ABSTRACT

This study examines the association between number of siblings and delinquency, adjusting for family relations and demographic variables. Data is based on a nationally representative school survey in Sweden consisting of approximately 25,000 youths. The results show a positive association for those having five or more siblings (IRR = 1.533, p = < .001), whereas one or two siblings is negatively associated with delinquency compared to those having no siblings. These results remain stable after adjusting for family relations. This study underscores the importance of further exploring the variation and direction of the association between the number of siblings and delinquency, as well as deepening our understanding of the various theoretical mechanisms through which the number of siblings is associated with delinquent behaviour.

Introduction

The number of siblings is considered an important factor in criminological theory, with the assumption that children from larger families, characterised by a greater number of siblings, are more prone to engage in delinquent behaviour compared to those from smaller families. Despite empirical support for this found by several studies, the association is often observed to be relatively weak. However, unlike other aspects of family dynamics such as parental monitoring, family relationships, and support, which have received more research attention (Hoeve et al. Citation2009, Citation2012; Kroese et al. Citation2021; Nilsson Citation2017; Racz and McMahon Citation2011; Svensson and Johnson Citation2022), number of siblings or family size has typically been treated as a secondary variable rather than the primary focus of study (e.g., Amato and Fowler Citation2022; Argys et al. Citation2006).

How and why the number of siblings is associated with delinquency have been discussed within a number of theoretical frameworks (Brownfield and Sorenson Citation1994; Collier and Mears Citation2022). One of the most discussed frameworks falls within social control theory, often focusing on family variables, such as parental monitoring and attachment to parents. While several studies discuss social control concepts to enhance our understanding of the relationship between the number of siblings and delinquency, only a limited few have conducted empirical tests to validate the assumptions of the theory (e.g., Brownfield and Sorenson Citation1994; Collier Citation2020; Sampson and Laub Citation1994).

Furthermore, most previous studies have examined the association between the number of siblings and delinquency using linear models. Such models anticipate a consistent change in delinquency with each additional sibling, overlooking the possibility that the relationship may be more complex.

The relationship between the number of siblings and delinquency has not received much attention since early studies were undertaken within the field. To gain a deeper understanding of the nature of this relationship, more research is needed. Against this background, the present study will further examine this association and expand upon previous research.

Background

Empirical research indicates that the association between the number of siblings and the development of delinquent behaviour in youth remains uncertain in terms of direction and causal impact. While some studies have identified a positive association (Farrington Citation1987, Citation2011; Farrington, Ttofi, and Piquero Citation2016; Fischer Citation1984; Mercer et al. Citation2016; Murray and Farrington Citation2010; Sampson and Laub Citation1994), other studies have found a negative association, or no significant effects (Argys et al. Citation2006; Brownfield and Sorenson Citation1994; Heck and Walsh Citation2000; Muola, Ndung’u, and Fredrick Citation2009; Touliatos and Lindholm Citation1980).

These studies do, however, differ in a range of aspects, which makes comparisons difficult. In some studies, the number of siblings is not the main focus, but only included as a control variable (e.g., Amato and Fowler Citation2022; Argys et al. Citation2006; Mercer et al. Citation2016). Investigating the number of siblings solely as a control variable poses a limitation, as it may oversimplify the complexity of family dynamics. Furthermore, the studies use different samples, including males only (e.g., Farrington, Ttofi, and Piquero Citation2016; Heck and Walsh Citation2000; Sampson and Laub Citation1994), known offenders (Heck and Walsh Citation2000), or children from rehabilitation homes (Muola, Ndung’u, and Fredrick Citation2009), making it challenging to generalize finding across broader populations.

Additionally, while some studies use official measures of delinquency (e.g., Farrington, Ttofi, and Piquero Citation2016; Mercer et al. Citation2016), others rely on self-reported delinquency measures (e.g., Brownfield and Sorenson Citation1994; Heck and Walsh Citation2000; Touliatos and Lindholm Citation1980). Although studies relying on self-reported offending are more likely to capture delinquent behavior, those employing self-reported delinquency measure vary considerably in terms of the reported number and types of delinquent acts. The differences in measurements, combined with the fact that many of these studies have relied on small, non-representative samples, restrict the generalizability of their findings, leaving us with less accurate comparisons of the estimated effects.

The limitations in measuring siblings, as identified by Collier (Citation2020), involve, among other things, that some studies do not distinguish between siblings residing within and outside the household. This may have implications for the results, as non-resident siblings may not be directly related to the immediate family setting. Furthermore, even though some studies use a continuous measure for the number of siblings (e.g., Argys et al. Citation2006; Collier and Mears Citation2022; Sampson and Laub Citation1994), a considerable number of studies have used a rough, dichotomized measure, categorizing the number of siblings as either large or small family size (e.g., Heck and Walsh Citation2000). Such an approach may result in loss of important, risk-relevant information and hide potential non-linearities in the relationship between number of siblings and delinquency (Collier and Mears Citation2022).

