Abstract

The objective of this study was to determine the factors influencing consumer intention to donate blood in an emerging market setting. A quantitative research design was followed that entailed the collection of data from 308 non-donor respondents, using a self-administered online questionnaire. The conceptual model and hypotheses were analysed statistically, using SPSS to conduct reliability analysis, correlation analysis, and multiple regression analysis. The findings revealed that awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, and personal norms had a positive and significant influence on consumers’ intention to donate blood. Ascription of responsibility was the largest influencer of personal norms towards blood donation.

Introduction

Blood shortages are a major problem worldwide (Chen et al., Citation2021). The current supply of blood is not adequate to meet the needs of global health care systems (Chen et al., Citation2020). Blood is a crucial resource in health care to sustain life (Mohanty et al., Citation2023). This means that an adequate and sustainable supply of blood is vital for clinical and medical care (Chen et al., Citation2020). An increase in the global population and the greater overall life expectancy of individuals who rely on blood donations for their medical needs have increased the demand for blood products (Ekşi et al., Citation2022). From a South African perspective, Duh and Dabula (Citation2021) note that the increased number of road accidents, chronic diseases such as cancer, complications during pregnancies, and the growing need for complex surgeries have meant that health care systems need a greater, continual, and secure supply of blood.

The World Health Organization (WHO) states that, to maintain a sufficient and secure supply of blood, a fixed pool of donors who volunteer consistently and who are not financially rewarded is required (Viwattanakulvanid & Oo, Citation2022). The WHO adds that, for blood supply to meet demand, blood donors must represent between 3 and 5% of the population of a country (Zucoloto et al., Citation2020). This sustained blood supply is necessary because blood can be stored and used for only a limited time (Halawani, Citation2022).

In South Africa, there is a persistently high demand for blood donations owing to health disparities and diseases such as tuberculosis, cancer, and HIV and AIDS (Rambiritch et al., Citation2021). Blood is also collected for use in childbirth, laboratories, and paediatric and orthopaedic care (Ndongeni-Ntlebi, Citation2021). However, less than 1% of the country’s population donate blood (Duh & Dabula, Citation2021). The Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated the blood shortage crisis by restricting attempts to enroll blood donors and to maintain sufficient blood supplies (Rambiritch et al., Citation2021).

Misconceptions about blood donation have been recognized as part of the cause of the shortage of blood donors (Ekşi et al., Citation2022). Zucoloto et al. (Citation2019) state that misconceptions about blood donation include the eligibility of the donor, the health safety concerns of the donor about a drop in heart rate or blood pressure during the blood donation process, and misconceptions about the process of donating blood. Negative attitudes towards blood donation also prevent people from donating blood (Ekşi et al., Citation2022). Alanazi et al. (Citation2018) state that consumers have negative attitudes towards blood donation when they do not receive a reward for donating blood, or because of the belief that a disease could be contracted during the blood donation process. Klinkenberg et al. (Citation2019) state that negative attitudes towards blood donation arise from the policies of blood banks and from their location in places that are not convenient for all consumers to donate blood. Last, consumers are nervous about blood donation owing to their fear of needles or of fainting because of the injection, the pain caused by injections, their fear of blood, and anxiety about a transmissible disease being discovered while they are donating blood (Ekşi et al., Citation2022; Zucoloto et al., Citation2019).

To overcome the problem of blood shortages, blood donation organizations have used social networking sites such as Twitter, Facebook, and WeChat to enhance their blood donation advertising and to boost blood donor recruitment (Chen et al., Citation2021). Mobile blood collection drive campaigns have been another way to increase blood donor recruitment (Halawani, Citation2022). Last, traditional media such as television, radio, and billboards have been used as a form of blood donation advertising (Duh & Dabula, Citation2021). South African blood donation organizations, such as the South African National Blood Service (SANBS), a non-profit organization with non-remunerated volunteers, have used marketing such as face-to-face recruitment, promotional campaigns, and telephonic and short message service (SMS) contact to recruit donors (Glatt et al., Citation2021; Mitchel et al., Citation2019). Despite these marketing efforts, the demand for blood products has increased across South Africa while the supply remains inadequate (Duh & Dabula, Citation2021; Maphanga, Citation2021). Consequently, blood banks and social marketing practitioners are encouraged to commission research to investigate the factors that affect consumers’ intention to donate blood in order to find ways to attract regular and voluntary donors to address the blood shortages (Zucoloto et al., Citation2020).

In order to achieve this, it is necessary for blood donation organizations to understand the factors that influence consumers’ intention to donate blood. However, there is a void in the marketing literature regarding blood donation from an emerging market perspective. Thus Burzynski et al. (Citation2016) argue that further research is required, particularly from a sub-Saharan perspective, since current research focuses on blood donation from the perspectives of developed countries. In this respect, the objective of this study is to investigate the factors influencing consumers’ intention to donate blood in South Africa. The norm activation model (NAM) has been particularly chosen for this study; previous research indicates that there has been an over-reliance on the theory of planned behaviour (TBP) to determine individuals’ blood donation intentions, whereas other theories might provide a different perspective (M’Sallem, Citation2022). The NAM has been successfully used in the study of prosocial behaviours; and in this study, the NAM was used to provide a new perspective on blood donation, and to see how the NAM could be used to understand the prosocial behavioural intentions of people towards blood donation (Rezaei et al., Citation2019). In order to meet the objective of the study, research was conducted in an emerging country, South Africa. The survey was carried out among consumers between the ages of 18 and 69 years who had not previously donated blood in order to determine the factors that might influence their intention to start donating blood in the future.

The findings of this study will assist managers of blood donation organizations to implement effective health marketing strategies to positively influence blood donation intention among potential non-donors in South Africa. From a theoretical perspective, the NAM theory has been adapted for the study to understand people’s prosocial behaviours in relation to their moral obligation to donate blood (Liu et al., Citation2017). However, an alternative construct, behavioural intention, has been integrated to demonstrate the motivation of an individual regarding their decision to deliberately perform a specific behaviour. Since the participants of the study did not in fact donate blood, “behaviour” was an inappropriate construct (Rezaei et al., Citation2019). Managers of blood donor organizations using a recommended marketing approach, such as pathos, could positively increase blood donations by using emotion to prompt potential blood donors. This new insight provided by the study would assist blood donor organizations to contribute to local and global initiatives, such as the United Nations’ sustainable goals and the South African Nation Development Plan, to motivate individuals to take accountability and to act, in order to attain better healthcare and good health for people by 2030 (National Development Plan, Citation2022; United Nations, Citation2022).

