ABSTRACT

This qualitative study seeks to fill a gap in the literature by providing state police agencies with specific strategies to improve diversity recruitment and hiring. Enhanced agency legitimacy is discussed as a potential by-product of creating a more diverse workforce. The intent of this study is not to evaluate legitimacy or prove diversity recruitment will positively affect the overall perceptions of agency legitimacy. Seven focus groups of sworn female (n = 15) and minority (n = 23) state police officers from a mid-south state police agency are organized to provide insight into diversity recruiting challenges and strategies. We conducted thematic analysis to isolate the themes from the focus groups. The themes resulted in a compilation of diversity recruitment strategies. Additional strategies were added based on the literature. Recommendations are provided for improving diversity recruitment and hiring within state police agencies through a holistic approach.

Introduction

Perhaps many of the issues plaguing American law enforcement result from a lack of perspective and inadequate representation within its sworn ranks. Some believe the diversification of law enforcement agencies is a necessary step in improving legitimacy through enhanced police-community relations (Tyler Citation2004). It is important to note that diversification includes all genders, orientations, races, and ethnicities, not just females, African Americans, and Hispanics. State police agencies possess unique characteristics which set them apart from other law enforcement such as statewide jurisdiction, criminal enforcement, traffic enforcement, motor vehicle enforcement and working in rural and unincorporated areas. This paper seeks to provide a basis for recruiting diverse applicant populations specifically for state police agencies.

The effect of diversification within law enforcement agencies has been studied. However, studies have not narrowly focused on state police agencies. Many positive benefits have been attributed to representative police forces from improved community trust (Fridell et al. Citation2001; IACP Citation2007; McDevitt, Farrell, and Wolf Citation2008; Rowe and Ross Citation2015); to legitimacy (Tyler Citation2004); to problem solving and cultural understanding (COPS Citation2009; White and Escobar Citation2008); and community partnerships (Lasley et al. Citation2011). Alas, law enforcement agencies often struggle with diversification (Koper et al. Citation2001; Wilson et al. Citation2010).

Attracting diverse police applicants has been challenging for most law enforcement agencies (Wilson et al. Citation2010; Donohue Citation2020) especially in recent times (IACP Citation2020). Donohue (Citation2020) systematically reviewed law enforcement selection processes available between 2000 and 2018. Donohue (Citation2020) identified four areas which affect diversifying law enforcement agencies. These areas are identified as: 1) effective recruitment strategies; 2) screen process barriers; 3) motivations and attitudes; and 4) organizational and external predictors (Donohue, Citation2020). This study touches on several of these areas but focuses on promoting effective recruiting strategies in state police agencies which affect hiring.

In developing the best recruitment strategies for state police agencies, this study synthesizes information gathered from seven focus groups of sworn female and minority officers from one mid-south state police agency (MSP). We use this data to provide guidance for diversity recruiting in state agencies. This study involves only one state police agency and a non-random sample of participants therefore, the results may not be generalizable. However, most results should prove useful to most state police agencies because of the commonalities most share. Specifically, this paper will address prioritization, leveraging resources, outreach efforts, organizational characteristics, compensation, selection process barriers, marketing, micro-targeting, organizational subculture and showcasing. In conclusion, we present recommendations for improving diversity recruitment as a potential means of improving police legitimacy.

Literature review

To begin, much of the literature on policing does not focus on state police agencies. Therefore, it is important to define these agencies. State Police, Highway Patrol and Department of Public Safety agencies each have statewide jurisdiction, but some of their core responsibilities may differ depending on the state. For instance, State Police often function similarly to county or municipal police agencies. Whereas Highway Patrol Agencies have responsibilities linked to the road system and related matters. A Department of Public Safety may combine several state agencies together, including entities responsible for law enforcement (Peak and Sousa Citation2022). For this study, State Police, Highway Patrol and Department of Public Safety agencies and sworn personnel within these agencies are called state police agencies and state police officers, respectively. A review of the literature found one academic publication (Whetstone, Reed, and Turner Citation2006) narrowly focused on recruitment in state police agencies, which confirms the existence of a void.

Diversity and legitimacy

While inequities are present in the economy, education and healthcare systems are perhaps the most pressing issues facing American society today. The criminal justice system, specifically law enforcement, has drawn considerable attention in current times. Specifically, an anti-law enforcement sentiment and protests to defund the police seemed to wash over the United States of America in Citation2020. The death of George Floyd and others at the hands of police exacerbated hostilities toward police in 2020 (Brown Citation2021). Thereafter, groups like Black Lives Matter (BLM) gained national prominence and pressured political leaders and law enforcement agencies alike for police accountability, reform, and social justice – while, questioning police legitimacy (Brown Citation2021; Skoy Citation2021).

While the focus of this paper is not to test the impact of agency diversification on legitimacy, based upon the literature, we can infer there may be a correlation (Tyler Citation2004). Many law enforcement agencies police in diverse communities, although they lack comparable diversity within their sworn ranks. This alone can affect perceptions of legitimacy (Tyler Citation2004). To recognize the potential impact of diversity on police legitimacy, it is important to understand it.

Legitimacy is defined as the belief that law enforcement agencies should be permitted to exercise authority to preserve social order, resolve conflicts, and enforce the law (Tyler Citation2004). In this context, the root of legitimacy stems from the work of Weber (Citation1978) originally published in 1922. Weber (Citation1978) suggested the ability to convey authority and issue commands does not rest with those in possession of the power (i.e., the police). Power results from the rules and authorities in place and accepted by individuals subject to the power (i.e., the citizenry). These rules and authorities hold the power of legitimacy, which conveys the belief that we should obey them (Weber Citation1978). This is an important concept in understanding the premise of why people obey the police and the foundation of perceived legitimacy (Tyler Citation2021).

The foundation of police legitimacy centers on three components which the police must exhibit and the citizenry must acknowledge. First, police must earn the trust and confidence of the citizenry (Tyler and Fischer Citation2014). Second, police must possess the willingness of the citizenry to respect and submit to their authority (Tyler and Fischer Citation2014). Third, police actions taken must be deemed moral and appropriate based upon the circumstances (Tyler and Fischer Citation2014). When these three components come together, the police may be viewed as legitimate and the citizenry is more likely to obey laws and be more cooperative. To expound further, Tyler (Citation2004) stated the importance of legitimacy is experienced at two levels: daily interactions with police and characteristics of a community police department. The latter has the potential to influence legitimacy regardless of whether citizens have had direct contact with police officers (Tyler Citation2004). Consequently, it can be inferred that a citizen’s feelings about the police may be influenced by social issues and the demographic composition of sworn officers within the department. Therefore, employing effective recruitment strategies to improve diversity within state police agencies may be an important component in influencing perceptions of legitimacy.