Consequently, most studies thus far have assumed a linear relationship between the number of siblings and delinquency (e.g., Brownfield and Sorenson Citation1994; Lauritsen Citation1993; Mercer et al. Citation2016; Sampson and Laub Citation1994), usually finding fairly modest effect sizes. However, there are valid reasons to expect that the association between the number of siblings and delinquency is nonlinear. For example, studies outside the field of criminology have found evidence that the number of siblings has a nonlinear association with adolescent outcomes, such as educational achievement (Mogstad and Wiswall Citation2016) and mental health (Downey and Cao Citation2023). Furthermore, recent criminological research by Collier (Citation2020) suggests that the association between the number of siblings and delinquency does not follow a simple and consistent pattern. Instead, the relationship between these variables may exhibit fluctuations or change in direction as the number of siblings increases. However, several datasets are examined in this study, and results are inconsistent across them (Collier Citation2020).

From a theoretical perspective, the relationship between number of siblings and delinquency has often been examined from the viewpoint of social control theory, which places primary emphasis on understanding the socialisation process within families. Social control theories explain why people abstain from crime, rather than why individuals engage in crime, and argue that delinquent behaviour is limited by controls, and when controls are absent or diminish, the risk of committing crime increases (Hirschi Citation1969). It is generally assumed that family dynamics may vary qualitatively based on the number of children in a family, given that the availability of parental resources is believed to diminish as the number of siblings increases. For instance, it is argued that the extent of direct forms of control, such as parental monitoring and supervision, as well as indirect forms of control, such as parent–child attachment, may decline in larger families. Consequently, this decline in controls is suggested to increase the likelihood of engaging in delinquent behaviour (Collier and Mears Citation2022; Sampson and Laub Citation1994; Tygart Citation1991). Based on this, family process variables are likely to play an important role in mediating the effects of the number of siblings on delinquent behavior. Including factors such as parental monitoring and attachment to parents into the analysis would likely reduce the association between the number of siblings and delinquency.

Even though the logic derived from social control theory is commonly used, there is a lack of studies that empirically examine these arguments. Only a few previous studies have examined the association between the number of siblings and delinquency, adjusting for social control variables, and the results presented are somewhat contradictory. For instance, Tygart (Citation1991) found that a greater number of siblings predicts less parental control, which in turn leads to greater antisocial peer influences and, consequently, result in a higher likelihood of delinquency. In a similar vein, Sampson and Laub (Citation1994) found that social control processes within the family, such as supervision, harsh discipline, and parent–child attachment, operate through the family size-delinquency relationship. Their findings suggest that children in large families experience lower levels of social control compared to children from small families, which in turn increase their risk of delinquency. In contrast, Brownfield and Sorenson (Citation1994) did not find any support for social control theory, since the relationship between the number of siblings and delinquency is, to a large extent, explained by delinquent siblings, and argue that their findings are rather in line with social learning theory. Furthermore, studies have also found that children with two siblings experience higher levels of parental attachment, and reduced likelihood of delinquency, compared to children in one-child households (Collier Citation2020), which contrasts with the notions of social control theory.

Overall, these contradictory theoretical findings underscore the need for additional studies that explore the relationship between social control variables, the number of siblings, and delinquency. Additionally, findings also imply that it is not solely negative effects that can be anticipated from the number of siblings but also positive. For example, having multiple siblings may serve as a protective factor, as older siblings in larger families may assume parental roles and responsibilities in raising their younger siblings (Hirschi Citation1969). Within other fields, previous research has found that siblings can have a range of positive influences on factors such as well-being (Chen, Chen, and Wang Citation2021) and social skills (Downey, Condron, and Yucel Citation2015). However, when examining these associations, it is important to also consider the quality of the relationship between siblings (Jensen et al. Citation2023; Yucel and Downey Citation2015). While some sibling relationships have shown to provide comfort and promote healthy behaviours, other sibling relationships are more tension-filled, which has implications for various outcomes (Yucel and Downey Citation2015).

Sweden as a context

Most previous studies have been conducted in the United States. Thus, it is of importance to conduct research in other settings as well. An interesting context for family-related research is Sweden, as it is often seen as a forerunner in family demographic change (Ohlsson-Wijk, Turunen, and Andersson Citation2020). In Sweden, along with other Western industrialised nations, the concept of family has undergone significant transformations in recent decades. One notable change is the increased prevalence of family instability. Although the traditional model of a two-parent household with two children remains common, there has been a rise in split-family households (Andersson and Kolk Citation2015). Additionally, the substantial influx of immigrants in Sweden over the past years has also influenced family size patterns, resulting in rapid shifts in the country’s demographic composition and family dynamics (Carlsson Citation2022).

Nevertheless, the cultural perception of an ideal family size in Sweden often revolves around having two children. Cultural perceptions about ideal family size are important in this context because they may lead to heightened parental investment in children and greater societal support for families that conform to this presumed ideal size. Conversely, families with fewer or more than two children may receive comparatively less support (Hagawen and Morgan Citation2005; Sobotka and Beaujouan Citation2014).

This study

Against this background, we argue that the relationship between the number of siblings and delinquency is unclear and needs additional attention. The present study will improve upon problems identified in previous studies and address some of these limitations by incorporating a representative sample, examining the significance of social control variables, and exploring more nuanced models to better understand the relationship between the number of siblings in a household and delinquency. Using a large, pooled, nationally representative sample of Swedish youth, the aim of this study is to, in detail, further explore the relationship between the number of siblings and delinquency.

The present study has two overall research questions: (1) Does the number of siblings relate to delinquency, and is there evidence of a nonlinear association? (2) Does the association change when adjusting for two central family socialisation variables, parental monitoring and attachment, as well as key demographic factors including family structure and immigrant background?

