ABSTRACT

It remains unknown if taking commonly used preventive actions is related to identity theft. In the current study, we use a dataset featuring over 220,000 respondents to the National Crime Victimization Survey Identity Theft Supplement (NCVS ITS). The survey was conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) first in 2012, then again in 2014, and once more in 2016. The findings reported here suggest that demographic variables (e.g., gender, income) and types of online activities (e.g., frequency of online shopping) are significantly related to identity theft victimization. An interesting additional finding is that among seven distinct types of preventive actions listed in the NCVS ITS survey (frequently checking credit reports, frequently changing passwords for financial accounts, employing purchase credit monitoring, shredding documents containing personal information, monitoring bank statements for suspect charges, using security software programs, and purchasing identity theft protection), shredding documents with personal information ALONE is significantly negatively related to identity theft victimization. All six other preventive actions are either positively related or unrelated to identity theft victimization. These findings generate practical implications and, most importantly, raise the question of whether some newly-fashioned preventive actions might provide better protection from identity theft protection.

Introduction

Identity theft often involves illegal possession and use of another person’s identity information to gain profit (Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a). It has become a common crime in the Western world. The Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) within the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) reported about 51,000 identity theft complaints that led to $278 million in financial losses in 2021 in the U.S. (Internet Crime Complaint Center, Citation2022) These official complaints are mostly received by IC3 via its online reporting portal. Many identity theft victims do not report their victimization, so this is a conservative estimate of loss. Harrell (Citation2019) estimates that about 10% of U.S. adults have been victims of identity theft each year over the course of the past decade, resulting in an estimated 26 million crime victims annually. Similarly, the European Commission (Citation2020) reported that about 33% of respondents experienced identity theft in 2019 based on a survey conducted across 30 European countries. Reyns (Citation2013) estimates that about 1.8 million British citizens become identity theft victims each year. To be noted, these figures are estimates based on a combination of self-reported and official data, and information collected among victims who know they are identity theft victims. One of the bedeviling features of identity theft is that victims are often unaware of their victimizations. It follows that the actual number of identity theft victims is likely even larger than the numbers derived from the Harrell and Reyns surveys (Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a).

Another noteworthy feature of identity theft is that individuals can become identity theft victims even if they do not engage in high-risk behaviors. People can experience identity theft by losing their wallets or purses, getting baited by pretext calls and skimming, or replying to innocent-appearing junk email messages (Allison, Schuck, and Lersch Citation2005; Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a). Likewise, data breaches can also lead to the leaking of personal information to nefarious parties. For example, the data breach of Capital One records led to the leaking of personal information for over 100 million customers (Chapple Citation2019). The data breach of the American Medical Collection Agency similarly affected millions of agency patients (Chapple Citation2019). In like manner, the data breach of the Equifax Credit Bureau impacted an estimated 147 million individuals (Cowley Citation2019).

Researchers and public officials alike started paying close attention to identity theft over a decade ago. The National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) team first included questions related to identity theft in their 2004 questionnaire (Baum Citation2006). Later, the NCVS started using the Identity Theft Supplement (ITS). As of 2021, the ITS has been implemented five times – in 2008, 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2018. Identity theft commonly involves both monetary and nonmonetary consequences (Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a). Although it is nearly impossible to completely eliminate the risk of being victimized by identity theft, many people take precautions to reduce their risk (Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a). Prior studies have focused primarily on the demographic characteristics and types of online behavior that predict identity theft victimization (e.g., Allison, Schuck, and Lersch Citation2005; Reyns Citation2013). However, it remains unknown if taking commonly employed preventive actions effectively reduces one’s exposure to identity theft victimization.

In an attempt to fill this research gap, we make use of survey data drawn from the National Crime Victimization Survey Identity Theft Supplement (NCVS ITS). This study explores two empirical research questions: 1) are identity theft preventive actions related to one’s likelihood of identity theft victimization? and 2) do identity theft preventive actions play a different role in explaining identity theft victimization for prior victims and for non-prior victims? The research limitations of this study are identified and discussed, and the public policy implications of our reported findings are discussed in some detail.

Literature review

Identity theft: definition, impact, and victims

Like many concepts in broad use in criminal justice, there is no universally accepted definition of identity theft. The public often views identity theft as a crime involving someone stealing a credit card and/or bank account information and gaining some form of financial benefit as a consequence. In academia, some scholars use the broader term ‘identity fraud’ (Pontell Citation2002). However, one element of fraud in statutory law and common law alike requires some form of direct communication between victims and offenders (Golladay and Holtfreter Citation2017); identity theft does not always involve such interpersonal exchange (Reyns Citation2013). For instance, ‘old-fashion’ identity theft often involved the theft of wallets and dumpster diving for personal information (Allison, Schuck, and Lersch Citation2005). Victims do not know who steals their wallets or opens new accounts with their identity until a suspect is identified. ‘Modern’ identity theft often entails spam and junk emails with fake hyperlinks providing a means for victims and offenders to interact. In the case of major and minor data breaches, victims definitely have no idea of who has stolen their financial identities.

Despite the presence of some diversity in how identify theft is being conceptualized in the criminal justice arena, a generally accepted definition among scholars holds that identity theft entails the ‘the unlawful use of another person’s personal identifying information’ (Piquero, Cohen, and Piquero Citation2011, p. 438). Identity thieves may either directly use another’s identifying information to open new accounts and/or make purchases, or they can sell the personal information to other thieves. While a useful conceptualization, this commonly used definition does not entirely overcome the problem of documenting the occurrence of identity theft. For example, victimization surveys such as the NCVS ITS typically treat unauthorized use of existing credit cards as one measure of identity theft (Copes et al. Citation2010; Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a). In contrast, research that relies upon police records and offender interviews often does not count credit card misuse as a form of identity theft (Copes and Vieraitis Citation2009a; Rebovich Citation2009). For example, Copes et al.’s (2010) study suggests that ‘including existing credit card fraud may obscure the fact that those who are female, black, young, and low income are disproportionately victimized by existing bank account fraud’ (p. 1045). Given these considerations, the best research approach would seem to be to separately analyze each type of identity theft (e.g., misuse of existing bank accounts, misuse of existing credit cards, and opening of new accounts) instead of analyzing identity theft as a whole.

Despite the unsettled definition of identity theft as a crime, its social cost is undoubtedly massive, including monetary loss, emotional distress, and physical distress. An early study estimated that the direct costs of identity theft were $15.6 million in 2006 (Piquero, Cohen, and Piquero Citation2011). Other studies analyzed NCVS ITS surveys and estimated that the monetary losses were $24.7 billion in 2012, $15.4 billion in 2014, and $17.5 billion in 2016 in the U.S. (Harrell Citation2019; Harrell and Langton Citation2013; Harrell Citation2015). A recent study reported that identity theft victims experienced losses of ~$850 on the average (Harrell Citation2019). If they were victims of the opening of new accounts, the average losses were $3,460 (Harrell Citation2019).