Historically, law enforcement has been a white and male dominated occupation (Archbold and Schulz Citation2012; Donohue Citation2020; Diaz and Nuño Citation2021; Langton Citation2010; Wilson and Grammich Citation2022). This is also the case for MSP, which has 15 female (2.1%) and 24 minority (3.4%) officers within its approximately 700 officer sworn ranks. MSP’s state population is 50.1% female and 12.5% minority, as shown in (Census Citation2022). The percentage of women in state police agencies has stalled since 2000 (PEW Citation2021). Nationally, in 2022, regarding race and ethnicity among all state troopers in the United States, Whites (Non-Hispanic) make up 67.5%, African Americans (Non-Hispanic) make up 11.7%; 14.5% are White or Black Hispanic; 3.4% are Asian American and 2.9% are other. Also nationally, the sex among all state troopers is 84.9% male and 15.1% female (Zippia Citation2022). compares the national demographics of state police officers with all other police officers (Data USA Citation2021; Zippia Citation2022). State police officers’ trend rates are also a point of consideration, which shows the rate for Whites is relatively stable. However, the rate for African Americans is trending downward while the rate for Hispanics is trending upward (Zippia Citation2022).

Table 1. Demographic comparison between MSP and state of residence (2021).

Table 2. National demographic comparisons between state troopers and police officers (2021).

As illustrated, the diversity of a police department may vary by department (Reaves Citation2015) especially when comparing state police and local agencies. Further, while not the focus of this study, it is presumed that diversification is necessary to be effective in policing and may influence perceptions (generally and specifically) of legitimacy in law enforcement agencies that service diverse populations (Tyler Citation2004). An inverse relationship may also be true. Agency legitimacy may affect efforts made by state police agencies to diversify their ranks (Nowacki, Schafer, and Hibdon Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Todak Citation2017). This is an important perspective to examine, which does not result in a ‘zero-sum gain’. State police agencies without diversity may continue to find it difficult to recruit diversity. Hence, negatively affecting their ability to achieve higher levels of operational efficiency within certain communities they serve. Conversely, as state agencies increase diversity, it may become easier to increase and retain diversity within their sworn ranks (Nowacki, Schafer, and Hibdon Citation2021a, Citation2021b). Though an evaluation of the impact of diversification on legitimacy is not the focus of this study, the literature suggests the establishment of a representative police department is an essential component to establishing legitimacy (Tyler Citation2004).

Diversification may be more challenging for state police agencies for many reasons. Though state police agencies are large law enforcement agencies, day-to-day operations may resemble that of smaller agencies in rural communities with undiversified populations. The nature of operations within state police agencies is also unique. First, state police agencies have statewide jurisdiction requiring the delivery of service to an entire state. Second, state police agencies often provide law enforcement services to communities which do not have adequate law enforcement. Third, state police agencies operate primarily in rural areas of a state. As a result, prospective applicants will be required to live in or near their duty assignment area. This creates the possibility of having to relocate or commute long distances, resulting in separation from their family and social support networks. Relocation could create work-family conflict (WFC) among minority officers because of stress and burnout (Griffin and Sun Citation2018). And commuting could create a personal and/or financial strain for state police officers working for state agencies that do not support payment for commute time in marked patrol vehicles (Brown Citation2022). Fourth, the work of state police agencies often occurs in unincorporated areas with geographically dispersed populations, causing officers to work with little or no backup. Hence, potentially, creating a more dangerous work environment, resulting in officer safety concerns. Lastly, working in geographically disperse areas with limited resources or support places significant work demands on officers. This may require them to be well-versed in all aspects of enforcement, from traffic to criminal and all facets of investigative procedures (Burns Citation2014). Since the job requirements of a state police officer are not likely to change, any or all of these factors may create difficulties in diversity recruiting.

For these reasons, diversity benchmarking is an important consideration in setting diversification goals. To this end, it is important to define diversity by a type of benchmark. This study is concerned with overall agency diversity (i.e., total population) (Wilson and Grammich Citation2022). The total population benchmark is considered most important because variations in population diversity will vary throughout any state with pockets of diversity in various locations.

Further, in developing any viable recruitment strategy, it is important to understand the driving factors and concerns of the diverse populations being targeted. Some females and minorities apply for positions in law enforcement because they feel a need to help their community, see law enforcement as a viable way to transition from the military to a civilian career, or policing was a childhood dream (Gibbs Citation2019). Detractors for females and minorities may include many factors, including perceptions of legitimacy, which may be caused by underrepresentation. Todak (Citation2017) suggested concerns about social justice and legitimacy may adversely affect the recruitment efforts of law enforcement agencies operating with a lack of diversity. Conversely, agencies with more diversity may find it easier to hire diverse candidates (Nowacki et al., Citation2021a).

Recruiting strategies

Agency diversification efforts require strategic focus otherwise; diversification may be difficult to achieve. This is especially true in recent times. As stated, state police agencies are unique and consequently must develop recruitment strategies capable of overcoming their unique characteristics. Many recruitment strategies found in the literature focused on municipal law enforcement agencies and are not specific to state police agencies. This is understandable because there are over 18,000 local police agencies as compared to only 50 state police, highway patrol, or department public safety agencies operating within the United States (USAfacts Citation2020). Therefore, we vetted many strategies from the literature to determine those most beneficial and applicable to state police agencies. The object of this section is not to compare or contrast recruitment strategies between state police and municipal agencies, but to recognize the strategies that may be most viable in addressing the lack of diversity within state police agencies.

For instance, not only is it important for agencies to use traditional methods of outreach to enhance recruitment, but it is also important to employ innovative alternatives when recruiting for diversity. Some of these alternatives may include outreach to religious organizations (Orrick and Director Citation2008) and civil/community groups. Outreach may also be conducted through the creation of developmental programs (Orrick and Director Citation2008) such as early hiring programs, police explorer programs, and leadership academies. Each are excellent means of conducting outreach. Further, they allow the agency to attract diverse candidates at an early age and keep their interest. Efforts should be made to make agency membership attractive as soon as possible.

It is important to note it may not be possible for state police agencies to change all factors viewed as unattractive by applicants. These factors may include childcare challenges, student loan debt, mandated overtime, holiday work, and work flexibility (IACP Citation2020). While a point of contention for some, salary and benefits packages may influence applicant pools. Making these packages more attractive is an action that state police agencies can address with their legislatures. The concept of salary wars has made its way to law enforcement. Some believe salaries are important to police applicants, namely millennials, in deciding where to seek employment (CitationLangham n.d.). Others will argue that financial compensation is not the catalyst for improving recruitment and those who want a career in law enforcement will do so without extensive compensation. This perception may have held some validity during better times when there were ample quantities of police applicants. However, during sparse times, agencies with the best salary and benefits package may attract more applicants (Manolatos, Citation2006). This may be especially true of marketable diverse applicants who may have options. Without a competitive salary and benefits package, it may be difficult for state police agencies to draw diverse applicants from urban areas to engage in rural policing. There may also be components of the selection process which inadvertently affect diversification.