Data and method

Participants

This study is based on four waves of a cross-sectional, nationally representative school survey of adolescents in year nine of compulsory education, age 15 on average, conducted by the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention between 2003 and 2011. All of the surveys are based on systematic samples of schools with year-nine classes. The data were primarily collected in December. The principal of each school distributed the questionnaires along with information about the study to teachers, and students completed the questionnaires during lesson time in the presence of the teacher. The surveys included a total of 6,692 adolescents in 2003; 7,449 adolescents in 2005; 6,893 in 2008; and 6,490 in 2011. In these surveys, the non-response rate was calculated in relation to the respondents in the participating classes and amounted to 14% in 2003, 14% in 2005, 19% in 2008, and 15% in 2011. The four subsamples combined give a total sample of 27,524 adolescents. Following list-wise deletion of missing values, the following analyses are based on 25,132 cases.

Measures

Dependent variable

Self-reported delinquency is based on an overall measure of 20 items on criminal offending during the past 12 months covering, for example, violence, theft, and vandalism. For detailed information of the items, see Appendix . We will be using a variety scale that includes all 20 items from the survey, and which measures how many different types of offenses the youths report having committed. The variety scale is seen as the most appropriate measure of delinquency and in general it has higher reliability and validity than frequency measures (Bendixen, Endresen, and Olweus Citation2003; Sweeten Citation2012). The variety scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of .86. In some analyses, we also present measures of prevalence for overall delinquency (0 = no act/1 = one or more acts), violence (0 = no act/1 = one or more acts), and serious theft (0 = no act/1 = one or more acts).

Independent variables

Number of siblings is measured on the basis of an overall measure of the number of siblings the respondent is living with. This measure is based on the combination of two items: (1) number of brothers, and (2) number of sisters. This measure is coded as living with 0 siblings/1 sibling/2 siblings/3 siblings/4 siblings/5 or more siblings. A total of 22.5% have no siblings, 40.5% have one sibling, 24.6 % have two siblings, 7.9% have three siblings, 2.7% have four siblings and, 1.8% have five or more siblings. The number of siblings is included in the analyses as a dummy variable using the category ‘living with zero siblings’ as a reference category. Most previous studies have used a frequency scale of the number of siblings (e.g., Collier and Mears Citation2022; Sampson and Laub Citation1994) whereas some have used dummies (e.g., Heck and Walsh Citation2000). For our main analysis, we decided to use the dummy coded version of number of siblings as this will make the results clear so as to identify differences between the groups. However, we also performed analysis using a frequency scale of the number of siblings (presented in , Appendix).

Family relations

We use two measures of family relations. Attachment to parents is a mean index based on four items: (1) Do you think that you usually get on well with your mum? (2) Do you think that you usually get on well with your dad? (response alternatives: never/not often/often/most of the time/always) (3) Can you usually talk about anything at all (e.g., problems) with your mum? (4) Can you usually talk about anything at all (e.g., problems) with your dad? (response alternatives: definitely not/not much/maybe (it depends)/probably/yes, definitely). The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale is .76. High scores on this scale indicate strong emotional bonds to parents. Parental monitoring is an additive index based on two items: (1) Do you have to be home by a certain time on the weekends? (2) Do your parents demand that you tell them in advance what you are going to be doing if you want to go out on e.g., a Friday night? (response alternatives: no, never/rarely/sometimes/often/yes, always). The Spearman’s coefficient for these two items is 0.44. High scores on the index suggest that respondents experience strong parental supervision.

Five demographic variables are included in the regression models. Gender is coded as 0 for girls and 1 for boys. Immigrant background is coded as (1) Born in Sweden to two Swedish-born parents: Native Swedish, i.e., no immigrant background; (2) Born in Sweden to one Swedish-born and one foreign-born parent: second generation mixed; (3) Born in Sweden to two foreign-born parents: second generation; (4) Born abroad: first generation. Immigrant background is included in the analyses as dummy variables using category (1) ‘Born in Sweden to two Swedish-born parents’ as reference category. Parental employment status is a measure of whether the mother and the father are employed. The variable is coded as 0 if both of the parents are employed and 1 if either the mother or the father or both are, for example, not employed, seeking work, or receiving disability pension or early retirement benefits. Split family is coded as 0 if the respondent is living with both biological parents and 1 if this is not the case. These variables are included in the study because previous research has found them to be associated with delinquent behaviour (e.g., Knaappila et al. Citation2019; Kroese et al. Citation2021; Pierce and Jones Citation2022; Svensson and Shannon Citation2021; Vasiljevic et al. Citation2023). They are assumed to be weakly associated with delinquency when family relation variables are included in the analysis.

Year of study represents the year when the study was conducted and is included in the form of dummy variables (year 2005, 2008, 2011) using 2005 as the reference category in the analyses.

