Abstract

Chambers (Citation2022) recently raised “a red flag” by pointing out that internal auditors have been unduly placing Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) risks on the back burner. Internal auditors currently do not play a significant role as assurance providers and are absent from potential advisory services about ESG – on both sides of the Atlantic. We diagnose an “ESG helplessness syndrome.” Like in the world of animals, the internal audit function is in a state of freeze response when it comes to ESG topics. The ESG challenge is so big, and the threats for the role of the Internal Audit Function (IAF) are so real, that the profession reacts like animals in the face of a threat: they freeze. We discuss and challenge the professional demand for “objectivity” and “independence” in the ESG context as they might represent obstacles to the IAF playing a significant role in the ESG agenda. We suggest practitioners consider widening the repertoire of internal auditing. We suggest an ABC-Model © of Internal Auditing, adding “Building” as a new third pillar of internal audit value creation which complements the traditional assurance and consulting services. We encourage internal auditors to become “builders” when tackling the ESG challenge in their respective organizations. Metaphorically speaking, we borrow from Yvon Chouinard, the founder of Patagonia which is often used as an ESG role model company when we suggest “Let Internal Auditors Go Surfing” as our call to action.

INTRODUCTION

The definition of internal auditing (IA) posits that internal auditing “is an independent, objective assurance and consulting activity designed to add value and improve an organization’s operations. It helps an organization accomplish its objectives by bringing a systematic, disciplined approach to evaluate and improve the effectiveness of risk management, control, and governance processes (IPPF, Citation2017)”. The international standards for professional practice of internal auditingFootnote1 reference the term “governance” 24 times, and “risk” 18 times while terms related to environmental aspects are seldom mentioned and social aspects are absent.

In 2021, the Global Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) stressed in a White Paper that “internal audit can and should play a significant role in an organization’s ESG journey” (IIA, Citation2021). The term ESG – environmental, social, and governance – was coined in 2004, derived from the “Who Cares Wins”Footnote2 report from the United Nations (Pollman, Citation2022, pp. 11–13). The report underpins the outstanding importance of G (Governance) when framing ESG by saying: “Sound corporate governance and risk management are crucial pre-requisites to successfully implementing policies and measures to address environmental and social challenges.” Based on the IAF’s value proposition and the recent call for action, there are good reasons to believe that the internal audit function (IAF) is well placed to play a key role to support management and the board in managing risks and designing internal controls related to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues.

Yet, ESG seems to be far from being well integrated into the internal audit function’s work. Referencing the World Economic Forum and other organizations, Chambers (Citation2022) concludes that “overall, ESG is one of the fastest-growing risks this year (…)”; “a top risk for 2023” (Chambers, Citation2022, p. 6). At the same time, his survey among 188 CAEsFootnote3 and internal audit directors in organizations based primarily in North America show that ESG risks are at the bottom of their priority list for 2023 audits, with significantly lower priority than for instance cyber and data security, attraction and retention of talent, macroeconomic conditions, regulatory changes, supply chain-related issues, etc. (Chambers, Citation2022, p. 7).

Internal auditors are far from having sufficiently integrated ESG aspects into their risk assessments. Chambers (Citation2022, p. 8) raises “a red flag”, and he alerts internal auditors “not be bound by last year’s perspectives.” He suggests that “if there is a clear gap between what you consider high risk for your organization and the risk focus of other audit professionals and organizations, reconsider your risk assessment.” So, there is a considerable mismatch: On the one hand, it is hard to find anyone within an organization – particularly among board members and senior managers who are the major clients of the IAF – who would claim that ESG risks are unimportant. On the other hand, ESG risks remain neglected topics in the actual work of internal auditors.

In fact, worse than that, internal auditors are not only paying little attention to ESG-related assurance services, but they are also not playing a significant role to support management and the board with the advisory services that the IAF could render. Echoing the results of Chambers’ (Eulerich et al., Citation2022) survey for the US, Eulerich et al. (Citation2022, p. 78) show that, based on a survey of 107 internal auditors, the ”IAF’s noninvolvement in ESG” (Eulerich et al., Citation2022, p. 78) is also an issue in Europe. The study concludes that internal auditors are “leaving the advisory component largely unaddressed” (Eulerich et al., Citation2022, p. 79).