The selection process for police applicants is long, complex (Wilson and Grammich Citation2009) and may serve as an employment barrier for some. It is important for agencies to take an objective look at their selection criteria to determine if it creates a disparate impact or barrier that prohibits any group of potential applicants. One study noted over three-quarters of applicants were hired with pre-existing credit-related problems. This leads to the question, should credit issues serve as a disqualifier and a potential disparate impact for minority and female applicants (Reaves Citation2012)? Other areas of concern are cognitive assessment (i.e., knowledge examinations) and physical fitness standards. State police officers must maintain a high level of occupational readiness because of the unique work demand and limited backup (Cocke, Dawes, and Orr Citation2016). However, because of biological and anatomical differences (Charkoudian and Joyner Citation2004; Wilmore Citation1979), excessive physical fitness standards may create a disparate impact for females (Williams and Higgins Citation2022). Lastly, drug usage policies may be prohibitive for some applicants. Law enforcement agencies cannot and should not hire applicants with a lengthy history of drug use, drug abuse, use of certain types of illicit drugs or current substance addiction. However, currently there are twenty-six states where marijuana is fully legal and forty-six states have some variation in legal status (DISA Citation2021). Further, in today’s society, applicants may be more likely to have used marijuana than in the past based upon the upward trend of drug arrests for marijuana (BJS Citation2021). After addressing hiring barriers, it is important to find effective means to promote employment opportunities within state police agencies.

The promotion of employment opportunities within state police agencies can be done with professional marketing. Professional marketing firms can provide suggestions for improvement, such as brand development and exposure, website enhancement, use of social media (Villeda et al. Citation2019), marketing strategies, online application submission, and targeted recruitment. Expertise in these areas may be lacking amongst agency personnel, resulting in a need to employ marketing professionals. Further, a professional firm may provide access to avenues and opportunities in which agencies do not possess. Professional firms may also assist with micro-targeting specific applicant pools, such as females and minorities.

Today, Millennials and Generation Z are now the target population for law enforcement agencies. These are individuals from high school age to their late 30s. This population seems to value a work/life balance over the Baby Boomer generation, who are more dedicated to their professions. Some work-related characteristics (i.e., work-life balance) in policing may not meld well with Millennials and Generation Z applicants (ICAP Citation2020). Some of these characteristics apply to diverse populations within the range. This means agencies must be more intentional in their efforts to employ concepts like micro-targeting to attract specific applicants. Once they have identified target populations, more agreement and acceptance of diversification efforts is necessary within the state police subculture.

Attempting to make any change within a police subculture can be challenging. Historically, standards and consistencies within law enforcement agencies have been maintained with homogeneous recruitment (i.e., the hiring of like-minded individuals) (Britz Citation1997). Any attempt to diversify an agency may be viewed as an attack on the subculture itself. Some have characterized the police subculture as oppositional because of its rigid ideology, exclusivity, and reluctance to change (Perez and Moore Citation2012). Rigaux and Cunningham (Citation2021) suggest constructing the police subculture in a more heterogenous manner composed of diversity and acceptance of differing viewpoints. As a result, challenging conventional norms which may not embrace diversification initiatives.

Traditionalist cultures like state police agencies may not be accepting of change, specifically body art (i.e., tattoos) which may not coincide with uniform standards. Uniform standards within a state police agency are often rooted in history. Most state police agencies have a policy prohibiting visible tattoos (McMullen and Gibbs Citation2019). Most agencies with ‘no visibility’ tattoo policies are in states with numerous male non-Hispanic White citizens, young military veterans, lower crime rates and lower percentages of Millennial residents. Interestingly, southern agencies, excluding the MSP, are less likely to have a ‘no visibility’ tattoo policy. There may be valid reasons why agencies feel this practice is necessary. However, ‘no visibility’ tattoo policies become problematic when it creates a hiring barrier to exceptional applicants such as young people and military veterans. Rigid tattoo policies may also exclude non-white applicants (McMullen and Gibbs Citation2019). Modifications to practices like this may promote the appearance of acceptance and inclusion within the police subculture. The development of a culture of inclusion may not only be important for diversity recruiting and improving legitimacy, but it may also have an important impact on retention.

The MSP, like many state police agencies, has a mantra that all officers are equal regardless of diverse backgrounds. Mantras such as these are intended to be inclusive and are likely seen as inclusive by members of the agency. Further, unity is a necessary component in a para-military organization (Chappell and Lanza-Kaduce Citation2010). However, this type of messaging may adversely affect an agency’s perception that diversity is lacking and necessary. For some individuals, this type of messaging may be construed as the devaluation of the benefits of diversity and the need to get and keep diversity within the ranks. This may create the perception that, since all officers are alike, diversity does not exist, therefore, is not important or valued. In other words, if all officers are the same, why is there a need for diversity? This type of thought process may be problematic because diversity in law enforcement is important for many reasons, as noted (COPS Citation2009; Fridell et al. Citation2001; IACP Citation2007; Lasley et al. Citation2011; McDevitt, Farrell, and Wolf Citation2008; Rowe and Ross Citation2015; Tyler Citation2004; White and Escobar Citation2008). Each of the aforementioned recruiting strategies or foci from the literature were discussed because they may hold particular relevance for state police agencies focused on improving diversity.

Once recruitment strategies are employed, the question then becomes how to gauge success. What shows successful agency diversification? Benchmarking overall agency diversity (i.e., total population) may be a start (Wilson and Grammich Citation2022). The overall number of sworn state police officers may provide some initial sign of growth. However, over time, it may be more important to ensure that the post/regions of the state that serve the most diverse populations possess the most diversity within their ranks (CALEA Citation2017).

Beyond any successful recruitment campaign, retention issues are the next primary concern. Caution should be taken regarding organizational characteristics that may negate recruitment efforts. Some of these characteristics and unique ways of operating involve agency image, opportunities, extreme discipline, residency requirements and paramilitary structure, to name a few (Perez and Moore Citation2012; Wilson and Grammich Citation2009). Characteristics such as these can create a situation where diversity attrition rates can outpace recruitment efforts. We discuss a number of diversity detractors and potential remedies under the recommendations section of this paper.

Present study

Unfortunately, the extant literature on police recruitment does not provide information specific to state police agencies (Donohue, Citation2020). In addition, studies did not account for the current political and social cultures. Moreover, no known study has examined perceptions of state police officers in recruitment with diversity considered. The purpose of this study is to fill these gaps. To this end, we present information obtained from focus groups on ways to improve the diversity of recruitment. This information will provide a guide to improve the complexion of state police agencies to reflect the states they serve. Further, this may provide a means for improving police legitimacy and operational efficiency.

Methodology

The data for this study was collected during a series of focus groups conducted by the MSP to discuss strategies to better recruit for diversity. The focus groups used both standardized or semi-standardized questions relating to strategies for either recruiting females or minorities. We considered standardized questions formally written and narrowly directed towards specific issues. Semi-standardized questions were non-specific and prompt like. Some questions or prompts and the associated data collected, did not relate specifically to improving diversity recruitment, therefore were excluded in this study. However, some were included to provide context. Similarly, some data collected addressed issues of retention which fell outside of the scope of this study. However, we address retention in recommendations section of this paper.