Analytical strategy

First, we compared differences between the number of siblings in regard to the different variables using one-way analysis of variance and chi-square test. Second, we performed a number of negative binomial regression models using our delinquency variety scale as outcome. Negative binomial regression was used because our outcome is a skewed count variable with overdispersion (Cameron and Trivedi Citation1998; Hilbe Citation2011). The modelling was estimated in three stages. First, we examined whether there is an association between the number of siblings and delinquency. Second, we included our demographic variables, i.e., gender, immigrant background, split family, and not in employment. Third, we included our two family relations variables, i.e., attachment to parents and parental monitoring. In the regression analyses, having no siblings is used as a reference category. All models adjust for year of study. As the data are based on respondents clustered in schools, standard errors clustered at school level are presented. We present the regression coefficients as relative risk estimates of incidence rate ratio (IRR). In order to illustrate the modelling, the regression estimates were plotted with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (using the coefplot in Stata) (Jann Citation2014). To examine whether the association between the different sibling groups and delinquency are different between Model 2 and Model 3, we estimated a cross-model test using the suest command in Stata (Clogg, Petkova, and Haritou Citation1995; Mize, Doan, and Long Citation2019; Weesie Citation1999). Interval-scaled predictors were standardised prior to inclusion in the regression models. All statistical analyses were conducted in Stata version 17.

Results

presents differences between the number of siblings in relation to the outcome and the independent variables. The results show that youth having five or more siblings reported a higher level of delinquency than the other groups. We also found those having no siblings reported higher levels of delinquency than those having one and two siblings. Furthermore, shows that as the number of siblings increases, the proportion of respondents with a native background decreases, while the proportion of respondents with an immigrant background increases. Additionally, single-child households are more frequently found in split families. Finally, the results in the table show only a few significant differences between the number of siblings groups in relation to attachment to parents and parental monitoring. The respondents with no siblings reported significantly lower levels of attachment to parents compared to those having one sibling. In addition, children with no siblings reported significantly lower levels of parental monitoring in relation to those having one and two siblings.

Table 1. Description of number of siblings groups (means/%).

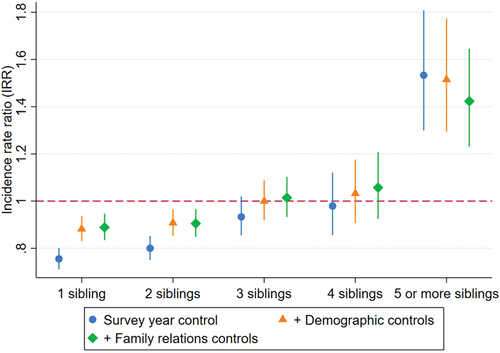

presents the IRR for Model 1 (only year of study included), Model 2 (demographic variables added), and Model 3 (family relations variables added) for the total sample. The results for the first model show that having one (IRR = .755, p = < .001) or two (IRR = .800, p = < .001) siblings is significantly negatively associated with delinquency in relation to having no siblings. No significant association was found for those having three or four siblings. For those reporting having five or more siblings, there is a significant positive association with delinquency (IRR = 1.533, p = < .001). The association between the number of siblings and delinquency shows no large differences when including the demographic variables in Model 2. Finally, in Model 3 the results are presented when adding attachment to parents and parental monitoring. The results show the same pattern as the second model, i.e., having one or two siblings is still significantly negatively associated with delinquency (IRR = .889, p = < .001 vs. IRR = .905, p = .002). Having five or more siblings shows a positive association (IRR = 1.423, p = < .001) with delinquency.

Table 2. The association between delinquency variety and number of siblings, full sample.

To examine our second research question, a cross-model test was estimated to examine whether there are any significant differences between Model 2 and Model 3. The results show no significant differences between the number of siblings when control is held for attachment to parents and parental monitoring. For an illustration of the findings presented in the table, see .

Figure 1. Association between number of siblings (ref: no siblings) and delinquency variety. IRR estimates presented with 95% CI 95. Negative binomial regression analysis.

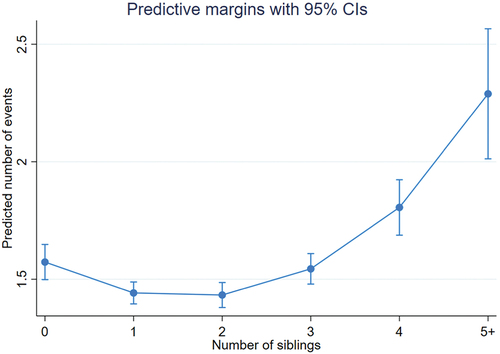

In addition, we also performed the regression model including the number of sibling measure as a frequency measure. In the final model, the results show a weak positive association between the number of siblings and delinquency (IRR = 1.027, p = < .007). This gives support for including our dummy variables to examine the nonlinear association.

The results presented indicate the association to be nonlinear. According to this, we also performed Model 3 including a squared term of the number of siblings. The results show a clear nonlinear trend of the association between the number of siblings and delinquency (see Appendix ).

Sensitivity analyses

We also performed a sensitivity analysis, and estimated models using logistic regression estimating average marginal effects (AME) for prevalence of violence and serious theft as outcomes ( and A3 Appendix).Footnote1 The findings are fairly stable over these outcomes.

The results show that having one and two siblings are both negatively associated with violence compared to those having no sibling. Having one sibling is negatively associated with serious theft compared to those with no siblings. For both violence and serious theft, having five or more siblings has the strongest association with the outcomes.

Discussion

The present study investigates the relationship between the number of siblings and delinquency. Previous studies have suggested that larger family size may increase the risk of delinquent behaviour, but findings have been inconsistent. This study addresses some limitations in previous research by using a large representative sample of Swedish youth.

