paid to the impacts on the local communities, their approach has failed to uncover the actual urban processes that shape these places beyond planning documents, legislative provisions, maps and scientific statistics. Who is involved in the process? Are there any disputes, conflicts, and compromises over these changes in urban water? What kind of power relations are they based on or have been established during or after the transition? These questions still beg further inquiry.

The second category explores the alternative politics of the waterfront. For instance, O’Callaghan and Linehan (Citation2007) looked at Cork docklands’ redevelopment from the perspective of cultural politics, where civic society actions against a high-art-focused and pro-growth planning trajectory created an alternative to the neo-liberal politics of urban waterfront. Kinder (Citation2015) examined cultural movements initiated successively by houseboat hippies and queer communities across Amsterdam’s urban canals beginning in the 1960s, through which imaginations of urban water went beyond heritage and profit and were integrated with new concepts such as domestication and social identity. While a growing number of case studies have been investigated in the context of North American and European cities (Campo, Citation2013; Jones, Citation2016; Joseph & Thomas, Citation2021; Kinder, Citation2015; O’Callaghan & Linehan, Citation2007), limited attention has been paid to Chinese contexts, marked by a history of top-down planning and authoritarian control.

Only a handful of investigations have interrogated the politics surrounding Wuhan’s lakes (W. Lin, Citation2013; J. Xiao & Lu, Citation2022; J. Xiao & Qu, Citation2022). For instance, J. Xiao and Qu (Citation2022) have discussed the artistic resistance practices to reclaim public space at Dong Lake, highlighting the distinctive features of these practices that make emancipatory politics possible in the restrictive conditions imposed by the Chinese authorities. J. Xiao and Lu (Citation2022) have investigated the same event through a comparison study to the case of Federation Square in Melbourne, revealing the increasing role art and new media play in urban contention in China. However, similar to the approach adopted in recent sociological studies on contemporary Chinese urban public space, this body of literature either limits its scope to the observation of specific spatial occupation behaviors (C. Chen, Citation2010; Qian, Citation2018; Qian & Lu, Citation2019; E. Tian & Wise, Citation2022), or focuses on discussing a specific social event, highlighting the strategies, tactics, or other structural factors that contributed to its immediate success or failure (Cai, Citation2010; Wright, Citation2019). Although the authors have all investigated how urban public space is perceived by different parties, these discussions remain conceptual, leading to a general conclusion regarding “the right to the city.”

In contrast, building on the work of O’Callaghan and Linehan (Citation2007), Kinder (Citation2015), and others, this article challenges the conventional top-down and long-term waterfront redevelopment approach and examines the politics of lakefront through a collection of cultural and societal activities that transform the water-land divides over past 2 decades. Recent studies on participatory planning, a concept that originated in the early 1960s and was introduced to China in the late 1980s, have shown the unique challenges and opportunities associated with its implementation in China given the differences in political systems, institutional structures, and cultural traditions. Zhihua Zhou (Citation2018), for example, suggests that genuine collaborative partnerships among pertinent stakeholders are still improbable within the existing institutional framework for urban planning in China. Chang et al. (Citation2019) study on participatory initiatives in Suzhou reveals the ironic outcomes wherein profit-oriented endeavors by NGOs hindered advancements in public participation, contrasting with more successful outcomes observed in state-led, top-down approaches to participatory planning. Zhao et al. (Citation2023) highlight the significance of street-level bureaucracy in facilitating the implementation of planning initiatives and mitigating community conflicts in neighborhood renovation projects in Guangzhou.

Looking at the case of Wuhan, this study seeks to situate a wide range of civic society actions within the spatial planning and governance policy changes of Wuhan’s watery space. By investigating the processes and implications of these “unintended planning consequences,” this article aims to provide new insights into participatory approach to environmental management where the role of middle-class activists has often been overlooked in existing literature.

Methodologies and paper structure

The empirical foundation of this research heavily relies on materials gathered from two key governmental agencies in Wuhan: the Wuhan Municipal Water Affairs Bureau and the Wuhan Municipal Bureau of Natural Resources and Planning. These agencies are responsible for overseeing water management and urban design aspects, respectively, of water-related activities in the city. Extensive data was collected through an independent search of publicly available records from these municipal agencies and their affiliated design institutes, such as the Wuhan Planning and Design Institute. The collected materials encompassed a diverse range of governmental reports, including local water policy documents, urban planning documents, project plans, maps, and more, although only a select few are directly cited in this study.

To uncover the political dimensions of urban water practices in Wuhan, a systematic search was conducted within government-led Chinese local newspapers, namely, the Hubei Daily and the Changjiang Daily. This search aimed to extract valuable information related to political objectives and investment goals from reports, editorials, and interviews pertaining to the selected cases in this study. These official and editorial documents were complemented by an extensive collection of information obtained from mainstream social media platforms, including NetEase, Sina Weibo, authoritative WeChat public accounts, among others. This supplementary data included third-party assessments of the ecological and social impacts associated with various lakefront projects in the city, promotional materials provided by real estate developers, and expressions of aspirations within the local community. Together, these sources vividly portray the debates and contestations surrounding the watery spaces in Wuhan.

The rich array of documented materials was further enriched by 15 semi-structured interviews. These interviews primarily took place in person during two field trips to Wuhan, one from April to June in 2019, and the other from March to April in 2021 (). Interviewees were identified through archival review and peer recommendations, and consisted of urban planners, governmental officials, environmental experts closely associated with the design and planning of urban watery spaces, ordinary citizens directly or indirectly affected by the transformations resulting from these practices, as well as university students, environmental activists, and artists actively engaged in watershed protection activities in recent years. The depth of these interviews provided valuable insights into the values and beliefs that have permeated Wuhan’s water practices throughout the past 2 decades.

Table 1. Overview of interviewee participants.

While the research period overlaps with the lockdown in Wuhan and the zero-COVID policy in China (from late 2019 to early 2021), the empirical data presented in this paper may be limited in reading the spatial changes during this specific period due to the inaccessibility of the study area.

The rest of the article is organized into three distinct parts. The first part presents Wuhan’s lakefronts as the center of planning and management failures in the city’s environmental transition that commenced in the early 2000s. The second part is composed of three sections, delving into case studies at Sha Lake and Dong Lake in Wuhan’s central city. These case studies illuminate a spectrum of civic society actions taken in response to illicit reclamation and speculative development, actions that have had enduring structural implications for Wuhan’s lakefront development. The article concludes in the third part by highlighting the distinctive non-confrontational nature of Wuhan’s waterfront civic engagements, which opens the door to alternative politics and offers a unique perspective on navigating the challenges of authoritarian control in China.

Shoreline crisis in the environmental transition

From efforts to expand urban territory through levee construction and wetland filling, influenced by the “big is modern” mind-set in the early 20th century (Ye, Citation2010), to the conversion of lakes into farmlands and fishing ponds during the grain-first agricultural movement in the 1960s (Ho, Citation2003), and recent rapid urbanization and population growth that led to extensive residential development on reclaimed lakeside lands (Chao et al., Citation2021), more than a century of urban processes that praised the act of lake filling as means to expand developable territory, increase agricultural production, and boost economic growth have turned as “The City of a Hundred Lakes” from an integrated wetland ecosystem to places of environmental degradation, spatial disorder, and societal polarization in the 1990s.