A member of the MSP Recruitment Team presented the focus group questions or prompts. Another member of the MSP Recruitment Team collected and compiled the data through note taking without the use of audio or video recording equipment. No follow-up interviews or focus groups were conducted. The MSP Recruitment Team leader later provided this data in its original format to the authors for analysis. The authors of this study coded the data provided for analysis. No issues in coding or disagreements were noted in the data provided nor were any discovered during review. This qualitative study has institutional review board approval.

Focus group participant sample

Focus groups have been a point of contention for academics. Academics may fear that by allowing participants to overhear the responses of others, the data may become contaminated or create analysis problems (Krueger Citation2014). The data collection may have been enhanced by using a more academic process (i.e., Academic Research Approach; Krueger Citation2014) regarding rigor, professional transcription, location, etc. However, the MSP was effective in creating diverse participant groups and discussion prompts.

The MSP recruited focus group participants through a solicitation sent by the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the MSP to all MSP state troopers of diverse backgrounds encouraging their voluntary participation. The CEO also expressed to all participants that candid responses were welcome and encouraged to improve agency diversity. The MSP held a vested interest in gathering actionable responses to rectify the present recruitment disparities. Further, the MSP Recruitment Team addressed the potential issue of influenced responses directly prior to each focus group meeting and reiterated a request for candid responses. For these reasons, we believe departmental influences should be minimal, but we cannot suggest some were not influenced. Overall, this process produced reasonably objective results.

Participant totals are an approximation based on the information provided by the MSP. Each focus group contained sworn state troopers of the same makeup as the targeted applicant pool (i.e., females (n = 15) or minorities (n = 23)). The mean number of years of service for female participants was 12.2 and the mean for minorities was 4.375. For this study, minority includes all persons other than those identified as Caucasian/White (Non-Hispanic) and female. Minority focus groups contained only males. Only general personal identifiers were used to identify the participants in this study during data collection.

Semi-standardized focus groups

MSP used two groups of females for the semi-standardized focus groups with discussion prompts. Each group contained approximately five participants, for a total of ten (n = 10). There were also three semi-standardized focus groups of minorities which used discussion prompts. These groups also contained approximately five participants totaling fifteen (n = 15) participants.

Standardized focus groups

MSP used standardized questions for two additional focus groups, one for females and one for minorities. The female focus group contained five (n = 5) participants and the minority focus group contained eight (n = 8) participants. None of the participants were used in more than one focus group.

Focus group design

The emphasis of the semi-standardized focus groups was on how to recruit/attract diversity to the MSP. Additional prompts included: 1) reasons for joining the MSP; 2) reasons for staying with MSP; 3) relationships with MSP officers prior to joining; and 4) why is diversity important. The standardized focus group used many questions to guide the discussion. The questions were: 1) Did recruitment from the agency play a role in your decision to be a state police officer? 2) Why did you choose the MSP over other agencies? 3) What were the top 3 factors you considered when applying to MSP?; 4) Do you have any other family members in law enforcement?; 5) Did you know any (female) state police officers when you applied? If yes, was this a factor in you choosing MSP? 6) What year was your cadet class and what is your class number? 7) Please list all work locations you have been assigned. How many racial minorities were assigned to these work locations? 8) Have female/racial minorities approached you with questions about becoming an officer? If so, what advice do you give them? 9) In your opinion, as a minority officer, why is there such disparity between the number of male and female/white and racial minority officers within the agency?; and 10) What are some things you feel the agency can improve upon in order to recruit and retain females/racial minorities?

Study setting

The data collection for this study occurred during the height of political and social unrest surrounding law enforcement, specifically during August and October 2020. We consider this secondary data because the authors of this study did not collect it. Members of the MSP created and facilitated focus groups. They conducted each focus group session at MSP Headquarters in a classroom setting on different dates and times.

Thematic analysis results

The authors created data categories as the foundation for the thematic analysis. Some themes identified were consistent with the literature and provided a foundation for improving recruitment strategies. To reiterate, the premise of this study is to improve diversity with state police agencies, with the assumption that legitimacy may be an outcome. The data collected from these focus groups and literature provide a basis for improving diversity recruitment.

Semi-standardized focus groups

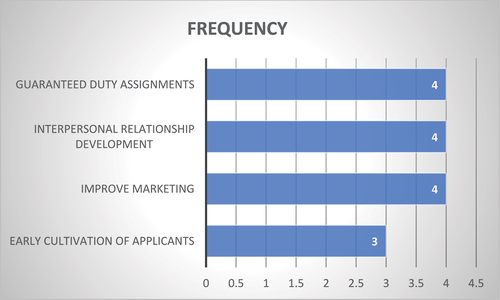

The overarching themes presented from the semi-standardized focus groups fell into four areas: 1) fear of relocation; 2) early cultivation of applicants; 3) interpersonal relationship development; and 4) marketing improvements (). Each theme was discussed at nearly the same frequency throughout all semi-standardized groups. The general sentiment among all participants was that the MSP needs to be intentional in diversity recruiting. One participant stated that members of the agency have to ‘go out and find good applicants’ with the same intensity as pursuing ‘bad guys’. Meaning, once suitable applicants are located, they should be pursued aggressively for employment instead of waiting for applicants to engage the MSP.

As noted in the literature, state police agencies provide law enforcement services throughout the state. The focus group data collected suggests that work location is a significant concern for potential applicants. The first overarching theme suggested ensuring each applicant’s duty assignments at the time of application, thus easing fear of relocation. A potential strategy for easing fear of relocation could be to 1) guarantee each applicant the exact duty assignment of their choice, 2) allow them to select from a regional or grouping of duty assignments or 3) requiring applicants to designate which duty assignments they will work and only hire applicants where those vacancies exist after conducting a workforce analysis.

The next theme identified the need for the MSP to begin a ‘farm/developmental’ program of some variety (e.g., Recruit Program or Leadership Academy). They proposed the MSP begin a program to recruit and hire applicants for immediate fill positions with high turnover, such as telecommunicators and other applicable administrative positions. Many of these positions may be filled by hiring recent high school graduates at age 18. Often, state law prohibits applicants from applying for positions as a state trooper until age 21. The MSP could use this as an opportunity to develop stronger bonds with the applicant, indoctrinate them into the subculture, and cultivate and prepare them for the training academy and life as a state trooper. A strategy such as this could recruit diversity and provide a promise of placement in an upcoming training academy class once any required selection process steps are successfully completed and the age requirement is met.

The following two themes involve the development of interpersonal relationships between the applicant and the officers. One theme involved revitalizing the ride-along program and policy to provide more frequent and substantive engagement. This would provide applicants with an up-close view of the day-to-day operations. Presenting opportunities such as this can help present a realistic impression of law enforcement. One participant took part in a ride-along program and said, ‘it made an impression and meant a lot to him’. This experience ultimately led to him becoming a state police officer. Another theme involved holding informal meetings with a trooper over coffee. This could occur one-on-one or in small groups. This would allow the applicant to get to know the trooper on a personal level and engage in intimate dialogue with them about career, family, and other areas of concern. Each of these suggestions may help clarify the role expectations of an officer (Huey and Ricciardelli Citation2015) amongst police applicants, especially women and minorities, who may not have access to individuals working in the profession.