The status quo of the IAF within the arena of ESG risk management and advisory services comes as a surprise given that strong signs for the growing importance of ESG-related risks and the subsequent extended reporting activities have been on the horizon for a long time: it started in 1997, when the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) was established and developed standards to report a company’s non-financial impacts on society and the planet. It was followed in 2010, by the creation of the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) with the goal of integrating ESG dimensions into one annual report to accompany and explain financial value creation. The European Union’s (EU) efforts around non-financial reporting represented by directives like the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD)Footnote4 and the soon to be adopted Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), accompanied by the EU Taxonomy,Footnote5 represent another landmark where a whole region is engaged in developing new standards for non-financial reporting. Additionally and finally, the developments since COP 26 in Glasgow in 2021 when the IFRS Foundation announced the formation of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB). The latter consolidated many of the hitherto fragmented standard setters and initiatives such as the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TFCD) the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) and the IIRC under the leadership of Ex-Danone-CEO Emmanuel Faber and has become the main driver for mandatory sustainability reporting around the world.

These changes and emerging trends in the landscape of standard setting have long been visible in the space in which internal auditors usually operate. They were accompanied by numerous calls encouraging the IAF to play a bigger role in the ESG space. It is thus extremely hard to understand why the internal audit profession has so few answers to the most pressing issues of our time for almost any organization out there. Chambers (Citation2022, p. 21) is rightfully requesting us to “prioritize ESG risk areas now.”

WHY DOES THE INTERNAL AUDIT FUNCTION NOT PLAY A BIGGER ROLE IN THE ESG ARENA?

We explain the passivity of the internal audit profession to date based on our discussions with internal auditors and numerous interactions with board members and top managers as follows: we came across the notion of the IAF’s ESG helplessness syndrome which, to us, explains well why nothing happens. Like in the world of animals, the internal audit function is in a state of freeze response when it comes to ESG topics, and only slowly takes (insufficient) actions. The ESG challenge is so big, and the threats for the role of the IAF are so real, that the profession reacts like many animals in the face of a threat: they freeze.

As a solution, we suggest internal auditors contribute now and render more value. We suggest widening the repertoire of internal audit work, possibly regarded by some in the professional community as a radical approach to reshaping the IAF, but which should help the IAF escape its ESG helplessness syndrome, and become a player at the heart of effective corporate governance. A timely intervention on ESG-related issues is, or will become, a matter of survival for many firms, in many industries in the upcoming decade.

The metaphor that guides our thinking to illustrate a possible future direction for the IAF is that of a swimmerFootnote6 who prefers to swim in a pool with clearly defined boundaries (i.e., the status quo of most IAFs), but who should become a value driving surfer who dares to swim out into the wild ocean – when it matters and is necessary – and should co-create and actively contribute to the organizational learning path by riding the waves that build up in the wild ocean (i.e., the current context organizations operate in). Metaphorically speaking, we suggest that organizations “Let Internal Auditors Go Surfing.” Before we propose a model for the IAF that allows for it playing a bigger role in the ESG arena, let us next discuss the status quo to better understand why IAFs have not yet satisfactorily been engaged in ESG.

THE IAF’S STATUS QUO ON ESG-RELATED MATTERS

In 1997, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)Footnote7 was established: “25 years of empowering sustainable decisions”. In 2022, 25 years later, Chambers (Citation2022) raises “a red flag” for internal auditors who have been unduly placing ESG risks on the backburner. Today, internal auditors have no role as assurance providers and are absent from potential advisory services about ESG - on both sides of the Atlantic (Chambers, Citation2022; Eulerich et al., Citation2022).

Lenz and Jeppesen (Citation2022, p. 6) posit that “ESG is becoming a question of “Do or Die” for society, for companies and for internal auditors.” Many authority figures in the internal audit space echo this claim, and yet the Deloitte (Citation2022) sustainability action report does not mention internal audit at all.

While acknowledging that some IAFs of listed firms in highly regulated environments already take ESG issues into account, most companies that have an IAF see ESG-related risk and governance matters as in their infancy, despite significant challenges to the timely achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).Footnote8

Braasch and Velte (Citation2022, p. 1) investigated the quality of climate reporting by German DAX30 companies, concluding “the companies showed poor reporting rates in the corporate governance domain, indicating that they use climate reporting symbolically to present themselves in a favorable light and to gain legitimacy in society.”