The findings in this study show that having one or two siblings may have a protective effect against delinquent behaviour, while no association was found for youths with three or four siblings. However, after a certain threshold, such as five or more siblings, youths report higher levels of delinquency compared to other groups. Additionally, youths with no siblings show higher delinquency levels than those with one or two siblings. The findings remained stable after adjusting for parental monitoring and attachment as well as demographic variables. These results indicate a clear nonlinear result, suggesting that the association between the number of siblings and delinquency is neither simple nor consistent. These findings support previous research suggesting that the association between family size and delinquency can vary in different directions as the number of siblings increases (Collier and Mears Citation2022).

The findings indicate that the number of siblings becomes criminogenic primarily when it reaches higher numbers, suggesting that youths with a larger number of siblings (five or more) may exhibit increased susceptibility to engaging in criminal behaviour. In families with many children, available resources, such as parental time and attention, may be stretched thin. Consequently, this could lead to reduced parental supervision and increased exposure to negative peer influences. While parental monitoring, attachment to parents, and the demographic variables included are important factors to consider, the results in this study suggest that they may not fully capture the underlying mechanisms by which the number of siblings influences delinquency. The relationship between the number of siblings and delinquency is likely influenced by a combination of individual differences (e.g., self-control and moral values), sibling dynamics, parental capacity, and external environmental factors. Unraveling the complexity of these interactions would require a more nuanced exploration that goes beyond the factors used in this study.

With the exception of youths who have a large number of siblings, our study findings suggest that siblings may have a positive impact on the development of prosocial behavior. Previous research has demonstrated that sibling relationships play a significant role in promoting healthy development and overall well-being (Chen, Chen, and Wang Citation2021; Killoren et al. Citation2015; LeBouef and Dworkin Citation2021). These relationships can provide vital support and compensate for inadequate parenting or strained parent–child relationships in certain cases (Borchet et al. Citation2020; Milevsky Citation2022). However, as the number of siblings increases, the protective effect of having siblings appears to diminish, eventually reaching a tipping point at five children. At this tipping point, the advantages associated with having siblings transform into disadvantages in terms of the increased risk for delinquency. Our results differ from those found by Collier and Mears (Citation2022), who did not find any conclusive thresholds effects. However, it is unlikely that there is a universal tipping point or specific numerical threshold that universally applies to the impact of the number of siblings on delinquency. The relationship between the number of siblings and adverse outcomes is influenced by various factors, including cultural and contextual variables (Björklund, Ginther, and Sundström Citation2007; Downey and Cao Citation2023).

Sweden, which stands out as having one of the most comprehensive social safety nets supporting families, ranks relatively low in terms of intergenerational solidarity compared to other Western countries and has one of the lowest rates of three-generational households in Europe (Georgas et al. Citation2006). Speculatively, this suggests that kin networks may be less developed within larger families in Sweden, potentially resulting in limited support for children. Subsequently, this could increase the risk for risky behaviours, including delinquency.

The findings of this study also indicate that individuals without any siblings have a higher risk of engaging in delinquent behaviour compared to those with one or two siblings. Previous research suggests that the advantages associated with growing up with siblings may outweigh the benefits of being an only child, receiving undivided attention (Jensen et al. Citation2023). Several factors may contribute to the increased risk among only children, including decreased socialisation opportunities due to limited exposure to positive sibling influences, and potentially inadequate parental supervision.

Furthermore, studies have indicated that only children tend to exhibit lower levels of self-control, poorer interpersonal skills, and a higher likelihood of externalizing problem behaviours compared to children with at least one sibling (Downey, Condron, and Yucel Citation2015). Most studies on only children have primarily concentrated on educational outcomes (e.g., Blake Citation1989; Downey Citation1995, Citation2001). It is, however, worth noting that research specifically focused on only children, particularly within the field of criminology, is limited. One study, however, found that individuals without siblings exhibited a higher risk of offending than those with non-offending siblings, suggesting that having non-offending siblings may act as a protective factor (Beijers et al. Citation2017).

Interesting to note, our descriptive data reveal that one-child households are more often split compared to households with one or more siblings, which may contribute to a higher susceptibility to delinquent behaviors among youths with no siblings. Previous research has found that family structure plays an important role in shaping individual outcomes (Cookston Citation1999; Svensson Citation2003; Vasiljevic, Svensson, and Shannon Citation2021).

Limitations

Several limitations need to be acknowledged in this study. Firstly, there is a limitation when it comes to contextual details. Some measures are relatively limited, and the study does not encompass a wide range of sibling- and family-related factors that could potentially influence the association between the number of siblings and delinquency. Consequently, important details that could be of significance in understanding the complexities of family dynamics might be overlooked. Families are intricate systems, and considering factors such as sibling constellations and relatedness (e.g., biological, half-siblings, or step-siblings), birth order, and age spacing is crucial as they have been shown to play a role in the association between the number of siblings and delinquency. Notably, research has highlighted the risk associated with having an older brother (Ardelt and Day, Citation2002) and the potential protective effects, particularly in certain groups, of having a sister (Killoren et al. Citation2015).

The study also lacks information regarding diverse family arrangements beyond whether adolescents live with both biological parents or not. Previous research has shown that adolescents in asymmetrical family arrangements, where either the mother or the father (but not both) has a new partner, tend to report higher levels of delinquency (Svensson and Johnson Citation2022). Additionally, studies indicate that children living in complex family structures with half- or step-siblings face a higher risk of negative life outcomes compared to those in family structures with only full biological siblings (Fomby and Osbourne Citation2017; Manning, Brown, and Stykes Citation2014).