The last themes uncovered in the semi-standardized focus groups involved improving advertisements to enhance recruitment. A participant stated, ‘if we can’t sell it (i.e., career) by money or benefits, then we have to find another way to sell it to them’. They first suggested better use of billboard advertisements along the roadways in areas where diverse populations live. They also referenced retooling marketing materials to display females and minorities as state police officers. One point of discussion noted diverse applicants may struggle to see themselves in the role of an officer when there is no visual representation available. Presenting evidence of diversity in an agency may validate the applicant’s assessment of their ability to see themselves in the uniform.

Standardized focus groups

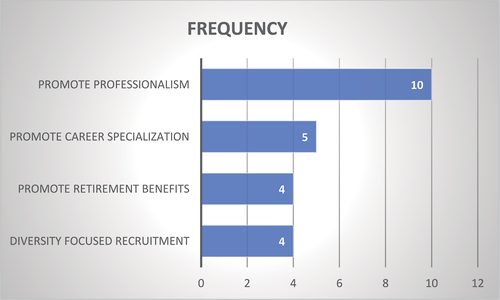

Four overarching themes were also present in the standardized focus groups. The themes identified to enhance diversity recruiting efforts were: 1) promote professionalism; 2) promote career specialization opportunities; 3) promote retirement benefits; and 4) focus recruitment efforts specifically towards diversity (). We utilized frequency of occurrence to prioritize these themes throughout the focus groups. Many other suggestions were made about recruitment but were not considered thematic.

Promoting the professionalism of the MSP was by far the most common theme. Many focus group participants noted the MSP as one of the most professional agencies and felt they should use this as a selling point. Some felt MSP professionalism stemmed from ‘appearance and fitness standards’; ‘how officers carry themselves’; ‘professional standards’; and ‘exclusivity, presences, and demeanor that permeated success’.

Promoting career specialization opportunities was also a reoccurring theme. Many felt full-service state police agencies (i.e., those that regulate criminal, traffic, and commercial motor vehicles) like the MSP present many opportunities for ‘a variety of work tasks’. The group felt specialization was a strength of the MSP, which could be leveraged to separate them from local agencies who may out pace them with salary and incentives. Similarly, the group felt the MSP should leverage the retirement benefits package, although it has changed for the worse in recent years. Last, the groups felt the MSP did not focus recruitment on attracting diversity, specifically females. Most participants felt that targeted recruitment was necessary in order for the agency to improve diversity.

The MSP collected some additional responses and information from the standardized questions, which were not considered thematic but are worth mentioning. Most officers stated that MSP recruitment did not play a role in them joining the MSP. Half of the participants had a family member in law enforcement. All the female participants knew a female officer when they applied. This data supports the premise of homogenous recruitment patterns. Conversely, two-thirds of the minorities did not know a minority officer. This speaks to the need for interpersonal relationship development within minority communities. Most females and minorities stated a female or minority officer advised them of the importance of being physically fit. Finally, when asked of their opinion, why the MSP lacks diversity, a female stated, ‘there will always be a disparity in this type of job’ it is ‘historically a male-dominated field’. They also voiced a concern about maternal family responsibilities conflicting with work demands. Minorities noted the current lack of diversity and described the MSP as ‘predominately white’ which is a detractor for many applicants of diverse background. This supports the premise that improving agency diversity will facilitate further improvement of agency diversity, which was also noted in the literature (Nowacki, Schafer, Hibdon, Citation2021a). Participants also mentioned that urban areas draw minorities because of opportunities such as work location, resources, and living accommodations. As stated, the MSP is primarily a rural law enforcement agency which may be counter-productive in recruiting minorities.

Discussion and recommendations

We gleaned a considerable amount of information from the focus group data and literature. As discussed, the diversification of sworn ranks is necessary and may pave the way toward improving overall agency legitimacy. It will be difficult to diversify without effective recruitment strategies tailored for state police agencies. The focus of this paper is to promote strategies for improving the number of females and minorities in state police agencies. Perhaps greater diversification can lead to a greater sense of institutional trust and confidence and improved feelings about the police. This change in perception can lead to improved police operations (Tyler Citation2004; Tyler and Fischer Citation2014; Tyler Citation2021).

All state police applicants must successfully navigate a selection (hiring) process prior to employment. A state police applicant selection process can be viewed as a metaphorical funnel with all applicants being poured into the top. Not every applicant is suitable for hire as a state police officer. As applicants funnel down the selection process, they are removed or lost at various stages in the process, and the quantity of applicants becomes fewer as the funnel narrows. This includes diverse applicant populations. Hypothetically, if all applicants funnel out at consistent rates, regardless of demographic characteristics, law enforcement agencies must begin with a greater number of diverse applicants if a larger number of diverse hires are to occur. Other factors also affect the applicant pool. For instance, there are many detractors (i.e., work demands, budget) of which law enforcement has little control. For this reason, agencies should employ a more holistic approach, using every available strategy to attract and hire diversity.

Organizational structures within para-military agencies, like state police, typically have clearly defined roles and responsibilities (Maguire Citation2003; MSP Citation2021). Thus, recruitment is likely assigned to a section or branch which will include personnel responsible for recruiting (MSP Citation2021). This model may have been appropriate under normal circumstances, but during lean times, more personnel and resources are necessary to be effective. Agency personnel that work closely with the public may be especially useful in recruitment. Not only do they know where the applicants are, but they have consistent contact with potential applicants and others capable of recruiting. Collectively, agency personnel should understand their role (e.g., image, representation, outreach, and approachability) in recruiting and be challenged to attract applicants, including females and minorities. Enlisting all agency personnel as recruiters is especially important when or if recruiting resources wane. Further, recruitment efforts should include current employees, past employees, and all other individuals connected to the law enforcement agency. Positive efforts in recruiting can be monitored and rewarded with the development of a recruit referral system. However, there may be administrative constraints to overcome before an incentive can be awarded to internal personnel for recruit referrals. Once agency personnel are mobilized to recruit, select outreach options should be implemented.

For instance, religious and civic organizations connected to diverse populations should be contacted to enlist support in recruiting quality candidates. Some of these agencies may not hold law enforcement in high regard, especially during recent times. However, efforts such as this can show a commitment to diversification, improving relationships and service delivery to diverse populations. These types of interactions may provide a direct pathway to diversification and legitimacy. Other types of outreaches can include using other forms of interpersonal interaction. As noted by focus group participants, ‘Female officers need to get into settings like high schools, sporting events, etc. to talk to females about becoming a state police officer’. Participants also suggested improving interpersonal relationships through ‘coffee with an officer’ to allow applicants to address personal questions and concerns. Interpersonal relationships may also be established while candidates take part in developmental programs such as early hire programs, police explorer programs, leadership academies, and filling police support positions. Applicants involved in developmental programs may gain an intimate connection with the agency leading to career employment once they come of age. Further, these interpersonal relations may be a means to developing strong social bonds. Social bonds (Hirschi Citation1969) may help mitigate many of the missteps (e.g., drug use, driving under the influence, criminal activity, credit issue, etc.) taken by applicants, which may cause a disqualification from employment in law enforcement. Impersonal interaction and outreach can be an effective way to expose the applicant to organizational culture and establish a level of comfort with agency personnel.