Emotional and physical distresses are not uncommon among identity theft victims. Golladay and Holtfreter (Citation2017) reported that identity theft victims often experienced severe headaches, had trouble sleeping, experienced rage and anger, and in some cases suffered from prolonged depression. Randa and Reyns (2019) reported that victims of identity theft were more likely to experience distresses as the length of time their cases dragged out before they were ultimately cleared up. The time spent on resolving identity theft cases could range from mere hours to many days, and in some cases the problem persists for years (Copes et al. Citation2010; Piquero, Cohen, and Piquero Citation2011).

The demographic traits of identity theft victims are, in general, different from those of violent and property crime victims (Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a). For example, compared to victims of violent and property crimes, victims of identity theft are usually older (Golladay Citation2017). Individuals between 25- and 64-year-old are likely to be identity theft victims (Anderson Citation2006; Harrell Citation2019). Regarding gender and race, findings are not consistent. Some studies have found that males were more likely to be victims of identity theft than females (e.g., Allison, Schuck, and Lersch Citation2005; Anderson Citation2006), while others have reached the opposite conclusion (e.g., Reyns Citation2013). Some studies found that minorities were disproportionately likely to become identity theft victims (e.g., Anderson Citation2006), while some scholars have argued that Whites were more likely to be the victims of these crimes than minority people (e.g., Allison, Schuck, and Lersch Citation2005; Harrell Citation2019). Unlike street crimes, individuals with higher incomes are more likely to be identity theft victims than persons of modest means (Anderson Citation2006; Harrell Citation2019; Reyns Citation2013). Studies have found that persons with annual incomes of $75,000 or higher were significantly more likely to become identity theft victims when compared to persons with incomes of $25,000 or lower (Anderson Citation2006; Harrell Citation2019). Marital status and the number of children in the household may also impact identity theft victimization. Married individuals and households with three or more children are more likely to be victims of identity theft than non-married individuals and childless households (Anderson Citation2006; Reyns Citation2013).

In the increasingly virtual and online age in which we live, individuals’ online behavior – particularly online purchasing of goods and services – has been shown to increase the likelihood of identity theft victimization. For example, Holtfreter et al. (Citation2015) found that individuals with low self-control tended to engage in more risky online purchasing (e.g., purchase things online with unknown people). Another study reported evidence that people who used email and online banking frequently were more likely to experience identity theft than people who less frequently use email and engage in online banking (Reyns Citation2013). Also, people who engaged in downloading files were more likely to be victims of identity theft than those who did not (Reyns Citation2013). A recent study suggested that whether individuals purchased things online and how often they made online purchases would impact likelihood of identity theft victimization (Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a). How individuals perceive their risks of being identity theft victims perhaps influences their actual identity theft victimization. For example, Reisig, Pratt, and Holtfreter (Citation2009) found that people who articulated a higher perceived risk of cybercrime victimization tended to spend less time online and make fewer online purchases. In contrast, Reyns (Citation2013) reported that people with higher perceived risk were three times more likely to become identity theft victims, a finding likely attributable to the fact that these people might have been victimized previously. Some studies found that prior identity theft victimization had a significant relation with later identity theft victimization (Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a).

Preventing identity theft: commonly advised and often used preventive actions

Identity theft is considered an easy and relatively low-risk criminal activity for many offenders (Copes and Vieraitis Citation2009a). The clearance rate for identity theft is relatively low, a fact which highlights the importance of prevention (Allison, Schuck, and Lersch Citation2005; Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a). In response to various identity theft methods, studies have suggested the use of several preventive actions. Broadly, the preventive methods can be divided into two basic types; proactive preventive (prevention) actions and reactive actions (detection) (also see Gibert and Archer Citation2012). The following two sections review first the proactive and then the reactive actions in some detail.

Proactive actions

The primary purpose of proactive actions is the prevention of identity theft before it occurs. A traditional means used by identity theft offenders include theft of wallets, dumpster diving, and the stealing letters and packages sent in the mail (Allison, Schuck, and Lersch Citation2005; see also Copes and Vieraitis Citation2009b). Accordingly, preventive action against the traditional means of identity theft entails the shredding of documents containing personal information (Dean, Buck, and Dean Citation2014). Based on previous findings, the preventive effect of this action is promising (e.g., Burnes, DeLiema, and Langton Citation2020; Lai, Li, and Hsieh Citation2012). Using a sample collected from a large U.S. university, Lai, Li, and Hsieh (Citation2012) found from their SEM analysis that conventional coping (e.g., the shredding of bank statements) was effective in reducing identity theft occurrences. Burnes, DeLiema, and Langton (Citation2020) analyzed NCVS ITS data and found the consistent result that the shredding of personal documents was effective in reducing identity theft victimization.

Frequent change of passwords is one of the potentially successful strategies to prevent online identity theft (Burnes, DeLiema, and Langton Citation2020: Dean et al., Citation2014). Some studies have found that frequent password changes of financial accounts reduced identity theft victimization (e.g., Burnes, DeLiema, and Langton Citation2020; Lai, Li, and Hsieh Citation2012). While Williams (Citation2016) found that changing passwords was actually positively associated with victimization, he concluded that previous victimization experiences raised caution on identity theft, leading to changing passwords often. However, Reyns and Henson (Citation2016) reached a different conclusion – namely, that regular password change has no preventive effect on online identity theft victimization.

Online security software use has been suggested as another effective proactive method to prevent identity theft (Holt and Turner Citation2012). However, some studies have called into question the effectiveness of security software for preventing general online crime victimization. While some studies have reported evidence that security software significantly reduced cybercrime victimization (e.g., Choi Citation2008; Holt and Turner Citation2012), other studies have reported that security software did not notably reduce cybercrime victimization (Holt and Bossler Citation2008; Leukfeldt Citation2014; Marcum Citation2008). The same pattern is observed in the identity theft research. Holt and Turner (Citation2012) found that using security software significantly reduced online identity theft victimization of individuals at high risk of identity theft, while other studies produced a different result. Williams’s (Citation2016)’s multi-model analysis also revealed the consistent result that using security software was negatively associated with online identity theft victimization. However, using cybercrime victimization survey data collected in the Netherlands, Leukfeldt (Citation2014) found that using security software did not substantially reduce phishing victimization. From their analysis of the Canadian General Social Survey (GSS), Reyns and Henson (Citation2016) also reported the same result – namely, that the use of security software did not appreciatively affect online identity theft victimization.

Reactive actions

Early detection is a key to preventing suffering from the difficult consequences associated with identity theft (Albrecht, Albrecht, and Tzafrir Citation2011). Reactive actions mainly focus on the early detection of identity theft after it first occurs. Those actions include frequent checking of credit reports/bank statements for suspicious transactions and purchasing external services to prevent identity theft (e.g., identity protection insurance and credit monitoring services). In terms of the frequent checking behaviors, studies generally reported a consistent result that checking credit reports/bank statements frequently was an effective form of behavior to prevent identity theft revictimization (Lai, Li, and Hsieh Citation2012). However, it must be noted that not all identity theft victims will report crimes to the police. For example, some studies have reported that compared to hacking, identity theft and consumer fraud victims were more likely to report their victimization to the police (van de Weijer, Leukfeldt, and Bernasco Citation2019). Surprisingly, repeated identity theft victims, high-income victims, and highly-educated victims were less likely to report new identity theft victimization to the police than their counterparts (van de Weijer, Leukfeldt, and Bernasco Citation2019).