Secondly, the study does not examine central, theoretical, individual-level indicators such as self-control (Gottfredson and Hirschi Citation1990) and moral values (Wikström et al. Citation2012). Individuals differ in their individual characteristics, and these characteristics can have a significant impact on behavior. The influence of the number of siblings on individuals may vary based on their levels of self-control and moral values. These need to be considered in further research.

Finally, the results in this study are based on several cross-sectional datasets. Despite the study being based on a large, nationally representative sample, it is not possible to draw conclusions about causal relationships. It might be valuable for further research to use data based on longitudinal design to be able to examine the time order of events and establish causality.

Despite these limitations, we argue that the main contribution of this study lies in its detailed examination of family size. The result of the present paper strengthens the notion that the magnitude and the direction of the number of siblings needs additional attention. Additionally, we also need to deepen the understanding of the theoretical mechanisms through which the number of siblings is associated with delinquent behaviour. To conclude, it is important to move away from simplistic models on the relationship between the number of siblings and delinquency and include more complex, and theoretically-based, measures to enhance understanding of this relationship.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eva-Lotta Nilsson

Eva-Lotta Nilsson, Ph.D., is a researcher at the Department of Criminology at Malmö university, Sweden, where she also received her PhD. Her research interests center mainly around adolescent delinquency, with a special focus on family socialization processes.

Zoran Vasiljevic

Zoran Vasiljevic is a senior lecturer at the Department of Criminology at Malmö University, Sweden. He received his PhD in Criminology from Malmö University. His research interests cover a range of topics within crime and deviance, such as crime trends, segregation, and immigration and crime.

Robert Svensson

Robert Svensson is Professor at the Department of Criminology at Malmö University, Sweden. He received his PhD in Sociology from Stockholm University. His research interests span a range of topics in the field of crime and deviance, with a special focus on crime and deviance among adolescents.

Notes

1. Measure of violence includes the following items: carried a knife as a weapon; threated someone; assault; injured someone with a weapon. Measure of serious theft includes the following items: stolen a bicycle; moped/motorcycle; car theft; theft from car; stealing from pocket; snatched a bag.

References

- Amato, P. R., and F. Fowler. 2022. “Parenting Practices, Child Adjustment, and Family Diversity.” Journal of Marriage and Family 64 (3): 703–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00703.x.

- Andersson, G., and M. Kolk. 2015. “Trends in Childbearing, Marriage and Divorce in Sweden: An Update with Data Up to 2012.” Finnish Yearbook of Population Research 50:53–70. https://doi.org/10.23979/fypr.52483.

- Ardelt, M., and L. Day. 2002. “Parents, Siblings, and Peers: Close Social Relationships and Adolescent Deviance.” The Journal of Early Adolescence 22 (3): 310–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/02731602022003004.

- Argys, L. M., D. I. Rees, S. L. Averett, and B. Witoonchart. 2006. “Birth Order and Risky Adolescent Behavior.” Economic Inquiry 44 (2): 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1093/ei/cbj011.

- Beijers, J., C. Bijleveld, S. van de Weijer, and A. Liefbroer. 2017. “All in the family?” the Relationship Between Sibling Offending and Offending Risk.” Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology 3 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-017-0053-x.

- Bendixen, M., I. M. Endresen, and D. Olweus. 2003. “Variety and Frequency Scales of Antisocial Involvement: Which One Is Better?” Legal and Criminological Psychology 8 (2): 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532503322362924.

- Björklund, A., D. K. Ginther, and M. Sundström. 2007. “Family Structure and Child Outcomes in the United States and Sweden.” Journal of Population Economics 20 (1): 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-006-0094-7.

- Blake, J. 1989. Family Size and Achievement. Vol. 3. Berkely: University of California Press.

- Borchet, J., A. Lewandowska-Walter, P. Połomski, A. Peplińska, and L. M. Hooper. 2020. “We Are in This Together: Retrospective Parentification, Sibling Relationships, and Self-Esteem.” Journal of Child and Family Studies 29 (10): 2982–2991. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01723-3.

- Brownfield, D., and A. M. Sorenson. 1994. “Sibship Size and Delinquency.” Deviant Behavior 15 (1): 42–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.1994.9967957.

- Cameron, A. C., and P. K. Trivedi. 1998. Regression Analysis of Count Data. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Carlsson, E. 2022. “The Realization of Short-Term Fertility Intentions Among Immigrants and Children of Immigrants in Norway and Sweden.” International Migration Review 57 (3): 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/01979183221107930.

- Chen, B. B., X. Chen, and X. Wang. 2021. “Siblings versus Parents: Warm Relationships and Shyness Among Chinese Adolescents.” Social Development 30 (3): 883–896. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12509.

- Clogg, C. C., E. Petkova, and A. Haritou. 1995. “Statistical Methods for Comparing Regression Coefficients Between Models.” American Journal of Sociology 100 (5): 1261–1293. https://doi.org/10.1086/230638.

- Collier, N. L. 2020. “Delinquent by the Dozen: Reexamining the Relationship between Family Size and Offending.” Doctoral diss., Florida State University. https://purl.lib.fsu.edu/diginole/2020_Spring_Collier_fsu_0071E_15727.

- Collier, N. L., and D. P. Mears. 2022. “Delinquent by the Dozen: Youth from Larger Families Engage in More Delinquency—Fact or Myth?” Crime & Delinquency 69 (10): 1843–1870. https://doi.org/10.1177/00111287221088036.