State police agencies, like most other police agencies, have unique cultures and ways of operating (Perez and Moore Citation2012). Perhaps law enforcement agencies are ‘closed subcultures’ which operate based upon historical context and internal belief systems which may not always coincide with those outside of the culture. Some characteristics and standard ways of operation associated with state police agencies may be acceptable and understood by its members but seen as a detractor for those outside the agency. Some of these detractors may be the complexity of the applicant selection process (Donohue, Citation2020), agency image, opportunities for specialization, extreme discipline, residency requirements and paramilitary structure (Wilson and Grammich Citation2009). Certain organizational characteristics may disproportionally affect female and minority applicants (Donohue Citation2020; Wright Citation2009). But some of these characteristics can be amended to be more accommodating. For instance, participants in the semi-standardized focus group noted fear of relocation as an area of concern. A participant stated, ‘Making post assignments regionally would be really good’. Residency requirements may be an agency necessity because of work responsibilities, enhancing legitimacy (Tyler Citation2004) and community policing initiatives (Mutongwizo et al. Citation2021). However, agencies may employ a model which allows applicants to choose their work assignment or regional selection to diminish the detriment of residency requirements. This type of selective recruitment or filling positions based on need may be difficult to implement, but a viable option for addressing this issue. Some incumbents may object simply because this option was not available to them upon hire. Communication is key, and it is up to leadership at all levels to convince others of its utility. Changes such as these may require considerable planning but should not be as fiscally demanding as other strategies. Fiscal concerns impact recruitment in different ways, namely salary, benefits, and marketing.

While necessary, providing competitive compensation and incentives can be challenging for many state police agencies because of budgetary concerns. Some marketable incentives may include student loan repayment; sign-on bonuses; take home patrol cars; flexible work schedules (ICAP Citation2020) and other creative options. Pay raises may not be reasonable for state police agencies because of the issues associated with legislative bureaucracy and budget cycles. However, increases in this area should remain a viable employment option capable of competing with large metropolitan police departments. Marketing can also be fiscally challenging. We should view law enforcement agencies as a business whose product is customer service. So, it is important for state police agencies to acknowledge this and understand the quality of their product is contingent upon three things: 1) recruitment, 2) training, and 3) retention. Under performance in any of these areas may tarnish the brand of a law enforcement agency. Therefore, recruitment is vitally important, and agencies should allocate resources to ensure effective recruitment. While it may be cost prohibitive for many state police agencies, professional marketing firms may be useful in diversity recruiting. Professional marketing often involves specific targeting (i.e., micro-targeting) of applicant populations. For instance, it may prove useful to dissect the state based on racial and ethnic composition, then begin a targeted recruitment campaign specifically in areas which contain the desired demographic. A similar approach may be used to target groups or organizations which involve females or minorities, then specific efforts should be made to attract females and minorities by showcasing the diversification of officers already employed. Focus group participants specifically mentioned ‘Creating advertisement (flyers) featuring diversity’ or having ‘Pamphlets with different people on them to target certain audiences’. After locating and enticing a targeted applicant to apply for employment, barriers in the selection process may be a concern.

Agencies should concisely evaluate each component (i.e., cognitive assessment, physical fitness testing, and drug screening) of their selection process to determine whether easing or changing them can positively affect diverse populations. For instance, most agencies require applicants to complete a pre-employment cognitive assessment, physical fitness examination, and drug screen. Regarding cognitive assessment, agencies need to determine 1) Is our cognitive assessment reliable in accessing high-quality police applicants? and 2) Do certain groups of applicants perform worse than others and if so, why? If the response to either of these questions is affirmative, agencies need to examine and/or replace their cognitive assessment tool because it may be negatively affecting diversity recruitment. Concerning physical fitness testing, agencies should carefully review data collected to determine if their fitness standards allow proportional numbers of males and females through the selection process. If a disparity is determined, they should make modifications to the fitness assessment to correct any imbalances located involving the event type and/or evaluation criteria. Relating to drug screening, some agencies may operate under antiquated drug usage disqualification policies, which are too restrictive for current applicants. These policies should be examined to determine if they can make reasonable modifications to accommodate today’s police applicant without negatively affecting the agency. Any reasonable accommodations in policy to address cognitive assessment, physical fitness testing or drug screening should be carefully contemplated prior to implementation to avoid harming the agency or its traditions. While diversification is important, agencies should not take actions that may impair an agency’s ability to establish and maintain legitimacy.

Conclusion

In summation, we have presented many strategies to assist state police agencies in addressing a lack of diversity. However, it is incumbent upon each agency to employ these strategies and to act with a sense of urgency to correct any existing imbalances. A comprehensive approach should be taken by using all applicable strategies. Otherwise, as diversification remains stagnant, agencies may be subjected to mandated change orders as consent decrees.

The strategies identified in the focus groups, in no order of importance, were: 1) improving marketing; 2) interpersonal relationship development; 3) early cultivation of applicants; 4) guaranteed duty assignments; 5) diversity focused recruitment; 6) promoting retirement benefits; 7) promoting career specialization opportunities; and 8) promoting professionalism. There were also several additional strategies identified in the literature which may be useful in diversity recruiting, such as 1) prioritizing a diversification agenda; 2) leveraging agency resources; 3) addressing counterproductive organizational characteristics; improving salary and benefits packages; 4) removing barriers in the selection process; 5) employing micro-targeting strategies; 6) creating an accepting organizational subculture; and 7) showcasing agency diversity.

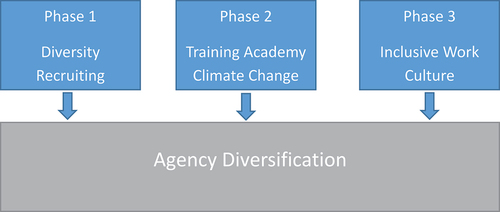

While not linked exclusively in the literature, conceivably the diversification of law enforcement agencies is an essential component of promoting police legitimacy (Tyler Citation2004). Without diversification, any progress made within law enforcement agencies towards legitimacy may be short-lived because of a lack of perspective and inclusion. However, without considerable focus being afforded to all three phases of a state police diversification model, beginning with recruitment, any net gains will probably be fleeting. Recommended next steps beyond recruitment should include specific criteria. We have created a diversification model to illustrate potential components ().