With habitat loss and water contamination reaching a tipping point (Wuhan Municipal Water Affairs Bureau, Citation2005), the need to address the protection and management of urban lakes became evident. This led to the establishment of the Wuhan Municipal Water Affairs Bureau in September 2001. Subsequently, the following decade witnessed the formulation of a series of legislative and planning documents aimed at conserving Wuhan’s urban lakes. Notably, the Wuhan Lake Protection Regulations, recognized as China’s first municipal legislation focused on urban lake preservation, was passed in March 2002. These regulations were followed by the comprehensive Protection Plan for Lakes in Central City of Wuhan (2004–2020) completed in 2005, the Detailed Rules for the Implementation of Wuhan Lake Protection Regulations, implemented in October 2005, and the Measures for Lake Management in Wuhan, implemented in August 2010. Together, these documents constituted the foundational framework for the city’s urban lake preservation efforts ().

Table 2. Milestone of municipal actions on lakefront management.

Despite the regulations explicitly stating that land reclamation from the lakes should be strictly controlled, recent studies on lakefront land use changes in Wuhan have revealed an alarming trend of accelerating shoreline encroachment (Deng et al., Citation2017; J. Wu, Luo, et al., Citation2019; Zhu et al., Citation2015). For example, research conducted by J. Wu, Luo, et al. (Citation2019) demonstrated that between 2001 and 2009, the total surface water area in Wuhan decreased from 342.03 km2 to 288.84 km2, signifying a loss of surface water area more than 2.3 times that of the previous decade. The decline was most pronounced between 2001 and 2005 when the loss rate surged to 9.84%, the highest it had been since 1987.

The city’s post-1990s real estate boom, driven by factors such as population growth and the imperative to boost economic development (Chao et al., Citation2021). prominently featured the proliferation of Hujingfang Xiaoqu, gated residential areas that benefited from their proximity to the lakes. Although the Protection Plan for Lakes in Central City of Wuhan (2004–2020), announced in 2005, provided general guidelines for urban lake protection and delineated boundaries for surface water protection, the absence of specific planning provisions addressing land use and spatial controls in the lakefront buffer zones resulted in a haphazard landscape where residential structures were often constructed directly against the water’s edge without any designated setback for public access (). In the most extreme cases, like Nan Lake in Wuchang, the presence of the lake became virtually imperceptible even from a short distance, as the entire watershed had been enveloped by residential enclaves.

Furthermore, illegal reclamation emerged as a critical challenge in the planning and management of the city’s lakefronts. Data released by the Wuhan Land Resource and Planning Bureau in 2013 revealed that approximately 10,000 acres of surface water area were lost between 2002 and 2007, with only 53.3% of the reclaimed area having received official approval from the municipal government with verified documentation (Peng & Gao, Citation2013). Municipal officials and local scholars attributed the difficulties in protecting lakefronts to legislative gaps within the watershed management system. According to the “Detailed Rules for the Implementation of Wuhan Lake Protection Regulations,” promulgated in October 2005, the boundaries of urban lakes were primarily defined by the blue line, representing the high-water mark of a watershed. This demarcation was often visualized by sparsely placed boundary markers on-site, creating opportunities for opportunistic land encroachment in areas between these markers, where real-time monitoring was virtually impossible.

Identifying illegal encroachments was further complicated by the natural fluctuation of the shoreline over time. Developers deliberately deposited construction waste into the lakes, both as a cost-saving measure for waste management and to expand their waterfront properties, masking these encroachments to appear as natural accretions. Consequently, it became exceedingly challenging to distinguish between naturally occurring changes and human interventions once the land reclamation was completed. Furthermore, even when an encroachment was identified as illegal, the penalties imposed were often trivial compared to the potential profits; the Wuhan Lake Protection Regulations prescribed a maximum fine of just 50,000 yuan, regardless of the encroachment’s size. In stark contrast, a single acre of lakefront land could generate millions in profits for developers.

The unbridled development along the city’s shoreline eventually prompted decisive action from the municipal government. In September 2012, the Wuhan Municipal Lake Conservancy was established to oversee and coordinate various entities involved in the protection of urban lakes. Shortly thereafter, the “Three Lines and One Road Protection Plan for Lakes in the Central City of Wuhan” was completed in October 2012 through collaborative efforts between the Wuhan Municipal Water Affairs Bureau, Urban Planning Bureau, and Landscaping and Forestry Bureau. As the name suggests, this plan aimed to institute a comprehensive spatial control system for the protection of urban lakes by delineating three lines and one road within the lakefront buffer zone. These included the water surface control line (the blue line), greening control line (the green line), and waterfront construction control line (the gray line), as well as the establishment of a ring road encircling the lake’s perimeter. This plan was further reflected in the creation of 39 detailed land use control plans, each drawn at a 1:2000 scale, covering a combined research area of approximately 377.04 km2, with a blue line protection area of 137.8 km2, a green line control area spanning 101.7 km2, and a gray line control area encompassing 183 km2. The plan declared coastlines extending about 573 km and introduced a lakefront ring road system spanning 431.9 km.

The implementation of the Three Lines and One Road Protection Plan heralded the enforcement of a sophisticated legal system at the city’s lakefront. The presence of well-defined codes governing land use and spatial development empowered the administrative department to prosecute twenty cases of illegal lake reclamation, imposing fines of up to 500,000 yuan for each violation by June 2013, merely 8 months after the plan’s initiation (Peng & Gao, Citation2013). Subsequently, the municipal party committee articulated the vision of “None [of the lakes] can be erased, and not an inch can be reduced,” extending the scope of the plan to include 166 lakes within the city’s jurisdiction. “This [the blue line] is a high-voltage line that must not be touched. If reclamation from lakes were necessitated for municipal construction, the lost water surface area had to be compensated by creating a new artificial lake elsewhere in the city,” affirmed Wang Jun, a spokesperson for the Water Affairs Bureau, underscoring the determination of administrative authorities to safeguard the city’s remaining water bodies (He, Citation2016).

Simultaneously, the lakefront ring road system, designed to encompass 323.4 km of pedestrian pathways and 108.5 km of vehicular routes, was heralded as a prompt response to the waterfront crisis. According to planning experts involved in the drafting of this initiative, these ring roads replaced sporadic markers with prominent boundaries. They represented a tangible demarcation of watershed limits, preventing not only further encroachments on public waters but also establishing a logical footprint for future lakefront development (Huang et al., Citation2009). Political leaders recognized this as the inaugural step in the citywide implementation of the Three Lines and One Road plan. Former mayor Tang Liangzhi expressed, “We must complete the ring roads for the 39 lakes as soon as possible, even if they were made of mud,” emphasizing the urgent need to establish the lakefront ring road system to stabilize the city’s shoreline (H. Wu, Citation2012).

Nonetheless, the actual implementation of what was promoted as the most stringent lake protection legislation in history has, in practice, engendered heightened public discontent along the waterfront. This discontent became evident in an urban protest against the Sha Lake Ring Road Scheme, initiated by residents who alleged that the Three Lines and One Road initiative was a clandestine strategy of the municipal government to conceal past mismanagement and exploit land sales by creating new opportunities for shoreline expansion. The subsequent section delves into the origins, progression, and repercussions of this protest, unveiling the diverse and often conflicting social and political interests shaping Wuhan’s urban lakefront.