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section “Theoretical overview” presents the theoretical overview and the theoretical constructs that make up the study. Section “Methodology” explores the research methodology proposed for the study. Section “Results” presents the results of the study, followed by the discussion of the results in Section “Discussion” and the recommendations in Section “Recommendations.” Section “Conclusion, limitations, and future research” concludes the paper by summarizing the main findings of the study, recognizing its limitations, and presenting recommendations for future research.

Theoretical overview

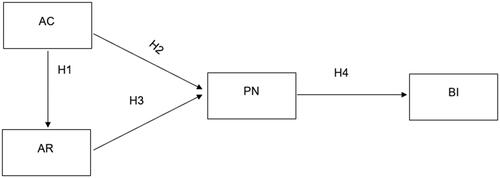

The theory used to support the conceptual model of this study was the norm activation model (NAM) to provide further insight into pro-social and pro-environmental behaviours, such as blood donation (Wang et al., Citation2019). The NAM model is a prominently used social psychology model that focuses on an individual’s behavioural intentions derived from philanthropic and moral beliefs (Kim & Hwang, Citation2020). The NAM model was developed by Schwarts in 1977, and consists of three elements: awareness of consequences (AC), ascription of responsibility (AR), and personal norms (PN) (Javid et al., Citation2021). The theory suggests that people are urged to participate in prosocial behaviours, such as protecting others and the environment, because of moral commitments. Essentially, if an individual recognizes the consequences of certain behaviours (awareness of consequences), whether they be their action or inaction towards a particular cause, then this recognition will lead the individual to consider how their behaviour contributes to the problem and whether they could or could not help to solve the issue (ascription of responsibility) (Liu et al., Citation2017). The theory further expounds how participation in prosocial behaviours is motivated by personal norms. Thus, depending on the consistency with which the individual’s behaviour is aligned with their personal norms, they might feel a sense of either accomplishment or guilt (Liu et al., Citation2017; Rui et al., Citation2022).

Consequently, the NAM has been found to hold predictive validity across numerous studies: in waste management (Wang et al., Citation2019); energy consumption (Song et al., Citation2019); environmental complaint intention (Zhang et al., Citation2018); and conservation (Joanes, Citation2019). This study will explore, the importance of actioning NAM in relation to prosocial acts resulting from personal norms. When NAM is applied an individual is conscious of the consequences (AC) and sets the responsibility (AR) to respond to save lives by donating blood. (Sia & Jose, Citation2019). It further suggests the relationships between awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, and personal norms. Last, the model proposes that there is a relationship between personal norms and behavioural intention to donate blood. Intention was applied to determine the factors influencing the intention to donate blood, such as awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, and personal norms (Ratebo et al., Citation2020). Intention can be defined as the mental expression of a person who is willing to perform an action. This includes the degree to which an individual forms a positive or negative assessment of a behaviour (Pauli et al., Citation2017). These NAM constructs are discussed in the sections that follow.

Awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility

In the NAM, “awareness of consequences” is defined as the degree to which an individual realizes the positive or negative implications of performing or not performing certain behaviours (Nguyen, Citation2022). In the context of this study, the assumption could be made that, if consumers recognize the consequences of not donating blood, they will intend to develop the need to donate blood. “Ascription of responsibility” is defined as a person’s feeling of responsibility to carry out a certain behaviour (Esfandiar et al., Citation2021). In the context of this study, the assumption could be made that, if consumers feel a certain degree of accountability for the blood shortage crisis as a result of their not donating blood, they will intend to develop the need to donate blood. Rezaei et al. (Citation2019) state that an individual’s awareness of consequences has a positive and significant influence on that individual’s ascription of responsibility, indicating that, if a consumer realizes the negative consequences of not donating blood, such as blood shortages in hospitals, they will feel a stronger degree of responsibility for the blood shortages. Therefore, consumers who do not donate blood have a high likelihood of feeling accountable for blood shortages when they become aware of the negative consequences of not donating blood. This has been confirmed by numerous studies (Bennett et al., Citation2022; Govaerts & Olsen, Citation2022; Nguyen, Citation2022) that have found that the awareness of consequences had a positive and significant impact on the ascription of responsibility.

The following hypothesis has therefore been formulated, based on the two constructs discussed above:

H1: There is a direct and positive relationship between the awareness of the consequences of donating blood and the ascription of responsibility for donating blood.

Personal norms

In the NAM, “personal norms” refers to an individual’s ethical duty to participate in or refrain from a certain activity (Roos & Hahn, Citation2019). Rezaei et al. (Citation2019) propose that awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility are antecedents of personal norms, and that they have a positive effect on personal norms. Shin et al. (Citation2018) support this, stating that only when both awareness of consequences and ascription of reasonability have a strong effect on personal norms will personal norms be activated. Therefore, in the context of this study, it could be assumed that consumers’ extent of awareness of the negative consequences of not participating in blood donation will likely cause them to form a strong sense of responsibility for blood shortages, and thus to develop a moral obligation to take part in blood donation practices to help combat blood shortages. This has been confirmed by previous research that have used the NAM to study environmental behaviour (Fang et al., Citation2019; Han et al., Citation2019; Rezaei et al., Citation2019) and have found that awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility have a positive and significant influence on personal norms.

The following hypotheses have been formulated on the basis of the constructs discussed above:

H2: There is a direct and positive relationship between the awareness of the consequences of donating blood and personal norms relating to blood donation.

H3: There is a direct and positive relationship between the ascription of responsibility for donating blood and personal norms about blood donation.