Eulerich et al. (Citation2022) provide empirical evidence about internal auditor’s noninvolvement in ESG, pointing to the lack of awareness on parts of stakeholders (according to 107 internal auditors from Europe (mainly Germany) included in their survey). According to which, many stakeholders still do not know what internal audit can and should do in the ESG arena. While there is willingness and readiness to engage in the ESG arena, internal auditors lack supportive guidance and a clear framework covering all of the opportunities to contribute.

Lenz and Jeppesen (Citation2022) point to the hazy nature of internal auditing’s value proposition and the absence of a clear Unique Selling Proposition (USP). In that sense, three fingers point back to the internal audit profession. There is currently work underway by the Institute of Internal Auditors, the Global-IIA, to overhaul the IPPF, the International Professional Practices Framework,Footnote9 which presents a fantastic opportunity to clarify the USP, and the role of internal auditors in the ESG context.

There is unexploited potential - as assurance provider and advisor. “Clarification is required on how internal auditors can get engaged in ESG while keeping their independence,” summarize Eulerich et al. (Citation2022, p. 81). Hence, positioning internal auditors more clearly as enablers of learning and change in the ESG arena can be a path forward to overcoming obstacles of which some, including the professional demand for independence and objectivity, are self-inflicted. Before we discuss those terms that have been at the heart of internal auditing, we argue that the context of the IAF’s work has changed dramatically, and that in turn questions the ongoing use of independence of the function, and objectivity of internal auditors as guiding principles.

NEVER WASTE A GOOD CRISIS: PIONEERING INSTEAD OF MANAGING

Since the outbreak of COVID-19 all internal auditors have had to become pioneers. For instance, on-site internal audits were no longer an option, and most internal auditors needed to start performing audits remotely. As a result, the outbreak of COVID-19 was a decisive moment for the internal audit profession. No change, no innovation of practices, business as usual – they were no options for the value-adding internal auditor.

The internal auditors’ social capital with management and the board is critical in times of crises. Given their unique positioning and perspective, there is plenty internal auditors have to offer. Relationship equity is the key and a prerequisite for internal audit to be part of the solution (and not the problem). Shared goals, shared knowledge, and effective communication (frequent, timely, and problem-solving minded) are key ingredients of a successful value-adding internal audit function.Footnote10 The present opportunity in the face of not only the Covid crisis, but also the numerous ESG-related crises such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and forced migration, is to rethink the IAF’s role. To do so, it is important to acknowledge the changing context in which internal auditors operate.

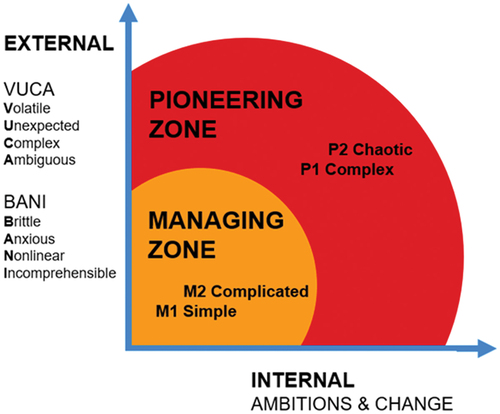

Internal auditors have traditionally been good at dealing with complicatedness, addressing the WHAT IS question. Nuijten et al. (Citation2015) suggest internal auditing expand its repertoire to better address the needs and requirements of the world of VUCAFootnote11 and BANI.Footnote12 The traditional approach, dealing with “complicatedness” no longer suffices. The new world is better described by interactive complexity (Nuijten et al., Citation2015, p. 195): “Interactive complexity is a dynamic process in which the system and agents co-evolve in their mutual interactions.”Footnote13

Snowden and Boone (Citation2007) deliver a framework (the “Cynefin framework”) which illustrates not only changing contexts, but also suggests different kinds of responses. The authors sort the issues leaders are facing into four categories:

Simple Contexts: The Domain of Best Practice

Complicated Contexts: The Domain of Experts

Complex Contexts: The Domain of Emergence

Chaotic Contexts: The Domain of Rapid Response

Internal auditors must widen their repertoire to deal with the changing context from complicated to complex. To stay relevant, as Nuijten et al. (Citation2015) suggest, internal auditors must become more familiar with WHAT IF type of questions and with scenario thinking.