An urban protest: Shahu (沙湖) or Shahu (杀湖)?Footnote1

Sha Lake (Shahu), the largest urban lake in the city’s inner ring, has been the long-time victim of Wuhan’s radical economic development and urban expansion strategies implemented in different eras, losing half of its water surface as the city boldly moved forward over the past century. Yet, the intensive urban construction that converted water to land was not the only concern for its residents. Waste dumping regardless of its legitimacy, has emerged as a cost-effective and convenient method for managing construction waste in the nearby areas. For example, in 2008, a substantial amount of spoil generated during the construction of the Yangtze River Tunnel found its way to the northern bank of Sha Lake, where it remained for years until it eventually collapsed and submerged into the water, pushing the shoreline 50 meters closer to the lake’s center. Another incident took place in late 2009 when a dredging project aimed at improving the water quality of Sha Lake resulted in the excavation of silt, which was then left on the northwest corner of the lake, occupying 23,500 square meters of its surface water area (China Central Television News Center Review Department, Citation2012; Yang, Citation2012).

The failure in shoreline management at Sha Lake gained national attention when it was reported by The People’s Daily and China Central Television in 2012. In response, the Municipal Water Affairs Bureau made a public commitment to clean up the excess earthwork along the shoreline, restore the lost water surface, and enhance the oversight of lake-related projects (L. Chen, Citation2012; Y. Chen, Citation2012; J. Wang, Citation2013). However, this commitment remained largely unfulfilled for years.Footnote2 The issue resurfaced when the “Planning Proposal for the North Section of Sha Lake Ring Road” was introduced, as a major part of the lake’s ring road development and lakefront urban park design, incorporating a 1.8-kilometer-long and 20-meter-wide traffic lane on the northern bank of the lake ().

First unveiled during a public hearing hosted by government officials in January 2014, the scheme swiftly ignited fervent debates among planning experts, local community representatives, and environmental activists in attendance. The primary concerns centered around the middle section of the road, where the 20-meter width was widely perceived as illogical, given the presence of the nearest urban artery running parallel to it, less than 30 meters away to the north. Attendees at the meeting voiced apprehensions about various potential adverse effects, including noise and safety hazards stemming from heavy traffic, especially near the adjacent Hubei University Affiliated Elementary School, as well as the ecological impacts on the watershed itself (Xu, Citation2014).

Meanwhile, residents of Menghushuian, a substantial community comprised of highly educated university staff from Hubei University who had settled in the neighborhood since 2005, soon realized that the proposal had been developed based on an adjusted blue line. This adjustment effectively transformed roughly 20,000 square meters of wetland on the water side of the community into a solidified shoreline, including the silts area at their doorstep. This silts area should have been cleared years earlier as promised by the Municipal Water Affairs Bureau. Residents were left bewildered and raised questions during another meeting with government officials in May 2014: “How could a dredging project turn into a lake filling project?”; “Is it possible for the Municipal Water Affairs Bureau to modify the blue line without obtaining residents’ consent?”; “Could there be illicit practices involved in the design, application, and approval of the road-building project?” Representatives from the Menghushuian Homeowner Association were resolute in asserting that the dredging project and the municipal government’s ring road scheme had encroached on the lake surface in violation of the Wuhan Urban Lake Protection Ordinances established in 2005.

After considering the discussions that had taken place during these meetings, officials from the Municipal Urban Planning Bureau agreed to implement a minor alteration to the middle section of the road. The 20-meter four-way traffic lane was modified into a 6-meter two-way traffic lane, with greenery space on its far side. However, the officials refused to acknowledge any part of the plan that illicitly occupied the water surface, maintaining that the site of the ring road had been explicitly excluded from the blue line protection area after the publication of the Three Lines and One Road Lake Protection Plan in 2012. Meanwhile, engineering director of Wuhan Water Resources Development & Investment Co. Ltd., the affiliated institute of the municipal Water Affairs Bureau responsible for the design and execution of the Sha Lake Dredging Plan, issued a statement that completely contradicted what had been said in 2010, claiming that 30,000 m3 of silt had been deposited on shore intentionally to make the roadbed for the ring road based on the Three Lines and One Road Plan. By propagating the benefits of lakefront ring road construction—ranging from activating and stabilizing the shoreline to making room for drainage system upgradeFootnote3—the municipal government tried to portray this conflict as being caused by the interests of a small group who resisted public needs because they were not happy to see their private waterscape shared by the public.

This aroused greater frustration and heightened outrage. Collaborating with the local environmental non-governmental organization Green City of Rivers, residents of Menghushuian spearheaded a petition drive, garnering over 300 signatures from affected residents in the immediate vicinity, university students, and local enterprise employees, all expressing their opposition to the scheme. Simultaneously, they dispatched 29 letters to various government departments between 2014 and 2015, detailing their grievances regarding the illicit encroachment issue. They also requested access to the feasibility report and environmental impact assessment documents, which had never been made available in the case. The opponents also cited successful urban lake restoration initiatives in cities such as Hangzhou, where vehicle lanes had been abandoned in the design of the lakefront park. They proposed an alternative approach, suggesting that the mid-section be transformed into a 3-meter-wide plank path hovering above the water’s surface, aimed at minimizing its impact on the lake and the nearby communities. “We are not against the idea of opening up a public path, but against the expense of losing more surface water,” Wang Meng, the head of the Menghushuian Homeowner Association, told The Paper magazine, stating that the proposed scheme was literally written on the lake, where no setbacks had been left when the school and the residential area were built in the early 2000s (Zhou, Citation2015).

In March 2015, resident representatives, volunteers, and environmental activists converged in Chuhehanjie, hosting a public protest against the ring road scheme. Their rallying cry accused the government of using the lake protection plan, ostensibly implemented at Sha Lake, to conceal its past management failures while seizing opportunities for land sales at the detriment of the city’s urban lakes. Banners and posters prominently displayed historical photos and newspaper reports meticulously collected by the residents of Menghushuian, revealing the relentless shoreline encroachments at Sha Lake between 2008 and 2014.

The protesters strategically highlighted site K7, which was initially intended for public green space in the Comprehensive Plan of Wuhan 2009–2020 but had evolved into a high-end residential compound. This move framed the municipal lakefront development project as favoring real estate developers and the wealthy elite at the expense of the broader public interest. Even though local media maintained silence due to municipal pressure, these civic activities reached a broad audience through various channels, including independent electronic publications like The Paper, the national newspaper The Beijing News, the Tianya Forum bulletin board system, and social media platforms such as Sina Weibo. This widespread exposure underscored the municipal government’s failings in lakefront management, directly contributing to the disappearance of Wuhan’s urban lakes over the past 2 decades. Local environmental activist Yang Yaxi aptly summarized the situation in an interview, stating, “if the blue line was adjusted wherever the lake was reclaimed, the lakes in Wuhan would no longer exist.”

On September 30, 2015, after amassing nearly 200,000 yuan in contributions from various sources, 39 residents of Menghushuian took a significant step by filing a lawsuit against the Municipal Water Affairs Bureau. Their legal action aimed to compel the bureau to fulfill its commitments to clear the silted area and restore the lost water surface of Sha Lake. The intense media attention and widespread social discontent finally pressured the municipal government into responding to the protesters’ demands. The turning point came on March 29, 2016, when the Jiang’an District Court of Wuhan issued a ruling in favor of the plaintiffs during the initial proceedings. This ruling ordered the defendant, namely the Wuhan Municipal Water Affairs Bureau, to address the issue of lake filling within 60 days from the date the judgment took effect (Cao et al., Citation2016). While the Municipal Urban Planning Bureau did not accept the homeowner association’s proposal for a 3-meter-wide water boardwalk, citing technical requirements for roadside drainage culverts and fire trails, the outcome of this 6-year battle between the municipal government and the Sha Lake communities was the successful preservation of 15,000 square meters of water surface on the far side of the ring road ().