Behavioural intention

The literature suggests that behaviour is based on an individual’s belief about what is morally right, which is reflected by personal norms (Liu et al., Citation2017). Thus, based on this motivation, an individual will act pro-socially by carrying out a specific behaviour (Esfandiar et al., Citation2021). However, in the context of this study, individuals who had not donated blood before constituted the sample. Thus, it would be ineffective to determine the act of carrying out blood donation activities from individuals who had not participated in blood donation behaviour, making “behaviour” an unsuitable construct for this case. Therefore, “behavioural intention” would be a suitable construct, since it demonstrates the motivation of an individual regarding their deliberate decision potentially to perform a specific behaviour (Rezaei et al., Citation2019). This means that an individual will develop an intention to act pro-socially (Esfandiar et al., Citation2021).

The following hypothesis has been formulated, based on the literature discussed above:

H4: There is a direct and positive relationship between personal norms and a consumer’s intention to donate blood.

A conceptual model was formulated to examine and describe the relationships between the constructs that were hypothesized for this study. The conceptual model for this study is presented in , which is based on the NAM and indicates the three constructs used in this study (awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, and personal norms) that determine South African consumers’ intention to donate blood.

Methodology

Research method and design

Because of the objective that this study aimed to achieve and the quantitative nature of the research, a positivist research paradigm was used to allow for an objective view by identifying variable relations (Al-Ababneh, Citation2020) while studying relationships to develop law-like generalizations (Saunders et al., Citation2019). This study was based on the use of a quantitative methodology to understand the causes of consumers’ intention to donate blood. The approach was implemented to test the hypotheses and to formulate predictions about the relationships between the constructs introduced in the research study.

Sampling and data collection

For this study, two-stage non-probability sampling in the form of convenience sampling followed by snowball sampling was used. Convenience sampling is a type of non-probability sampling that is exploratory in nature and that allows researchers to generate data easily, based on factors of convenience such as geographical location, engagement, and access (Malhotra et al., Citation2017). Snowball sampling is a process in which research participants are identified and recruited by currently enrolled participants with the aim of reaching a sufficient number of subjects (Malhotra et al., Citation2017). The online questionnaire was distributed using a Google Forms link via online platforms such as LinkedIn, Instagram, WhatsApp, Facebook, and email. After clicking on the link, respondents were able to complete and submit the questionnaire. Upon completion of the questionnaire, respondents were encouraged to share the link with their peers, friends, and family who had not previously donated blood.

For this research study, ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Johannesburg School of Consumer Intelligence and Information Systems Research and Ethics Committee. The ethical clearance number for this research is 2022SCiiS028. The targeted respondents were South African consumers between the ages 18 and 69 who had not previously donated blood. In the cover letter of the questionnaire, respondents were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw (discontinue) at any time without incurring negative consequences. To obtain consent from the respondents, they were required to indicate whether they consented to participating in the research study before going on to complete the questionnaire. According to Saunders et al. (Citation2019), a recommended sample size for the quantitative method is 250 or more, as a higher participation count results in more accurate findings. Thus, a sample size of 250 participants was selected, and 308 usable questionnaires were used in the study. This choice was based on the greater accuracy yielded by a larger sample size (Saunders et al., Citation2019).

The appropriate data collection instrument used for this study was a self-administrated questionnaire. Scale items from previous studies were modified to develop the measuring instrument used in this study. The respondents accessed the questionnaire via the internet, using a hyperlink in a web browser (online questionnaire) on their mobile device (tablet, smartphone) or computer (Saunders et al., Citation2019). The measurement scales were categorized into awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, personal norms, and behavioural intention. The measurement scales used in this study have been adapted from previous and related studies. These constructs were measured on a five-point Likert scale in which “1” indicated “strongly disagree” and “5” indicated “strongly agree.” The awareness of consequences construct was adapted from research conducted by Arkorful (Citation2022; Liu et al., Citation2017). They both had Cronbach alpha values of 0.84. Statements to measure awareness of consequences included, for example, “Donating blood saves lives.” The ascription of responsibility measures was derived from research conducted by Nguyen (Citation2022; Arkorful, Citation2022) and they both produced a Cronbach alpha values above 0.8. Statements to measure this construct included, for example, “I feel partly responsible for the blood donation shortages in South Africa.” Statements to measure personal norms were adapted from (Arkorful, Citation2022; Setiwan et al., Citation2014; Shin et al., Citation2018). These produced a Cronbach alpha above 0.6. As examples, statements read “I have a moral obligation to donate blood.” Behavioural intention statements were adapted from research conducted by Chen (Citation2017), producing a Cronbach alpha of 0.9. As examples, statements read “I intend to start donating blood.” A screening question was included: only respondents who indicated that they had not donated blood before were asked to complete the questionnaire. Section A consisted of background questions, such as race, age, gender, employment status, highest education level, and knowledge about blood donation, and were measured using nominal and ordinal scales. Section B consisted of the measuring dimensions of the NAM on five-point Likert scales, namely awareness of consequence, ascription of responsibility, personal norms, and behavioural intention.

Data analysis

The data collected for this study was coded, cleaned, edited, and examined before proceeding to use statistical analysis software, Statistics Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28, for the analysis. SPSS was employed to examine the descriptive statistics, inspect the data for frequency distribution, and assess each questionnaire item for skewness and kurtosis to establish whether the data was normally distributed. A reliability analysis was completed by using Cronbach’s alpha to test the reliability of the measurements (Wiid & Diggines, Citation2017). Further, to determine the relationships between the constructs, a correlation analysis was conducted. Lastly, to test the proposed hypotheses, a multiple regression analysis was conducted (Saunders et al., Citation2019).

Results

Demographic profile of respondents and blood donation knowledge

In terms of gender, 60.4% of the respondents were females and 38% were males. In addition, the group age of 20–29 accounted for 51.6% of the respondents. In respect of educational qualifications, 50.3% of the respondents held an undergraduate qualification, followed by 27.6% who had a Grade Twelve certificate. Regarding the employment status, the results indicated that 36.4% of the respondents were full-time students, followed by 31.2% who were employed full-time. shows how knowledgeable respondents were about blood donation. Concerning how frequently blood ought to be donated, 42.9% of the respondents indicated that they thought individuals should donate blood two to three times a year, followed by 24.4% who thought that individuals should donate blood three to four times a year. The number of respondents who knew where to donate blood accounted for 71.1% of the respondents. The number of respondents who knew when there were blood donation drives and initiatives was 57.1%, while 42.9% of the respondents indicated that they did not know about such drives.