We apply Snowden and Boone’s (Citation2007) framework to illustrate the potential roles that internal auditors can play, and how they change according to different contexts. We introduce (please see ) the terms MANAGING ZONE and PIONEERING ZONEFootnote14:

In our definition, the MANAGING ZONE consists of simple (M1) and complicated (M2) contexts. Here, there is typically one right answer or a narrow spectrum of right answers. In those contexts, internal auditors can aspire to be objective. We doubt these contexts will be the ones where value-adding IA will take place in the future. According to Snowden and Boone’s (Citation2007), “simple contexts are characterized by stability and clear cause-and-effect relationships that are easily discernible by everyone.” They continue, “complicated contexts, unlike simple ones, may contain multiple right answers, and though there is a clear relationship between cause and effect, not everyone can see it. (…) In a complicated context, at least one right answer exists.”

In our definition, the PIONEERING ZONE consists of complex (P1) and chaotic (P2) contexts. According to Snowden and Boone’s (Citation2007), “most situations and decisions in organizations are complex because some major change—a bad quarter, a shift in management, a merger or acquisition—introduces unpredictability and flux. In this domain, we can understand why things happen only in retrospect.” Moreover, “in a chaotic context, searching for right answers would be pointless: The relationships between cause and effect are impossible to determine because they shift constantly and no manageable patterns exist—only turbulence.”

Based on Snowden and Boone’s (Citation2007) definitions, objectivity of internal auditors is an illusion in the PIONEERING ZONE, in COMPLEX (P1) and CHAOTIC (P2) contexts. In complex contexts we can understand what happens only in hindsight. This is the area of “unknown unknowns.” Snowden and Boone’s (Citation2007) reference the rain forest as example, being in constant flux, requiring a more experimental mode of management. “In a chaotic context, searching for right answers would be pointless.” For instance, “the events of 11 September 2001, fall into this category.” There can be no assurance in complex and chaotic contexts either, as defined here.

We view managing ESG as part of a pioneering path. In that category, the one right answer is not known, there are many potential paths to pursue. Going forward, we need effective internal auditing in the PIONEERING ZONE, in complex and chaotic contexts. This is the arena where we can find the future space of value-adding internal auditing. Building on our initially introduced metaphor, we thus suggest that internal auditors should not be afraid of entering the pioneering zone, becoming surfers the wild ocean. below illustrates the use of our metaphor for internal auditing.

Our mini typology distinguishes three types of internal auditors: the stander, the swimmer, and the surfer. Type 1 is standing on the sidelines, s/he is not much involved in what is going on in the organization. Type 2 is doing business as usual, swimming in a calm pool, as it were. Type 3 is what Eulerich and Lenz (Citation2020) label the “value driver”, surfing the wild ocean.Footnote15 While the role of internal auditors may vary over time and depending on the assignment, contributing to the ESG agenda means entering unknown territory, which in turn requires a type 3 internal auditor who is ready to surf the wild ocean and thus enter the pioneering zone.

That is easier said than done. The following two rhetorical questions evidence the dilemma for many internal auditors: (1) How to audit something you have never audited before? That can be addressed. (2) What is the point in auditing something that does not exist? That sounds like a mission impossible - or a truly short assignment, of little or no value.

REMOVING OBSTACLES FOR THE IAF’S CONTRIBUTION IN THE ESG ARENA

Can internal auditors do more? We argue, in the pioneering zone internal auditors may add a competency to their portfolio: that they become builders, co-creators. We advocate that the ESG journey may be one of those complex occasions where internal auditors and the internal audit profession should step out of their comfort zone and break through traditional barriers to truly make value adding contributions to a vital subject matter.

When aspiring to break through traditional barriers, we view the professional demand for “objectivity” and “independence” as two obstacles to address in this context. These two hurdles stand in the way of internal auditors contributing in the ESG arena, and we argue that they are hard to maintain while expanding the role of the IAF in ESG.