- Cookston, J. T. 1999. “Parental Supervision and Family Structure: Effects on Adolescent Problem Behaviors.” Journal of Divorce & Remarriage 32 (1–2): 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1300/J087v32n01_07.

- Downey, D. B. 1995. “When Bigger Is Not Better: Family Size, Parental Resources, and children’s Educational Performance.” American Sociological Review 60 (5): 746–761. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096320.

- Downey, D. B. 2001. “Number of Siblings and Intellectual Development: The Resource Dilution Explanation.” American Psychologist 56 (6–7): 497–504. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.6-7.497.

- Downey, D. B., and R. Cao. 2023. “Number of Siblings and Mental Health Among Adolescents: Evidence from the U.S. and China.” Journal of Family Issues 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X231220045.

- Downey, D. B., D. J. Condron, and D. Yucel. 2015. “Number of siblings and social skills revisited among American fifth graders.” Journal of Family Issues 36 (2): 273–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X13507569.

- Farrington, D. P. 1987. “Early Precursors of Frequent Offending.” In From Children to Citizens: Families, Schools, and Delinquency Prevention, edited by J. Q. Wilson and G. C. Loury, 27–50, Springer-Verlag.

- Farrington, D. P. 2011. “Families and Crime.” In Crime and Public Policy, edited by J. W. Wilson and J. Petersilia, 130–157, Oxford University Press.

- Farrington, D. P., M. M. Ttofi, and A. R. Piquero. 2016. “Risk, Promotive, and Protective Factors in Youth Offending: Results from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development.” Journal of Criminal Justice 45:63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2016.02.014.

- Fischer, D. 1984. “Family size and delinquency.” Perceptual and Motor Skills 58 (2): 527–534. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1984.58.2.527.

- Fomby, P., and C. Osbourne. 2017. “Family Instability, Multipartner Fertility, and Behavior in Middle Childhood.” Journal of Marriage and Family 79 (1): 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12349.

- Georgas, J., J. W. Berry, F. J. R. van de Vijver, Ç. Kağitçibaşi, and Y. H. Poortinga, eds. 2006. Families Across Cultures: A 30-Nation Psychological Study. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511489822.

- Gottfredson, M. R., and T. Hirschi. 1990. A General Theory of Crime. Stanford University Press.

- Hagawen, K. J., and S. P. Morgan. 2005. “Intended and Ideal Family Size in the United States, 1970–2002.” Population and Development Review 31 (3): 507–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00081.x.

- Heck, C., and A. Walsh. 2000. “The Effects of Maltreatment and Family Structure on Minor and Serious Delinquency.” International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 44 (2): 178–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X00442004.

- Hilbe, J. M. 2011. Negative binomial regression. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hirschi, T. 1969. Causes of Delinquency. University of California Press.

- Hoeve, M., J. S. Dubas, V. I. Eichelsheim, P. H. Van der Laan, W. Smeenk, and J. R. Gerris. 2009. “The Relationship Between Parenting and Delinquency: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 37 (6): 749–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-009-9310-8.

- Hoeve, M., G. J. J. Stams, C. E. Van der Put, J. S. Dubas, P. H. Van der Laan, and J. R. Gerris. 2012. “A Meta-Analysis of Attachment to Parents and Delinquency.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 40 (5): 771–785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9608-1.

- Jann, B. 2014. “Plotting Regression Coefficients and Other Estimates.” The Stata Journal 14 (4): 708–737. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X1401400402.

- Jensen, A. C., S. E. Killoren, N. Campione-Barr, J. Padilla, and B. B. Chen. 2023. “Sibling Relationships in Adolescence and Young Adulthood in Multiple Contexts: A Critical Review.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 40 (2): 384–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075221104188.

- Killoren, S. E., L. A. Wheeler, K. A. Updegraff, S. A. Rodríguez de Jésus, and S. M. McHale. 2015. “Longitudinal Associations Among Parental Acceptance, Familism Values, and Sibling Intimacy in Mexican‐Origin Families.” Family Process 54 (2): 217–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12126.

- Knaappila, N., M. Marttunen, S. Fröjd, N. Lindberg, and R. Kaltiala-Heino. 2019. “Changes in Delinquency According to Socioeconomic Status Among Finnish Adolescents from 2000 to 2015.” Scandinavian Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychology 7 (1): 52–59. https://doi.org/10.21307/sjcapp-2019-008.

- Kroese, J., W. Bernasco, A. C. Liefbroer, and J. Rouwendal. 2021. “Growing Up in Single-Parent Families and the Criminal Involvement of Adolescents: A Systematic Review.” Psychology, Crime & Law 27 (1): 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2020.1774589.

- Lauritsen, J. L. 1993. “Sibling Resemblance in Juvenile Delinquency: Findings from the National Youth Survey.” Criminology 31 (3): 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1993.tb01135.x.

- LeBouef, S., and J. Dworkin. 2021. “Siblings As a Context for Positive Development: Closeness, Communication, and Well-Being.” Adolescents 1 (3): 283–293. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents1030021.

- Manning, W. D., S. L. Brown, and J. B. Stykes. 2014. “Family Complexity Among Children in the United States.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 654 (1): 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716214524515.

- Mercer, N., D. P. Farrington, M. M. Ttofi, L. Kejisers, S. Branje, and W. Meeus. 2016. “Childhood Predictors and Adult Life Success of Adolescent Delinquency Abstainers.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 44 (3): 613–624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0061-4.