Table 1. Knowledge about blood donation.

Descriptive statistics

A descriptive analysis of the measures of the four constructs in this study was carried out (awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, personal norms, and behavioural intention), as shown in . These constructs were measured on a five-point Likert scale in which “1” indicated “strongly disagree” and “5” indicated “strongly agree.”

Table 2. Descriptive analysis of the measures of the constructs.

The overall mean for awareness of consequences was 4.48, indicating that those respondents agreed with most of the statements measuring awareness of consequences of blood donation. The most-agreed-upon statement from the respondents was AC1: “Donating blood saves lives” (mean = 4.67; SD = 0.651), while the least-agreed-upon statement was AC2: “Donating blood is good for the health system” (mean = 4.09; SD = 0.972).

The overall mean for ascription of responsibility was 3.38, which is the midpoint, indicating that respondents neither agreed nor disagreed, but leaning towards agreeing with statements measuring their ascription of responsibility for blood donation. The statement with which most respondents agreed was AR3: “Blood donation is not only the responsibility of others, but mine too” (mean = 3.73; SD = 1.116). The least-agreed-upon statement was AR4: “I feel partly responsible for the shortage of blood in South Africa” (mean = 3.07; SD = 1.354).

The overall mean for personal norms was 3.68, indicating that respondents neither agreed nor disagreed, but leaning more towards agreeing with statements measuring their personal norms about blood donation. The statement with which most respondents agreed was PN3: “I feel that it is important to donate blood” (mean = 4.18; SD = 0.851). The least-agreed-upon statement was PN1: “I have a moral obligation to donate blood” (mean = 3.24; SD = 1.256).

The overall mean for behavioural intention was 3.40, indicating that respondents neither agreed nor disagreed, but leaned towards agreeing with statements measuring their intention to donate blood. The statement with which most respondents agreed was BI4: “I intend to tell my friends and family about the importance of donating blood” (mean = 3.62; SD = 1.225). The least-agreed-upon statement was BI1, “I intend to start donating blood” (mean = 3.20; SD = 1.328).

Correlation analysis

Pearson’s correlation was used to test the relationships between the constructs in the study, as presented in . The correlation coefficient assesses the extent of collinearity between two constructs which results in values from −1 and 1(Wei et al., Citation2020). A correlation value of 0 indicated a week correlation between constructs, with a correlation value closer to 1 indicates a strong correlation. The results presented in indicate a strong correlation between personal norms and ascription of responsibility (r = 0.751; p < 0.01), while the correlation between behavioural intention and awareness of consequences was weak (r = 0.141; p < 0.05).

Table 3. Correlation analysis.

Reliability

Cronbach’s alpha was used to analyze the reliability of the constructs used in the conceptual model. The four constructs were confirmed to have good reliability as indicated by the results presented in . Cronbach alpha values range between 0 and 1, with the recommended Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.7 or higher. Cronbach’s alpha values of between 0.60 and 0.70 are considered to indicate acceptable reliability, values between 0.70 and 0.80 are considered to indicate good reliability, while values above 0.80 indicate a high reliability (Wiid & Diggines, Citation2017; Zhong et al., Citation2021). The results presented in show that awareness of consequences had a good reliability, while the rest of the constructs had a high reliability indicating that the criterion for reliability were achieved for this study.

Table 4. Cronbach’s alpha.

Regression analysis

Collinearity diagnostics

To evaluate the collinearity of the independent variables in the research study, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was analyzed. Recent research suggests that a more restrictive threshold of VIF = 5 or VIF = 3 should be adopted to indicate traces of multicollinearity in constructs (Ahmed, Citation2022). Further research has suggested that even a VIF threshold of 5 is too liberal, since collinearity issues occur at lower VIF levels. Thus, a conservative VIF threshold of 3 was identified as most appropriate to indicate collinearity issues; VIF values below 3 would indicate no multicollinearity in the constructs (Sarstedt et al., Citation2022). The results presented in show that, for this study, the VIF values ranged between 1.000 and 1.044, which is below the conservative threshold of 3. Thus, it could be concluded that there was no multicollinearity between the independent variables.

Table 5. Summary of regression analysis results.

Hypothesis testing

The multiple regression analysis was conducted to determine the study’s hypotheses. The conceptual model () was assessed to validate the proposed hypotheses (H1–H4). This included observing the R squared value, the beta (β) value and the sig. value (p-value). The R square indicates the explanatory power of the model in predicting behavioural intention towards donating blood. A positive beta (β) value and a sig. value less than 0.05 was required for the hypotheses to be deemed valid. The outcomes of these findings are shown in .

Results presented in indicate that The R square value for awareness of consequences explained a 4.3% variance in ascription of responsibility towards consumers’ intention to donate blood. Awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility explained a 58.7% variance in personal norms towards consumers’ intention to donate blood. Lastly, personal norms indicated a 31.1% variance in behavioural intention towards donating blood. Based these results, the highest level of variance was recorded between AC and AR and PN and the lowest level of variance was recorded between AC and AR.

The results of the relationships between awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, personal norms, and behavioural intention are presented in , and they show that H1–H4 could be accepted. The results also indicate that ascription of responsibility was the largest predictor of behavioural intention (β = 0.718).

Discussion

All four hypotheses developed for the study were accepted. First, for H1 a direct and positive relationship was predicted between awareness of consequences of donating blood and ascription of responsibility for blood donation. The results in indicate that the relationship between these constructs was statistically significant (β = 0.206, <0.001). The findings correlate with the earlier studies of Nguyen (Citation2022) and Govaerts and Olsen (Citation2022), who used the NAM to predict pro-social behaviours. Nguyen (Citation2022) found that awareness of consequences had a positive effect on ascription of responsibility. Govaerts et al. (2022) confirmed that there was a high degree of relationship between awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility. In addition, research into the donation behaviour intention of individuals when donating to food banks concluded that a low awareness of a problem caused individuals to avoid responsibility, thus indicating the reliance of ascription of responsibility on awareness of consequences (Bennett et al., Citation2022). In relation to the current study, these findings show that, if consumers who did not donate blood became aware of the consequences of not donating blood, such as blood shortages, they might assume a sense of responsibility for those blood shortages. These findings are supported by the viewpoint that many individuals have misconceptions about blood donation (Ekşi et al., Citation2022), which would influence their feeling of responsibility for blood donation shortages.