While these frequent checking behaviors are generally preventive against identity theft, studies examining the effectiveness of external protection services such as commercial identity theft protection insurance/credit monitoring revealed that using such services had either no association or even a positive association with identity theft victimization (Burnes, DeLiema, and Langton Citation2020; Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a). This correlation with victimization may be a direct consequence of prior victimization experiences leading to the purchasing of external services to prevent future victimization (see Burnes, DeLiema, and Langton Citation2020; Reyns and Henson Citation2016; Williams Citation2016). Additionally, Liu (Citation2019) provided another insightful explanation that identity theft insurance reduces individuals’ perception of identity theft risk and the likelihood of adverse outcomes stemming from high-risk activities, consequently leading to an increased likelihood of identity theft victimization.

The current study

So far, prior studies have focused almost exclusively on citizen demographic characteristics and types of online behavior engaged in for predicting identity theft victimization. However, it remains unknown if taking proactive and/or reactive preventive actions is effective in reducing one’s exposure to identity theft. Unlike traditional crimes, identity theft victims can easily be repeatedly victimized if they do not take self-protective action in time. For example, if a person’s credit card information is stolen, before he or she notifies the bank to cancel the card the thief can continue using this credit card. Additionally, under some circumstances, even if a victim takes action immediately, he or she can do very little to prevent his or her personal identity information from spreading into the hands of malicious parties. For instance, if a person’s social security number (SSN) is stolen by a thief, the wrongdoer can use it to open new accounts and/or sell the private information to another thief (see Data Breach, Chapple Citation2019). Moreover, the person victimized may have to deal with this issue for a long time because, unlike credit and debit cards, social security numbers cannot be easily changed.

Against this backdrop, this study explores two empirical research questions: 1) are identity theft preventive actions related to one’s likelihood of identity theft victimization? and 2) do identity theft preventive actions play a different role in explaining identity theft victimization for prior victims and for non-prior victims? Analytical methods employed are described in the following section.

Methods

Data

The current study uses survey data on over 220,000 respondents drawn from the National Crime Victimization Survey Identity Theft Supplement (NCVS ITS). The NCVS ITS has been used by several scholars to document factors related to identity theft victimization (e.g., Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a) and to assess its adverse consequences (e.g., Randa and Reyns Citation2020). The survey was first conducted in 2008 by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), and the three waves of the survey used here were conducted in 2012, again in 2014, and once more in 2016. The National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) uses a stratified multistage cluster sampling strategy to interview each household member who is aged 12 years and older either in person or via phone in the United States (Hu et al. Citation2020). The NCVS ITS is a supplement of the NCVS and it interviews household members who are 16 years old or older regarding specific questions related to identity theft victimization after they answer the general questions asked by the NCVS (Bureau of Justice Statistics Citation2016). The overall response rates are 68.2% in 2012, 66.1% in 2014, and 60.0% in 2016. We combined three waves of the NCVS ITS to maximize the number of cases for analysis. After the three datasets were merged, the sample contained a total of 224,124 observations.

Dependent variables

Although the definition of identity theft is not entirely settled (Copes et al. Citation2010; Golladay and Holtfreter Citation2017; Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a), we make use of the measures the BJS specifies in its identity theft survey. The first three dependent variables measured identity theft victimization related to respondents’ existing accounts. The variable ‘misuse checking/saving accounts’ measured if a respondent’s checking/saving accounts were misused by others in the past 12 months (0 = no and 1 = yes). The variable ‘misuse credit cards’ measured if a respondent’s credit cards or credit card accounts were misused by others in the past 12 months (0 = no and 1 = yes). And the variable ‘misuse other types’ measured if a respondent’s other accounts, including but not limited to cable accounts, iTunes accounts, and PayPal accounts were misused by others in the past 12 months (0 = no and 1 = yes).

The fourth dependent variable, ‘open new accounts,’ asked a respondent if his or her identity information was illegally obtained and used to open new accounts by others. This malicious activity included such things as bank accounts, credit card accounts, loan accounts, and online accounts in the past 12 months (0 = no and 1 = yes). The fifth and final dependent variable ‘information fraudulent’ measured if a respondent’s personal information was misused for other types of fraudulent activities such as renting a house or receiving medical care (0 = no and 1 = yes).

Independent variables

This study explores whether commonly used preventive actions were effective in reducing exposure to identity theft. It employs seven preventive actions specified by the creators of the NCVS ITS; these are all expressed as dichotomous variables. We divided this set of variables into two groups representing proactive and reactive approaches toward risk reduction. The proactive approaches involved actions taken before victimization. The survey measured one traditional proactive approach, asking if a respondent frequently engaged in the shredding of documents such as credit card and bank statements containing personal information (0 = no and 1 = yes). It also used three variables taping into modern proactive approaches born of the digital age. The first one pertains to a respondent frequently changing his or her passwords for financial accounts (0 = no and 1 = yes). The second one involves a respondent using security software programs to prevent misuse of a lost credit card (0 = no and 1 = yes). And the third variable asked a respondent whether he or she purchased identity theft protection from a commercial company (0 = no and 1 = yes).

The reactive approaches entail taking some actions against identity theft, but these actions only detect post hoc identity theft rather than preventing it from happening. The first such reactive variable asked a respondent if he or she frequently checked credit reports (0 = no and 1 = yes), and the second variable asked if he or she frequently checked bank statements (0 = no and 1 = yes). The respondent might notice a suspicious item in credit card reports and/or bank statements, inferring an identity theft might have happened. The victim’s only recourse is to cover the loss, contact the credit card vendor and/or bank in the hopes of preventing future victimization. The current study also used one variable to measure a modern reactive approach entailing ongoing computer-assisted monitoring. It asked a respondent if he or she had purchased credit monitoring services and/or identity theft insurance for recovering losses (0 = no and 1 = yes). Once again, these services only monitor accounts for suspicious (abnormal) purchases and withdrawals rather than preventing identity theft victimization.

Control variables

To explore whether preventive actions do impact likelihood of identity theft victimization, the current study used several conventional control variables, categorized into three groups. The first group of control variables measured a respondent’s demographic background characteristics. Many prior studies have shown that demographic variables can be significant factors associated with identity theft victimization (e.g., Allison, Schuck, and Lersch Citation2005; Golladay and Holtfreter Citation2017; Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a). The variable ‘gender’ measured a respondent’s sex (0 = female and 1 = male). The variable ‘age’ was measured as a continuous variable (Min. = 16 and Max. = 90). The variable ‘race’ contained four groups (1 = White, 2 = African American, 3 = Asian, and 4 = other races) and it was recoded into four dichotomous variables when conducting logistic regressions. The variable ‘ethnicity’ asked a respondent if he or she was a Hispanic (0 = no and 1 = yes). The variable ‘education’ documented a respondent’s educational level (1 = less than high school, 2 = high school and associate degree, 3 = Bachelor degree, and 4 = Master degree and higher). The variable ‘income’ measured a respondent’s estimated annual income (1 = less than $10,000; 2 = $10,000-$19,999, 3 = $20,000-$29,999, 4 = $30,000-$39,999, 5 = $40,000-$49,999, 6 = $50,000-$74,999, and 7 = more than $75,000). The variable ‘married’ captured the respondent’s marital status; married or not (0 = no and 1 = yes), and the variable ‘job’ indicates a respondent’s employment status, that is having a job or not (0 = no and 1 = yes).