First and foremost, on the ESG journey we enter unknown territory, we enter the pioneering zone, where there can be no objectivity, as outlined above. Thus, the aspirational demand for objectivity should not be of concern to internal auditors in the pioneering zone, dealing with complex and chaotic contexts.

Secondly, the occasionally mis-used or mis-interpreted concept of independence may sometimes serve internal auditors as a pretext for in-action. This argument does not work in the ESG context. Why? Primarily and simply because it is most unlikely that internal auditors will be tasked with ESG related assurance work. As DeSimone et al. (Citation2021, p. 563) argue: “organizations likely prefer external rather than internal assurance, since external stakeholders may perceive internal assurance as less independent and more likely as window-dressing practice than external assurance.” Moreover, on 28 November 2022, the European Council gave the final green light to the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD),Footnote16 with first such reporting obligation in 2025 on the fiscal year 2024. The DirectiveFootnote17 includes an obligation for externalFootnote18 verification of the sustainability information, initially with limited assurance. As the Deloitte (Citation2022, p. 3) survey states, companies begin to shift “from commitment to action”, and “nearly all respondents (96%) plan to seek externalFootnote19 assurance for the next reporting cycle.” Thus, assurance will largely come from external auditors who might also be much better equipped (in terms of headcount and expertise) to stem the challenge of ESG assurance.

As a result, the territory of ESG assurance might be gone for the IAF as its key stakeholders turn to external auditors for that service. Presently, the only other, remaining pillar of internal audit services regarding ESG: internal auditors can do more work of a consultancy (advisory) nature.

However, consultancy (advisory) services have been “largely unaddressed” to date (Eulerich et al., Citation2022), as the extensive internal auditing literature has outlined. Feeney and Aiken (Citation2022) from AuditBoard, for example, give helpful guidance on “How do you audit never-before-audited business areas.” The Guide to Internal Review of Sustainability Report, for example, from The Institute of Internal Auditors Singapore (Eulerich et al., Citation2022) and the 2021 White Paper from the institute of Internal Auditors in the US (the Global-IIA) about internal audit’s role in ESG reporting are good reads. As are Schor et al. (Citation2022) from AuditBoard and Deloitte, and McClure and Stone (Citation2022) from Crowe. So, while assurance service might not be at the heart of internal auditor’s role in the ESG arena, consulting services are a possibility. Therefore, we suggest widening the repertoire of internal audit work based on what we call the ABC-model to enable the IAF to stay relevant.

OUR ABC-MODEL © - THE FUTURE ROLE OF THE IAF

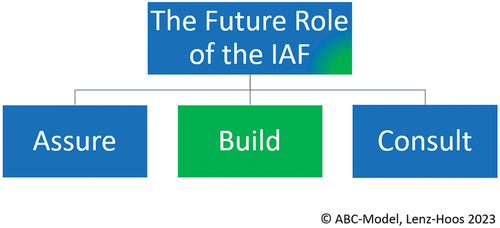

In addition, “to assure,” and “to consult,” we introduce a new third pillar of internal audit activity which serves to broaden the value proposition of the IAF: “to build.” below illustrates our ABC-Model. We encourage the internal audit profession and internal audit professionals to also consider “doing stuff,” “co-creating,” or say “building” as a core activity, additional to the traditional assurance and consulting services. We add a B (building) to the current A (assurance) and C (consulting) model to make it an ABC-Model ©. The new component is shown in a different color below.

Our suggested ABC-Model © for the future role of the IAF includes the new option of BUILDING, an opportunity for internal auditors to add value. Doing so might be perceived by many as going beyond the present standards (IPPF, Citation2017) and as a stretch of the IAF’s role as outlined in the Three-Lines-Model.Footnote20 It certainly would be a notable change vis-à-vis the present positioning and self-image of many IAFs, an approach that may not be applicable to all circumstances.Footnote21 We see, however, that this expansion of scope can be compatible with the present Professional Standard 1112 - Chief Audit Executive Roles Beyond Internal Auditing (IPPF, Citation2017, p. 43), saying: “Where the chief audit executive has or is expected to have roles and/or responsibilities that fall outside of internal auditing, safeguards must be in place to limit impairments to independence or objectivity.”