Second, the results indicate that both awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility had a direct and positive relationship with personal norms (β = 0.156 < 0.001; β = 0.718, <0.001); therefore, H2 and H3 were accepted. This was in accordance with the earlier research by Rezaei et al. (Citation2019), who concluded that both awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility were key components positively affected personal norms This is also consistent with research conducted by Shin et al. (Citation2018), who concluded that only when both awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility had a strong effect on personal norms would personal norms be activated. These conclusions have been proposed in numerous studies (Fang et al., Citation2019; Han et al., Citation2019). It is noteworthy that ascription of responsibility was the largest predictor of personal norms about blood donation. In relation to this study, it could be assumed that, if consumers who did not donate blood were aware of the negative consequences of this inaction and felt a sense of responsibility for it, they would develop a moral obligation to donate blood.

Last, the results indicate that personal norms had a direct and positive relationship with behavioural intention (β = 0.559, <0.001); thus, H4 was accepted. The findings are consistent with earlier research that concluded that personal norms had a positive impact on behavioural intention (Han & Hyun, Citation2017; Liu et al., Citation2017; Park & Ha, Citation2014; Shin et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, research relating to the behavioural intention of individuals to donate concluded that personal norms had a significant impact on donation behaviour intention (Chen et al., Citation2019). In relation to this study, it could be concluded that, if consumers developed a moral obligation to donate blood, they would develop an intention to do so.

Recommendations

As blood donation organizations operate within the health sector, The following recommendations aligned to health marketing are proposed for South African blood donation organizations to follow and implement in order to encourage non-donors to donate blood:

The results indicate that awareness of consequence is a significant contributor to ascription of responsibility. It is important that South African blood donation organizations focus on marketing initiatives that will encourage blood donation by consumers who do not currently donate blood. Thus marketing managers of blood donation organizations could use a storytelling campaign: short 30-second videos could be created in which individuals who had donated blood or had used donated blood for health reasons could share their stories – for example, why they donated blood, or needed blood, how the blood products saved their life, and what would have happened if they had not received the donated blood. This campaign could enhance non-donors’ awareness of and education about blood donation processes. This is based on Romero-Domínguez et al. (Citation2021) suggestion that messages in health marketing based on testimonies are more effective than encouraging a call to action. As shown in , less than half of non-donors were aware of how frequently blood donation should take place, with only 42.9% indicating that they thought that blood should be donated two to three times a year. The videos could be shared on Instagram and Facebook. These platforms are recommended because the findings of this study indicated that the majority of respondents were in the 20–29 age category and Ceci (Citation2023) showed that people in the age group of 25–34 years were the largest users of Facebook; while Dixon (Citation2022) found that people in the age group of 25–34 years were the largest users of Instagram. This campaign would allow non-donors to become aware of the consequences of not donating blood and possibly develop a sense of responsibility for helping to save other people’s lives, such as the friends and family from whom they might hear the stories.

The results showed that awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility notably influenced personal norms. The findings provided an indication that the largest contributor to personal norms was ascription of responsibility. Thus, blood donation organizations should focus on invoking individuals’ feelings of responsibility for donating blood. Butt et al. (Citation2019) recommend that through marketing research, health organizations should understand consumer behaviour and develop strategies to accommodate, communicate and engage with consumer needs in the broad field of health. It is recommended, therefore, that blood donation organizations focus on developing health marketing strategies that communicate consumers’ responsibility to donate blood for both their personal and social domains (Deshpande et al., Citation2009). Blood donation organizations could promote the idea that blood donation is the responsibility of everyone who is eligible by encouraging groups of eligible donors to donate blood together. A campaign could be implemented in which individuals who donate blood in groups of two or more could have their experience posted and tagged on the blood donation organizations’ social media, such as on Instagram and Facebook, to promote their individual and collective responsibility. By posting these events to social media, Deshpande et al. (Citation2009) further state that healthcare organizations can enhance their communication with consumers. Donors could use electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) by reposting the story to their own Facebook or Instagram profiles to encourage a larger audience. Pourfakhimi et al. (Citation2020) state that the interpersonal exchange of information that eWOM creates positively impacts consumer behaviour, as it reduces perceived risk and enhances trust.

Blood donation organizations could further utilize health marketing strategies to create and communicate information regarding blood donation criteria to promote greater personal engagement and the social intervention of blood donors (Swenson et al., Citation2018). As shown in , the most agreed upon statement was “Blood donation is not only a responsibility of mine, but others too,” indicating that donating blood is dependent on a collective effort to succeed, followed by “I believe that everyone eligible must take the responsibility to donate blood” indicating that a consumer’s eligibility status is important when considering blood donation. A health marketing campaign can be utilized to promote actions conducive to blood donation through the community by educating and engaging with the community on their responsibility to donate blood if eligible, alluding to both personal and social needs through individual responsibility and the responsibility to the greater community (Dutta-Bergman, Citation2003). This can be in the form of short educational and interactive videos that explain the criteria for blood donor eligibility and would allow consumers to tick a digital checklist as they moved through the video. A representative from blood donation organizations could speak in the video about where they operate, how the blood donation process occurs, what the benefits are, and the criteria for eligibility. Blood donation organizations could focus on using key words and phrases that evoke feelings of responsibility from the consumer towards blood donation since Romero-Domínguez et al. (Citation2021) state that health marketing messages based on fact have a greater effect than marketing a call to action. This health marketing campaign would also enhance non-donors’ knowledge of where to go to donate blood, since nearly a third of non-donors did not know where to go to donate blood; and it would educate them about when blood donation drives or initiatives occur, since almost half of non-donor respondents did not know when these occur. These videos could be posted on Instagram and Facebook. This would be applicable since majority of respondents in this study are most likely to use these platforms (Ceci, Citation2023; Dixon, Citation2022).