The second group of control variables measured a respondent’s living arrangements. Prior studies have discussed a variety of approaches to illegally obtained personal information (Reyns Citation2013). Some traditional approaches, such as dumpster diving, pertain to thieves entering a community and going through community dumpsters searching for identity-bearing mail discarded by community members (Allison, Schuck, and Lersch Citation2005). This mail often contains personal information that has not been shredded, information typically linking names, addresses, account numbers, and phone numbers. Additionally, people who move frequently often have mail going to their old addresses; such mail is valuable to motivated identity thieves. Three variables were measured in this group of control measures. The variable ‘moving’ measured a respondent’s moving frequency in the past five years (0 = not move at all, 1 = move one time, 2 = move twice, 3 = move three times, 4 = move four times, 5 = move five times, and 6 = move six and more than six times). The variable ‘gated’ measured if a respondent’s current community was a gated/or walled community (0 = no and 1 = yes). The variable ‘access’ measured if a respondent’s residential dwelling had access control to residents’ mailboxes (0 = no and 1 = yes).

The third group of control variables measured a respondent’s online behavior, as many studies have shown that online behavior, such as online shopping, downloading, and online banking, can significantly increase the likelihood of being victimized by identity theft (e.g., Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a; Reyns Citation2013). This group of control measures features three variables. The variable ‘online shopping’ measured a respondent’s online shopping frequency in the past 12 months (0 = never, 1 = 1–50 times, 2 = 51–100 times, 3 = 101–150 times, 4 = 151–200 times, and 5 = 201 and more times). Individuals often choose credit cards and/or debit cards to complete online purchases. The variable ‘payment credit’ asked a respondent if he or she used credit cards to do online shopping (0 = no and 1 = yes), and the variable ‘payment debit’ measured if he or she used debit cards (0 = no and 1 = yes).

Finally, since we combined three waves of the NCVS ITS, a control variable ‘year’ was created (1 = 2012, 2 = 2014, and 3 = 2016). This control variable was later recoded into three dichotomous variables when conducting logistic regressions. About 43% of the cases in the combined sample were collected in 2016 (N = 95,959), followed by 2014 (N = 64,136) and 2012 (N = 64,029). The year 2012 was treated as a reference variable.

Analytical strategies

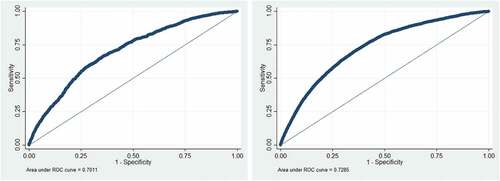

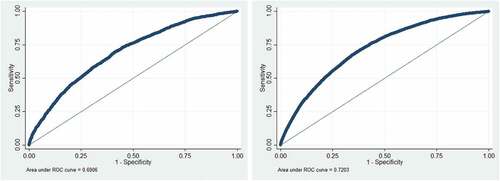

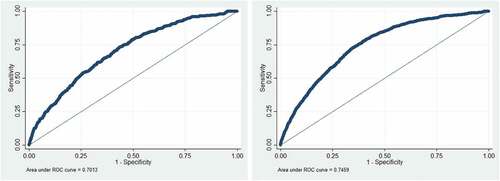

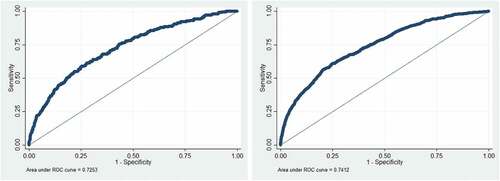

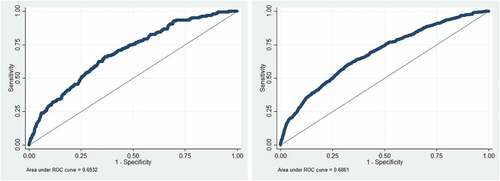

The current study seeks to determine if taking preventive actions effectively reduces exposure to identity theft, and whether this effectiveness differs for prior victims and non-prior victims. The variable ‘prior victim’ was used to divide the original sample into two subsamples. The variable asked a respondent if he or she was a victim of identity theft prior to the past 12 months (0 = no and 1 = yes). The prior victim sample had 23,624 cases, and the non-prior victim sample had 200,500 cases. A descriptive statistical analysis was then performed to derive a ‘big picture’ of the several independent variables across these two samples. Chi-square tests and independent-sample t-tests were used to examine differences between the two samples regarding a number of variables of interest. Finally, a series of binary logistic regressions were used to identify significant factors related to identity theft victimization emerging under conditions of controlled multivariate comparisons. To illustrate model fit, the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve and the area under the curve (AUC) were both generated for each regression model (Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021b). Based on prior studies, a model is considered to be excellent if AUC lies between 0.9 and 1.0. A model is considered to be good if its AUC falls between 0.8 and 0.9. A model is considered to be fair if AUC falls between 0.7 and 0.8. And a model is considered to be poor if its AUC is less than 0.7 (Fawcett Citation2006; Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021b).

Results

displays the study descriptive statistics. Regarding all five measures of identity theft used by the creators of the NCVS ITS survey, prior victims (i.e., those who had been an identity theft victim outside of the past 12 months) were more likely to be victimized again than non-prior victims. These group differences were statistically significant across all five measures. For example, the percentage of victims of opening new accounts among prior victims (1%) was double that of non-prior victims (0.5%). Similarly, the percentage of victims of misused credit cards among prior victims (9.4%) was almost 2.5 times greater than that among non-prior victims (3.8%).

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for all Variables for Prior Victims and Non-prior Victims.

Regarding independent variables among two samples, there were more White respondents in the prior-victim sample and more African American and Asian respondents in the non-prior victim sample. In terms of ethnicity, there were more Hispanic respondents in the non-prior-victim sample than in the prior victim sample. On average, prior victims had higher educational levels, higher incomes, and moved more frequently than non-prior victims. They were more likely to have a job and be married than non-prior victims. Regarding online shopping behavior, prior victims had a higher online shopping frequency than non-prior victims, and they were more likely to use credit and debit cards to complete online purchases.

Regarding preventive actions, prior victims took more protective actions than non-prior victims. Specifically, compared to non-prior victims, prior victims changed their passwords on financial accounts, shredded documents, and checked banking statements for unfamiliar charges more frequently. In addition, they were more likely to purchase credit monitoring services, use security software programs, and purchase identity theft protection from a company. Interestingly, non-prior victims were more likely to check their credit card reports than prior victims.