We encourage CAEs and C-level executives to reconsider the potential contribution from internal auditing. There is more. Internal auditors can do more. When internal auditors enter the pioneering zone they may become builders, co-creators of a powerful ESG environment within the firm which prevents risks and helps to build multiple scenarios for the future path of the organization depending on changing contexts. We advocate that addressing ESG may be an opportunity for internal auditors and the internal audit profession to consider going beyond their core remit of rendering assurance and consulting services, to help building an ESG program – before it can be audited (by external auditors, as seems likely).

On the ESG journey, internal auditors can be most valuable as co-creators, as builders, as members of the ESG team. Internal auditors are a valuable, readily available resource but, for in part self-inflicted reasons, unfortunately often neglected. Internal auditors serve internal purposes, being typically well educated, continuous learners, they can be enablers of learning and change. Internal auditors are typically well positioned (type 2 and 3, that is, rather than type 1 as outlined above) to help an organization on its critical ESG mission, determining the destiny of many future business models.

Internal auditors should be good at advancing the body of knowledge by asking questions and being strategic listeners.Footnote22 We see potential in positioning internal auditors more clearly as enablers of learning and change.Footnote23 We regard a promising path forward to be overcoming hurdles, including those set by professional demands for independence and objectivity. The more effective internal auditor can be “a hinge, a connector, a relation facilitator” (Lenz, Citation2013, p. 205). This is in line with McClure and Stone (Citation2022) holding internal auditors to be interpreters on the route to successful ESG reporting and management, saying, as they do, that internal auditors “understand the position of senior management and the board as well as regulatory expectations. With their ability to tie together process, strategy, and risk management, IA can be a key translator as companies bring teams together across the organization to address proposed regulatory requirements. IA can also play a central role in setting up processes and IT controls (…).”

There are many reasons why senior management and the board may consider deriving more benefits from their internal audit capabilities through the application of an ABC-Model to build their ESG program. Internal audit is potentially well equipped to help get ESG on a good pioneering path. The time is ripe for getting the job done. Our call to action: Let Internal Auditors Go Surfing!

CONCLUSION

Positioning internal auditors more clearly as enablers of learning and changeFootnote24 and as builders is a promising path forward for overcoming hurdles, including professional demands for independence and objectivity.

We recommend CAEs to discuss with senior management and the board: “How best can internal audit help the organization successfully manage ESG and associated risks?” Such a discussion may reveal new opportunities for internal auditors to enhance the value of their services. ESG is a hot topic, and will be for all forthcoming generations. However, so far, internal audit’s contribution to it has been too little.

Given the complexity of ESG related challenges, we are all in the pioneering zone and there is no panacea, no expert who will successfully address them for us. The “Garden” of ESG, to use Lenz and Jeppesen’s (Citation2022) metaphor, is never finished. Our plea about the use of external consultants in the context of ESG is therefore to use them very selectively and wisely.

We also invite the global standard setter, the IIA, to widen the repertoire of internal auditors. Our simple ABC-Model © suggests allowing internal auditors to “do stuff.” We suggest the addition of “Building” as a remit for internal auditors where appropriate, to complement existing assurance and consulting services.

We argue that the story of the chained elephantFootnote25 resembles some IAFs who remain tied to past experiences. The elephant is held back not by the puny rope but by its belief system. There is more internal audit can do.

We expect that adding “Building” to the repertoire of internal auditors will prove valuable, especially to smaller IAFs and better reflect their reality. That is particularly relevant since most internal audit departments are small: “Globally, 51% (48% in North America) of those surveyed said their internal audit function comprised a staff of five or less. More broadly, 71% (73% from North America) overall said their team had 10 or fewer staff.” Footnote26

Briefly, our credo for the IAF’s contribution to the ESG agenda is: Let Internal Auditors Go Surfing!

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Rainer and Florian thank David Jackson for proofreading our manuscript.

We thank the reviewers of our paper, and we thank Dan Swanson, the Managing Editor of EDPACS, for the opportunity.

The authors thank David Hill, CEO at SWAP Internal Audit Services, for funding OPEN ACCESS.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1. IPPF (Citation2017), accessed online, 16 December 2022, International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing (Standards), https://www.iianigeria.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/IPPF-Standards-2017.pdf.