The results show that personal norms have a significant influence on the intention to donate blood in South Africa. These findings could provide value to blood donation organizations that want to develop marketing strategies aimed at increasing blood donation behaviour, and foster feelings of moral obligation among consumers. Thus, it is recommended that video content be used to appeal to the emotions of individuals (Jeon et al., Citation2022). These communications could provide consumers with messages about the steps they could take to reduce blood shortages, which in return would positively impact their intention to donate blood. This could be distributed in a short 30-40 second video clip posted on YouTube Shorts since Xie et al. (Citation2022) state that emotional appeal is an effective method to increase the engagement of an audience on YouTube videos. These videos could show how the process of donating blood could change lives, further utilizing the effectiveness of personal stories and real-life examples (Romero-Domínguez et al., Citation2021)). Kemp (Citation2022) states that YouTube had 20.35 million users in South Africa in 2022, with YouTube advertisements reaching 61.4% of the South African population. Ceci (Citation2023) adds that the age category that makes the highest use of YouTube worldwide is 25–34-year-olds, which is aligned with the finding of this study that most respondents were in the age category 20–29 years.

Conclusion, limitations, and future research

The objective of the study was to determine the factors that influence the intention of consumers in South Africa who do not currently donate blood to do so. Using the NAM, the results indicated that it is feasible to determine the factors that influence consumers’ intention to donate blood: awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, and personal norms. The study is supported by the results of previous research on prosocial and donation behaviour that have found that it is possible to predict behavioural intention in various settings (Abel & Brown, Citation2022; Chen et al., Citation2019; Javid & Al-Roushdi, Citation2019).

The results of the study have significant theoretical and practical contributions. Theoretically, from a marketing and consumer behaviour perspective, the use of the NAM in this study has contributed to literature, as most studies on blood donation have relied on the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) (Gilchrist et al., Citation2019; Kassie et al., Citation2020; M’Sallem, Citation2022) and therefore this study offers a different approach, through the NAM. A significant number of blood donation studies are located in health sciences journals (Khomenko et al., Citation2020) and not much in health marketing and marketing related journals, therefore this study contributes to literature in health marketing. In addition, blood donation studies have been predominantly focused on developed countries (Hu et al., Citation2017; Khomenko et al., Citation2020), therefore, this study makes a significant contribution to health marketing literature by providing an emerging market perspective on consumers’ blood donation intention (Burzynski et al., Citation2016). Practically, this study could assist South African and other blood donation organizations, particularly in emerging markets, in creating and improving their marketing strategies, with the aim of positively influencing blood donation intention and effectively increasing blood donation uptake. Last, the objectives of this research study are aligned with the targeted healthcare goals for the South African National Development Plan (NDP) and the United Nations (UN) sustainable development goals, specifically Goal 3, to encourage individuals to take the responsibility and initiative to achieve the good health and well-being of humans and to enhance the quality of health care by 2030 (National Development Plan, Citation2022; United Nations, Citation2022).

The limitations of the study are that a questionnaire was used to collect the data and the scale items used were close ended. Thus, respondents were limited in their ability to provide detailed responses. Convenience and snowball methods were adopted along with the use of an online questionnaire, meaning that the researchers could not interact with respondents to provide clarity for those who did not fully understand, thus potentially impacting the reliability of the responses. Last, the researchers of the study found limited previous literature that used the NAM to understand blood donation intention; therefore, this study used research studies that had used the NAM model for donation and prosocial behaviours to support its findings. Future research on blood donation intention could consider using the NAM for further confirmation or disconfirmation. Furthermore, future research could consider a qualitative study using in-depth interviews to gain deeper insights into the factors that influence consumers’ intention to donate blood.

Acknowledgment

No direct funding was received for this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abel, M., & Brown, W. (2022). Prosocial behavior in the time of COVID-19: The effect of private and public role models. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 101, 101942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2022.101942

- Ahmed, W. M. (2022). What drives US stock markets during the COVID-19 pandemic? A global sensitivity analysis. Borsa Istanbul Review, 22(5), 939–960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2022.07.001

- Al-Ababneh, M. (2020). Linking ontology, epistemology and research methodology. Science & Philosophy, 8(1), 75–91.

- Alanazi, M. T., Elagib, H., Aloufi, H. R., Alshammari, B. M., Alanazi, S. M., Alharbi, S. F., Alshamasy, H., & Alrasheedi, R. (2018). Knowledge attitude and practice of blood donation in Hail University. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 5(3), 846–855. https://doi.org/10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20180416

- Arkorful, V. E. (2022). Unravelling electricity theft whistleblowing antecedents using the theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. Energy Policy, 160(2022), 112680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112680

- Bennett, R., Vijaygopal, R., & Kottasz, R. (2022). Who gives to food banks? A study of influences affecting donations to food banks by individuals. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 35(3), 243–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2021.1953672

- Burzynski, E. S., Nam, S. L., & Le Voir, R. (2016). Barriers and motivations to voluntary blood donation in sub‐Saharan African settings: A literature review. ISBT Science Series, 11(2), 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/voxs.12271

- Butt, I., Iqbal, T., & Zohaib, S. (2019). Healthcare marketing: A review of the literature based on citation analysis. Health Marketing Quarterly, 36(4), 271–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/07359683.2019.1680120

- Ceci, L. (2023). Distribution of YouTube users worldwide as of April 2022, by age group and gender. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1287137/youtube-global-users-age-gender-distribution/ (Accessed 10 February 2023).

- Chen, L. (2017). Applying the extended theory of planned behaviour to predict Chinese people’s non‐remunerated blood donation intention and behaviour: The roles of perceived risk and trust in blood collection agencies. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 20(3–4), 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12190

- Chen, Y., Dai, R., Yao, J., & Li, Y. (2019). Donate time or money? The determinants of donation intention in online crowdfunding. Sustainability, 11(16), 4269. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164269

- Chen, X., Liu, L., & Guo, X. (2021). Analysing repeat blood donation behavior via big data. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 121(2), 192–208. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-07-2020-0393

- Chen, X., Wu, S., & Guo, X. (2020). Analyses of factors influencing Chinese repeated blood donation behavior: Delivered value theory perspective. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 120(3), 486–507. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2019-0509

- Deshpande, S., Basil, M. D., & Basil, Z. D. (2009). Factors influencing healthy eating habits among College students: An application of the health belief model. Health Marketing Quarterly, 26(2), 145–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/07359680802619834

- Dixon, S. (2022). Distribution of Facebook users worldwide as of January 2022, by age and gender. https://www-statista-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/statistics/376128/facebook-global-user-age-distribution/ (Accessed 9 August 2022).