The next five tables display the results of logistic regression models on the five measures of identity theft used by the authors of the NCVS ITS survey. sets forth the results of explaining misused checking/saving accounts among prior victims (i.e., Model 1) and non-prior victims (i.e., Model 2). Model 1 is statistically significant (χ2 = 691.53, p < 0.001). The AUC is 0.701, which means the model is considered to be fair with regard to model fit (). Compared to males, females were more likely to be identity theft victims. Compared to white respondents, African American respondents were more likely to be identity theft victims. Hispanic respondents were more likely to be identity theft victims than non-Hispanic persons. Respondents who did online shopping and used debit cards more often were more likely to be victims of misused checking/saving accounts. However, respondents who used credit cards more often were less likely to be the victims, which makes rather good sense because debit cards, unlike credit cards, are always related to specific checking/saving accounts. Regarding seven preventive actions, surprisingly, two actions (i.e., checking credit reports and purchasing monitoring protection) were not significant factors, and four actions (i.e., changing passwords, using credit monitoring services, checking bank statements, and using security software) were positively related to victimization by misuse of checking/saving accounts. Based on odds ratio statistics, the most influential preventive action was changing passwords, followed by checking bank statements. Only shredding documents was indicated to be a factor that substantively reduced the likelihood of misused checking/saving accounts.

Table 2. Logistic Regression Models of Misuse of Checking/Saving Accounts.

Model 2 is also statistically significant (χ2 = 4058.73, p < 0.001). The AUC is 0.729, which means the model fit is considered to be fair. It has many similar significant factors observed in Model 1, including gender, being African American, online shopping frequency, online payment with credit cards, and online payment with debit cards. There are some differences between Model 1 and Model 2, however. For example, Model 2 indicates that having a job would increase the likelihood of being the victim of misused checking/saving accounts. Regarding seven preventive actions, Model 2 findings suggest that five of them (i.e., checking credit reports, changing passwords, using credit monitoring services, checking bank statements, and purchasing protection) were positively related to identity theft victimization. Based on odds ratio statistics, the most influential preventive action was frequently changing passwords, followed by checking bank statements and using credit monitoring services. Similar to Model 1, Model 2 findings suggest that only regularly shredding documents substantively reduced the likelihood of being a victim of misused checking/saving accounts.

shows the models of victimization by misuse of credit cards among prior victims (i.e., Model 3) and non-prior victims (i.e., Model 4). Model 3 is statistically significant (χ2 = 861.42, p < 0.001). The AUC is 0.691, which means the model is considered to be poor in fit but acceptable (). It indicates that respondents who were male and had higher educational level were more likely to be victims of misuse of credit cards compared to respondents who were female and had lower educational level. Respondents who did frequent online shopping and used credit cards more often were more likely to be victims of misuse of credit cards. Additionally, respondents who used debit cards more often were less likely to experience misuse of credit cards since credit cards were closely related to credit card accounts. Once again, the model suggests that three of the seven preventive actions (i.e., changing passwords, using credit monitoring services, and checking bank statements) were positively related to the victimization by misuse of credit cards. According to odds ratio statistics, the most influential preventive action was checking bank statements, followed by using credit monitoring services. Only shredding documents regularly substantially reduced the likelihood of being a victim of misuse of credit cards.

Table 3. Logistic Regression Models of Misuse of Credit Cards.

Model 4 is also statistically significant (χ2 = 3936.78, p < 0.001). The AUC is 0.720, which means the model is considered to be fair with respect to model fit. It has some similar significant factors to those observed in Model 3, including gender, educational level, online shopping frequency, online payment with credit cards, and online payment with debit cards. Model 4 also reveals that African American respondents were less likely to be victims of misuse of credit cards compared to white respondents. Non-Hispanics were less likely to be victims of misuse of credit cards, too. Regarding seven preventive actions, similar to Model 3, Model 4 results suggest that only the shredding of personal information-bearing documents is negatively related to misuse credit cards, while three other actions (i.e., changing passwords, using credit monitoring services, and checking bank statements) were positively related to the victimization. Based on odds ratio statistics, checking bank statements was the most influential prevention action in predicting misuse of credit cards among non-prior victims.

sets forth the models of victimization of other types among prior victims (i.e., Model 5) and non-prior victims (i.e., Model 6). Other types of victimization typically include telephone accounts, PayPal accounts, and iTunes accounts. Model 5 is statistically significant (χ2 = 183.17, p < 0.001). The AUC is 0.701, which means the model is considered to be fair with respect to model fit (). Compared to white respondents, African Americans were more likely to be victims of misuse of other types. Respondents who did not have a job were more likely to be among this type of victim. Purchasing things online with credit cards or debit cards was no longer related to misuse of other types, but online shopping frequency was still significantly and positively related to this type of victimization. Among seven preventive actions, four of them were not significant factors. Three of them (i.e., changing passwords, using credit monitoring services, and using security software) were, once again, positively related to victimization of other types. Changing passwords was the most influential prevention action in predicting misuse of other types among prior identity theft victims, followed by using security software programs and using credit monitoring services.

Table 4. Logistic Regression Models of Misuse of Other Types.

Model 6 shows misuse of other types among non-prior identity theft victims. The model is statistically significant (χ2 = 840.43, p < 0.001). The AUC is 0.746, which means the model is considered to be fair in terms of fit. It reveals that respondents who had a higher educational level and moved more frequently were more likely to be victims of misuse of other types. Online shopping frequency and online payment with debit cards were significant factors in this type of victimization. Three of the seven preventive actions (i.e., shredding documents, using security software programs, and purchasing identity theft protection) had no impact on misuse of other types. Four actions (i.e., checking credit reports, changing passwords, using credit monitoring services, and checking bank statements) were positively related to misuse of other types. Once again, changing passwords was the most influential prevention action in predicting misuse of other types among non-prior identity theft victims, followed by using credit monitoring services and checking bank statements.

shows the findings of the models of victimization of opening new accounts among prior victims (i.e., Model 7) and non-prior victims (i.e., Model 8). Model 7 is statistically significant (χ2 = 169.12, p < 0.001). The AUC is 0.725, which means the model is considered to be fair in model fit (). Compared to whites and non-Hispanics, African Americans and Hispanics were more likely to be the victims of opening new accounts. Undoubtfully, online shopping frequency was positively related to this type of identity theft. However, surprisingly online payment with credit cards or debit cards did reduce the likelihood of being victims of opening new accounts. Among seven preventive actions, frequently checking bank statements was negatively related to opening new accounts among prior victims. However, four preventive actions (i.e., checking credit reports, changing passwords, using credit monitoring services, and purchasing identity theft protection) were positively related to this type of identity theft victimization. Based on odds ratio statistics, the most influential preventive action was purchasing identity theft protection among prior victims, followed by changing passwords and checking credit reports.

Table 5. Logistic Regression Models of Opening New Unauthorized Accounts.

Model 8 is also statistically significant (χ2 = 725.08, p < 0.001). The AUC is 0.741, which means the model is considered to be fair with respect to model fit. Compared to Model 7, it reveals more demographic variables being related to opening new unauthorized accounts. Specifically, respondents who were married and had a job were less likely to be victims. Online shopping frequency was positively related to this type of victimization and using credit cards to complete online purchasing reduced the likelihood of being victims of opening new accounts. Just like the findings shown in Model 7, four of the seven preventive actions (i.e., checking credit reports, changing passwords, using credit monitoring services, and purchasing identity theft protection) were positively related to opening new unauthorized accounts. Changing passwords was the most influential preventive action in predicting opening new unauthorized accounts among non-prior identity theft victims, followed by purchasing identity theft protection and using credit monitoring services.