We can view a diversification model for state police agencies in three phases. Phase 1 is the establishment of a viable recruitment program. This paper provides a basis for improving diversity recruitment. Phase 2 involves creating a climate for success, growth, training, and matriculation within state police training academies, rather than a climate of attrition. Not all applicants are suitable for permanent status. However, those successful in completing the selection process and getting agency leadership approval have been deemed to be viable candidates. The focus of training academies should be to evaluate an applicant’s ability to complete necessary training. Further unnecessary vetting and hazing of the applicants is unwarranted, out of place, and may lead to high academy attrition rates, which may include the females and minorities recently recruited. Phase 3 involves creating a culture of inclusion within agencies which embraces diversity and equal opportunity. Agencies may not achieve and sustain diversification without considerable focus in each of these phases. Whether the focus is a willingness of citizens to cooperate under the principle of legitimacy (Tyler Citation2004) or organizational climate under the theory of underrepresented bureaucracy (Riccucci, et al., Citation2014), diversification is an important step. Further, agencies must work to ensure diversification efforts are not viewed as a zero-sum gain (Nowacki et al., Citation2021b) which threatens the history, traditions, or professionalism of the organization. Diversification should be seen as the pathway to efficiency, legitimacy, and sustained prosperity for state police agencies.

While the concept of conducting focus groups with agency personnel provided some useful information, we can consider it a limitation for this study. The thoughts and opinions of potential applicants may be a more valuable source of information (Cordner and Cordner Citation2011; Gibbs Citation2019). Therefore, we recommended that additional research be conducted with applicable applicant populations. In addition, the lack of knowledge about multiple coders is a limitation. The issue with this limitation is we could not verify any differences in asking questions and coding of the questions. While this is a limitation, we see this as a value because it provides objectivity in our analysis of the results. Future research should be conducted as a longitudinal study to assess the effect of agency diversification on citizens’ perception of police legitimacy. Ultimately, regardless of the geographic composition of a state or other factors, diversification is necessary and beneficial to state police agencies and it should be aggressively sought in the interest of legitimation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Archbold, C. A., and D. M. Schulz. 2012. “Research on Women in Policing: A Look at the Past, Present and Future.” Sociology Compass 6 (9): 694–706. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2012.00501.x.

- Britz, M. T. 1997. “The Police Subculture and Occupational Socialization: Exploring Individual and Demographic Characteristics.” American Journal of Criminal Justice 21 (2): 127–146. doi:10.1007/BF02887446.

- Brown, S. 2021. “Evaluating the Framing of Safety, Equity, and Policing: Responses to the Murder of George Floyd, Black Lives Matter, and Calls to Defund the Police.”

- Brown, J. 2022. “Lawsuit: No Pay for Commuting Wash. State Troopers is Unlawful.” The News Tribune. Retrieved from https://www.police1.com/patrol-cars/articles/lawsuit-no-pay-for-commuting-wash-state-troopers-is-unlawful-v3dzuelUNIguR1go/?utm_source=Police1&utm_campaign=907ad38c30-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2022_09_16_04_37&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_5584e6920b-907ad38c30-83418680

- Bureau of Justice Statistics [BJS]. (2021). Enforcement Drugs and Crime Facts. Department of Justice. Retrieved October 8, 2021, from https://bjs.ojp.gov/drugs-and-crime-facts/enforcement.

- Burns, R. G. 2014. “State Law Enforcement.” The Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice 1–3. Retrieved July 15, 2021, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781118517383.wbeccj051

- Census.gov. (2022). Retrieved June 8, 2022, from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/KY

- Chappell, A. T., and L. Lanza-Kaduce. 2010. “Police Academy Socialization: Understanding the Lessons Learned in a Paramilitary-Bureaucratic Organization.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 39 (2): 187–214. doi:10.1177/0891241609342230.

- Charkoudian, N., and M. J. Joyner. 2004. “Physiologic Considerations for Exercise Performance in Women.” Clinics in Chest Medicine 25 (2): 247–255. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2004.01.001.

- Cocke, C., J. Dawes, and R. M. Orr. 2016. “The Use of 2 Conditioning Programs and the Fitness Characteristics of Police Academy Cadets.” Journal of Athletic Training 51 (11): 887–896. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-51.8.06.

- Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies (CALEA®). 2017. Law Enforcement Standards Manual. 6th ed. Gainesville, VA: CALEA. https://www.calea.org/node/11406

- Community Oriented Policing Services [COPS]. 2009. Law enforcement recruitment toolkit. Washington, DC: COPS.

- Cordner, G., and A. Cordner. 2011. “Stuck on a Plateau?” Police Quarterly 14 (3): 207–226. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1098611111413990.

- Data USA. (2021). “Data USA: Police Officers.” Retrieved October 5, 2021, from https://datausa.io/profile/soc/police-officers#demographics

- Diaz, V. M., and L. E. Nuño. 2021. “Women and Policing: An Assessment of Factors Related to the Likelihood of Pursuing a Career as a Police Officer.” Police Quarterly 24 (4): 465–485. doi:10.1177/10986111211009048.

- DISA Global Solutions [DISA]. (2021). “Map of Marijuana Legality by State.” Retrieved June 9, 2022, from https://disa.com/map-of-marijuana-legality-by-state

- Donohue, R. H., Jr. 2020. “Shades of Blue: A Review of the Hiring, Recruitment, and Selection of Female and Minority Police Officers.” The Social Science Journal 58 (4): 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.soscij.2019.05.011.

- Fridell, L., R. Lunney, D. Diamond, B. Kubu, M. Scott, and C. Laing. 2001. “Racially Biased Policing: A Principled Response.” Washington. DC: Police Executive Research Forum. ISBN 1-878734-73-3.

- Gibbs, J. C. 2019. “Diversifying the Police Applicant Pool: Motivations of Women and Minority Candidates Seeking Police Employment.” Criminal Justice Studies 32 (3): 207–221. doi:10.1080/1478601X.2019.1579717.

- Griffin, J. D., and I. Y. Sun. 2018. “Do Work-Family Conflict and Resiliency Mediate Police Stress and Burnout: A Study of State Police Officers.” American Journal of Criminal Justice 43 (2): 354–370. doi:10.1007/s12103-017-9401-y.

- Hirschi, T. 1969. Causes of Delinquency. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Huey, L., and R. Ricciardelli. 2015. “‘This Isn’t What I Signed Up for’ When Police Officer Role Expectations Conflict with the Realities of General Duty Police Work in Remote Communities.” International Journal of Police Science & Management 17 (3): 194–203. doi:10.1177/1461355715603590.

- International Association of Chiefs of Police [IACP]. (2007). A symbol of fairness and neutrality. www.theiacp.org/portals/0/pdfs/ASymbolofFairnessandNeutrality.pdf

- International Association of Chiefs of Police [IACP]. (2020). The State of Recruitment: A Crisis for Law Enforcement. https://www.theiacp.org/sites/default/files/239416_IACP_RecruitmentBR_HR_0.pdf

- Koper, C. S., E. R. Maguire, G. E. Moore, and D. E. Huffer. 2001. Hiring and Retention Issues in Police Agencies: Readings on the Determinants of Police Strength, Hiring and Retention of Officers, and the Federal COPS Program. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

- Krueger, R. A. 2014. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. Thousand Oaks California: Sage publications.