- Duh, H. I., & Dabula, N. (2021). Millennials’ socio-psychology and blood donation intention developed from social media communications: A survey of university students. Telematics and Informatics, 58, 101534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101534

- Dutta-Bergman, M. J. (2003). A descriptive narrative of healthy eating. Health Marketing Quarterly, 20(3), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1300/J026v20n03_06

- Esfandiar, K., Dowling, R., Pearce, J., & Goh, E. (2021). What a load of rubbish! The efficacy of theory of planned behaviour and norm activation model in predicting visitors’ binning behaviour in national parks. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 46, 304–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.01.001

- Ekşi, P., Bayrak, B., Yakar, H. K., & Oğuz, S. (2022). Evaluation of nurses’ attitudes and behaviors against blood donation. Transfusion and Apheresis Science, 61(2), 103317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transci.2021.103317

- Fang, W. T., Chiang, Y. T., Ng, E., & Lo, J. C. (2019). Using the norm activation model to predict the pro-environmental behaviors of public servants at the central and local governments in Taiwan. Sustainability, 11(13), 3712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133712

- Gilchrist, P. T., Masser, B. M., Horsley, K., & Ditto, B. (2019). Predicting blood donation intention: The importance of fear. Transfusion, 59(12), 3666–3673. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.15554

- Glatt, T. N., Swanevelder, R., Raj, S. P., Mitchel, J., & Van den Berg, K. (2021). Donor deferral and return patterns: A South Africa perspective. ISBT Science Series, 16(2), 178–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/voxs.12622

- Govaerts, F., & Olsen, T. O. (2022). Exploration of seaweed consumption in Norway using the norm activation model: The moderator role of food innovativeness. Food Quality and Preference, 99, 104511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2021.104511

- Halawani, A. J. (2022). The impact of blood campaigns using mobile blood collection drives on blood supply management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transfusion and Apheresis Science, 61(3), 103354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transci.2022.103354

- Han, H., Hwang, J., Lee, M. J., & Kim, J. (2019). Word-of-mouth, buying, and sacrifice intentions for eco-cruises: Exploring the function of norm activation and value-attitude-behavior. Tourism Management, 70, 430–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.09.006

- Han, H., & Hyun, S. S. (2017). Drivers of customer decision to visit an environmentally responsible museum: Merging the theory of planned behavior and norm activation theory. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(9), 1155–1168. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2017.1304317

- Hu, H., Wang, T., & Fu, Q. (2017). Psychological factors related to donation behaviour among Chinese adults: Results from a longitudinal investigation. Transfusion Medicine, 27(5), 335–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/tme.12422

- Javid, M. A., Abdullah, M., Ali, N., & Dias, C. (2021). Structural equation modeling of public transport use with COVID-19 precautions: An extension of the norm activation model. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 12, 100474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2021.100474

- Javid, M. A., & Al-Roushdi, A. F. A. (2019). Causal factors of driver’s speeding behaviour, a case study in Oman: Role of norms, personality, and exposure aspects. International Journal of Civil Engineering, 17(9), 1409–1419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40999-019-00403-8

- Jeon, Y. A., Ryoo, Y., & Yoon, H. J. (2022). Increasing the efficacy of emotional appeal ads on online video-watching platforms: The effects of goals and emotional approach tendency on ad-skipping behavior. Journal of Advertising, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2022.2073299

- Joanes, T. (2019). Personal norms in a globalized world: Norm-activation processes and reduced clothing consumption. Journal of Cleaner Production, 212, 941–949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.191

- Kassie, A., Azale, T., & Nigusie, A. (2020). Intention to donate blood and its predictors among adults of Gondar city: Using theory of planned behavior. PLOS One, 15(3), e0228929. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228929

- Kemp, S. (2022). Digital 2022: South Africa. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-south-africa (Accessed 19 September 2022).

- Kim, J. J., & Hwang, J. (2020). Merging the norm activation model and the theory of planned behavior in the context of drone food delivery services: Does the level of product knowledge really matter? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 42, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.11.002

- Klinkenberg, E. F., Huis In’t Veld, E. M. J., de Wit, P. D., van Dongen, A., Daams, J. G., de Kort, W. L. A. M., & Fransen, M. P. (2019). Blood donation barriers and facilitators of sub‐Saharan African migrants and minorities in Western high‐income countries: A systematic review of the literature. Transfusion Medicine, 29(S1), 28–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/tme.12517

- Khomenko, L. M., Saher, L. Y., & Polcyn, J. (2020). Analysis of the marketing activities in the blood service: Bibliometric analysis. Health Economics and Management Review, 1(1), 20–36. https://doi.org/10.21272/hem.2020.1-02

- Liu, Y., Sheng, H., Mundorf, N., Redding, C., & Ye, Y. (2017). Integrating norm activation model and theory of planned behavior to understand sustainable transport behavior: Evidence from China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(12), 1593. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121593

- Malhotra, N. K., Nunan, D., & Birks, D. F. (2017). Marketing research: An applied approach. 5th edition. Pearson Education Limited.

- Maphanga, C. (2021). Stiek uit! SANBS appeals for blood donations amid declining stocks. https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/stiek-uit-sanbs-appeals-for-blood-donations-amid-declining-stocks-20211112 (Accessed 22 May 2022).

- Mitchel, J., Custer, B., Kaidarova, Z., Murphy, L. E., & Van den Berg, K, Recipient Epidemiology and Donor Evaluation Study‐III (REDS‐III) South Africa Program. (2019). Implementation of a script for predonation interviews: Impact on human immunodeficiency virus risk in South African blood donors. Transfusion, 59(7), 2344–2351. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.15288

- Mohanty, N., Biswas, S. N., & Mishra, D. (2023). Message framing and perceived risk of blood donation. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 35(2), 165–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2021.1959488

- M’Sallem, W. (2022). Role of motivation in the return of blood donors: Mediating roles of the socio-cognitive variables of the theory of planned behavior. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 19(1), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-021-00295-2

- National Development Plan. (2022). Vision 2030. https://www.nationalplanningcommission.org.za/National_Development_Plan (Accessed 19 September 2022).