Finally, shows the models of victimization of using personal information for other fraudulent purposes (e.g., getting a job, renting a house, and receiving medical care) among prior victims (i.e., Model 9) and non-prior victims (i.e., Model 10). While this type of identity theft was not very common, there were still a few significant findings to be noted. Model 9 is statistically significant (χ2 = 84.24, p < 0.001). The AUC is 0.693, which means the model is considered to be poorly fitting but acceptable (). Compared to males, females were more likely to be this type of identity theft victim. Online shopping frequency was positively related to using personal information for other fraudulent purposes. However, completing online payments with credit cards was a negative factor. Three preventive actions (i.e., changing passwords, using credit monitoring services, and purchasing protection) were positively related to this type of victimization among prior identity theft victims. Based on odds ratio statistics, changing passwords was the most influential preventive action among prior identity theft victims, followed by purchasing identity theft protection.

Table 6. Logistic Regression Models of Victim of Fraudulent Information Being Added to Records &/or Personal Accounts.

Model 10 is also statistically significant (χ2 = 300.66, p < 0.001). The AUC is 0.686, which means the model fit is considered to be poor but acceptable. Among non-prior identity theft victims, being Hispanic and having a higher educational level increased the likelihood of being a victim of this type of identity theft. Having a job and a higher income level reduced the likelihood. Online shopping frequency was not a significant factor in Model 10 but completing online purchasing with credit cards was still a negative factor relating to using personal information for other purposes fraudulently. Four preventive actions (i.e., changing passwords, checking credit reports, using credit monitoring services, and purchasing protection) were positively related to this type of victimization among non-prior identity theft victims. Using credit monitoring services was the most influential preventive action, followed by changing passwords and purchasing identity theft protection.

Discussion

Although identity theft has received much research attention in the recent decade, studies on preventive actions remain limited in number and scope. Using three waves of the ITS, this study explores two core research questions: 1) are identity theft preventive actions related to one’s likelihood of identity theft victimization? and 2) do identity theft preventive actions play a different role in explaining identity theft victimization between victims who had been victimized in the past (i.e., prior victim) and victims who had not been previously victimized (i.e., non-prior victim)? Overall, the findings suggest that all three reactive preventive actions (i.e., checking credit reports, checking bank statements, and using credit monitoring services) either have no significant relationship with identity theft victimization or have even a positive relationship with it (with the lone exception of checking bank statements in Model 7). This finding is consistent with some previous findings that reactive preventive actions may not reduce identity theft victimization to any noteworthy degree (Burnes, DeLiema, and Langton Citation2020; Reyns and Henson Citation2016; Williams Citation2016).

There are two possible explanations that might explain these results. First, the reactive preventive actions are not performed to deter identity theft. Instead, these actions are used to reduce loss when identity theft occurs (Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a). For example, in checking bank statements it is impossible to know if an unauthorized purchase will happen in ensuing months; while it is relatively easy to identify an unauthorized past purchase, it is very difficult to know if future unauthorized purchases are going to be made by nefarious parties in possession of one’s personal information. Second, as with prior research (Burnes, DeLiema, and Langton Citation2020; Williams Citation2016), a causal relationship cannot be established in the current study because cross-sectional data are used to explore identity theft. In other words, although the current study can document a positive relationship between reactive preventive actions and identity theft, it is not safe to conclude that reactive preventive actions themselves lead to identity theft. For example, a person may check credit reports and bank statements more frequently precisely because he or she engages in more risky activities that may increase the likelihood of being an identity theft victim. A conservative conclusion within the context of use of cross-sectional data would seem to be that reactive preventive actions likely do not prevent identity theft.

Regarding proactive preventive actions, all three modern proactive preventive actions (i.e., changing passwords frequently, using security software programs, and purchasing identity theft protection) either have a positive relationship to identity theft or have no significant relationship. Our findings reported here are consistent with some prior research reported in the literature (e.g., Holt and Bossler Citation2008; Leukfeldt Citation2014; Marcum Citation2008; Reyns and Henson Citation2016; Williams Citation2016). Once again, due to the limitation of the cross-sectional data, the current study cannot draw a solid conclusion that proactive preventive actions themselves increase identity theft. However, if they do, this may be due to two possible reasons. First, as Liu explains in a 2019 study, ‘rational actor’ individuals may underestimate identity theft risk and engage in more risky activities if they think they are safe because of security programs and the identity theft insurance they purchase. Second, individuals must provide their sensitive personal information when they use modern proactive preventive actions. For example, they must reveal their social security numbers (SSN) to agencies to purchase identity theft monitoring protection and to purchase identity theft insurance. Likewise, they must reveal their passwords to security software program vendors and insurers. Such actions inevitably increase the likelihood of sensitive information being breached. In the worst-case scenario, security companies intentionally sell the information for profit.

On a much-needed positive note, the current study’s finding showing that one traditional proactive preventive action – the shredding of personal information-bearing documents – negatively relates to identity theft victimization (Burnes, DeLiema, and Langton Citation2020; Dean, Buck, and Dean Citation2014; Lai, Li, and Hsieh Citation2012). This finding raises the question of whether some ‘new-fashion’ preventive actions might do a better job of identity theft protection than ‘old-fashion’ preventive actions. Regarding the second research question, prior victims were more likely to be victimized again than non-prior victims on all five measures of identity theft used by the authors of the NCVS ITS survey. Besides, the overall findings suggest that commonly employed preventive actions show little efficacy for either prior victims or non-prior identity theft victims.

The current study confirms some previous findings suggesting that online behavior tends to impact different types of identity theft (Holtfreter et al. Citation2015; Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a; Reyns Citation2013). Individuals who shop online more frequently are more likely to be victims of the misuse of their checking/saving accounts, credit cards, and the danger of nefarious persons opening new unauthorized accounts in their names. An interesting finding is that online shopping with credit cards can reduce the likelihood of being victims of misuse of checking/saving accounts and opening new accounts, but increase the likelihood of being a victim of misuse of said credit cards. Meanwhile, online shopping with debit cards can reduce the likelihood of being victims of misuse of credit cards but increase the likelihood of being victims of misuse of checking/saving accounts. This finding fits common logic. Since online shopping platforms often require customers to complete payments online, it seems clear that individuals should prefer using credit cards to debit cards for online purchasing. Reimbursement policies maintained by credit card companies are typically much better than those attached to regular bank or savings-and-loan institutional accounts.

Based on our findings, we propose some noteworthy suggestions on preventing identity theft victimization. First, the significance of online shopping behavior on identity theft victimization indicates that preventive actions related to online behavior should be effective in preventing identity theft (Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a). However, preventive actions related to online behavior (e.g., changing passwords frequently and using security software programs) would seem to have very poor efficacy. It seems clear that individuals would be well advised to exercise a very high level of care about their online behavior. For instance, individuals should be advised to only visit certified websites – a lock icon in front of a web address shows up in an Internet explorer indicating a certification. Internet users would also be well advised to deal with online payments with great caution (Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a). Second, most preventive actions measured by the current study, either proactive or reactive, have been found to be of extremely limited efficacy in preventing identity theft. To be noted, the current study shows that conventional preventive actions do not demonstrate great efficacy in the prevention of identity theft.