2. Pollman (Citation2022, p. 11) references: THE GLOBAL COMPACT, WHO CARES WINS: CONNECTINF FINANCIAL MARKETS TO A CHANGING WORLD (2004).

3. CAE stands for Chief Audit Executive.

4. Directive 2014/95/EU which is also called the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) was the first EU Directive to make disclosure of non-financial and diversity information mandatory for certain large companies.

5. EU taxonomy for sustainable activities, accessed online, 16 December 2022, https://finance.ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance/tools-and-standards/eu-taxonomy-sustainable-activities_en.

6. Lenz (Citation2013) references “swimming in the organization” as a metaphor for an effective internal auditor who represents an effective IAF. We build on that.

7. Accessed online, 19 December 2022, https://www.globalreporting.org/about-gri/mission-history/.

8. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Report provides annually an overview of progress on the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. According to the report, “the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [is] in grave danger.” Focusing on the ESG components of the 17 SDGs, referencing, for example, SDG 13, Climate Action, “our window to avoid climate catastrophe is closing rapidly” (United Nations, Citation2022, p. 20).

9. IPPF Evolution: The Standards Are Changing, accessed online, 15 December 2022, https://www.theiia.org/en/standards/ippf-evolution/.

10. Lenz (Citation2013).

11. Volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity, Wikipedia, accessed online, 15 December 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volatility,_uncertainty,_complexity_and_ambiguity#:~:text=%20Volatility%2C%20uncertainty%2C%20complexity%20and%20ambiguity%20From%20Wikipedia%2C,complexity%20and%20ambiguity%20of%20general%20conditions%20and%20situations.

12. BANI – How to make sense of a chaotic world? The acronym BANI stands for Brittle, Anxious, Non-linear, and Incomprehensible. Think insights, accessed online, 15 December 2022, https://thinkinsights.net/leadership/bani/#:~:text=The%20acronym%20BANI%20stands%20for,Brittle%2C%20Anxious%2C%20Non-linear%20and%20Incomprehensible.

13. Nuijten et al. (Citation2015, p. 199): “The contrast between interactive complexity and complicatedness is important for the field of internal auditing, because it implies that it is not possible to generate assurance about the quality, output or management control over an interactively complex system.”.

14. The coauthor Rainer Lenz first mentioned that model 2017, as presenter at the European Conference of the Institute of Internal Auditors (ECIIA) in Basel (Switzerland), speaking about “SUCCESs - Simple, Unexpected, Concrete, Credible, Emotional, and Stories”, https://drrainerlenz.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/eciia-2017_dr-rainer-lenz_21-09-2017.pdf, page 13.

15. Lenz and Jeppesen’s (Citation2022).

16. European Council Press Release from 28 November 2022, accessed online 15 December 2022, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/11/28/council-gives-final-green-light-to-corporate-sustainability-reporting-directive/.

17. DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL amending Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Directive 2013/34/EU, as regards corporate sustainability reporting, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/PE-35-2022-INIT/en/pdf.

18. Info: emphasis in bold was added by the authors of this article.

19. Info: emphasis in bold was added by the authors of this article.

20. Three Lines Model, accessed online, 16 December 2022, https://www.theiia.org/en/content/position-papers/2020/the-iias-three-lines-model-an-update-of-the-three-lines-of-defense/.

21. We encourage further research of the suggested B (building) component to heighten understanding of applied practices and to enrich the cooperation between internal audit and peers in the respective organization, that is, the first and second line.

22. Lenz (Citation2013): “The Latin word “audire” means ‘to hear’ in English. As Ridley (Citation2008, p. 293) states, “the right questions will always be the key to effective internal auditing. So will be right listening!” There is a deeper meaning in the fact that humans have two ears and one mouth (so that we can listen twice as much as we speak). That may be particularly good advice for internal auditors.”.

23. Please see pages 7–8 when presenting “SUCCESs - Simple, Unexpected, Concrete, Credible, Emotional, and Stories” at the European Conference of the Institute of Internal Auditors (ECIIA) in 2017 Basel (Switzerland): https://drrainerlenz.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/eciia-2017_dr-rainer-lenz_21-09-2017.pdf.