- Milevsky, A. 2022. “Relationships in Transition: Maternal and Paternal Parenting Styles and Change in Sibling Dynamics During Adolescence.” European Journal of Developmental Psychology 19 (1): 89–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2020.1865144.

- Mize, T. D., L. Doan, and J. S. Long. 2019. “A General Framework for Comparing Predictions and Marginal Effects Across Models.” Sociological Methodology 49 (1): 152–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081175019852763.

- Mogstad, M., and M. Wiswall. 2016. “Testing the Quantity-Quality Model of Fertility: Estimation Using Unrestricted Family Size Models.” Quantitative Economics 7 (1): 157–192. https://doi.org/10.3982/QE322.

- Muola, J. M., M. N. Ndung’u, and N. Fredrick. 2009. “The Relationship Between Family Functions and Juvenile Delinquency: A Case of Nakuru Municipality, Kenya.” An International Multi Disciplinary Journal, Ethiopia 3 (5): 67–84. https://doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v3i5.51142.

- Murray, J., and D. P. Farrington. 2010. “Risk Factors for Conduct Disorder and Delinquency: Key Findings from Longitudinal Studies.” The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 55 (10): 633–642. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371005501003.

- Nilsson, E.-L. 2017. “Analyzing Gender Differences in the Relationship Between Family Influences and Adolescent Offending Among Boys and Girls.” Child Indicators Research 10 (4): 1079–1094. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-016-9435-6.

- Ohlsson-Wijk, S., J. Turunen, and G. Andersson. 2020. “Family Forerunners? An Overview of Family Demographic Change in Sweden.” International Handbook on the Demography of Marriage and the Family 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35079-6_5.

- Pierce, H., and M. S. Jones. 2022. “Gender Differences in the Accumulation, Timing, and Duration of Childhood Adverse Experiences and Youth Delinquency in Fragile Families.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 59 (1): 3–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224278211003227.

- Racz, S. J., and R. J. McMahon. 2011. “The Relationship Between Parental Knowledge and Monitoring and Child and Adolescent Conduct Problems: A 10-Year Update.” Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 14 (4): 377–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0099-y.

- Sampson, R. J., and J. H. Laub. 1994. “Urban Poverty and the Family Context of Delinquency.” Child Development 65 (2): 523–540. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00767.x.

- Sobotka, T., and E. Beaujouan. 2014. “Two Is Best? The Persistence of a Two-Child Family Ideal in Europe.” Population and Development Review 40 (3): 391–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2014.00691.x.

- Svensson, R. 2003. “Gender Differences in Adolescent Drug Use: The Impact of Parental Monitoring and Peer Deviance.” Youth & Society 34 (3): 300–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X02250095.

- Svensson, R., and B. Johnson. 2022. “Does it Matter in What Family Constellations Adolescents Live? Reconsidering the Relationship Between Family Structure and Delinquent Behaviour.” Public Library of Science ONE 17 (4). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265964.

- Svensson, R., and D. Shannon. 2021. “Immigrant Background and Crime Among Young People: An Examination of the Importance of Delinquent Friends Based on National Self-Report Data.” Youth & Society 53 (8): 1335–1355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X20942248.

- Sweeten, G. 2012. “Scaling Criminal Offending.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 28 (3): 533–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-011-9160-8-.

- Touliatos, J., and B. W. Lindholm. 1980. “Birth Order, Family Size, and children’s Mental Health.” Psychological Reports 46 (3_suppl): 1097–1098. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1980.46.3c.1097.

- Tygart, C. E. 1991. “Juvenile Delinquency and Number of Children in a Family.” Youth and Society 22 (4): 525–536. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X91022004005.

- Vasiljevic, Z., L. Pauwels, E.-L. Nilsson, D. Shannon, and R. Svensson. 2023. “Do Moral Values Moderate the Relationship Between Immigrant-School Concentrations and Violent Offdending? A Cross-Level Interaction Analysis of Self-Reported Violence in Sweden.” Deviant Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2023.2266550.

- Vasiljevic, Z., R. Svensson, and D. Shannon. 2021. “Trends in Alcohol Intoxication Among Native and Immigrant Youth in Sweden, 1999-2017: A Comparison Across Family Structure and Parental Employment Status.” International Journal of Drug Policy 98:103397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103397.

- Weesie, J. 1999. “Seemingly Unrelated Estimation: An Application of the Cluster Adjusted Sandwich Estimator.” Stata Tech Bull 52:34–47.

- Wikström, P. O. H., D. Oberwittler, K. Treiber, and B. Hardie. 2012. Breaking Rules: The Social and Situational Dynamics of Young people’s Urban Crime. OUP Oxford.

- Yucel, D., and D. B. Downey. 2015. “When Quality Trumps Quantity: Siblings and the Development of Peer Relationships.” Child Indicators Research 8 (4): 845–865. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-014-9276-0.

Appendix

Table A1. Items measuring self-reported delinquency.

Figure A1. Predictions of number of siblings and delinquency variety (including squared term of number of siblings). Results presented with 95% CI from negative binomial regression analysis. Controls included are: gender, second generation mixed, second generation, born abroad, not in employment, split family, attachment to parents, parental monitoring, year of study.

Table A2. The association between prevalence of violence and number of siblings.

Table A3. The association between prevalence of serious theft and number of siblings.