Nevertheless, our findings do not suggest that these actions are completely useless in dealing with the risk of identity theft. For example, while checking credit reports and bank statements frequently may not reduce the likelihood of future identity theft, investigations made into known cases of identity theft do help the financial institutions and law enforcement identify patterned activities and identify habitual identity theft actors. Moreover, it can help victims detect their victimization early in order to prevent further loss. Also, while purchasing identity theft protection does not prevent identity theft (Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a) it often can compensate victims for their financial loss.

That said, it may well be the case that individuals may be inclined to underestimate identity theft risk and engage in more risky activities if they think they are safer after purchasing these security programs and insurance (Liu Citation2019). Policymakers may need to regulate more closely the advertisements made by identity theft protection companies, marketing come-ons which may give their customers false expectations as to their level of safety (also see Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a, p. 490). Besides, the ‘no-big-difference’ finding between prior identity theft victims and non-prior identity theft victims indicates that most preventive actions do not prevent individuals from being either identity theft victims in the first place or repeated victims. Perhaps the best practice advice is to minimize the sharing of personal information as a general rule of responsible Internet use.

It is unrealistic to ask individuals to limit their use of the Internet, especially after our collective experience with the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, a vast amount of personal data is often stored by commercial companies. A recent study interviewed industry insiders, asking about their perspectives on preventing identity theft. The study points out that ‘there is a pressing need for many companies to update antiquated technology that may be 30 years old or older, and that often is mixed with new technology’ (Piquero et al. Citation2021, p. 457). Some new information security technologies (e.g., two-factor authentication and biometric identifiers), according to insiders’ knowledge, can be effective tools of fighting identity theft (Piquero et al. Citation2021). Perhaps the federal government needs to regulate more aggressively those companies that store substantial amounts of personal information to enhance the likelihood of their use of emerging data security technologies.

As with all research, some study limitations require mention. First, the current study only includes online shopping as an indicator of survey respondent online behavior. Many types of online behavior, such as downloading, are not tested in the current study. Furthermore, many types of online payments, such as e-commerce payment systems (e.g., PayPal, Apple Pay, and Zelle), are not tested either. Considering that many individuals have started using these e-commerce payment systems for online purchasing and interpersonal transactions, it is important to include them in future research. Second, the cross-sectional data used in the current study cannot detect any causal relationship between identity theft victimization and preventive actions (Burnes, DeLiema, and Langton Citation2020; Hu, Zhang, and Lovrich Citation2021a; Williams Citation2016). Future research should attempt to implement a longitudinal research design. Panel studies, in which reactive and proactive actions are measured prior to the period in which victimization is measured would solve this problem in future studies.

Third, the current study only focuses on the seven preventive actions measured by NCVS ITS. There may be other preventive actions worthy of exploring, as listed on the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) website (https://www.consumer.ftc.gov/topics/identity-theft). For example, digital personal information can be encrypted. Additional personal credentials can be required for sensitive transactions, such as fingerprints, facial images, retina scans, and similar forms of multi-factor authentication. Technological approaches, such as biometric and dark web scanning, may also help fight identity theft (Piquero et al. Citation2021). Future research should include explorations of these preventive actions. Finally, the current study analyzes only five commonly-experienced types of identity theft victimization. There are more types of identity theft that have not been adequately studied, such as child identity theft, medical identity theft, and tax identity theft. Future research must be carried out in these important areas as well.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Xiaochen Hu

Xiaochen Hu is an Associate Professor in the Department of Criminal Justice at Fayetteville State University. He received his Ph.D. in Criminal Justice from Sam Houston State University. He conducts both quantitative and qualitative studies related to police decision making, police culture, community-oriented policing, gangs, and criminal justice and mass media.

Jae-Seung Lee

Jae-Seung Lee is an Assistant Professor of criminal justice program at Northern Kentucky University. His research focuses on crime prevention, police-community relations, police practices, and cybercrime.

Nicholas P. Lovrich

Nicholas P. Lovrich is a Regents Professor Emeritus and Claudius O. and Mary W. Johnson Distinguished Professor of Political Science in the School of Politics, Philosophy and Public Affairs at Washington State University. He is a graduate of Stanford University, and received his Ph.D. in Political Science from U.C.L.A. He has worked with federal, state, tribal, campus, county and municipal law enforcement agencies on applications of community policing concepts in carrying out the missions of those agencies over the course of the past three decades.

References

- Albrecht, C., C. Albrecht, and S. Tzafrir. 2011. “How to Protect and Minimize Consumer Risk to Identity Theft.” Journal of Financial Crime 18 (4): 405–414. doi:10.1108/13590791111173722.

- Allison, S. F., A. M. Schuck, and K. M. Lersch. 2005. “Exploring the Crime of Identity Theft: Prevalence, Clearance Rates, and victim/offender Characteristics.” Journal of Criminal Justice 33 (1): 19–29. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2004.10.007.

- Anderson, K. B. 2006. “Who are the Victims of Identity Theft? the Effect of Demographics.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 25 (2): 160–171. doi:10.1509/jppm.25.2.160.

- Baum, K. (2006). Identity theft, 2004. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved 22 January 2020, from https://bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/it04.pdf (accessed 15 October 2021).

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2016. National Crime Victimization Survey: Identity Theft Supplement, 2016. Washington, DC: United States Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs.

- Burnes, D., M. DeLiema, and L. Langton. 2020. “Risk and Protective Factors of Identity Theft Victimization in the United States.” Preventive Medicine Reports 17: 101058. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101058.

- Chapple, M. (2019). “Taking Social Security Numbers Public Could Fix Our Data Breach Crisis”. CNN Business Perspectives. Available at https://www.cnn.com/2019/06/05/perspectives/labcorp-quest-diagnostics-data-breach-social-security-numbers/index.html (accessed 18 February 2021).

- Choi, K. S. 2008. “Computer Crime Victimization and Integrated Theory: An Empirical Assessment.” International Journal of Cyber Criminology 2 (1): 308–333.

- Copes, H., and L. M. Vieraitis. 2009a. “Bounded Rationality of Identity Thieves: Using Offender‐based Research to Inform Policy.” Criminology & Public Policy 8 (2): 237–262. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9133.2009.00553.x.

- Copes, H., and L. M. Vieraitis. 2009b. “Understanding Identity Theft: Offenders’ Accounts of Their Lives and Crimes.” Criminal Justice Review 34 (3): 329–349. doi:10.1177/0734016808330589.

- Copes, H., K. R. Kerley, R. Huff, and J. Kane. 2010. “Differentiating Identity Theft: An Exploratory Study of Victims Using a National Victimization Survey.” Journal of Criminal Justice 38 (5): 1045–1052. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.07.007.

- Cowley, S. (2019). “Equifax to Pay at Least $650 Million in largest-ever Data Breach Settlement”. New York Times Business. New York Times. Retrieved 27 January 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/22/business/equifax-settlement.html (accessed 15 October 2021).