- Ndongeni-Ntlebi, V. (2021). South African National Blood Service facing severe shortages, in need of blood donations. https://www.iol.co.za/lifestyle/health/south-african-national-blood-service-facing-severe-shortages-in-need-of-blood-donations-ea3585f8-7f6d-420a-8415-5fd953db03bc (Accessed 11 April 2022).

- Nguyen, T. P. L. (2022). Intention and behavior toward bringing your own shopping bags in Vietnam: Integrating theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. Journal of Social Marketing, 12(4), 395–419. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSOCM-06-2021-0131

- Park, J., & Ha, S. (2014). Understanding consumer recycling behavior: Combining the theory of planned behavior and the norm activation model. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 42(3), 278–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcsr.12061

- Pauli, J., Basso, K., & Ruffatto, J. (2017). The influence of beliefs on organ donation intention. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing, 11(3), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPHM-08-2016-0040

- Pourfakhimi, S., Duncan, T., & Coetzee, W. J. (2020). Electronic word of mouth in tourism and hospitality consumer behaviour: State of the art. Tourism Review, 75(4), 637–661. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-01-2019-0019

- Rambiritch, V., Verburgh, E., & Louw, V. J. (2021). Patient blood management and blood conservation – complimentary concepts and solutions for blood establishments and clinical services in South Africa and beyond. Transfusion and Apheresis Science, 60(4), 103207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transci.2021.103207

- Ratebo, K. L., Kerbo, A. A., & Beshah, B. B. (2020). Intention to donate blood among health care workers of Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia. American Journal of Life Sciences, 8(4), 76–81.

- Rezaei, R., Safa, L., Damalas, C. A., & Ganjkhanloo, M. M. (2019). Drivers of farmers’ intention to use integrated pest management: Integrating theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. Journal of Environmental Management, 236, 328–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.01.097

- Romero-Domínguez, L., Martín-Santana, J. D., Sánchez-Medina, A. J., & Beerli-Palacio, A. (2021). The influence of sociodemographic and donation behaviour characteristics on blood donation motivations. Blood Transfusion, 19(5), 366–375. https://doi.org/10.2450/2021.0193-20

- Roos, D., & Hahn, R. (2019). Understanding collaborative consumption: An extension of the theory of planned behavior with value-based personal norms. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(3), 679–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3675-3

- Rui, J. R., Yuan, S., & Xu, P. (2022). Motivating COVID-19 mitigation actions via personal norm: An extension of the norm activation model. Patient Education and Counseling, 105(7), 2504–2511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2021.12.001

- Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Jr., & Ringle, C. M. (2022). “PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet”–retrospective observations and recent advances. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 31(3), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2022.2056488

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research methods for business students. 8th ed. Pearson.

- Setiwan, R., Santosa, W., & Sjafruddin, A. (2014). Integration of theory of planned behavior and norm activation model on student behavior model using cars for travelling to campus. Civil Engineering Dimension, 16(2), 117–122.

- Shin, Y. H., Im, J., Jung, S. E., & Severt, K. (2018). The theory of planned behaviour and the norm activation model approach to consumer behaviour regarding organic menus. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 69, 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.10.011

- Sia, S. K., & Jose, A. (2019). Attitude and subjective norm as personal moral obligation mediated predictors of intention to build an eco-friendly house. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 30(4), 678–694. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEQ-02-2019-0038

- Song, Y., Zhao, C., & Zhang, M. (2019). Does haze pollution promote the consumption of energy-saving appliances in China? An empirical study based on norm activation model. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 145, 220–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.02.041

- Swenson, E. R., Bastian, N. D., & Nembhard, H. B. (2018). Healthcare market segmentation and data mining: A systematic review. Health Marketing Quarterly, 35(3), 186–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/07359683.2018.1514734

- United Nations. (2022). Make the SDGs a reality. https://sdgs.un.org (Accessed 19 September 2022).

- Viwattanakulvanid, P., & Oo, A. C. (2022). Influencing factors and gaps of blood donation knowledge among university and college students in Myanmar: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Health Research, 36(1), 176–184. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHR-10-2020-0500

- Wang, S., Wang, J., Zhao, S., & Yang, S. (2019). Information publicity and resident’s waste separation behavior: An empirical study based on the norm activation model. Waste Management, 87, 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2019.01.038

- Wei, K., Zhang, J., He, Y., Yao, G., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Faulty feeder detection method based on VMD–FFT and Pearson correlation coefficient of non-power frequency component in resonant grounded systems. Energies, 13(18), 4724. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13184724

- Wiid, J., & Diggines, C. (2017). Marketing research. 3rd ed. Juta & Company.

- Xie, W., Damiano, A., & Jong, C. H. (2022). Emotional appeals and social support in organizational YouTube videos during COVID-19. Telematics and Informatics Reports, 8, 100028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teler.2022.100028

- Zhang, X., Liu, J., & Zhao, K. (2018). Antecedents of citizens’ environmental complaint intention in China: An empirical study based on norm activation model. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 134, 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.03.003

- Zhong, Y., Oh, S., & Moon, H. C. (2021). Service transformation under Industry 4.0: Investigating acceptance of facial recognition payment through an extended technology acceptance model. Technology in Society, 64, 101515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101515

- Zucoloto, M. L., Gonçalez, T., Menezes, N. P., McFarland, W., Custer, B., & Martinez, E. Z. (2019). Fear of blood, injections and fainting as barriers to blood donation in Brazil. Vox Sanguinis, 114(1), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/vox.12728

- Zucoloto, M. L., Bueno-Silva, C. C., Ribeiro-Pizzo, L. B., & Martinez, E. Z. (2020). Knowledge, attitude and practice of blood donation and the role of religious beliefs among health sciences undergraduate students. Transfusion and Apheresis Science, 59(5), 102822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transci.2020.102822