The emergence of non-state actors

The conflicts surrounding the development of the Sha Lake Ring Road brought to light the inherent flaws and challenges within land use planning, legal frameworks, and administrative approaches to shoreline preservation in Wuhan over the past decade. Attempts to adjust the blue line were hindered by the urban planning scheme implemented in the early 2000s, which left no room for shoreline vegetation or future development. The citywide implementation of lakefront ring roads, designed with a one-size-fits-all environmental protection approach, often overlooked the diverse and sometimes conflicting ecological, social, and political interests involved in shaping shoreline spaces. These interests encompassed concerns such as managing construction waste, fears of housing devaluation among residents, technical requirements for planning setbacks, and the passion of citizens for safeguarding the shoreline.

The Sha Lake case stood out as a turning point in environmental management in Wuhan, where the voices and interests of ordinary citizens, often marginalized by a bureaucratic and opaque system known for favoring specific political and capital interests, began to shape the lakefront landscape, albeit at a modest scale. This transformation was largely due to the relentless efforts of a well-educated, middle-class local community highly attuned to environmental issues, as well as other non-state actors, including university students, media professionals, and social activists who had actively engaged in watershed preservation activities in the city since the late 2000s.

A notable initiative was the local environmental campaign “Love to 100 Lakes,” launched on June 28, 2010, by the Changjiang Daily newspaper. Its mission was to create platforms for public participation in lake protection, foster dialogue between the government and citizens, and tackle lake-related problems. This campaign, strongly supported by various municipal administrative departments, including the Wuhan Municipal Water Affairs Bureau, Wuhan Municipal Environmental Protection Bureau, and Wuhan Municipal Youth League Committee, quickly gained momentum through mainstream media platforms and garnered over 1,000 participants within 2 weeks (Han, Citation2019). The campaign’s initial activities involved shoreline patrols, with participants conducting on-site investigations supported by environmental consultants. Data collected, including photography, GPS positioning, and water sample testing, were compiled into reports for presentation to relevant administrative bodies or the general public. Notably, investigations along Dong Lake led to the exposure of over 50 sewage outlets, prompting the municipal government to close unregistered outlets and reopen sewage treatment facilities, reducing daily sewage discharge to Dong Lake by 2,700 tons (Feng et al., Citation2010).

The Green City of Rivers, Wuhan’s first environmental non-governmental organization focused on urban lake protection, played a pivotal role in maintaining the campaign’s independence. It oversaw volunteer recruitment, knowledge dissemination, program planning, and execution, fostering close ties with influential local media outlets for effective communication between the municipality and citizens. The most compelling case was its cooperation with Political Inquiries, a live TV program of Wuhan TV, where citizens engaged with heads of municipal administrative departments on various issues, including social security, food safety, environmental issues, etc. Ke Zhiqiang, Ye Ming, Wen Changzhi and Cheng Qi, four core members of this environmental campaign, participated in the show on June 30, 2012, handing over the “Blue Book of Wuhan Lake Survey” to Vice Mayor Hu with all the data collected during 2 years of patrol activities, which helped uncover and rectify 10 cases of illicit lake filling (Jin & Gao, Citation2013). The following year, another confrontation on the show between volunteers of the campaign and the head of the Municipal Water Affairs Bureau over the missing water piles of four lakes in Jiangxia District helped preserve four lakes in the suburb from disappearing (Fu, Citation2013; Li & Wang, Citation2013).

Today, “Love to 100 Lakes” is hailed as one of Wuhan’s most successful environmental campaigns. In less than 6 years, it has rapidly expanded its social network, collaborating with local universities, conducting offline training programs, utilizing digital platforms, and embracing over 100 core members and more than 30,000 volunteers from diverse backgrounds, including students, educators, professionals, and employees of state-owned enterprises (Y. Chen, Citation2015). With unwavering municipal support, this initiative has enhanced public participation mechanisms over the past decade. Ordinary citizens can now engage through various means, such as independent lake surveys, participation in public hearings and symposiums on lakefront planning, initiating legal actions, and direct reporting via channels like the “Grassroot Lake Chief” and the “Mayor’s Hotline.” These avenues empower citizens to address issues related to government officials’ misconduct and unresponsiveness concerning environmental concerns (Han, Citation2018, Citation2019).

However, a significant drawback of these engagement methods was their placement within the lower echelons of the decision-making structure, where the public could only respond to finalized plans or near-irreversible situations (Han, Citation2020). This limitation became evident in the case of Sha Lake, where critical information, such as the blue line adjustment, was only revealed after construction had begun. Additionally, the campaign’s reliance on municipal support sometimes diverted attention away from seeking broader institutional changes, which could have better resolved conflicts in the case of Sha Lake. In the following section, we will explore another grassroots initiative called “Everyone’s Dong Lake,” which presented an alternative approach to addressing shoreline conflicts in Wuhan and unexpectedly contributed to social changes that transformed the Dong Lake shoreline into a vibrant civic space of freedom and rebellious spirit.

Everyone’s Dong Lake

In March 2010, a viral article originally published in the financial section of The Time Weekly made waves across multiple social media platforms in Wuhan. The article focused on a large-scale land transaction at the northern shoreline of Dong Lake, which encompasses a 2.11 km2 plot of land known as Lot P (2009) 113. The Overseas Chinese Town (OCT) Group had acquired this land for 4.3 billion yuan, with plans for a significant development project. The project included the construction of an amusement park (Happy Valley), a luxurious hotel complex, a shopping mall, and several gated areas for high-end apartments. The municipal government’s decision to authorize this project was met with controversy. Despite the potential economic benefits, it raised concerns for several reasons. Not only would it privatize 11 km of Dong Lake shoreline, but it was also likely to involve the reclamation of 0.3 km2 of water surface originally belonging to the Dong Lake Fishery, as revealed by reporter Yao (Citation2010).

Local environmental experts extensively discussed the potential ecological impacts of the project, emphasizing the role of the Dong Lake Fishery in preventing cyanobacteria blooms and maintaining the ecological balance of East Lake. Furthermore, ordinary citizens, who viewed free access to the city’s largest urban lake as a sacred and inviolable public good, expressed concerns about the privatization of the public shoreline and the ensuing gentrification.

While the OCT Group swiftly released a statement, vehemently denying any reclamation plans and asserting that they would not alter the East Lake shoreline nor encroach on Dong Lake’s water surface by “even an inch” (D. Tian, Citation2010), the deliberate void on Lot 4 within the planning documents cast doubt on the sincerity of these assurances. Additionally, environmental activists, through on-site investigations, uncovered covert lake-filling activities. Subsequently, local media outlets were inundated with positive coverage of the project, while online discussions opposing it were suppressed under the claim that they were “obstructing the city’s progress,” as declared by the municipal administrative department.