- Dean, P. C., J. Buck, and P. Dean. 2014. “Identity Theft: A Situation of Worry.” Journal of Academic and Business Ethics 1 (1): 1–14.

- European Commission. (2020). “Survey on Scams and Fraud Experienced by Consumers: Final Report. EU Consumer Programme”. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/aid_development_cooperation_fundamental_rights/ensuring_aid_effectiveness/documents/survey_on_scams_and_fraud_experienced_by_consumers_-_final_report.pdf (accessed 6 June 2022).

- Fawcett, T. 2006. “An Introduction to ROC Analysis.” Pattern Recognition Letters 27 (8): 861–874. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2005.10.010.

- Gibert, J., and N. Archer. 2012. “Consumer Identity Theft Prevention and Identity Fraud Detection Behaviours.” Journal of Financial Crime 19 (1): 20–36.

- Golladay, K., and K. Holtfreter. 2017. “The Consequences of Identity Theft Victimization: An Examination of Emotional and Physical Health Outcomes.” Victims & Offenders 12 (5): 741–760. doi:10.1080/15564886.2016.1177766.

- Golladay, K. A. 2017. “Reporting Behaviors of Identity Theft Victims: An Empirical Test of Black’s Theory of Law.” Journal of Financial Crime 24 (1): 101–117. doi:10.1108/JFC-01-2016-0010.

- Harrell, E., and L. Langton (2013). “Victims of Identity Theft, 2012”. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Available at https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/vit12.pdf (accessed 22 January 2020).

- Harrell, E. (2015). “Victims of Identity Theft, 2014”. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Available at https://bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/vit14.pdf (accessed 22 January 2020).

- Harrell, E. (2019). “Victims of Identity Theft, 2016”. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Available at https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/vit16.pdf (accessed 20 January 2020).

- Holt, T. J., and A. M. Bossler. 2008. “Examining the Applicability of lifestyle-routine Activities Theory for Cybercrime Victimization.” Deviant Behavior 30 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1080/01639620701876577.

- Holt, T. J., and M. G. Turner. 2012. “Examining Risks and Protective Factors of on-line Identity Theft.” Deviant Behavior 33 (4): 308–323. doi:10.1080/01639625.2011.584050.

- Holtfreter, K., M. D. Reisig, T. C. Pratt, and R. E. Holtfreter. 2015. “Risky Remote Purchasing and Identity Theft Victimization among Older Internet Users.” Psychology, Crime & Law 21 (7): 681–698. doi:10.1080/1068316X.2015.1028545.

- Hu, X., J. Wu, M. J. DeValve, and B. S. Fisher. 2020. “Exploring Violent Crime Reporting among school-age Victims: Findings from NCVS SCS 2005-2015.” Victims & Offenders 15 (2): 141–158. doi:10.1080/15564886.2019.1705452.

- Hu, X., X. Zhang, and N. Lovrich. 2021a. “Forecasting Identity Theft Victims: Analyzing Characteristics and Preventive Actions through Machine Learning Approaches.” Victims & Offenders 16 (4): 465–494. doi:10.1080/15564886.2020.1806161.

- Hu, X., X. Zhang, and N. Lovrich. 2021b. “Public Perceptions of Police Behavior during Traffic Stops: Logistic Regression and Machine Learning Approaches Compared.” Journal of Computational Social Science 4 (1): 355–380. doi:10.1007/s42001-020-00079-4.

- Internet Crime Complaint Center. (2022). “Internet Crime Report 2021”. Federal Bureau of Investigation”. Available at https://www.ic3.gov/Media/PDF/AnnualReport/2021_IC3Report.pdf (Accessed 6 June 2022).

- Lai, F., D. Li, and C. T. Hsieh. 2012. “Fighting Identity Theft: The Coping Perspective.” Decision Support Systems 52 (2): 353–363. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2011.09.002.

- Leukfeldt, E. R. 2014. “Phishing for Suitable Targets in the Netherlands: Routine Activity Theory and Phishing Victimization.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 17 (8): 551–555. doi:10.1089/cyber.2014.0008.

- Liu, F. 2019. “Does Identity Theft Insurance Undermine Risk Perceptions and Increase Risky Behavioral Intentions?” Asian Economic and Financial Review 9 (8): 926–935. doi:10.18488/journal.aefr.2019.98.926.935.

- Marcum, C. D. 2008. “Identifying Potential Factors of Adolescent Online Victimization for High School Seniors.” International Journal of Cyber Criminology 2 (2): 346–367.

- Piquero, N. L., M. A. Cohen, and A. R. Piquero. 2011. “How Much Is the Public Willing to Pay to Be Protected from Identity Theft?” Justice Quarterly 28 (3): 437–459. doi:10.1080/07418825.2010.511245.

- Piquero, N. L., A. R. Piquero, S. Gies, B. Green, A. Bobnis, and E. Velasquez. 2021. “Preventing Identity Theft: Perspectives on Technological Solutions from Industry Insiders.” Victims & Offenders 16 (3): 444–463. doi:10.1080/15564886.2020.1826023.

- Pontell, H. 2002. “Pleased to Meet You … Won’t You Guess My Name: Identity Fraud, cyber-crime, and white-collar Delinquency.” Adelaide Law Review 23 (2): 305–328.

- Randa, R., and B. W. Reyns. 2020. “The Physical and Emotional Toll of Identity Theft Victimization: A Situational and Demographic Analysis of the National Crime Victimization Survey.” Deviant Behavior 41 (10): 1290–1304. doi:10.1080/01639625.2019.1612980.

- Rebovich, D. J. 2009. “Examining Identity Theft: Empirical Explorations of the Offense and the Offender.” Victims and Offenders 4 (4): 357–364. doi:10.1080/15564880903260603.

- Reisig, M. D., T. C. Pratt, and K. Holtfreter. 2009. “Perceived Risk of Internet Theft Victimization: Examining the Effects of Social Vulnerability and Financial Impulsivity.” Criminal Justice and Behavior 36 (4): 369–384. doi:10.1177/0093854808329405.

- Reyns, B. W. 2013. “Online Routines and Identity Theft Victimization: Further Expanding Routine Activity Theory beyond direct-contact Offenses.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 50 (2): 216–238. doi:10.1177/0022427811425539.

- Reyns, B. W., and B. Henson. 2016. “The Thief with a Thousand Faces and the Victim with None: Identifying Determinants for Online Identity Theft Victimization with Routine Activity Theory.” International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 60 (10): 1119–1139. doi:10.1177/0306624X15572861.

- van de Weijer, S. G., R. Leukfeldt, and W. Bernasco. 2019. “Determinants of Reporting Cybercrime: A Comparison between Identity Theft, Consumer Fraud, and Hacking.” European Journal of Criminology 16 (4): 486–508. doi:10.1177/1477370818773610.

- Williams, M. L. 2016. “Guardians upon High: An Application of Routine Activities Theory to Online Identity Theft in Europe at the Country and Individual Level.” British Journal of Criminology 56 (1): 21–48. doi:10.1093/bjc/azv011.