- Langham, B. n.d. “Millennials and Improving Recruitment in Law Enforcement.” Police Chief. https://www.policechiefmagazine.org/millennials-and-improving-recruitment/

- Langton, L. 2010. Women in Law Enforcement, 1987-2008. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- Lasley, J. R., J. Larson, C. Kelso, and G. C. Brown. 2011. “Assessing the Long-Term Effects of Officer Race on Police Attitudes Towards the Community: A Case for Representative Bureaucracy Theory.” Police Practice & Research 12 (6): 474–491. doi:10.1080/15614263.2011.589567.

- Maguire, E. R. 2003. Organizational Structure in American Police Agencies: Context, Complexity, and Control. Albany, New York, United States: SUNY Press.

- Manolatos, T. 2006, “S.D. Cops Flee City’s Fiscal Mess, Seek Jobs at Other Departments,” San Diego Union-Tribune, July 5, 2006. As of July 5, 2006: http://legacy.signonsandiego.com/news/metro/20060705-9999-1n5gary.html

- McDevitt, J., A. Farrell, and R. Wolf. 2008. Promoting Cooperative Strategies to Reduce Racial Profiling. Washington, D.C.: US Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

- McMullen, S. M., and J. Gibbs. 2019. “Tattoos in Policing: A Survey of State Police Policies.” Policing: An International Journal 42 (3): 408–420. doi:10.1108/PIJPSM-05-2018-0067.

- Mid-south State Police (MSP). (2021). Mid-south State Police Headquarters.

- Mutongwizo, T., C. Holley, C. D. Shearing, and N. P. Simpson. 2021. “Resilience Policing: An Emerging Response to Shifting Harm Landscapes and Reshaping Community Policing.” Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 15 (1): 606–621. doi:10.1093/police/paz033.

- Nowacki, J., J. A. Schafer, and J. Hibdon. 2021a. “Workforce Diversity in Police Hiring: The Influence of Organizational Characteristics.” Justice Evaluation Journal 4 (1): 48–67. doi:10.1080/24751979.2020.1759379.

- Nowacki, J., J. Schafer, and J. Hibdon. 2021b. “Gender Diversification in Police Agencies: Is It a Zero-Sum Game?” Policing: An International Journal 44 (6): 1077–1092. doi:10.1108/PIJPSM-02-2021-0033.

- Orrick, W. D., and P. S. Director 2008. “Recruitment, Retention, and Turnover of Law Enforcement Personnel.”

- Peak, K., and W. Sousa. 2022. Policing in America. Upper Saddle River: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

- Perez, D. W., and J. A. Moore. 2012. Police Ethics. Canada: Cengage Learning Canada Inc.

- PEW. (2021). “Percentage of Women in State Policing Has Stalled Since 2000.” Retrieved June 10, 2022, from https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2021/10/20/percentage-of-women-in-state-policing-has-stalled-since-2000

- Reaves, B. A. 2012. “Hiring and Retention of State and Local Law Enforcement Officers, 2008–Statistical Tables.” Bureau of Justice Statistics (BOJ).

- Reaves, B. A. 2015. “Local Police Departments, 2013: Personnel, Policies, and Practices.” NCJ 248677: 1–21.

- Riccucci, N. M., G. G. Van Ryzin, and C. F. Lavena. 2014. “Representative Bureaucracy in Policing: Does It Increase Perceived Legitimacy?.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 24 (3): 537–551.

- Rigaux, C., and J. B. Cunningham. 2021. “Enhancing Recruitment and Retention of Visible Minority Police Officers in Canadian Policing Agencies.” Policing and Society 31 (4): 454–482. doi:10.1080/10439463.2020.1750611.

- Rowe, M., and J. I. Ross. 2015. “Comparing the Recruitment of Ethnic and Racial Minorities in Police Departments in England and Wales with the USA.” Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 9 (1): 26–35. doi:10.1093/police/pau060.

- Skoy, E. 2021. “Black Lives Matter Protests, Fatal Police Interactions, and Crime.” Contemporary Economic Policy 39 (2): 280–291. doi:10.1111/coep.12508.

- Todak, N. 2017. “The Decision to Become a Police Officer in a Legitimacy Crisis.” Women & criminal justice 27 (4): 250–270. doi:10.1080/08974454.2016.1256804.

- Tyler, T. R. 2004. “Enhancing Police Legitimacy.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 593 (1): 84–99. doi:10.1177/0002716203262627.

- Tyler, T. R. 2021. “Procedural Justice, Legitimacy, and Compliance.” In Why People Obey the Law (pp. 3–7). Princeton university press.

- Tyler, T., and C. Fischer 2014, March). “Legitimacy and Procedural Justice: A New Element of Police Leadership.” Police Executive Research Forum.

- USA facts.org. (2020). “Police Departments in the US: Explained.” Retrieve June 9, 2022, from https://usafacts.org/articles/police-departments-explained/

- Villeda, M., R. McCamey, E. Essien, and C. Amadi. 2019. “Use of Social Networking Sites for Recruiting and Selecting in the Hiring Process.” International Business Research 12 (3): 66–78. doi:10.5539/ibr.v12n3p66.

- Weber, M. 1978. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. Vol. 1. Oakland, California: Univ of California Press.

- Whetstone, T. S., J. C. Reed Jr, and P. C. Turner. 2006. “Recruiting: A Comparative Study of the Recruiting Practices of State Police Agencies.” International Journal of Police Science & Management 8 (1): 52–66. doi:10.1350/ijps.2006.8.1.52.

- White, M. D., and G. Escobar. 2008. “Making Good Cops in the Twenty-First Century: Emerging Issues for the Effective Recruitment, Selection and Training of Police in the United States and Abroad.” International Review of Law, Computers & Technology 22 (1–2): 119–134. doi:10.1080/13600860801925045.

- Williams, F. A., Jr, and G. E. Higgins. 2022. “Physical Fitness Standards: An Assessment of Potential Disparate Impact for Female State Police Applicants.” International Journal of Police Science & Management 24 (3): 250–260.

- Wilmore, J. H. 1979. “The Application of Science to Sport: Physiological Profiles of Male and Female Athletes.” Canadian journal of applied sport sciences Journal canadien des sciences appliquees au sport 4 (2): 103–115.

- Wilson, J. M., E. Dalton, C. Scheer, and C. A. Grammich. 2010. Police Recruitment and Retention for the New Millennium, 10. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Wilson, J. M., and C. A. Grammich 2009, July. Police Recruitment and Retention in the Contemporary Urban Environment. In Conference Proceedings. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Wilson, J. M., and C. A. Grammich. 2022. “Staffing Composition in Large, US Police Departments: Benchmarking Workforce Diversity.” Policing: An International Journal 45 (5): 707–726. ahead-of-print. doi:10.1108/PIJPSM-12-2021-0175.

- Wright, J. 2009. “Adding to Police Ranks Rankles.” Memphis Commercial Appeal 1.

- Zippia. (2022). “Zippia the Career Expert.” Retrieved June 8, 2022, from https://www.zippia.com/state-trooper-jobs/demographics/