In the face of the impending changes at Dong Lake, a pervasive sense of pessimism swept through the city. This was vividly depicted in the opening scene of Li Luo’s documentary, where police officer Li Wen attempted to dissuade a student activist from responding to the social developments at Dong Lake, saying:

about this, your university students overthink. Our society is managed in a unified manner. First, open discussions about those matters do not interest ordinary folks. It has nothing to do with us. Applying whatever policy is about how different government departments coordinate. In this large context, you cannot solve these problems … The government is a machine of power and force. You cannot constrain the machine of power. It is normal in China. (L. Li, Citation2015)

It was in this context that “Everyone’s East Lake” emerged. Contrary to other environmental campaigns in the city, which often employed confrontational methods like social media reporting, large rallies, or public protests, “Everyone’s East Lake” took a more subtle approach. It began as an art project in June 2010, initiated by local architect Li Juchuan and artist Li Yu. Their primary aim was to create a platform for sharing common concerns and gathering the voices of ordinary people. Participants were encouraged to respond to the evolving social changes at the East Lake shoreline by creating on-site projects or artworks at the lake. To ensure that these expressions were free from external interference, Li Juchuan and Li Yu adopted a “do-it-yourself” or “de-leadership” mechanism, allowing participants to manage their projects autonomously within specific project guidelines.

Instead of highlighting the environmental aspects of the ongoing shoreline modification, Li Juchuan and Li Yu portrayed it as a political issue in which the power of ordinary citizens had been removed in the urban process. In the open call for participants, they wrote:

Does East Lake belong to each of our residents? Do we have the right to know in advance how it will change? We will be able to know the consequences of these changes in our lives. Can we have an opinion on every change in it? Does every change in it require our consent? The answer needs to be clarified. (J. Li & Li, Citation2012)

Yet, they believed there were still gaps in such a context where ordinary citizens could create their own space imaginatively:

… all we can know now is that there are still many lakeshores and waters that we can approach today. They are not the domain of only a few people and do not require a ticket to enter. Therefore, we would like to make a suggestion: “Let us get close to these shores and waters right now; maybe this is our last chance to enjoy East Lake freely.” (J. Li & Li, Citation2012)

The call for projects was posted on their official website, www.donghu2010.org, as well as on niche social media platforms popular within local creative communities, such as Douban Group and Tianya Tieba. Despite their initial intention to maintain a relatively low profile, the project garnered an impressive 56 submissions within just 2 months from its launch, running between June 25 and August 25, 2010. The participants hailed from diverse professional backgrounds, encompassing artists, graphic designers, architects, musicians, theater professionals, poets, scholars, freelancers, university students, and even the unemployed. Their ages ranged from 20 to 60, forming a multi-generational community. While the core of this community was composed of Wuhan residents, it also attracted social activists from major cities across China, including Beijing, Shanghai, Chongqing, Guangzhou, and Hangzhou (J. Li, Citation2012).

The participants exhibited a wide array of creative expressions in response to the evolving situation. Some staged “social dramas” to raise awareness about environmental issues and address concerns related to inequality (M. Wu, Citation2010). Others crafted installation art pieces to confront the problem of illicit lake filling (Y. Wu et al., Citation2010). Some explored innovative ways to utilize water as a public space (Kuang & Zhang, Citation2010; Liu, Citation2010); while others documented their personal experiences at the lakefront through various mediums, including texts, graphics, photos, and videos (T. Xiao, Citation2010). The impact of their 56 site-specific projects, scattered along the 127.91-km shoreline of Dong Lake, reverberated throughout the community and inspired numerous individuals to engage in the ongoing discussion. In 2012, two subsequent events, “Go to Your Happy Valley” held from April 29 to May 29 and “Everyone Comes to Do Public Art” from July 10 to August 31, received hundreds of submissions, further amplifying the project’s reach and influence.

Notably, the project had a profound impact on Wuhan’s younger generation, as local artist Zhang Ruoshui (Citation2020) highlights the revival of the city’s street culture, reminiscent of Wuhan’s past as China’s Punk Capital. A prominent case in point is the “TiaoDongWho” carnival, which originated from a BMX (Bicycle Motocross) lake-jumping event organized by local artist and BMX racer Liu Zhenyu as a protest against the OCT shoreline development plan, under the umbrella of “Everyone’s Dong Lake.” The inaugural event, held on July 18th, initially involved a small group of BMX enthusiasts who boldly executed freestyle jumps into the lake, boldly declaring their happiness didn’t depend on the proposed Happy Valley development.

The concept of carefree water-jumping quickly gained traction, attracting a diverse community of young white-collar workers, college students, and subcultural groups, including independent filmmakers, music composers, and extreme sports enthusiasts. They spontaneously convened at Dong Lake’s shore in late July each year, engaging in improvised water-jumping rituals to celebrate the summer’s end, even though these gatherings were often considered illegal by the municipal government. These impromptu lakeside celebrations effectively drew an expanding audience, who started seeing the lakefront as a public space for leisure and self-expression, eventually prompting efforts to regulate these events. Since 2015, in collaboration with the Municipal Sports Bureau and local enterprises like Indiefellas’ Bike Shop and No. 18 Brewery, the lake-jumping event has evolved into an annual waterfront carnival, seamlessly integrating various urban activities, including music festivals and creative markets.

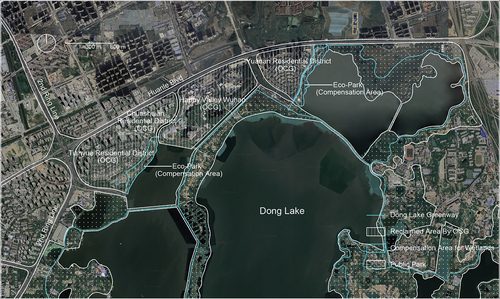

Regrettably, “Everyone’s Dong Lake” was unable to halt the progression of shoreline development. Faced with mounting public pressure, the OCT Group adjusted its promotional strategy, emphasizing the project’s ecological aspects. They envisioned a future as an “International Ecological Bay Area,” integrating tourism, culture, art, and residential living on the Dong Lake waterfront. A 160,000 m2 eco-art park was added to the master plan within the 100–150 m lakefront buffer zone, intended to be open to the public free of charge, partly in response to the art movement (). However, these new ecological community plans did not introduce substantial changes to the overall shoreline development. The fundamental components of the proposal remained gated high-end lake-view apartments and waterfront villas, catering primarily to the city’s wealthiest residents. Li Juchuan, the initiator of the art project, deemed their efforts a complete failure, asserting that ecology, environmental protection, and art, all ostensibly for the public good, were mere facades benefiting capital interests with easier access to land resources and housing price boosts (J. Li & Li, Citation2012). These derivative activities faced criticism from art critics, including Li himself, who saw them as losing the authentic spirit of rebellion, leaving only the pursuit of enjoyment and playfulness (Dong, Citation2021).

Nevertheless, the long-term effects of these civic activities began to surface. Since 2015, the municipal government initiated actions to incorporate citizens’ voices into their top-down planning strategies for the development of urban aquatic spaces. This approach was first tested with the planning of the Dong Lake Greenway, a pilot project for a citywide greenway system. In this endeavor, a web-based participatory planning support system was deployed to facilitate planning at various stages. While traditional participatory methods, such as comment columns and online questionnaire surveys, were employed in the initial planning phase for contextual information, a map-based application integrated with ArcGIS allowed participants to sketch greenway trails, identify infrastructure (such as parking lots, greenway entrances, rest areas), and present node plans based on their visions for the future Dong Lake Greenway. Between January 2015 and December 2016, a total of 265 planning suggestions, 508 questionnaires, and 1,686 planning proposals were gathered. This input, which intuitively represented the genuine needs and spatial visions of diverse stakeholders, served as a crucial foundation for shaping related facilities before final planning decisions were made. While the web-based public participatory mechanism faced criticism for limitations in inclusivity (primarily engaging male, young, local, well-educated, and middle-class “professional citizens” due to computer experience and domain knowledge requirements; L. Zhang et al., Citation2019), this exploration heralded the dawn of an era in which nature could be produced more democratically, equitably, and collectively controlled ().