24. Building on Scharmer (Citation2009, pp. 126–128), ref. Rainer Lenz’ presentation “SUCCESs - Simple, Unexpected, Concrete, Credible, Emotional, and Stories” at the European Conference of the Institute of Internal Auditors (ECIIA) in 2017 Basel (Switzerland), pages 7-8: https://drrainerlenz.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/eciia-2017_dr-rainer-lenz_21-09-2017.pdf.

25. Accessed online, 30 December 2022, https://www.brentwebb.com/post/the-beautiful-story-of-the-chained-elephant.

26. Richard Chambers, Blog from 01 August 2022, An Inconvenient Truth: Most Internal Audit Departments Are Small, accessed online, 19 December 2022, https://www.richardchambers.com/an-inconvenient-truth-most-internal-audit-departments-are-small/.

REFERENCES

- Braasch, A., & Velte, P. (2022). Climate reporting quality following the recommendations of the task force on climate-related financial disclosures: A focus on the German capital market. Sustainable Development, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2430

- Chambers, R. (2022). 2023 focus on the future report, internal audit must accelerate its response in addressing key risks. AuditBoard.

- Chouinard, Y. (2016). Let my people go surfing: The education of a reluctant businessman–Including 10 more years of business unusual, 15th printing. Penguin Books.

- Deloitte. (2022, December). Sustainability action report: Survey findings on ESG disclosure and preparedness.

- DeSimone, S., D’Onza, G., & Sarens, G. (2021). Correlates of internal audit function involvement in sustainability audits. Journal of Management & Governance, 25(2), 561–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-020-09511-3

- Eulerich, M., Bonrath, A., & Lopez-Kasper, V. (2022, November). Internal auditor’s role in ESG disclosure and assurance: An analysis of practical insights. Corporate Ownership & Control, 20(1), 2022. https://doi.org/10.22495/cocv20i1art7

- Eulerich, M., & Lenz, R. (2020). Defining, measuring and communicating the value of internal audit. Internal Audit Foundation.

- Feeney, C., & Aiken, J. (2022). Step-by-step guide to building your ESG Program: Resources, best practices, and key considerations. AuditBoard Inc.

- IIA 2021, The institute of Internal Auditors, US. (2021). Internal audit’s role in ESG reporting, independent assurance is critical to effective sustainability reporting. White Paper. The Institute of Internal Auditors Inc.

- IIA 2022, The Institute of Internal Auditors, Singapore. (2022). Guide to internal review of sustainability report.

- IPPF. (2017). International professional practices framework. The Institute of Internal Auditors Inc. https://www.iianigeria.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/IPPF-Standards-2017.pdf

- Lenz, R. (2013). Insights into the effectiveness of internal audit: a multi-method and multi-perspective study [ Doctoral Thesis 01|2013, Université catholique de Louvain - Louvain School of Management Research Institute]. https://drrainerlenz.files.wordpress.com/2013/03/lenz-r.-2013-diss.pdf

- Lenz, R., & Jeppesen, K. K. (2022). The future of internal auditing: Gardener of governance. EDPACS, 66(5), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/07366981.2022.2036314

- McClure, C., & Stone, A. (2022, November 1). Internal audit’s new role: ESG sustainability reporting, blog.

- Nuijten, A., Van Twist, M., & van der Steen, M. (2015, November). Auditing interactive complexity: Challenges for the internal audit profession. International Journal of Auditing, 19(3), 195–205. Available at SSRN: https://doi.org/10.1111/ijau.12049

- Pollman, E. (2022). The making and meaning of ESG. U of Penn, Inst for Law & Econ Research Paper No. 22-23, European Corporate Governance Institute - Law Working Paper No. 659/2022. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4219857

- Ridley, J. (2008). Cutting edge internal auditing. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Scharmer, C. O. (2009). Theory U: Leading from the future as it emerges. Berret-Koehler Publishers.

- Schor, M., Robinson, C., & Wheeler, J. (2022). How to audit ESG risk and reporting, key considerations for developing your environmental, social, and governance audit strategy, auditboard | Deloitte.

- Snowden, D. J., & Boone, M. E. (2007). A leader’s framework for decision making. Harvard Business Review, 85(11), 68–76, 149.

- United Nations. (2022). The sustainable development goals report, publication issued by the department of economic and social affairs (DESA). https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/