Conclusions

In parallel with the burgeoning liberation movements that have shaped public spaces across the globe, Wuhan’s lakefront stands as an intriguing testament to the evolution of urban areas into platforms for expression, mobilization, and contestation. Spontaneous social activities such as street vending, vibrant square dancing, and inclusive gatherings like gay cruising have artfully carved spaces for self-actualization, serving as platforms for diverse countercultural groups that include working-class migrants, local senior residents, and sexual minorities (C. Chen, Citation2010; Qian, Citation2018; Qian & Lu, Citation2019; E. Tian & Wise, Citation2022). Urban protests, while frequently facing futility or repression, have become a recurrent social means for the expression of collective discontent within civic society (Cai, Citation2010; Wright, Citation2019). Here, these vibrant activities have not been marginalized or suppressed; instead, they have left an indelible mark on the transformation of Wuhan’s shoreline.

The prominent characteristic of Wuhan’s lakefront development is its non-confrontational nature, which arises from two key factors. On one hand, the political approach to Wuhan’s lakefront has evolved from a last-century anti-water development paradigm that adversely impacted its urban lakes to the recent adoption of green urbanism. This transformation involves reimagining lakefronts as parks, trails, wetlands, and more, with a growing integration of environmental concerns, including sustainability, livability, and resilience, emphasizing the concept of creating livable public spaces. Although capital-driven green gentrification remains a concern, this development direction generally aligns with the desires of the city’s residents. On the other hand, Wuhan, recognized as one of China’s three educational centers with 37 colleges and universities, has a significant population of young, educated individuals who are passionate and capable of taking a leading role in countercultural movements along the city’s shorelines. Despite the need, at times, to conceal the fundamentally confrontational nature of these activities under the guise of environmentalism, this knowledgeable, passionate, and creative local community has sought “rightful” methods of resistance through means such as filing lawsuits, institutional cooperation, and cultural movements. This non-oppositional approach has also made structural changes possible, even within a non-democratic system, creating an alternative politics of the waterfront that has had a far-reaching impact on the production of space in a system characterized by authoritative control.

Previous studies have extensively illuminated the distinctive features of participatory planning in China, primarily stemming from the enduring predominance of the centralized governmental system. However, this current study diverges from existing literature by identifying certain parallels in the formalization of community engagement practices between Wuhan and other locales. It underscores how, despite differences in governance structures, there are convergences in approaches to involving communities in decision-making processes. A notable trend has been the burgeoning involvement of middle-class activists in environmental management initiatives. These activists exhibit a potent combination of capabilities, skills, extensive social networks, heightened awareness, and unwavering dedication to fostering community participation. Like in other parts of the world, their increasing prominence signifies a significant shift in the dynamics of grassroots engagement, reshaping the landscape of environmental governance and participatory practices in urban China.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yiwen Yuan

Yiwen Yuan is an academic fellow at the School of Architecture, Design and Planning, University of Sydney. She specializes in research concerning water, environmental change, urban space and politics within a global context. Her doctoral thesis, entitled “The Politics of Changing Waterscapes in Wuhan,” addresses the fascinating case of Wuhan as a city whose transformation reveals complex relationships between multiple forces of environmental, social, technological, and political changes that continue to this day.

Duanfang Lu

Duanfang Lu is professor of Architecture and Urbanism in the School of Architecture, Design and Planning (ADP) at the University of Sydney. She holds a bachelor of Architecture from Tsinghua University, Beijing and PhD in Architecture from the University of California, Berkeley. She has published widely on modern architectural and planning history, and her work has explored various interdisciplinary intersections. She has been awarded prestigious research grants from Australian Research Council, the U.S. Social Science Research Council, and Getty Foundation, as well as the Best Article Prize from Planning Perspectives and the International Planning History Society.

Notes

1. Shahu, represented in Chinese pinyin, refers to Sha Lake. In a different context, this term can also carry the meaning of “kill the lake.”

2. In 2012, residents of Menghushuian were informed by The Municipal Water Affairs Bureau that the silts were only left on-site temporarily and would be well-attended after they had been dried out and ready for future treatment. However, further action has yet to be taken since then.

3. As per “The Pre-approval Announcement of the Planning Plan for the North Section of Sha Lake Ring Road (Sha Lake Bridge ~ Fuxing West Road)” issued by the Wuhan Municipal Land Resources and Planning Bureau on December 5, 2014, the plan included the addition of drainage culverts. These culverts were intended to redirect the sewage from the neighborhood to treatment plants, representing an improvement over the existing drainage system. The existing system allowed sewage discharge directly into Shu Lake without any prior treatment.

References

- Arkaraprasertkul, N. (2010). Power, politics, and the making of Shanghai. Journal of Planning History, 9(4), 232–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538513210382384

- Avni, N., & Fischler, R. (2020). Social and environmental justice in waterfront redevelopment: The Anacostia River, Washington, D.C. Urban Affairs Review, 56(6), 1779–1810. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087419835968

- Bunce, S., & Desfor, G. (2007). Introduction to “political ecologies of urban waterfront transformations”. Cities, 24(4), 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2007.02.001

- Cai, Y. (2010). Collective resistance in China: Why popular protests succeed or fail. Stanford University Press.

- Campo, D. (2013). The accidental playground: Brooklyn waterfront narratives of the undesigned and unplanned. Fordham University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780823251902

- Cao, X., Han, X., Sun, R., & Zhang, D. (2016, July 8). Wuhan aishui weicheng beihou de tianhu shi [the history of lake filling behind the waterlogged city Wuhan]. The Beijing News. http://www.bjnews.com.cn/inside/2016/07/08/409250.html

- Chang, Y., Lau, M., & Calogero, P. (2019). Participatory governance in China: Analysing state-society relations in participatory initiatives in Suzhou. International Development Planning Review, 41(3), 329–352. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2018.32

- Chao, W., Qingming, Z., De, Z., Huang, Z., & Chen, Y. (2021). Spatiotemporal evolution of lakes under rapid urbanization: A case study in Wuhan, China. Water, 13, 1171. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13091171

- Chen, C. (2010). Dancing in the streets of Beijing: Improvised uses within the urban system. In J. Hou (Ed.), Insurgent public space: Guerrilla urbanism and the remaking of contemporary cities (pp. 33–47). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203093009-8

- Chen, L. (2012). Wuhan zhengfu huiying shahu tianhu, cheng jiang bao humian shuiyu bujian yifen [Wuhan municipal government responded to the Sha Lake reclamation, stating that not an inch of its water surface would be lost]. Hubei Daily Media Group. Retrieved January 9, from http://district.ce.cn/newarea/roll/201204/12/t20120412_23235938.shtml

- Chen, Y. (2012, April 12). Wuhan municipality responded to the reclamation issue and made promise to shut down most of lake filling projects at Sha Lake. Wuhan Morning Post. http://tt65org.com/newsinfo/1988575.html?templateId=1133604 see also https://news.qq.com/a/20120412/000161.htm

- Chen, Y. (2015, January 1). China’s first grassroots warning map of urban lakes was born in Wuhan. Wuhan Morning Post. http://district.ce.cn/newarea/roll/201507/01/t20150701_5816205.shtml

- China Central Television News Center Review Department. (2012, May 6). Yao Shahu, not shahu! [Preserve Sha Lake, do not kill the lake!]. News 1+1.

- Deng, Y., Jiang, W. G., Tang, Z. H., Li, J. H., Lv, J. X., Chen, Z., & Jia, K. (2017). Spatio-temporal change of lake water extent in Wuhan urban agglomeration based on Landsat images from 1987 to 2015. Remote Sensing, 9(3), 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs9030270

- Desfor, G., & Laidley, J. (2011). Reshaping Toronto’s waterfront. University of Toronto Press.

- Desfor, G., Laidley, J., Stevens, Q., & Schubert, D. (2011). Transforming urban waterfronts: Fixity and flow (Vol. 3). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203841297

- Dong, H. (2021, November 5). Tiaojin Donghu zhihou [After jumping into the Dong Lake]. The Paper. https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_15224032

- Dovey, K., & Sandercock, L. (2005). Fluid city: Transforming Melbourne’s urban waterfront. University of New South Wales Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203857809

- Feng, J., Jin, T., & Ma, Z. (2010, December 22). Wuhan Donghu 8 ge paiwukou xianqi zhili [A Deadline was set for the treatment of eight sewage outfalls in Dong Lake, Wuhan]. Changjiang Daily. https://www.h2o-china.com/news/93015.html

- Fu, S. (2013, July 30). Wuhan Dianshi Wenzheng: Jinkou si hu yige dou buneng shao [2013 Wuhan political inquiries: None of the four lakes in jinkou could be lost]. Changjiang Daily. http://tt65org.com/newsinfo/1988559.html

- Han, Z. (2018). Wuhan shi gongzhong canyu hupo baohu moshi yanjiu: Yi “Aiwo Baihu” hupo baohu zhiyuanzhe xingdong weili [Study on the model of public participation in lakes protection in Wuhan, China: An example of “Love our 100 lakes” volunteer action]. Advances in Environmental Protection, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.12677/aep.2018.81001

- Han, Z. (2019). Wuhan hupo de shidai bianhua yu kongzhong canyu zhili de kongjian celue [Changes in Wuhan urban lake management and spatial strategies of its public participation]. China Ancient City, 2, 8. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1674-4144.2019.02.010

- Han, Z. (2020). Fei zhengfu zuzhi canyu chengshi hupo huanjing zhili de moshi yu jizhi yanjiu: Yi Wuhan Lvse Tanghu Shuishengtai Xiufu Xiangmu weili [Research on the model and mechanism innovation of NGO’s participation in the urban lake environmental governance: A case study of the Green Tang Lake ecological restoration project. Advances in Environmental Protection, 10(6), 887–896. https://doi.org/10.12677/AEP.2020.106106

- He, B. (2016, July 18). Xiashuidao shi yige chengshi de liangxin — Laizi dashui de kaowen [Sewer system as the conscience of a city: An interrogation from the flood]. China Newsweek, 764. http://zjt.hubei.gov.cn/bmdt/ztzl/hbcjda/dxgx/201910/t20191028_81384.shtml

- Ho, P. (2003). Mao’s war against nature? The environmental impact of the grain-first campaign in China. The China Journal (Canberra, ACT), 50(50), 37–59. https://doi.org/10.2307/3182245

- Hoyle, B. S., Pinder, D., & Husain, M. S. (1988). Revitalising the waterfront: International dimensions of dockland redevelopment. Belhaven Press.

- Hu, R. (2019). Global Shanghai remade: The rise of Pudong New Area. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429316180

- Huang, L., Wang, H., & Shang, Y. (2009). Jiyu hupo baohu de huanhulu guihua yu kongzhi: Yi Wuhan zhongxin chengqu hupo baohu sanxian weili [Lake preservation oriented lakeside ring road planning: A case study of three lines planning for lake preservation in Wuhan Central District]. Planners, 8(25), 3.

- Jin, T., & Gao, S. (2013, April 21). 2012 Wuhan Dianshi Wenzheng: Shilingdao jiannuo xiang “Caogen huzhang” jiaozuoye [2012 Wuhan Political Inquiries: Municipal leaders fulfill their promises to the “grassroot lake manager”]. Changjiang Daily. http://tt65org.com/newsinfo/1988555.html

- Jones, A. (2016). On South Bank: The production of public space. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315598833

- Joseph, D. K., & Thomas, W. M. (2021). Lakefront: Public trust and private rights in Chicago. Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7591/j.ctv153k607

- Kinder, K. (2015). The politics of urban water: Changing waterscapes in Amsterdam. University of Georgia Press.

- Kuang, Z., & Zhang, X. (2010). Zaoxing tiao Donghu [Stylish jumping at Dong Lake] [Performance art]. Wuhan. http://www.donghu2010.org/2010/member.php?id=71

- Li, J. (2012). Meigeren de Donghu yishu jihua [Everyone’s East Lake Project]. Architectural Worlds, 1(143), 3.

- Li, J., & Chiu, R. L. H. (2020). State rescaling and large-scale urban development projects in China: The case of Lingang New Town, Shanghai. Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland), 57(12), 2564–2581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019881367

- Li, J., & Li, Y. (2012). Call for participants of the third “Everyone’s Dong Lake” art project: Everyone comes to do “Public Art”. http://donghu2010.org/join.htm

- Li, L. (2015). Li Wen manyou Donghu [Li Wen at East Lake]. L. L. Films.

- Li, X., & Wang, X. (2013, July 4). Wuhan Dianshi Wenzheng: Baihu zhi shi zaoyu tongxin wu wen [2013 Wuhan political inquiries: The city of a hundred lakes confronted five interrogation]. Changjiang Daily. http://tt65org.com/newsinfo/1988558.html

- Lin, S., Liu, X., Wang, T., & Li, Z. (2023). Revisiting entrepreneurial governance in China’s urban redevelopment: A case from Wuhan. Urban Geography, 44(7), 1520–1540. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2022.2079272

- Lin, W. (2013). Situating performative neogeography: Tracing, mapping, and performing “Everyone’s East Lake”. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 45(1), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1068/a45161

- Liu, Z. (2010). BMX yiaohu youxi [BMX lake jumping game] [Performance art]. Wuhan. http://www.donghu2010.org/2010/member.php?id=40

- Malone, P. (1996). City, capital and water. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203350218

- Marshall, R. (2001). Remaking the image of the city: Bilbao and Shanghai. In R. Marshall (Ed.), Waterfronts in Post-Industrial Cities (pp. 61–81). Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203166895-10

- Miller, J. T. (2016). Is urban greening for everyone? Social inclusion and exclusion along the Gowanus Canal. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 19, 285–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2016.03.004

- O’Callaghan, C., & Linehan, D. (2007). Identity, politics and conflict in dockland development in Cork, Ireland: European capital of culture 2005. Cities, 24(4), 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2007.01.006

- Peng, P., & Gao, S. (2013). Wuhan gongbu 20 qi tianhu anli, weifa tianhuzhe zuihao fakuan 50 wan yuan [Wuhan municipal government announces 20 cases of illicit reclamation, and maximum fines raised to 500,000 yuan]. http://www.hubei.gov.cn/hbfb/szsm/201306/t20130609_1538847.shtml

- Porfyriou, H., & Sepe, M. (2017). Waterfronts revisited: European ports in a historic and global perspective. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315637815

- Qian, J. (2018). Re-visioning the public in post-reform urban China poetics and politics in Guangzhou (1st ed.). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5990-2

- Qian, J., & Lu, Y. (2019). On the trail of comparative urbanism: Square dance and public space in China. Transactions - Institute of British Geographers (1965), 44(4), 692–706. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12321

- Richard, M. (2004). Waterfronts in post-industrial cities. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203166895

- Schubert, D. (2009). Ever-changing waterfronts’: Urban development and transformation processes in ports and waterfront zones in Singapore, Hong Kong and Shanghai. In B. H. Chua & A. Graf (Eds.), Port cities in Asia and Europe. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203884515

- Stevens, Q. (2020). Activating urban waterfronts: Planning and design for inclusive, engaging and adaptable public spaces. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003034872

- Taşan-Kok, T., & Sungu-Eryilmaz, Y. (2011). Exploring innovative instruments for socially sustainable waterfront regeneration in Antwerp and Rotterdam. In G. Desfor, J. Laidley, Q. Stevens, & D. Schubert (Eds.), Transforming Urban Waterfronts: Fixity and Flow (pp. 273–289). Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/edit/104324/9780203841297/transforming-urban-waterfronts-gene-desfor-jennefer-laidley-dirk-schubert-quentin-stevens?refId=3f9caf91-ba5a-4095-b024-71818b5f1b65&context=ubx

- Tian, D. (2010, April 2). Wuhan Huaqiaocheng fouren jiang “tian Donghu jian jiudian” [OCT Denies That it Will “Fill the East Lake to Build a Hotel”]. People’s Daily. http://news.sohu.com/20100402/n271286278.shtml

- Tian, E., & Wise, N. (2022). Dancing in public squares: Toward a socially synchronous sense of place. Leisure Sciences, (ahead-of-print), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2022.2099490

- Wang, J. (2013, March 25). Shahu zhi shang: Weihu tianhu zaojiu gaojia hujinglou [The death of Sha Lake: Reclamation of lakes creates high-priced lake-view buildings]. Hubei Daily. http://hb.ifeng.com/news/fygc/detail_2013_04/25/743842_0.shtml

- Wang, W., Pilgrim, M., & Liu, J. (2016). The evolution of river-lake and urban compound systems: A case study in Wuhan, China. Sustainability, 8(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010015

- Wessells, A. T. (2014). Urban blue space and “the project of the century”: Doing justice on the Seattle waterfront and for local residents. Buildings (Basel), 4(4), 764–784. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings4040764

- Wright, T. (2019). Handbook of protest and resistance in China. Edward Elgar Pub.

- Wu, H. (2012). Wuhan tongguo “Sanxianyilu” baohu guihua [Wuhan passes Three Lines and One Road protection plan for 39 lakes]. Chutian Jin Bao. http://news.cnhubei.com/ctjb/ctjbsgk/ctjb03/201205/t2084055.shtml

- Wu, J., Li, J., & Ma, Y. (2019). A comparative study of spatial and temporal preferences for waterfronts in Wuhan based on gender differences in check-in behavior. International Journal of Geo-Information, 8(9), 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi8090413

- Wu, J., Ling, C., & Li, X. (2019). Study on the accessibility and recreational development potential of lakeside areas based on bike-sharing big data taking Wuhan city as an example. Sustainability, 12(1), 160. https://www.scilit.net/article/2569448ad9399a16997593c1bc0e7079

- Wu, J., Luo, J., & Tang, L. (2019). Coupling relationship between urban expansion and lake change: A case study of Wuhan. Water, 11(6), 1215. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11061215

- Wu, J., Yang, S., & Zhang, X. (2019). Evaluation of the fairness of urban lakes’ distribution based on spatialization of population data: A case study of Wuhan urban development zone. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 4994. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244994

- Wu, J., Yang, S., & Zhang, X. (2020). Interaction analysis of urban blue-green space and built-up area based on coupling model: A case study of Wuhan central city. Water, 12(8), 2185. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12082185

- Wu, M. (2010). Mianfei de XX [For free] [Performance art]. http://www.donghu2010.org/2010/member.php?id=33

- Wu, V. (1998). The Pudong development zone and China’s economic reforms. Planning Perspectives, 13(2), 133–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/026654398364509

- Wu, Y., Zi, J., & Mai, D. (2010). Sanshi mi jinian qiang [Thirty-meter memorial wall] [Installation]. http://www.donghu2010.org/2010/member.php?id=41

- Wuhan Municipal Water Affairs Bureau. (2005). Wuhan shi zhongxin chengqu hupo baohu guihua (2004–2020) [Wuhan lake protection plan in central urban area (2004–2020)]. http://www.fsou.com/html/text/lar/168413/16841306.html.

- Xiao, J., & Lu, I. F. (2022). Art as intervention: Protests on urban transformation in China and Australia. Journal of Urban Affairs, 44(4–5), 504–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2020.1854614

- Xiao, J., & Qu, S. (2022). “Everybody’s Donghu”: Artistic resistance and the reclaiming of public space in China. Space and Culture, 25(4), 743–757. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331220902980

- Xiao, T. (2010). Bluestar Donghu yingxiang jilu huodong [Bluestar Dong Lake visual recording project] [Collective Collage]. Wuhan. http://www.donghu2010.org/2010/member.php?id=28

- Xie, L., & Lu, X. (2021). Suzhou Industrial Park: Sustainability, innovation, and entrepreneurship. Springer Singapore Pte. Limited. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-6757-2

- Xu, J. (2014, January 15). The 20-meter-wide ring road: For protection or reclamation? Changjiang Times. http://tt65org.com/newsinfo/1988570.html

- Xue, C. Q. L., Zhai, H., & Mitchenere, B. (2011). Shaping Lujiazui: The formation and building of the CBD in Pudong, Shanghai. Journal of Urban Design, 16(2), 209–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2011.552705

- Yang, N. (2012, March 29). Hujing zajiu chengle Hujingfang? [How did the lake view become lake-view apartments?}. The People’s Daily. http://news.cntv.cn/society/20120329/116959.shtml

- Yao, H. (2010, March 29). Wuhan Huaqiaocheng Dong Lake kaifa diaocha: An investigation on Overseas Chinese Town Group’s development scheme of Dong Lake. The Time Weekly. http://www.sinoca.com/news/china/2010-03-25/68484.html

- Ye, Z. (2010). Big is modern: The making of Wuhan as a Mega-City in Early Twentieth century China, 1889–1957 [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Minnesota].

- Zhang, L., Geertman, S., Hooimeijer, P., & Lin, Y. (2019). The usefulness of a web-based participatory planning support system in Wuhan, China. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 74, 208–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2018.11.006

- Zhang, R. (2020). Cong “da Wuhan” dao “Donhu jihua” [From “The Great Wuhan” to “The Dong Lake Project”]. https://jifeng.wordpress.com/2020/04/01/碧波荡漾的东湖曾是大武汉的艺术公共空间-声/

- Zhao, N., Liu, Y., & Wang, J. (2023). “Co-production” as an alternative in post-political China? Conceptualizing the legitimate power over participation in neighborhood regeneration practices. Cities, 141, 104462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104462

- Zhihua, Z. (2018). Bridging theory and practice: Participatory planning in China. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 22(3), 334–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2017.1342558

- Zhou, Q. (2015, January 28). Wuhan beizhi haozi jinyi jie qingyu zhiming “tianhu wei kaifangshang xiulu”: Guanfang fouren [Being accused of using an 100-million dredging project to fill a lake and build roads for real estate developers: Wuhan municipal government officially denied this claim]. The Paper. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_1298581

- Zhu, J., Zhang, Q., & Tong, Z. (2015). Impact analysis of lakefront land use changes on lake area in Wuhan, China. Water, 7(9), 4869–4886. https://doi.org/10.3390/w7094869